This chapter is dedicated to exploring the advances in territorial and multi-level governance in Ukraine since 2014, including in regional development. It focuses on the current decentralisation reform, situating it within the context of Ukrainian governance practices, and presents the government’s approach to its implementation. It identifies areas where multi-level governance practices could be strengthened to better ensure reform sustainability, including enhanced co-ordination mechanisms. Since voluntary municipal mergers are a fundamental component of the reform, the chapter explores the strengths and weaknesses of the Ukrainian model and identifies lessons thus far. The chapter concludes with a discussion of Ukraine’s evolving approach to regional development.

Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine

Chapter 2. Advances in territorial and multi-level governance reform in Ukraine since 2014

Abstract

Introduction

In 2013, Ukraine was confronted by a series of interrelated challenges at the territorial level, including regional disparities/inequalities; significant shifts in productivity; high unemployment and informal employment; demographic change; poor quality services; and a top-down, centralised, multi-level governance structure that remains rooted in pre‑independence practices. At the time, the OECD recommended a phased approach to decentralisation. It stressed first the need for territorial reform at the local level in order to build municipal capacity, and then for a move toward decentralisation. A number of these challenges remain, as analysed in Chapter 1, particularly interregional disparities. Most critical to decentralisation reform are the ongoing challenges, identified in 2014, of administrative fragmentation compounding disparities in access to basic services, and high levels of fiscal, policy, legal and regulatory uncertainty, combined with a lack of predictability of public institutions (OECD, 2014a). In addition to these one can add missed growth opportunities resulting from the lack of a clearly articulated, place-based regional development policy.

In 2014, Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers adopted the Concept Framework of Reform of Local Self-Government and the Territorial Organisation of Power in Ukraine. This launched a multi-level governance reform based on a far-reaching political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation process. Since then, Ukraine has made great strides in modernising its approach to territorial governance: the Concept Framework outlines a strategy for boosting democratic governance at the subnational levels through broad‑based decentralisation; voluntary municipal mergers launched in 2015 are rapidly addressing problems of administrative fragmentation at the municipal level; and a place-based approach to regional policy is evolving in a practical fashion. Local leaders and citizens are starting to notice a positive change in the administrative and service capacities in their municipalities. All of this contributes to strengthening Ukraine’s development, improving quality of life and well-being, and building a more resilient state. Nevertheless, the reform process faces obstacles to its further development and challenges to its implementation which should be addressed.

This chapter is based on information collected through stakeholder meetings, fact-finding missions and OECD seminars held in Ukraine between December 2016 and July 2017,1 as well as publicly accessible literature and data. It provides an update on the advances made in territorial organisation and multi-level governance since 2014.

Building a more resilient state by advancing towards decentralisation reform

In 2014, the OECD commented on the apparently strong demand in Ukraine for a reform of the state in a decentralised manner (OECD, 2014a). Ukraine’s multi-level governance reform and decentralisation strategy is detailed in the Concept Framework of Reform of Local Self-Government and the Territorial Organisation of Power in Ukraine (Concept Framework) of April 2014, and it extends to all three areas of decentralisation: political, administrative and fiscal. The approach is comprehensive and theoretically strong, set up to lead the country towards the modernisation and reform results it wishes to achieve.

If successful, these reforms could also help enhance Ukraine’s state resilience (i.e. its ability to absorb shocks and adapt to changing circumstances without losing the ability to fulfil its basic functions (Brinkerhoff, 2011; Grävingholt and von Haldenwang, 2017; Grävingholt, 2017). By transferring responsibilities, resources and decision-making authority to intermediate or local levels of government, decentralisation and local governance reforms are directly related to the areas of legitimate and inclusive politics, revenue generation, and service provision. Economic development has been associated with such reforms for a long time.

It is undeniable that since its independence Ukraine has suffered significant economic, civic and political shocks: an economic rollercoaster starting with the breakup of the Soviet Union and from which, arguably, Ukraine is only now beginning to recover; civic instability beginning with the Russian Federation’s annexation of Crimea and the occupation of parts of Eastern Ukraine; and a lack of political stability – evidenced by 15 governments since 19922 – that has affected the state’s ability to consolidate and implement sustainable policies that can win electoral support. These shocks highlight the state’s need to improve its resilience. For this to happen, however, it will also need to make improvements in the three areas that contribute to a better functioning state: 1) authority – the state’s ability to preserve a monopoly of force; 2) capacity – the state’s ability to provide basic services and administration for its people; 3) legitimacy – the state’s ability to ensure that its claim on defining and implementing binding rules is widely accepted.

To date, Ukraine’s score card with respect to the three dimensions of statehood is moderate at best. Criminal violence has declined since 2013, but the conflict in the east poses a long-term challenge to the state’s authority. Ukraine’s ability to deliver services is in the middle range according to the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Index (HDI), which has not seen the same level of growth as such regional peers as Georgia and Poland (UNDP, 2017). At a local level, Ukraine’s regional capital cities score an average of 3 (where 5 is the highest possible score and 1 is the lowest) when residents are asked to rate the quality of 22 different public goods and services in their city (Center for Insights in Survey Research, 2017).3 In general, the state capacity to provide basic public and administrative services is weak. There are also signs pointing to weaknesses in legitimacy. Two popular upheavals in a ten-year period (2004 and 2013), leading to changes in government signal difficulty in ensuring support for government policy and action. In addition, perceptions of corruption are high, and can erode trust in government institutions. This was heard repeatedly during OECD interviews, supported by recent findings in Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer Survey (2017), and illustrated as well by Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, where Ukraine ranked 131 out of 176 countries (scoring 29 out of 100 possible points)4 in 2016, placing it together with Iran, Kazakhstan, Nepal and the Russian Federation also ranking 131. At the local level, more than 60% of residents surveyed in 24 regional capital cities considered corruption a problem in their city (Center for Insights in Survey Research, 2017). A well-functioning state combines both administrative competences with a constructive relationship between the state (government) and society; this relationship is at the core of state resilience (Box 2.1).

Improving the state/society relationship is an important step toward building Ukraine’s resilience. Decentralisation can contribute significantly to strengthening the legitimacy and inclusivity of politics, but it must be accompanied by other legitimacy-enhancing tools, including citizen ability to hold government – local, regional and national – accountable. A well-designed and implemented decentralisation process is more likely to engender democratic governance, transparency and accountability by leaders, particularly at the local level, which can then contribute to better framework conditions for reform success. There are, however, a number of conditions and practices for effective decentralisation, identified by the OECD as a result of its territorial work (Box 2.2), that are not sufficiently present in the government’s reform programme. Unless these are in place to a greater extent, successful decentralisation reform, and the benefits it brings for state resilience, will be harder to realise.

Box 2.1. Five pillars of a resilient state

An international dialogue process including fragile and conflict-affected states as well as the OECD identified five specific pillars of state/society engagement that are particularly important to achieving resilient statehood, calling these “Peacebuilding and State-building Goals”:

legitimate politics based on inclusive political settlements and conflict resolution

people’s security and the ability of the state to establish and strengthen it

access to justice and ensuring everyone fair and equal access

economic foundations for generating employment and improved livelihoods

building capacity for revenue management and accountable and fair service delivery.

Sources: OECD (2011a), Supporting State-building in Situations of Conflict and Fragility: Policy Guidance, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264074989-en; International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding (n.d.), “A new deal for engagement in fragile states”, https://www.pbsbdialogue.org/media/filer_public/07/69/07692de0-3557-494e-918e-18df00e9ef73/the_new_deal.pdf.

Many of the challenges confronting the successful implementation of Ukraine’s decentralisation process stem from the limited extent to which these principles are practiced. This is particularly true with respect to the clear assignment of responsibilities and functions across levels of government, an alignment of responsibilities and revenues, the capacity of local authorities to meet devolved responsibilities, and co-ordination mechanisms.

This chapter elaborates on Ukraine’s position with respect to these conditions and to the multi-level governance reforms underway, particularly decentralisation. It begins by putting Ukraine’s reform process in the broader context of governance challenges and the need to ensure a more enabling governance environment to solidify reform success. It then describes Ukraine’s frameworks for subnational reform and the challenges they face, and identifies several areas in multi-level governance that require additional attention. It also takes a closer look at Ukraine’s reform implementation process, as well as how advances made in regional development support and are supported by greater decentralisation. This chapter aims to provide insight into mechanisms and approaches that could help maintain reform momentum and help Ukraine meet its decentralisation goals. To this effect, each section ends by offering a series of policy recommendations for consideration by Ukraine’s policy makers as they move forward with decentralisation reform.

Box 2.2. Ten guidelines for effective decentralisation in support of regional and local development

Through its work on regional and local development, the OECD has created a set of guidelines to support more effective decentralisation when undertaken to strengthen regional and local development. While the ideal is to have all of these dimensions in place before undergoing a decentralisation process, this is difficult to achieve in practice. Therefore, in order to maximise the possibility of success, governments should assess which areas may be weak and take steps to address these, while also reinforcing those areas that are already strong. Successful decentralisation will depend on the presence of these factors.

