Chapter 3 presents the fiscal component of Ukraine’s decentralisation reform. It highlights how the reform has developed and the implementation process. It offers an in‑depth examination of the impact that fiscal decentralisation is having on subnational government revenue and expenditure, and equalisation systems, as well as the fiscal challenges that local communities are facing in light of the reform. Insight is provided into the management and public investment tools that could better support the delivery of public services, including the role of public enterprises, inter-municipal co-operation, and the need for more effective capital transfers for subnational investment. The chapter ends by exploring opportunities to reinforce human capital at the subnational level and the impact the decentralisation is having on the subnational government staff.

Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine

Chapter 3. Strengthening fiscal decentralisation in Ukraine

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

Fiscal decentralisation is not new to Ukraine. It began at independence, was codified into the 1996 Constitution, the 1997 Law “on Local Self-Government”, and the Budget and Tax Codes that establish the basic rules for local government funding, budgetary relations and equalisation mechanisms. It is supported by the 1997 ratification of the European Charter of Local Self-Government. The principles contained in these instruments have not been fully implemented, however, despite important fiscal reforms to increase subnational government fiscal resources and improve the transparency and predictability of inter-budgetary relations. While fiscal decentralisation is at the core of the decentralisation process, it seems to have slowed, stagnated and even regressed, especially between 2010 and 2014.

The Concept Framework of Reform of Local Self-Government and the Territorial Organisation of Power, published in April 2014, took full measure of the importance of these challenges and set fundamental principles and ambitious goals for political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation (see Chapter 2). In terms of fiscal decentralisation, the Concept Framework addresses the need of sufficient resources to cover statutory responsibilities; a reform of the intergovernmental grants system, including equalisation; a reform of taxation, including the need to develop tax autonomy over rates and bases; easier access to borrowing; balanced state control on local finance; increased budget transparency and efficiency; and more ability to manage land resources (see Annex 3.A).

The implementation measures adopted to realise the fiscal component of the Concept Framework started in December 2014 with major changes to the Budget and Tax Codes.1 Amendments were introduced to expand the revenue bases of several categories of subnational governments, change the tax-sharing arrangements, establish new local taxes and introduce a new equalisation system, modify the system of grants, relax borrowing constraints, and improve budgeting and financial management.

Reforms take time to translate into significant changes, but the impact of these measures gradually became evident beginning in 2015, and especially in 2016 and the beginning of 2017. The most significant changes thus far observed primarily concern a reallocation of powers and resources across subnational levels of government rather than a true transfer of competences and resources from the central government to lower levels of government. It should be noted, however, that the oblast (regional, TL2) and rayon (intermediate) levels function most frequently as territorial entities of the central government, which makes changes more difficult to identify and assess in terms of decentralisation. With the emergence of more powerful cities and communities, the situation could rapidly evolve if the central government effectively continues to deepen its decentralisation policy and addresses political, administrative and fiscal in a balanced way.

This chapter is comprised of two parts. The first part describes fiscal decentralisation in Ukraine as of end-2014, confirming the country’s still centralised nature in fiscal matters. It provides an analysis of the main reforms which have been adopted since late 2014 in numerous areas, including the reforms of inter-governmental grants and the equalisation system, the tax-sharing arrangements and own-source taxation, non-tax revenues, and borrowing and financial management frameworks. The second part is dedicated to assessing the progress of reform thus far. It provides recommendations for strengthening fiscal decentralisation in Ukraine, covering measures which could be adopted to improve the grants and taxation systems, the assignment of responsibilities, the delivery of local public services through transparent and efficient management tools, the level of public investments and its governance across levels of government as well as the quality and access to data on subnational government finance and assets.

Fiscal decentralisation in Ukraine: Contextual data and 2014-15 reforms

On paper, basic fiscal indicators suggest a relatively decentralised country. Ukrainian subnational governments represented one-third of public expenditure in 2015, in line with the EU-28 average and just 7 points below the OECD average of 40%. Ukraine compares with the Netherlands, Italy, Poland and Iceland, where subnational expenditure accounts for between 11% and 16% of gross domestic product (GDP) and between 27% and 33% of public expenditure (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Subnational government expenditure as a percentage of GDP and general government expenditure in the OECD countries and Ukraine, 2015

Source: OECD (2017a), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en. For Ukraine: OECD calculations based on IMF database.

Subnational governments are also important public employers: subnational staff expenditure accounted for 56% of public staff expenditure in Ukraine, above the EU‑28 average of 51%, and close to the OECD average of 63%. In terms of fixed investment, Ukraine is above the OECD and EU-28 averages. In 2015, subnational investment amounted to 67% of public investment, compared to 59% in the OECD and 53% among the EU-28. Subnational tax revenues represented 18% of public tax revenue. This is lower than the OECD average of 31%, but not too low when compared to the EU average (23%) or certain OECD countries (Figure 3.2).

In reality, closer analysis shows that Ukraine remains a centralised country. Fiscal indicators are somewhat misleading and should be interpreted with caution. Two main factors that mask the real situation:

Oblast and rayon accounts are not fully “decentralised”. Oblast and rayon administrations are composed of both deconcentrated and decentralised entities. This means that parts of their budgets, although categorised as “local government sector” in national accounts, should in reality be classified as “central government sector”, as executive committees are not elected, represent the central government and are responsible to a presidentially appointed oblast governor while oblast and rayon councils have very few powers (Chapter 2). As a result, the usual indicators tend to overestimate the weight of the subnational sector.

Most local government accounts cannot be properly identified. Data reported in the national accounts cover approximately 700 budgetary entities (oblast and Crimea, the cities of Kyiv and Sevastopol, rayon, and cities of oblast significance). This means that most municipal budgets, i.e. those of cities of rayon significance, towns, villages and rural settlements, are not individualised in the national accounts but managed according to the traditional matrioshka budgetary model and embedded in their rayon’s budgets, on which they depend for allocations. This “trickle-down” budgeting system is also open to political and economic games (OECD, 2003). The creation of unified territorial communities (UTCs), in the framework of the current administrative-territorial reform, is fundamentally changing the situation. The UTCs now have independent budgets, made of tax, grants and non-tax revenues, and have direct fiscal relations with the central government via their oblast administrations, although they can continue to receive subsidies from the rayon.

Figure 3.2. Subnational governments as a share of general government in the OECD and Ukraine (2015)

Notes: The general government sector includes central government, state and local governments, and social security sub-sectors. Investment for Ukraine is defined as acquisition of fixed capital. For OECD countries, the definition includes gross capital formation and acquisitions, less disposals of non-financial non-produced assets. Debt definition is based on that of the OECD. It includes, in addition to “financial debt” (currency and deposits, loans and debt securities), insurance reserves and other accounts payable.

Source: OECD (2017a), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en.

The ambiguity of the administrative and budgetary structure of subnational government explains why it is difficult to have a clear picture of subnational financial autonomy in Ukraine. Legally, there are two budget tiers: state (central government at national level) and local. The local tier is divided in two categories: regional (oblast) with very limited financial autonomy, and local budgets pertaining to rayon, cities of regional importance, cities of district importance, towns, villages, etc., whose financial status is not clearly defined (Standard & Poors, 2013).

The financial weight of each category of government is difficult to capture. It was not possible during the study to obtain data by tiers and categories of subnational governments, so figures were gathered from diverse, external sources (e.g. World Bank [2017a]; Levitas and Dkijik [2017]). A comparison of the data gathered reveals that the regional level is weak, the intermediate level – i.e. rayon and cities of oblast significance – represents 68% subnational spending (78% if Kyiv city is included), and the local level (cities of rayon importance, towns, villages and rural settlements) represents only 8% of the total (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. Breakdown of spending by category of subnational government, 2016 (estimates)

Source: OECD estimates based on World Bank (2017a), “Ukraine: Public finance review”, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/476521500449393161/Ukraine-Public-finance-review and Levitas, T. and J. Djikic (2017), “Caught mid-stream: ‘Decentralization’, local government finance reform, and the restructuring of Ukraine’s public sector 2014 to 2016”, http://sklinternational.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/UkraineCaughtMidStream-ENG-FINAL-06.10.2017.pdf.

