This chapter provides an overview of the concept of green jobs used in this report. It describes the evidence of the effects of green policies on the economy, including the labour market. It reviews and explains the main approaches commonly used to define green jobs and describes their advantages, caveats, and limitations. Finally, it describes how the share of green jobs can be estimated at the regional level to shed light on the green transition’s impact on local labour markets and to inform policy.

Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2023

1. The green transition and jobs: what do we know?

Abstract

In Brief

Despite the fundamental changes the green transition entails for labour markets, there is a lack of systematic evidence on the green transition’s impact on local labour markets. So far, analysis on the location and geographic distribution of green jobs has been limited to just a few countries. Similarly, information on the characteristics of workers in green jobs has also been scarce. This lack of evidence creates a barrier for effective policy.

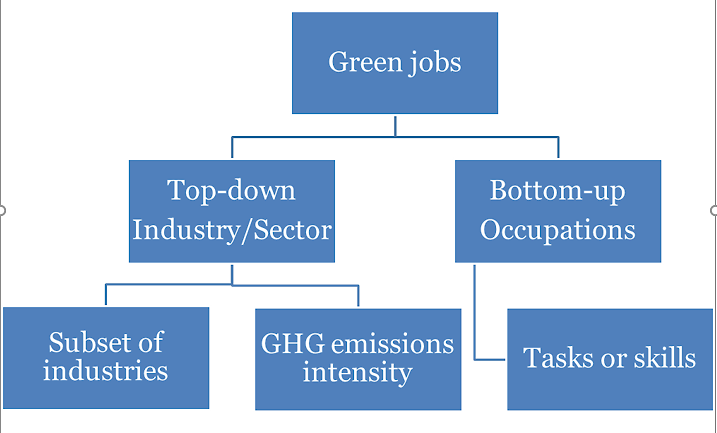

Different approaches to classifying green jobs exist and complement each other. Top-down approaches classify jobs as green if they are in specific sectors or industries. Bottom-up approaches define green jobs based on the skills or tasks different occupations require and the extent to which those tasks or skills are green.

This report uses information on occupations’ tasks to measure green jobs at the regional level in 30 OECD countries. In using this approach, the analysis sheds light on geographic differences in the share of workers in jobs with green tasks that directly relate to reducing greenhouse gas emissions or improving environmental sustainability. Furthermore, it offers a close link to labour market policies because it provides information on the skills, education, or gender of workers in those jobs and can help inform re-training and up-skilling programmes.

Introduction

Climate change and environmental degradation are among the most formidable challenges the world faces that will change how we live, work, produce and consume. Leading scientists have pointed out the risk of exceeding environmental tipping points, i.e. critical thresholds at which a tiny disturbance can alter the Earth’s climate system (Lenton et al., 2008[1]). Surpassing such tipping points could expose the world to long-term irreversible changes, with potentially dramatic consequences for lives and livelihoods globally. Consequently, “the growing threat of abrupt and irreversible climate changes must compel political and economic action on emissions” (Lenton et al., 2019[2]) (OECD, 2022[3]). Environmental policies and regulation that support the transition to a net-zero economy will lead to changes in industrial production, consumption patterns and energy provision. They will also require a transformation across every industry in the economy, ranging from production processes and innovation to the adoption of new technologies and investments.

Climate action and policy will need to contribute to a “greening” of the labour market, which has four major labour market implications. First, it will lead to the creation of new types of jobs. Second, it will entail the loss of some existing, “old” jobs. Third, it will cause a shift in the skills required in many jobs in the economy. Fourth, the green transition has a strong local angle. Risks and challenges in terms of jobs are uneven and are often concentrated in specific regions. Economic opportunities and job creation, likewise, will not materialise everywhere, with some places likely to benefit more than others from the shift towards carbon-neutral and environmentally friendly jobs and sectors.

Despite the fundamental changes that the green transition will bring about for labour markets, there is a lack of systematic evidence on the green transition’s impact on local labour markets. Existing work is often either very descriptive or qualitative. Most analysis has focused on the risks of the green transition (e.g., job losses) while its opportunities remain an under researched topic and is often limited to only a handful of sectors (e.g., agriculture, renewable energy or carbon-intensive industries) or a few specific jobs. The discussion has yet to cover the full picture, because green jobs and green skills extend beyond those subsets of sectors or jobs. Finally, most existing work on green jobs focuses on national level analysis and therefore does not identify any of the (potentially significant) geographic discrepancies within countries.

This chapter fills that gap and provides an overview of analytical work on the green transition’s labour market effects and local implications. It explains different approaches of assessing the opportunities and challenges that the green transition poses for workers, firms, sectors, and local economies. It summarises the main existing evidence on the impact of green policies on jobs in different communities. Finally, it sheds light on what we know and what we do not (yet) know with respect to the uneven effects of the green transition.

The push for green growth

What are OECD governments doing to support green growth in general?

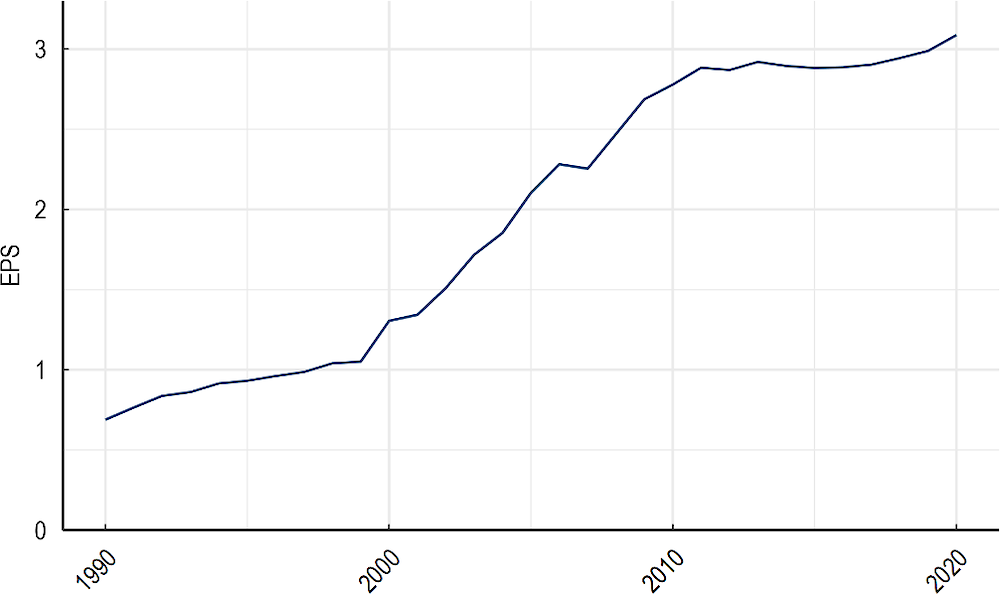

In most OECD countries, policies on environmental change have been on the political agenda for decades but policy actions to address the labour market implications of environmental policies are more recent. Over the last 30 years, the stringency of environmental policies related to air pollution, energy and carbon emissions in OECD countries increased significantly (Figure 1.1) — particularly between 2000 and 2010. However, until recently, many of those programmes included only limited direct labour market support despite a general expectation that green policies and stricter environmental regulation will affect the labour market. A number of new initiatives put a stronger focus on labour market aspects.

Figure 1.1. Environmental Policy Stringency across the OECD, 1990-2020

Note: The figure shows the OECD Environmental Policy Stringency (EPS) indicator for the OECD average. The OECD EPS average is an unweighted average across 28 OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Kruse et al., 2022[4]).

Advanced economies around the world have recently passed major policy packages for supporting the green transition and generating green economic growth. The European Commission’s European Green Deal (EGD) calls for all EU countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 by 55% compared to their levels in 1990 and aims to support EU member countries by mobilising more than EUR 1 trillion to finance the transition (Box 1.1). In the United States (US), the Inflation Reduction Act provides USD 369 billion for climate and clean energy, making it the single largest climate investment in US history (Box 1.2).

Box 1.1. The European Green Deal and Just Transition Mechanism

The European Green Deal

The European Green Deal (EGD) consists of three pillars: (i) net zero emissions by 2050, (ii) economic growth decoupled from resource usage, and (iii) leaving no person or region behind (EU green deal). Furthermore, it calls for all EU countries to reduce, before 2030, greenhouse gas emissions by 55% compared to their levels of 1990. To achieve these goals, the EU relies upon two transitions: decarbonising and digitalising Europe’s economy. The deal itself is not legislation, it is a roadmap including approaches and legislation that the EU needs to pass to become more sustainable.

