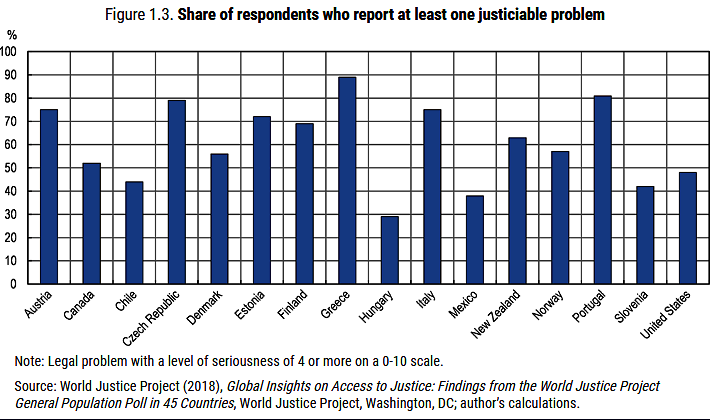

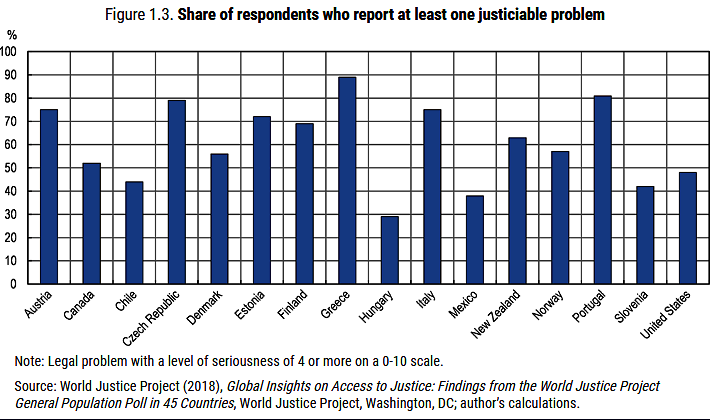

Results also suggest that the share of legal needs addressed is higher in Portugal than in other comparable countries. At 30%, the share of respondents who lack legal capability or awareness on where to obtain information and assistance to solve their legal problem is lower than in most OECD countries. Importantly, one-fourth of respondents who faced a legal problem had received professional assistance, which constitutes one of the highest shares among OECD countries. However, access to professional advice seems to increase rather strongly with the level of income. Finally, 65% of the legal problems reported in the survey had been resolved, of which only 5% had been addressed through the formal judicial system (OECD, 2020[1]).

The main studies that have enabled an approach to justice and legal needs in Portugal have in their wake the traditional theme of the sociology of law and the political sociology of public opinion on law and justice. The most comprehensive surveys, representative of the Portuguese population, were carried out by the Centre for Social Studies in 1993 (Santos et al., 1996[2]) and later in 2001 (Santos et al., 2004[3]).

These studies aimed at understanding citizens’ awareness of the law and the courts, their perception of courts’ performance and functions, their opinion in light of their own or their relatives' experiences and, finally, whether they resort to justice institutions when needed (Santos et al., 1996[2]). These studies sought to identify the triggers for demands to justice in Portugal and to identify interviewees’ experiences as plaintiffs, defendants or victims.

Both surveys defined 10 areas to identify patterns of litigation. These areas were inheritance, domestic violence, neighbourhood, insurance, defective products, tenancy, non-payment of debts, work, environmental quality and corruption. Respondents were asked whether they had any disputes in each area and, if so, which different dispute resolution mechanisms were used and in which order. Results showed a relatively low pattern of litigation in the ten areas defined, although with variations within each area. More relevant are the findings on how people sought to resolve these problems. In the 1993 survey, the most common problems experienced by the sample were (a) neighbours – 21.7% (b) tenancy – 12.2%, (c) debts – 12%, and (d) defective product – 11,8% (Santos et al., 1996[2]).

One of the main purposes of the research carried out in 1993 and 2001 was precisely to find out cases that do not reach the courts but rather are handled by other dispute resolution mechanisms. This includes unofficial or informal (e.g. intervention of a friend or family member, agreement with the other party), official non-judicial or administrative (Consumer Protection Centre, municipality) or cases left without any action. Survey results showed that there is a clear option for unofficial dispute resolution mechanisms (e.g. reaching an agreement amicably).

Surveys results also showed a significant weight of inaction. In some types of conflicts, this was shown the priority form of resolution. This could suggest that the Portuguese society is marked by a deficit of active citizenship, influenced not so much by ignorance of rights, but rather by the lack of motivation to claim them (Santos et al., 1996[2]). Both surveys concluded that only a small fraction of legal problems reaches the courts. It also suggested that, at that time, the Portuguese society was characterised by a significant discrepancy between the effective and potential demand for courts. In 1993, 20.9% of the respondents stated that they had at least one case in court. Within this group, the overwhelming majority (73.6%) had only one (Santos et al., 1996[2]). In 2001, 22.9% of the respondents had at least one case in court and, of these, most stated that they only had one (Santos et al., 1996[2]).

Both surveys also sought to find out the reasons for avoiding judicial dispute resolution mechanisms. Results revealed that a large proportion of respondents would not resort to courts in case their dispute was not resolved. The main common reason was the “inadequacy of the judicial channel” as the issue being considered as not “serious enough” or respondents not willing to “get on bad terms with my family/neighbours/spouse”. The common areas within this answer included marital aggression and defective products. Inaccessibility (i.e. “it was very expensive to go to court; it took a long time”) was particularly relevant for certain types of conflict (e.g. quality of the environment, labour relations, tenancy or insurance). Hostility against courts was low in most cases (Santos et al., 1996[2]).

In 2013, a third survey was launched by the Permanent Observatory for Justice of the Centre for Social Studies, under the project “Women in the Judiciary in Portugal: paths, experiences and representations” (Gomes et al., 2014[4]). Interestingly, results followed the same pattern as of the surveys carried out in 1993 and 2001. Most of the respondents had never had any case in court (15%), and of these, the majority only had one case (Gomes et al., 2017[5]).

In 2002, a survey on “Impressions of Justice in an Urban Environment" aimed to evaluate the experience of the Lisbon population with the justice system, degree of satisfaction and strategies for resorting to dispute resolution mechanisms, awareness of the law, opinion on justice and injustice (Hespanha, 2005[6]). Results indicated that the most common recourses in seeking a solution to a legal problem are the police (38.9%), non-specialised public services (30%) and lawyers (26.2%), while courts are the least used (20.3%) (Hespanha, 2005[6]).

The survey also sought to ascertain the pathways to resolve certain types of issues, including eviction, dismissal, problems related to personal debts, problems with the division of property, the purchase of defective products, problems arising from the guardianship of children, issues arising from theft or robbery. Results showed that mechanisms linked to justice or the application of law appear in first place in the intentions regarding the resolution of conflicts, despite significant differences according to the type of issues (Hespanha, 2005[6]).