This chapter describes corporate governance policies and practices in ASEAN jurisdictions to mobilise their capital markets, in alignment with the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. The first section discusses ownership structures in the region, and also describes regional initiatives to develop an integrated regional capital market, including the ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard. The second section discusses corporate governance policies and practices in ASEAN economies and their relevance for promoting corporate access to capital market financing, including with respect to company groups, institutional investors and stewardship, corporate sustainability, general shareholder meetings, and the responsibilities of the board. The final section discusses policy considerations.

Mobilising ASEAN Capital Markets for Sustainable Growth

2. Corporate governance in ASEAN economies

Abstract

2.1. Introduction

The corporate governance framework in the ASEAN economies should be facilitated in a way that takes into consideration the reality of its corporate ownership structures and other recent evolutions impacting capital markets, such as climate change and digitalisation. This section provides an overview of ownership structures and describes regional initiatives to develop an integrated regional capital market, including the ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard.

2.1.1. Ownership structure of ASEAN listed companies

By the end of 2023, the ownership structure of listed companies worldwide has two main characteristics: a wide variety of ownership structures across countries, and the prevalence of concentrated ownership in listed companies.

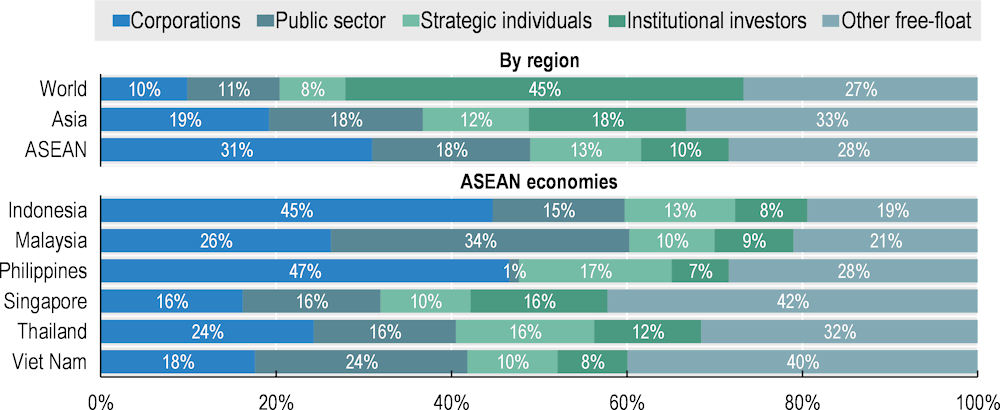

In terms of the relative importance of each category of investors, there are significant differences across regions and jurisdictions. Institutional investors constitute the largest category of investors globally, making up 45% of total equity holdings (Figure 2.1). However, this percentage is notably lower in Asia at 18% and even lower in ASEAN economies at 10%. Conversely, corporations are the predominant owners of public equity in ASEAN economies reflecting the prominent existence of company group structures. Particularly, their holdings account for 31% of the total, while globally, corporations only own 10% of public equity. Moreover, shareholders that are not required to disclose their ownership, contribute significantly to equity holdings, representing a total share of 27% globally, 33% in Asia, and 28% in ASEAN economies. The ownership share of the public sector, as well as that of strategic individuals, is also slightly higher in Asia and ASEAN economies compared to the global level.

Figure 2.1. Investors’ holdings, end of 2023

Note: Investors are classified following De La Cruz, Medina and Tang (2019[1]) “Owners of the world’s listed companies”.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

Within ASEAN countries, corporate participation in listed equity is particularly high in Indonesia and Philippines, where they holdings account for 45% and 47% of the total listed equity, respectively. In the other markets, the ownership share of corporations ranges from 16% to 26%. Disparities are also evident across other investor categories. For instance, the public sector plays a crucial role in Malaysia and Viet Nam, owning 34% and 24% of total equity, respectively, while its share is slightly above 1% in the Philippines. Furthermore, in Singapore, institutional investors own 16% of listed equity, a proportion that is comparatively higher than in any other jurisdictions and the ASEAN average.

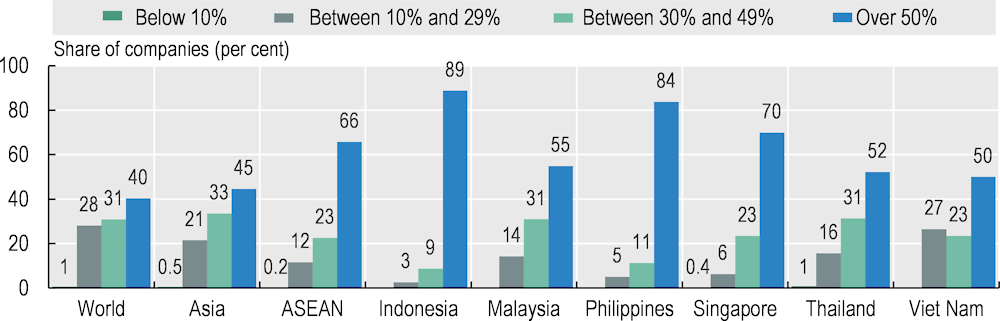

ASEAN as a region has higher ownership concentration at the company level compared to both global and Asian levels. Figure 2.2 shows the share of companies with different levels of combined ownership for the three largest shareholders. Notably, in 66% of the ASEAN listed companies, the three largest shareholders together hold more than 50% of the listed equity. Additionally, in 12% and 23% of the ASEAN listed companies the three largest shareholders own between 10% and 29%, and between 30% and 49% of the public equity, respectively. However, differences exist across countries. For instance, Indonesia, Philippines and Singapore exhibit the highest levels of ownership concentration as in over 70% of listed firms the three largest shareholders hold more than 50% of the listed equity. In Malaysia, Viet Nam and Thailand, although this share decreases to around 50% of total firms, is still higher than the global average (40%).

Figure 2.2. Ownership concentration by the largest three shareholders, end of 2023

Note: Figure shows the share of companies with different levels of combined ownership for the three largest shareholders.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

In ASEAN economies, corporations are the primary owners of listed firms (Table 2.1). In most cases, listed companies are part of a group either as the parent company or as a subsidiary. When the listed company is a subsidiary of the group, it is usually directly owned by the parent or at most by a company two layers away from the parent. This situation can originate agency-related issues, including the potential extraction of private benefits of control at the expense of other shareholders, opaque related party transactions among group members, and conflicts of interest between different group members with overlapping activities. (Medina, De la Cruz and Tang, 2022[2]).

As for the origin, with the exception of Singapore, domestic corporations hold a greater share of market capitalisation compared to non-domestic ones in all of the countries (Table 2.1). This is particularly notable in the Philippines, where domestic corporations own 43% of the nearly 47% share of the listed equity held by corporations. Furthermore, in the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, the predominant equity owners are other listed corporations, whose market capitalisation accounts for 31%, 10% and 17% of the total, respectively. In contrast, in the remaining countries, non-publicly listed corporations are the most relevant owners.

Over the past two decades, the public sector has emerged as a significant owner of listed equity primarily due to the listing of minority shares of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) due to partial privatisation processes. In addition, the public sector has also increased its presence in the stock market through the establishment of sovereign wealth funds and public pension funds, among others. This increasing ownership could have some implications on companies’ management. For instance, when the state is a controlling shareholder in a company, it has the potential to use its political influence in a manner that may not align with the interests of minority shareholders. Moreover, even if the state doesn't own a significant portion of the company's shares, it can still exercise significant operating control and influence both internal and external governance mechanisms (Medina, De la Cruz and Tang, 2022[2]).

