The final stage of the measurement cycle features three main steps: consulting with stakeholders, creating a report using a template, and communicating the results internally and externally. Often sacrificed due to budget and skill limitations, this phase is central to understanding social change mechanisms, continuously improving operations and motivating people working on the frontlines.

Measure, Manage and Maximise Your Impact

3. Learn and share

Abstract

The final stage of the measurement cycle features three main steps: consulting with stakeholders about the results, creating a report using a template, and communicating and disseminating the results and conclusions (Hehenberger, Mair and Metz, 2019[1]). This learning and sharing phase begins with the social economy entity seeking to present, discuss and gain internal agreement on the results, conclusions and recommendations deriving from the data analysis conducted during the impact measurement cycle. When internal agreement has been reached, the social economy entity may involve a wider array of stakeholders (i.e. its members, board, funders and even beneficiaries) in considering and developing the main learning points and opportunities of the impact evidence. As a final step, the entity may create an impact report, using a (more-or-less) customised reporting template, to share the insights with its own stakeholders or the wider social economy ecosystem.

This phase is increasingly seen as a critical and imperative stage in the measurement cycle, although it often falls outside the budget (in terms of financing, time or human capital), especially for smaller social economy entities. This is partly due to a historical focus on accountability, where the goal has been to determine efficiency and effectiveness, and measurement is seen as a “necessary evil” to justify funding (Ebrahim, Battilana and Mair, 2014[2]). As the field becomes more mature, there is a greater realisation of how “learning” is absolutely necessary to strengthen the social economy’s impact and long-term development. Shifting the emphasis to “improving alongside proving” implies meeting social economy entities at different stages of their journey, by providing appropriate measurement methods, not over-prescribing and providing opportunities for (qualitative) deep dives into the data (Budzyna et al., 2023[3]). While learning efforts would technically always be relevant at the end of any measurement cycle, they often remain “optional” because of the resources that are realistically available. Learning remains central to motivating people on the frontlines to do this work (Beer, Micheli and Besharov, 2022[4]). It is at the heart of understanding social change mechanisms, continuously improving operations and maximising impact, but it requires training and skill development (Hehenberger, Buckland and Gold, 2020[5]).

Consult with internal and external stakeholders about results

Consulting with internal and external stakeholders about the results helps strengthen and validate the findings, conclusions and recommendations. This step primarily involves setting up meetings to present and discuss the results of the data analysis, providing an opportunity for stakeholders to question and challenge whether the results match their pre- and post-conditions and address all the identified learning needs. For example, the social economy entity may present the alleged results from an intervention to the beneficiaries for confirmation that these can indeed be attributed to the intervention, or that the value assigned to the outcome is accurate.

The social economy entity may sometimes wish to co-construct these conclusions and recommendations with key stakeholders, such as beneficiaries and funders. In this scenario, the impact-measurement lead will either meet stakeholders independently or as a group, or request their written or electronic feedback on the results. Whatever the format, the point should always be to engage stakeholders in identifying the conclusions and recommendations. This will likely involve directed reflection and recording responses on a series of questions: “What is the most insightful element of these results? What is unexpected, and why? What went wrong, and why? Where did we succeed? Where did we fail? How can we use this information to improve the intervention, organisational operations, relationships or processes? How might others use this information? How can we best share this information to reach audiences who might use it? In what format?” (Jancovich and Stevenson, 2023[6]). Doing this exercise with stakeholders from different groups often helps the social economy entity identify novel insights and ways of sharing them. Yet just like data-collection approaches, which may feature barriers to participation for certain groups, consultation may need to look different to engage different stakeholders.

The consultation process may also be subject to the constant tension of responding to different stakeholder needs and expectations. This tension resides most often in the need to balance internal stakeholders’ learning needs (i.e. deriving insight about coherence, reliability and strategic orientation to improve decisions) with external stakeholders’ requests for accountability (i.e. providing credible results that can withstand the test of independent verification). This is especially true where resources are scarce, as happens with many social economy entities. The impact-measurement lead will still need to take the final decision concerning the results, conclusions and recommendations that will best address the entity’s legally mandated and voluntarily agreed reporting objectives (Molecke and Pinkse, 2020[7]).

