This chapter compares the legislative framework on long-term care (LTC) and its implementation across relevant European countries to provide key insights for Lithuania. It presents the division of responsibilities in long-term care between ministries and subnational levels in EU countries and co‑ordination tools. It discusses how standardised needs assessments can facilitate the delivery of integrated services by ensuring a single entry point. It also presents examples of a gradation ladder for benefits and services linked to the needs assessment. Finally, it touches on quality reference frameworks for long-term care.

Integrating Services for Older People in Lithuania

3. Improving governance for integrated long-term care

Abstract

Legislation on LTC in EU countries

One important milestone to a more integrated system and improved governance is the adoption of legislation which establishes the basis of the long-term care system. EU countries differ widely on this front: some countries have specific LTC legislation while others include LTC as part of social services (Table 3.1). EU countries (or subnational areas) having legislation specifically on LTC include Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Scotland, Slovenia, and Spain. Austria has had one legislative framework since 1993. Germany legislated an LTC insurance fund and an LTC system in 1995. In Scotland, the framework for integrating adult health and social care was enshrined in the law in 2014. Slovenia passed a law in 2021 that defines long-term care and outlines the integration of health and social services for adults and older people. Conversely, in Denmark and Sweden, the legislation on LTC is achieved through the social services acts, so LTC is one component of a much broader act.

While there is no one‑size‑fits-all approach for a single LTC-related legislative framework, essential elements typically include the definition of long-term care (including a possible age threshold),1 the roles and responsibilities, the needs assessment (except in some Scandinavian countries), the cash benefits, the services, and the financing schemes. Other laws related to finance typically set the funding sources, except in countries that implement LTC insurance.

Table 3.1. LTC framework in other EU countries

|

Main legal acts structuring the LTC framework |

Description |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

- Federal Long-term Care Allowance Act (Bundespflegegeldgesetz), 1993 - Agreement according to Article 15a of the Austrian Constitutional Act’ between the Federal Republic and the federal provinces, 1993 - “24‑hour home‑based care”, 2007 |

- The Act codifies cash benefits for people in need of long-term care - This agreement defines the responsibilities of federal provinces. They are responsible for developing and upgrading the decentralised and nationwide delivery of institutional inpatient, short-term inpatient, semi‑inpatient (day care) and outpatient/mobile care services. - The 2007 reform legalises privately organised 24‑hour home‑based care LTC, which is primarily dependent on temporary migrant carers from countries like the Slovak Republic and Romania. |

|

Belgium |

6th State Reform, 2014 |

- The federal level is responsible for home nursing and physiotherapy (Federal health insurance), service vouchers (Unemployment insurance and tax rebate), and integration allowance for persons with disabilities (Federal ministry of social affairs). Regions are responsible for residential care for the elderly, including price control, day care facilities, home care, and care allowance for the elderly, other service vouchers and care for persons with disabilities. Only Flanders has a regional LTC insurance (VSB). |

|

Denmark |

Consolidation Act on Social Services, 2018 (first version in 1998) |

-The Act on Social Services municipalities are responsible for residential care in a nursing home or in a non-profit care home, and that waiting time cannot exceed two months. The Act on Social Services also prescribes that the municipal council shall offer (i) personal care and assistance, (ii) assistance or support for necessary practical activities in the home and (iii) meals services. The assistance mentioned is offered to persons who are unable to carry out the activities due to temporary or permanent impairment of physical or mental function or special social problems |

|

Estonia |

Health Services Organisation Act The Social Welfare Act |

- Nursing care service providers need to have a permit from the Health Care Board. The Ministry of Social Affairs regulates nursing services and requirements. - Municipalities to provide 11 social services (among them some LTC services), but not all municipalities abide by the law and the law allows broad interpretation. |

|

Finland |

- Health and social services reform in process |

- 21 well-being services counties would be established in Finland and entrusted with the health, social and rescue services duties that are currently the responsibility of municipalities and joint municipal authorities. The counties would be public law entities that have autonomy in their areas. A county council, elected by direct popular vote, would be the highest decision-making body of well-being services counties. There would be five collaborative catchment areas for regional co‑ordination, development and co‑operation in health care and social welfare. The government would confirm the strategic objectives of health care, social welfare and rescue services every four years. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Finance would hold annual negotiations with each well-being services county. The operation of well-being services counties would be financed mainly from central government funds and partly from client fees to be collected from the users of services. |

|

France 1 |

- Specific allowance for dependency, 1997, reformed in 2002 - Law on solidarity and loss of autonomy, 2004 - the Hospital, Patients, Health and Territories Act, 2009 - Act on adapting society to an ageing population, 2015 |

