A variety of tools are available for monitoring population mental health, ranging from administrative data to different types of survey questions. Although many OECD countries began collecting new or additional mental health data during COVID-19, official data producers were already active in this space well before the pandemic started. However, there is room for improvement by increasing the frequency of (survey) data collection, diversifying the types of indicators used to cover the full spectrum of mental health, and expanding the international harmonisation of existing measures. Here, data collectors could: (1) beyond screening tools focusing on symptoms of depression, expand use to those including symptoms of anxiety as outcome measures; (2) move towards collecting harmonised information on affective and eudaimonic aspects of positive mental health; and (3) explore using single-item questions on general mental health status across surveys.

Measuring Population Mental Health

2. Measuring population mental health: Tools and current country practice

Abstract

The frequent collection of population-level data on mental health outcomes is important for identifying populations at-risk for mental ill-health, for determining which socio-economic and other factors shape (and are shaped by) people’s mental health, and for designing effective prevention and promotion strategies. As outlined in Chapter 1, mental health is a multifaceted concept and exists beyond a binary distinction between the presence or absence of mental illness. Collecting data on both mental ill-health and positive mental health in population surveys and mental health assessments would yield a more complete picture of people’s overall mental health and help to better understand the drivers and policy levers associated with improving it.

However, the current lack of (internationally) standardised data on population mental health makes it difficult to assess the efficacy of different policy approaches across disparate contexts; standardising outcome measures is the first step in facilitating such analysis. This chapter outlines the tools available to data collectors, gives an overview of current data collection practices across OECD countries and offers suggestions for which outcomes to prioritise in international harmonisation efforts.

An analysis of responses to a questionnaire sent to official data producers in OECD countries in 2022 shows that all member states that answered are already active in this space. Prior to the pandemic, almost all OECD members were already collecting information on mental health outcomes in both health interviews and general household surveys, as well as via administrative data. COVID-19 has sparked additional interest in measuring population mental health, with many public agencies and statistical offices adding items to both new and existing surveys.

These existing data collections demonstrate the interest in, and relevance of, population mental health outcomes in a national statistics context. Yet there is room for improvement in several areas: the frequency of data collection; greater data availability across the full spectrum of both negative and positive mental health outcomes; and better harmonisation of measures across countries to improve international comparability.

Indeed, prior to the pandemic most mental health data were collected by countries on surveys that ran every four to ten years. While many introduced high-frequency surveys with mental health modules in the first two years of COVID-19, it is currently unclear whether these surveys will continue to be implemented moving forward. Further, although all statistical offices collect data on mental ill-health – with a particular focus on common mental disorders – general psychological distress and depressive symptoms tend to be captured through standardised screening tools, whereas measures of experiencing anxiety are less harmonised across countries. Data collection efforts for other mental conditions – such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, eating disorders, etc. – and for other aspects of mental health – such as suicidal ideation and mental health-related stigma – remain very uneven across countries. When it comes to positive mental health, cross-country comparative data are mainly limited to measures of life evaluation. Other aspects, such as affect and eudaimonia, are much less frequently collected as outcome measures, and when they are, the tools used are less likely to be standardised across countries.

The results of the OECD questionnaire suggest that existing data collection efforts are not capturing the full range of mental health outcomes – missing aspects of both mental ill-health as well as positive mental health. In order to capture these outcomes and collect frequent information on mental health, data collectors in OECD member countries could: (1) beyond screening tools focusing on symptoms of depression, expand use to those including symptoms of anxiety as outcome measures; (2) move towards collecting harmonised information on affective and eudaimonic aspects of positive mental health; and (3) explore using single-item questions on general mental health status across surveys.

Which tools are available for measuring population mental health?

While Chapter 1 focused on relevant types of outcomes (covering both mental ill-health as well as positive mental health) for data collectors interested in mental health, this chapter focuses mainly on the types of tools that can be used to measure these.

The broad tool types discussed in this chapter – some of which are sourced from administrative data, but the bulk of which come from household surveys – range from long survey modules to a battery of question items to single questions. Some tools can be used to capture aspects of either mental ill-health or positive mental health, while others are used only for specific types of outcomes. Each type of tool has its own advantages and disadvantages, requiring data collectors to select among them, depending on the needs and constraints of their specific contexts. The different tools are described below in order to provide a common understanding of the categorisation used in this report.

The chapter annexes contain in-depth information for readers interested in further details. Annex 2.A provides an overview of which specific tools are collected by each country, along with sample question framing and answer options. Annex 2.B lists full details, including question wording and scoring recommendations, for the most commonly used standardised instruments. More detailed reflections on the statistical quality of mental health survey measures are addressed in Chapter 3.

Tools sourced from administrative data

Administrative data can contain information on the use of mental health services, diagnoses of mental disorders in clinical settings, as well as cause of death data from suicide and substance abuse (i.e. drug overdoses and alcohol abuse).

While all of these can be considered objective (i.e. not self-reported) and easy-to-collect proxies of mental ill-health, measurement challenges remain. For instance, measures of service use and medical diagnoses do not capture population outcomes, but rather only those who are willing and able to access health care services. Such measures can overestimate comparative levels or incidence rates in countries with good (and affordable) medical systems, awareness programmes and less stigma, where people are more likely to both seek and receive treatment. In addition, preventing ill-health necessitates tracking outcomes prior to, and following, engagement with the service sector. This report does not consider administrative statistics related to health care further, referring readers to (OECD, 2021[1]).

Data on causes of death due to suicide or substance abuse (which are commonly referred to as “deaths of despair” (Case and Deaton, 2017[2])) do capture mental ill-health outcomes at the population level. These measures can act as proxies for severe mental illness and addiction. While there are social and cultural reasons affecting suicidal behaviours – meaning that not all suicides are the direct result of a mental ill-health – living with mental health conditions does substantially increase the risk of dying by suicide (OECD, 2021[1]). However, the registration of suicide deaths is a complex procedure, affected by factors such as how intent is ascertained, who completes the death certificate, and prevailing norms and stigma around suicide, all potentially affecting the cross-country comparability of mortality records (OECD, 2021[1]).

A general limitation for all types of administrative data is that the additional socio-demographic data collected alongside are often limited to the age, sex, geographic region and potentially the race/ethnicity of the deceased. This constrains the ability to delve into the drivers of mental health and to identify relevant socio-economic, environmental and relational risk and resilience factors.

Tools sourced from household surveys

In contrast to administrative data, population surveys generally contain information on respondents’ material conditions (e.g. income, wealth, labour market outcomes, housing quality), quality of life (e.g. physical health, educational attainment, environmental quality) and relationships (e.g. social connections, trust, safety). Population surveys can have a specific content focus, such as a health survey, or a more general scope, such as general social surveys. These surveys are conducted at the household level, with more in-depth modules on employment, health (including mental health), education, etc., administered to selected household members. Having a full range of well-being covariates is important to understand how mental health is impacted by, and how it in turn influences, other areas of people’s life. Furthermore, tracking (and eventually achieving) equity in mental health outcomes requires disaggregation by important socio-demographic categories.

Tools that have been included in household surveys to assess specific mental health outcomes range from single-item questions to standardised batteries of items. A brief description of each can be found below, with full details in Annex 2.A and Annex 2.B.

Questions about previous diagnoses – This refers to single-item questions about whether an individual has been diagnosed with a mental health disorder (e.g. major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, or other mental health conditions) by a health care worker, either in the past 12 months or over the course of his/her lifetime. These questions typically have yes/no answers and are not standardised across countries. For full details, see Table 2.6. Examples include:

“Have your mental health problems ever been diagnosed as a mental disorder by a professional (psychiatrist, doctor, clinical psychologist)? Yes / No”.

“Have you EVER been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had ...Any type of depression? Read if necessary: Some common types of depression include major depression (or major depressive disorder), bipolar depression, dysthymia, post-partum depression, and seasonal affective disorder. Yes / No”.

Questions about experienced symptoms – This refers to single-item questions about symptoms of mental disorders experienced in the past 12 months or over the course of an individual’s lifetime, without explicitly referring to a diagnosis by a medical professional. These questions typically have yes/no answers and are not standardised across countries. For full details, see Table 2.7. Examples include:

“During the past 12 months, have you had any of the following diseases or conditions? Depression (“Yes / No”).

“Have you ever suffered from chronic anxiety? ("Yes / No").

“Do you have a mood disorder? Yes / No”.

Questions about suicidal ideation and suicide attempts – These are (usually) single-item questions about a respondent’s experience of suicidal ideation, self-harm behaviours or suicide attempts. These questions typically have yes/no answers and are not standardised across countries. Recall periods refer to an individual’s lifetime, the last 12 months, the past two weeks, or “during COVID”. For full details, see Table 2.8. Examples include:

“Have you seriously contemplated suicide since the COVID-19 pandemic began? Yes/No”.

“Sometimes people harm themselves on purpose but they do not mean to take their life. In the past 12 months, did you ever harm yourself on purpose but not mean to take your life? Yes/No”.

“Have you ever attempted suicide? Yes/No”.

“Did you stay in a hospital overnight or longer because you tried to kill yourself? Yes/No”.

Questions about general mental health status – These refer to single-item questions on how respondents rate their mental health overall, and thus capture both components of ill-health and positive mental health. Questions are not standardised across countries and differ in terms of question wording, response options and recall period. For full details, see Table 2.9. Examples include:

“In general, how is your mental health? Excellent / Very good / Good / Fair / Poor”.

“Has your mental health/well-being been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic during the last 12 months?”

“On a scale from 1 to 10 can you indicate to what extent you are satisfied with your mental health? A score of 1 refers to completely dissatisfied and a 10 to completely satisfied”.

“Does your mental state interfere with your daily life at work? your family life? Yes / No”.

Positive mental health indicators – This refers to questions pertaining to the various aspects of positive mental health: life evaluation, affect (summary affect scales, and batteries of questions on positive, negative or mixed affect), eudaimonia (questions about quality of life, whether life is worthwhile or meaningful), as well as standardised positive mental health composite scales (combining different dimensions of positive mental health, prioritising positive over negative affect, and sometimes adding a social well-being component). In some instances, positive mental health indicators are single-item questions that vary across countries and surveys, while in others they are standardised batteries of questions. Standardisation across countries varies, with only life evaluation questions and positive mental health composite scales being consistently phrased. For full details, see Table 2.10. Specific question item phrasing and scoring suggestions for standardised composite scales can be found in Annex 2.B.

Screening tools – These refer to multi-item instruments designed to screen respondents for symptoms (rather than for diagnoses) of mental health conditions. These tools were initially developed in clinical settings to screen for common mental disorders to identify individuals who may be at risk and to flag them for further screening and potential diagnosis. They can be interviewer-led or self-administered and focus either on general psychological distress or on specific mental health conditions such as major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder (and sometimes a combination of the two), alcohol use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders and so on. These tools are considered “validated” in that they have been psychometrically tested for their validity (against the gold standard of structured interviews or diagnoses), sensitivity (the probability of correctly identifying a patient with the condition) and reliability (the measures produce consistent results when an individual is interviewed under a given set of circumstances) (refer to Chapter 3 for an extended discussion of statistical quality). A wide variety of screening tools are available, ranging from very short screeners of two items to longer instruments covering 20 items or more. The focus of questions varies between screening tools: all cover the frequency of experiencing (mostly negative) affect (i.e. feeling low, feeling nervous, feeling worthless), with some also including somatic symptoms (i.e. changed appetite, trouble sleeping) and/or functional impairment due to emotional distress (e.g. disturbance in daily activities, not being able to concentrate, not being able to stop worrying). Screening tools also differ in terms of reference period for symptoms, ranging from the past week to the past month; however, none are able to measure lifetime prevalence. Given these differences between screening tools, they are therefore not always directly comparable and should not be used interchangeably for international comparisons. Item scores are typically summarised in a summary index, with the final score being used either as a continuous measure of mental ill-health or to assess the risk of a common mental health conditions using a validated cut-off score. For full details, refer to Table 2.5. Exact question item wording and scoring recommendations for the most frequently used screening tools can be found in Annex 2.B.

Structured interviews – Structured interviews are considered the gold standard for measuring mental disorders (often both on a lifetime and 12-month basis). They provide a standardised assessment based on the internationally agreed definitions and criteria of recognised psychiatric classification systems and have strong diagnostic reliability and psychometric properties to determine whether or not a respondent has the condition of interest (Mueller and Segal, 2015[3]; Burger and Neeleman, 2007[4]).1 They are administered by trained interviewers, with close-ended and fully scripted questions and standardised scoring of responses (Ruedgers, 2001[5]). Structured interviews approximate assessments conducted by mental health professionals and in this way can identify populations at risk for mental health conditions even if these individuals have not been diagnosed by a health care professional. For additional information on the most commonly used structured interview, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), see Table 2.4 and Annex 2.B.

Additional mental-health related topics – This category refers to questions on any other relevant topics, including the use of mental health medication and services, the mental health of children and young people in the household, loneliness and stress, resilience and self-efficacy, attitudes towards mental health including stigma and literacy, and questions on unmet needs. For additional information, see Table 2.11.

Trade-offs between tool types

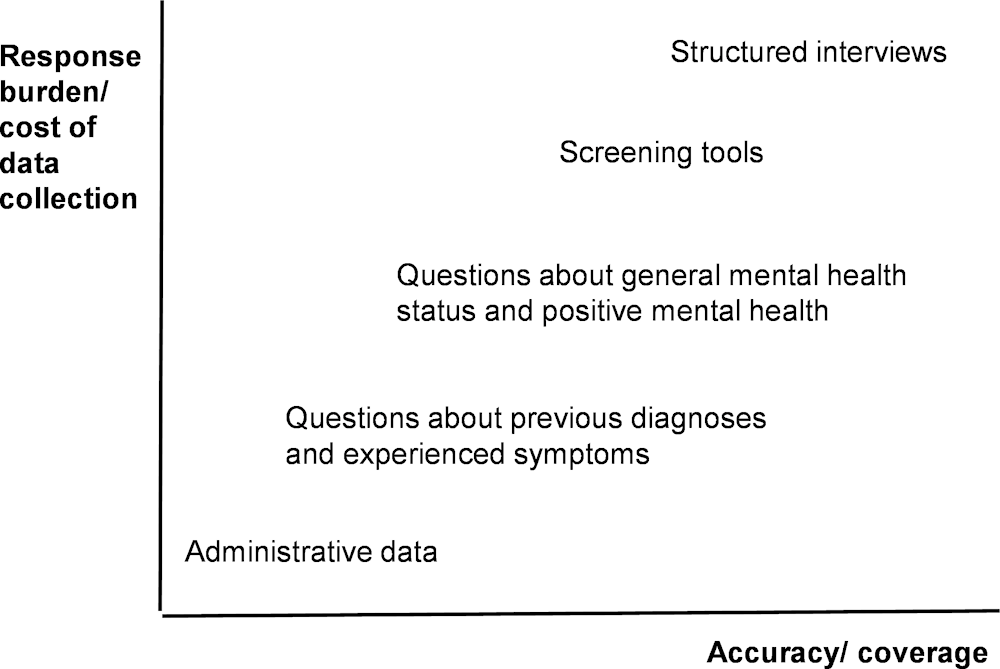

All tools imply trade-offs in terms of response burden/ease and cost of data collection, accuracy and coverage (Figure 2.1, Table 2.1). Response burden is a direct function of how much time an individual needs to spend to provide information on their mental health status and how much stress is caused by providing this information. Accuracy refers to the sensitivity of a tool in correctly identifying a person with a mental health condition, whereas coverage entails whether the measure in question is applied to the full (adult) population.

By way of illustration, administrative data have a low response burden: they do not require answers from individual respondents and are routinely collected within a country’s data infrastructure. Yet statistics on deaths of despair focus only on the extreme end of mental ill-health and are further complicated by the fact that not all deaths of despair may be the culmination of a mental disorder. Furthermore, unlike household surveys, only those who were in contact with the health care system are captured by administrative records of diagnoses in a clinical setting.2

For household surveys, both the response burden and accuracy increase the longer and more specific a tool is: whereas single questions about experienced symptoms or a person’s general mental health status are short and easy to answer, they do not consider the nature or severity of symptoms, or the type of mental health condition, and have not been benchmarked against diagnostic criteria. Screening tools have been validated against the gold standard of structured interviews and are, depending on the specific tool used and the number of items covered, still relatively low cost in terms of response burden. However, they do not constitute a diagnosis from a health care professional and can only identify people likely at risk of disorders. Screening tools are validated against clinical diagnoses, and are thus designed to maximise likeness to diagnostic interviews to the extent possible. Still, when calibrating tools and cut-off scores, there is a trade-off between sensitivity (correctly identifying the presence of a mental health condition) and specificity (correctly noting the absence of a mental health condition), and researchers often prioritise the former rather than the latter, leading to slight overestimates by design (see Box 3.3 and Section 3.3.1 for a more detailed discussion). Finally, the majority of tools included in both household surveys and administrative data focus on mental ill-health; the only exceptions are household survey questions about general mental health and positive mental health.

The difference in question framing and item length – between structured interviews, screening tools and single-item questions on experienced symptoms or received diagnoses – can lead to different estimates of prevalence for the same reported outcome measure (Box 2.1). This speaks to the need for the standardisation of tool type (and transparency about which tool was used) when comparing outcomes across countries, over time and across population groups: i.e. mixing types of tools when commenting on outcomes like “share at risk for depression” or “share at risk for psychological distress” can lead to different estimates because of measurement differences, rather than because of differences in underlying mental health status (refer to Chapter 3 for an extended discussion of these themes).

Figure 2.1. Trade-off between response burden and accuracy for mental health measurement tools

Source: Adapted from a presentation given by Statistics Canada at the OECD conference “Well-being and mental health – towards an integrated policy approach” in December 2021.

Table 2.1. Advantages and limitations of different tools to measure mental health

|

Tool |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|---|---|---|

|

Administrative data (deaths of despair from suicide, drug overdose, alcohol abuse; diagnoses of common mental disorders in clinical care settings) |

• No response burden for individuals • Possibility to link across other administrative data (e.g. health system quality) • Less costly and more readily available than other types of data • Clinical care data can provide some insight into lifetime and specific time period (e.g. past 12 months) prevalence estimates for a range of ill-health conditions when other data sources are not available |

• Captures only those who sought treatment, were correctly coded by a health professional and are part of the reporting database • “Cause of death” data need to be correctly coded, do not account for suicide attempts or substance abuse not leading to death, and only capture the extreme end of mental ill-health • Often difficult, or even impossible, to interpret (without supplemental information) whether changes in diagnostic rates are driven by changes in underlying prevalence of mental health conditions or by other factors such as changes to affordability or accessibility of care, changes in help-seeking behaviour, etc. • Limited contextual information on well-being covariates |

|

Household surveys: questions about previous diagnoses |

• Relatively easy to understand for respondents • Minimal response burden (usually a single binary question) • Can provide both lifetime and specific time period (e.g. past 12 months) prevalence estimates for a range of ill-health conditions |

• Captures only those who sought treatment and were diagnosed by a health professional • Evidence that these questions lead to social desirability bias and higher rates of refusal and non-response (see Chapter 3) • Limited contextual information on the nature and severity of symptoms |

|

Household surveys: questions about experienced symptoms of mental health conditions |

• Minimal response burden (usually a single binary question) • Can provide both lifetime and specific time period (e.g. past 12 months) prevalence estimates for a range of ill-health conditions |

• Potential for confusion for respondents in terms of whether the question refers to an actual diagnosis or their self-assessment, though evidence suggests this type of tool is closely related to questions about previous diagnoses by health professionals • Limited contextual information on the nature and severity of symptoms |

|

Household surveys: questions on general mental health status |

• Relatively easy to understand for respondents • Minimal response burden (usually a single question) • Captures a respondent’s global evaluation of their mental state, and hence both ill-health and positive aspects |

• Over-reporting of true prevalence – not a complete assessment or an actual diagnosis, does not consider symptoms • Has not been validated against structured interviews or other diagnostic tools, no established threshold in the tools as to what constitutes at-risk respondents • Generally less of an existing evidence base, though available studies suggest this to be a useful measure • Limited contextual information on the nature and severity of symptoms or the type of mental health condition |

|

Household surveys: indicators of positive mental health |

• Relatively easy to understand for respondents • Minimal response burden (usually single or limited-item questions) • Focus on psychological and emotional well-being or flourishing • International measurement guidance exists (e.g. OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being) |

• No reference point of what (true and/or desired) prevalence should be • Recall period for questions typically ranges from day prior to past 4 weeks; cannot provide lifetime estimates |

|

Household surveys: screening tools |

• Easy to administer and reduced response burden compared to structured interviews • Have been validated against structured interviews or other diagnostic tools • Can capture undiagnosed conditions |

• Over-reporting of true prevalence – not a complete assessment or an actual diagnosis • Recall period for questions typically ranges from day prior to past 4 weeks; cannot provide lifetime estimates |

|

Household surveys: structured interviews |

• Approximates true prevalence – near gold standard • Can capture undiagnosed conditions • Extensive contextual information of the respondents’ lives can be taken into account |

• Very complex to develop and administer, including interviewer training • Many questions for people who have symptoms • Lack of survey measurement tools available to map to most up-to-date diagnostic guidelines (DSM-5) |

Source: Adapted from a presentation given by Statistics Canada at the OECD conference “Well-being and mental health – towards an integrated policy approach” in December 2021.

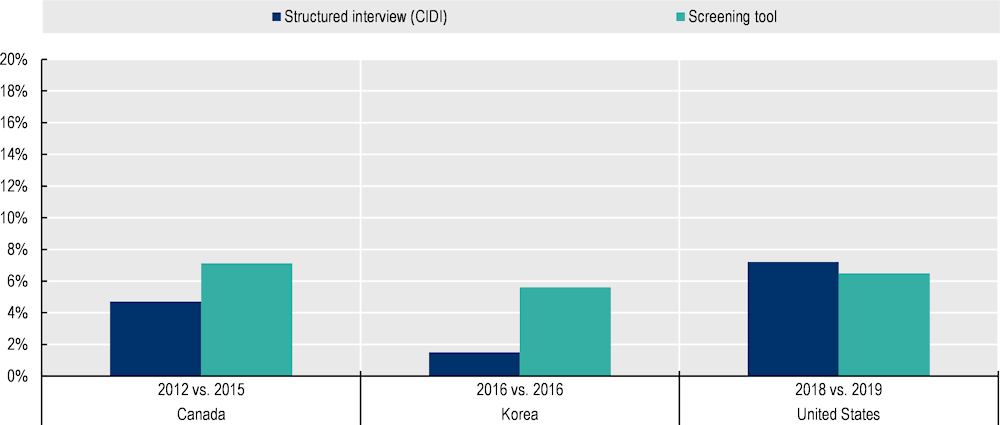

Box 2.1. Prevalence rates vary depending on the measurement tool used

Prevalence rates for specific mental health conditions will vary – at times substantially – depending on the type of tool used to create the estimate. Screening tools are likely to overstate population level prevalence of mental disorders by design. They were developed in clinical settings to identify individuals at risk for common mental disorders, who can then be flagged for further observation and actual diagnoses – some of whom may not end up being diagnosed or needing further treatment (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2021[6]; Topp et al., 2015[7]). In contrast, questions that require individuals to report whether they have been diagnosed with a mental disorder by a health care professional in the past, or currently live with a specific disorder, focus on those in touch with the health care system and are therefore likely to understate population prevalence.

On the first point, Figure 2.2 below shows that screening tools may overestimate population prevalence as compared to structured interviews. The figure shows national estimates of the same outcome measure – prevalence for major depressive disorder (MDE) – in three OECD countries as measured by CIDI, a structured interview, and by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), a screening tool. (The version of the PHQ varies by country: PHQ-9 in Canada and Korea, PHQ-2 in the United States. Refer to Annex 2.B for the specific items included in each iteration.) While both the CIDI and screening tools are used in different surveys within each country, implying that care should be taken in making direct comparisons, generally prevalence of MDE as measured by the CIDI is lower than that measured through screening tools. The exception is the United States, which also shows the smallest difference between the estimates. This may be in part because many mental health survey tools were first developed, and subsequently extensively validated, in the United States, making the calibrations between different tools more precise.

Figure 2.2. Screening tools typically show greater prevalence of major depressive disorder than do structured interviews

Note: For all three countries, the structured interview used is the CIDI, which is used to measure the prevalence of Major Depressive Episodes (MDE) over the past 12 months. In Korea, these estimates are adjusted for age and sex. In Canada and the United States, these estimates are nationally representative for the 15+ and 18+ population, respectively. The validated screening tool used by Canada is the PHQ-9 (MDE defined as having a score >= 10); the PHQ-9 is used by Korea (being at risk for depression is defined as having a score >= 10; although not described by KOSIS, Korea’s statistical service, as a risk for MDE, this same scoring convention is used by Canada to measure MDE); and the PHQ-2 is used by the United States (symptoms of a depressive disorder are defined as having a score >= 3). The PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 both have a reference period of the past 2 weeks. For the United States, the PHQ-2 measures the share with symptoms of a depressive disorder, rather than experience of MDE. Refer to Annex 2.B for more information on individual screening tools.

Source: Structured interview data for Canada come from Statistics Canada (2013[8]), Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health, 2012, The Daily, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/130918/dq130918a-eng.htm; PHQ-9 data for Canada are derived from Dobson, K. et al. (2020[9]), “Trends in the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders among Canadian working-age adults between 2000 and 2016”, Health Reports, Vol. 31/12, pp. 12-23, https://doi.org/10.25318/82-003-X202001200002-ENG; Structured interview data for Korea come from KOSIS (n.d.[10]), Annual prevalence of mental disorders (adjusted for sex and age) (database), Korean Statistical Information Service, https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=117&tblId=TX_117_2009_HB027&conn_path=I2; PHQ-9 data for Korea come from KOSIS (KOSIS, n.d.[11]), Depressive disorder prevalence (database), National Health and Nutrition Survey, Korean Statistical Information Services, https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/sub01/sub01_05.do#none; Structured interview data for the United States come from SAMHSA (2019[12]), Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (database), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf; PHQ-2 data for the United States come from the National Center for Health Statistics (2021[13]), Estimates of Mental Health Symptomatology, by Month of Interview: United States, 2019 (database), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/mental-health-monthly-508.pdf.

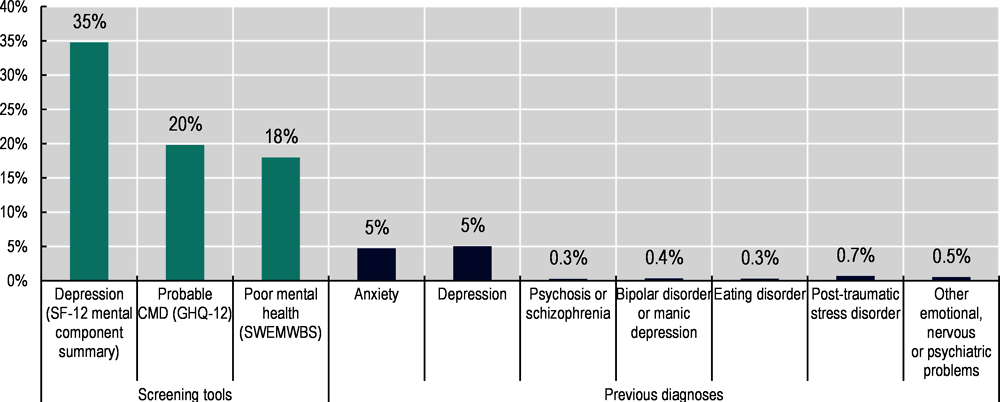

On the second point, Figure 2.3 shows that, based on answers to screening tools, the share of the population reporting ever having received a diagnosis for a given mental disorder is much lower than the share deemed to be at risk for poor mental health conditions; this is often a function of affordability and access to health care, along with stigma and mental health illiteracy affecting health-seeking behaviours. The left-hand side of the figure displays the share of respondents who are at risk for psychological distress or low levels of positive mental health, including: (1) those at risk for depression, as defined by a scoring convention of the Short Form-12 mental health summary component (SF-12); those at risk for a probable common mental disorder, as measured by the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12); and (3) those who have poor mental well-being, as defined by a scoring convention of the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS). (Refer to Table 2.5 and Table 2.10, along with Annex 2.B, for more information on the three tools.) The right-hand side of the figure shows the share of respondents who report having ever received a diagnosis for a range of specific mental health conditions.

Figure 2.3. The share of those reporting a diagnosis of a mental health condition is much lower than the share identified as experiencing psychological distress by screening tools

Note: Scoring information for each of the screening tools included: risk for depression is defined as having a score <= 45 on the transformed SF-12 mental health component composite scale, where 0 indicates worst mental health and 100 best possible mental health; risk for a probable common mental disorder (CMD) is defined as having a score >= 4 on the GHQ-12, as used in (Woodhead et al., 2012[14]); poor mental health is defined as having a SWEMWBS score more than one standard deviation below the sample average. Refer to Annex 2.B for more information on individual screening tools.

Source: OECD calculations based on University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research (2022[15]), Understanding Society: Waves 1-11, 2009-2020 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009 (database), 15th Edition, UK Data Service, SN: 6614, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6614-16, from wave 10 only (Jan 2018 – May 2020).

Which population mental health data are OECD countries already collecting?

In February and March of 2022, 37 of 38 OECD countries provided answers to a questionnaire designed by the OECD Secretariat to better understand what OECD countries are doing in terms of measuring mental health outcomes.3 The questionnaire covers the statistical tools used (questions about diagnoses, experienced symptoms, screening tools and structured interviews) and outcomes covered (mental ill-health, positive mental health and other related topics, including loneliness, stress, attitudes towards mental health, etc.). A discussion of mental health data related to service use and access to care is set out in A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems (OECD, 2021[1]), and this new round of surveying seeks to build upon existing work by primarily focusing on mental health outcomes, rather than on service use or access to care, and in particular on outcomes that could be measured through household surveys rather than administrative data.

All OECD countries already collect both administrative and survey data on population mental health

All OECD countries collect mortality statistics on causes of death, including from suicides rates as well as deaths from alcohol and drug overdoses. Statistics on causes of deaths are typically collected by hospitals or health care providers, while police authorities report deaths from suicides. The OECD already regularly publishes statistics for its member countries on both deaths from suicide and other types of deaths of despair (OECD, 2020[16]; OECD, 2021[17]).4

Administrative data on mental health go beyond death records. Hospital discharge registries that, depending on the country, may cover the length of hospitalisation and discharges by field of medical specialisation were mentioned by a number of countries, including Canada, Chile, Hungary, Italy, Slovenia, Switzerland and Türkiye. Some countries, including Spain and the United Kingdom, collect care or clinical care data to measure prevalence and incidence of specific behavioural disorders. The Swedish Social Insurance Agency also collects data on causes of work absences, with a special category for sick leave following a psychiatric diagnosis. Finally, a handful of countries collect administrative data on psychiatric medication. For example, in France the Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament (ANSM) publishes data on psychotropic drugs delivered to outpatients; Statistics Netherlands provides data on dispensed medicines, including those related to mental health conditions as determined by ATC (anatomical therapeutic chemical) coding; Australia collects administrative data on dispensed medications covered under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme; and the Slovenian National Institute of Public Health (NIJZ) hosts data on prescription drug claims, including for mental health-related drugs.

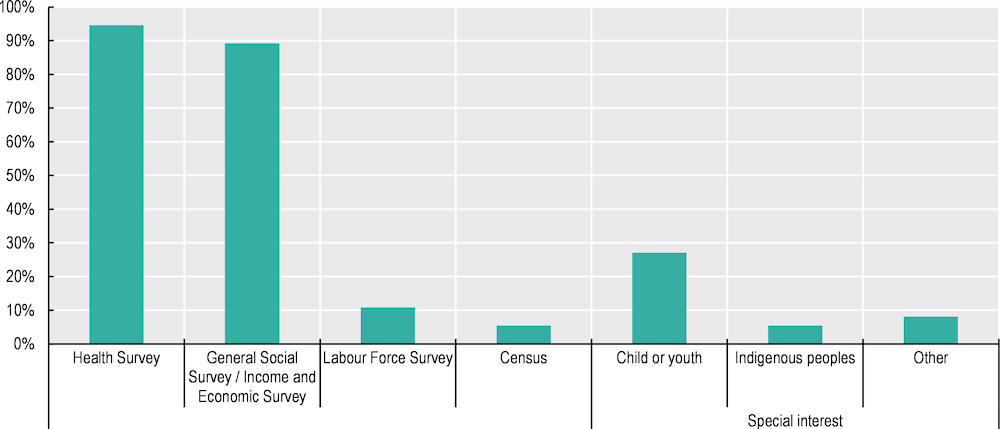

In addition, all OECD countries that responded to the questionnaire reported collecting population-wide data on mental health outcomes through household surveys, already prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. While much of these data are collected through health interviews, 89% of countries reported also collecting mental health data in general social surveys (Figure 2.4). Some data on mental health are also collected through labour force surveys and special modules of the national census. Some countries also reported collecting mental health data in special surveys that focus on sub-populations, including Indigenous peoples, those in the criminal justice system and young people (see Box 2.2 for more information on the latter).

Figure 2.4. The majority of OECD countries report measuring population mental health in both health and general social surveys

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

Many countries have launched surveys with mental health content since the onset of COVID-19, but it is unclear whether these will continue in the future

The pandemic has put mental health high on the national agenda for many OECD countries. As a result, most countries that answered the OECD questionnaire reported having ramped up data collection efforts on mental health in the months and years since March 2020. Around 68% of OECD countries reported collecting additional mental health data during the pandemic, either through new stand-alone surveys (43%) or by adding mental health and COVID-19 modules to existing surveys (35%) (see Table 2.3).5 Many of these new surveys are high-frequency, interviewing respondents weekly, biweekly, monthly or quarterly. However, it is unclear whether these surveys will continue in the future, or continue with the same frequency. Indeed, some COVID-specific surveys have already been discontinued by countries, while others that started off as weekly or monthly have since become less frequent (biweekly or quarterly).

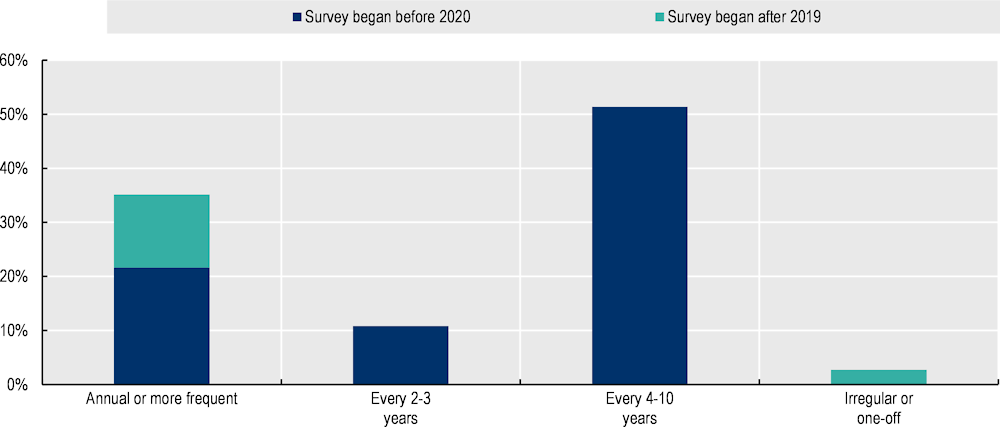

Before 2020, only 22% of countries collected mental health data on surveys that ran annually or more frequently, and 11% on surveys that ran every two to three years. Returning to business as usual prior to the pandemic would mean that over half (51%) of countries collect mental health data every four to ten years. Such large gaps between survey rounds make it more difficult to track changes at the population-level (which as has been seen during the COVID-19 pandemic were sensitive to periods of intensifying COVID‑19 deaths and strict confinement measures) and craft policy interventions accordingly.

Figure 2.5. Many OECD countries collect mental health data infrequently, with over half reporting four-to-ten-year lags between survey rounds

Note: This figure considers only the most frequently run survey per country, rather than the full set of surveys containing mental health data that countries report. It thus shows the highest degree of frequency for which mental health are available, per country. Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

Box 2.2. Initiatives to collect data on mental health for children and youth

The mental health of young people suffered dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2021[18]; OECD, 2021[19]), and a number of OECD countries launched campaigns focusing on youth mental health in 2021 and 2022 to help combat increasing rates of suicide, reported anxiety, depression and general psychological stress (HHS, 2021[20]; Chile, 2021[21]; Santé Publique France, 2021[22]). The results from the OECD questionnaire show that, although the pandemic may have underscored the importance of focusing on young people, many OECD countries were already implementing child or youth-specific surveys with mental health modules (Table 2.2).

The measurement of child and youth mental health differs from that of adults in several ways. Some surveys use the same tools for children and adults – questions about previous diagnoses, standardised composite scales such as the WHO-5, negative affect questions – however, there are also some youth-specific validated screening tools. A number of countries answering the OECD questionnaire reported using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a behavioural screening tool for children and youth aged three to 16, or the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWMA), to screen for psychiatric diagnoses for children starting at age of two. Child and youth surveys often include modules covering behavioural and emotional issues, adverse childhood experiences, positive childhood experiences and substance use/abuse, and can contain questions that are posed to children, parents or teachers (Table 2.11). Some surveys also cover previous diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Table 2.2. Many countries have introduced child and youth surveys, or survey modules, with a mental health focus

|

Country |

Survey |

|---|---|

|

Australia |

Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing |

|

Canada |

Canadian Health Survey of Children and Youth (CHSCY) |

|

Germany |

Study on the Health of Children and Adolescents in Germany (KiGGS) |

|

Italy |

Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents* |

|

Luxembourg |

Youth Survey Luxembourg |

|

United Kingdom |

Mental Health of Children and Young People Surveys |

|

United States |

Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)† |

|

Denmark, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Sweden |

Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) |

Note: The HBSC is a school-based survey, not a household survey. * indicates the survey was introduced following the start of the pandemic (post-March 2020). † The NHIS includes the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in the child component of the rotating core module. Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

Table 2.3. Over half of OECD countries reported increasing the collection of mental health data during the COVID-19 pandemic

|

Country |

Stand-alone COVID survey |

COVID module added to existing survey |

Any COVID-related survey |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

● |

● |

|

|

Austria |

|||

|

Belgium |

● |

● |

|

|

Canada |

● |

● |

|

|

Chile |

● |

● |

|

|

Colombia |

● |

● |

|

|

Costa Rica |

● |

● |

|

|

Czech Republic |

|||

|

Denmark |

|||

|

Finland |

● |

● |

|

|

France |

● |

● |

● |

|

Germany |

● |

● |

● |

|

Greece |

|||

|

Hungary |

|||

|

Iceland |

● |

● |

|

|

Ireland |

● |

● |

|

|

Israel |

● |

● |

|

|

Italy |

● |

● |

|

|

Japan |

|||

|

Korea |

● |

● |

|

|

Latvia |

|||

|

Lithuania |

|||

|

Luxembourg |

● |

● |

|

|

Mexico |

● |

● |

|

|

Netherlands |

● |

● |

|

|

New Zealand |

● |

● |

|

|

Norway |

● |

● |

|

|

Poland |

|||

|

Portugal |

|||

|

Slovak Republic |

|||

|

Slovenia |

● |

● |

|

|

Spain |

● |

● |

|

|

Sweden |

● |

● |

● |

|

Switzerland |

● |

● |

|

|

Türkiye |

|||

|

United Kingdom |

● |

● |

|

|

United States |

● |

● |

● |

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

The focus of household surveys is mainly on mental ill-health

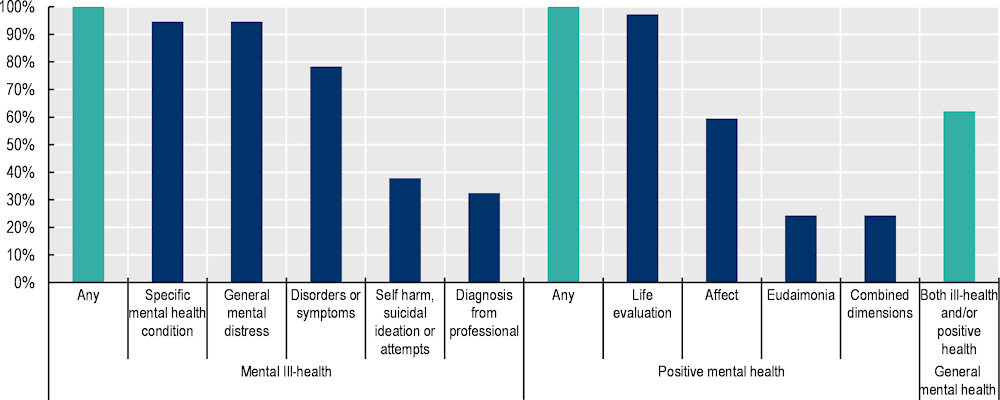

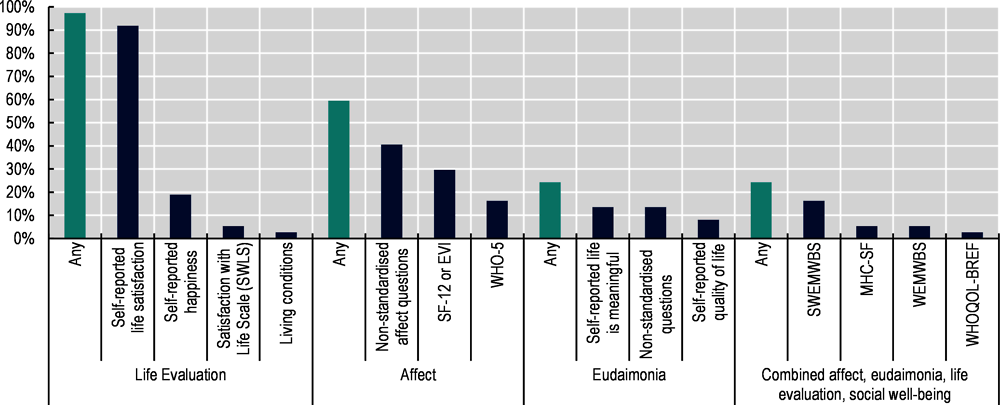

All OECD countries collect data on both mental ill-health and positive mental health outcomes. For the former, there is much variety in terms of both the tools used and outcomes measured, whereas for the latter cross-country comparative data are mainly limited to measures of life evaluation (Figure 2.6); 59% of countries reported collecting data on affect, and only 24% on eudaimonia.

Figure 2.6. All OECD countries reported collecting data on mental ill-health and positive mental health, with the latter mostly focused on life evaluation

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire. Note that the question collected during the EU-SILC 2013 ad hoc well-being module, on the extent to which respondents feel that their life is worthwhile, was not included in this figure given that the question was removed from subsequent well-being modules.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

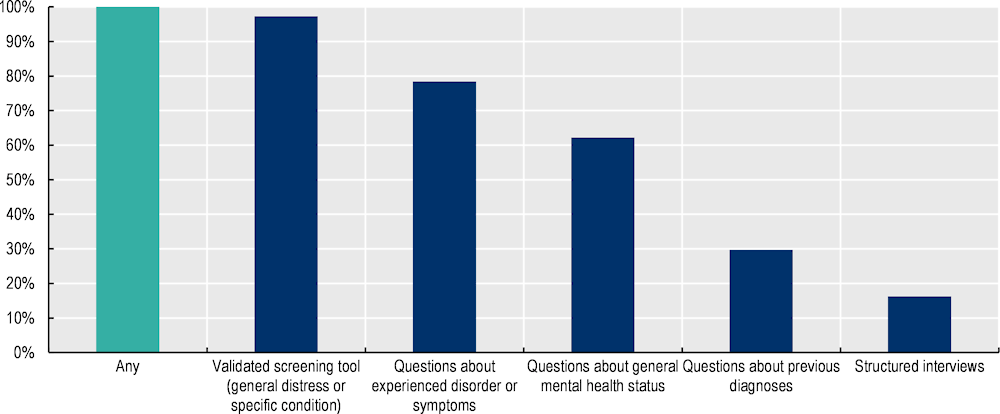

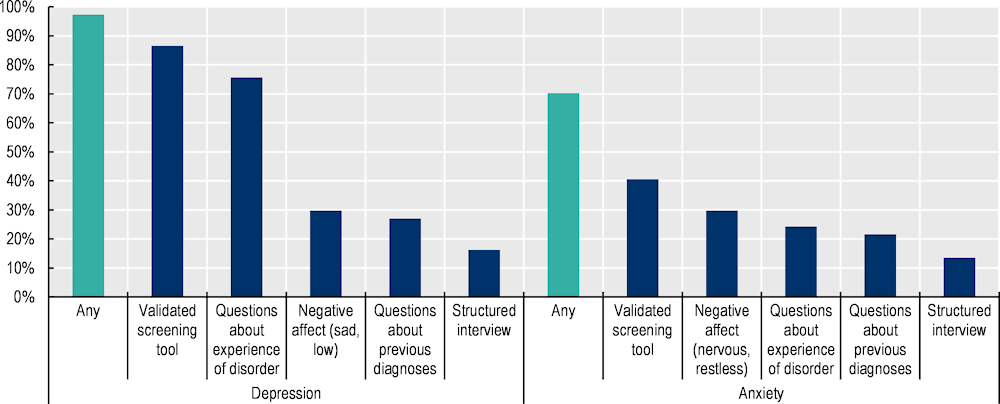

Mental ill-health outcome measures are captured through a variety of tools. The two tools most often reported by countries are screening tools and questions about experienced symptoms or disorders (either general or specific), with 97% and 78% of countries reporting using these types of tools in household surveys, respectively (Figure 2.7). Over half of countries (62%) ask single questions about people’s general mental health status. Many fewer countries report collecting data on previous diagnoses in household surveys (30%) or in structured interviews (16%).

Figure 2.7. Screening tools and questions about experience of symptoms and disorders are the most common mental ill-health tools reported by countries

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

General psychological distress and symptoms of depression tend to be captured by standardised screening tools, whereas measures of experiencing anxiety are often not harmonised across countries

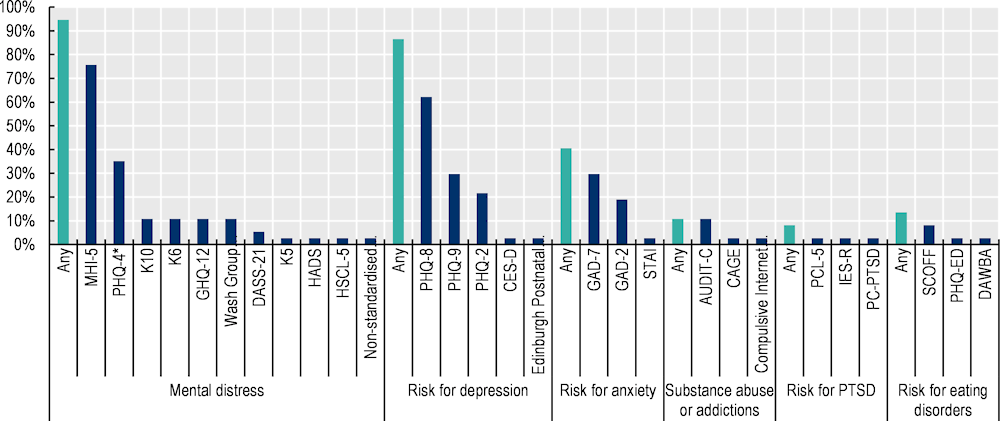

Within the continuum of mental ill-health, existing measurement initiatives focus more on some forms of mental health issues than on others. Anxiety and depressive disorder are the most common mental health conditions affecting people in OECD countries (OECD/European Union, 2018[23]).While 86% of countries (32 out of 37) have a dedicated validated screening tool for measuring symptoms of depression, and 95% have one for general psychological distress (35 out of 37), only 41% rely on a screening tool for symptoms of anxiety (15 out of 37) (Figure 2.8). Screening tools used by countries vary widely in terms of item length, ranging from two to 40 questions (see Table 2.5).

Variants of the PHQ are the most common screening tool for measuring symptoms of depression, used by 84% (31 out of 37) of countries. The MHI-5 is the most common screening tool for general psychological distress, used by 76% of countries (28 out of 37). In both instances, this is largely driven by Eurostat, which harmonises the data collection efforts of European Union member countries: 26 of the 28 countries that rely on the MHI-5 participate in Eurostat, all but Australia and Israel.6 The PHQ-8 has been included in Eurostat’s European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), which is conducted every five to six years. Variants of the PHQ are also used by a number of non-European OECD countries (see Table 2.5).

Figure 2.8. Screening tools capturing general psychological distress and symptoms of depression are more commonly used than those for symptoms of anxiety or other disorders

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire. Note that the MHI-5 and PHQ-8 findings are partly driven by Eurostat, although a number of other non-European OECD countries also use these, especially the PHQ-8. The MHI-5 will not be repeated in future EU-SILC ad hoc well-being modules, which will reduce the share of countries regularly collecting it.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

OECD countries also collected data on symptoms of anxiety, although often through country-specific tools rather than validated screening tools (Figure 2.9). 70% of countries report capturing anxiety outcomes, through some combination of structured interviews, questions about previous diagnoses or about experience of anxiety disorders, affect data or validated screening tools. Considering all measurement tools included in surveys, more countries indicated using them primarily for measuring symptoms of depression. The only exceptions are questions about negative affect, for which usage is evenly divided: 30% of countries reported using negative affect to measure both anxiety (feeling nervous, anxious) and depression (feeling low, downhearted).

The focus of measurement initiatives on depressive and anxiety disorders reflects the fact that they are some of the most prevalent mental health conditions (OECD/European Union, 2018[23]), and that they contribute highly to the disease burden globally and in OECD countries (Santomauro et al., 2021[24]). Data collection efforts for other specific mental conditions – such as PTSD, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, etc. – remain very uneven across OECD countries (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.9. Countries do capture anxiety data, but often with non-standardised measures

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

Most countries collect comparative data on life evaluation, but less so on affect and eudaimonia

Almost all OECD countries collect some data on life evaluation, primarily through a question on self-reported life satisfaction. Other aspects of positive mental health – affect and eudaimonia – are much less frequently covered by surveys undertaken by OECD countries; even when they are, the tools used are less standardised across countries (Figure 2.10). Measures of affect are more commonly collected than of eudaimonia; 59% of countries collect some form of affect data, through a combination of standardised composite scales and non-harmonised questions, while only 24% collect data on eudaimonia. In terms of standardised tools for measuring positive mental health outcomes, the SF-12 (and the SF-36 sub-component on energy and vitality, EVI), WHO-5 and either WEMWBS or its shorter form SWEMWBS are the three most common instruments; however, their overall use is still low: 30%, 16% and 19% of countries reported using each scale in a household survey, respectively.

Figure 2.10. Affect data are more commonly collected than eudaimonic data, but OECD countries are not aligned in the tools used to collect data on positive mental health beyond life satisfaction

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire. Note that the question collected during the EU-SILC 2013 ad hoc well-being module, on the extent to which respondents feel that their life is worthwhile, was not included in this figure given that the question was removed from subsequent well-being modules.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

There are interesting recent developments in topics such as data collection on mental health awareness

Overall, data collection efforts on additional mental-health related topics (e.g. use of mental health medication and services; mental health of children and young people in the household; loneliness and stress; resilience and self-efficacy; attitudes towards mental health, including stigma and literacy; and questions on unmet needs) are also uneven across countries (see Table 2.11). Many of these issues are not yet well-defined conceptually, with few internationally standardised tools available. For instance, only 30% of countries reported collecting (very different) indicators covering the topics of mental health stigma, discrimination, literacy and knowledge of mental health issues and resources.7 However, some countries have recently launched new survey efforts – and developed new methods – given increased interest in mental health awareness. For instance, in 2021 Sweden’s Public Health Agency conducted an online population survey, covering more than 10 000 respondents, on knowledge and attitudes about mental illness and suicide (Public Health Agency Sweden, 2022[25]). After systematically reviewing more than 400 existing instruments for measuring mental health stigma and conducting cognitive testing, the Public Health Agency concluded that the overwhelmingly negative tone of existing measures was in itself stigmatising and focused mostly on examples of severe mental illness. They hence decided to develop their own survey: the final questionnaire included items that were designed as semantic differentials (word pairs) that captured both positive and negative perceptions of mental illness and focused on all forms of mental illness, including more common experiences of depression, anxiety and stress-related conditions (Public Health Agency Sweden, 2022[25]).

Conclusion and ways forward

Measuring population mental health outcomes is not a new field for producers of official data in OECD countries, and many national statistical offices and health agencies were already collecting relevant data well before COVID-19. Nevertheless, it is also clear that there is room for improvement moving forward.

First, some aspects of mental health are measured more frequently than others, and there is scope for better cross-country harmonisation. The results of the OECD questionnaire to official data producers suggest that existing data collection efforts are not capturing the full range of mental health outcomes – missing aspects of both mental ill-health as well as positive mental health. While 86% of countries use a screening tool for symptoms of depression, and 95% for general psychological distress, only 41% use a standardised screening tool for symptoms of anxiety – and generalised anxiety disorder, along with mood disorders, is one of the most common mental health conditions affecting people in OECD countries. Data collection efforts for other specific mental conditions – such as post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, etc. – remain very uneven across countries. When it comes to positive mental health, almost all countries gather some form of life evaluation data, but information about affect and eudaimonia is much less frequently collected (by 59% and 24% of countries, respectively), and often not in a standardised manner. Data producers could hence as a first step expand their use of screening tools to those that include symptoms of anxiety, as well as depression, and move towards more harmonisation for affective and eudaimonic aspects of positive mental health.

Second, it will be important to measure mental health outcomes regularly, and to keep up some of the momentum provided by the high frequency surveys with mental health modules initiated during the first two years of the pandemic. Given the trade-offs between response burden and accuracy that data producers face when choosing between different tools to measure mental health outcomes, adding a single question about people’s general mental health status to frequently conducted population surveys could be a way to gather this information regularly and help link data across surveys. Over half of countries (62%) already include such single items in surveys, though question wording varies widely. Canada has been an early leader in developing single-item self-reported mental health (SRMH) indicators, and its question formulation has already been adopted by Chile and Germany, which could make it a useful model for other countries moving forward. While questions about previous diagnoses received by health care professionals are also short, evidence suggests that they focus mostly on people who have been in touch with the health system and hence are better placed in health surveys only.

Chapter 3 reviews the available evidence on the statistical quality of these recommended tools in further detail and provides suggestions for three concrete measures that countries could adapt to maximise international harmonisation and minimise response burden.

Lastly, whichever results are communicated to policy makers or the general public, it is essential to be transparent as to which exact aspect of mental health is being measured, including which areas a specific tool covers and does not cover (e.g. only previous diagnosis? only affect, or also somatic symptoms, and if so, which ones?). This information is important to contextualise findings and to provide transparency as to any limitations that might impact the interpretation of results.

Annex 2.A. Mental health survey measures by country

Table 2.4. Overview of structured interviews to monitor mental health conditions

|

Focus |

Tool |

Abbreviation |

Number of items |

Frame of reference |

Time to complete |

Already collected by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnosis of mental condition according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV |

Composite International Diagnostic Interview |

CIDI |

More than 300 symptom questions but because of skip rules not all of them are asked to every respondent |

75 mins |

Australia, Canada, Chile, Germany, Korea, United States (depressive symptoms only) |

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire. For more details on the tool, see Annex 2.B.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

Table 2.5. Overview of validated screening tools to monitor both general mental ill-health and risk for specific mental health conditions

|

Focus |

Covers |

Tool |

Abbreviation |

Number of items |

Frame of reference |

Already collected by country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Psychological distress |

Negative and positive affect |

Mental Health Inventory -5 |

MHI-5 |

5 |

Past month |

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom |

|

Psychological distress |

Negative affect, functional impairment |

Kessler Scale 10 |

K10 |

10 |

Past 4 weeks |

Australia, Canada, Netherlands, New Zealand |

|

Psychological distress |

Negative affect |

Kessler Scale 6 |

K6 |

6 |

Past 4 weeks |

Australia, Japan, Sweden, United States |

|

Psychological distress |

Negative and positive affect, somatic symptoms, functional impairment |

General Health Questionnaire |

GHQ-12 |

12 |

Recently |

Australia, Belgium, Finland, Spain, United Kingdom |

|

Symptoms of depression and anxiety |

Negative affect, anhedonia, functional impairment |

Patient Health Questionnaire -4 |

PHQ-4 |

4 (2 depression, 2 anxiety) |

Past 2 weeks |

Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Korea, Slovenia, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States |

|

Symptoms of depression and anxiety |

Negative and positive affect, anhedonia |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

HADS |

14 (7 depression, 7 anxiety) |

Past week |

France |

|

Symptoms of depression and anxiety |

Negative affect |

Hopkins Symptom Checklist |

HSCL-5 |

5 |

Past week |

Norway |

|

Symptoms of depression and anxiety |

Negative affect, anhedonia, somatic symptoms, functional impairment |

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale |

DASS-21 |

21 (7 depression, 7 anxiety, 7 chronic non-specific stress) |

Past week |

Australia, Italy |

|

Symptoms of depression and anxiety among the general and disabled population |

Negative affect, functional impairment |

Washington Group on Disability Statistics Short Set on Functioning – Enhanced |

WG-SS Enhanced |

12 (2 depression, 2 anxiety) |

General |

Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United States |

|

Symptoms of depression and anxiety among the general and disabled population |

Negative affect, functional impairment |

Washington Group Extended Set on Functioning |

WG-ES |

37 (3 depression, 3 anxiety) |

General |

United States |

|

Depressive symptoms |

Negative affect, anhedonia, somatic symptoms, functional impairment (matched to major depressive disorder per DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria) |

Patient Health Questionnaire -8 |

PHQ-8 |

8 |

Past 2 weeks |

Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Türkiye, United Kingdom, United States |

|

Depressive symptoms |

Negative affect, anhedonia, somatic symptoms, functional impairment (matched to major depressive disorder per DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria) |

Patient Health Questionnaire -9 |

PHQ-9 |

9 (PHQ-8 + question on suicidal ideation) |

Past 2 weeks |

Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Korea, Slovenia, Switzerland, United States |

|

Depressive symptoms |

Negative affect, anhedonia |

Patient Health Questionnaire -2 |

PHQ-2 |

2 |

Past 2 weeks |

Australia, Canada, Chile, Finland, Germany, Italy, Norway, United States |

|

Depressive symptoms |

Negative and positive affect, anhedonia, somatic symptoms, functional impairment, interpersonal challenges |

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale |

CES-D |

20 |

Past week |

Mexico |

|

Symptoms depression among recent mothers |

Negative and positive affect, anhedonia, functional impairment |

Edinburg Post-natal Depression Scale |

EPDS |

6 |

Past week |

Italy |

|

Symptoms of anxiety |

Negative affect, somatic symptoms, functional impairment |

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 |

GAD-7 |

7 |

Past 2 weeks |

Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Korea, Slovenia, Switzerland, United States |

|

Symptoms of anxiety |

Negative affect, functional impairment |

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-2 |

GAD-2 |

2 |

Past 2 weeks |

Australia, Canada, Chile, Germany, Mexico, United Kingdom, United States |

|

Symptoms of anxiety |

Negative affect,(including panic-like anxiety), functional impairment, subjective well-being |

The State and Trait Anxiety Scale |

STAI |

40 (20 state anxiety, 20 trait anxiety) |

State anxiety: “in this moment”, trait anxiety: “generally” |

Italy |

|

Symptoms of panic disorder |

Presence and severity of anxiety attacks, somatic symptoms |

Patient Health Questionnaire-Panic Disorder |

PHQ-PD |

15 |

Past 4 weeks |

Germany, Switzerland |

|

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) |

Presence and severity of PTSD symptoms (matched to DSM-5 criteria) |

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 |

PCL-5 |

20 |

Past 4 weeks |

Canada |

|

Symptoms of PTSD |

Presence and severity of PTSD symptoms (matched to DSM-5 criteria) |

Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 |

PC-PTSD-5 |

5 |

Past 4 weeks |

Switzerland |

|

Symptoms of PTSD |

Presence and severity of PTSD symptoms (matched to DSM-IV criteria) |

Impact of Event Scale – revised |

IES-R |

22 |

Past week |

Italy |

|

Symptoms of agoraphobia |

Presence and severity of anxiety related to different aspects of everyday life |

Angstbarometer |

Angstbarometer |

12 |

Past year |

Switzerland |

|

Symptoms of social anxiety disorder |

Presence and severity of symptoms of social anxiety disorder |

Mini-Social Phobia Inventory |

Mini-SPIN |

3 |

Past week |

Finland, Switzerland |

|

Symptoms of substance abuse or addiction |

Presence and severity of symptoms of alcoholism |

CAGE Substance Abuse Screening Tool |

CAGE |

4 |

No specific recall period |

Belgium |

|

Symptoms of substance abuse or addiction |

Presence and severity of symptoms of alcoholism |

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise |

AUDIT-C |

3 |

No specific recall period |

Chile, Sweden |

|

Symptoms of substance abuse or addiction |

Presence and severity of symptoms of alcoholism |

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

AUDIT |

10 |

No specific recall period |

France, Spain |

|

Symptoms of substance abuse or addiction |

Presence and severity of Internet addiction and compulsive, pathological, or problematic online behaviours (matched to DSM-IV criteria for substance addiction and pathological gambling) |

Compulsive Internet Use Scale |

CIUS |

14 |

No specific recall period |

Switzerland |

|

Symptoms of eating disorders |

Presence and severity of symptoms of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa |

SCOFF |

SCOFF |

5 |

Past 3 months |

Belgium, Finland, Germany |

|

Symptoms of eating disorders |

Presence and severity of symptoms of binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa and recurrent binge eating |

Patient Health Questionnaire-Eating Disorder Module |

PHQ-ED |

6 |

Past 3 months |

France |

|

Symptoms of eating disorders in 7-17 year-olds |

Presence and severity of symptoms of eating disorders |

Screening questions from the Development and Wellbeing Assessment – Eating Disorder Module |

DAWBA |

5 |

No specific recall period |

United Kingdom |

Note: Countries in italics are those that have explicitly stated that they no longer collect the measure in question. Countries in bold did not report collecting the instrument in their official questionnaire submission, however, it was added by the OECD Secretariat based on the country’s participation in the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), which contains the PHQ-8 as a core module. The PHQ-4 country practice was added in by the Secretariate for countries collecting both the PHQ and GAD (from which the PHQ-4 pulls its indicators), regardless of individual country reporting on the PHQ-4 itself. Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire. Data for the United Kingdom include only surveys carried out by the Office for National Statistics on mental health and do not include the data collected by devolved administrations. For details of the tools collected by at least two OECD countries, see Annex 2.B.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

Table 2.6. Overview of questions about previous diagnoses

|

Category |

Example question framing |

Answer options |

Frame of reference |

Already collected by country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Received diagnosis of any mental health condition |

Have you been told by a doctor or nurse that you have any of these long-term health conditions? List: Mental health condition (including depression or anxiety) (AUS) Have your mental health problems ever been diagnosed as a mental disorder by a professional (psychiatrist, doctor, clinical psychologist)? (SVN) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Australia, Slovenia |

|

Received diagnosis of any mood disorder (including depression) |

Have you ever in your life been diagnosed by a doctor with any of the following health problems or illnesses? In the event that you have been diagnosed any of them, have you received or are you undergoing medical treatment? Depression or anxiety (CHL) During your life, has a doctor ever told you that you had a psychiatric or psychological disorder or an addiction? Depression or depressive episode (FRA) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, last 12 months, or during COVID |

Australia, Austria, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, France, New Zealand, Slovenia, Spain, United States |

|

Received diagnosis of anxiety disorder |

Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse or other health professional that you have any of these conditions? Anxiety (AUS) Has a health professional ever told you that you have…? Chronic anxiety (CRI) During your life, has a doctor ever told you that you had a psychiatric or psychological disorder or an addiction? Anxiety disorder (generalised anxiety, phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, etc.) (FRA) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, during COVID |

Australia, Chile, Costa Rica, France, New Zealand, Slovenia, Spain, United States |

|

Received diagnosis of bipolar disorder or mania |

Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have bipolar disorder, which is sometimes called manic depression? (NZL) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, during COVID |

Australia, France, New Zealand, Slovenia |

|

Received diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) |

Have you ever been diagnosed with PTSD? (CAN) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Australia, Canada |

|

Received diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) |

Have your mental health problems ever been diagnosed as a mental disorder by a professional (psychiatrist, doctor, clinical psychologist)? Obsessive compulsive disorder (SVN) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Australia, Slovenia |

|

Received diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders |

During your life, has a doctor ever told you that you had a psychiatric or psychological disorder or an addiction? Schizophrenia (FRA) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, during COVID |

France, Slovenia |

|

Received diagnosis of personality disorder |

During your life, has a doctor ever told you that you had a psychiatric or psychological disorder or an addiction? borderline personality disorder (FRA) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, during COVID |

France |

|

Received diagnosis of agoraphobia or social disorder |

Were you told by a doctor, nurse or other health professional that you had [...] mental health condition? Agoraphobia (AUS) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Australia |

|

Received diagnosis of addictive disorder or substance abuse problems |

Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse or other health professional that you have any of these conditions? Harmful use or dependence on alcohol or drugs (AUS) During your life, has a doctor ever told you that you had a psychiatric or psychological disorder or an addiction? Addiction or addictive disorder (FRA) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, during COVID |

Australia, France |

|

Received diagnosis of an eating disorder |

Have your mental health problems ever been diagnosed as a mental disorder by a professional (psychiatrist, doctor, clinical psychologist)? Eating disorder (SVN) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, during COVID |

France, Slovenia |

|

Received diagnosis of conduct disorder or behavioural / emotional problems |

Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse or other health professional that you have any of these conditions? Behavioural or emotional problems (AUS) Have you ever been diagnosed with conduct disorders by a medical professional? (ESP) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Australia, Spain |

|

Neurodiversity: received diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

Have [you/name] ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that {you/he/she} had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention deficit disorder (ADD)? (USA) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Germany, United States |

|

Neurodiversity: received diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) |

Have you ever been diagnosed with autism by a medical professional? (ESP) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Spain |

|

Received diagnosis of any other mental health condition |

Do you have any other long-term physical or mental health condition that has been diagnosed by a health professional? (CAN) Have your mental health problems ever been diagnosed as a mental disorder by a professional (psychiatrist, doctor, clinical psychologist)? (SVN) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, last 12 months, or during COVID |

Australia, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, France, Slovenia |

Note: Results are shown for all OECD countries except Estonia, which did not participate in the questionnaire. Data for the United Kingdom include only surveys carried out by the Office for National Statistics on mental health and do not include the data collected by devolved administrations.

Source: Responses to an OECD questionnaire sent to national statistical offices in January 2022.

Table 2.7. Overview of questions about experienced symptoms and mental health conditions

|

Category |

Example question framing |

Answer options |

Frame of reference |

Already collected by country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Self-reported mental health problems |

Have you suffered from psychological stress or an acute illness in the last three months? (ISR) Are you currently facing mental health problems? (SVN) Do you have your own experience with mental illness? (SWE) Do you think you ever had a problem with your own mental health? (USA) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, last 12 months, last 3 months |

Hungary, Israel, Slovenia, Sweden, United States |

|

Self-reported mood disorder (depression, etc.) or mood disorder symptoms |

During the past 12 months, have you had any of the following diseases or conditions? Depression (European OECD countries participating in EHIS) Do you have a mood disorder? (CAN) Next I will ask you some questions related to different chronic diseases or health conditions that you may currently have. Chronic diseases are those of long duration and usually evolve slowly. Do you have chronic depression? (CRI) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, last 12 months, current |

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Türkiye, United Kingdom, United States |

|

Self-reported anxiety disorder, or anxiety symptoms |

Do you have an anxiety disorder? (CAN) During the last 12 months did you have or do you have any of the chronic diseases / diseases that are listed: Anxiety disorders (e.g. panic attacks, anxiety) (GRC) Have you ever suffered from chronic anxiety? (ESP) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime, last 12 months, last 3 months, current |

Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Greece, Hungary, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden |

|

Self-reported bipolar disorder or mania |

Do you have any of these conditions? Bipolar disorder (AUS) Do you have a mood disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia? (CAN) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Australia, Canada |

|

Self-reported PTSD |

Do you currently experience symptoms of PTSD? (CAN) |

Yes / No |

Lifetime |

Australia, Canada |

|