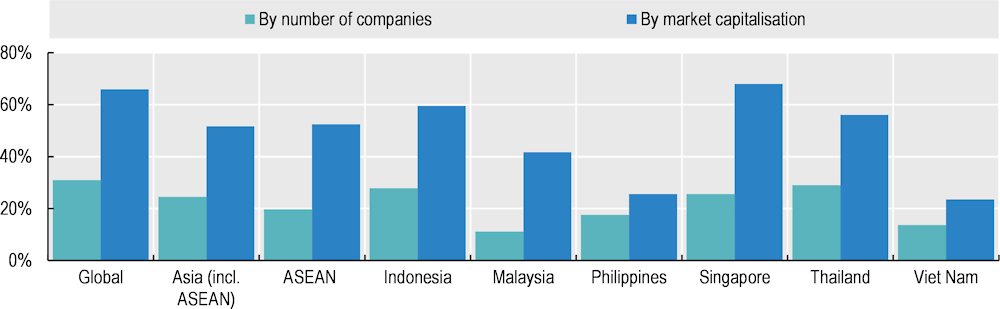

By the end of 2023, the public sector owned 12% of listed equity globally, and this figure was even higher in both Asian and ASEAN economies, standing at 25% and 29% respectively (Figure 2.1). Specifically, the public sector had controlling holdings in 2 039 listed companies worldwide (Table 2.2). Moreover, 76% of these companies were listed in Asia. There were 196 listed companies on ASEAN exchanges under state control, and their combined market capitalisation amounted to USD 706 billion, which represents almost one-third of the total market capitalisation in the region, a percentage more than twice the global value. State-controlled companies tend to be larger than other companies, especially in ASEAN economies where they account for 29% of total market capitalisation and only represent 8% of the total number of listed companies.

Table 2.1. Corporations as owners by location and listed status, end of 2023

|

Share of market capitalisation owned by: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Corporations |

Non-domestic corporations |

Domestic corporations |

Publicly listed corporations |

Non-domestic public listed corporations |

Domestic public listed corporations |

|

Indonesia |

44.6% |

12.2% |

32.4% |

21.9% |

8.3% |

13.6% |

|

Malaysia |

26.1% |

7.0% |

19.2% |

11.7% |

5.1% |

6.6% |

|

Philippines |

46.6% |

3.2% |

43.3% |

30.7% |

2.4% |

28.4% |

|

Singapore |

16.2% |

8.9% |

7.2% |

10.3% |

7.1% |

3.1% |

|

Thailand |

24.3% |

9.0% |

15.3% |

17.1% |

8.0% |

9.1% |

|

Viet Nam |

17.5% |

6.7% |

10.8% |

8.4% |

3.9% |

4.5% |

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

Table 2.2. Public sector holdings, end of 2023

|

|

Market cap. of state-controlled companies (USD million) |

No. of listed companies under state control |

Average state holdings1 |

State-controlled listed companies (share of total market capitalisation) |

State-controlled listed companies (share of total number of companies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

By region |

|||||

|

World |

12 829 204 |

2 039 |

54% |

12% |

7% |

|

Asia |

7 657 701 |

1 558 |

54% |

25% |

9% |

|

ASEAN |

706 282 |

196 |

58% |

29% |

8% |

|

ASEAN economies |

|||||

|

Indonesia |

167 333 |

49 |

67% |

22% |

9% |

|

Malaysia |

185 905 |

57 |

55% |

51% |

10% |

|

Philippines |

188 |

1 |

38% |

0.1% |

1% |

|

Singapore |

162 294 |

15 |

43% |

39% |

6% |

|

Thailand |

113 846 |

20 |

53% |

23% |

4% |

|

Viet Nam |

76 714 |

54 |

59% |

41% |

20% |

Notes: State control is defined as any state holding of at least 25% of the listed equity. Control is not restricted to the state where the company is listed: a company listed in Viet Nam can be controlled by a state different from the Vietnamese state. The definition of state used here may differ from that is used in individual jurisdictions, see the Annex for details.

1. The state holdings correspond to the average within the companies identified as being under state control.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

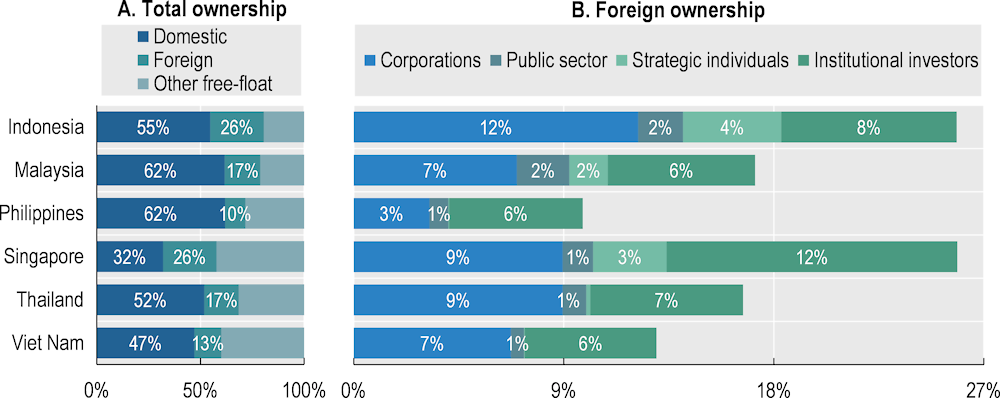

In ASEAN economies, the ownership of listed companies is dominated by domestic investors, with Singapore and Viet Nam to a lesser degree. In Philippines and Malaysia, 62% of the total equity is held by domestic investors, the highest share among the markets considered. In contrast, Singapore has the lowest domestic ownership rate, accounting for 32% of the total equity. For Indonesia this figure raises to 55%, while Thailand shows domestic ownership of 52% (Figure 2.3, Panel A).

Figure 2.3. Ownership of public equity by origin and category of investors, end of 2023

Note: The category other-free float in Panel A represents shares in the hands of investors that are not required to disclose their holdings and therefore no information is available.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

Among foreign investors, corporations and institutional investors are the two predominant categories. Indonesia stands out as the jurisdiction with the highest foreign corporate participation, constituting 12% of the total listed equity. In the Philippines, corporations represent the lowest share. The foreign public sector holds between 1-2% of the listed equity while foreign strategic individuals hold less than 4% of the listed equity across ASEAN markets. Foreign institutional investors hold 6-7% of the listed equity in Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam. The participation of foreign institutional investors is higher in Indonesia and Singapore.

2.1.2. Regional initiatives

The ASEAN financial markets are heavily dependent on bank financing and policy makers should consider designing policies to encourage the development and use of market-based financing. To mobilise the capital markets as a region, the ASEAN Capital Markets Forum, a high-level grouping of capital market regulators from all 10 ASEAN member states, has worked to achieve greater integration of the region’s capital markets, and one of its mandates is to raise corporate governance standards and practices of ASEAN listed companies.

One of these initiatives is the ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard (ACMF, 2024[3]). The Scorecard consists of a set of questions asked to listed companies to assess corporate governance practices in six participating countries, which are Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam. Based on companies’ responses, the ASEAN Corporate Governance Initiative publishes bi-annual country assessment reports that analyse the evolution of corporate governance practices in each jurisdiction as well as areas for further improvement. The Scorecard was developed with the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance (hereafter “the Principles”) as a main reference. The Scorecard was revised in October 2023 in response to the revision of the Principles.

2.2. Corporate governance policies and practices in ASEAN economies

This section discusses relevant corporate governance issues in ASEAN economies, including Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The discussion covers issues on company groups, the role of institutional investors and stewardship, corporate sustainability, general shareholder meetings, and the board of directors.

2.2.1. Company groups

Good corporate governance frameworks should reflect the reality of the ownership structure of listed companies in respective jurisdictions. As illustrated in Figure 2.1, corporations are the largest owners of ASEAN listed companies, reflecting the prominent existence of company group structures.

Group structures can have advantages, including scale economies, efficiencies in resource allocation, reduced dependence on external finance, fewer information asymmetries, lower transaction costs and less reliance on contract enforcement. Additional common rationales for group structures are to facilitate the protection of intellectual property rights and cross-border activity (OECD, 2020[4]). Meanwhile, they may also be associated with risks of inequitable treatment of shareholders. The Principles therefore state that it is important for regulatory frameworks to ensure the effective oversight of publicly traded companies within company groups (I.H).