The EGD aims to mobilise EUR 1 trillion to finance the transition. Half of this money is from the EU budget, the other half consists of mobilising private and national capital, which will be incentivised through the creation of new business opportunities. Nextgen EU, the European Covid recovery package was negotiated to also follow the Green Deal as a guideline. As a result, the total funding available now amounts to EUR 1.75 trillion. With the inclusion of this new fund, the talk of the Green Deal has shifted to a framework of a Green Recovery.

The European Green Deal is, first and foremost, an industrial blueprint. However, it also includes a biodiversity strategy and the promotion of green agricultural practices as a guideline on agricultural spending, under the Farm to Fork initiative. Furthermore, it will provide extra funding for regions where job losses are likely, through the Just Transition Mechanism.

The Just Transition Mechanism

The Just Transition Mechanism is a key tool in the European Green Deal that aims at making the transition towards a green economy inclusive and equitable under the slogan “leaving no one behind” (EU official website). The Mechanism aims to raise EUR 55 billion divided over three pillars:

The Just Transition Fund is the largest pillar of the mechanism and currently mobilises EUR 19.2 billion which is expected to rise to EUR 25.4 billion between 2021-2027. The fund sets out to alleviate the socio-economic costs associated with the climate transition, supporting economic diversification and increased resilience of territories most at risk of negative economic impact. This includes investments in SMEs, the creation of new firms, R&D, clean energy, environmental rehabilitation, up- and reskilling of workers, job-search assistance, and active labour market policies. The Fund aims to foster cooperation at the regional level by giving regions and local communities a voice in spending the money.

The InvestEU Just Transition Scheme will provide a budgetary guarantee across four policy windows: (i) sustainable infrastructure; (ii) research, innovation and digitisation; (iii) small and medium-sized businesses; (iv) and social investment and skills. Furthermore, the InvestEU Advisory Hub will act as a central entry point for advisory support requests. It expects to mobilise EUR 10-15 billion in mostly private sector investments.

The Public Sector Loan Facility will combine EUR 1.5 billion in grants financed from the EU budget with EUR 10 billion in loans from the European Investment Bank, to mobilise a total of EUR 18.5 billion in public investments.

Source: EU green deal: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en#timeline; Euractiv: https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/brussels-postponed-green-finance-rules-after-10-eu-states-wielded-veto/

EU official website: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism_en

Box 1.2. The US Inflation Reduction Act

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 aims to raise tax revenue and use the resources for inflation reduction and green investment. It is a fiscal policy that will increase tax revenue and spend it to both lower inflation and boost green investment. To raise the tax base, the US Biden administration is planning to target corporations and higher income households, by increasing taxes and closing tax evasion loopholes. By increasing the corporate minimum tax to 15%, USD 313 billion will be raised. Another USD 288 billion will be raised by prescription drug price reform. Furthermore, USD 124 billion will come from IRS Tax enforcements, and USD 14 billion from changing carried interest loopholes. In total, USD 739 billion will be raised. Of the new revenue, USD 64 billion will be allocated to continue the Affordable Care Act and USD 369 billion for Energy Security and Climate Change. The remaining amount is used to reduce the budget deficit and combat inflation.

The USD 369 billion set aside for energy and climate change is used to finance the US government goal of a 40% emission reduction in 2030 compared to 2005 and enhance energy security. In the spending on energy security and climate neutral technology, emphasis is put on the national labour effects of funding. The goal is to make the US a world leader in clean energy technology, manufacturing, and innovation, powered by American workers. Special attention is given to historically underserved communities and the act prioritises creating shared prosperity to make the US more resilient. It offers options to distribute extra funds for initiatives located in economically distressed regions or traditional energy communities. Such projects are required to pay prevailing wages, hire apprentices, and to include persons who have been out of the labour market. The Act will also be led in conjunction with the Justice40 initiative, which requires 40% of investment to benefit the climate, clean energy, and marginalised communities that are overburdened by pollution. Furthermore, the US government will use the funds to facilitate local contracting opportunities for underserved small businesses. Finally, investment in both energy and traditional infrastructure should lead to an increase in high-quality union jobs for middle class workers.

Given the urgency of addressing the climate emergency, these green policy packages are unprecedented in size and ambition. They entail multiple objectives. They aim to facilitate the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and ease the reliance on fossil fuels. At the same time, they aim to boost sustainable economic growth that benefits all, ensuring a just and inclusive transition. For example, the European Commission emphasises the importance of focusing on “the regions, industries, workers, households and consumers who will face the greatest challenges in terms of employment, social and distributional impacts when decarbonising their economy” (European Commission, 2021[5]).

COVID recovery packages provide new impetus for the green transition but also need to consider local labour market implications

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, most OECD governments passed large-scale economic measures, often including green recovery measures. Green policy measures account for a significant proportion of the recovery packages so far passed in 44 countries, consisting of OECD countries, EU countries and selected large economies (see Box 1.3). Spending on green recovery measures in those countries and the European Union totalled USD 1 090 billion by April 2022. Thus, spending on green recovery measures rose by more than USD 400 billion compared to September 2021.1 At the same time, however, some governments also introduced COVID-19 recovery measures that will have a negative or mixed impact on the environment.

Box 1.3. Green recovery measures

The OECD Green Recovery Database tracks recovery measures adopted by OECD member countries, the European Union and selected large economies and their environmental impact. Between the onset of the pandemic and April 2022, total recovery spending in those countries exceeded USD 3 300 billion (OECD, 2022[6]).In assessing the environmental implications of recovery-related policies and measures, it classifies each measure as having positive, mixed, negative or indeterminate environmental implications (OECD, 2021[7]).

Table 1.1. Environmental Categories in the Green Recovery Database

|

Description |

Examples |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Positive |

The measure has clearly discernible positive environmental impact for one or more environmental dimensions, without any clearly discernible significant negative impacts on other environmental dimensions. |

Investment commitments for renewable energy; support for innovation targeted to clean technologies; measures for improved forest management, regulatory changes that strengthen the investment case for cleaner technologies |

|

Negative |

The measure has clearly discernible negative impacts on one or more environmental dimensions, without any clear positive environmental impacts. |

Rollbacks of environmental regulations; investment commitments for emissions-intensive fossil-fuel projects |

|

Mixed |

Both positive and negative environmental impacts are clearly discernible. This can happen either i) where the measure has clear positive environmental benefit on one dimension, but has clearly significantly negative impacts on at least one other dimension; or ii) where the measure is very broad and contains some elements that will have strong positive implications but other elements that are likely to have clear negative implications (whether for the same environmental dimension or another) |

Examples of (i) include biofuel investments without safeguards, which may have impacts on biodiversity and lead to indirect GHG emissions from land-use change; a broad infrastructure investment plan that includes both renewable energy and carbon-intensive infrastructure |

|

Indeterminate |

The measure does not have clearly identifiable environmental implications at the level of assessment carried out for this exercise. This does not mean that the measure is environmentally benign, just that the impacts are difficult to determine. Many countries’ stimulus measures could be considered indeterminate but not all are captured in the Database (full tracking of all stimulus measures was not the purpose of this Database nor within the mandate of the OECD Environment Directorate). Measures tagged indeterminate have been excluded from the analysis, to avoid introducing unnecessary bias |

Support for small businesses with no particular green focus; increased welfare support for vulnerable families; |

Source: (OECD, 2022[6]).

Despite their importance, only a very limited number of measures are directed at areas that will support the development of “green” skills. The green COVID recovery programmes mainly reflect broader grants, tax reductions/other subsidies, and regulatory changes. In contrast, a relatively small share of measures are directed at two areas that are essential for the creation of green jobs and the provision of workers with the right (“green”) skills for the green transition: 8% promote research and development (R&D) and 2% relate to skills development.

Skills development and retraining are vital to ensuring that workers have the right skills to prosper in a changing world of work and are a prerequisite for making the green transition a “just transition”. Many workers in polluting jobs or sectors will require targeted support so that they can move into new jobs, greener sectors or retrain if the requirement of their jobs change as polluting sectors green. Indeed, even without the changes the green transition will entail for jobs and skills, many OECD countries already experience skills gaps and mismatches as obstacles to economic growth and productivity gains (OECD, 2021[8]).

