At the beginning of each impact measurement cycle, the design phase is critical to ensure that the following data collection efforts will help respond to the social economy entity’s learning needs. This phase entails defining the change strategy, identifying learning needs, and setting impact targets. These three subsequent steps will help ensure that the measurement efforts are geared towards the implementation of the social mission and that they adequately promote stakeholder engagement.

Measure, Manage and Maximise Your Impact

1. Design

Abstract

Measure impact to support continuous learning

Social impact measurement aims to assess the social value produced by the activities of any for-profit or non-profit organisation. It is the process of understanding how much change in people’s well-being or the condition of the natural environment has occurred and can be attributed to an organisation’s activities (OECD, 2023[1]).

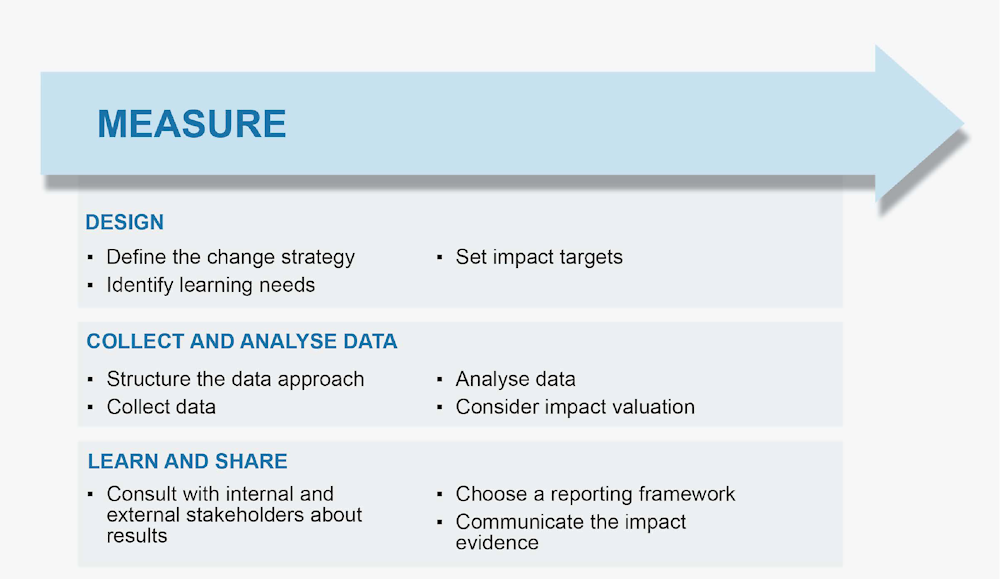

Based on a simple, easily accessible vision that prioritises continuous improvement, social impact measurement can be structured around three main chronological phases (Infographic 1.1):1

Design: defining the change strategy, identifying the learning needs, setting impact targets,

Collect and analyse data: structuring the data approach, data collection, data analysis, (potentially) valuing impact,

Learn and share: consulting stakeholders about results, choosing a reporting framework, communicating the impact evidence.

Stakeholder engagement is a cross-cutting priority through all steps of the measurement cycle, particularly for the social economy. Different measurement cycles may overlap at different levels within the same organisation, and with different timelines.

Infographic 1.1. The impact-measurement cycle

Source: OECD

The design phase comprises three steps: 1) defining the change strategy, 2) identifying learning needs, and 3) setting impact targets. Although social economy entities increasingly understand the importance of impact measurement, conceiving it as an embedded cycle can prove challenging in practice. Indeed, social economy entities may struggle to translate their social mission into concrete social changes for their beneficiaries and beyond. Designing a precise change strategy and developing awareness of the underlying assumptions is critical not only to the success of the measurement cycle, but also to achieving the social mission (Aps et al., 2017[2]); (VISES, 2017[3]); (OECD, 2021[4]); (Impact Management Platform, n.d.[5]). Prioritising learning needs and setting impact targets is another sensitive exercise, given the diversity of stakeholders and motivations for engaging in impact measurement.

Define the change strategy

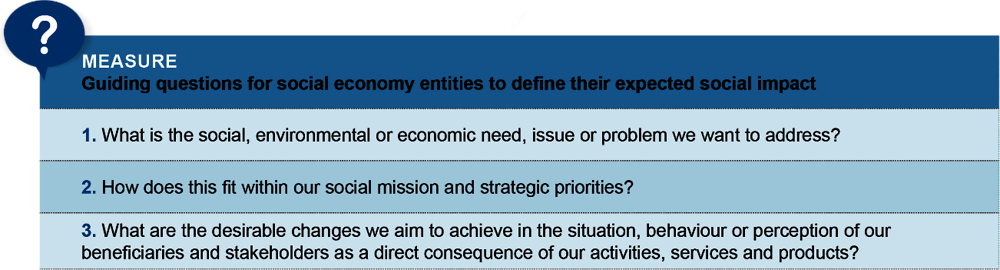

Despite having a well-defined social mission, social economy entities can struggle to describe their change strategy, which links the activities implemented to the expected changes. This involves first distinguishing between direct, indirect beneficiaries and other stakeholders, and then describing the theoretical relation between “what is done” (the actions being implemented) and “what we seek to change” (the impact objectives arising from the social economy entity’s mission) (see Infographic 1.1.). Entities can avail themselves of a wide array of freely accessible online resources to this end (Better Evaluation, n.d.[6]) (Change the Game Academy, n.d.[7]) (ThinkNPC, n.d.[8]) (Learning for Sustainability, n.d.[9]).

