The objective of this chapter is to assess and provide recommendations about how to improve the ways Indigenous peoples in Canada secure and use land. The chapter starts by offering an historical contextualisation of Indigenous lands and explores how they can promote community development. The second section sets out the Indigenous land rights framework in Canada, which differs between First Nations, Métis and Inuit. The chapter then explores how treaty rights have evolved in recent years and outlines mechanisms to expand the land base. Following this, the chapter examines how Indigenous groups can better manage land, participate in or undertake land use planning, establish objectives for community development and obtain revenues from land. The chapter ends with a discussion of Indigenous land rights in relation to natural resource development projects, including frameworks for participation and consultation.

Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development in Canada

Chapter 3. The importance of land for Indigenous economic development

Abstract

Key findings and recommendations

Key findings

Land is a fundamental asset for sustainable economic development for Indigenous peoples, and land rights are critical for self-determination.

Indigenous peoples in Canada disproportionately continue to have a small, fragmented land base, with limited commercial and residential use, limited natural resources, far from urban centres and with limited ability to expand.

Indigenous peoples have different levels of property rights over different lands (reserves, fee simple land, and modern treaty lands), and have mechanisms available to obtain these lands. In recent decades, these mechanisms have been utilised to increase the Indigenous land base.

Security of tenure is associated with improved economic outcomes. Opportunities for development vary according to the land base and the defined land rights regime, as well as by location, proximity to service centres, population size, resource endowment and institutional capacity.

There are a range of tools that can be implemented in the Indigenous land tenure system to empower Indigenous peoples and improve economic development outcomes (including land use planning, leasing, and certificates of possession). There are opportunities to improve the efficiency of these tools, and build the capacity of Indigenous groups to utilise them.

Once land tenure is secured, it provides the basis to negotiate benefit sharing agreements with project proponents. These agreements can be a catalyst for development if they are linked to a community plan, have dispute resolution mechanisms, and provide for project closure and remediation.

Key recommendations

Improve the framework for Indigenous peoples to secure land through the comprehensive land claims policy by:

Ending the practice of requiring that Indigenous rights holders extinguish their inherent and/or treaty rights as a prerequisite for an agreement.

Supporting Indigenous groups with the capacity to effectively undertake negotiations.

Developing independent and ongoing monitoring mechanisms in order to ensure that the commitments made by the Government of Canada in comprehensive land claim agreements are met in a timely and effective manner.

Develop better procedures for First Nations to increase existing reserve land through the Treaty Land Entitlements and State-assisted land acquisition processes by:

Tracking the overall time it takes to convert lands to reserve status and demonstrate progress periodically—report publicly and include in departmental performance indicators.

Working closely with First Nations to assist them in their efforts to resolve third-party interests.

Undertaking a national audit of surplus government land to identify opportunities for set asides.

Establishing a portfolio of land to be made available for future land claim settlements.

Establishing a shared national/provincial programme of land purchase.

Develop better tools for Indigenous groups to use land by:

Providing legal templates for opting First Nations to start building their land codes and associated regulations in order to facilitate the law enactment, reduce the need to resort to external consulting, and avoid the proliferation of unique property rights regimes (within the framework of the FNLM Act).

Ensuring community plans detail which land can be available for leasing and land codes regulate intended use and accepted levels of nuisance.

Ensuring there are mechanisms in place for Indigenous communities to have meaningful consultation with regards to the land use planning of municipal and other authorities that have jurisdiction on or near their traditional territories.

Strengthen the negotiating power of Indigenous groups in the context of impact-benefit agreements (IBA) by:

Providing all the necessary information on environmental conditions, sub-surface resources, land uses, competing economic interests and other elements that Indigenous groups may not be aware of.

Referring companies to a legitimate regional or national Indigenous organisation that can serve as the contact point with local groups.

Elaborating a common set of tools and templates from which Indigenous groups can draw to start negotiations.

Facilitating workshops among Indigenous negotiators and leaders to share experiences and good practices in agreement-making.

Land. If you understand nothing else about the history of Indians in North America, you need to understand that the question that really matters is the question of land. Thomas King, The Inconvenient Indian (2012), pg. 218.

Land is a fundamental asset for sustainable economic development. This is no different for Indigenous communities in Canada and it is a reason why land rights are critical for self-determination. However, land is much beyond just an economic asset for Indigenous peoples. Land provides sustenance for current and future generations; it is connected to spiritual beliefs, traditional knowledge and teachings; it is fundamental to cultural reproduction; moreover, commonly held land rights reinforce nationhood.

The history of Indigenous lands in Canada is one of disposition and isolation. Indigenous land rights in Canada have been strengthened by successive court cases and administrative processes that have evolved to better address such issues as expanding the land base. Despite this, Indigenous rights frameworks are by no means settled and they remain one of the most politically contentious issues to this day. Major infrastructure projects such as the expansion of the Trans Mountain oil pipeline have been halted by unanimous decision of the federal court of appeal because of the government of Canada’s failure to address the concerns of some First Nations.1 And yet, the extent to which First Nations are able to assert their rights over their land remains unclear – particularly when those rights come up against major developments of national interest.

This chapter explores how Indigenous groups access, protect and use land in Canada according to their own objectives, respecting the principle of self-determination. The chapter primarily focusses on First Nations and Inuit land rights and land management. Since the 1970s, modern treaties and self-governance agreements have been signed between the Crown, the province or territory and Indigenous peoples. Taking this historical evolution into consideration, the report traces a path of advancement and points out areas for further improvement. The recent recognition of Métis land rights is briefly discussed, too.2

The chapter proceeds in five parts. The first section offers historical contextualisation of Indigenous lands and explores how they can promote community development. The second section sets out the Indigenous land rights framework in Canada, which differs between First Nations, Métis and Inuit. The third section explores how treaty rights have evolved in recent years and outlines mechanisms to expand the land base. Following this, the chapter examines how Indigenous lands can support sustainable economic development. More precisely, it investigates how Indigenous groups can better manage land, participate in or undertake land use planning, establish objectives for community development and obtain revenues from land. The chapter ends with a discussion of Indigenous land rights in relation to natural resource development projects, including frameworks for participation and consultation. Throughout, the chapter offers recommendations on how to strengthen the Indigenous land rights regime and governance in Canada.

Land: From dispossession to ongoing reconciliation

Land rights are a contentious issue, but necessary to achieve reconciliation

The delimitation, access and right to land and waters by Indigenous peoples3 is one of the most contentious political issues in Canada. Not every Indigenous group has the right to land assured, up to today. For instance, non-Status Indians are not considered members of reserves and cannot claim lands, while for the Métis, who are one of the three Indigenous peoples of Canada, the very existence of land rights remains disputed (Drake and Gaudry, 2016[1]). Treaty renegotiation takes place in Canada today. Other groups are currently negotiating treaties for the first time – more than 70 are under negotiation as of September 2019. Furthermore, when land rights are defined, it remains to be decided on a case-by-case basis whether development projects can take place or not. The extent to which Indigenous peoples have the right to be consulted about or to veto projects in their traditional territories is disputed (Land, 2016[2]). Controversial cases such as the expansion of Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline corroborate this point. The company has negotiated benefit agreements with 43 Indigenous communities out of a total of 133 affected by the project, but consent is far from being reached: 53 First Nations in British Columbia have formed a treaty alliance against the project, and other First Nations have signed a petition against the project.4

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission makes some Calls to Action about land rights, albeit not dealing extensively with the issue (TRC, 2015[3]). The Call to Action 45 urges the Government of Canada to jointly develop with Aboriginal peoples a Royal Proclamation of Reconciliation to be issued by the Crown. It called on the Government of Canada to:

Adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which the Government did in 2016, and implement the Declaration as the framework for reconciliation.

Repudiate concepts used to justify European sovereignty over Indigenous lands and peoples such as the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius (see definition on Box 3.1 below).

Renew or establish Treaty relationships based on the principles of mutual recognition, mutual respect, and shared responsibility for maintaining those relationships into the future.

Reconcile Aboriginal and Crown constitutional and legal orders to ensure that Aboriginal peoples are full partners in Confederation, including the recognition and integration of Indigenous laws and legal traditions in negotiation and implementation processes involving Treaties, land claims, and other constructive agreements (TRC, 2015[3]).

