This chapter presents an overview of the constitutional, political and practical circumstances pertinent to linking Indigenous communities with regional development in Canada. It reviews the historical and current arrangements of First Nation, Inuit and Métis relations with Canadian institutions, and provides an introduction to three key debates: First Nations’ prospects for getting out from under the Indian Act; conflicts over land and resources management and; the role of Indigenous knowledge in contemporary decision-making.

Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development in Canada

Chapter 1. Overview of Indigenous governance in Canada: Evolving relations and key issues and debates

Abstract

Introduction

‘Indigenous people’ is a heterogeneous term that refers to the original nations and peoples of what is now called North America. In Canada today, the Constitution Act (1982) recognises three groups: Indians (now referred to as First Nations), Inuit and Métis. Despite constitutional recognition of their (undifferentiated) “existing aboriginal and treaty rights” (Section 35), citizens in these groups live with constitutional and legal divisions, the most important of which for First Nations is the Indian Act. Status under the Indian Act places individuals and First Nation communities in a relationship with the federal government unlike that of any other group of people in Canada.

Both demography and history are important to understanding current issues in the relationship between Indigenous people and the rest of Canadian society. Demographic change is underway and it will be important for future development. Indigenous people are the fastest growing segment of the Canadian; they are younger than the Canadian general population, and they are increasingly urban (see Chapter 2). In contrast, in many parts of the northern two-thirds of Canada, First Nation, Métis and Inuit comprise a large minority or the majority of the population.

Historical relations between Indigenous people and the settler societies include a number of key moments, specific to location and people. For example, the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the Treaty at Niagara (1764) and many other treaties defined the relationship between most First Nations and the Crown in the eastern and central parts of present-day Canada. Far western and northwestern First Nations are affected by the laws made pursuant to these milestones, though many remain without treaty. Some First Nations, Inuit and Métis are party to treaties negotiated since 1975, referred to as comprehensive land claim agreements or modern treaties. Some modern treaties have self-government provisions, some do not and some self-governments do not have a modern treaty. Taken together, the treaties, evolving jurisprudence since 1982, and influential public enquiries have created a complex legal field in which Indigenous peoples’ land and other rights have been steadily specified.

Three key contemporary areas of debate and discussion include: i) self-government and the movement to supersede Indian Act government; ii) conflicts over land use and economic development; and iii) the role of Indigenous knowledge in policy and decision-making. Currently, a movement among First Nations to get out from under the Indian Act coincides with a federal policy opening to respond; there is a real prospect that more and more First Nations will build upon past experience to remove themselves from the Act’s jurisdiction. Disputes over land use and economic development have been a long-standing feature of Indigenous-settler relations, and they are likely to accelerate even as Canada moves to align its laws with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Conflict over land use has been ‘regularised’ in many parts of the country, as modern treaties create institutions for this purpose and as federal environmental assessment processes adapt to legal requirements related to consultation and accommodation. None of these procedures though reduces the development pressure on Indigenous lands and resources. Incorporation of Indigenous knowledge in federal/provincial/territorial decision-making is a frequently appearing requirement or aspiration, but there are reasons to be cautious about the extent to which it is possible. Here it is useful to distinguish between local knowledge based upon empirical observations over long periods, and ethically grounded knowledge or cosmological concepts that are not easy to bring into modern resource use discussions.

This chapter provides background information necessary to understanding the links between Indigenous communities in Canada and regional development.1 It begins with an explanation of key terminology and a demographic overview followed by an historical overview of policy and institutional settings related to Indigenous peoples in Canada follows, by way of situating current circumstances and debates. These sections inform the concluding discussion of key debates and challenges regarding Indigenous economic development in Canada.

Key terminology

To make sense of the current situation concerning regional development and Indigenous communities, and to interpret demographic data, it is essential to understand some basic definitions and distinctions.

The original nations and peoples2 of what is now Canada include the Mi’kmaq, Mohawk, Anishnabe, Cree, Dakota, Piikani, Kainaiwa, Inuit, Dene, Haida nations and many others. In the estimate of the Royal Commission Aboriginal Peoples, Indigenous peoples living in Canada comprise between 60-80 nations.3 For millennia, they have occupied all of the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific to the Arctic Ocean. Historically, they made their livings in a variety of ways, including hunting, fishing, gathering, farming, and trade in raw materials and manufactures. These occupations persist, though now Indigenous people also participate in every facet of the contemporary Canadian economy. Original political forms varied from small self-governing units to hierarchical societies and confederacies. In the thousands of years before they had contact with European migrants, the original peoples of course went through many changes, but due to massive epidemics and other losses after European contact, much of this history has been obscured.4

Today, the original nations and peoples retain their languages and ways of life to some degree, but all have been in various ways reorganised. For official purposes and in relations with modern state institutions, other names for them have come into use:

The collective noun ‘Indigenous peoples’, analogous to the term ‘European’, is used to refer to the descendants of all of the original nations and peoples of northern North America.

The synonymous term ‘Aboriginal peoples’ is still used in the Canadian Constitution, though under the influence of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and international law it is being supplanted.

Both terms --‘Indigenous’ and ‘Aboriginal’-- are artefacts of the arrival of European settlement, useful for distinguishing the societies that were here from the societies of the new arrivals who began to settle around 500 years ago, but otherwise concealing important national and cultural differences.5

While the most salient and accurate terms are the names used by Indigenous nations and peoples to identify themselves, for the purposes of statistical record keeping, program eligibility, and some political processes, other distinctions have been created. The Constitution Act (1982) in Section 35 recognises ‘the existing aboriginal and treaty rights of Indians, Inuit and Métis.’ It is generally accepted that these three constitutional categories exhaust the possible ways of being Indigenous, although in most parts of Canada, the term ‘Indian’ has been replaced by ‘First Nation’. Similarly, in Canada ‘Inuit’ has replaced the older term ‘Eskimo’ which is now considered by many to be pejorative, and similarly Métis is used rather than ‘Half-breed’.6

An older distinction survives, and still has practical effect. This is the legal distinction between people who have ‘status’ under the Indian Act, and those who do not. Someone who has status is registered on a list maintained by the Department of Indigenous Services (hence the near synonym for Status Indian, ‘Registered Indian’).7 A person who is so registered is usually but not necessarily a member of an “Indian Band,” and is subject to the federal Indian Act. The Indian Act assigns ‘province-like’ responsibilities for Status Indians’ health, education and social welfare provision to the federal executive branch, even while it makes Status Indians subject to provincial laws of general application. Importantly, people subject to the Indian Act also, for decades, did not have the rights of full Canadian citizens. For example, between 1927 and 1951, Status Indians were prohibited from raising funds for the purposes of political self-representation, and they did not have the right to vote in federal elections until 1960. Status Indians are also subject to Band Council bylaws, which is another jurisdictional layer that creates uncertainties around application in specific contexts (e.g., provincial/territorial hunting regulations versus Band Council conservation bylaws).

Although the original idea of Indian registration was to keep track of people who were ethnically (actually, in the nineteenth century language, racially) Indigenous, it has always been possible for people with no Indian heritage to have Indian status. Until 1985, women who married status Indian men automatically became status Indians, whatever their heritage, and their children were also status Indians. Conversely, Status Indian women automatically lost their status upon marriage to a non-status man.8 In addition, because the original registration process was imperfect and missed registering individuals who were Indians, and because it has always been possible for registered Indians to choose ‘enfranchisement’ –that is to renounce their Indian status to become full Canadian citizens—there are individuals who consider themselves to be Indians, who are members of Indian families and communities, but who are not listed on the Indian Register.