Furthermore, family businesses are often observed in companies in the ASEAN region. When founders and their family members own a controlling equity stake in a company while they are also involved in important business decisions of the company and the group, it can reduce the agency problem through higher incentives to monitor the management closely. Still, corporate governance frameworks should ensure that minority shareholders and bondholders are protected from abusive actions. On the other hand, when founders and their family members hold smaller or even no shares of the company, they may influence the company’s decision-making disproportionate to their shareholding (OECD, 2022[5]) and the accountability becomes opaque. These relationships may not be captured by quantitative thresholds or definitions of substantial shareholders that may determine disclosure of related party transactions, and may require additional policy considerations.

Reflecting those practices and issues, it is important for the corporate governance framework to ensure the monitoring of group-wide risk management, related party transactions, and disclosure.

Group-wide risk management

Company groups need to manage group-wide risks while enabling timely and flexible decision-making of individual companies. Risks company groups face are becoming diverse, including on environmental impacts and human rights. For example, if a company’s subsidiary overseas fails to do proper due diligence for their suppliers or squeezes them, it could affect their brand name and cause compliance and reputational risks. The Principles emphasise the importance of group-wide risk management and oversight of controls (V.D.8). To properly assess the group-wide risk, it is essential that board members of the parent company obtain accurate, relevant and timely information for the group.

The Principles state that the regulatory framework should ensure board members’ access to key information about the activities of its subsidiaries to manage group-wide risks and implement group-wide objectives (V.F). ASEAN jurisdictions commonly have provisions that enable the board or management of a parent company to examine the books and records of their subsidiaries (OECD, 2022[5]). Board members’ access to information about activities of group companies beyond these issues is ensured in several jurisdictions e.g. Thailand1 and Viet Nam.2

Related party transactions

Company groups are often involved in related party transactions. This is natural, as facilitating cooperation and exploration of synergies is considered one of the benefits of company groups. There is a potential abuse of related party transactions, as complicated group structures may increase the opaqueness of transactions and the possibility of circumventing disclosure requirements. Regulatory frameworks address related party transactions through a combination of measures, such as mandatory disclosure, board approval, and shareholder approval (OECD, 2023[6]).

The Principles, as in the Chapter on Disclosure and transparency, highlight the importance of identification of all related parties in jurisdictions with complex group structures involving listed companies (IV.A.7). In addition to periodic disclosure of related party transactions in financial statements based on the International Accounting Standards (IAS 24) or local standard similar to IAS 24, many jurisdictions have requirements for additional disclosure. Globally, the jurisdictions which have adopted the “German model” for the treatment of company groups require companies to disclose the negative impact of any influence by the parent company (OECD, 2023[6]).

Some ASEAN jurisdictions mandate immediate disclosure for specific related party transactions. In Malaysia, under the Listing Requirements (LR), listed issuers must disclose particulars of the material contracts and loans involving the interests of the directors, chief executive or major shareholders in their annual report. Further, a listed issuer must file an immediate announcement of non-recurrent related party transactions as soon as possible after the terms of the transaction have been agreed, if any of the percentage ratios defined in paragraph 10.02 of the LR is 0.25% or more. This does not apply to transactions below RM 500 000 or recurrent related party transactions. In Singapore, an issuer must make an immediate announcement of any interested person transaction of a value equal to, or more than, 3% of the group’s latest audited net tangible assets. They are also required to disclose all transactions (regardless of transaction value) if the cumulative transaction with that interested person and its associates is above a 3% threshold. Interested person transactions exceeding the 5% materiality threshold must be subject to independent shareholders’ approval. However, this does not apply to any transaction below SGD 100 000, or to certain types of transactions (OECD, 2023[6]). The ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard also shows that it is good practice to conduct related party transactions in such a way to ensure that they are fair and at arms’ length (A.9.1), while in practice it is pointed out that further improvement in disclosing this item is needed (ADB, 2021[7]).

Board approval for certain transactions is widely used as a safeguard against abusive related party transactions, and independent board members often play a prominent role. Many jurisdictions, including Malaysia, require or recommend as good practice for interested board members to abstain from board decisions. Furthermore, even in that case, if regulatory frameworks do not set qualifications for independent directors in terms of company groups, the effectiveness of involving independent directors might be undermined. The Principles, while recognising a variety of approaches to defining independence, describe a range of criteria, including the absence of a relationship with not only the company, but also its group (V.E). For example, management and directors of the parent company are not qualified as an independent board member in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. In these jurisdictions, management and directors of the subsidiary are not considered independent either.

Disclosure concerning company groups

Considering the complexity of group structures and the opaqueness that could occur in terms of accountability, transparency of share ownership and corporate control allow shareholders, debtholders and potential investors to make better informed decisions. The Principles IV.A.3 and IV.A.4 state that disclosure should include material information on capital structures, group structures and their control arrangements, as well as major share ownership, including beneficial owners, and voting rights.

In most jurisdictions, listed companies are required to prepare financial statements on a consolidated basis under the International Financial Reporting Standards, and disclose in their annual reports their major shareholders and the company’s material shareholdings. However, specific disclosure items vary across jurisdictions. Globally, the majority of jurisdictions require disclosure of important company group structures and intra-group activities for listed companies, such as major share ownership, special voting rights, corporate group structures and shareholdings of directors, while such disclosure is less widespread in the case of beneficial ownership, and cross-shareholdings (OECD, 2023[6]). In the ASEAN region, all eight jurisdictions require or recommend disclosure of major share ownership and disclosure provisions on beneficial owners and shareholdings of directors are also common (Table 2.3).

It is also regarded as good practice to disclose shareholding of family members of directors and/or key executives (OECD, 2022[5]). Meanwhile, in practice, one assessment has found that disclosure of direct and indirect shareholdings of (deemed) shareholdings of senior management was not sufficient in several ASEAN jurisdictions (ADB, 2021[7]).

Table 2.3. Disclosure provisions on company groups

|

Major share ownership (threshold) |

Beneficial owners |

Corporate group structures |

Special voting rights |

Cross shareholdings |

Shareholdings of directors |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cambodia |

● (10%) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Indonesia |

● (5%) |

● |

● |

●1 |

-2 |

● |

|

Lao PDR |

◆ (5%) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

◆ |

|

Malaysia |

● (5%)3 |

■4 |

● |

● |

- |

● |

|

Philippines |

● (5%, 10% and 20 and 100 largest shareholders) |

● |

● |

● |

- |

● |

|

Singapore |

● (5%) |

●5 |

- |

● |

● |

● |

|

Thailand |

● (10 largest shareholders) |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Viet Nam |

● (5%) |

● |

● |

- |

- |

● |

Key: ●= mandatory disclosure to public; ◆ = voluntary disclosure to public; ■ = mandatory reporting to the regulator/authorities; “-”No explicit requirement/recommendation

Note:

1. In Indonesia, it is mandatory for the specific regulated issuers that are allowed to have multiple voting rights which have innovation and high growth rates that conduct public offerings in the form of shares. In addition, issuers regulated in this provision should meet certain criteria such as utilising the technology to innovate products that increase productivity and economic growth, having shareholders who have significant contributions in the utilisation of technology, having minimum total assets of at least 2 trillion rupiah (or about USD 132 million), and others as promulgated by article Art. 3 OJK Regulation No 22/POJK.04/2021.

2. In Indonesia, cross-shareholding is prohibited.

3. In Malaysia, the requirement to disclose is for substantial shareholders holding at least 5% of voting shares. The definition of a major shareholder differs from a substantial shareholder. A major shareholder refers to a person who has an interest or interests in one or more voting shares in a corporation and the number or aggregate number of those shares, is (a) 10% or more of the total number of voting shares in the corporation, or (b) 5% or more of the total number of voting shares in the corporation where such person is the largest shareholder of the corporation.

4. In Malaysia, under Section 56 of Companies Act 2016, any company may require its shareholders to indicate the persons for whom the shareholder holds the voting share by names and other particulars if the shareholder holds the voting shares as trustee.

5. In Singapore, the disclosure to the public is mandatory only to the extent of deemed interests held by directors, CEO and substantial shareholders.

