This chapter provides key insights on the demand and supply of long-term care In Lithuania. Firstly, it highlights that population ageing and long-term care needs are sizeable and growing in Lithuania. It also describes the provision of care by family members, friends or neighbours who are called informal carers. They are the backbone of the system but receive limited, although increasing public support. Finally, it discusses the limited numbers of the long-term care workforce in Lithuania, their working conditions and qualifications.

Integrating Services for Older People in Lithuania

1. Growing demand for care and insufficient supply in Lithuania

Abstract

A substantial share of older people has care needs and limited financial resources

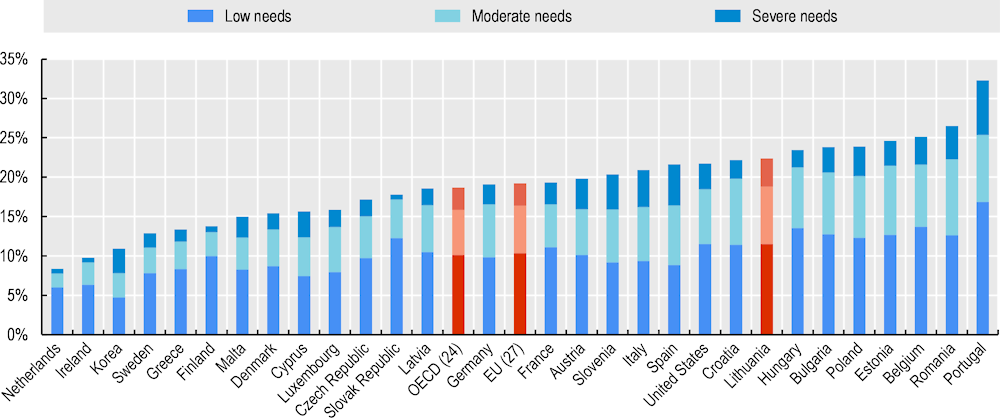

Long-term care (LTC)1 needs are high in Lithuania and are likely to increase with population ageing. Around 22% of older people in Lithuania is estimated to have long-term care (LTC) needs, compared to the EU average of approximately 19% (Figure 1.1).The share of population aged 65 years and over is expected to grow from 20% to 32% and the share of 85 years and over will grow from 6% to 12% from 2019 to 2050. Given that many older people live with some health issues, the long-term care needs in Lithuania are expected to increase in the coming years. The geographical distribution of the older population is uneven across the country, with people aged 65 or older representing a bigger share of the population in smaller counties or municipalities, generating challenges for the distribution of services.

Figure 1.1. The share of older people with low, moderate and severe LTC needs is higher in Lithuania than OECD average

Note: Low, moderate and severe needs correspond to around 6.5, 22.5 and 41.25 hours of care per week, respectively. Detailed descriptions of care recipients’ needs are available in Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal (2020[1]), “The effectiveness of social protection for long-term care in old age: Is social protection reducing the risk of poverty associated with care needs?”, https://doi.org/10.1787/2592f06e-en and are computed using adjusted survey weights. The OECD (24) and EU (27) averages are the unweighted average of the shares in each country.

Source: OECD analysis based on responses to the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA) and the Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) in the United States to estimate the prevalence of low, moderate and severe needs.

