An effective risk management system is dependent on the behaviours of several stakeholders and public servants’ commitment. To improve corruption risk management in the Slovak public sector, the OECD identified the behaviours that hinder an effective corruption risk management and analysed the barriers and enablers of these behaviours in a diagnostic analysis, following the application of the OECD BASIC framework. The key behaviour identified in a diagnostic analysis was that employees are not communicating about potential corruption risks as often as they should. Reasons for limited risk communication include a lack of support from leaders, a lack of feeling of safety when communicating about risks and a lack of awareness of how to communicate risks.

Improving Corruption Risk Management in the Slovak Republic

1. Behavioural analysis and proposals to strengthen corruption risk management in the Slovak Republic

Abstract

1.1. The role of risk management systems in enhancing public sector integrity

Identifying public integrity risks is imperative for preventing corruption in the public sector. Risk identification is one of the first conditions in making a problem observable and thus, manageable (Monteduro, 2021[1]; Power, 2007[2]). Risk management systems can be powerful tools to this end, as they help identify, assess and mitigate risks. The objective is not to get rid of risks entirely, but to reduce risks below an acceptable threshold. Effective internal control and risk management policies reduce the vulnerability of public organisations by guiding officials to adequately assess risks in their duties and develop strategies to manage them (OECD, 2020[3]). An organised, whole-of-government risk management system, which is connected to key government operations, is crucial to effectively address corruption risks and to avoid the implementation of ad-hoc measures addressing risks (OECD, 2022[4]).

Corruption risk management consists of a series of distinct steps to timely detect and manage corruption risks. This usually starts with the identification of risks, followed by an assessment, analysis and evaluation of the likelihood and impact of the identified risks. This is then followed by the design of a risk mitigation strategy, to address the most critical risks, and the design of control measures, to monitor the outcomes of these strategies. The final stage calls for a periodical reassessment of risks, and an update of the risk management processes, whenever new risks appear (Monteduro, 2021[1]; OECD, 2020[3]; OECD, forthcoming[5]).

The OECD and other international organisations emphasise the importance of risk management in corruption prevention (OECD, 2020[3]; GRECO, 2023[6]). The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity underlines the relevance of fostering integrity across the public sector and the whole of society, and establishing a context-dependent, behavioural, and risk-based approach (OECD, 2017[7]). This is in line with other international standards, such as the COSO 2017 ERM Framework (COSO, 2017[8]), the ISO 31000:2018 (International Organization for Standardisation, 2018[9]) or the ACFE 2016 Fraud Risk Management Framework (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, 2016[10]).

1.2. Risk management practices in the National Anti-Corruption Plan of the Slovak Republic for the years 2019-2023

In the past few years, the Slovak Republic has taken actions to curb corruption, as specified in the Anti-Corruption Policy for the years 2019-2023. The Policy, approved by Government Resolution No. 585/2018, recognises the importance of a risk- and evidence-based approach to integrity, and provides measures to strengthen the framework for mitigating corruption in the entire Slovak public administration (Government of the Slovak Republic, 2018[11]).

The Corruption Prevention Department (CPD) in the Government Office of the Slovak Republic leads risk management across the public administration, and the CPD oversees the development and implementation of corruption risk management practices in accordance with the Anti-Corruption Policy of the Slovak Republic for 2019-2023. Under the Policy, all ministries and other central authorities are required to appoint an Anti-corruption Coordinator (ACC) to oversee anti-corruption activities in their respective agency, including the implementation of the integrity measures set out in the Anti-Corruption Policy.

In 2019, the CPD also launched government-wide corruption risk assessment guidelines, to support the implementation of the integrity measures set out in the Anti-Corruption Policy. In line with these guidelines, all ministries and other central authorities are required to carry out an annual corruption risk assessment. In addition, the CPD also developed an electronic survey on corruption risk management, an optional and complementary tool to support ministries and other central authorities in identifying corruption risks. The electronic survey was distributed for the first time in 2020 and since then yearly. Results from the 2022 and 2023 electronic survey are partially published on a dedicated website.1

The CPD is relatively advanced in its risk management practices compared to other countries’ overseeing ministries and other central authorities. In a study carried out by the French Anti-corruption agency (l’Agence française anticorruption) (2020) slightly over half of the respondents from 113 countries reported that they have an obligation to carry out risk mapping in their public administrations (OECD, 2022[4]; L’Agence française anticorruption, 2020[12]). The CPD also started conducting its own risk analysis to assess broader level integrity risks across the Slovak public sector among others to inform the implementation of the Anti-Corruption Policy (OECD, 2022[4]). In the Integrity Review of the Slovak Republic, the OECD recommends the Slovak Republic to deepen its problem analysis to identify principal risk areas and to inform strategic policy objectives on anti-corruption across the public sector (OECD, 2022[4]). However, in its current version, the analysis of corruption risks in the Slovak public sector is focused on identifying thematic and sectoral priorities and could be further improved to consider a variety of sources of risks (OECD, 2022[4]).