Indigenous title to land pre-exists colonisation and European Laws. By virtue of historical occupation and customary law, Indigenous peoples in Canada are dutiful holders of their traditional lands. In this sense, Treaties should be honoured, renegotiated when needed and negotiated where non-existent and this process should be guided by the principles of mutual recognition and respect, rather than dominance, as was often the case in the early days of treaty making in Canada. By force of the Call to Action 45 and its interpretation, Indigenous land rights compose the Reconciliation and Truth project.5

Box 3.1. Dispossession and subjugation: The role of the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius

15th century English legal scholarship forwarded the Doctrine of Discovery, with long lasting ramifications for Indigenous rights. The Doctrine provided that newly arrived Europeans immediately and automatically acquired legally recognised property rights over Indigenous lands and also gained governmental, political and commercial rights over the inhabitants without the knowledge or consent of Indigenous peoples.

The notion of terra nullius, meaning empty or void land, is one of the key elements of the Discovery Doctrine. The Doctrine argues that the lands that were not possessed or occupied by any person or nation, or were occupied by non-Europeans but not being used in a fashion that European legal systems understood or approved were considered empty and available to be claimed. Indigenous lands fell into the category of not being governed according to European laws and cultures, and were thus available for Discovery claims. Moreover, given the nomadic nature of many Indigenous Nations, lands may have appeared empty and available but were actually part of the traditional lands used by Indigenous groups.

The Doctrine has been severely criticised as a fictional justification of the European colonisation and of the subjugation of Indigenous peoples and lands around the world. Despite this, it is only in recent decades that the governments and courts of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States have sought to overcome this Doctrine of land dispossession.

Source: Adapted from Miller, R. et al. (2010[4]), Discovering Indigenous Lands, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199579815.001.0001.

Historic dispossession of Indigenous lands has resulted in limited reserve land

Colonialism left a legacy of economic dependency and a situation of relative deprivation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada (Alfred, 2009[5]). Land allocation policies have been part of this process by establishing reserves and assigning Indigenous peoples to confined and isolated tracts of land. The Final Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the most comprehensive study to date on this matter, identifies land dispossession as one of the root causes of this condition (RCAP, 1996[6]). The Parliament of Canada has recognised that “the alienation of land and resources has been a major contributor to the economic marginalisation of Aboriginal peoples in Canada” (Parliament of Canada, 2012, as cited in (PRA, 2016[7])). The Government of Canada has signalled that a sufficient land base, local governance and community capacity are fundamental conditions for community economic development (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Conditions for community economic development

|

Land base |

A sufficient base of useable land as part of the community's physical assets, which may include land appropriate for conventional economic development, land suitable for traditional pursuits, and land for community purposes such as housing and recreation. |

|

Local Governance |

Having in place rules and systems that work so that community governance, land management, and other necessary elements of the day-to-day operation of community affairs are effective and efficient and create accountability, credibility, and fairness. A high degree of control over local decision-making, which results in First Nations having the necessary autonomy and freedom to pursue their own goals, in their own way, and arises from timing and methods that make sense for the local conditions and for the goals and aspirations of their community. |

|

Community capacity |

A level of community capacity that results in community members having the abilities, skills, and sense of influence necessary to undertake change in their community. |

Source: AANDC (2013[8]), Creating the Conditions for Economic Success on Reserve Lands: A Report on the Experiences of 25 First Nation Communities, https://www.aadnc‑aandc.gc.ca/eng/1372346462220/1372346568198#tab16 (accessed on 30 November 2018).

Throughout Canadian history, Indigenous peoples have been dispossessed of their traditional territories and forcefully moved to lands in worse locations or of inferior quality in order to make way for the growth of the settler society. When reserves were created, they were generally located away from the best lands in terms of agriculture and trade as the settler population expanded (RCAP, 1996[6]). Consequently, many reserve lands have little natural resources and are located at great distance from major population centres. As of 1996, almost 80 per cent of First Nations were located more than 50 kilometres from the nearest access centre (RCAP, 1996[6]).

Indeed, while representing 4.9% of the total population, Indigenous peoples hold around 626 000 km² or 6.3% of the total landmass of Canada. Most of it lies north of the 60th parallel, whilst in the southern provinces, which are home to approximately 95% of all Indigenous Peoples within Canada, only 37 000 km² are held by Indigenous groups, that is 0.5% of Canada’s land mass (Göcke, 2013[9]).

In short, Indigenous lands disproportionally have disadvantageous attributes, which include:6

Small Land Base: Approximately 0.5 % of the Canadian land mass south of the 60th parallel.

Limited Commercial and Residential Use: The federal land allocation policy has largely allocated reserve lands away from high quality and urban lands as the population expanded.

Patchwork Nature: 80 per cent of First Nations reserves are below 500 hectares in size, which makes it harder to establish infrastructure, development projects and viable businesses.

Limited Natural Resources: Reserve lands generally have low agricultural or mineral potential.

Limited Territorial Expansion Ability: The ability of band councils to expand their land base is reduced, albeit policies such as Additions to Reserve and Specific Claims negotiation process seek to expand these possibilities.

Effects of nearby activities: Surrounding activities and development in close proximity to reserves can place pressure on reserve boundaries and/or cause environmental degradation on or around the reserve.

In the face of this evidence, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP, 1996[6]) concluded that a reliable land base is a pre-condition for autonomous self-governance. A significant expansion of lands owned and controlled by Indigenous peoples would provide a reasonable basis for achieving economic self-reliance (Alfred, 2009[5]). It would contribute to a more effective use of taxation powers, which have been greatly affected by the abovementioned land allocation policy (Belley, 2000[10]).7 Economic independence is an important pre-condition for sustainable self-governance regimes.

More than 20 years after the publication of this major study, these conclusions hold true. Indigenous peoples in Canada disproportionately continue to have a small, fragmented land base, with limited commercial and residential use, limited natural resources, far from access centres and with limited ability to expand. The fair and prompt resolution of outstanding land claims would significantly address this problem. In addition, instruments to expand the land base must be consistently adopted, which are treaty-making, comprehensive claims policy, specific claims policy, land acquisition in the market, Additions to Reserve, right to pre-emption and facilitated land purchases.

Métis title is pending broader recognition

Métis were first recognised as a distinct right-holding group with the passage of the 1982 Constitution Act. Section 35 of the Constitution Act affirmed existing Aboriginal and treaty rights and recognised Métis as one of the three distinct Indigenous groups in Canada, alongside the Indians and the Inuit. In 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada set a legal test for rights-bearing Métis communities and recognised that Métis have broader hunting rights on traditional territory (Powley decision). Refer to Chapter 1 for this discussion.8

The Métis did not enjoy a distinct land base from which to strengthen their identity and culture or govern themselves as First Nations in reserves did. Historically, the only exception is the province Alberta, where there is a unique history of Métis. A provincial legislative basis for the establishment of the Métis Settlements was successfully negotiated under the Métis Population Betterment Act of 1938. The eight Métis Settlements of Alberta (Buffalo Lake, East Prairie, Elizabeth, Fishing Lake, Gift Lake, Kikino, Paddle Prairie and Peavine) comprise 1.3. million acres of land and have a population of around 5,000 people.

Apart from that, federal government policies related to Indigenous lands have not included Métis. Until today, the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy does not include the Métis. Likewise, the Specific Claims Policy is restricted to First Nations dealing with historical grievances related to historic treaties and land management. The Addition to Reserve process anticipates consultation to Métis, but has reportedly been defective. Special Claims from the Métis may be accepted in a case-by-case basis, but the lack of a standard procedure renders decision-making more lengthy, complex and ambiguous. In all, the Métis did not benefit significantly from these policies, except when they had other Indigenous groups by their side. For instance, in 1993, the Sahtu Dene and Métis signed a Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement which, among other provisions, granted title to 41,437 square kilometres of land in the Northwest Territories.

Given the lack of recognition of Métis title in government policies, Métis have resorted to the Courts. In the Manitoba Metis Federation decision, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the federal government had failed to appropriately carry out its promise in the 1870 Manitoba Act to set aside 5 565 square kilometres of land for the 7 000 children of the Red River Métis. Besides recognising the breach of treaty, which in itself has major significance, the Manitoba Metis Federation decision set ground for reconciliation. In November 2016, the Manitoba Métis Federation-Canada Framework Agreement on Advancing Reconciliation was signed.