The other two constitutional groups, Inuit and Métis, were never registered under the Indian Act, although both have been subject to now-abandoned enrolment procedures.9 Inuit names were difficult for early missionaries and government officials to understand and pronounce. Attempts were made to assign new names, and ultimately, in 1941, federal officials assigned each person a number, which was embossed on a disk which Inuit then wore around their necks. The practice of numbering Inuit citizens was abandoned within a couple of decades, and most began to use given names and surnames for official purposes. Traditional names may still be used in everyday life.

Métis, who are members of an Indigenous society that grew up in the western Canadian plains during the 18th century, were never subject to registration or the Indian Act. Métis individuals were listed during the late 19th century during an attempt at the settlement of their land rights through the issuing of ‘scrip’, which entitled them to land or a cash settlement.

Outside of the Indian Register, there can be some debate about specific individuals’ claims to Indigenous identity. For statistical and most program administration purposes, self-identification is accepted. The Canadian Census asks whether a person is an Aboriginal person if they are First Nations, Métis or Inuk. As might be expected, there are far more people with Indigenous ancestry than there are people who identify themselves as Indigenous.

Presently, self-identified Indigenous people comprise between 4-5% of the total Canadian population, and this proportion is increasing (see Chapter 2 for overview of demographic trends). Due to a much higher birth rate and to increases in self-identification, their numbers are growing much more quickly than is the non-Indigenous population.10 There are important regional variations in population distribution:

Inuit are the large majority in three of their four northern homelands (referred to as Inuit Nunangat); for example, in Nunavut they comprise 85% of the population. About 20% of Inuit now live in southern Canadian cities, with Ottawa and Montreal having the largest numbers.

Canada’s population is highly centralised, with most people living within 500 km of the border with the United States. In this area, Indigenous people are a small proportion of the population –around 4%.

In most of the northern 2/3 of Canada, Indigenous peoples form a large proportion of the population. In certain regions (Nunavut, much of the Northwest Territories, parts of northern Manitoba, northern Saskatchewan and Yukon outside of the capital, Whitehorse) they are the majority.

Over the last several decades, Indigenous people have become urban dwellers. Around a quarter of the total Indigenous population live in the twelve largest Canadian cities (Census Metropolitan Areas).

Concerning measures of social well-being, there are strong regional differences and significant differences within each group as well (see Chapter 2 for discussion). Nevertheless, one can note that social indicators generally reveal that well-being for Indigenous people as a whole is lower than those that prevail in the general Canadian population. To take one example, while almost two thirds of the non-Aboriginal population had attained at least one post-secondary certification in 2011, about half of Aboriginal people had done so.11

Legal and jurisdictional frameworks

Each Indigenous nation and people has its own original legal framework and constitution. These laws and constitutions have been under assault since the arrival of missionaries, whose teachings undermined traditional authorities and rules. Other pressures on the original legal systems included loss of social cohesion and cultural memory due to new diseases and loss of land, and ultimately the consolidated efforts of state institutions, which came at different times in different parts of Canada. In general, in Canada, colonial policy grew more intrusive through the nineteenth century, shifting from diplomacy to control and containment to assimilation. For First Nations, the principal legal instrument was the Indian Act, passed soon after Confederation. Métis efforts to be self-governing were put down with force in two confrontations in the late 19th century, resulting in the loss of land and dispersal of Métis throughout western Canada. Inuit societies experienced major disruptions to their own forms of social control mainly during and after the Second World War, when the United States military presence and then Canadian state interventions began.

In many places, Indigenous peoples are establishing new forms of government.12 Inuit have established their own governments in three of four Inuit regions. One is exclusive to Inuit (Nunatsiavut in Labrador) while in other regions there is “public government” in which participation is open to all residents (Nunavut and Kativik Regional Government). Inuvialuit, in the fourth region of Inuit Nunangat, have a treaty negotiated in 1984, and an agreement in principle which was signed in 2015 (hence, the process has not been fully concluded). Their representative body is the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. Some First Nations and a smaller number of Métis are also parties to modern treaties, and have created governing institutions pursuant to those treaties (Box 1.1). In other places, First Nations governed by the Indian Act are building alternative institutions with the long run goal of removing themselves from Indian Act jurisdiction. This has resulted in a wide range of evolving forms of self-determination on self-government.

Indigenous laws also include treaties with other Indigenous nations and with the principal settler powers – most importantly, with the French and British Crowns and the Crown in right of the Government of Canada. The treaties and other relationships among Indigenous nations and peoples and the rest of Canadian society and governments have been the object of political action and reform, in the legal system no less than in other facets of life. This is illustrated by evolving constitutional law.

Since 1982, the Constitution Act has been the most important statement of settler-state law relevant to Indigenous peoples. It recognises “existing aboriginal and treaty rights,” explicitly including modern treaties (also known as comprehensive land claim agreements) and the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (a statement of the British Crown that recognises Indigenous sovereignty).

Box 1.1. The recognition of Métis rights

The recognition of the Aboriginal rights of Métis has evolved recently in Canada. The 1982 Constitution was the first document to recognise Métis in the category “Aboriginal” and protect the Métis people’s “existing aboriginal and treaty rights” in Section 35. Against the perception that recognition had been merely symbolic and that Métis possessed no existing rights, in 2003 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on R. v. Powley. Powley’s direct impact allowed broader Métis hunting on traditional territory and instituted a legal test for rights-bearing Métis communities. Because of Canada’s jurisdictional division of powers, which assigns land and resource management to the provinces, Powley was also a driver of provincial-level negotiations in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Ontario, and British Columbia.

Building from Powley, two more Supreme Court decisions, MMF v. Canada, 2013, and Daniels v. Canada, 2016, have challenged Canada’s delegation of Métis issues to the provinces. In MMF v. Canada the court found that the federal government had failed in its constitutional obligation to protect Métis interests in the 1870s allocation of Manitoba lands. In effect, the court identified the need for a bilateral relationship between the Manitoba Métis Federation and the Government of Canada. In Daniels v. Canada the Supreme Court stands for the proposition that Métis fall within federal, as opposed to provincial, jurisdiction. Although the federal government may not have a legal duty to exercise its legislative authority, it does have “a legal duty to negotiate in good faith to resolve land claims.”

In 2016 Thomas Isaac, the Ministerial Special Representative to Lead Engagement with Métis, released a report containing 17 recommendations for a new framework to address Section 35 Métis rights. The recommendations range from registration of Métis people to the elaboration of consultation agreements to the revision of the comprehensive land claims policy or development of other policy in order to address Métis rights claims.

Since 2017, Canada has engaged in Recognition of Indigenous Rights and Self-Determination discussions with each of the governing members of the Métis National Council as well as the Métis Settlements General Council. In 2018, Canada signed the first fiscal agreement with the Manitoba Metis Federation which will be used to support the social, cultural and economic well-being of the Métis community in Manitoba. This represents a significant shift and real action to advance reconciliation, since for decades Métis rights had gone unrecognised.

Adapted from: “The lands…belonged to them, once by the Indian title, twice for having defended them…and thrice for having built and lived on them”: The Law and Politics of Métis Title and Better Late Than Never? Canada’s Reluctant Recognition of Métis Rights and Self-Government.

