The relationship between mental health outcomes and a range of quality-of-life indicators – spanning the domains of physical health; knowledge, skills and educational attainment; and environmental quality and natural capital – is often bidirectional. Well-being deprivations are associated with an elevated risk for mental ill-health and lower positive mental health, while a higher quality of life serves as a resilience factor for better mental health outcomes. Examples of interventions available to policy makers include better integrating physical and mental health services; promoting physical activity; establishing school-based interventions and lifelong learning programmes; funding eco-therapy and green interventions and promoting green cities; and a better accounting of the mental health costs of climate change, and the benefits of climate action.

How to Make Societies Thrive? Coordinating Approaches to Promote Well-being and Mental Health

3. Risk and resilience factors for mental health and well-being: Quality of life

Abstract

Quality of life encompasses the areas beyond material conditions that enable individuals to live enriched, fulfilled lives. It includes outcomes such as robust physical health, the acquisition of knowledge and skills and having access to a clean and healthy living environment. In addition to these outcomes, which shape life today, ensuring the sustainability of quality of life into the future means it is important to build up human capital (e.g. healthy behaviours today to ensure long-term health into the future; educational attainment) and natural capital (e.g. combatting climate change through reduced emissions, limiting biodiversity loss). All of these areas shape, and many are in turn shaped by, mental health outcomes.

3.1. Physical health and healthy behaviours

Both physical and mental health are integral components of overall well-being and are highly correlated (OECD, 2020[1]; 2013[2]). Poor physical and mental health outcomes often co-occur: there is a wide evidence base showing the close association between poor mental health outcomes and cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), musculoskeletal disorders, asthma, arthritis, cancer and HIV/AIDS (Naylor et al., 2012[3]; Fenton and Stover, 2006[4]; NICE, 2010[5]; Sheehy, Murphy and Barry, 2006[6]). The relationship is bidirectional (OECD, 2021[7]; Ohrnberger, Fichera and Sutton, 2017[8]): that is, having poor physical health can lead to the development of specific mental health conditions, or lower levels of positive mental health, and at the same time, having low levels of mental health can lead to the onset of a range of physical health problems. The interaction between poor physical health and poor mental health can lead to increased morbidity and premature mortality (OECD, 2021[7]). OECD evidence has shown that individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder face a higher risk of death as compared to the general population (OECD, 2021[7]). Other research has shown that people with mental health problems can be up to four times as likely to die prematurely, primarily from issues such as cardiovascular disease (Naylor et al., 2012[3]). These strong interlinkages underscore the need for better integration between the provision of physical and mental health care services (refer to Box 3.1 for more).

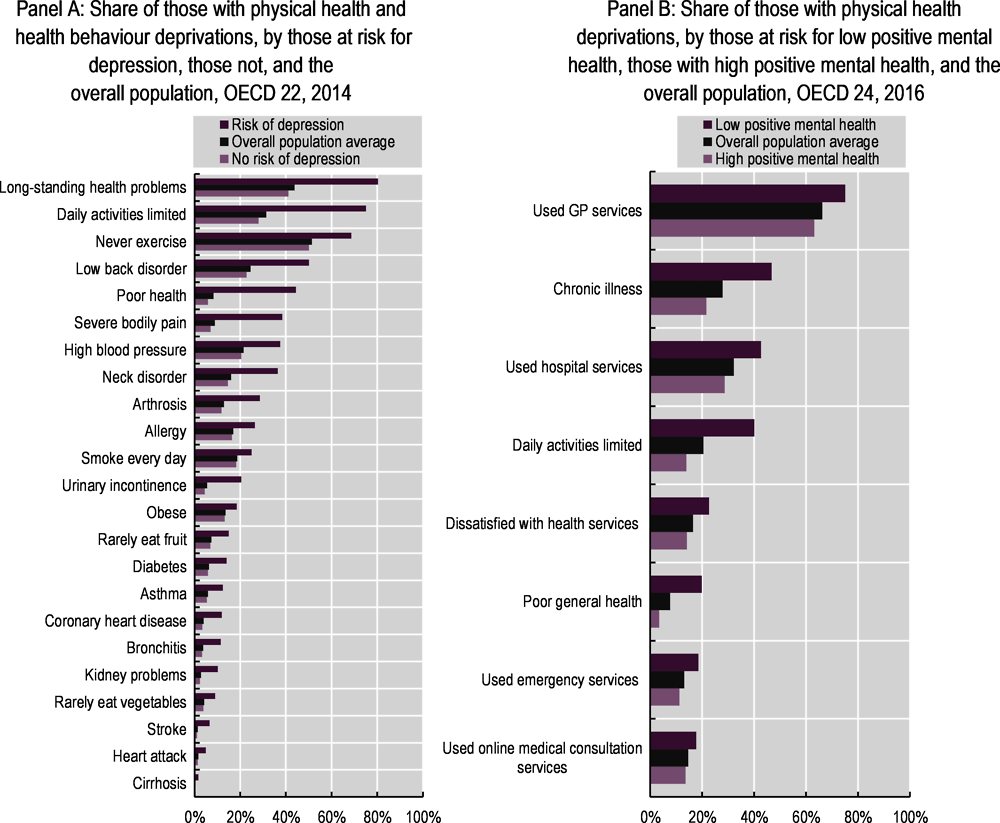

The strong links between physical and mental health are illustrated in Figure 3.1 below, which shows the prevalence of a range of health deprivations for those at risk for poor mental health compared to the general population and to those not at risk. Panel A uses a measure of mental ill-health (those at risk for major depressive disorder) in 22 European OECD countries, while Panel B uses low levels of positive mental health in 24 European OECD countries. For both mental ill-health and positive mental health, the largest gaps in outcomes by mental health outcomes occur for self-reported physical health: for example, those at risk for depression are more than seven times as likely to report poor physical health. The prevalence of having a long-term illness, or physical problems that limit one’s daily activities, also shows large gaps by mental health status. Panel A shows that certain medical conditions – such as having had a stroke, heart problems, liver or kidney problems – are more likely to be reported by those at risk for major depressive disorder.

Physical and mental health outcomes are interlinked, and poor outcomes in one area can lead to poor outcomes in the other

Having worse physical health can lead to worse mental health outcomes. Research has shown that people experiencing long-term, chronic illnesses are two to three times as likely as the general population to experience poor mental health (Naylor et al., 2012[3]). Research from the World Health Organization has found that type 2 diabetes is associated with a 60% increased risk for depression, and having chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) is associated with an up to 20% increased likelihood of exhibiting symptoms of anxiety disorders (OECD, 2021[7]; Cohen, 2017[9]). Diabetic patients with co-morbid depression have worse biological (e.g. worse glycaemic control) and psycho-social practices (e.g. less adherence to treatment, less physical activity, poorer dietary habits) that can worsen their symptoms and lead to worse physical health outcomes (Fenton and Stover, 2006[4]). Physical health conditions such as COPD can result in patients becoming more socially isolated or require them to stop doing activities that bring them joy, which can in turn cause depression (NICE, 2010[5]). Among the population of people diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, those who feel the disease will last indefinitely, or who feel helpless to manage their symptoms and the disease course, are more likely to develop symptoms of depression (Sheehy, Murphy and Barry, 2006[6]).

Figure 3.1. Poor physical health is strongly associated with both an elevated risk for major depressive disorder and low positive mental health

Note:: In Panel A, risk of major depressive disorder is defined using the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) tool. In Panel B, positive mental health is defined using the World Health Organization-5 (WHO-5) tool. Refer to the Reader’s Guide for full details of each mental health survey tool, for how each well-being deprivation is defined and for which countries are included in each OECD average.

Source: Panel A: OECD calculations based on European Health Interview Survey (EHIS) wave 3 data (Eurostat, n.d.[10]) (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:European_health_interview_survey_(EHIS); Panel B: OECD calculations based on the 2016 European Quality of Life Surveys (EQLS) (Eurofound, n.d.[11]) (database), https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-quality-of-life-surveys.

This relationship also exists for positive mental health: research conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the United Kingdom has found that populations experiencing poor physical health outcomes experienced significant drops in all facets of positive mental health – life evaluation, eudaimonia and affect balance – as compared to the general population. Another study found significant drops in happiness before and after the onset of a physical disability (OECD, 2013[2]), and specific conditions such as the experience of a heart attack or stroke have also been demonstrated to reduce positive mental health (Boarini et al., 2012[12]). Within the realm of positive mental health, affect has a stronger relationship to physical health outcomes than do measures of eudaimonia or life evaluation. This may be because having a physical health condition does not so much impact an individual’s perception of how satisfied they are with their life (life evaluation) or how much meaning they draw from it (eudaimonia) as it does the amount of negative feelings they experience on a daily basis (Boarini et al., 2012[12]).

The presence of a mental health condition can also heighten one’s risk for a physical health condition. People with mental health conditions can be at almost twice the risk for developing physical health problems, including obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease (OECD, 2021[7]). A 15-year-long study found that baseline risks for depression, worry and general mental distress could predict future gastrointestinal disorders and hyperimmunity illness (encompassing conditions such as arthritis and asthma) (Vogt et al., 2011[13]). A separate evidence review found that depression can increase the risk of the onset of coronary artery disease and ischaemic heart disease by up to 100%, and that chronic stress can have real impacts on the cardiovascular, nervous and immune systems that result in a range of diseases (Naylor et al., 2012[3]). There are biological underpinnings to this relationship: conditions such as depression and anxiety can result from hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis disregulation, causing a chronic influx of inflammatory factors to enable a stress response. Chronic exposure to inflammatory factors can then contribute to other inflammation disorders, including cardiovascular disease (Iob, Kirschbaum and Steptoe, 2020[14]; Nettis, Pariante and Mondelli, 2020[15]). Another potential explanation is that having a mental health condition may diminish a patient’s ability to adhere to a treatment plan or manage their symptoms: for example, patients with depression have higher rates of re-hospitalisation for cardiovascular disease as compared to those without depression (OECD, 2021[7]). Additionally, psychiatric medications can have a range of indirect physical health effects, with antipsychotic medications in particular associated with cardiovascular and metabolic side effects (OECD, 2021[7]).

