This overview summarises the key findings and policy recommendations of the report. It shows how the recent crises underscored the necessity to enhance the social contract in many countries, to make it inclusive of informal workers and their families, with the goal of building better and stronger societies.

Informality and Globalisation

1. Overview

Abstract

The three years since 2020 have presented the world with a series of challenges – from the COVID-19 crisis to Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine – which are greatly affecting the poorest and most vulnerable groups, in particular informal economy workers and their family members. In many parts of the world, these crises added to existing challenges and considerably eroded the social contract between citizens, the state, workers and enterprises. In fact, these crises underscored the extent to which most social contracts were already weak and eroded by years of globalisation and rapid technological change. Major gaps and shortcomings in labour and social protection systems were exposed, such as the lack of social support for workers in the informal economy, in particular for women, and the massive economic costs of inadequate social protection. These crises also highlighted the vulnerability of different actors to disruptions in global production, especially in GVCs built according to subcontracting models; and vulnerability to new ways of work that shifted the risk burden to workers. Overall, these crises underscore the necessity to enhance or even rethink the nature of the social contract in many countries, and to make it more inclusive of informal workers and their families.

Portraits of informality in world recovering from the COVID-19 crisis

Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, informal employment was already a major challenge in many countries

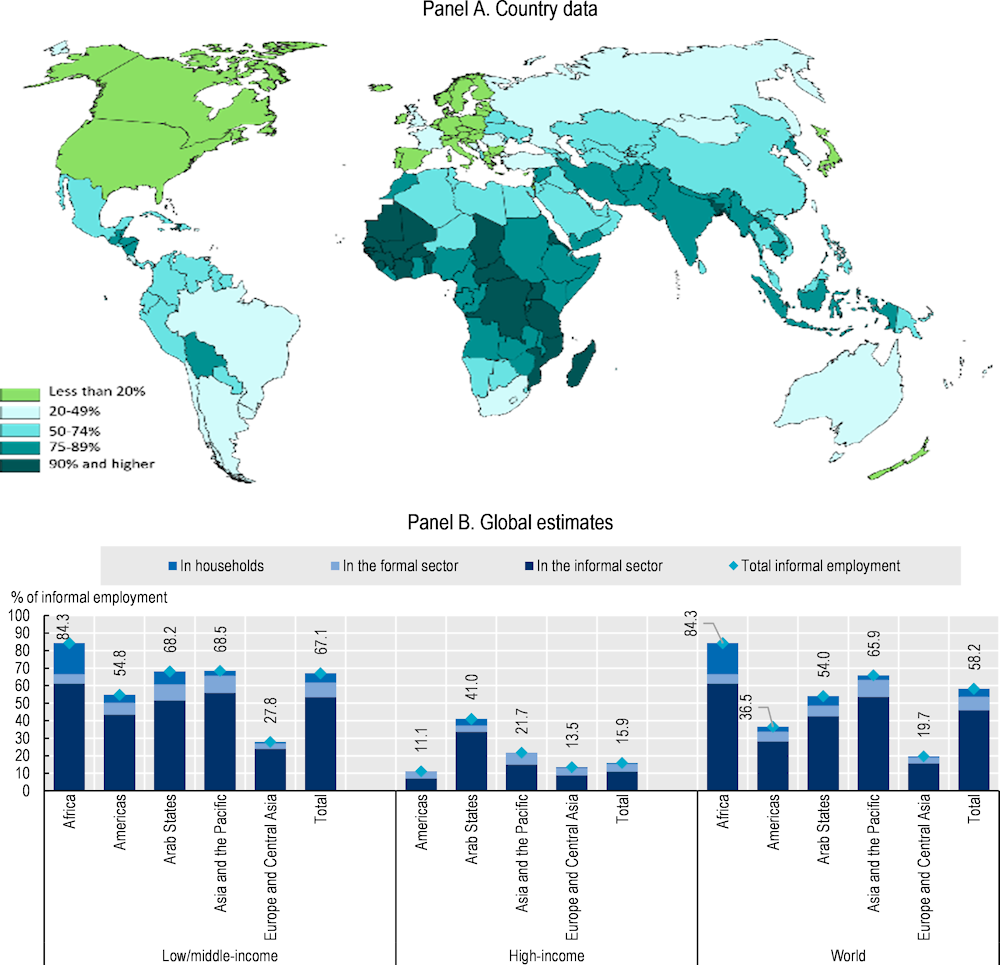

On the eve of the COVID-19 crisis, about 2 billion workers, or almost 60% of the world's adult labour force, were in informal employment (Figure 1.1). More than 80% of enterprises operated in the informal sector worldwide (ILO, 2023[1]).

Informal employment represents 89.0% of total employment in low-income countries, 81.6% in lower-middle-income countries, 49.7% in upper-middle-income countries and 15.9% in high-income countries.

The percentage is highest in Africa, but with significant differences between countries in the region, ranging from 15.0% in Seychelles to more than 90.0% in several African countries.

In Asia and Pacific, the rate of informal employment ranges from less than 20.0% in developed countries in the region, such as Australia or Japan, to almost 90% or more in Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, and Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

The Arab States have the third-highest regional level of informal employment (54.0%).

In the Americas, informal employment ranges from 9.8% in North America to 53.6% in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). There is also significant variation across the region, ranging from 24.5% in Uruguay to between 30.0% and 40.0% in Costa Rica and Chile, almost 80% in Guatemala and more than 80% in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Honduras and Nicaragua.

In Europe and Central Asia, informal employment represents 19.7% of total employment, standing at 13.5% in high-income countries and at 27.8% in middle-income countries. In Albania, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, at least one-half of workers hold informal jobs.

Figure 1.1. Informal employment dominates in the Global South

Informal employment as percentage of total employment

Note: A common set of operational criteria is systematically used to identify workers in informal employment and those employed in the informal sector. Own-account workers and employers are in informal employment if they run informal sector economic units (non-incorporated private enterprises without formal bookkeeping systems or not registered with relevant national authorities). Employees are in informal employment if their employers do not contribute to social security on their behalf or, in the case of missing answers in the questionnaires if they do not benefit from paid annual leave and paid sick leave. Contributing family workers are in informal employment by definition (ILO, 2003[2]; ILO, 2018[3]).

Source: (ILO, 2023[1]).

