Following a brief introduction to Lithuania’s economic and demographic context, this chapter assesses the health status of the population. The chapter also presents the main features of Lithuania’s health system and its governance. The health status of the population in Lithuania remains relatively poor by the OECD standards. The prevalence of unhealthy behaviours, such as alcohol drinking, is particularly high and a considerable share of premature death could be avoided. Spending on health is low, but the health system is overall well poised to tackle these challenges more effectively. The National Health Insurance Fund provides quasi-universal coverage to the population and contracts public and private providers. Most institutional elements of well-performing systems are in place and there is a remarkable consensus of stakeholders behind priorities which are aligned with the burden of disease and reforms which are conducive to tackling them. Strengthening data-driven performance assessment and decision making is key to improving policy impact.

OECD Reviews of Health Systems: Lithuania 2018

Chapter 1. Overview of Lithuania’s health care needs and health care system

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

This chapter presents the socio-economic and demographic context of Lithuania and describes the health status of the population. It presents the main features of the health system and outlines its governance framework.

Lithuania has a dynamic economy and aging population (1.1) in a relatively poor health (1.2). Health spending is low by OECD standards but the overall spending structure has been converging with OECD averages (1.3). The health system has been profoundly transformed since the restoration of independence in 1990 (1.4) and improving health is a consistently stated priority (1.5).

1.1. Lithuania has a dynamic economy and an aging population

1.1.1. The economy is very dynamic but growth has not been inclusive enough

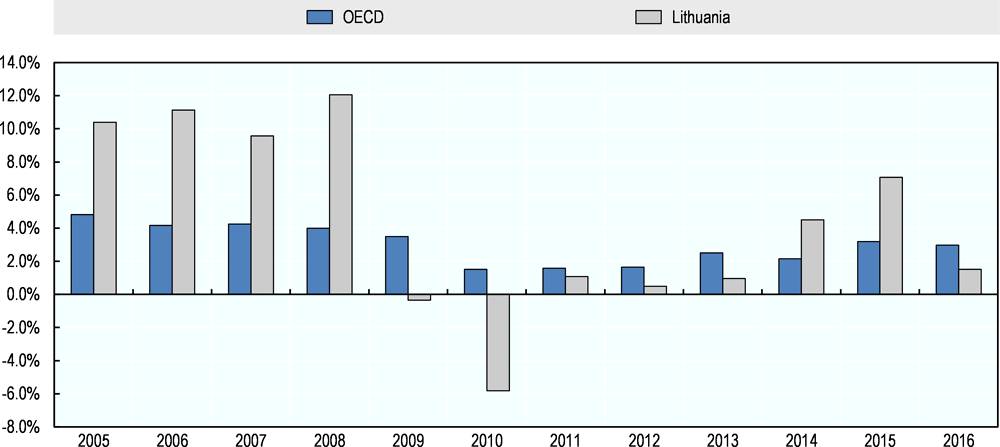

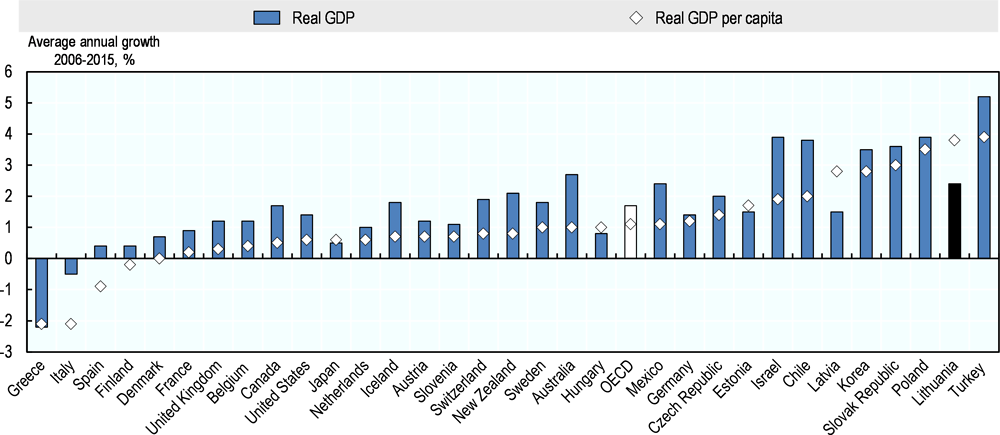

Lithuania, with 2.9 million inhabitants, is a small but dynamic and open economy, member of the European Union (EU) since 2004 and the Euro Zone since 2015. After the collapse of the central planning system in 1991, Lithuania experienced a difficult but fast transition to market economy. In 1991 and 1992, the country’s real annual GDP growth dropped by 6% and 21%, respectively. Yet, Lithuania subsequently became one of the fastest growing economies compared to the OECD (Figure 1.1), and the gap in GDP per capita to the OECD average shrank from 70% in 1993 to around 30% in 2014. Economic growth was accompanied by a rise in living standards reflecting better job opportunities and education, in particular.

Nevertheless, the economy has been vulnerable to external shocks. The Russian financial crisis in 1997-98 was the catalyst for a temporary slowdown and the impact of the global financial crisis of 2008 was severe, with a nearly 15% drop in GDP and unemployment surging up to 18% in 2009. Between 2011 and 2014 economic growth has been again one of the highest among European as well as OECD countries, reflecting a swift recovery from the global financial crisis thanks to the economy’s high flexibility (OECD, 2016a). GDP growth slowed in 2015 (to 1.8%) as exports were affected by the recession in Russia and counter-sanctions but it picked up to 2.1% in 2016, and is expected to strengthen in 2017-18 (OECD2016b).

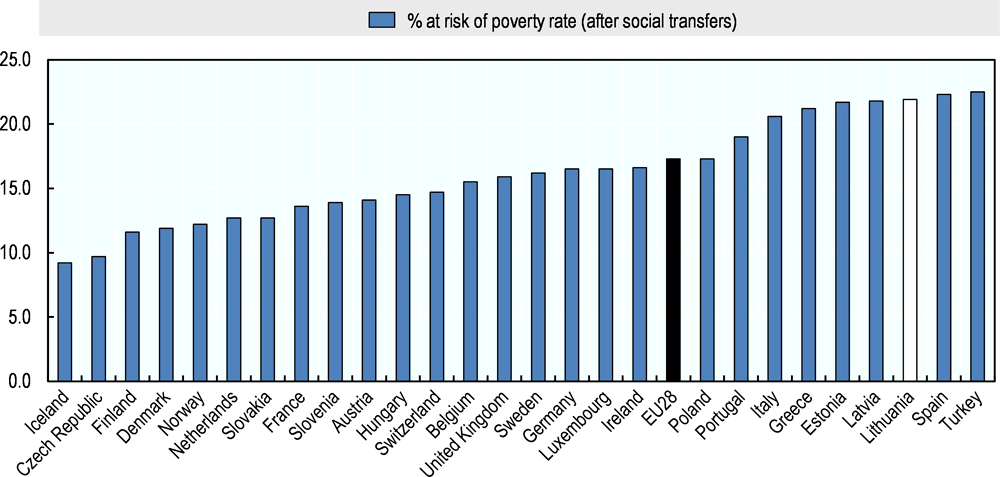

Despite the impressive progress, Lithuania still faces serious challenges such as high income inequality, and a large share of population at risk of poverty. The Gini index – a coefficient that measures income inequality in a society and ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 100 (maximum inequality) – stood at 37.3 in 2014, well above both the OECD and the EU28 average (OECD Income Distribution and Poverty database, 2016). The share of the population at risk of poverty is the third highest compared to the European member countries of the OECD (Figure 1.2). The poverty is also deep-rooted as the income of the poor is on average 23% below the poverty line.

Figure 1.1. Lithuania has one of the fastest growing economies in the OECD

Note: In Lithuania and other Baltic countries GDP per capita grew faster than GDP because of population decline.

Source: OECD (2017a), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2017 Issue 1, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2017-1-en.

Figure 1.2. More than 20% of the population is at risk of poverty

Note: Cut-off point: 60% of median equivalised income after.

Source: Eurostat Population and Social Conditions database, 2017.

Moreover, the unemployment rate of 7.9% (2016) remains above the OECD average of 6.5% (2015), with a nearly 45% share of long-term unemployment. Lithuania’s labour market was heavily affected by the global financial crisis, but recovered quickly - the unemployment rate has fallen by two percentage points a year on average since 2010. The unemployment rate for youth, which peaked at 35.7% in 2010, fell to 19.3% in 2014 thanks to specific support measures including training, wage subsidies and a “youth guarantee” which ensures that all youth under 29 get a good-quality offer for a job, training or continued education within four months of leaving education or entering unemployment (OECD, 2015b). However, the unemployment among the low-skilled, which account for majority of the poor, is nearly three times higher than among the general population (OECD, 2016a).