Source: OECD Survey; OECD (2022[5]), Good Policies and Practices for Corporate Governance of Company Groups in Asia, https://www.oecd.org/corporate/good-policies-practices-for-corporate-governance-company-groups-in-asia.htm.

2.2.2. The role of institutional investors and stewardship

One of the measures to make ASEAN capital markets more vibrant and to develop market-based financing could be to attract more investment from institutional investors. While the presence of institutional investors is relatively small in ASEAN markets, they are the largest owners in stock markets globally, and the participation of institutional investors in ASEAN capital markets could lead to diverse ownership and increased volume of market-based financing.

Table 2.4. Roles and responsibilities of institutional investors and regulated intermediaries

|

Jurisdiction |

National framework (Public / private / mixed initiative) |

Target institutions |

Exercise of voting rights |

Management of conflicts of interest |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Disclosure of voting policy |

Disclosure of actual voting records |

Setting of policy |

Disclosure of policy |

|||

|

Indonesia |

Public: Code of Conduct for Investment Managers (OJK Regulation 17/POJK.04/2022) |

Fund Managers |

- |

- |

L |

(L: Disclosure of conflicts of interest) |

|

Public: The Application of Corporate Governance of Investment Manager (OJK Regulation 10/POJK.04/2018) |

Investment managers |

L1 |

L1 |

L |

L |

|

|

Public: Good Corporate Governance for Insurance Companies (OJK Regulation 73/POJK.05/2016) |

Insurance companies |

- |

- |

L |

L |

|

|

Public: Good Corporate Governance for Insurance Companies (OJK Regulation 73/POJK.05/2016) |

Pension funds |

- |

- |

L |

L |

|

|

Malaysia |

Private: Malaysian Code for Institutional Investors (MCII) |

Asset owners, asset managers and service providers (including proxy advisors) |

CE2 |

CE |

CE |

CE |

|

Singapore |

Private: Singapore Stewardship Principles |

Institutional investors, including asset owners and asset managers IMAS members: Investment funds and asset managers |

I |

I |

I |

C |

|

Thailand |

Public: Investment Governance Code for Institutional Investors (I Code) |

Institutional investors |

CE |

CE |

CE |

CE |

Key: L = requirement by the law or regulations; I = self-regulatory requirement by industry association without comply or explain disclosure requirement; C = recommendation by codes or principles without comply or explain disclosure requirement; CE = recommendation including comply or explain disclosure requirement overseen by either a regulator or by the industry association; “-” = absence of a specific requirement or recommendation.

Industry, association or institutional investor stewardship codes are included only if they have official status and their use is endorsed or promoted by the relevant regulator.

1. In Indonesia, in OJK Regulation No 10/POJK.04/2018 (Section 53) provides that Investment Managers are encouraged to disclose voting policy and actual voting records.

2. In Malaysia, the Malaysian Code for Institutional Investors (MCII) adopts the “apply and explain” approach where signatories are encouraged to explain how they have applied the principles of the MCII, and where there are departures, to highlight the same, along with the measures to address the departures, and the time frame required to apply the relevant principles.

Source: OECD (2023[6]), OECD Corporate Governance Factbook 2023, https://doi.org/10.1787/6d912314-en.

Recognising the importance of institutional investors’ willingness and ability to make informed use of their shareholder rights and to effectively exercise their ownership functions in companies, the Principles have a number of recommendations. They include recommendations for institutions to disclose their policies for corporate governance and voting with respect to their investments (III.A) and to disclose how they manage material conflicts of interest that may affect the exercise of key ownership rights regarding their investments (III.D). Principle II.D also states that shareholders, including institutional shareholders, should be allowed to consult with each other on issues concerning their basic shareholder rights as defined in the Principles, subject to exceptions to prevent abuse.

The Principles state that stewardship codes may offer a complementary mechanism to encourage institutional investors’ engagement (III.A). It is observed that Asian jurisdictions have widely adopted stewardship codes (Fukami, Blume and Magnusson, 2022[8]). Out of the eight jurisdictions, four (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand) have adopted stewardship codes as frameworks for engagement by institutional investors (Table 2.4).

2.2.3. Corporate sustainability

To mobilise ASEAN capital markets, it is essential to attract investors both domestic and global. Investors have increasingly expanded their focus on companies’ performance to include the financial risks and opportunities posed by broader environmental and social challenges, and companies’ resilience to manage those risks. As one of their three core objectives, the Principles state that a sound framework for corporate governance with respect to sustainability matters can help companies recognise and respond to the interests of shareholders and different stakeholders, as well as contribute to their own long term success.

Climate-related risks have particularly drawn investors’ attention, while there are many other risks that companies in ASEAN economies are facing. By the end of 2022, companies that account for 62% of the market capitalisation in Asia were considered to be facing financially material climate change-related risks, which was similar to the global trend with 64% of the global market capitalisation (OECD, 2023[9]). Other sustainability issues that ASEAN companies are exposed to include human capital, data security and customer privacy, water and wastewater management, and supply chain management (OECD, 2023[9]).

This section focuses on policies and practices of sustainability-related disclosure and board responsibilities for sustainability matters in the ASEAN region.

Sustainability-related disclosure

Disclosure of material sustainability-related information is key for investors’ well-informed decision making. The revised Principles clarify that disclosure should include material sustainability-related information (IV.A.2). They support adherence to internationally recognised standards that facilitate the comparability of sustainability-related disclosure across companies and markets (VI.A.2). The Principles also aim to ensure that verifiable metrics are disclosed if a company publicly sets a sustainability-related goal or target (VI.A.4), and recommend the phasing in of external assurance to provide an objective assessment of a company’s sustainability-related disclosure (VI.A.5).

Regulators in Asia and around the world have increasingly adopted mandatory or voluntary sustainability-related disclosure provisions. ASEAN economies have been a part of this trend. At the regional level, the ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard, as revised in 2023, added new questions in alignment with the revised Principles. It includes questions about whether the company identifies environmental, social, and governance (ESG) topics that are material to its strategy (B.1.1), and whether the company discloses quantitative sustainability targets (B.1.4). A question on whether the company adopts an internationally recognised reporting standard for sustainability was upgraded from an optional question to a core question (B.1.3). The revised Scorecard also added an optional question on whether a company discloses the fact that its sustainability reporting is externally assured ((B).B.1.2). More broadly, The ASEAN taxonomy for sustainable finance is also being developed and regulators are expected to use it as a reference when setting rules for market participants concerning sustainability reporting disclosures at the portfolio and product levels (ASEAN Taxonomy Board, 2024[10]).

Corporate sustainability disclosure requirements and recommendations

Among ASEAN jurisdictions, five (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam) have mandatory requirements for corporate sustainability disclosure while three (Cambodia, Lao PDR and Philippines) have recommendations. This is similar to the global landscape, in which a requirement in the law, regulations or listing rules was established in more than 70% of the jurisdictions in 2022, while sustainability-related disclosure was a recommendation provided by codes or principles in 24% of the jurisdictions (OECD, 2023[6]).

In Indonesia, the Financial Services Authority (OJK), as part of the efforts to create a financial system that applies sustainable principles, introduced a new regulation in 2017 that requires financial services providers, issuers and public companies to implement sustainable finance in their business activities (OJK, 2017[11]). Financial institutions, issuers, and public companies3 are required to prepare and disclose a sustainability report that contains information on the sustainability strategy, governance, and performance among others. The effective implementation dates of the new regulation differ by size and business classification of the entities (the earliest being 2019 for commercial banks and the latest by 2025 for pension funds), while the regulator calls for the earlier implementation by financial services institutions that are also issuers and public companies.4

In Malaysia, the LR require listed companies to disclose a sustainability statement in their annual reports. For listed companies on the Main Market, the sustainability statement must include information on the governance structure in place for the oversight of sustainability, the scope and basis for the sustainability statement, and how the company’s material sustainability matters are identified and managed. Companies listed on the Main Market are required to disclose some additional information (such as data and performance targets) for annual reports issued with the financial year ending on or after 31 December 2023 and other items (such as climate-related disclosure aligned with the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) recommendations) for annual reports issued with the financial year ending on or after 31 December 2025, while the ACE Market listed companies5 are allowed to take more time, i.e. for annual reports issued for the financial year ending on or after 31 December 2025 and 31 December 2026, respectively (Bursa Malaysia, 2022[12]).

