Two behaviourally informed strategies were designed to increase risk communication. The effects of these two strategies were tested in an online randomised controlled trial (RCT). In addition, the relationships between the likelihood of communicating a risk and several secondary outcome variables, such as psychological safety, knowledge on the reporting channels and trust, were also explored. The results indicate that exposing employees to examples of exemplary leadership and social norms can increase the likelihood of communicating a corruption risk. Feeling generally safe when communicating about risks, having hiring responsibility, and having trust and knowledge of reporting channels also play an important role in improving risk communication.

Improving Corruption Risk Management in the Slovak Republic

2. Experimenting and assessing the impact of two behavioural strategies in the Slovak Republic

Abstract

2.1. The experimental design

A key finding from the diagnostic analysis is that the lack of exemplary managers, leading by example on how to behave ethically was a frequent barrier to improvement risk communication across the Slovak public sector. Another key barrier raised in various contexts was the lack of understanding the difference between a corruption risk and a corruption incident.

As such, the study aimed at identifying strategies that could address these two barriers of 1) the lack of understanding of what a risk is, and 2) lack of good leadership, thus ultimately contributing to improving risk communications.

It was chosen to test different strategies through a vignette experiment, a research method often used in social and behavioural sciences to study human behaviour, attitudes, or decision-making processes. In a vignette experiment, participants are presented with hypothetical scenarios or brief descriptions ("vignettes") that depict a particular situation or event. Different groups of participants receive slightly different scenarios, and the goal is to understand how individuals respond or make decisions based on these scenarios. Researchers use vignettes to control and isolate certain factors while observing how changes in these factors influence participants' attitudes, perceptions, or behaviours. This controlled approach helps in studying causality and understanding the impact of different variables on human responses.

In the case of the experiment on risk communication in the Slovak public administration, the research exposed participants to a hypothesised scenario (i.e., a vignette) where they would imagine being confronted with a potential integrity risk in their public administration. Specifically, participants were shown the vignette in the form of a short text describing a hypothetical situation of a recruitment process involving a potential corruption risk in hiring processes (Figure 2.1). The goal was to simulate a situation in which risk communication would be preferable and to assess whether behavioural strategies would encourage risk communication.

Figure 2.1. The vignette

The experiment was conducted by the OECD and the Corruption Prevention Department of the Government Office of the Slovak Republic in the form of a randomised trial, meaning that, after seeing the vignette, different participants were randomly selected to be exposed to slightly different versions of the experiment. This enables analysing how different factors affect participants’ decision-making processes.

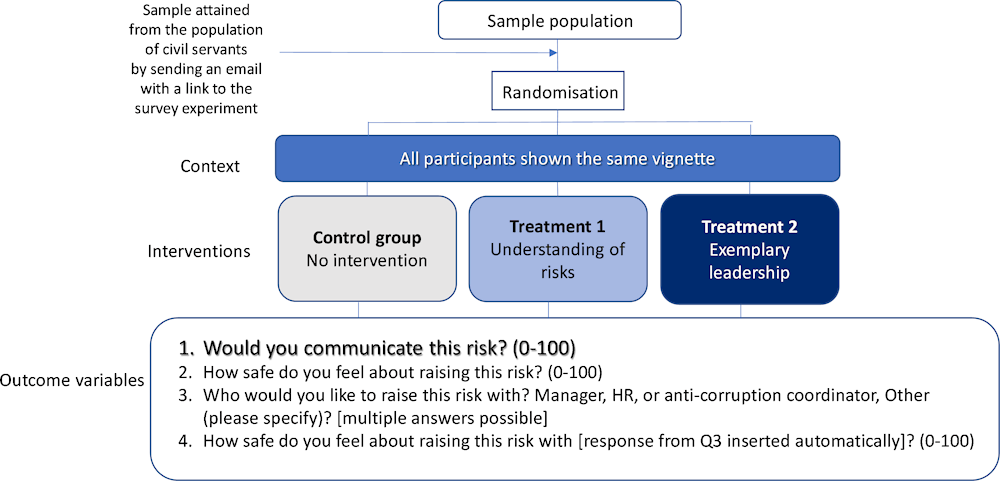

Specifically, the study tested whether groups of participants that would be exposed to a scenario including behaviourally informed interventions would have higher propensity to risk communication, as compared to a situation where participants were not exposed to any behavioural strategy (see Study Design in Figure 2.2). As such, each participant in the experiment was randomly assigned to one of the three study groups: treatment 1, the “Understanding of a risk”-condition (where participants were exposed to text supporting them in understanding the importance of communicating corruption risks), treatment 2, the “Exemplary leadership”-condition (where participants were exposed to examples of good ethical behaviours of leaders), or the control group which was not subject to any behavioural treatment.

Finally, after the vignette and the randomisation, participants would be asked whether they would speak up about the potential risk, to whom they would communicate it to, along with a series of additional questions to understand, e.g., their feelings of safety/ trust in the communication channels.

Figure 2.2. The trial design

The process of designing a vignette for the experiment and selecting an appropriate topic focused on identifying a public integrity risk that would be relatable for most people across the public administration. Since hiring new officials is an activity that all the agencies and ministries across the public administration must engage in, the vignette was selected to represent a hiring situation with a potential corruption risk. It was hypothesised that the topic of preventing corruption in recruitment processes would be an easily understandable one, and one that employees normally consider important.

Indeed, a merit-based recruitment system is widely recognised as important for a well-functioning public administration. Hiring employees with the right skills can improve performance and productivity and translate into better policies and services (OECD, 2022[1]). On the contrary, nepotism and favouritism are key concerns in the context of HR and recruitment (OECD, 2022[1]). The Anti-Corruption Policy for the years 2019-2023 of the Slovak Republic also acknowledges this and includes an objective to “permanently create conditions to prevent abuse of power, influence and position, clientelism, favouritism and nepotism” and to reduce corruption risks through a fair evaluation of the skills of the staff against their allocated responsibilities and performance (Government of the Slovak Republic, 2018[2]). Hence, communicating risks related to hiring practices was considered a suitable domain for the vignette.