Sources: Newswire (2019[1]), “Historic self-government agreements signed with the Métis Nation of Alberta, the Métis Nation of Ontario and the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan”, https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/historic-self-government-agreements-signed-with-the-metis-nation-of-alberta-the-metis-nation-of-ontario-and-the-metis-nation-saskatchewan-877461716.html (accessed on 27 October 2019); Metis agreements signed by the Minister of CIRNAC.

Evolving jurisprudence

Aboriginal and treaty rights in the Constitution Act

A series of Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) and lower court cases have given substance to the recognition of existing aboriginal and treaty rights in the Constitution Act (1982):13

R. v. Sparrow (1990) was the first SCC case to interpret Section 35. The decision asserts that the burden of proof is on the Crown to justify negative infringements on Section 35 rights, and outlines what came to be known as the Sparrow Test to determine when infringement was permitted.

Delgamuukw and Gisdayway v. British Columbia (1997) clarified the definition and content of Aboriginal title in relation to self-government, describing Aboriginal title as a right to the land itself that includes a right to decide how those lands are used.

The Supreme Court of Canada’s Haida (2004), Taku River Tlingit (2004) and Mikisew Cree (2005) decisions further clarified, developed, and expanded the principles advanced in Delgamuukw and Gisdayway, finding a duty to consult and duty to accommodate Indigenous landholders in areas without treaty but where Indigenous title has been proven or is asserted.

The Tsilhqot’in (2014) decision asserted that “the dual perspectives of the common law and of the Aboriginal group bear equal weight in evaluating a claim for Aboriginal title”.14 Tsilhqot’in is the first case where the court found that the specific Indigenous group had Aboriginal title. It stated that Tsilhqot’in consent was required before there could be infringements on title lands, and recommended that the Crown seek consent before title was proven. The SCC has also ruled on the protection of Indigenous rights to lands that are covered by modern treaty.

Most recently, in late 2017 in Nacho Nyak Dun, et al. the SCC ruled in favour of Indigenous parties to the Yukon Umbrella Agreement that the Yukon Government did not have the right to circumvent land use planning provisions outlined in the treaty.

In the past decade and a half, the trajectory of jurisprudence has evolved from a procedure for justifying infringement on Section 35 rights to finding that Section 35 recognises, affirms and protects rights. In stages, the SCC explored the consequences of this for decision-making over land use, expressed in the phrase “the duty to consult and accommodate”, which is a duty on all those who would use Indigenous lands.15

Importantly, many Supreme Court cases on these issues have occurred in British Columbia with First Nations without an original treaty. In at least some cases, such as R. v. Sparrow, the absence of a treaty extinguishing rights to land/resources has been central argument to Sparrow’s defence.

The status and rights of Inuit and Métis

The courts have also been important in clarifying the status and rights of Inuit and Métis. For Inuit, a SCC reference in 1939 determined that even if they lived in a province (in this case, Quebec) they fell under Section 91 (24) of the British North America Act (now the Constitution Act 1867) which assigns federal responsibility to “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians.” There have been three important decisions affecting the legal status of Métis rights:

1. R. v. Powley (2003) established harvesting rights, but also set a legal test for determining who is Métis for the purposes of Section 35.

2. Métis land rights in Manitoba were advanced by Manitoba Métis Federation v. Canada (2013). The Court declared that Canada failed to uphold and honour of the Crown when implementing land provisions of Manitoba Act and recognised the duty of diligence as part of the honour of the Crown.

3. In 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada decision in Daniels determined Métis and non-status Indians to be “Indians” under Section 91(24) of the Constitution – and thus, a federal responsibility.

This sequence of legal decisions shows the impact of Section 35 on Canadian law with respect to both Indigenous identity and Indigenous title. While this movement is important, critics have pointed out that the courts still fail to fully recognise Indigenous sovereignty and the independent status of Indigenous law.16 Further court cases, and further elaboration of the principles, may be expected.

Jurisdiction over Indigenous affairs

The great divide among Indigenous people in Canada is between those who fall under the Indian Act and those who do not, but there is nothing simple about how this divide has worked out in practice. First Nation citizens who are governed under the Indian Act and reside on reserve fall under federal jurisdiction for healthcare, education and many forms of social provision that are for the rest of the population a matter of provincial responsibility. Their reserve lands and collective wealth are under federal control, managed “in trust” –unless they have taken advantage of certain federal programs that provide for a degree of independent economic management and funding arrangements (discussed below). Despite the dominant role of the federal government, Section 88 of the Indian Act provides that provincial laws of general application apply to individuals who are governed under the Indian Act.

Negotiation of a modern treaty removes the First Nations parties from Indian Act jurisdiction, but they remain a federal responsibility under Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act. The modern treaties also create a number of government-to-government relationships with relevant provincial and territorial governments.

As noted above, since the Supreme Court of Canada reference in 1939, Inuit have fallen under federal jurisdiction; there is therefore, for example, a First Nations and Inuit Health Branch to dispense funding and develop programs. Inuit have never been governed under the Indian Act, however, and there has been no equivalent piece of legislation for them. Furthermore, with the settlement of comprehensive land claim agreements (otherwise known as modern treaties, discussed elsewhere in this report), different arrangements have been made for social provision for Inuit. Each comprehensive land claim agreement or modern treaty includes specific arrangements for the funding and delivery of social services, for land management and for other governance functions.

Métis have never been subject to the Indian Act. For health, education and social provision they are served in similar fashion to the general population, though there are now many federal programs (in employment and business development for example) for which they are eligible as Indigenous people.

Actors, roles and responsibilities: A complex field

From Indigenous governments to Indigenous organisations – there are a vast number of institutions across Canada

Indigenous governments include what many would call Indian Act Band administrations –on-reserve governments set up by the Indian Act – through to Band governments with increasing degrees of autonomy negotiated through the federal self-government process. Band councils and government-funded service agencies have been critiqued for being organised to serve the interests of the Canadian state, as opposed to First Nations interests or laws (Taiaiake Alfred, 2009[2]). As such, they be an inappropriate focus for “planning or leading the cause of indigenous survival and regeneration” (Taiaiake Alfred, 2009[2])

There are also Indigenous governments that have been established consequent to the negotiation of a comprehensive land claim agreement (a modern treaty), such as the Tlicho Government in the Northwest Territories, the Nunatsiavut Government in Labrador, and the unique Nunavut Territorial Government, which is a public government for all of the residents of the territory (not just Indigenous).17

The modern treaties were signed by beneficiary or representative organisations – the legal entities that administer the terms of the agreement on behalf of the Indigenous parties to the agreement. Their role includes managing the cash and capital owned jointly by the Indigenous parties, discharging a number of other responsibilities specified in the modern treaties, and increasingly, speaking as the voice of their citizens and members.

There are hundreds of Indigenous organisations serving a number of purposes: political advocacy, service delivery, economic development, and research. Often a single organisation will combine more than one of these roles. Political advocacy organisations exist at the federal, provincial and territorial levels, and in few cases, at the city level. For example: the Assembly of First Nations represents First Nations across Canada; the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada is a Canada-wide think tank and advocacy organisation devoted to child welfare; the Indigenous Leadership and Development Institute, based in Winnipeg, is a non-profit organisation devoted to leadership development and training. However, it bears noting that modern treaties and self-government agreements are not necessarily represented by the Assembly of First Nations.

This is a rich institutional landscape involving many actors who do not speak with one voice. Public policies and investments on Indigenous lands need to develop ways of meaningfully engaging with this diversity of voices. This is complex, and involves overcoming inherent power asymmetries and yet it is fundamental to the successful implementation of FPIC principles.