The limited number of green measures on skills development is even more striking in terms of committed funding and subnational focus. Around USD 15.6 billion of the total funding of USD 1 090 billion are allocated to skills training.2 While skills gaps and mismatches affect most OECD economies, they differ substantially within OECD countries. Thus, training needs and the challenges of developing skills for the green transition must take into account local challenges and conditions (OECD, 2018[9]). For example, designing skills training with a subnational lens can yield a more effective matching with the demand for skills and jobs by employers in a local economy (OECD, 2022[10]). However, as a percentage of all recovery funding, skills training at the subnational level is considerably less than 1% (0.0024%).

What we know (and don’t know) about the impact of green policies on employment and local implications

Green policies and environmental regulation can affect the economy in many ways. Empirical analysis has so far focussed on their impact on economic growth, labour productivity, investments, technology adoption, firm performance, international trade, and the demand for skills (Box 1.4).

An outstanding, and politically sensitive, issue is the impact of environmental policies on employment, particularly the differential impact across communities. So far, the evidence on whether green policies lead to job losses or gains is mixed and suffers from considerable evidence gaps and depends on the impacts on the economy more generally (Box 1.4). A number of studies find negative employment effects of environmental regulation, particularly for energy-intensive industries (Walker, 2011[11]), (Greenstone, 2002[12])), while other works suggest there is a relatively small effect on overall employment ( (Gray et al., 2014[13]), (Brucal and Dechezleprêtre, 2021[14])). Evidence on fiscal stimulus packages shows that targeted green investment stimulates significant employment creation, especially of green jobs (Popp et al., 202[15]).

Even if the employment effects of green policies have a small impact at the national level, they may have a strong localised impact. As a result of the reallocation of workers from energy-intensive (or polluting) to non-energy-intensive (non-polluting) sectors, regions that specialise in the former are likely to bear, at least in the shorter term, a greater share of the labour market costs of environmental policies. For example, while a 10% increase in energy prices leads to a reduction of manufacturing employment by 0.7%, this reduction reaches 1.9% for energy-intensive sectors such as iron and steel production (Dechezleprêtre, Nachtigall and Stadler, 2020[16]).3

Box 1.4. Impacts of green policies on the economy

Recent OECD analysis provides an overview of how green policies affect economic performance (OECD, 2021[17]). Drawing from empirical OECD research over the past decade across countries, it finds little effect of more stringent environmental policies on economic performance overall, although they result in clear environmental benefits. However, little is known about the local effects of green policies. Evidence on green policies’ impact on the economy is extremely relevant, as the public discourse on environmental policies often entails emphasis on possibly negative effects on the economy. Furthermore, public support for environmental policies hinges on the perception of not only their environmental benefits (see (Dechezleprêtre, Nachtigall and Venmans, 2018[18]) and (Dussaux, 2020[19])) but also their economic benefits and costs.

Overall, environmental policies have a diverse effect on firm or industry performance. For example, the effects on firm and industry productivity vary according to the technological advancement of sectors and firms (Albrizio, Koźluk and Zipperer, 2017[20]). Industries that are close to the technological frontier record productivity growth increases in response to more stringent environmental policy. Among firms, more stringent environmental policy leads to higher productivity growth of technologically advanced firms but to a decrease in productivity growth for firms further away from the technology frontier. Environmental policies also influence firms’ investment decisions. For example, analysis of the balance sheets of listed companies in the manufacturing sector across 75 countries shows that higher energy prices are associated with lower domestic investment but with a rise in foreign direct investments (FDI) of firms in energy-intensive sectors (Dlugosch and Kozluk, 2017[21]). Changes in relative energy prices appear to pivot firms to shift investments abroad (Garsous, Koźluk and Dlugosch, 2020[22]).

A major concern for policy makers is that strict environmental regulation can harm firms’ international competitiveness. In the aggregate, environmental policies do not appear to affect international competitiveness. OECD analysis of 23 countries and 10 manufacturing industries finds no large effect on international trade or the domestic value added embedded in exports (Koźluk and Timiliotis, 2016[23]). However, as with productivity, there appear to be winners and losers. In response to more stringent environmental policies, exports of lower-pollution sectors increase whereas exports of pollution-intensive sectors decrease.

The main body of work on green policies and employment has two major caveats. First, it lacks analysis of the geographic impact, i.e., the uneven effects. Second, it does not offer insights into how green policies change the composition of jobs in a labour market, which matters for a range of policies such as education, adult learning, vocational training, or active labour market policies. Even though the consensus is that job losses and job creation due to green policies and the green transition overall will not necessarily be evenly spread across different places, most existing work does not investigate the different impact across places within countries (OECD, 2017[24]). This matters even more because labour is relatively immobile in the short run, so that those risks of green policies can result in a rise in local unemployment and relevant adjustment costs in areas affected the most (Valero et al., 2021[25]). A just transition requires not only better understanding the spatial impact of green policies, but also their distributional consequences for different workers, which can then inform policy responses that help support workers negatively affected or in risk of displacement.

The quest for better data on jobs created by and at risk from the green transition

As highlighted for G7 environment ministers, more quantitative evidence on the employment effects of green policies is needed (OECD, 2017[24]). Better and consistent data play a vital role in filling evidence gaps across multiple dimensions, including numbers and characteristics of jobs that might be created or destroyed as well as estimates of the number of workers who will need to transition into different sectors or occupations. Additionally, effective policy design requires knowing whether those workers possess the skills and competencies required in newly created jobs or how they can re- or upskill to meet those requirements.

Subnational data are critical. Most of the existing evidence on the link between green policies and employment focuses on aggregate, national information. However, when it comes to employment effects, green policies inevitably have a spatial impact. They will affect particular jobs and industries, especially those with greater pollution intensity, the most. As those jobs are not evenly spread out but often concentrated in specific areas, the challenges in terms of employment loss or changes in job requirements will also differ markedly within countries. Likewise, the opportunities that green policies present for job creation and green economic clusters also require a local perspective.

These data are also essential to deliver the green transition in the first place, as a lack of “green” talent can hold back the green transition. Across the OECD, companies face unprecedented labour shortages (OECD, 2022[26]). For example, in the European Union, almost 30% of firms in both manufacturing and services encountered production constraints in the second quarter of 2022 because of a lack of labour. In the United States, the number of vacancies is almost double that of unemployed persons. Those labour shortages are exacerbated by widespread skills mismatches, which make it hard to fill vacant positions with unemployed individuals. To mitigate labour shortages and skills mismatches for green industries and firms, policy makers need to know what skills and tasks green jobs entail before they can effectively design policy.

The lack of consensus on measuring green jobs is a major reason why the evidence on job creation by green policies varies widely. Different studies and institutions use different approaches, which makes it hard to assess the impact of green policies consistently across countries. Comprehensive and solid evidence with comparable data is needed for designing and evaluating green policies that support the creation of green jobs. Additionally, data and evidence on polluting jobs and how they are affected by green policies is important for policy.

Lack of clarity and consensus on what “green” jobs are

Despite the fundamental changes the green transition entails for labour markets, there is not yet a universally accepted definition of what a green job is. Thus, different studies have come to different conclusions about the proportion of green jobs in the economy or green job creation (Bowen and Kuralbayeva, 2015[27]).4 Consequently, it is difficult to compare studies on the magnitude of green job creation or the relative importance of green jobs in the labour market. Additionally, most work until now has focussed on single or a narrow set of countries.

Across international organisations and national governments, definitions of green jobs vary. The United Nations defines green jobs as jobs in sectors that contribute substantially to preserving or restoring environmental quality and minimise waste creation and pollution (UNEP, ILO, IOE, ITUC, 2008[28]). The ILO defines green jobs as “decent jobs in any economic sector (e.g., agriculture, industry, services, administration) which contribute to preserving, restoring and enhancing environmental quality.” Thus, the ILO’s definition combines two criteria. First, green jobs help ‘reduce the environmental impact of enterprises and economic sectors by improving the efficiency of energy, raw materials and water; de-carbonise the economy and bring down emissions of greenhouse gases; minimise or avoid all forms of waste and pollution; protect or restore ecosystems and biodiversity; and support adaptation to the effects of climate change’ (ILO, 2022[29]). Second, the ILO includes a social component, referring to ‘decent’ jobs that are productive, secure and deliver a fair income, among other things.

Other international organisations refer to skills as a means of defining green jobs. For example, the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) defines green skills as “the knowledge, abilities, values and attitudes needed to live in, develop and support a sustainable and resource-efficient society” (OECD/Cedefop, 2014[30]). Then, green jobs are those that require green skills. Another possible way of defining green jobs is to first determine what the green economy is and then include those jobs are part of it (see Box 1.5). These definitions are relatively broad and not operationalised, i.e., systematically applied to available data across the world.