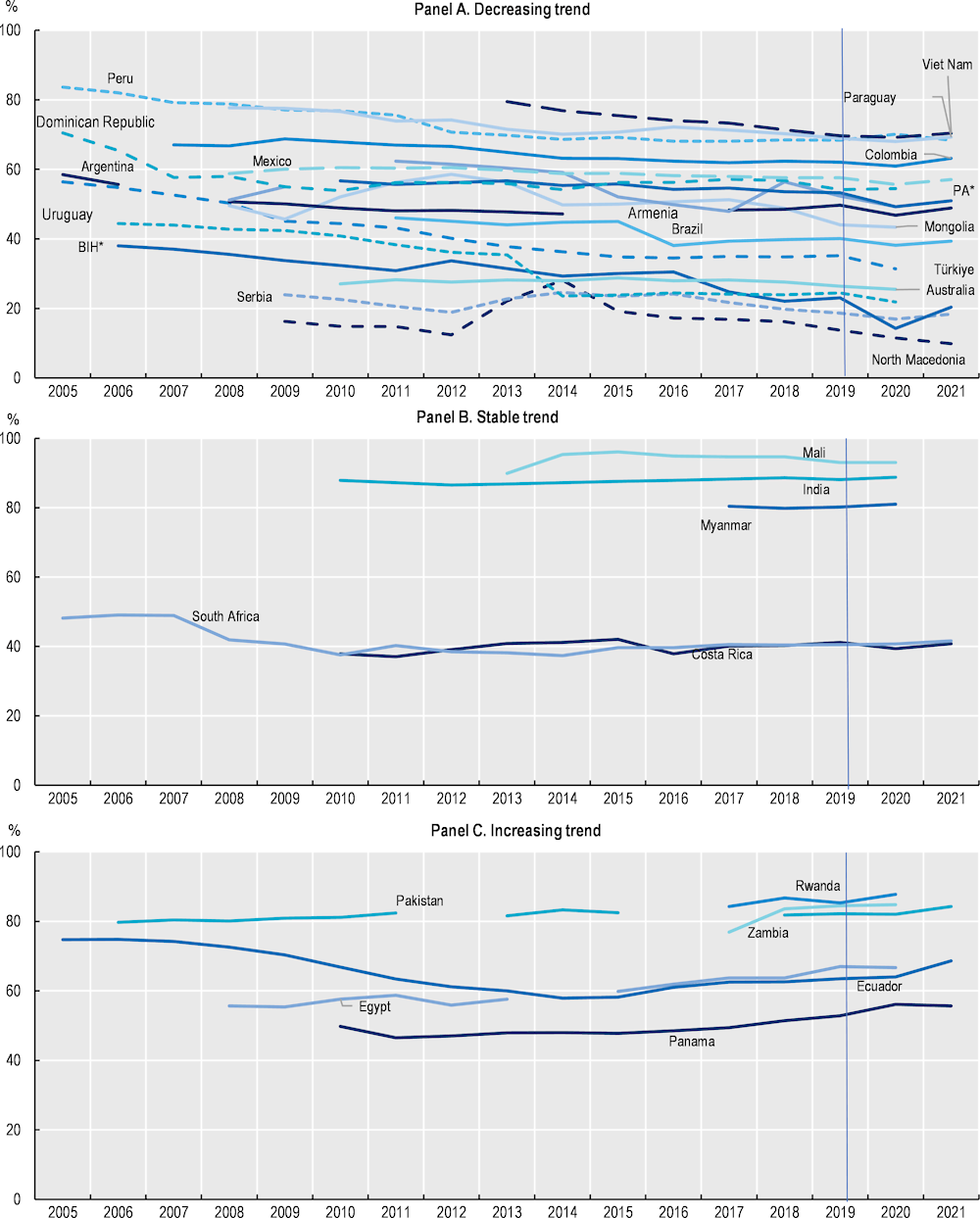

Informal employment trends also vary greatly across countries, with some countries making considerable progress towards formalisation, whereas others experiencing persistent or increased levels of informal employment (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Global trends in informal employment

Informal employment as percentage of total employment

Note: See note under Figure 1.1, Panel A. *PA: Palestinian Authority. *BIH: Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Source: (ILO, 2023[1]).

The COVID-19 crisis disproportionately affected the informal economy

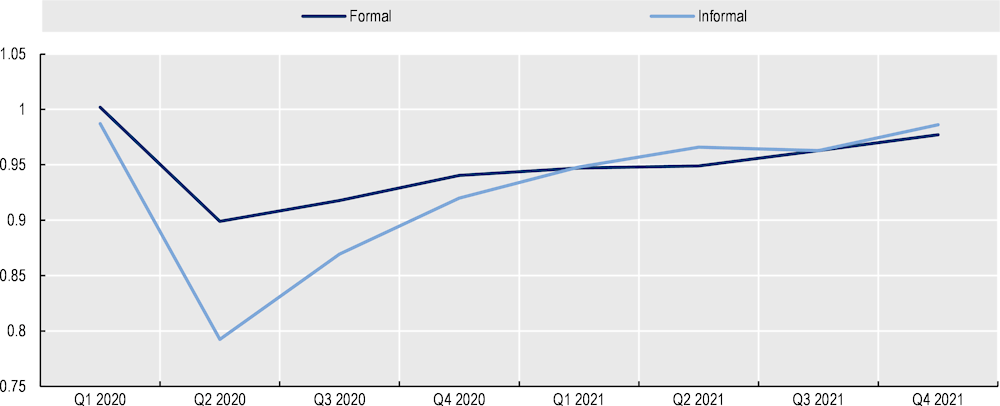

Unlike previous recent economic crises, the COVID‑19-related crisis has been unique in the way it has affected informal employment. For the first time ever, the informal economy did not provide a safety net for formal workers – something that it usually provides in a recession. Around the world, both formal and informal workers lost their jobs and became inactive, losing access to any economic opportunities whatsoever. In many countries, informal workers were more likely than formal workers to lose their jobs and to leave the labour force, for several reasons: widespread informality pervaded sectors heavily affected by lockdown and containment measures; there was limited possibility of telework; terminating informal employment relationships was relatively easy; and there was a higher incidence of informal workers in smaller enterprises, which struggled to survive longer periods of inactivity and had less (or no) access to support measures, including worker retention schemes (ILO, 2020[4]; ILO, 2022[5]). Since the majority of informal workers do not have employment-based social protection or, in the case of independent workers, access to measures aimed at keeping enterprises afloat, these workers and their families were left unprotected.

At the height of the crisis, the number of informal jobs plunged by 20%, about twice the impact for workers in formal employment (Figure 1.3) (ILO, 2020[4]). The decline of informal employment, as a share of total employment, led to a one-off formalisation of the labour market in Q2 2020 in many countries. This, however, was associated with the destruction of informal jobs rather than their formalisation, and a surge in poverty. After the initial losses, informal employment recovered faster than formal employment, especially by Q3 2021. By Q4 2021, the recovery in informal employment had overtaken that of formal employment.

Figure 1.3. Evolution of informal and formal employment (adjusted for population aged 15-64 years)

Note: Estimates based on trends in the number of formal and informal jobs in Argentina, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guyana, Mexico, North Macedonia, Palestinian Authority, Paraguay, Peru, Saint Lucia, South Africa, Uruguay, and Viet Nam. See individual country results in A review of country data. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on informality: Has informal employment increased or decreased? (ILO, 2022[6]). Missing observations are imputed using time-fixed effects in a panel regression of countries without missing observations.

Source: Authors’ computations.

Three transitions underpinned the growth of informal employment in 2021. First, many informal workers returned to their economic activities. Second, new entrants, previously outside the labour force, entered informal employment, often as casual workers, own-account workers or unpaid family workers, to offset losses in household income. Third, the informalisation of previously formal jobs also took place. In the absence of formal employment opportunities, formal wage earners or formal business owners sought any opportunity to earn income, including in the informal economy. This structural deficit of formal job opportunities represents a serious challenge for an inclusive recovery. The prevalence of each of these forces determined the extent of (in)-formalisation of labour markets in different countries.

Globally, the incidence of informal employment is highest for own-account workers, home-based workers, small firms, in agriculture and rural areas

Status in employment has a major bearing on the risk of informality. Globally, own-account workers and workers in non-standard forms of employment are most at risk of informality. Own-account workers and contributing family workers represent 62.7% of informal employment, five times more than among workers in formal employment (12.3%) worldwide. In 2019, 50.0% of part-time and 69.8% of temporary employees were informally employed; the corresponding figure for employees in permanent full-time employment was 15.6%.

There were about 260 million home-based workers in the world in 2019 (ILO, 2021[7]). The percentage of informality among home-based workers ranges from 98% in Southern Asia and the Middle East and North Africa to 63% in Eastern Europe, Southern Europe and Central Asia (Bonnet et al., 2021[8]). During the COVID-19 crisis, homeworking related to teleworking has expanded. In contrast, home-based workers who do not use Internet in their work, including traditional self-employed and industrial outworkers, as well as the contributing family workers who depend on them for work, suffered the greatest loss of work and income (ibid).

In small enterprises, most employment is informal, but the amount of informal employment in large formal enterprises is also significant. Smaller enterprises account for the bulk of total employment globally, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Units with fewer than 10 workers accounted for 55% of total employment globally, and as many as 8 out of 10 workers or more in low- and lower-middle-income countries and in Africa. Nearly 90% of own-account workers operate informally, with informal employment standing at 82.5% in enterprises with between 2 and 5 workers, and at 25.3% in enterprises employing more than 50 workers. As a result of small enterprises’ greater use of informal employment, enterprises with fewer than ten workers account for 76.7% of total informal employment globally and up to 90% or more in low-income countries and in Africa.

Informality has a strong sectoral dimension. The sectors where informal employment rates exceed the global average include agriculture; the domestic work sector; household production for own use; construction; accommodation and food service activities; the wholesale and retail trade; and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles. Informality also stands at 51% among workers in essential occupations and sectors of activity – those that helped economies run amidst the pandemic (ILO, 2023[9]). Strong gender segmentation also figures in informal employment across sectors. The COVID-19 crisis amplified the vulnerabilities of many informal workers because of its strong sectoral dimension. Accommodation and food services were disproportionately affected by lockdowns and travel restrictions (ILO, 2022[10]). Workers in agriculture faced difficulties selling their products in urban markets, despite being considered at lower risk catching and spreading the virus, and playing the role, in some countries, of “last resort” employment (ILO, 2020[11]). The consequences of the war in Ukraine exacerbated the crisis, and agricultural workers were further affected by disruptions in imports of agricultural products and fertilisers, as well as soaring prices.

Finally, informality has a strong rural dimension. Workers in rural areas are almost twice as likely as those in urban areas to be in informal employment: 82% versus 43%. Conversely, 63% of workers in informal employment live in rural areas, whereas 78% of those in formal employment live in urban areas.