Subnational government expenditure and investment are constrained

Subnational government spending power is restricted

Subnational government functions are broadly described in numerous statutes and regulations (Annex 3.C)2 and spending responsibilities are divided into delegated functions and exclusive or own functions. Delegated tasks concern the provision of public services such as education, health and social welfare. The central government is formally responsible for those functions and provides subordinate governments with targeted funds to carry out these tasks. They “transit” through local budgets but subnational government authorities have limited authority over them. Subnational governments also have limited autonomy in the management of their functions. Legal obligations, service organisation, financing, human resources, performance standards, etc., are all defined and monitored by the central government, leaving little or no discretion for subnational governments in the performance of delegated functions.

The ability of local governments to allocate expenditures between and within sectors is quite limited. The budget formation at the service facility level and its aggregation in the local budget are based on norms set by line ministries. For example, local governments are in charge of all of the functions of education except for higher education. However, the Ministry of Education retains full control over the norms that govern staffing, teaching hours, non-teaching personnel ratios and class sizes – based on an oversized network of schools instead of on the actual demand for the service, e.g. enrolled children or school-age population in the jurisdiction (OECD, 2014a). Delegated functions represent the bulk subnational expenditure: education, social protection and healthcare amounted to 78% of subnational expenditure in 2015. This means that about three‑quarters of all subnational spending are made on behalf central government. Most public expenditure for health and education is channelled through subnational governments: 83% for health and 74% for education, well above the EU and OECD averages.

By contrast, “exclusive functions” mainly concern local public goods such as utilities, housing and social protection for which subnational governments have more autonomy and which are financed from general transfers but also own resources. They are vaguely defined and represent a minor portion of subnational expenditure, particularly in comparison to OECD countries (Figure 3.4): 7% for economic affairs and transport, 6% for housing and community amenities and general public services (administration), 3% for recreation and culture, and 1% only for environmental protection. Almost all public spending on housing and community amenities (supply of potable water, public lighting, cleaning, urban heating, urban planning and facilities) also passes through subnational governments.

Figure 3.4. Breakdown of subnational government expenditure by area (COFOG): OECD and Ukraine, 2015

Note: 2015 COFOG data are not available for Canada, Chile or Mexico. 2014 COFOG data for Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Switzerland and Turkey. For the United States, data in the function “housing and community amenities” include the “environment protection” function data.

Source: OECD (2017a), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en. For Ukraine, OECD calculations based on IMF database.

This breakdown of responsibilities also explains the weight of staff expenditure in public staff spending in Ukraine. Subnational staff expenditure accounted for 38% of subnational spending, slightly higher than in the OECD and the EU, on average, and close to Sweden or the Czech Republic. Most of this expenditure is for the remuneration of teachers, medical staff and social workers (delegated functions). Thus, subnational governments act as paying agents on behalf of the central government.

There has been little progress in spending decentralisation

Progress in spending decentralisation is not fully reflected in figures. Rather, it appears that decentralisation has resulted in a reallocation of spending responsibilities across subnational levels (particularly from the rayon to cities and the UTCs) instead of a reallocation of charges between the central (ministry) and subnational levels. Between 2001 and 2016 in Ukraine, the growth of subnational government expenditure was quite significant, rising from 11.7% to 14.7%. However, the share of subnational government expenditure as part of total public expenditure hovered around 33% (Figure 3.5).

This analysis of local government expenditure at the macro level does not reflect a fiscal decentralisation process over the 2001-16 period. Since 2015, there seems to be movement towards more decentralisation in spending as the decentralisation of new responsibilities and charges progresses, although this remains to be confirmed.

Ukraine’s subnational governments have low investment capacity

Public investment in Ukraine has fallen relative to GDP since 2000, despite temporary boosts in 2012 (due to FIFA/Euro 2012 and the parliamentary elections) (OECD, 2014a) and general agreement that infrastructure investment is a priority. As of 2015, it appeared to be on the rise, however, accounting for 1.8% of GDP in 2015 and 2.2% in 2016 (Figure 3.6).

The level of public investment of Ukraine is particularly low for a low middle-income country. In fact, Ukraine is well below the average of many other lower middle-income countries in the world, where investing heavily in public infrastructure is considered to be a key structural driver of growth. Many have recently found themselves boosting their public investment to fill the infrastructure gaps. In emerging markets and low-income developing countries, public investment rates peaked at more than 8% of GDP in the late 1970s and early 1980s, declined to around 4-5% of GDP in the mid-2000s, but have recovered since then to 6-7% of GDP (IMF, 2015). Public investment in Ukraine is also very low compared to OECD countries. In the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and the Slovak Republic public investment exceeded 5% of GDP in 2015.

Ukraine’s subnational governments do not have the fiscal capacity to heavily invest

Subnational government investment amounted to 1.2% of GDP in 2015, far lower than in most middle-income countries. On average, subnational governments in lower middle‑income countries invest around 1.4% of their national GDP. In upper middle-income countries, the figure is 1.7% (OECD/UCLG, 2016). Subnational investment as a share of public investment is significant in Ukraine, at 67% of public investment in 2015 (Figure 3.7). This is significantly higher than the OECD average of 59% and the EU-28 average of 53%. This confirms that investment is a shared responsibility across levels of government, making its governance particularly complex as recognised by the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government.

Figure 3.5. Subnational expenditure as a share of total public expenditure and of GDP, 1995-2014

Note: 1995-2012 for Australia; 2003-13 for Mexico; 1995-2013 for New Zealand; 1998-2014 for Iceland; 1996-2014 for the Netherlands; 2005-14 for Ireland. No data for Chile and Turkey due to missing time series. For Ukraine, the series is more limited but ends in 2016, taking into consideration the last reform (2001-16, estimation).

Source: adapted from OECD (2016c), Regions at a Glance 2016, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/reg_glance-2016-en. For Ukraine, OECD calculations based on IMF, “Government finance statistics”, www.imf.org/en/Data and the State Treasury Service of Ukraine.

Despite the strong role that local governments play in public investment, they do not have the fiscal capacity to invest heavily: their self-financing capacity is limited by the weight of current expenditure. Meanwhile, capital transfers and investment subsidies are lacking and access to borrowing is limited. As a result, the share of direct investment in their total expenditure is low, despite recent improvement (from 4.5% of local expenditure in 2013 and 2014 to 10.5% in 2016). In addition, subnational governments lack financial stability and predictability – they cannot afford the large-scale multi-annual investment projects that are needed for building or renovating large infrastructure (EBRD, 2014). As a result, infrastructure is heavily underfinanced, and municipal infrastructure needs overshadow the size of local budgets.

Figure 3.6. Public investment in Ukraine as a percentage of GDP

Figure 3.7. Subnational government investment as a percentage of GDP and public investment in OECD and Ukraine, 2015

Source: OECD (2017a), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en. For Ukraine, OECD calculations based on State Treasury Service of Ukraine, www.treasury.gov.ua.

The limited fiscal capacity of the subnational level is a concern given the large need for infrastructure investment. Fixed capital stocks in the public sector are ageing and of mediocre quality, and the country’s infrastructure needs are tremendous. In the area of transport, despite progress over the last three years, Ukraine has one of the lowest road network densities in Europe, together with a significant portion that is obsolete and does not comply with European standards (OECD, 2016b). Rural roads are state- or municipally owned. Their maintenance and modernisation are funded from the state and local budgets. According to the state agency charged with overseeing road development, Ukravtodor (under the Ministry of Infrastructure), in late February 2015, 88% of roads out of a total of 169 647 km required repairs or reconstruction, with almost 40% of them failing to meet requirements for durability. Only 46% of the bridges and overpasses were in satisfactory condition with the rest being in poor to dangerous states due to their extreme age, with as many as 21% of bridges and overpasses being built prior to the Second World War and 51% built during the 1950s through the 1970s (OECD, 2015a; Ukravtodor, 2015). Municipal utilities, such as water and heating, have also suffered from decades of underinvestment. Estimates based on the household survey (World Bank, 2017b) indicate that in 2013, only 27% of the bottom 40% of the population had access to district heating and 23% to hot water, compared to 43% and 38%, respectively, of the top 60% of the population.