Box 1.5. The green economy – definition by the ILO

What is meant by the green economy?

There is no unique definition of the green economy. The main characteristic of the concept is the acknowledgment of the economic value of natural capital and ecological services and the need to protect those resources. Most definitions include not only environmental aspects but incorporate the more holistic approach of sustainable development. Environmental sustainability, social justice and locally rooted production and exchange of goods and services are therefore elements that can be found in most green economy definitions. The United Nations Environment Programme defines a “green economy as one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. In its simplest expression, a green economy can be thought of as one which is low carbon, resource efficient and socially inclusive.”

Source: ILO, Frequently Asked Questions on green jobs (ilo.org).

The vast majority of the empirical literature draws on two dominant approaches to quantify green jobs (Figure 1.2). The first type consists of top-down approaches that identify sectors or industries that are green and consider that all employment in those sectors or industries is green. The second type, i.e. bottom-up approaches, exploits information on occupations. They define green jobs based on the skills or tasks different occupations entail and the extent to which those tasks or skills are green (for a more detailed discussion of the different approaches see (Valero et al., 2021[25])). A third strand of macro-modelling approaches does not explicitly measure the number or location of green jobs but can provide an important overall assessment of the impacts of environmental policies on the labour market.

Figure 1.2. Defining green jobs: top-down and bottom-up approaches

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The fact that there is no universally agreed definition creates a number of challenges. First, it causes some research to avoid the term completely (Bowen and Kuralbayev, 2015[31]). Second, it makes it extremely difficult to compare different studies, which differ with respect to the countries, parts of the economy and time frame they cover. Thus, studies that include estimates of the share of green jobs in the labour market come to widely different conclusions (Table 1.2). Those estimates range from 2% (Eurostat, 2022[32]) to 40% (Bowen and Hancké, 2019[33]).

However, data and statistics on the relative importance of green jobs and their characteristics are crucial for policy and supporting the green transition. They provide an understanding of the magnitude of the labour market implications of the green transition and environmental policies, and can give a sense of pending structural changes to local and national economies. Furthermore, such statistics are required for an effective design and evaluation of labour market and skills policies. This is particularly important in the current context, with widespread skills and labour shortages, which raise an important question for policy makers: Do we have enough green talent? Amid prevalent skills shortages, notably for skills required the most in green jobs, the job creation potential of green sectors and industries might not be fulfilled (ILO / CEDEFOP, 2011[34]).

Table 1.2. Estimates of green jobs differ widely across studies

|

Study |

Green job estimates |

Country (coverage) |

Time period |

Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2%; 4.4 million full-time equivalent jobs |

EU-27 (cross country) |

2019 |

Environmental Goods and Service Sector |

|

|

1.24 million full-time equivalent jobs |

EU |

2021 |

Renewable Energy Employment |

|

|

1% (of non-financial employment) |

United Kingdom |

2020 |

‘Top-down’: Industry based (low carbon sectors) |

|

|

17-39% |

United Kingdom (economy wide) |

2011-2019 |

Task-based, O*NET; Occupation based |

|

|

20% |

Former EU15 countries |

|||

|

40% |

EU-28 (cross country) |

2006-2016 |

Task-based, O*NET; Occupation based |

|

|

3.8% Canada (economy wide) |

Canada (economy wide) |

2020 |

‘Mixed’: Occupation and industry based (EGSS) |

|

|

around 30% |

Netherlands |

2006-2008 |

Task-based, O*NET; Occupation based |

|

|

3% green intensity of employment (employment-weighted share of green tasks in the economy) |

US metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas |

2006 and 2014 |

Task-based, O*NET; Occupation based |

|

|

Around 19.4% (direct and indirect green jobs) |

US |

2014 |

Task-based, O*NET; Occupation based |

To better understand why the existing work on green jobs produces wildly different estimates, the subsequent sections review top-down and bottom-up approaches of defining green jobs as well as more general macro-modelling forecasts. Those sections explain some of their advantages, limitations, and the assumptions they entail for understanding why policymakers sometimes choose particular approaches in line with specific policy objectives and how, in the end, those approaches are complementary (Martinez-Fernandez, Hinojosa and Miranda, 2010[42]).

Top-down approaches

Top-down approaches have in common that they classify green employment based on the production process and/or outputs. For example, a sector could be classified as green based on its output, and thus all employment (regardless of the occupation) in that sector would be considered green. Prominent cases of such sector-based definitions include, for example, estimates for the renewable energy sector. In practice, empirical studies adopting this approach tend to make use of existing sector and/or industry classifications. This, coupled with limited data availability, nudges studies towards measuring employment in certain sectors (as defined by a standard classification) of the economy first, and then refining their estimates, depending on the resources available. However, top-down approaches could also generally consider areas of the economy that produce environmental goods or services, and therefore include industries from different sectors.

Top-down approaches can vary significantly in their estimates and in the breadth of their analysis. For example, a recent report on renewable energy estimated that the sector provides around 1.24 million full-time equivalent jobs in the EU (IRENA and ILO, 2022[36]). Broader definitions often consider a larger set of activities, also referred to as the environmental goods and services sector (EGSS), which comprises industries centred on environmental activities, i.e. activities that either directly serve an environmental purpose or produce goods that are specifically designed to serve an environmental purpose.5 In the EU, estimates find that EGSS accounts for 4.4 million full-time equivalent jobs, or 2% of total employment (Eurostat, 2021[35]). The EGSS is a leading example of the top-down approach, and it is therefore relevant to describe it in more detail.

Box 1.6. Employment estimates in renewable energy

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) provides estimates for the number of jobs in different renewable energy technologies across the world. Data for Europe relies on statistics by EurObserv’ER. The latter is a project that aims to provide technical support to the European Commission when monitoring the renewable energy sector and sources.

EurObserv’ER employs a so-called ‘follow-the-money’ approach to estimate employment across different technologies of the renewable energy sector (RES). To address the lack of official employment data for renewable energy (a subsector of energy), they use a common methodology in calculating the effect of RES deployment on employment and revenues, enabling a comparison between Member States and different renewable energy technologies. They use data on newly installed capacity, operation and maintenance cost and biomass feedstock cost for 11 sub-sectors related to renewable energy, which are translated into employment numbers using detailed information on average labour costs. However, this approach is limited to national level data.

Source: EurObserv’ER (2019), The State of Renewable Energies in Europe. 19th EurObserv’ER Report. https://www.eurobserv-er.org/19th-annual-overview-barometer

Environmental Goods and Services Sector

This top-down approach aims to quantify employment (and other measures such as GDP, GVA and exports) on the environmental goods and services sector (EGSS). It builds on the UN System of Environmental-Economic Accounting Central Framework (see Box 1.7). EGGS revolves around the concept of environmental activities, including examples such as the manufacturing of bio-fuels, installation of photovoltaic panels, or environmental consulting services. The EGGS includes the set of producers who engage in environmental activities, such as environmental protection activities, aimed at reducing and preventing greenhouse emissions or other harmful environmental impacts, and resource management activities related to energy.

A core challenge of this approach is that producers may engage in secondary activities, which may or may not be environmental. Ideally, those secondary activities should be separated and classified accordingly. However, in practice this is not always possible given the data limitations. In the end, it is up to countries to decide how and if to separate secondary activities, which might weaken comparability across countries.

Results for this approach show that the size of the green labour market is small, around 2.2% of the jobs in the EU in 2019 were in the EGSS. Within the EU, there is some dispersion across countries, but the share of green jobs remains low, ranging from 0.9% in Belgium to 5.1% in Finland. Although the EGSS labour market has grown faster than the total labour market since 2000 (43.3% for the former and 11.7% for the latter), the growth in the proportion of jobs in the economy has been limited to 0.5 pp (from 1.7% to 2.2%). In addition, 97% of growth in the proportion of EGSS jobs was between 2000 and 2011, with little growth over the last decade.

This framework also requires that each country develop its own environmental statistics. Ideally, each country would follow the same methods and definitions, but inevitably, discrepancies in the process exist. The work done by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) is a useful example of the EGGS in practice. ONS follows the definitions provided by the EGSS and applies them using a variety of sources such as the Low Carbon and Renewable Energy Economy (LCREE) Survey, among others.