Clarify the sector responsibilities assigned to each level of government. Most responsibilities are shared across levels of government, and spending responsibilities overlap in many policy areas. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure adequate clarity on the role of each level of government in the different policy areas in order to avoid duplication, waste and loss of accountability.

Clarify the functions assigned to each level of government. Clarity in the different functions that are assigned within specific policy areas – e.g. strategic planning, financing, regulating, implementing or monitoring – is as important or even more so than clarity in assignment of tasks.

Ensure coherence in the degree of decentralisation across sectors. A degree of balance or coherence in the level of decentralisation (i.e. what is decentralised and how much it is decentralised) should be ensured across policy sectors. In other words, decentralising one sector but not another can limit the ability to exploit cross-sector complementarities and integrated policy packages when implementing regional and local development policy. While decentralisation may apply differently to different sectors, there should be coherence and complementarity in the approach.

Align responsibilities and revenues, and enhance subnational fiscal autonomy. The allocation of resources should be matched to the assignment of responsibilities to subnational governments. Unfunded mandates or a mismatch between responsibility and financing capacity should be avoided.

Actively support capacity building for subnational governments with resources from the national government. Additional financial resources need to be complemented with the human resources capable of managing them. This dimension is too often underestimated, if not completely forgotten, in decentralisation reform, and is particularly important in poor or very small municipalities. At the very least, subnational governments should have the responsibility and be able to monitor employee numbers, costs and competencies.

Build adequate co-ordination mechanisms across levels of government. Since most responsibilities are shared, it is crucial to establish governance mechanisms to manage these joint responsibilities. Creating a culture of co-operation and regular communication is crucial for effective multi-level governance and long-term reform success. Tools for vertical co-ordination include dialogue platforms, fiscal councils, standing commissions, and intergovernmental consultation boards and contractual arrangements.

Support cross-jurisdictional co-operation through specific incentives. Subnational horizontal co-ordination is essential to encourage investment in areas where there are positive spillovers, to increase efficiency through economies of scale, and to enhance synergies among policies of neighbouring jurisdictions. Intergovernmental bodies for horizontal co‑ordination can be used to manage responsibilities that cut across municipal and regional borders. Determining optimal sub-central unit size is a context-specific task; it varies not only by country or region, but also by policy area – efficiency size will differ based on what is under consideration, for example waste disposal, schools or hospitals.

Allow for pilot experiences and asymmetric arrangements. Allow for the possibility of asymmetric decentralisation, i.e. giving differentiated sets of responsibilities to different types of regions/cities/local governments, based on population size, rural/urban classification and fiscal capacity criteria. Ensure implementation flexibility, making room for experimenting with pilot programmes in specific places or regions and constantly adjusting through learning-by-doing.

Make room for complementary reforms. Effective decentralisation requires complementary reforms at the national and subnational levels in the governance of land use, subnational public employment, regulatory frameworks, etc.

Improve transparency, enhance data collection and strengthen performance monitoring. Data collection should be undertaken to monitor the effectiveness of subnational public service delivery and investments. Most countries need to develop effective monitoring systems of subnational spending and outcomes.

Source: Allain-Dupré, D. (forthcoming), “Assigning responsibilities across levels of government: Challenges and guiding principles”, forthcoming.

Situating decentralisation reform in the Ukrainian governance context

Decentralisation reform is ultimately a political choice and thus should be pursued as part of a larger political reform process, including, for example, reforms of the judiciary, civil service and regulatory frameworks, while also building greater accountability and a broad reform coalition. If pursued in isolation from other reforms, decentralisation in Ukraine could exacerbate existing problems of corruption and clientelism (OECD, 2017a). If Ukraine’s objective is to build productivity, prosperity and citizen well-being across its territory using decentralisation reform and regional development policy as vehicles, it will need to ensure a more stable reform environment.

Decentralisation is frequently undertaken in an effort to improve or strengthen democratic governance. Some shifts at the local level can be seen, particularly as noted earlier that average approval ratings for mayors and municipal councils is rising, at least in regional capital cities. Decentralisation can certainly contribute to strengthening the legitimacy and inclusivity of politics but it must be accompanied by other legitimacy-enhancing tools, such as integrity among public officials, local level civic activism and engagement, and an ability for citizens to hold government – local, regional and national – accountable. Ensuring an enabling environment for decentralisation can mean taking a stronger approach to addressing institutional impediments to reform, including corruption. Unless this is managed more effectively, decentralisation reform will be at risk.

Taking stock of government effectiveness and the control of corruption

Overcoming resistance to decentralisation can be difficult. This may be particularly true in Ukraine, where vested interests are part of a larger problem of effective public governance. This is highlighted by the World Governance Indicators. Out of six categories of composite indicators for public governance, Ukraine’s governance score between 2006 and 2016 is consistently in the negative range, with the exception of voice and accountability. Although there were some positive shifts between 2014 and 2016, since 2006 there has been no significant improvement in the percentile rankings (Table 2.1).

Government effectiveness has dropped in the last decade

While the dramatic drop in the political stability category is to be expected, the fact that Ukraine’s percentile rank has not improved very much over the past ten years is worrying and can reflect structural challenges in the public governance system, as well as difficulties implement lasting reform. With respect to decentralisation reform, Ukraine’s performance is especially troublesome in the areas of government effectiveness (Table 2.2) and control of corruption.

Government effectiveness captures the perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies (Kraay, Kaufmann and Mastruzzi, 2010). The fact that these remain low in Ukraine even after reform is noteworthy. While Ukraine has been reforming under exceptionally difficult circumstances, the fact that its neighbours have improved government effectiveness overall by a minimum of five points raises the question of where things have broken down. There is hope that decentralisation reform with time can start to reverse this trend, but for this to happen the framework conditions must be more supportive of reform.

Table 2.1. Worldwide Governance Indicators: Ukraine and its neighbours

A. Governance score (-2.50 to 2.50 scale)

|

Ukraine |

Belarus |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Poland |

Russian Federation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2006 |

2014 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

|

|

Voice and accountability |

0.05 |

-0.14 |

0.02 |

-1.39 |

0.22 |

-0.03 |

0.84 |

-1.21 |

|

Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism |

-0.04 |

-2.02 |

-1.89 |

0.12 |

-0.29 |

-0.28 |

0.51 |

-0.89 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-0.49 |

-0.41 |

-0.58 |

-0.51 |

0.51 |

-0.62 |

0.69 |

-0.22 |

|

Regulatory quality |

-0.52 |

-0.63 |

-0.43 |

-0.94 |

1.01 |

-0.12 |

0.95 |

-0.42 |

|

Rule of law |

-0.80 |

-0.79 |

-0.77 |

-0.78 |

0.37 |

-0.54 |

0.68 |

-0.80 |

|

Control of corruption |

-0.75 |

-0.99 |

-0.84 |

-0.29 |

0.67 |

-0.96 |

0.75 |

-0.86 |

Note: Higher values (i.e. closer to +2.5) indicate better governance.

B. Percentile rank (0-100)

|

Ukraine |

Belarus |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Poland |

Russian Federation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2006 |

2014 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

|

|

Voice and accountability |

47.6 |

43.4 |

47.3 |

10.3 |

53.7 |

45.8 |

72.4 |

15.3 |

|

Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism |

44.0 |

5.7 |

6.2 |

50.5 |

35.2 |

36.2 |

63.3 |

16.7 |

|

Government effectiveness |

36.6 |

39.9 |

31.7 |

36.1 |

71.2 |

29.8 |

73.6 |

44.2 |

|

Regulatory quality |

31.9 |

29.3 |

36.1 |

16.4 |

81.3 |

50.5 |

79.8 |

37.0 |

|

Rule of law |

24.9 |

23.1 |

23.6 |

22.1 |

63.9 |

32.2 |

74.5 |

21.1 |

|

Control of corruption |

24.9 |

14.9 |

19.7 |

47.6 |

73.6 |

14.4 |

76.4 |

18.8 |

Note: 0 is lowest percentile rank; 100 is highest.

Sources: Kraay, A., D. Kaufmann and M. Mastruzzi (2010), “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and analytical issues”, https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5430; data for Ukraine from: World Bank (2017b), “Ukraine”, The Worldwide Governance Indicators (database, table view), http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#reports (accessed 29 October 2017).

Table 2.2. Percentile rank in government effectiveness: Ukraine and its neighbours

|

2006 |

2016 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Ukraine |

36.59 |

31.73 |

|

Belarus |

11.71 |

36.06 |

|

Georgia |

47.80 |

71.15 |

|

Moldova |

24.39 |

29.81 |

|

Poland |

65.85 |

73.56 |

|

Russian Federation |

39.02 |

44.23 |

Note: 0 is the lowest and 100 is the highest percentile rank.

Source: World Bank (2017b), “Ukraine”, The Worldwide Governance Indicators (database, table view), http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#reports (accessed 29 October 2017).

Trust is low and corruption is widely perceived

The control of corruption may be one of the most significant needs with respect to ensuring appropriate framework conditions for successful decentralisation reform in Ukraine. Corruption wastes public resources, widens economic and social inequalities, breeds discontent and political polarisation, and reduces trust in institutions. It can perpetuate inequality and poverty, impacting well-being and the distribution of income, and undermine opportunities to participate equally in social, economic and political life. At a global level, it is now reported as the number one concern by citizens, of greater concern to them than globalisation or migration (Edelman, 2017).

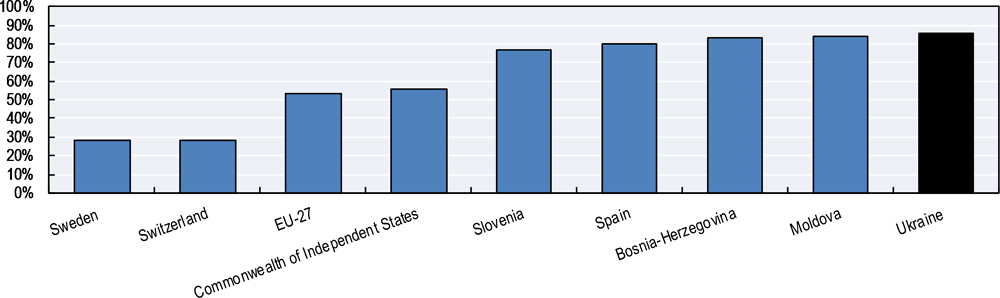

Ukraine ranks in the top five countries in Europe and Central Asia where corruption is perceived to be one of the three largest problems facing the country, indicated by 56% of people surveyed by Transparency International.5 It is preceded by Slovenia (59%), Spain (66%) and Moldova (67%), and followed by Bosnia-Herzegovina (55%) and Lithuania (54%) (Transparency International, 2016b). Overall, the perception of corruption in Ukraine’s government and public institutions is consistently higher than global perceptions, and sometimes significantly so (Table 2.3) (Transparency International, 2013a).

Table 2.3. Perceptions of corruption by institution, 2013

|

Institution |

Ukraine |

Global score |

|---|---|---|

|

Religious bodies |

3.0 |

2.6 |

|

Non-governmental organisations |

3.2 |

2.7 |

|

Media |

3.4 |

3.1 |

|

Military |

3.5 |

2.8 |

|

Business/private sector |

3.9 |

3.3 |

|

Education system |

4.0 |

3.1 |

|

Political parties |

4.1 |

3.8 |

|

Parliament/legislature |

4.2 |

3.6 |

|

Medical and health |

4.2 |

3.2 |

|

Public officials/civil servants |

4.3 |

3.6 |

|

Police |

4.4 |

3.7 |

|

Judiciary |

4.5 |

3.6 |

Note: Aggregated, by country; scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all corrupt and 5 means extremely corrupt.

Source: Transparency International (2013a), Global Corruption Barometer: 2013, https://www.transparency.org/gcb2013/report.

In 2013, 87% of citizens surveyed perceived the judiciary as the most corrupt institution in Ukraine, making judicial reform an urgent matter and a critical component of the overall reform process, including decentralisation (Box 2.3). The police, as well as public officials and civil servants, are also perceived as corrupt by 84% and 82% of citizens, respectively (Transparency International, 2013b).

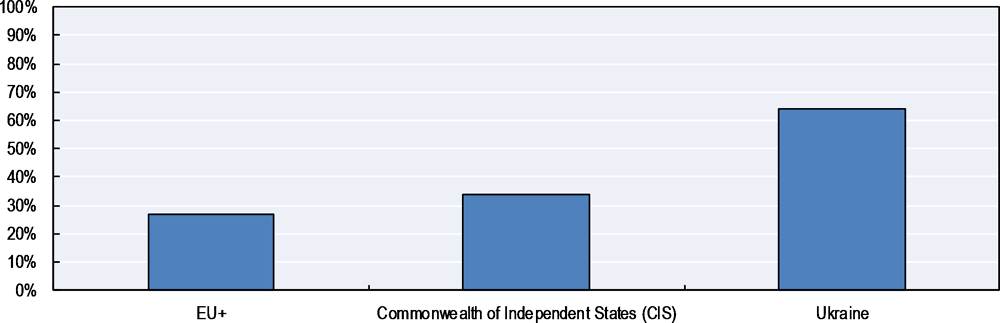

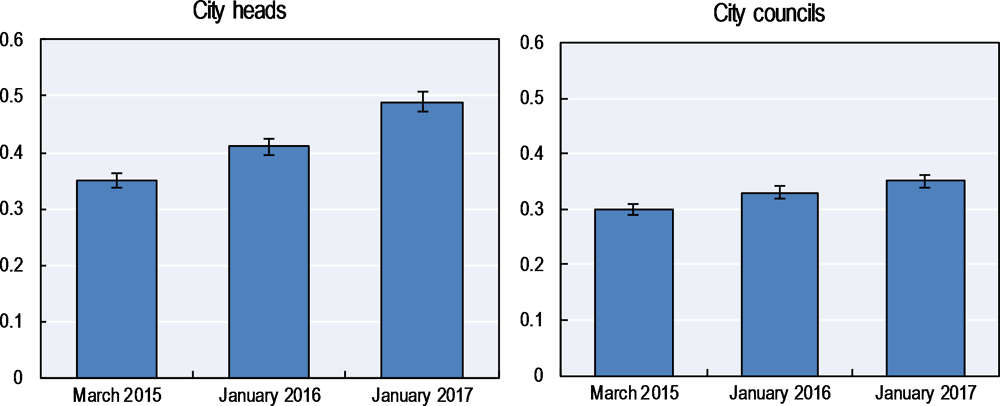

Confidence and trust in leadership is a weakness in Ukraine. This is evident in perception surveys undertaken in the 24 regional capital cities, which highlight a generally low approval rating for the work of the president, the parliament and oblast state administrations, as well as oblast councils. Mayors have slightly higher levels of approval (Center for Insights in Survey Research, 2017). In 2013, 77% of responding Ukrainians perceived that parliament was corrupt or extremely corrupt and 74% had the same perception of political parties (Transparency International, 2013a). In 2016, 64% of Ukrainians surveyed for perceived that “most” or “all” members of parliament were corrupt (Figure 2.1) (Transparency International, 2016a). These results point to the same issue: the pillars of a democratic society are perceived to be among the most corrupt institutions in Ukraine (Transparency International, 2013a).

Ukrainians have a generally low opinion of how the government handles corruption within its ranks. Among European and Central Asian countries, Ukraine registers the highest number of people who rate their government “badly” when it comes to fighting corruption in government: 86% in Ukraine. While this is similar to some EU and non-EU countries, it is significantly above EU+ and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)6 averages (Figure 2.1) At the bottom of the list are Sweden and Switzerland (Transparency International, 2016b). In other words, the government either does little to stop corruption in government administrations or its methods are not effective.

Box 2.3. The importance of judicial reform to support decentralisation progress

A basic tenet of democracy, in addition to free and fair elections, is the adherence to the rule of law – meaning that no one, including government, is above the law, where laws protect fundamental rights and justice is accessible to all. Ukrainian courts enjoy little popular trust and confidence in their work. Among residents of Ukraine’s oblast capital cities, approval ratings for the work of the courts range from a high of 30% in Ternopil to a low of 2% in Uzhgorod.

The lack of trust in the court system makes it difficult for courts and court officials to serve as effective arbiters when there are disputes, including over government powers and competences. Strengthening the political and financial independence of the judiciary and improving the standards of training and admission of judges should be a priority for the Ukrainian government. The 2014 Law on Restoring Trust in the Judicial System of Ukraine returned some power to the judiciary, for example by authorising judges in each court to elect the court’s president (previously centrally appointed); but in most courts this did not lead to a change in court leadership. While the 2014 law is a good step, more could be done to ensure that courts at all levels of government are independent and trustworthy. This includes defining objective criteria for judicial appointment and promotion, ensuring that vacant posts are filled through a competitive procedure, and that the transfer of judges within the court system – at national and subnational levels – is based on a set of objective and transparent criteria. All of these steps could help fill gaps left by the 2014 law.

Sources: Bertelsmann Stiftung (2017), “BTI 2016: Ukraine country report”, https://www.bti-project.org/fileadmin/files/BTI/Downloads/Reports/2016/pdf/BTI_2016_Ukraine.pdf; Center for Insights in Survey Research (2017), “Third Annual Ukrainian Municipal Survey”, www.iri.org/sites/default/files/ukraine_nationwide_municipal_survey_final.pdf; Grävingholt, J. (2017), “Decentralisation and resilience in Ukraine”, unpublished.