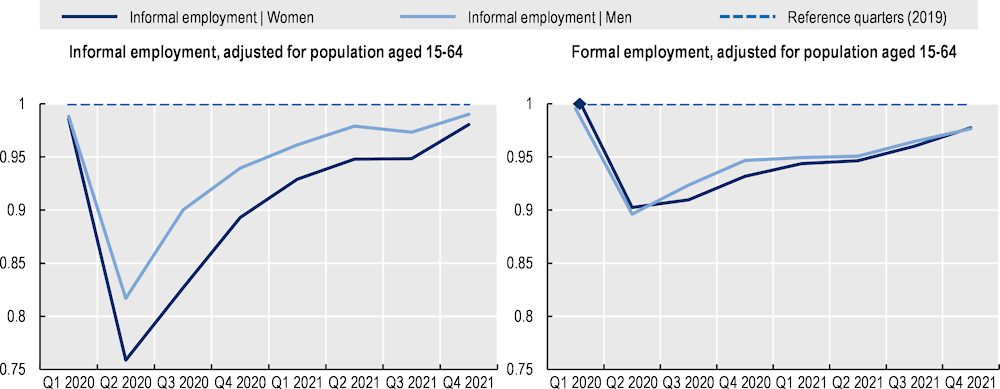

Women and men in informal employment remained unequal in the face of the COVID-19 crisis

Globally, informal employment is a greater source of employment for men, but there are large disparities across countries and occupations. Worldwide, more men (60.2%) than women (55.2%) are employed informally, but this global estimate reflects the weight of major countries, such as the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), where men face greater exposure to informality. The gender difference at the global level also results from structural effects associated with low female labour force participation rates in some countries (as seen in India or Pakistan), which attenuate the effect of their high female informal employment rates in the global and regional estimates.

At the country and regional levels, there are large gender inequalities. In a small majority of countries for which data are available (56%), the share of women in informal employment exceeds that of men. Informal employment is a greater source of employment for women than for men in Central and Western Asia, Southern Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Northern, Southern and Western Europe, and in most low- and lower-middle-income countries. By contrast, the percentage of informally employed men is substantially higher than the percentage of women workers in the Arab States and North Africa, where the female employment-to-population ratio is much lower than the male ratio. In this region, the minority of women employed are overrepresented in the public sector, as well as in occupations and types of enterprises that are more likely to be formal. In most regions, women in informal employment are among the most vulnerable groups in the informal economy.

Informality not only exacerbated workers’ vulnerability to the COVID-19 pandemic shock, but also widened gender employment gaps during the crisis. Women tend to be overrepresented in sectors that were massively hit by the crisis and the lockdown measures, such as food and accommodation, tourism, domestic services, or retail and wholesale, often working informally or with low-status jobs. Moreover, when faced with the decision to leave employment to care for children (during closures of schools) or sick people, many households chose the individuals who earned the least amount of money, usually women. The increase in unpaid care and domestic work and the consequence of lockdowns (need to care for the children out of school) forced many women out of the labour force. This disproportionately affected women working informally, who faced poorer working conditions, the absence of flexible work arrangements, and who, in most cases, did not benefit from social protection or unemployment benefits. As a result, the share of informally employed women declined by 24% in Q2 2020; the corresponding figure for men was 18% (Figure 1.4). Among formally employed workers, however, no such trend emerged; over the same period, formal employment declined by about 10% for both men and women.

Figure 1.4. Evolution of informal and formal employment by sex, 15-64 years

Reference quarters in 2019 =1

Estimates based on trends in the number of formal and informal jobs in Argentina, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guyana, Mexico, North Macedonia, Palestinian Authority, Paraguay, Peru, Saint Lucia, South Africa, Uruguay, and Viet Nam. See individual country results in A review of country data. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on informality: Has informal employment increased or decreased? (ILO, 2022[6]). Missing observations are imputed using time-fixed effects in a panel regression of countries without missing observations.

Source: Authors’ computations.

Youth, older workers and migrants also face greater risks of informality

Globally, there is substantial variation in the level of informal employment over the life course, with youth and older workers disproportionately affected. More than three-quarters of youth and older workers are in informal employment, whereas the comparable figure for those aged 25‑64 years is 55%.

In contrast to native-born populations, migrant workers typically tend to be employed in informal jobs. The average incidence of informal employment is three percentage points higher for the foreign-born population than for the native-born population; it is seven percentage points higher for non-citizens than for workers who are citizens of the country in which they live. In some countries, such as Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, and South Africa, there is a more than ten percentage point difference in the informality rate among foreign-born and native-born populations.

Informal employment as a reflection of the social contract in place

The longstanding structural deficit of low- and middle-income countries in formal job creation, which was worsened by the COVID-19 crisis, as well as the non-inexistent or inadequate protection available to informal workers, remain major sources of vulnerability for those workers and their families. The informal economy is highly heterogeneous (OECD/ILO, 2019[12]). In many settings, it represents a consequence of low level of development, the inability of the economy to create formal quality jobs, and the inability of institutions to deliver and improve people’s lives. In some instances, it can also incorporate elements that distort competition between enterprises and hamper governments’ revenues. Any sustainable development strategy must therefore have formalising the economy and reducing the vulnerability of informal workers at its heart.

Understanding the nature of the social contract, and its links with informality

Informality, its determinants and manifestations, are diverse, complex and context specific, but ultimately informality happens within a given social contract in any society. Social contracts represent an implicit agreement between various actors – citizens, state, workers, enterprises – on how to distribute power and resources in order to achieve common goals such as equity, fairness, freedom, security, and eventually social justice. Social contracts have substantive and procedural dimensions.

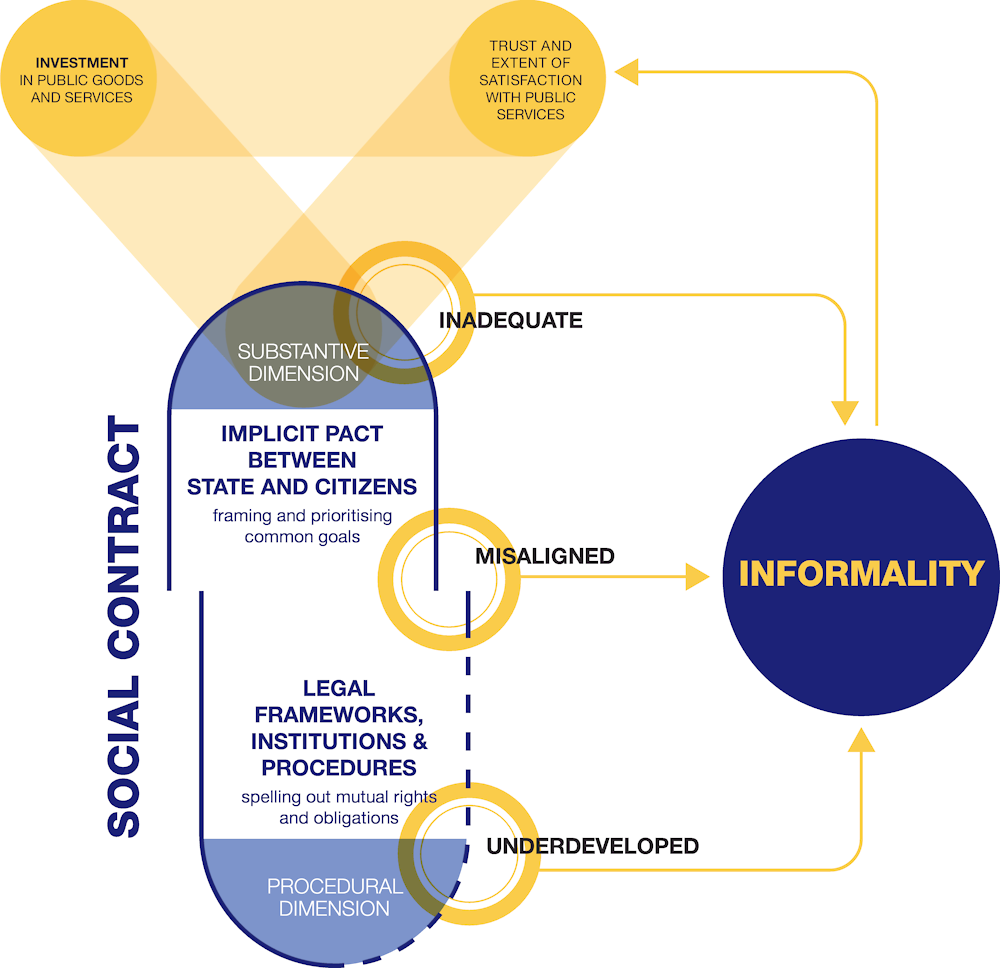

The substantive dimension pertains to the manner in which common goals are framed and prioritised in a society. The procedural dimension pertains to legal frameworks, institutions and procedures that help to make this implicit pact explicit. The question of formality arises only in relation to existing laws and regulations, as well as their implementation in practice. As such, informality can reflect either the underdeveloped procedural dimension of the social contract (when workers and enterprises are not covered by formal legal frameworks or are insufficiently covered), a weak substantive dimension (when states do not deliver sufficient good quality public services, while trust and satisfaction with public services are low), a misalignment between the substantive and the procedural dimensions, or all of these situations at once (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Schematic representation of the linkages between the social contract and informality