The social impact pursued by a social economy entity derives from its social mission, which is typically enshrined in its founding documents. Still, the entity may face several challenges when translating that mission into its impact objectives. Depending on the situation, it may observe divergences (Baudet, 2019[10]; OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2023[1]) relating to:

The temporality of changes considered: does social impact designate short-, medium- or long-term changes?

How unintended or unexpected changes should be factored in: does social impact refer only to the expected consequences of given actions, or does it also include those that are observed even if they were not foreseen?

The positive or negative nature of the expected changes: is social impact only positive or should the negative consequences of actions also be considered?

The question of contribution or attribution: does social impact refer to all observable changes, or more specifically to changes that can be tied to a specific action via attribution or contribution analysis?

Infographic 1.2. Guiding questions for social economy entities to define their expected social impact

Source: OECD.

A growing challenge is distinguishing between “social impact” and “externalities”. The increasingly frequent use of the term “impact” by companies belonging to the conventional economy is blurring the lines with social economy entities, whose operating model is founded on the pursuit of a social mission. The statutory goal of generating social change is the main differentiator between “impact” and “externality”. It follows that a social economy entity’s ability to explain its intentionality by formalising a change strategy is a critical step in the impact measurement cycle.

Ideally, social economy entities will develop a change strategy at the corporate level and then deploy it throughout their activities, starting at the project development stage. In practice, however, they often define the change strategy around a specific activity or programme – either early on, for fundraising purposes, or retroactively, to fulfil reporting requirements. Thus, larger social economy entities with several ongoing activities or programmes may need to reconcile several strategies, to structure a consistent impact-measurement cycle that serves all of them. In such situations, the social economy entity will need to design a unique organisational change strategy explaining how it intends to fulfil its mission, as well as several underlying strategies depicting how it will achieve each programme’s impact targets.2

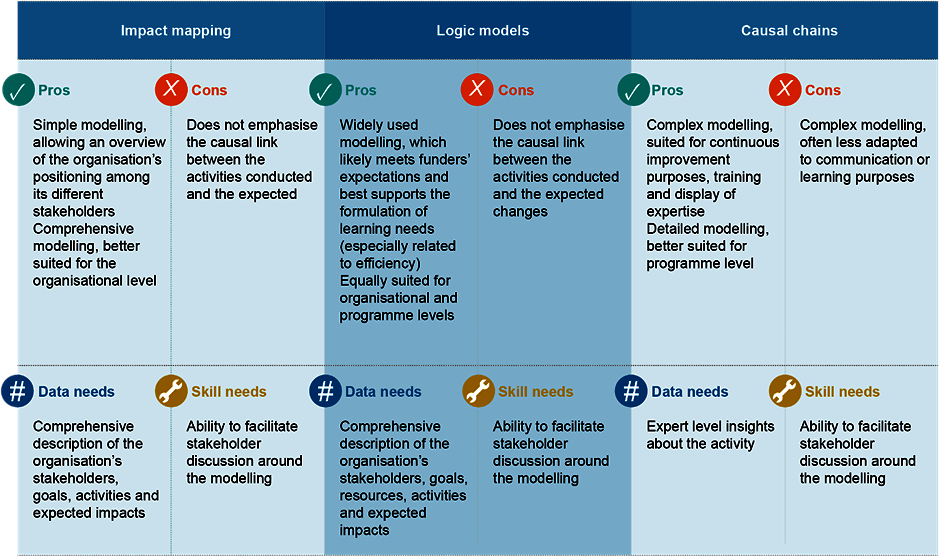

Broadly speaking, a social economy entity can choose from among three main solutions to develop its theory of change:3 logic models, impact mapping and causal chains. However, adaptations are constantly emerging, such as the “Wheel of Change” and “story of change”, which were developed primarily for the social economy. Especially in the area of social innovation, planned activities and desired outcomes are constantly evolving through experimentation, so that “theory of change” models may be considered too constraining. To advance social change, impact objectives and targets need to match the vision of a “desirable future”, as expressed by a diverse range of stakeholders (Besançon and Chochoy, 2019[11]).