-The cash-for-care scheme is paid to any person aged 60 or over who needs assistance to accomplish everyday activities or who needs to be continuously watched over. Each level of dependency gives access to a maximum amount), which is then adjusted according to the recipient’s needs and level of income. At home, the allowance is paid either to finance a specific ‘care plan’ in the home elaborated by a multidisciplinary team (health and social professionals from the départements) after an assessment of needs, or in a residential home. The APA represents over EUR 5 billion of expenditure, of which 70% comes from the départements and 30% from the CNSA. - The 2004 law introduced the CNSA (the national solidarity fund for autonomy), a new institution responsible for implementing policy measures aimed at older people and people with disability. -The 2009 law created a new regional institution representing central government that encompass regional and local health administrations and included interventions to the social sector -The 2015 law aims to support older people facing loss of autonomy, with a priority given to homebased care, but also included healthy ageing policies and housing adaptions. |

|

Germany |

- Long term care insurance, 1995, major reform in 2017 |

-Statutory health insurance (SHI) members are insured under the social LTCI scheme and all members with private health insurance (PHI) are insured under the private scheme. The structure and level of benefits does not differ between social and private LTCI. Since 2009, insurance has been mandatory for every citizen. In 2017, the social LTCI covered 72.7 million citizens and private LTC covered 9.4 million citizens (2015). Under the social LTCI, 71.9% of benefit recipients were being cared for at home, most of them by female family members or unpaid carers. In 2017, total expenditure on benefits paid under the social LTCI scheme was EUR 35.54 billion. The 2017 reform included an expansion of eligibility criteria to include mental and psychological disabilities (e.g. dementia). In 2017, the LTCI expenditure rose of 26% compared with 2016. |

|

Latvia |

- Law on Social Services and Social Assistance - Health care laws for health care - Programme of mobile teams, 2010 |

The official institutional norms are formulated in the Law on Social Services and Social Assistance, as well as in the internal regulations of the social service agencies. The official institutional norms are: assessment of the individual’s needs; provision of services at the place of residence of the client; inter-professional and inter-institutional co‑operation; user participation; cost control. - Health care for older people are regulated based on the health care laws - Mobile teams of specialists (i.e. social worker, social care worker, and psychologist), provide social services to the elderly in their homes. These mobile teams are becoming the standard suppliers of care services in rural areas, especially those with low population density. |

|

Netherlands |

- Social Support Act (Wmo), 2015 - Long-term Care Act (Wlz), 2015 |

-Wmo: municipalities provide social services funded by block grants from the state. They are responsibilities for providing help with IADLs (cleaning, cooking, etc.) for the elderly. Municipalities have very limited tax-raising abilities. - Wlz: it is a statutory social insurance scheme. |

|

Portugal |

Decree Law 265/99, 14 July - National Network for Integrated Continuous Care (RNCCI), 2007 |

Regulates the supplement for dependency, the cash benefit for people having LTC needs The RNCCI provides convalescent care, post-acute rehabilitation services, medium- and long-term care, home care and palliative care. The Ministries of Health and Social Solidarity jointly set up the network. It comprises both public and private not-for-profit units (funded by the state jointly by both Ministries). The financing model is based on the types of services provided, with joint protocols across the health and social sectors. |

|

Scotland |

- Regulation of Care Act, 2001 - Community Care and Health Act, 2002 - Public Bodies (Joint working) Act, 2014 - The Social Care (Self-directed Support) Act, 2013 - Carers Act, 2016 |

- The 2001 Act aimed to is to improve standards of social care services. - The 2002 Act introduced 2 new changes: free personal care for older people, regardless of income or whether they live at home or in residential care and the creation of rights for informal or unpaid carers. - The 2013 Act enshrines in the law that people who are eligible for social care support must be involved in decisions about what their support looks like and how it is delivered. - The 2014 Act sets the framework for integrating adult health and social care, particularly for people with multiple, complex, long-term conditions. - The 2016 Act includes a duty for local authorities to provide support to carers, based on the carer’s identified needs which meet the local eligibility criteria, a carer support plan, a requirement for local authorities to have an information and advice service for carers, and a requirement for the responsible local authority to consider whether respite care should be provided, including on a planned basis. |

|

Spain |

- Dependency Act, 2007 |

-The law guarantees a right to long-term care services to all those assessed to require care subject to an income and asset test. Entitlements to cash and in-kind services are slightly different, with cash allowances being universal, while not all individuals might receive in-kind services. Recipients are expected to pay one‑third of total costs of services. The central government and the regions are jointly responsible for the funding and provision of LTC. |

|

Sweden |

- Social Services Act, 2001 - National Centre for support of Informal Care Providers and law in support to informal caregivers, 2008 |

- The management and planning of care for the elderly is split between three authorities – the central government, the county councils, and the local authorities. Each unit have different but important roles in the welfare system of Sweden. They are represented by directly elected political bodies and have the right to finance the activities by levying taxes and fees within the frameworks set by the Social Services Act. - The Centre is co-run by several research institutes in Sweden with mandate from the National Board of Health and Welfare. Its aim is to co‑ordinate research and development, supply information and documentations to caregivers and increase the awareness among the public and the authorities. In addition, since 2009, the municipalities are by law required to support informal caregivers. |

1. In France, there are 101 départements (implemented in 1789) and 18 régions (implemented in 1956).

Source: country-specific ESPN reports on challenges in long-term care. For Finland (https://stm.fi/en/-/government-proposal-for-health-and-social-services-reform-and-related-legislation-proceeds-to-parliament), Sweden (https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/122426/Sweden.pdf), Scotland (https://careinfoscotland.scot/topics/your-rights/legislation-protecting-people-in-care/community-care-and-health-scotland-act-2002/), click on the hyperlinks. For Denmark, see the Questionnaire on the rights of older persons with disabilities, the Danish Institute for Human Rights (2019).