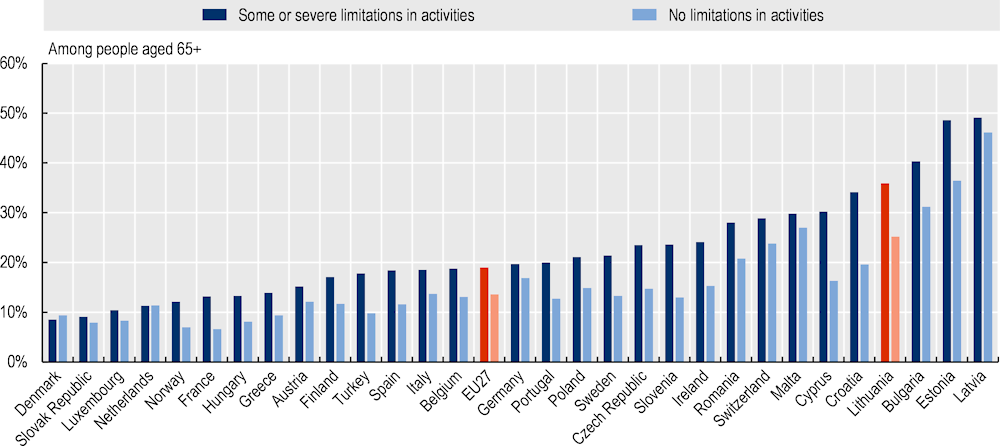

Older people in Lithuania have limited financial resources to meet the costs of long-term care privately and there is a risk that their needs are left unmet without sufficient public provision. The net pension replacement rate of men in Lithuania ranked at the second lowest among EU countries in 2018. The share of older people with activity limitations at risk of poverty in Lithuania is amongst the highest in EU countries. Nearly 35% of older people reporting limitations in activities are at risk of poverty, compared with just under 20% in EU countries on average (Figure 1.2). Currently, unmet LTC needs are relatively high in Lithuania. About 40% of older people with at least one daily limitation reported unmet LTC needs in Lithuania, compared with 30% of older people on average across 25 EU countries in 2019‑20 based on SHARE data.2

Figure 1.2. Among older people, those with limitations in activities because of health needs are more at risk of poverty

Source: Eurostat database (Data refer to 2019).

Informal carers provide the bulk of care, although they receive limited public support

The majority of older Lithuanians receive only informal care. Long-term care can be delivered by formal care workers or by informal carers. Although the definition of informal carer is not straightforward, the two cornerstones of the definition are usually that: 1) an informal carer is a family member, close relative, friend or neighbour; and 2) carers are non-professionals who did not receive qualifying training to provide care (even though they can benefit from special training). About 90% of Lithuanians use solely informal care, against 70% in European countries while less than 5% receive only formal care (Social Protection Committee (SPC) and European Commission (DG EMPL), 2021[2]).

The provision of high intensity informal caring renders the labour market participation of carers more difficult. In Lithuania, the intensity of care provided at home is higher in Lithuania compared with the EU average, although the share of people aged 45‑64 and providing informal care is broadly in line with the EU average (Social Protection Committee (SPC) and European Commission (DG EMPL), 2021[2]).

Compared to other OECD countries, the support provided to informal caregivers in Lithuania is limited, but improving. No direct cash benefits, nor formal indirect cash benefits are provided to informal carers. Lithuania has recently improved the social protection of caregivers under specific income and age conditions among other conditions: since 2020, it covers the pension and the unemployment social insurance of caregivers of people with a special need for permanent care (or assistance)3 (Ministry of Social Security and Labor of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[3]). While half of OECD countries provide paid leave to care for an older dependent, in Lithuania neither paid nor unpaid leave is in place for caregivers (Rocard and Llena-Nozal, 2022[4]).

Informal caregivers would benefit from additional support such as training and better respite care. In particular, training on medical care (e.g. bandaging wounds, treating pressure ulcer) and personal care and access to psychological support appear to be minimal in Lithuania. Focus group discussions4 suggest that informal carers need training mostly for care that requires physical movements and preserving older people’s dignity (e.g. how to turn the older people in bed, how to change diaper, how to bath). If a person is cared for by relatives living in the same household, the carer can apply to temporary respite services. However, informal carers can also face challenges to access the respite services they are entitled to because care institutions are already close to full capacity. One common strategy is to move the older people to nursing hospitals so that relatives can take a break from caring. Lithuania has recently strengthened respite services: since 2021, the temporary respite has been a separate social service in the Catalogue of Social Services and is provided on an as-needed basis, for up to 720 hours per year (in exceptional cases, and in particular in a crisis situation, temporary respite can be provided continuously for up to 90 days). Lithuania is considering further improvements to temporary respite by either including respite care in a possible forthcoming Long-Term Care Act or amending the law on Social Services.

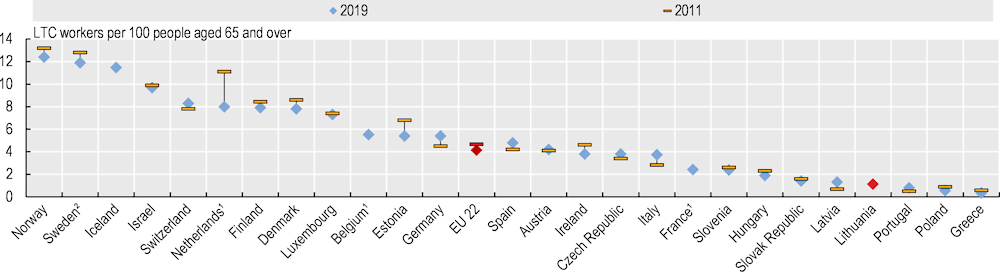

The rate of LTC workers is very low compared with the EU average

Lithuania is among the countries with the lowest levels of LTC workers across EU countries, with only one worker per 100 people aged 65 or above, in 2019 (Figure 1.3). Formal long-term care workers are paid staff – typically nurses and personal carers – who provide care and/or assistance to people limited in their daily activities at home or in facilities.5 The EU average of the number of LTC workers per 100 people aged 65 or above was 4.1 in 2019.

Figure 1.3. Lithuania has among the lowest staff levels across EU countries

Note: 1. Break in time series. 2. Data for Sweden cover only public providers. In 2016, 20% of beds in LTC for older people were provided by private companies (but publicly financed).

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2021, complemented with and EU-LFS.

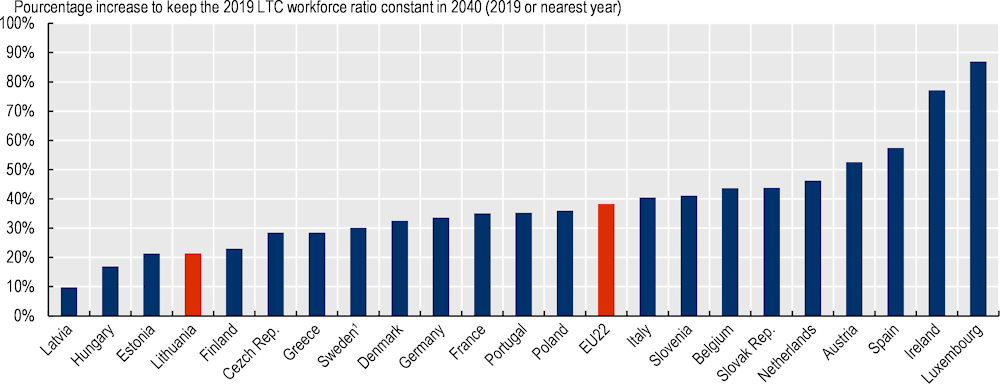

Lithuania, as all other OECD countries, would need to increase its pool of LTC workers substantially by 2040 to care for their ageing populations (Figure 1.4). Lithuania should increase its LTC workforce by 20% by 2040 if it wishes to keep the current ratio of caregivers to the elderly population. While Lithuania ranks lower compared with other EU countries, this number still represents an important increase that would require substantial policy support to develop the workforce. In comparison, relative EU countries need to increase by nearly 40% the current number of LTC workers on average.

Figure 1.4. Lithuania would have to increase its workforce by about 20% to keep its current ratio to older people constant by 2040

Note: 1. Data for Sweden cover only the public providers. The EU average is unweighted.

Source: EU-Labour Force Survey and OECD Health Statistics 2021; Eurostat Database and UN population projections for population data.

Low staffing levels are related to staff shortages and can fall well below pre‑determined quality standards with respect to staffing ratios. According to an analysis by the National Audit Office, between 2017 and 2020, the number of employees in surveyed institutions providing social care was lower than the requirements. Across 11 institutions providing daily and short-term social care at home, 4 reported shortages of social workers, 2 of nurses, and 2 of nurse assistants. Among the 13 institutions providing long-term and short-term social care, 3 had shortages of social workers, 2 of nurses and 2 of nurses’ assistants. Moreover, the workload of nurses and their assistants often does not correspond to the recommendations (National Audit Office, 2021[5]).

Lithuania is seeking to address such shortages through changes to staff mix change and better staff recognition. With respect to the health care system, Lithuania estimated being short of 2000 nurses and 6 000 nurse assistants in 2021 in total (including hospitals). Lithuania has recently changed their nurse‑nurse assistant ratio’s objective, giving more importance to nurse assistants. Lithuania plans to shift nurses’ tasks to nurse assistants and aims to have a ratio of 1 nurse for 2‑3 nurse assistants in the future (OECD Questionnaire to the Ministry of Health, 2021). In April 2022, Lithuania formed a new supervisory committee that aims to implement the guidelines of the National Nursing Policy 2016‑25, which covered qualifications and licences, training, assessment of competences, working conditions. This committee is composed of hospital nurses, representatives of nurses’ unions and representatives of universities. The Lithuanian Government is also preparing two laws on social services to make social work a better recognised professional activity. The draft laws will define social workers, clarify the concept of social work, the areas of implementation of social work, the principles of implementation of social work, and the rights, duties, and responsibilities of social workers. Finally, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour is considering that single individuals (not only social services institutions, like non-governmental organisations, private or public institutions) could be able to provide social services.

Working conditions in LTC are poor

In Lithuania, there is a high share of LTC workers in non-standard contracts (e.g. part-time and fixed-term), which undermines the sector’s attractiveness (Žalimienė, 2013[6]). A survey conducted in 2017 in Lithuania revealed that the share of employees with fixed-term contracts was 6 times higher in the home care sector than the average in Lithuania, and part-time contracts were 3 times more common than average. In comparison, nearly 45% of LTC workers across OECD countries work part-time, and almost 20% have a fixed-term contract (OECD, 2020[7]). Nurses, nurse assistants and physiotherapists usually work 7 hours and 36 minutes per day,6 but the working times can accommodate workers’ preferences. According to focus group discussions, smaller LTC facilities are less able to accommodate workers’ preferences.

LTC workers in Lithuania report several sources of stress in the workplace. In home care, the lack of communication with family members can be challenging, as well as accommodating patients’ mood swings. Lack of information around the services’ provision on the care recipients’ side is also highlighted as a challenge, with family members asking for services that are not included in the workers’ tasks. Beyond the psychological stress and risk of burnout, interviewed LTC workers report episodes of physical violence.

Salaries for LTC workers from the social sector depend on municipal budgets, generating wide differences across municipalities. Overall, in bigger municipalities, LTC workers receive more generous bonuses and premiums and are satisfied by their remuneration. In contrast, LTC workers in smaller municipalities report having fewer opportunities to receive additional payments (e.g. premiums and bonuses) to complement their fixed salary. Both the flexible and fixed components of the salary are set at the municipal level. The large range between the municipality with the lowest reported wages and the one with the highest reported wages confirms the findings of the focus groups regarding the wage gaps across municipalities (Table 1.1). The budget allocated to LTC workforce can also vary over the time, depending on the priorities of municipal budgets, which can result in uncertainty over LTC workers’ salaries.

Table 1.1. There is high variability in LTC wages across municipalities

Monthly average gross salary for LTC workers in 2021 (or latest year available)

|

EUR |

Social workers |

Social workers assistants |

Nurses |

Nurses’ assistants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Average |

1 364 |

1 059 |

1 166 |

979 |

|

Median |

1 317 |

1 021 |

1 159 |

957 |

|

As a percentage of minimum wage (EUR 642) |

205% |

159% |

181% |

149% |

|

In percentage of the median equivalised income of women (EUR 694) |

190% |

147% |

167% |

138% |

|

Lowest |

800 |

800 |

600 |

800 |

|

As a percentage of minimum wage (EUR 642) |

125% |

125% |

93% |

125% |

|

In percentage of the median equivalised income of women (EUR 694) |

115% |

115% |

86% |

115% |

|

Highest |

1 870 |

1 386 |

2034 |

1 304 |

Note: 39 municipalities reported data.

Source: OECD questionnaire, 2021.

LTC workers on the health sector fare slightly better, with improvements in remuneration in recent years. Data on nurses’ and nurse assistants’ wages submitted by the Ministry of Health appear higher than the average and median wages across municipalities. Gross monthly wage is reported to be around EUR 1 600‑1 700 (about EUR 1 100‑1 200 after tax) for nurses, and around EUR 1 000 (about EUR 700 after tax) for nurse assistants. Between 2017 and 2020 gross monthly average salaries in public providers increased from EUR 1 008 to EUR 1 659 for nurses. In addition, wages in the health care sector were increased by 6% in 2022.

Qualifications are well-defined and training opportunities exist but there are some gaps

In Lithuania, social workers and assistants need to hold specific qualifications and to undergo training. The requirements for social workers working in LTC consist in: (i) a qualification in social work or a completed programme of studies in social work and a qualification in social sciences; (ii) another completed qualification degree and a qualification as a social worker, or a completed social work study programme, or a training course to prepare for the practical activity of a social worker. In addition, social workers in Lithuania are required to undertake at least 16 hours of training every year and such training is financially compensated by the employer. Other requirements consist in the discussion of practical cases of social work at least once every four months and the participation in at least 8 hours of supervision per year. Social workers in Lithuania can also take part in an attestation process which enables them to acquire new qualifications and progress in their career. The career of a social worker has three steps: social worker, senior social worker and social worker-expert. Assistants of social workers and home care workers have to hold a specific qualification or they have to undergo an initial training of at least 40 hours to start working in social services institutions. In July 2021, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour introduced a new requirement for assistants of social workers and home care workers – both of which will be required to undergo 400 hours of training instead of 40 hours. EU Structural Funds will fund the additional training for a total of EUR 28 million, between 2021 and 2027.

