This chapter presents the framework used in the report to analyse the extent to which policies in Japan are supportive of innovation and structural change, and the extent to which they affect access to, and use of, natural resources for productivity growth and sustainability. It also gives an overview of the review’s findings on a wide range of policies and develops specific recommendations for related policy areas.

Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Japan

Chapter 1. Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

1.1. Enhancing innovation, productivity and sustainability is a key challenge in the food and agriculture sector globally and in Japan

Agriculture productivity growth must be improved in order to address the global challenge of growing demand for food, feed, fuel and fibre. Furthermore, this must be done sustainably through more efficient use of natural and human resources, and reduced pollution. A wide range of economy-wide policies affect the performance of the food and agriculture sector, and must be considered alongside agriculture-specific policies. This report focuses on the performance of agricultural innovation systems in Japan, recognising the importance of innovation in improving productivity growth sustainably along the whole agro-food chain.

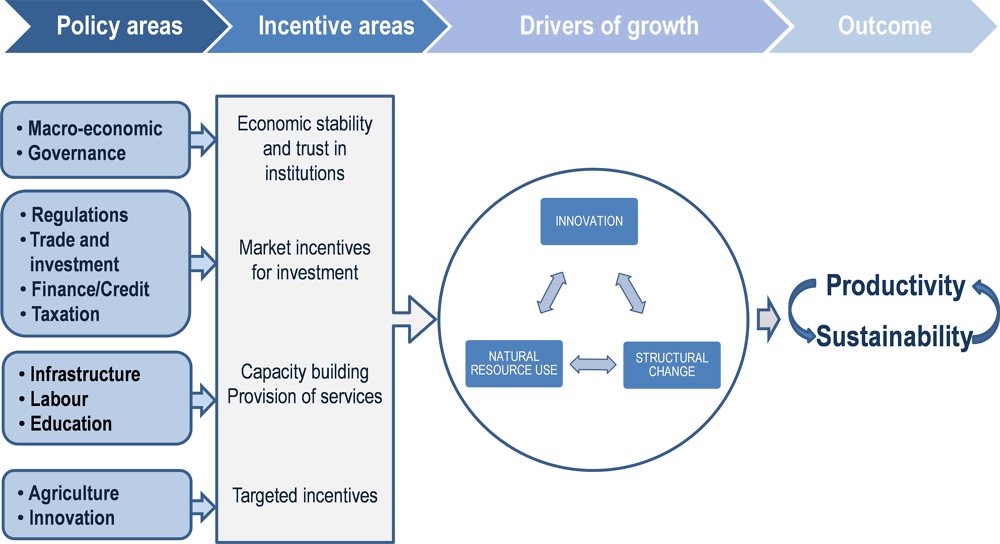

The framework of this report considers policy incentives and disincentives to key drivers of sustainable productivity growth: innovation, structural change, and the environmental sustainability of agriculture (Figure 1.1).

This report begins with an overview of the characteristics and performance of the food and agriculture sector, and the challenges it will face in the future (Chapter 2). It then considers a broad spectrum of policies according to the main channels or incentive areas through which they affect productivity growth and sustainable use of resources:

the general policy environment for food and agriculture (Chapter 3)

the agricultural policy environment (Chapter 4)

the agricultural innovation system (Chapter 5)

human capital development in agriculture (Chapter 6).

The report draws on background information provided by experts, and on recent OECD agricultural, economic, rural, environmental, and innovation policy reviews. Throughout, it discusses the likely impacts of each policy area on innovation, productivity growth and sustainability, and draws recommendations from a range of policy areas.

Figure 1.1. Policy drivers of innovation, productivity and sustainability in the food and agriculture sector

Source: (OECD, 2015[1]), “Analysing policies to improve agricultural productivity growth, sustainably: Draft framework”, www.oecd.org/agriculture/policies/innovation.

1.2. Japan’s agriculture is at a turning point

After three decades of contraction, Japan’s agriculture show some signs of growth

Since 1990, the value of agricultural production has declined by more than 25%, and commercial farm households and agricultural workers by more than 50%. In 2017, the share of agriculture in the Japanese economy was 1.1% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 3.4% of employment.