Figure 2.1. Perception of corruption among parliamentarians is high in Ukraine, 2016

Note: Percentage of respondents perceiving that “most” or “all” parliamentarians in their country are corrupt.

Source: Transparency International (2016a), “Corruption Perception Index”, https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016#table.

Figure 2.2. Fighting corruption in government

Note: Percentage of people who rate their government “badly” when it comes to fighting corruption in government. CIS: Commonwealth of Independent States.

Source: Transparency International (2016a), “Corruption Perception Index”, https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016#table.

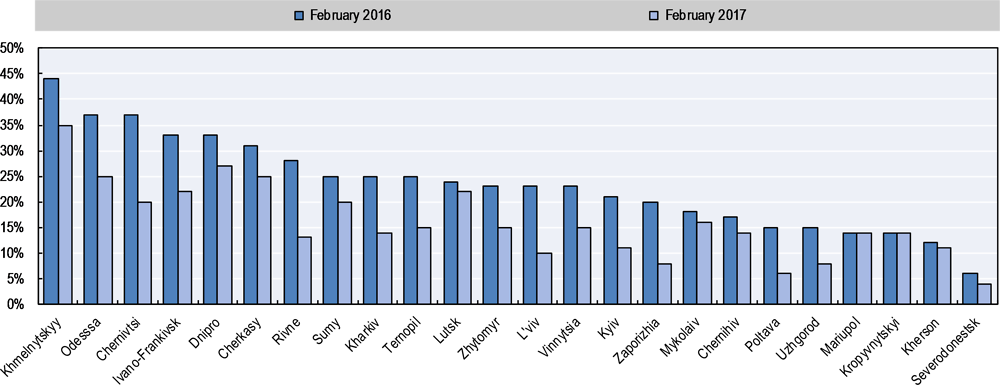

These perceptions are consistent in surveys focused on local government as well. Between 2016 and 2017, the percentage of citizens in Ukraine’s regional capital cities who think their mayors make an effort to end corruption at the municipal authority level generally dropped (Figure 2.3) (Center for Insights in Survey Research, 2017).

Figure 2.3. Citizen perception of mayoral efforts to end corruption

Note: “Yes” responses to the question: “Do you think that your mayor is making an effort to end corruption at the municipal authority level?”

Source: Center for Insights in Survey Research (2017), “Third Annual Ukrainian Municipal Survey”, www.iri.org/sites/default/files/ukraine_nationwide_municipal_survey_final.pdf.

Equally worrisome is that citizens report feeling powerless to address corruption themselves. When asked “To what extent do you agree that ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption”,7 72% of respondents felt that citizens could not do much to prevent or stop it (Transparency International, 2013b). When questioned about the measures that might be the most effective in decreasing corruption in their city, out of 11 possible options the highest levels of responses were:

“Simplifying to the greatest possible extent the process for issuing permits, references, etc.”

“Nothing will help because municipal authorities are powerless, as anti-corruption efforts fully depend on central authorities.”

“Obligatory and periodic public accountability of municipal and law enforcement authorities for anti-corruption efforts.” (Center for Insights in Survey Research, 2017)

Moving forward in minimising the impact of public governance challenges

Weak public governance practices contribute to an unstable environment for achieving reform objectives. Without an enabling environment, supported by good governance practices, and a public sector – including a centre of government – that is capable of ensuring these, outcomes in regional development, service delivery, public and private investment, and the protection of property rights, for example, will be weakened rather than strengthened (World Bank, 2017b), and reform objectives will be left unattained.

Creating such an environment will mean more actively addressing the vested interests and better controlling the corruption that hold back government effectiveness – and through this hold back reform. It also means ensuring that integrity and trust become cornerstones of public institutions and services (Transparency International, 2013a). For this to happen, rule of law and judicial reform must be strengthened. It will also require improving transparency and establishing accountability and integrity frameworks, among other things.

Ensuring integrity in the public sector is fundamental to Ukraine’s success, as it can promote greater public confidence and trust in government. It can also support successful decentralisation reform. In the current context of decentralisation, subnational governments are particularly exposed to areas associated with a high risk of corruption, such as pubic procurement and public infrastructure projects. In addition, they are vulnerable to policy capture, where public decisions over policies are directed away from the public interests towards a special interest, thereby exacerbating inequalities, and undermining democratic values, economic growth and trust in government (OECD, n.d.). Democratic processes need to be reviewed, including disclosure laws and codes of conduct for political officials and civil servants, with enforceable sanctions if necessary.

A cultural shift in the attitude of citizens is also necessary, particularly if citizens are to hold government to account for its actions. While in Western European countries citizens are more likely to think it is socially acceptable to report a case of corruption, this is not necessarily the case in Ukraine (or in other European countries, such Croatia, Hungary or Lithuania) (Transparency International, 2016b). When organised, people can exert significant influence through their voting and spending patterns; but they also are likely to need more formal mechanisms (e.g. whistle-blower laws) and encouragement to come forward and report cases of corruption and bribery at all levels of government and in the private sector.

Box 2.4. Recommendations to strengthen public governance frameworks

To strengthen public governance frameworks that otherwise can undermine decentralisation reform, it is recommended to focus on addressing issues of government effectiveness and anti-corruption, including by:

establishing integrity and accountability frameworks

reviewing democratic processes, including disclosure laws, and codes of conduct for political officials and civil servants

introducing formal mechanisms and a sense of “safety” to encourage people to come forward and report cases of corruption and bribery.

Ensuring a balanced approach to territorial reform

Ukraine is a unitary country with three levels of constitutionally guaranteed subnational government (Table 2.4). It is comprised of oblast (regions – TL2), which are subdivided into rayon (districts) and further into hromada (local self-government units that range from cities to villages and rural hamlets). Within these levels there is a degree of definitional overlap: some cities, for example those of oblast subordination, are on equal footing as the district level – the rayon – and among the hromada there are cities, towns, villages and settlements with local councils. There are also settlements (generally rural) with no local councils.

Table 2.4. Subnational government structure in Ukraine: A simplified perspective prior to reform, up to 20151

|

Level of territorial unit |

Name of territorial unit |

Number |

Other territorial entities at the same level |

Number of other entities |

Total number of entities at territorial level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Regional |

Oblast |

24 |

Autonomous Republic of Crimea Capital city of Kyiv City of Sevastopol |

3 |

27 |

|

Intermediary (district) |

Rayon |

490 |

Cities of oblast subordination |

187 |

6772 |

|

Local self-government |

Hromada |

11 5203 |

1. Since 2015 there have been a series of municipal amalgamations, which has reduced the total number of hromada by more than 2 000.

2. This does not include the 108 urban districts that act as administrative divisions in Ukraine’s largest cities.

3. Hromada include cities of rayon significance, towns, and rural settlements and villages having councils. If one includes settlements without councils, there are a total of 29 533 local self-government units (271 cities of rayon significance, 885 townships [Ukrainian Селища міського типу or CMT ] and 28 377 rural units).

Sources: Adapted from OECD (2014a), OECD Territorial Reviews: Ukraine 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204836-en originally in Coulibaly, S. et al. (2012), Eurasian Cities: New Realities along the Silk Road, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11877; Nehoda, V. (2014), “Concept of the reform of local self-government and territorial organisation of power”.

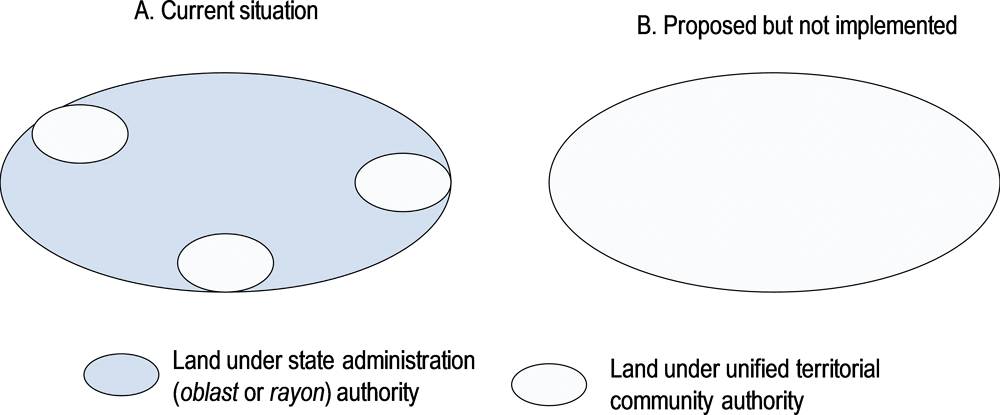

Administrative structures at the oblast and rayon level are deconcentrated, representing the central government, and are responsible to a presidentially appointed oblast governor. Popularly elected councils at the oblast and rayon levels are dependent on their associated oblast or rayon executive committee for the implementation of council priorities in terms of policy and programming. The oblast and rayon function more actively in a deconcentrated rather than a decentralised manner; in other words, these subnational entities act as “branches” of the central government (e.g. subnational offices of a ministry) rather having full responsibility for delegated fiscal and administrative functions, and being popularly elected. Meanwhile, at the hromada level, leaders and councils are popularly elected, but as administrative entities they have traditionally depended on their rayon administration for resources. The result is restricted subnational autonomy (e.g. to identify and execute community priorities) and limited responsibility and capacity for management, administration and service delivery.

The Concept Framework of Reform of Local Self Government: Proposals and limitations

The Concept Framework takes a “whole-of-system” approach to reform. It introduces change at all three levels of subnational government and proposes to restructure the country’s multi-level governance dynamic (Cabinet of Ministers, 2014a). Its strength lies in its proposal for broad political, administrative and territorial restructuring, including by:

altering the political power structures at the oblast (region) and rayon (district) government levels to make room for stronger democratic governance

differentiating mandates and supporting decentralised administration and service delivery by hromada

simplifying the territorial administrative structure into subnational tiers into three main categories with only one category of local self-government unit (Annex 2.A)

clarifying and adjusting the responsibilities assigned to each level of government (Annex 2.B).

The constitutional amendment required to implement the reform package as proposed by the Concept Framework – adjusting territorial structures (e.g. reducing the number of rayon administrations), redefining territorial administrative powers (e.g. normatively establishing more empowered local self-governments), clarifying the attribution of responsibilities and establishing a prefect-based system for deconcentrated state administration – has stalled since 2015. This delay has resulted in significant challenges to reform implementation and affects the reform’s stability over the medium and long term. It also affects the sustainability of achievements to date, as the gains made at the local level in terms of structures, finance and responsibilities are not constitutionally entrenched.

The inability to fully implement the Concept Framework has not stopped the government from advancing territorial and administrative reform. However, it has meant abandoning a “whole-of-system” approach, where change would extend to all three levels of subnational government in a balanced manner. Instead, the reform process has emphasised local self-government. The aim is entirely logical: to build scale at the territorial level in order to ensure that local governments have sufficient capacity to assume devolved responsibilities. The impact, however, has been to generate a disequilibrium between the district and local levels that can undermine reform. It also has meant using decentralisation as an incentive for territorial reform, rather than undertaking territorial reform to ensure capacity and then introduce decentralisation evenly across the territory.

Introducing decentralisation one law at a time

Between 2014 and 2016, the government introduced a trio of mutually supportive laws that paved the way for decentralisation reform by promoting municipal amalgamation, inter-municipal co-operation and greater fiscal autonomy (Box 2.5).

These three laws facilitate the implementation of Ukraine’s decentralisation reform. Their passage facilitated territorial and administrative adjustments to local self-government units in order to build scale, laying the foundation for administrative decentralisation. The changes to the State Budget Code represented a fiscal decentralisation package that encourages amalgamation by significantly enhancing revenue capacities and offering greater autonomy in expenditure decisions to communities that chose to amalgamate under Law No. 157-VIII. While fiscal decentralisation can improve the revenue capacity of local communities, the expectation was that it would also help improve tax collection compliance, the climate for business and innovation, and assist in fighting corruption. The driving logic being that as direct recipients of tax receipts, local authorities gain more by ensuring that taxes are collected and funds are appropriately used in order to encourage tax compliance, rather than by being lax in collection responsibilities and turning a blind eye to evasion. It should be noted that administrative and fiscal decentralisation benefits (i.e. additional service responsibilities, access to increased resources through the changes in the State Budget Code, and an ability to negotiate their budgets directly with the oblast administration rather than depending on transfers from the rayon state administration) reach only those communities that amalgamate.

Box 2.5. A trio of laws drives decentralisation reform

Law No. 1508-VII of 17 June 2014 on Co-operation of Territorial Communities: permits municipalities to co-operate in order to fulfil three aims: 1) to better support the social, economic and cultural development of their territories; 2) to more efficiently carry out their responsibilities; 3) to enhance the quality of services provided. Co-operation can, legally, be structured in one of five ways:

delegation of one or more tasks from one entity to another with the transfer of resources to perform the task

co-ordinated implementation of joint projects between entities with common resources accumulated for the duration of the project

co-financing of enterprises, institutions, communal entities or infrastructure facilities destined to provide the service

creation of joint communal enterprises, institutions and organisations, as well as common infrastructure facilities

establishment of a joint management body for the joint execution of authority.

Law No. 157-VIII of 5 February 2015 on Voluntary Consolidation of Territorial Communities:1 established the capacity for small cities, villages and rural communities to amalgamate. The objective being to build scale at the local level in order to provide higher quality and more affordable public services, and improve capacity to meet new fiscal and administrative responsibilities.

Changes to the State Budget Code realised in the 2016 state budget facilitated revenue generation at the local level and budget negotiations directly with oblast administrations for communities that amalgamated, forming a solid incentive structure for local territorial reform.

1. Commonly referred to as the Law on Amalgamation or the Amalgamation Law.

Sources: Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (2014a), Law No. 1508-VII of 17 June 2014 on Co-operation of Territorial Communities, http://zakon0.rada.gov.ua/laws/anot/en/1508-18; Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (2015a), Law No. 157-VIII of 5 February 2015 on Voluntary Consolidation of Territorial Communities, in Ukrainian at: http://zakon3.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/15719/print1469801433948575; OECD interviews.

As these laws have gained momentum and generated change, they have been followed by proposed amendments as well as other laws intended to further the decentralisation process. For example, while initially communities could not amalgamate across rayon boundaries, with the Law on Introducing Amendments to Certain Ukrainian Legislation Concerning the Peculiarities of Voluntary Consolidation of Territorial Communities Located on Territories Adjacent to Rayon8 passed in April 2017 (Association of Ukrainian Cities, 2017), this is now possible – helping bring together communities that have economic, cultural or historical ties.

This legislative-driven approach was initially powerful enough to provoke significant change in Ukraine’s subnational administrative landscape. It, however, may be difficult to maintain as a long-term approach for reform implementation. While draft laws that could strengthen the territorial and decentralisation reform processes are frequently proposed in the Verkhovna Rada (national parliament), their rate of approval and passage is not commensurate with their rate of introduction. This becomes evident when looking at parliamentary and stakeholder websites that keep track of the process, including in the areas of land management, the categories of communities that can amalgamate, and local power structures (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 2017a; Ministry of Regional Development, 2017c; Association of Ukrainian Cities, 2017). In addition, the government has stalled or backtracked on some of its reform efforts, particularly in the area of land-use reform, local revenue sources and support to local communities for regional development. Thus, Ukraine’s reform process is characterised by legislative/political intransigence, vested public and private interests that prevent complete reform and result in a patchwork of individual laws and actions, and an unstable reform environment. The result is a reform process that has a strong strategic and theoretical basis, but is facing challenges for full implementation.

Successful multi-level governance reform requires empowered co-ordination mechanisms

Implementing a reform as complex and far-reaching as Ukraine’s is easier when there is strong institutional co-ordination beginning at the highest levels. This includes a centre-of-government office that champions and communicates a clear vision of the reform’s distinct pieces (e.g. strategy, legislation, sector policies, financing mechanisms, government and non-government stakeholders, monitoring and evaluation, etc.) and can steward the mechanisms that ensure everything fits together; a lead co-ordinating ministry for the reform that is not only mandated, but also fully resourced, for its implementation; and effective horizontal and vertical co-ordination mechanisms to ensure that each player in the reform process is moving in the same direction. At the base of this are co-ordination mechanisms that, with time, can evolve into more co-operative, and ideally collaborative, practices (Box 2.6).

Box 2.6. Co-ordination, co-operation and collaboration

Co-ordination, co-operation and collaboration build on each other, where co-ordination forms the platform from which co-operation and then collaboration can grow.

Co-ordination: joint or shared information insured by information flows among organisations. “Co-ordination” implies a particular architecture in the relationship between organisations (i.e. centralised or peer-to-peer; direct or indirect), but not how the information is used.

Co-operation: joint intent on the part of individual organisations. “Co-operation” implies joint action but does not address the relationship among participating organisations.

Collaboration: co-operation (joint intent) together with direct peer-to-peer communication among organisations. “Collaboration” implies both joint action and a structured relationship among organisations.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2005), e-Government for Better Government, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264018341-en.

Among the challenges that Ukraine’s reform process faces are limited stewardship and co-ordination from the national level. This is compounded by limited co-operation among political, administrative and other Ukrainian institutional stakeholders to guarantee success. Ensuring effective and coherent action requires co-ordination and clear lines of responsibility as well as accountability. The multiplicity of policies, projects and programmes generated by domestic and international stakeholders is significant and there is a strong risk of overlap, sub-optimal use of resources, and limited tracking of the reform’s actual impact or effectiveness. For example, during OECD interviews, Ukrainian officials indicated that currently there is no single entity with a comprehensive list of the programmes implemented by the actors in the decentralisation field. This in turn makes it particularly difficult to determine whether the activities underway are working in harmony, and if they are supporting broader government objectives while also yielding programme-specific desired results.

The centre-of-government could play a stronger role

A clearly mandated centre-of-government body, one that can manage “day-to-day” horizontal and vertical co-ordination needs, is not evident in Ukraine’s governance structure, which affects the multi-level governance and decentralisation reform process. Without such an entity there can be overlapping activity, inefficient use of resources, policy incoherence, misaligned priorities, and poor policy and programming integration in government reform.

The primary objective of the centre-of-government is to ensure strategic, evidence-based and consistent policy implementation across government. While each country’s centre-of-government will depend significantly on its historical, cultural and political forces, there are similarities that emerge with respect to their functions (Box 2.7). The centre-of-government does not command or control what should be done by other ministries, agencies or levels of government. Its role is rather one of stewardship – guiding, supervising and managing government processes to ensure that integrated policy efforts (e.g. regional development, decentralisation, etc.) and sector policy (e.g. agriculture, education, energy, etc.) are coherent and consistent rather than contradictory; that policy priorities are acted upon and that government objectives are met. Depending on the country, the body may be linked specifically to the executive structure (e.g. the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet in Australia, the Ministry of the General Secretariat of the Presidency9 in Chile, the Prime Minister’s Secretariat in Sweden) or a functional institution, such as Canada’s Treasury Board Secretariat, or the Office of Management and Budget in the United States. While in Ukraine there is a Secretariat for the Cabinet of Ministers, which would be the logical choice for such activities, its main focus appears to be centred on ensuring the legal conformity of acts and legislation.

There are two immediate ways to strengthen Ukraine’s centre-of-government practices that do not require creating new institutions. One option is to reinforce the Secretariat for the Cabinet of Ministers with a group that could perform additional centre-of-government functions. The second would be to house centre-of-government functions with another existing body. The Reforms Delivery Office is a strong candidate for such a role, as it is already fulfilling some centre-of-government functions (Box 2.8). In both instances, functions could be assumed gradually, for example focusing on specific reforms or areas of the government programme (e.g. decentralisation) and then extending into a more complete centre-of-government role. This could satisfy the current need, and might also serve as a first step towards improved governance practices overall.

Box 2.7. The centre-of-government: What it is, why it is important, what it can do

The term centre-of-government refers to the administrative structure that serves the executive (president, prime minister or governor at the subnational level, and the executive Cabinet collectively). It does not include other units, offices, agencies or commissions (e.g. offices for sport or culture) that may report directly to the executive but are, effectively, carrying out line functions that might equally well be carried out by line ministries. An effective centre-of-government is essential for steering policy development and implementation. It can help overcome ministerial and departmental silos that thwart co-operation and create wasteful duplication of policies and institutions. A well-functioning centre-of-government helps sustain a comprehensive long-term vision, manage risks and crises, and ensure an integrated approach to policy and reform. It plays a key role in communicating, as well as securing support and monitoring action. Who is at the centre-of-government varies by country. It will always include the body or bodies that serve the head of government and/or head of state, and is often accompanied by the Ministry of Finance.

Among the various roles for the centre-of-government are to:

provide a strategic overview of government policy activities, including a foresight function aimed at identifying emerging issues and building anticipatory capacity

increase policy coherence by ensuring that all relevant interests are involved at the appropriate stages of policy development

communicate policy decisions to all concerned players and to provide implementation oversight

apply effective regimes of performance management and policy evaluation

ensure consistency and coherence in how policies are internally debated and how they are delivered and communicated to the public.

Centre-of-government responsibilities can include:

strategic planning

policy analysis

policy co-ordination

risk management/strategic foresight

regulatory quality and coherence

monitoring policy implementation

preparing the government programme

preparing Cabinet meetings

communicating government messages

human resource strategy for the public administration

public administration reform

relations with subnational governments

relations with the legislature

supra-national co-ordination/policy.

Sources: OECD (2014b), Slovak Republic: Developing a Sustainable Strategic Framework for Public Administration Reform, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264212640-en; OECD (2015), Government at a Glance 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2015-en.

Box 2.8. The Reforms Delivery Office in Ukraine

The Reforms Delivery Office is responsible to the prime minister and serves as an advisory body for the Cabinet of Ministers. Its primary tasks are analysis and reporting for government and international partners in diverse policy sectors (e.g. decentralisation, economic development, regional development, etc.). It is also responsible for the project management of different reforms on the government agenda. For example, the team dedicated to public administration reform is working with eight ministries to pilot a new structure; other teams work on the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, improving the business climate, etc.

With respect to decentralisation, the Reforms Delivery Office has identified a need for better information flows regarding implementation activities by ministries and donors. It has been working on mapping the institutional architecture to gain a better understanding of projects and programmes across the territory in order to identify duplication of effort and ensure better coherence.

Source: OECD interviews.

Strengthening central level co-operation mechanisms in support of reform

Limited co-ordination across and among levels of government is challenging the implementation of Ukraine’s reform agenda. Co-ordination is needed to identify and harmonise policies and priorities, as well as to ensure effective regional development planning and the public investment to support it. Among OECD governments, legislation and laws for co-ordination tend to be the most frequently used co-ordination mechanisms, followed by co-ordinating bodies. Other popular ways to manage national/subnational relations are co-operative agreements and contracts (Charbit and Michalun, 2009). At the subnational level in Ukraine, agreement-based co-operation is gaining traction in the form of inter-municipal co-operation, but there is room for stronger horizontal co-ordination at the central level. In addition, reinforcing vertical co-ordination mechanisms, particularly ones that foster a relationship based on partnership among levels of government rather than hierarchy, will become increasingly important as local communities become more empowered.

Introducing an inter-ministerial council to ensure reform and sector co-ordination

There is a strong need to boost inter-ministerial co-ordination capacity for multi-level governance and decentralisation reform. Very few reforms are likely to touch so many areas of government, and action in one sector or area can easily trigger a domino effect that requires co-ordinated action in another area. Added to this is the visibility of decentralisation reform in Ukraine. It is a priority of the current government and is on the agenda of most government actors and institutional stakeholders, with extensive programming planned and already underway.10 The Ministry of Regional Development is responsible for implementing the country’s decentralisation process and ensuring that its objectives are reached, but it is confronted by resource challenges and an institutional culture that traditionally works in a siloed manner.

Many countries undertaking reforms as complex as Ukraine’s establish a high-level inter‑ministerial council or commission with a mandate to ensure or support a co‑ordinated reform process across ministries and agencies. Often these bodies are chaired by the prime minister and are composed of ministers from the relevant ministries and high-level agency representatives when appropriate. Some countries, such as Japan and New Zealand, establish more broad-based entities, and include subnational government associations and non-government stakeholders (OECD, 2017a). Reform implementation is usually assigned by this body to the most relevant line ministry, helping to legitimise its mandate to co-ordinate other line ministry activities that relate to territorial reform. Such bodies are essential for identifying priorities, outlining reform sequence and ensuring that the various different parties involved buy into the process, thereby minimising obstacles at each stage. They are well-placed to support coherent reform implementation, and can sponsor ongoing dialogue among relevant stakeholders. This helps identify what works and what does not, potential risk factors, as well as relevant – and ideally more integrated and innovative – solutions.11 These entities can be established strictly to steward decentralisation reform (and disbanded at some point in the future), or they can be already established inter-ministerial regional development councils responsible for overseeing and co-ordinating regional development more broadly, and then tasked with taking up decentralisation reform as part of their portfolio. Poland supports the implementation of its development policy with a high-level Co-ordinating Committee. This is a consultative and advisory body of the prime minister, chaired by the Minister for Economic Development (Box 2.9). While the Polish example emphasises regional development, Ukraine could consider establishing a similar body strictly for decentralisation – supporting reform implementation and helping address barriers to the Ministry of Regional Development’s capacity to act.

Box 2.9. Poland’s Co-ordinating Committee for Development Policy

Poland’s Co-ordinating Committee for Development Policy is a body of the Council of Ministers, led by the Minister of Economic Development and with the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development as the first deputy. It is composed of ministerial representatives and invited representatives (e.g. local governments, academia, etc.) on an ad hoc basis. The committee analyses the strategies, policies, regulations and other mechanisms associated with implementing Poland’s Strategy for Regional Development, and assesses their efficiency and effectiveness. Sub-committees, for example on the territorial dimension or rural areas, can be designated. On an annual basis the committee assesses work in progress and outcomes, including with respect to funding, and prepares recommendations for the Council of Ministers.

At least once a year the committee performs an assessment of the works’ progress and the results achieved (including the regional dimension) of the Strategy for Responsible Development, its course of funding including co‑funding from the EU funds, an analysis of the complementarity of support from various operational programmes, EU and national developmental programmes, and private funds. Using the assessment as a basis it prepares recommendations for the Council of Ministers on programme, legal and institutional adjustments.

Source: Government of Poland (n.d.), unpublished documents, Department for Development Strategy, Ministry of Economic Development.

A high-level decentralisation council or committee could support the Ministry of Regional Development’s position as a co-ordinating body for cross-sector government reform. The Ministry of Regional Development has been officially tasked with implementing decentralisation reform, but it apparently has not received clear guidance or a mandate to pull together the diverse government interests (Tkachuk, 2017). This ability is fundamental to ensure that decentralisation priorities are acted upon, and that sector decentralisation reform is coherent within and across sectors, as well as properly sequenced to correspond to local authority capacity to absorb new administrative and service challenges and responsibilities. It could also increase capacity to influence the process with other stakeholders, particularly subnational (oblast and rayon) governments and strong political as well as private sector interests, none of which are always in favour of reform.

Second, a decentralisation council or committee could help address an apparent resource (human and financial) gap that the Ministry of Regional Development faces. If the implementing body lacks the necessary resources (human, financial or infrastructure) to implement reform or ensure that reform priorities are implemented by other institutions, then reform success may be limited. A high-level decentralisation council or committee could help address such an issue, by finding ways to bridge a resource gap.

Building stronger vertical co-ordination and collaboration mechanisms

The limited co-ordination among and between government levels is another significant challenge that impedes the successful implementation of Ukraine’s decentralisation agenda. Frequently used tools for co-ordination include laws and legislation, planning requirements, contracts and other binding agreements, and dialogue bodies. Ukraine’s multi-level governance dynamic has traditionally been top-down and driven by laws, legislation and plans. Through Ukraine’s reform process, particularly at the local level, subnational governments are becoming increasingly responsible for the development of their territories and communities, including development planning. Success at all levels of government will depend on a clear communication of objectives and priorities, both top‑down and bottom-up; agreement on development and investment priorities; and co‑ordinated action, particularly in areas where competences and/or interests overlap (e.g. transport infrastructure, urban development and land use, etc.). Therefore, reinforcing vertical co-ordination mechanisms, particularly ones that foster a relationship based on partnership among levels of government rather than hierarchy, will become increasingly important, especially as communities become more empowered.

Strengthening co-ordination through multi-level dialogue

Ensuring that different levels of government are aware of each other’s vision for development, priorities and planned activities is fundamental to coherent policy implementation. This does not seem to occur in Ukraine with respect to decentralisation reform. Ministries are aware of the decentralisation reform and are pursuing decentralisation in their own sectors (e.g. health, education, social services, land use, transport) with minimal cross-sector dialogue, and even less multi-level dialogue. This will only serve to reinforce traditional ways of working in a context where one success factor is adequate co-ordination mechanisms. This can be aggravated by a mismatch in the “territorial logic” of the subnational bodies (e.g. agencies) of ministries or other central level institutions. There is a significant need for solid horizontal and vertical co‑ordination when the territorial boundaries of these entities do not match each other or subnational administrative boundaries, which is frequently the case in Ukraine. Greater co-ordination of their policies and a more co-ordinated territorial approach could improve coherence between the agencies that must intervene in the territory, and among the various government levels.

Consideration should be given to a dialogue body that brings together representatives from all levels of government. Ideally this type of mechanism should be as much part of the political level as the administrative or technical level, bringing together civil servants from different levels of government who are also involved in implementing the decentralisation reform. This has proven successful in Poland with the Joint Central Government and Local Government Committee and in Sweden through the Forum for Sustainable Growth and Attractiveness (Box 2.10).

A cross-sector, multi-level body such as those found in Poland or Sweden could help Ukraine build stronger ties among levels of government. Ad hoc meetings with representatives from different levels of government are called together by the Ministry of Regional Development to address specific topics of urgency. This can be extremely useful to gather opinions and find solutions to an already identified problem. However, it does not easily support ongoing dialogue and policy implementation. Building inter‑institutional, multi-level mechanisms could not only help clarify government intentions and objectives, but build trust in the reform process by other levels of government as well.

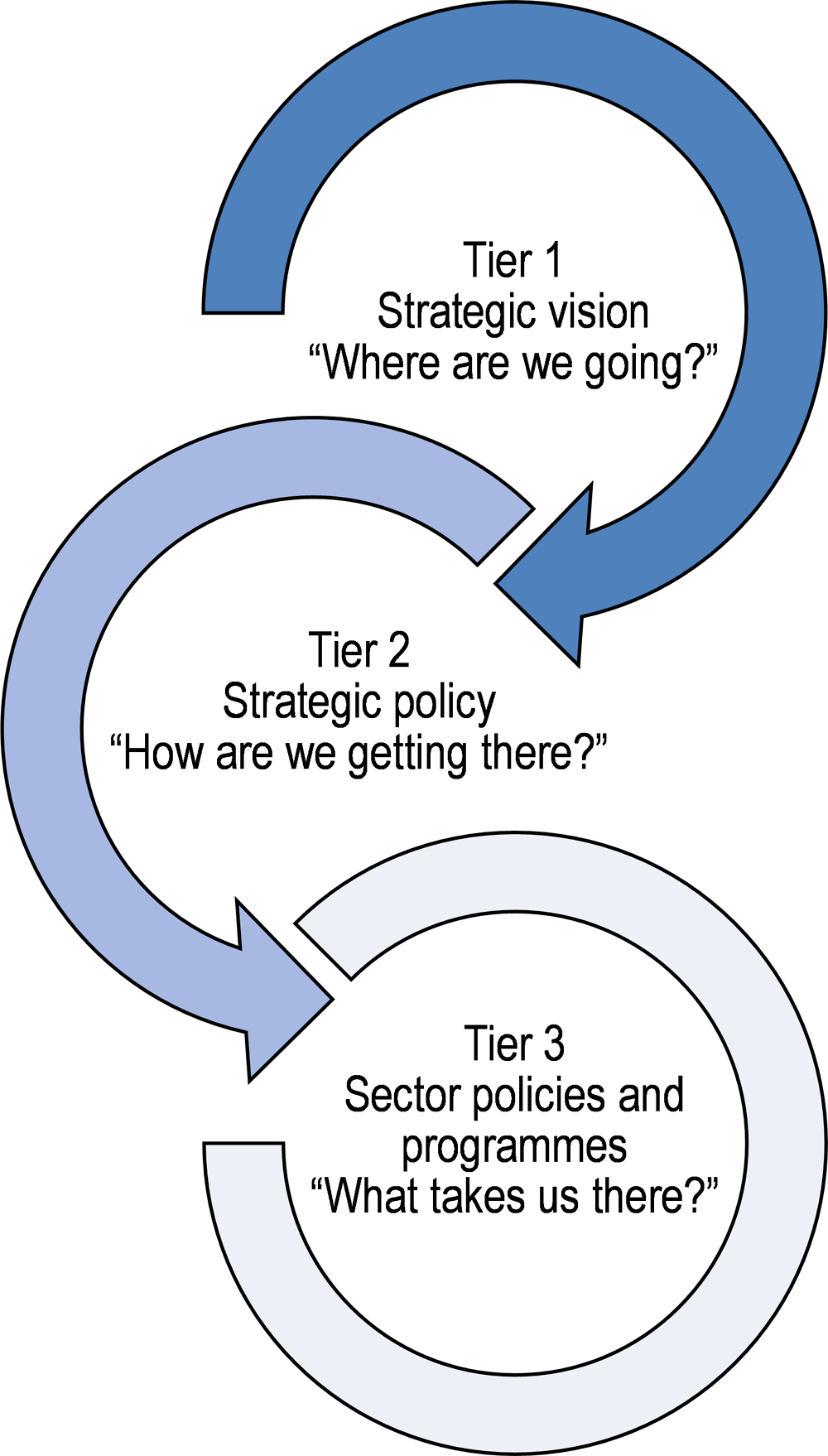

Using policy and planning documents to better support vertical co-ordination

Planning documents, including vision-setting documents, integrated national level strategic policies, sector policies, and subnational development plans are co-ordination mechanisms that build vertical and horizontal links between government actors and their actions. Such documents also connect the various levels of a policy cascade (Figure 2.4) and help co-ordinate diverse interests when implementing a new or reformed policy.

Figure 2.4. From strategic vision to sector policies and programmes

Box 2.10. Dialogue bodies in Poland and Sweden

Poland supports dialogue between levels of government with its Joint Central Government and Local Government Committee. This body is composed of the minister responsible for public administration and 11 representatives appointed by the prime minister (at the request of the chair), together with representatives of national organisations of local self‑government units that work in 12 “problem teams” and 3 working groups. It considers issues related to the functioning of municipalities and to the state policy on local government, as well as with issues related to local government within the scope of operation of the European Union and the international organisations to which Poland belongs. It develops a common position between levels of government and contributes to establishing the economic and social priorities of national and subnational government on matters such as municipal service management and the functioning of communal and district government, as well as regional development and the functioning of voivodeship (province) government. The Joint Commission develops social and economic priorities that can affect subnational development, evaluates the legal and financial circumstances for operating territorial units, and gives an opinion on draft normative acts, programmes and other government documents related to local government (Lublinska, 2017).

In Sweden, the Forum for Sustainable Growth and Regional Attractiveness facilitates and maintains a continuous dialogue among a wide and diverse array of stakeholders (e.g. central government, central government agencies, regional governments, municipalities, third-sector actors and the private sector). The forum is part of the implementation of Sweden’s National Strategy 2015-2020 and is considered an important tool for multi-level governance and to support national and regional level policy development through dialogue and co-operation. It is divided into two groups: one that promotes dialogue between national and regional level politicians, and one that fosters dialogue between national and regional level civil servants (director level). Associated with the forum are networks and working groups, such as an “Analysis Group” that brings together 16 state agencies. The forum is led by the state secretary responsible for regional growth policy, and participants are regional leaders and civil servants with regional development responsibilities in their portfolios; there are about 50 regular participants at the political level. Additional participants, such as ministers, state secretaries and directors within state agencies, can be invited on an ad hoc basis, depending on the agenda topics. The forum can serve as a “regional lens” or “prism” through which to consider diverse sector initiatives, e.g. in housing, innovation and transport.

Sources: Adapted from: Lublinska, M. (2017), “Decentralisation and multi-level governance in Poland: Ensuring coherence between national and subnational development strategies/policies”; Government of Poland (n.d.), unpublished documents, Department for Development Strategy, Ministry of Economic Development; OECD (2017b), OECD Territorial Reviews: Sweden 2017: Monitoring Progress in Multi-level Governance and Rural Policy, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268883-en.

An explicit decentralisation policy that complements and supports the implementation of the vision established in the Concept Framework would be a useful tool in Ukraine’s reform process. It is the missing link in Figure 2.4. In Tier 1 is the Concept Framework and in Tier 3 are sector decentralisation approaches, government and donor-sponsored implementation programmes, etc. An explicit national decentralisation policy (Tier 2) would link these other two levels, establish a consistent course of action for government and other institutional actors to follow with respect to the key activities supporting multi-level governance and decentralisation reform, and to address the challenges that arise. Without a road map or guide for action that all actors can turn to, reform implementation becomes ad hoc, without a clear sequencing of actions or capacity for stakeholders to fully identify the degree to which progress is being made. Such a document, complemented by an action plan articulating a timeline for concrete action associated with measurable, targeted results and monitoring mechanisms, could help prioritise activities and give structure to the next steps of the decentralisation process (e.g. sector decentralisation). It would also provide greater stability, consistency and clarity for stakeholders – they would be able to identify where the process is, what remains to be done, etc. In addition, it builds transparency into the decentralisation process. Such documents become particularly important given that the Concept Framework faces a constitutional block, and no updates have yet been proposed.

An explicit decentralisation policy should be articulated with the input of different national and subnational government stakeholders, including the Committee on State Building, Regional Policy and Local Self-Government of the Rada; relevant line ministries; the subnational government associations; leading academic thinkers; and should incorporate consultation with other relevant stakeholders. This is particularly important to ensure that the strategy and supporting policies and plans are not prescriptive, but are collaborative and shaped with the input of diverse stakeholders who will also be responsible for implementation. When there is agreement surrounding what is to be achieved and how, the process becomes more collaborative, integrated and more likely to succeed.

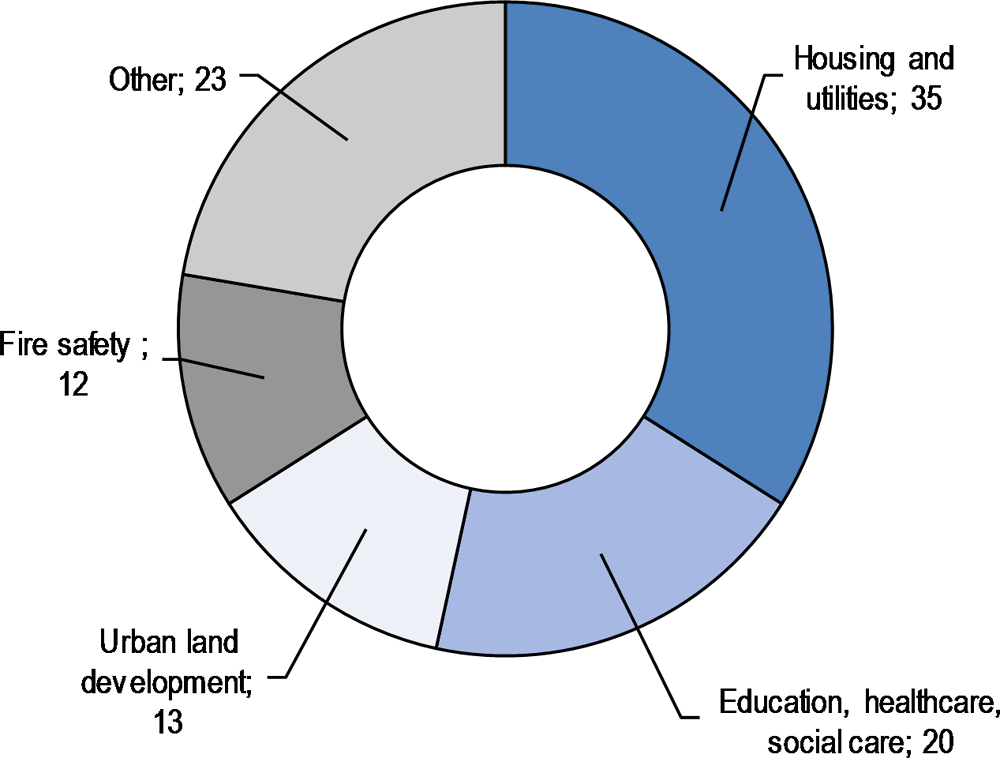

A decentralisation policy and action plan could also help mitigate the impact of other issues affecting the progress and stability of reform. For instance, the government recognises that amalgamation and fiscal decentralisation are first steps in a larger process. However, it has not clearly established what the larger process is (the job of a policy); resulting in an increasingly ad hoc decentralisation process characterised by significant instability, as the government advances and then retracts proposals and benefits associated with decentralisation. This is clearly visible with respect to the State Fund for Regional Development, but also with the excise tax on petrol, land-use rights and the use of subventions in education, for example. Furthermore, it is not clear how the government wants to continue decentralising beyond institutionalising sector-based decentralisation (e.g. in education, healthcare, transport and land use). While sector decentralisation is likely to be necessary, it is not certain that the communities formed from the amalgamation process – unified territorial communities (UTCs) – are ready to accept or absorb more responsibilities. Many are having difficulty absorbing those they have been given – particularly the smaller ones. An explicit decentralisation policy could help guide the development of solutions to these issues, particularly important as constitutional reform, while still necessary, seems increasingly distant.

An associated action plan for decentralisation would also help prioritise and sequence the various third-tier activities – i.e. sector decentralisation policies and decentralisation-associated programmes – that distinct decentralisation stakeholders intend to implement, such as capacity building among subnational civil servants, infrastructure development, supporting small and medium-sized enterprise development, etc. In a context such as Ukraine’s, where structures are traditionally hierarchical, risk taking is often low and vested interests are such that there is an incentive to ignore or bypass actions for the “greater good”. Therefore, it is essential to give clear guidance on what needs to be done, provide incentives to do it and establish mechanisms to that ensure accountability. If these elements are in place, it is likely that even more can be accomplished.

Box 2.11. Recommendations for strengthening co-ordination mechanisms and ensuring successful decentralisation

To strike a better balance in territorial reform and ensure the conditions for successful decentralisation, the OECD recommends:

Strengthening co-ordination mechanisms to ensure that actors in the reform process are moving in the same direction and that priorities are well-aligned. This includes:

Introducing an explicit decentralisation policy to establish a consistent course of action for decentralisation stakeholders, using it to:

bring together input from different national and subnational stakeholders to ensure that decentralisation policy and plans are not prescriptive, but collaborative, thereby gaining broader ground for support

guide sector or other institutional actors with respect to decentralisation activities and managing challenges that arise

establish a road map for reform (action plan) with a timeline for concrete action, establishing overall desired outcomes (that are measurable), and giving structure to next steps in the decentralisation process (prioritisation and sequencing).