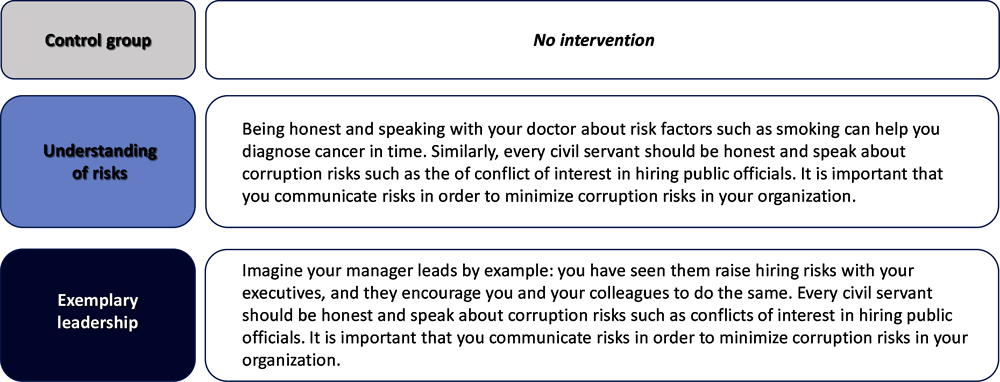

On the same screen, together with the vignette, participants in the two treatment groups were shown the interventions: a message aiming at improving the understanding of a risk by drawing on an analogy from the context of health in treatment 1, and a text appealing to exemplary leadership in treatment 2 (Figure 2.3). The two treatment messages were designed orthogonally, i.e., such that they are identical, except for the messages appealing to either understanding of a risk or exemplary leadership, to ensure comparability. To ensure that the two messages were comparable, two identical sentences were embedded in both interventions and drew on social norms, which have been found in previous studies impactful in changing ethical behaviours (Bicchieri, C., & Xiao, E., 2009[3]; Banerjee, R., 2016[4]). In contrast, participants in the control condition did not receive exposure to any messaging, they just saw the vignette.

Figure 2.3. The interventions

The diverging sentences appealing to understanding of a risk and exemplary leadership are the ones hypothesised to create the difference between the two treatments. The hypotheses of the direction of the effect of the interventions were the following:

1.1. If the understanding of a risk affects the likelihood of communicating corruption risks, the likelihood of communicating a risk will be higher when a public official is prompted with a message aiming at increasing the understanding of a risk, compared to a situation, where he or she is not prompted with such a message.

1.2. If having an exemplary leader affects the likelihood of communicating risks, then the likelihood of communicating a risk will be higher when a public official is prompted with a message depicting having an exemplary leader, compared to a situation, where he or she is not prompted with such a message.

Primary and Secondary Outcome variables: After having seen the vignette – or, the vignette and a behavioural message - each participant was asked a series of questions to obtain a measure of the primary outcome variable, i.e. the likelihood of communicating a risk, measured on an interval from 0 to 100 (see Annex C). Additional questions asked (i.e. secondary outcome variables) included general feelings of safety in risk communication (measured on an interval from 0 to 100), to whom one prefers to communicate a risk (Anticorruption coordinator, Manager, Other), whether the respondents correctly understand that the situation in the vignette constitutes a corruption risk (Corruption risk, Corruption incident, I do not know, I would not communicate this), the appropriateness of the corruption risk management in one’s own organisation (measured on a scale from 0 to 100), fairness of the hiring process (measured on a scale from 0 to 100), whether a respondent is responsible for the hiring process (yes, no, prefer not to say) and knowledge of the reporting channels (Yes, rather yes, not before, no) (see Annex A for the complete survey flow and detailed questions on how data was collected). The answer alternatives for the question measuring knowledge on the reporting channels were identical to the question measuring knowledge on the reporting channel in the Corruption Prevention Department’s electronic survey.

These questions were followed by questions on age, gender, career length in the public administration and the agency in which the respondent is employed. Questions about demographics were asked last, to avoid any priming effects, i.e., to avoid that referring to participants’ individual characteristics would subconsciously affect their responses. Box 2.1 expands on how these variables were measures and coded to discern the experiment’s findings.

Box 2.1. Chosen methodologies for measuring the effects of the experiment

To measure the understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks, the respondents were asked to identify whether the situation in the vignette constitutes 1) a corruption risk, 2) a corruption incident, 3) I would not communicate on this and 4) I do not know. Since the relevance of this question for the analysis lies in whether the respondents correctly viewed the situation in the vignette as a risk or not, for the sake of this analysis, this variable was included as a binary variable, taking value 1 if the respondent identified that this situation constitutes a corruption risk (i.e., if a respondent had chosen the answer alternative corruption risk – also the alternative corruption risk and I would not communicate on this was accepted as correct) and 0, if otherwise.

The variable measuring knowledge on the reporting channels was coded as follows. A binary dummy variable taking value 1 if a respondent has knowledge on the reporting channels (Yes/Rather yes), and 0 otherwise. Another variable took the value 1 if a respondent indicated not having knowledge on the reporting channels (No), and 0 otherwise.

The following variables were included in all the regressions as binary/categorical dummy variables: Understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks (binary ), responsible for hiring (binary, taking value 1 if being responsible for hiring, 0 otherwise), having knowledge on the reporting channels (binary, taking value 1 if respondent indicated Yes/Rather yes to having knowledge on reporting channels, 0 otherwise), not having knowledge on the reporting channels (binary, taking value 1 if respondent indicated No to having knowledge on reporting channels, 0 otherwise), male (binary, taking value 1 if identified as a male, 0 otherwise), female (taking value 1 if respondent indicated being a female and 0 otherwise), whom one prefers communicating a risk to (HR, reference category for whom to communicate a risk to).

2.1.1. Survey dissemination and incentives to encourage participation

The survey was conducted in Slovak language, and it was fully anonymous. To recruit participants, the Government Office of the Slovak Republic and the OECD agreed to incentivise the respondents with a lottery in which three public sector employees would be randomly selected to have a conversation with the Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic, upon the condition of having responded to the survey (“regret lottery”). If a selected candidate did not meet the required condition, a lottery ticket was redrawn until a candidate who met the criteria was selected.