Conversely, high levels of positive mental health can provide resilience to future health risks. Individuals with higher levels of positive mental health are more likely to be physically healthy, and both affect and life evaluative measures of positive mental health have been shown to be associated with better long-term health and life expectancy (OECD, 2013[2]). This is true for specific physical health conditions, and not just general self-reported assessments of health: for example, there is a link between psychological well-being – and optimism, in particular – and better cardiovascular health (Boehm and Kubzansky, 2012[16]). Research has found that individuals with high levels of positive affect are less likely to become ill when exposed to a cold virus, and even when infected, recover more quickly than those with low affect (OECD, 2013[2]; Pressman and Cohen, 2005[17]).

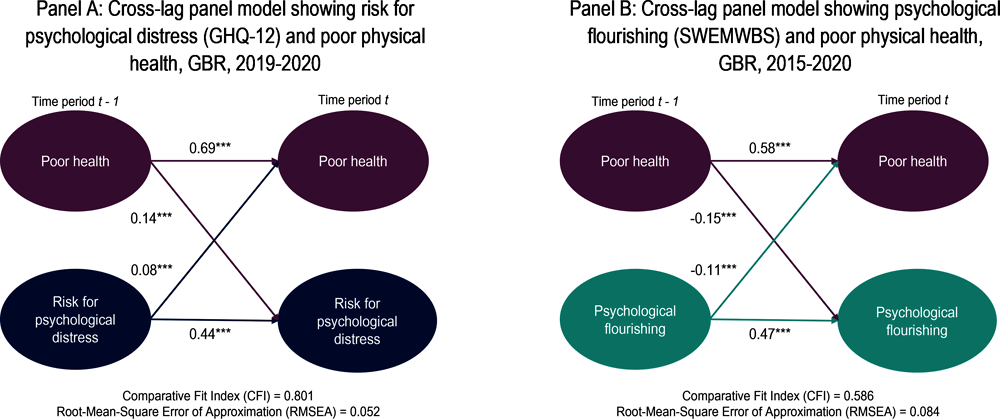

The two-way relationship between physical and mental health is illustrated in the cross-lagged panel models shown in Figure 3.2 below. Cross-lagged panel models show that the causal relationship between two outcomes (here, mental health vs. physical health) moves in both directions simultaneously, with each outcome influencing the future trajectory of the other. Panel A shows that previous experience of psychological distress is associated with a greater likelihood of current poor health, and conversely, that previous experience of poor health is associated with a greater current risk of psychological distress. This general pattern is repeated in Panel B, which shows positive mental health. In both cross-lagged panel models, the effect of previous physical health on current mental health is stronger than the effect of previous mental health on current physical health: however, the impacts in both directions are significant.

Figure 3.2. There is a reciprocal relationship between physical and mental health

Note: The model is adjusted for the following time-invariant covariates: age, sex, education, ethnicity, urban/rural. Coefficients are standardised. Self-reported health is measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor). Data included come from waves 9 and 10 (Panel A) and waves 7 and 10 (Panel B) of the UKHLS survey; waves are different across panels, given data limitations. GHQ-12 measures psychological distress on a scale from 0 (least distressed) to 12 (most distressed). SWEMWBS measures positive mental health, ranging from 9.5 as low psychological well-being to 35 as mental flourishing. All analyses were performed using Mplus and the R “MplusAutomation” package. More details on the models can be found in the Reader’s Guide.

Source: University of Essex (2022[18]), Understanding Society: Waves 1-11, 2009-2020 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009 [data collection], 5th Edition. UK Data Service, https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/.

Healthy lifestyle behaviours can improve future physical and mental health

The health choices that individuals make today impact their quality of life in the future. At a societal level, healthy behaviours – such as lowering obesity through increasing physical activity and healthy eating habits; minimising alcohol consumption; and preventing tobacco use – shore up human capital and reduce costs to society as a whole.

Given the benefits of physical activity to a range of physical and mental health outcomes, promoting it is one effective way of boosting population mental health (Box 3.1). Physical activity, which along with healthy eating habits,1 lessens the risk for obesity, also has a strong relationship with mental health (OECD, 2021[7]; Ohrnberger, Fichera and Sutton, 2017[8]). Exercising can lead to mood improvement, better self-esteem, and lower levels of anxiety, worry and stress (OECD, 2021[7]). At the same time, individuals with mental health conditions are less likely to exercise: for example, those diagnosed with major depressive disorder are half as likely to exercise regularly (where “regularly” is defined according to official guidelines) as compared to the general population (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019[19]). Lack of (motivation to) exercise can in part be the by-product of depressive symptoms, which then creates a cyclical decline. Exercise and increased physical activity can improve the mood and slow the cognitive decline of people who have been diagnosed with a range of mental health conditions, including depression, schizophrenia and dementia. In these same patient populations, increased physical exercise can help prevent the onset of other diseases, such as diabetes and obesity (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019[19]). However, it should be noted that medications for more severe psychotic disorders can have strong side effects – including sedation – that make exercise difficult (Iasevoli et al., 2020[20]).

Drinking alcohol to excess, or experiencing alcoholism, often occurs alongside symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Excess alcohol consumption can worsen symptoms and the trajectory of comorbid conditions such as depression, and in the extreme can lead to death or suicide (Sullivan, Fiellin and O’Connor, 2005[21]). Alcohol-dependent individuals often cite their drinking as a way of self-medicating symptoms of sadness, depression, anxiety or worry. While some research does indeed show the prevalence of comorbidities in alcohol dependence and specific mental health conditions (Cox et al., 1990[22]; Winokur, 1983[23]), other work has shown that the consumption of alcohol in and of itself can lead to the development of anxiety and depressive symptoms. In these instances, symptoms of mental health conditions will abate as consumption decreases (Schuckit, 1996[24]). In other cases, antidepressants can be an effective treatment for those experiencing alcohol dependency and depressive episodes (Sullivan, Fiellin and O’Connor, 2005[21]). Care should be taken, however: some anti-depressants can worsen depressive symptoms and/or suicidal ideation if consumed alongside alcohol (Mayo Clinic, 2017[25])

Individuals with mental health conditions smoke tobacco at higher rates than the general public, and they are also more susceptible to morbidity and mortality from smoking-related illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases and cancer (Lawrence, Mitrou and Zubrick, 2009[26]). Longitudinal studies conducted in the United States and Australia found that adults who had been diagnosed with a mental health disorder (including schizophrenia, anxiety disorders or depression) were almost twice as likely to smoke; conversely, smokers are more likely to have a diagnosed mental health condition. Among smokers, those with a mental health condition smoke more cigarettes per day compared to those without. Researchers are divided as to the causal direction of the relationship, but generally agree that there are factors moving in both directions. One theory is that mental ill-health can lead to smoking as a form of self-medication (Khantzian, 1997[27]): depressive and anxiety symptoms in teenagers have been found to be predictors to taking up smoking in subsequent years (Lawrence, Mitrou and Zubrick, 2009[26]). Similarly, smoking may be perceived as alleviating the side effects of certain psychotropic drugs (Desai, Seabolt and Jann, 2001[28]). However, although nicotine may provide temporary relief, experts have found that smoking tobacco can lead to higher overall levels of anxiety and stress in the long-term (Picciotto, Brunzell and Caldarone, 2002[29]). A large-scale study in the United Kingdom found evidence supporting a causal link between smoking behaviour and the onset of schizophrenia and depression. A possible explanation is that the nicotine in cigarettes disrupts dopamine and serotonin transmission in the brain; this type of neurotransmission dysfunction is linked with both schizophrenia and depression (Wootton et al., 2020[30]). Another theory is that the impact of nicotine on the dopaminergic system of the brain may help to improve cognitive delays and/or the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, resulting in improved clarity and in part explaining some of the self-medication theories (Ding and Hu, 2021[31]).

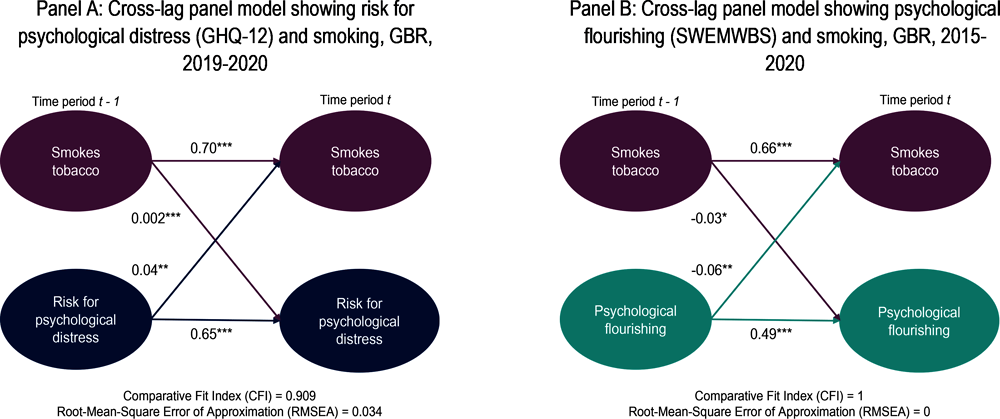

The bidirectional relationship between smoking and mental health is illustrated in Figure 3.3 below. Unlike physical health outcomes (Figure 3.2), the magnitude of the correlations is smaller, though still significant. Previous experience of poor mental health (both psychological distress, shown in Panel A, as well as low levels of positive mental health, shown in Panel B) is associated with the current likelihood of smoking. The reverse relationship is also significant (previous experience of smoking impacts current mental health), although the influence of mental health on smoking is at least twice as strong as vice versa.