To effectively measure corruption risks across sectors, a diverse portfolio of risk assessments is crucial. Apart from the information received through the electronic survey, the CPD also considers other sources when assessing risks, such as information received from ACCs, legislative gaps and shortcomings, complaints from citizens, recommendations from international organisations, consultation with NGOs and civil society, as well as media reports (OECD, 2022[4]).

In this regard, officials and civil servants are a key source to identify risks. To maintain and manage an up-to-date risk management system, it is vital to engage civil servants from across government agencies to consider risks arising from across the public administration. Managers and frontline employees may have different perceptions of the likelihood and impact of risks and frontline employees can in certain cases be in a better position than managers to identify emerging risks (OECD, 2022[4]; OECD, 2020[3]). For example, previous OECD experimental findings from the field of safety culture in the energy sector found that front line employees tend to have different perception of safety culture in the energy sector than regulators overseeing the sector, illustrating the importance of taking into account different perceptions when designing policies (OECD, 2020[13]). For an effective identification and assessment of risks, a well-functioning risk management system is dependent on the behaviours of several stakeholders and public servants’ commitment, and a timely engagement in risk management is key (OECD, forthcoming[14]).

To support the Slovak Republic in its efforts to strengthen its risk management practices in the public sector, this report explores how behavioural insights could serve to improve public sector integrity. This work was conducted in the context of the project “Improving integrity of Public Administration in the Slovak Republic” co-financed by the European Economic Area (EEA) and Norway Grants mechanism and the Government of the Slovak Republic and carried out by the OECD in partnership with the Corruption Prevention Department in the Government Office of the Slovak Republic.

To present the study and its findings, the structure of the report is as follows: This Chapter presents a diagnostic analysis of the current behavioural barriers for public integrity in the Slovak public administration, alongside a brief overview of the methodology followed to conduct the diagnostic analysis (OECD BASIC Toolkit). Chapter 2 presents the design and results of a behavioural experiment testing two potential interventions to improve the propensity to communicate potential corruption risks across Slovak public servants. Chapter 3 highlights key policy recommendations based on the experimental findings and directly connects current challenges to potential solutions – this constitutes the key section of reference for Slovak policymakers to review the implications of the study for future initiatives on public sector integrity.

1.3. The value of applying behavioural science to reduce corruption

A better understanding of the behavioural elements that affect corruption risk management can support the design, implementation and development of corruption risk management policies that foster trust and integrity. As such, the starting point for this study was investigating behavioural barriers and biases that affect integrity risk management in the Slovak public administration, to better understand what behaviours currently undermine effective corruption risk management.

Traditional policy instruments aim to strengthen controls and increase sanctions in efforts to curb corruption, however, they overlook two important behavioural dimensions: that integrity is an ethical choice, and that social norms and social dynamics also play a role in how individuals behave (OECD, 2018[15]). These and many other behavioural factors influence decision-making in the context of public integrity. The design of anti-corruption policies would therefore benefit from policies that are based on context-specific evidence on how people actually behave (OECD, 2018[15]).

The OECD publication Behavioural Insights for Public Sector integrity (2018) outlines how behavioural science can strengthen integrity and anti-corruption policies. In fact, recent years have witnessed an increasing interest in applying behavioural insights in anti-corruption policies (Stahl, C, 2022[16]). With the help of behavioural science, risk management systems can be designed in a way that ensures vigilance at stages where humans often tend to overlook or misjudge risks, to reduce errors and thus, to minimise risks (OECD, 2018[15]). To explore how behavioural science can support in improving the risk management practices in the Slovak Republic, the OECD applied a 5-stage framework (BASIC) developed by the OECD to apply behavioural science to public policy, presented in the following section.

1.3.1. Using OECD tools and ethics for applied behavioural insights: The BASIC Toolkit

The BASIC framework seeks to guide the application of Behavioural Insights to public policy through a framework of five stages (OECD, 2019[17]). The objective is to thoroughly understand a policy problem by getting at the core of the problem, to analyse it, to develop an optimal strategy for the desired behaviour change, to collect evidence on what works through robust experimental methodologies and to eventually improve policy outcomes by scaling up a successful strategy generating the desired behaviour change.