The federal government has direct obligations to Indigenous peoples, but the scope of provincial-Indigenous relations is less well defined

The Government of Canada has a direct relationship with Indigenous peoples and government that is grounded in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. This provides constitutional protection to the Indigenous and treaty rights of Indigenous peoples in Canada and in different pieces of legislation and agreements, which governed these relations. For example, the Indian Act has governed and controlled virtually every aspect of the lives of Status Indians. The federal government’s relationship with Indigenous peoples has evolved in recent decades and will continue to do so. These relations differ for Métis, Inuit and Status Indians depending on whether they live on or off reserve. Virtually every federal department has specific responsibilities related to Indigenous–Crown relations. The most prominent for decades has been the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, which was split into two ministries in 2017: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada.18 In 2017, the Government of Canada has established permanent bilateral mechanisms with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation leaders to identify joint priorities, co-develop policy and monitor progress: Government of Canada and First Nations bilateral mechanism, the Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee, and the Government of Canada and Métis bilateral mechanism.

There is an evolving consensus that federal government fiscal relations with First Nations, Métis and Inuit should evolve from contributions which involve a great deal of administration, towards the types of formula-driven funding that characterise federal/provincial/territorial transfer payments. (Donna Conna, 2011[3]). This would give First Nations greater discretion in using their funds and would focus accountability on benefits to community members.

While the federal government has direct relations and obligations to Indigenous peoples in Canada, relations with provincial governments are less clear. Provincial/territorial governments in Canada hold responsibility for a wide range of matters that are important for Indigenous peoples including natural resources development, infrastructure, health and education. Meanwhile, devolution remains pending for Nunavut. For those living on reserves, the federal government bears responsibility for these matters; while for those off reserve, it is the provincial/territorial government that fulfils this role. As such there can be a disconnect between these two spaces in term of how they are regulated and how public investments are delivered. This will be discussed at length in Chapter 5. The need to improve multi-level governance and Indigenous relations in Canada is well recognised. In an effort to address this, in 2016, the Aboriginal Affairs Working Group (consisting of provincial and territorial ministers of Aboriginal affairs and leaders of the national Indigenous organisations) was transformed into the Federal, Provincial, Territorial and Indigenous Forum (FPTIF). This forum is mandated to identify priority issues, monitor progress and map out future areas for collaborative effort as well as advance reconciliation.

While provincial-territorial Indigenous relations may not be directly legislated, nevertheless, almost all provincial and territorial governments have departments or agencies devoted to maintaining a relationship with the Indigenous residents; most have several. For example, the Province of Alberta has established an Aboriginal Consultation Office, an office for Stewardship and Policy Integration, for First Nation Relations, Métis Relations, Indigenous Women and various programs to support business development.

In a similar vein, municipalities are increasingly recognising the need to provide their Indigenous populations with services and infrastructure for community development. Municipalities are developing methods to strengthen their engagement with Indigenous voices on such issues and land use and community planning and development, and culture and heritage recognition and valorisation. Toronto, Vancouver, Edmonton and Winnipeg have all established Aboriginal offices and/or advisory committees in an attempt to move beyond ad hoc approaches to more systemic and institutional involvement (Newhouse, 2016[4]).

Historical overview

It is impossible to understand the current situation in Canada, or Indigenous peoples’ objectives, without an understanding of the history of non-Indigenous settlement and consequence interactions. It is a history long obscured and misrepresented, now in the process of retrieval and revision thanks in part to the work of several commissions of inquiry.19

Beginning in the 16th century, Indigenous nations and peoples of what is now Canada established economic and diplomatic relations with new arrivals from various parts of Europe, as these traders, missionaries and explorers arrived on various shores. There are thus many ‘contact histories’ – indeed, a history for every nation and people in all regions of Canada –and these should not be conflated. It is possible, however, to outline the main stages of contact history at a high level of generality, bearing in mind that actual relationships evolved in different times and at different paces, subject to different degrees of cooperation, diplomacy, conflict and contamination by diseases.

The first French and British traders and wealth seekers initially accepted the terms of the Indigenous landholders they encountered. They had no choice but to do this, as almost without exception they relied upon the Indigenous people they encountered for food and technology. They also sought trade, mostly for furs, local knowledge about the location of promising mineral deposits, and fish. European sojourners who came for fish, principally cod, temporarily basing themselves on the east coast while they salted the catch. Traders, fishers and explorers sought varying degrees of contact with local people, who generally controlled the degree and format of intercourse. On the prairies, the commercial relations of the fur trade prevailed for well over 100 years beginning in the 18th century, while for eastern Arctic Inuit, contact with European explorers and missionaries was minimal for almost 300 years after first encounters, followed by the intense ‘invasion’ of Canadian and American military and other state personnel during the Second World War.

These contacts occurred during the great age of European mercantile expansion. Like the Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese (and later other countries) the French and British monarchies were engaged in a global competition for raw materials and trading opportunities; from their perspective, due to considerations of climate and terrain, most of the northern half of North America was not as desirable as the southern parts of the continent for settlement and the export of surplus population to plantations. Ultimately, though, both French and British settlements were established in what is now Canada.20 They formed alliances with Indigenous nations as North America developed as one of many theatres of imperial conflict.

Original Mutual Recognition: The Royal Proclamation and the Treaty at Niagara

The 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended of the Seven Years War resolved the future European presence in North America. It left almost all formerly French territories in British hands and confirmed British (and in the south west, Spanish) control of the continent. The disposition of these lands was addressed in George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763, which set the terms of governance for the French-speaking colonies that had come under British rule, provided substantial North American land grants to soldiers, and took a number of measures designed to control further westward movement of settlement into Indigenous lands. Specifically, the Indigenous nations west of the continental divide were declared to be under Crown protection and the right to make treaty with them was reserved to the British Crown. This provision likely added to grievances held in the Thirteen Colonies, which began a successful war of secession in 1776. Thus, the end of the eighteenth century found most of present-day Canada assigned to British imperial aspirations, and relations with Indigenous nations and peoples a matter of British Crown policy. To the south, there was a restive, frequently hostile neighbour.

Many, but not all, of the Indigenous nations who were most directly affected by the land and diplomatic arrangements in the Royal Proclamation convened a great meeting of about 2 000 chiefs from 24 nations at Fort Niagara in 1764. In the face of the shifting military balance among European powers, the Indigenous nations reached agreement among themselves and negotiated a treaty with the British superintendent of Indian Affairs, William Johnson. They ratified the terms of the Royal Proclamation and knit Great Britain into the web of alliances and diplomatic arrangements that had long governed relations among Indigenous nations. These included, in eastern North America, the Silver Covenant Chain, which stood for the system of alliances designed to preserve the peace and regulate the sharing of land. Thus, the Treaty at Niagara was supposed to be honoured by new settlers moving into territories claimed by Britain, which would become Canada.

Indigenous Diplomacy: Indigenous Diplomacy: Treaties Signed Between 1701 and 1923

Conventionally, treaties between European powers and Indigenous nations in northern North America are grouped temporally: historic treaties (1701-1923) and the modern treaties (1975-present). Treaties concluded prior to 1867 were to establish and renew peaceful relations, defend the colonies and open the lands of the Great Lakes to settlement. After Confederation, treaties were concluded to secure Canada’s title over the West, open the lands for settlement and secure peaceful relations with First Nations. Aside from some adhesions (a mechanism for groups to sign on to existing treaties) there were no further land negotiations until the 1970s. When negotiations over land were halted by the Dominion government in the 1920s, there were almost no treaties in British Columbia, and none in present day Nunavut and Yukon Territory.