Figure 3.3. The influence of mental health on smoking behaviour is stronger than vice versa

Note: Model is adjusted for the following time-invariant covariates: age, sex, education, ethnicity, urban/rural. Coefficients are standardised. Smokes tobacco is defined as those answering “yes” to the question, “Do you smoke cigarettes?” Data included come from waves 9 and 10 (Panel A) and waves 7 and 10 (Panel B) of the UKHLS survey; waves are different across panels given data limitations. GHQ-12 measures psychological distress on a scale from 0 (least distressed) to 12 (most distressed). SWEMWBS measures positive mental health, ranging from 9.5 as low psychological well-being to 35 as mental flourishing. All analyses were performed using Mplus and the R “MplusAutomation” package. More details on the models can be found in the Reader’s Guide.

Source: University of Essex (2022[18]), Understanding Society: Waves 1-11, 2009-2020 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009 [data collection], 5th Edition. UK Data Service, https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/.

Box 3.1. Policy focus: Physical health interventions that also improve mental health outcomes

Better integration of physical and mental health care

Given the strong interlinkages between physical and mental health outcomes, it is important that health services are integrated. This entails both the provision of mental health services in primary care settings (i.e. better training in mental health care for general practitioners) as well as routine physical health checks for those experiencing a mental health condition.

In 2015, the OECD Council published the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy under which member states affirmed their commitment to a multi-sectoral, integrated approach to mental health care (OECD, 2015[32]; 2021[7]; 2021[33]). This approach engages all stakeholders involved in population mental health – not just those working in physical health care, but also in social policy, labour and education. However, as a part of the implementation plan there are examples of specific policies to better integrate physical and mental health care (OECD, 2021[33]). These include:

Expanding the size of the mental health care workforce

Shifting from hospital- to community-based mental health service provision (see also Box 2.1)

Increasing the availability and access to digital technologies in the mental health sphere, including: apps to promote mental health through strengthening skills relating to mindfulness, self-managing and resilience; telehealth services for those experiencing mental distress; and electronic cognitive behavioural therapy (eCBT) for those with mild to moderate mental health conditions

Increasing the capacity of general practitioners to identify, treat and/or refer those with mental health conditions

Including routine physical health checks for mental health service users, for example, by updating clinical guidelines, adding physical health care to individual care plans, and/or better liaising services in inpatient settings (OECD, 2021[7]).

Encouraging physical activity to combat mental ill-health

Increased physical activity has been shown to improve affect and mood, improve symptoms for those dealing with mental health conditions – especially depression and anxiety – and provide resilience to future physical health threats – both non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and obesity, but also viruses such as the common cold. Recent work from the OECD provides examples of policy options to increase population physical activity (OECD/WHO, 2023[34]):

Setting-specific programmes in:

Schools: Educate students on the importance of engaging in physical activity and implement well-designed physical education classes. The latter have benefits beyond physical health and are associated with improved socio-developmental skills and better school performance.

Workplaces: Incentivise the reduction of sedentary behaviour throughout the workday and promote more active modes of transport for commuting to work (e.g. cycling, walking).

Health care system: Interventions for health care workers include advising patients on the benefits of physical activity through counselling or behavioural prescribing.

Increasing access to, and the affordability of, sports facilities.

Implementing urban design, environment and transport policies to facilitate the ease of physical activity. This includes interventions such as creating green spaces (parks, hiking trails), blue spaces (beaches, swimming areas) and new transit infrastructure (bike lanes, walking paths and sidewalks).

Communication and information campaigns to broadcast the benefits of physical activity to the broader public. One such campaign is the World Health Organization’s Global Action Plan on Physical Activity from 2018-2030. It calls on countries to decrease physical inactivity among the adult and adolescent populations by 15% to help lessen the burden of non-communicable diseases and to improve population mental health conditions (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019[19]).

For additional policy examples in the area of physical health, refer to Fit Mind, Fit Job (2015[35]).

3.2. Knowledge and skills and educational attainment

Knowledge and skills encompass the cognitive abilities gained over a lifetime. Those with mental health conditions tend to perform worse in school and have lower levels of educational attainment than do the general population – however, in comparison to physical health, the causal mechanisms behind these relationships are less well studied. Performance in school and eventual educational attainment are highly correlated with other well-being outcomes, including socio-economic status, the educational attainment of one’s parents, and the home environment. As this and the previous chapter have shown, each of these correlates are themselves predictors of poor mental health, and themselves shape mental health outcomes.

Because mental health conditions typically first present themselves during early adolescence – 50% of mental health problems are established by age 14 (Kessler et al., 2005[36]) – and because all young people spend a significant amount of time in schooling, school-based interventions can be a particularly effective way of promoting mental health. However, educational spaces are not just for young people: in fact, the act of learning in and of itself has been shown to be a form of promoting positive mental health and providing psychological resilience, making adult lifelong learning a good way to foster positive mental health (Box 3.2).

The interplay between mental health and school performance

Both mental ill-health and positive mental health are associated with poorer academic performance. Students with mental health conditions are 35% more likely to have repeated a grade and are at greater risk for dropping out of school early (OECD, 2021[7]). Lower levels of life satisfaction have also been shown to be associated with higher rates of truancy and early drop-out (OECD, 2017[37]). At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the two years following, millions of students across the OECD had their schooling disrupted as the majority of primary, secondary and tertiary institutions switched to remote learning. The hardest hit were students from low socio-economic households, who do not have quiet places to study and do not have Internet or computers at home, and – importantly – whose parents may not be able to support their learning to make up for the lack of in-person support from teachers (OECD, 2021[38]). As this and the previous chapters have shown, young people and residents from households with these characteristics are more at risk for poor mental health outcomes, through income, labour market and housing channels, thus the pandemic likely exacerbated the loss of learning and poor school performance for these groups.

Having poor mental health can make it more difficult for students to perform well in school. Adolescents with clinically diagnosed depression have been found to perform less well in school, and have lower levels of educational attainment, than do their peers without a diagnosis (Asarnow et al., 2005[39]); the same is true for students with symptoms (as opposed to diagnoses) of depression or behavioural issues. One potential pathway is that students with depression are more likely to skip classes or turn in incomplete assignments, both of which are associated with lower grades (Duncan, Patte and Leatherdale, 2021[40]). Students with mental health conditions are also more likely to have lower levels of academic self-efficacy: more likely to feel overwhelmed by workloads, to be restless and unable to focus, and to engage in procrastination behaviours (Grøtan, Sund and Bjerkeset, 2019[41]). Depression is associated with disrupted sleep patterns and poorer sleep quality (Pandi-Perumal et al., 2020[42]); fatigue makes it difficult to focus on schoolwork and perform well academically. Some research has found links between depression and dysfunction in the parietal cortex, which inhibits visuospatial processing and mathematical abilities (Nelson and Shankman, 2016[43]).

An outcome for mental ill-health that is particular to the school setting is anxiety relating to school performance and schoolwork. OECD research has shown that 15-year-old students with high levels of anxiety about schoolwork, homework and tests perform less well on tests in science, mathematics and reading (OECD, 2017[37]). High levels of anxiety surrounding academic performance can disrupt complex working memory processes, which then lead to worse performances on tests and assessments (Owens et al., 2012[44]).

At its extreme, school-related anxiety can result in school refusal, also known as emotionally-based school avoidance (EBSA) or school phobia. Distinct from truancy, in these instances children and adolescents remain at home due to overwhelming feelings of emotional distress relating to school attendance (Heyne et al., 2012[45]; Hornby and Atkinson, 2002[46]; Thambirajah, Grandison and De-Hayes, 2008[47]). The causes of school refusal are varied, and can stem from anxiety relating to school assignments (West Sussex County Council, 2022[48]), but also to a stressful or unstable home life (Hersov, 1960[49]; Hornby and Atkinson, 2002[46]), underlying mental health conditions including anxiety or mood disorders (Heyne et al., 2012[45]), genetics or neurobiological processes (Hornby and Atkinson, 2002[46]), and/or being the victim of bullying behaviours (Astor et al., 2002[50]). School refusal is associated not only with worse academic performance, but can also hamper socio-emotional growth, and may be associated with mental health challenges later in life (Heyne et al., 2012[45]). Furthermore, school refusal is often a symptom of underlying mental health conditions; although school-based interventions can be an effective way of promoting mental flourishing in young people (Box 3.2), students who avoid school – and who may most need these services – cannot, by definition, access these programmes. Research has shown that cognitive behavioural therapy can be an effective way of getting these students back into school (West Sussex County Council, 2022[48]; Hornby and Atkinson, 2002[46]), sometimes in combination with medication, family therapy and additional school supports (Heyne, 2022[51]).

The relationship between mental health and academic achievement can also move in the opposite direction, with poor performance in school exacerbating, or causing, mental health conditions. Performing poorly in school is associated with low levels of self-esteem; low self-esteem is associated with greater risk for mental distress, including suicidal ideation, poorer physical health and criminality in adulthood (Trzesniewski et al., 2006[52]; Nguyen et al., 2019[53]). Evidence has shown that children with reading problems are more likely to develop higher levels of depressive symptoms (Maughan et al., 2003[54]); adults with reading challenges are also more likely to have symptoms of depression and lower self-esteem (Eloranta et al., 2019[55]).

