This chapter discusses the long-term care system in Croatia. It presents the social benefit framework composed of cash and in-kind benefits that support older people at home and in long-term care facilities. It assesses the coverage of these benefits. It studies the eligibility criteria to understand their impact on the benefits’ coverage. Finally, it discusses the generosity of the benefits, the affordability of long-term care and the estimated total long-term care expenditure.

Improving Long-Term Care in Croatia

2. The supply of formal long-term care is low and uneven in Croatia

Abstract

Given growing long-term care (LTC) needs, higher than EU-average poverty rates and the low supply of health care at home, public support to formal LTC will continue to play a fundamental role in Croatia. The social sector is the main building block of such public support. However, the social sector faces challenges that hinder its capacity to meet the growing LTC needs. The social benefit framework comprises a series of benefits that lack harmonised eligibility criteria and have strict means-testing rules instead of a coherent and comprehensive system. As a result, there are many gaps in coverage and equity. In addition, the LTC system is underfunded: the social benefits are not generous, formal LTC is unaffordable for most people and the estimated LTC expenditure as a share of GDP is among the lowest of EU countries.

Public support for long-term care is fragmented and based on disability benefits

Croatia does not have a specific legislation on LTC. Instead, the division of roles and responsibilities in the legislation stems from historical legacies between the social and the health sectors. Responsibilities are shared between a range of public authorities, including the Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy, the 136 Social Welfare Centres, the Ministry of Health, and the Croatian Health Insurance Fund. This split is accompanied by a vertical division of responsibility at different institutional levels (national and counties). In addition, many municipalities and NGOs provide day care and other LTC services, but the paucity of data limits the collection of information.

The Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy oversees the legislation of social care, the network of social care entities and monitors the social welfare system. In 2020, the Ministry of Demographics, Family, Youth and Social Policy and the Ministry of Labour and Pension System merged into the Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy.

The LTC public support comprises seven benefits that are in-cash or in-kind. Two are in-cash benefits – the assistance and care allowance and the personal disability allowance – and the others are in-kind services of help at home (the home assistance allowance and the organised housing1) or in residential settings, such as nursing home, family homes and foster families. These benefits and allowances are funded by the state with two exceptions. Counties are responsible for the operating costs of homes for older people and people with disability. They also developed their nursing homes that they fund entirely, although some sources of revenue can originate from the state.

The coverage of social benefits is low

The Croatian public support for older dependent people at home is mainly based on the two cash transfers oriented towards people with disability. These assistance and the disability allowances have different objectives. The assistance and care allowance aims to cover the care needs of people with disabilities, while the personal disability allowance intends to provide a basic income to people with disability for any daily life need, which can help to meet care needs but also other daily needs. Almost 4% of older people received the assistance and care allowance and 0.7% of older people the disability allowance in 2018. About 31 780 older people benefited from the assistance and care allowance – 45% of all beneficiaries of all ages – while about 5 660 older people received the personal disability allowance – 19% of all the recipients (Table 2.1).

Access to the LTC cash benefits is based on one standardised need assessment across the country, ensuring equitable access throughout the country. The Institute for Expertise, Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment of Persons with Disabilities performs the assessment. This institute was under the authority of the former Ministry of Labour and the Pension System and is now in the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy.

Both transfers are not very generous relative to the minimum wage: the personal disability allowance represents up to 40% of the minimum wage and the assistance and care allowance between 11% to 16% of the minimum wage. The assistance and care allowance can be provided fully or partially depending on the level of disability. Such cash transfers have the advantage of lower administrative and logistical costs and are quick to implement or modify. However, there is relatively little control over how the money is spent by beneficiaries.

Table 2.1. Number of recipients of benefits and services and rate per 1 000 older people

|

Benefits |

Number of older people |

Rate per 1 000 older people |

|---|---|---|

|

Home assistance (in-kind) |

3 940 |

Five per 1 000 |

|

Assistance and care |

31 780 |

Thirty-nine per 1 000 |

|

Personal disability |

5 660 |

Seven per 1 000 |

|

Accommodation |

24 445 |

Thirty per 1 000 |

|

Home health care from nurses and physiotherapists |

69 654 |

Eighty-six per 1 000 |

Note: Beneficiaries of foster care under age 65+ are included in the Accommodation category. Data refer to 2018.

