This second chapter addresses the sustainability of Lithuania’s health system and the extent to which it is able to provide access to care. Public spending on health was protected during the financial crisis and has been generally kept in check, which, along with available expenditure projections, suggests the system is on a financially sustainable path. Despite high out-of-pocket spending, available data suggest access to services is reasonable and socio-economic differences less pronounced than in other countries. Pharmaceutical policy is a domain where Lithuania, like most countries, struggles to balance considerations of access and sustainability.

OECD Reviews of Health Systems: Lithuania 2018

Chapter 2. Health care system in Lithuania: Access and sustainability

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

This second chapter assesses Lithuania’s health system with regards to its sustainability and ability to provide access to care. Lithuania’s spending on health is low and available expenditure projections suggest the system is on a broadly sustainable path in financial terms (2.1). Furthermore, despite low public spending, access to care is reasonable (2.2). Pharmaceutical policy is a domain where Lithuania, like most countries, struggles to balance considerations of access and sustainability (2.3).

2.1. Lithuania’s investment in health remains low by international standards and so far on a sustainable path.

By international standards, and given its income, Lithuania spends relatively little on health (2.1.1). Lithuania made significant efforts to protect public financing of health during the financial crisis (2.1.2) and deploys generally effective mechanisms to keep public spending in check (2.1.3). So far, the system seems to be on a financially sustainable path but consideration should be given to investments targeted at improving financial protection and increasing the effectiveness and quality of care (2.1.4).

2.1.1. Lithuania spends relatively less on health than countries of comparable income

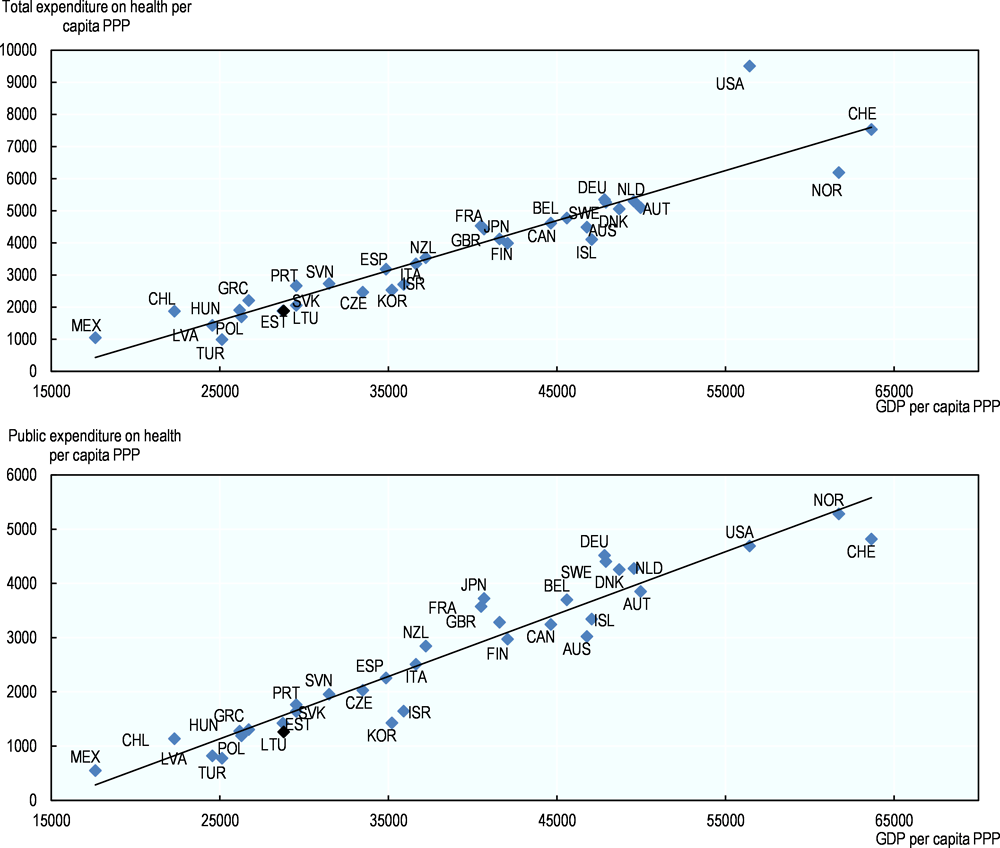

Even accounting for the fact that Lithuania’s income is at the low end of the OECD distribution, its health expenditure is low. Relative to income per capita, total and public spending on health tends to be higher in countries with higher income. Lithuania lies below the trend line, meaning that, even correcting for income, it spends less on health per capita than most OECD countries (Figure 2.1 top panel). A similar picture holds for public funding for health (bottom panel). Estonia and Latvia are also below the trend line.

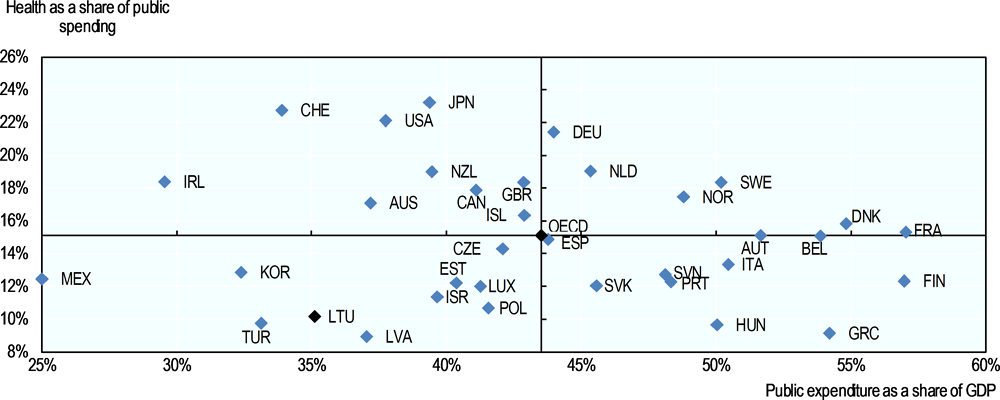

Figure 2.2 shows Lithuania vis à vis the OECD countries on these two dimensions. The horizontal axis plots total government spending relative to GDP in OECD countries, which is 45% on average. The vertical axis shows the proportion of public spending on health. On average, OECD countries spend 15% of their public budgets on health. Thus the various data points represent OECD countries and show how they differ both in the size of government (first criteria) and in their relative prioritisation of health in public expenditure. The OECD average is represented by the point where both axes meet. Lithuania lies in the bottom left quadrant of the graph. Only a handful of OECD countries have a lower share of public spending relative to GDP than Lithuania’s 35%. In addition, with around 10% of public spending dedicated to health in 2015, Lithuania is also among countries which give relatively low priority to the health sector. Only 4 OECD countries, including Latvia, spend a lower proportion of their public budgets on health.

Figure 2.1. Total and public spending on health in Lithuania are lower than can be expected

Note: Ireland and Luxembourg, where a significant proportion of GDP refers to profits exported are excluded.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en, OECD (2017), Government at a Glance 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

Low public investment in health is the result of a relatively low level of government involvement in the economy overall, together with a low priority accorded to health.

Figure 2.2. Lithuania has a comparatively small public budget and does not make health a high priority in public spending

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en, OECD (2015), Government at a Glance 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2015-en.