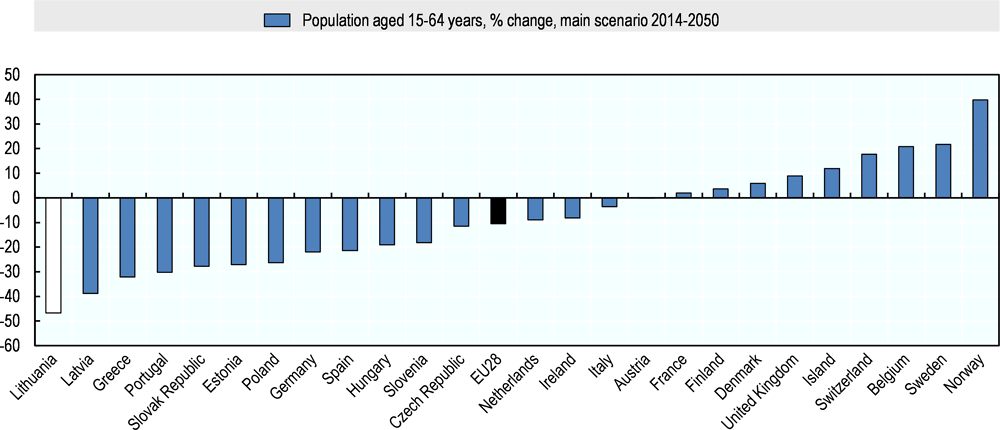

1.1.2. The population is fast aging, a process largely driven by emigration

Lithuania is one of the fastest-ageing countries in the EU. Indeed, the old-age dependency ratio is expected to rise from one senior (person above 65 years old) for every 2.4 workers in 2014 to 1 senior for 1.2 workers in 2050 (European Commission, 2015). Put differently, the working-age population is projected to shrink by nearly a half between 2014 and 2050 (Figure 1.3). Lithuania has a modest fertility rate – 1.6 births per women, which is, nevertheless at par with the average for the OECD countries and slightly higher than in the neighbouring countries.

Aging is largely emigration-driven. Mortality in Lithuania is relatively high (see below) but the large emigration among adults aged 25-64 years largely explains demographic imbalances. Since 1990, 22% of the population (of 1990) has emigrated. The yearly emigration rate accelerated from 7% of the population in 1990-2000 to above 12% during the 2000s. The average net emigration rate decreased after 2010, but continues to be one of the highest in Europe, with majority of emigrants being female, young, and well educated (Arslan et al., 2014). In fact, population outflows were on the rise again between 2014-2016 (Statistics Lithuania, 2017; OECD, 2017c).

Figure 1.3. Lithuania’s working age population will decline rapidly in the next 35 years

Source: Eurostat Population and Social Conditions Database; Statistics Lithuania.

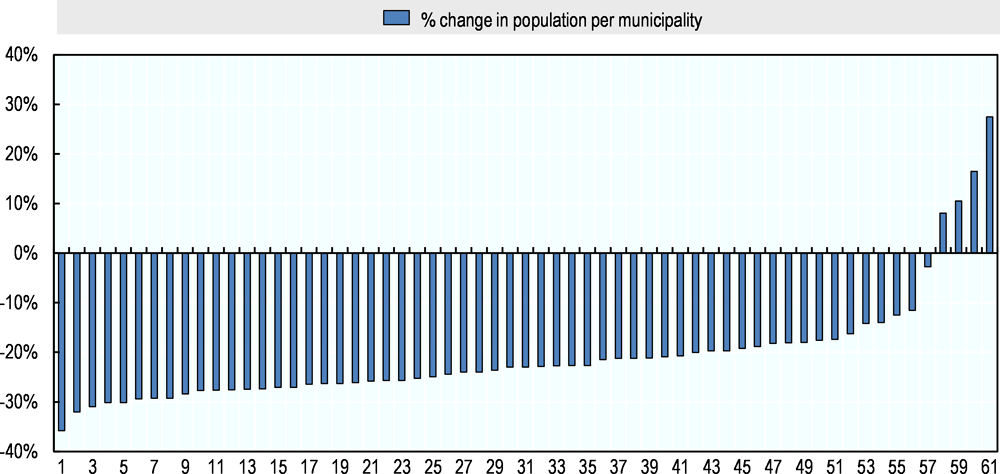

The demographic change has been uneven across the country. In conjunction with these trends, a very rapid urbanisation has taken place. Four municipalities, including the 3 largest cities, have seen their population increase since 2001 (Figure 1.4). The rest have seen decreases, some very dramatic (five rural municipalities have lost more than 30% of their population). Overall these trends will give rise to numerous challenges, for instance, the need to ensure access to health services for aging and possibly scattered segments of the population. The estimates may, however, need to be revised due to the unknown intended duration of the emigration.

Figure 1.4. The population has declined by more than 20% since 2000 in 70% of municipalities

Source: Data provided by Ministry of Health, Lithuania.

1.2. Lithuania’s health results put it among the lowest ranked in the OECD

1.2.1. Life expectancy in Lithuania remains below that of most OECD countries

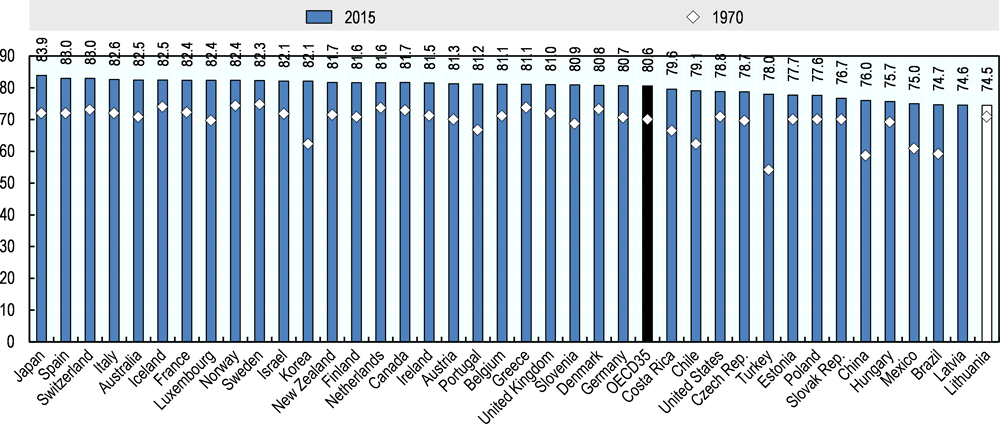

Life expectancy is lower than anywhere in the OECD

Life expectancy at birth is six years below the OECD average. It lags approximately nine years below the life expectancy in the top three OECD countries – Japan, Spain, and Switzerland (Figure 1.5). It is also relatively low when compared to Estonia and most Central European Countries. Furthermore, over the past 45 years, Lithuania's accumulated gain in average life expectancy at birth has been less than four years. This is lower than in the OECD, where on average the life expectancy has increased by 10.5 years between 1970 and 2015. This trend however is typical of many post-Soviet countries which experienced large increases in mortality rates in the period around the break-up of the Soviet Union. Indeed, in Lithuania life expectancy dropped by 4 years between 1986 and 1993 and only started rising again in 1994 as the economic situation of the country improved.

Figure 1.5. In 45 years, life expectancy at birth has increased by four years only and is now lower than anywhere in the OECD

Moreover, Lithuania is marked by a larger gender gap in life expectancy than in any OECD country. On average Lithuanian women live nearly 11 years longer than men, whose life expectancy is 69.2 years, the lowest in the OECD. The gender gap in Lithuania is twice as high as the average in the OECD countries at 5.2 years in 2015 (OECD Health Statistics, 2017).

Chronic conditions and external causes contribute most to the life expectancy gap between Lithuania and OECD countries

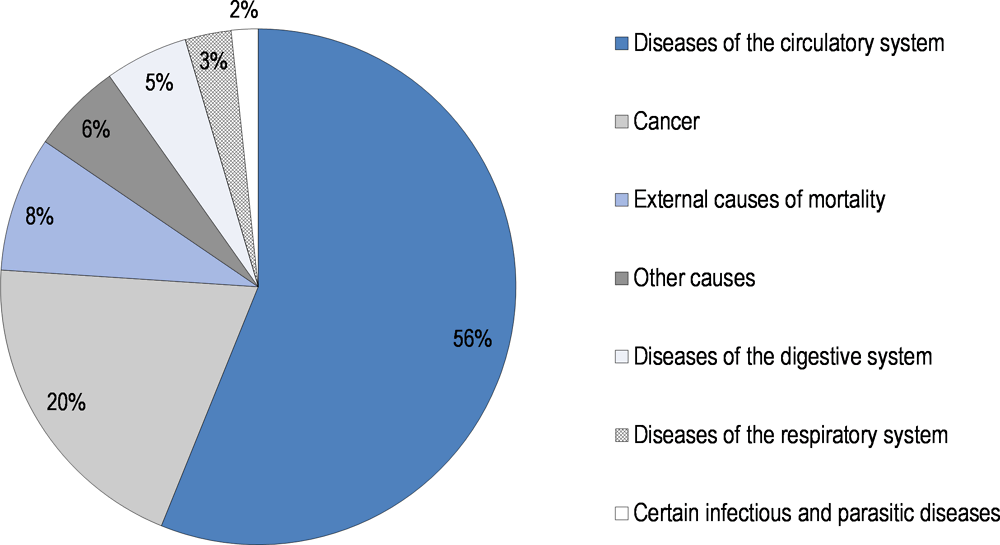

Chronic conditions account for majority of deaths in Lithuania, followed by external causes (accidents and intentional self-harm). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs - including ischemic heart disease, stroke and other diseases of circulatory system) are the leading cause of death in Lithuania, accounting for 56% of deaths (ischemic heart diseases and stroke account for 37% and 14% of all deaths, respectively) (Figure 1.6) The second leading cause of mortality is cancer – 20% of deaths. Accidents and intentional self-harm (suicides) – the external causes of mortality – account for 8% of deaths (suicides account for 2% of deaths). Death rates from external causes, which are much higher among men than women, explain a large part of the gender gap in mortality (OECD Health Statistics, 2017).

