This chapter focuses on the essential aspects of responsiveness and accessibility of legal and justice services in Portugal, emphasising a people-centred approach. It elaborates on evidence-based planning for people-centred justice, discussing how a people-centred justice system ensures timely, appropriate, affordable, and sustainable legal and justice services that effectively address the population’s legal problems and needs. The chapter also outlines the benefits of systematic identification of legal needs, and the strategic use of data for planning justice services. It examines the current state of justice service planning in Portugal and calls for more comprehensive surveys and data-driven strategies to enhance the design and delivery of justice policies and services in Portugal.

Modernisation of the Justice Sector in Portugal

7. Enabling responsiveness and people-centricity of legal and justice services in Portugal

Copy link to 7. Enabling responsiveness and people-centricity of legal and justice services in PortugalAbstract

7.1. Evidence-based planning for people-centred justice

Copy link to 7.1. Evidence-based planning for people-centred justiceA people-centred justice system provides timely, appropriate, affordable, and sustainable legal and justice services that help people address their legal problems and needs. In a people-centred approach, proper services are available to all groups of people when and where they need them, ensuring their rights are safeguarded and that no one is left behind.

To attain this goal in a context where resources are usually scarce, legal services need to be planned to direct the most effective and efficient services to meet people’s needs in the right place at the right time. Planning and delivering justice services effectively require identifying the legal needs of the community in question, the areas where legal needs are greatest, and strategies to meet each different legal need (see Planning for the delivery of services in Chapter 2).

7.1.1. Towards p”eople-centred justice planning in Portugal

Copy link to 7.1.1. Towards p”eople-centred justice planning in PortugalAssessment conducted as part of this diagnosis report suggests that there is scope to advance in a people-centred approach to justice planning in Portugal. At present, it appears that justice service planning is primarily focused on financial accountability and funding processes, with limited attention devoted to planning services to respond to the needs of the community.

Identifying legal needs

Copy link to Identifying legal needsBuilding on a people-centred vision of purpose of the justice system, sound people-centred planning calls for systematic ways to identify legal needs of different groups of people. Portugal has taken an important step in this direction by conducting a legal needs survey in 2023, which provides important insights into the legal needs of the community. Portugal’s initiative in conducting this survey is commendable and the country is encouraged to undertake further surveys in the future to support an evidence-based approach to design and delivery of justice policies and services.

Locating legal needs

Copy link to Locating legal needsOfficial government data, including census and social security data, can serve as an important tool (see Locating legal needs in Chapter 2) to assist in locating likely areas of higher prevalence of particular legal needs. In this regard, Portugal has a unique opportunity to deepen the understanding of the legal needs of priority groups and to advance the design and delivery of people-centred justice services, considering the Social Security Institute (“Instituto da Segurança Social”, ISS) as part of the legal aid system. ISS has a wealth of knowledge and data on groups that are most vulnerable to legal problems. To this end, Portugal might consider a strategic planning partnership between ISS and DGPJ. This could provide a valuable source of information for planning of legal and justice services for vulnerable groups.

At present, the Portuguese government maps key legal service locations with the intent to assist people to identify their nearest services. There remains a need to understand which initiatives or services work most effectively and efficiently to meet which needs in order to support the tailoring of services for specific needs and for specific groups. To advance in people-centred justice planning, legal needs could also be mapped against demographic and vulnerable groups data to see whether services are geographically allocated to match users’ needs.

Matching services to needs

Copy link to Matching services to needsAn important part of the planning process is to make sure justice services reach the people that they are intended for. In the short term, Portugal may consider investing in strengthening the mapping of service locations and service coverage areas. In the longer term, through enhanced people-centred service data collection, Portugal could identify justice services, including types of services, delivered to user groups as identified by their demographic and other characteristics. This could provide the most effective means for ensuring that services are matched to the relevant need (see Annex D).

Monitoring and evaluation

Copy link to Monitoring and evaluationThere could be scope for Portugal to develop and implement a people-centred outcomes focus as part of monitoring and evaluation services to ensure that they are achieving positive outcomes for people. This would need to be supported by robust data.

Currently data collection in the administrative/service context appears to be primarily focused on a relatively narrow range of core performance indicators (e.g. cases in, time per case). Deepening the collection of people-centred data would allow policy makers to incorporate users’ data into the process of designing and delivering justice policies and services in Portugal. A summary of indicative data sources to support people-centred justice is provided in Box 6.1.

7.1.2. Mapping justice services

Copy link to 7.1.2. Mapping justice servicesWhen data is available, mapping justice services and service delivery data against legal needs data can provide valuable insights on the location of legal services in relation to their primary target communities (for ‘macro’-level mapping – see Annex D). In addition, this can be useful to indicate the coverage of legal services in relation to their primary target communities and the delivery of legal services to users contrasted against relevant target communities (see Annex D). Other benefits are helping identify the actual type and quantum of legal and justice services delivered in relation to the quantum of anticipated need in target communities (see Annex D); the (relative) gaps in service delivery by region or priority group; and the pathways people follow when seeking to resolve their legal problems.

Whether or not service delivery mapping is possible depends on the comprehensiveness, quality and availability of relevant data. Assessment conducted in this report suggests that justice agencies and service providers collect only data that is required by the relevant legislation, mandates and other directives. In addition, relevant legislation and directives are generally focused on the traditional court-performance “system”-type measures (e.g. cases in/cases finalised).

Notwithstanding the above, this report identifies two promising opportunities to develop mapping outcomes. These opportunities could lead to a positive development within Portugal in the long-term. They relate to further expanding and developing the mapping of services already undertaken by DGPJ. This includes, in particular, moving beyond service office location mapping to the mapping of services (and potentially services delivered) against indicators of legal needs in the community.

Another opportunity is to make use of the unique arrangement in Portugal whereby the Social Security Institute (ISS), with its broader responsibility for many social services across Portugal, is responsible for legal aid application assessments. ISS is in a position to potentially map a range of human indicators against legal aid relevant factors and perhaps broader justice variables (see Box 6.6). As part of fact-finding interviews, DGPJ informed that they have mapped the location of certain services for their website intended as a tool to allow people to identify the closest service to them (the effectiveness of which needs to be assessed). This suggests that they have the locations (street address and/or geocodes) for some/many/all justice sector facilities.

Interviews showed that the ISS seemed very open and keen to work with the Ministry of Justice, the DGPJ and other justice agencies to explore a partnership to make optimum use of the relevant data. In this regard, Portugal could consider exploring an appropriate relationship between the ISS and DGPJ and/or other elements of the justice system for making best use of available data to support the planning and implementation of people-centred justice.

Legal needs surveys across the globe have continually revealed that people’s vulnerability to legal problems parallels vulnerability to a range of other problems. Thus, the same segments of society that are most vulnerable to legal problems are very likely to be those same segments that are engaged with other social service agencies and processes (such as housing, health, unemployment), and thus ISS’s role in providing information about these groups and participating in planning processes could be a major point of progress for justice in Portugal.

It is also recommended to further develop current DGPJ work in mapping justice agencies. This should be expanded to facilitate the location and mapping of all justice and related service locations, including outreach offices and NGOs that provide services, and, where possible, to include the regional/geographic competence of these service offices to identify areas of and gaps in coverage.

7.1.3. Identifying what works

Copy link to 7.1.3. Identifying what worksIn the legal and justice field, there has been a limited focus on rigorous research and evaluation to identify “what works” to meet legal and justice needs of people (OECD, 2021[1]). In many jurisdictions, the situation is aggravated by the absence of common terminology, taxonomies, data protocols and analytical methodologies. These deficiencies are the product of a lack of continuity and coherence across changes in government and agendas over time, as well as the importance of guaranteeing the independence of justice institutions. Identifying “what works” is, therefore, a challenge in all countries.