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

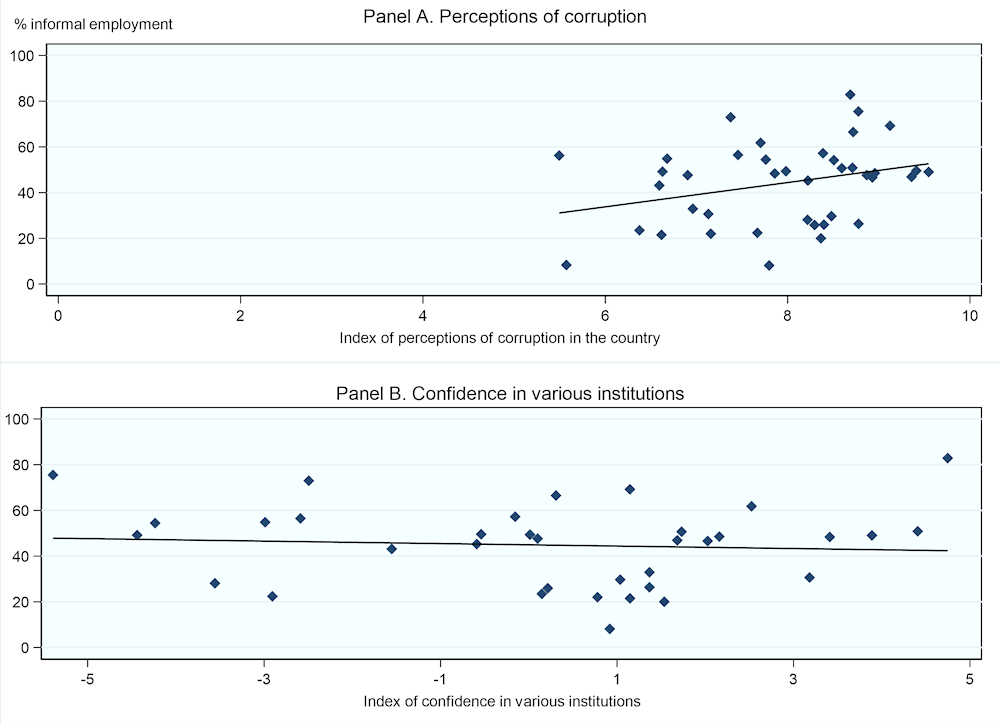

In some settings, informality may be a symptom of a weak substantive dimension of the social contract

The substantive dimension of the social contract is strong when the majority of citizens perceive that the pact with the state is reliable, beneficial for them, and fair (Shafik, 2021[13]). A strong social contract between the state and its citizens is an essential condition for sustaining development over time (OECD, 2011[14]; Bussolo et al., 2018[15]). Conversely, the social contract is weak when most citizens see it as non-reliable, non-beneficial or unfair. The latter perception manifests in low levels of trust and confidence in public institutions. Another key aspect of a strong social contract is the expectation that taxes and social security contributions are not misused. In other words, misuse of public funds and corruption weakens social contracts. In countries where the substantive dimension is weak, as manifested by a high level of corruption, mistrust in public institutions (Figure 1.6), or dissatisfaction with various public services, informality also tends to be ubiquitous.

Figure 1.6. Informality correlates positively with perceptions of corruption and negatively with confidence in institutions

Note: Predicted values of informal employment (International Labour Organization (ILO) definition). Controls include seven geographic regions (East Asia and Pacific; Europe and Central Asia; Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC); Middle East and North Africa (MENA); North America; South Asia; sub-Saharan Africa); gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, purchasing power parity (PPP) constant 2017; income share held by the lowest-income 10% of the population; population growth; trade as a percentage of GDP; the Human Development Index (HDI); ease of doing business as of 2018; and political rights and civil liberties. Index of perceptions of corruption (Panel A) is computed as an average of individual responses to the question: “How much corruption is there in your country?” Answers ranged from 1 to 10, with 1 meaning “There is no corruption in my country” and 10 meaning “There is abundant corruption in my country”. Then, averages were taken by country within a subsample of all workers. Index of the confidence in institutions (Panel B) is first computed on an individual level using the principal component analysis (PCA) procedure, and extracting the first principal component. The PCA is applied to nine questions, asking about the degree of confidence the person has in: armed forces, the press, the labour unions, the police, the justice system, the government, political parties, parliament, and the civil service. The answers are measured on a scale of 1 to 4, where 1 refers to “no confidence at all”, and 4 refers to “full confidence”. Then, averages were taken by country within a subsample of all workers. Informal employment: latest available data. See the annex of Chapter 3 for the full list of countries.

Source: Authors’ computations based on the following data: informal employment: (ILO, 2023[1]), Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Update; geographic regions, GDP per capita, population growth, and trade as a percentage of GDP: (World Bank, 2021[16]), World Development Indicators (database), www.data.worldbank.org/products/wdi; ease of doing business: (World Bank, 2022[17]), Doing Business Indicators (database), www.doingbusiness.org; political rights and civil liberties indices: (Freedom House, 2019[18]), Freedom in the World (database), freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world; perception of corruption and confidence in institutions: own computations based on (World Values Survey, 2020[19]), Wave 7 (database), worldvaluessurvey.org.