Source: OECD Questionnaire on health and social care for older people, 2019-20 (Ministry of Demographic, Family, Youth and Social policy), GODIŠNJE STATISTIČKO IZVJEŠĆE O DOMOVIMA I KORISNICIMA SOCIJALNE SKRBI U REPUBLICI HRVATSKOJ U 2018. GODINI, GODIŠNJE STATISTIČKO IZVJEŠĆE O DRUGIM PRAVNIM OSOBAMA KOJE OBAVLJAJU DJELATNOST SOCIJALNE SKRBI I KORISNICIMA SOCIJALNE SKRBI U REPUBLICI HRVATSKOJ U 2018. GODINI.

The age profile of the cash benefit recipients has evolved in recent years. There was a small drop of about 1 850 recipients of the assistance and care allowance between 2018 and 2016 entirely driven by a decrease of recipients aged 75 years and over. The number of beneficiaries aged 65-74 years old of the assistance and care allowance has increased over the same period. As for the disability allowance, the number of beneficiaries increased by about 3 640 recipients over the same period. The strongest increase is among the recipients aged 75 years and over. This increase is logical: the disability allowance was designed for adults with disability, before population ageing fastened, and now the pool of eligible people with severe disabilities is increasing with population ageing.

In-kind home assistance remains limited in coverage. Home assistance covers house chores, personal care, preparation of meals and other daily needs. About 0.5% of older people Croatians received in-kind home assistance in 2018. Contrary to the beneficiaries of the cash benefits, the number of beneficiaries increased among all age groups between 2016 and 2018. The services provided by the in-kind benefit were mostly related to housework (36%), food (25%), personal hygiene (12%) and other personalised daily needs (27%) in 2018. Over half of recipients were women, but an increasing number of men were receiving home assistance. The number of female recipients decreased, driven entirely by those aged 75 years and over, while the total number of recipients aged 65-74 increased over the period 2016-2018.

The rates of home assistance beneficiaries are well lower in all counties than the rates of the assistance and care allowance and they are much more uneven across counties. This uneven distribution reflects partly different eligibility criteria (see next section). The counties with most home assistance beneficiaries are Osječko baranjska, Sisačko moslavačka, Ličko senjska and Karlovačka.

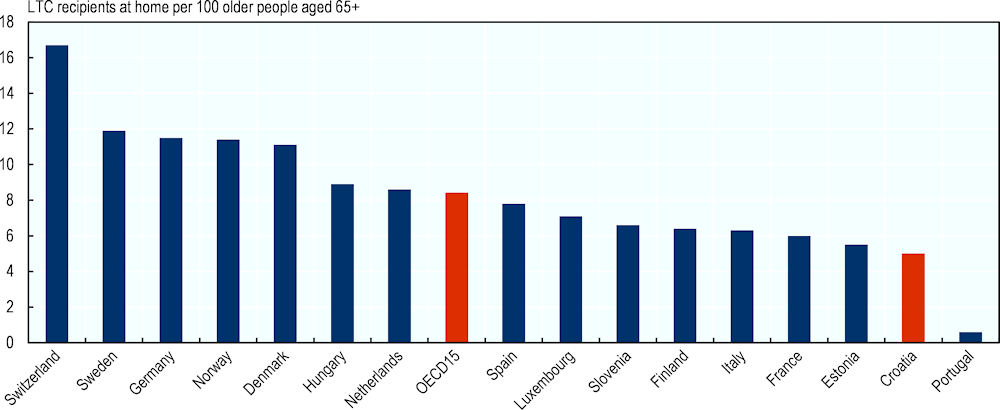

Overall, the rate of LTC beneficiaries at home per 100 older people aged 65 years and over was five per 100 older people in Croatia, compared with eight on average across 15 European countries (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. The rate of LTC recipients at home is lower in Croatia than across 15 European countries

Note: Data refer to 2017, except for the Netherlands and Slovenia (2016) and Croatia (2018). For Croatia, the home help recipients are those aged 65 years and over receiving the assistance and care allowance, the personal disability allowance, and the home assistance service. The number of beneficiaries is overestimated as people can be eligible for home assistance and one of the two cash benefits (the personal disability allowance of the assistance and care allowance).

Source: OECD Health Database 2020 and OECD Questionnaire on health and social care for older people, 2019-20 (Ministry of Demographic, Family, Youth and Social policy).