Similar to other countries, there is scope in Portugal to identify a clear and co-ordinated strategy to identify strategies and mechanisms that help address the needs of people. Efforts can build on the various ongoing steps in the justice system in Portugal to identify and address bottlenecks and deficiencies in justice sector performance, including trials and pilots established over the last 10 years. Adopting an agile approach would help ensure that these ongoing initiatives are accompanied by appropriate evaluation mechanisms to help policy makers learn the lessons from the past. There appears to be an opportunity to further strengthen DGPJ leadership and co-ordination role. For example, their data team and associated components can help drive a more systematic and evidence-based approach to rethink and redesign justice policies and services.

One example in Portugal is the Victim Information and Assistance Office (“Gabinete de Informação e Atendimento à–Vítima” – GIAV), a local initiative undertaking specific research to understand the most effective approaches in the area of domestic violence in the context of court processes (see Box 7.1). A regular reporting and academic publishing programme, it aims to identify good practices and bring together the rigorous knowledge about good practices in criminal courts, notably in the context of domestic violence.

Box 7.1. Portugal: Some victims’ support initiatives

Copy link to Box 7.1. Portugal: Some victims’ support initiativesVictims Information and Support Cabinet (GIAV)

Copy link to Victims Information and Support Cabinet (GIAV)In 2011, the Victims Information and Support Cabinet was launched as a pilot project resulting from a co-operation between the Egas Moniz Higher Education Cooperative and the department of criminal investigation and prosecution of Lisbon. The project provides risk assessments of victims and alleged perpetrators on behalf of the public prosecutor in domestic violence court matters.

The GIAV undertakes work on a pro bono basis to support victims of domestic violence and children in and around the court proceedings. However, work is very limited for out-of-court proceedings. In addition, GIAV plans the process of psychological assessment and/or intervention in crisis, and connects the criminal justice system with quality research and good practices through engagement with international literature and initiatives.

The GIAV is a valuable service of dedicated and victim-focused assistance at a vulnerable time. Their service is likely to be well-received by victims, given that legal systems tend to be generally challenging and alienating for many members of the society who do not regularly come in contact with formal justice institutions.

Yet, the GIAV appears to be a “stand-alone” service, reportedly underfunded and with little indication of any change to current funding arrangements. Likewise, after operating for over 10 years, their services have not been subject to a systematic evaluation or any formal assessment, nor does one appear to be planned. Without such an evaluation, it could be difficult to make informed decisions about continuing and expanding this pilot to scale or otherwise.

Victim Support Offices (GAV)

Copy link to Victim Support Offices (GAV)The Victim Support Offices (GAV) in Portugal are establishments dedicated to aiding and supporting individuals affected by crime or traumatic events. These offices offer various services to assist victims, including emotional support, guidance through legal procedures, information about their rights, and referrals to other support resources. They often operate in collaboration with governmental bodies, law enforcement, and victim advocacy organisations to ensure a comprehensive and holistic approach to supporting those affected by crime.

In March 2019, six new Victim Support Offices (GAV) were installed in the departments of investigation and prosecution (DIAP) of Braga, Aveiro, Coimbra, Lisbon West, Lisbon North and Faro. These offices are co-ordinated by a public prosecutor and composed of a victim support worker and a court clerk. Their main goal is to ensure assistance, information, support and personalised referral to victims of domestic and gender violence.

Unlike the GIAV, which results from a partnership between the Lisbon department of investigation and prosecution and a higher education institution, the model used for these new victim support offices has a tripartite structure. It involves the Ministry of Justice, the Attorney General's Office and victim support organisations that select and make available victim support officers for each of the offices.

Source: Neves et al. (2015[2]), Gabinete de Informação e Atendimento à Vítima (GIAV) - Espaço Cidadania e Justiça, https://comum.rcaap.pt/bitstream/10400.26/8786/1/Poster03_IAlmeida_2015.pdf; Government of Portugal (2019[3]), Protocolo entre o Ministério da Justiça e a Procuradoria-Geral da República, https://www.ministeriopublico.pt/sites/default/files/anexos/protocolos/protocolo_mj-pgr.pdf.

In a context of limited resources, it is important to implement strategies and service delivery models that produce the best results at a minimum cost. Focusing on identified people-centred justice system priorities, Portugal would benefit from a co-ordinated monitoring and evaluation programme using service data to address gaps and identify good practices.

7.2. Facilitating a responsive, accessible justice and people-centred justice systems

Copy link to 7.2. Facilitating a responsive, accessible justice and people-centred justice systems7.2.1. Fairness, effectiveness, satisfaction and responsiveness

Copy link to 7.2.1. Fairness, effectiveness, satisfaction and responsivenessIdentifying effective strategies to meet the legal and justice needs of people is an essential part of establishing not only a people-centred justice approach but also a justice system that achieves the best outcomes possible within the limited resources available. User satisfaction surveys and follow-on evaluation research are important parts of this process.

Fact-finding interviews revealed that there is limited engagement of justice stakeholders in evaluating outcomes and assessing user satisfaction. The primary emphasis is on measuring court performance indicators (e.g. cases in, cases finalised), while outcome or user satisfaction measurement are rare. One notable example is the DGPJ initiative to start measuring user satisfaction of ADR services.

In terms of the findings from the 2023 Portuguese LNS on fairness, effectiveness, satisfaction and responsiveness, the results paint a challenging picture of the services and pathways available to people to resolve their legal and justice problems. In a nutshell, from the sample of 1 500 people, 505 experienced at least one legal or justice problem, and the processes they followed to resolve their problems were considered costly by most people, time consuming, and often unfair. A majority of respondents lacked knowledge of their rights, found it difficult to find good information and assistance, and were not confident that they could achieve a fair outcome.

Regarding the 314 respondents whose problem had been resolved during the two-year reference period, and who had been involved with a legal process/decision maker to resolve the matter:

74.6% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “both parties had the same opportunity to explain their position”;

66.2% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “the justification for the decision was clearly explained to you”;

55.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “they were represented by a lawyer, other advisor, or other independent person/organisation”;

63.7% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “the process was fast and efficient”;

76.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “the process was affordable”.

Despite these detailed and often negative responses, when the same 314 respondents were asked about the fairness of the process (regardless of the outcome):

a majority (58.9%) responded that they believed it fair to everybody concerned;

a substantial minority (41.1%) responded that it was not fair to everybody concerned.

Regarding 505 respondents who had experienced at least one legal or justice problem, further questions on fairness, effectiveness, satisfaction and responsiveness found:

84.7% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “they understood or came to understand their legal rights and responsibilities”;

80.2% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “they knew or came to know where to get good information and advice about resolving the problem”;

65.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “they were able to get all the expert help they needed”;

70.9% disagreed or strongly disagreed that “they were or are confident that they could achieve a fair outcome”.

7.2.2. Awareness of services and pathways

Copy link to 7.2.2. Awareness of services and pathwaysPeople’s awareness of their legal rights, institutions and pathways to resolve legal problems and enforce their rights is an important element of an effective justice system. People’s awareness is an indication that they can readily navigate through the justice system to address legal issues. Apart from providing a range of appropriate services, a people-centred justice system has mechanisms to build people’s awareness of how to address their problems and who they can turn to for assistance and resolution. In addition to general education and knowledge conveyed through education systems, community information and education campaigns, a people-centred justice system features systems of triage, including problem identification and referral, to help people make use of the available and most appropriate services (OECD, 2021[1]).