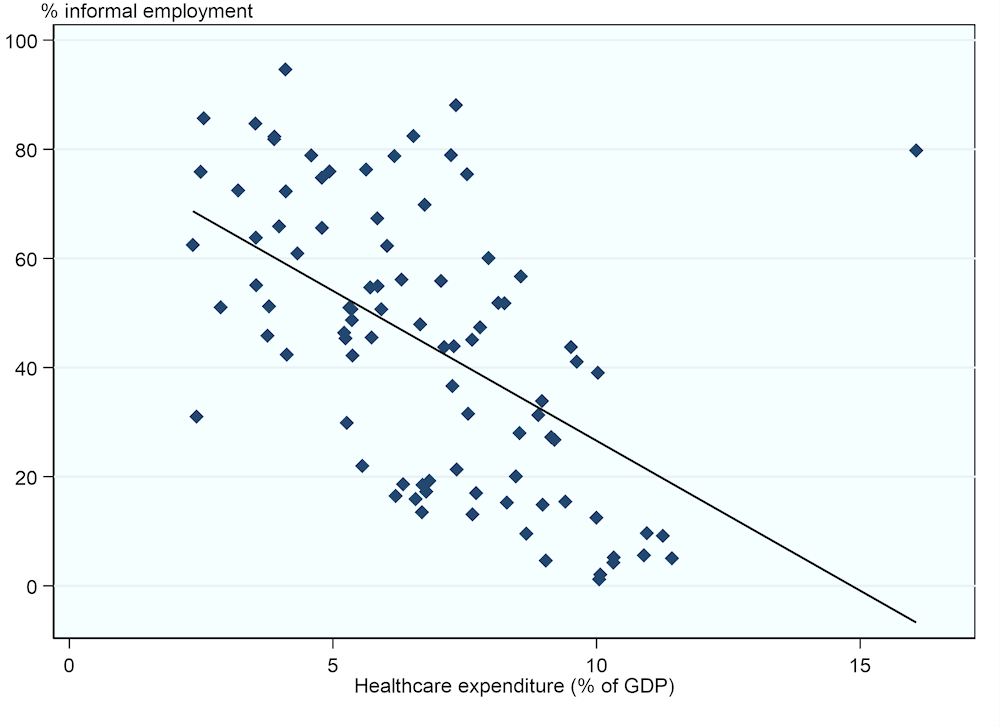

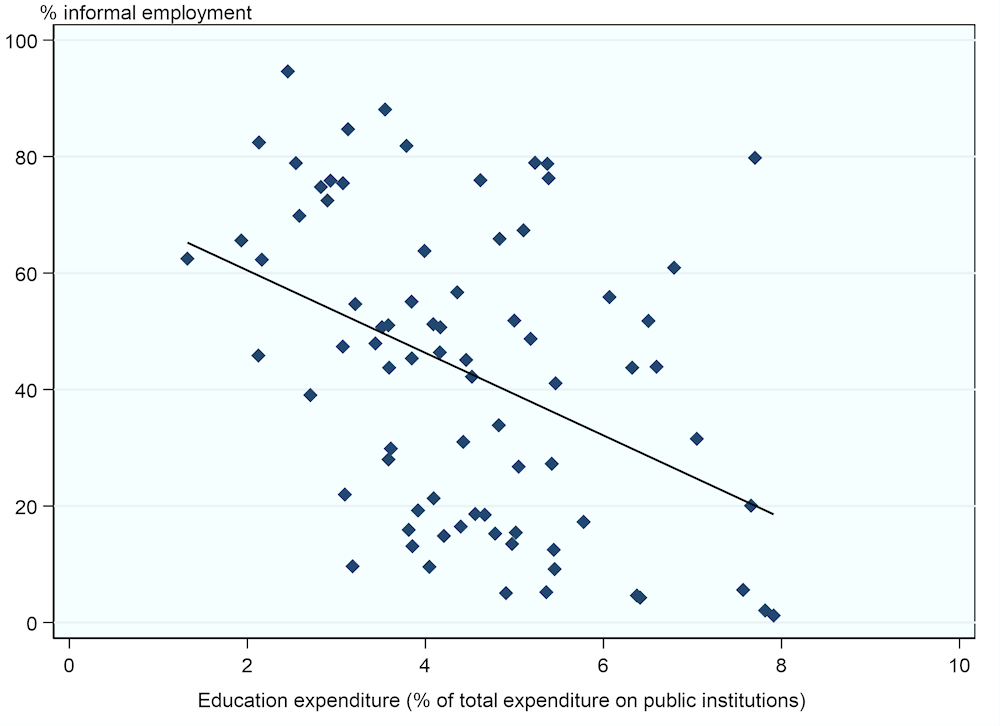

If one of the main components of the social contract is the agreement that citizens comply with laws (including labour and social security laws), pay taxes and make social security contributions, another no less important component is that, in exchange for this, citizens receive good-quality public goods and services, such as education and healthcare. Access to good-quality public goods and services is also one of the key components of redistribution and of promoting equality of opportunity.

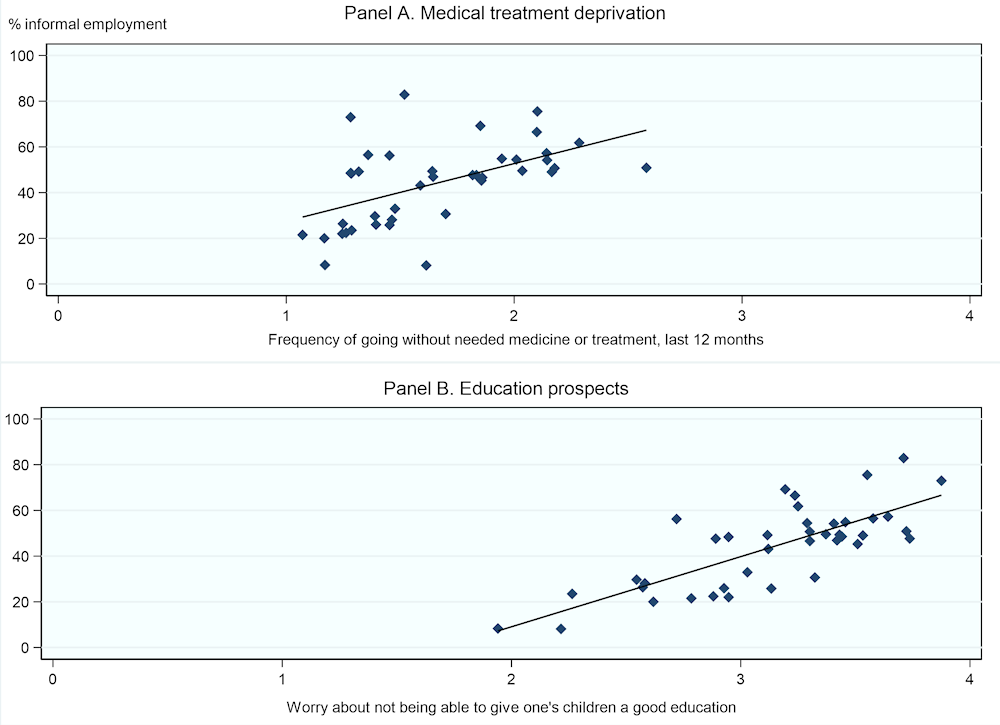

The level of public spending on public goods and services, such as healthcare (Figure 1.7) or education (Figure 1.8) negatively correlates with informality. This translates into poorer social outcomes (Figure 1.9), reinforcing the vulnerability of informal workers and their family members, especially during crises.

Figure 1.7. Informality negatively correlates with higher healthcare expenditure

Note: Predicted rather than actual values of informality are reported. They are obtained from multivariate analysis controlling for seven geographic regions (East Asia and Pacific; Europe and Central Asia; LAC; MENA; North America; South Asia; sub-Saharan Africa); GDP per capita (2017 PPP); life expectancy; population growth; age dependency ratio; 2018 ease of doing business; and trade. Informal employment: latest available data. See the annex of Chapter 3 for the full list of countries.

Source: Authors’ computations based on the following data: informal employment: (ILO, 2023[1]), Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Update/; GDP per capita (2017 PPP), life expectancy, population growth, age dependency ratio, trade, and healthcare expenditure: (World Bank, 2021[16]), World Development Indicators (database), www.data.worldbank.org/products/wdi; ease of doing business: (World Bank, 2022[17]), Doing Business Indicators (database), www.doingbusiness.org.

Figure 1.8. Informality negatively correlates with higher education expenditure

Note: Predicted rather than actual values of informality are reported. They are obtained from multivariate analysis controlling for seven geographic regions (East Asia and Pacific; Europe and Central Asia; LAC; MENA; North America; South Asia; sub-Saharan Africa); GDP per capita (2017 PPP); life expectancy; population growth; age dependency ratio; 2018 ease of doing business; and trade. Informal employment: latest available data. See the annex of Chapter 3 for the full list of countries.

Source: Authors’ computations based on the following data: informal employment: (ILO, 2023[1]) Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Update/; GDP per capita (2017 PPP), life expectancy, population growth, age dependency ratio, trade, and education expenditure: (World Bank, 2021[16]), World Development Indicators (database), www.data.worldbank.org/products/wdi; ease of doing business: (World Bank, 2022[17]), Doing Business Indicators (database), www.doingbusiness.org.

Figure 1.9. Informality positively correlates with adverse social outcomes, either actual or perceived

Note: Predicted values of total informal employment. Controls include seven geographic regions (East Asia and Pacific; Europe and Central Asia; LAC; MENA; North America; South Asia; sub-Saharan Africa); GDP per capita, PPP constant 2017; income share held by the lowest-income 10% of the population; population growth; trade as a percentage of GDP; the HDI; ease of doing business as of 2018; and political rights and civil liberties. In Panel A, frequency of going without necessary medicine or treatment is computed as an average of individual responses to the question: “How often you or your family have gone without needed medicine or treatment in the past 12 months”, with answers measured on a scale of 1 to 4, where 1 means “never” and 4 means “often”. Averages were taken by country within a subsample of all workers. In Panel B, worry about not being able to give one’s children a good education is computed as an average of individual responses to the question: “To what extent do you worry about not being able to give one’s children a good education”, with answers measured on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 means not at all and 4 means very much. Averages were taken by country within a subsample of all workers. See the annex of Chapter 3 for the full list of countries.

Source: Authors’ computations based on the following data: informal employment: (ILO, 2023[1]), Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Update; GDP per capita, PPP constant 2017; income share held by the lowest-income 10% of the population; population growth; trade as a percentage of GDP; the HDI: (World Bank, 2021[16]), World Development Indicators (database), www.data.worldbank.org/products/wdi; ease of doing business: (World Bank, 2022[17]), Doing Business Indicators (database), www.doingbusiness.org; political rights and civil liberties indices: (Freedom House, 2019[18]), Freedom in the World (database), freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world. For frequency of going without necessary medicine or treatment, and worry about not being able to give one’s children a good education: own computations based on (World Values Survey, 2020[19]), Wave 7 (database), worldvaluessurvey.org.

In other settings, informality may be the norm as part of a social contract that has only a recent or an underdeveloped procedural dimension

In some of the least developed countries, the logic for informal employment in relation to the social contract is profoundly different when these countries are compared with richer and more developed countries. In many instances, the procedural dimension of the social contract, which takes the form of legal arrangements and frameworks, is not yet developed enough to cater to all citizens or to be relevant to all of them, especially where castes or tribal traditions remain strong. It may not cover some specific sectors (such as agriculture or waste picking) or some specific workers (such as traditional farmers, fishers, indigenous communities, or domestic workers). When legal frameworks exist, governments do not always have the capacity to enforce them. Governments may also lack the infrastructure and the capacity to deliver the benefits of adherence to the social contract (such as education and health infrastructure), or the qualified specialists to deliver the services.

In some settings, informality also persists because there is a misalignment between the procedural dimension (formal institutions) and the substantive norms of the society, as well as between institutional responses to the true needs of workers, their families, and citizens generally (Gërxhani, 2004[20]; Williams and Horodnic, 2015[21]). This misalignment may be historic, reflecting colonial legacies. It may also reflect the fact that the state is not catching up with the challenges that the ever-changing world is presenting – as is the case in countries undergoing substantial socio-economic and political transformation. This misalignment further justifies the existence of the informal economy, and legitimises informal practices in the eyes of the community, even if they are not seen as legitimate in relation to the state (Van Schendel and Abraham, 2005[22]).

Improving resilience to crises requires strengthening the social contract. This presupposes continuous efforts to render the procedural dimension of social contracts more relevant for all workers, in order to ensure that the substantive dimension is strong, inclusive and fair for informal workers, and also to ensure that the procedural dimension reflects well the substantive dimension of the social contract.

Globalisation, the social contract and informality

Social contracts differ across countries and change over time. National economic, social, and political changes present both opportunities and challenges to the strength of the social contract and ultimately affect social cohesion. In addition, international factors may also alter the substantive dimension of the social contract in a given country and render the procedural dimension inadequate to the fast-changing realities. Already prior to 2020, social contracts around the world were being challenged by a variety of internal and international factors, including demographic shifts, climate change, rising inequality, increased income insecurity, lower social mobility, economic globalisation, digitalisation and fragile or weakening social dialogue and decline in trust in institutions. In all countries, regardless of their level of development, governments should remain vigilant against the erosion of the social contract, and use it as a lens through which to address informality.

Trade liberalisation has challenged the social contract in many countries

Economic globalisation can be a powerful determinant of economic growth, enhanced productivity and efficiency. However, economic globalisation can also destabilise existing equilibria of power relations between different economic actors within a given country, and with them, the existing social contract. For much of the developing world, integration into the global economy created significant challenges in terms of employment adjustment. The impact on formal job creation has often been ambiguous and is not uniform across countries. If a greater degree of globalisation has been associated with lower levels of informal employment in upper-middle-income and high-income countries, it is not the case in lower-middle-income and low-income countries.

International trade is an aspect of economic globalisation that has an asymmetrical impact on informality, so that the aggregate impact remains ambiguous. Trade liberalisation induced by the reduction of export tariffs, and hence the expansion of export opportunities, has led to a decrease in the informal employment share in the affected sectors and regions. In contrast, trade liberalisation induced by the reduction of import tariffs, and hence the expansion of imports, has tended to increase the share of informal employment in the affected sectors and regions. These effects have been pronounced in sectors, industries, and regions most affected by trade liberalisation.

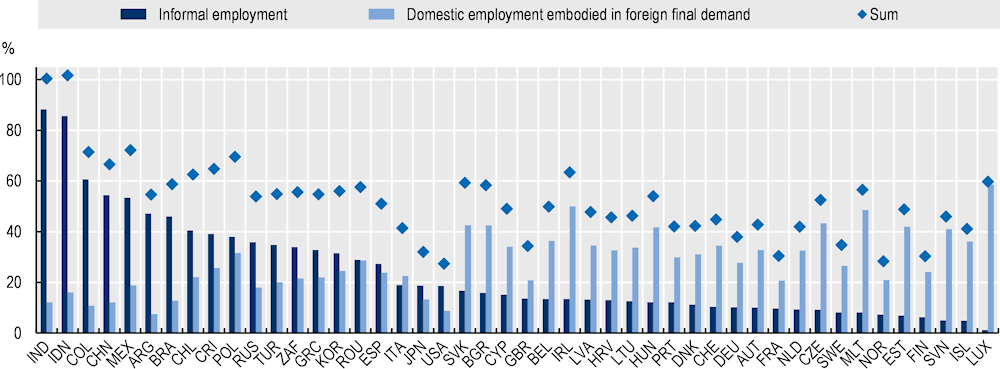

GVCs can be an important source of informal employment

By 2020, up to 70% of international trade was organised through GVCs (OECD, 2020[23]). Among countries with available data, the risk of the informality footprint is highest in GVCs originating from India and Indonesia. In these countries, the sum of the percentage of informal employment and of the percentage of domestic employment embodied in foreign final demand is greater than 100%, which means that at least some of the GVC-related employment is definitely informal. The greater the sum, the higher the probability that at least some GVC-related employment is informal, which means that in some countries one cannot rule out that informal employment and GVCs are related (Figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10. Informal and GVC-related employment, by country

Note: Both informal and domestic employment embodied in foreign final demand are expressed as a share of total employment. If the sum of these indicators is greater than 100%, one can interpret these results as evidence of overlap between informal employment and trade-linked employment.

Source: Authors’ computations based on the following data: informal employment: ILO (2018[3]), www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_626831/lang--en/index.htm; domestic employment embodied in foreign final demand (%): OECD (2019[24]), Trade in employment (TiM): Principal indicators (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIM_2019_MAIN.

The informality footprint of GVCs depends on how they are organised and managed

GVCs have the potential to create opportunities for both higher productivity and better quality of employment, including for women and young workers. The extent to which this is actually happening depends on many factors. First, the type of linkages matters: the expansion of forward linkages in a chain can decrease informal employment, whereas the expansion of backward linkages does not necessarily have this effect. Second, the way production is organised is also important: if the lead firms prefer outsourcing over direct ownership of overseas subsidiaries, this can increase the risk of informality in the lowest tiers of supply chains (Abramovsky and Griffith, 2006[25]; ILO, 2016[26]). Third, purchasing practices, and in particular inappropriate lobbying, poor forecasting, and excessive sampling substantially increase the risk of employing workers informally. Finally, possibilities of upgrading, and especially of process upgrading, within a GVC, can help formalisation and improve the working conditions of both formal and informal workers.

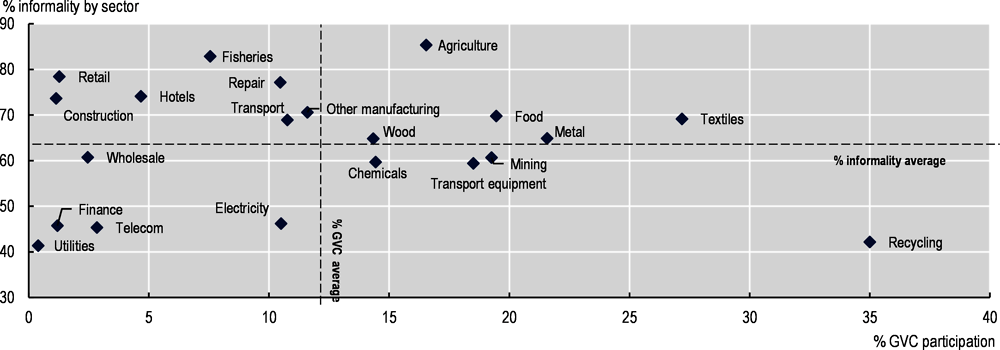

In terms of sectors, GVCs in agriculture and in garments have some of the largest informal employment footprints

The size of a GVC’s informal employment footprint appears to be largely sector specific but not necessarily linked to the level of GVC participation in a given sector. Analysing the association between the level of GVC participation and the percentage of informal employment (Figure 1.11) enables us to identify four types four types of sectors: (i) sectors with higher-than-average informality and GVC participation (such as agriculture, food and beverages, textiles, wood, and metals); (ii) sectors with lower-than-average informality and GVC participation (utilities, electricity, and certain higher-added value services such as finance, telecommunications; (iii) sectors with higher-than-average informality but lower-than-average GVC participation (i.e. fishing, lower-added value service sectors such as retail, hotels, repair, construction, transportation, and other manufacturing); and (iv) sectors with lower-than-average informality but higher-than-average GVC participation (chemicals, transportation equipment, mining, and recycling).

GVCs in agriculture have some of the largest informal employment footprints due to a combination of factors such as the pervasive informality in the first segment of the chain, the production structure in agriculture; and the way GVCs are organised in agriculture (often outsourcing without direct ownership). Informal employment is also ubiquitous in some sectors of the textiles industry, such as garments, with the largest shares of informal employment found among home-based workers in the downstream tiers.

Figure 1.11. Total GVC participation and informality, by sector

Note: GVC participation is defined as exported value added which crosses at least two borders. Here, GVC participation is expressed as a percentage of value added. Country coverage: Argentina (2018), Armenia (2016), Brazil (2018), Burkina Faso (2014), Chile (2017), Colombia (2018), El Salvador (2018), Gambia (2015), Ghana (2013), Liberia (2016), Madagascar (2012), Malawi (2016), Mali (2012), Mexico (2018), Namibia (2015), Nicaragua (2014), Niger (2014), Peru (2019), Senegal (2011), Tanzania (2014), Thailand (2017), Uganda (2015), Uruguay (2018), Viet Nam (2016) and Zambia (2015).

Source: Authors’ computations based on the following data: For the percentage of informal employment at the sector level: OECD (2021[27]), Key Indicators of Informality based on Individuals and their Household (KIIbIH), https://www.oecd.org/dev/Key-Indicators-Informality-Individuals-Household-KIIbIH.htm. For GVC indicators: Belotti, Borin and Mancini (2020[28]) based on Eora26 data.

Informality and digital labour platforms: An opportunity yet to be seized

Work through digital labour platforms: A new challenge for social contracts

Digital labour platforms that mediate work provide new ways of organising production and work (OECD, 2019[29]; OECD, 2019[30]; ILO, 2021[31]). As such, they also present a challenge to employers, workers, and governments by disrupting traditional ways of doing business and altering competition, worker protection, and informal employment (ILO, 2022[32]). The typology of digital labour platforms includes (ILO, 2021[31]; ILO, 2022[32]):

online web-based platforms for online delivery of non-material services by a workforce that is potentially scattered around the world

location-based platforms for serving clients locally in a specific area.

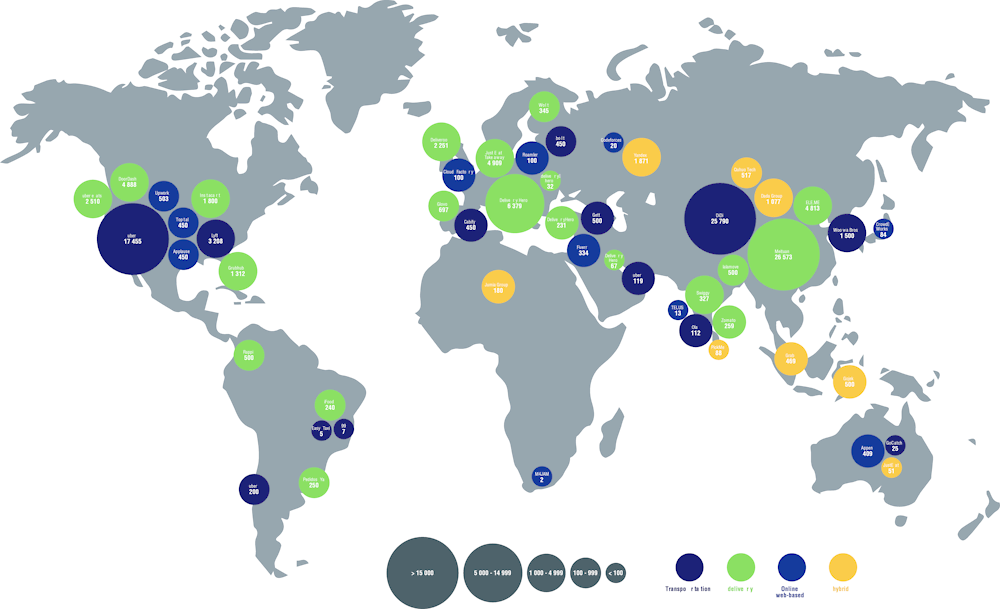

Work through digital labour platforms grew since the early 2000s, penetrating all geographic regions (Figure 1.12).

Figure 1.12. Estimated annual revenue of digital labour platforms, selected categories, by region, 2021 (in USD millions)

Note: For details of construction, please refer to (ILO, 2021[31]).

Source: (ILO, 2021[31]), based on Crunchbase database; courtesy of the ILO, with authors’ adaptation.

The COVID-19 crisis further popularised the use of digital labour platforms

The COVID-19 pandemic further generalised the use of digital labour platforms, although at various stages of the pandemic sizeable variations were observed by sector of economic activity and by country (OECD, 2021[33]; ILO, 2022[32]). In many sectors, digital labour platform workers had high exposure to the COVID‑19 virus and also experienced work and income loss due to lockdown measures and changing consumer behaviour (OECD, 2020[34]). Most of these workers were not covered by social protection, including health insurance, work-related injury, disability and unemployment insurance. The majority of them could not afford either to self-isolate or to take days off in the absence of paid sick leave and sickness benefits – even if they tested positive for COVID‑19 (ILO, 2021[31]). This presented major risks not only to workers but also to their clients.

The share of informal employment is often higher among workers on digital labour platforms than among workers in the traditional offline economy (Aleksynska, Bastrakova and Kharchenko, 2018[35]; Berg, 2016[36]). This is because the vast majority of digital labour platform workers are classified as independent contractors, or self-employed (Berg et al., 2018[37]; ILO, 2021[31]; Schwellnus et al., 2019[38]) who often remain unregistered. Even for those self-employed workers who are registered, and hence de jure part of the formal sector, there is a risk of sliding into dependent self-employment, and even into a disguised employment relationship – a situation where the worker is misclassified as an independent, self-employed worker, even though they are, in fact, in a subordinate employment relationship (ILO, 2016[39]).

However, work channelled through digital labour platforms could also be an opportunity for formalisation (OECD, 2019[30]). Available technologies for digital work record workers’ and clients’ identities through digital accounts and track the transactions, allowing for monitoring of economic activity, traceability, transparency and accountability (ILO, 2022[5]), all of which are important elements for formalisation. In order for those technologies to support formalisation effectively, governments need to create more enabling environments, and digital labour platforms and public authorities must co-operate more closely.

Digital labour platforms could create opportunities for formal jobs, but this has yet to happen

Thus far, formal job creation by digital labour platforms remains limited and sector specific. On the one hand, digital labour platforms allowed to monetise tasks that previously would not have been carried out for money, and to outsource them to developing countries. This has led to an increase in demand, and consequently in supply of work, in sectors such as creative and multimedia services or software development (OECD, 2018[40]; Schwellnus et al., 2019[38]). Platforms also make it easier for parties to find each other and to match demand with supply. By doing this, they lower the transaction costs of finding labour and they minimise frictions in labour markets (McKinsey Global Institute, 2015[41]), which can increase total employment. On the other hand, the bulk of the work channelled through digital labour platforms today – whether taxi driving, domestic work, cleaning or auditing services – existed prior to the emergence of digital labour platforms, and they often co-exist today in traditional labour markets. Rather than creating new jobs, platforms use technologies to mediate work, help outsource services, and change the nature of existing jobs (ILO, 2016[39]; Schwellnus et al., 2019[38]). Digital labour platforms also allow to more easily substitute wage employment by services delivered by self-employed workers. As a result, the total new job creation effect is unclear. The newly created jobs are not always formal, and some formal wage jobs in the traditional economy are converted into informal self-employed jobs on digital labour platforms.

But it does not have to be this way. For example, for domestic workers, platforms can act as temporary agency platforms that favour formalisation. In some national legislation (for example, in China), access to social security is conditional on whether the person is employed by an enterprise. In this case, being employed by a temporary agency, including temporary agency platforms, is the only way domestic workers can access formal wage jobs. In addition, platforms themselves can play a role in helping to formalise their workers; for example, by enrolling workers into public insurance programmes. As such, platforms have the potential to serve as a bridge towards formalisation (OECD, 2019[30]).

Policy recommendations to reinvigorate social contracts

As the social contract approach reveals, reducing informality and the vulnerability of informal workers and their household members requires more than boosting economic growth or developing one-off policy responses. A comprehensive effort to reinvigorate social contracts is key to addressing the challenges posed by globalisation and rapid technological change, thus rendering societies more resilient to current and future crises, and supporting formalisation. It requires actions on many fronts and from a wide range of stakeholders.

The role of governments

The role of governments is paramount in ensuring that the substantive dimension of the social contract is strong, inclusive and fair for all workers, including informal workers; in rendering the procedural dimension of social contracts relevant for all workers; in improving the alignment between the substantive and the procedural dimensions; and in staying vigilant against a possible weakening of social contracts under the effect of external pressures.

1. Enhancing the procedural dimension means expanding coverage of formal legal frameworks and social protection, ensuring sufficient levels of protections, and improving compliance with formal arrangements by making legal frameworks relevant and fair to informal workers.

2. Strengthening the substantive dimension requires improving access to and quality of those public services that are most valued by all workers, including informal workers, such as healthcare, education and skill development, but also fighting corruption, strengthening trustworthiness of the judiciary system and the police, and improving how government performs its duties.

3. Strengthening the social contract in an open economy requires additional efforts to create enabling environments for the development of formal employment through a range of co‑ordinated policies to support innovation, formal enterprise and formal job creation, access to credit, labour mobility, and increasing employability. To alleviate the consequences of labour reallocation, trade liberalisation policies should be accompanied by policies on vocational training for adult learners (including special provisions for women and migrant workers); lifelong learning that targets skill changes arising from globalisation; the anticipation of skill changes in a country’s changing production structure; and skill recognition policies. To ensure that global competition does not scrimp labour protection, effective labour inspection and enforcement of current regulations is necessary.