Choose a reporting framework

There exist many available reporting frameworks covering social, environmental and governance aspects, which can be applied to the social economy. Social economy entities may decide to voluntarily embrace a harmonised reporting and disclosure approach to gain independent certification, such as B Corp Certification.1 However, wider environmental, social and governance2 frameworks do not serve the same purpose as impact measurement: their rationale is to identify and manage risks to increase profitability – not to provide an understanding of the value and extent of change occurring (Barman, 2007[8]). Social economy entities must often deal with multiple reporting obligations in order to meet the demands of different stakeholders at both the programme and organisational levels. Wherever possible, they would be well advised to work with internal and external stakeholders early on, to identify how they can align the reporting frameworks (i.e. shared indicators, templates) across these multiple levels.

Besides abiding by legal and voluntary reporting commitments, social economy entities may choose to create their own reporting framework or adopt a freely available template, like the Social Reporting Standard.3 In many countries, legally recognised social economy entities (such as registered social cooperatives, social enterprises and non-profit organisations) must comply with mandatory reporting frameworks, depending on the national or local regulation. In Europe, social and worker cooperatives are actively sharing their social impact reporting practices and gradually converging towards a common approach (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Social reporting by European cooperatives

Cooperatives in countries like France, Italy, Germany and Poland began developing their own ways of assessing social performance in the early 20th century. The European Confederation of Industrial and Service Cooperatives (CECOP) has been collecting good practices for social impact assessment that have been designed and tested by cooperatives. The data emerging from the social audits of worker and social cooperatives in Spain and Italy show they are major actors in advancing decent work, sustainability and social inclusion.

Having developed together the Balanç Social reporting tool, the Spanish Confederation and the Catalan Network on Solidarity Economy have been collecting data over the last decade from the social economy initiatives in Spain that have applied it. Originally conceived in Catalan, the tool has now been translated into Spanish, Basque and Galician. The goal is to ensure that 5-10% of respondents are audited each year, to guarantee the reliability of the data.

In Italy, all social enterprises (including social cooperatives) are required to prepare and publish annually a “social report” (Bilancio Sociale). The public regulation stipulates that this social report is a “reporting tool on the responsibilities, the behaviours and the social, environmental and financial results of an organisation’s activities”, whose aim is to offer stakeholders information that is not included in traditional financial reporting. The report must include several compulsory sections (related to methodology, statutory information, governance, personnel, objectives and activities, and financial statements) and other information (possibly including social and environmental impact). In 2020, about 16 000 Italian social enterprises and social cooperatives published a social report.

Source: Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali (2019), Decreto 4 luglio 2019, “Adozione delle linee guida per la redazione del bilancio sociale degli enti del Terzo Settore”, Gazzetta Ufficiale delle Repubblica Italiana; (Repubblica Italiana, 2019[9]); (CECOP, 2021[10]).