The division of roles and responsibilities typically stems from historical legacies and the type of LTC-related legislation. Usually, the public bodies already have expertise and the administrative processes are already set. For example, in Scandinavian countries, the Acts on social services cover LTC, so that the roles and responsibilities in LTC are in line with those of other social services for which municipalities have competences (see Table 3.1). In Germany, roles and responsibilities are also split across the central/federal government and that of the regions. In many other countries, subnational levels often have significant responsibilities for at least part of the provision of LTC. In Spain and in France, the central government and regions/departments are jointly responsible for the provision of LTC services. In the Netherlands, municipalities are responsible only for domestic care, the insurance for home care and the central government for residential care.

Certain countries allocated significant responsibilities to a single public organisation. In this case, countries often decided to mirror the functioning, or expand the role of an existing public organisation (e.g. to collect and distribute funding). Slovenia chose to give this role to the Health Insurance Fund in its 2021 reform, in terms of the responsibility for assessment and managing the finances. France is expanding the role of one public organisation over a 10‑year period to give it most responsibilities in LTC. The institution, named the CNSA, was originally both a fund and an agency at the interface between Regional Health Agencies and Departments for LTC for older people. The goal is to give responsibilities on funding, financing and care provision to ensure the full integration and the development of LTC. The 2020 law started the expansion by transferring the current funding schemes to the CNSA and its transformation is expected to be achieved in 2030.

Some countries have also developed co‑ordination arrangements, such as intergovernmental committees and regular formal meetings, for consensus-building across stakeholders on the practical implementation of the long-term care system. In particular, quasi-federal countries and Nordic countries have made progress toward better vertical co‑ordination among levels of government. Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden have regular meetings of central and local governments (through their associations of local governments) to discuss policy and implementation issues. For example, Swedish municipalities are incentivised to co‑operate (OECD, 2015[1]). Countries use incentives to enhance inter-municipal co‑operation and networking, information sharing, and sometimes to help in the creation of joint authority entities. These incentives are frequently financial: special grants for inter-municipal co‑operation, special tax regimes, and additional funds for joint public investment proposals. In France, each grouping of communes constitutes a “public establishment for inter-municipal co‑operation” (EPCI). To encourage municipalities to form an EPCI, the central government provides a basic grant plus an “inter-municipality grant” to preclude competition on tax rates among participating municipalities. EPCIs draw on budgetary contributions from member communes and/or their own tax revenues.

In Spain and France, co‑operation bodies help to co‑ordinate national and subnational entities. In Spain, long-term care is co‑ordinated within the Territorial Council of the public System for Autonomy and Care for Dependency, a co‑operation body where the central government and the regions agree on a framework for intergovernmental co‑operation, the intensity of services, the terms and amounts of financial benefits, the criteria for co-payments by the beneficiaries, and the scale of dependency that is used for the recognition of dependency. In France, the “conference of funders” aims to co‑ordinate in each department the actions for the prevention of loss of autonomy of people aged 60 and over and their financing as part of a common strategy. The CNSA pilots and leads the conference of funders at the national level. Each department is responsible for co‑ordinating the conference of funders in its territory. Lithuania could use these examples as inspiration to create a co‑ordination tool to build consensus over time for areas where there are diverging views as it works on implementing change.

Slovenia is a relevant country example to learn about consensus building and on the challenges of developing legislation. In 2017, a draft reform was not adopted after receiving criticism from several important stakeholders. It was considered too abstract on many points, including the financial sustainability in the medium or long term; the estimated resources on the short-term were based on an inaccurate distribution of users;2 the users’ rights; and the criteria that would have placed the eligible users into 5 categories of a gradation scale (Rupel, 2018[2]). Slovenia succeeded in passing a landmark reform in December 2021 after over 20 years of discussion, 5 different scenarios to develop LTC and 2 rounds of public consultation open to all stakeholders. Slovenians agreed on the broad funding routes – a mix of a new LTC insurance born by workers, current pension and health insurance funds reallocated to LTC and state budget. In accordance with the LTC Act, funding for LTC will be provided from existing funds and the state budget until mid‑2025. The adoption of a specific law on compulsory insurance for long-term care is planned within this timeline.

Harmonising conditions for services and cash benefits across sectors is needed to integrate health and social benefits for older people

Unified needs assessment facilitates the delivery of integrated services

In Lithuania, the needs assessment tools for home services differ across the health and the social sectors. The country could therefore invest in a needs assessment mechanism which would facilitate the delivery of services and function as a single entry point. Nation-wide standardised needs assessments are in place in a large share of countries to ensure a single entry point, equal access and reduce cost-shifting (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain). However, some countries have more than one LTC needs assessment, because they target different benefits (e.g. a specific cash benefit) or because they are designed by and for subnational areas. For example, Swedish municipalities set their own needs assessment. In Finland, municipalities could also rely on their own needs assessment but there has been a progressive move towards the use of a standardised tool. The choice of needs assessment has massive financial implications. The broader the scope, the more people are eligible, and the more services are used. For example, when Germany put more weight on dementia in its assessment tool in 2017, the expenditure of the LTC insurance increased by 25% that year (ESPN, 2018[3]).