Figure 1.6. Cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of death in Lithuania, followed by cancer

Lithuanians die three times more frequently of heart attacks than citizens of the OECD on average, but rates of strokes and suicides are also much higher. CVDs are the main cause of death in OECD countries, but the standardised death rates (SDR) in Lithuania are double those of the OECD (Table 1.1). SDR for ischemic heart diseases are in fact more than three times higher. While deaths from cancer occur only marginally more often than in the OECD – only 8.4% above the OECD average – deaths from external causes, occur twice as often in Lithuania as in the OECD. In fact, the SDR for suicide is the highest in the entire region of Eastern Europe and central Asia. SDR from diseases of digestive system, the fourth leading cause of death in Lithuania, is one and a half times the OECD average, with SDR due to chronic liver disease and cirrhosis nearly double. SDR from infectious and parasitic diseases exceed the OECD average by 46%, with tuberculosis explaining much of the difference. Among the main causes of death, Lithuania only has a lower than OECD average mortality for diseases of the respiratory system.

Table 1.1. Standardised death rates for cardiovascular diseases and external causes are exceedingly high

Differences in standardised death rates – main causes of death – Lithuania and OECD average, (SDR per 100 000 population), 2014.

|

SDR per 100 000 population |

Lithuania |

OECD average |

|---|---|---|

|

All causes |

1148.0 |

815.1 |

|

Diseases of circulatory system: |

644.4 |

301.1 |

|

Ischemic heart diseases |

422.7 |

125.2 |

|

Cerebrovascular disease |

156.7 |

70.3 |

|

Cancer |

228.5 |

211.3 |

|

External causes: |

97.3 |

48.3 |

|

Intentional self-harm |

27.1 |

12.4 |

|

Diseases of digestive system: |

59.8 |

35.4 |

|

Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis |

23.3 |

11.8 |

|

Diseases of respiratory system |

33.3 |

64.1 |

|

Certain infectious and parasitic diseases: |

19.3 |

13.2 |

|

Tuberculosis |

6.5 |

1.3 |

Note: Raw mortality data from the WHO Mortality Database have been age-standardised to the 2010 OECD population, including for Lithuania.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en (extracted from WHO).

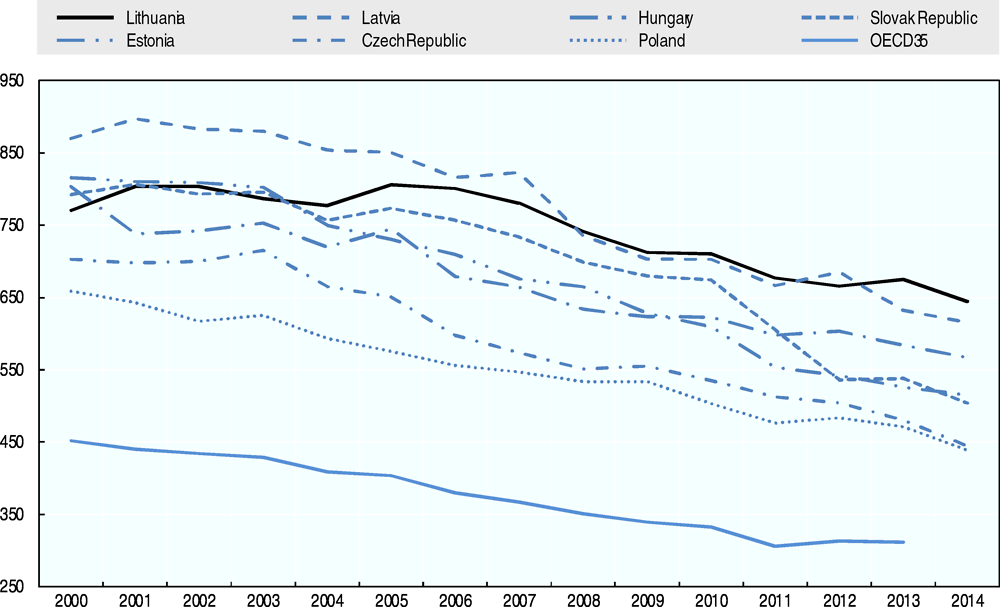

The progress in reducing mortality from CVDs has been slow and inequalities between rural and urban populations prevail in Lithuania. The decrease in death rates from CVDs has been relatively slow by OECD standards, in comparison with other Baltic States, as well as Central European countries (Figure 1.7). In particular, for ischemic heart disease Lithuania records by far the highest mortality both among men as well as women. Regarding cerebrovascular disease (stroke), only Latvia registers higher SDR than Lithuania. While the gender gap in mortality from diseases of circulatory system is large in Lithuania, its relative magnitude is not different from the majority of the OECD countries. Geographical disparities in mortality have been decreasing since 2005 between rural and urban areas in Lithuania. Yet, in 2016 mortality from CVDs was on average 30% higher in rural areas as compared with cities (Statistics Lithuania, 2017).

Figure 1.7. Lithuania’s mortality due to cardiovascular diseases has declined more slowly than in eastern and central Europe

Note: Raw mortality data from the WHO Mortality Database have been age-standardised to the 2010 OECD population

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en (extracted from WHO).

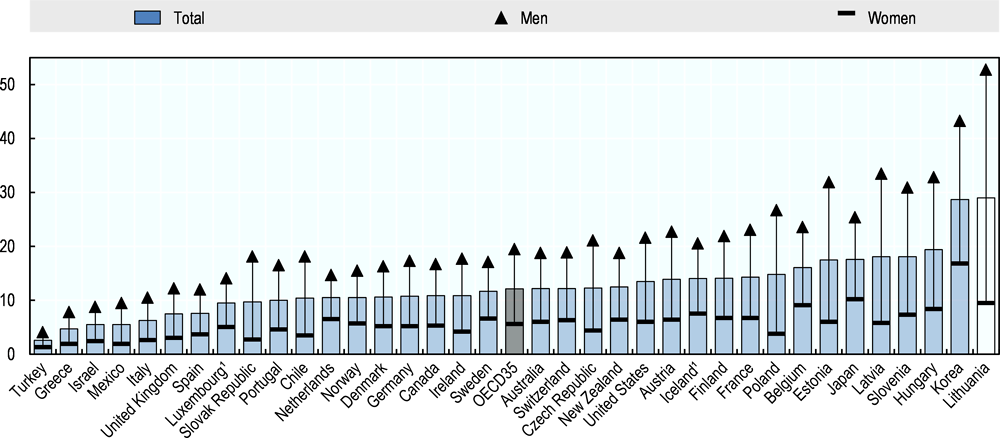

Progress has been achieved in reducing mortality from suicide but it remains a significant cause of death in Lithuania, especially among men. Lithuania records the highest rate of mortality from suicide in the OECD, and the entire Eastern Europe and Central Asia region with the mortality rates for men being more than five times higher than for women (Figure 1.8). The problem can be partially the result of the country’s history, including the transgenerational Soviet trauma - due to genocide, oppression, forced collectivisation and atheisation during Soviet times - and psychosocial strain following the rapid economic and social changes after 1990 (communication from the Ministry of Health, 2016). However, suicide rates are significantly lower in other Baltic states, which share much of the same history. Between 1995 and 2015 mortality rates from suicide decreased by 42% but they continue to be more than double the OECD average for the general population and nearly three-times the OECD average for men (OECD Health Statistics, 2017).

Figure 1.8. Suicide remains a significant cause of death, especially among men in Lithuania

1. Three-year average. Raw mortality data from the WHO Mortality Database have been age-standardised to the 2010 OECD population, including for Lithuania.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en (Age-standardised rates per 100 000 population, 2015).