In the context of this study, the BASIC framework was used to guide the sequence of steps needed to conduct a behavioural study on public sector integrity, as follows (see Figure 1.1):

Behaviour: the aim of the first stage is to identify behaviours that should be targeted in order to address a policy problem.

Analysis: understand the drivers and barriers of the target behaviours through behavioural science.

Strategies: design or inform a policy solution with the support of behavioural science.

Intervention: based on a suitable experimental design, conduct a pilot initiative to measure the impact of the behavioural strategies.

Change: The last step involves considering how to use and scale up experimental findings for long-term change, while continuously monitoring and evaluating the impact of the intervention.

Figure 1.1. The 5 stages of the BASIC framework

Source: OECD (2019[18]), Tools and Ethics for Applied Behavioural Insights: The BASIC Toolkit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ea76a8f-en.

1.4. Diagnostic analysis: The behavioural challenges and opportunities in the public administration of the Slovak Republic

In line with the BASIC framework, the first step consisted of a diagnostic analysis to better understand the behaviours that affect corruption risk management in the public administration of the Slovak Republic, and the barriers and enablers of these behaviours. Applying behavioural science to public policy starts by asking which mechanisms drive behaviour in a specific context. Asking these questions in the context of public integrity helps to identify the behaviours that contribute to or impede progress toward public integrity, yet it also takes a step further to analyse and understand the mechanisms behind – the drivers and barriers of – these behaviours.

Evidence for the diagnostic analysis was collected through a focus group session with sixteen Anti-corruption Coordinators, who were divided into two groups, and from seven interviews with representatives from the upper management of various ministries and other central authorities , including, for example, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Investment, Regional Development and Informatization (MIRRI) as well as the Ministry of Finance, the Government Office, and the Public Procurement Office2. Both the focus group sessions and the interviews were held in September 2022. The rest of this chapter presents the key findings from the diagnostic analysis.

1.4.1. Identifying problem behaviours in the Slovak public administration

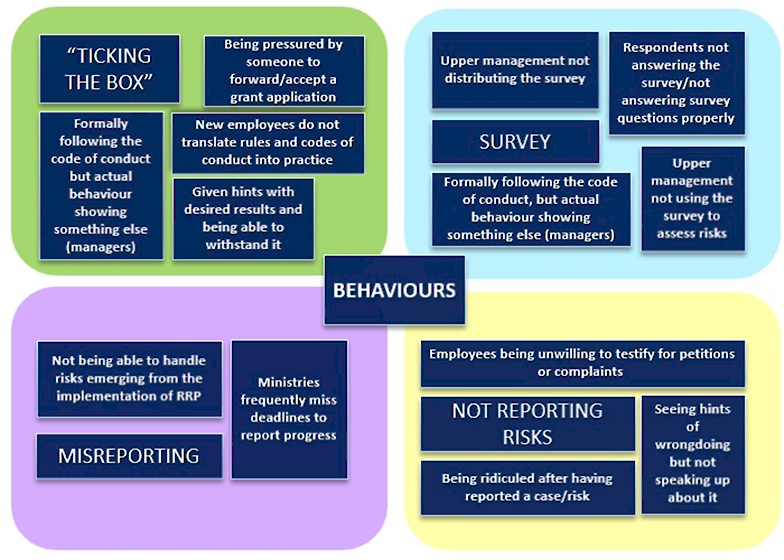

In conversations with participants, several problematic behaviours were identified as currently impacting integrity risk management in the Slovak administration. Four wider categories emerged from the diagnostic analysis: behaviours related to “ticking the box”, the electronic survey, misreporting, and not communicating about risks (see Figure 1.2).

For example, ministries sometimes misreported progress in implementing the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). Equally, some managers did not distribute the electronic survey or did not effectively use it to assess risks. Managers sometimes “ticked the box” to make it formally seem as if they follow the code of conduct, while in reality engaging in unethical behaviours. Lastly, public sector employees were not communicating enough about potential corruption risks.

To narrow down the behaviours to one target behaviour, misreporting was excluded as it only concerned some agencies. The electronic survey was excluded, as it was to undergo changes and development. Between “ticking the box” behaviour and the lack of risk communications, risk communication was a more tangible and measurable behaviour in an online experiment. Risk communication was thus selected as the main target behaviour, as both groups during the focus group sessions identified the lack of risk communication as one of the principal challenges.