2.1.2. Lithuania protected public financing on health during the crisis

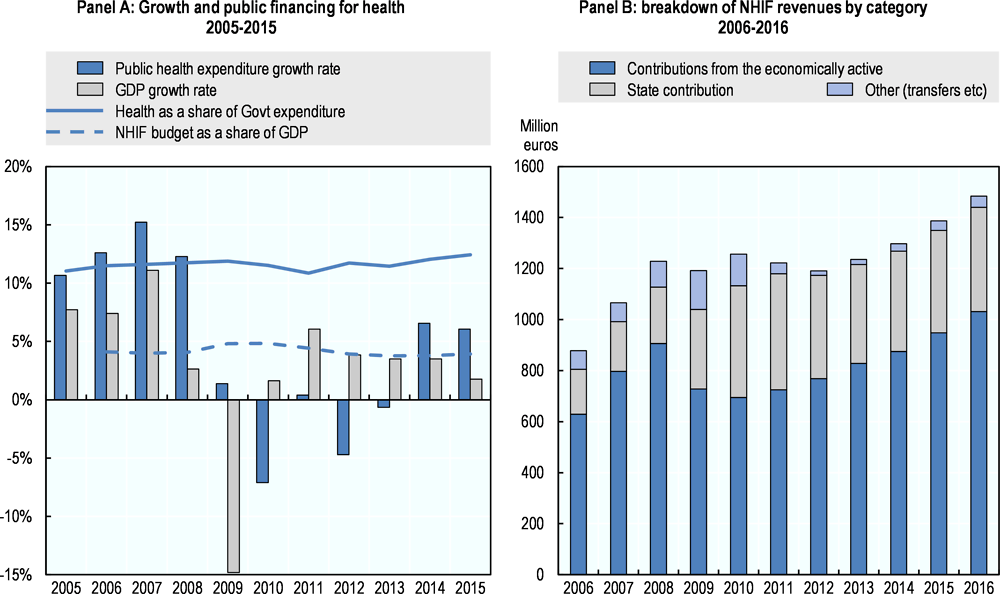

Nevertheless, Lithuania chose to protect its core spending on health during the financial crisis. In 2009 Lithuania faced a deep financial crisis. Gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 15% in real terms and in 2010 unemployment rose to 18%. In response the government implemented strict fiscal consolidation measures, including reductions in public wages, temporary cuts to pensions, and reductions in selected social benefits (Kacevičius and Karanikolos, 2015). In 2009 however, public spending on health remained roughly stable. And although it declined by 7% the following year, in 2009-2010, the NHIF budget – which directly funds access to care – reached nearly 5% of GDP, a higher share than previously (Figure 2.3, Panel A).

The mandatory state contribution to the NHIF on behalf of the economically inactive population was instrumental in protecting health spending during the crisis. The NHIF draws its revenues from two main sources: (i) a compulsory 9% earmarked contribution for employed people (who represent around 80% of the economically active population1) and (ii) a transfer from the state to cover the unemployed, children, pensioners, students etc. who generally are economically inactive. For each person in this second category, the NHIF receives a flat amount that is tied to the average gross monthly salary lagged by two years. During the crisis, revenues collected from the active population dropped sharply, but at the same time transfers from the state increased with the increased number of unemployed. The share of public funding in NHIF revenues rose from less than 20% before the crisis to around 35% between 2010 and 2013 (Figure 2.3, panel B). It has been decreasing again since and it stood at 27% in 2016. On the expenditure side, the NHIF reduced fees paid to most providers in 2009 and 2010, but primary health care expenditure was largely exempted from the cuts.

Overall, the public health financing architecture in place proved to be very resilient in the face of this major financial crisis and in this respect, Lithuania is widely recognised as a good practice example (Kacevičius and Karanikolos, 2015, OECD/European Observatory, 2017).

Figure 2.3. Countercyclical financing for health during the financial crisis

2.1.3. Budget management procedures are effective at keeping public spending in check

In general, the laws and regulations governing the Lithuanian health sector have proven effective in maintaining public health budgets within the planned parameters.

By law, the NHIF must balance revenues and expenditure each year. Every year, a 1.5% provision is set aside from the funds earmarked to cover health care in the NHIF budget before contracts are signed with providers. At the end of each year, funds are first reallocated across providers that have delivered below or above targets, then based on local negotiations any reserves are used to compensate providers where more services have been delivered than planned.

NHIF also builds up reserves which can be used for specific purposes. The NHIF is more generally allowed to build reserves up and use them in case of revenue shortages or unexpected expenditure increases. By the end of 2009, accumulated reserves represented 7% of the budget but declined to an average of 3% in the following 4 years, reaching 4% in 2014 and 2015. In 2016 and 2017, part of the NHIF’s reserves were directed by Ministerial Order to cover increases in base tariffs of personal services of 5.5 and 4.1% respectively, with a recommendation that the proceeds in turn finance planned increases in the base salary of health workers (see below). At the end of 2016, the NHIF reserve had dropped again to 1% of the budget. It rose to 3% at the end of 2017. The budget voted for 2018 planned on the reserve to reach 9% again but this plan is unlikely to hold as new tariff increases will need to be accommodated.

The finances of public institutions delivering health services are also sound (in contrast to a number of countries in the region where public facilities are often in deficit and accumulate debts). In 2016, out of nearly 280 public facilities of all levels, around three quarters posted a positive financial result (84% the previous year). Their cumulative balances amounted to 23 million euros while the deficits of the facilities in the red amounted to 3.5 million euros. Detailed data suggest that municipal hospitals and primary health care centres are under more financial pressure than other types of institutions, with larger hospitals mainly running surpluses.

2.1.4. The system so far is on a financial sustainable path

So far, Lithuania’s health system is on a financially sustainable path. As seen above, Lithuania’s spending is on the low side and from a public finance perspective, well kept in check. Additionally, Lithuania’s health expenditure is not projected to grow as quickly as that of other EU new member states (EU-NMS). Under the reference (Aging Working Group, AWG) scenario of the 2013-2060 EU projections, public health expenditure as a share of GDP is expected to grow by 1.1 percentage points in EU-NMS. Lithuania, with a projected growth of 0.1 p.p. is, together with Belgium, one of the two countries with the lowest anticipated growth in public health expenditure among EU countries. On other hand, where public expenditure on long term care in EU-NMS is expected to rise by 0.7 percentage points of GDP during the period, Lithuania’s expenditure is projected to grow more (by 0.9 p.p.) (European Commission 2015). The overall picture is thus one of financial sustainability.

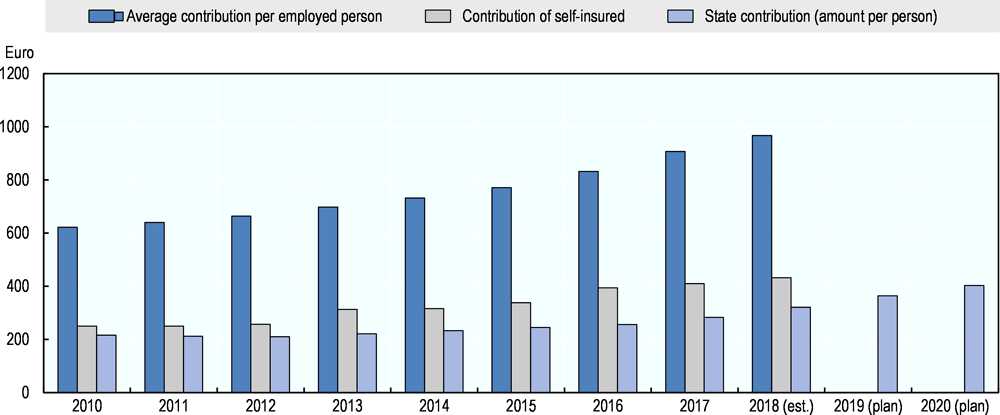

The various NHIF revenue streams are being rebalanced to accommodate demographic change. All contributions are defined in the Health Insurance Law. The contribution of the State on behalf of the economically inactive is computed as a percentage of the average employee salary lagged by two year. Figure 2.4 charts the amount of that contribution as well as the average contribution of the employed and the contribution of the self-insured over time. In 2016, the contribution for the inactive was a third of the employed contribution and 65% of the self-insured contribution. In the years preceding, the contribution for the inactive had in fact tended to grow more slowly than for the other two categories. In the absence of this contribution for the inactive (or if it erodes), the redistribution between the employed and the inactive, and thus the contribution rates for the employed, would need to be higher, especially as the population covered, mostly children and pensioners can be expected to have higher expenditure than the employed. In a context where the working population continues to decline rapidly, some measures have already been taken to rebalance revenue streams over time.