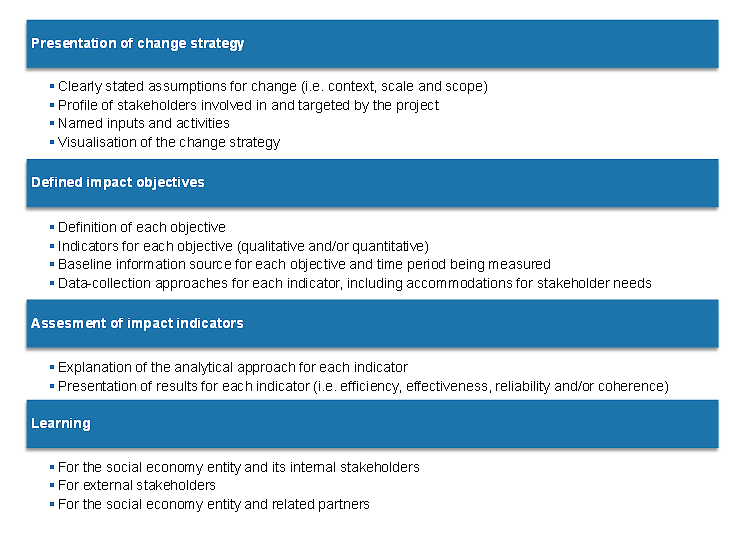

Taken together, these existing reporting initiatives allow setting a template for impact reporting in the social economy that supports robust and transparent communication of impact evidence. See Infographic 3.1. for an example. At minimum, impact reports should present their change strategy (where possible, in visual form); set out clearly defined objectives, relevant indicators and data sources for measuring those objectives; assess performance on those indicators (i.e. efficiency, effectiveness, reliability and/or coherence), especially in relation to identified learning needs; provide stakeholder perspectives on the featured outcomes; and include some insights into the entity’s change strategy, organisational or evaluation processes, and/or collective evidence about the strength of the social economy.

Infographic 3.1. Template for impact reporting

Note: This template represents the content that would be expected in an impact report. Its presentation and ordering will be more of a creative process for the social economy entity, based on its identity, values and strategy.

Source:OECD.

For social economy entities, communicating the findings of the impact-measurement report serves two purposes: accountability (to justify investment in the organisation, as well as the trustworthiness of its beneficiaries and communities) and learning (to disseminate the findings, operating principles and outcomes of the intervention to other entities and institutions interested in the same social issue). Typically, five categories of information need to be present across all sections of the impact report: 1) objectives and expectations; 2) relevant measures linked to the objectives; 3) performance results; 4) integrated stakeholder perspectives; and 5) risks (Gelfand and Budzyna, 2022[11]).4 See Box 3.2 on weaving qualitative data into quantitative reporting.

Box 3.2. Weaving qualitative data into quantitative reporting

The most effective approaches to impact measurement entail balancing quantitative and qualitative data to achieve the two distinct, but interconnected, purposes. Quantitative data, which offer information about the impact achieved and the degree of change, are the most popular, owing to the advanced methodologies and standardised indicators available. Qualitative data provide insights into the “how” and the “why” of change. They are most often used to: 1) provide context; 2) illustrate how change is happening, or what is preventing change from happening; or 3) understand the rationales and reflections of key stakeholders. Qualitative data can take the form of interviews, stories or narratives, such as a structured case study detailing a participant’s personal experience of an intervention, a video showing the intervention in process and how people reacted, or photographs of different stages along the intervention.

While qualitative data are traditionally considered less “objective” and harder to interpret than quantitative data, considerable work has gone into improving their rigour, consistency and dependability to capture and convey impact (Gioia, Corley and Hamilton, 2013[12]). As such, qualitative data may be more conducive to internal learning, as they help: 1) inspire people to connect to social problems; 2) communicate abstract ideas in accessible ways; 3) introduce a new topic into public dialogue; and 4) share lessons about a programme’s strengths and weaknesses (Rockefeller Foundation, 2014[13]). They are therefore especially useful for social economy entities, which can rely on the measurement process to learn about their intervention, possible areas for improvement and their stakeholders’ needs. Qualitative data can be used to elaborate on the context, supporting the quantitative results by providing additional details and evidence of the change being created. This yields a broader picture of the impact results and offers different stakeholders opportunities to engage with them meaningfully.

When qualitative data are used to illustrate the change occurring or obstacles to change, analysis relies on more extensive data collection, such as interviews, open-ended questionnaires or focus groups. The data can be thematically analysed to pinpoint why or how an intervention had the observed result. Reports then typically focus on presenting and explaining the results, using different media depending on the intended audience and purpose. Results may be presented in written, video or photographic form, using visuals or direct quotations from participants. Qualitative data can be included in regular quarterly reports requested by funders, within regular monthly newsletters produced by the social economy entity or as a regular feature on the website, which can then be shared on social media (see Box 3.3 and Box 3.4).