People’s awareness of services and pathways may often be assumed by those working inside justice systems or institutions. However, that assumption is often incorrect, given that ordinary people with little or no court or justice system experience may have little awareness of legal processes, institutions, pathways and obstacles (see Box 7.2).

Box 7.2. Capturing awareness of justice services

Copy link to Box 7.2. Capturing awareness of justice servicesAwareness can be difficult to measure. Service users are aware of the existence of the services they use. But not much is known about non-users’ awareness of justice services. In this regard, administrative data has limitations on the insights it can provide about broad awareness. People-centred data can help reveal, for example, about groups, locations and particular circumstances when people become service users. Likewise, justice data can also provide some insight into which groups are not represented, or underrepresented, among certain justice services.

While service data records only services delivered to those who are aware of them, if well collected across the sector and by each organisation, valuable insights can be gathered about those who do not use and, thus, who might not be aware of justice services. This is particularly relevant when service providers are targeting particular groups, such as autochthonous populations, people with disabilities, refugees, and people of particular ethnic backgrounds.

While a lack of awareness about the service is only one possible cause for underrepresentation in services, it can be an important contributing factor. An example is the service-mapping Portuguese Association for Victim Support (APAV) conducts and publishes annually. In its annual report, APAV counts the number of registered victims and calculates the percentage of services provided for each region. By mapping their users and service users by region, they can readily identify which regions provide no users or have fewer users than they might have expected. They can also get a better knowledge of the population that uses its services and provide a more targeted protection and support for people who are victims of criminal offenses.

APAV data allow to identify potential gaps between expected and effective service delivery, given other factors such as demographics and crime data. The lack of physical services in certain regions may, of course, be a factor in the low number of users. However, given the growth of online and remote service delivery, it can also reveal a lack of penetration of communications strategies into those regions, with the resulting reduced awareness of their services.

Source: APAV (2022[4]), Estatísticas APAV Relatório Anual 2021, https://apav.pt/apav_v3/images/press/Relatorio_Anual_2021.pdf.

The 2023 Portuguese LNS provided key findings on people’s awareness of services and pathways. Beginning with an ‘unprompted’ question (that is, respondents were not ‘prompted’ with the names of any organisations), only 640 respondents out of 1 500 (43%) were able to identify any organisation that could provide accessible and low-cost advice or assistance to deal with a legal problem. By clear margins, more respondents were able to identify two NGOs, DECO (18%) and APAV (12%) than any other agency. The police, the next highest, were nominated by only 5% of respondents. Only 3.9% of respondents identified the Social Security Institute (ISS), which is the pathway to apply for legal aid in Portugal. Response rates were the lowest for courts (2.5%), lawyers (2%), the ombudsperson and Public Prosecution Service (1.8%) as places identified to go for assistance in resolving legal problems.

When respondents were then ‘prompted’ and asked if they knew anything about what selected (named) justice and related agencies did to help people to resolve problems, results showed that DECO (83%), Social Security Institute/legal aid (80%), APAV (78%), the Authority for Work Conditions (ACT) (70%) and trade unions (69%) displayed reasonable awareness levels, suggesting employment matters are sufficiently prevalent for the Portuguese population. Only about two-thirds of respondents (66%) seemed to know about the role of the public prosecutor. For the ombudsperson, numbers dropped to only 54%. Perhaps impacted by the limited geographical coverage of the justice of the peace courts, only 641 respondents (43%) were able to nominate them, even when prompted.

When respondents who had experienced at least one legal problem but had not sought advice or assistance were asked why they did not seek advice or assistance, only 3.1% indicated that they “did not know how/where to get advice”. However, also relevant was that others did not seek assistance because of concerns about financial costs of assistance (9.4%), did not think getting assistance would be effective to the outcome (6.6%), were concerned how long it would take to receive assistance (6.6%), or believed that advisors were inaccessible (1.4%).

Fact-finding interviews revealed strong assumptions by many justice stakeholders about people’s awareness and knowledge of the justice system in Portugal. These assumptions generally manifested in an overreliance on certain sources of information such as the “parish” or the Ministry of Justice’s official website, without clear evidence that most people know or use such resources. Likewise, assumptions also manifested in the awareness of justice services among the community. Interviews with public sector stakeholders also highlighted assumptions that people knew justice services were available, and that there was no or limited need in awareness-raising initiatives or in monitoring pathways to legal and justice services.

Awareness of different services in Portugal

Copy link to Awareness of different services in PortugalThe following sections provide information to illustrate some challenges in people’s awareness and knowledge of the justice system in Portugal. It also examines the potential impact of limited awareness on the effectiveness of these services in addressing legal needs and supporting victims in Portugal.

National public prosecutor’s office

Copy link to National public prosecutor’s officeInterviews suggested that people lack awareness of the public prosecutors’ roles, unless they have had some connection to it. Findings from the 2023 Portuguese LNS seem to support this view. Results show that when unprompted only 1.8% of respondents nominated the Prosecutor’s Office as a place to go to resolve legal problems. Even when prompted by naming the office, only about two-thirds of the respondents indicated they “knew what they did in relation to helping people solve problems”.

RIAV service

Copy link to RIAV serviceWhile local police are responsible for informing potential victims of the RIAV service (where it is available), stakeholders indicated that in many cases “it was not the victim’s first time to use the service”. This suggests that victims who had previous experience of the RIAV service were happy to return to it, but from an “awareness” perspective it paints a more ambiguous picture. It appears that people who have been to and experienced a service are “aware” of it. Yet, it is unclear if a high number of repeat users suggests poor awareness of the service among those who have not yet experienced it. Note also that RIAV was not mentioned by any respondents in the 2023 Portuguese LNS, although some respondents may have simply included this service within a “police” response.

Estimating the awareness of the RIAV service among its target potential group – victims of domestic violence – could be further complicated by the fact that at the time of the fieldwork and legal needs survey research few services (four) were available across the country. A similar challenge to awareness confronts the justice of the peace courts.

Justice of the peace courts

Copy link to Justice of the peace courtsFact-finding interviews suggested that some stakeholders believe the justice of the peace courts are not well-known and, as a result, performing below their potential. This appears to be reflected in the 2023 Portuguese LNS findings. Only 18 respondents out of 1 500 (1.2%), when unprompted, identified justices of the peace courts as a potential source of affordable information, advice or assistance when facing a problem. When prompted, only 43% were able to confirm that they knew something about their role in helping people to resolve problems.

The Council of Justice of the Peace courts’ last annual report highlighted the need for greater dissemination of the work of justice of the peace courts (Conselho dos Julgados de Paz, 2022[5])). Fact-finding interviews suggested that up to that point no central and systematic communication activities had occurred after the initial period of creation of justice of the peace courts. Most communication efforts after that initial period have been undertaken by the individual courts and on their own terms. However, following the end of fact-finding interviews in 2023, a national publicity campaign was launched to publicise and promote ADR services, including the justice of the peace courts. The campaign included TV spots, street posters, social media campaigns and local media. This campaign involved partner municipalities.

At the local level, fact-finding interviews suggested that awareness of the justice of the peace courts in Bombarral was reliant upon the Ministry of Justice website and the long-past local awareness-raising initiatives conducted when the courts were first created with the municipality. The recent publicity campaign aside, local awareness-raising initiatives seem to be infrequent, if occurring at all. Importantly, despite the overall assumption of people’s awareness revealed in fact-finding interviews, a few stakeholders emphasised the need for greater community engagement and called attention to the lack of knowledge in Bombarral about the role of justice of the peace courts.