With respect to the health care sector, the education of a nurse assistant lasts 9 months in Lithuania and costs about EUR 2 000 out-of-pocket. Applicants must hold a secondary education degree (high school degree). The main difference between a nurse and a nurse assistant lies in their type of tasks: nurse assistants do not play the role of co‑ordinator while nurses are allowed to perform more complex activities. Nurse and nurse assistants are also allowed to do tasks usually performed by workers of the social sector, like helping with the groceries.

Care institutions also provide additional training and opportunities, which can be either paid for by the institution or by the workers themselves. Among the municipalities with available data, training, seminars and lectures are the most common opportunity for employees’ development, available in 92% of responding municipalities. Other opportunities for development are career progression linked to skills development in 23% of municipalities. In 21% of municipalities, employees can have supervision duties and in 8% of municipalities report other practices, such as awarding letters of appreciation, team outings and exchanging best practices with other care institutions.

Focus group discussions revealed that social workers did not receive sufficient training for some of the “technical” tasks they are required to perform and on dementia. For example, they did not always know all the appropriate available services. While the prevalence of dementia is expected to increase with population ageing, in 77% of surveyed municipalities, no specific support is available for older people with dementia.

References

[3] Ministry of Social Security and Labor of the Republic of Lithuania (2021), I am caring for a family member, https://socmin.lrv.lt/lt/veiklos-sritys/socialine-parama-kas-man-priklauso/slaugau-seimos-nari (accessed on 30 March 2022).

[5] National Audit Office (2021), Care and social services for the elderly.

[7] OECD (2020), Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/92c0ef68-en.

[1] Oliveira Hashiguchi, T. and A. Llena-Nozal (2020), “The effectiveness of social protection for long-term care in old age: Is social protection reducing the risk of poverty associated with care needs?”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 117, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2592f06e-en.

[4] Rocard, E. and A. Llena-Nozal (2022), “Supporting informal carers of older people: Policies to leave no carer behind”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 140, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0f0c0d52-en.

[2] Social Protection Committee (SPC) and European Commission (DG EMPL) (2021), 2021 Long-Term Care Report. Trend, challenges and opportunities in an ageing society, https://doi.org/10.2767/677726.

[6] Žalimienė, L. (2013), Lankomosios priežiūros darbuotojų darbo vietos kokybė Lietuvoje I N G A B L A Ž I E N Ė, R A S A M I E Ž I E N Ė [[Occupational Well-Being in Social Work Services].

Notes

← 1. Long-term care represents a range of medical, personal care and assistance services that are provided with the primary goal of alleviating pain and reducing or managing the deterioration in health status for people with a degree of long-term dependency, assisting them with their personal care (through help for activities of daily living (ADL) such as eating, washing and dressing) and assisting them to live independently (through help for instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) such as cooking, shopping and managing finances).

← 2. People with unmet LTC needs refer to people who report at least one ADL/IADL limitation, but do not receive any help for limitations in daily activities, or receive help that is hardly ever or sometimes sufficient.

← 3. Since 2020, Lithuania has covered the pension and the unemployment social insurance of caregivers of people with a special need for permanent care (or assistance). Parents or guardians caring for relatives with disability are covered by the state for pension and unemployment social insurance if they have no insured income or if their income is below the minimum monthly salary, are under retirement age and do not receive their own social insurance pensions, excluding social security widows’ pensions, state pensions, social assistance pensions, social pensions or home care pensions for people with disability.

← 4. As part of the project, focus groups were undertaken with municipalities, LTC providers, LTC workers and informal carers.

← 5. A range of professionals are not considered in the above numbers such as GPs, mental health professionals (psychologists, psychotherapists, and psychiatrists), physiotherapists, dietitians, cooks and drivers.

← 6. Under Lithuanian law, the workday is 8 hours. Nurses, nurses’ assistants and physiotherapists are among the categories of workers with high emotional and physical burden whose legal workday is 7 hours 36 minutes.