Japan is the second largest net importer of agro-food products after the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”). Despite policy efforts to maintain food self-sufficiency, more than 60% of calorie intake in Japan depends on imports. Trade flows show that the country does not have a comparative advantage in agriculture and food products. However, rapid economic growth in East Asia has boosted demand for Japanese agro-food products, with exports doubling between 2012 and 2018 (albeit from a small base), opening new market opportunities. The value of agricultural production increased three consecutive years after 2015 and the number of young new entrants to agriculture is increasing.

Structural change has driven agricultural productivity growth in Japan

The higher share of agriculture in employment than in GDP indicates that labour productivity in agriculture is lower than in the rest of the economy. The food and agriculture sector continued to be under pressure to raise its productivity in order to keep up with the highly competitive manufacturing sector, as well as improve its international competitiveness and its contribution to the economy, including in rural areas.

A reallocation of resources to more profitable sectors and to more productive large-scale farms has been a major driver of productivity growth in Japan’s agriculture. The value share of rice in agricultural production declined from 43% in 1965 to 17% in 2015, while that of livestock and vegetables increased to 35% and 27% in 2015 from 23% and 12% in 1965, respectively. Westernisation of the Japanese diet reduced rice consumption by more than half from its peak, and increased meat and dairy consumption.

The concentration of land into large, professional farms has accelerated in the last two decades as older farmers have retired and policies that support land rental have been reinforced. As a result, agricultural production is structurally polarised with a small number of large, commercial farms accounting for the bulk of production, while many small farms remain, notably in the rice sector. Management of farms has also shifted from the traditional family farm to corporate farms that hire regular employees. The number of corporate farms doubled between 2005 and 2015, accounting for more than a quarter of agricultural production. In 2015, 3% of farms produced more than JPY 30 million (USD 278 000), accounting for more than half of total production. The economic-size distribution of farms indicates that the farm structure in Japan has evolved in a way similar to that of European Union countries prior to 1 May 2004 (EU15).

Sustainability performance of agriculture has significant room for improvement

Despite the declining share of primary agriculture in the economy, it is important to minimise the environmental impact of agriculture on natural resources as the sector comprises 36% of the country’s total habitable land area and 68% of total water withdrawal. Given the limited availability of land, Japan’s agricultural production sites and residential areas tend to be closely located. Improving the environmental performance of agriculture should be considered a local issue affecting the lives of local residents.

There is significant room to improve the environmental performance of Japanese agriculture. Japan has one of the highest nutrient surpluses among OECD countries, indicating the potentially high risk of environmental pressure on soil, water, and air. While many OECD countries have reduced agricultural nutrient surpluses, Japan’s progress in this area has been much slower. For example, the nitrogen balance in Japan decreased by only 0.3% between 1993-95 and 2013-15, while it fell by 35% in the EU15 and by 24% in the OECD area – in both cases from lower initial levels.

Future growth in agriculture in Japan can no longer depend on the intensive use of inputs and natural resources. More frequent extreme weather events combined with natural disasters will likely pose a major risk to future agricultural production. Promoting the sustainable use of land and water, and increasing the country’s preparedness for climate change are critical to ensuring long-term growth. Promoting environmentally-friendly farming can also add higher value to agro-food products that are in strong demand by consumers in Japan and abroad.

Demographic trends pose one of the biggest challenges

The contraction of the Japanese population and labour force is a major challenge for the economy, and one which increasingly affects food and agriculture. Total population peaked in 2008 and is expected to decline by 31% by 2065. The working age population started to decline in 1995 and is expected to decline by a further 41% over the next four decades. The ageing population is of particular concern. The share of the population more than 65 years old will rise from around 27% in 2016 to almost 40% in 2055, the highest in the OECD area.

A smaller domestic market and a declining labour force will have significant implications for Japan’s economy. A shortage of labour in agriculture has already severely constrained many agricultural operations. Moreover, a declining and ageing population will reduce the size of the domestic food market in the medium- to long-term. The future growth of the agriculture and food sector thus depends on increasing productivity by using less human and natural resources, and producing high-value-added products for the domestic and overseas markets.