The survey was developed and implemented using Qualtrics, a computer-based survey platform designed for survey creation. The link to the survey was embedded in an email which was disseminated by the Government Office of the Slovak Republic via the ACC of each ministry other central government body to all the public sector employees. In addition, the ACCs sent out two follow-up reminder emails encouraging staff to complete the survey (Annex B). The survey was launched on the 15th of June 2023, and it was kept open for approximately two weeks; it was closed on the 30th of June 2023.

2.2. Descriptive statistics to provide insights on the sample

Participant selection criteria: The participants had to be civil servants, working in the public administration of the Slovak Republic. While there are no general age limits applicable across the Slovak public administration, observations were selected based on the Slovak Civil Service Act, which defines a maximum career length of 50 years to account for a career that started at the age of 18 and ended at the age of 68. Hence,14 observations indicating a career length longer than 50 years were excluded. No information, other than the age limits, were available on typical career lengths in the public administration of the Slovak Republic.

Sample size: In total, 4760 responses were registered; however, 2179 of them were incomplete responses, and thus had to be excluded from the analysis. From the remaining 2581 responses, an additional 24 observations indicated being younger than 18 or older than 68, and hence based on the acts mentioned above, they were excluded from the analysis. In total, respondents from 22 agencies took part in the survey. These agencies included executive and legislative organs, such as ministries and judicial offices, and various agencies organising general public services. The final, total number of observations included in the regressions is 2537.1 Annex O presents the sample sizes across the study groups, and the whole sample.

Statistical power analysis: The sample size is in line with power calculations. A “power analysis” was conducted to determine the sample size required to detect an effect with the required degree of confidence. Indeed, an experiment needs to have a certain amount of statistical power (the standard being 80%), to be able to say with 80% certainty that, when an effect is detected, that effect is true. Several aspects, such as sample size and the size of the expected detectable effect size affect the statistical power of a study. Based on past research, similar studies have found effect sizes of 2.9 percentage points (pp) and higher. The goal therefore was to obtain 80% power to detect a minimum effect size of 4 pp (based on an average of similar past research (van Roekel, 2021[5]; Bhal, K. T., and Dadhich, A., 2011[6]). For an effect size of 4 pp, a sample size of 3000 was needed, which would result in power of over 80%.

Randomisation checks: The size of the different treatment and control groups was similar, indicating that the randomisation was successful. Indeed, there were 838 observations in Treatment 1, 836 in Treatment 2, 863 in the control group.

Gender distribution: The share of women in the sample represented 45.13% of the sample, and the share of men 37.49%, while 1.18% of the sample indicated to identify themselves as non-binary, and 16.20% preferred not to disclose their gender. Because the sample size for those who identified themselves as non-binary was low, most of the time, they had to be omitted from the analysis. Looking at the wider population of public officials in the Slovak Republic, the female gender represented 60.39% of employees in public sector employment in the Slovak Republic in 2017 (OECD, 2019[7]). The share of women in the experimental sample is lower, yet, similarly to the 2017 statistics, the share of women is still larger than the share of men.

Age and career-length distribution: The youngest respondent in the sample is 20 years, and the oldest is 68, with a mean age of 44 years old. Career length varied between 0 and 68 years, with a mean career length of 15 years.

2.3. Experimental results

A few key lessons emerged from the experiment, which can be broadly summarised into 5 main takeaways:

1. The two behavioural interventions significantly improved the likelihood of communicating a risk.

2. The two treatments also slightly improved general feelings of safety among the respondents.

3. Respondents felt safest when communicating risks to specific stakeholders.

4. Understanding the importance of communicating a risk was low in the whole sample.

5. Trust in the risk management system is dependent on knowledge of the reporting channels.

The sections that follow explain these findings more in-depth and substantiate them with the statistical findings from the experiment.

2.3.1. The two behavioural interventions significantly improved the likelihood of communicating a risk

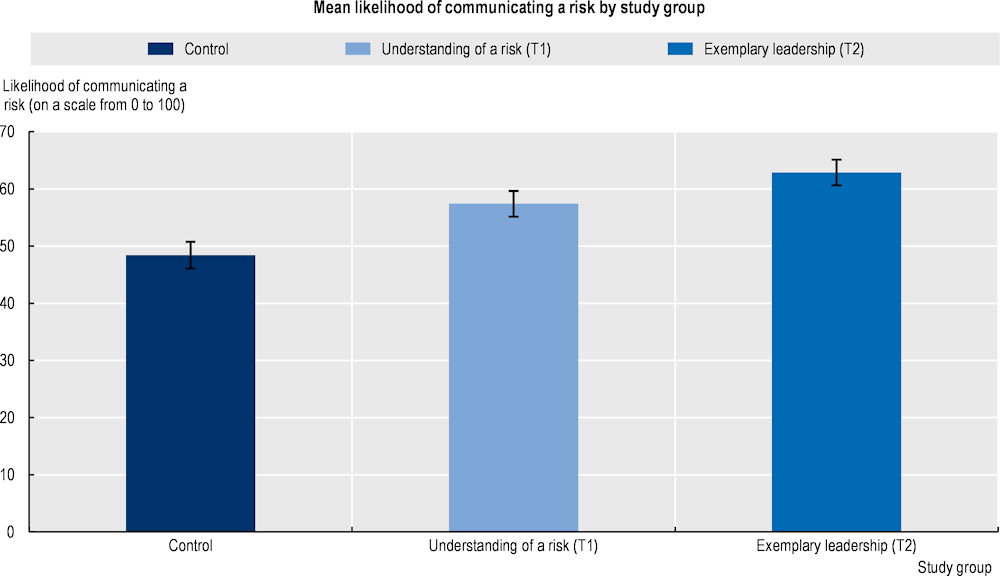

In the control group, 48% of respondents indicated that, in the given scenario, they would communicate the potential risk. This means that the baseline for communicating risks in normal conditions is very low; in absence of the interventions, only less than half of the respondents would communicate risks. In turn, respondents who saw the message aimed at clarifying what a risk is (treatment 1), were more the likely to communicate a risk (around 57%), and those who were exposed to the message on leadership (treatment 2) were even more likely to do so (around 62%). The intervention appealing to exemplary leadership was the most impactful in increasing the likelihood of communicating a risk, but the intervention increasing understanding of a risk also significantly improved the likelihood of communicating a risk compared to the control.