To partly offset the lack of home care services and to promote female employment, the Ministry of Labour and Pensions developed the Zaželi programme with associations and local authorities and the financial support of the European Social Fund. The programme hires women to work as home assistants of people with disability and older people in rural areas and islands where they are extremely hard to reach and where unemployment rates are higher than the Croatian average. The programme has two main objectives: reduce poverty among the most vulnerable people living in underprivileged areas and fill in a gap in the provision of home help. To be eligible, women must be unemployed and have only a primary or secondary education (up to high school degree). Women are guaranteed a full-time contract of up to 30 months at the minimum wage. Employed women receive a training up to a cost of HRK 7 000 per woman to increase their future employability and reduce the poverty risk (Christiaensen et al., 2019[4]). The choice of the type and area of the training is at the discretion of employed women. The duration of the training must be between 2 months and 6 months and can be taken up during or after the employment period (see Annex B for more information on training activities).

The European Social Fund has funded the programme since 2014 and invested more than HRK 1.8 billion in over 750 contracts with associations and local authorities (European Social Fund +, 2022[5]). In 2019, close to 4 000 people had been assisted through the programme. The counties that had received most funds by 2019 were Osjecko-baranjska, Sisacko-moslavacka and Grad Zagreb. Social Welfare Centres identify older people in need of LTC and ensure that those receiving help through the programme are not also similarly supported by other public or subsidised services. For instance, Sisačko moslavačka is one of the counties with the highest numbers of women employed in the Zaželi programme since December 2017, and only five older people received the home assistance benefit in 2018, compared with 354 in 2015. The decrease may be partly related to the Zaželi programme. Eligibility criteria are not defined in the Guidelines for Applicants; recipients are selected based on a joint decision of the applicant (municipality, NGO, etc.), the Social Welfare Centres and other partners of the applicant, if any.

In Croatia, residential care is provided in nursing homes, family homes and foster families. Specifically, residential care is named accommodation in Croatia. The main providers of residential care are care institutions. They are administered by the state, counties or by private organisations such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or religious communities. Family homes and foster care families also provide residential care in private households for older people. Family homes and foster care for older people are uncommon options for residential care in EU countries. Family homes also exist in France, Belgium, and Ireland, but they are not well-developed.

Over 24 400 older people (and children) stayed permanently in an accommodation, of which about 10 915 older people lived in a county nursing homes in 2018. Over 5 700 older people stayed in non-state non-county homes and family homes cared for about 5 500 users. Over 2 100 older people and children lived in foster families. In addition, state home for older people took care of 168 older people in 2018. Furthermore, state home for mentally ill people cared for 1 125 older people with a mental health diagnosis.

State and county nursing homes operate at full capacity, leaving no extra beds for interested users, including those eligible for public support. In 2018, the occupancy rate reached 93% and over 5 000 older people submitted a bed request that was not realised. Older people are particularly interested in county nursing homes because the price is much lower than the real market price (Bađun, 2017[6]). In comparison, close to 700 bed requests were not met in non-public nursing homes, although the occupancy rate was also slightly lower (86%).

The distribution of nursing home is highly uneven across Croatia: almost half of the nursing homes were concentrated in only three counties in 2015. The city of Zagreb counted 22% (35) of the nursing homes, Split-Dalmatia 11% (18) and the County of Zagreb (17). The remaining nursing homes (57%) were spread relatively evenly across the other 18 counties.