As settlement of North America proceeded and Indigenous nations were weakened by disease and loss of the natural resources upon which they depended, federal legislation (the Indian Act) and administrative control replaced diplomacy and interdependence. Indigenous parties to the treaties did not abandon their original purposes and understanding of the treaties, but for decades they had scant capacity to insist that they be appropriately recognised, respected and implemented.

The Indian Act

By the time the last numbered treaties were being negotiated, most of southern Canada was occupied and linked together by a transcontinental railway. Provincial governments had been assigned jurisdiction over “Crown land” under the British North America Act (BNAA)21 that established Canada. Crown land refers to public land – that is, all land not already in private hands.22 From another perspective, most of the so-called Crown land is Indigenous land, since Canada was fully occupied when European claims were made.

Despite the treaty provision that the Indigenous parties should enjoy the use of their entire traditional territory in perpetuity, provinces enthusiastically promoted development on these lands. The BNAA assigned jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians” to the Dominion government. The Dominion government established a system of reserves, small tracts of land to which the Indigenous parties were confined. The Indian Act, passed in 1869 and consolidating prior British legislation, became an instrument of control and forced social transformation. The Act and attendant federal policies undermined the capacity of Indigenous governments by banning long-standing Indigenous governance practices, forcing Indigenous people to live in small, isolated communities, enforcing accountability “out” to the executive branch of the federal government, imposing direct control by a resident Indian agent and later control through onerous accountability mechanisms. These same provisions also created a federal Indigenous Affairs bureaucracy that is oriented to control, oversight and enforcement.23 The Indian Act assigned control over reserve land and reserve economic development to the federal executive branch, effectively to public servants. For many years, this control was very heavy handed: Indians were not allowed to leave the reserve to work without a pass from the Indian agent, nor could reserve residents undertake other economic ventures (such as selling their produce or renting their pastures) without this person’s permission. Political activity was equally controlling –the rules of Band government were enforced, including such measures as biannual elections of Chief and Council. After 1927 Indians were prohibited from raising funds for the purposes of self-representation, and they did not have the right to vote in federal elections until 1960.

Indigenous Resistance and the New Era of Treaty-making

Over decades, Indigenous peoples’ resistance to their lack of democratic control and the loss of their traditional land eventually brought about constitutional and legal change. Indigenous pressure that treaties be respected and their traditional land rights recognised never ceased, but it was given new momentum after the Second World War. Indigenous veterans, who had served in much greater proportion than their numbers in the general population, returned to inequality. In some cases, their homes had literally been appropriated under the War Measures Act to serve military purposes, while Status Indians returned to unequal legal status. They began to organise. They were part of a global mobilisation of resistance to such discrimination and unequal treatment, resulting in Indigenous rights movements in all of the settler Dominions, the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, and the United States civil rights and Indian rights movements, to mention just a few. At the same time, a wave of revulsion against ethnically based legal and illegal discrimination passed through all of the Second World War combatant countries, creating a much more receptive environment for change. In Canada, one consequence was the first important revision of the Indian Act in decades. The most discriminatory provisions were removed in 1951, including the prohibition against fund-raising for the purposes of political self-representation. These changes liberated even more energy, so that through the 1950s and 1960s, Status Indians and ultimately non-Status, Métis and Inuit also, began to form organisations to fight for recognition of their land rights and more control over the terms of their lives as Canadians (or as some might prefer, Indigenous Peoples living in Canada).

Two federal initiatives of the 1960s had a powerful impact on the Indigenous movement.24 In 1965, the federal government commissioned University of British Columbia professor Harry Hawthorn to lead a task force to investigate Indian conditions in Canada. After research and Canada-wide discussion with Status Indian leaders, the task force reported, proposing the concept of ‘Citizens Plus’ to express the view that Status Indians should have all the rights and responsibilities of other Canadian citizens while they also held special rights arising from treaties. The Hawthorn report was generally favourably received by Indian leaders –but it was apparently ignored by the new Liberal government elected in 1968 led by Pierre Trudeau. As is well known, Trudeau was an anti-nationalist and opposed “special rights” based on ethnicity. Within a year, his government produced a White Paper (that is, a discussion paper), the Statement on Indian Policy, that proposed a different vision.25 The White Paper asserted strongly that Status Indians should have full citizenship rights and responsibilities, but no special rights, and it envisioned the orderly phasing out of both treaty provisions and special federal responsibilities. The reaction from Status Indians people was immediate, and almost entirely negative. They insisted upon respect for the treaties and for their special relationship to the Crown (represented by the federal government), and rejected any unilateral actions by the federal government to alter the relationship (Cardinal, 1969[5]).26

While the White Paper, coming on the heels of the more acceptable analysis in Hawthorn Task Force Report, was a catalyst for mobilisation, it was not the source. The struggle for respect for treaty rights had begun in the 1950s. In addition, there were other concerns. The integration of the Canadian and United States economies during the Second World War continued into the post-war years, with Canadian water, hydroelectric power, lumber and mineral resources in high demand. Most of these resources were found in the mid-North, on Indigenous lands previously undisturbed by industrial capitalism. In northern Quebec and the Mackenzie Valley in the late 1960s, and subsequently in other parts of the north, Indigenous people mobilised to secure land rights and to gain some control over the pace and direction of northern development.

Thus, Indigenous people across the country were well-organised and mobilised by the late 1970s, when the Trudeau government began to discuss the patriation of the Canadian constitution. Ultimately, the Indigenous organisations and their allies in the New Democratic Party were successful in entrenching “existing aboriginal and treaty rights” (Sec. 35) in the Constitution Act (1982), and introducing some other protective provisions. Section 35 of the Constitution Act states that:

The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognised and affirmed.

In this Act, “aboriginal peoples of Canada” includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.

Furthermore, Section 25 of the Act notes that: "guarantee in this Charter of certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada including (a) any rights or freedoms that have been recognised by the Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763; and (b) any rights or freedoms that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired".

Despite inclusion of existing aboriginal and treaty rights (Sec. 35) in the Constitution Act (1982), the substantial meaning of the phrase "hereby recognised and affirmed" could not be reached, the drafters provided for a series of First Ministers Conferences to follow patriation (Sec. 37). These concluded in 1987 with no agreement. A final attempt to specify the meaning of Sec. 35 was made during the negotiation of what came to be called the Charlottetown Accord, an omnibus effort to deal with a number of outstanding constitutional issues. The Charlottetown Accord was defeated in a national referendum in 1992, ending over a decade of popular mobilisation and elite accommodation on matters constitutional.

As no political resolution to the meaning of Sec. 35 was achieved, it has fallen to the courts to interpret these provisions, aided by an active cohort of specialist constitutional lawyers and by the work of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the Reconciliation Agenda

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was appointed in 1991 in the aftermath of the failure of the post-1982 constitutional conferences, and the outbreak in 1990 of serious conflict over the use of Indigenous lands at Kanesatake (Oka, Quebec) (York and Pindera, 1991[6]).

An inquiry of unprecedented scope, the Commission published a number of interim studies, and a five volume final report that offers a reinterpretation of Canadian history with Indigenous relations at the centre, and recommendations covering virtually every outstanding issue in that relationship –from health to veteran’s affairs to land rights and treaties. The Commission envisioned a new relationship between Indigenous nations and peoples and the Crown and Canadian governments, captured in the phrase ‘nation-to-nation’. By this the Commission meant a relationship characterised by mutual recognition, mutual respect, sharing, and mutual responsibility. “Aboriginal governments” were understood to be one of three orders of government in the federation.