The main results from means tests are illustrated in Figure 2.4. The graph visualises the mean of the likelihood of communicating a corruption risk in the three study groups (treatment 1 (T1), treatment 2 (T2) and control group), with error bars visualising 95% confidence intervals. As mentioned, the likelihood of communicating a risk is the lowest in the control group (at around 48%), the likelihood of communicating a risk is significantly higher for treatment 1 compared to the control group (at around 57%), and the likelihood of communicating a risk is the highest in treatment 2 (at around 62%). These significant results were confirmed through robustness checks in Box 2.2.

Figure 2.4. The two behavioural interventions had a significant effect on the likelihood of communicating a risk, compared to the control group

Bar graph of the mean of likelihood of communicating a risk with error bars, by study group

Note: The error bars display the 95% confidence intervals. The error bars show the spread around the mean. The error bars are relatively short, entailing that there is relatively little variation. The error bars do not overlap vertically, which signals a statistically significant difference between the means across the control and the treatment groups (for statistical means testing, see Table 2.2).

Box 2.2. Robustness checks confirm the significant effect of the two messages on the likelihood of communicating a risk

Two non-parametric means tests were conducted to test the robustness of the experimental results. Since the observations of the primary outcome variable were not normally distributed (see Annex C), two non-parametric tests; a Mann-Whitney U-test and a Kruskal Wallis test, which do not impose any strict assumptions on the shape of the distribution, were conducted. Table 2.1 summarises the number of observations, means, standard errors, standard deviations, the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence intervals for the two treatment groups and the control group, and the differences in means between the study groups.

Table 2.1. Number of observations, means, standard errors, and lower and upper bounds of a 95% confidence interval for the likelihood of communicating a risk, by treatment

|

Group (N) |

Mean |

Standard error |

Lower limit |

Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Treatment 1 (N = 838) |

57.40089 |

1.1591 |

55.12581 |

59.67598 |

|

Treatment 2 (N = 836) |

62.86821 |

1.141664 |

60.62734 |

65.10907 |

|

Control (N = 863) |

48.41282 |

1.189361 |

46.07843 |

50.7472 |

|

T1-C |

-8.988079 |

1.661739 |

12.24735 |

5.728809 |

|

T2-C |

-14.45539 |

1.650117 |

17.69187 |

11.21891 |

|

T2-T1 |

5.467311 |

1.626964 |

2.276209 |

8.658413 |

Table 2.2 presents the results from the means tests. Both the difference in means between the treatment 1 and the control group is (-8.99 pp), and the difference between the treatment 2 and the control group (-14.46pp) were statistically significant - confirming, that both treatments do significantly influence the likelihood of communicating a risk. In addition, the statistical difference of the means between the two treatment groups (-5.47pp) was also found significant, indicating treatment 2’s significantly higher impact on the likelihood of communicating a risk, compared to treatment 1.

Table 2.2. Results from the means tests

|

Test |

Mean |

Mann-Whitney |

Kruskal-Wallis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rank sum |

Z |

p-value |

Χ2 |

p-value |

||

|

T1-C |

-8.988079 |

765490.5 |

-5.182 |

0.000 |

26.852 |

0.0001 |

|

682060.5 |

||||||

|

T2-C |

-14.45539 |

794636.5 |

-8.332 |

0.000 |

69.429 |

0.0001 |

|

649513.5 |

||||||

|

T2-T1 |

5.467311 |

733072.0 |

3.340 |

0.000 |

11.159 |

0.0008 |

|

668903.0 |

||||||

The results from the OLS regression show that both treatments have a highly statistically significant effect on the likelihood of communicating a risk, as was confirmed by the means tests and from visual illustration of the results (for the graph see Figure 2.4, for means tests see Table 2.2). Table 2.3 presents the results from an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS)-regression with robust standard errors, with the likelihood of communicating a corruption risk as the dependent variable. An OLS regression with robust standard errors investigates whether a linear relationship exists between the two treatments, and the likelihood of communicating a risk. A table summarising results from all the robustness checks can be found in Annex E.

The likelihood of communicating a risk was measured on a scale from 0 to 100. All the effects are relative to the baseline of 31.50 (the intercept, the estimate for the control group). All the results are calculated based on the assumption that all the other variables are held constant.

Table 2.3. The two treatments have a highly statistically significant effect on the likelihood of communicating a risk

The table summarises the results from the main regression: OLS with robust standard errors. Dependent variable: likelihood of communicating a risk

|

OLS with robust standard errors |

|

|---|---|

|

Understanding of a risk (T1) |

8.209*** (1.493) |

|

Exemplary leadership (T2) |

11.98*** (1.494) |

|

General feeling of safety |

0.293*** (0.0247) |

|

Agency |

-0.185 (0.119) |

|

Responsible for hiring |

3.897* (1.941) |

|

Understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks |

14.06*** (1.247) |

|

Appropriateness of risk management |

0.130*** (0.0324) |

|

Perceived fairness of the hiring process |

0.0280 (0.0301) |

|

Knowledge of reporting channels |

|

|

Yes |

2.452 (1.424) |

|

No |

-4.307* (2.081) |

|

Age |

-0.252*** (0.0741) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

1.170 (1.778) |

|

Male |

3.214 (1.844) |

|

Career length in the public administration |

0.0867 (0.0745) |

|

Intercept |

31.50***(3.917) |

|

N |

2537 |

|

R2 |

0.248 |

|

adj. R2 |

0.244 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The respondents in the Exemplary leadership-treatment were 12.00 percentage points (pp) more likely to communicate a risk compared to the respondents in the control group. The respondents in the Understanding of a risk-treatment were 8.21 pp more likely to communicate a risk, compared to control group. The effect sizes for the treatments slightly differ from those reported above (see Box 2.2) as the estimation methods differ (statistical tests estimate whether the average effects are equal between the study groups, whereas regression analysis looks at partial effects, keeping all the other variables included in a regression equation constant). The direction of these results is confirmed by the robustness checks (see Annex E) where the effect of both treatments is statistically significant on 0.1%-level.

General feelings of safety when communicating about risks (How safe do you feel about raising this risk?) was also measured on a scale from 0 to 100. General feelings of safety significantly correlate with the likelihood of communicating a risk across all the regressions (Annex E). According to the results, a unit increase in general feelings of safety is estimated to increase the likelihood of communicating a risk by 0.29 pp.