Figure 2.4. The State contribution on behalf of the economically inactive is a third of the average contribution per employed person

Source: NHIF. Current Euro.

Specifically, the contribution of the State on behalf of each economically inactive person is increasing. Starting in 2017, the amount per person is programmed to increase by 2 percentage points every year until it reaches the same level (in Euro) as the contribution of the self-insured, which should happen around 2021.

On the expenditure side, significant increases in salaries are being granted to health workers. As mentioned earlier, and by Ministerial order, the proceeds of the 2016 and 2017 increases in the base tariffs of health care services were used to raise salaries. As a result, in 2016, the salaries of all staff working in health institutions increased by 8% and in 2017, a further 8% increase was granted to nurses and physicians. A new agreement was reached in December 2017 between Trade Unions and the Ministry of Health to implement additional increases over the next few years. A first increase of 20% is set to take place in May 2018 for all staff working in health institutions with a priority given to those with the lowest salaries and should also be funded through increases in NHIF tariffs.

In addition, fairly ambitious targets are set for health workers salaries in relation to the average wage in the economy. The 2017 collective agreement states that by mid-2020, the salaries of physicians should be no less than 3 times the average wage in the country and that of nurses no less than 1.5 times that average. The comparison of health workers income with average wages must be undertaken with caution and differences between self-employed and salaried workers are marked, as the latter tend to be lower in most countries. In OECD countries for which data is available, salaried generalists earn around 2 times the national average and salaried specialists around 3 times the average wage (OECD, 2017). Assuming staff targeted by the above collective agreement are mostly salaried workers, and depending on how the salary target is declined between specialists and generalists, the target may be ambitious but could also align Lithuania with average practices in the OECD. As for nurses, across the OECD, those who work in hospitals tend to earn 1.15 times the average salary and the 1.5 Lithuania target may seem ambitious. In any case, statistics are not readily available on the current levels of health workers income compared with average wages in Lithuania and the cost of reaching the targets laid out in the agreement does not appear to have been estimated. It is therefore difficult to ascertain the extent to which they are realistic and whether they could be met given available public resources.

Consideration should be given to increasing public funding for health but additional investments targeted to improve the performance of the health system as whole. There is no doubt that some pressure exists to increase salaries in the hope to retain staff to work in the health sector in Lithuania. Relative levels of remuneration across countries can play a role in staff retention, but are not the only element. Overall, a more in depth analysis of the labour market dynamics for health workers in Lithuania should be undertaken and a comprehensive strategy devised to address current and future human resources imbalances more systematically. More broadly, blanket salary increases should not be the only driver of public health spending. Additional public funding is necessary to improve the population’s health outcomes and financial protection, but investments should be targeted to the amenable burden of diseases and based on evidence of effectiveness.

2.2. Despite significant out-of-pocket payments, coverage provides effective access to services with limited inequalities.

Lithuania’s health insurance scheme provides coverage to the population for a large range of services (2.2.1). Coverage is however not very deep and out-of-pocket payments are higher than in most OECD countries (2.2.3). Nevertheless, access to services is reasonable and fairly well distributed across income groups (2.2.3).

2.2.1. Lithuania’s health insurance scheme provides coverage to the population for a large range of services

The population is adequately covered by the public health insurance scheme managed by the NHIF. All citizens and legal residents are required to seek coverage from the NHIF and the vast majority comply. As in many countries in the region, especially those with high levels of emigration, the number of residents is not known precisely, but statistics indicate that of the 3.1 million people officially eligible for public health insurance in 2016, more than 92% were covered. However, many of the 8% uninsured (around 250,000 people) are believed to have settled abroad2. NHIF experts estimate that the actual proportion of residents lacking coverage probably lies between 2 and 4%, many of whom operate at the fringe of the formal economy3. The uninsured are officially entitled to free emergency care. The state guarantees coverage for the economically inactive. During the crisis, as the number of unemployed rose, the proportion of the economically inactive in the insured population grew to a peak of 71% in 2011, and it has been steadily declining since, to about 54% in 2016.

Coverage is quite broad but patient copayments apply on most outpatient medicines. The insured are entitled to a broad range of rather loosely defined personal health services. A positive list indicates those medical goods and medicines that are reimbursed. For drugs used in ambulatory care, reimbursement rates range between 50 and 100% depending on the condition and whether the patient is a child, a pensioner, or a person with disabilities (with the majority covered at 80 or 100%). Reimbursement can also be tied to specific indications. For example, until 2016 statins were only reimbursed for secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Lithuania now is aligned with many other countries’ guidelines that recommend their use in primary prevention in certain patients (e.g. NICE, 2014).

The co-payment rules for medicine are complex and some recent measures have aimed at curbing them. For all medicines but the cheapest within a group of medicines with the same active substance4 patients pay a fee of between 0.2 and 1.5 EUR per package, depending on the total price. In general, the reimbursement rate is applied to the reference price, which cannot exceed 95% of the average of the lowest prices in each of eight reference countries5 (plus a regulated pharmacy mark-up and VAT). However, the retail price of a drug (i.e. the price at which a manufacturer offers the drug on the Lithuanian market) may bear no relation to the reference price. Indeed, retail prices of most prescription medicines are often significantly higher than their reference prices (Ministry of Health, Lithuania, 2017), with patients required to cover the difference. This markedly increases the magnitude of out of pocket costs for outpatient medicines. Since 2010, pharmacies are required to offer the cheapest generic in a group of medicines at a retail price not exceeding the reference price. Moreover, since 2017, for a brand to be included in the positive list of reimbursed drugs, the retail price cannot exceed the reference price by more than 10%. However this rule only applies to groups of medicines with at least three manufacturers (Ministry of Health, Lithuania, 2017).

2.2.2. Out-of-pocket payments are among the highest in the OECD and informal payments remain frequent.

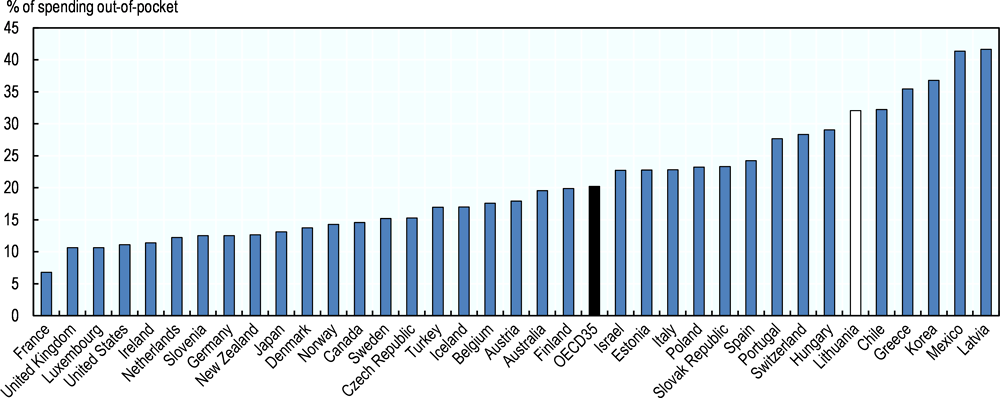

Out-of-pocket payment are high in Lithuania, especially on medicine

In 2015, out of pocket payments represented around 32% of health spending in Lithuania, among the highest levels in the OECD (see Figure 2.5). Private health insurance is not developed in Lithuania, thus the bulk of private spending is out of pocket (OOP). The proportion of health expenditure paid OOP was around 33% in the mid-2000s, decreasing somewhat during the financial crisis due to a sharp reduction in private relative to public spending growth rates, and has risen again after 2012. Spending on medicines and medical goods represents 64% of OOP and ambulatory services another 29%.