Box 1.7. UN System of Environmental-Economic Accounting Central Framework

The System of Environmental-Economic Accounting Central Framework (SEEA Central Framework) conceived and maintained by the United Nations is a multipurpose conceptual framework that provides definitions and classifications compatible with existing data frameworks that aim to place “… statistics on the environment and its relationship to the economy at the core of official statistics”.

This method is not directly constructed to measure employment, but rather other stocks and flows. Such information can then be related to employment estimates using, for example, supply-use, input-output tables, or asset ratios. For example, employment in renewable energy can be hard to estimate as the renewable energy sector is usually not classified as a distinct sector in national sector classification systems such as the UK’s SIC or the European NACE. The closest classifier in this case is “production of electricity” (SIC 35110 and NACE 35.1.1). Employment in the renewable sector can then be estimated as a proportion of employment in this sector, using for example information on total and renewable energy generated as well as employment productivity estimates. However, this assumes that productivity is the same across different electricity generation methods.

Individual countries are responsible for compiling and publishing their environmental accounts. In practice, this means that national statistical offices or similar administrative units are in charge of interpreting the framework in order to tailor it to their local situation, which may differ from other countries in terms of data available, employment or sector classifications and statistical units, among others. One practical example of an economic area applying the SEEA Framework is the Environmental Goods and Services Sector Accounts put forward by the European Commission (Eurostat, 2016[43]).

Source: UN. (2014). System of Environmental-Economic Accounting 2012. https://seea.un.org/content/seea-central-framework

Since 2014, the UK’s ONS has compiled data on the LCREE. The data are derived from survey-based estimates of turnover, exports, employment and acquisitions and disposals of capital assets in 17 low-carbon sectors6. This is part of a broader program by the ONS that compiles information on Environmental Accounts such as natural capital, atmospheric emissions, and energy use. Businesses are considered to be part of the LCREE if they report activity in one of 17 defined sectors.7 Results show that for 2020, employment in the LCREE was around 207 800 full-time equivalents (ONS, 2020[37]).8

In short, LCREE and EGSS have the same objective, but the former serves as an input for the latter as the EGSS has a broader focus. LCREE does not include some "green" activities, such as recycling and the protection of biodiversity.9 Furthermore, EGSS, uses a combination of other surveys, supply-use/input-output tables, and other complementary data to provide estimates in line with international guidelines.

Advantages and limitations of the top-down approach

Advantages:

Ease of interpretation: It is easier to interpret if the primary objective is industrial analysis, and, depending on the information systems available in the country, may provide details on specific activities that are not typically identifiable in Labour Force Survey data (the primary source for the bottom-up approach), as they are less detailed than the most detailed industry classifications.

Limited data collection needs: Given that quantifying employment using the top-down approach is a spin-off of quantifying GVA, import and exports (national accounts), a lot of the data is already collected. New data collection requirements are limited.

Ancillary green jobs: Because the approach captures all jobs engaged in a certain activity it also captures jobs in the ‘green’ firm, that may not in and of themselves be considered green but, rather, support green activities. However, at the same time, as shown below this can also generate challenges with comparability depending on the degree of outsourcing a firm may engage in.

Limitations:

Statistical unit: A key difficulty with the top-down approach is the choice of statistical unit. The preferred choice would be the Local Kind of Activity Unit used in the European Statistical System or the Establishment used in the international system but in practice many countries use other measures of statistical units, such as the enterprise, and commonly legal units, which can impair international comparability. In addition, the choice of enterprise for example can also create challenges for estimating sub-national breakdowns as it may assume similar production activities across all regions where the parent has operations.

Limited subnational data availability: A key caveat of most top-down approaches is that data are not reliable enough to construct sub-national estimates. National data might, however, obscure potential regional differences that may be relevant.

Jobs unrelated to green activities may still be considered green: As all jobs in the sector are included, estimates inevitably include jobs that are only indirectly related to the underlying green activity. A clear example of this is ancillary activities, accountants or security guards for example, who will be classified as green as long as their statistical unit is deemed to have an environmental purpose. Indeed, the argument that all jobs engaged in the ‘green’ firm should also be included creates an argument that all upstream jobs (including in non-green activities) should also be included.

The approach is affected by market structure: The degree of jobs that are considered as being in green activities are also dependent on the market structure of the economy given the varying degrees of outsourcing firms may engage in. For example, if a company in the recycling industry that has an accounting department decides to outsource that department, then those employees (previously considered to be in green jobs) would no longer be part of the estimates of green jobs if they were integrated by a third-party company fully dedicated to accounting. Such issues could lead to unstable results that may be impacted by arbitrary changes in the production structure.

Box 1.8. Using sectoral data to identify vulnerable regions in the industrial transition to climate neutrality

Manufacturing activities are some of the most difficult to make climate neutral. Using sectoral information on employment and emissions data for firms, a new OECD report identifies regions that are particularly vulnerable in the industrial transition to climate neutrality (OECD, 2023[44]). Manufacturing sectors are regionally concentrated, hence sectoral transformations will have place-based implications. The transition will require more investments in new forms of production and new energy carriers.

The report identifies six manufacturing sectors as facing particularly large transformation challenges:

Coke and oil refining,

Chemicals,

Basic metals, in particular steel and aluminium,

Non-metallic minerals, in particular cement,

Paper and pulp,

Motor vehicles.

The six sectors above generate some of the highest emissions in manufacturing and are the most energy intensive, requiring them to profoundly transform their production process.

Regional transformation challenges are likely to be largest where both employment shares in pollution-intensive sectors and emissions per capita are high. Employment shares in those six manufacturing sectors are calculated using 2-digit NACE sectors for large regions (NUTS 2) provided by Eurostat Structural Business Statistics (SBS). To calculate emissions per capita, facility emissions data from the European Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is matched to firm level data from ORBIS. This makes it possible to identify the 2-, 3-, and 4-digit NACE sectors for large regions (NUTS 2) and small regions (NUTS 3) where the companies own facilities.

Regions with a high employment share in those polluting manufacturing sectors will have to decarbonise production assets, while at the same time capitalising on opportunities and addressing challenges for workers to achieve a just transition. Regional transition requires new infrastructure and technologies. However, regions’ ability to access this infrastructure differs. Most of the infrastructure needed, such as hydrogen transported via pipelines, is subject to economies of scale. Hence, regions with clustered production sites, such as the chemical industry in Belgian and German regions, will face lower costs than dispersed ones.

The socio-economic characteristics of regions, workers, and firms also impact the risks faced by regions. Most of the exposed regions already have low GDP per capita and wages, and the workers could face skills gaps and/or job and income loss. The regions also do not seem to be attractive to workers or firms, which makes it more difficult to diversify the economy. Additionally, the regions with less productive firms may also face greater risks, as those firms may find it hard to incorporate technological transformations.

Source: (OECD, 2023[44]).

Bottom-up approaches

Bottom-up approaches of defining green jobs are based on information from individual occupations. They classify occupations based on their characteristics and the work they entail (Table 1.3). Quite common among these approaches is identifying green jobs based on the tasks they require and the extent to which those tasks are green (i.e., they support environmental objectives). Alternatively, green jobs can also be determined by defining specialised green skills and examining the jobs that require them. Finally, as pointed out above, some organisations also include a ‘decent job’ requirement as a condition for a job to be green.

Table 1.3. Main bottom-up approaches to define green jobs based on job characteristics

|

Description |

|

|---|---|

|

Tasks |

Occupations are analyzed, irrespective of the sectors in which they are located. The greenness of occupations is drawn from the greenness of the related task content of a job. |

|

Skills and abilities |

Certain jobs require workers to possess certain specialised green skills. |

|

Job decency |

The UNEP and the ILO have both stressed the fact that “green” jobs need to be decent jobs, i.e., good jobs which offer adequate wages, safe working conditions, job security, reasonable career prospects, and worker rights. |

Task-based approach in theory

Most studies to date that take a bottom-up approach follow the methodology proposed by (Vona et al., 2018[45]). Their work rests on the fact that each occupation can be divided into different functions, called tasks, which may be carried out daily, monthly or even on a yearly basis. Therefore, each occupation can be divided into a unique set of tasks. Occupations can then be analysed and categorised based on the content of these tasks.