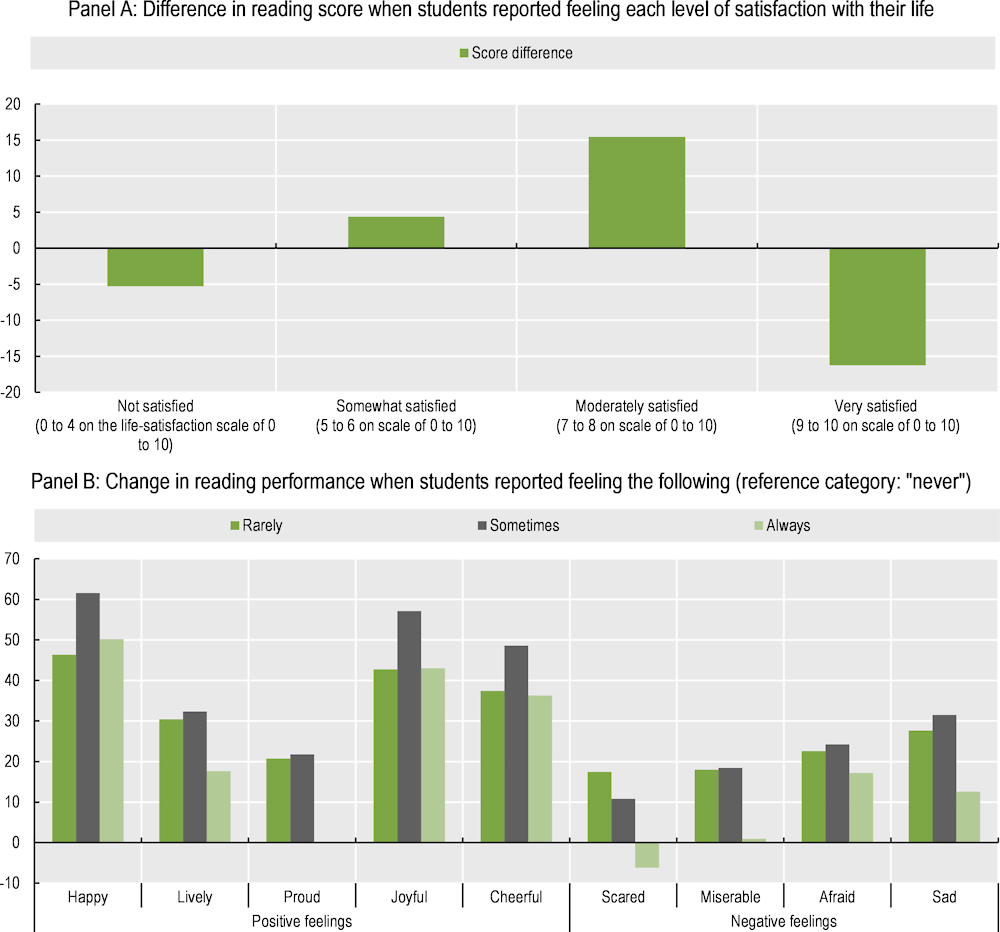

However, the link between positive mental health and knowledge acquisition is less clear, with findings suggesting that emotionally balanced students – as opposed to those with extreme emotions, either positive or negative – perform better in school. When using subjective measures of academic performance, rather than objective (i.e. test scores), research shows a positive association with life satisfaction (OECD, 2017[37]; 2019[56]). Yet although some literature has shown that academic achievement can predict higher levels of future life satisfaction, OECD research shows that high- and low-achieving students have similar levels of life satisfaction (OECD, 2017[37]; 2019[56]). Using the 2018 PISA reading scores, OECD researchers found that reading scores were highest for 15-year-old students who were “somewhat” or “moderately” satisfied with their lives, while the extreme ends of the distribution – both very satisfied and very unsatisfied with life – had poorer reading scores (Figure 3.4, Panel A). The relationship between affect and reading skills follows a similar pattern (Figure 3.4, Panel B). Students who report few negative feelings (rarely or sometimes feeling scared, afraid, miserable or sad) had higher reading scores than did both students who never felt negative feelings and those who always did (OECD, 2019[56]).

Peer behaviour – especially bullying and social isolation – are also major risk factors for both mental health and learning outcomes. Grade repetition can disrupt a student’s social group, thereby removing an important resilience factor for positive mental health (OECD, 2021[33]): research has shown that youths who feel isolated at school are more likely to subsequently develop depression or substance use behaviours (OECD, 2017[37]; Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph, 2012[57]; Rigby and Cox, 1996[58]). Bullying at school not only can impact educational outcomes, but also can lead to an increased likelihood of children developing symptoms of anxiety, depression and eating disorders; these negative impacts can persist into adulthood (OECD, 2017[37]). Bullying is associated with worse outcomes for both the victims and the perpetrators. Adolescents who self-reported bullying behaviour were more likely to have low self-esteem (Rigby and Cox, 1996[58]); those engaging in bullying behaviour are also more likely to engage in certain kinds of substance use, including alcohol consumption and drug use (Morris, Zhang and Bondy, 2006[59]; Radliff et al., 2012[60]) (refer to Box 3.2 for information on anti-bullying interventions).

Figure 3.4. Students who are more emotionally balanced perform better on reading tests than do students who report more extreme emotions – either negative or positive

Note: Panels A and B, taken from (OECD, 2019[56]), refer to Figure III.11.6 and Figure III.12.3, respectively. Panel A shows the difference in performance on reading assessments for students who report being “not satisfied”, “somewhat satisfied”, “moderately satisfied” or “very satisfied” with life; each group is compared to all of the others combined. Results control for students’ and schools’ socio-economic characteristics. Panel B shows the change in reading performance for students who report feeling each emotion “always”, “sometimes” or “rarely”. Each group is compared to the group of students who report “never” feeling each emotion.

Source: OECD (2019[56]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en.

Mental health and lifetime educational attainment

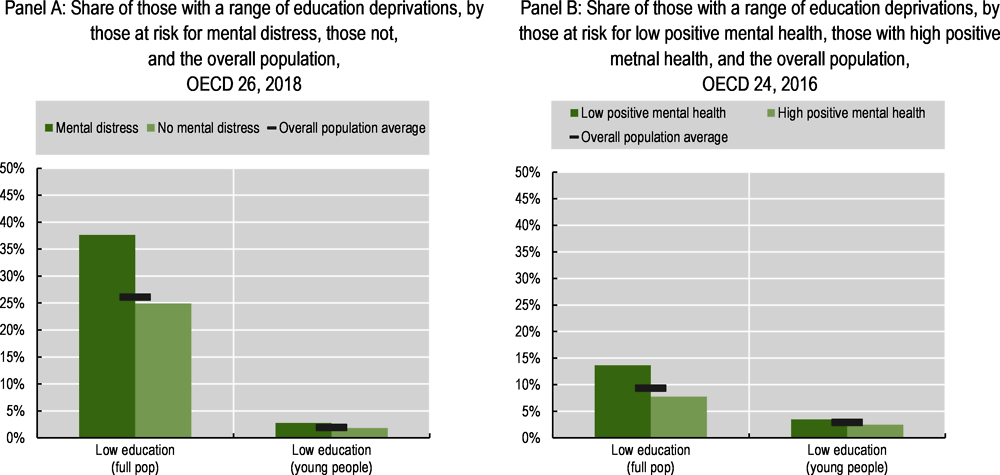

There is a negative correlation between mental health outcomes and educational attainment: those diagnosed with a mental health condition, or at risk for poor mental health, are less likely to pursue higher education and are less likely to pursue adult education or workplace training. Participation in lifelong learning or adult skills training programmes is influenced by learning attitudes shaped in adolescence (OECD, 2021[61]); because those with poor mental health have worse educational experiences as young people – more likely to drop out, less likely to perform well in school – they are also less likely to continue pursuing educational opportunities, even informal ones, as an adult. This relationship can be seen in Figure 3.5, which shows the prevalence of low educational attainment (defined here as having less than a secondary degree) for those with and without poor mental health.

Figure 3.5. Those at risk for poor mental health are more likely to have lower levels of educational attainment, and the differences increase with age

Note: On the left, risk of mental distress is defined using the Mental Health Index-5 (MHI-5) tool. On the right, positive mental health is defined using the World Health Organization-5 (WHO-5) tool. Refer to the Reader’s Guide for full details of each mental health survey tool, for how each well-being deprivation is defined and for which countries are included in each OECD average.

Source: Panel A: OECD calculations based on the 2018 European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (n.d.[62]) (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions; Panel B: OECD calculations based on the 2016 European Quality of Life Surveys (EQLS) (Eurofound, n.d.[11]) (database), https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-quality-of-life-surveys.

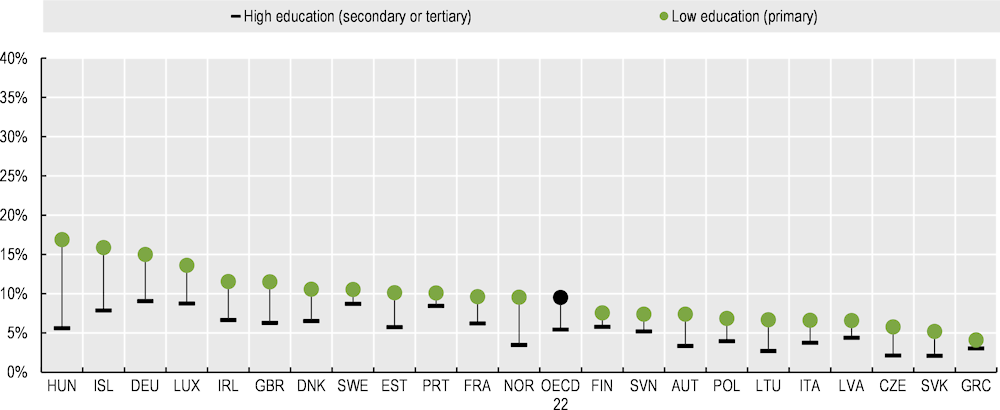

The relationship between mental ill-health and educational attainment is well established. For example, those with lower levels of education are more likely to report chronic depression (OECD, 2021[7]). Data from 22 European OECD countries show those with less than a secondary degree have a four percentage point greater risk for major depressive disorder, as compared to those with a secondary or tertiary degree (Figure 3.6). Educational attainment is highly correlated with socio-economic status: those coming from lower-income households, with parents who themselves have lower levels of education, are less likely to excel in school, more likely to fail to graduate, and less likely to achieve a tertiary degree. Multiple studies have shown that adolescents with depressive symptoms, or who engage in substance use such as cannabis and tobacco, are more likely to work in jobs that require lower degree accreditation, and they are more likely to neither be in employment, education nor training (NEET) (Minh et al., 2021[63]; Baggio et al., 2015[64]). Depressive symptoms can lead to school burnout, with affected adolescents either dropping out of school early or choosing not to pursue higher education (Salmela-Aro, Savolainen and Holopainen, 2009[65]; Tuominen-Soini and Salmela-Aro, 2014[66]).