It is acknowledged, however, that the lack of national coverage is a barrier to effective communication. Apart from the obvious absence of any local “word of mouth” effects in what is probably 85% of the country (territorially) that does not have access to a justice of the peace court, this small coverage has likely prevented effective national communication strategies. Even with law students, it is perhaps understandable why justice of the peace courts may get little mention in course curricula if they are present in few regions and thus few future law graduates (in current circumstances) expect to use these courts.

Proximity sections of judicial courts

Copy link to Proximity sections of judicial courtsFact-finding interviews suggested that awareness of the proximity court is reliant upon the fact that “it is defined in the law”, that the court “is on the Ministry of Justice website”, and that these courts are usually in “small towns and people would know about the services by word-of-mouth”. However, during the project there appeared little sign that many local people were using the service. Likewise, stakeholders indicated that the permanent staff (court clerk) on site was only “kept busy” through remote work on other, regional justice tasks.

Proximity sections of judicial courts are potential local sources of information and assistance for people across the country. Day-to-day functioning of these courts should, ideally, include the role of a key local hub for legal information, guidance about processes, and referrals. However, it appears that they are not recognised for such a role in the community. Only 2.5% of respondents from the 2023 Portuguese LNS chose, unprompted, all/any courts as a place to go for such information and assistance. Further, it is worth noting that only two respondents out of 1 500 chose, unprompted, the Ministry of Justice as a source of information and assistance. Therefore, results suggest that relying on the ministry’s website might not be an effective method.

Awareness of community organisations

Copy link to Awareness of community organisationsFact-finding meetings revealed that some non-governmental organisations in Portugal benefit from widespread recognition. For example, the APAV and DECO are both featured widely in metro stations in Lisbon and other advertisement channels. Likewise, people consulted at the diagnosis phase seemed to be aware of these organisations and their work.

The 2023 Portuguese LNS confirmed the relatively high level of awareness of DECO and APAV suggested during the field mission. Other parts of the justice system might learn valuable lessons from the DECO and APAV models.

Ensuring that there is good awareness of legal rights and of the services available to assist people to resolve their legal problems is a key component of a people-centred justice system. This is closely linked with understanding the legal needs of the people and the pathways that they presently follow when confronted with legal problems. It is also an important part of seeking to connect the right services to the right users for their particular problems, achieving optimum outcomes at a minimum cost.

Portugal would substantially benefit from devoting more attention to communication strategies and awareness-raising about legal and related services for the population. Confirmed both by the 2023 Portuguese LNS and fact-finding meetings, lack of awareness may well be a significant contribution to the apparent underusage of proximity services such as justice of the peace courts and the proximity sections of judicial courts. More broadly, the common assumptions that people know about and utilise available services, without any evidence to confirm such assumptions, might influence undercommitment to better communications and legal information strategies.

7.2.3. Awareness and accessibility of legal aid

Copy link to 7.2.3. Awareness and accessibility of legal aidThe application process for legal aid through the social security system is fairly unique in Portugal. As in other countries, legal aid is primarily available for those lacking sufficient financial resources and capabilities to manage legal problems themselves or afford a lawyer, or for those experiencing a particular disability or disadvantage. As previously mentioned, disadvantaged people who are likely to require legal assistance when confronting legal problems are often highly represented among the users of social security and other social services (e.g. health, housing, homelessness services). Therefore, the link between legal aid applications and ISS appears to be logical.

Similar to awareness (or not) of justice services, fact-finding interviews captured some potential assumptions from justice institutions and officials regarding people’s awareness of potential eligibility and the application process for legal aid. Fact-finding interviews revealed that some stakeholders had a general sense that most people in Portugal are reasonably aware of how to apply for legal aid. Rather than empirical evidence, this general sense was supported by feelings or assumptions that information and referrals from official government websites, the Bar Association, individual lawyers and community groups could be sufficient to render people aware of eligibility criteria and the application process for legal aid.

Many justice sector stakeholders appeared to take quite a “hands-off” approach and simply referred people to ISS. There also appeared to be limited follow-up with potential users to later understand whether, in fact, they accepted the referral and proceeded with the application for legal aid. Interviews also suggested that parish boards, the lowest level of local government, often take the responsibility for providing people with a range of information, administrative advice and assistance (e.g. filling out applications). Often, stakeholders mentioned in interviews that the parish boards were the place that refer people to legal aid and help them with the application process.

In contrast, some of the non-governmental stakeholders interviewed highlighted that there could be limited general awareness among the population both of the existence of the legal aid option, and how to actually apply for it. Some of them suggested low general awareness of the availability of legal aid and, importantly, low awareness about how to actually apply for it. For example, one major NGO reported that their single most common task was assisting people to fill out application forms for legal aid. This reinforces the need for a sector-wide communication and awareness strategy.

Another issue raised in interviews with non-governmental stakeholders is the complexity, and therefore limited accessibility, of the application process for legal aid. While simplification of these processes could be useful, some level of complexity and detail cannot be avoided. Therefore, the accessibility of legal aid would also be influenced by the availability of assistance for potential legal aid applicants in completing their application process effectively. It is noted that in early 2023 the application process for legal aid went online. A regular review of the legal aid application process would serve to ensure that people most in need are, in fact, benefitting from legal aid.

7.2.4. People’s pathways of action for dispute resolution

Copy link to 7.2.4. People’s pathways of action for dispute resolutionLegal systems are complex, and while legal and justice problems are a constant across people’s lives, few people have frequent or even any engagement with formal justice systems. Thus, when people experience legal or justice problems, a people-centred justice system is one where ordinary people can readily identify and reach the appropriate service to address their needs.

Understanding the pathways people follow in response to legal problems is therefore an important element in the quest to understand the effectiveness of justice services and how responsive they are dealing with people’s needs.

Triage is part of the justice pathway which aims to connect people as efficiently as possible to the most appropriate service for their particular needs and circumstances (OECD, 2021[1]). Triage can occur at a systemic level. For example, in New South Wales, Australia, all people can contact the LawAccess telephone and online service to discuss their legal issues and be referred to an appropriate service. Access to state-funded legal aid is another example of systemic triage, as applicants are triaged by matching their circumstances with defined eligibility criteria, including financial status. Examples include Legal Aid of Nebraska’s LawHelp Nebraska online intake and triage system (Wiens, 2019[6]) and Portugal’s Social Security-run triage system for applicants for legal aid.

Triage can also occur at the individual service organisation level whereby users are first engaged and assessed in relation to the nature of their needs and the most appropriate type of services for them. For example, the state court of Alaska has a two-level triage approach with its family law self-help programme, based on an assessment of the likelihood of settlement, while taking into account a range of factors such as domestic violence (DV), the presence of children, etc. (Coumarelos and McDonald, 2019[7]). Similarly, in Singapore, the state courts of Singapore offer an online assessment tool for small claims to guide the parties in their decision-making process. The tool provides a preliminary assessment of whether a dispute falls under the jurisdiction of small claims tribunals (OECD, forthcoming[8]).

In Portugal, examples of institutional triage include the RIAV services, where victims of domestic violence are supported and triaged. In RIAV, service is provided not just for the legal aspects of their domestic violence complaint but also for referral onto housing, psychological and other support services needed (see Box 7.3). Another example is the APAV, where a sensitive but comprehensive and user-focused induction process is followed to ensure all relevant issues and needs are identified so that action, including referral, can occur.

Box 7.3. Integrated Victim Support Response (RIAV)

Copy link to Box 7.3. Integrated Victim Support Response (RIAV)Integrated Victim Support Response (RIAV) is a relatively new public security programme intended to better support victims of domestic violence and abuse at the time of complaint. Until February 2023, there were only four of such services in Portugal, three of them in the Lisbon region. These services are intended to provide a specialist-trained police service to potential victims of domestic violence. Victims can either report their complaints to local police or to the RIAV service, if available.