Being responsible for hiring decisions was significant and positively correlated with the likelihood of communicating a corruption risk. For those being responsible for hiring employees the estimated increase in the likelihood of communicating a corruption risk was 3.90 pp. Those who are directly involved in hiring may be more likely to speak about corruption risks being more often involved in situations that entail a hiring risk.

Understanding of the importance of communicating risks was positively correlated with the likelihood of communicating a risk and statistically significant on 0.1%-level. On average, correctly indicating that the situation in the vignette constituted a risk increased the likelihood of communicating a risk by 14.06 pp (see Section 2.3.4 for a further analysis on the understanding of the importance of communicating risks in the sample).

Trust in the appropriateness of the risk management system was also significantly correlated with the likelihood of communicating a risk. A unit increase of trust in the appropriateness of corruption risk management increased the likelihood to communicate risks on average by 0.13 pp.

Not having knowledge on the reporting channels was also associated with the likelihood of communicating risks. Responding “No” to having knowledge on the reporting channels significantly decreased the likelihood of communicating by -4.31 pp. Having knowledge (responding “Yes/Rather yes”) on the reporting channel was found insignificant. An additional regression to test the interaction between hiring responsibility and knowledge on the reporting channels found a positive and statistically significant effect on the likelihood of communicating risks from being responsible for hiring and having knowledge on reporting channels, emphasising the need to provide those responsible for hiring officials the information on how to communicate risks (Annex N).

The agency where one works at, career length in the public administration measured in years, gender and perceived fairness of the hiring system were not found to significantly impact with the likelihood of communicating a risk. Interactions between treatment and covariates were also found insignificant (see Annex K). The result of no statistical differences in the likelihood of risk communication between the agencies indicates that the risk communication culture is relatively similar across Slovak ministries and other central authorities.

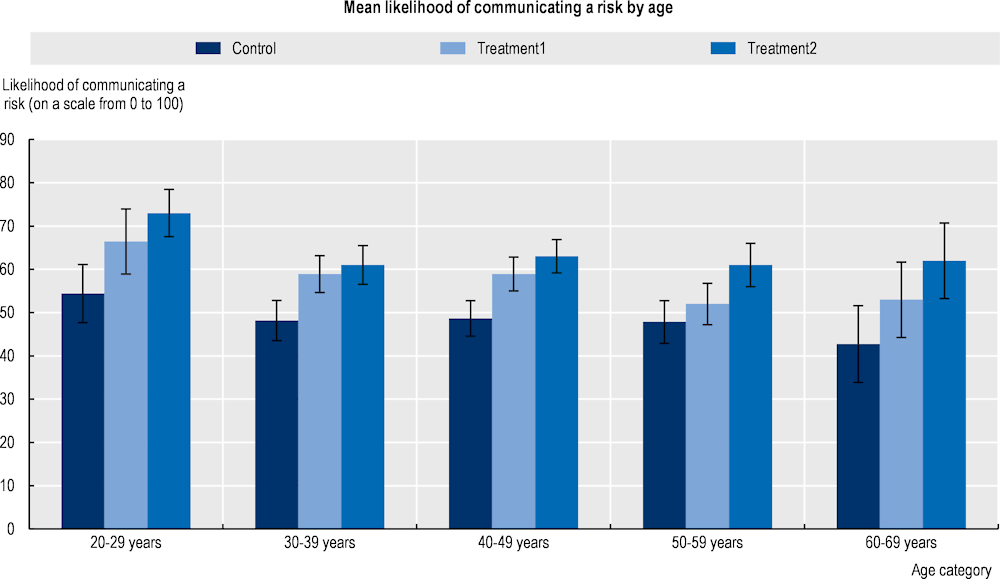

Age, measured in years, was negatively correlated with the likelihood of communicating a risk: the older the respondent, the less likely the respondent is to report a risk and the younger someone is, the likelier they are to communicate a corruption risk. An increase in age by one unit is expected to decrease the likelihood of communicating by -0.25 pp, assuming, that all other factors are held constant. Previous literature has reported that people may have a tendency to prefer to maintain the current state of affairs instead of welcoming change, which could also explain senior officials lower likelihood for communicating risks (Samuelson, W. and Zeckhauser, R., 1988[8]).The result is visually presented in Figure 2.5, and is also consistent across the treatments; the bars for the youngest age group are higher than for the remaining age groups across the treatments.

Figure 2.5. Younger respondents (20-29 years) were significantly more likely to communicate risks, compared to older respondents

Bar graph of the mean likelihood of communicating a risk by age and treatment assignment, with error bars

Note: The error bars display the 95% confidence intervals.

2.3.2. The treatments slightly improve general feelings of safety among the respondents

The general feeling of safety among the respondents was fairly low - overall, less than half of the respondents felt safe when communicating risks (i.e., approximately half of the respondents feel less safe than 50 on a scale from 0 to 100 when they communicate risks). The regression output table for the analysis with the dependent variable “General feelings of safety” is summarised in Table 2.4. An OLS regression with robust standard errors estimated the effect of the two treatments, secondary outcome variables and covariates on general feelings of safety.

To investigate whether general feelings of safety while communicating a risk were correlated with who participants prefer communicating a risk to, feelings of safety were measured twice on a scale from 0 to 100 (see Annex A). First, a general question on How safe do you feel about raising this risk? was asked (henceforth referred to as “General feelings of safety”), after which participants were asked to whom they would prefer communicating a corruption risk (Who would you prefer to raise this risk with? your manager; HR; the Anti-corruption Coordinators or others) after which they were asked how safe they would feel about raising the risk with the entity they indicated (e.g. How safe do you feel about raising this risk with your manager?) (referred to as “Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder”).

Table 2.4. The treatments had a relatively small yet significant effect on general feelings of safety among the respondents

Regression output table, OLS with robust standard errors. Dependent variable: General feelings of safety

|

OLS with robust standard errors |

|

|---|---|

|

Understanding of a risk (T1) |

3.168* (1.348) |

|

Exemplary leadership (T2) |

3.356* (1.329) |

|

Whom to communicate |

|

|

ACC |

-3.685 (1.894) |

|

Manager |

3.309 (1.846) |

|

Other |

-9.606*** (2.515) |

|

Agency |

0.0672 (0.111) |

|

Responsible for hiring |

8.702*** (1.814) |

|

Understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks |

4.858*** (1.171) |

|

Appropriateness of risk management |

0.262*** (0.0305) |

|

Perceived fairness of the hiring process |

0.236*** (0.0293) |

|

Knowledge on the reporting channels |

|

|

Yes |

6.752*** (1.258) |

|

No |

1.149 (1.972) |

|

Age |

0.00923 (0.0706) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

-0.878 (1.545) |

|

Male |

1.264 (1.623) |

|

Career length in public administration |

0.0471 (0.0692) |

|

Intercept |

6.403 (3.691) |

|

N |

2537 |

|

R2 |

0.291 |

|

adj. R2 |

0.286 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

All the effects are relative to the baseline of 6.40 (the intercept, the estimate for the control group). All the results are calculated based on the assumption that all the other variables are held constant.

The two treatments do increase general feelings of safety among the respondents, yet the effect sizes are small. Respondents in the Understanding of a risk-treatment felt on average 3.17 pp safer compared to the control group, ceteris paribus. Respondents in the Exemplary leadership-treatment felt on average 3.36 pp safer compared to the control group.

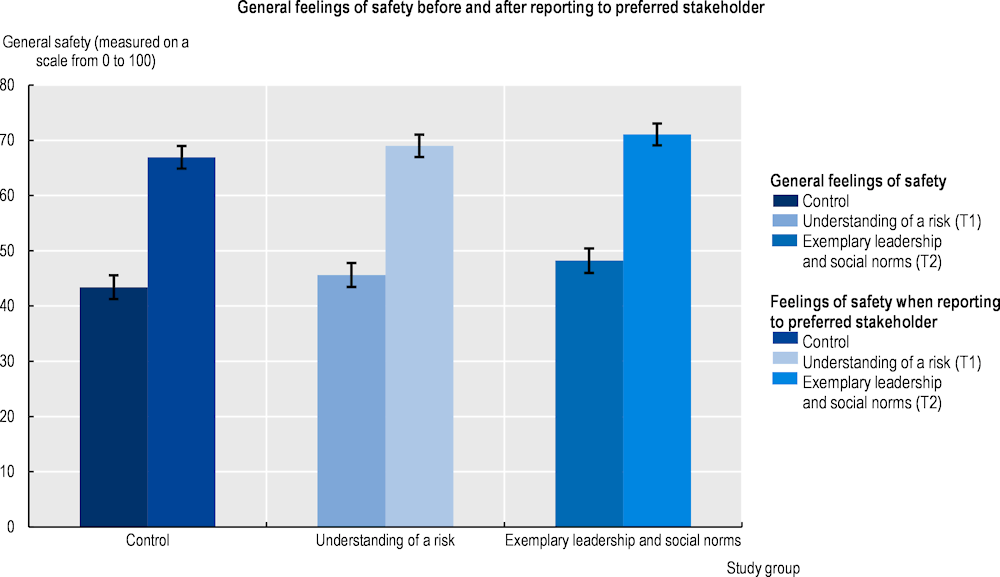

Figure 2.6 visually presents this result - after the respondents had a clearer idea of whom to communicate a corruption risk, they felt safer, irrespective of the study group. The sense of safety after being asked to whom respondents prefer communicating a risk is significantly higher, compared to the values for general safety, entailing, that people reported feeling safer once taking into account their responses to “Who would you like to raise this risk with?”.

Figure 2.6. The respondents felt safer communicating a risk when communicating it to their preferred stakeholder

Bar graph of general feelings of safety before and after communicating to preferred stakeholder, by treatment

Note: The error bars display the 95% confidence intervals.

Preferring to communicate a risk to ‘other’ decreased general feeling of safety by -9.61 pp, compared to communicating a risk to HR (the intercept, 6.40). The relationships between preferring to report a risk to ACC or a manager, and general safety, were insignificant.

Being responsible for hiring was significantly and positively associated with general feelings of safety. Overseeing hiring decisions was associated with an increase in general feelings of safety by 8.70 pp.

Respondents correctly judging the situation in the vignette as a risk felt on average safer, compared to those who did not identify the situation in the vignette as a risk. On average, understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks improved general feelings of safety by 4.86 pp.

Trust in the risk management system was significantly correlated with general feeling of safety. A unit increase in trust in the corruption risk management was associated with an increase of 0.26 pp in general safety.

The fairer the respondents view the hiring process, the safer they feel. A unit increase in the perceived fairness of a hiring process significantly increased feeling of general safety by 0.24 pp.

Lastly, having knowledge on the reporting channels (Yes/Rather yes) was positively and significantly associated with general feelings of safety. Having knowledge on the reporting channels increased general feelings of safety by 6.75 pp. The relation between not having knowledge on the reporting channels and general feelings of safety was insignificant.

2.3.3. Respondents feel safest when communicating risks to specific stakeholders

Majority of the respondents (n = 1116) indicated a preference to report a risk to their manager meaning that communicating a risk to manager is the most common option. The next preferred channel for risk communication (n = 838) were the Anti-corruption Coordinators, and HR was the least preferred channel to communicate risks (n = 279). 304 respondents indicated a preference for not communicating a risk at all, or to report a risk to someone else. The regression results for Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder, are summarised in Table 2.5. All the effects are relative to the baseline of 38.12 (the intercept, the estimate for the control group) and all the results are calculated based on the assumption that all the other variables are held constant.

Table 2.5. Those who responded preferring communicating a risk to their manager feel the safest, compared to other communication alternatives

Regression output table, OLS with robust standard errors. Dependent variable: Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder

|

OLS with robust standard errors |

|

|---|---|

|

Understanding of a risk (T1) |

2.819* (1.278) |

|

Exemplary leadership (T2) |

2.495* (1.259) |

|

Whom to communicate |

|

|

ACC |

-0.149 (1.752) |

|

Other |

3.484 (2.587) |

|

Manager |

11.08 *** (1.704) |

|

Agency |

-0.0353 (0.105) |

|

Responsible for hiring |

3.414* (1.629) |

|

Understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks |

6.517*** (1.037) |

|

Appropriateness of risk management |

0.225*** (0.0281) |

|

Perceived fairness of the hiring process |

0.206*** (0.0273) |

|

Knowledge on the reporting channels |

|

|

Yes |

5.194*** (1.260) |

|

No |

-0.718 (1.976) |

|

Age |

-0.182** (0.0663) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

2.016 (1.534) |

|

Male |

-0.605 (1.600) |

|

Career length in public administration |

0.0507 (0.0640) |

|

Intercept |

38.12*** (3.534) |

|

N |

2537 |

|

R2 |

0.266 |

|

adj. R2 |

0.261 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The “Understanding of a risk” treatment is significantly and positively associated with Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder. Respondents in the “Understanding of a risk” treatment felt 2.82 pp safer, than respondents in the control group. The relationship between the “Exemplary leadership” treatment and Feelings of safety was also significant and positive. The “Exemplary leadership” treatment was estimated to increase feeling of safety by 2.50 pp.

Preferring to communicate a risk to manager was positively and significantly correlated with Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder. Preferring to report a risk to manager increased safety by 11.08 pp, compared to preferring to communicate to HR (the intercept, 38.12). The relationships between communicating a risk to ACC, HR and Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder were not statistically significant.

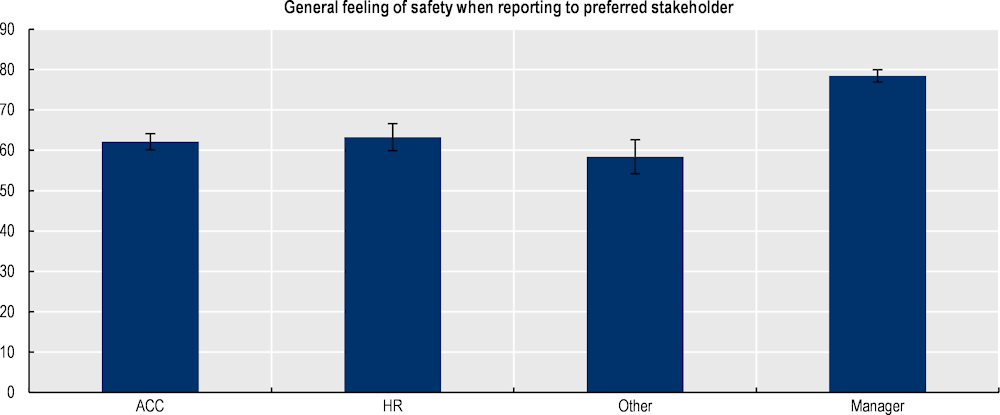

Figure 2.7 presents the means of the Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder, plotted by the four risk communication alternatives. Those who prefer communicating a risk to a manager clearly felt the safest, whereas respondents who prefer communicating to other felt the least safe.

Figure 2.7. The respondents felt the safest when preferring to report a risk to a manager, and the least safe when communicating a risk to 'other'

Bar graph of Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder, by the reporting channels

Note: Error bars display the 95% confidence intervals.

Hiring responsibility was significantly associated with the feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder. Being responsible for hiring decisions and while communicating a risk to a preferred stakeholder increased feeling of safety by 3.41 pp.

Understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks was positively and significantly correlated with Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder. A unit increase in understanding the importance of speaking up about a corruption risk increased general safety by 6.52 pp.

Trust was significantly and positively associated with Feelings of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder. A unit increase in trust increased general safety by 0.23 pp.

Having knowledge on reporting channels (Yes/Rather yes) was positively and significantly correlated with feeling of safety when communicating to preferred stakeholder. Having knowledge on reporting channels was associated with a 5.19 pp increase in general safety.

Senior respondents were less likely to feel safe while communicating a risk. A unit increase in age significantly decreased safety by -0.18 pp. Younger respondents therefore felt safer communicating a risk after being asked the respondents whom they prefer communicating a corruption risk to.

2.3.4. Understanding the importance of communicating a risk is low in the whole sample

On average, 30.8% of the respondents in the total sample correctly indicated that the situation in the vignette constitutes a risk which confirms the finding in the diagnostic analysis that the general understanding of a risk in the public administration is low. Understanding of a risk was highly significantly correlated with the likelihood of communicating a corruption risk and general feeling of safety. The understanding of a risk was further investigated, as one of the objectives of the treatment 1 (Understanding of a risk) was to improve the understanding of a risk among the respondents and in the diagnostic analysis, one of the key findings was that the understanding of a risk among the public sector employees was lacking.

Table 2.6 summarises the descriptive statistics for measuring understanding the importance of communicating a risk by the treatment variable. The percentages for correctly indicating that the situation constitutes a risk is similar across the treatments.

There is a slight difference in the means in understanding the importance of speaking up about a risk between the three study groups, however the difference is not statistically significant. This means that the Understanding of a risk-treatment did not significantly improve the understanding of the importance of communicating risks compared to the other study groups. Instead, the effect of the treatments could be caused by appealing to social norms. Previous studies have found a significant effect simply from prompting and reminding people to encourage favourable behaviours with messages appealing to social norms in the context of anti-corruption policies (Stahl, C, 2022[9]).

Table 2.6. Descriptive statistics for the variable “Understanding of a risk”, by treatment

|

Group (N) |

Mean |

Nr correct responses* |

% correct responses of the sample |

Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Treatment 1 (838) |

0.318 |

267 |

31.9% |

0.466 |

|

Treatment 2 (836) |

0.338 |

283 |

33.8% |

0.473 |

|

Control (863) |

0.286 |

247 |

28.6% |

0.452 |

|

Total (2537) |

0.314 |

783 |

30.8% |

0.464 |

Note: *number of respondents who correctly indicated that the situation is a risk.

2.3.5. Trust in the risk management system is dependent on knowledge of the reporting channels

Table 2.7 presents the results from an OLS regression with trust in the risk management system as the dependent variable. All the effects are relative to the baseline of 9.44 (the intercept, the estimate for the control group) and all the results are calculated based on the assumption that all the other variables are held constant.

