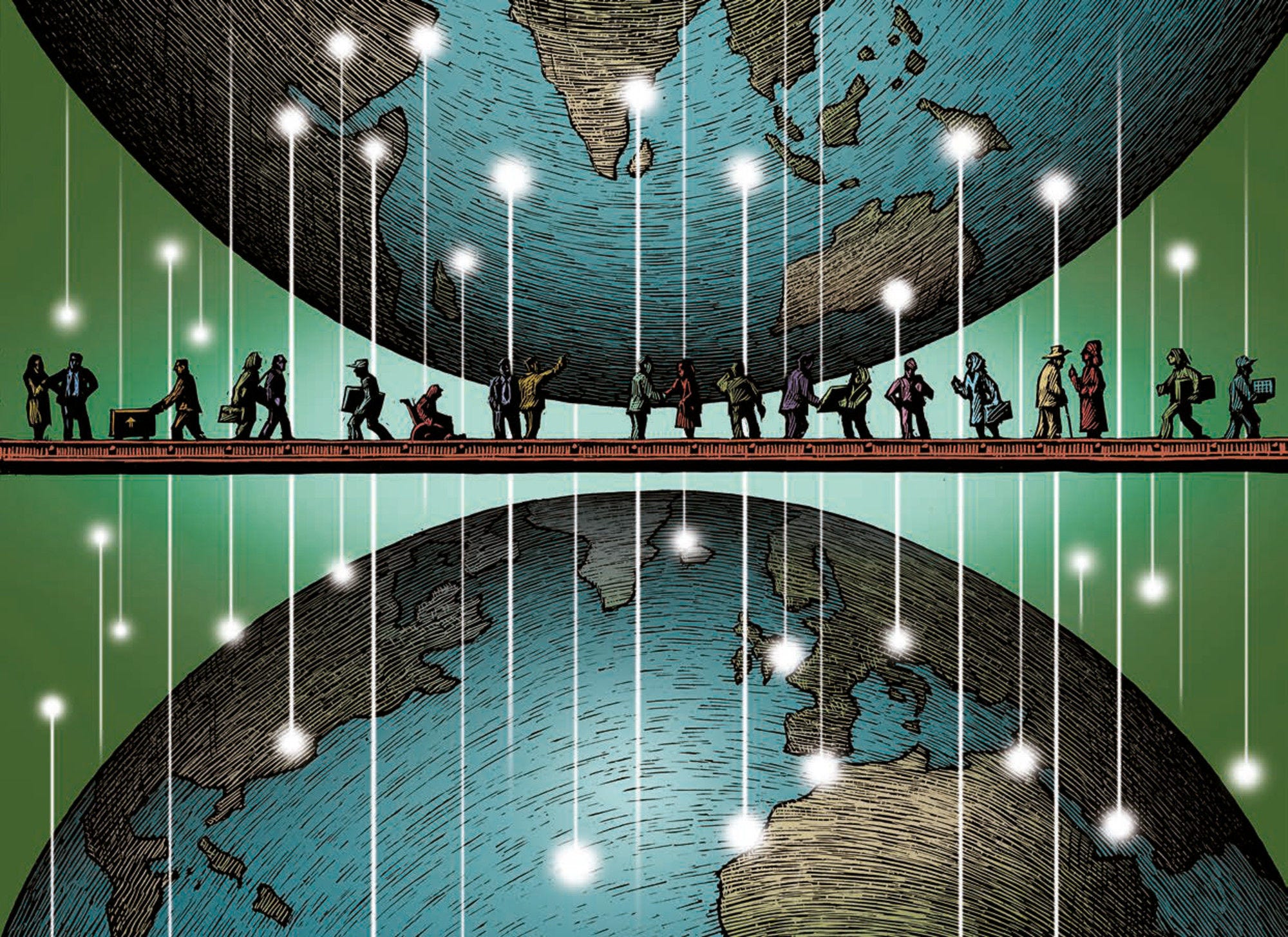

In 2020, there were 4.4 million international students enrolled in the OECD, accounting for on average 10% of all tertiary students. The most important receiving countries are the United States (22% of all international students), the United Kingdom (13%) and Australia (10%). While the destinations of international students have diversified over the past decade, the main origin countries remain China and India (22% and 10% of all international students, respectively).

Over the past decade, almost all OECD countries implemented wide‑ranging policies to retain international students after completion of their degree, but the retention of international students varies greatly. Five years after initial admission, more than 60% of international students who obtained a permit for study reasons in 2015 were still present in Canada and Germany, around half in Australia, Estonia and New Zealand, and around two in five in France and Japan. The share of students remaining was below 15% in Denmark, Slovenia, Italy and Norway.

Former international students are an important feeder for labour migration in many countries. Transition from study permits accounted for a large share of total admissions for work in 2019, especially in France (52%), Italy (46%) and Japan (37%). In the United States, former study (F‑1) permit holders accounted for 57% of temporary high-skilled (H‑1B) permit recipients.

During their studies, between one in three and one in four international students work in the EU, the United Kingdom and the United States, about one in two in Australia and nine in ten in Japan. International students who remain in the host country post-study have long-term employment rates that are on par with those of labour migrants and well above those of migrants overall. Their overqualification rates are half of those of labour migrants or other migrant groups.

While student migration can be of great benefit, the delegation of a gatekeeping role to higher education institutions, and the growing share of economic migration comprised by former students, still carry a number of risks, including distorting migration regulation and undermining labour market regulations.