Figure 3.6. Having less than a secondary degree is associated with a greater risk for major depressive disorder

Note: The figure compares the mental health outcomes of those with low levels of education (defined as primary only) and those with high levels of education (defined as secondary or tertiary).

Source: OECD calculations based on European Health Interview Survey (EHIS) wave 3 data (Eurostat, n.d.[10]) (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:European_health_interview_survey_(EHIS).

Longitudinal research has shown that the relationship is bidirectional, in that low educational attainment can lead to depression. A study in the United States found that at the age of 40, those with lower levels of education were more likely to be depressed than those with higher levels of education, driven primarily by educational aspirations and expectations. Those who in adolescence had low expectations but high aspirations were particularly at risk for later-in-life depression (Cohen et al., 2020[67]). Other research has shown that respondents with higher subjective social status – relating to their self-reported place in social hierarchies, on indicators of wealth, education level and employment – had a lower likelihood of having a range of mental health conditions (Scott et al., 2014[68]); however, the evidence here cannot disentangle subjective assessments of education from those of material conditions (income, employment).

The relationship between positive mental health and educational attainment is less direct. OECD research has shown a strong positive correlation between life satisfaction and education level; however, this relationship becomes insignificant once other factors (such as income, physical health, social trust) have been controlled for (OECD, 2013[2]; Boarini et al., 2012[12]). This suggests that educational attainment may primarily impact positive mental health through its effects on other aspects of well-being (Boarini et al., 2012[12]). Even still, other research has shown that the act of learning can itself bolster mental health, especially for adults: participating in lifelong learning programmes can strengthen adults’ psycho-social resources and improve their mental health (OECD, 2021[38]). This is true for both formal job accreditation programmes, as well as for informal learning and taking leisure and interest courses (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Policy focus: Knowledge and skills interventions that also improve mental health outcomes

School-based interventions for mental health prevention and promotion

Schools are particularly well suited for mental health prevention and promotion programmes. Many mental health conditions first exhibit in adolescence (Kessler et al., 2005[36]), when outcomes can be significantly improved through early diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, a range of evidence shows that interventions earlier in a child’s life have long-lasting impacts, therefore an early focus on healthy mental habits can lead to long-term positive outcomes. And finally, all young people spend a significant amount of their time in education, making schools a particularly appropriate venue for promoting socio-emotional learning (OECD, 2021[7]).

While the exact form of mental health interventions can vary, a few examples of school-based initiatives to promote mental health include:

Anti-bullying programmes: Bullying, and cyber-bullying, can have detrimental impacts on students’ mental well-being, and lead to poorer performance in school (OECD, 2018[69]; OECD, 2017[37]). The KiVa anti-bullying programme, which was designed in Finland but has since been used in pilot studies in a number of OECD countries, including the United Kingdom, Estonia, Italy, the United States and New Zealand, has been shown to successfully decrease bullying, victimisation, and symptoms of anxiety and depression among students through online and in-person lessons and targeted actions for those involved in bullying (OECD, 2021[7]).

Mental health awareness campaigns: These campaigns, which are designed to raise mental health literacy among young people and to reduce stigma, are some of the most common school-based initiatives. They are typically universal, in that all students receive the same programming regardless of their baseline risk for mental distress. Preliminary findings have suggested the programmes are effective in raising student self-esteem and increasing help-seeking behaviours, and they are largely viewed by the teachers implementing the programmes as a positive experience (Punukollu, Burns and Marques, 2019[70]). However, more rigorous research designs are needed to fully investigate whether the outcomes are significant and long-lasting (Salerno, 2016[71]). The mental health of teachers also matters – a study in the United States found that primary school teachers at risk for depression were less effective at maintaining a learning environment in their classrooms, with lower level learners most impacted (Mclean and Connor, 2015[72]). Most OECD countries currently have some form of mental health awareness and anti-stigma programme in place in school systems: in a 2020 OECD survey, 20 out of 29 countries reported that teachers receive some form of mental health training (OECD, 2021[7]).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT): CBT combines aspects of behavioural and cognitive psychology to challenge cognitive beliefs to enable people to better regulate their emotions and develop coping strategies to solve problems and face adversity. School-based CBT, administered by either school staff or external providers, has been found to be an effective way to decrease symptoms of both depression and anxiety among young people (Kavanagh et al., 2014[73]; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017[74]).

Incorporate social and emotional learning, resilience and the ability to thrive into national curricula

Beyond the specific school-based interventions outlined in the above section, school systems can directly integrate social and emotional learning (SEL) into the national curricula. Broadly speaking, SEL focuses on building up young peoples’ skill sets in recognising and managing their emotions so as to build and maintain positive relationships, enable responsible decision making and an ability to deal effectively with interpersonal conflicts (Durlak et al., 2011[75]). Evidence-based reviews of SEL have found that these programmes can improve students’ mental health, attitudes towards themselves and peers, and self-confidence. They can also help to prevent bullying, aggression and conflict, and may in some instances improve academic performance. In the long-term they are associated with crime reduction, improved labour market outcomes and lifetime earnings (Barry, Clarke and Dowling, 2017[76]).

As a part of its 2017 Mental Health Strategy, and overall Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) approach, the Scottish government has strengthened its provision of personal and social education (PSE) in local authority schools. The goal is to provide children and young people with the necessary tools to enable their physical, mental, social and emotional health to flourish. Schools are encouraged to tailor the curricula to local contexts, in consultation with the students themselves (Scottish Government, 2019[77]; Healthy Schools Scotland, 2022[78]).

Lifelong learning

Engaging adults in lifelong learning has been shown to have a range of positive mental health outcomes. Lifelong learning can take many forms. It may take place in a training facilities – such as a school, training centre or the workplace – and be the result of a formal – i.e. an accreditation process – or informal – i.e. non-accreditation process, such as a series of conversations with colleagues or peers (OECD, 2021[61]). Alternatively, lifelong learning can take the form of leisure and interest courses (Duckworth and Cara, 2012[79]). Continuously learning new skills can be beneficial for one’s career, keeping individuals competitive in a changing and evolving labour market. Lifelong learning can also be an important part of the just transition, by reallocating labour and addressing skills gaps to new green jobs (OECD, 2021[38]).

However, the benefits of these programmes go beyond mere skills acquisition and a greater likelihood for employment. Adults who participate in these programmes are more likely to have higher self-esteem, a stronger sense of identity and improved social integration, all of which promotes mental resilience in the face of potential adverse shocks (OECD, 2021[38]; Manninen et al., 2014[80]; Hammond, 2004[81]). A study in the United Kingdom found that non-accredited learning is better for mental health than accredited learning: the former can lower the risk for depression and increase life satisfaction and feelings of self-efficacy, while the latter has no significant effects (Duckworth and Cara, 2012[79]).1 These programmes can be particularly impactful for at-risk groups, including those with lower levels of education or the elderly (OECD, 2021[38]). Learning and cognitive activities have been shown to be neuro-protective for elderly populations against cognitive decline and/or dementia (Reynolds, Willment and Gale, 2021[82]); participation in learning activities can also promote social interaction, thereby preventing loneliness and protecting against depression (Kotwal et al., 2021[83]). Those with the lowest levels of education often see the largest benefits from these programmes, including seeing positive changes in motivation. Lifelong learning can therefore be a way of improving both mental health and learning outcomes (Manninen et al., 2014[80]).

For additional policy examples in the area of knowledge and skills, including easing the school-to-work transition for young people experiencing mental ill-health, see Fit Mind, Fit Job (2015[35]).

Note: 1. It is worth noting that other research using a different dataset from England found an opposite pattern: risk of depression was lowered only when participants in learning were doing so for a qualification. Learning without obtaining a qualification had no impact on depression risk (Jenkins, 2012[84]).

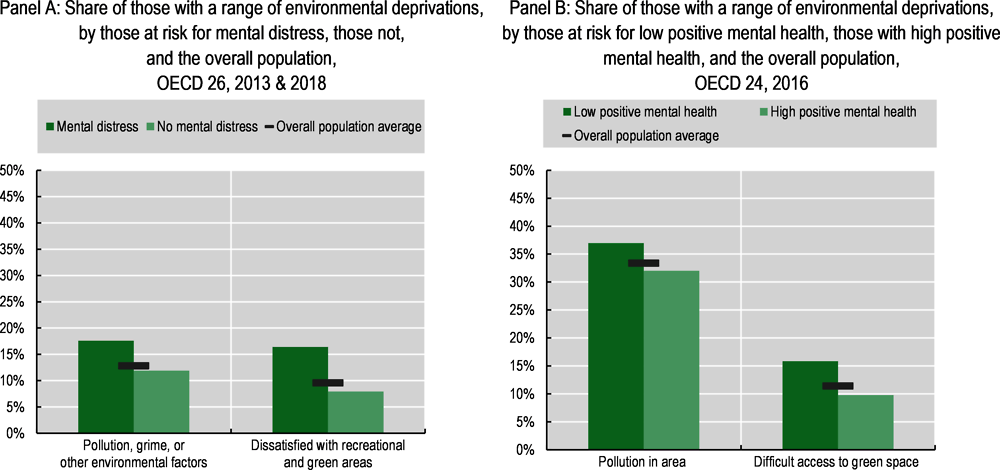

3.3. Environmental quality and natural capital

The relationship between our mental well-being and the environment is well established, with improved mental health outcomes associated with greater access to clean air and more time spent in nature (Bratman et al., 2019[85]). With a larger share of the population living in urban areas,2 ensuring equitable access to unpolluted natural spaces is all the more important in promoting positive mental health (Frumkin et al., 2017[86]). Figure 3.7 illustrates that those with worse mental health outcomes – both in terms of mental ill-health as well as positive mental health – are more likely to live in neighbourhoods with pollution (Panels A and B) and are less likely to have access to green spaces (Panel B), or to be satisfied with them (Panel A).

The implications of climate change – huge losses in biodiversity, ever increasing extreme weather events – loom large over all domains of well-being, with mental health no exception. Aside from putting a strain on already limited mental health care systems and exacerbating a range of mental health conditions, climate change has also given rise to new forms of ill-health, with terms such as “eco-anxiety” coined to capture this unique form of distress.

Figure 3.7. People with worse mental health outcomes are more likely to live in polluted areas and have worse access to, and be less satisfied with, green spaces

Note: In Panel A, risk of mental distress is defined using the Mental Health Index-5 (MHI-5) tool. In Panel B, positive mental health is defined using the World Health Organization-5 (WHO-5) tool. Refer to the Reader’s Guide for full details of each mental health survey tool, for how each well-being deprivation is defined and for which countries are included in each OECD average.

Source: Panel A: OECD calculations based on the 2013 and 2018 European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (n.d.[62]) (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions; Panel B: OECD calculations based on the 2016 European Quality of Life Surveys (EQLS) (Eurofound, n.d.[11]) (database), https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-quality-of-life-surveys.

Air and noise pollution can worsen mental health, especially in children

There is a growing literature showing that exposure to air pollution, especially at a young age, can lead to future mental health problems. Prolonged exposure to high levels of air pollution has been shown to be a risk factor for a range of mental health conditions, including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use, alcohol or tobacco dependence, psychotic disorders and suicidal ideation (Petrowski et al., 2021[87]; King, 2018[88]; Shin, Park and Choi, 2018[89]; Vert et al., 2017[90]; Pun, Manjourides and Suh, 2017[91]).3 A longitudinal study in the United Kingdom found that children who were exposed to high levels of traffic-related pollution at a young age were more likely to develop mental health conditions (including substance use, alcohol or tobacco dependence, and thought disorder symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions) in early adulthood (Reuben et al., 2021[92]). A study in Sweden found similar patterns, showing that young children who live in areas with higher concentrations of pollution are more likely to receive psychiatric medication (Oudin et al., 2016[93]).

High levels of air pollution can also adversely affect positive mental health (OECD, 2013[2]; Boarini et al., 2012[12]), and these impacts persist. Past exposure to fine particulate matter can negatively impact life satisfaction years later; evidence does not suggest that people adapt to high levels of pollution (Menz, 2011[94]). Conversely, low levels of air pollution are associated with higher levels of positive mental health – higher life satisfaction, greater self-esteem and more stress resilience (Petrowski et al., 2021[87]).

Although the strong correlation between air pollution and mental health outcomes has been established, the causal pathways are still being explored. It is hypothesised that air pollution impacts mental health outcomes through a range of biological and social channels. On the first, fine particulate matter has been shown to cause a range of physical health problems (OECD, 2021[95]), including to the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. There is a significant and growing literature outlining the ways in which air pollutants affect brain health and function, via pollutant-induced inflammation, stress hormones and oxidative stress (Thomson, 2019[96]). Inflammatory responses have been linked to certain psychiatric conditions, including depressive and anxiety symptoms and behaviours, therefore the neuroinflammatory response to O3 or PM2.5 exposure may in some cases be a contributing factor to the onset or worsening of certain mental health disorders (Zundel et al., 2022[97]). Similarly, other evidence has suggested that the interaction of certain genes with heavy metal air pollutants is linked to the development of conditions such as schizophrenia (King, 2018[88]). Air pollution can also affect behaviour: people who live in heavily polluted areas are less likely to spend time outside, or engaging in physical activity (Bos et al., 2014[98]), both of which are protective factors for mental health. Similarly, within an urban environment, air pollution is often worse in lower socio-economic neighbourhoods where residents are more likely to be poor and have worse employment outcomes and housing conditions (Brunekreef, 2021[99]; Kerr, Goldberg and Anenberg, 2021[100]) – all of which contribute to poor mental health (see Chapter 2).

It is not just air pollution that harms mental health; noise pollution is associated with worse health outcomes – both physical and mental – including sleep disruption, hypertension, hearing problems, cognitive impairment, heart disease and mental health conditions (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018[101]). In terms of psychological effects, studies on populations of industrial workers have found that those employed in workplaces with high levels of noise experienced nausea, headaches and mood changes, including feeling argumentative, anxious and/or depressed (Stansfeld and Matheson, 2003[102]). Some studies have found direct associations between psychiatric hospital admission rates and living in areas with high rates of aircraft noise (Abey-Wickrama et al., 1969[103]; Meecham and Smith, 1977[104]); however, this relationship is not always replicated in other studies (Stansfeld and Matheson, 2003[102]). There is also a robust literature on the negative impacts of noise pollution on positive mental health, showing that it reduces life satisfaction and happiness (Fujiwara and Lawton, 2020[105]; van Praag and Baarsma, 2005[106]); a study using data from 28 European countries found that the monetary value required to compensate individuals for the burden of living in an area with severe noise pollution is around EUR 172 per month (Weinhold, 2013[107]).

Access to nature serves as a resilience factor for mental health

Green spaces (an area covered in vegetation, such as parks, gardens, fields, forests) and blue spaces (lakes, ponds, oceans and water features such as city fountains) can serve as protective factors for mental health. Research in a number of OECD countries has established a relationship between living in areas with less green space and a range of mental health conditions including depression, anxiety and general distress, even after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics such as sex, age, education and income (Astell-Burt and Feng, 2019[108]; Alcock et al., 2014[109]). For example, a large-scale Danish study found that children who lived in neighbourhoods with low levels of green space were over 50% more likely to develop a range of psychiatric disorders (including depressive disorders, mood disorders, substance use, eating disorders, etc.) as adults, even when controlling for other known risk factors (Engemann et al., 2019[110]).

Time spent in nature is a protective factor for mental health, with positive mental health associated with greater access to, and use of, green spaces. People who spend more time in nature, or who have easy access to green or blue spaces, have higher levels of psychological and emotional well-being, less stress and higher positive affect (Mayer et al., 2008[111]; Crouse et al., 2021[112]; Crouse et al., 2018[113]; Astell-Burt and Feng, 2019[108]; Bratman, Olvera-Alvarez and Gross, 2021[114]; White et al., 2021[115]). Experiences during pandemic lockdowns and/or social distancing policies further underscored these relationships: evidence from England, France and Japan showed that people who were able to spend time in nature, or who had views of green spaces, were significantly happier and had higher levels of life satisfaction, even after controlling for socio-demographic and lifestyle differences (OECD, 2021[38]). For children and young people, some research has shown that, when integrated into areas around schools, nature may play a role in buffering against stress and potentially improving cognitive functioning and academic performance (Fyfe-Johnson et al., 2021[116]; Tallis et al., 2018[117]; Dadvand et al., 2015[118]).

Longitudinal studies unpacking the relationship between mental health and nature suggest that moving to areas with more green space can improve mental health outcomes in the long term (Alcock et al., 2014[109]). Other research has shown that a walk in nature can improve emotional regulation, increase positive affect, decrease negative affect and relieve symptoms of stress and anxiety (Bratman et al., 2015[119]; Korpela et al., 2018[120]; Berman et al., 2012[121]), and that prolonged time spent in nature can alleviate the burden of mental health conditions such as PTSD, mood disorders and chronic stress (Summers and Vivian, 2018[122]) (Box 3.3). One study fitted participants with EEG devices to monitor their emotions during a walk in nature; it found that they were more likely to experience meditative brain waves and less frustration-related emotions, as compared to participants who walked through non-natural spaces (for example, a shopping mall) (Aspinall et al., 2015[123]).

As with air and noise pollution, the causes of these effects are likely to be a combination of physiological and psycho-social factors. Studies have linked positive mental health outcomes resulting from time spent in nature to feelings of connectedness with nature (White et al., 2021[115]), the inducement of awe (Anderson, Monroy and Keltner, 2018[124]) and the perceived restorativeness of natural settings (Hartig and Mang, 1991[125]). Other research has demonstrated that exposure to nature improves cognitive function through the restoration of directed attention (Kaplan, 1995[126]) and the reduction of stress through psychophysiological mechanisms (Ulrich et al., 1991[127]). Time spent in nature can also improve physical health, both directly and indirectly. On the former, research has shown that exposure to nature may enhance immune function (Kuo, 2015[128]) and can shorten recovery periods following surgery (Ulrich, 1984[129]). More indirectly, green spaces are likely to be less polluted and have more attenuated heat island effects4 than built-up urban spaces: the reduction of pollution (air and noise) and lowered heat levels can lead to improved mental health outcomes (Frumkin et al., 2017[86]). In terms of psycho-social pathways, access to natural areas can affect human behaviour. People with greater access to green space are more likely to exercise, and those with access to public parks are more likely to interact with members of their community, thereby experiencing less loneliness and a greater sense of social connection, all of which are protective factors (What Works Wellbeing, 2021[130]). Access to green space is often not equitable across ethnic, racial or socio-economic groups (OECD, 2021[38]; Dai, 2011[131]); lack of access to the benefits associated with natural spaces can then further widen these existing inequalities.

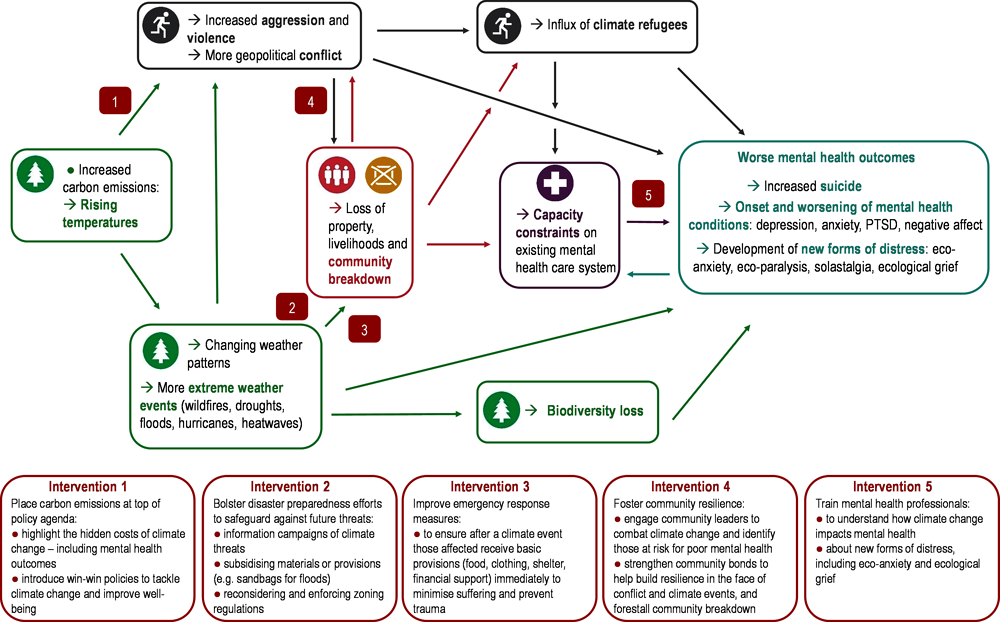

Climate change and mental health

Climate change is already affecting all aspects of well-being. Unless considerable action is taken to significantly mitigate temperature rise, it will continue to harm ecosystems, communities and livelihoods as heatwaves, wildfires, droughts and other extreme weather events increase in frequency; oceans warm and sea levels rise; and biodiversity plummets. A relatively new literature has emerged, highlighting the ways in which climate change is harming population mental health. This occurs through a range of channels: by exposing a larger number of people to traumatic events that exacerbate existing conditions or increase the risk for the development of a future condition; by therefore straining existing mental health care systems; and through the emergence of new forms of mental distress, including eco-anxiety, eco-paralysis, ecological grief and solastalgia.

Climate change thus affects mental health through direct and indirect pathways, each of which offer opportunities for potential policy interventions (Box 3.3); these channels are illustrated in Figure 3.8 below. As temperatures rise, the frequency of extreme weather events has been increasing, including droughts and desertification, heatwaves, wildfires, flooding, and hurricanes, among others. These climate disasters cause the loss of property, damage to crops and livestock, food and water insecurity and job losses, which can lead to economic insecurity, food insecurity, community breakdowns and fuel forced migration.

Figure 3.8. The devastation wrought by rising temperatures and increasingly common traumatic climate events is worsening mental health and straining system capacity

Source: Adapted from Lawrance et al. (2021[132]), Climate Change and the Environment, Grantham Institute, https://www.imperial.ac.uk/grantham/publications/all-publications/the-impact-of-climate-change-on-mental-health-and-emotional-wellbeing-current-evidence-and-implications-for-policy-and-practice.php.

Both the first and second-order effects of these climate events are damaging mental health. Climate disasters can also harm ecosystems and lead to biodiversity loss: humans have been found to report higher mental well-being in more biodiverse areas (Cox and Gaston, 2018[133]; Fuller et al., 2007[134]), and awareness of biodiversity gains may positively contribute to mood and affect (White et al., 2020[135]). Both the immediate and long-term effects of climate change destabilise the systems and conditions that are necessary to ensure good mental health and overall well-being. Furthermore, many of the most vulnerable communities have the greatest exposure to climate threats: in this way, climate change compounds pre-existing inequalities in well-being outcomes (Lawrance et al., 2022[136]).

As a larger share of the population experiences traumatic weather events, more and more people are developing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety and substance use (Lawrance et al., 2021[132]; Berry et al., 2018[137]; Hayes, Berry and Ebi, 2019[138]; Clayton et al., 2017[139]). Prolonged exposure to smoke from wildfires has been linked to heightened symptoms of anxiety, depression and decreased motivation, alongside physical health impacts such as respiratory issues (Humphreys et al., 2022[140]; OECD, 2023[141]). Wildfires also lead to severe air pollution, which as the preceding section showed has its own adverse impacts on mental health via systemic inflammation (Health Canada, 2022[142]). The physiological experiences of climate events – e.g. heat, smoke inhalation – lead to direct mental health challenges. Moreover, the flow-on effects on climate events can cause more trauma and stress, which in the long term can have severe consequences. A number of studies have found a relationship between rising temperatures and suicides, with some analyses estimating a 1% increase in the overall number of suicides for each degree Celsius increase above a designated threshold (Lawrance et al., 2021[132]; Burke et al., 2018[143]): evidence from India links elevated suicide rates to temperature rises, specifically during the agricultural growing season, as the rising heat lowers crop yields (Carleton, 2017[144]). Suicide and suicidal ideation can also increase in the aftermath of floods, hurricanes and wildfires (Hayes, Berry and Ebi, 2019[138]).

In addition to exposing the population to new mental health risks, extreme weather events can also worsen symptoms for those already experiencing a mental health condition. For example, in the United States, veterans with a mental health condition were 6.8 times more likely to suffer from exacerbated mental ill-health after Hurricane Katrina compared to veterans with no pre-existing mental health conditions (Dodgen et al., 2016[145]). In the aftermath of such an event, mental health services are likely to be disrupted, meaning those needing treatment may not have access to medical professionals or needed medication: all the more so if they are forced to migrate to a new area (Lawrance et al., 2021[132]; Berry et al., 2018[137]). Heat is also an important factor: a study in Canada found that people with schizophrenia were at three times higher risk of mortality than those without during the 2021 extreme heat event in Western North America (Lee et al., 2023[146]). Some psychoactive medicines may become ineffective during heatwaves (Hayes, Berry and Ebi, 2019[138]). Conversely, medications for some mental health conditions may impede the body’s ability to regulate its own temperature, which in the most severe cases, can result in death (Lawrance et al., 2021[132]).

Rising temperatures themselves are linked to increased violence and geopolitical conflict through their effect on mood and cognition. There is a robust literature showing that violent crimes increase in hotter months (Field, 1992[147]; Horrocks and Menclova, 2011[148]; Ranson, 2014[149]). A study in Los Angeles found that violent crime increased by 5.7% on days when temperatures reached or exceeded 30ºC (Heilmann and Kahn, 2019[150]). To contextualise this, climate modelling suggests that by 2050 the number of extreme heat days (defined as temperatures exceeding 35ºC) in Los Angeles County will triple or quadruple (Sun, Walton and Hall, 2015[151]): the implications for rising violence are concerning. One theory is that more people are out on the streets and interacting with one another – thus increasing the chances that any one interaction could turn violent (Field, 1992[147]). However, behavioural experiments have shown that hot temperatures can cause mood changes, leading individuals to become angrier and more aggressive (Almås et al., 2019[152]). Indeed, higher temperatures are associated with both increased road rage and greater use of profanity on Twitter (Kenrick and Macfarlane, 1986[153]; Baylis, 2020[154]).

High temperatures also disrupt sleep: disrupted sleep patterns or poor sleep quality are associated with a range of mental health conditions including affective disorders, addiction and schizophrenia, and some research suggests that prolonged experience of sleep disorders can contribute to the onset of mental health disorders (Lawrance et al., 2022[136]; Lõhmus, 2018[155]). Heat can also directly impact cognitive functioning: research from the United Kingdom finds that foetal exposure to high temperatures is associated with diminished cognitive functioning in adulthood (Bhalotra et al., 2022[156]), and evidence from China suggests high temperatures are associated with worse performance on cognitive assessments (Zhang, Chen and Zhang, 2022[157]). Exposure to heat is often inequitable. Research across major cities in the United States found that members of racial or ethnic minority groups live in areas with higher surface urban heat island (SUHI) intensity than do non-Hispanic white Americans (Hsu et al., 2021[158]). Other research has shown that in cities globally, within an urban area, the poorest neighbourhoods are those with the highest heat intensity (Chakraborty et al., 2019[159]). One way to address future inequalities in heat exposure is to increase access to urban green space: a study from The Lancet suggests that a 30% increase in tree coverage in European cities would have reduced premature deaths stemming from higher temperatures in 2015 by as much as one third (Iungman et al., 2023[160]).

There is growing evidence that climate events – including extreme heat, flooding or drought – may influence geopolitical conflicts, in addition to individual violent interactions (Burke, Hsiang and Miguel, 2015[161]). Extreme climate events can lead to crop failure, internal migration and rising food prices, which contribute to lack of trust between the population and government (Kelley et al., 2015[162]). Higher temperatures have also been found to be linked to an increase in terrorist attacks (Craig, Overbeek and Niedbala, 2019[163]). Conflict and violence have a devastating impact on mental health: service provision is greatly disrupted, and those experiencing trauma are at risk for developing PTSD and other serious mental health conditions (see Chapter 4 for a longer discussion on violence, safety and mental health).

As droughts, floods, fires and heatwaves make more areas uninhabitable, people will leave to find new inhabitable spaces, either within their own countries – the internally displaced population – or by crossing national borders. In 1995, climate refugees totalled around 25 million individuals worldwide; within the next few decades that number may increase eight-fold, reaching as high as 200 million by 2050 (Myers, 2002[164]; Lawrance et al., 2021[132]). This number may be an under-estimate, as climate indirectly affects refugee populations through increased conflict. For example, research has uncovered a connection between severe droughts Syria experienced in 2011, agricultural disruption and failure, increased political unrest and the onset and subsequent worsening of the civil war (Kelley et al., 2015[162]). This conflict has already displaced just under 14 million people over the past decade (UNHCR, 2022[165]).

This huge increase in climate refugees will greatly increase the pressure on existing mental health care systems, which are already strained. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 67% of working-age adults in OECD countries with mental distress who wanted mental health care reported having difficulties accessing it (OECD, 2021[7]). The pandemic further strained systems: in early 2020, mental health care services were disrupted to free up resources and space for COVID patients. And in the years since the pandemic, the population’s mental health has worsened, with rates of reported depression and anxiety symptoms spiking, especially among young people (OECD, 2021[38]). Therefore, systems that are already struggling to serve the population will be further burdened by rising rates of a range of mental health conditions, as more and more people experience extreme and traumatic weather events (Berry et al., 2018[137]).