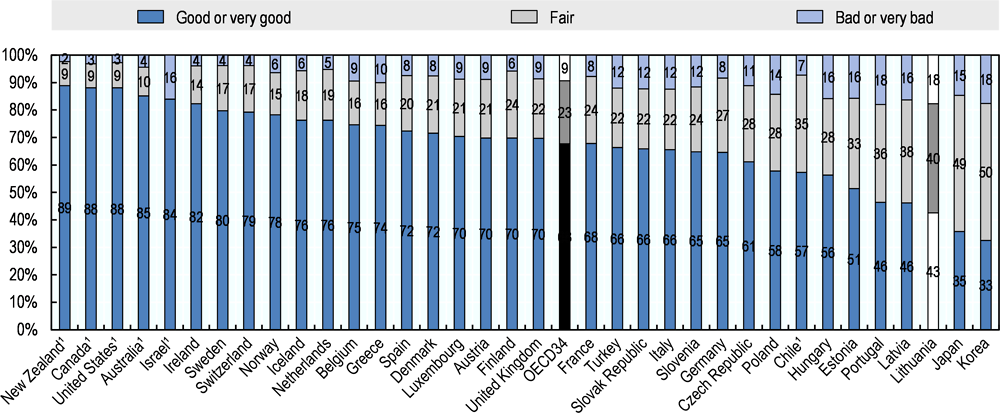

1.2.2. Lithuanians are less likely than citizens of the OECD to report good health

Fewer Lithuanians report being in good or excellent health than in the OECD on average. Only 43% of the population aged 15 years and above reports good or very good health while the OECD average is 68% (Figure 1.9). The share of adult population reporting to be in good or very good health is lower only in Japan and Korea – 35% and 32%, respectively. Along with the Portuguese and Koreans, Lithuanians also most often report being in bad or very bad health - 18% of the population aged 15 years and above.

Moreover, there are large disparities in self-reported health across different socio-economic groups in Lithuania. In 2015, only 32% of Lithuanians with the lowest income (in the lowest income quintile) reported to be in good or very good health while, the proportion among the population in the highest income quintile was nearly double - 63%. On average across the OECD countries, around 80% of people with the highest income and 60% of people with the lowest income report being in good or very good health, so Lithuanians are consistently less likely to report good health (OECD Health Statistics, 2017; OECD, 2017c).

Figure 1.9. Only 43% of Lithuanians report being in good or very good health

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en (EU-SILC for European countries)

Moving to specific diseases, data on the burden of diseases largely mirror mortality data. The main contributions to the burden of disease, as measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)1, are cardiovascular diseases followed by lung cancer, musculoskeletal problems (including low back and neck pain), and mental health problems including major depressive disorders (IHME, 2016; OECD, 2017d). Approximately one third of adults in Lithuania report living with chronic condition (a long-standing illness or health problem lasting or expected to last more than six months), which corresponds to the EU average (Eurostat database, 2017). Regarding communicable diseases, tuberculosis remains more of a concern in Lithuania than the European member countries of the OECD. Despite a substantial decrease in tuberculosis cases from 1 904 in 2011 to 1 507 in 2015, the country still reports the second highest notification rate (new and relapse cases) of tuberculosis in the EU (after Romania) with 52 cases per 100 000 population in 2015, compared to the EU average of 12 cases. An additional challenge is drug resistant tuberculosis (OECD, 2017d; ECDC/WHO Europe, 2017: ECDC, 2017).

Across the board, elderly people in Lithuania report particularly poor health. Only 6% of the population aged 65 and over reports to be in good or very good health, which the lowest rate in the OECD and markedly below the OECD average of 44% (OECD Health Statistics, 2017). Moreover, the average number of healthy life years at age 65 – an indicator of disability-free life expectancy - is among the lowest in the OECD for both women and men – 5.5 and 5 years, respectively. Indeed, more than 75% of Lithuanians aged 65 years and above report living with a long-standing illness or health problem, which is significantly above the EU28 average of 59% in 2016 (Eurostat database, 2017).

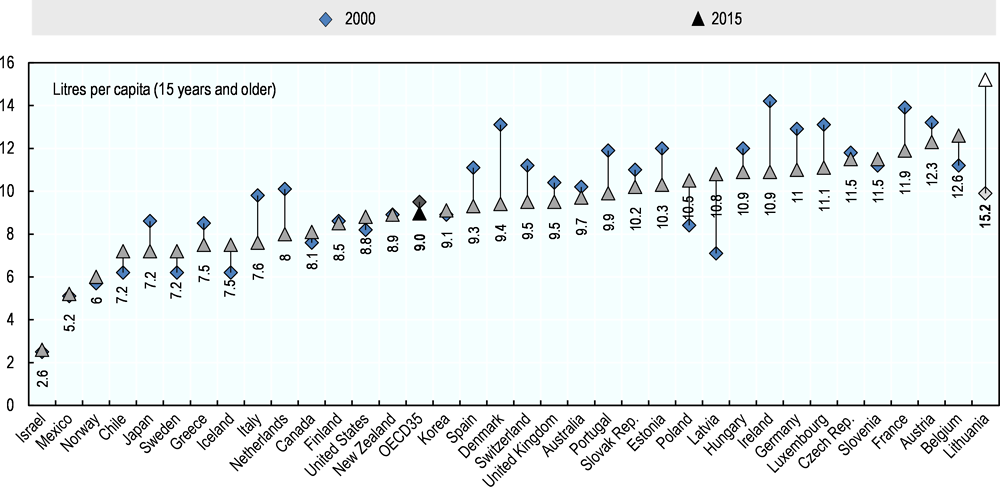

1.2.3. Harmful alcohol consumption is the leading risk factor and continues to increase

Alcohol consumption is a major risk factor behind the leading causes of death in Lithuania. Among Lithuanians aged 15 years and above, the consumption of alcohol per capita is significantly higher than in any OECD country and as much as 69% above the OECD average (Figure 1.10). Alcohol consumption has been on the rise in Lithuania – an opposite trend to that seen in the majority of OECD countries. Over one third (34%) of men in Lithuania engage in regular binge drinking2, which is well above the average for men (28%) in the EU (Eurostat Database, 2017). Moreover, among 15-years-olds as many as 41% of boys and 33% of girls in Lithuania reported having been drunk at least twice in their life, which is the highest for boys and the third highest for girls as compared with the European member countries of the OECD in 2013-2014 (Inchley et al., 2016).

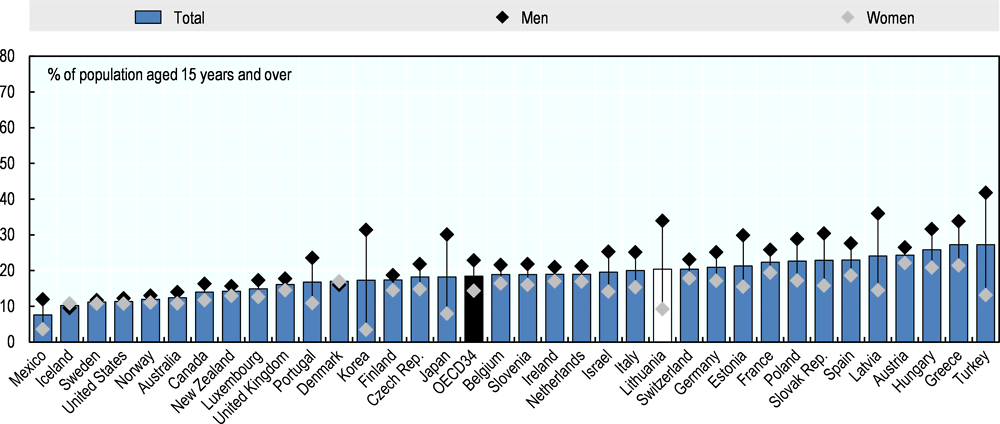

Figure 1.10. Alcohol consumption is higher than anywhere in the OECD

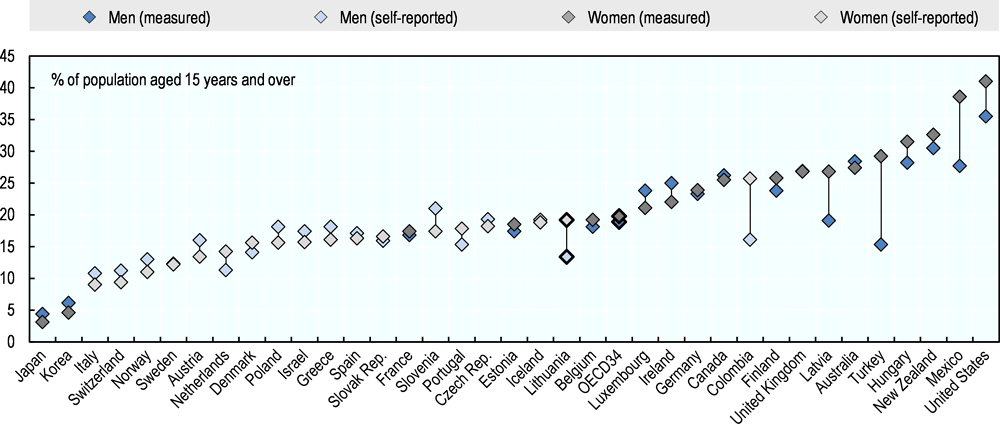

Other risk factors, such as tobacco smoking and obesity, are less widespread than alcohol consumption. In 2015, around 20% of Lithuanians aged 15 and over reported to be daily smokers, which is slightly above average of 18% in the OECD (Figure 1.11). This average masks significant gender differences. While only 9% of women report to smoke daily, the fourth lowest rate as compared with the OECD countries, as many as 34% of men are daily smokers in Lithuania, which ranks the country among top three in the OECD. Nevertheless, unlike alcohol consumption, regular smoking has been decreasing over the recent decade.

Figure 1.11. Men in Lithuania are among the most frequent smokers in the OECD

Obesity in Lithuania is below the OECD average. Obesity rates across different countries are assessed with the use of two different methods – either through self-reported estimates of height and weight derived from population-based health interview surveys, or measured estimates derived from health examinations. Estimates from health examinations are generally higher and more reliable than from health interviews (OECD, 2017c).Based on self-reported data, 16.6% of adults are obese in Lithuania3, well below the OECD average of 19.4%. There are, however, significant differences between women and men in Lithuania (Figure 1.12). While Lithuanian men are among least obese in the OECD, self-reported rate of obesity among women is nearly at part with the OECD average and higher than in most countries of central and Eastern Europe.

Figure 1.12. Lithuanian men are among least obese in the OECD while obesity among women is average

Overall, the gender gap in life expectancy can be attributed at least partly to the differences in risky health behaviours. The above data show that the health behaviour of Lithuanian men is markedly different from that of women, notably with regard to tobacco smoking and smoking kills nine times more males than females (Liutkute et al., 2017). Unfortunately, data on alcohol consumption is not reported separately for men and women, but the fact that death rates from the alcohol-related liver diseases are twice as high for men than women suggests gender patterns are also probably different.

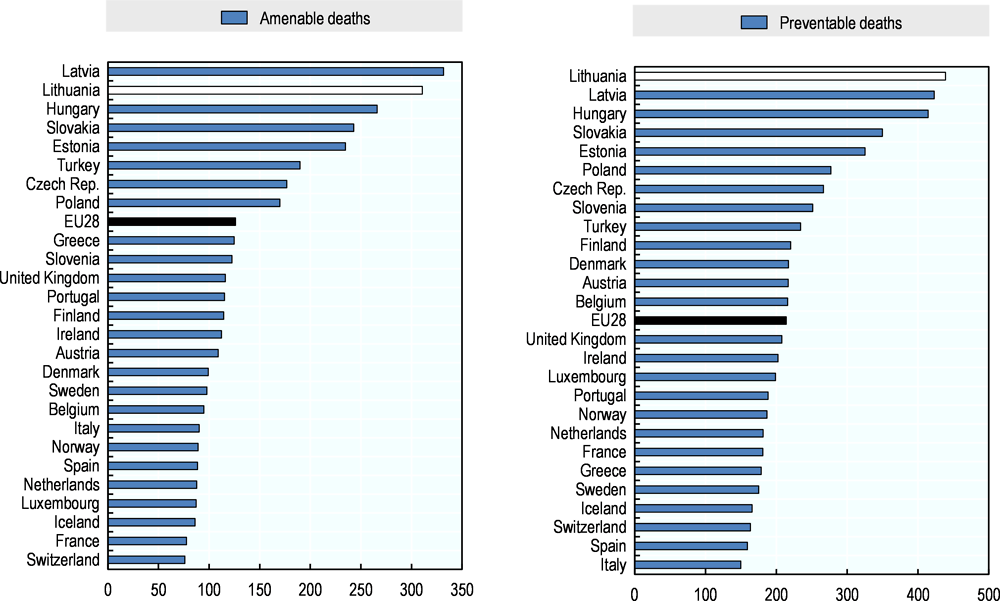

1.2.4. A large number of premature deaths could be avoided

From the perspective of this performance assessment, it is important to highlight that Lithuania has among the high rates of avoidable mortality in the EU. In other words, if more effective public health and medical interventions were in place fewer people would die prematurely in Lithuania. Figure 1.13 presents two different indicators of avoidable mortality for Lithuania and European member countries of the OECD. The left panel presents amenable mortality and shows that after Latvia, Lithuania is the country in which most death could avoided through better quality care. The right panel presents the proportion of deaths which could have been avoided through better control of the wider determinants of health, such as lifestyle or environmental factors. Lithuania has the highest preventable mortality. The largest part of the amenable and preventable mortality is attributable to ischaemic heart disease.

Section 1.2.3 above discusses relatively high population’s exposure to modifiable risk factors, such as alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking in Lithuania. It is difficult to separate the effect of these risk factors and other non-medical determinants of health from the quality of health care to explain the high rates of avoidable mortality. There are, however, clear indications that there is scope for improvement not only in effectiveness of public health interventions but also the effectiveness of health care services in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Chapter 3 of this report in particular will seek to unpack the reasons why the health system in Lithuania is not adequately tackling avoidable mortality.

Figure 1.13. Lithuania has one of the highest rates of avoidable (amenable and preventable) mortality in Europe

Source: Eurostat Database (standardised death rates per 100 000 population, 2014)

1.3. Health spending in Lithuania is on the low side and its structure is similar to that of OECD countries

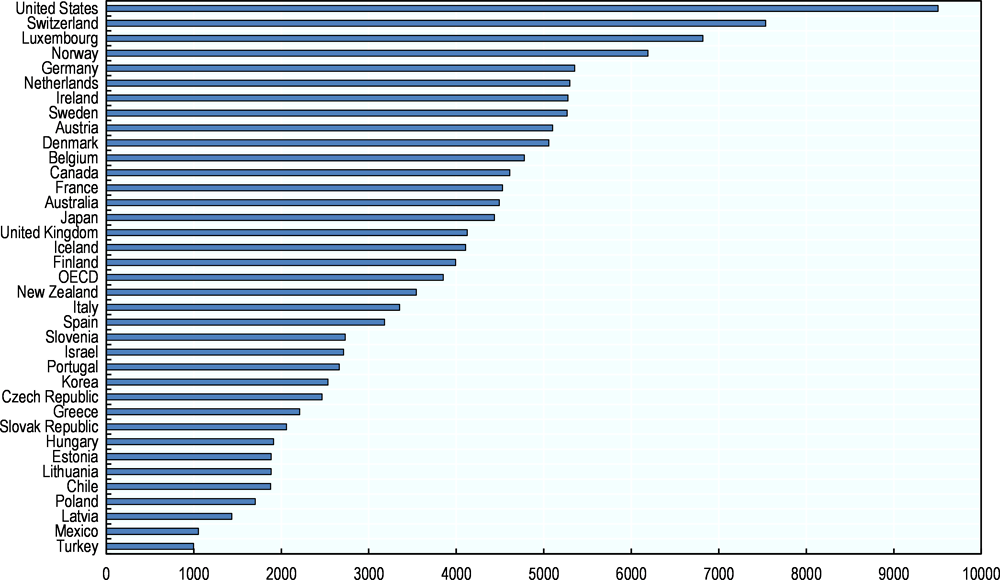

Compared with most OECD countries, Lithuania spends little on health. Expenditure per capita stood at $1 883 adjusted for purchasing power parity in 2015. Lithuania’s spending level is comparable to that of Estonia, a bit above Poland’s and 30% higher than Latvia’s (Figure 1.14). Spending on health represented 6.5% of GDP in 2016 (Figure 1.15). For both measures, Lithuania stands in the bottom quintile of the OECD distribution. Over time, Lithuania efforts to invest in health have increased. While in 2015, spending per capita stood at about half of the OECD average, in 2000, Lithuania’s spending was only about a third of the same average. In other words, Lithuania is climbing in the distribution.

Figure 1.14. People in Lithuania spend around $1 900 a year on health

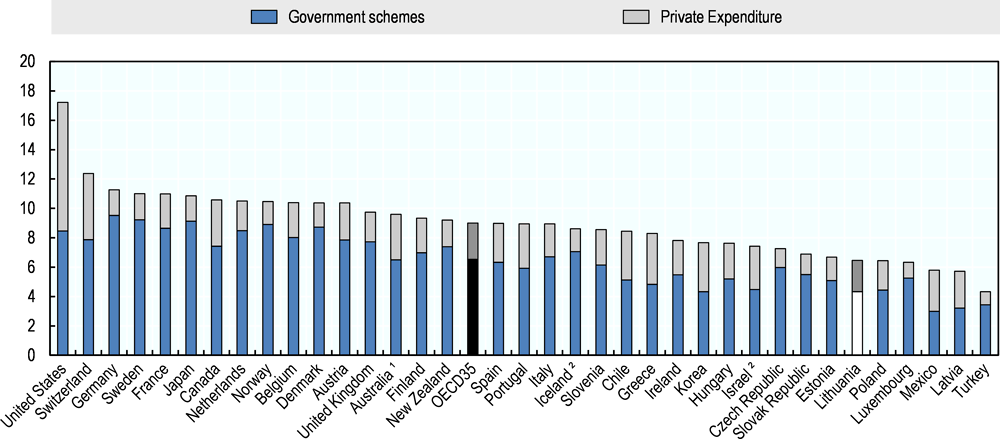

Figure 1.15. Lithuania spends 6.5% of GDP on health, a lower level than most OECD countries

The 2009 crisis put a temporary break on fast-growing health expenditure. In the years leading to the 2009 crisis, health expenditure was growing much faster in Lithuania than in OECD countries: it grew by 11% annually in real terms in 2005-2008 against an average of 4% in OECD countries during the same period. In 2009, health expenditure in Lithuania reached a peak of 7.4% of GDP. It stabilised in 2009 and dropped by 6% in real term in 2010. Subsequently, and until 2013, growth in total expenditure remained slower than in OECD countries. More recently, the annual growth rate of spending has fluctuated but on average been higher than in the OECD (4% per annum vs 3% between 2013 and 2016) – see Figure 1.16.

Figure 1.16. In the past decade, spending has tended to grow faster in Lithuania than in the OECD

The majority of spending on health is publicly financed in Lithuania, but the public share has eroded since the crisis. In 2015, 67% of total spending on health was funded from government sources, lower than the 73% average across OECD countries. However, in 2015, the public share in health spending in Lithuania remained higher than in a third of OECD countries. On the other hand, public spending as a share of total spending which had been slowly increasing between 2004 to reach 72.5% has since eroded. In general, higher shares of public funding are associated with better financial protection and access for the whole population.

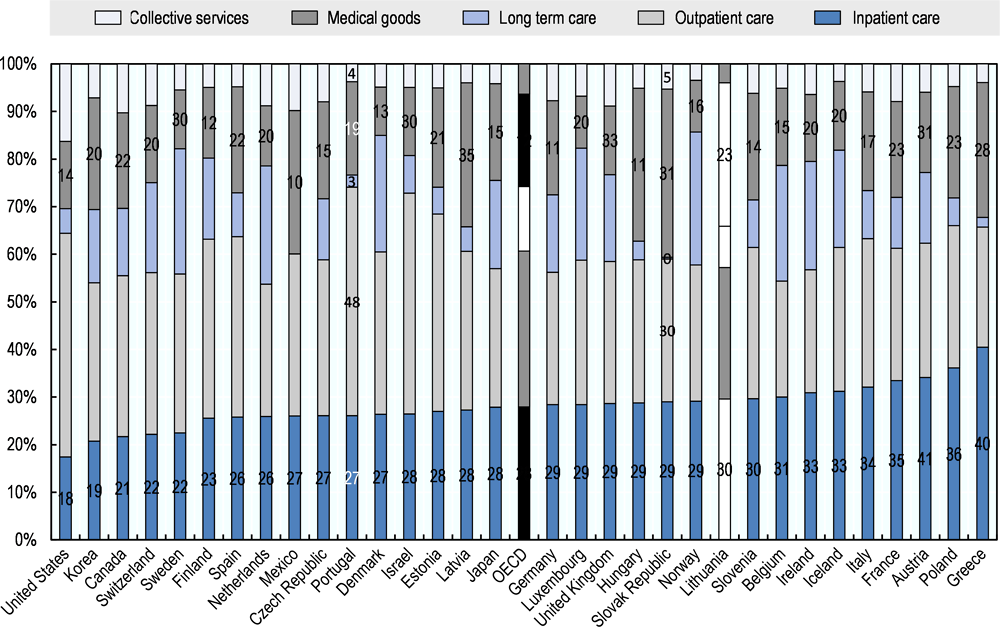

Figure 1.17. Lithuania spends relatively more on medical goods than most OECD countries

Note: Inpatient care refers to curative-rehabilitative care in inpatient and day care settings, outpatient care includes home-care and ancillary services, collective services refers to prevention and administrative costs. Inpatient services provided by independent billing physicians are included in outpatient care for the United States.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

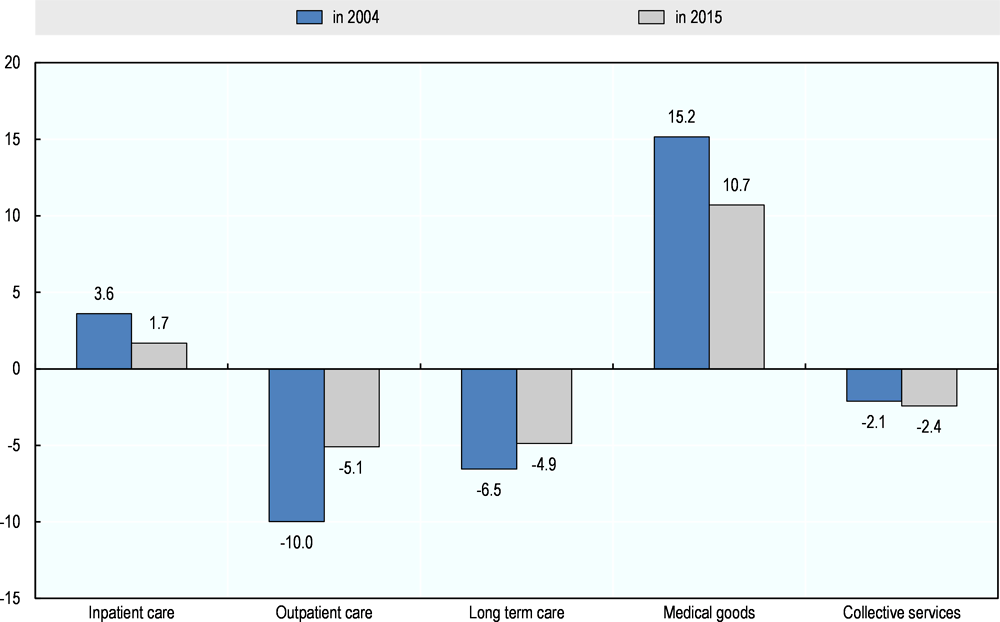

Inpatient services still account for a large share of total spending in Lithuania but the overall spending structure has been converging with OECD averages. Lithuania’s health system – as those in most of eastern and central Europe – developed by putting more emphasis on hospital-centred care to the detriment of outpatient care and health promotion. This dominance of hospital-based care also translated into financial priorities, and post-independence policies have been consistently geared towards rebalancing the system. Today, Lithuania is still characterised by higher spending on inpatient care and lower spending on outpatient care than the average OECD country (Figure 1.17). However, the spending structure is much closer to the average OECD pattern than 10 years ago (Figure 1.18). Compared with the OECD average, Lithuania still allocates more to inpatient care and medical goods and less to long-term care and outpatient care, but the difference is now much lower for most categories of care.

Figure 1.18. Spending patterns across different types of services are getting closer to the OECD averages

Note: In 2004, Lithuania’s allocation to inpatient care was 3.6 percentage points above the OECD average, it is now only 1.7 pp higher.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

1.4. The health system has been profoundly transformed since independence

1.4.1. The system was reorganised after Lithuania regained independence and has been institutionally stable since

In the decades following independence, Lithuania has achieved a profound transformation of its health system. When it declared independence in the early 1990s, Lithuania’s health system was typical of the Soviet Union: an exclusively public, centrally-planned, financially integrated, hospital-centric service delivery system provided services to the entire population. In the following decade, increasing autonomy was granted to large state hospitals, and municipal management and ownership was introduced for out-patient services, local hospitals, and long-term care residential homes. The compulsory health insurance legislation in 1996 was a milestone in moving towards a contractual model with a single third-party payer and relatively autonomous providers.

Reforms in the following decade focused on reorganising service delivery by developing primary health care, restructuring of the hospital system, modernising payment systems, allocating the responsibility for public health to municipalities and introducing new regulation into the system (Murauskiene et al., 2013). With European Union accession, Lithuania made use of structural funds to upgrade its infrastructure. In the past 10 years, the different governments have consistently pursued similar priorities and most stakeholders continue to be aligned behind them, which contributes to the institutional stability of the system.

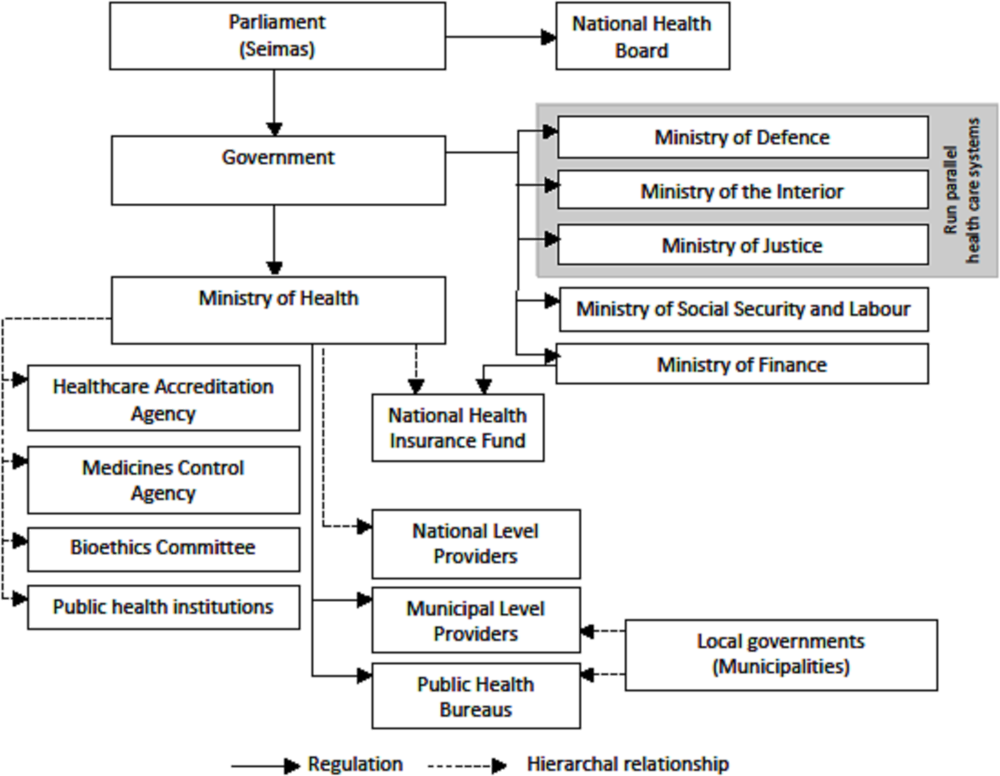

1.4.2. Key regulatory and funding role are played by the Ministry of Health and the National Health Insurance Fund respectively

The Ministry of Health and the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) are the main central institutions, with local administrations playing an important role in service delivery. The Ministry of Health (MoH) formulates health policy and regulation, and also plays a more directly managerial role, from actively governing the NHIF, e.g. by representation in its board, to managing large hospitals. The MoH is supported by a number of specialised agencies, including the State Health Care Accreditation Agency, which is also in charge of HTA and the States Medicines Control Agency.

Insurance coverage is provided to the entire population by the NHIF, financed by contributions from the active population and state transfers on behalf of other categories. The benefit package is broadly defined with few explicit exemptions. Access to primary health care providers and referred services is free of charge, but co-payments on pharmaceuticals can be substantial. The NHIF, through five regional branches, is the purchaser of all personal health services, and contracts with public and private providers. The 60 municipalities of Lithuania own a large share of the primary care centres, particularly the polyclinics, and small-to-medium sized hospitals. They are also responsible delivering public health activities and rely on 45 public health bureaus, which can have service agreements with more than one municipality. They are responsible for health promotion and disease prevention, population health monitoring, and planning and implementing local public health programmes. Figure 1.19 presents a simplified organogram of the current health system.

Figure 1.19. Overall organisation and governance of the health care system – simplified organogram

Source: Authors based on WHO and European Observatory of Health Systems and Policies (2013) Health Systems in Transition: Lithuania Health System Review, Vol. 15 No.2, p. 19.

1.4.3. Service delivery is mixed

Service delivery remains dominated by a large and mostly public hospitals sector but specialist outpatient service delivery is increasingly mixed. In 2015, inpatient services were provided by 70 general hospitals around the country, 22 specialised hospitals and 51 nursing and 3 rehabilitation hospitals. Private facilities play a negligible role in inpatient service delivery. Specialist outpatient care is delivered through the outpatient departments of hospitals or polyclinics, as well as by private providers. In the fast developing day care and day surgery segment, private providers, although they are still few and small, receive around 10% of the amount contracted by the NHIF annually. They also provide around half of diagnostic and interventional imaging services contracted by the NHIF.

Primary care is provided in either municipality-owned or private facilities. Most PHC facilities are owned by the municipalities. The public facilities are typically larger entities owned by municipalities. In 2015, their share of all PHC providers was 39%, enlisting 70% of the population. Private providers tend to work in small practices and covered around 30% of the population in 2015. Regardless of the legal form, all PHC providers are contracted, reimbursed and monitored the same way. Insured people are free to register with the primary care provider of their choice.

The provision of mental health care services has been considerably restructured in the past two decades, with specialised primary care providers playing an increasing role. Earlier mental health care was mostly provided in psychiatric hospitals. Since 1997, significant efforts have been made to increase the role of primary care providers in mental health. At present, more than 100 mental health centres serve as a first point of contact for majority of patients. Most centres consist of multidisciplinary teams, including psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health nurses, and social workers.

Long-term care is predominantly provided in residential care institutions but not all needs are met. Despite the fact that the national and local governments have long recognised the need to develop social services that enable elderly to receive support at home (National Strategy for Overcoming Consequences of Aging, 2004) the legacy of residential long-term services has not been overcome. This is mainly due to municipalities lacking resources and competencies to implement the services enabling care at home. Elderly in a need for long-term care frequently face no choice but to get a place in residential inpatient institutions, but capacity is insufficient. As a result, there are significant waiting times for long-term care services – in 2014, 47% of elderly in need of long-term care were on a waiting list, with an average waiting time of six months (European Commission, 2015; Poškutė and Greve, 2017).

1.4.4. Lithuania needs a more systematic strategy to monitor and address current and future human resource imbalances

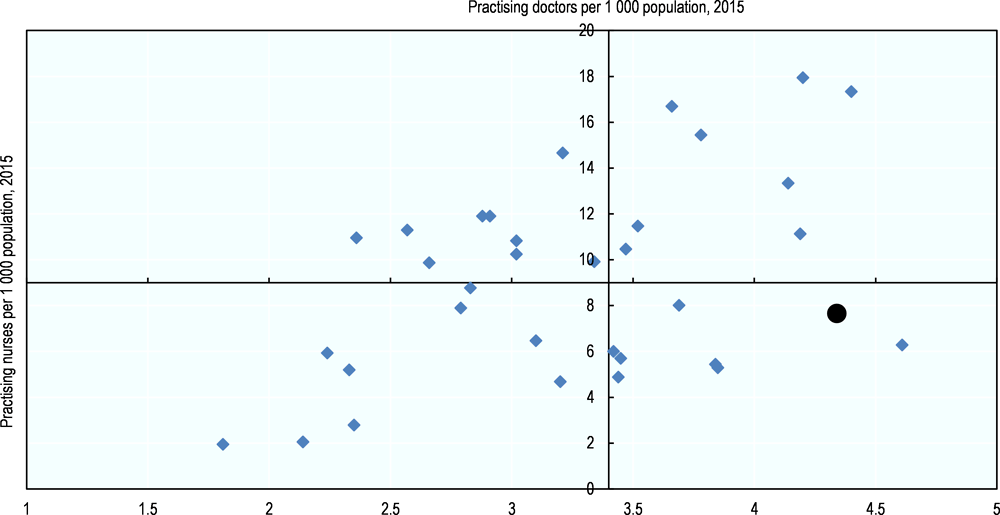

Lithuania has more physicians and fewer nurses than the OECD average. Despite emigration of health staff, Lithuania has retained a high number of physicians: 4.3 per 1000 population versus 3.4 in the OECD (in Figure 1.20 axes cross at the OECD average, 2015). However, 39% of licenced physicians are more than 55 today and many will retire in the next 10 years. The number of nurses in Lithuania on the other hand is relatively low – 7.7 against the OECD average of 9.0 per 1000 population. Consequently, similar to its Baltic neighbours, the ratio of nurses to doctors is relatively low – 1.8 as compared with OECD average of 2.8 (OECD Health Statistics, 2017).

Figure 1.20. Lithuania has a fairly large medical workforce but ratio of nurses to physicians is relatively low

Note: Each point represents an OECD country and the axes cross at the OECD average for both dimensions. Lithuania is the black dot

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

Some measures are in place to address geographic imbalances in the distribution of staff. Specialists, in particular, are unevenly distributed across the country. In order to attract staff in peripheral areas, GPs receive a higher capitation payment for patients registered who live in rural areas or cities in which the population is below 4000, Hospitals and municipalities also offer higher salaries. In conjunction with municipalities, the government has recently put in place grants for medical students willing to work in remote areas. Overall though, no systematic tools are in place to assess future needs and gaps, or to evaluate the impact of current policies.

1.5. Improving health is a clearly stated priority for Lithuania but more attention to policy impact is required.

1.5.1. Lithuania recognises health outcomes are lagging and the need for a comprehensive approach to tackling its determinants

Health features as a prominent inter-sectoral priority across Lithuania’s main strategic planning documents. A large number of interconnected strategies and related action plans outline the country’s strategy when it comes to health. “Health for All” is one of three horizontal priorities of the country’s national development strategy, “Lithuania 2030”. The implementation of this “Health for All” horizontal priority is foreseen by a specific intersectoral action plan coordinated by the Ministry of Health and involving 9 other Ministries which are in turn in charge of developing – and funding - their own related action plans. Another set of inter-ministerial strategy and plans specifically focuses on drug, alcohol and tobacco control and prevention (OECD, 2015a). Overall, these documents demonstrate a clear recognition that improving health requires efforts beyond the health sector.

Stakeholders in Lithuania agree on priorities which are aligned with the burden of disease and reforms which are conducive to achieving these objectives. The Lithuanian health strategy 2014-2025, adopted in 2016 builds on an earlier vision document (Lithuania’s health programme 2014) articulated around a life-course approach which emphasises the importance of tackling health determinants and reducing inequalities. The strategy specifically targets the excessive burden of cardio-vascular diseases and recognises the need for additional emphasis on mental health. The programme of the new government, approved by the parliament in December 2016, makes a priority of tackling harmful alcohol abuse and other determinants of non-communicable diseases. It also intends to pursue and deepen the rebalancing of service delivery including the strengthening of primary care and the restructuring of the hospital sector. In the past 10 years, in a context of institutional stability, the different governments have consistently pursued similar priorities and most stakeholders continue to be aligned behind them. In other words, many conditions are met for Lithuania’s health system to deliver increasingly good results.

1.5.2. More emphasis is required on the analysis of data and evidence to support decision-making at all levels of the system.

Policy impact evaluation needs to be strengthened. At the level of the Ministry, the above mentioned strategies and concomitant action plans are further detailed in programmatic documents which present, for each domain, the activities which will be undertaken as well as the expected results. Each document typically includes a monitoring framework on which reporting is carried out at regular intervals. Overall, this is very commendable and conducive to accountability for all programmes, but a closer analysis of the monitoring framework often reveals that they focus on assessing whether actions have been implemented in the planned timeframe rather than whether they have helped achieving the intended outcomes. In other words, insufficient attention is put into evaluating the effectiveness of implemented policies, in understanding what may or may not have worked or why and what course-adjustments might be required to achieving better results faster. Various stakeholders openly recognise that the resources to analyse results and policy impact are limited. Developing in-house capacity or partnering with outside (academic) institutions, including those who collect data, are options which should be explored to design more sophisticated logical frameworks and better understand – and transparently demonstrate - policy impact.

Lithuania’s already rich data infrastructure must be more systematically put to use to analyse and hold stakeholders accountable for performance. Institutions which deliver services, in particular hospitals and primary care providers, all report on numerous performance indicators to the NHIF, the Ministry of Health and related institutions (although private providers tend to under-report). In many cases, this information is made public and availed to patients in a way which allows them to access it on a facility by facility basis, which is conducive to transparent decision making. For hospitals at least, the Ministry holds an annual meeting to discuss performance with all facilities. However, the available data is often not used to its full extent or synthesised in a way which could systematically and easily be used to compare performance. Summary statistics, dashboards or league tables are not readily available, and joint-analysis of data coming from different information systems is not undertaken. Despite their important role in service provision and public health, no information is available about the relative performance of municipalities and/or local health systems. Information is also not fully exploited. For instance, although cancer registries exist, data on survival rates is not available.

Recent steps show progress in this direction. The MOH decision to report to the OECD the Health Care Quality Indicator database in 2017 is a welcome development. A December 2017 order established a list of quality and efficiency indicators used to in order to assess each hospital’s performance. Still, overall, additional resources and efforts are required to facilitate data-driven performance assessment and decision making.

1.5.3. The e-health infrastructure, still under development, will also facilitate information driven decision making

Since the early 2000s, a comprehensive eHealth system has been developed. In 2017, 12 types of medical records (including prescriptions, referrals, hospital discharge summaries, outpatient visit summaries, laboratory tests, radiological image reports) and 8 certificates (birth, death etc.) can be electronically produced, stored, and exchanged. The information is linked to a unique patient Electronic Health Record (EHR) which can be accessed by providers and patients.

The reach of e-health is expanding. As of March 2018, 554 health care institutions (out of 900) were connected to the eHealth system and had sent at least one document electronically, which is more than double the number a year before (all figures provided by the Ministry of Health). An additional 121 have expressed interest in concluding a data provision agreement and join the system. Providers who are not fully connected can consult the available information through a secure portal. By the end 2017, EHRs had been created for nearly 95% of the population and more than 15 million medical documents were stored electronically (around 5 records per EHR, when the coverage one year earlier was 70% of the population and one record per EHR). However, not all patient health data is currently provided to the central system and it will take time for e-Health to be embedded in the system.

Electronic data collection has also been established for the purpose of monitoring and publicly reporting waiting times for PHC services, specialised out-patient consultations, in- patient and day-surgery, as well as selected expensive examinations (e.g. CT scanning). The waiting time data is collected by the NHIF and reported to the Ministry of Health as well as the public on monthly basis.

The eHealth system is to be completed under the current E-Health System Development Programme 2017-2025 and The Action plan of E-Health System Development Program for 2018-2025. Yet, the details on funding and organisation of the remaining infrastructure investments are not entirely clear. Past implementation strategies suffered from inconsistencies that contributed to sub-optimal use of funding and created resistance among providers. Many hospitals, for instance, invested in local e-health systems that were later made obsolete by the national infrastructure developed by the MoH. Lessons should be drawn from these examples in order to ensure a successful completion of the system by 2025. Moreover, it would be worthwhile to explore how the eHealth system could lower the providers' workload related to data reporting by, for example, being used for the purpose of activity reporting to the NHIF.

Conclusion

After the collapse of the central planning system in 1991, Lithuania experienced a difficult but rapid transition to market economy. Growth has generally been faster than in OECD countries, but the economy has been vulnerable to external shocks and still faces serious challenges such as high income inequality and a large share of a fast-aging population at risk of poverty.

Along with the economic progress, Lithuania has achieved a profound transformation of its health system in the decades following independence. Lithuania provides coverage to its population through a single health insurance scheme which contracts public and private service providers. Primary health care is well developed and the restructuring of the hospital system in progress. Modern payment methods and regulations have been steadily introduced, in a general context of institutional stability. Most institutional elements of well-performing systems are in place but health spending remains low by OECD standards and out-of-pocket payments represent a larger share than in most OECD countries.

Despite the substantial progress, Lithuania continues to face important challenges as the health status of the population ranks among poor performers of the OECD countries. While the burden of disease is not dissimilar to that of the OECD countries, most of them have achieved more rapid progress in reducing mortality rates. Behavioural health risk factors are not well controlled, especially harmful alcohol consumption which is markedly higher than in any OECD country and continues to increase.

These challenges are well recognised in Lithuania and there is a remarkable consensus among stakeholders behind priorities which are aligned with the burden of disease and reforms which are conducive to achieving these objectives. At the same time, insufficient attention is given to evaluating the effectiveness of the policies implemented and in understanding the course-adjustments required to achieving better results faster. Lithuania’s already rich data infrastructure must be more systematically put to use to analyse and hold stakeholders accountable for performance. This message carries across the following two chapters of this review which examine in greater details four dimensions of performance: access and sustainability (Chapter 2), quality and efficiency (Chapter 3).

References

Arslan, C. et al. (2014), “A New Profile of Migrants in the Aftermath of the Recent Economic Crisis”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 160, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jxt2t3nnjr5-en.

ECDC (2017), Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe 2015, Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net).

ECDC/WHO Regional Office for Europe (2017), Tuberculosis Surveillance and Monitoring in Europe 2017.

European Commission (2015), Gaps in the provision of long-term care services in Lithuania, ESPN – Flash report, 2015/51.

European Commission (2015), “The 2015 Ageing Report: Economic and Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Countries (2015-2060)”, European Economy Series, No. 3.

Inchley, J. et al. (eds.) (2016), “Growing Up Unequal: Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young People’s Health and Well-being”, Health Behaviour in Schoolaged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report from the 2013/2014 Survey, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen.

Liutkute, V. et al. (2017), “Burden of smoking in Lithuania: attributable mortality and years of potential life lost”, The European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 27, No. 4, 736–741.

McDaid, D., E. Hewlett and A. Park (2017), “Understanding effective approaches to promoting mental health and preventing mental illness”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 97, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/bc364fb2-en.

Murauskiene, L. (forthcoming), Moving towards universal health coverage: new evidence on financial protection in Lithuania, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen.

Murauskiene, L. et al. (2013). Lithuania: health system review. Health Systems in Transition, Vol. 15, pp. 1-150.

OECD (2017a), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2017 Issue 1, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2017-1-en.

OECD (2017b), Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2017-en

OECD (2017c), “Lithuania”, in International Migration Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2017-27-en.

OECD (2016a), OECD Economic Surveys: Lithuania 2016: Economic Assessment, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-ltu-2016-en

OECD (2016b), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2016 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2016-2-en.

OECD (2015a), Lithuania: Fostering Open and Inclusive Policy Making, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264235762-en.

OECD (2015b), Investing in Youth: Lithuania, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264247611-en.

Poškutė, V. and B. Greve (2017), “Long-term care in Denmark and Lithuania – A most dissimilar case”, Social Policy & Administration, Vol. 51, No. 4, pp. 659-675.

Statistics Lithuania (2015), Results of the Health Interview Survey of the Population of Lithuania 2014 Lietuvos statistikos departamentas, Vilnius, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/services-portlet/pub-edition-file?id=20908.

Notes

← 1. DALY is an indicator used to estimate the total number of years lost due to specific diseases and risk factors. One DALY equals one year of healthy life lost (IHME)

← 2. Binge drinking behaviour is defined as consuming six or more alcoholic drinks on a single occasion, at least once a month over the past year

← 3. Obesity is defined as Body Mass Index (BMI) greater than 30.