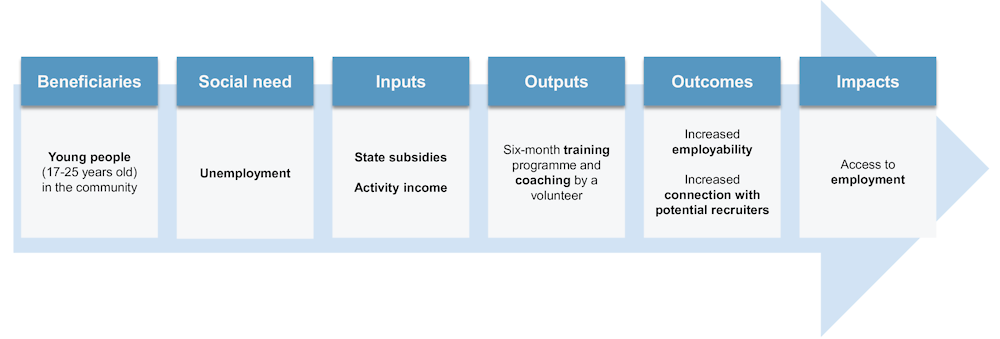

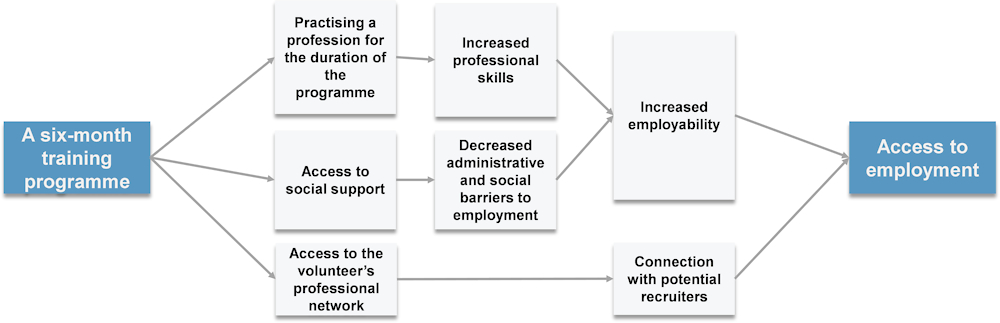

As a general rule, social economy entities and their funders prefer the simplicity of the logic model. This approach helps align different change strategies (e.g. at the organisational and programme level) and identify learning needs (see Figure 1.1). The logic model can be a default entry-level solution in many situations (supported by a wide set of free resources online), preparing for more sophisticated forms of change strategy. At minimum, the logic model helps organisations distinguish between the inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts of their activities (Social Impact Navigator, n.d.[12]) (Center for Social Impact Strategy, n.d.[13]) (Social Impact Toolbox, n.d.[14]). More advanced versions describe the social needs targeted, how the model can be linked to the organisation’s goals, and even how to formulate the learning questions to be addressed in the social impact-measurement cycle. The “Wheel of Change” framework can prove useful in this regard (Neelands and Garcia, 2023[15]).

Figure 1.1. Logic model for a job-training-programme

Source: OECD.

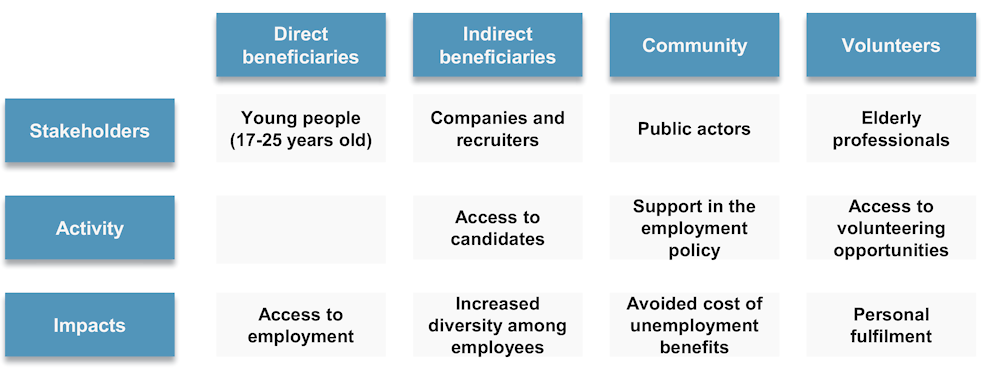

Impact mapping4 encourages social economy entities to identify the various internal and external stakeholders affected by the implemented activities and spell out the impacts expected for each (VisibleNetwork, n.d.[16]; Rockwool Foundation, 2020[17]), either by consulting directly with stakeholders or exploiting existing evidence (see Figure 1.2).5 Such an approach describes how the organisation fits into the wider social economy and offers a vision of its “footprint”. However, impact mapping generally cannot pinpoint the causal links between the implemented action(s) and the expected impacts, and is therefore better suited to defining the change strategy at the organisational level. Similar approaches, like the “story of change” model,6 place greater emphasis on explaining why stakeholder groups and expected impacts are included in the change strategy.

Figure 1.2. Impact mapping for a job-training programme

Source: OECD.

Identifying the causal chains leading to expected impacts is the most advanced approach.7 This exercise forces social economy entities to delineate the different stages, mechanisms, factors and cause-and-effect relationships that should link the activities (logically or chronologically) to the desired impacts (see Figure 1.3). This requires them to reflect carefully on their intervention techniques, and therefore design a more elaborate version of their operating model. Such visual representations are often very detailed and possibly difficult to read and understand, complicating communication and decision-making. They may also be perceived as too rigid, with little room for experimentation, especially in the field of social innovation (Besançon and Chochoy, 2019[11]). Being the most complex option, causal chains are best suited for the programme level, where the delivery model may be easier to pin down. Infographic 1.2 gives an overview of these approaches.

Figure 1.3. Causal chain for a job-training programme

Source: OECD.