This service appears to have an important potential, although with limited resources. At the same time, the diagnosis phase could not determine whether there is a funded plan for a robust assessment and evaluation of the service to determine whether its funding should be increased and taken to scale across the country. As such, there is strong scope for an evaluation of its effectiveness in order to identify necessary and sufficient resources.

Source: Municipality of Lisbon (2022[9]), Espaço Júlia acolhe em Lisboa vítimas de violência doméstica, https://www.lisboa.pt/atualidade/noticias/detalhe/espaco-julia-acolhe-em-lisboa-vitimas-de-violencia-domestica.

Yet, as discussed earlier, limited data are collected in relation to users’ pathways and referral. Some examples of service and referral data collection come from the RIAV and APAV services. However, currently, this is not done as part of a systematic process to understand overall users’ pathways.

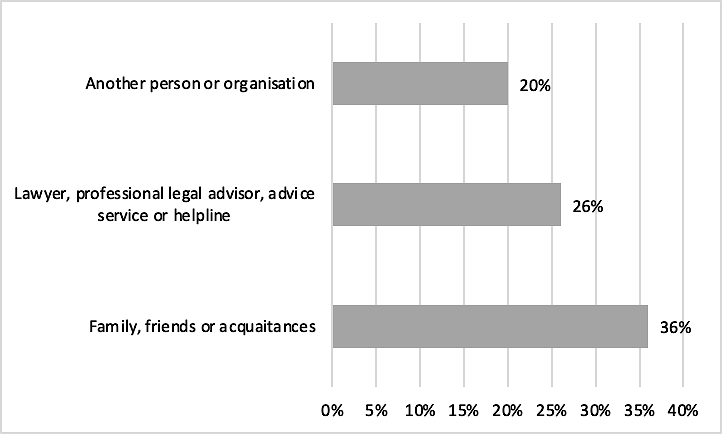

The 2023 Portuguese LNS contributed with some insight to understand the pathways people follow when confronting legal problems. In particular, the survey has asked questions in relation to awareness of legal services, obtaining assistance and information, problem resolution, use of dispute resolution services, and institutions that made the final decision. Survey results revealed important findings in these areas. Concerning seeking assistance, among the 505 respondents who experienced at least one problem, for 36%, assistance was sought from family, friends or an acquaintance (see Chapter 3); for 26% of respondents, assistance was from a lawyer, professional legal organisation or online advice service; for 20%, assistance was sought from another person (e.g. a doctor, pharmacist, schoolteacher).

It is important to note that respondents were able to report multiple sources of assistance. Importantly, for only 215 problems (42.6%) was assistance sought, and for 287 problems (56.8%) assistance was not sought. It is important to note also that of the 186 problems for which assistance from friends, family or acquaintance was sought, 68 of these (37.2%) also included seeking assistance from other sources (e.g. lawyer, legal organisation, doctor, pharmacist).

Concerning problem resolution, only 186 of the 505 problems examined had been taken to one of the formal dispute resolution mechanisms. The police was referred to the most often (75 or 14.9%), followed by courts or tribunals (59 or 11.7%) and government or municipal officer (41 or 8.1%). The lowest number of problem resolution referrals were to formal complaint or appeal processes (30 or 5.9%), online third-party complaints mechanisms (14 or 2.8%), and ombudsperson (14 or 2.8%).

While data and analysis limitations suggest caution should be exercised when considering these pathway findings, preliminary descriptive analysis of the 2023 Portuguese LNS suggests that those who went or were referred to the police for resolution were more likely to have obtained advice from “other people” (e.g. doctor, pharmacist, schoolteacher). Respondents who went or were referred to courts or tribunals for dispute resolution appeared more likely to have obtained advice from a lawyer, professional legal organisation or online advice service. Survey results also suggest that those who went or were referred to government or municipal authorities for dispute resolution were slightly more likely to have obtained advice from “other people”, and family, friends and acquaintances. Finally, descriptively, the data suggest that the respondents who went or were referred to formal complaint mechanisms for resolution were more likely to have obtained advice from family, friends and acquaintances.

The actual problem resolution decisions paint yet another picture. For problems that were resolved, government or municipal authority (77 or 24.5%) was the most frequently cited. This group was followed by online third-party complaints or dispute resolution mechanism (45 or 14.3%); formal complaint or appeal process (34 or 10.8%); and formal mediation, conciliation or arbitration process (29 or 9.2%). Courts and tribunals (28 or 8.9%) and the police (22 or 7%) were among the least consulted decision maker for resolving problems (see Chapter 3).

Results from the 2023 Portuguese LNS show that people do not universally turn to lawyers or other legal advisors when confronted by day-to-day legal problems. Assistance from a lawyer or legal agency was sought for only in 132 (26%) of the 505 legal problems examined. This can be compared to the 183 (36%) for which advice from family, friends or acquaintances was sought.

Another important finding is that relatively few disputes (8.9%) were resolved through court processes. Government and municipal authorities, online third-party dispute resolution and complaint mechanisms, formal complaint processes and ADR processes of mediation, conciliation and arbitration all featured in the higher frequencies of decision-makers.

When combined with relatively low awareness levels discussed earlier in this report (see Awareness of services and pathways), the 2023 Portuguese LNS results prompt some important observations. First, results demonstrate the value of a properly conducted LNS for pathways analysis. Importantly, only with a large enough representative sample of the population is it possible to get a reliable picture of issues such as awareness of services, types of assistance sought to resolve legal issues, and what people do and where they go to resolve their problems. LNS can also provide insight into those that do not go to resolution for legal assistance agencies.

Yet LNS cannot give a detailed picture for specific services and areas of law in specific regions. Administrative service data also has its own limitations, as it only can reveal information about the pathways of people who actually used a certain service. Nevertheless, if properly collected, administrative service data is an avenue for gaining more detailed insight about the use of particular services and outcomes obtained.

7.2.5. Making services accessible

Copy link to 7.2.5. Making services accessibleThe people-centred requirement that services be accessible to all people is a complex and nuanced concept, which includes a number of different dimensions such as service awareness noted above. In addition, accessibility of services calls for proximity, appropriateness, timeliness, and referral.

In terms of proximity, there are many service types, such as legal representation, that are often best delivered face-to-face, notwithstanding the growth in online technologies. Also, for many members of some demographic groups, such as older people and indigenous groups, face-to-face service delivery can be important. Proximity might also imply proximity to a relevant third-party organisation or person who might assist a person with legal needs to access an appropriate service. Many disadvantaged people with other needs (e.g. medical, housing, financial) may be in ongoing contact with key government or NGO services that assist them with their other social service needs, and these agencies may also be good places to assist such people to access legal services.

Importantly, proximity of services can also contribute to broader community awareness of those services. For example, if a legal assistance service is regularly seen by people as they go about their daily lives (e.g. shopping, education, public transport), then they are more likely to be familiar with the service and to make use of it. Simply put, geography, distance from services, and the convenience of services remain a factor in accessibility.

Additionally, for legal services to be accessible and usable for the target groups, they must be appropriate in the place and manner of delivery for that particular person or group. Depending on the group and the nature of the problem, services may need to be delivered face-to-face, by telephone, online, through interpreters, or with the assistance of social workers or counsellors if the potential users are older people, people with disability or people with mental illness. For some people, full case support including representation will be required, while for others minor assistance and the delivery of selected “unbundled” services may suffice. Therefore, services must be those that match the user’s legal need and capability.