In all, Canada has recognised Métis rights by different levels. In 2019, for instance, the Government of Canada signed Métis Government Recognition and Self-Government Agreements with the Métis Nation of Alberta, Métis Nation of Ontario and the Métis Nation of Saskatchewan. The agreements address core governance issues such as leadership selection, internal operations and citizenship. Commenting on these agreements, Thomas (2016) notices that future developments on these agreements may allow a more comprehensive analysis about where the recognition of Métis land rights is heading.

To conclude, Thomas (2016), in the Report “A matter of national and constitutional import: report of the minister’s special representative on reconciliation with Métis: section 35 Métis rights and the Manitoba Métis Federation decision”, recommends that Canada develops a policy to expressly address Métis Section 35 rights claims and related issues, founded on the legal principle of reconciliation. Moreover, because the Crown as a whole, federal and provincial, is accountable for its obligations to Métis as Section 35 rights-bearing Aboriginal peoples, the Report recommends them to work together to develop a joint process by which to address unresolved Métis Section 35 rights claims and related issues (Thomas, 2016).

For Indigenous peoples, land has spiritual and cultural value, beyond a utilitarian view

Access to land is a condition for Indigenous development, however conceptualised. Considering that Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination and the right to development, only they can determine if and how to use their traditional territories. They are the ones to establish how eventual uses collide or not with their worldviews, spiritual beliefs and cultural practices. Right to land can increase autonomy, generate revenues and create economic opportunities, but it can also be used without any direct monetary benefit, for environmental conservation and cultural preservations. Indigenous peoples ought to reconcile these goals, depending on how they relate to and connect with land.

The manner in which land is thought about and used by Indigenous peoples goes beyond that of conventional (Western) conceptions of land as an economic asset. The spiritual beliefs and worldviews of Indigenous peoples are deeply rooted on their connection with land and often with related subsistence activities of hunting, fishing and gathering. Access to or ownership of land can also orient social relations including rules for leadership, marriage, inheritance and group belonging. Indigenous stewardship of land contributes to environmental preservation and biodiversity. Access to land puts Indigenous people in stronger negotiation position to leverage and protect their interests. These different aspects do not exclude, but complement one another. Land rights are therefore crucial to the maintenance of the collective identity of Indigenous groups.

Understood in these terms, the right to land ought to be held collectively.9 Collective land rights are crucial for the preservation of Indigenous peoples’ identities and for their subsistence as such. In some circumstances, e.g. in cities, it may be more convenient and even necessary to own land individually. Furthermore, individual interests to land may be allocated, without disrupting the collective nature of the land title. Internal sub-divisions of land may facilitate housing construction and maintenance, propel business development and create bankable interests on land, e.g. via leasing.

… [R]esorting to a private property regime only promises to shift Aboriginal economic dependency from the Crown to lenders. This is a subtle way of completing the centuries-old goal of the colonizers – assimilation – now re-packaged as “economic opportunity.” This is not to say that someday an on-reserve private property regime could not be a useful tool in the hands of our First Nations. Reserves near urban centres, equipped with adequate training, education and infrastructure, sufficient land to meet the needs of their members, and reasonable employment rates, may find some advantage to being able to borrow against and even market portions of their lands. It is more difficult to foresee how privatization will assist remote communities. Lands in these territories will lack any significant market value. These are Canada’s most impoverished and troubled reserves, and aside from opportunistic resource companies, little outside interest in these lands exists. (Rowinski, 2010[11])

To conclude this section, access to land and natural resources is fundamental for the material and social reproduction of Indigenous peoples. In the words of the former United Nations Special Rapporteur for Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya: “securing the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their lands is of central importance to Indigenous Peoples’ socioeconomic development, self-determination, and cultural integrity” (Anaya, 2012[12]). The Article 29 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) states that:

1. Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources. States shall establish and implement assistance programmes for indigenous peoples for such conservation and protection, without discrimination.

2. States shall take effective measures to ensure that no storage or disposal of hazardous materials shall take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples without their free, prior and informed consent.

Indigenous land rights frameworks

Indigenous peoples have different levels of property rights over different lands

Colonialism ushered in a governance of land rights regime that was alien to Indigenous peoples and that was imposed upon them. While these legal frameworks have evolved, they, to this day, do not necessarily ‘sit’ easily with Indigenous land governance regimes (including its cultural, spiritual and community-based elements). Thus, the following discussion of land rights frameworks is premised by the acknowledgement that Canadian jurisprudence has defined property in a specific way and evolved from European property rights regimes. As specific land rights regimes have been established to govern “Indian lands” and these too are premised on a western view, they continue to be challenged in court and they continue to evolve.

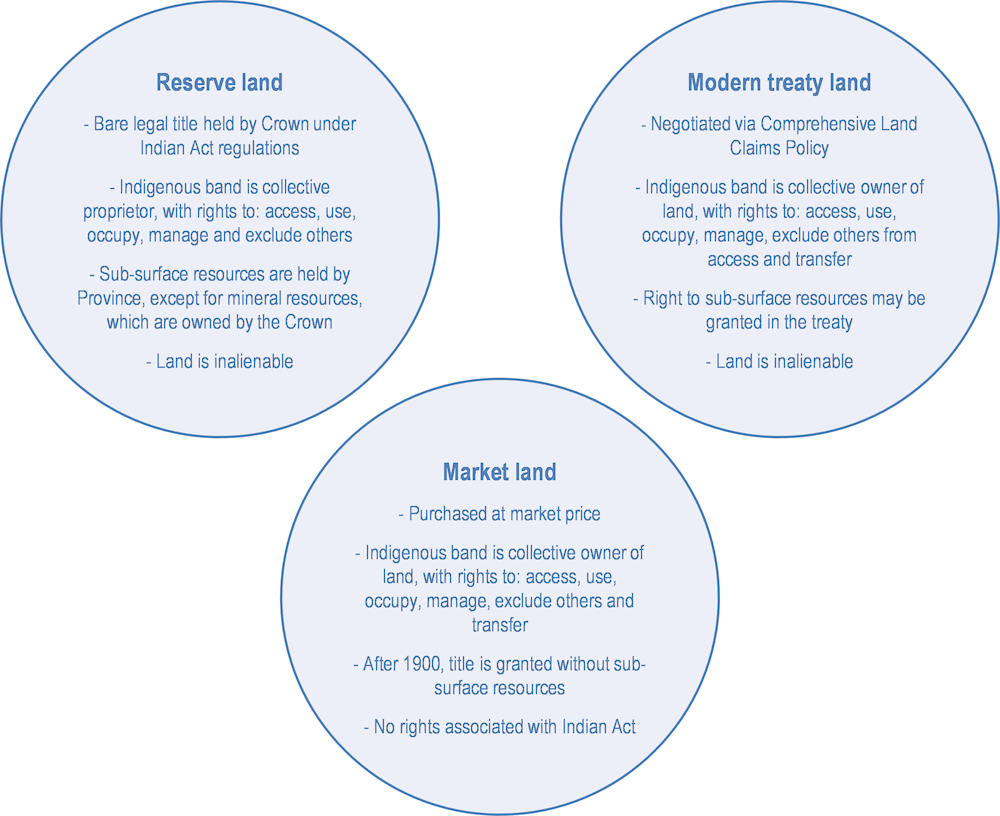

“Land” can be interpreted as encompassing the buildings that sit on it, the air above it and the underground, including water and, sometimes, sub-surface natural resources. “Land” translates into the legal framework as property rights, which express a relation between an individual or a group that holds right to land and the others who do not. As a “bundle of rights”, they are composed of five attributes: access, extraction, management, exclusion and alienation. The owner can access the land and exclude others from accessing, can use the land and enjoy its fruits and can transfer it to third parties, onerously or gratuitously. Indigenous individuals or groups that hold land freely acquired in the market are the rightful owners, but this land does not enjoy the special protection that reserves do under the Indian Act. The proprietor of land does not have the right to transfer land, as it occurs in Canadian reserves, where the First Nations have the right to exclusive use and occupation but the final title to land rests with the Crown.