Policymakers face new policy challenges

Past policy efforts have focused on structural change, in particular on the concentration of land use. The productivity of the sector improved mainly through resource reallocation to more productive, large-scale farms. However, future productivity growth and environmental performance will depend more on the capacity of professional farms to develop and take up innovation and sustainable production practice.

The evolution of Japan’s agricultural structure requires a change in the implicit policy assumption that the government needs to support small-scale, resource-poor family farms that would otherwise disappear. In Japan, the income disparity between farm and non-farm households has disappeared as agricultural production resources became concentrated on a small number of professional farms and off-farm income for small-scale side-business farms were increased. Moreover, with the rapidly changing technological conditions in agro-food value chains, innovation in agriculture increasingly depends on technologies that are developed outside agriculture. Further integration of agriculture with other parts of the economy would enable Japanese agriculture to benefit more from the competitive technology and skills that are prevalent in other sectors. In this context, developing a favourable policy environment for entrepreneurial farms to enable innovation, entrepreneurship, and sustainable resource use has become more relevant.

The types of support required by large, professional farms are different from those of traditional small family farms. For example, developing risk management tools has become more important as agricultural businesses become more vulnerable to market and production risks, especially as weather-related disasters increase due to climate change. Access to a diverse set of skills is also important as farm operations become more technology- and data-intensive, and have the capacity to engage proactively in agricultural R&D and education systems.

1.3. Developing policy and market environments more conducive to innovation and entrepreneurship in agriculture

A more demand-oriented approach would expand overseas markets for Japanese agro-food products

Japan set an ambitious target to double the export of its agro-food, fisheries and forestry products to JPY 1 trillion (USD 9 billion) from 2012 to 2019. This effort concentrates largely on overseas marketing and promotion activities, and harmonisation of quality and sanitary standards with international standards. However, the current export promotion strategy largely focuses on the supply side of export. A more demand-driven strategy would fully capture the growing demand for Japanese food products in world markets. Domestic production could concentrate more on producing high-value-added products with higher service content, while expanding the production network overseas, for example through outward foreign direct investment (FDI), to meet the diverse demand for Japanese agro-food products. Such a strategy would increase interlinkages between domestic and global value chains and create new opportunities that make the sector attractive for human capital, investment and innovation.

Commercial banks should play a greater role in agricultural finance

Agriculture is treated differently from other parts of the economy, reflecting the unique structure of the sector, once dominated by small, family farms. For example, while Japan has a well-developed banking sector and financial market, commercial banks play a relatively small role in agricultural finance. Instead, government financial institutions and agricultural co-operatives channel the generous government credit programme to producers. High levels of guaranteed credit are also likely to reduce incentives for commercial banks to develop credit evaluation systems and risk management skills for agricultural financing, or to monitor borrowers. However, Japan’s agricultural structure evolved so that large, business-oriented farms now account for the majority of production. Agriculture also became more technology- and data-intensive, incorporating services into value generation. A higher degree of interconnection with sectors through value chains facilitates innovation in agriculture as knowledge and experiences in other fields become available. In particular, regional commercial banks could play a greater role in connecting agriculture and other local industries.

Farm management policy should have a greater link with small and medium-sized enterprise policy

Fostering entrepreneurship in agriculture is a particularly important policy agenda, as entrepreneurs bring innovative ideas, products and processes to market, and attract more skilled labour to the sector. Regulations revised to expand the eligibility of non-farmers to own and rent farmland lowered the barriers to entrepreneurship in agriculture. Japan should remove the remaining obstacles to the integration of agriculture and other parts of the economy to bring competitive technology and skills from outside agriculture and enhance innovation and entrepreneurship in agriculture.

With an increase in corporate farms, farm managers face similar management issues as small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in other sectors, such as human capital development, business succession and business matching. Greater links between farm management policy and SME policy would help farm managers address their management issues and enhance networks between agriculture and other industries.