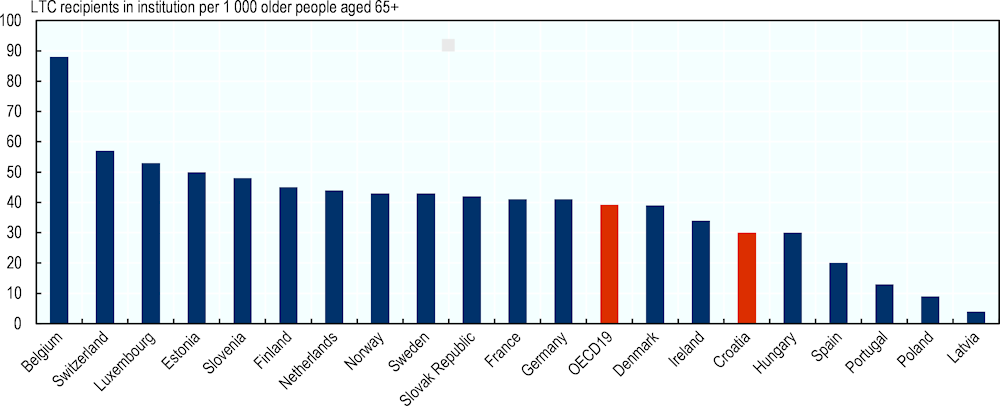

When turning to the coverage in residential care, EU comparisons suggest that the number of residents is low. Overall, at least 3% of older people lived in institutions in Croatia in 2018, compared with an OECD average of around 4% (Figure 2.2). Even though the share of people with LTC needs differs across countries, this rate likely indicates that Croatia has not developed residential care as much as other EU countries.

Figure 2.2. The rate of LTC recipients in institutions is lower in Croatia than across OECD countries

Note: Data refer to 2017 or latest year (2018 for Croatia). In Croatia, institutions entail all types of residential care, including foster homes (users aged 65+ but also children) and family homes.

Source: OECD Health Database 2020 and OECD Questionnaire on health and social care for older people, 2019-20 (Ministry of Demographic, Family, Youth and Social policy).

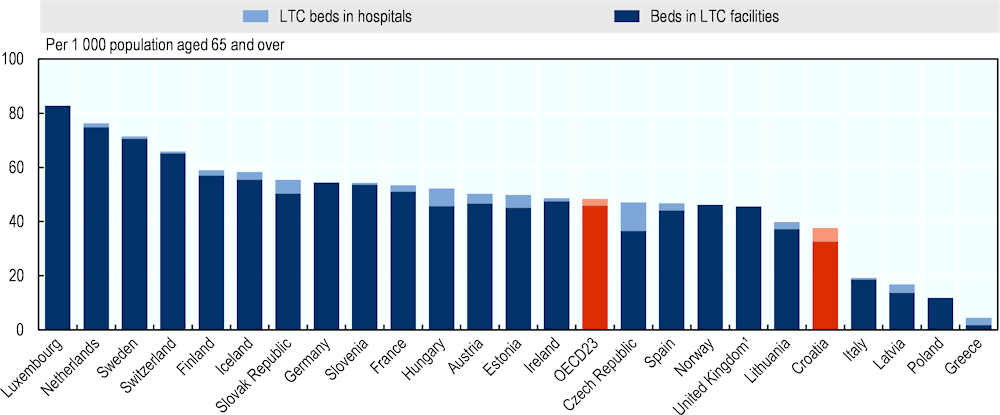

Even when factoring in LTC beds in hospitals, the overall rate of LTC beds (in residential care settings and hospitals) remains lower than in most other EU countries (Figure 2.3). Croatia had the third highest rate of long-term care beds in hospitals among EU countries, at 101 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2017. Long-term care beds in hospitals are for patients requiring long-term care due to chronic impairments and a reduced degree of independence in activities of daily living, including palliative care. They encompass beds for psychiatric and non-psychiatric curative (acute) care, from general hospitals, mental health hospitals and other specialised hospitals (Eurostat, 2019[7]).

Figure 2.3. The density of LTC beds is lower in Croatia than in most other OECD countries

Note: The three types of residential care are included for Croatia (nursing homes, foster homes (users aged 65+ but also children) and family homes). For foster families and family homes, data refer to the number of users and not the number of beds.1. The number of long-term care beds in hospitals is not available for the United Kingdom.

Source: OECD (2019[8]), Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en for all countries except Croatia, OECD Questionnaire on health and social care for older people, 2019-20 (Ministry of Demographic, Family, Youth and Social policy) for data on Croatian institutions and Eurostat Database for data on Croatian hospitals.

The low coverage is driven by eligibility criteria that limit coverage to those with low means

In Croatia, eligibility to long-term care support is asset-tested and income-tested. This applies to residential care and home care. Access to either depends on both income and asset-tests with a steep income-testing. For the assistance and care allowance, the income threshold of a single person represented 53% of the minimum wage and for the personal disability allowance, it was 40% in 2020, although not all incomes are considered. In addition, the amount of the personal disability allowance varies based on income, or in other words, the level of the personal disability allowance is income-tested. Asset-testing covers only non-primary residence in Croatia. In comparison, in other European countries and regions, the level of LTC benefits and schemes are mostly income-tested only (9 out of 21 EU countries or subareas) or both income-and asset-tested (8 out of 21 countries or subareas). The exact form of means-testing varies widely across EU and OECD countries.