Box 3.3. Oxfam: Illustrating change using “impact stories”

Oxfam is an international charity with a mission to overcome poverty by fighting against the conditions and inequalities that create it. It offers relief services, ranging from water sanitation and emergency response to fighting for women’s rights and food provision. As of 2023, it was operating in 86 countries. This requires the organisation to enact a wide range of activities and projects tailored to specific regions.

As a way of providing deeper insight into these varied projects and activities, Oxfam has workers write “Impact stories” for its website. The stories illustrate how activities are leading to change, using first-person accounts of the work being done. For example, a project manager in Indonesia explains how she helps build communities that are resilient to drought by teaching local women about climate concepts. The format allows her to elaborate on how she teaches adaptive farming techniques and the plant choices that are more resistant to drought, such as sorghum.

Oxfam’s annual reports showcases impact stories, video interviews and testimonials from the whole confederation.

Source: (Oxfam, n.d.[14]).

Communicate the impact evidence

Most social economy entities need to communicate and disseminate impact evidence, conclusions and results to both internal and external stakeholders, as well as the broader social economy system. A social economy entity may have determined each stakeholder’s demands for impact reporting while identifying the learning needs for the social impact measurement cycle. Alternatively, it can reference the stakeholder map to ensure it communicates with all relevant stakeholders in an appropriate and relevant manner. Ideally, the entity will utilise the impact evidence to ensure that internal stakeholders can learn and adapt when necessary, and that external stakeholders have robust and transparent evidence that justify its resources and actions. Moreover, the impact evidence will help the social economy entity gain visibility and recognition. It is good practice to define a dissemination strategy that identifies the stakeholders targeted, the message the entity wishes to convey, and the most suitable channel and frequency of communication (Higgs et al., 2022[15]).

Box 3.4. Reporting beneficiary testimonials as evidence of impact context

Dementia UK has started publishing a summary video of its impact report that uses beneficiaries' testimonials as further evidence. The animation provides a brief overview of some of the main achievements across the financial year, along with quotes that demonstrate the impact on beneficiaries. By showing the results in different formats, the organisation hopes to engage a wider range of stakeholders in discussions about the importance of learning about dementia, and to spread knowledge about how best to care for those living with it.

The entity shares the animation in an email to supporters and on social media to raise awareness of its services for families affected by dementia and encourage people to donate, fundraise, volunteer or campaign. It includes a call to action to get involved and contact details to reach its clinical services. The animation is also useful for internal teams, such as fundraising staff, who can use it as a source of key statistics and feature quotes from beneficiaries in supporter-facing materials.

Source: (Dementia UK, n.d.[16]).

Reporting for learning means communicating impact results as a means to derive insight and strategic orientation. It primarily involves using the data to understand the activities and mechanisms that are creating or hindering the intended results (Hehenberger, 2023[17]). This entails working closely with stakeholders (such as employees and beneficiaries) to reflect honestly on the results and ways to improve them (for example, by looking at areas of failure alongside strengths, or pooling data from various entities to learn about a problem’s interconnections and possible solutions). In Lithuania, the “Green Impact Measured” programme has created a website to report on its findings regarding ways to measure sustainability consistently and systematically. By presenting the information in a series of reports, open-house events and case studies, the programme helps other social entrepreneurs learn about the process of measuring sustainability (e.g. in terms of air quality or waste disposal) and improve their own practices.5

Reporting for accountability primarily involves using impact data to justify funding from external funders or public authorities. This style of reporting is most closely designed to meet contractual obligations, ensure safeguarding and justify resources. It can prove that resources are being spent as agreed and are generating an impact, or that the social economy entity deserves to be recognised through a specific legal status or other form of certification (Hehenberger, Mair and Metz, 2019[1]). It is less likely to lead to open conversations about the results, since relationships with stakeholders are more about compliance and transactional exchange (Beer, Micheli and Besharov, 2022[4]). Box describes how the cooperative sector in Italy has mandated the use of a particular reporting template, the “Social Report”, to ensure that organisations identifying as cooperatives uphold their contributions to the market and society.