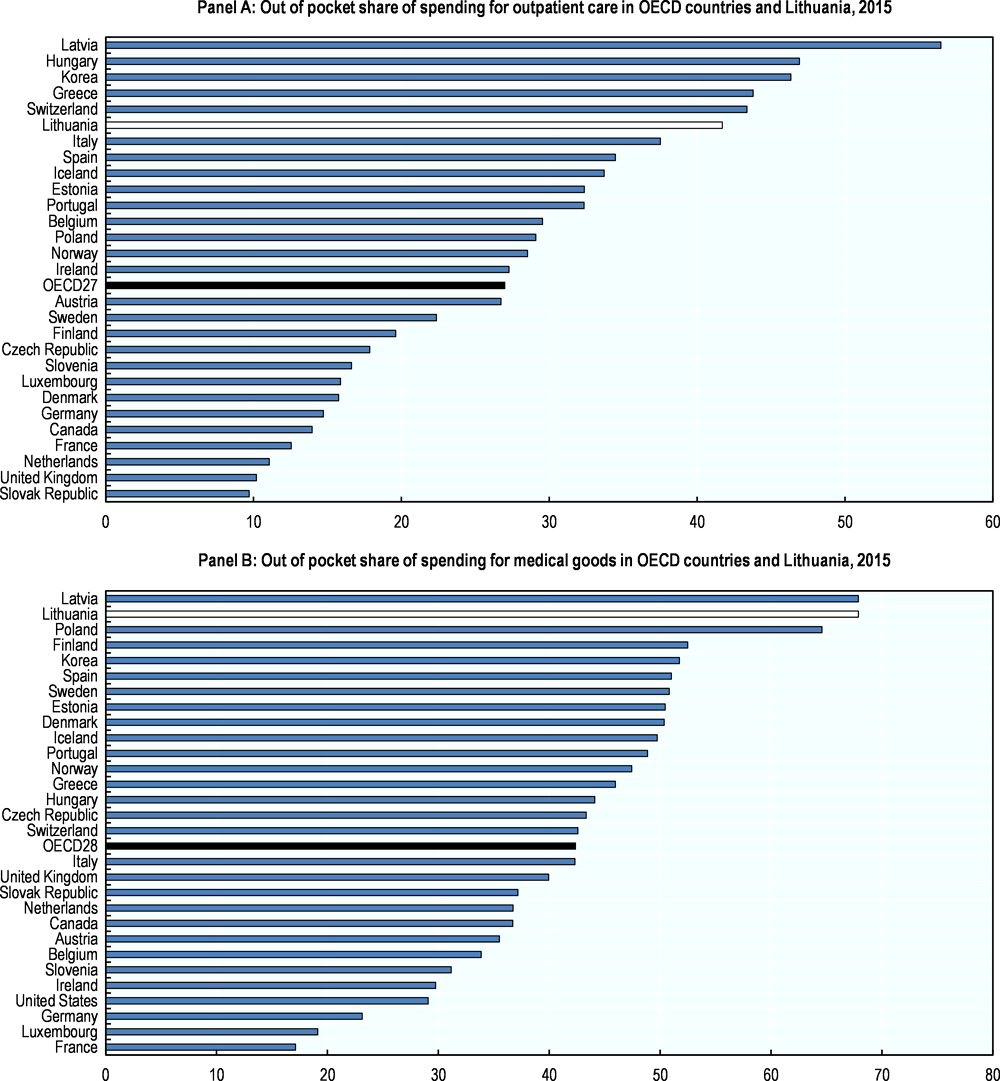

Figure 2.5. Out-of-pocket payments are high in Lithuania

Coverage is particularly low for medicines in Lithuania. The proportion of the cost which patients have to pay out-of-pocket varies considerably across types of care. For inpatient care, the proportion is only 6.1%, almost equal to the OECD average. On the other hand, OOP for ambulatory care is over 40%, when the OECD average is around 27%. When it comes to medical goods, which mostly consist of medicines, the patients have to bear 68% of the cost, which is considerable (for further details on pharmaceuticals, see Section 2.3).

Out-of-pocket spending has a significant impoverishing effect on part of the population. WHO suggests that the risk of impoverishment from OOP costs becomes significant in countries where these represent more than 20% of total spending. A WHO report on Lithuania reviewed the impact of OOP on poverty (Murauskienė and Thomson, 2018). It showed that in 2012 (most recent year for which data is available) 9.4% of the population experienced financial hardship due to health spending, a reduction from the 2008 level of 11.5% but higher than in 2005 (7%). The incidence of catastrophic spending is heavily concentrated among older people (those aged 60 and over) and couples without children. Eighty percent of catastrophic spending is due to medicines, and this proportion is even higher among households belonging to the lowest income quintile.

Financial protection is a significant cause of concern, to which the government has drawn a lot of policy attention since 2016. It has been recognised that the current pharmaceuticals pricing methods is more geared towards protecting the budget of the NHIF than ensuring financial protection for patients. Several measures intended to reduce user charges on prescription medicines were implemented in 2017 and 2018 and are discussed in detail in Section 2.3. Moreover, in 2017, the VAT on prescription medicines for which the retail price exceeds 300 EUR was reduced from 21% to 5%. In 2017 the government also adopted guidelines for pharmaceutical market policy, which included a call to develop a separate model for the reimbursement of medicines for low-income patients (Ministry of Health, Lithuania, 2017).

Figure 2.6. Coverage is particularly low for outpatient care and medical goods

Informal payments were widespread in Lithuania but recent data suggest they might be declining

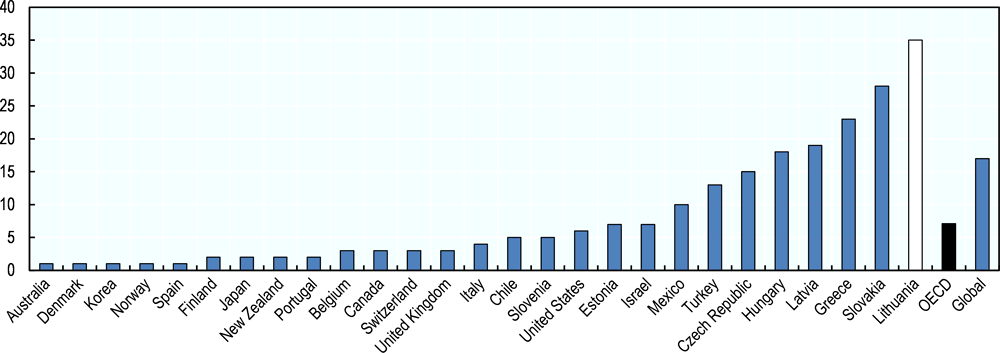

Informal payments seem to have been more widespread in Lithuania than in comparable countries. A 2013 Transparency International report, based on a survey implemented in a range of countries, inquired whether people had paid a bribe when accessing services. In Lithuania, 35% declared having done so, by far the highest proportion in the OECD (Figure 2.7). These results echoed those of the 2010 Life-in-Transition survey which reported results for eight countries of Eastern Europe which are currently OECD members. Among these countries, Lithuanians were by far the most likely to report having paid an informal payment when using the health care system: 40% of them did so, followed by Hungarians (34). The rates were below 20% in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Latvia, Estonia and Poland, with only 3% of Slovenians reporting having paid informal payments (Habibov and Cheung, 2017). In other words, Lithuania five years ago appeared to have had more of a problem than comparable countries.