Subnational governments have access to various tools for delivering public services which are being improved

Subnational governments can choose between direct or indirect management to deliver a wide range of services, including waste collection, water provision, heating, maintenance of the housing stock, transportation, etc. Direct management means that the service is delivered by an internal municipal service (budgetary organisations). Indirect service provision is in the hands of public bodies or delegated to private actors or via public-private co-operation (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Forms of indirect service providers in Ukraine

Public bodies: either local enterprises 100% owned and controlled by municipal or oblast administrations or an inter-municipal co‑operation body that pools the material and financial resources of different communities in order to deliver or establish additional services.

Joint ventures or joint stock companies in which the local government owns shares: subnational governments provide local services jointly with the private sector through an entity combining public and private capital, or partnerships with the commercial sector.

Private actors: subnational governments may outsource service provision to private enterprises on a contractual basis (e.g. waste disposal), through licencing, concessions or consumer associations. Several laws define key legal principles applicable to municipal concessions, including the applicable sectors (e.g. urban public transport, water, sanitation, seaports, public catering, etc.). The most sophisticated form of public-private co-operation are public-private partnerships (PPPs); however, they are not frequently used at the subnational level in Ukraine.

The sector of municipal-owned enterprises lacks profitability and transparency

The municipal enterprises sector – still large in Ukraine despite shrinking in the past ten years3 – displays a low aggregate profitability. Municipal assets are less efficient (in terms of profitability) compared to other sectors of the national economy. This could be attributed mainly to the composition of municipal assets, but also to the low quality of local asset management. According to NISPAcee (2010), the collection of payments for municipal services extended only to 50-60% of the payments due because of corruption, low qualifications and the poor discipline of managers. One of the many issues surrounding Ukraine’s municipal companies is limited data to assess performance and a lack of transparency and accountability. While the law requires all local governments to publish their budgets and budget performance reports (not always done), reporting does not cover the financial transactions of government-related entities. Despite some technical progress in budget accounting and monitoring, transparency remains low (Standard & Poors, 2013).

Many municipal companies are also underfunded due to low tariffs and weak financial support from the mother municipality. It appears that public underinvestment also results from underinvestment in utility enterprises that provide services at subsidised rates despite needing to maintain an extensive infrastructure network. This contributes to the degradation of municipal physical assets.

Inter-municipal co-operation is still in its infancy but is being promoted

The promotion of inter-municipal co-operation (IMC), now supported by the 2014 Law No. 1508-VII on Co-operation of Territorial Communities (see Chapter 2) can help improve the efficiency of public service delivery when municipalities are too small, and/or have overlapping or redundant functions. There are various formats for IMC in the OECD, ranging from very informal agreements with no judicial framework to highly formalised arrangements. There are also different forms of funding (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Forms of inter-municipal co-operation and funding in the OECD

Most OECD countries have enacted regulations to encourage inter-municipal co-operation. IMC arrangements are now well developed and extremely diverse, varying in the degree of co-operation. They range from the softest (single or multi-purpose co-operative agreements/contracts, e.g. shared services arrangements or shared programmes in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and England/the United Kingdom) to the strongest forms of integration, e.g. supra-municipal authorities with delegated functions in France, Portugal and Spain and even with taxation powers. For instance, in France, public establishments for inter-communal co-operation (EPCI à fiscalité propre) have their own sources of tax revenue and are based on a territorial development project. Between the two, there is a range of different forms of co‑operation.

The dividing lines are between the public law model and the private law model: the private law model is based on the freedom of local authorities to pragmatically opt for the areas and forms of IMC based on the modalities and entities envisaged by this law, such as contracts, associations and commercial enterprises. The public model means that co-operation is regulated in some detail by public laws, including the contractual and financing arrangements, the type of delegated functions (with even mandatory functions), the governance structure, the supervision and control, etc.

In terms of financing, IMC structures are most often financed through contributions from municipality members. They usually complement these subsidies by other revenue sources related to the services they provide, i.e. they charge for local public services via user fees – transport, water provision, waste collection, etc. They can also receive grants from the central government, which is a way for central government to favour IMC. In fact, in some cases in the OECD, IMC has even privileged access to central government grant funding. IMC can also attract EU funds and private capital for public-private partnership initiatives between several municipalities and one or several private investors.

Figure 3.8. From soft agreements to more formalised forms of co-operation

Figure source: Adapted and completed by the OECD based on www.municipal-co-operation.org.

Box source: OECD (2017e), Multi-level Governance Reforms: Overview of OECD Country Experiences, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264272866-en; www.municipal-co-operation.org

Subnational governments have a low level of autonomy in revenue management

The funding system is now dominated by central government transfers

Sixty per cent of subnational resources come in the form of transfers from the central government. This is significantly more than the OECD (38%) and the EU-28 (45%) averages (Figure 3.9). Tax revenues represent 30% of subnational government revenues, compared to 40% in the EU-28 and 44% in the OECD. Over the last 15 years, the respective share of transfers and tax revenue has changed significantly. In 2001, tax revenues accounted for 62% of subnational revenue and grants 30% (Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.9. Structure of subnational government revenue: OECD countries and Ukraine, 2015

Source: OECD (2017a), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en. For Ukraine, OECD calculations based on IMF, “Government finance statistics”, www.imf.org/en/Data.

Figure 3.10. Change in the share of each source of subnational revenue

Local governments in rural areas rely most heavily on central government transfers, which represent more than 75 % of their revenues (World Bank, 2017a). By contrast, in cities, taxes generated 45% of revenues4 in 2015 (INEKO, 2017). In Kyiv, tax revenues represented almost 50% of the city’s total revenues in 2015 (Figure 3.11).

Figure 3.11. Tax revenue as a percentage of total revenue in 22 regional capital cities of Ukraine, 2015

Note: No data available for Donetsk and Luhansk.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEKO, http://budgets.icps.com.ua.

Relative to GDP, central government transfers have strongly increased while tax revenues have decreased (Figure 3.12). The growing dependence of subnational governments on central government resources can reduce incentives to improve service delivery and strongly limits accountability at subnational level.

Figure 3.12. Changes in tax revenue and grants in relation to GDP

The inter-governmental system of grants was substantially reformed in 2014-15

Prior to 2015, the grant system was comprised of one equalisation grant and one social grant, together representing 90% of all transfers. This system had several important drawbacks (OECD, 2014a). These led the OECD to recommend reconsidering the equalisation system in terms of the amount of tax revenues that each local government could count on. It was also suggested to revise the allocation formula in order to make it simpler and less discretionary, by reducing the number of indicators and to use indicators based on the needs of the population in each area to determine resources allocated for the provision of local public services, instead of input indicators.