In the Philippines, the Securities and Exchange Commission of Philippines (SECP) in 2016 updated the Code of Corporate Governance for Publicly Listed Companies (CG Code for PLCs), which follows a comply or explain disclosure requirement, and recommended that listed companies start disclosing their ESG performance. In 2019, the SECP also published the sustainability reporting guidelines that are built upon international standards, which include the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) sustainability reporting framework, the International Integrated Reporting Council framework, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) standards, and the TCFD’s recommendations. The guidelines also required the PLCs to start issuing their Sustainability Reports in 2020 (SECP, 2019[13])

In Singapore, the Singapore Exchange (SGX) introduced a mandatory sustainability-related disclosure regime in 2016. SGX extended the sustainability-related disclosure regime to include disclosure of climate-related risks among other ESG issues (SGX, 2021[14]). The primary components of the sustainability report include: material ESG factors; climate-related disclosure consistent with the TCFD’s recommendations; policies and targets to each material ESG factor identified; sustainability reporting framework; and board statement and associated governance structure for sustainability practices. The climate-related reporting rules mandated by the SGX require issuers to follow a phased approach in accordance with the industries identified by the TCFD as most affected by climate change and the transition to a lower-carbon economy. In 2022, all issuers were required to implement measures on a “comply or explain” basis. In 2023, it became mandatory for issuers in the (i) financial, (ii) agriculture, food, and forest products, and (iii) energy industries; in 2024, for issuers in the (i) materials and buildings, and (ii) transportation industries (SGX, 2021[14]).

In Thailand, in 2020, the Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand (SECT) announced the mandatory use of a new reporting standard, named One Report, which is a consolidated form of an annual registration statement and annual report, in order to enhance the ESG disclosure standards which went into effect in 2022 (SECT, 2021[15]). The new form includes requirements to disclose environmental and social policies and guidelines as well as some specific indicators, including Greenhouse Gases (GHG) emissions.

In Viet Nam, in 2020, the Ministry of Finance issued a guidance on public disclosure requiring listed companies to report their corporate objectives on environmental and social issues, as well as impacts on the environment and society, including GHG emissions (SSC, 2020[16]). This took effect in 2021.

Among the eight jurisdictions, some require or recommend sustainability-related disclosures to be consistent with internationally accepted core standards, while the standards vary. In Malaysia and Singapore, climate-related disclosures should be consistent with the TCFD’s recommendations. In Viet Nam, in 2016, the State Securities Commission (SSC) in collaboration with the IFC published a guide for listed companies to adopt and better implement the disclosure of environmental and social information, building on the GRI reporting framework (SSC, 2016[17]), which implies calling for information on the company’s impact on the environment. Globally, the usage of GRI standards, TCFD’s recommendations or SASB standards was common and used in sustainability-related disclosure in 2022 by companies representing 60%, 54%, and 37% of global market capitalisation respectively (OECD, 2024[18]).

Consideration for flexibility for smaller listed companies

With relatively fixed costs for sustainability-related disclosure regardless of companies’ size (OECD, 2024[18]), corporate governance frameworks in ASEAN jurisdictions could consider a flexible approach for smaller listed companies. The Principles state that sustainability-related disclosure frameworks need to be flexible and that policy makers may need to devise sustainability-related disclosure requirements that take into account the size of the company and its stage of development (VI.A).

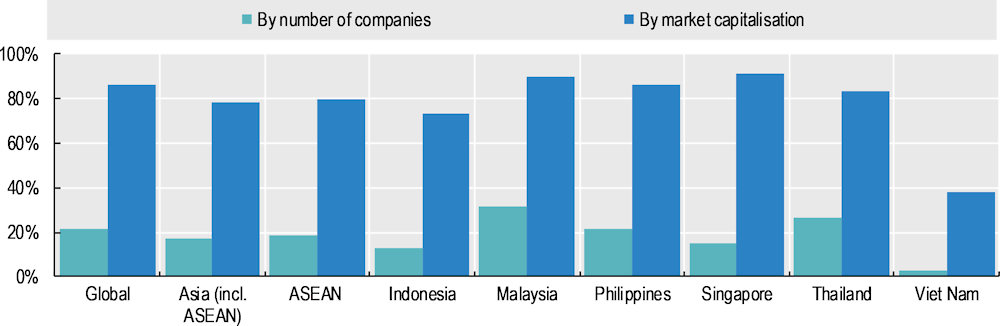

Figure 2.4 shows a gap in sustainability-related disclosure between larger and smaller listed companies. In the ASEAN region, companies representing 80% of the regional market capitalisation disclosed sustainability-related information in 2022 or later, and these companies account for 18% of all listed companies in the region. Each ASEAN country has a similar disparity between the market value and absolute number of companies disclosing sustainability-related information, which shows the challenges for small listed companies in disclosing sustainability information.

Figure 2.4. Disclosure of sustainability information by listed companies in 2022

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, LSEG, Bloomberg. For more information on the methodology, see the OECD (2024[18]), Global Corporate Sustainability Report, https://doi.org/10.1787/8416b635-en.

Several ASEAN jurisdictions have introduced some flexibility. For example, in Malaysia, the ACE Market listed companies (mainly smaller growth companies) are required to disclose a smaller number of disclosure items. In Indonesia, the effective implementation dates of the new regulation differ by the size of the companies.

Phasing in of assurance of sustainability information

Sustainability-related disclosures reviewed by an independent, competent and qualified assurance service provider may enhance investors’ confidence in the information disclosed and the possibility of comparing sustainability-related information between companies. ASEAN region regulators could consider encouraging external assurance by large listed companies in the longer term.

Practices and policies in the region show that the jurisdictions need time to adopt assurance. In ASEAN economies, companies accounting for 52% of market capitalisation disclosed sustainability-related information with assurance, while it represented 20% of the listed companies in 2022 (Figure 2.5). All ASEAN jurisdictions had a similar trend except for the Philippines, where there was a smaller gap between the two and companies representing 26% of the market capitalisation and 18% of the listed companies disclosed sustainability reports with assurance. The regulatory frameworks in the ASEAN jurisdictions have started including provisions on the external assurance, keeping them voluntary (in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore6).

Figure 2.5. Assurance of a sustainability report by an independent third party in 2022

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, LSEG, Bloomberg. For more information on the methodology, see the OECD (2024[18]), Global Corporate Sustainability Report, https://doi.org/10.1787/8416b635-en.

Board responsibilities

Boards are increasingly ensuring that material sustainability matters are also considered. As the revised Principles recommend, when fulfilling their key functions, boards should ensure that they also consider material sustainability matters (VI.C). The revised ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard also reflects it by adding a question on whether the company discloses board of directors/commissioner’s oversight of sustainability-related risks and opportunities ((B).B.1.5).

Reflecting the growing importance of these issues for companies, all of the eight jurisdictions have at least some provisions that clearly articulate the responsibilities of the board to ensure that governance practices, disclosure, strategy, risk management and internal control systems adequately consider material sustainability risks and opportunities.

In Indonesia, financial services institutions are required to prepare a sustainable finance action plan which should be arranged by the board of directors and approved by the Board of Commissioners.7 More generally, financial services providers, issuers, and public companies are required to implement sustainable finance in their business activities by using principles of responsible investment, sustainable business strategies and practice, and social and environmental risk management among others.8 It could be argued that the board is expected to take a lead role in drafting and implementing these principles.