Infographic 1.3. Alternative ways to define the change strategy

Source: OECD.

A social economy entity using any one of these approaches to formalise its change strategy will need to consider carefully how it can translate its mission into impact objectives. External support may be needed to develop the theory of change and align the viewpoints of different stakeholders. Besides selecting the most appropriate approach to define its change strategies, the entity must also choose which stakeholders to engage in the process (see Box 1.1).

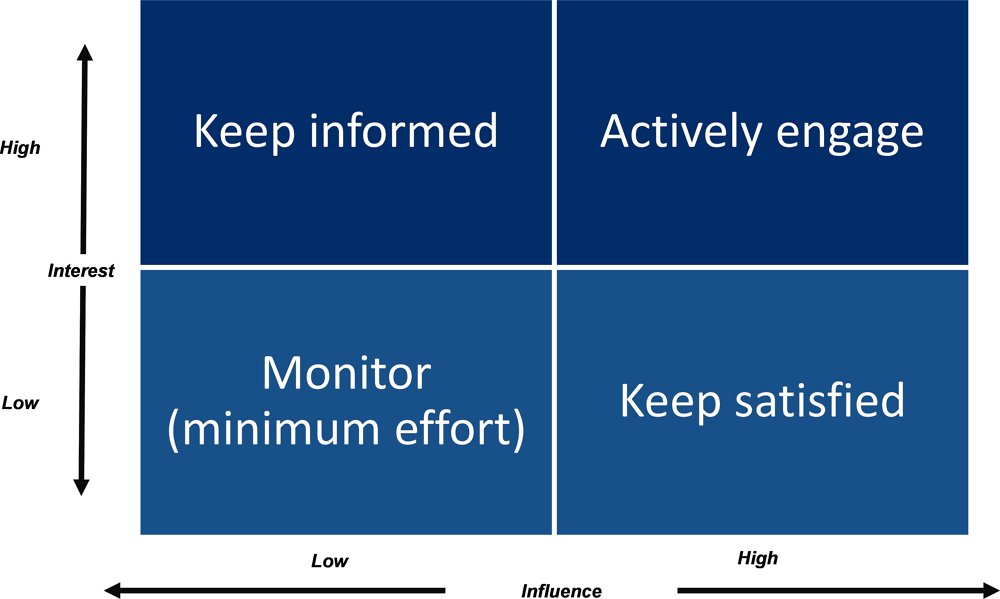

Box 1.1. Choosing which stakeholders to engage in the design phase

Social economy entities are generally embedded in a complex network of stakeholders, who influence both the conduct of their activities and the situation of their beneficiaries. The entities may be tempted to include all their stakeholders in building their change strategy, further complicating this process. Stakeholder mapping is particularly useful in this regard, in that it helps identify the most relevant groups.

Stakeholder mapping involves naming all the stakeholder groups that are relevant to an organisation, analysing how they may (either positively or negatively) influence results, and planning to engage them during the impact measurement phases and steps. Although the notion of “relevance” in this context has several definitions, it generally refers to those stakeholders who are material (i.e. they are affected by or could affect an organisation’s decisions), or have the power and resources to influence an entity’s activities and outcomes. A stakeholder map is therefore typically constructed as a 2x2 matrix, based on high or low interest and influence.

Based on the position within the matrix, the social economy entity can determine whether – and how – these stakeholders should be involved in refining the change strategy, or at another point in the impact measurement cycle. The mapping exercise can involve a few selected internal stakeholders (e.g. managers, employees and beneficiaries) or a wider range of external stakeholders (e.g. suppliers, funders, regulators and competitors), depending on how much time and resources the entity has to perform the mapping.

Further reflection to help inform the change strategy may be guided by the following questions: Why are these individual stakeholders important to us? Which problem(s) do we intend to solve for them? What are their/our expectations in terms of impact (e.g. changes in situation, behaviour or perception)?