4. Accompanying GVC development with the view of alleviating informality can be done with the following non-exhaustive measures:

promoting the use of written rather than oral contracts by foreign enterprises and their local suppliers

developing policies to regulate sub-contracting and ensure fair treatment of locally employed workers, including dependent contractors

raising awareness among businesses about the existence of OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, as well as OECD due diligence recommendations in specific sectors and supply chains, including minerals, agriculture, garments and footwear, extractives, and finance; and working with businesses to ensure that they see value in adhering to the principles prescribed therein. To the extent possible, integrating these frameworks into national binding regulations

5. Responding to new developments in the world of work, such as work through digital labour platforms, requires actions to reinforce both substantive and procedural dimensions of the social contract. In this context, new developments can also be seen as an opportunity to strengthen social contracts and grasp the possibilities for formalisation. Specific tools to tackle informality and reduce the vulnerabilities of informal digital labour platform workers include (Lane, 2020[42]; ILO, 2016[39]; OECD, 2019[30]):

bringing digital labour platform work within the scope of the existing regulations

encouraging the formalisation of self-employment and ensuring that digital labour platforms are paying their share of taxes and social security contributions

strengthening and enforcing regulations to correctly categorise workers as employees

empowering workers to challenge their employment status

modernising laws to address the digital labour platform modes of work

leveraging technologies to formalise workers

including digital labour platform workers in the existing social protection schemes

supporting the universal right of all workers to bargain collectively

encouraging platforms to exercise social responsibility.

The role of a whole range of other actors

In an open economy, in order to create social contracts that are inclusive, adequate and regarded as fair by all actors in society, it is critically important to ensure that the voices of all these actors can be heard. A robust commitment for this is required not only from governments but also from a wide range of other actors, including employers, managers in multinational enterprises, consumers, and civil society.

Strengthening the voice and bargaining power of informal workers and informal workers’ organisations remains one of the key determinants of making progress towards addressing informality. This is especially relevant for workers in the lower tiers of supply chains; in sectors with particularly high levels of informality; and workers channelling their work through digital labour platforms. These workers are significantly more knowledgeable about their needs than anyone else. A strong social contract is one that recognises these workers and enables them to participate in the formulation of policies that concern them, as well as into the design and oversight of enforcement mechanisms.

Multinational enterprises should be encouraged to engage in improving their responsible business conduct in order to promote formal employment in subsidiaries and among suppliers. Multinationals’ suppliers’ compliance with international and local laws and regulations, the implementation of good practices when contracting people to carry out work outsourced from the multinationals' home countries, and having responsible business conduct embedded within business decisions, operations, and supply chains are key in this respect. The purchasing practices of some enterprises are identified as one of the factors in the potential rise of informal employment. Raising awareness of this, and taking steps to modify purchasing practices in order to improve forecasting can be a viable tool to reduce informality. The lead firms should strive to ensure that the suppliers and sub-contractors disclose the details of sub-contracting arrangements, honour existing contracts, use written contracts, and comply with national labour and social security regulations.

Consumer awareness regarding working conditions at the very bottom of the value chain, as well as on digital labour platforms, can help to create the necessary momentum for changing demand, improving working conditions and increasing formalisation.

Civil society can also play an important role, for example in process traceability within the GVC. If civil society has the space and opportunity to engage with multinational enterprises and local governments, and be heard, it can help with process upgrading which includes formalisation.

References

[25] Abramovsky, L. and R. Griffith (2006), “Outsourcing and Offshoring of Business Services: How Important is Ict?”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 4/2-3, pp. 594-601, https://doi.org/10.1162/jeea.2006.4.2-3.594.

[35] Aleksynska, M., A. Bastrakova and N. Kharchenko (2018), Work on Digital Labour Platforms in Ukraine: Issues and Policy Perspectives, ILO, Geneva.

[28] Belotti, F., A. Borin and M. Mancini (2020), “Icio: Economic Analysis with Inter-Country Input-Output Tables in Stata”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-9156.

[36] Berg, J. (2016), “Income security in the on-demand economy: Findings and policy lessons from a survey of crowdworkers”, Conditions of Work and Employment Series, No. 74, ILO, Geneva, http://www.ilo.org/publns (accessed on 12 May 2022).

[37] Berg, J. et al. (2018), Digital labour platforms and the future of work: Towards decent work in the online world, ILO, Geneva.

[8] Bonnet, F. et al. (2021), Home-based workers in the world: A statistical profile, WIEGO Statistical Brief No. 27, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_771793.pdf.

[15] Bussolo, M. et al. (2018), Towards a New Social Contract. Taking On Distributional Tensions in Europe and Central Asia, Washington D.C., World Bank.

[18] Freedom House (2019), Freedom in the World, http://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world.

[20] Gërxhani, K. (2004), “Tax evasion in transition: Outcome of an institutional clash? Testing Feige’s conjecture in Albania”, European Economic Review, Vol. 48/4, pp. 729-745, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2003.08.014.

[9] ILO (2023), The value of essential work. World Employment and Social Outlook, ILO, Geneva.

[1] ILO (2023), Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Update, ILO, Geneva.

[6] ILO (2022), A review of country data. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on informality: Has informal employment increased or decreased?, International Labour Office, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/employment-promotion/informal-economy/publications/WCMS_840067/lang–en/index.htm.

[32] ILO (2022), Decent Work in the Platform Economy. Reference Document for the Meeting of Experts on Decent Work in the Platform Economy, ILO, Geneva.

[5] ILO (2022), ILO Monitor on the world of work. 9th edition, International Labour Office, Geneva.

[10] ILO (2022), The future of work in the tourism sector: Sustainable and safe recovery and decent work in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Report for the Technical Meeting on COVID-19 and Sustainable Recovery in the Tourism Sector.

[31] ILO (2021), 2021 World Employment and Social Outlook 2021: The Role of Digital Labour Platforms in Transforming the World of Work, International Labour Organization: Geneva, http://www.ilo.org/publns. (accessed on 9 May 2022).

[7] ILO (2021), Working from home: From invisibility to decent work, ILO, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_765806/lang--en/index.htm.

[11] ILO (2020), ILO Monitor on the world of work. 3rd edition, International Labour Office, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_743146/lang–en/index.htm.

[4] ILO (2020), ILO Monitor on the world of work. 4th edition, International Labour Office, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_745963/lang–en/index.htm.

[3] ILO (2018), Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture (third edition), ILO, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_626831/lang--en/index.htm.

[26] ILO (2016), Decent Work in Global Supply Chains. ILC 105th Session Report IV., ILO, Geneva.

[39] ILO (2016), Non-standard employment around the world: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects, International Labour Office, Geneva, http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_534326/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[2] ILO (2003), Guidelines concerning a statistical definition of informal employment, ILO Seventeenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians, Geneva.

[42] Lane, M. (2020), “Regulating platform work in the digital age”, Going Digital Toolkit Policy Note, Vol. 1.

[41] McKinsey Global Institute (2015), A Labour Market that Works. Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age.

[27] OECD (2021), Key Indicators of Informality based on Individuals and their Household (KIIbIH) - OECD, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dev/Key-Indicators-Informality-Individuals-Household-KIIbIH.htm (accessed on 29 October 2021).

[33] OECD (2021), “The role of online platforms in weathering the COVID-19 shock. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)”, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-role-of-online-platforms-in-weathering-the-covid-19-shock-2a3b8434/.

[23] OECD (2020), Trade Policy Implications of Global Value Chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/trade_policy_implications_of_global (accessed on 16 December 2021).

[34] OECD (2020), What have platforms done to protect workers during the coronavirus (COVID 19) crisis?, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/what-have-platforms-done-to-protect-workers-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-crisis-9d1c7aa2/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

[29] OECD (2019), An Introduction to Online Platforms and Their Role in the Digital Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/53e5f593-en.

[30] OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en.

[24] OECD (2019), Trade in employment (TiM): Principal indicators, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIM_2019_MAIN (accessed on 2 February 2022).

[40] OECD (2018), Online work in OECD countries. Policy Brief on the Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[14] OECD (2011), Perspectives on Global Development 2012: Social Cohesion in a Shifting World, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/persp_glob_dev-2012-en.

[12] OECD/ILO (2019), Tackling Vulnerability in the Informal Economy, Development Centre Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/939b7bcd-en.

[38] Schwellnus, C. et al. (2019), “Gig economy platforms: Boon or Bane?”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1550, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fdb0570b-en.

[13] Shafik, M. (2021), “What Is the Social Contract?”, in What We Owe Each Other, Princeton University Press, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv17nmzkg.5.

[22] Van Schendel, W. and I. Abraham (2005), States, Borders, and the Other Side of Globalization, http://iupress.indiana.edu (accessed on 2 July 2021).

[21] Williams, C. and I. Horodnic (2015), “Evaluating the prevalence of the undeclared economy in Central and Eastern Europe: An institutional asymmetry perspective”, European Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 21/4, pp. 389-406, https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831x14568835.

[17] World Bank (2022), Doing Business Indicators (database), http://www.doingbusiness.org.

[16] World Bank (2021), World Development Indicators (WDI), World Bank, Washington, DC, http://data.worldbank.org/products/wdi (accessed on 28 October 2021).

[19] World Values Survey (2020), Wave 7 (database), http://worldvaluessurvey.org.