Figure 2.7. In 2013, more than a third of patients declared having paid a bribe

Source: TI (2013), Global Corruption Barometer Report and Data, http://www.transparency.org/gcb2013.

In 2015, the Ministry of Health put a strategy in place to tackle informal payments, which is currently under implementation. A first set of actions is directed at the patients, primarily to ensure they are informed about the services they are entitled to and possible fees they may be officially required to pay. Institutions must post this information in areas where patients are likely to notice them (reception areas, wards, etc.). Patients are also encouraged to report instances when they believe they were unduly asked for payments and they can do so anonymously though a hotline open around the clock. Institutions have to periodically train staff, identify areas of services where the risks of informal payments are high, and put in place mitigation strategies. The Ministry has also created a corruption index for health institutions, which can translate into a “transparent institution label” being granted to facilities and is also meant to be factored in to compute the performance component of salaries of key managerial staff in public institutions.

Recent data suggest that informal payments are decreasing. Indeed, in the most recent wave of the Transparency International survey published in 2016, 24% of Lithuanian reported a bribe when they used the health service in the past year (against 35% in 2013). The most recent Eurobarometer on corruption also points to a decreasing trend. In 2017, only 12% of people who had been in contact with the system in the previous year declared having made a non-official fee or gift to the doctor, nurse or hospital, when in 2013 the proportion was 21%. While these 2017 numbers are encouraging, and lower than in Romania (19%) and Hungary (17%), in 20 countries of the EU, fewer than 5% declare having made such payments (European Commission 2017).

2.2.3. By and large coverage translates into access to services for all the population

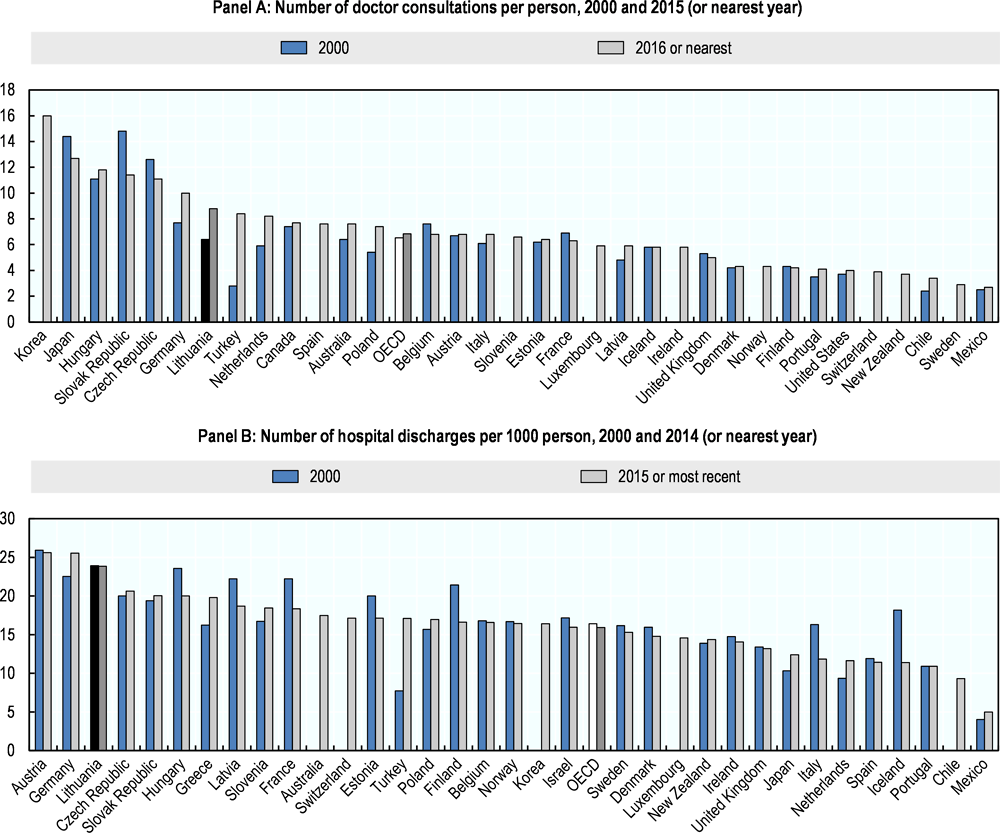

The number of contacts per population with the system are on the high side

Compared with OECD averages, people in Lithuania access health services frequently. In 2016, individuals consulted physicians on average 8.8 times a year, nearly 20% above the OECD average (Figure 2.8, Panel A). Around two thirds of these visits were to primary care physicians (NHIF data). In 2015 there was an average of 24 hospital discharges per 1000 population. This is the third highest discharge rate among OECD countries and 50% above the average (Figure 2.8, Panel B). This suggests that access to services is not constrained.

Figure 2.8. People in Lithuania access doctors and hospitals frequently

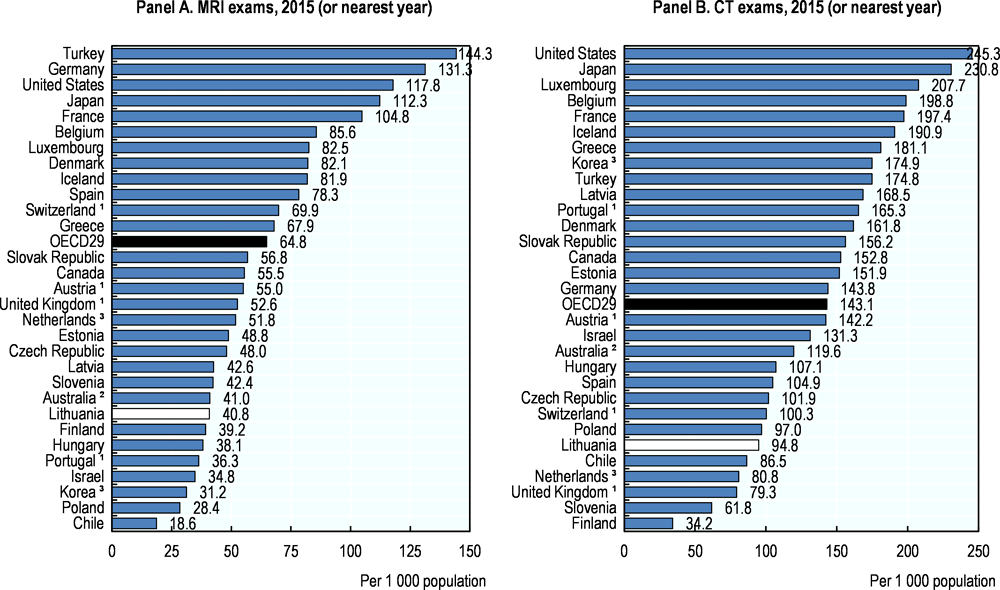

On the other hand, the number of diagnostic imaging tests provided to patients is below the OECD average. Figure 2.9 presents the number of tests per 1000 population in the OECD and Lithuania for MRIs (Panel A) and CT scans (Panel B). The levels are lower than in most OECD countries reporting data. The number of PET scans per 1000 population is 0.5, comparable to the number in Finland and a bit below Estonia (0.9) but much lower than the in other 15 OECD countries reporting data (3 PET scans per 1000 population). It is important however to keep in mind that when it comes to imaging tests, higher numbers do not necessarily mean better care. Medical imaging is one of the domains where often many tests are being conducted which have low value. If access is to be developed in Lithuania, every effort should be made to ensure it is embedded in best practice clinical guidelines and takes into account recommendations such as those of Choosing Wisely ®, a campaign and international movement which promotes appropriate care.