Lithuania can create an effective needs assessment by relying on a case‑mix classification based on various evidence‑based scales. Lithuania could use a case mix classification3 that weights the outcomes of various evidence‑based scales measuring different aspects of long-term care to create groups of statistically related patients. Otherwise, it can consider creating a case mix classification with their own scale. While this would enable Lithuania to design a tool based on their own characteristics, this option would require more resources and time.

The case mix classification can be based on various evidence‑based scales to capture different aspects of LTC. There is not a single best needs assessment instrument in OECD countries. Instead, various questions are typically grouped together to create scales. Theses scales focus on measuring specific aspects of long-term care – physical movement, memory, behaviours, and so on. Extensive research has been conducted to confirm their effectiveness (Sinn et al., 2018[4]). These evidence‑based scales include:

ADL

IADL

Cognitive performance scale

Communicative Scale

Pain scale

Aggressive behaviours scale

Pressure ulcer risk scale

CHESS- Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Signs and Symptoms

MAPLe‑ Method for Assigning Priority Levels

Deaf/blind severity index

Defining the relative weights of the scales in the case mix classification requires a knowledge of the drivers of home care utilisation (e.g. most frequent needs or the services mostly used). This enables to predict utilisation and cost accurately, which is paramount for the related payment system. In this sense, merely replicating an assessment used in another country has drawbacks. Japan conducted the analysis of the drivers of care utilisation to determine the most appropriate case‑mix classification and develop their scale. Such analysis allowed Japan to tailor the tool based on the specificities of the Japanese population and system and prevented the mere replication of the American case mix classification, which would have focussed too much on physical therapy (Box 3.1). Researchers in the Netherlands have also conducted a similar analysis to serve as input for the development of a new payment system for home care (Elissen et al., 2020[5]).

Box 3.1. Japan carried out a large‑scale time‑study research to understand the drivers of care utilisation to predict utilisation and cost, before deciding on the case mix classification

The instrument in use in Japan was developed based on a large‑scale time‑study of professional caregivers in LTC institutions and their users in 1995. The study sample involved 51 facilities that national associations of LTC facilities recommended as high-quality service providers. A licensed professional employee of the study institution followed a peer formal carer for 2 days and made detailed minute‑by-minute records of all of his or her activities as well as the name of each person receiving the nursing care service. The data on approximately 10 million minutes of care provided by 2 376 professionals to 3 800 older people were coded into 328 predetermined care activities, and the amount of time the caregiver spent on each older person was calculated for each activity. These data were used to develop tree regression models in which older adults’ use of services (measured in minutes by nine service categories) was regressed on their physical and mental characteristics.

The tree regression estimation models were pilot tested on 175 129 older people in the institutions and home/community settings in all the municipalities between 1996 and 1998. The validity of the models was examined by comparing the computer-aided assessment with health professionals’ assessment of each case, with 71.5% and 75.3% concordance in 1996 and 1997, respectively. Feedback from various stakeholders was used to refine the assessment instrument its implementation.

Before carrying out this study, Japan had considered to adopt the Resource Utilisation Group Version III (RUG-III). This is an assessment developed for nursing homes in the United States and is based on the use of resources in expenditures. In particular, an important determinant of the RUG-III was the rehabilitation services provided by physical therapists, because they are among the most expensive services in nursing homes in the United States. In Japan, physical therapy is much less common – none of the residents of nursing homes in the pilot study had a 30‑minute individualised rehabilitation session.

Source: adapted from (Tsutsui and Muramatsu, 2005[6]).

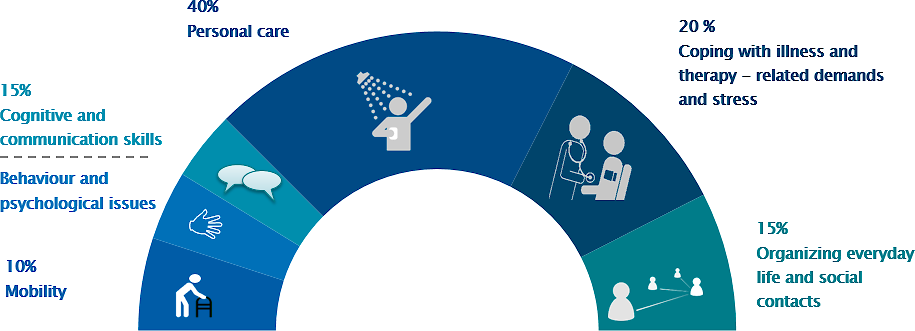

Lithuania could consider an approach similar to that of Slovenia and test tools. In 2018, Slovenia decided to develop their own needs assessment tool, building on the German needs assessment. Germany uses a needs assessment which is particularly comprehensive. The regional Health Insurance Funds or private LTC insurance companies appoint independent assessors who measure abilities in six domains (Figure 3.1) and for each criterion, a point value of self-reliance ranging between 0 (full self-reliance) and 3 (full dependence to assistance) is attributed. The domains have different weights, the highest weight being for the personal care domain and the lowest for the mobility domain. The total score is used to attribute a level of severity of impairment ranging from 1. Minor impairments to 5. Most severe impairments. Slovenians tested the scale for 2 years with over 300 000 assessments. During the pilot phase, they tailored it to the Slovenian needs notably by grouping assessments in sets for home care, social contacts, ability to manage the disease, and mental health. They carried out an evaluation that found that the needs assessment tool was appropriate and could be implemented (Buescher, Wingenfeld and Schaeffer, 2011[7]).