Climate change has also brought about conversations on new types of mental health conditions, with some of the more common terms including eco-anxiety, eco-paralysis, ecological grief and solastalgia (Table 3.1). While there is disagreement as to whether these terms encapsulate truly new classifications of psychiatric disorders (Berry et al., 2018[137]), their use is becoming more common and accepted as policy makers recognise the growing concern of populations regarding the impacts of climate change on their lives and livelihoods (Clayton et al., 2017[139]; Health Canada, 2022[142]; Lawrance et al., 2021[132]). These feelings are brought about not only by personal fear of experiencing climate-related traumatic events, but also by the sheer scale of the problem, which can make individual action feel ineffective, and which is compounded by the lack of coordinated effort to find solutions on the part of national governments and the international community.

Table 3.1. Climate change has led to the introduction of new terms to describe its impact on population mental health

|

Term |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Eco-anxiety |

Eco-anxiety (or climate anxiety) refers to the anxiety people experience that is triggered by awareness of ecological threats facing the planet due to climate change (Albrecht, 2011[166]; Albrecht, 2012[167]). |

|

Eco-paralysis |

Eco-paralysis refers to the complex feelings of not being able to do anything grand enough to mitigate or stop climate change (Koger, Leslie and Hayes, 2012[168]). |

|

Solastalgia |

Solastalgia refers to the distress of bearing witness to ecological changes in one’s home environment due to climate change; conceptualised as feeling homesick when a person is still in their home environment (Albrecht, 2011[166]; Albrecht, 2012[167]). |

|

Ecological grief |

Ecological grief (or eco-grief) refers to distress related to ecological loss or anticipated losses related to climate change. These losses may relate to land, species, culture, or lost sense of place and/or of cultural identity and ways of knowing. Eco-grief can include loss and trauma related to specific hazards such as climate-related flooding or wildfires, or slow-onset climate change impacts such as rising global temperatures, drought, melting permafrost and sea-level rise (Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018[169]). |

Note: Taken directly from (Health Canada, 2022[142]), refer to Table 4.1.

Source: Health Canada (2022[142]), Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate — Advancing our Knowledge for Action, https://changingclimate.ca/health-in-a-changing-climate/.

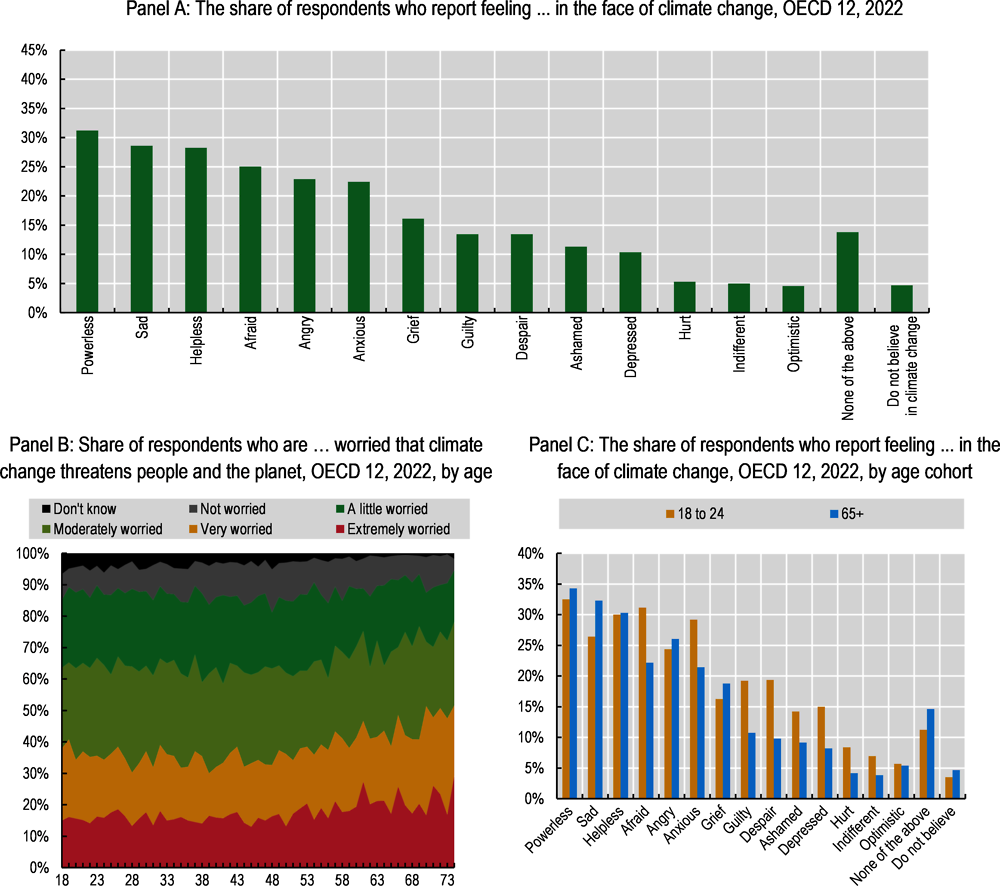

Results from a 2022 survey of 12 OECD countries show that 31% of respondents feel powerless in the face of climate change, and more than a fifth also feel sad, helpless, afraid, angry and anxious (Figure 3.9, Panel A). Some studies suggest that youth may be particularly susceptible to eco-anxiety, with more and more young people ranking climate change as the most important issue facing society (Ojala, 2018[170]; Bell et al., 2021[171]). A study published in The Lancet found that over 60% of young people from six OECD countries felt sad or afraid because of climate change (Hickman et al., 2021[172]).5 Data from the above mentioned online survey of 12 OECD countries show that older people are just as likely as younger people to feel very or extremely worried that climate change is a threat (Figure 3.9, Panel C). However, younger people aged 18 to 24 are more likely to be emotionally affected – reporting higher rates of feeling fear, anxiety, guilt, shame and depression than do those over the age of 65 (Figure 3.9, Panel D). As a recent report authored by young people from 15 countries worldwide states, they are particularly affected in that they will live with the implications of climate change for the rest of their lives: by definition, a longer time exposure to high stress events. They also feel more vulnerable given their lower incomes and lowered likelihood of being in positions of authority that enable them to enact desired solutions (Diffey et al., 2022[173]).

Not only do these negative emotions relay mood and affect-based changes, but they also interfere with peoples’ everyday lives. An international study from 25 countries found that negative feelings towards climate change were associated with insomnia and poor self-reported mental health (Ogunbode et al., 2021[174]). The Lancet study referenced above found that around 30% of respondents in six OECD countries reported that their climate-related feelings negatively affected their daily lives; while alarmingly high – almost one-third of youth – this number pales in comparison to the responses in lower-income, non-OECD countries such as the Philippines and India, where over 70% of young people reported being negatively impacted by feelings towards climate change on a daily basis. These countries are already facing a greater burden of extreme climate events – from droughts, heatwaves, flooding and hurricanes – and thus provide a grim prediction for the coming mental health impacts globally.

Figure 3.9. Over one-third third of people feel powerless in the face of climate change; older people are just as likely feel that it is a threat, but younger people are more emotionally affected

Note: OECD 12 refers to Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. Sample sizes were 2 000 respondents in each country, and data weighted post-hoc to be representative of the general population in terms of gender, age, region and occupation.

Source: OECD calculations based on AXA (2023[175]), Toward a New Understanding: How we strengthen mind health and wellbeing at home, at work and online, AXA Group, https://www.axa.com/en/about-us/mind-health-report.

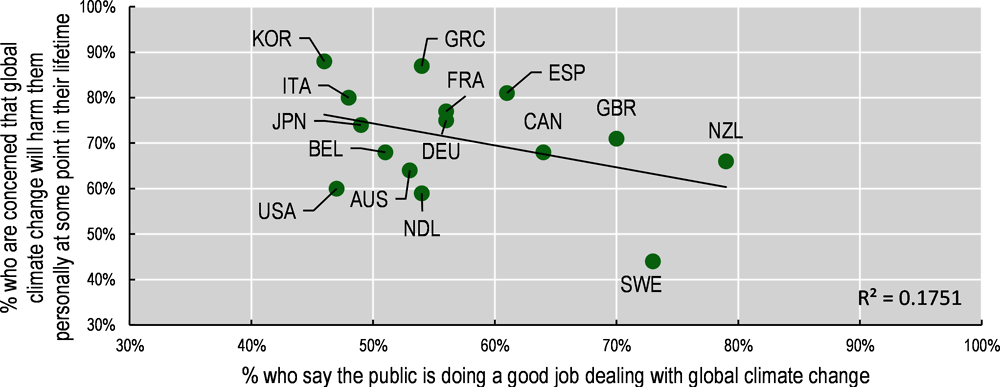

Oftentimes, feelings of eco-anxiety and distress may not be directly linked to the fact of climate change, but rather to perceived inaction in the face of it. Indeed, the sheer scale of the problem can be overwhelming and make the situation feel hopeless (“eco-paralysis”). The Lancet study found that mental distress was worse for young people when they felt government response was inadequate. These findings are echoed in data from the Pew Research Center, which surveyed respondents in 17 countries about perceptions surrounding climate change (Bell et al., 2021[171]). There is a slight negative correlation between the perception that the public is doing a good job dealing with climate change and concern that climate change will cause personal harm during one’s lifetime (Figure 3.10).

But in the same way that climate change is a risk multiplier, climate action can be an opportunity multiplier. On an individual level, focussing on positive developments to inspire hope, partaking in actions (even if small-scale) that can incrementally make an impact, and building personal and community resilience by engaging with community groups and supporting climate solutions can help alleviate feelings of eco-anxiety and related concepts of distress (Clayton et al., 2017[139]; Koger, Leslie and Hayes, 2012[168]).

Figure 3.10. In countries where people feel the public is doing a good job dealing with global climate change, a lower share of the population reports feeling concerned that climate change will harm them personally at some point in their life

Source: Bell et al. (2021[171]), In Response to Climate Change, Citizens in Advanced Economies Are Willing To Alter How They Live and Work, Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/09/14/in-response-to-climate-change-citizens-in-advanced-economies-are-willing-to-alter-how-they-live-and-work/.