Figure 1.2. The behaviours identified and grouped under 4 main categories

1.4.2. Barriers and enablers of key behaviours related to corruption risk management

The interviews evidenced that the maturity of risk assessment and management across the departments largely varies. Some individual departments have more advanced risk assessment procedures in place than others, and overall risk assessment and management capacities across Slovak ministries and other central authorities differ substantially.

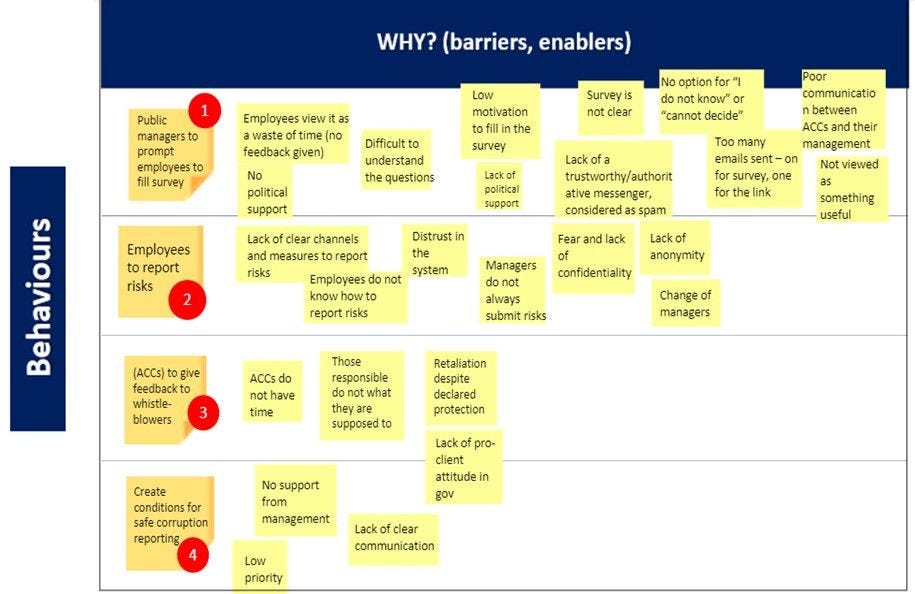

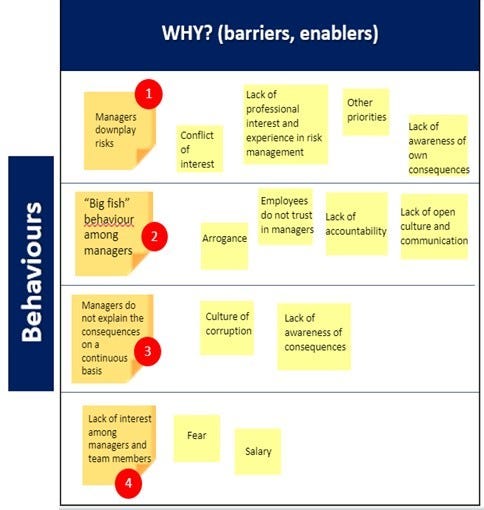

To identify behaviours related to corruption risk management, a key activity was the focus group sessions with sixteen Anti-corruption Coordinators, who were divided into two groups. Figure 1.3 and Figure 1.4 visualise findings from the respective groups. Key insights emerged under the themes of 1) limited support from leadership; 2) low feeling of safety; and 3) lack of ease and awareness of how to communicate risks:

Limited support from leaders

Public managers do not encourage or prompt employees to fill in the electronic survey which could be used to communicate integrity risks. The employees viewed filling the survey as a waste of time as no feedback is given on the survey results. The survey was simply not viewed as something useful, and the motivation to fill in the survey was low. The managers had experienced that there had been a lack of political support for the survey.

Some managers exhibit so-called “ticking the box”- behaviours meaning, that they claim to follow rules and codes of conduct, whereas in reality they fail to translate these rules into practice.

The Anti-corruption Coordinators do not give feedback to whistleblowers due to lack of time to provide feedback, lack of knowledge on how to follow up with a whistleblower case, and a fear of consequences in the form of retaliation, despite promised protection.

Employees also expressed that they do not communicate risks because the managers are not believed to act upon the risks communicated. There is a lack of feedback on the reported risks or cases.

Managers downplay risks. Potential conflicts of interest were said to result in managers downplaying risks , alongside a lack of professional interest or experience from knowing how corruption risks should be managed, and a lack of awareness of consequences of one’s own behaviour.

Managers engage in so called “big fish” behaviours, due to arrogance, lack of accountability in the system, a lack of open culture, and generally a culture of corruption, ultimately resulting in a lack of trust in managers.