Historic treaties comprised the creation of federal reserves, which are the most common expression of collective rights to land. The Indian Act defines reserve land as "a tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty, which has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band". As a bare legal title, title is in the Crown but the use, occupation and beneficial interests in the land are set apart for the Indigenous band.10 Once reserves are constitutionally protected (section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982), the federal government cannot unilaterally diminish or take them away. The band council is the proprietor of reserve land, by which they hold the right to exclusive use and occupation, inalienability and the communal nature of the interest. Reserves have exemption from property and estate taxes. According to Statistics Canada, in 2011 there were more than 600 First Nations/Indian bands in Canada and 3 100 Indian reserves.

Indigenous individuals or band councils can also acquire fee simple land in the market, becoming its rightful owners. In this case, land will not have the special protection status granted under the Indian Act. It is subjected to taxation as any other piece of land and can be sold again in the market.

Besides reserves and market-price land, Indigenous peoples may address unresolved title to their traditional territories by negotiating a modern treaty through the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy. Comprehensive land claim agreements can be negotiated in areas where land and resources have not been dealt with previously. They typically take the form of a tripartite agreement between the Indigenous group, the Government of Canada and the province and territorial government. They result on the allocation of ownership rights to land and contain provisions for economic development.

Figure 3.1. Indigenous land rights in Canada

Note: The figure takes into account land rights of First Nations and Inuit recognised and declared by the State. Unresolved Aboriginal title to traditional territories is not included, neither are land rights of Métis.

Harvesting, hunting and fishing rights are collective rights granted in reserve and fee simple lands, and are considered treaty rights. In the territories traditionally occupied by Indigenous peoples which are not part of reserves or owned as fee simple land, fishing and hunting rights, exclusive or not, may still be granted. These traditional activities have cultural, ecological and social value, and are thus important for the collective subsistence of Indigenous groups.11 In the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, for instance, exclusive fishing and hunting rights are attributed in certain lands, where non-exclusive rights are attributed in another one. It may also be the case that Indigenous peoples are given permission by private owners to hunt and fish in their lands.

Ownership of sub-surface resources varies from agreement to agreement. Under the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy, the right to sub-surface resources is not automatically included; rather, the agreement must grant it explicitly. In reserves, sub-surface resources are owned and administered by the respective Province or Territory, which is the regional level of government in Canada (Göcke, 2013[9]). According to the division of governmental responsibilities under the Canadian Constitution, Provincial governments hold authority over natural resources exploitation and might grant the rights to explore sub-surface resources to potential developers. Provincial governments are obliged to consult the impacted Indigenous and neighbouring communities in order to determine the socio-environmental impacts of exploration, and its employment and business opportunities for local residents. Equally applied to the national government and private developers, the duty to consult is discussed at further length in the section on Natural resource development projects and Indigenous communities later in this chapter.

Box 3.2. The largest Aboriginal land claim settlement in Canadian history: The Nunavut Land Claim Agreement

In the 1970s, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (Inuktitut syllabics: ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑕᐱᕇᑦ ᑲᓇᑕᒥ) – a non-profit organisation representing over 60 000 Inuit in Canada, put forward the idea of creating a Nunavut territory. This idea grew over time, culminating in the 1993 Nunavut Land Claim Agreement between the Tunngavik Federation of Nunavut (now Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated), the Government of Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories. It led in 1999 to the creation of Nunavut, via the amendment of the Nunavut Act, 1993.

This is the largest Aboriginal land claim settlement in Canadian history, covering a vast territory of 1 877 787 km2 across Northern Canada and the Arctic Archipelago. The Nunavut Land Claim Agreement addresses a comprehensive range of political and environmental rights concerning issues such as land, water and environmental management regimes, conservation areas, wildlife management and others.

Aboriginal title: between proof and extinguishment

Indigenous title needs to be proven and declared by courts or recognised by the government in order to acquire its full expression in law. Treaty negotiations, which include the historic process of creating reserves and the modern process under the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy, are a means to recognise Indigenous title to land. Treaties grant land to Indigenous groups based on pre-existing title to land, originated from their customary law and given the pre-colonial history of use and occupation. However, many treaties covered a parcel of land which was smaller than the one originally claimed by the group as their traditional territory. By accepting this treaty land, the Indigenous group would have to relinquish the right to claim traditional land in the future: this is the extinguishment of Indigenous title.

Many treaty negotiations in Canada have not been yet concluded because the First Nations involved are not willing to accept extinguishment. Canada’s first modern treaty, signed with the Cree and Inuit of Northern Québec in 1975, contained this provision. One of the leading negotiators of this process, Dr. Ted Moses, has affirmed that the extinguishment of Indigenous titled contained in the Treaty was highly contentious and problematic, but was ultimately accepted in order to obtain a settlement, develop their lands and consolidate an autonomous governance regime. To other Indigenous leaders – for instance the negotiators of the Petapan Treaty in the Lac Saint Jean region of Québec – relinquishing the right to claim back the whole extension of their traditional territory would undermine the foundations of Indigenous identity and sovereignty and would thus be unacceptable. Indeed, the agreement-in-principle of the Petapan negotiation states that the treaty shall not exhaustively enumerate or replace Indigenous rights, including Indigenous title, of the First Nations eventually provided with treaty rights.

Some agreements mitigate extinguishment by creating categories of land with different levels of rights and interests: a fraction of the traditional territory is granted full ownership rights, whereas other portions are held as fee simple. For example, the Umbrella Final Agreement signed with the Self-Governing Yukon First Nations (1993) encompasses three categories of settlement land. In lands of Category A, each Yukon First Nation has surface and sub-surface rights to land and keeps Aboriginal rights, titles and interests in these lands. In Category B designation, the Yukon First Nations own the surface rights but not the sub-surface rights, and still maintain Aboriginal rights, title and interests in these lands. The third category is fee simple ownership, whereby they have complete ownership of the land’s surface but do not have Aboriginal rights, titles and interests.12 The government has a duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous interests wherever Indigenous title remains unproven but is reasonably presumed to exist. Canadian courts have repeatedly weighed in on whether these duties have been adequately met (Wilson-Raybould, 2014, p. 500[13]). The federal, the provincial and territorial governments and third parties must meet this standard of consultation, which applies to the reserves and the traditional territories.

Recognition of Aboriginal title in different treaties and government policies is not a settled issue. In the specific claims process, there is opportunity to correct previous land allocations that may be perceived as unjust or whose implementation may have been incomplete. Many Indigenous groups are undertaking treaty negotiations for the first time. For others, while reserves do not fully represent their territory, a treaty that grants rights to land but imposes the extinguishment of the remaining Indigenous title would not be acceptable. In September 2019, a new policy for treaty negotiation was endorsed in British Columbia, recognising the legal and constitutional nature of indigenous title and rejecting extinguishment (Box 3.4). In all, the Government of Canada and Indigenous groups face a difficult, politically charged task when allocating land rights and defining their boundaries.

Deriving wealth from land: opportunities for community economic development

Indigenous peoples must be at a position to derive wealth from their land and natural resources should they so choose, as public and private actors everywhere do. Across OECD countries, land and buildings constitute by far the most important share of wealth, making up 86% of total capital stock (roughly evenly split between land and property), with a corresponding value of USD 249 trillion (OECD, 2017[14]). For Indigenous peoples, the value of land may be more difficult to assess, because of the challenges of measuring the social and cultural aspects of land. Even then, this demonstrates the importance of land as a basis for community development and cultural reproduction. When Indigenous peoples can manage land, it means they can use, protect and develop it according to their own objectives: such is the definition of governance. In short, governance of land use holds the promise of Indigenous-led socioeconomic development.

Opportunities for community development vary according to the land base and the defined land rights regime, as well as by location, proximity to service centres, population size, resource endowment and institutional capacity. A small land base implies lower levels of wealth and restricted ability to host firms, infrastructure projects and housing. Larger places are able to host more firms, which leads to a greater variety of business types and potential for competition among forms in the same type of business, both for sales and workers. However, as discussed above, Indigenous lands in Canada tend to be small and fragmented. Reserve lands located in or close to cities have higher value and in such cases, even small reserves may be able to leverage these assets for community economic development.