Steeper asset testing and income testing apply for residential care and all beneficiaries should contribute to the total costs of their care, depending on their income. All beneficiaries of public support to residential care must contribute to the total costs of their care, the user share depending on their income. If the care recipients’ income is insufficient, they are required to sell the primary residence if they live alone and the county and/or the state must pay the remaining.

Eligibility for formal in-kind home assistance depends primarily on the support of family and friends, contrary to many other EU countries, and is not based on a single standardised need assessment. This means that individuals with sufficient support from family caregivers will not be eligible for formal support and rely entirely on relatives to receive family care or pay for the formal care. In addition, access to public support for home care services is not based on a single need assessment that is standardised across the country. It varies across the territory, so it is likely that older people with the same level of LTC needs receive different home care public support depending on where they are assessed.

The overwhelming majority of family carers are not compensated for their unpaid care. A carers status exists but only about 500 people received it in 2018 because the eligibility criteria for the carer status were very restrictive. Caregiver status targeted mainly parent caregivers of children with disabilities and only a spouse or a partner under age 65 could be formally recognised by the state as a caregiver if the care recipient needed permanent support to maintain life. Note that after the timing of authoring the report, the Social Welfare Act was modified with improved support to family carers (see Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. The law passed in 2022 improves support to family carers of older people with the most complex needs

In 2022, the Social Welfare Act NN 18/22 (https://www.zakon.hr/cms.htm?id=52195), 46/22 (https://www.zakon.hr/cms.htm?id=52192), 119/22 (https://www.zakon.hr/cms.htm?id=54052) made changes to social benefits and introduced under Section 11 modifications to the status of caregiver. The new eligibility criteria widen the pool of eligible family carers. One must be a parent or a household member who is physically and mentally able to provide care and who is sufficiently trained. The age limit of 65 years old was lifted. Caregivers are not eligible if the older person receives all-day day care or residential care.

The allowance for a caregiver is EUR 531 (HRK 4 000) per month, or EUR 597 (HRK 4 500) per month if the individual with severe disabilities cannot receive any support services in the community, or EUR 796 (HRK 6 000) if the person cares independently for two or more people with severe disabilities. The carer can take four weeks of compensated leave per year. The carer gains the rights to pension and compulsory health insurance and unemployment (Government of Croatia, 2022[9]). For reference, the gross minimum wage was increased to EUR 700 (HRK 5 274) per month in 2023. Compared with the previous caregiver allowance, it is much more generous and provides a good social protection.

The system is underfunded: Estimated long-term care expenditure is among the lowest of EU countries

The state spent about HRK 317.615 million in 2018 on the three benefits for people with LTC needs at home. The assistance and care allowance represented the bulk of spending (HRK 203.939 million), followed by the personal disability allowance (HRK 87.426 million) and home assistance (HRK 26.250 million). The average estimated cost per home recipient aged over sixty-five is about HRK 9 500 per year. In addition, the state spent HRK 1.195 million on the caregiver allowance. About 4 500 people received it (about 4 100 people were parents of children with disability and about five hundred people were older people’s caregivers).