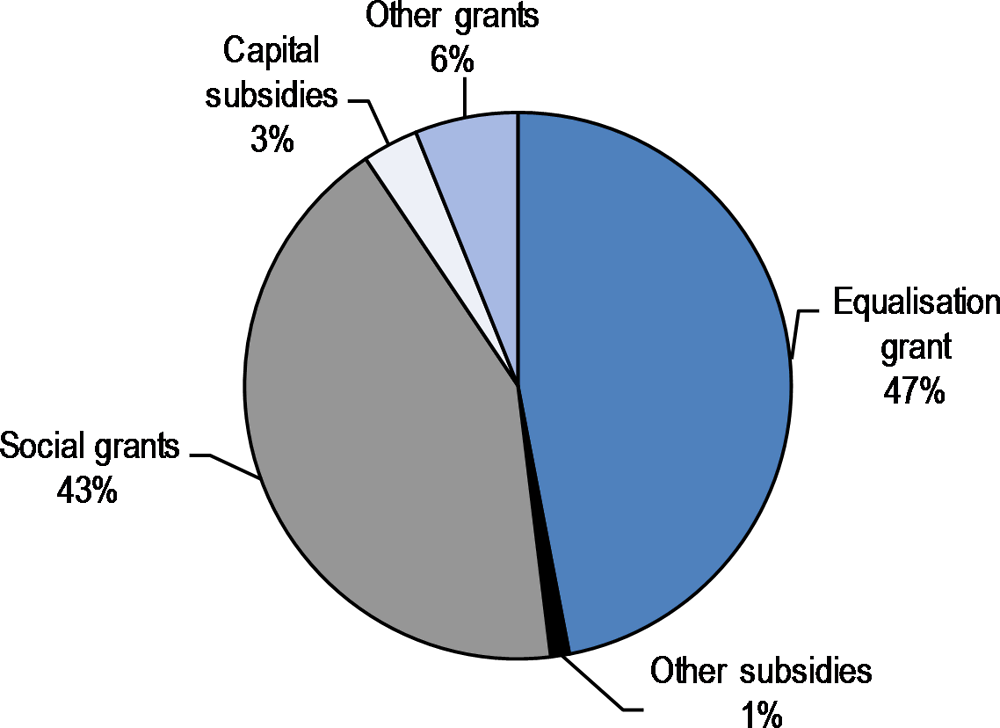

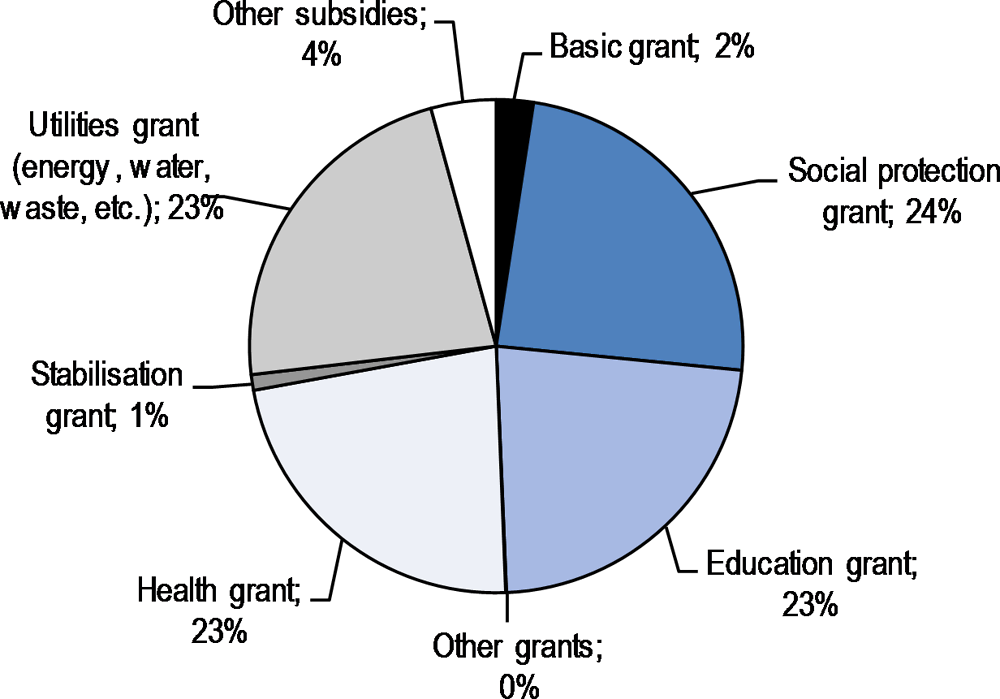

After the 2014 reform, there are still two main categories of grants, but their composition is very different than before. There is the equalisation grant and several formula-based central government transfers earmarked to fund sectoral expenditures, particularly in the education and health sectors. Capital grants and subsidies have also been established or reformed to support investment projects aimed at fostering regional and local development and improving infrastructure (Figures 3.13 and 3.14). The new system of grants aims at ensuring more permanent and stable funding for key responsibilities, as well as enhancing the predictability and transparency behind the allocation of transfers through clearer allocation of rules. One major objective is to improve efficiency in the use of the resources.

|

Figure 3.13. Inter-governmental transfers, 2013

% of total grants

Source: Law of Ukraine “on State Budget of Ukraine 2013” No. 5515 dd, 6 December 2012. Source: Law of Ukraine “on State Budget of Ukraine 2013” No. 5515 dd, 6 December 2012. |

Figure 3.14. Inter-governmental transfers, 2016

% of total grants

Source: OECD calculations based on State Treasury Service of Ukraine. Source: OECD calculations based on State Treasury Service of Ukraine. |

The grants remain very constraining. First, they are, for the most part, earmarked to finance delegated functions and pay staff. They are also associated with guidelines, norms and strict controls. While the intention is certainly justified – to avoid irregularities and inequities related to the provision of education, health and social services across the national territory – they also reduce subnational decision-making power, especially when norms and controls are excessive and not adapted to local specificities.

The equalisation reform

The December 2014 amendments to the Budget Code introduced an equalisation mechanism for subnational government revenues rather than expenditures, basing it on two taxes: the personal income tax (PIT) (for oblasts, rayon, regional towns and communities) and the corporate profit tax (CPT, only for regional budgets). The mechanism has simplified the calculation formula and now takes revenue performance into consideration when calculating the equalisation grants (Box 3.3).

The basic grant amounted to 2.4% of inter-governmental transfers in 2016 and 1.3% of all subnational revenue. In 2015, in 18 regions, the difference between basic and reverse subsidies of all subnational governments was positive (they were net beneficiaries) while it was negative in six others (net contributors). Kyiv city is excluded from the system, despite its high level of PIT and CPT. By levels of government, cities were the biggest donors in 2015 and the rayon were the biggest beneficiaries of the equalisation process. The balance for regional administrations was slightly positive, meaning that, on average, they received more that they contributed. In 2016, it was foreseen that the UTCs would also benefit from the system (PwC, 2016).

Box 3.3. Ukraine’s equalisation grant mechanism

The equalisation system’s main elements are basic and reverse grants. The basic grant is a transfer from the national budget to the local budgets. The reverse grant is composed of funds transferred from the local budgets to the national budget to ensure horizontal equity. The equalisation mechanism is determined by the tax capacity index, which is the ratio between the tax capacity per person of a local budget and the average tax capacity per person of the same level budgets. This tax capacity index determines which local governments will receive basic grant, which will pay the reverse grant and which will be unaffected by the mechanism. The tax capacity index is also used for the calculation of the basic and reverse grants.

The mechanism is represented in Figure 3.15: 50% of revenue surplus is withdrawn from the budgets of local governments that earn more than they spend, but on condition that the tax capacity index is more than 1.1. The withdrawn funds are used to provide basic subsidies. The basic subsidy is only 80% of the required amount (provided that the tax capacity index is less than 0.9) for local governments that do not have sufficient revenue to cover their expenses.

Figure 3.15. New equalisation mechanism: Basic and reverse grants

Source: Reanimation Package of Reforms (2015), “Reforms under the microscope”.

Said differently, local governments with tax capacity above the Ukrainian average by at least 10% will keep 50% of the revenue surplus. Poorer local governments, with tax capacity below 90% of the national average, will receive a basic grant which amounts to 80% of what is required to catch up with the average. Local governments with revenues between 90% and 110% of country’s average will not be subject to either compensation or deduction.

Source: PwC (2016), “Local taxation diagnostic review of local revenues in Ukraine”; Reanimation Package of Reforms (2015), “Reforms under the microscope”.

The reform of the education, health and social grants

The misallocation of resources in the education, health and social sectors resulting from the funding system is particularly problematic (Box 3.4). Prior to reform, the system of grants was not conducive to rationalising and improving the quality of the services, as it was based on expenditure gaps and historical data. In fact, any efficiency improvement would result in fewer resources for the local government.

Since 2015, there have been moves to reform the system. In 2015, a flexibility measure in education and health grant management was introduced, allowing for subnational governments to keep unspent funds from state grants at the end of the year for use in the following year to upgrade the material and technical base of educational and medical institutions. Previously they were withdrawn and sent back to the central government, which could encourage an inefficient use of funds. In 2016, four major sectoral grants were created or adjusted: the social protection grant, the education grant, the health grant and the utilities grants. These four funds are represented in the same proportion in total transfers and in total subnational revenues. Line ministries can allocate these grants directly to subnational governments, and new “principles” for the allocation of funds have been introduced. These principles are based on a formula-based calculation according to sectoral service delivery standards (for services guaranteed by the state) and norms per user. However, these principles have not yet been implemented. The allocation formula used in 2015 and 2016 has been in operation for over 15 years, initially as a part of gap-filling calculation, and for the last 2 years as a stand-alone formula allocating education/medical subvention.

Introduction of new capital funds for regional and local development

Capital investment subventions, which are one of the key sources of funding for capital projects, have long been unpredictable and determined on an annual basis using non‑transparent criteria and priorities (OECD, 2014a). This situation is changing thanks to the creation of the State Fund for Regional Development (SFRD) and the introduction of two new funds for subnational public investment: the subsidy for development of infrastructure and the subsidy for social and economic territorial development.

The SFRD was established in 2013 to support the State Strategy for Regional Development. It finances investment programmes and development projects prepared and submitted by subnational governments. Initially, the attributable funds were allocated to the regions on the basis of a simple formula: 70% was allocated among all regions, according to population, and 30% was allocated based on the proportion of the population falling below 75% of the country’s average GDP per capita. These proportions have changed recently to an 80/20 split.

In 2016, the state budget also introduced a subsidy for social and economic territorial development (UAH 3.3 billion, 3 711 projects) and the subsidy for development of infrastructure in the UTCs (UAH 1 billion, 1 383 projects) to finance development and infrastructure projects in targeted UTCs. Funds are allocated among the UTCs in equal proportions to their area and the size of the rural population, and are destined to fund the construction of administrative service centres, the renovation of social and educational infrastructure facilities, the construction and repair of roads, water supply facilities, the introduction of energy efficient measures, etc. In 2017, these two funds increased to UAH 1.5 billion and UAH 4 billion, respectively.

Box 3.4. An inefficient use of central government transfers in the social, health and education sectors

The health, education and social sectors are oversized and fragmented in Ukraine in terms of network size and staffing, as well as quite inefficient and deliver poor results. Ukraine has about 40% more hospital beds per capita than the EU average. Despite this over-developed infrastructure, only basic services are provided. Ukraine’s score is among the lowest of all transition economies. A survey conducted in 2015 indicates that only 10% of Ukrainians had a good opinion of the quality of care in Ukraine. Eighty-five per cent consider the quality of healthcare services bad or very bad and deteriorating. In education, the school network is large but does not correspond to the pupil enrolment rates, which are declining, especially in rural areas. In the social sector, social assistance spending (cash transfers) is high – among the highest in the region – but Ukraine ranks low in terms of effectiveness of support. By contrast, social care services (support to old age, disability, child services, etc.) are underfunded.

While education and health networks have excess capacity, they lack equity. Schools and medical units in small communities are often understaffed and cannot provide quality services to the local population. Per capita expenditure on education and social services is not homogeneous across territories. The welfare system tends to increase inequities, and social assistance is insufficiently focused on the most vulnerable. Instead, the system tends to favour “categorical benefits” and a “privileged population” that is not, on average, poor.

Education, health and social assistance services are also inefficiently managed. The World Bank found over 70 local government welfare programmes and 39 central government programmes that lack monitoring, management and co-ordination. In the social care area, a significant share of resources is managed by oblasts but not in an efficient manner.

The grant system is partly responsible for the situation, as transfer levels are determined by norms and input-driven indicators based on historical data, rather than on demand-driven indicators based on assessed service needs. For example, the number of doctors is based on the existing number of beds in healthcare facilities and in schools, non-teaching staff is based on the number of square metres of a school facility. In addition, there is a high level of current expenditure that leaves very few resources for capital investments and quality-enhancing projects. Poor municipalities often do not have the capacity to maintain and repair their medical and education facilities, as all their resources are dedicated to operating expenditure. Only the wealthier municipalities can use their own-source revenues to cover financing and operational gaps, and renovate and invest in new infrastructures.

The consequences are paradoxical: a high level of expenditure but a low level of satisfaction in terms of access and quality of services.

Source: World Bank (2017a), “Ukraine: Public finance review”, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/476521500449393161/Ukraine-Public-finance-review; OECD (2014a), OECD Territorial Reviews: Ukraine 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204836-en.

Tax reform has impacted shared and own-source taxation systems

Subnational government tax revenues are low and do not result from their exercise of taxing power. In 2015, subnational tax revenue in Ukraine amounted to 4.5% of GDP, below the OECD and EU-28 averages of 7.0% and 6.2%, respectively (Figure 3.16). Subnational tax revenue amounted to 18% of total tax revenue – compared to 38% in 2001 – well below the OECD average (31%) and the EU-28 average (23%).

Figure 3.16. Subnational tax revenue as a percentage of GDP: OECD countries and Ukraine, 2015

Source: OECD (2017a), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en. For Ukraine, OECD calculations based on IMF, “Government finance statistics”, www.imf.org/en/Data.

Tax-sharing arrangements are particularly important in Ukraine, as it appears that tax revenues are mostly generated from tax sharing with the central government. This represents a further limitation on subnational fiscal autonomy. Approximately 67% of subnational government tax revenue comes from the PIT. The allocation of shares to subnational governments is set in the Budget Code according to a fixed percentage of tax collected locally. Percentages vary according to the category of subnational government: subordinate governments are unable to adjust tax rates or bases. Own-source taxes are limited and all tax receipts are administered and controlled by the State Fiscal Service.

The reforms introduced in 2014 and effective in January 2015 affected shared taxes and own-source taxes. On the one hand, tax-sharing arrangements were modified between the central government and subnational governments and across subnational jurisdictions. Shared taxes now represent a lower share of total subnational government tax revenue. On the other hand, the list of local taxes was modified: some taxes were abolished while others were created or reformed. Furthermore, subnational governments were given more ability to modify tax rates and bases (Annex 3.D). Despite these reforms, it should be noted that globally the level of subnational tax revenues has diminished relative to GDP, to public tax revenues and to subnational revenues.

A new distribution for shared taxes

The reform has also modified tax-sharing arrangements between and across levels of government, especially with respect to the PIT, the CPT, the excise tax on retail sales of excisable goods, environmental taxes and rents for the use of natural resources.

The 2014 amendments to the Budget Code modified the PIT vertically and horizontally. Vertically, the share attributed to subnational governments has decreased in favour of the central government. Prior to the reform, PIT receipts were fully redistributed to the subnational governments (except for Kiev). With this reform, the central government now receives 25% of the PIT as a general rule. Horizontally, PIT shares for each category of subnational government have changed. Overall, the weight of the PIT in subnational tax revenue dropped between 2014 and 2015, from 79% to 62%. Towns of rayon significance, villages and rural settlements which have not merged have lost their share of the PIT. Despite the share of the PIT redirected to the central government,5 in 2016 it still represented 54% of subnational tax and fee revenue, which is not unusual for some OECD countries (Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Personal income tax in OECD countries: A significant source of revenue for subnational governments

In OECD countries, the personal income tax (PIT) can represent a significant proportion of subnational tax revenue. In countries such as Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Sweden, where the share of PIT in subnational tax revenue ranges from 82% to 97%, it is a local own‑source tax, not a shared tax. In Denmark, the local PIT is collected by the central government together with the national PIT. In Finland, the base of the local PIT tax is determined by the central government, but municipalities have full control over the rate. In Sweden, subnational tax revenues come almost entirely from the local PIT, which is an own‑source tax, levied independently from the national PIT. Municipalities and counties have the same tax bases but decide independently to set their tax rate. In Norway, the revenue from the PIT on ordinary income is collected by the municipalities for the central government, the counties and the municipalities. The split of PIT revenues between the three levels of government is determined by parliament as part of the national budget. The tax level is set annually by the Norwegian parliament as the maximum level of municipal income tax. In principle, counties and municipalities can lower the income tax rate for their municipality, but in practice all use the maximum rates. In Portugal, the two autonomous regions enjoy a certain degree of tax autonomy. They are able to retain nearly all of the PIT generated within their territories, and exercise strong control over the rate and base. Portuguese municipalities receive a local PIT surtax capped at 5% of tax receipts collected from local residents, though municipalities can decide to reduce this percentage. In Italy, the PIT is a shared tax and an own-source tax. Part of the PIT receipts are shared and local governments can also choose to levy a surtax on the PIT.

Finally, in some unitary countries such as Latvia, Poland and Slovenia, the PIT is shared and accounts for more than 50% of subnational tax revenue. In Estonia, Lithuania, Romania and the Slovak Republic, until a reform of the System of National Accounts, the PIT was considered a shared tax between the central and subnational governments. With the new methodology, PIT receipts have been reclassified as central government transfers and no longer as tax revenue.

Figure 3.17. Personal income tax receipts as a share of subnational tax revenue in selected OECD countries and Ukraine, 2015

Source: based on OECD National Accounts and State Treasury Service of Ukraine, www.treasury.gov.ua. Execution of the budget (revenues). The definition used is “taxes on individual or household income including holding gains”.

Source: (OECD, 2018), OECD Tax Database, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/tax-database.htm and https://www.oecd.org/ctp/tax-policy/personal-income-tax-rates-explanatory-annex.pdf.

Since January 2015, the corporate profit tax is shared, with oblasts, ARC and Kyiv receiving 10% of CPT receipts.6 The CPT is paid where a company is registered. This generates considerable disparities between regions, in particular a rather unfortunate bias in favour of larger cities, especially Kyiv (Figure 3.18). The CPT represented 4% of subnational tax and fees revenue in 2016.

As part of the reform, the retail excise tax on alcoholic beverages, tobacco, petroleum and gas was introduced in subnational budget revenue in January 2015. All receipts are allocated to local governments, including Kyiv. In 2016, it accounted for 7.9% of subnational tax revenue, 3.2% of total subnational revenue and 0.5% of GDP, which is quite significant. In addition, subnational governments receive a share of environmental taxes (i.e. ecological tax and pollution charges) as well as rents for the use of natural resources (water, forest resources, subsoil) whose shares were modified in 2015.

Figure 3.18. Corporate profit tax receipts per inhabitant per region and Kyiv, 2015

A renewed system of local taxes and fees with an increased taxing power

Some minor taxes were abolished in January 2015 and new local taxes were introduced by the Tax Code. In addition, the local government taxing power on local taxes and fees was enlarged, as they now have greater freedom to set rates and establish exemptions. The new system of local taxes and fees comprises four main local taxes: the single tax (also called the unified tax), the property tax, the parking fee and the tourist tax (Figure 3.19).

Figure 3.19. Breakdown of taxes and fees in total subnational taxes and fees, 2016

Source: Based on based on data from State Treasury Service of Ukraine, www.treasury.gov.ua, Execution of the budget (revenues).

However, local taxes and fees still represent a small share of subnational tax revenues and total revenues, respectively 29% and 12%. They also amounted to only 1.8% of GDP. In addition, rates remain capped and there are some other limitations concerning the ability to set rates and modify bases. For example, the tax rate of the single tax for individual entrepreneurs is decided by local councils, but is capped, while for the other groups of taxpayers there is no taxing power: it corresponds to a fixed percentage of value-added tax (small businesses) or value of agricultural land (agricultural producers). The rate of land tax and the real estate tax other than on land are capped while the rate of the transport tax is fixed (Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. The reform of the property tax in Ukraine

In 2015, Ukraine reformed its property tax (Article 265 of the Tax Code of Ukraine), which is now composed of three different sub-taxes:

The land tax/rent: existing since 1992, it is a mandatory “local” tax or rent (depending on the legal status of the land plot) since 2015. It is levied on legal entities and individuals. The tax rate is set by local authorities but capped (between 1% and 5%), while the amount of the rent is also capped. The land tax/rent is the main component of the property tax, representing in 2016 around 93% of its receipts, 15.9% of subnational tax revenue, 6.4% of subnational total revenue and just under 1.0% of GDP.

The real estate tax other than on land, has been effective since 2015 in its new form. It is now paid by owners of residential real estate properties as well as by owners of non-residential properties, both individuals and legal entities, including non-residents. Cities may impose tax rates on properties based on location (locations bands) and type of real property, from 0% to 1.5% of the minimum wage per square metre of the taxable base as of 1 January. Local authorities can also decide on exemptions and reduced rates. In particular, they can determine the area of the property that is not taxed. Only “extra square metres” are taxed. Tax assessment is based on the state register of property rights, but since 2015/16 also on information collected through the certificate on property rights. This tax accounted for 5.7% of the property tax receipts in 2016, 1% of subnational tax revenues, 0.4% of total subnational revenue and 0.06% of GDP.

The transport tax was also introduced in January 2015. It is paid by individuals and legal entities who own cars registered in Ukraine. Cars not older than five years and with an average market value more than 750 times the minimum wage are taxed by UAH 25 000 per year. This tax is minor, accounting for 1% of the property tax receipts, 0.2% of subnational tax revenue, 0.07% of total subnational revenue and 0.01% of GDP.

The reform of the property tax, with the introduction of a real estate tax, is a positive step for Ukraine, and is aligned with both economic theory and tax practices in many other countries (Box 3.7).

Non-tax revenues are quite constrained but are increasing

Non-tax revenues, which represent 10% of subnational revenues, are generated by property (6%), and administrative fees and revenues from “business activities” (4%). The share of non-tax revenues in total revenues increased from 6% in 2012 to 10.5% in 2015.

Box 3.7. The subnational property tax in the OECD

The property tax is a cornerstone of local taxation in many countries but its implementation and management face many obstacles. The merits of the property tax are regularly praised by economists: visibility, lack of tax export, productivity thanks to the stability of tax bases and solid return on tax collection, lack of vertical tax competition by exclusive or priority allocation to the municipal level, implicit progressivity (property values rise alongside the revenue of their owners), and horizontal equity (OECD, 2017b). These merits do not conceal the weaknesses and limits inherent in its practical application and management, which raise debates and encounter many difficulties. These obstacles explain that the significance of recurrent taxes on property in subnational tax revenue and GDP remains modest, although it varies considerably across countries.

In the OECD, recurrent taxes on property represent 35% of subnational tax revenue on unweighted average but between 90% and 100% of local tax revenue in Australia, Ireland, Israel, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, which are mostly Anglo-Saxon countries. At the other end of the spectrum, it is a minor local tax revenue source (less than 10%) in Nordic countries (Finland, Norway and Sweden), Estonia, Luxembourg, Switzerland and Turkey (OECD, 2016c). It represented 17-30% of local tax revenue in Hungary, Iceland, Japan, Korea and Poland. As a percentage of GDP, recurrent taxes on property range from 0.1% in Luxembourg to 3.1% in Canada and 3.3% in France, the unweighted OECD average amounting to 1.1%.

Figure 3.20. Subnational recurrent taxes on property in the OECD and Ukraine

Note: 2016 is the year of reference for Ukraine; 2013 and 2014 are the reference years for the other countries. Includes: taxes on land, buildings or other structures (D29a) and current taxes on capital (D59a).

Source: Based on data from OECD National Accounts for Ukraine and State Treasury.

Source: OECD (2017b), Making Decentralisation Work in Chile: Towards Stronger Municipalities, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279049-en; OECD (2016c), Regions at a Glance 2016, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/reg_glance-2016-en.

Revenues from property7 tend to be increasing. For example, revenues resulting from the lease of public land could increase in the short term thanks to the June 2017 Cabinet Resolution on Land Resources Management System at the Local Level. The resolution provides that lands will be leased out through auctions only, and a period not to exceed seven years. The amount of land which may be transferred free of charge should not exceed a quarter of the land plots forming the object of the auction. The objective is also to reduce abuses and corruption related to lease of land, ensure more transparency and increase local revenues (Despro, 2017).

Another example of revenue generation from land is the introduction of a land value capture instrument called “shared participation in infrastructure development” allocated to subnational governments in the Urban Planning Law of Ukraine. The law has created a procedure for determining the amount of shared participation (contributions) that developers (investors) need to pay when they engage in construction, reconstruction, rehabilitation, overhauls, re-equipment, etc. of any property. These revenues are directed at developing city infrastructure. In Kiev, the shared participation is charged under the agreement with Kyiv based on the customer’s application and supporting documents. Between 2014 and 2015, the total value of shared participation agreements increased by about 190% in Kyiv.

The revenue from the administrative services fees has also been increasing since the amended Budget Law extended the list of services to be delivered by local governments8 instead of the central authorities. These local governments now collect the associated fees. A network of administrative service centres (ASCs) was created to help improve administrative service delivery. There were 713 ASCs functioning in 2017, 208 of which were created by local governments and 22 in the UTCs with the support of U-LEAD.9

Revenues from business activities are generated by the delivery of local public services, i.e. user charges and tariffs. Here, local governments can establish some charges and tariffs, but this ability is regulated by a complex system which includes legislated limitations to the local government’s powers. Significant reforms are ongoing, including that of local public service tariff setting. Specifically, in March 2017, when the National Commission for State Regulation of Energy and Public Utilities passed a resolution on the expansion of powers of local governments in tariff setting. Local governments can now set tariffs for heat energy production, transportation and supply. Of the currently operating licensees in this area, 74% will become subject to licensing by local authorities. The same will apply in the water supply and sanitation sector: 67% of the currently operating licensees will be supervised by local authorities.

Borrowing and financial management frameworks are becoming more flexible

Subnational government debt is very low and highly restricted

Local government borrowing is underdeveloped in Ukraine. In 2016, it accounted for 0.5% of GDP and 0.6% of public debt (Figure 3.21). Moreover, subnational debt has decreased regularly since 2007, both as a share of GDP and in relation to public debt. Compared with OECD countries, Ukraine has a very low level of subnational debt, close to that of Chile (where there is no official local debt), Greece, Hungary, Ireland and Slovenia.

Box 3.8. Local public service tariff setting in Ukraine

The system of tariff setting is regulated by several laws, in particular the Law “on Housing and Communal Services” No. 1875 of 2004, Law No. 2479 “on State Regulation in the Communal Services Sector” of 2010, as well as sectoral laws on heat supply, water and drinking water supply. In addition, the Tax Code is part of the framework for tariff setting of utilities as well as decrees of the Cabinet of Ministers and resolutions of the national regulatory commission.

The 2010 law in particular established a new system of state regulation in the sphere of municipal services, based on a new national regulatory body: the National Commission for State Regulation of Public Utilities. It took over from local governments the power for setting tariffs for publicly provided water supply and wastewater collection and treatment, transportation, and heating services. However, local governments are in charge of setting tariffs for utilities that are not regulated by the national regulator. These local tariffs must be approved by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine.

In September 2016, a new long-awaited law was adopted setting up a new National Commission for State Regulation of Energy and Public Utilities. It shall become the independent public authority for state regulation, monitoring and control of the energy and public utilities sectors, for granting licences and for establishing tariffs.

In March 2017, the national government passed the resolution on the expansion of powers of local governments in tariff setting. These later will set tariffs in the areas of heat energy production, transportation and supply. Seventy-four per cent of the currently operating licensees in this area will become subject to licensing by local authorities. The same will apply in the water supply and sanitation sector. Sixty-seven per cent of the currently operating licensees in this area will be supervised by local authorities.

Source: Shugart, C. and A. Babak (2012), “Public private partnerships and tariff regulation in the water, wastewater and district heating sectors”, http://ppp-ukraine.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Tariff-Regulation-Report-ENG.pdf; DESPRO (2017), “Decentralisation in Ukraine”, http://despro.org.ua/library/Decentralization%20Newsletter_March_2017_ENG.pdf.

Subnational government debt is composed of internal debt (77%) and external debt (23%). It composed mainly of loans, as the share of securities is very low (2% of debt stock as of 1 January 2017, a decrease from previous years). This is linked to debt restructuring and partial redemption of domestic bonds. Within loans, the share of banks and financial institutions is limited compared to the Treasury (26% vs. 74% in 2016). International financial institutions (e.g. the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, the World Bank, the Nordic Environment Finance Corporation, the International Finance Corporation, KfW Development Bank, etc.) are among the major investors in Ukraine’s municipal service sector, including in transport, infrastructure, heat, water, waste management and energy efficiency measures (EBRD, 2014). Debt is very concentrated, with Kyiv representing around 40%. The debt per inhabitant reached UAH 2 229 in 2015 in Kyiv, ten times more than the weighted average of the other 21 regional capital cities (Figure 3.22).

The low level of debt and its characteristics reflect the constrained legal framework that surrounds borrowing (Box 3.9). It also arises from a conservative stance in authorising municipal borrowings since 2013. Borrowing is strictly controlled and co-ordinated by the central government, and all decisions on municipal borrowing are taken by the Ministry of Finance. Most municipal bond applications have been rejected over the past several years, in response to international pressure on the Ukrainian administration to lower its public debt (Storonianska, 2013).

Figure 3.21. Subnational public debt as a percentage of GDP and public debt in the OECD and Ukraine, 2015

Source: Based on data from IMF database (Government Finance Statistics - www.imf.org/en/Data) and State Treasury Service of Ukraine, www.treasury.gov.ua.

Figure 3.22. Debt per inhabitant of regional capital cities, 2015

Source: Based on data from INEKO, http://budgets.icps.com.ua. No data available for Donetsk and Luhansk.

Box 3.9. Subnational government fiscal rules in Ukraine

The Budget Code provides a legal framework for the local government budget system. It includes the underlying principles, budgeting process and relationships between the state budget and local budgets. It is complemented each year by the Law “on the State Budget of Ukraine”. Local budgets are comprised of two parts, the General Fund and the Special Fund:

The General Fund is formed by the personal income tax, the property tax, the single tax (since January 2015), the corporate profit tax, some non-tax receipts and operating transfers from government. It is allocated for operating spending (e.g. salaries, maintenance, interest, etc.).

The Special Fund is formed by non-tax revenues (own revenues of budgetary entities, assets sales) and capital grants. Resources are earmarked going mostly to capital spending and debt repayment. It comprises the development budget (for capital expenditure and big repairs), the Special-Purpose Fund (special-purpose programmes, such as capital expenditure, repayment of borrowings, creation and rehabilitation of green belt areas, provision of urban amenities, etc.) and the Environmental Fund (environmental programmes) and others. The law allows for transfers from the General Fund to the Special Fund, but not vice versa.

Table 3.1. Budgeting and fiscal rules applying to subnational governments in Ukraine

|

|

General Fund |

Special Fund |

|---|---|---|

|

Revenues |

Taxes, including a share of personal income tax and operating subsides. |

Property taxes and earmarked fees, assets sales and capital grants. |

|

Expenditure |

Operating expenditures, including salaries and interest payments. |

Development-related expenditures, including capital spending and debt repayment. |

|

Deficits and surplus |

Deficit is not allowed, unless it can be covered by free cash. Surplus is allocated to the development budget, repayment of outstanding borrowings and maintenance of the operating balance of budget funds at a predetermined level. |

Deficit is allowed and must be financed by asset sales, borrowings, free cash or transfers from the General Fund. Any Special Fund surplus is allocated to repayment of municipal debt and/or acquisition of securities. |

|

Direct debt plus guarantees |

Not allowed. |

Must not exceed 200% of the average forecast revenue in the development budget over the next two years (excluding multilateral loans guaranteed by the state). Must not exceed 400% for Kyiv. |

|

Interest payments (as % of expenditure) |

10% |

Not allowed. |

|

Borrowing |

Must be authorised by the central government. |

Must be authorised by the central government. |

|

Borrowing in foreign currency |

Not allowed. |

Allowed. Bonds and loans allowed for cities of regional significance. Loans from international financial institutions allowed for all. |

|

Budget payment |

Via State Treasury for all budgets. |

Via State Treasury for all budgets. |

|

Default |

No right to borrow for five years after default. |

No right to borrow for five years after default. |

|

Oversight |

State Treasury, Ministry of Finance. |

State Treasury, Ministry of Finance. |

Source: Adapted from Standard & Poors (2013), “Public finance system overview: Ukraine local government system is volatile and underfunded”.

While still strict, the 2014-15 reform loosened the regulatory framework for subnational borrowing. It offers a simplified procedure for local government borrowing and guarantees based on the principle of “tacit consent”.10 In addition, the scope of borrowers has been extended: all cities of oblast significance are now allowed to borrow long term using both loans and bonds, as well as in foreign currency from banks and international financial institutions. Oblasts and rayon are still not allowed to borrow, with the exception of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. It must be also noted that since 2011, all municipalities, regardless of population size, have the right to borrow, but only through loans and only from international financial institutions.11 To ensure compliance with the threshold of the public (local) debt and government (local) guarantee, the central executive body keeps a Register of Local Borrowing and Local Guarantees – an information system that contains details on the local borrowing incurred and local guarantees granted.

Budgeting and financial management are being improved

Different local management reforms have been undertaken to improve administrative and executive processes. They cover diverse areas, including human resources management, financial management (i.e. budgeting, accounting and debt management), organisational management, optimisation of administrative process, e-government, quality management, open government, citizen participation, etc. which are beyond the scope of this report.

In Ukraine, subnational financial management is constrained by a number of restrictions and limits imposed by the national legislation, the Ministry of Finance and the State Treasury. Subnational government revenues are directly administered by the State Treasury. In addition, they have little ability to manage their own revenues, due in part to a degree of regulation, and in part to a lack of human, financial and technical capacity to administer resources, except in very large cities.

Several measures were introduced in 2015 that introduced greater flexibility to financial management and budgeting. For example, subnational governments are now authorised to open accounts in state banks, not only in the State Treasury, in order to deposit their own revenues derived from budgetary institutions and development funds. This has eliminated, or reduced, the prior dependence that subnational financial operations had on decisions of the government (EBRD, 2014). Subnational budgeting is being modernised as well. Local governments are now fully responsible for their budget planning, rather than having local earnings and expenditures planned by the Ministry of Finance (Kantor, 2015). The principle of budgetary autonomy was expanded, and deadlines for approval of local budgets have been clearly defined, irrespective of approval of the state budget. Finally, Ukraine is transitioning to multi-year budgeting and a medium-term expenditure framework, which offers the potential of greater predictability with respect to financing. This has been done at the subnational level in several OECD countries, including Belgium (Flanders), with its six-year strategic planning system and innovative digital reporting system. Subnational multi-annual budgeting will be trialled in 2018-20 (Ministry of Finance) in order to better develop medium- and long-term investment projects. The introduction of results-oriented budgeting is also foreseen.

The impact of fiscal decentralisation reform and challenges ahead

Though still in their early stages of implementation, the 2014-15 reforms have started to reap positive results. This process, however, has taken place in a differentiated way, which could rapidly become an issue for the success of decentralisation. Moreover, despite some real progress in terms of fiscal decentralisation, i.e. increased fiscal autonomy in some areas, the reform still tends to promote a subnational financing model based on grants and subsidies more than own revenues. Transfers from the state budget are vital to financing devolved responsibilities, and they have steadily increased over recent years to become the main source of revenue for subnational governments. Paradoxically, this means that fiscal reform, which was meant to favour decentralisation, has led to greater dependence on the central government.

Fiscal decentralisation should be sustained and further deepened

Fiscal decentralisation is helping transform the governance system, but it may be at risk

Because of the difficulties in advancing decentralisation through political and administrative reforms as explored in Chapter 2, fiscal decentralisation has been used as a tool for transformation. It is inducing profound changes in the distribution of powers.

Fiscal decentralisation has paved the way for a new balance of powers among subnational governments. As already underlined, budgets of cities of oblast significance and the UTCs have increased substantially. Oblast administration revenues have shrunk while those of the rayon administrations have not shown any significant change for the moment (Levitas and Dkijik, 2017; World Bank, 2017a). Changes in the tax system and grant allocation have shifted subnational organisation and responsibilities.

This pragmatic method has produced some good results, allowing the “critically needed momentum to be maintained” (Levitas and Dkijik 2017). But it may also produce some undesired outcomes that will be difficult to correct in the future. The reduction in oblast administration budgets (and thus of their responsibilities) could contradict the decentralisation reform objective of creating full self-government entities at the regional and intermediate levels. This approach can also lead to some “improvisation and frustration” (Levitas and Dkijik, 2017). This may also generate instability and uncertainty among subnational governments, but for the central government as well, and especially for the population and business community, which is directly impacted by these permanent changes.

Fiscal decentralisation now needs to be better conceptualised in a strategic framework. The government could prepare, in association with representative associations of subnational governments at all levels and other key stakeholders, a fiscal decentralisation strategy, in particular concerning the allocation of powers and responsibilities.

On this basis, a road map and implementation plan for fiscal decentralisation should be prepared and discussed in a multi-stakeholder dialogue. A specific permanent “fiscal decentralisation committee” could be established involving key ministers, subnational government associations, business and citizens’ associations, universities, etc. (see below). At the central level, there should be also an inter-ministerial committee on fiscal issues more generally, to ensure consistency of reforms and regulations concerning subnational government finance.

The implementation plan should identify the necessary steps for the successful execution of fiscal decentralisation in terms of adjustments to make or new measures to take. It should also include tools and indicators to monitor the progress of the action plan and regularly assess the outcomes of the reform.

Subnational governments need more stable and autonomous revenue sources

Despite recent fiscal decentralisation measures, Ukrainian subnational governments are still strongly dependent on the state budget and state decisions for their revenues and expenditures. They have no control over more than 70% of their revenue, as it is comprised of grants and shared taxes. The remaining 30% can be considered own-source revenue (i.e. own-source taxes, fees, rents, property income, etc.), providing them with little flexibility. There is a wide gap between own-source revenues and operation and investment spending needs. This results in large fiscal imbalances. It is, therefore, still necessary to increase the share of own-source revenue in subnational revenues, including own-source taxes and non-tax revenues.

Subnational fiscal power should be reinforced through more flexibility in managing grants, and greater access to external funding. Subnational governments should enjoy more freedom in deciding how to allocate grants, without strict guidelines, norms and control from the central government, even if these are earmarked to specific sectors. The distribution of state transfers needs greater stability and transparency. To support subnational investment for local and regional development, access to borrowing should be facilitated with loosened borrowing rules and the strengthening and diversification of the credit market.

Spending responsibilities should be clearer

Delegated expenditure (i.e. in healthcare, education, social protection) amounts to almost 80% of subnational expenditure. Lack of flexibility in spending these funds leaves subnational governments with little spending autonomy. Many local authorities lack the resources to support their exclusive competences, in particular those necessary for the economic and social development of their territories. The weight of current expenditures on local budgets makes it highly difficult to generate self-financing capacity for investment.

Moving forward it will be necessary for Ukraine to (re-)evaluate the assignment of responsibilities across levels of government in order to ease the burden imposed by some functions on subnational governments and to enlarge their spending autonomy. A review of competences and functions among central, regional, intermediary and local levels should be undertaken to clarify the breakdown of responsibilities and to assess the relevance of delegating some functions to subnational governments. Decentralising does not necessarily mean transferring all functions from the centre to the lower levels of government. It means assigning the adequate function to the adequate level according to the principle of subsidiarity.