In Malaysia, the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance sets out best practices and guidance to strengthen board oversight and the integration of sustainability considerations in the strategy and operations of companies (SCM, 2021[19]). Particularly, the Code recommends that the board together with management takes responsibility for the governance of sustainability in the company including setting the company’s sustainability strategies, priorities and targets.9 The board is also recommended to take appropriate actions to ensure that it stays abreast of and understands the sustainability issues relevant to the company and its business, including climate-related risks and opportunities.10

In several jurisdictions, the board responsibilities are approached from the point of view of disclosure requirements and recommendations. In Lao PDR, the board should ensure that the company discloses the material economic, environmental and social impacts in line with internationally accepted standards in the company’s annual report.11 In the Philippines, listed companies are recommended to disclose the board’s oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities; the risks and opportunities that the organisation has identified over the short, medium, and long-term; the processes for identifying and assessing the related risks; and the metrics used in assessing in line with the companies’ strategy and risk management processes (SECP, 2019[13]). In Singapore, the mandatory sustainability report should include “a statement of the Board that it has considered sustainability issues in the issuer’s business and strategy, determined the material ESG factors and overseen the management and monitoring of the material ESG factors.” Companies are also required to “describe the roles of the Board and the management in the governance of sustainability issues” (SGX, 2021[14]). In Viet Nam, companies are required to disclose the assessments by the board of directors of the company’s operations, including the assessment related to environmental and social responsibilities, while specifying the risks probably affecting the production and business operations or the realisation of the company's objectives, including environmental risks.12

In Thailand, the Corporate Governance Code refers to the board responsibilities for environmental and social issues mainly from the perspectives of innovation and responsible business. For example, Principle 5.1 of the Code states “[t]he board should prioritise and promote innovation that creates value for the company and its shareholders together with benefits for its customers, other stakeholders, society, and the environment, in support of sustainable growth of the company.” Here, the Code recommends the board to consider not only financial profits for shareholders, but also benefits for its stakeholders, the society and environment.

2.2.4. General shareholder meetings

General shareholder meetings are the main platform for shareholders to exercise their rights. Typically, a number of parties are involved in the voting process and share responsibilities, including proxy representatives, custodians, and service providers (Norges Bank, 2020[20]) and voting chains often involve foreign investors. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a major shift of company practices and legal frameworks to virtual meetings (where all shareholders attend the meeting virtually) as well as hybrid meetings (where some shareholders attend the meeting physically and others virtually). The revised Principles added a new recommendation that remote shareholder participation in virtual and hybrid shareholder meetings be conducted in a way that ensures equal access to information and engagement opportunities (II.C.3).

Reflecting such evolutions, the corporate governance framework needs to be facilitated so that shareholders can participate and exercise their voting rights with sufficient information in the meetings (Principle II.C). The details about the conduct of shareholder meetings are often delegated to each company’s bylaw, constitution or article of association. Still, it is important that the corporate governance framework (i) gives shareholders sufficient time and information to prepare meetings; (ii) provides proper identification of shareholders eligible for voting; (iii) ensures that shareholders’ voting is counted properly and accurately; (iv) encourages companies to properly handle questions from shareholders; and (v) encourages the disclosure of voting and meeting results.

Giving shareholders sufficient time and information to prepare meetings

Sub-principle II.C.1 of the Principles states “[s]hareholders should be furnished with sufficient and timely information concerning the date, format, location and agenda of general meetings, as well as fully detailed and timely information regarding the issues to be decided at the meeting.”

Shareholder meetings should be noticed well in advance to allow shareholders to have sufficient time to prepare for their participation and voting through the voting chain. When there is a long chain of voting process, parties need time to communicate among them, such as a voting instruction from shareholders to the proxy representative and registration as a proxy representative to a company. The shorter the notice period, the less time is left for each party to take for the examination and processes. The Principles highlight the importance of a reasonable notice period in the context of cross border voting (II.C.7).

All the eight ASEAN jurisdictions set the minimum notice period for holding general shareholder meetings but with significant differences (Table 2.5). Twenty-one days is the most common period required or recommended in Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore for special resolutions, and Viet Nam, which shows a similar trend to the global landscape, where 51% of the jurisdictions established a minimum notice period ranging between 15 and 21 days (OECD, 2023[6]). The ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard also has a question on whether a jurisdiction’s companies provided at least 21-day notices for annual shareholder meetings (A.2.13). Malaysia and Thailand recommend a longer 28-day notice in their corporate governance codes.13 Cambodia requires a 20-day notice with a maximum period of 50 days.

The eight jurisdictions commonly have requirements or recommendations on providing meeting materials at the same time as the notice of the meeting. In the Philippines, the Code of Corporate Governance for Public Companies and Registered Issuers states that “sufficient and relevant information” should be sent with the notice of meetings to encourage active shareholder participation.14 In Indonesia, when the agenda of the meeting concerns the appointment of members of the board of directors and/or commissioners, companies are required to make the curriculum vitae of candidates available on the company’s website.15 In Thailand, companies are specifically required to send the balance sheet to shareholders at least three days before the general meeting.16

Providing proper identification of shareholders eligible for voting

Corporate governance frameworks need to balance between ensuring the voting rights for shareholders who hold shares on the date of shareholder meetings, and considering companies’ burden for identifying and registering shareholders eligible for voting. If the record date, by when shareholders should be registered and identified, is too far from the shareholder meeting date, this weakens the shareholders’ right to vote. In cases where there is a long voting chain, the cut-off date could be even earlier than legal requirements due to deadlines set by service providers and custodians.

In the ASEAN region, several set record dates in company laws and regulations. In Indonesia, the regulation states that shareholders who are entitled to attend the meeting are those who are registered one business day before the invitation to the meeting.17 In Viet Nam, the list of shareholders entitled to participate in the meeting shall be compiled not more than 10 days before the invitation date.18 In Singapore, companies are not allowed, in their constitution, to require submitting documents to appoint a proxy more than 72 hours before a meeting.19

Ensuring that shareholders’ voting is counted properly and accurately

The Principles highlight the importance of shareholders being informed of the rules for general shareholder meetings, including voting procedures (II.C). The eight ASEAN jurisdictions commonly require or recommend the formal procedure for vote counting. In the Philippines, disclosure and clear explanation of voting procedures are recommended and poll voting is highly recommended as opposed to the show of hands.20 In Thailand, designating an independent party to count or audit the voting results is recommended for each resolution in the meeting.21

Electronic voting helps to ensure quick, accurate and efficient vote counting and facilitates equitable treatment of all shareholders. The Principles recommend secure electronic voting for both remote and in-person meetings (II.C.6). They also emphasise the importance of facilitating electronic voting in absentia (II.C.2), considering voting by proxies.

Several ASEAN jurisdictions refer to electronic voting processes, either as requirements, recommendations or making them optional. In Indonesia, listed companies are required to provide electronic voting systems for proxies.22 In Malaysia and Thailand, companies are recommended to leverage technology to facilitate voting.23 In Singapore, companies are allowed to facilitate real-time remote electronic voting,24 while in the Philippines votes through remote communication are allowed when authorised in the bylaws.25

Table 2.5. Voting process concerning the annual general meeting

|

Minimum notice period in advance |

Deadline for making meeting materials available |

Record dates of ownership |

Formal procedure for vote counting |

Electronic voting process (Required / Recommended / Optional / Not allowed) |

Disclosure deadline of voting results after AGMs |

Disclosure of number of percentage of votes for, against, and abstentions for each resolution |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cambodia |

20-50 days |

- |

20-50 days |

Required |

- |

- |

- |

|

Indonesia |

22 days |

22 days |

1 business day before the invitation |

Required |

Required |

2 business days |

Required |

|

Lao PDR |

5 days (21 days) |

5 day (21 days) |

- |

Recommended |

- |

(Immediately) |

Recommended |

|

Malaysia |

21 days (28 days) |

21 days (28 days) |

- |

Required |

Recommended |

Immediately |

Required |

|

Philippines |

21 days |

(21 days) |

- |

Recommended |

Allowed if authorised in bylaws |

(Next working day) |

Recommended |

|

Singapore |

14 days [21 days for special resolutions] |

14 days |

Cut-off date 72 hours before the meeting for appointing a proxy |

Required |

Optional |

Immediately |

Required |

|

Thailand |

7 days (28 days) |

7 days [3 days for balance sheets] |

21 days with prior notice (optional) |

Recommended |

Recommended |

(Next business day) |

Recommended |

|

Viet Nam |

21 days |

21 days |

10 days before the invitation |

Recommended |

Optional |

(1 day) |

Requested |

Key: ( ) = recommendation by the codes or principles; Immediately = within 24 hours. “-” = absence of a specific requirement or recommendation.