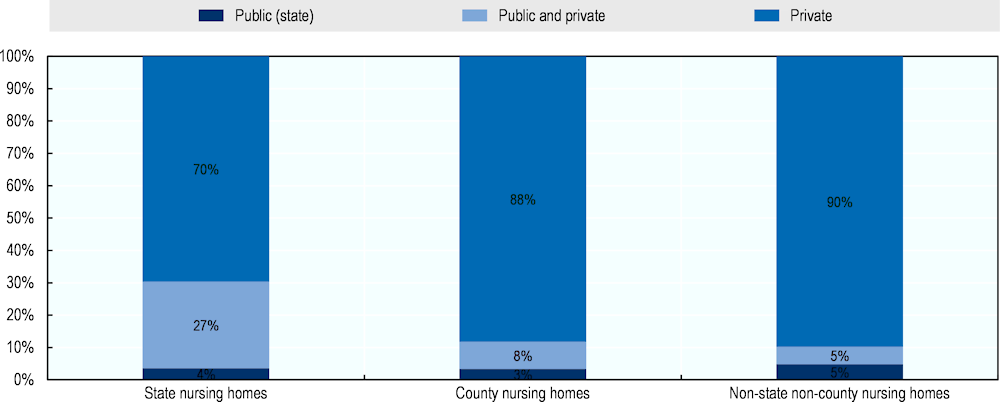

While the level of charges (or prices) paid by accommodations users or by the state are not available, it is worth noting that most of the charges are born by users rather than the state (Figure 2.4). In comparison, in almost all EU countries with available data, user contributions are set either as a share of the care recipient’s income or as a share of the total costs of care. Public support for residential care does not depend on the user’s means in only two countries: the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic (Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal, 2020[10]). Croatia offers a small allowance for the personal needs of accommodation users of HRK 100 per month to make sure that the care recipient will have some money left after paying for the user contribution. Many other EU countries also aim to guarantee a small minimum income for residents of LTC facilities.

Figure 2.4. The share of private funding for charges (or prices) was 70% or over in the three types of nursing homes

Source: GODIŠNJE STATISTIČKO IZVJEŠĆE O DOMOVIMA I KORISNICIMA SOCIJALNE SKRBI U REPUBLICI HRVATSKOJ U 2018. GODINI (data refer to 2018).

Funding of accommodations is very intricate. The state finances differently the state homes, the county nursing homes and the private providers. Because of the funding regulation between the state and the counties, it is possible to estimate expenditure of county nursing homes at about HRK 500 million. The counties were the first funders and if their funds are not sufficient to cover expenditure, the state covers the difference up to a specific limit. In 2018, the state spent HRK 164.550 million to finance county nursing homes.

With respect to health care expenditure, the Croatian health care system spent about HRK 520.9 million on long-term care in 2016. Hospitals spent HRK 367.2 million and providers of ambulatory health care HRK 153.6 million on long-term care, based on the SHA2 classification.

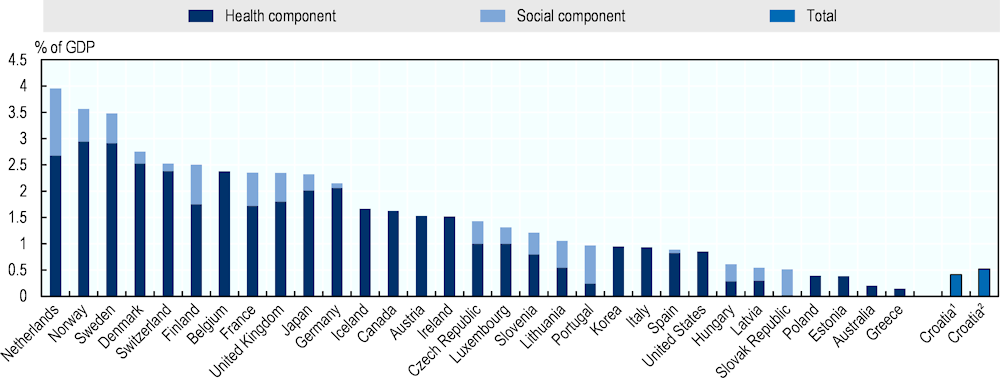

Overall, known expenditure presented on LTC benefits and health care sums up to an estimated HRK 1.573 billion, or 0.41% of GDP in 2018 (Figure 2.5). When including the Zaželi programme, it reached 0.52% of GDP in 2018. In comparison, the European Commission estimated that Croatia spent on long-term care 0.9% of its GDP in 2016. The difference is at least partly related to out-of-pocket money and spending in other long-term care settings, such as day care centres.

Figure 2.5. Total LTC spending is lower in Croatia than in almost all other OECD countries

Note: Data refer to 2017 or the latest year for all countries except Croatia (2018). 1. Expenditure comprises spending on benefits and allowances and health care (hospitals and ambulatory health care), but not the Zaželi programme funded by the European Social Fund. 2. Expenditure also includes the Zaželi programme.

Source: OECD estimates for Croatia and OECD Health Statistics 2019 for the other countries.

Total LTC spending remains well lower than in most other OECD countries, even with the higher EU estimates for Croatia. In 2017, the average across OECD countries was 1.58%. Only four countries, including Poland and Estonia, reported LTC spending under 0.4%. The Slovak Republic spent about 0.52% of its GDP on long-term care and Hungary 0.61%.

Public social protection has limited impact on poverty risks associated with needing and paying for professional home assistance

While there is some data on LTC spending in Croatia, there is more limited understanding of how affordable LTC is for older people who need it, and whether public social protection is effective at reducing the risk of poverty associated with LTC needs. In the absence of sufficient data on the needs, income and assets of older Croatians making use of LTC services, this report generates estimates of the affordability of care by using models of the LTC benefits framework matching them to survey responses on LTC needs (Box 2.2) (Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal, 2020[10]).

Box 2.2. Methodology used to estimate affordability of formal LTC services

The approach used to estimate the affordability of out-of-pocket costs of formal LTC services follows three steps: (1) matching the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) responses to four stylised cases of LTC needs, (2), estimating total costs, public support, and out-of-pocket spending for each respondent, and (3), generating national-level indicators of the effectiveness of social protection for LTC in old age.

The stylised cases are based on specific activities described in number of hours of need for help with ADL, IADL, and social activities (see Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal (2020[10]) for more details on each case). These cases span various levels of care severity (low, moderate, and severe) and diverse ways in which these needs can be met (professional home care and institutional care). Four cases are used here, as summarised in Table 2.2 below.

Table 2.2. Stylised cases of LTC needs used in this chapter

|

# |

Needs |

How needs are met |

Weekly costs of professional care in Croatia |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Low |

Around 6.5 hours of professional home care per week |

HRK 239.07 |

|

2 |

Moderate |

Around 22.5 hours of professional home care per week |

HRK 827.55 |

|

3 |

Moderate |

Around 10 hours of professional home care per week and 12.5 hours of family care provided by adult child |

HRK 367.80 (for professional part; opportunity costs of family care not included) |

|

4 |

Severe |

Around 41.25 hours of professional home care per week |

HRK 1 517.18 |

|

5 |

Severe |

Around 41.25 hours of institutional care per week |

HRK 669.23 |

Note: Detailed descriptions of the stylised cases are available in Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal (2020[10]), “The effectiveness of social protection for long-term care in old age”, https://doi.org/10.1787/2592f06e-en.

Source: OECD analyses based on the OECD Long-Term Care Social Protection questionnaire.

To determine how many older people in a population can be classified as having LTC needs as described in the stylised cases above, an internationally comparable source of data on these types of limitations is most appropriate. The SHARE provides such a source of data, with information on ADLs and IADLs. Limitations in ADL include difficulties in: (1) dressing, (2) walking across the room, (3) bathing/showering, (4) eating, (5) getting in/out of bed and (6) using the toilet. Limitations in IADL include difficulties (7) preparing a hot meal, (8) shopping groceries, (9) making telephone calls, (10) taking medications, (11) doing work around the house/garden, (12) managing money, (13) leaving the house independently and (14) doing personal laundry. SHARE waves 6 and 7 were used.

The matching methodology is based on a score of self-reported difficulties: reporting one to two limitations with ADL and IADL is considered equivalent to having low needs, reporting three to six is considered equivalent to having moderate needs, and reporting seven or more needs is considered equivalent to having severe needs. This matching method was selected based on a systematic set of tests to validate results.

The OECD worked with the Ministry of Demography, Family, Youth and Social Policy in 2019 to map assessment systems in use in Croatia to the stylised cases above. To do so, detailed descriptions of the abilities and limitations of the person in question, the services they require, and any other relevant assumptions, were given.

For each stylised case, older people may be eligible for different LTC benefits depending on the severity of their needs, their income and assets, and their family composition (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3. Public LTC benefits, schemes and services for stylised cases used in this chapter

|

Stylised case # |

Benefits, schemes, and services available |

|---|---|

|

1 |

Older people with low needs are not eligible for LTC benefits in Croatia. If the older person’s income is below 300-400% of the reference income, they will receive a subsidy for home assistance of HRK 119.54 per week. |

|

2 |

Older people with moderate needs on low incomes (below 300-400% of the reference income) can receive a subsidy for home assistance of HRK 413.78 per week, if the older person has not sold property in the previous year and has no support from family members. People with moderate needs are also eligible for the Assistance and Care Allowance (HRK 420 per month), assuming the older person has a significant impairment. |

|

3 |

Older people with moderate needs receiving in-kind support from an adult child are eligible for the Assistance and Care Allowance for HRK 420 per month. |

|

4 |

Older people with severe needs earning below 300-400% of the reference income are eligible for a subsidy for home assistance of HRK 758.59 per week. In addition, they qualify for either the Assistance and Care Allowance or the Personal Disability Allowance. In this chapter, it is assumed that the older person receives the Personal Disability Allowance, which is set at HRK 1 500 minus income (except pension income). |

|

5 |

Older people with severe needs and high assets can receive state support for accommodation if they have no support from family members. In this case, the State is entitled to claim a part or the whole value of this person’s property after death or cessation of institutional care corresponding to the value of accommodation costs. Older people on low income will get a benefit based on the formula: Collective support = Total cost – (Income – 100) since they are entitled to keep HRK 100 per month of their income. |

Note: Detailed descriptions of the stylised cases are available in Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal (2020[10]), “The effectiveness of social protection for long-term care in old age”, https://doi.org/10.1787/2592f06e-en.

Source: OECD analyses based on the OECD Long-Term Care Social Protection questionnaire.

The following subsection discusses estimates that are based on a simulation of what the total costs of care, public support and out-of-pocket costs would be should older people access LTC. These are not estimates of the actual amounts in the real world, as they do not consider barriers to access nor individual preferences for using public LTC benefits, schemes, and services. In addition, the estimates rely on SHARE, which data on income and asset may be of limited quality (income and asset are difficult data to collect well in general).

The stylised cases confirm that the share of total costs of LTC covered by public support is limited. This is because most respondents with low and moderate needs have a combination of income and assets that would disqualify them from receiving public support, based on SHARE data for LTC needs, income and assets. Around 95% and 81% of those over sixty-five with low and moderate needs, respectively, do not qualify for any financial public support for home assistance. The other 5% of older people with low needs are eligible to receive public support in the amount of 50% of the total costs of care, while 12% of those with moderate needs would see only 13% of the total costs of home assistance be covered by public social protection, 7% with moderate needs would get at least 50% coverage. Around 84% of older people with moderate needs receiving a mix of professional and family home care, the family part from an adult child, would not receive any financial public support, while 16% would see 26% of the total costs of the professional part of their care covered by the public social protection system.

For those estimated to have severe needs, around 89% are eligible to receive public support covering 23% of the total costs of home assistance, while the remaining 11% would see 73% of the total costs covered by public support. Around 77% of older people with severe needs would receive no financial public support for the total costs of institutional care, while the remaining 23% would see, on average, 34% of the total costs of care covered (the range is 4% to 73%).

Estimates on out-of-pocket costs (the share of the costs that are left after accounting for public support) indicate that relying only formal LTC is typically unaffordable. On average across all older people with LTC needs eligible for public support, older people with low needs would need to spend 47% of their income to pay the out-of-pocket costs of home assistance. On average, older people with moderate and severe needs would need to devote all their income to pay the out-of-pocket costs of professional home care. In institutional care, older people with severe needs would need to devote on average 94% of their income to cover out-of-pocket costs.

These estimates on out-of-pocket costs show that older people must rely on (unpaid) family care to afford meeting their care needs. Older people receiving a mix of professional and family home care, on average, would pay 41% of their income to cover the out-of-pocket costs of care.

Estimates on poverty risks associated with LTC needs indicate that public support in Croatia may not be well-aligned with ageing-in-place policies. Stylised cases indicate that public support for institutional care completely reduces poverty risks associated with needing LTC in Croatia, however public support for home care for low, moderate, and severe needs does not bring relative income poverty levels back to pre-LTC levels.

To promote ageing-in-place, public social protection systems need to consider that older people who stay in their communities must cover basic living costs that they would not face if they were institutionalised. Consequently, even though public support for older people with severe LTC needs is higher for home care than for institutional care in Croatia, this may not be doing enough to prevent older people in the community from being at risk of poverty. Older people who are at risk of poverty cannot afford to make any out-of-pocket payments or they will be at an increased risk of poverty (especially if they are also asset poor and thus cannot deplete their assets to pay for care).

Notes

← 1. Organised housing service is not analysed in this report because of the very low number of recipients.

← 2. System of Health Accounts. HC3 refers to long-term health care. Long-term health care comprises ongoing health and nursing care given to in-patients who need assistance on a continuing basis due to chronic impairments and a reduced degree of independence and activities of daily living (OECD/Eurostat/WHO, 2017[31]).