Managers do not clearly explain the consequences of corruption risks on a continuous basis. This is linked to the general and pervasive culture of corruption and the lack of awareness of what the potential consequences from corruption risks are.

Lack of good examples from leadership had left the officials uncertain on how to act upon a risk in an atmosphere where they feel fearful for retaliation, or for being bullied or ridiculed for their concerns and being vulnerable.

Low feeling of safety in communicating risks

Public sector employees do not communicate risks even when being aware of them. Not communicating risks was said to begin within the leaders – despite signalling to follow the code of conduct formally (ticking the box, communicating to follow the code of conduct), still in reality, some leaders fail to do so. The misalignment between a leader’s words and actions had been noted to affect what the employees perceive acceptable.

Employees perceive that the conditions for speaking up about potential corruption risks are not sufficiently safe. Creating conditions for safely communicating about corruption risks was not seen as a high priority, and the respondents had experienced a lack of support from the management, as well as a lack of clear communication. Likewise, they reported a lack of anonymous and confidential channels to communicate risks, which in turn affected their ability to feel safe when communicating risks.

Avoidance of looking vulnerable to others reflects a work environment where people do not feel safe voicing their opinions. Respondents do not feel safe to show vulnerability in light of the fear of being bullied, ridiculed, ostracised or not taken seriously when speaking up about risks and voicing their opinions.

A culture of fear and silence, where people are discouraged from speaking out in fear of retaliation, was one of the reasons impeding risk reporting.

General mistrust in the corruption risk management system – i.e., a lack of trust in believing that the system works.

Lack of ease and awareness of how to communicate risks

A lack of understanding of the importance of reporting not only materialised corruption incidences, but also potential corruption risks. Across agencies the respondents had identified a tendency among officials to have difficulties distinguishing between a corruption risk, i.e., something that could happen, and a materialised corruption case, i.e., something that has actually happened. While public servants were aware of their need to report actual corruption cases, the necessity to report potential corruption risks was not as widely recognized.

Status quo bias was found to be prevalent, in the form of resistance towards change. Older people were less willing to speak about risks and preferred to maintain the current state of how things are instead of welcoming change.

A lack of understanding of which channels could/should be used to communicate corruption risks. Currently, a key factor behind why employees do not communicate integrity risks is the lack of clear and structured channels to do so. Employees can currently communicate risks personally by speaking with Anti-corruption Coordinators, ethics advisors, HR and managers, as well as anonymously via the electronic survey. However, the focus groups highlighted a limited awareness of these potential avenues for risk communication.

Figure 1.3. The key behaviours identified in group 1

Figure 1.4. The key behaviours identified in group 2

1.5. Connecting the results to previous research to better analyse behaviours

Three themes emerged from the behavioural barriers impeding public integrity and risk reporting in particular: limited support from leaders, low feeling of safety and lack of ease and awareness of how to communicate risks. Regarding leadership support, leaders were engaging in “ticking the box” to ensure superficial compliance. Several also raised the issue of “big fish” behaviour - an arrogance among managers where those with power dominate and shape the culture and downplay those who speak up, or even bully the whistle-blowers by labelling them as the “bad guys”.

The findings showed that people do not feel safe communicating about risks; on one hand, there is a culture dominated by fear and silence, not rewarding those who stand out or speak up about risks. Several viewed this as a generational issue: the older generation is more reserved and afraid to speak up about corruption risks. On the other hand, there is also a lack of safe channels to report integrity risks.

In addition to a lack safe channels and of knowledge on how to communicate risks, a lack of understanding of what a risk entails and the difficulty to understand the distinction between a risk, e.g., something that could happen, and an actual, materialised corruption case, e.g., something that did happen prevent people from identifying risks. The lack of understanding of a risk had emerged in conflicts of interest within the ministries (third line of defence), but also among the employees, line managers, and other risk owners (first line of defence).

1.5.1. Communicating corruption risks is dependent on the understanding of a corruption risk

Research shows that communicating a risk starts with the realisation that something constitutes a risk (Monteduro, 2021[1]). Risk perceptions have indeed been found to influence behaviours and intentions (Sheeran et al, 2014[19]) and a better understanding of risks can lead to improved decision-making and outcomes (Natter and Berry, 2005[20]). One of the findings in the diagnostic analysis was the lack of understanding of the importance of communicating risks in addition to materialised cases, and the lack of clear channels on how to communicate risks, which were both preventing effective risk communication.