The land rights regime determines different levels of competencies for land management and project development. These in turn translate into different degrees of autonomy and institutional capacity. For instance, in reserves under the Indian Act, the government is responsible for land management, but if the band council opts for First Nations Land Management (under the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management and the First Nations Land Management Act), there is a significant increase in the level of responsibilities and competences. Indigenous groups who signed modern treaties granting them full ownership rights over land also hold full responsibility for land use governance, as is the case with Nunavut, for instance.

Opportunities for community economic development and Indigenous entrepreneurship more broadly are linked to a community’s size and accessibility. Remote communities have smaller labour markets. While reserves tend to have small populations, many members of Indigenous nations live off-reserves for jobs, educational opportunities or better housing offer. The relationships between these groups can be a real asset. Strong relations between community members living on and off reserve can help to broaden business opportunities, link to larger markets and may also boost on reserve incomes through remittances. These relationships differ across First Nations and may be reinforced in cases where off reserve members maintain voting rights for band leadership.

Location is an important factor. Small communities in close proximity to larger places or with a specific and highly valuable resource endowment have considerably greater opportunities than do small isolated communities. Those closer to cities have access to a larger market and tend to have more services-oriented businesses. In contrast, small isolated communities have more limited economic development options; for such places, natural resources endowments are key, for example, fish stocks, minerals or a high value tourist amenity. Resource extraction and its subsequent export provides employment and income both for local people and for other workers who migrate to the community. Larger communities are less reliant on their natural resource endowments, since their economies are driven by manufacturing, trade and the provision of services, both to the local population and through exports. The OECD has developed a typology for Indigenous economic development in rural areas (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Typology for Indigenous economic development in rural areas

The OECD’s work on regional development policy has long emphasised a geographical lens on economic development. The more people inhabit a place, the more its character will be defined by second-nature geography – by human beings and their activities. Where settlement is sparse, first-nature geography inevitably dominates – less human settlement and activity necessarily implies a larger role for natural factors, such as the climate or landforms, in shaping economic opportunities. The following typology of economic development in rural areas outlines for ideal types:

1. Remote Indigenous communities with abundant natural resources and amenities – these places are longer than a 60 minute drive from a population centre of 50 000 people or more, and have opportunities for commercial development related to minerals, hydrocarbons, renewable energy, fishing and aquaculture, food production, and nature based tourism. A key issue for these communities will be how to invest own-source revenues in ways that support economic value adding and diversification, and building/attracting the necessary skills to support business growth, while promoting the sustainable management of resources for future generations.

2. Remote Indigenous communities where natural resources and amenities are limited or absent – these places lack natural resources available for commercial use, and economic development is limited to the internal market and some tourist opportunities (e.g. handicrafts). In these places government transfers, subsistence hunting and fishing, and local bartering and sharing through partnerships or service agreements with neighbouring communities and/or other Indigenous groups will play a greater role in supporting community well-being. A key issue for these communities will be ensuring access to public services that offer a sufficient quality of life to retain younger people.

3. Indigenous communities close to cities abundant natural resources and amenities – these places are within a 60-minute drive of a population centre of 50 000 people or more with sufficient land and resources available to develop commercial opportunities related to renewable energy, food production, and tourism. A key issue for these communities will be integrating with the wider urban/regional economy and governance arrangements to maximise the benefit of their resource base.

4. Indigenous communities close to cities where natural resources and amenities are limited or absent – these places are close to cities but do not have sufficient land size or the natural resources that enable commercial scale development opportunities. However, even land parcels are small, this may still present opportunities for retail and industrial land development, and collaboration with local municipalities on planning and infrastructure is important to activating these opportunities.

Source: OECD (2019[15]), Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/3203c082-en.

Indigenous communities have different starting points to derive wealth from land depending on their location and resource endowment. These factors are not controlled by them; that is, it something they either have or not. Yet, sound land and water management and land use planning can strengthen the initial position of Indigenous communities. Furthermore, adequate consultation and negotiation instruments in the context of sub-surface resources exploitation can put Indigenous peoples in a position to derive benefits and to influence the direction of development.

Evolving treaty rights and expanding reserve land

A sufficient base of usable land is a necessary condition for economic opportunities in Indigenous communities (AANDC, 2013[8]). A poor land base, either because of small size, lack of utility, remoteness, due to underservicing in terms of infrastructure or environmental degradation caused by flooding or nearby development means fewer assets to leverage in development efforts. Historically, Indigenous peoples’ land has been diminished in Canada due to dispossession and alienation. However, in the past 50 years there have been growing efforts to (if partially) recover and strengthen this land base.

The most secure and effective way to augment the Indigenous land base is through tenure recognition. Formal title is associated with greater preservation of the cultural and linguistic diversity of Indigenous peoples (Oxfam/International Land Coalition/Rights and Resources Initiative, 2016[16]). Tenure security is positively associated with improved economic outcomes (Aragón, 2015[17]). Canadian research demonstrates that formal property rights in the form of modern treaties reduce transaction costs, increase resource extraction on Indigenous lands and are associated with higher local income (Aragón, 2015[17]). The results are driven by an increase in wages and employment income, as opposed to other changes associated with treaties such as financial compensation or expansion of the public sector.13

Better property rights regimes may facilitate contracts but are not a sufficient condition for development. They still require the existence of economic opportunities. The starting conditions in reserves may not be conducive to development, for instance, when reserves are located in remote rural areas, with few business opportunities and low levels of human capital. Besides markets, supportive institutions are needed to amplify the gains from formalisation, including Indigenous practices and community governance structures (Baxter and Trebilcock, 2009[18]).

Indigenous groups can obtain land through different mechanisms:

1. Modern Treaty;

2. Purchase in the free market or with preference from the State; or,

3. Via state-sponsored policies of facilitated acquisition (2016 Additions to Reserve / Reserve Creation Policy Directive).

This section investigates how these mechanisms work in Canada, bringing the experience of other countries and offering suggestions for reform. A mechanism will be more or less pertinent depending on the land rights regime adopted by the Indigenous group and on provincial regulations applicable in the area.

Modern treaty-making

Treaties are a particular type of agreement that must contain:

Recognition of the Indigenous group as a 'distinct political community', rather than a minority group within the existing state.

Negotiation of the terms of the agreement that are fair and undertaken in good faith.

Inclusion of responsibilities and obligations for the parties, to bind them in an ongoing relationship (Petrie, 2018[19]).

Treaties often recognise land rights, although it is not mandatory that they do so. It is an important element because a group’s territory is closely linked with their collective identity and holds potential for development opportunities. As discussed earlier in the Chapter, historic treaties have made First Nations bands the collective proprietor of reserve lands, whereas some modern treaties create categories of lands with different types of rights and interests. A few modern treaties confer right to land without extinguishment of Aboriginal title. Treaties are thus a fundamental mechanism of recognition of formal title to land.

Treaty negotiations are both a historical and an ongoing process. Between 1701 and 1923, the Government of Canada signed agreements with Indigenous communities. These are called historic treaties. Nevertheless, when the State has not fulfilled obligations or satisfactorily implemented treaties, Indigenous groups may pursue judicial claims or negotiate specific land claims. Furthermore, many Indigenous groups are still undertaking treaty negotiations for the first time, which demonstrates how much this issue lies unresolved. These are called modern treaties and have been signed since 1973. They may include comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements. Lastly, it is worth noting that some Indigenous groups prefer not to engage in negotiation processes because doing so would demand an extinguishment of Aboriginal title.