Figure 2.9. The volumes of diagnostic imaging services are on the low side

1. Exams outside hospital not included.

2. Exams on public patients not included.

3. Exams privately-funded not included.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

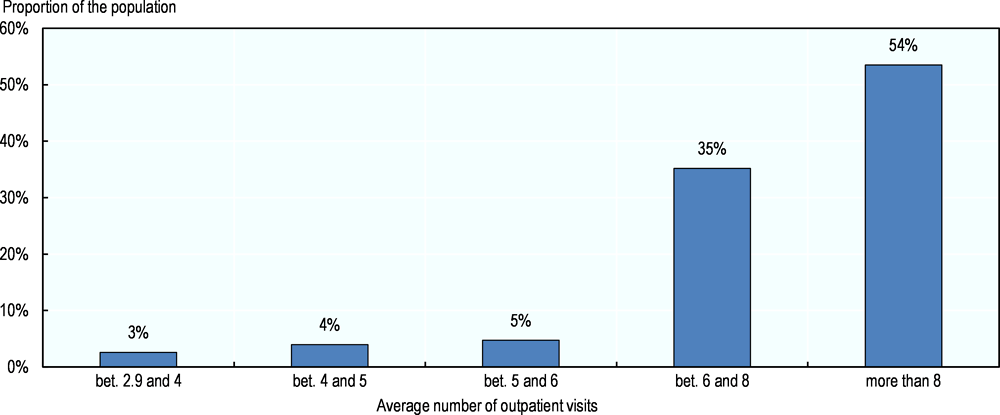

Inequalities in access are currently limited, but a minority of the population can be expected to face increasing barriers in the future. According to both administrative and survey data geographical inequalities are not stark. At least 72% of the rural population declared having seen a primary care provider in the previous year, compared with 75% of the urban population (Statistics Lithuania, 2015). Figure 2.10 is based on the average number of consultations per municipality and presents the share of the population living in the municipalities with different volumes of visits per year. Across municipalities, the number of outpatient visits per capita per year ranges from 2.9 to nearly 13 (with an average of 8.7), but 93% of the population lives in municipalities where the average number of contacts with outpatient physicians exceeds 5 per year. Around half of the remaining 7% live in municipalities adjacent to large cities, which suggest that geographic barriers to access may not be insurmountable. The rest, however, live in remote municipalities and ensuring their access to services is likely to be difficult. As the population is decreasing very rapidly in some parts of Lithuania, efforts will be needed to develop innovative solutions in this regard.

Figure 2.10. The vast majority of the population lives in areas where people see a physician at least five times per year on average

Source: NHIF data.

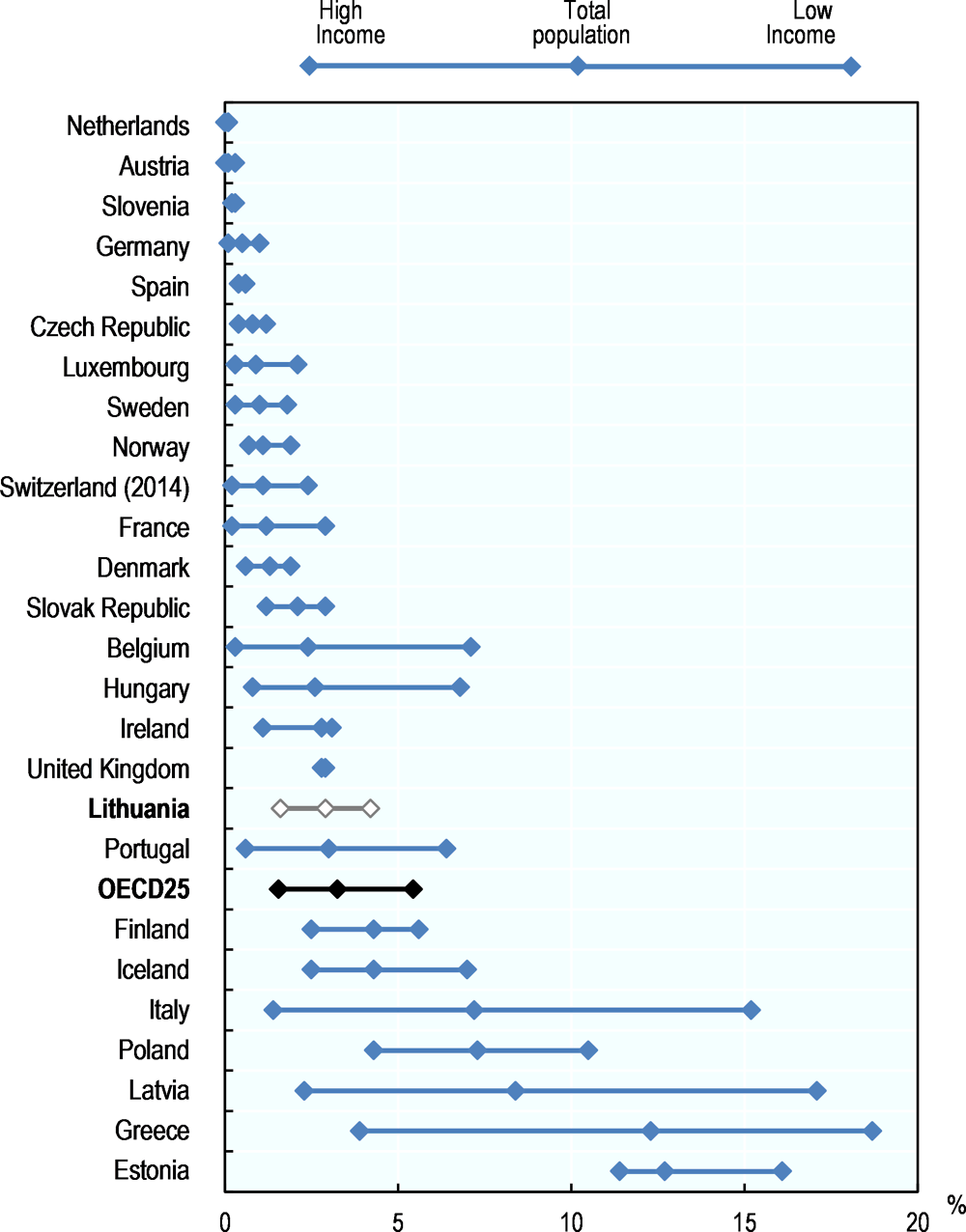

Unmet needs are lower than in comparable countries

Survey data also suggest barriers to access are limited. In the 25 EU countries of the OECD, on average, 3.2% of the population declared not having sought care for financial, geographic or waiting time reasons in 2015, compared with 2.9% in Lithuania. In addition, in most countries where the proportion of the population foregoing care exceeds 2%, individuals in low income households are much more likely than those in high income households to do so. In Lithuania, this difference is relatively small (Figure 2.11). Higher proportions of people foregoing care and/or wider inequalities can be found in many European countries, including Latvia and Estonia. The most recent wave of the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), carried it out in 2014 in Lithuania also shows that patients in Lithuania are less likely to forego or postpone care (17.5%) than in the EU overall (26.5%) and in neighbouring countries (38.8% in Estonia and 41.8% in Latvia).