More competitive input and output markets strengthen the sector

Developing competitive input and output markets is crucial for meeting the diversified needs of professional farms. In Japan, agricultural co-operatives (JA groups; also simply referred to as JA) provide integrated services for members, including banking, insurance, farm input supply, marketing, technical advice, and welfare services. The JA profit structure shows that profits from banking and insurance cover losses in other business activities. JA also benefits from a reduction in corporate tax rates and exemption from certain regulations such as the Antimonopoly Act. Given its advantageous market position, JA maintains large shares of certain input and output markets. The dominant position of JA limits development of alternative farm service providers.

Recognising that high costs in Japan’s agricultural input markets constrain competitiveness, Japan recently implemented a number of reforms, including of JA groups, to facilitate more competition in domestic input industries and wholesale markets. JA faces a challenge in meeting the specialised and diversified needs of large, professional farms, especially as the majority of JA members continue to be side-business rice farms. A more competitive market environment between JA and other players would improve the function of farm input and output markets, and facilitate the emergence of alternative farm service providers, which are likely to introduce technology and skills from outside agriculture.

More fundamentally, domestic output price support policies result in higher input prices. In particular, under limited competition in input markets, suppliers have an incentive to raise input prices in order to capture the benefit of high output prices. Policy reform to reduce domestic market price support would eventually lead to lower input prices and improve the competitiveness of agriculture.

More diverse formats of land consolidation would contribute to productivity growth in land-intensive farming

The consolidation of fragmented farmland has been a major policy issue in Japan for the last five decades. Policies to activate land rental transactions contributed to concentration of land among large-scale producers. The farmland bank system established in 2014 enhanced the financial and regulatory incentives for land transactions. However, financial incentives attached to transactions through farmland banks may have discouraged more diverse formats of land consolidation adapted to local conditions such as contracting out farming operations, collective use of farm machinery and formation of community farm organisations.

Infrastructure development policy should adapt to the emerging technology environment

Japan has a well-developed hard digital infrastructure with the highest rate of mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants among OECD countries. However, intensive use of data in agriculture also requires the development of a soft digital infrastructure. The recent government initiative to establish a guideline on agricultural data-related contracts and a platform to co-ordinate, share and supply agriculture-related data shows efforts in this direction. The design of physical and institutional infrastructures has to be reconsidered in order to facilitate use of digital technologies in agriculture, including radio regulation, design of farm road and road safety regulations.

Agricultural support policy can be more targeted to innovation, productivity growth and sustainability

Japan provides one of the highest levels of support to agricultural producers among OECD countries. Although policy reforms over the last decade increased the role of non-commodity specific support, such as the Farm Income Stabilisation Programme, most support to producers comes in the form of market price support. Support linked to single-commodity production interferes with producers’ decisions about what to produce based on market demand, and keeps resources in uncompetitive sectors that would otherwise be reallocated to more productive uses. It also encourages more intensive production, which is incoherent with sustainability policy objectives.

Providing general services and public goods to the sector is more efficient than support to individual producers for enhancing long-term productivity growth and sustainability in the food and agriculture sector. More than 80% of Japan’s support to general services in the sector is infrastructure investment, in particular for irrigation facilities. On the other hand, Japan’s share of support to innovation and knowledge systems is particularly low among OECD countries. Japan could further rebalance the portfolio of agricultural support to be more coherent with the long-term policy objectives of boosting productivity growth and improving sustainability performance in agriculture.

Despite progress, policies to support rice prices continue to be a major part of agricultural policy

Despite a declining share of rice in the value of production, rice policy continues to be a central aspect of agricultural policy, with rice-related policies accounting for close to 40% of Japan’s producer support estimate (PSE). The government’s control of rice production and marketing impedes the optimum distribution of rice production across regions and reduces incentives for innovation in the rice sector. And although Japan has gradually reduced its direct control of the rice market over the last 25 years – ending the administrative allocation of rice production quotas and the abolishment of rice income support payments in 2018 was a milestone in this reform process – the government still maintains policy incentives to limit table rice production via payments that divert table rice production to other crops, which would support the price of rice.