Identify learning needs

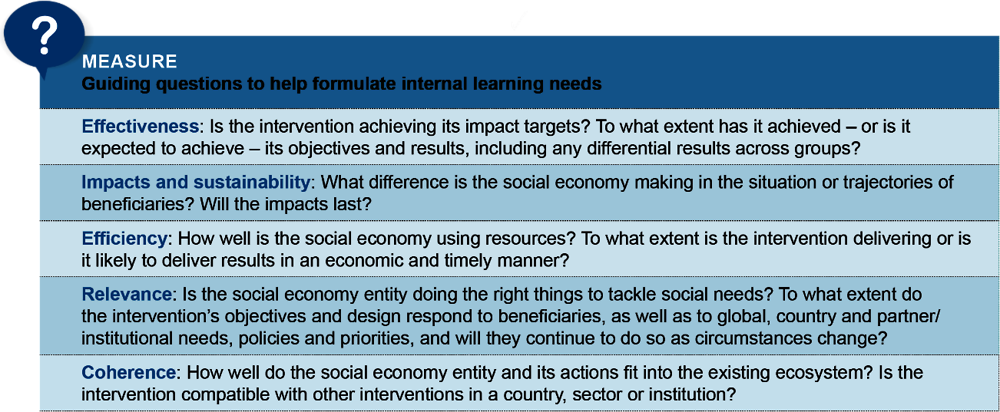

During the design phase, the social economy entity will strive to understand which learning questions the data collection and analysis must answer. This is an opportunity to establish what the entity wants to know (not only in terms of impact results), as well as for and from whom it needs this information (its audience and data sources, e.g. employees, beneficiaries, funders and partners) (see Infographic 1.3.). This internal reflection will in turn inform the selection of indicators, tools and methods, and the nature of the data collected (including the balance between qualitative and quantitative). It also prompts the entity to clarify how it will use the data collected for a specific indicator or target and to double-check whether critical information gaps will be filled. Guidance already exists on how to formulate possible learning needs, often in the form of evaluation questions (European Commission, 2006[20]) (European Evaluation Society, n.d.[21]) (American Evaluation Association, n.d.[22]).

Infographic 1.4. Guiding questions to help formulate internal learning needs

Note: These questions draw on the six evaluation criteria proposed by the OECD DAC Network on Development Evaluation.

Impact measurement by social economy entities often only tackles the question of effectiveness, sometimes adding actual impacts depending on the available means. However, the other questions may be important to help interpret the impact evidence and serve other learning needs (e.g. which partnerships to develop, how to better exploit existing resources, and what additional beneficiaries to target in the future). Indeed, “efficiency” and “effectiveness” are typically accountability-based, whereas the other questions are more conducive to internal learning. Each of these learning questions will have direct repercussions on the social economy entity’s approach to data collection and analysis; hence it will need to review them carefully and balance their weight in the design of the impact measurement cycle.

Social economy entities sometimes struggle to identify the question(s) that will best serve their interest and prioritise between the different learning needs. The general recommendation is to formalise the learning needs(s) according to the motivations underpinning each social impact measurement exercise (OECD, 2021[4]). Different questions may be addressed through subsequent impact-measurement cycles. At times, entities may need expert support to identify information gaps and detect internal learning priorities transpiring from the various stakeholders involved in their governance and activities, in addition to the accountability requirements imposed by external funders and public regulators.

Set impact targets

To assess their effectiveness, social economy entities need to define qualitative and quantitative impact targets. To do so, they must tackle questions like “What do we want to change or to achieve?” or “How much do we want to change or achieve?” In other words, they have to specify both the nature of the expected changes (“we intend to increase access to long-term employment in this community”), and their intensity and extent (“we commit to supporting 100 people in this community and have 75% of them occupy a full-time job over the next 24 months”). This becomes particularly important in the context of their relationships with external funders (especially when they identify as impact investors or venture philanthropists), or when engaging in social procurement opportunities (OECD, 2023[24]).

Targets typically derive from the expected outputs, outcomes and impacts identified in the social economy entity’s change strategy. Box 1.2 on the Poverty Stoplight illustrates how a complex and multidimensional social problem like poverty can be broken down into impact targets. Similarly, the “Quality of Life Model” developed in Catalonia (Spain) reflects individual desires related to eight essential needs: emotional well-being, interpersonal relations, material well-being, personal development, physical well-being, self-determination, social inclusion and rights (Institut Català d’Assistencia, 2009[25]; Gomez et al., 2011[26]). Entities working in social services use this model to select the dimensions that are relevant to their activity and the items they want to measure, possibly also adapting the formulation of each item to their particular context. Similar resources, such as the OECD’s work on philanthropy for social and emotional skills (OECD, 2023[27]), are available for other topics or social needs. Such resources are very useful in helping the entity formalise its change strategy and develop data-collection tools.

Box 1.2. Defining qualitative impact targets: The example of Poverty Stoplight

Many social economy entities act in response to complex multidimensional social and societal issues that are often difficult to define. For example, how does one define a situation of poverty or exclusion? What does “empowerment” mean, concretely? In the context of impact measurement, this challenge is particularly manifest when building the change strategy and defining impact targets, because social economy entities struggle to express the observable “outputs” and “impacts” they intend to produce.

The Poverty Stoplight was developed to measure and address multidimensional poverty at the household level. It empowers vulnerable or marginalised individuals and communities to self-diagnose their own level of poverty and take targeted actions to improve their well-being. It lists specific deprivations that help grasp “what it means not to be poor” across six dimensions:

Income and employment: This dimension aims to measure the monetary aspects of well-being, (including the availability of sufficient financial means to live), and the skills and habits necessary for employment and financial management. It focuses not only on the capacity to acquire resources, but also on their management and use.

Health and environment: This dimension features indicators related to the various components of health, as well as the determinants (both personal and environmental) that influence the biopsychosocial well-being of the person and the family.

Housing and infrastructure: This dimension measures the protected and stable environment that makes personal and family privacy possible, as well as the basic physical systems (in the dwelling and in neighbourhood) that allow access to essential elements of well-being.

Education and culture: This dimension refers to the importance of having tools and knowledge for personal and social development. Education is essential for people to acquire skills and develop their potential, and provides access to information and cultural wealth. Culture is essential for identity formation, and allows a deeper understanding of life and the possibility of sharing experiences.

Organisation and participation: This dimension refers to the interpersonal opportunities and capabilities to have control over one’s own life and be connected to others.