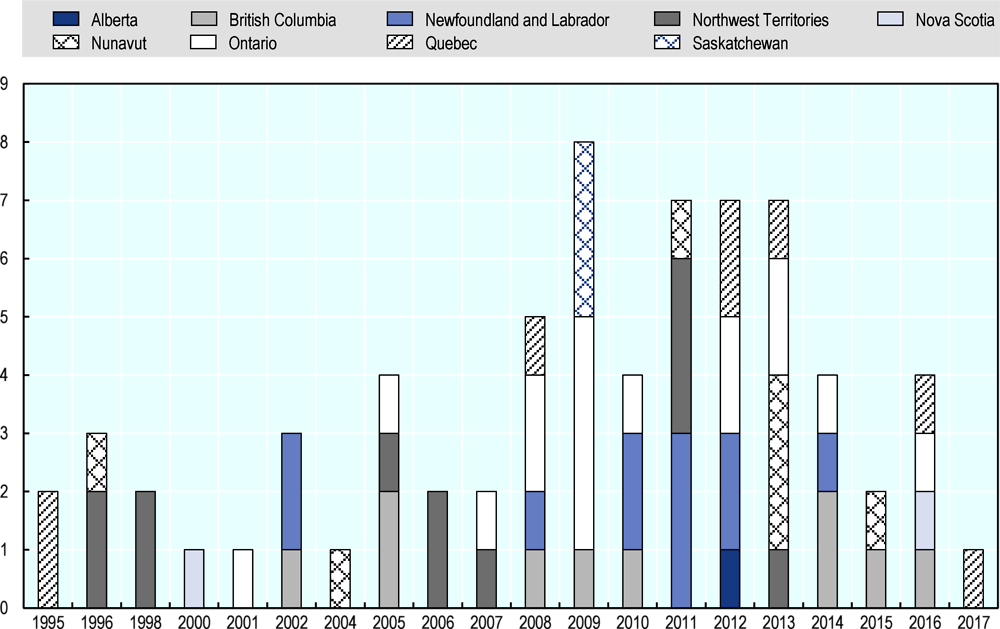

Comprehensive Land Claims Policy—the modern treaty process

The Government of Canada adopted the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy in 1973 and updated it in 1986. It allows Indigenous groups, the Government of Canada and the appropriate Territory or Province to negotiate agreements, also called modern treaties. An agreement can refer to: transfers of land ownership; land, water, heritage, environment and wildlife management; financial compensation; a self-government agreement (since 1995); an economic development strategy; and sharing of resource revenue. Since 1973, 26 comprehensive land claims have been signed and are in effect, whereas at least other 56 are being negotiated as of November of 2018. Examples of treaties under negotiation are: Innu Nation Claim (Newfoundland and Labrador); Atikamekw Nation Council Comprehensive Land and Self-Government Claims (Quebec); Algonquins of Ontario (Ontario); and Inuit Transboundary Negotiations in Northern Manitoba (Manitoba).

The Inherent Right Policy of 1995 solidified the recognition of Indigenous peoples’ right to self-government. According to this policy, Indigenous peoples of Canada “have the right to govern themselves in relation to matters that are internal to their communities, integral to their unique cultures, identities, traditions, languages and institutions, and with respect to their special relationship to their land and their resources.” (FMB, 2018[20]). Self-government provisions can compose modern treaties or constitute a stand-alone agreement, accompanied by sectoral dispositions on health, education or other policy sector.

All land claims and comprehensive land claim agreements are constitutionally protected under Section 35. They cannot be amended or abrogated without the consent of all signatories. Sectoral agreements and stand-alone self-government agreements are not constitutionally protected, except the Délįnę Final Self-Government Agreement, which builds upon the Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement of 1994. Currently there are about 50 self-government negotiation tables across the country, at various stages of the process. Many of those are being addressed in conjunction with modern treaties.14

Canada has concluded 32 modern agreements with aggregations of Inuit, Métis and First Nations, between comprehensive, stand-alone and sectoral self-government agreements (FMB, 2018[20]) (Table 3.2). Since 2015 federal officials have been engaging in conversations with Indigenous groups, both within treaty negotiation processes and those outside treaty negotiations to address their rights, interests, and needs. These conversations, termed “Recognition of Indigenous Rights and Self-Determination discussions”, seek to better respond to the needs and priorities identified by communities and focus on closing socio-economic gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians and advancing greater self-determination. Since 2015, Canada has signed 64 preliminary type agreements with Indigenous groups and are currently negotiating at 87 RIRSD tables.

Table 3.2. Modern agreements concluded (2018)

|

Type of agreement |

Agreement |

|---|---|

|

Land claims and comprehensive claims agreements |

James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1977) Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement Quebec (2008) Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (2005) Tlicho Agreement (Northwest Territories) (2005) Nisga’a Final Agreement (British Columbia) (2000) Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement (British Columbia) (2009) Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement (British Columbia) (2011) Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Agreement (Quebec) (2012) Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (1994) Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993) Tla’amin Final Agreement (2014) Northeastern Quebebec Agreement (2008) Inuvialuit Final Agreement/ Western Arctic Claim (1984) The Carcross/Tagish First Nation Final Agreement (2005) Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Final Agreement (1993) Kluane First Nation – Final Agreement (2003) Kwanlin Dun First Nation Final Agreement (2005) Little Salmon / Carmacks First Nation Final Agreement (1997) Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation Final Agreement (1993) Selkirk First Nation Final Agreement (1997) Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (1992) The Ta'an Kwach'an Council Final Agreement (2002) Teslin Tlingit Council Final Agreement (1993) Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Final Agreement (1998) Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Final Agreement (1993) |

|

Stand-alone self-government agreements |

Westbank First Nations Self-Government Agreement (British Columbia) (2005) Deline Final Self-Government Agreement (2016) Cree Nation Governance Agreement (1978) Sioux-Valley Dakota Nation Self-Government Agreement (2014) Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Act (1986) |

|

Sectoral self-government agreements |

Mi’kmaq Education Agreement (Nova Scotia) (1997) Anishinabek Nation Education Agreement (Ontario) (2017) |

Sources: AANDC (2010[21]), The Government of Canada’s Approach to Implementation of the Inherent Right and the Negotiation of Aboriginal Self‑Government, https://www.aadnc‑aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100031843/1100100031844 (accessed on 12 December 2018). ; FMB (2018[20]), First Nations Governance Project - Phase 1, https://fnfmb.com/sites/default/files/2018-09/2018_FN-Governance_Project_phase1-low-res_update.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2018).

The Government of Canada and some provinces have attempted reforms to streamline treaty negotiations. While the treaty-making process is cumbersome and slow, it remains fundamental to advancing the reconciliation agenda. In British Columbia there has been a history of advancements that recently culminated in the principle of “no extinguishment” in treaty negotiations (Box 3.4). This built on previous efforts in British Columbia such as the Common Table Report (2008[22]) and the Lornie Report (2011[23]).

A 2018 report of the Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs of Canada’s House of Commons argued that, in its current form, the government’s policies and processes serve to prevent Indigenous communities from achieving a fair resolution of their claims (Mihychuk, 2018[24]). Thus, despite the aforementioned efforts in British Columbia and elsewhere, revisions to strengthen the treaty negotiation process have been slow going and much remains to be done.15

As of the end of 2018, the government of Canada is undertaking discussions with Indigenous communities and organisations on the creation of a new “rights recognition” legislative framework that would give effect to UNDRIP articles related to self-determination, self-government and models of governance (FMB, 2018[20]). This may provide further impetus for long-needed reforms. In support of these efforts, the Government of Canada should consider:

Ending the practice of requiring that Indigenous rights holders extinguish their inherent and/or treaty rights as a prerequisite for an agreement.16

Supporting Indigenous groups with the capacity to effectively undertake negotiations.

Develop an independent and ongoing monitoring mechanisms in order to ensure that the commitments made by the Government of Canada in comprehensive land claim agreements are met in a timely and effective manner.

Ensure that those negotiating land claims agreements from the government’s side have high-level decision-making authority (e.g., Ministerial authority).

Continue adopting mediation and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, where appropriate.17

Fulfilment and implementation of historic treaties

First Nations may seek the fulfilment and implementation of historic treaties. For instance, a historic treaty may have promised a certain amount of land to a First Nation, but the Nation received less of it. In such instances, First Nations can make a claim to the government to receive the land that was promised or to obtain appropriate compensation, if it is not possible to get the land back. Another example relates to when the government handles money on behalf of the First Nation, but the Nation deems irregularities in the process. In such instances, the First Nation can again make a claim to assess the extent of the irregularity and potentially receive compensation for it. This section discusses the fulfilment and implementation of historic treaties through two policies adopted by the government: Specific Claims and Treaty Land Entitlement (TLE).

Box 3.4. Engagement for improved treaty negotiations in British Columbia

With the exception of the Douglas treaties and the extension of Treaty 8 in the northeast of the province, no pre-1975 treaties were signed in British Columbia. In 1990, the British Columbia Claims Task Force was created to recommend how Canada, British Columbia, and First Nations in British Columbia could negotiate treaties. The Task Force completed its report in 1991, and Canada, British Columbia, and the First Nations Summit accepted all of its 19 recommendations. These included the establishment of the British Columbia Treaty Commission and the creation of the made-in-British Columbia treaty negotiations process.

Since then, Canada, the First Nations Summit and the Province of British Columbia – the Principals – have been working collaboratively to strengthen and improve treaty negotiations, advance reconciliation and make progress on concluding agreements in the province.

In 2015, the Principals– agreed to establish a multilateral engagement process to improve and expedite treaty negotiations in British Columbia. The Principals acknowledged the need to employ greater flexibility to reach treaties by supporting constitutionally protected core agreements with side agreements, sectorial treaties and condensed Agreements-in-Principle. It also recognised that the funding process should be more transparent, with greater accountability. Dedicated funding and best practices guidance are needed to address territorial overlaps among First Nations.

In 2019, the Principals of the BC treaty negotiations process endorsed an important new policy, the Recognition and Reconciliation of Rights Policy for Treaty Negotiations in British Columbia. Co-developed by Canada, British Columbia, and the First Nations Summit, the policy makes it clear that negotiations will be based on the recognition of the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples. The new policy is unequivocal in rejecting extinguishment of existing Aboriginal rights and title, and directs that treaties not require full and final settlement and are capable of evolution. This brings the federal and provincial policies in-line with the original spirit and intent of the treaty negotiations process. The policy also acknowledges that negotiations must be based in good faith, the honour of the Crown, and will respect the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Sources: AANDC (2016[25]), Multilateral Engagement Process to Improve and Expedite Treaty Negotiations in British Columbia Proposals for the Principals’ Consideration, http://www.cio.gov.bc.ca/cio/intellectualproperty/index.page (accessed on 30 November 2018); Global Newswire (2019[26]), “Canada, British Columbia, and First Nations Summit endorse new negotiating policy: Indigenous rights recognition and no extinguishment”, https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2019/09/06/1912375/0/en/Canada-British-Columbia-and-First-Nations-Summit-endorse-new-negotiating-policy-Indigenous-rights-recognition-and-no-extinguishment.html; Government of Canada (2019[27]), The Recognition and Reconciliation of Rights Policy for Treaty Negotiations in British Columbia, https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2019/09/the-recognition-and-reconciliation-of-rights-policy-for-treaty-negotiations-in-british-columbia.html.

Specific Claims Policy—a mechanism to settle disputes related to land and other claims

Specific claims deal with past wrongs against First Nations, in relation to historic treaties. They are a voluntary process to settle disputes through negotiation, outside the judicial system.18 The principles and process are established in the Specific Claims Policy, which was created in 1982 and significantly amended in 1990 and 2007. The goal of this process is to discharge the Federal Governments lawful obligations related to the administration of land and other First Nation assets and to the fulfilment of Indian treaties, though the treaties themselves are not open to renegotiation.

Not all specific claims are land-related, but many are. They can enable the administration of land and other assets or the fulfilment of First Nations treaties. For example, a specific claim could concern the insufficient provision of reserve land as promised in a treaty or the improper handling of First Nation money by the federal government in the past.

The Government of Canada has negotiated 464 specific claims as of March 2018. Hundreds are outstanding, including: 249 claims accepted for negotiation, 68 claims that lie before the Specific Claims Tribunal and 160 claims that are under assessment. Specific claims settlements successfully generated opportunities for development in some Indigenous communities (Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Claim settlements and their outcomes: examples from across Canada

Claims negotiations are large undertakings and can take years to be realised. The following examples illustrate how some claims have been settled and their outcomes for community economic development.

The Onion Lake Cree Nation: In 1994, the Onion Lake Cree Nation and the Government of Canada successfully negotiated a Treaty Land Entitlement Specific Claim. Monetary compensation of approximately USD 30 million translated into joint ventures with private energy partners and allowed exploration and development on about 140 000 acres of existing and new treaty land.

Keeseekoowenin First Nation: The reserve land at Clear Lake was taken away by the government in 1935 for the creation of the Riding Mountain National Park, without the consent of the community. The door to a negotiated settlement opened in 1991, when the federal government recognised that the park boundaries should not have included the reserve. By 2005, Canada and the First Nation had reached a settlement on two claims: all 435 hectares of the former reserve land at Clear Lake were returned to the First Nation, and they also received approximately $ 12 million in compensation. The claim settlement paved the way for the First Nation and Parks Canada to begin to rebuild their relationship and to work together.

Abenaki Nation: The Abenaki Nation was established on two reserves, Odanak and Wôlinak, located on the South shore of the St. Lawrence River, and a third reserve, Crespieul, 400km away. In the end of the 19th century, timber was being illegally pillaged from this reserve. The government’s response was to surrender the land for auction. In 1996, under Canada's Specific Claim Policy, the Abenaki Nation filed a request aiming to obtain compensation for the government having authorised the surrender of lands, in what characterised a breach of its fiduciary obligations. In 2007, after 4 years of negotiations, the two parties agreed that the Abenakis would permanently give up their rights to the Crespieul territory, in exchange for a net compensation of 4.5 million dollars. The agreement was ratified after a referendum submitted to community members.

Source: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (2015[28]), Success Stories: Acts, Agreements and Land Claims, https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1306932724555/1539953769195 (accessed on 11 December 2018).

There have been growing calls for the reform for the Specific Claims Policy over the years. The 1990 Oka/Kahnesatake crisis galvanised a need for action and a newly independent Indian Specific Claims Commission (ISCC) was created in 1991 with a renewed focus on mediation and improving processes for First Nations claims (Indian Claims Commission, 2009[29]). The ISCC was replaced in 2009 by a permanent, independent adjudicative body staffed by Superior Court Judges—the Specific Claims Tribunal. The new Tribunal was established by the Specific Claims Action Plan which included the creation of a dedicated fund of $250 million per year for ten years for the resolution of specific claims.

There have been ongoing discussions on how to strengthen and improve the Specific Claims Policy in recent years (AANDC, 2013[30]) (Mihychuk, 2018[24]). While recognising the many improvements that have been made, further actions to strengthen the Specific Claims Policy are needed. These include:

Expanding the eligibility criteria to include claims based on the non-fulfilment of treaty rights.

Enhancing the system of monitoring and reporting on claims at all stages of the claims process.

Facilitating research and knowledge sharing among First Nations in order to help them assess the basis and the value of their specific claims.

Developing an independent office and reporting framework to monitor how commitments made by the Government of Canada in specific claim agreements are being implemented.

Box 3.6. Violent clashes and Indigenous land rights: The 1990 ‘Oka crisis,’ Quebec

Having been successively disposed of their traditional lands over a number of decades by the settler community, a group of Mohawk First Nations took a stand in 1990 against a court ruling that permitted the expansion of a golf course over their lands in Oka, Quebec. This protest and blockade of the area ended in a violent confrontation between a group of Mohawk and local activists and Canadian military and Quebec police forces. One Mohawk elder and one Quebec policy officer were killed and many were injured. It was a definitive low point in Indigenous-settler relations and it highlighted the failure of Canada’s legal system to adequately address Indigenous rights and concerns. The Oka Crisis played an important role in the establishment of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

The protest ended through negotiations between the Mohawk protestors and the Quebec provincial government and Canadian federal government. The Canadian Federal government ended up purchasing the land and cancelling the planned expansion. Additional plots of land were purchased by the Canadian government in 2001 (Government of Canada, 2019[31]). This land is set aside for the use and benefit of the Mohawks of Kanesatake as lands reserved for the Indians within the meaning of paragraph 24 of section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867 but not as a reserve within the meaning of the Indian Act (Government of Canada, 2019[31]).

Sources: Government of Canada (2019[31]), Kanesatake Interim Land Base Governance Act, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/K-0.5/index.html (accessed on 25 March 2019); Canada History (2019[32]), Oka, http://www.canadahistory.com/sections/eras/pcs%20in%20power/Oka.html (accessed on 25 March 2019); York, G. and L. Pindera (1991[33]), People of the Pines: The Warriors and the Legacy of Oka, https://books.google.fr/books/about/People_of_the_Pines.html?id=7M51AAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 4 September 2018).