Policy programmes cover a large part of the risk

The role of risk management programmes is expected to increase as large commercial farms have more exposure to market and production risks. The introduction of a revenue insurance programme in 2019 increased the choice of risk management tools for producers. However, various overlapping payment and insurance programmes make the role of each policy less clear. Moreover, most of the programmes tend to trigger payment or indemnity for relatively small reductions in farm revenue, which would usually be considered normal business risks.

Healthy risk-taking behaviour by producers is one driver of innovation and entrepreneurship at the farm level. Current risk management programmes leave relatively little room for producers to take the risks associated with new opportunities. Policy coverage to normal business risk could crowd out market-based solutions and own-farm risk management strategies, and incentivise farmers to take more risk through less diversification.

Recommendations for developing policy and market environments more conducive to innovation and entrepreneurship in agriculture

Establish a more demand-oriented approach to exploit the diverse demand for Japanese agro-food products in overseas markets, combining the domestic production of high-value-added products with higher service content and the international expansion of the production network.

Reduce the role of government credit support and increase the role of market-based finance in agriculture.

Ensure a level playing field between JA groups and other players in agricultural input and service providers by enforcing the Antimonopoly Act to end unfair practices, and by limiting cross-subsidisation between financial and agricultural businesses at local JAs.

Increase the linkage between farm management policy and general SME policy to address the need to support farm management beyond agricultural production.

Reduce financial incentives to transact through the Farmland Bank so as to diversify forms of farm consolidation, while the Farmland Bank continues to play an intermediary role between land owners and farm operators.

Develop a soft infrastructure to facilitate the digitalisation of agriculture and redesign the hard infrastructure to facilitate the adoption of new digital technology.

Provide farmers more freedom to make production decisions by phasing out commodity-specific support and progressively opening to international markets.

Simplify the overlapping risk management programmes according to risk layers and convert commodity-specific risk management programmes to a farm-based programme.

Enhance the role of farmers in managing normal business risks by lowering the threshold of revenue loss covered by policy programmes, and consider introducing voluntary co-financed risk-management programmes such as mutual funds, or a programme that allows farmers to place savings in a special account which is excluded from income declaration and possibly matched by a government subsidy.

1.4. Sustainability policy objectives should be integrated in agricultural policy framework

Japan should develop an integrated framework of agri-environmental policy

Japan’s environmental policy is generally more stringent than the OECD average. In agriculture, water quality and offensive odour regulations control point source pollution from the livestock sector, although nonpoint source pollution from the crop sector is not directly regulated by the general environmental regulation. Although improving the environmental performance of agriculture is an objective of agricultural policy, no quantitative policy target has been defined at the national and regional levels, nor are systemic assessments of the environmental performance of agriculture to define policy targets, and to monitor and evaluate its progress, in place.

Agri-environmental payments cover only 2% of Japan’s cultivated area. Policy makers need to ensure that the vast majority of farmers who do not participate in the agri-environmental payment programme improve their environmental performance. Indeed an integrated agri-environmental policy framework is needed in which all producers commit to improving their environmental performance. Agricultural policy programmes should provide consistent incentives for producers to adopt sustainable production practices and, where appropriate, impose penalties for non-performance.

Designing such a comprehensive framework for agri-environmental policies requires defined environmental targets and reference levels. In Japan, the Principles of Agricultural Production Practice Harmonised with the Environment define the reference level of environmental performance quality that farmers are required to provide at their own expense. However, the reference level is set only at the national level and its scope does not include a wider set of environmental practices such as climate change mitigation and biodiversity. The number of payments that are conditional on compliance with this environmental reference level have increased, including a major direct payment programme. Japan also strengthened the support for producers implementing the Good Agricultural Practice, which include a wider set of environmental practices, and increased the types of agricultural policy programmes which provide preference to these producers. Nevertheless the payments conditional on adopting specific production practice account for only 30% of total budgetary support to producers. This contrast with the majority of payments in the European Union and the United States which impose such a conditionality. However, experience in OECD countries shows that such conditionality is not be effective unless it is adapted to the diversity of local farming practices and conditions.