Figure 2.11. Relatively few people declare unmet need for medical examinations and the spread between the rich and the poor is limited

Source: Eurostat Database, based on EU-SILC.

Few Lithuanians in particular perceive financial barriers to access. In Lithuania, only 2% of the population declared having foregone medical care for financial reasons in the 2014 EHIS (Table 2.1). The proportion foregoing dental care (which is generally considered to be more price-elastic) was 5%, but only 2% for prescribed pharmaceuticals, which is perhaps surprising given the extensive out-of-pocket payments on medicines. People in the second income quintile clearly feel the pressure on their finances more than the rest of the population, including those in the first quintile, but overall inequalities are not very pronounced. The SILC survey also point to the fact that cost is not the main reason for unmet needs.

Table 2.1. Proportion of the population for which needs were not met in the past 12 months due to financial reasons, by income quintile

|

Total |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Medical care |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Dental care |

5 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

|

Prescribed medicines |

2 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

Source: Statistics Lithuania (2015) Results of the Health Interview Survey of the Population of Lithuania 2014

Relatively speaking, waiting times are much more of a constraint to access. No administrative data on waiting times are available that would enable a comparison between Lithuania and other countries. However, three-quarters of the people in Lithuania who declare having foregone medical care do so because of waiting times (SILC 2015). This represents 2% of the population, significantly above the 1% EU28 average but nevertheless below the UK (2.5%), Finland (4.2%) and Estonia (above 11%). The NHIF and territorial insurance funds monitor and publish information about waiting times for a large range of services, by municipality, type of provider, and type of surgery. Patients can search the databases and look up services provided and timeframes in different facilities and can enquire about the waiting time in a given facility6. They can also register on waiting lists outside their regions. Additionally, for hip and knee replacement, patients awaiting surgery are given a unique number and can trace their own progress on the list. If they want to obtain the service more quickly, they can purchase their prosthesis and progress to surgery but will only be reimbursed at the time they would have received the service for free. Pensioners can also obtain a dental prosthesis and seek reimbursement later for a pre-defined amount. In 2019 a new waiting time guarantee will come into effect.

Increasing attention will need to be paid to measuring and, as needed, addressing possible barriers in access to care. While high-level analyses suggest access to care in Lithuania is reasonable, a more nuanced understanding of the situation is required. Indeed, available data are not sufficiently detailed to assess the nature and the distribution of the financial burden people face in accessing care and particularly in obtaining medicines. Little is known about the constraints faced by those living in rural areas. While summary data on waiting times are not readily available it is likely that access to care is problematic for some groups of the population and may contribute to inequalities in outcomes. Monitoring systems need to be strengthened and measures designed to address identified issues.

2.3. For pharmaceuticals, Lithuania, like many countries, struggles to balance access and sustainability

The public coverage of retail pharmaceuticals spending remains very low in Lithuania compared with OECD countries, and the government has stepped up efforts to increase the take-up of generics (3.1) and increase the transparency of its pharmaceutical policy (3.2).

2.3.1. A more effective promotion of generics would help curb out-of-pocket payments on retail drugs

Medicines used in ambulatory care are extensively funded out-of-pocket. In Lithuania, in 2015, 68% of spending on retail pharmaceuticals, which includes over-the-counter products, was paid by patients out of pocket. This is much higher than the OECD average (37%) and higher than in all OECD countries with the exception of Latvia (also 68%). The level of out-of-pocket payments for prescribed medicines in part depends on patients’ choices. The coverage rules described above foresee a payment per package (with some exceptions – see Section 2.2.1) as well as a co-payment (50, 20, 10 or 0%) based on the reference price. In addition, patients must pay the difference if the retail price of a drug is higher than the reference price, which is the case for majority of drugs in Lithuania. Since 2010 pharmacies have been required to offer at least one generic product in a group of medicines at a retail price not exceeding the reference price. Patients in fact often select non-generic drugs instead of cheaper generic alternatives, implying that some out-of-pocket payments could potentially be avoided. At the same time, the system is very complex and patients’ choices may not always be fully informed.

Several measures have been implemented to improve the uptake of generics among patient population but more needs to be done to address prescriber and pharmacy practices. Since 2010, pharmacies are obliged to inform patients about the prices of medicines and to stock the cheapest generic within a group of medicines. In 2016, NHIF also conducted a public multimedia information campaign on the benefits of generics, but to date no data are available on its impact. A degree of opposition to generics appears to be common among clinicians. Since 2011, they are required to prescribe outpatient medicines by INN (International Non-proprietary Name), with some exceptions (biological medicines and composite medicines with 3 or more substances). In inpatient setting, the Medical Advisory Committee of the health care institution in question must provide an argument justifying the use of a non-generic drug.

In 2017, the government made a commitment to step up the measures supporting the adoption of generics and the rational use of medicines. The 2017 guidelines for pharmaceutical market policy stress, among others, the need to improve monitoring of prescriptions and develop e-tools to support clinicians in optimal prescribing through the already existing e-health Services and Cooperation Infrastructure Information System (ESPBI IS). Moreover, a commitment has been made to strengthen dissemination of information to the public on the rational use of medicines and to develop a ‘Wise list of medicines’ for clinicians (following the Swedish ‘Wise List’ example and the international ‘Choosing Wisely’ initiative) (Ministry of Health, Lithuania, 2017). At present, work on an implementation plan for these measures is being carried out.

Additional financial incentives could be introduced drawing on the experience of OECD countries. A range of pay-for-performance programmes for clinicians, linking financial incentives to prescription targets for generics, exist in the OECD countries (OECD, 2017b). Furthermore, financial incentives for pharmacies to dispense cheaper products are widely used. In Lithuania, the current regulations stipulate regressive pharmacy margins, but the rate of decrease in the margins is too low to create adequate incentive.

2.3.2. Pricing methods and reimbursement decisions help curb public costs but more transparency is required.

As many OECD countries, Lithuania relies on a range of pricing mechanisms to contain costs. As discussed in Section 2.1., the reimbursement prices (reference price) of patent-protected medicines (as well as branded off-patent medicines) are set to 95% of the average over the lowest prices in each of the eight reference countries (external reference pricing). Since 2018, the reference prices are calculated on quarterly basis. When the first generic enters the market, its price is set to 50% of the originator’s price, and the second and third generic at 15% below the price of the first one7. In general, medicines are grouped by active ingredient (INN). Some therapies, i.e. insulins and asthma medications, are subject to higher-level clustering by indication, which allows for grouping drugs with different active ingredients (INN). The reimbursement price is based on the cheapest product available in the market within each cluster of medicines (internal reference pricing). Managed entry agreements are applied for all new patent protected products in the market. These pricing mechanisms are frequently used in OECD countries and all have advantages and drawbacks. Unsurprisingly, opinions differ about the overall adequacy of the pricing system among stakeholders (MoH and NHIF on the one hand, professional associations of industries on the other). A 2011 study comparing prices at 6‑9 years after the introduction of 5 generics showed reimbursed expenditure per dose had dropped between 56 and 87% (Garuoliene et al., 2011).