Treaty Land Entitlement (TLE)—rectifying historical dispossession

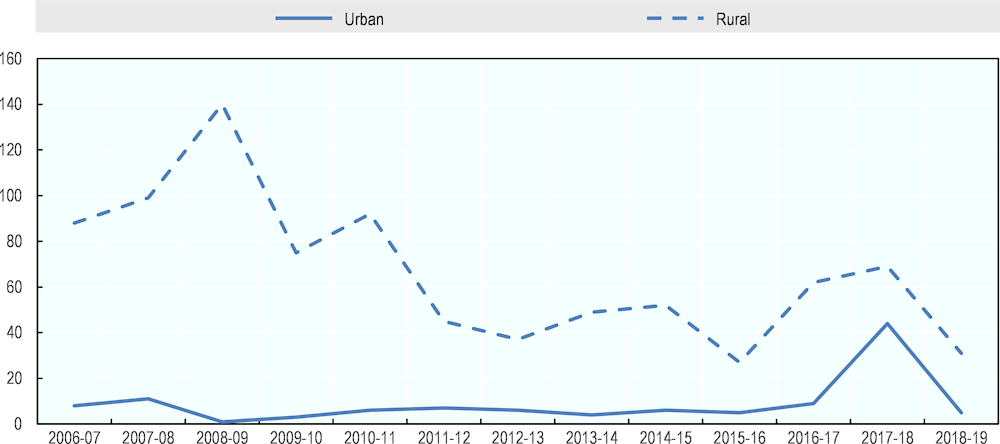

A First Nation may file a Treaty Land Entitlement Claim with the Government of Canada when they did not receive all the land specified in their historic treaty. The Government of Canada negotiates with the First Nation, typically with the involvement of the provincial government, to provide the promised amount of reserve land. Once an agreement is reached, the First Nation has two options to pursue land acquisition: buy it in the market from willing sellers, or select from a sample of unoccupied Crown land. Once the land is acquired, the First Nation may submit a proposal of conversion to reserve status, under the Additions to Reserve process. Figure 3.2 summarises this process.

Figure 3.2. The Treaty Land Entitlement Process

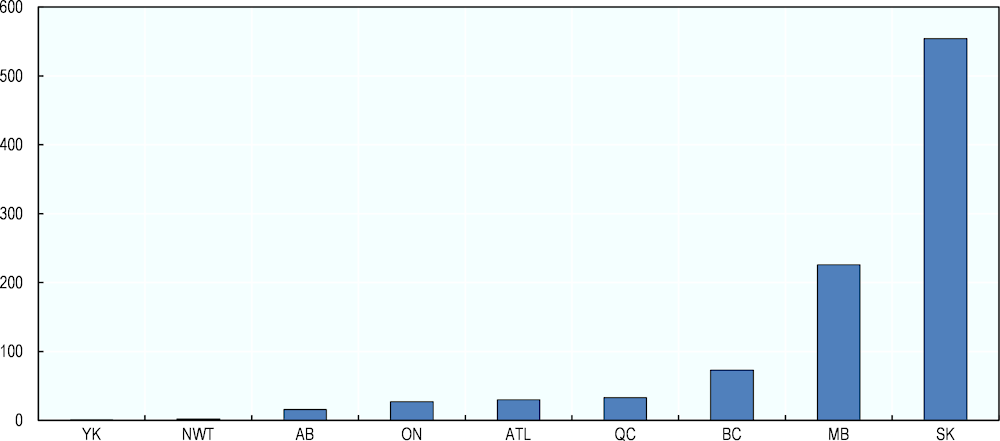

As of 2016, 90% of the agreements had been reached in the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan.19 In 1997, 21 Manitoba First Nations signed a TLE Framework Agreement with the federal and the provincial governments. Since then, other 8 Manitoba First Nations have entered into individual settlements. The Government of Canada committed to pay $190 million for land purchases and processing costs, whereas Manitoba would provide 1.2 million acres of unoccupied Crown land. The balance will be acquired from willing private landowners.

In Saskatchewan, a similar negotiation process took place. In 1992, 25 First Nations in signed a TLE Framework Agreement, under which the provincial and federal governments would provide $440 million over 12 years to buy land, mineral rights and improvements, including buildings and structures affixed to the land. These First Nations may purchase federal, provincial or private land anywhere in Saskatchewan, from willing sellers. As of 2016, 23 out of the original 25 First Nations had acquired the minimum amount of land required to be set apart as reserve.20 No mechanism of selection of unoccupied Crown land has been set up.

The responsibilities of the provincial government differ in each framework agreement. In Manitoba, the province supplies unoccupied Crown land previously selected by the First Nation. In Saskatchewan, the province provides funds for the acquisition of land, and may willingly sell land to the First Nations, if they are willing to buy. In both cases, the province gets to review the selected lands and ensure that provincial interests are addressed prior to achieving reserve status. In the TLE Agreements there is variety of matters that affect provincial interests, such as land and mineral acquisitions, water and roadway matters and the resolution of third- party and utility interests.21

First Nations can and should be strategic about land acquisition. Considering that TLE agreements typically confer a 10- or 20-year period to carry out land purchases, they can benefit from this time lag to make strategic purchases that reflect a unified vision for the future of the Nation. In this sense, some communities have elaborated land acquisition plans, in alignment with their community development plans. Environment Site Assessments are also conducted to determine the environmental condition of the proposed reserve land to ensure there is no contamination. The land would need to be remediated to the applicable environmental standard before reserve creation can be approved.

To illustrate the point of strategic land acquisition, in 2012 the Peguis First Nation in Manitoba created an advisory committee of land selection and acquisition. The committee seeks to acquire lands that can provide sound economic and cultural opportunities and contribute to the long term of well-being of community members. They have elaborated a strategic framework, observing the provisions set out in the community comprehensive plan, according to which land selection must never be separated from the process and outcomes of community development.22

Beyond addressing historical injustices, the process of Treaty Land Entitlement provides an opportunity for First Nations to pursue community development. As already discussed, land acquisition can function as the basis for housing, energy, infrastructure and other economic development projects which may have long-lasting positive outcomes for the community.

The example of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan is illustrative. They filed one of the earliest TLE claims, being awarded 48 640 acres of land in 1983. Among others, the Nation selected 35 acres of unoccupied Crown land in a suburb of Saskatoon, which then became the first urban reserve in Canada specifically created to house a First Nations economic development project. The Band formed an economic development corporation, called Aspen Developments, to pursue collective development on the selected land and to provide funding to community members for business endeavours. A commercial centre was created and today it hosts 40 businesses, among retail outlets, medical, insurance and legal offices, employing over 300 people. The Nation charges property and sales tax akin to what would have been paid on non-reserve property. This demonstrates how the recognition of land rights has catapulted Band-led, community-oriented development in an urban area.

Successive reports by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada have recommended improvements to the Treaty Land Entitlements process (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2009[34]) (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2005[35]). While the Government of Canada has attempted reforms to mechanisms such as Additions to Reserve Process, the TLE remains to be tackled. To this end, the Government of Canada should:

Develop and implement a plan clarifying the explicit steps to process outstanding selections and to meet commitments to reduce the processing time for treaty land entitlement selections from initial Band Council Resolution to conversion to reserve status.

Track the overall time it takes to convert lands to reserve status and demonstrate progress periodically—report publicly and include in departmental performance indicators.

Organise the land selection files with the documentation necessary to facilitate conversion to reserve status.

Work closely with First Nations to assist them in their efforts to resolve third-party interests.

Continue working with First Nations through regular work planning sessions to develop an action plan for selections, which include setting up timelines and a strategy for conversions to reserve status, as well as providing ongoing support for them to meet their obligations.

Land Acquisition

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) recommends a large scale reallocation of lands by rational criteria, that would result in a significant expansion of lands “wholly owned and controlled” by First Nations, as well as a “share in the jurisdiction and benefit from a further portion of their traditional lands” (Taiaiake Alfred, 2009[36]). Land acquisition is an instrument to expand the land base, which, as discussed above, is important to overcome the limited land base of Indigenous peoples in Canada since European arrival. Outside of modern treaty-making, expansion of the land base can be undertaken through purchases in the free market, additions to reserve, facilitated acquisition via state-sponsored purchases, or priority in the purchase of state-owned lands.