The federal response to the Royal Commission came in early 1998. Gathering Strength: Canada’s Aboriginal Action Plan avoided using the term nation-to-nation, preferring to speak of “partnership” among Aboriginal people, other levels of government, and the private sector. Other sections of Gathering Strength affirm the inherent right of self-government, the treaty relationship, and the importance of recognizing “Aboriginal governments” but avoided explicit recognition of original Indigenous sovereignty. A Statement of Reconciliation endorsed the version of Canadian history put forth by the Commission and acknowledged the harm that had been done by Indian Residential Schools. Ultimately, after legal action by the Assembly of First Nations and more negotiation, a formal apology was issued, a compensation program was rolled out, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was struck, reporting in 2015.

The TRC offered an opportunity to the hundreds of people who were directly and intergenerationally affected by the residential school system and the abuses there to speak of the harm that was done to them. It exposed this history to the general Canadian public, and in issuing 93 calls to action, galvanised many segments of Canadian society - as well as governments and public institutions - into action. This process continues.

Another watershed moment occurred in 2015 when the newly elected Trudeau government committed to progress in Indigenous affairs. This was followed by a number of actions, beginning with the inclusion of the following sentence in all Ministerial mandate letters:

No relationship is more important to me and to Canada than the one with Indigenous Peoples. It is time for a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples, based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership.

In May 2016, Canada announced its full support, without qualification, of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In April 2017 Canada formally retracted its concerns regarding paragraphs 3 and 20 on the 2014 Outcome Document from the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples.

Box 1.2. Reconciliation—a Canadian project moving from words to actions: What will it take to implement?

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government mandate letters and 2015 speech to the Assembly of First Nations Special Chiefs Assembly marked a change in tone and signified a new era that has the potential to transform its relationship with Indigenous peoples.

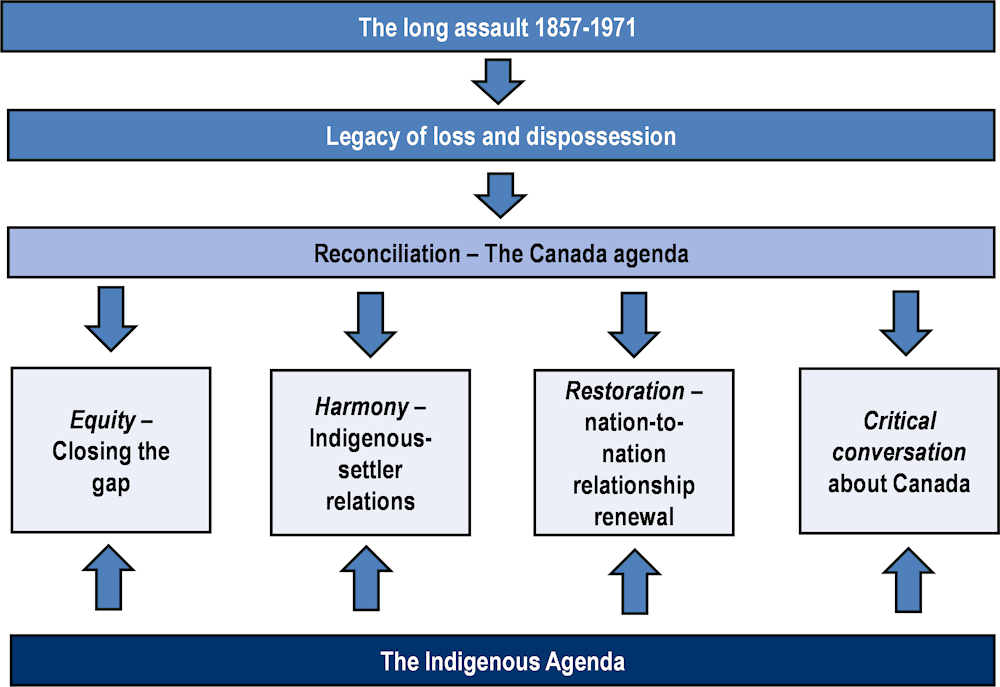

As noted by Newhouse (2016[4]), the story of Indigenous peoples is predominately told through the lens of colonisation: the historical period from the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857, which encouraged Indians to assimilate into Canadian society through the process of enfranchisement and adoption of European values, to the withdrawal of the much-criticised White Paper Statement of Indian Policy in 1971. Throughout this period, public policy-makers saw Indigenous peoples as a ‘problem’. As a result, Indigenous people endured more than a century of assault on their lands, economies, cultural practices, knowledge and identities.

Reconciliation has become the public policy focus for addressing the impact of this legacy. It consists of remedial efforts designed to close quality-of-life gaps and improve the relationship between Indigenous and other peoples within Canada and governance actions intended to bring Indigenous peoples and their institutions into the structures and processes established for Canada. Part of this undertaking is a critical examination of Canada itself, and this requires an understanding of the political goals of Indigenous peoples.

A large number of governments, agencies and organisations are now taking steps to address particular calls to action within their mandates. Indigenous peoples had little or no influence upon the public policies that animated the ‘Long Assault’ (the period between 1857 and 1971). While Indigenous peoples expect to have significant influence over the policies that will lead to a reconciled Canada, it would be unfair to place the burden of reconciliation upon them. Those who lead Canada’s public institutions need to spearhead the reconciliation effort and work to expand support for change within Canadian society as a whole.

Figure 1.1. The four aspects of reconciliation as envisioned by Indigenous leaders

Source: Newhouse, D. (2016[4]), “Indigenous peoples, Canada and the possibility of reconciliation”, http://irpp.org/research-studies/insight-no11/ (accessed on 13 December 2018).

These are important changes in direction from political leadership. There have also been some important institutional changes. In August 2017, the federal government announced the dissolution of the old Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, and the creation of two new ministries explicitly modelled on a recommendation of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. The Department of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs will have responsibility for whole-of-government coordination and creation of the new relationship between federal authorities and Indigenous peoples (“nation-to-nation, Inuit-Crown, and government-to-government”). The second ministry, of Indigenous Services, will be given responsibility for improved service delivery and eventual transfer of service delivery to self-governing Indigenous authorities.

Table 1.1. Selected policy milestones in Indigenous-Crown relations

|

1763 |

Royal Proclamation affirms Indigenous land right and Crown prerogatives |

|

1764 |

Treaty at Niagara ratifies Royal Proclamation |

|

1867 |

Confederation through the British North America Act creates the Dominion of Canada |

|

1869 |

Indian Act consolidates earlier legislation, embedding colonial law |

|

|

Métis Provisional Government constituted in the Red River Settlement |

|

1871 |

Treaty 1 concluded |

|

1885 |

Métis resistance defeated; Riel hanged |

|

1921 |

Treaty 11, last numbered treaty, negotiated |

|

1927 |

Indian Act amended to prohibit fund-raising for political purposes |

|

1951 |

Major revision of Indian Act |

|

1960 |

Federal franchise extended to Status Indians |

|

1969 |

White Paper on Indian Policy |

|

1973 |

Calder et al. v. Attorney-General of British Columbia [1973] Supreme Court decision: Acknowledged Aboriginal title is an existing Aboriginal right and provided legal grounding for the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. |

|

1975 |

James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement—first modern treaty |

|

1982 |

Patriation of the Constitution |

|

1985 |

Some gender discrimination removed from Indian Act |

|

1990 |

Crisis at Kanesatake (Oka) over land rights |

|

1992 |

Charlottetown Accord defeated |

|

1995 |

Inherent Right to Self-Government Policy responds to Supreme Court decisions |

|

1996 |

Final Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples |

|

1999 |

Nunavut Territory created pursuant to modern treaty |

|

2015 |

Final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada |

|

2016 |

Canada announces its full support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples |

|

2019 |

The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls |

Key debates in Indigenous peoples’ economic development

Contemporary controversies and political issues are a legacy of the contest over land prompted by European “discovery” of the new world and its settlement. Settlement patterns, state formations, industrial structure and political culture have all been forged by this history. Three contemporary areas of debate and discussion are consequences of this history:

Self-government and the movement to remove Indian Act administration.