The task-based approach is the dominant approach in labour economics for studying the labour market impact of structural transformation. Pioneering contributions include work by David Autor and co-authors ( (Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003[46]), (Autor, 2013[47])), who assessed the impact of computers and digital technologies on the labour market, as well as (Acemoglu and Autor, 2011[48]) and (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2018[49]), who provided further theoretical consolidation/confirmation of the approach by examining the effects of automation and digitalisation.10

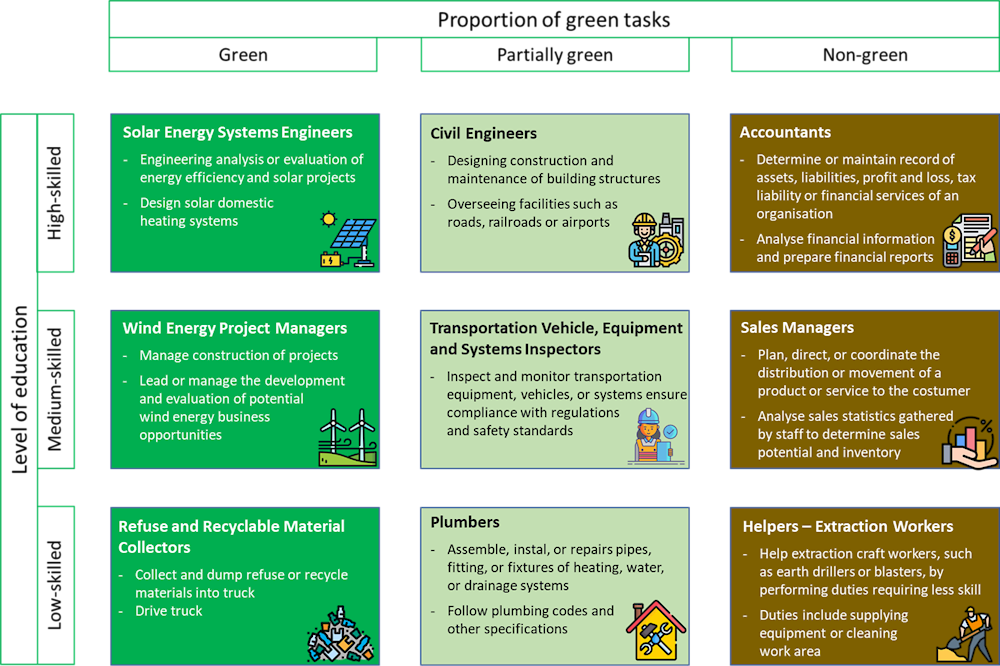

While different sources can be used to retrieve information on occupations, the most widely used source is the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) of the U.S. Department of Labor. Through a mixture of direct surveys, occupational expert consultation and case-by-case analysis, O*NET (see Annex for further details) provides information on a large number of occupations and the tasks they entail, the relative importance of those tasks and the skills generally required to fulfil those tasks (Dierdorff and Norton, 2011[50])11. While bottom-up approaches need not be task-based but could instead be, for example, skills-based, most research focuses on tasks. O*NET’s Green Economy Programme (Dierdorff et al., 2009[51]) provides a list of individual tasks for each occupation and classifies these tasks as green or non-green.12 Based on this information, an occupation can be classified according to the overall greenness of its tasks. The infographic below provides some examples of this.

Infographic 1.1. Green-task jobs can be found across the economy and skills spectrum

Note: The greenness of occupations is based on their task content and whether those tasks are green or not. The greenness score of an occupation ranges from 1 (all tasks are green) to 0 (all tasks are non-green). The classification of high-, medium-, and low-skilled occupations follows ISCO.

Source: OECD elaboration based on O*NET’s Green Tasks Data.

Task-based approach in practice

A number of academic articles and reports have used the task-based approach to examine the share of green jobs in the labour market and to shed light on the effects of the green transition. They combine information from O*NET with granular employment data in different economies. Vona et al. (2019[40]) examine drivers of green job growth in US metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas between 2006 and 2014 and is thus one of the first studies to examine spatial differences in terms of green jobs. They provide estimates of the green intensity of employment, which is the employment-weighted average of the greenness of tasks in a given local labour market (see previous section).13 The green intensity of employment can be broadly interpreted as the share of tasks or time spent on green activities. They find that the green intensity of employment is around 3%, although this ranges from 2.4 to 3.9 within the US. Although they find a convergence of green employment over time across the US, it remains geographically concentrated, especially in high-tech areas.

Recent analysis extended the scope to 34 countries, mainly consisting of more advanced economies in the EU, South Africa, Mexico and the US (International Monetary Fund, 2022[52]). It finds comparable green intensity of employment across the economies covered, ranging from about 2 to 3%. Additionally, the study examines the average employment-weighted pollution intensity of economies (see Measuring green jobs at the regional level for further detail), which ranges from 2% to 6%. The study finds that high-skilled urban workers are in occupations with a higher green intensity, which also comes with a wage premium. A second study adopted the same approach with a global perspective (IMF 2022). This study focuses on the green intensity of workers (i.e., the share of their tasks that are considered green). The work estimates that high-skilled urban workers tend to have a higher green intensity, and that this measure ranges from 2% to 3% in the economies they study.

A related body of work applies the task-based approach but looks at a different outcome, namely green jobs. Instead of examining the green intensity of employment, those studies use the same occupation and task classification provided by O*NET to identify green jobs as either those that entail any green task or include a significant proportion of green tasks. Valero et al. (2021[25]) consider not only workers who directly contribute to preserving the environment and reducing emissions, but also indirect green jobs, which are jobs that may not directly contribute but are expected to be positively impacted by the green transition through increasing demand. Overall, they find that around 17% of the jobs in the UK are either directly or indirectly green, and that the share of green jobs differs widely across sectors. Furthermore, they document that a disproportionately large proportion of green jobs are held by men and highly educated individuals.14 For the US, (Bowen, Kuralbayeva and Tipoe, 2018[41]) estimate that around 19.4% of workers are directly or indirectly employed in green jobs. In accordance with the other studies which consider the sub-national dimension, this study finds relevant differences across regions as the share of green jobs ranges from 13% to 25%. Finally, (Elliott et al., 2021[53]) study eco innovation and job creation within Dutch firms. Defining green jobs as those occupations with a greenness index (the weighted share of green tasks among all tasks of an occupation) greater than the average greenness index, they find that around 30% of jobs are green.

Advantages and limitations of the bottom-up approach

Bottom-up approaches, especially those based on tasks of occupations, offer a number of appealing features that might be particularly helpful for policy. At the same time, however, they also have a few limitations. Below is a short description of the most important aspects.

Advantages:

Subnational information: When detailed LFS data is available, computing sub-national estimates is straightforward as it does not require collecting extra data or further estimation compared to national estimates. This is particularly relevant for policy because, like other megatrends, the green transition will have different effects across different places.

Socio-economic information: Unlike most top-down approaches, task-based definitions enable detailed analyses of workers in green jobs and how their characteristics such as education, skills levels, gender, age or wages differ from non-green jobs. Thus, it can provide useful information on how the green transition might affect socio-economic disparities.

Link to labour market policy: A key implication of the green transition is that it will lead to a reallocation of jobs and a change of skills that are in demand. Occupational task-based approaches lend themselves to examining how workers can transition into new jobs or sectors through retraining or upskilling and can inform, with greater precision, skills and active labour market policies.

Coverage of green ‘activities across sectors’: Workers outside of sectors traditionally considered green can also contribute to net-zero and other environmental objectives. Task-based approaches are “sector-blind” and include all workers that support such objectives directly, for example researchers employed in high-emitting firms that are engaged in activities aimed at reducing, mitigating, or eliminating emissions.

Limitations:

Crosswalks and US-based tasks: O*NET task data were built in and for the US. Applying the concept of green tasks to occupations in other countries assumes that the same set of tasks are green in other countries and indeed at the sub-national level. Additionally, information on occupations’ tasks needs to be translated from the US occupational system (SOC) into the occupational classification systems of other countries. In practice, official crosswalks, i.e., mappings, are available. However, such crosswalks are not perfect for all occupations. For example, SOC-2010 occupations “Technical Writers” and “Writers and Authors” (SOC-2010 27-3042 and 27-3042 respectively) are both mapped to ISCO-08 occupation “Authors and related writers” (ISCO-08 2641) meaning not all matches are one-to-one.

Green tasks over time: O*NET’s Green Task Development Project offers a static picture of what green tasks are at a given time. It does not include information on how the set of green tasks has changed over time, nor does it claim that future green tasks will be the same.

Occupational employment data: Although data on occupational tasks is available at a detailed level15, occupational employment data is not always collected or published at the same level of detail across countries. This might undermine international comparability of estimates when sufficient detail is not available in certain countries (see section “Measuring green jobs at the regional level” for ways to resolve this issue).

Exclusion of ancillary or indirect activities: the approach mainly includes direct green jobs and therefore excludes workers that are employed in ancillary activities or jobs. Examples of this include security guards or accountants in the renewable energy sector.

Macro modelling approaches

Macro modelling approaches do not directly estimate the share of green jobs but instead examine the possible impact of green policies on the labour market. They may also measure the impact of other environmentally inspired changes in the economy, such as changes in consumer demand, preferences, or productivity. Therefore, this approach is flexible with regard to the definition of green policy. Macro-modelling approaches usually consist of dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) models that provide projections on how the economy and the labour market may respond to a given policy change. Thus, they can for instance be employed to provide ex-ante projections of the effects of concrete policy objectives such as the Paris Climate Agreement or the European Green Deal. One such approach is the OECD ENV-Linkages model (Box 1.9).

Box 1.9. OECD ENV-Linkages model

The ENV-Linkages model is a dynamic equilibrium model built primarily on a database merging national accounts that describes how economic activities are linked to each other among sectors and across world-regions through international trade. The model stylises the global economy as it splits the global economy into several global regions and sectors (usually 25 regions and around 50 sectors, but the regional and sectoral aggregation of the model is tailored by project). Jobs can be divided into 5 homogenous categories.1 Furthermore, firms can substitute employees with either capital or workers from another category but it is assumed that workers do not change category given the rigidity of most labour markets.

1. Blue collar and farm workers, clerical workers, service and sales, managers and officials, professionals

Source: (Chateau, Bibas and Lanzi, 2018[54]).

Macro-economic models can be used to study different questions or policies. For example, the OECD ENV-Linkages model has been used to study the jobs potential of a transition towards a resource efficient and circular economy (Chateau and Mavroeidi, 2020[55])(Chateau and Mavroeidi, 2020[52]). Other work has explored the consequences on the labour markets of structural changes induced by decarbonisation policies (Chateau, Bibas and Lanzi, 2018[54]). The latter finds a relatively small impact on the labour market, as less than 2% of jobs across the world would be destroyed compared to the baseline scenario. The study argues that this impact is not expected to be the same across industries or worker-types, with workers in both the energy industry and energy-intensive industries to be the most affected (i.e., 80% of total job destruction). In producing these estimates, the model assumes that revenues from the carbon-tax issues to foster decarbonisation will be recycled, meaning that tax revenues will be redistributed.

Advantages and limitations of the macro modelling approach

Macro models face a number of limitations but also offer benefits that complement top-down or bottom-up approaches used to define green jobs.

Benefits:

Policy guidance: They contribute to policy options by providing projections of likely consequences.

Future outlook: Those approaches can help identify possible challenges ahead, which can then inform policy choices. They also provide a forward-looking perspective, which complements top-down and bottom-up approaches that mainly look at the current situation or recent changes.

Limitations:

No short run: As the main objective of these models tends to focus on the medium to long term, they do not provide insights into the short-term impact of green policies or the dynamic relationship between the short and medium term. However, the short-term effects of green policies can be very relevant for a number of reasons. First, the short-run effects might differ from the long-run impact. For example, some sectors of the economy, which see no or positive influence in the long run, might suffer strong negative shocks in the short-run due to, for example, adjustment costs. Second, short-run adjustment costs, especially if high or concentrated on specific groups of workers, companies or places, can leave long-lasting detrimental effects that make it hard to return to a positive growth path or lead to widespread labour market detachment.

No sub-national analysis: One limitation imposed by the prioritised global perspective is the fact that sub-national impacts are unclear. Even international analysis is limited as most models focus primarily on comparisons between world regions.

Limited job categories: Most macro-models offer limited information on job categories. For instance, the OECD ENV-linkages model includes five job categories, preventing the analysis of specific job gaps that serve as labour supply bottlenecks limiting the green transition.

Measuring green jobs at the regional level

Analysis of the green transition’s labour market implications at the regional level is scarce. In fact, no study has, to date examined the green economy or the share of green jobs at the regional level consistently across different OECD countries. Subnational data and analysis have been limited to individual countries such as the US (Vona, Marin and Consoli, 2019[40]), the UK (Valero et al., 2021[25]) (Broome et al., 2022[56]), or the Netherlands (Elliott et al., 2021[39]).

This report fills that void with novel estimates on jobs that consist, to a significant degree, of green tasks. Those estimates are at the regional level, covering annual data for a decade (2011-2020/21) in 30 OECD countries. Thus, this report defines green-task jobs as those jobs with tasks that contribute to the green transition (see sub-section below for details). This stands in contrast to jobs in green sectors and is in line with the bottom-up approach discussed above.

There are a number of reasons why the analysis in this report applies a task-based approach to defining green jobs. First and foremost, it enables regional analysis across a host of OECD countries because of the availability of regional information on employment by occupation (either via labour force surveys or direct data provision by national statistical offices). This contrasts with sector-specific approaches, for which detailed data on employment across regions is often unavailable or not available at a meaningful level of sectoral disaggregation.16 Furthermore, in supporting policy makers in designing effective policy for managing the green transition, especially with respect to active labour market or skills policies, understanding how green jobs differ from non-green or polluting ones is crucial. In order to help workers navigate the pending labour market changes, one needs to know what skills they would require and what tasks they would have to pursue if they were to transition into green jobs and help deliver the green transition. Therefore, a task-based approach might be better positioned to help design training programmes and re- or upskilling offers. Another possible advantage is that sectoral approaches might only capture a small subset of green jobs due to their narrower focus on selected sectors, which will exclude jobs in other “non-green” sectors that may also, however, contribute to the green transition. Additionally, the approach also accounts for the fact that many jobs can be partly green, i.e. consist of both green and non-green elements (tasks).

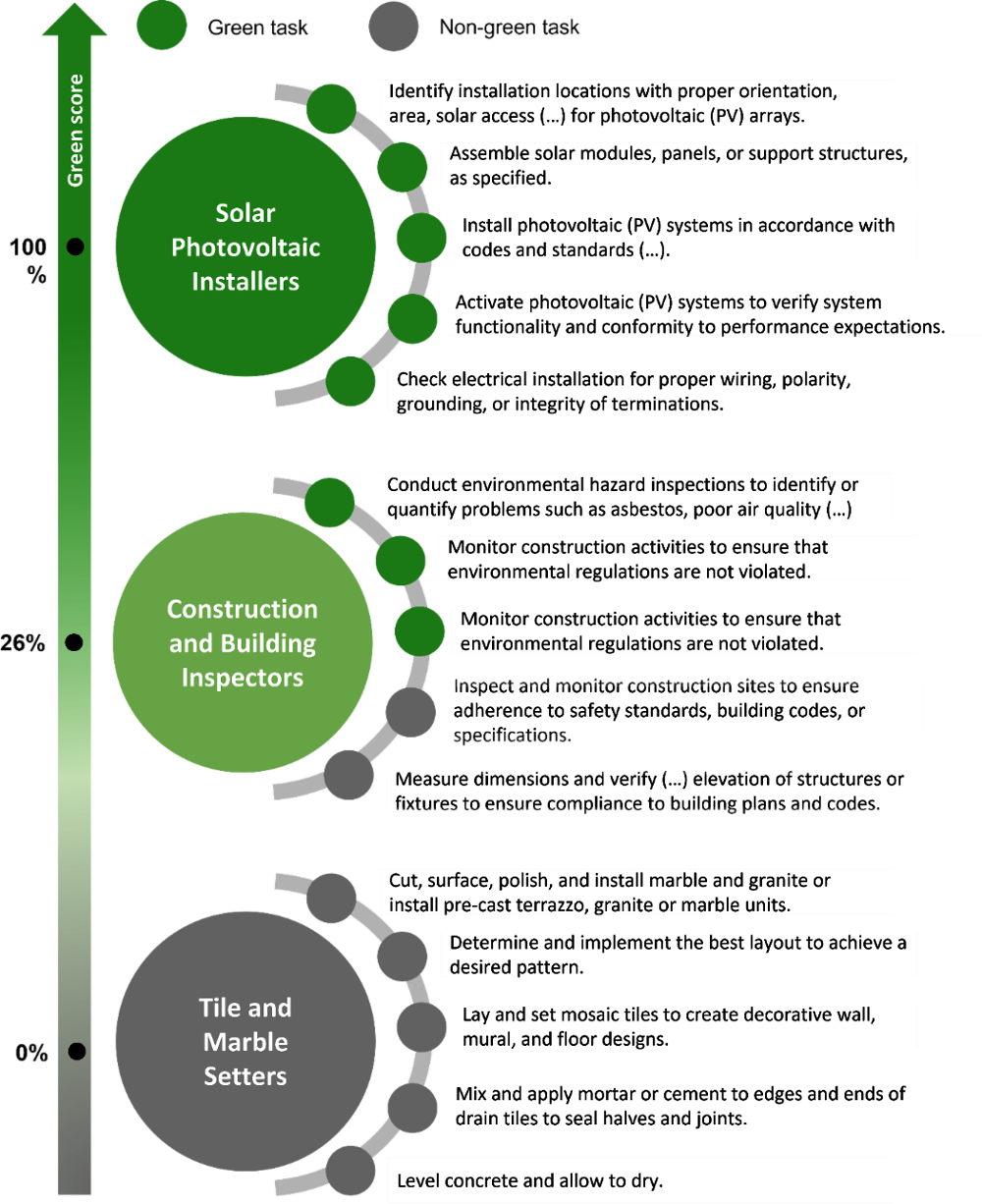

Estimating the share of green-tasks jobs

Following the work done by (Vona et al., 2018[45]), this report adopts a task-based approach to measuring and quantifying green jobs. O*NET’s Green Task Development Project (O*NET, 2010[57]) identifies occupations affected by the green economy activities and emergence of new green technology. It provides a list of individual tasks for each of these 8-digit SOC occupations and classifies these tasks as green or non-green.

O*NET identified two types of occupations with green tasks:

i. Green New and Emerging Occupations – These are new occupations, which correspond to jobs that were created in the economy in response to green economy activities and the emergence of new green technologies. Examples include solar photovoltaic installers and wind energy engineers. These occupations did not previously exist in the O*NET taxonomy. All tasks performed in these occupations are considered green.

ii. Green Enhanced Skills Occupations – These are occupations that underwent a significant transformation in terms of tasks performed in response to green economy activities and the emergence of new green technologies. Examples include construction and building inspectors and car mechanics. These occupations previously existed in the O*NET taxonomy. For these occupations a list of green tasks, associated with the impact of green activities and technologies, was created and added to the existing list of tasks in the occupation (non-green tasks).

As a result of the process, 1 386 green tasks were identified. All other tasks that were previously included in O*NET taxonomy are considered non-green.17

Using that information, Chapter 2 of this report computes the green intensity of an occupation, which can be broadly defined as the proportion of tasks within an occupation that are green. Therefore, this task-based approach provides a continuous measure of the greenness of occupations according to the share of tasks a worker completes on activities that contribute to the green transition. Infographic 1.2 shows examples of green and non-green tasks performed in selected occupation (non-exhaustive list of tasks), together with the green score (i.e., the share of green tasks) of the occupation. It is important to note that this measure focuses on jobs with green tasks rather than jobs in green sectors such as renewable energy. Although the two often coincide, this is not always the case.18

Based on the share of tasks in an occupation with some green tasks, a binary measure, which classifies an occupation as a green-task or non-green job, is constructed. This binary measure considers that a green-task occupation is one that consists of a considerable share of green tasks. In practice, an occupation is considered green if its green intensity is larger than 10% (0.1). This means that at least 10% of the tasks it entails are green.19 This 10% threshold also helps make estimates comparable across countries with different occupational employment information and occupation classification systems.

Indicators constructed at the occupation level are aggregated to regional (and then national) indicators. For this, occupational employment data at the regional level is used. The share of green-task jobs in a given region is simply the proportion of jobs within that region that are green. The green intensity of a region, on the other hand, is the simple weighted (by employment) average of the green intensity measures at the occupational level.

Infographic 1.2. Examples of green and non-green tasks performed in selected occupations

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on O*NET.

Estimating the share of polluting jobs

To identify polluting jobs, the approach by (Vona et al., 2018[45]) is used. This approach combines elements of the top-down and bottom-up approaches. It uses industry information regarding both employment and emissions. Furthermore, polluting jobs are a subset of non-green jobs, i.e. they entail no green tasks. Polluting jobs are determined by first identifying the occupations that are very prevalent in highly polluting industries.

Highly polluting industries are defined as those four-digit NAICS20 industries in the top 95th percentile of emissions of at least 3 (out of 8) contaminants. These eight contaminants are those controlled by the US-based Environmental Protection Agency plus CO221. This analysis yields 62 brown industries. Within these sectors, those occupations that are at least seven times more likely to be found in brown industries than in any other industry are identified as polluting occupations. For more detail and discussion on these occupations and their identification, see (Vona et al., 2018[45]).22

This analysis yields a binary indicator for polluting occupations. As with green jobs, this indicator is aggregated at the occupation level to obtain regional (and then national) indicators. The share of brown jobs in a given region is simply the proportion of jobs within that region that are brown. It complements the share of green jobs by examining the opposing side, which refers to the part of the labour market that is expected to be negatively affected by the green transition. Nevertheless, both these indicators originate from different definitions as green jobs are defined purely bottom-up while brown jobs are defined in a way that integrates elements from both the bottom-up and top-down approach.

Conclusion

Supporting OECD countries in their ambitions to move to a net-zero and green economy requires good data and evidence. The effective design and evaluation of policies aimed at supporting environmental objectives, green economic growth and the creation of green jobs benefit significantly from comprehensive evidence. Furthermore, setting up training and learning offers as well as targeted career guidance in supporting a just green transition requires information on green jobs and the skills they require. Finally, it requires a sound understanding of the green transition’s different impacts among workers, regions, and sectors of the economy.

A major caveat of existing evidence on the green transition is the lack of analysis of its uneven impact within countries, especially on jobs. Most analysis of jobs at risk or the contribution of the green economy focus on national data, individual countries or examine entire supranational entities such as the EU. Even less is known about the spatial dimension of green policies in the labour market. Within countries, regions differ significantly in their economic and industrial structure as well as the composition of their labour force. Therefore, they have both different exposure to risks of job loss and the potential to benefit from green job creation. Thus, the green transition might have implications for the spatial divide within countries and socio-economic disparities in and across local labour markets.

To help fill this gap, Chapter 2 of this report offers novel evidence from regions in around 30 OECD countries. It presents new estimates on the employment opportunities and risks at the subnational level while pointing out geographic differences across regions. More specifically, it shows that the shares of green jobs and polluting jobs, which face a greater risk of displacement due to the green transition, vary widely within countries. Furthermore, it documents the links between the greenness of local labour markets and a number of regional factors. Finally, it zooms in on the socio-economic impact of the green transition within local labour markets.

References

[48] Acemoglu, D. and D. Autor (2011), Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings, Elsevier-North, https://economics.mit.edu/files/7006.

[49] Acemoglu, D. and P. Restrepo (2018), “The Race between Man and Machine: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares, and Employment”, American Economic Review, Vol. 108/6, pp. 1488-1542, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20160696.

[20] Albrizio, S., T. Koźluk and V. Zipperer (2017), “Environmental policies and productivity growth: Evidence across industries and firms”, Journal of Environmental Econonics and Management, Vol. 81, pp. 209-226, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2016.06.002.

[47] Autor, D. (2013), “The “task approach” to labor markets: an overview”, Journal for Labour Market Research volume, Vol. 46, pp. 185-199, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12651-013-0128-z.

[46] Autor, D., F. Levy and R. Murnane (2003), “The Skill Content of Recent Technical Change: An Empirical Exploration”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118, pp. 1279-1334, https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552801.

[33] Bowen, A. and B. Hancké (2019), The Social Dimensions of ‘Greening the Economy’: Developing a taxonomy of labour market effects related to the shift toward environmentally sustainable economic activities.

[27] Bowen, A. and K. Kuralbayeva (2015), Looking for green jobs: the impact of green growth on employment.

[41] Bowen, A., K. Kuralbayeva and E. Tipoe (2018), “Characterising green employment: The impacts of `greening’on workforce composition”, Energy Economics, Vol. 72, pp. 263-275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2018.03.015.

[31] Bowen, A. and K. Kuralbayev (2015), Looking for green jobs: the impact of green growth on employment.

[56] Broome, M. et al. (2022), Net zero jobs: The impact of the transition to net zero on the UK labour market.

[14] Brucal, A. and A. Dechezleprêtre (2021), “Assessing the impact of energy prices on plant-level environmental and economic performance: Evidence from Indonesian manufacturers”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 170, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ec54222-en.