Figure 3.1. The German needs assessment is very comprehensive

Source: National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds, based on https://www.mdk.de/fileadmin/MDK-zentraler-Ordner/Downloads/01_Pflegebegutachtung/1901_Pflegeflyer_ENG_01.pdf.

Considerations on the pool of the workforce who can carry out the needs assessment influence the design of the most appropriate assessment. In a number of countries (Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Spain), the assessment is performed by a health professional or a multidisciplinary team composed of at least one health professional. In Luxembourg, a social worker or a health professional can perform the assessment. In other countries like Denmark, England, Estonia, the Netherlands and Sweden, social workers perform the assessment. In Japan, the needs assessment tool and the training were designed to ensure that the assessors would not require medical nor social service expertise. However, the mayor of municipalities appoint doctors, nurses and social workers to form a Nursing Care Needs Certification Board, to review and validate the initial assessment, considering the applicant’s primary care physician’s statement and the notes written by the assessor during the home visit (Tsutsui and Muramatsu, 2005[6]). Slovenia plans that the Health Insurance Institute will train and supervise a broad range of future assessors, including non-health professionals.

With respect to training, countries typically develop training manuals and videos that are regularly updated. For example, Japan developed textbooks and videos that are updated every year. Municipalities are responsible for training the workers with these materials. The training, ranging from 3 to 7 days depending on the assessors’ abilities, focusses on needs assessment for various situations, including the assessment of older people with dementia who also receive care from informal carers.

The frequency of re‑assessment should also be considered. For example, the LTC needs of older people is reassessed every two years or after a marked deterioration in Japan (Japan Health Policy NOW, n.d.[8]). In Ontario, Canada, needs assessment is carried out every six months for home care. A study found that 80% of home care clients had significant clinical changes in health status within 6 months and that the cost of assessment represented 1.55% of the home care cost (CAN 23.6 million vs CAN 1526.5 million) (Kinsell et al., 2020[9]).

A digital needs assessment has many advantages

A digital needs assessment enables to have a wealth of information relevant to key questions facing providers and decision makers across the health and social services. If digital assessments are regularly carried out, care providers could more easily evaluate the effectiveness of care plans and public agencies could evaluate the quality of care. The purposes of a digital needs assessment include:

Eligibility for public support

Care planning for providers (provided that the assessment takes place on a regular basis)

Evaluation of care effectiveness (thanks to longitudinal microdata)

Monitoring of providers’ care quality indicators

Monitoring of care quality at the municipal and national levels

While many digital assessment instruments exist, InterRAI seems to be one well-considered (RAI stands for Resident Assessment Instrument). InterRAI is a collaborative network of researchers and practitioners in over 35 countries that developed modules for people who are medically complex and/or people with disability. However, there are two fundamental pre‑requisites to have a digital needs assessment: having an excellent IT system and having trained staff.

A single benefit with different levels is user-friendly and promotes transparency

The introduction of a standardised needs assessment would enable Lithuania to have a single benefit with different care levels. After assessing the degree of autonomy, older people could be assigned to a specific care level or grade, depending on the severity of their condition, and each care level or grade can be related to a different financial compensation or intensity of service. This could ensure that access to LTC cash benefits and services is identical across the country and this approach tends to be easier to navigate for LTC recipients and their relatives. Each care grade could be related to a type of support, whether it be formal services, a cash benefit to LTC users, or direct or indirect cash benefits for informal caregivers. It can empower LTC users to choose the form of LTC care that works for them, whether that be formal or informal – which can partially address staff shortages.

Germany has such a benefit with five different care grades and the possibility to have services at home or residential care, or to receive a cash benefit. Between grade 2 and 5, beneficiaries can combine benefits in cash with benefits in kind according to their personal needs within certain limits. Since 2015, an unused allowance of up to 40% for professional home care can be used for reimbursement of costs for easily accessible services for daily-life assistance (Rodrigues, 2018[10]). The value of the cash benefit is lower than the value of services by a professional carer at home (Table 3.2).The cash benefit can be given to a relative who receives social protection if entitled. The entitlement is open to anyone who takes care of one or more people with a care grade of 2 to 5 for at least 14 hours and who is not employed elsewhere for more than 30 hours a week. They are not eligible if they receive a full old-age pension. They are covered by the statutory pension insurance and the unemployment insurance. The contribution rate depends on the level and length of care provided. They also receive training. (Rodrigues, 2018[10]). Beneficiaries can combine in cash benefits with benefits in kind within certain limits.