Challenges of economic development and the long shadow of conflicts over land use and capitalist development.

The ways in which Indigenous knowledge can inform public policy, particularly environmental and economic decision-making.

The origins and basic shape of the 21st century Indian Act lie in British colonial policy. Indigenous peoples’ continuing desire to both protect their lands and earn their livings from them lie behind contemporary conflicts over land use and resource development – and attendant dilemmas in Indigenous communities about how to manage these. Many wish to do this from within the values and relying upon the insights of their own cultures, even while they work through the institutions of democratic government that structure Canadian political life.

Getting out from under the Indian Act

The Indian Act has no defenders. It is widely recognised that the lineaments of the unjust period of colonialism are baked into every section and clause. The Indian Act was an instrument of containment and control, aiming at the extinction of Indigenous peoples as peoples, and is irredeemable.

Yet repeated attempts to abolish the Indian Act have met with resistance from First Nations. There are a number of reasons for this. First, and probably most importantly, First Nations’ history of relations with state institutions has given them little reason to be optimistic about a radical change to their legal condition designed and imposed from outside. Changes will have to be led by the people they will affect. Second, for First Nation people as for other Canadians, the most proximate order of government is the most visible and the most important. The Indian Act has structured political life on reserves for seven or eight generations. It is familiar. Third, the Act has long embodied First Nations’ relationships with federal institutions, so that it has become associated with treaty rights, security of land tenure on reserves, and the federal fiduciary responsibility. If it is abolished, what will happen to these? Finally, there is the matter of building an alternative constitution. While in most places traditional political institutions and values have survived, they have been pushed aside or driven underground. Even if the prohibitions on traditional governance practices have been expunged from the Indian Act and federal policy, it is challenging to understand how they might be built and adapted into a modern government capable of interaction with other orders.

Beyond several unsuccessful (and well-intended) efforts by federal leaders to unilaterally abolish the Indian Act,27 there have been a number of efforts over the years to establish “paths” for First Nation governments to follow as they work their way out from under the Indian Act. These include the 1996 Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management ratified by the 1999 First Nations Land Management Act (FNLMA), which delegates certain land management responsibilities under the Indian Act to Band Councils, which eliminates the need to seek Ministerial approval on lands-related decisions. The 2006 First Nations Fiscal Management Act (FNFMA) provides a legislative and institutional framework allowing Fist Nations to exercise jurisdiction over core government functions and supports their socio-economic development goals. This Act established three institutions:

The First Nations Financial Management Board supports Indigenous governments to implement financial administration laws for good governance and sound financial management.

The First Nations Tax Commission advances Indigenous taxation, including property taxation and local revenues generation.

The First Nations Finance Authority enables Indigenous governments to access capital through the bond market at rates comparable to other levels of government.

Box 1.3. An evolving framework for First Nations land management: The First Nations Land Management Act

The Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management and the First Nations Land Management Act (FNLMA) establish a legislative framework for the direct and autonomous governance of reserve lands by First Nations. In 1991, a group of First Nation Chiefs approached the Government of Canada with a proposal to opt out of 33 provisions in the Indian Act pertaining to land and resources. This proposal led to the negotiation of the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management by 14 First Nations and Canada in 1996, and later ratified in 1999 by the First Nations Land Management Act. In December 2018, amendments were passed to the FNLMA that contain Canada’s first reference to a commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in a piece of legislation.

The Framework Agreement led to the establishment of the Lands Advisory Board and Resource Center to assist the 14 First Nations in implementing their own land management Regime. Under First Nations Land Management, responsibility for the creation, administration, and enforcement of laws governing the management of reserve land, environment and resources is transferred to First Nations when a community-developed land code comes into effect. First Nations operating under their own land codes cannot return to Indian Act land management.

As of October 2019, 79 First Nations are operating under their land code, 55 First Nations are working to develop a land code and a further 10-15 First Nations will be voting to ratify their land code in the next 12 months.

After a First Nation begins the process of assuming jurisdiction under First Nation Land Management, it receives two types of funding:

Developmental funding for establishing a land code, negotiating an individual agreement and holding a ratification vote.

On-going operational funding for managing land, natural resources and environment, as determined by a formula and set out in the individual agreement.

The implications of this new framework for First Nations land management is discussed at length in Chapter 3.

Source: Background questionnaire.

There has been some interest in both paths. Out of a total of 619 First Nations recognised by the Government of Canada, 84 operate under the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management and the FNLMA and 54 are actively working towards this. Under the FNFMA: 282 First Nations have opted in and 125 First Nations are collecting property tax generating over $66 million annually.

Since 1995, a third path has existed –the negotiation of self-government agreements. These now exist in great variety, not all of which have been negotiated by First Nation governments.28 There are 26 Comprehensive Land Claim agreements and four standalone Self-Government agreements.29 Of the 26 Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements, 18 include Self-Government provisions or have accompanying Self-Government Agreements. The self-government agreements that have been negotiated to date are relatively few in number, and they are extremely heterogeneous. Some self-government agreements are explicitly recognised as treaties under Section 35 of the Constitution Act (Deline Agreement), while others are explicitly excluded (Sioux Valley Dakota). Some are government-to-government agreements intended to provide a vehicle for an Indian Act administration to work out from under the Indian Act, while others complement existing comprehensive claims agreements (that have supplanted the Indian Act) with government-to-government arrangements. The Tlicho Agreement concluded in 2005 includes both land and governance provisions in one document –that is, it is both a comprehensive land claim agreement and a self-government agreement. At the other extreme, there are sectoral self-government agreements. For example, under the Mi’kmaq Education Partnership, the members of Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey (a coalition of twelve First Nations) control and deliver education to their citizens. Similarly, the Anishnabek Nation (Union of Ontario Indians) has the Anishinabek Educational Institute.

None of three ‘paths’ (the FNLMA, the FNFMA, the Inherent Right to Self-Government policy) represent in themselves a radical break with the Indian Act, but they do create a somewhat different opportunity structure for the many First Nations who choose to begin to move out from under the Indian Act. A fourth path can also be considered. One that includes First Nations-directed and/or led solutions for all new legislation affecting First Nations (e.g., the proposed Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act), further supported by permanent bi-lateral mechanisms between the Government of Canada and First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation leaders as well as joint Canada-Indigenous working groups.

Independent of government policy initiatives, there is a growing grassroots movement for internal development and change towards self-government. This movement is rarely covered in news reporting and can be difficult to spot from a distance, but it is Canada-wide. Indigenous organisations working in this field include the Centre for First Nations Governance, a corps of Indigenous researchers and community developers who have been working with First Nations on governance issues for nearly twenty years, the Indigenous Leadership Development Institute which offers a curriculum of professional development courses to First Nation and other Indigenous organisations, and the newly formed think tank, the Yellowhead Institute at Ryerson University.30 Putting these developments together with the expansion of university programs in the fields of Indigenous studies and Indigenous governance and the growing cohort of Indigenous students, it seems likely that grassroots movements to displace the Indian Act and to build healthy community governance practices rooted in recovered Indigenous traditions and language will grow.

An outstanding question remains: by what means and on what schedule will the efforts to transform the federal administration of Indigenous affairs keep pace with both the current political direction from above, and the pressures for change from First Nation communities? To date, none of the top-down initiatives to supersede the Indian Act have gone very far, in part for the reasons mentioned above, but also because they have not broken with the ethos of central control, a conditioned response that is buttressed by the doctrine of ministerial responsibility. Until Ministers of the Crown replace this responsibility with practical nation-to-nation and government-to-government relations, the spirit of the Indian Act will animate administrative behaviour.

Conflicts over land and land management

Land, and sovereignty over land, is at the heart of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Crown (see Chapter 3 for in-depth discussion). Indigenous peoples, and initially the Crown, used treaties to establish appropriate diplomatic relationships and to agree upon a protocol for sharing use of the land. As is well known, many provisions of the treaties were not respected, particularly the provisions concerning shared land, and particularly by the provincial governments whose constitutional reliance upon “Crown land” for revenue provided an incentive to ignore treaty rights. Provincial governments have generally taken the position that whatever the wording of the treaty, all lands except the small portion of Indigenous peoples’ traditional territory allocated for a reserve, are to be seen as Crown lands (or waters) and are open to provincial disposition.31 It seems likely that recent Supreme Court of Canada decisions will be undermining this position (see Tsilhqot’in decision discussed above) but this process is just beginning. Of as yet unknown impact is the legislation currently before Parliament that will require that all Canadian laws be brought into harmony with the UNDRIP. In this discussion, Article 21 is pertinent:

Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.

States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilisation or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources.

States shall provide effective mechanisms for just and fair redress for any such activities, and appropriate measures shall be taken to mitigate adverse environmental, economic, social, cultural or spiritual impact.

These provisions are in line with the trend in Canadian jurisprudence, but there are still many outstanding matters of implementation. And while these matters are forward-looking, there remains a need to redress errors of the past.

Since 1973, these actions and federal treaty violations have been subject to review through the specific claims process. The specific claims process addresses “claims made by a First Nation against the federal government which relate to the administration of land and other First Nation assets and to the fulfilment of Indian treaties, although the treaties themselves are not open to renegotiation” (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2016[7]).

The modern treaties that have been negotiated since 1975 have provisions that make them less likely to be disregarded. Each modern treaty is detailed and specific, and each is given effect by complementary legislation. It is accepted that the treaty must be respected by both orders and all branches of government, though this has not always been done.

The modern treaties set up procedures for decisions about land use, by specifying the degree of control each signatory has over categories of land in the Indigenous nation’s traditional territory, and frequently through a system of co-management boards, appointed jointly by the Indigenous parties to the treaty and the relevant other orders of government. Self-government agreements also contain environmental chapters, which bestow Indigenous governments with the responsibility to create environmental protection laws, which can encompass pollution, waste management, water quality, air quality, etc. In addition to treaty land management, national parks are also created pursuant to modern treaties and provide another example of effective co-management.

Such measures do not eliminate conflict but they do provide regularised means for resolving it.32 An example of such boards is the Nunavut Impact Review Board, established under the Nunavut Agreement to review and make recommendations concerning all major development projects proposed for Nunavut. Another with a more specific focus is the Porcupine Caribou Management Board, with specific responsibility to oversee the protection of this herd. There are similar boards in Labrador, Northwest Territories and Yukon. Development proposals which involve interprovincial impact may also be considered by the federal environmental assessment panels, and the National Energy Board. Federal procedures are being revised currently as Bill C-69 moves through Parliament. Land use conflicts also arise between municipal governments and neighbouring Indigenous nations. There are far fewer mechanisms for resolving these peacefully.33 The 1990 armed confrontation at Kanesatake/Oka mentioned earlier was prompted by a municipal government’s interest in constructing a golf course in Mohawk traditional territory and the standoff at Caledonia Ontario over the construction of a subdivision on Haudenosaunee lands are just two examples (York and Pindera, 1991[6]; DeVries, 2011[8]).

Sometimes conflict over land use is primarily a matter of property rights, as in the 1995 Ipperwash Crisis, where members of the Stoney Point Ojibway Band sought to regain lands that had been appropriated from their reserve during the Second World War under the War Measures Act. Instead of being returned after the war, the reserve land was converted to a provincial park. After a prolonged standoff, the shooting death of one of the protesters, and a public inquiry, the land was returned to the Stoney Point Band in 2016.

Conflicts over land and land management are also apparent where the rights of hereditary chiefs are not considered in developments on their traditional land. A present example of this conflict the case of the Gidimt’en of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline in British Columbia. It is the position of TransLink Canada – owners of the Coastal gas pipeline – the Impact Benefit Agreement that they have signed with the elected Wet’suwet’en band council permits them to proceed with the construction of the pipeline across Wet’suwet’en traditional territories. While bands derive their authority from the Indian Act, and were originally created as a means for Canadian authorities to better control Indigenous communities, Wet’suwet’en hereditary authority is embodied in titles passed down through generations and from the distinct relationship between a clan and its territories (McCreary, Tyler; Budhwa, 2019[9]). A 1980s court case on the territorial-rights of Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and their Gitxsan neighbours that eventually rose to the Supreme Court of Canada established that the Tribe’s territorial sovereignty, pending proof of surrender, by treaty, is legitimate.34 However, the provincial government continues to assert the rights to natural resources development across these lands wherein provincial environmental assessments can proceed absent the consent of the hereditary chiefs.

On many other occasions, though, debates over land use and resource management lead into a debate about capitalism and its impact on Indigenous communities. Capitalism is of course a global system, encompassing us all and affecting how every person on the planet makes a living and makes a life. Many Indigenous communities in Canada, though, retain a social memory of other ways of being, and in northern and rural communities, retain also the capacity to make a living more loosely articulated to capitalist relations than is possible for most urban dwellers. The desire to continue to live partly by harvesting (hunting, fishing, gathering) is manifest in human behaviour, and in provisions for resource management and access to lands that are negotiated in modern treaties. In northern Canada, the trade-off between jobs related to resource development and protection of the lands is a sharp one that has been played out in every public hearing on development projects since the Berger Inquiry of the 1970s. The Inquiry report’s title, Northern Frontier, Northern Homeland, says it all.35 The same issues are at play in current debates about the Kinder-Morgan Pipeline expansion, through Indigenous lands, from the Alberta oil sands to the Pacific coast.

Indigenous Knowledge and Economic Development Decision-Making

The roughly synonymous terms Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous environmental knowledge, traditional knowledge, and traditional environmental knowledge have come into common usage over the last four decades, surfacing in debates over the opening of Indigenous lands to non-renewable resource development. The terms generally refer to human understanding (facts, generalisations, theories and explanations) that is particular to and arises from a nation or people’s history, language, economic, political and social practices, and culture. Much Indigenous knowledge is in principle intercultural communicable, but may not be entirely accessible to those who do not speak the appropriate language.