The objective of this study therefore was to improve the understanding of the importance of communicating risks. Box 1.1 presents recommendations from an OECD project in Romania, which explored ways behavioural insights can strengthen the implementation of risk management across the Romanian public administration through the identification of logical behaviours needed for an effective risk management, and the design of strategies to support the identification of risks and other behaviours.

Box 1.1. Strategies to adopt integrity risk management in Romania

In 2018, Romania issued a comprehensive framework for all central government agencies requiring the agencies to implement anti-corruption strategies. Despite Romania’s best efforts to promote the adoption of the new anti-corruption strategy in the agencies, its implementation had been irregular, and it is unclear, whether it has succeeded in reducing corruption incidents. To understand the barriers that have led to the uneven adoption of the anti-corruption strategy, the OECD supported Romania in identifying the behavioural bottlenecks and strategies to tackle these. The most common issues included the inconsistent identification of corruption risks, potential miscalculations of risk probability and impact and poorly designed intervention measures.

From this analysis, four principal recommendations emerged:

1. Redesign of risk registers to include intermediate indicators for intervention measures to receive feedback on efforts to control corruption. Timely feedback from intermediate indicators could inform the decision-makers on current progress and whether efforts need redirecting.

2. Design of a government wide user guide for the adoption of a concise corruption risk methodology with examples and recommendations to increase learning. To harmonise and increase sharing of best practices among agencies, the guide should be consistent such that all examples have the same definitions. Case studies from more advanced agencies could be included to exemplify how the methodology can be used in practice.

3. Develop a web-based app to guide corruption risk management to improve risk identification, probability estimation, impact estimation and control measure design ensuring that officials are equipped with a fair understanding of how public institutions work and information of the effectiveness of intervention measures in reducing corruption risks.

4. Establish a unit within each ministry to assist working groups in managing corruption risks to provide guidance and support in risk identification, probability and impact assessments and intervention measure design. Specialised units could play an important role in identifying potential risk areas and provide feedback and support on the risk assessment.

Source: OECD (2023[21]), Promoting Corruption Risk Management Methodology in Romania: Applying Behavioural Insights to Public Integrity, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ceb6faec-en.

1.5.2. Leaders have a central role in encouraging employees to behave ethically

One of the key findings of the diagnostic analysis was the key role that leaders play in enabling or blocking risk communication behaviours. This is in line with previous work on the importance of leadership for promoting ethical behaviours. Indeed, the OECD previously recommended strengthening integrity standards in public employment and promoting integrity leadership (OECD, 2022[4]). Senior civil servants at all levels set the standards for public service and organisational values by their own behaviours. Exemplary leaders live up to the written code of conduct and apply it to the daily work, which builds trust in their team.

A meta-review by Bedi et al. (2016) found that ethical leadership was positively associated with, among other things, followers’ job satisfaction, job performance and job engagement, and followers increasingly perceived that their work context was ethical when they had an ethical leader (Bedi et al., 2016[22]). Previous research has also reported that followers’ perceptions of ethical leadership predict willingness to report issues (Brown and Treviño, 2006[23]; Brown et al, 2005[24]; Hassan et al, 2014[25]). Brown et al. (2005[24]) predicted that by engaging in ethical behaviours, leaders become attractive and credible, and followers tend to adopt their ethical behaviours. Box 1.2 presents best practices from strengthening integrity leadership in Brazil.