Table 3.2. The benefit package related to the gradation ladder in Germany is particularly comprehensive

|

Care degree/EUR per month |

Cash benefit |

Professional care at home |

Preventive care (household member-other people) (up to 6 weeks/year) |

Short-term care (up to 8 weeks/year) |

Additional day- and night-care |

Residential care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

125 |

|||||

|

2 |

316 |

724 |

474‑1612 |

1774 |

689 |

770 |

|

3 |

545 |

1363 |

818‑1612 |

1774 |

1298 |

1262 |

|

4 |

728 |

1693 |

1092‑1612 |

1774 |

1612 |

1775 |

|

5 |

901 |

2095 |

1352‑1612 |

1774 |

1995 |

2005 |

Note: other benefits includes EUR 4 000 per living environment improvement measure.

Source: German Federal Ministry of Health (2022[11]), Zahlen und Fakten zur Pflegeversicherung [Data on long-term care insurance].

Slovenia’s recent assessment and care levels builds on the German one. There are 5 categories and people can choose to receive a cash benefit or formal care at home or in an institution. Those with the highest needs (grades 4 and 5) will also be able to register an informal caregiver as a carer. Eligibility will not be restricted to relatives nor co-residents. The carers will receive 1.2 times the minimum wage and will be able to access respite for 21 days per year (by placing the older person in an LTC facility). Rehabilitation services will also be offered. The legislation is expected to be implemented in 2024‑25.

In Scandinavian countries, practices vary across municipalities to decide how much and what type of care people receive, but they promote a people‑centred approach with universal entitlement to care. In Denmark, many municipalities differentiate between five levels of LTC needs and provide rights to different amounts and types of home help based on these 5‑category scales. Older people are offered a choice between at least two different providers of home help, one of which can be a municipal one. In 2016, 36% of home help beneficiaries chose a private provider (Kvist, 2018[12]). LTC benefits tend to be in-kind for older people but there are some exceptional circumstances where cash benefits are available for their relatives who provide LTC services. Typically, the municipality sets the eligibility criteria, acts as employer and defines the services that should be provided by the informal carer. In Denmark, only people under retirement age can be eligible (Kvist, 2018[12]).

Additional incentives could be considered by Lithuania to encourage home care instead of residential care. For example, in Germany, the amount of the benefit related to lower care grade limits the option of residential care – only those with higher LTC needs receive an amount sufficiently high to cover well the cost of residential care. Hungary has taken another approach: there are 3 levels and Levels 1 and 2 give access to home‑based social help and personal care and Level 3 access to institutional care. It determines a level of care need ranging from 1 to 3 (1. needs support in some activities, 2. needs partial support, 3. needs full support).4 Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that as population ageing progresses, residential care for certain individuals with high needs would remain a necessity. In Germany, community-based LTC expenditure rose from EUR 11.1 billion to 35.5 billion and residential care‑related expenditure still increased from EUR 10.8 billion to 14.7 billion between 2012 and 2021. More than half of residential care beneficiaries are suffering from dementia. In Japan as well, dementias and strong cognitive impairments seem to bring people to choosing residential care.

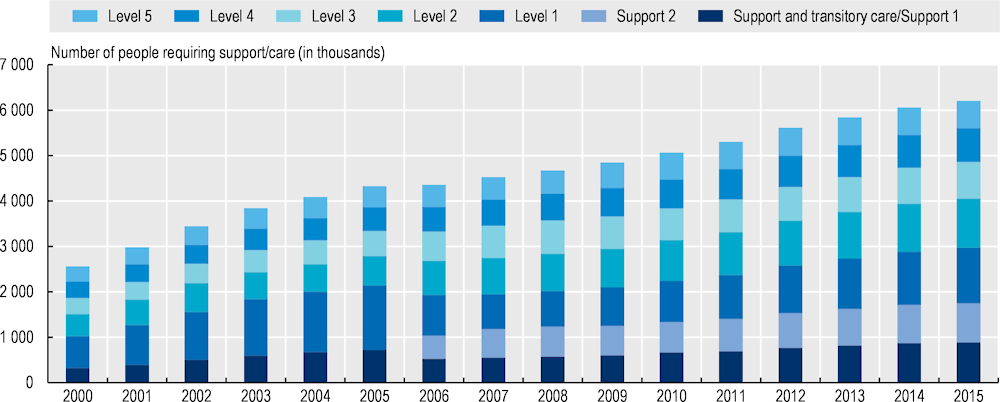

The single benefit with different care grades can be modified to encourage preventive support and help to contain cost. Japan added a new category in 2006 to contain cost while keeping a large access to LTC benefits. Care Level 1 was split into Long-term Care Level 1 or Preventative Support Level 2 depending on whether their condition seemed likely to improve or remain the same (Figure 3.2). People receiving Support Level 1 decreased by nearly 40%.

Figure 3.2. Japan split its Level 1 into two levels to encourage preventive support while containing cost

Source: Japan Health Policy NOW (n.d.[8]), 3.2 Japan’s Long-Term Care Insurance System, https://japanhpn.org/en/section-3-2/.

Quality reference frameworks would be relevant to unify sectors and providers

Lithuania could also improve quality monitoring and ensuring sufficient standards while developing home care. A key element of this strategy could be developing an appropriate quality framework, improving transparency about standards and ensuring timely evaluation. Quality indicators on providers could be better monitored, including with inspections, and their results could be published online, specifically for home providers, with an emphasis on process and outcome‑oriented performance indicators (e.g. quality of life). Agreements with private and public providers to guarantee services could include a quality section and minimum quality standards could be better incorporated into public procurement.