Table 2.7. Those who indicated preferring to communicate a risk to ‘other’ (rather than managers, anticorruption coordinators or the HR) had the lowest trust

Regression output results. Dependent variable: appropriateness of a risk management system

|

OLS with robust standard errors |

|

|---|---|

|

Understanding of a risk (T1) |

-0.525 (0.975) |

|

Exemplary leadership (T2) |

-1.135 (0.968) |

|

General feelings of safety |

0.140*** (0.0164) |

|

Agency |

0.120 (0.0778) |

|

Responsible for hiring |

-1.329 (1.304) |

|

Understanding of the importance of speaking up about risks |

0.851 (0.858) |

|

Perceived fairness of the hiring process |

0.561*** (0.0182) |

|

Knowledge on the reporting channels |

|

|

Yes |

5.889*** (0.973) |

|

No |

-2.691 (1.543) |

|

Whom to communicate |

|

|

ACC |

1.350 (1.499) |

|

Other |

-2.144 (1.922) |

|

Manager |

2.176 (1.442) |

|

Age |

0.0575 (0.0498) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

0.338 (1.145) |

|

Male |

1.241 (1.207) |

|

Career length in the public administration |

-0.0495 (0.0500) |

|

Intercept |

9.443** (2.767) |

|

N |

2537 |

|

R2 |

0.517 |

|

adj. R2 |

0.513 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The relationship between the two treatments and trust is not statistically significant.

General safety is statistically significantly correlated with trust in the risk management system. A unit increase in general safety increases trust by 0.14 pp.

Perceived fairness of the hiring process is significantly and positively associated with trust in the risk management system. An increase in fairness of the hiring process increased trust by 0.56 pp.

Knowledge on reporting channels was also positively and significantly related to trust in the risk management system. Having knowledge of the reporting channels increased trust by 5.89 pp.

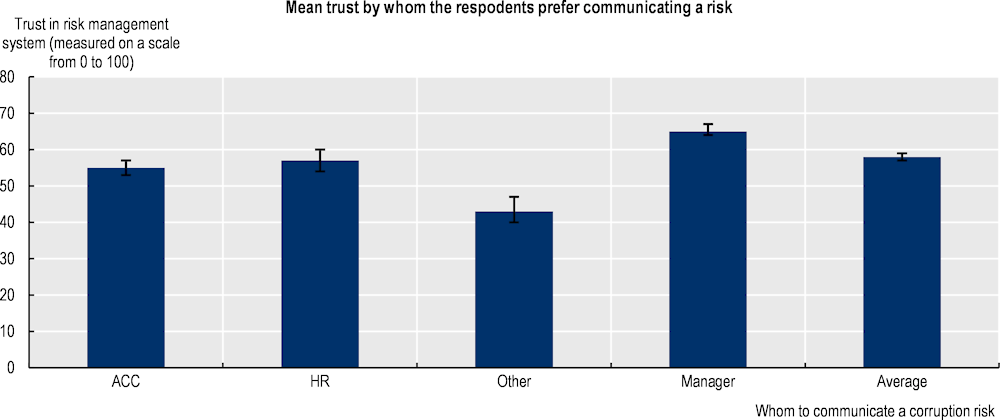

None of the reporting channels (ACC, other, manager (HR is the baseline) were significantly correlated with trust. Figure 2.8 illustrates the mean of trust in a risk management system by whom to communicate a corruption risk. Respondents who preferred to communicate a risk to a manager seem to report the highest trust on the risk management system. As the regression results shows, respondents who preferred to communicate a risk to “other”, seemed to have the lowest trust in the risk management system. The last column presents average trust in risk management system.

Figure 2.8. Respondents who preferred to communicate a risk to a manager had the highest trust in the risk management system, and those who communicate to ‘other’, had the lowest

Bar graph of the appropriateness of a risk management system by whom to communicate

Note: The error bars display the 95% confidence intervals.

In addition, from analysing the comment box for those the respondents who indicated communicating a risk to “other”, these respondents mainly preferred to report a risk to nobody, or to a reliable instance outside of the organisation. Many of these respondents indicated that they do not know whom they would communicate a risk to. Many reported that they would not communicate the risk in the vignette, especially to anyone working in the same organisation – examples of whom the respondents would consider communicating a risk to were independent and impartial instances, such as at high level in the European Union. Some respondents reported that they would communicate a risk to a corruption coordinator outside of the organisation, but not an ACC within the organisation. Many also indicated that they would communicate to a colleague if they felt they can trust their colleagues. A few also chose to communicate a risk to family or friends, i.e., to none of the official risk communication channels. Some of those who indicated communicating a risk to “other” also expressed having low trust in the system, which could be one of the factors explaining the seemingly negative relationship between communicating to “other”, and trust in the risk management system.

References

[4] Banerjee, R. (2016), On the interpretation of bribery in a laboratory corruption game: moral frames and social norms.

[6] Bhal, K. T., and Dadhich, A. (2011), Impact of ethical leadership and leader–member exchange on whistle blowing: The moderating impact of the moral intensity of the issue.

[3] Bicchieri, C., & Xiao, E. (2009), Do the right thing: but only if others do so. Journal of.

[2] Government of the Slovak Republic (2018), Anti-Corruption Policy of the Slovak Republic for the years 2019-2023, https://www.bojprotikorupcii.gov.sk/data/files/7130_protikorupcna-politika-sr-2019-2023.pdf?csrt=1785855676555738388 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

[1] OECD (2022), OECD Integrity Review of the Slovak Republic: Delivering Effective Public Integrity Policies, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/45bd4657-en.

[7] OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8ccf5c38-en.

[8] Samuelson, W. and Zeckhauser, R. (1988), “Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of risk and uncertainty”, pp. 1, pp.7-59.

[9] Stahl, C (2022), Behavioural insights and anti-corruption. Executive summary of a practitioner-tailored review of the latest evidence (2016-2022).

[5] van Roekel, A. (2021), “Activating employees’ motivation to increase intentions to report wrongdoings: evidence from a large-scale survey experiment.”, Public Management Review, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–23., https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.2015184.

Note

← 1. No responses were received from the following departments: Judicial Council of the Slovak Republic, National Security Office, Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic and Supreme Audit Office. The General Prosecutor’s Office was not included in the experiment. Due to the low sample sizes, the following categories of the Agency-variable was excluded from the analysis: Association of Towns and Municipalities in the Slovak Republic, the Ministry of Economy, and the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sports.