In 2017, the government intensified efforts to cap retail prices and reduce user charges on outpatient medicines. As discussed in Section 2.1, the retail prices of most medicines – the prices at which medicines are offered in pharmacies – have been significantly higher than their reference prices (the prices, to which the reimbursement rates apply) with patients required to cover the difference out of pocket. This has contributed markedly to high user charges. Since July 2017, regulations stipulate that the retail price of a drug cannot exceed its reference price by more than 10%. This rule applies to clusters of medicines with a least three manufacturers. If the condition is not met, the drug cannot be included in the list of reimbursed medicines (Ministry of Health, Lithuania 2017).

The government also recognises the need to improve procurement processes for inpatient medicines. The NHIF negotiates prices and procures expensive specialty inpatient medicines many of which are introduced under managed entry agreements; these generally work well and disputes with manufacturers are rare. The procurement of basic inpatient drugs occurs either at the level of the Central Procurement Institution or by individual hospitals. In the latter case, the hospitals need to prove that the prices obtained are lower than prices negotiated by the Central Procurement. Indeed, large hospitals are frequently able to negotiate lower prices, a fact that calls into question the effectiveness of the Central Procurement. As the market in Lithuania is relatively small compared to other EU Member States, the government recognizes that measures at national level are not sufficient to ensure accessibility of medicines and sustainability of the pharmaceutical care budget. As a result the 2017 guidelines for pharmaceutical market policy also include a commitment to establishing international cooperation in procurement, in particular in medicines for rare diseases (Ministry of Health, Lithuania, 2017). To further support long-term sustainability, it will also be important to recognise the need for the procurement strategies to differ across segments of the market depending on the patent status of a drug and number of substitutable patent-protected or off-patent medicines (OECD, 2017b).

Steps have been taken recently to improve the transparency of reimbursement decisions and earmark specific funds for new drugs. Decisions to include new drugs on the reimbursement list are made by the MoH, factoring in the recommendations of the Reimbursement Committee, the Compulsory Health Insurance Council and the NHIF. Since 2011, in an effort to improve access to novel drugs, the savings obtained from the pricing measures described above have been reinvested to finance access to new medicines. Most stakeholders agree that the decision process about the inclusion of new drugs lacks transparency and that prioritisation is perhaps more politically driven than evidence-based. Important steps to address this were taken in 2016, in particular: reimbursement decisions must be made within 180 days; new qualifications and experience requirements for the members of Reimbursement Committee have been imposed and decision criteria publicly reported. Moreover, the 2017 guidelines for pharmaceutical market policy envisage shortening ‘waiting times’ for moving new medicines from the so-called ‘reserve list’ to the list of reimbursed medicines, from 1 year (in 2016) to 6 months (in 2020), and to 3 months (in 2027) (Ministry of Health, Lithuania, 2017). Whether this can be achieved and the budget impact of these measures remain open questions.

Health technology assessment (HTA) capacity still needs to be strengthened. While reimbursement and pricing decision processes are structured, they remain insufficiently based on HTA. Lithuania has sought to address this problem, rather unsuccessfully, since 1993 (Wild et al., 2015). More recently (between 2013 and 2015), two organisations under the Ministry of Health were working on HTA capacity building but the results remain unclear. Efforts must be sustained to build a solid foundation for rational and transparent decisions. At the same time, given Lithuania’s size, every opportunity should be seized to take part in international collaborations in these matters. The above-mentioned guidelines for pharmaceutical market policy include further commitment to strengthening HTA capacity in the country by adapting best international practices and through international cooperation (for example, within EUnetHTA) (Ministry of Health, Lithuania, 2017).

Lithuania needs a more explicit national medicines policy. Lithuania is a rather small market in which regulations change frequently. This can undermine the industry’s business confidence and the authorities’ ability to negotiate with them and ensure sustainable availability of medicines. The development and promulgation of a comprehensive national medicines policy could help in that respect. The policy should lay out clear objectives and priorities addressing financing, individual and collective affordability, technical and allocative efficiency, and long-term sustainability. Stakeholders should contribute to its development and commit to supporting it once agreed. The guidelines for pharmaceutical market policy, adopted by the government in 2017, are a promising step in the direction of more effective policies.

Conclusion

On balance, the overall assessment of the performance of Lithuania’s health system on the key dimensions of sustainability and access is rather positive. Lithuania’s spending on health is low and efforts to keep public spending in check are effective. At the same time, the sustainability of the system is not only a matter of public finance. Improving health outcomes and the financial protection of the population is likely to require additional investments. Nevertheless, people have reasonable access to the system and unmet needs are lower than in countries with comparable income and spending. This balance – as everywhere – is a difficult one to maintain. In particular, more needs to be done to protect people from high out-of-pocket spending on pharmaceuticals and to ensure that additional funds invested in the system are geared towards improving the lagging outcomes described in chapter 1. As chapter 3 will show, efforts in particular will need to be stepped up to increase the efficiency and quality of services delivered.

References

European Commission (2015), The 2015 Ageing Report: Economic and Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Countries (2015-2060), European Economy Series, No. 3.

European Commission (2017), Corruption, Special Eurobarometer 470, October.

Garuoliene K., et al. (2011, ”European countries with small populations can obtain low prices for drugs: Lithuania as a case history.’ Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research, Vol 11, pp. 343–349.

Habibov, N, and A. Cheung (2017), “Revisiting informal payments in 29 transitional countries: The scale and socio-economic correlates”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 178, Issue C, pp. 28-37.

Kacevičius, G. and M. Karanikolos (2015). “The impact of the financial crisis on the health system and health in Lithuania” in Maresso, A. et al., eds. Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe: country experience, WHO Regional Office for Europe/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Copenhagen.

Ministry of Health, Lithuania (2017), Medicines Policy Guidelines (unofficial translation into English).

Murauskienė, L. and S. Thomson (2018), Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Lithuania, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen.

NICE – National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014) Clinical guideline [CG181] Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification, Clinical guideline [CG181], Last updated: September 2016, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2017), Lithuania: Country Health Profile 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264283473-en.

OECD (2017), Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2017-en.

OECD (2017b), Tackling Wasteful Spending on Health, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266414-en

Statistics Lithuania (2015) Results of the Health Interview Survey of the Population of Lithuania 2014 Lietuvos statistikos departamentas, Vilnius. https://osp.stat.gov.lt/services-portlet/pub-edition-file?id=20908.

Wild C, et al (2015) Background Analysis for National HTA Strategy for Lithuania. Focus on Medical Devices. Decision Support Document No. 90 ; 2015. Vienna: Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Health Technology Assessment.

Notes

← 1. Contributions for farmers, self-employed, self-insured, beneficiaries of specific pensions etc. are computed differently.

← 2. In fact, official population statistics for 2016 give a total population of 2.88 million and the number of insured registered is 2.93 million – which highlights difficulties in determining the true size of the population and thus the number of uninsured.

← 3. In 2015, the Agency in charge of collecting social contributions recovered contributions from around 94,000 insured people in Lithuania, three quarters of which were self-employed and around 13% farmers.

← 4. In Lithuania, as a general rule medicines are grouped according to International Non-proprietary Name (INN), which indicates the type of the active ingredient in the drug. A few exceptions from this rule are discussed in Section 2.3.

← 5. The eight reference countries are countries with GDP per capita comparable with Lithuania, i.e. Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia, and Romania.

← 6. In March 2017, 41 facilities were listed as providing hip-knee replacement in Lithuania. The waiting time ranged from 0 to 25 months at Vilnius University hospital. It was a year or more in 5 facilities, 3 of which in Vilnius and the other in each of the 2 main cities.

← 7. If there are four or more products with the same active substance as identified by INN (International Non-proprietary Name), the price of the most expensive product cannot exceed the price of the cheapest one by more than 40 % (reduced from 50% in 2011), Information provided by the Ministry of Health, Lithuania (2016).