Several countries have recently reviewed or are reviewing quality frameworks. France’s health authority (HAS) published on March 2022 the first national reference framework for evaluating quality in the social and medico-social sector, which covers over 40 000 facilities and services, and its related evaluation manual. The goal was to have a single and uniform national framework. This evaluation is designed to promote a continuous quality improvement approach (Haute Autorité de Santé, 2022[13]). Germany plans to introduce in 2023 a revised LTC quality framework and quality monitoring system, including for home care. Sweden is also revising its quality framework in light of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Over the past decades, practices of procurement, purchasing and contracting of services of not-for-profit and for-profit providers have developed in EU countries, making quality standards and monitoring particularly relevant. The data on public, not-for-profit and for-profit provision of long-term care is sparse and outdated, but estimates suggest there is significant heterogeneity across countries and settings (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3. Non-public provision of LTC varies starkly across countries

|

Country |

Public provision |

Not-for-profit provision |

For-profit provision |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Institutional |

Home care |

Institutional |

Home care |

Institutional |

Home care |

||||

|

Austria |

55% |

8% |

24% |

91% |

21% |

1% |

|||

|

Belgium (Flanders) |

36% |

52% |

12% |

||||||

|

Belgium (Wallonia) |

26% |

21% |

52% |

||||||

|

Belgium (Brussels) |

24% |

13% |

62% |

||||||

|

Canada |

32% |

- |

31% |

- |

37% |

- |

|||

|

Czech Republic |

65% |

22% |

13% |

||||||

|

Estonia |

55% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||

|

United Kingdom (England) |

7% |

14% |

13% |

11% |

80% |

74% |

|||

|

Finland |

56% |

93% |

- |

- |

44% |

7% |

|||

|

France |

23% |

15% |

55% |

65% |

22% |

20% |

|||

|

Germany |

5% |

2% |

55% |

37% |

40% |

62% |

|||

|

Hungary |

54% |

45% |

0.4% |

||||||

|

Italy |

30% |

50% |

20% |

||||||

|

Ireland |

22% |

7% |

71% |

||||||

|

Latvia |

67% |

0% |

33% |

||||||

|

Lithuania1 |

43% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||

|

Luxembourg |

48% |

- |

29% |

- |

23% |

- |

|||

|

Netherlands |

0% |

80% |

20% |

||||||

|

Slovak Republic |

75% |

23% |

2% |

||||||

|

Slovenia |

37% |

- |

37% |

- |

26% |

- |

|||

|

Spain |

23% |

24% |

53% |

||||||

|

Sweden |

75% |

- |

10% |

- |

15% |

16% |

|||

|

Switzerland |

30% |

30% |

40% |

||||||

Note: Data coverage and years vary – data should be interpreted with caution. 1.In Lithuania, data refer only to care institutions for older people (not adults with disabilities).

Source: Adapted from Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi et al. (forthcoming[14]), Providing Long-term Care: What to Cover and for Whom; based on Gasior et al. (2012[15]), Facts and Figures on Healthy Ageing and Long-term Care; and Harrington et al. (Harrington et al., 2017[16]), Marketization in Long-Term Care: A Cross-Country Comparison of Large For-Profit Nursing Home Chains, https://doi.org/10.1177/117863291771053; for Canada and the US, complemented with Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal (2021[17]), COVID‑19 in long-term care: Impact, policy responses and challenges, https://doi.org/10.1787/b966f837-en.

Quality standards need to be an important metric for the accreditation of services and providers. In Denmark, each year the municipalities determine quality standards for home help, rehabilitation, and training services: these are publicly available, and used in tenders and in audits. The purpose of quality standards is to ensure that citizens get professional, dignified and qualified treatment in the event that they need help and support. Municipal audits include at least one unannounced visit to nursing homes and care homes (Kvist, 2018[12]). Italy passed in 2021 an extension of authorisation and accreditation to home care. Public and private providers of home care should undergo an authorisation and accreditation process to evaluate whether they meet structural, technological and workforce standards. In many countries, agencies dedicated to the monitoring of providers’ compliance were established. National and regional legislation also advanced authorisation and accreditation mechanisms, including the definition of quality indicators, even if these are often structural and process indicators that describe individual services and facilities rather than outcome‑oriented indicators (European Social Network, 2021[18]). In addition, some providers implemented standard quality management systems (ISO 9000ff, EFQM) or adapted quality management systems to their organisation (European Social Network, 2021[18]).

Quality metrics can be linked to price levels, although this is not common. Among 8 OECD countries studied, the majority released information around quality and prices to promote trust and transparency, although the impact has not yet been evaluated (OECD/WHO, 2021[19]). In Germany, the contracting parties can also agree on prospective remuneration with pricing of certain quality aspects, but this is not mandatory. The care facility has the legal right to performance‑based remuneration.

Beyond monitoring and evaluation of standards, online publishing of quality indicators can encourage providers to strengthen high-quality care. Reporting and publishing quality indicators allows monitoring the performance disparities across and within countries and the improvements over the time. Lithuania could put in place a system of public quality reporting, as in Sweden, England or the United States. Swedish municipalities must report their data on some quality indicators, which are made public in Open Comparisons (Public health agency of Sweden, 2022[20]). The figures are easy to read, with traffic-light colours indicating performances (green-yellow-red) (Trygged, 2017[21]). In England, the Care Quality Commission carries out inspections and issue ratings for care providers and it is also in the process of expanding the scope of their assessments to include local authorities themselves as part of an ongoing reform. In the United States, The Nursing Home Quality Initiative (NHQI) also uses an easy-to-read format, associating to every LTC service (e.g. Nursing homes, home health services, rehabilitation facilities and LTC hospitals) a five‑star rating based on a set of quality indicators and users’ satisfaction (OECD/European Union, 2013[22]). However, the five‑star rating system has been criticised because many consider that providers – who are those entering information on e.g. staff ratios – over evaluate their standards.

References

[7] Buescher, A., K. Wingenfeld and D. Schaeffer (2011), “Determining eligibility for long-term care - lessons from Germany”, International Journal of Integrated Care, Vol. 11/2, https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.584.

[14] Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi, T. et al. (forthcoming), Providing Long-term Care: What to Cover and for Whom.

[21] Crowther-Dowey, C. (ed.) (2017), “Open comparisons of social services in Sweden—Why, how, and for what?”, Cogent Social Sciences, Vol. 3/1, p. 1404735, https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1404735.

[5] Elissen, A. et al. (2020), “Development of a casemix classification to predict costs of home care in the Netherlands: a study protocol”, BMJ Open, Vol. 10/2, p. e035683, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035683.

[3] ESPN (2018), ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care - Germany, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19848&=en.

[18] European Social Network (2021), Putting Quality First, https://www.euro.centre.org/publications/detail/3958.

[15] Gasior, K. et al. (2012), Facts and Figures on Healthy Ageing and Long-term Care.

[11] German Federal Ministry of Health (2022), Zahlen und Fakten zur Pflegeversicherung [Data on long-term care insurance].

[16] Harrington, C. et al. (2017), “Marketization in Long-Term Care: A Cross-Country Comparison of Large For-Profit Nursing Home Chains”, Health Services Insights, Vol. 10, p. 117863291771053, https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632917710533.

[13] Haute Autorité de Santé (2022), La HAS publie le premier référentiel national pour évaluer la qualité dans le social et le médico-social, https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3323113/fr/la-has-publie-le-premier-referentiel-national-pour-evaluer-la-qualite-dans-le-social-et-le-medico-social (accessed on 10 April 2022).

[8] Japan Health Policy NOW (n.d.), 3.2 Japan’s Long-Term Care Insurance System, https://japanhpn.org/en/section-3-2/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

[9] Kinsell, H. et al. (2020), “Spending Wisely: Home Care Reassessment Intervals and Cost in Ontario.”, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, Vol. 21/3, pp. 432-434.e2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.007.

[12] Kvist, J. (2018), ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in long-term care in Denmark.

[1] OECD (2015), Integrating Social Services for Vulnerable Groups: Bridging Sectors for Better Service Delivery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233775-en.

[22] OECD/European Union (2013), A Good Life in Old Age?: Monitoring and Improving Quality in Long-term Care, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264194564-en.

[19] OECD/WHO (2021), Pricing Long-term Care for Older Persons, World Health Organization, Geneva/OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a25246a6-en.

[20] Public health agency of Sweden (2022), Regional Comparisons Public Health 2019, https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/public-health-reporting/regional-comparisons-public-health-2019/ (accessed on 2022).

[17] Rocard, E., P. Sillitti and A. Llena-Nozal (2021), “COVID-19 in long-term care: Impact, policy responses and challenges”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 131, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b966f837-en.

[10] Rodrigues, R. (2018), Peer Review on “Germany’s latest reforms of the long-term care system”, Berlin (Germany), EC DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=9008 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

[2] Rupel, V. (2018), ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in long-term care.

[4] Sinn, C. et al. (2018), “Adverse Events in Home Care: Identifying and Responding with interRAI Scales and Clinical Assessment Protocols”, Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, Vol. 37/1, pp. 60-69, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0714980817000538.

[6] Tsutsui, T. and N. Muramatsu (2005), “Care-Needs Certification in the Long-Term Care Insurance System of Japan”, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 53/3, pp. 522-527, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53175.x.

Notes

← 1. This element is key to ensure that LTC benefits are coherent with disability benefits. The trade‑off between the generosity of the disability benefits and the number of eligible people is more straightforward compared with the trade‑off for LTC benefits – the number of eligible people is more limited for disability benefits.

← 2. The calculations of the costs of formal care were based on the structure of recipients of informal LTC, where virtually nobody was in the highest care category.

← 3. The term case‑mix refers to the type or mix of statistically related patients. The best-known classification system in health care is the Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs.)

← 4. The instrument is composed of 14 variables (orientation in time and space, appropriate behaviour, eating, dressing, personal hygiene, using the toilet, continence, communication, observing the rules of the therapy, change of position, movement, self-sufficiency, seeing, hearing).