Interiority and motivation: This dimension refers to the intrapersonal aspects that reflect the capacity to have control over one’s own life, recognising the importance of autonomy and the capacity to make decisions that reflect personal and collective values.

These dimensions are further divided into 50 indicators measuring deprivations. Each indicator is accompanied by simple explanations and three images, representing extreme poverty (red), poverty (yellow) and non-poverty (green). This helps families self-assess their status relative to each indicator; social economy entities can also define their change strategy and impact targets around these indicators.

The Poverty Stoplight breaks down the complex issue of poverty into smaller, more manageable problems that become visible and can therefore be tracked in the data collection. In line with the principles of the social economy, the Poverty Stoplight promotes a participatory approach, where a diverse range of community members can contribute to the impact measurement design.

Originally developed by Fundación Paraguaya, the Poverty Stoplight has been implemented globally, including in the United Kingdom and several Eastern European countries. The European Union (EU) is collaborating with the Poverty Stoplight to empower marginalised households through community action and tailored interventions. Notable beneficiaries include the Roma community in Bulgaria, the Slovak Republic and Romania. Through the Poverty Stoplight, participants are expected to gain agency (the capacity to act independently), self-efficacy (the belief in their ability to act) and community mobilisation to achieve structural change.

Source: (Poverty Stoplight, n.d.[28]).

Setting quantitative targets requires an additional element – the baseline, which is the starting point from which progress can be measured (see Box 1.3 for an example). Social economy entities can try to identify the baseline in several ways, including:

a historical approach based on past performance, with stakeholders generally asking to maintain or improve the existing situation

comparison with available public data or other documentation on social needs, with stakeholders generally requesting that the beneficiaries of the action evolve as well or better than the average of a comparable population

reference to external norms or standards, with the entity defining its impact targets based on indicators and performance levels proposed by reference institutions) (UNSTAT, n.d.[29]) (OECD, 2023[27])

their own diagnosis of the beneficiaries’ initial situation, in the absence of a body of data or knowledge around emerging social needs.

Regardless of the approach, defining impact targets carries high stakes. It generally requires close consideration of the context, a good level of information on the social problem at hand, and available data on the effectiveness of comparable interventions and the operating model of the social economy entity. This level of difficulty often leads entities to prefer outputs- or outcomes-based objectives over impact targets.

Box 1.3. Documenting the impact of social enterprises involved in the Lithuanian Rural Development Programme

The Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Lithuania has been investing in social business and the social economy since 2017 in the framework of the EU-funded Rural Development Programme. As part of this programme, social enterprises agree to measure social impact and prove that any support, including minor aid, granted for the start-up or development of a social business shall be used only for the purpose of achieving or enhancing a positive social impact.

To meet the reporting agreements, social enterprises set clear, measurable social impact indicators. Applicants must delineate a geographic area (e.g. village, town, district, municipality, county), as well as define the way in which the problem is identified and the extent of the social impact area. This must be supported by relevant statistical data (e.g. scientific studies), strategic documents from the municipality in which the project will be implemented, or other official documents provided by the institution or organisation collecting such data (e.g. municipality, public health centre, addiction centre, probation service). For those social business or start-ups acting on standard social problems (e.g. unemployment, elderly and child care, and nursing), standard methods and indicators have been proposed, but project applicants are free to choose those best suited to their specific activity.

For example, the social enterprise "Geri Norai" received funding for its "Rykantai Post” project through the Rural Development Programme. The project aimed to decrease rural inequalities by creating a community of social innovators, providing capacity-building programmes, and creating a marketplace for locally produced goods and services. Its primary activities are “social leader breakfasts”, a residency programme for social innovators and sales support. To measure the effectiveness and impact of these activities, the social enterprise selected four clear and measurable indicators: 1) number of initiatives proposed by the local community to the government; 2) number of new people opening new businesses, employed, or enrolled in training; 3) number of people with special needs involved in the project; and 4) number of companies supported that are still in business. These indicators had original baseline starting positions; they were measured immediately after the intervention, and at 6-month and 12-month intervals.

Source: www.rykantupastas.lt (in Lithuanian).