Box 1.2. Strengthening integrity leadership in Brazil’s federal entities

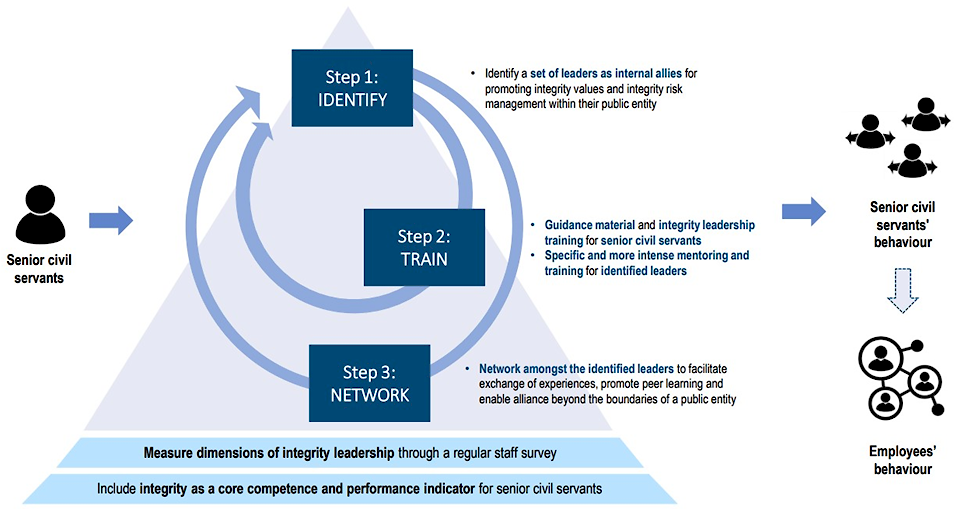

Recent reforms in Brazil have focussed on strengthening senior civil service leadership in Brazil. Despite these significant efforts, there still is scope for improving integrity leadership. Currently, integrity is not part of leadership trainings in Brazil, yet evidence suggests that additional efforts are needed to provide leaders with the right skills and abilities to uphold the public administration’s ethical standards. Leaders do not currently sufficiently raise awareness about integrity within their organisations. In a recent dedicated project, the OECD suggested the following three stage-model to strengthen integrity leadership in Brazilian civil service, as reflected in Figure 1.5:

Step 1 starts with identifying potential integrity leaders within an organisation. By being identified as a leader, civil servants feel committed to the values of the organisation.

Step 2 equips the integrity leaders through training with the right skills and competences to better promote integrity and open culture in their respective organisations.

Step 3 focuses on establishing a network for the integrity leaders across the public sector. A network could facilitate peer learning, and regular meetings could help to maintain engagement over time.

Figure 1.5. A roadmap for strengthening senior integrity leadership in Brazil

Source: OECD (2023[26]), Strengthening Integrity Leadership in Brazil’s Federal Public Administration: Applying Behavioural Insights for Public Integrity, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/50a9a028-en.

Both Brown et al. (2005[24]) and Walumbwa and Schaubroeck (2009[27]) concluded that ethical leadership indeed is associated with willingness to report problems to management. Ethical leadership can create a safe organisational climate in which employees feel comfortable discussing ethical issues and communicating ethical problems without fear of retaliation. When people are afraid to voice concerns about ethical problems in their organisation, ethical leadership can reduce this fear (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck, 2009[27]).

1.5.3. Psychological safety as a driver of ethical behaviors

Psychological safety influences behaviours and decisions in organisations. Leaders are largely responsible for creating and supporting behaviours and environments where followers feel safe at blowing the whistle (Caillier, 2015[28]). When employees have a leader who is honest, trustworthy, and fair, their team members are more likely to think that their leader will agree with or understand their concerns and respond to them appropriately (Caillier and Sa, 2017[29]), and will feel more comfortable discussing sensitive ethical issues and raise concerns (OECD, 2020[13]).

Walumbwa and Schaubroeck (2009[27]) found that ethical leadership influence risk communication behaviours through the mediating effect of psychological safety. By creating a safe and fair workplace environment, followers were encouraged to voice their opinions about ethical matters, but also about other, work-related concerns (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck, 2009[27]). These findings also resonate with an OECD cross-national case study, which explored the role of safety in the energy sector and how perceptions of safety can vary among different actors (Box 1.3).

Box 1.3. A cross-national experiment to foster culture of safety in Canada, Ireland, Mexico and Oman

The OECD, academics and behavioural practitioners collaborated to apply behavioural insights to safety culture in the energy sector, in a two-stage online experiment in Canada, Ireland, Mexico and Oman. The first experiment tested the perceptions of safety and effectiveness of behavioural vignettes. A follow-up survey experiment was also conducted in Ireland to improve conformity with safety regulations among gas and electricity installers.

From the comparative experimental results, a key result on the perception of safety culture that the closer one is to the front line, the lower one’s perception of safety culture. From a system perspective, the study showed that regulators have a more negative perception of safety culture in the regulated entities than the entities themselves, perhaps due to their position overseeing the sector. This result makes sense as frontline workers are directly experiencing unsafe activities, and regulators analyse the sector for potential risks. This result underlines the need to understand the audience and how the perceive the challenges at hand, which can further influence their understanding and actions.

Source: OECD (2020[13]), Behavioural Insights and Organisations: Fostering Safety Culture, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6ef217d-en.

Taking into account insights from previous research and the diagnostic analysis, revealing mistrust in the corruption management system, a culture of fear and silence and a lack of safe communication channels – all of which hinder effective risk communication - this study also delved into how feeling psychologically safe can boost the chances of communicating risks.

References

[10] Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (2016), Fraud Risk Management Guide, Second edition.

[22] Bedi et al. (2016), “A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators”, Journal of Business Ethics 139 (2016): 517-536..