In Japan, the national government has a predominant role in agricultural policy design and its implementation. However, public goods such as water quality and biodiversity are closely linked to the local environment (OECD, 2015[2]). Subnational or local approaches, in both decision making and financing, to the provision of local public goods are superior to national approach (van Tongeren, 2008[3]), and should play a bigger role in the design and implementation of agri-environmental policy, including in the setting of locally adapted environmental targets and reference levels. To achieve regional policy goals, subnational governments could establish an integrated agri-environmental policy that combines different policy instruments, including stricter regulatory measures, agri-environmental payments and voluntary certification system. The role of the national government should be to ensure that regional plans and policy implementation are consistent with the targets set at the national level.

Sustainable use of water resource requires more effective management of irrigation infrastructure

Agriculture uses nearly 70% of water withdrawal in Japan. With the exception of a few large-scale irrigation systems, the Land Improvement Districts (LIDs) operate and maintain most of the irrigation infrastructures. LIDs allocate operation and maintenance costs to members according to land area, often without consideration for the types of crops planted or even whether the land is fallow, based on the assumption that rice could be cultivated in the future or as a second crop. The current system provides little incentive for producers to economise on water use and constrains the structural change of agriculture away from rice production. Land consolidation into a smaller number of large operations and the development of sensor technology increased the feasibility of imposing a fee based on on-farm water use.

Japan has invested heavily in its irrigation infrastructure over the last 50 years, but more than 20% of the core irrigation facilities have exceeded its expected lifespan. While members of the LIDs cover the operational and maintenance costs of irrigation facilities, the governments share the cost of rehabilitating irrigation facilities with LIDs. At present, the development, renewal or rehabilitation costs are paid by LID members on an individual project basis, which can create imbalances of costs and benefits between current and future irrigation water users. The sustainable operation and maintenance of irrigation facilities requires current and future users to equally cover the cost of renewal or rehabilitation of irrigation systems.

Recommendations for integrating sustainability policy objectives in the agricultural policy framework

Define agri-environmental policy targets at national and regional levels based on a systemic assessment of the environmental performance of agriculture with the participation of a wide range of stakeholders.

Expand the scope of environmental reference levels defined in the environmental principle to a wider set of environmental issues, including climate change mitigation and biodiversity. Environmental targets and reference levels should be adapted to local ecological conditions.

Increase the cross-compliance condition of producer support programmes with a reference level of environmental quality that is adapted to local conditions.

Design an integrated agri-environmental policy at the subnational level to achieve regional policy targets, combining regulation, agri-environmental payments and voluntary certification schemes.

Better reflect the actual water use in paddy fields on water use fees to improve water use efficiency and facilitate structural changes in agriculture away from rice production.

Include the long-term renewal or rehabilitation costs of irrigation systems in water use fees to balance the costs and benefits of the investment between current and future water users, and to maintain irrigation infrastructures sustainably.

1.5. More collaboration between public and private actors, and across sectors would strengthen Japan’s agricultural innovation system

Innovation in agriculture needs a more systemic approach beyond R&D

The predominant model for innovation has been mostly supply-driven: scientists in the public sector create new technologies which are then disseminated by extension officers to farmers who are asked to adopt them. Agricultural Innovation Systems (AIS) worldwide are in transition to better reflect user demand and generate solutions more effectively. Although research and development (R&D) remains an important component of innovation, overall innovation policy is moving beyond supply-side policies focused on R&D and specific technologies to a more systemic approach that takes into account various factors and actors, and to better reflect user demand so as to generate innovative solutions more effectively.

In Japan, public R&D institutions play a major role at every stage of agricultural R&D, while the private sector has a limited role except for certain farm inputs such as machines and chemicals. In principle, public agricultural R&D should concentrate more on areas in which the private sector underinvests, for example pre-competitive research areas with a medium- to long-term perspective, or in areas that are not specifically tied to commercial production.

More engagement of producers, agro-food and other industries in agricultural R&D is key to enhancing demand-driven and open innovation

The experience of OECD countries shows that establishing more demand-driven agricultural innovation system requires a strong partnership with stakeholders. While Japan has strengthened the engagement of producers and other stakeholders in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public agricultural R&D, more proactive engagement with stakeholders, including financing, would make the country’s AIS more demand oriented. In particular, co-financing schemes for agricultural R&D investment can be useful for producers to strengthen partnerships with research organisations and to play a leading role in the governance of agricultural R&D. This would also allow the government to channel more public funds to the medium- and long-term research agenda while boosting overall spending capacity for agricultural R&D.

However, individual producers have little incentive to finance R&D projects as most benefits of R&D accrue to the whole sector. Establishing co-funding schemes with producers requires legal and fiscal systems that encourage producers to form industry groups to collectively fund R&D projects.

The collaboration in agricultural R&D among AIS actors could be further strengthened

Recently, Japan established a platform for open innovation in agriculture and introduced a new competitive research grant to give preference to research proposed by the research consortium created by this platform. It also enhanced tax incentives for collaborative R&D between SMEs and universities. These are useful initiatives, but more integration of agricultural R&D systems with general innovation systems and removing the impediments to cross-sectoral collaboration would facilitate open innovation in agriculture.

Governance of public research institutions can be improved

OECD governments increasingly use project-based competitive funding to allocate resources to priority areas. Japan has increased project-based funding to agricultural R&D, but the share of institutional funding in public agricultural R&D budgets remains particularly high. The National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) finances around 90% of its budget from institutional funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). More use of project-based competitive funding in public agricultural R&D would facilitate the engagement of various AIS actors in agricultural R&D.

Japan has developed a comprehensive planning and evaluation system for public R&D, including the preparation of annual project plans and annual evaluations by the relevant ministries and a third-party council. While strict research management is necessary to assess the progress of R&D projects, the annual evaluation process may impede the long-term research agenda and discourage other AIS actors from collaborating with public research institutions.

Public R&D institutions are increasingly required to meet a diversity of demand by producers and to conduct practical research. As NARO’s regional research centres are increasingly oriented towards more demand-side research collaboration with regional producer groups, the gap between national and prefectural agricultural research mandates has narrowed. There is room to consolidate efforts in regional R&D through improving co‑ordination between national and regional research organisations and by clarifying the role of each organisation.

More international collaboration in agricultural research would allow Japan’s AIS to benefit from cross-border technology spill-overs

International research collaboration in agriculture strengthens Japan’s own innovation system as it allows specialisation and gains from international spill-overs. It is also particularly important in relation to global challenges such as climate change and transboundary issues. However, the degree of international co-authorship in agro-food R&D outputs in Japan is lower than the OECD average.

Recommendations for establishing a more collaborative agricultural innovation system among public and private actors, and across sectors

Focus public agricultural R&D on pre-competitive research areas with a medium-to long-term perspective and on areas that are not specifically tied to commercial production. Planning and evaluation systems of public agricultural R&D should be focused more on long-term perspectives.

Further integrate agricultural R&D systems with general innovation systems to promote cross-sectoral innovation. For example, policy linkages should be increased between core policy principles as expressed in the Basic Plan for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research, and the Science and Technology Basic Plan and Integrated Innovation Strategy.

Promote more demand-oriented agricultural innovation systems, where producers and other stakeholders proactively participate in innovation. This would include the introduction of co-funding schemes for agricultural R&D with producer organisations to reflect their demands in R&D activities and increase overall spending capacity for agricultural R&D.

Increase funding for collaboration, and co-funding with the private sector and foreign researchers and institutions beyond a limited number of competitive research grant projects. Such conditionality should be attached to funding for public agricultural R&D institutions such as NARO.

Clarify the role of national and prefectural agricultural research organisations and consolidate efforts in R&D at a broader regional level.

Simplify the administrative process for public agricultural R&D funding to increase the efficiency of research funding mechanisms and reduce transaction costs for the private sector to collaborate with public agricultural R&D institutions.

1.6. Enhancing farmers’ skills to innovate is a fundamental part of innovation policy in agriculture

Innovation in agriculture needs wider skills to adapt emerging technologies

The skills and qualifications required of farm managers in Japan has evolved with the rapidly changing technological conditions in agro-food value chains, and with the structural move towards business-oriented corporate farms. Farm managers increasingly need entrepreneurial and digital skills to develop integrated business plans beyond agricultural production, making use of both internal and external human capital and knowledge resources. In addition to fostering the skills of farmers, bringing knowledge, experiences and skills from other fields and sectors also increases the supply of skills in the agricultural innovation process. Attracting skilled labour to agriculture requires making agricultural industries more appealing and conducive to innovation and entrepreneurial opportunities. Skilled labour from different educational backgrounds can also enrich the innovation process in this sector.

Professional education in agriculture should correspond better to needed skills

The mismatch between the supply and demand of skills limits the capacity of the agricultural sector to develop and uptake innovation. Making agricultural education and training more appealing and relevant can play a critical role in attracting talent and resolving potential mismatches of skills in the labour market. In particular, responding to the evolving need for skilled labour in this sector requires retraining and the regular adjustment of educational programmes to reflect industry demand. Lifelong learning is required to prepare for agro-food jobs using new technologies. However, the engagement of agro-food industries, including producers, in agricultural education and training is much less active in Japan than in other OECD countries. A more iterative co-creation and co-development process involving multiple stakeholders is necessary to improve agricultural education in Japan.

At present, prefectural agricultural colleges, which are part of the prefectural extension system, are the main provider of vocational education in Japan. However, these colleges do not necessarily attract the most enthusiastic students who wish to be future farm managers. They also face difficulties in adjusting their educational and training programmes to the more diversified and specialised skill requirements in today’s agricultural sector.

The government has scaled-up support to young farmers entering the sector. It provides income support payments to young famers for up to seven years before and after entry. Providing more structured learning opportunities and training that combines lectures and internships in professional farming operations is likely to be more important than transitory income support for acquiring the necessary skills to become a viable farmer.

Public agricultural extension systems should evolve to increase the role of private technical service providers

Prefectural governments are responsible for providing public agricultural extension services with partial financial support from the national government. In addition, the local JAs provide technical services to its members. These services are free of charge, in contrast to other OECD countries where farmers increasingly pay for individual advice from public extension systems. However, the extension advisors working in prefectural extension services and JAs face constraints in updating their skills and knowledge as quickly as current technology and industry develop. Alternative commercial technical advisory services that could meet the needs of professional farmers for specialised and tailored advice are relatively underdeveloped in Japan, except in the livestock sector.

Many OECD countries face similar challenges to convert agricultural extension systems to more demand-driven, pluralistic and decentralised advisory services that mix public and private providers. In such systems, private technical advisory services play a major role in providing specialised technical services to commercial farmers, while public extension services still play an important role in areas of public interest, such as promoting sustainable production practices and supporting disadvantaged producers. Public extension systems often facilitate compliance with regulations or policy requirements in the field.

Recommendations to enhance farmer’s skills to innovate

Strengthen the partnership between agricultural education and agro-food industry to reflect industry demand. This would include greater participation of professional farms in teaching activities and funding.

Reorient the curriculum of vocational education in agriculture from acquiring agricultural production techniques to developing the broader skills required for future farm managers in areas such as entrepreneurship and digital technologies, provide more structured opportunities for learning, and develop training programmes that combine lectures with work experiences. One way to achieve this would be to convert existing agricultural colleges to professional and vocational universities.

Consolidate prefectural agricultural colleges at the broader regional level to pool their resources and develop a unique and specialised agricultural education that is adapted to regional conditions. This should be done in partnership with the private sector.

Concentrate prefectural extension services on areas of public interest, such as promoting sustainable production practices and supporting disadvantaged producers, as well as giving advice on compliance with regulations and government policy programmes.

Promote the development of private technical advisory services, including making JA’s advisory service more competitive through paid services.

References

[1] OECD (2015), Analysing policies to improve agricultural productivity growth, sustainably: Draft framework, http://www.oecd.org/agriculture/policies/innovation.

[2] OECD (2015), Public Goods and Externalities: Agri-environmental Policy Measures in Selected OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264239821-en.

[3] van Tongeren, F. (2008), “Agricultural Policy Design and Implementation: A Synthesis”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 7, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/243786286663.