Encouraging companies to properly handle questions from shareholders

The Principles state that shareholders should have the opportunity to ask questions and describe that many jurisdictions have improved the ability of shareholders to submit questions in advance of the meeting and to obtain appropriate replies from management and board members in a manner that ensures their transparency (II.C.4). They also state that due care is required to ensure that remote meetings do not decrease the possibility for shareholders to engage with and ask questions to boards and management in comparison to when shareholders attend in person (II.C.3).

In Singapore, companies are recommended to allow shareholders at least seven calendar days after the publication of the notice to submit their written questions.26 In Malaysia, shareholders also can submit their questions prior to the meeting with a deadline and through a manner set by the company. Companies are advised to share those questions during the shareholder meeting.27 Also, it is recommended that all directors attend general meetings and all questions posed during the meeting should receive a meaningful response.28

Encouraging the disclosure of voting and meeting results

Seven out of eight ASEAN jurisdictions require or recommend disclosure of voting results soon after the general shareholder meetings, complemented by detailed minutes of the meeting. Companies are recommended to disclose questions asked and answers provided during the meeting in Lao PDR, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. Disclosure of board members who attended the meeting is required or recommended in Indonesia, Lao PDR, Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam. In the Philippines, when a substantial number of votes were cast against a proposal made by the company, the disclosed voting results may make an analysis of the reasons. Disclosure of minutes of the meeting and board attendance are also considered good practice in the ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard (A.2.7).

2.2.5. The corporate board of directors

Corporate government frameworks include various mechanisms to ensure that the board fulfils its functions. Board independence is essential for the board to exercise objective judgement. Board committees might support the board for a deeper focus on specific areas. To have sufficient capacity to supervise and oversee the company’s management, board members with appropriate qualifications and diverse views should be appointed through a transparent nomination and election process.

Board independence

To ensure proper monitoring of managerial performance while balancing demands on the corporation with wider scope and complexity, it is essential that the board is able to exercise objective independent judgement. While recognising a variety of approaches to defining independence, the Principles describe a range of criteria, including the absence of relationships with the company, its group and its management, the external auditor of the company and substantial shareholders, as well as the absence of remuneration, directly or indirectly, from the company or its group other than directorship fees (V.E).

The Principles also refer to ensuring the board’s independence from controlling shareholders. This is particularly important in ASEAN jurisdictions, due to high levels of concentrated ownership and the strong presence of company group structures. The role of independent directors in controlled companies is different than in companies with dispersed ownership structures, since the nature of the agency problem is different (i.e. in controlled companies the vertical agency problem between ownership and management is less common and the horizontal agency problem involving controlling and minority shareholders greater) (OECD, 2023[6]).

In jurisdictions with one-tier board systems, the objectivity of the board and its independence from management may be strengthened by the separation of the role of the chief executive officer (CEO) and the board chair. The Principles refer to the separation as good practice, because “it can help to achieve an appropriate balance of power, increase accountability and improve the board’s capacity for decision making independent of management” (V.E). In the ASEAN region, the separation between the CEO and the board chair is required in Viet Nam and recommended in Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand (Table 2.6). Singapore encourages the separation of the two functions through an incentive mechanism by triggering the application of a recommendation for a company to appoint a majority of independent directors when the chair is not independent. On the other hand, when the chair is independent of management, the required number of independent directors is reduced to one-third. In Indonesia, this separation occurs due to its use of a two-tier board system that does not allow for management to serve on the supervisory board.

Independence from substantial shareholders is also a key factor in the definition of independence of the board member, but national approaches vary considerably. Globally, while the large majority of the 49 jurisdictions covered in the Corporate Governance Factbook (2023[6]) include in the definitions of independent directors requirements or recommendations that they be independent of substantial shareholders (86%), the threshold for substantial shareholding ranges from 2% to 50%, with 10-15% the most common share (in 14 jurisdictions). Shareholding thresholds of “substantial” for assessing independence also vary across the ASEAN jurisdictions, from 1% in Cambodia, Thailand and Viet Nam to 20% in Indonesia (Table 2.6). Regulations in several jurisdictions also include the absence of a family relationship with the current board members, executives, or major shareholders (e.g. Singapore29).

Setting minimum numbers or ratios of independent directors is common across jurisdictions. In Indonesia’s two-tier board system, there are requirements on the minimum number and ratio of independent members of the Board of Commissioners that serve as the supervisory board. The independent criteria include the absence of business relationships with the company and not holding the company’s share either directly or indirectly. In cases where the supervisory board members are two persons, one of them should be an independent member. In the event that the Board of Commissioners has more than two members, at least 30% of them should be independent.30 Viet Nam also differentiates the minimum number of independent board members depending on the board size: a company should have at least one independent director if the board consists of one to five members, and at least two and three for the board size of six to eight and nine to eleven members respectively.

At the regional level, in the ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard, it is regarded as good practice that companies have a term limit of nine years or less or two terms of five years to be considered independent. In addition to serving as a criterion for the Scorecard’s assessment, the maximum tenure for a director to still be considered independent and the effect at the expiration of the term is also considered in many ASEAN jurisdictions’ definitions for board independence. The maximum term of office allowing for independence ranges from 9 to 12 years in all seven ASEAN jurisdictions. In Viet Nam, the maximum tenure of 10 years is set by governmental regulation while the code recommends nine years.31 In Thailand and Philippines, the maximum term of nine years is recommended by the codes while in Lao PDR the term is eight years.32 The ASEAN approach gives greater prominence to such criteria compared to the global situation, where only 57% (28 out of 49) of jurisdictions have such requirements or recommendations, ranging from 5 to 15 years (OECD, 2023[6]).

The details of the maximum tenure for a director and whether, at the expiration of tenure, the director is still regarded as independent, vary across the ASEAN countries. In Indonesia, the maximum term of office for independent supervisory board members, called commissioners, is two periods of the board term (maximum of five years for each period). Independent commissioners can be appointed for more than two periods as long as they explain why they consider themselves independent at the general shareholder meeting.33

Table 2.6. Board independence requirements for listed companies

|

Tiers |

Board independence requirements |

Key factors in the definition of independence |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Separation of the CEO and chair of the board (as applicable to 1-tier boards) |

Minimum number or ratio of independent directors |

Maximum term of office and effect at the expiration of term1 |

Independence from “substantial shareholders” |

||||

|

Requirement |

Shareholding threshold of “substantial” for assessing independence |

||||||

|

Cambodia |

1 |

- |

1/5 |

9 |

- |

Yes |

1% |

|

Indonesia |

2 |

- |

[30%] |

102 |

[Explain] |

[Yes] |

[20%] |

|

Lao PDR |

1 |

Recommended |

(1/3) |

(8) |

(No independence) |

No |

- |

|

Malaysia |

1 |

Recommended |

1/3 or 2 |

[12]3 (9)4 |

No independence Explain – re-designate as a non-independent director or adopt two-tier voting process |

Yes (major shareholder) |

10% or more of total number of voting shares in the corp.; or 5% or more of number of voting shares where such person is largest sh of corp. |

|

Philippines |

1 |

Recommended |

20% (1/3) |

(9) |

Explain |

Yes |

2%5 |

|

Singapore6 |

1 |

Recommended |

(Majority) [1/3] |

[9] |

[No independence] |

(Yes) |

5% |

|

Thailand |

1 |

Recommended |

1/3 or 3 |

(9) |

Explain |

Yes |

1%7 |

|

Viet Nam |

1+2 |

Required |

1 if board size is 1-5 members; 2 if board size is 6-8; 3 if board size is 9-11. (1/3) |

108 (9) |

Explain |

Yes |

1% |

Key: [ ] = requirement by the listing rule; ( ) = recommendation by the codes or principles; “-” = absence of a specific requirement or recommendation. For 2-tier boards, separation of the chair from the CEO is assumed to be required as part of the usual supervisory board/management board structure unless stated otherwise.