[23] Brown and Treviño (2006), “Ethical leadership: A review and future directions”, The leadership quarterly 17.6 (2006): 595-616..

[24] Brown et al (2005), “Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing”, Organizational behavior and human decision processes 97.2 (2005): 117-134.

[28] Caillier (2015), “Transformational leadership and whistle-blowing attitudes: Is this relationship mediated by organizational commitment and public service motivation?”, The American Review of Public Administration 45.4 (2015): 458-475.

[29] Caillier and Sa (2017), “Do transformational-oriented leadership and transactional-oriented leadership have an impact on whistle-blowing attitudes? A longitudinal examination conducted in US federal agencies”, Public Management Review 19.4 (2017): 406-422.

[8] COSO (2017), “Internal Control - Integrated Framework”, https://www.coso.org/Pages/ic.aspx (accessed on 11 September 2017).

[11] Government of the Slovak Republic (2018), Anti-Corruption Policy of the Slovak Republic for the years 2019-2023, https://www.bojprotikorupcii.gov.sk/data/files/7130_protikorupcna-politika-sr-2019-2023.pdf?csrt=1785855676555738388 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

[6] GRECO (2023), Group of States Against Corruption, Council of Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/greco.

[25] Hassan et al (2014), “Does ethical leadership matter in government? Effects on organizational commitment, absenteeism, and willingness to report ethical problems”, Public Administration Review 74.3 (2014): 333-343..

[9] International Organization for Standardisation (2018), Risk managemen - guidelines (ISO Standard No. 31000:2018)..

[12] L’Agence française anticorruption (2020), Global Mapping of Anti-Corruption Authorities, https://www.agence-francaise-anticorruption.gouv.fr/files/2020-06/NCPA_Analysis_Report_Global_Mapping_ACAs.pdf.

[1] Monteduro, C. (2021), “Does stakeholder engagement affect corruption risk management?”, Journal of Management and Governance, 25(3), pp. 759–785, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09527-9.

[20] Natter and Berry (2005), “Effects of active information processing on the understanding of risk information”, Applied Cognitive Psychology 19.1 (2005): 123-135..

[21] OECD (2023), Promoting Corruption Risk Management Methodology in Romania: Applying Behavioural Insights to Public Integrity, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ceb6faec-en.

[26] OECD (2023), Strengthening Integrity Leadership in Brazil’s Federal Public Administration: Applying Behavioural Insights for Public Integrity, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/50a9a028-en.

[4] OECD (2022), OECD Integrity Review of the Slovak Republic: Delivering Effective Public Integrity Policies, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/45bd4657-en.

[13] OECD (2020), Behavioural Insights and Organisations: Fostering Safety Culture, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6ef217d-en.

[3] OECD (2020), OECD Public Integrity Handbook, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac8ed8e8-en.

[18] OECD (2019), Tools and Ethics for Applied Behavioural Insights: The BASIC Toolkit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ea76a8f-en.

[17] OECD (2019), Tools and Ethics for Applied Behavioural Insights: The BASIC Toolkit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ea76a8f-en.

[15] OECD (2018), Behavioural Insights for Public Integrity: Harnessing the Human Factor to Counter Corruption, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264297067-en.

[7] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf.

[14] OECD (forthcoming), Promoting capacities, opportunities and motivations to adopt the corruption risk management methodology in Romania.

[5] OECD (forthcoming), Promoting the adoption of the corruption risk management methodology in Romania: Applying Behavioural Insights to Public Integrity.

[2] Power (2007), Organized Uncertainty: Designing a World of Risk Management (pp. xviii–xviii), Oxford University Press, Incorporated., https://doi.org/10.1604/9780191531149.

[19] Sheeran et al (2014), “Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies”, Psychological bulletin 140.2 (2014): 511.

[16] Stahl, C (2022), Behavioural insights and anti-corruption. Executive summary of a practitioner-tailored review of the latest evidence (2016-2022).

[27] Walumbwa and Schaubroeck (2009), “Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety”, Journal of applied psychology 94.5 (2009): 1275..

Notes

← 2. Ministries and other central authorities involved in the study: Ministry of Economy, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Transport, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family, Ministry of the Environment Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sports, Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Investments, Regional Development and Informatization, Government Office, Antimonopoly Office, Statistical Office, Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre Authority, Nuclear Regulatory Authority, The Slovak Office of Standards, Metrology and Testing, Public Procurement Office, Industrial Property Office, Administration of State Material Reserves, National Security Office, Office for Spatial Planning and Construction, Supreme Audit Office, Judicial Council, Association of Towns and Communities.