In terms of timeliness, it is observed that numerous individuals, particularly those with complex life circumstances, tend to not seek assistance at the initial signs of an issue. Instead, they often delay action until a problem has significantly progressed (Pleasence, 2014[10]). This pattern is reflected in the provision of many legal services, which are frequently offered on a "just-in-time" basis rather than on a “just-in-case” basis. Despite the preference of governments and service providers for early intervention due to its enhanced efficiency and effectiveness, the reality remains that certain segments of the population, often those at a disadvantage, are more likely to seek legal aid or conflict resolution at a much later stage. This is often beyond the point where early intervention strategies would be most effective. Consequently, the design and delivery of services must be adapted to accommodate these late-stage interventions.

Finally, there need to be effective triage and referral networks to ensure people in need reach appropriate services (or appropriate services reach them) in a timely manner. For reasons that may include lack of awareness or poor proximity, people facing legal problems and in need of assistance will not necessarily arrive at the appropriate legal service. Instead, they often arrive at other social service locations or legal service providers. For example, many disadvantaged people with legal problems are also in contact with social security services, health services, employment services, and housing services. For services across the continuum to be accessible, people with legal needs must be triaged and effectively referred to the appropriate service.

Bringing these dimensions together, governments and service providers should design and provide services that are:

Targeted to the particular groups in need,

Joined up sufficiently with other services to provide effective pathways,

Timely, and

Appropriate to the needs and capabilities of users (Pleasence, 2014[10]).

In order to evaluate the accessibility of services for their intended target groups, it is essential to collect relevant people-centred data and conduct a comparative analysis between the characteristics of service users and the target groups.

7.3. Governance for people-centred justice in Portugal

Copy link to 7.3. Governance for people-centred justice in PortugalThe OECD Recommendation of the Council on Access to Justice and People-Centred Justice Systems and the OECD Framework and Good Practice Principles for People-Centred Justice (OECD, 2023[11]; OECD, 2021[1]) highlight the need for an overarching justice system purpose that emphasises placing people at the centre of justice-system planning, development, service delivery, and all reform implementation. This people-centred purpose is discussed in Chapter 1. Importantly, this overarching purpose also, in particular, underpins the elements of the system of government guiding people-centred justice implementation, including:

The establishment of priorities for investment and reform

The professional practice and regulation of the legal profession.

7.3.1. Setting and maintaining priorities for investment and reform

Copy link to 7.3.1. Setting and maintaining priorities for investment and reformOver the last 10 - 15 years, Portugal has developed and is implementing an ambitious agenda to transform its justice system, including towards people-centricity. The range of initiatives under the Justiça + Próxima programme, developments in alternative dispute resolution, increasing use of technology and fostering of digital transformation are examples. In this reforming work, top-down guidance is essential (OECD, 2023[11]; OECD, 2021[1]).

At the same time, from a people-centred justice perspective, initiatives (including trials, pilots and specific reforms) at lower levels are also essential as they are an avenue to identifying effective solutions and pathways for individual members of the community to address their legal needs. Investigations as part of this project identified a number of such local-level initiatives or trials, including a number of different initiatives in domestic violence services (GIAV, RIAV, NGO-delivered services, and some formal justice system elements bespoke tech initiatives). These reforms and innovations demonstrate the willingness of people across the justice sector in Portugal to identify areas for improvement and initiate action and innovation to bring about the improvement. This willingness is positive and should be commended.

However, there is room to reap more benefits from this willingness for innovation and improvement through the streamlining of resources, and the improvement, co-ordination and clarifying of priorities. For example, there appear to be a number of pilots that have continued for up to 12 years but have, as yet, not been evaluated. Accordingly, authorities are missing opportunities to endorse the approach and take it to scale or to end the initiative and divert resources to new approaches if the intervention is evaluated negatively. A lack of co-ordination in the resourcing of these initiatives may also lead to some not being fully completed and implemented.

A significant observation from project investigations was that there did not appear to be a clear, agreed and clearly understood set of actionable priorities across the sector that could facilitate realistic and achievable reform action across the justice system. Likewise, there is limited co-ordinated resource allocations to facilitate these reforms. Co-ordination of priorities for budget expenditure across the whole justice sector would not only lead to more efficient and cost-effective outcomes but also allow for the creation of justice system-wide processes that reflect a people-centred approach.

Better co-ordination of priorities and investments is more likely to lead to the delivery of holistic services that meet the legal needs of the community. People rarely have just a single legal matter but often experience a range of life problems that cross jurisdictions and government department responsibilities. A people-centred justice system, therefore, needs to provide for the flexible entry of people and their legal problems to the broader justice sector from other sectors and allow for them to be transferred between services. Government actions would yield better results with a more consistent and comprehensive range of co-ordination and prioritisation of investment across the whole justice sector.

Overall, there is scope to establish or clarify a set of actionable priorities to facilitate realistic, co-ordinated and achievable reform action and co-ordinate scarce resource allocation across the justice system. Clear priorities assist in the efficient allocation of scarce resources. Consistent guidelines and better coordination between government portfolios and related services also assist the efficient allocation of scarce resources and is essential for the implementation of agreed priorities.

7.3.2. Regulating legal representation in Portugal and its impact

Copy link to 7.3.2. Regulating legal representation in Portugal and its impactLegal representation is an essential element of any justice system seeking to protect the rights of individuals and uphold the law. It also contributes to the effective and efficient operation of the courts and the justice system, ensuring matters can be disposed of efficiently, with the view to ensuring costs for all parties are kept as low as possible (through not having extended proceedings), and promoting fairness in legal processes. However, while effective and truly accessible and available legal representation and advice is essential, especially in serious matters, it comes at a substantial cost – to individual parties and sometimes to the state. There will always be circumstances and cases where one party can afford to engage ‘more’ and/or ‘better’ legal representation than the other party. Often one party to a legal dispute (and sometimes neither party) will be able to afford sufficient legal representation, or perhaps none at all, and yet legal aid will not be available for them in this matter. People who may be unable to afford legal representation – or afford sufficient legal representation across a whole legal dispute – still deserve access to dispute resolution and other processes to enforce their rights and provide access to justice.

As such, it would be important to approach mandatory legal representation regimes as an opportunity to improve access to justice rather than as a constraint upon it. That is, there is a need for careful monitoring that such regulatory and legislative requirements do not become a barrier to access to justice for people who are unable to access or afford legal representation. A people-centred lens should be applied to considerations for the need for legal representation. In this context, there is scope for the government of Portugal to consider reviewing legislation and regulations concerning legal representation requirements (including those in the following paragraphs) to ensure that they are consistent with a people-centred approach that seeks to ensure that people have access to appropriate and affordable services to meet their particular needs.

In civil cases, legal representation is required for enforcement actions of more than EUR 30 000 or more than EUR 5 000 if the action follows the terms of the declarative action (Government of Portugal, 2013[12]). It is also mandatory for the party to be represented by a lawyer in declarative actions in causes with a value of more than EUR 5 000; in cases where an appeal is always admissible, regardless of the amount; and in appeals and in cases brought before higher courts (Government of Portugal, 2013[12]).

Even where the representation of a lawyer is mandatory, trainee lawyers, solicitors (“solicitadores”), and the parties themselves may make submissions in which no legal issues are raised. On the other hand, in cases where representation is not mandatory and where the parties have not appointed a proxy, the examination of witnesses is carried out by the judge, who is also responsible for adapting the procedure to the specificities of the situation.

Similarly, in administrative and tax courts, it is mandatory to appoint a lawyer (Government of Portugal, 2013[12]). Public entities may be represented in all proceedings by a lawyer, solicitor (“solicitador”), a law graduate or a solicitor graduate with legal support functions, without prejudice to the possibility of representation of the state by the Public Prosecutor's Office (Government of Portugal, 2002[13]) (Government of Portugal, 1999[14]). This is also the case for public entities (Government of Portugal, 2002[13]) (Government of Portugal, 1999[14]).

In criminal cases, the assistance of a lawyer to the defendant is mandatory during the interrogation of an arrested or detained defendant, interrogation by a judicial authority, and the preliminary hearing and court hearings. It is also necessary in any procedural acts other than the formal declaration as defendant whenever the accused person has any visual, hearing or speaking impairment or is illiterate, cannot speak or understand the Portuguese language, is less than 21-years-old, or where the issue of her/his excluded or diminished criminal liability has been raised. Moreover, in case of ordinary or extraordinary appeal, the assistance of a lawyer to the defendant is mandatory when statements are made for future memory, where the trial hearings take place in absence of the defendant, and finally in other cases determined by law.

The court may appoint a lawyer for a defendant at the court or defendant’s request, where the specific circumstances of the case show the need or the convenience for the defendant to be assisted (Government of Portugal, 1987[15]). If the defendant does not have a lawyer or an appointed lawyer, the appointment is mandatory when the person is formally charged (Government of Portugal, 1987[15]).

The position of the victim in a criminal case is different. The victim may only be a witness in the proceedings and represented by a lawyer present at the time of testimony (Government of Portugal, 1987[15]). The victim can also assume the role of a civil victim, claiming compensation for damages. In that case, the victim must necessarily be represented by a lawyer in cases where the value of the claim is of more than EUR 5 000 (Government of Portugal, 1987[15]). Finally, the victim can assume the position of assistant in the process. In that case, the victim would work with the public prosecutor and contribute to investigations, actively participating in the trial (e.g. by submitting evidence) and being able to appeal against the decisions that affect them. In these cases, the victim must necessarily be represented by a lawyer (Government of Portugal, 1987[15]).

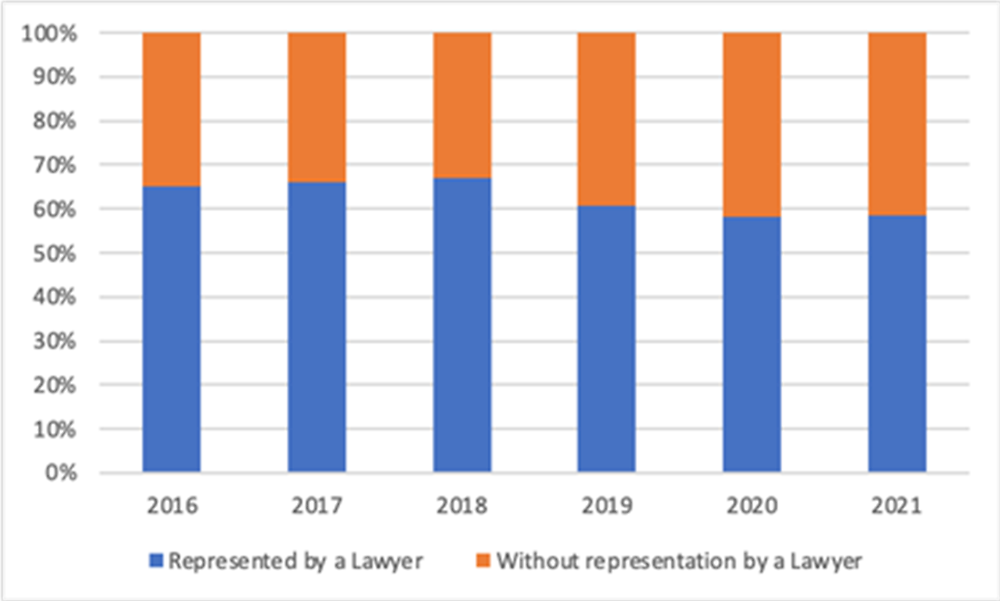

As a rule, parties do not need to be represented by a lawyer in justice of the peace courts. The assistance of a lawyer in these courts is only mandatory when the party is illiterate, has no knowledge of Portuguese, or is considered in an “underprivileged position”. Representation by a lawyer is also mandatory in the case of an appeal (Government of Portugal, 2001[16]). Some 59% of the parties in the cases concluded in justice of the peace courts in 2021 were not represented by lawyers (Conselho dos Julgados de Paz, 2021[17]). Figure 7.1 shows the evolution of the percentage of parties with and without representation by a lawyer in cases completed between 2016 and 2021.

Figure 7.1. Rate of representation by a lawyer in justice of the peace courts (2016 – 2021)

Copy link to Figure 7.1. Rate of representation by a lawyer in justice of the peace courts (2016 – 2021)

Source: Conselho dos Julgados de Paz (2022[5]), XXII Relatório Anual do Conselho dos Julgados de Paz, https://www.conselhodosjulgadosdepaz.com.pt/ficheiros/Relatorios/Relatorio2022.pdf.

In mediation sessions, the parties must participate in person and are free to present themselves alone or accompanied by lawyers, trainee lawyers or solicitors, as well as being assisted by interpreters if necessary (Government of Portugal, 2013[18]) (Government of Portugal, 2007[19]).

Recently, Portugal has seen a discussion about the roles of lawyers and solicitors, focusing on the specific services they provide. This has led to changes in the laws governing these professions, specifically the Statute of the Bar Association. A significant update came with the new legal framework introduced by Law 10/2024 on 19 January 2024. This law, enacted after overcoming a presidential veto, sets new rules for the activities of lawyers and advocates. The president had expressed concerns that allowing non-lawyers to perform these services without proper oversight and training could harm the judicial system and citizen rights (Government of Portugal, 2024[20]).

Despite these changes, the requirement for lawyers in legal cases remains unchanged. However, the new rules now permit certain legal tasks, once exclusive to lawyers and solicitors, to be performed by other legal experts who are not members of their professional associations. Essentially, lawyers still hold exclusive rights to represent clients in court, assist citizens dealing with authorities, and provide defence in criminal proceedings, as required by the Criminal Procedure Code.

The new legislation opens doors for law graduates, notaries, and enforcement agents to offer legal advice. It also allows them and commercial companies to draft contracts if it complements their main business activities. Furthermore, companies focused on debt recovery can now negotiate settlements.

This significant shift in legal practice and service provision needs careful observation to assess its impact on service quality, responsibility, and oversight, emphasising a client-first approach. It offers a chance to evaluate if these legal changes and the broader access to legal services can improve service delivery and expand legal access and information.

7.3.3. The legal profession

Copy link to 7.3.3. The legal professionThe legal profession fulfils an essential role at the heart of justice systems. While many other actors and professionals, including law clerks, paralegals, legal secretaries and others have always been an important part of the system of delivering justice services, lawyers have a unique role and influence over the justice system in most countries. However, over two decades of people-centred legal needs research, including the recent 2023 LNS in Portugal, have brought a more nuanced understanding of how people approach legal problems. In particular, legal problems are widespread across the community, and they are often intertwined with a range of other life problems, not just legal ones. The implications of this, particularly for disadvantaged people, is that they often approach legal problems as only one among several problems that they may face. Moreover, they often do not see it as the most important problem or even as a legal problem. In many occasions, they approach legal problems – and other problems such as health, housing employment – with the assistance of NGOs, community organisations or support agencies from other social service areas. In this context, people often do not go to a lawyer’s office to deal with a legal problem. To reach those most in need, legal services should go to where the people who need them are.

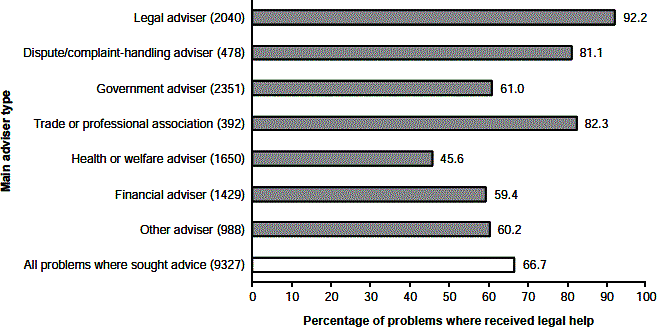

For example, a legal needs survey of almost 21 000 respondents in Australia looked at who provided people with legal help1. Figure 7.2 shows that to get help in understanding and acting to solve their legal problems, people turn to a range of agencies, when they might actually seek assistance from a professional advisor. Importantly, this survey found that when people do seek support from a legal service provider/lawyer (only about 16% of matters), respondents reported higher satisfaction levels than from other service providers (Coumarelos et al., 2012[21]).

Figure 7.2. Legal help from main adviser, by adviser type (Australia, 2012)

Copy link to Figure 7.2. Legal help from main adviser, by adviser type (Australia, 2012)

Source: Coumarelos, C; Macourt, D; People, J; McDonald, HM; Wei, Z; Iriana, I; Ramsey, S, (2012[21]), Legal Australia-Wide Survey: legal need in Australia.

The 2023 LNS also confirmed this perception in Portugal. Some 43% of respondents who said they had experienced a legal problem had sought help to obtain information, advice or representation to resolve the problem. But only 26% sought professional legal advice (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3. Sources of legal help in Portugal

Copy link to Figure 7.3. Sources of legal help in Portugal

Source: 2023 LNS.

Most people who seek legal advice do it from a number of sources. The 2023 LNS found that the organisations people turn to are very diverse. Importantly, findings from the diagnosis phase suggest that the legal profession may be exerting a restrictive influence on how legal advice and assistance could be provided. For example, it was reported that lawyers are not allowed to give legal advice outside of legal offices even if such settings might align with clients' preferences, primarily due to concerns about confidentiality. This limitation has rendered the provision of legal advice and assistance in non-traditional venues such as NGOs, community service spaces, and even within the community where underprivileged groups are more likely to be found, a contentious issue. As a result, organisations employing lawyers for consultation purposes find themselves navigating a regulatory grey area, uncertain of their legal standing.

Portugal is encouraged to reconsider these professional and regulatory barriers to legal service provision in light of insights from recent research into legal and justice needs, including studies conducted within the country. Evidence from the legal needs survey (see Figure 7.3) underscores that individuals seek information, support, and advice from a diverse array of sources, often outside conventional legal offices and institutions. The initiative by the Public Interest Advocacy Centre in Sydney, Australia, illustrates an innovative approach. Through the Homeless Person’s Legal Clinics, it collaborates with pro bono lawyers from the private sector and NGO legal professionals to offer legal counsel at locations readily accessible to the homeless population, such as homeless shelters operated by NGOs, emergency centres for women, refuges, street food services, church halls, and other outreach venues.

The prevailing risk associated with stringent practice guidelines and regulations is the potential deterrent effect on individuals seeking legal advice from qualified practitioners. This could inadvertently prompt individuals to seek guidance from a wider, more accessible, yet potentially unqualified array of services and agencies, leading to varied outcomes in terms of the reliability and soundness of the advice received.

Accordingly, there exists an opportunity for Portugal to assess such restrictive practices from the perspective of service recipients that takes into consideration their preferences for how and where legal advice and assistance should be delivered. This reassessment aims to enhance access to justice and ensure that the provision of justice services is centred around the needs and perspectives of the populace.

Finally, there is scope to rethink incentives for the legal profession to facilitate take-up of certain innovations, such as using the justice of the peace courts and ADR services. For example, a number of stakeholders suggested that new incentives and capacity-building may be needed to encourage lawyers to guide and recommend clients to use many of the justice interventions introduced by the government of Portugal in recent years, such as ADR and justice of the peace courts, rather than taking conventional pathways. Some stakeholders have indicated that lawyers might choose traditional practices over newer ones because of incentives such as familiarity with traditional processes, legal certainty, and established appeal options.

References

[4] APAV (2022), Estatísticas APAV - Relatório Anual 2021 - Associação Portuguesa de Apoio à Vítima, https://apav.pt/apav_v3/images/press/Relatorio_Anual_2021.pdf.

[5] Conselho dos Julgados de Paz (2022), XXII Relatório Anual do Conselho dos Julgados de Paz, https://www.conselhodosjulgadosdepaz.com.pt/ficheiros/Relatorios/Relatorio2022.pdf.

[17] Conselho dos Julgados de Paz (2021), XXI Relatório Anual do Conselho dos Julgados de Paz, https://www.conselhodosjulgadosdepaz.com.pt/ficheiros/Relatorios/Relatorio2021.pdf.

[21] Coumarelos, C. et al. (2012), Legal Australia-Wide Survey: legal need in Australia, Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales, Sydney.

[7] Coumarelos, C. and H. McDonald (2019), Developing a triage framework: linking clients with services at Legal Aid NSW,, Law and Justice Foundation of NSW, Sydney, https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/8153336.

[20] Government of Portugal (2024), Law 10/2024, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/10-2024-837135330.

[3] Government of Portugal (2019), Protocolo entre o Ministério da Justiça e a Procuradoria-Geral da República, https://www.ministeriopublico.pt/sites/default/files/anexos/protocolos/protocolo_mj-pgr.pdf.

[12] Government of Portugal (2013), Civil Procedure Code, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/legislacao-consolidada/lei/2013-34580575.

[18] Government of Portugal (2013), Law no. 29/2013, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/29-2013-260394.

[19] Government of Portugal (2007), Law no 21/2007, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/legislacao-consolidada/lei/2007-63397378.

[13] Government of Portugal (2002), Administrative Courts Procedure Code, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/legislacao-consolidada/lei/2002-34464475.

[16] Government of Portugal (2001), Law no. 78/2001, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/legislacao-consolidada/lei/2001-56735875.

[14] Government of Portugal (1999), Tax Procedure Code, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/legislacao-consolidada/decreto-lei/1999-34577575.

[15] Government of Portugal (1987), Criminal Procedure Code, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/legislacao-consolidada/decreto-lei/1987-34570075.

[9] Municipality of Lisbon (2022), Espaço Júlia acolhe em Lisboa vítimas de violência doméstica, https://www.lisboa.pt/atualidade/noticias/detalhe/espaco-julia-acolhe-em-lisboa-vitimas-de-violencia-domestica.

[2] Neves, A. et al. (2015), Gabinete de Informação e Atendimento à Vítima (GIAV) - Espaço Cidadania e Justiça, https://comum.rcaap.pt/bitstream/10400.26/8786/1/Poster03_IAlmeida_2015.pdf.

[11] OECD (2023), Recommendation on Access to Justice an People-Centred Justice Systems, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0498.

[1] OECD (2021), OECD Framework and Good Practice Principles for People-Centred Justice, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cdc3bde7-en.

[8] OECD (forthcoming), OECD Conceptual Framework for Online Dispute Resolution.

[10] Pleasence, P. (2014), Reshaping legal assistance services: building on the evidence base: a discussion paper, ., Law and Justice Foundation of NSW, Sydney.

[6] Wiens, J. (2019), Formative Evaluation of an Online Access to Justice Triage and Intake System, https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/coph_slce/69/.

Note

Copy link to Note← 1. “Legal help” can be defined as the provision of pre-packaged legal information, advice on legal rights or procedures, help with legal documents, help with court or tribunal preparation, help with formal dispute resolution sessions (e.g. mediation or conciliation), negotiation with the other side, and referral to a lawyer or legal service.