Note:

1. Maximum term of office and effect at the expiration of term refers to the maximum tenure for a director to still be considered independent and if, at the expiration of tenure, the director is still regarded as independent, or needs an explanation regarding her/his independence.

2. In Indonesia, the maximum term of office for independent supervisory board members (called commissioners in Indonesia) is two periods of the board term (with maximum of five years per period). Independent commissioners can be appointed for more than two periods as long as they explain why they consider themselves independent at the General Shareholder Meeting.

3. In Malaysia, the 12-year tenure limit took effect from June 2023 onwards. Notwithstanding the effective implementation of said requirement, listed companies with independent directors of more than 20 years (“affected long-serving IDs”) were strongly encouraged to expedite the replacement or re-designation of such directors as soon as possible before 1 June 2023. Should a company appoint a person who had before cumulatively served as an independent director of the listed issuer or any one or more of its related corporations for more than 12 years and observed the requisite 3-year cooling-off period, the company shall make an announcement to the exchange and provide a statement justifying the appointment of the person as an independent director and explaining why there is no other eligible candidate.

4. In Malaysia, Practice 5.3 of the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance recommends that the tenure of an independent director should not exceed a cumulative term of nine years. Upon completion of the nine years, an independent director may continue to serve on the board as a non-independent director. If the board continues to retain the independent director after the ninth year, the board should seek annual shareholders’ approval through a two-tier voting process. Under the two-tier voting process, shareholders’ votes at a general meeting will be cast to - Tier 1: only the Large Shareholder(s) of the company votes; and Tier 2: shareholders other than Large Shareholders votes. The decision for the above resolution is determined based on the vote of Tier 1 and a simple majority of Tier 2. The resolution is deemed successful if both Tier 1 and Tier 2 votes support the resolution. However, the resolution is deemed to be defeated where the vote between the two tiers differs or where Tier 1 voter(s) abstained from voting.

5. In the Philippines, the Code of Corporate Governance for Publicly Listed Companies (Explanation d. of the Recommendation 5.3) states that an independent director refers to a person who is not an owner of more than 2% of the outstanding shares of the covered company, its subsidiaries, associates, affiliates, or related companies.

6. In Singapore, a majority of independent directors is recommended for companies if the chair is not independent. The SGX Listing Rules previously required the appointment of independent directors who have served beyond nine years to be subject to a two-tier vote requiring approval by the majority of (i) all shareholders; and (ii) all shareholders excluding shareholders who also serve as directors or the CEO and their associates. These rules were amended on 11 January 2023. Under the new regime, the SGX Listing Rules require independent directors to be subject to a nine-year tenure limit. Independent directors who have served beyond such limit must be redesignated as non-independent at the next annual general meeting of the issuer, with effect from the annual general meeting held for the financial year ending on or after 31 December 2023.

7. In Thailand, a board member is considered independent if the person holds shares not exceeding one per cent of the total number of shares with voting rights of the applicant, its parent company, subsidiary company, associate company, major shareholder or controlling person, including shares held by related persons of such independent director.

8. In Viet Nam, the maximum term of office for independent board members is two periods of the five-year board member term, or 10 years.

Source: OECD (2023[21]), Corporate finance and corporate governance in ASEAN economies, https://www.oecd.org/corporate/background-note-corporate-finance-and-corporate-governance-ASEAN-economies.htm.

A number of jurisdictions have strengthened requirements and recommendations for maximum term limits. The framework in Malaysia could be characterised as having two layers, consisting of the listing rule and the recommendation by the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance. Under the listing rules, a director shall not serve as an independent director in a listed company or its related corporations for a cumulative period of more than 12 years. In addition, a company should disclose in the notice of the annual general meeting a statement justifying the nomination of an individual as an independent director, and explaining why there is no other eligible candidate, if such an individual had cumulatively served as an independent director of the company or any one or more of its related corporations for more than 12 years before and observed the requisite 3-year cooling off period (Bursa Malaysia, 2022[22]). Furthermore, the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance recommends that the tenure of an independent director should not exceed a cumulative term of nine years.34 Upon completion of the nine years, an independent director may continue to serve on the board as a non-independent director. If the board continues to retain the independent director after the ninth year, the board should seek annual shareholders’ approval through a two-tier voting process.

Singapore is another jurisdiction which has revised the regulation on this issue recently. Under the new regime effective from 2023, the SGX Listing Rules require independent directors to be subject to a nine-year tenure limit. Independent directors who have served beyond such limit must be redesignated as non-independent at the next annual general meeting of the issuer (SGX, 2022[23]).

Board-level committees

Setting up board committees may help and support the work of the board of directors. The Principles reflect the growing use of board committees while emphasising flexibility in their establishment (V.E.2). Among the traditional committees, including audit, nomination, and remuneration, audit committees are considered to be particularly important, reflecting their role in overseeing the relationship with the external auditor as well as the effectiveness and integrity of the internal control system.

All eight ASEAN jurisdictions have requirements or recommendations to set up the three committees with an independent chair and with a specific minimum number or ratio of independent members (Table 2.7). In Malaysia, financial institutions are required to have an independent chair for the audit, nomination and remuneration committees. In Viet Nam, when a company has a one-tier board, setting up the audit committee is mandatory. In this case, the company should have (i) at least one-fifth of the board being independent members, (ii) the chair of the audit committee being an independent member and (iii) all other members of the audit committee being non-executive members. In the two-tier board system, where the supervisory board is overseeing the board of directors, there is no requirement to have an independent member in the supervisory board.

The Principles do not provide specific recommendations on how often boards and committees should meet, because companies of different sizes, complexity and stages of development may have differing needs. Prescriptive requirements may also discourage companies from listing and benefiting from equity market finance. Establishing proportionate and flexible regulatory frameworks is a broad approach that the Principles take.

Several ASEAN jurisdictions have provisions about the minimum frequency of the meeting of the board as well as of audit, nomination and remuneration committees. In Cambodia, the board is recommended to hold a regulator meeting at least once every quarter.35 In Indonesia, the required frequency of the meeting is at least once per month for the board of directors (management board) and at least once in two months for the Board of Commissioners. The regulation requires the audit committee to meet more frequently (at least once in three months) than the nomination and remuneration committees (at least once in four months). Thailand is another jurisdiction with a recommended minimum frequency of meetings, six times per year for the board of directors, four times per year for the audit committees, and twice per year for the nomination and remuneration committees.36

Table 2.7. Board-level committees

|

Audit committee |

Nomination committee |

Remuneration committee |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Establi-shment |

Chair indepe- ndence |

Minimum number or ratio of independent members |

Establi-shment |

Chair indepe- ndence |

Minimum number or ratio of independent members |

Establi-shment |

Chair indepe- ndence |

Minimum number or ratio of independent members |

|

|

Cambodia1 |

L |

L |

Chair |

L |

- |

- |

L |

- |

- |

|

Indonesia 2 |

L |

L |

100% |

L |

L |

(33%) |

L |

L |

(33%) |

|

Lao PDR |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

|

Malaysia |

R; L (financial institutions) |

R; L (financial institutions) |

>50% |

R; L (financial institutions) |

C;L (financial institutions) |

>50% |

C;L (financial institutions) |

L (financial institutions) |

>50% |

|

Philippines |

C and L |

C |

(>50%) |

C and L |

C |

(>50%) |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

|

Singapore3 |

L R |

R |

>50% (50%) |

R |

R |

(>50%) |

R |

R |

(>50%) |

|

Thailand |

L |

L |

(100%) |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

|

Viet Nam4 |

L |

L |

Chair (>50%) |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

C |

C |

(>50%) |

Key: L = requirement by law or regulations; R = requirement by the listing rule; C = recommendation by the codes or principles; ( ) = recommended by the codes or principles; “-” = absence of a specific requirement or recommendation.

Note: