This chapter provides an overview of Portugal's efforts to modernise its justice system through a people-centred approach, highlighting initiatives that aim to enhance responsiveness and accessibility. The chapter explores strategic initiatives and justice-related programmes, detailing their objectives to simplify and streamline processes, promote transparency, and improve service delivery within the justice sector. This chapter also covers the broader impact of these reforms on trust in legal institutions and discusses ongoing efforts to align Portugal's justice policies with international best practices for an accessible, equitable and efficient people-centred justice system in Portugal.

Modernisation of the Justice Sector in Portugal

2. Towards people-centred justice in Portugal

Copy link to 2. Towards people-centred justice in PortugalAbstract

2.1. Context

Copy link to 2.1. ContextThe demands on justice systems worldwide and in Portugal have been increasing in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic created new legal needs and issues, and confronted justice systems and governments generally with the need to substantially transform their ways of operating. Yet the COVID-19 pandemic came in the midst of other major challenges for justice systems and governments, which included demands for environmentally responsible governments with associated energy transitions, and the rapid transformation of economies and societies prompted by the digital age.

Perhaps most important have been the recent challenges to democracy and trust in democratic institutions. The OECD Trust Survey sheds light on people’s trust in justice institutions. Data shows that just over half (57%) of people on average trust the courts and legal system (OECD, 2022[1]). The OECD Trust Survey carried out in Portugal revealed that respondents are fairly confident that they can rely on their government to deliver public services and to tackle major intergenerational challenges, such as climate change and future epidemics – all significant determinants of trust in the national government. However, in line with many other OECD countries, there is scope for Portuguese institutions to enhance responsiveness to people’s expectations on participation and representation.

Justice systems and institutions, and people’s ability to access justice and address their legal needs are fundamental to the rule of law and democracy. With the adoption of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16.3 on the rule of law and access to justice, as well as the OECD Recommendation on Access to Justice and People-centred Justice Systems (OECD, 2023[2]), OECD member countries have committed to transforming justice systems to be focused on the legal needs and justice problems of all people, identifying what these needs are and designing reform and services towards meeting those needs, resolving problems and achieving fair outcomes. This is particularly important in the context of declining trust in public institutions, increasing citizen expectations and challenges faced by democracies and the rule of law.

Timely and affordable access to effective and appropriate justice services can significantly impact people’s lives. Increasingly complex, slow or inaccessible justice systems jeopardise the ability of people to enforce their rights, access services they are entitled to, resolve their problems and disputes, and to hold those in power accountable. This can, in turn, undermine democracy and the rule of law. Indeed, when justice systems are inaccessible, serving only the few or contributing to inequality, then frustration, disillusionment and discontent follow, with significant social consequences.

Global legal needs research over the last 25 years has confirmed that disadvantaged groups are particularly vulnerable to legal problems and facing obstacles to their resolution, and this was exacerbated during the pandemic. Pre-pandemic estimates show that less than a half of people experiencing a justice problem were able to access some form of help in Portugal (World Justice Project, 2019[3]). Importantly, the pandemic led not only to more disputes but also significantly affected the operations of the courts and the ability to effectively deliver justice in reasonable time in Portugal, mainly due to the suspension of procedural deadlines, postponement of hearings and social distance requirements. These circumstances require adaptable, responsive, agile justice systems to better meet the changing needs of people and business. Fast and fair resolution of conflicts are a fundamental part of rebuilding the economy.

Importantly, however, the COVID-19 pandemic showed that the justice system can quickly adapt by using digital technologies and data. For example, during confinement measures, most courts in different countries transitioned into online hearings and implemented ODR (online dispute resolution) platforms. Indeed, it became rapidly clear that digital technologies and data hold significant potential to strengthen the responsiveness and accessibility of justice to the needs of businesses and people by reducing costs of justice for individuals and states, increasing efficiency and lowering complexity of processes.

The challenge for all governments and justice systems is to maximise opportunities and benefits while minimising negative possibilities; and to maintain commitments to transparency, democracy and the inclusive rule of law throughout. In Portugal, while improving, some challenges related to justice systems remain, including long disposition times, limited accessibility of justice and uneven experience with the use of digital technologies. In particular, while Portugal has been increasingly introducing digital technologies, the country ranks 15th in the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 20221 in its composite score, a progress compared to previous years. Portugal also ranked 12th and 14th in integration of digital technology and public services (European Commission, 2022[4]).

People-centred justice can offer a strategy for governments to meet users’ needs. Regular programmes of legal need assessment, the evaluation of “what works” and adopting an evidence-based agile approach to the design and delivery of justice policies and services can be an important tool in ensuring ongoing resilience and adaptability to changing circumstances. Adopting a people-centred approach helps empower justice systems to adapt to changing circumstances and demands of people, contributing to greater trust in justice institutions.

2.2. Overview of Portugal’s strategic policy and initiatives

Copy link to 2.2. Overview of Portugal’s strategic policy and initiativesPortugal has recognised the importance of responsive and accessible justice. As highlighted in the OECD report “Justice Transformation in Portugal: Building on successes and challenges”, the country has been taking active steps towards a more accessible, efficient and responsive justice system that is sensitive to the needs of people and businesses. The report highlights the growing alignment between Portugal’s improvement efforts and the broader trends in justice modernisation across OECD countries.

In particular, Portugal has been developing a range of strategic initiatives to drive justice sector transformation. In addition to its broader government and justice agenda, the transformation of the justice sector in Portugal is based on the Simplex programme, Justiça + Próxima and, more recently, the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), the Justice + programme and the GovTech Strategy. These main guiding and policy strategies share a vision of a more collaborative and people-centred approach in policy making and service delivery. Building on the principles laid out in the Strategy for Innovation and Modernisation of the State and the Public Administration 2020-2023 (Government of Portugal, 2020[5]), an outline of these most recent programmes provides an example of efforts to simplify and streamline service delivery and to foster innovation and digital technologies as enablers of transformation in the justice sector in Portugal.

In April 2022, the XXIII Constitutional Government presented to the Portuguese parliament the government programme for the 2022-2026 cycle. In the area of justice, Portugal committed to making justice closer, more efficient and transparent, and creating legislative, material and technical conditions for improving quality of justice (Government of Portugal, 2022[6]). Among the various commitments, the programme emphasised two fundamental areas: the efficiency of the justice system and transparency in the administration of justice. The lengthy procedures and the complexity of the procedural and operating models were two factors identified as obstacles to the full realisation of rights and as barriers to economic welfare. The measures are largely based on the adoption of digital technologies and data to optimise procedures, making use of the investments provided in the RRP to modernise, digitalise and interconnect justice services with the broader public sector.

Launched in 2016, the modernisation and digital transformation plan Justiça + Próxima aimed to leverage digital technologies and data to transform justice services in Portugal. In 2020, a second edition of Justiça + Próxima was launched for the period 2020–2023 (see Box 2.1). The new plan includes 140 measures committed to disseminating a culture of innovation across the justice sector and addressing some of the most pressing challenges in the justice sector, using digital technologies as key enablers.

Box 2.1. Portugal: Justiça + Próxima

Copy link to Box 2.1. Portugal: Justiça + PróximaJustiça + Próxima is a major initiative in Portugal focused on modernising the justice system. It aims to make justice more accessible, efficient, and people-centred. The programme is divided into phases, and it is Portugal’s significant effort to improve the delivery of services and people’s experience with justice system.

The plan is based on four pillars:

1. Efficiency: Optimising the management of justice; promoting the simplification and dematerialisation of processes; assessing, changing, or eliminating outdated methodologies, procedures and unnecessary acts, with a focus on users.

2. Innovation: Developing new approaches to support the transformation of justice, leveraged by digital technologies, encouraging collaboration between civil servants, universities, researchers, companies and entrepreneurs.

3. Humanisation: Improving the welcoming aspect in public spaces and conditioned spaces of justice. This includes training and upskilling civil servants in direct contact with inmates, and valuing social reintegration (e.g. through training and employability) and prevention of criminal recidivism.

4. Proximity: Creating services that are simpler and closer to people and businesses. This includes eliminating formalities and procedures, with more integration and through different channels.

Source: Government of Portugal (2020[7]), Justiça + Próxima Plan 2020-2023, https://justicamaisproxima.justica.gov.pt/sobre-o-plano/.

In 2019, Portugal took steps to reform its administrative and fiscal litigation processes, aiming to tackle delays and make the system more efficient (Gomes et al., 2017[8]). One of the measures proposed was to encourage the use of models and forms for procedural documents to be presented in court, fostering coherence as a mechanism to render the litigation process more effective. In 2020, as one of the projects inserted in the Justiça + Próxima programme, such forms were made available for lawyers to fill out, thus giving substance to the legislative innovation of 2019. Another example is the dematerialisation of communications between courts and other external entities (e.g. banks, insurance companies, the Bank of Portugal, the Driver's Individual Register), as well as in developing solutions that enable interoperability between the court system and other information systems (e.g. public databases within the scope of civil enforcement proceedings, inventory platform of the Association of Notaries).

Launched in 2023, the Justiça + programme aims to revamp the justice system, spurred by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR) and in continuation of the Justiça + Próxima programme. Its primary goal is to enhance trust in the justice system by making it more responsive, transparent, and aligned with the present needs of individuals and businesses. To accomplish this overarching goal, the programme structures 53 proposed measures for transforming the justice sector into 10 key responses that prioritise the needs of both people and businesses (see Box 2.2 below, and Box 8.5 in Chapter 8).

Box 2.2. Portugal: Justiça + programme and approaches for justice centred on people and business’ needs

Copy link to Box 2.2. Portugal: Justiça + programme and approaches for justice centred on people and business’ needsThe Justiça + programme in Portugal is a comprehensive effort aimed at modernising and improving the country's justice system. It focuses on making justice more accessible, efficient, and tailored to meet the needs of citizens and businesses. The programme encompasses various initiatives and reforms aimed at streamlining procedures, reducing delays, and enhancing the overall effectiveness of the justice system.

The programme’s 10 key responses are:

1. Put justice at the service of people and the economy

2. Reform administrative justice

3. Fight corruption and new forms of crime with determination

4. Innovate in justice

5. Strengthen the resilience of information systems

6. Manage justice buildings and equipment more efficiently

7. Manage, strengthen and dignify the human resources of justice

8. Train human resources

9. Protect the most vulnerable in the care of justice

10. Justice for Europe

The programme’s commitments are part of a continued effort since 2015, with Justiça + Próxima. Since the launch of Justiça + in 2022, 172 measures have been implemented to modernise, simplify and digitalise justice services.

Source: Government of Portugal (2023[9]), Justiça +, https://mais.justica.gov.pt/#continuaravancar.

A significant part of the investment is directed to the "economic justice and business environment" component (C18), which foresees an investment of EUR 233 000 000 for the period 2022 to 2026 (Diário da República, 2022[10]). These investments aim to modernise processes and procedures and to reduce lengthy delays in case finalisation throughout the justice system, with special focus on Administrative and Tax Courts (TAF) and on the areas of insolvency and debt from commercial and enforcement courts (Government of Portugal, 2021[11]). In this context, and with a particular focus on administrative and fiscal justice, the Justice + programme provides for a series of specific measures: improving the management of the judiciary; optimising the performance of the higher courts by introducing technical assistance for judges of the Administrative and Tax Courts; simplifying and speeding up procedures; promoting digital transformation; strengthening human resources; creating a new court of appeal.

The investments also addressed structuring digital platforms for Administrative and Tax Courts, with Magistratus and Public Prosecutor's Codex, and developing a single interface for lawyers, solicitors and representatives of public entities. Other examples are the modernisation of the court registries and legal aid information system, and the dematerialisation of communications with various external entities (Government of Portugal, 2021[11]).

Component 8 of the performance review report (PRR), which concerns forests, also provides for investment in up-to-date and detailed knowledge of the territory, with implications for projects developed in the justice sector. A sum of EUR 55 million has therefore been earmarked to continue efforts to operationalise the BUPi, a single platform for dealing with citizens and businesses. and their relations with the public administration, and the simplified land registry system, based on the three pillars of promoting the registration of property, the rapid acquisition of data on the geometry of buildings and the harmonisation of tax information (Government of Portugal, 2021[11]).

Despite strong commitment and significant progress, there remains a range of areas for further progress in the justice sector. For example, while Portugal has made significant advancements in relation to the disposition time of court proceedings, dropping from 417 days in 2010 to 253 days in 2021 in civil and commercial courts of first instance (European Commission, 2023[12]), lack of efficiency seems to persist among the main challenges for access to justice. In addition, while Portugal has implemented significant initiatives in the area of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, including mediation, arbitration and the introduction of justices of the peace across the country, there is scope for simplifying and rationalising processes associated with arbitration services, as well as an untapped opportunity to further expand the justice of the peace courts and strengthen their use across the country. Importantly, comprehending ADR services as an integral part of the continuum of justice services is an important step in achieving their more coherent integration into the funding and co-ordination of the overall justice system.

2.3. A people-centred approach to modernisation

Copy link to 2.3. A people-centred approach to modernisation2.3.1. People-centred justice

Copy link to 2.3.1. People-centred justiceA dominant feature of Portugal’s recent justice system reform has been “bringing justice closer to the people” (Government of Justice, 2023[13]). People-centred justice provides the best available means to ensure effective, affordable and sustainable access to justice. Further, because people-centred justice ensures that the justice system is more focused on the needs of all people in the jurisdiction, it therefore increases the likelihood of improving the levels of trust between people and government.

People-centred justice systems aim to put people and their legal and justice needs at the centre of the justice system, and thus at the centre of justice-system reforms, and design and delivery of policies and services. This means that people-centred justice systems focus – as a priority – on:

Understanding what exactly people’s legal and justice needs and experiences are;

Designing and delivering policies and services that effectively and affordably meet those needs;

Monitoring, evaluating and collecting people-centred data to provide the necessary evidence-based ecosystem to support an evidence-based people-centred approach (see Planning for the delivery of services).

Importantly, these steps will likely be fully implemented when there is commitment at the highest levels to a people-centred approach to justice systems and institutions.

2.3.2. People-centred purpose at all levels of the justice system

Copy link to 2.3.2. People-centred purpose at all levels of the justice systemStrong leadership helps ensure effectiveness, consistency and conformity of institutions regarding their respective mandates, responsibilities, overarching policies and guidelines. Fact-finding interviews revealed that strong leadership is widely reflected across institutions of the justice sector in Portugal. Stakeholders showed strong commitment of justice institutions to achieving their existing, given missions and working within their areas of responsibility and mandates. This is commendable and emphasises the strong role and importance of leadership within the broader justice system in Portugal.

Furthermore, with the aim of strengthening leadership and the alignment of strategies between the different areas of justice, between October 2022 and April 2023, LAB Justiça carried out an intensive six-month training programme tailored to the challenges faced by the bodies and entities of justice, bringing together around 100 leaders and project managers from 18 bodies and entities of justice, including the Supreme Council of the Judiciary, the Supreme Council of Administrative and Tax Courts, the Public Prosecutor's Office and the Council of Justices of the Peace. In December 2023, a protocol was signed to hold the second edition for another 50 employees of the justice sector, as well as a 60-hour training programme for the participants of the first edition, aiming to deepen some topics of the previous training (see Box 5.2 in Chapter 5).

Despite strong leadership at the highest level of the justice sector, there appears to be scope to further embrace a people-centred approach to justice. Fact-finding interviews revealed that there is room to reflect on the extent to which existing mandates and mission statements of individual institutions and programmes, and within Ministry of Justice functions, clearly and unambiguously focus attention for policy and investment on the needs of the people first.

2.3.3. A unique opportunity

Copy link to 2.3.3. A unique opportunityThe current justice modernisation programme in Portugal has a potential to transform people’s experience with the justice services and to contribute to the increase in trust in the justice system. This is a unique opportunity for the Portuguese government to build on the current reforms and to steer future efforts towards a people-centred approach.

Looking ahead, Portugal may consider using the results of its legal needs survey (LNS), along with a potentially more comprehensive LNS in the future. Additionally, Portugal could leverage the results of more comprehensive satisfaction surveys and assessments across the entire justice system. These results could serve as the starting point in shaping the next phases of the Justiça + programme, among other initiatives, all while adopting a forward-looking strategic approach.

Furthermore, there is an opportunity to articulate a clear, people-centred purpose at the highest level of the justice system. This overarching approach could be disseminated throughout the whole justice sector and reflected in updated people-centred mandates across all justice institutions. In this context, it could be beneficial to review existing mandates and competences to clearly reflect a people-centred approach.

2.4. Planning for the delivery of services

Copy link to 2.4. Planning for the delivery of servicesCountries aiming to shift their justice systems toward a more people-centred approach do not start with a blank slate. On the contrary, justice systems like in Portugal have undergone various evolutions over centuries. The current efforts present an opportunity to understand the needs of the people to plan and deliver people-centred legal and justice services in Portugal.

2.4.1. Planning and mapping people-centred services

Copy link to 2.4.1. Planning and mapping people-centred servicesCountries rarely have the resources to deliver justice services at the desired quality and comprehensiveness. Given this reality, legal services need to be planned in such a way that effectively and efficiently address legal needs where and when they arise.

A people-centred justice system offers timely, appropriate, affordable and sustainable legal and related services. These services aim to help all people address their legal problems and needs, and should be available to ensure that all members of the community can participate effectively in society and not be left behind. Importantly, appropriate and timely services match the specific needs of individuals in their particular situations, considering factors like disabilities, low income, and limited legal understanding. Affordable and sustainable services are reasonably priced for both individuals and the government, and at a sustainable cost over time.

Services need to be available and used. It is not enough that services are theoretically available. If they are not used by some/many, this may indicate that they are effectively inaccessible for some. To achieve this objective, it is important to assess: (a) what the legal needs of the community are, (b) where the legal needs are and (c) what strategies work to meet each different legal need in the different circumstances, to (d) plan and deliver the services tailored and targeted according to this knowledge, and finally (e) whether the services are actually reaching those intended and whether they are achieving the final outcomes.

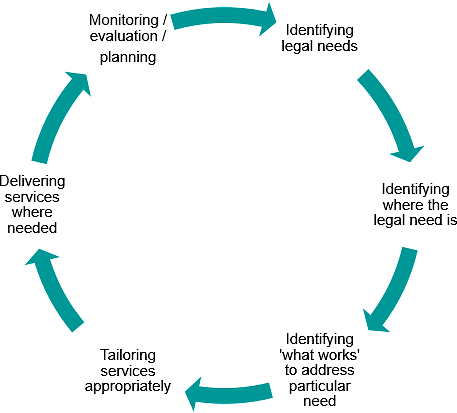

Planning legal and justice services can be approached in a logical sequence described in Box 2.3. The assessment of the range of legal and justice services provided in the following sections utilises the themes of this planning cycle and of the OECD Framework and Good Practice Principles for People-Centred Justice.

Box 2.3. Planning cycle for legal services

Copy link to Box 2.3. Planning cycle for legal servicesA comprehensive planning model portrays the planning legal services sequence as a cycle, as shown by the figure below:

1. Identify legal needs of the community from their perspective.

Relying on the small proportion of matters that reach the formal justice system does not yield a representative picture of the needs of the community.

Methods are necessary to understand the needs of the entire community, encompassing the majority who do not engage with the justice system, and to reach out to the most disadvantaged groups.

2. Identify where the need is: geographically and in relation to particular groups.

Utilise sound legal needs data with official census (or equivalent) data to locate population groups.

3. Identify what strategies and interventions work most effectively and efficiently to address particular needs for particular groups in particular circumstances.

4. Create, develop, tailor and/or improve to deliver effective and sustainable services based on the available evidence.

5. Target and deliver those services where needed (mapping) and to whom.

Matching service delivery data with legal and justice needs data.

Countries wishing to identify gaps in service delivery and monitor the delivery of relevant services to address particular needs may consider mapping service delivery data against legal/justice needs data.

6. Monitoring and evaluation.

Are the services available where and when they are needed?

Are the right people being reached with the right services in a timely fashion, and are they using the services? This comprises assessing available approaches to monitoring service delivery data against relevant needs variables.

Are services achieving expected outcomes?

A suitable data ecosystem is needed to give effect to the planning cycle above and support people-centred and efficient justice service delivery. To develop such a data ecosystem, countries need to be working towards a coherent data strategy and data ecosystem across the agencies and elements of the justice system. This will ideally, over time, involve moving towards common systems of definition, terminology, data collection and retention, and data management. There will also need to be a common, supported approach to mapping the justice data as the model describes.

Source: Mulherin (2018[14]), Planning and delivery of legal assistance services, OECD Global Roundtable on Equal Access to Justice.

2.5. Overview of the project

Copy link to 2.5. Overview of the projectPortugal has requested support from the European Commission under Regulation (EU) 2021/240 in establishing a Technical Support Instrument ("TSI Regulation") with the purpose of strengthening responsiveness and access to justice for all. Following the assessment, the European Commission has decided to provide technical support to Portugal, together with the OECD.

The aim of the project is to support the implementation of the modernisation agenda of the justice sector in Portugal, with a particular focus on a people-centred justice approach. The proposed project also aims to provide a strategic, evidence-based stock-taking of the direction the country is taking in advancing its justice and legal assistance reforms. This includes support of inclusive recovery, and effective monitoring and implementing of SDG 16.3 on promoting the rule of law and ensuring equal access to justice for all. To this purpose, the project has focused on the following areas:

1. Legal and justice needs of people and their pathways to justice;

2. Skills and competencies for modern and people-centred justice sector;

3. Availability, quality and use of data, and statistical information systems in the justice sector;

4. Responsiveness of justice service delivery along the continuum of services within and without the court system;

5. Use of digital technologies and data for a people-centred justice system.

During the inception phase, the OECD gathered pertinent information and conducted in-depth review of relevant documents and legislation to produce an inception report. This was followed by a diagnosis phase, with findings contained in this report. The recommendations of this diagnostic report will serve as a basis for a roadmap to provide a strategic and actionable framework for strengthening equal access to justice for all people. The roadmap will take into account accessibility and responsiveness of the justice sector through different channels, with a particular focus on legal and justice needs and improving the design and delivery of justice services. The roadmap is also intended to strengthen the development and use of digital technologies and data in justice.

It is important to note that the incorporation of the people-centred justice approach into the design and delivery of justice systems, and into the design and delivery of specific legal services, is relatively new. It is praiseworthy that Portugal is striving to execute reforms centred on people's needs throughout the country in a sustainable and cost-effective manner. These efforts align with the OECD Framework and Good Practice Principles for People-Centred Justice (OECD, 2021[15]) and also resonate with the OECD Recommendation on Access to Justice and People-Centred Justice Systems (OECD, 2023[2]).

2.6. Methodology

Copy link to 2.6. MethodologyThe study was based on several main methodological components:

1. Government questionnaire

The OECD designed a questionnaire to help identify key aspects of the state of play of the justice system in Portugal, its degree of people-centredness, as well as the application of digital technologies and data in the justice sector. The questionnaire was directed to the Ministry of Justice which then co-ordinated with other relevant justice institutions to complete it. The Ministry of Justice provided the response to the questionnaire to the OECD in November 2022. Data collected to date has been used to inform the analysis, findings and key recommendations in the diagnostic report.

2. Fact-finding meetings

The OECD conducted a series of fact-finding meetings, both in person and online, between July 2022 and April 2024.

In the first in-person mission in July 2022, the OECD met the advisory group and high-level stakeholders of the justice sector in Portugal. This was an important opportunity to connect with the new leadership of the project and ensure alignment of the scope and activities with the new policy priorities for the justice sector in Portugal. Separate meetings were also conducted across a range of justice institutions and with a variety of key justice stakeholders in order to complement the desk research, surveys and data analysis conducted in this project.

A set of fact-finding interviews were conducted as part of a second in-person mission in October 2022. The interviews aimed to feed into the service delivery a mapping exercise, identifying locations of existing justice services and exploring pathways that justice users follow to address their legal and justice needs.

A second set of fact-finding interviews (in-person and remotely) took place in March 2023. They aimed at collecting additional insights on the availability, exchange, usage and governance of data in the justice sector, and close gaps from previous fact-finding meetings on service mapping.

During the missions and fact-finding interviews, visits were conducted to a number of courts, alternative dispute resolution institutions, government departments, professional bodies, non-governmental organisations and important pilot projects in the area of domestic violence. The limited time available for the exploratory interviews naturally led to the selection of some organisations. Care was taken to ensure not only that the different structures in the justice sector were covered, but also that there was geographical diversity, and that institutions of different sizes and type of support were considered.

Although the main focus of the project was on civil issues, fact-finding interviews with organisations and pilot projects working in the field of domestic violence allowed the findings to have greater depth and scope. The justice system’s responses to people's individual legal problems are not, or should not be, delivered in isolation, confining them into legal categories that do not reflect the everyday life experience of people and/or are difficult for people to understand (e.g. civil/criminal). Moreover, this is not a people-centred approach. Furthermore, some of the most important examples of collaboration between community, social services and legal responses are actually found in the area of domestic violence. It has been recognised that the issue of domestic and family violence cannot be dealt with in an efficient way if it is not integrated with other services. Portugal is no exception and has developed a number of initiatives aimed at this integrated response (for example, the victim support offices operating within the public prosecution service).

A number of in-person meetings occurred in major cities in Portugal as part of the diagnosis phase of the project. Organisations consulted following in-person fact-finding meetings provided relevant data and follow-up information. To fill in some gaps, additional interviews with stakeholders were also conducted at later stages of the diagnosis phase. Fact-finding meetings provided an essential grounding to the diagnostic report. Important insights and lessons gathered aligned with findings from the legal needs survey. This confirms the significance of fact-based interviews and qualitative data.

3. Legal needs survey

As part of the project, the OECD conducted a legal needs survey in Portugal, with a view to provide a representative understanding of legal and justice needs from people’s and businesses’ perspectives. Although the 2023 survey conducted in Portugal was limited in scope, the survey was adapted to the particular circumstances of Portugal and followed the underlying principles developed for a comprehensive legal needs survey model published in the 2019 Open Society Foundations (OSJI)-OECD report. The adapted legal needs survey serves as a basis of an in-depth analysis on challenges and opportunities to strengthen access to justice in Portugal for people and businesses, while contributing to justice modernisation initiatives. It also provides a basis to report on SDG indicator 16.3.3 on access to justice.

The 2023 Portuguese LNS had 1 500 respondents, with a sample stratified randomly by year of birth, gender, education level and region (Portugal mainland NUTS 2 – Regional Co-ordination Commissions and Autonomous Regions), following the 2022 population estimates of the Portuguese National Statistics Institute (INE) (INE, 2022[16]). The data was collected through computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). Detailed methodological information about the legal needs survey can be found in Annex F. The 2022 Portugal legal needs survey.

4. Service delivery mapping

Service-mapping is an important step in gaining an evidence-based understanding of the state of play in the delivery of justice services to those in need. Depending on the data collected and available, service delivery mapping can provide essential answers for justice systems and legal service planning. At the most basic level, service-mapping can help locate justice system service delivery organisations in geographical relationship to areas of identified legal need, priorities and vulnerable groups. At a more complex level, by mapping the delivery of legal services at individual, unit record level, service-mapping can help identify which services are actually available to and are used by which people. Likewise, it can help identify which people and legal needs are proportionally unmet. Finally, service-mapping can also provide insight into the pathways people follow when confronting legal problems.

Combined with sound legal and justice needs data, service delivery mapping is an important and powerful tool in assisting governments and service providers to target and deliver services most efficiently and effectively. The methodology employed in this project has been driven by the initial requirement to determine what data is collected and available, and what mapping of services and of priority groups has already been conducted.

5. Skills and competency assessment of justice civil servants

The OECD, in co-operation with the Portuguese government, designed a skills survey to help map and assess skills and competencies to promote people-centricity and responsibilities among justice stakeholders in Portugal. The online survey2 was disseminated to justice sector officials and public service providers and assessed respondents’ perception of their own skills, of management support, and organisational processes in place within their department or ministry. Five competency areas were surveyed: vision and culture; governance; services; planning and monitoring; people empowerment. By assessing this large range of competencies, the survey provides a substantial mapping of skills related to people-centricity, the capability to be operational in a digital environment, and to collect, use and process justice data.

While questions on key competency areas were asked of all respondent’s, targeted skillsets were explored through a branched survey based on respondent’s functions. For example, only ICT professionals were asked certain questions about digital and data skills. The rationale for these foci – on competencies and targets of competencies – stems from a people-centred approach to justice system. Skills needed in a fully-fledged people-centred system relate to all four dimensions of the people-centred framework. Moreover, individuals’ competencies interplay with managerial support and organisational processes.

The survey employs a self-measuring methodology on a 1-to-4 scale (and the possibility not to answer), with responses serving as indicators of self-perceptions, representations, mindsets, and motivations. While the survey results are not statistically representative of Portugal’s justice stakeholders, the responses from 948 people provide useful insights into respondents’ perceptions of their skills and opportunities to develop them. Combined with objective evidence concerning the functional performances of the system, they provide a comprehensive understanding of the system and a consequent set of recommendations to advance alongside the path opened with Justiça + and more generally with the digitalisation process.

References

[10] Diário da República (2022), Lei n.º 24-C/2022, de 30 de dezembro – Law on Major Planning Options, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/24-c-2022-205557191.

[12] European Commission (2023), The 2023 EU Justice Scoreboard, https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/scoreboard_factsheet-quantitative-v4.pdf.

[4] European Commission (2022), Digital Economy and Society Index 2022, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2022.

[8] Gomes, C. et al. (2017), Justiça e eficiência: O caso dos Tribunais Administrativos e Fiscais, https://estudogeral.uc.pt/handle/10316/87266.

[13] Government of Justice (2023), Justiça+, https://mais.justica.gov.pt/.

[9] Government of Portugal (2023), Justiça +, https://mais.justica.gov.pt/#continuaravancar.

[6] Government of Portugal (2022), Programa do XXIII Governo Constitucional 2022-2026, https://www.portugal.gov.pt/gc23/programa-do-governo-xviii/programa-do-governo-xviii-pdf.aspx.

[11] Government of Portugal (2021), Plano de Recuperação e Resiliência, https://recuperarportugal.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/PRR.pdf.

[7] Government of Portugal (2020), Justiça + Próxima Plan 2020-2023, https://justicamaisproxima.justica.gov.pt/sobre-o-plano/.

[5] Government of Portugal (2020), Resolution of the Council of Ministers 55/2020, https://data.dre.pt/eli/resolconsmin/55/2020/07/31/p/dre/pt/html.

[16] INE (2022), Demographic Statistics, https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=ine_tema&xpid=INE&tema_cod=1115.

[14] Mulherin, G. (2018), Planning and Delivery of legal assistance services.

[2] OECD (2023), Recommendation on Access to Justice an People-Centred Justice Systems, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0498.

[1] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[15] OECD (2021), OECD Framework and Good Practice Principles for People-Centred Justice, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cdc3bde7-en.

[3] World Justice Project (2019), Global Insights on Access to Justice 2019, https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data/global-insights-access-justice-2019#:~:text=Global%20Insights%20on%20Access%20to%20Justice%202019%20is%20the%20first,100%2C000%20people%20in%20101%20countries (accessed on 21 July 2023).

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. From 2014 to 2022, the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) summarised indicators on digital performance and tracked the progress of EU countries.

← 2. The survey was deployed in Portuguese as Capacitação para uma Justiça Centrada nas Pessoas em Portugal Avaliação das aptidões e competências dos profissionais da justiça em Portugal – INQUÉRITO between 21 June and 17 September 2023.