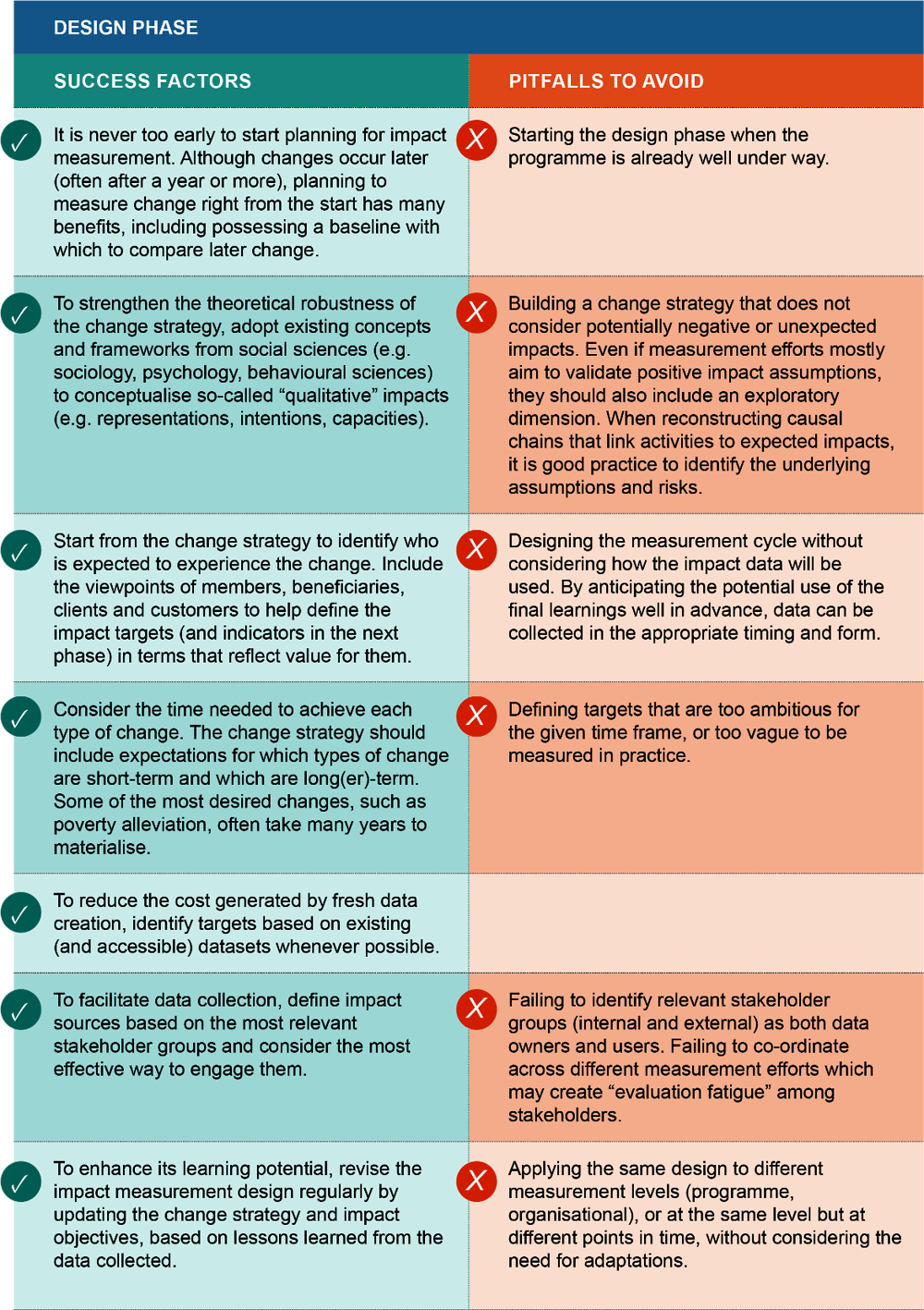

Infographic 1.4. provides an overview of the success factors and pitfalls to avoid during the design phase of the impact measurement cycle.

Infographic 1.5. Success factors and pitfalls to avoid in the design phase

References

[22] American Evaluation Association (n.d.), American Evaluation Association, https://www.eval.org/.

[2] Aps, J. et al. (2017), Maximise Your Impact: A Guide for Social Entrepreneurs, https://www.socialvalueint.org/maximise-your-impact-guide.

[10] Baudet, A. (2019), L’appropriation des outils d’évaluation par les entreprises sociales et associations d’intérêt général : apports d’une approche sociotechnique pour la conception des outils d’évaluation d’impact social.

[11] Besançon, E. and N. Chochoy (2019), “Mesurer l’impact de l’innovation sociale : quelles perspectives en dehors de la théorie du changement ?”, RECMA, pp. p. 42-57, https://www.cairn.info/revue-recma-2019-2-page-42.htm.

[6] Better Evaluation (n.d.), , https://www.betterevaluation.org/frameworks-guides/managers-guide-evaluation/scope-evaluation/describe-theory-change.

[13] Center for Social Impact Strategy (n.d.), , https://csis.upenn.edu/?s=theory+of+change&swpmfe=372a067946b75fd8fb50c7d833cf858b.

[7] Change the Game Academy (n.d.), A framework for a theory of change, https://www.changethegameacademy.org/shortmodulepage/theory-of-change-toc-2/a-framework-for-a-theory-of-change-in-word-and-pdf/.

[20] European Commission (2006), Evaluation methods for the european union external assistance, https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/dcdndep/47469160.pdf.

[21] European Evaluation Society (n.d.), European Evaluation Society, https://europeanevaluation.org/.

[35] GECES (2015), Proposed approaches to social impact measurement in European Commission legislation and in practice relating to EuSEFs and the EaSI - Publications Office of the EU, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/0c0b5d38-4ac8-43d1-a7af-32f7b6fcf1cc (accessed on 28 June 2021).

[26] Gomez, L. et al. (2011), An Outcomes-Based Assessment of Quality of Life in Social Services, Springer Science+Business Media B.V., http://sid.usal.es/idocs/F8/ART20444/Outcomes_Based_Assessment_of_QoL.pdf.

[19] HIGGS, A. et al. (2022), Methodological Manual for Social Impact Measurement in Civil Society Organisations, https://measuringimpact.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Methodological-Manual-English.pdf.