Reporting for the social economy ecosystem involves contributing to public repositories of knowledge and offering evidence that can help the social economy develop. Knowledge repositories may be run by government bodies or academic institutions as a way of accumulating knowledge about both the positive and negative effects of different interventions on specific social issues. For example, the International Network for Data on Impact and Government Outcomes6 at the University of Oxford hosts datasets on current and upcoming project outcomes around the world. Other notable examples include the Impact Tank’s Wall of Solutions in France, which displays impact stories collected by social economy entities as inspiration or templates for their peers, and the Social Enterprise Evidence Space in Australia, which provides a well-curated catalogue of impact evidence, case studies, scientific articles and good practices. Through these knowledge repositories, social economy entities and other partners can find validated evidence to inform their own strategies, design better interventions, and identify relevant impact indicators and baseline sources. These data, in turn, can help social economy entities build compelling funding applications and advocate for more policy support.

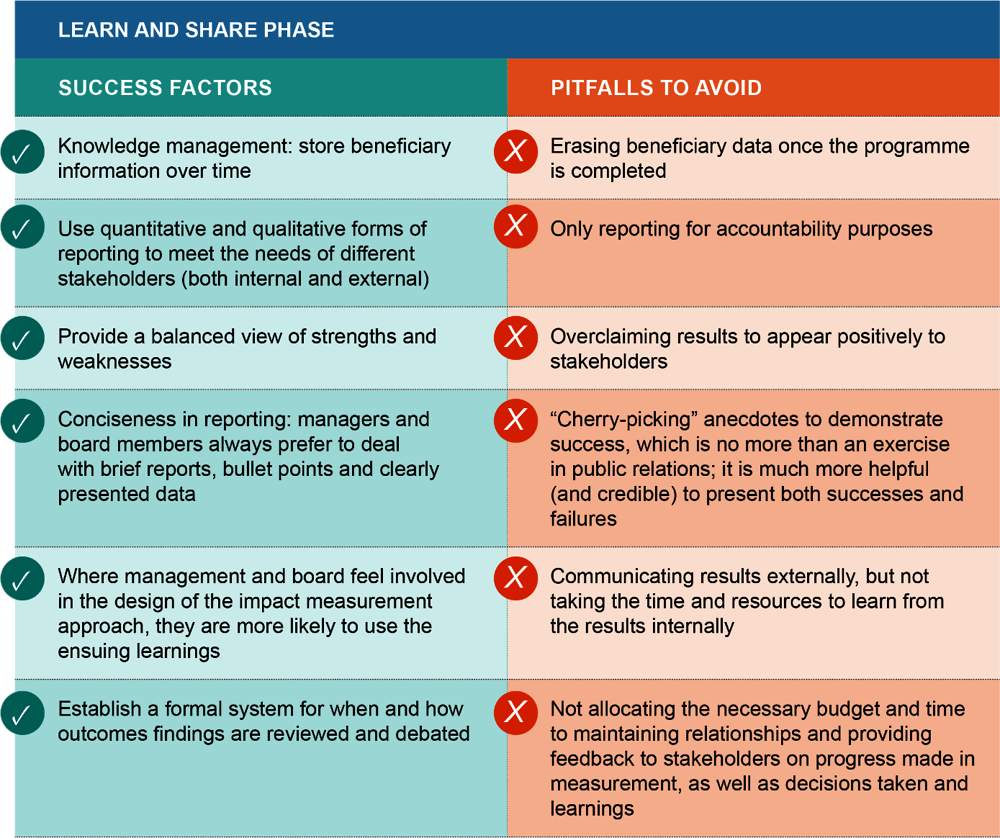

Infographic 3.2. provides an overview of the learning and sharing phase of the impact measurement cycle.

Infographic 3.2. Success factors and pitfalls to avoid in the learn-and-share phase

Source: OECD.

References

[8] Barman, E. (2007), “What is the Bottom Line for Nonprofit Organizations? A History of Measurement in the British Voluntary Sector”, VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol. 18/2, pp. 101-115, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-007-9039-3.

[4] Beer, H., P. Micheli and M. Besharov (2022), “Meaning, Mission, and Measurement: How Organizational Performance Measurement Shapes Perceptions of Work as Worthy”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 65/6, pp. 1923-1953, https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0916.

[3] Budzyna, L. et al. (2023), Ventures At The Helm, https://immjourney.com/wp-content/uploads/Ventures-At-The-Helm.pdf.

[10] CECOP (2021), Lasting impact. Measuring the social impact of worker and social cooperatives in Europe: focus on Italy and Spain, https://mcusercontent.com/3a463471cd0a9c6cf744bf5f8/files/b86afc11-1cab-13ff-afd3-d5ec375a8610/CECOP_lasting_impact_digital.pdf.

[16] Dementia UK (n.d.), Our strategy and annual reports, https://www.dementiauk.org/about-us/strategy-annual-reports/.

[2] Ebrahim, A., J. Battilana and J. Mair (2014), “The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations”, Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 34, pp. 81-100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2014.09.001.

[11] Gelfand, S. and L. Budzyna (2022), Elevating Qualitative Data in Impact Performance Reporting, https://www.sir.advancedleadership.harvard.edu/articles/elevating-qualitative-data-in-impact-performance-reporting.

[12] Gioia, D., K. Corley and A. Hamilton (2013), “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research”, Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 16/1, pp. 15-31, https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151.

[17] Hehenberger, L. (2023), “Prioritizing Impact Measurement in the Funding of Social Innovation”, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Vol. 21/2, pp. 74-75, https://doi.org/10.48558/SHQ7-VK20.

[5] Hehenberger, L., L. Buckland and D. Gold (2020), From Measurement of Impact to Learning of Impact - European Charitable Foundations’ Learning Journeys, Esade Entrepreneurship Institute, https://www.esade.edu/itemsweb/wi/EEI/Publications/report_foundations_web_full.pdf?_gl=1*1w65np9*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTg5MDE4MDYxOS4xNzA3ODI2NjY3*_ga_S41Q3C9XT0*MTcwNzgyNjY2Ni4xLjAuMTcwNzgyNjY2Ni4wLjAuMA.

[1] Hehenberger, L., J. Mair and A. Metz (2019), “The Assembly of a Field Ideology: An Idea-Centric Perspective on Systemic Power in Impact Investing”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 62/6, pp. 1672-1704, https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.1402.

[15] Higgs, A. et al. (2022), Worksheet of methodological tool for Social Impact Measurement in Civil Society Organisations, https://measuringimpact.eu/resources/training-materials/.

[6] Jancovich, L. and D. Stevenson (2023), Failures in Cultural Participation, Springer Nature, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/9fdd4d4c-f000-4ff8-88a6-e57829f33dca/978-3-031-16116-2.pdf.

[7] Molecke, G. and J. Pinkse (2020), “Justifying Social Impact as a Form of Impression Management: Legitimacy Judgements of Social Enterprises’ Impact Accounts”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 31/2, pp. 387-402, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12397.

[14] Oxfam (n.d.), How people can have food security, https://www.oxfam.org.uk/oxfam-in-action/impact-stories/climate-resilient-communities-indonesia/.

[9] Repubblica Italiana (2019), Gazzetta Ufficiale, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2019-08-09&atto.codiceRedazionale=19A05100&elenco30giorni=false.

[13] Rockefeller Foundation (2014), Digital storytelling for social impact, https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/Digital-Storytelling-for-Social-Impact.pdf.

Notes

← 2. Commonly referred to under the acronym “ESG”.

← 3. The Social Reporting Standard (www.social-impact-navigator.org/improving-social-impact/sharing-stories/social-reporting-standard/) was designed specifically for social economy entities. It does not require large amounts of data to be compiled and purposefully focuses on areas that help social economy entities learn about their processes and impact, rather than just be accountable for results. A free software and guide are available online in both German and English. The tool requires each social economy entity to provide information about its organisational leadership and finances, the interventions and activities it performs to create impact, details about its target groups, and any results it has been collecting. It allows entities to reflect on the assumptions embedded within their theory of change or logic model, results and risks.