[33] IMP (2023), Impact Management Platform: Manage impact for organisations.

[5] Impact Management Platform (n.d.), , https://impactmanagementplatform.org/actions/identify/.

[25] Institut Català d’Assistencia (2009), Manual de Applicacion de la Escala GENCAT de Calidad de vida.

[31] INTRAC (2017), Theory of Change, https://www.intrac.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Theory-of-Change.pdf.

[9] Learning for Sustainability (n.d.), , https://learningforsustainability.net/evaluation/theoryofchange.php.

[34] Martínez, A., G. Gaggiotti and A. Gianoncelli (2021), Navigating impact measurement and management – How to integrate impact throughout the investment journey, EVPA, https://www.evpa.ngo/sites/www.evpa.ngo/files/publications/EVPA_Navigating_IMM_report_2021.pdf.

[15] Neelands, J. and B. Garcia (2023), Evaluation for Change, https://www.culturehive.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Evaluation-for-Change-Framework.pdf.

[24] OECD (2023), Buying social with the social economy: OECD Global Action “Promoting Social and Solidarity Economy Ecosystems, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2023/19, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c24fc.

[27] OECD (2023), Philanthropy for Social and Emotional Learning, https://www.oecd.org/dev/development-philanthropy/Philanthropy-for-social-emotional-learning_OECD.pdf.

[1] OECD (2023), Policy Guide on Social Impact Measurement for the Social and Solidarity Economy, Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/270c7194-en.

[4] OECD (2021), “Social impact measurement for the Social and Solidarity Economy”, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2021/05, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d20a57ac-en.

[32] OECD (2012), Evaluating Peacebuilding Activities in Settings of Conflict and Fragility: Improving Learning for Results, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264106802-en.

[23] OECD DAC Network on Development Evaluation (n.d.), Evaluation Criteria, https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm.

[28] Poverty Stoplight (n.d.), Poverty Stoplight, https://www.povertystoplight.org/en/what-it-is.

[18] Reed, M. and R. Curzon (2015), “Stakeholder mapping for the governance of biosecurity: a literature review”, Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, Vol. 12/1, pp. 15-38, https://doi.org/10.1080/1943815x.2014.975723.

[17] Rockwool Foundation (2020), Building Better Systems, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/632b07749e5eec1fde3510bd/t/63610361fe3ff372e1d9b33e/1667302288381/Building%2BBetter%2BSystems%2Bby%2Bthe%2BROCKWOOL%2BFoundation.pdf.

[12] Social Impact Navigator (n.d.), , https://www.social-impact-navigator.org/planning-impact/logic-model/components/.

[14] Social Impact Toolbox (n.d.), , https://www.socialimpacttoolbox.com/.

[8] ThinkNPC (n.d.), , https://www.thinknpc.org/resource-hub/ten-steps/#step1.

[30] United Nations Development Group (2017), UNDAF Companion Guide: Theory of Change, https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/UNDG-UNDAF-Companion-Pieces-7-Theory-of-Change.pdf.

[29] UNSTAT (n.d.), , https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/.

[3] VISES (2017), Advocacy position for a co-created assessment of the social impact of social entrepreneurship, http://www.projetvisesproject.eu/IMG/pdf/vises_noteenjeux_en_relecture.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2020).

[16] VisibleNetwork (n.d.), Ecosystem Mapping, https://visiblenetworklabs.com/ecosystem-mapping-a-great-tool-for-social-impact/.

Notes

← 1. This approach is inspired by the vision expressed by representatives of the European social economy (GECES, 2015[35]; VISES, 2017[3]). It is also closely aligned with the main international standards emerging from the private investment and for-profit business sectors (IMP, 2023[33]; Martínez, Gaggiotti and Gianoncelli, 2021[34]).

← 2. Going forward, the report only refers to change strategy at the programme level – which itself may need to incorporate different strategies at the project level. Large social economy entities (e.g. international NGOs running a diverse portfolio of activities across many themes and countries) typically deal with several levels.

← 3. A “theory of change” is a method that explains how a given activity is expected to lead to a given change, drawing on a causal analysis based on available evidence. The approach pushes organisations to identify who needs to change (individuals, groups or relationships in society), what is expected to change (for instance, beneficiaries’ situation, behaviour or perceptions), and how the change could occur (i.e. how the planned activities will lead to expected results). The approach encourages critical thinking by defining and testing critical assumptions, which helps to clarify the organisation’s role in contributing to change (OECD, 2012[32]; United Nations Development Group, 2017[30]). It is increasingly considered an essential practice within social development (INTRAC, 2017[31]).

← 4. Sometimes called “outcome mapping” (see, for example, https://www.betterevaluation.org/methods-approaches/approaches/outcome-mapping).

← 5. When the impact map is created using existing evidence, it is called “outcome harvesting” https://www.betterevaluation.org/methods-approaches/approaches/outcome-harvesting.

← 6. See, for instance: https://happymuseum.gn.apc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/HM_1_Story_of_Change_Feb2016.pdf.

← 7. Depending on the situation, this approach is also variously referred to as a “causal model”, “causal pathway” or “causal tree”.