This chapter examines trends in investment and investment policies in Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) through a sustainability lens and provides recommendations on how to attract more sustainable investment to the country. Lao PDR experienced an impressive increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows between 2006 and 2017, which has been one of the main drivers of economic growth. However, the country would benefit from FDI that generates more positive spillovers to the local economy and is more conscious of the environment and local communities. Attracting more sustainable investment – which advances environmental and social goals – first and foremost requires improving the overall enabling environment for investment in the country. It would also be important for Lao PDR to integrate environmental and social considerations into investment policies and strengthen the implementation of social and environmental safeguards for investment projects.

Multi-dimensional Review of Lao PDR

5. Fostering sustainable investment in Lao PDR

Abstract

Introduction and strategic priorities for fostering more sustainable investment in Lao PDR

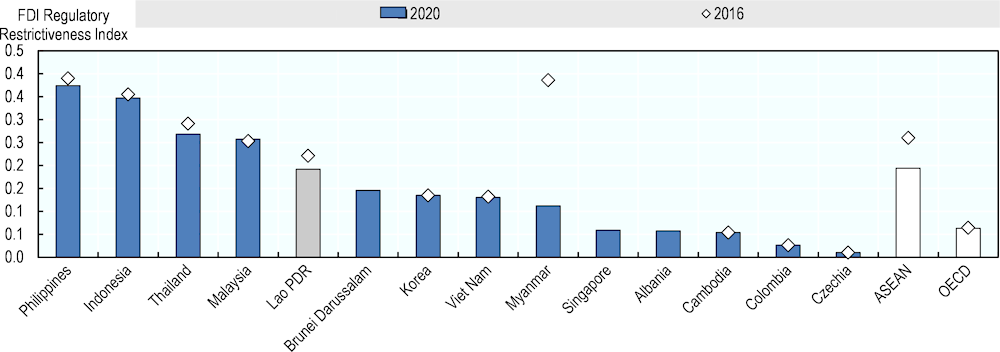

Lao PDR experienced an impressive increase in FDI inflows between 2006 and 2017, from USD 187.4 million (United States dollars) to USD 1.69 billion. This strong growth in FDI can be attributed to the government’s Turning Land into Capital (TLIC) (nayobay han din pen theun) policy, which facilitated large concession investment projects (World Bank, 2006[1]) in hydropower (64% of investment in Lao PDR between 2017 and 2021), mining (15% of investment) and agriculture (6% of investment). More recently, FDI inflows into Lao PDR decreased in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020, but remain significant. As a result of the impressive growth in FDI inflows in Lao PDR, the country is performing well in terms of FDI as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) compared with other member states in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region and elsewhere in the world. Lao PDR’s FDI stock amounts to 80% of its GDP, which is 20 percentage points higher than in Thailand and 30 percentage points higher than in Viet Nam. FDI inflows (as a percentage of GDP) to Lao PDR were three times as high as those in Thailand, almost twice as high as the average among the ASEAN member states and above those in Viet Nam between 2020 and 2022. The People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) is the main country of origin of FDI in Lao PDR: it accounted for 66% of FDI inflows and for 63% of Lao PDR’s FDI stock in 2021 (IMF, 2023[2]).

FDI has been one of the main drivers of economic growth in Lao PDR. Between 2006 and 2017, when FDI inflows to Lao PDR increased dramatically, GDP growth averaged 7.7% annually. This compares with only 3.5% GDP growth in Thailand, 5.4% in ASEAN member states and 6.3% in Viet Nam. Among ASEAN member states, only Myanmar experienced higher average GDP growth during this period (8.9%) than Lao PDR (World Bank, 2024[3]). FDI in Lao PDR contributed to economic growth mainly through capital accumulation and the exploitation and export of Lao PDR’s natural resources (OECD, 2017[4]; CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]).

However, Lao PDR would benefit from FDI that generates more positive spillovers to the local economy and is more conscious of the environment and local communities. Natural resource sectors such as mining and hydropower (which receive the bulk of FDI in Lao PDR) are capital intensive, and activities are often conducted in isolation and typically create few jobs and business linkages with domestic companies. At the same time, these sectors are highly susceptible to creating environmental and social risks if environmental safeguards are not respected. In Lao PDR, large-scale hydropower dams have been associated with negative effects on the environment and local communities. These effects relate to water quality and sediment flows, hydrology and water levels, aquatic ecosystems, and food security (Yong, 2022[6]; OECD, 2017[4]; Intralawan et al., 2018[7]). Additionally, as a result of their effect on the scenery and natural sites, power plants and mining developments can also discourage tourism. Agriculture, on the other hand, has been linked to deforestation, soil pollution and land degradation (Sylvester, 2018[8]; Village Focus International/National University of Laos, 2019[9]; CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]). Finally, it would be critical to ensure that Lao PDR reaps a sufficiently large share of the benefits which accrue from hydropower development (Yong, 2023[10]).

Policy priorities for harnessing FDI in order to support Lao PDR’s sustainable development

Improving the enabling environment for investment and integrating environmental and social considerations into investment policies could allow Lao PDR to attract more sustainable investment that advances environmental and social goals. This includes investments that create a significant number of good-quality jobs, generate local linkages and spillovers such as technology and skills transfers, contribute to skills development, and adhere to strict environmental and social standards (OECD, 2022[11]). By reducing the cost and complexity of investing in Lao PDR, a better enabling environment for investment could allow more investors to make the additional effort and invest the additional resources required in order to limit the negative social and environmental impacts of their investment projects. Improving the enabling environment first and foremost requires a whole-of-government approach to investment, as well as improving access to skilled labour and land, upgrading transportation infrastructure, and reducing opportunities for corruption. It also involves strengthening the regulatory framework. In addition, it would be important to strengthen the implementation of social and environmental safeguards for investment projects and to more actively advance environmental and social goals through investment promotion policies, tax incentives and a better policy framework for responsible business conduct (RBC).

Reforms in several policy areas would be particularly important and should be prioritised. Key priorities for policy reforms include the following:

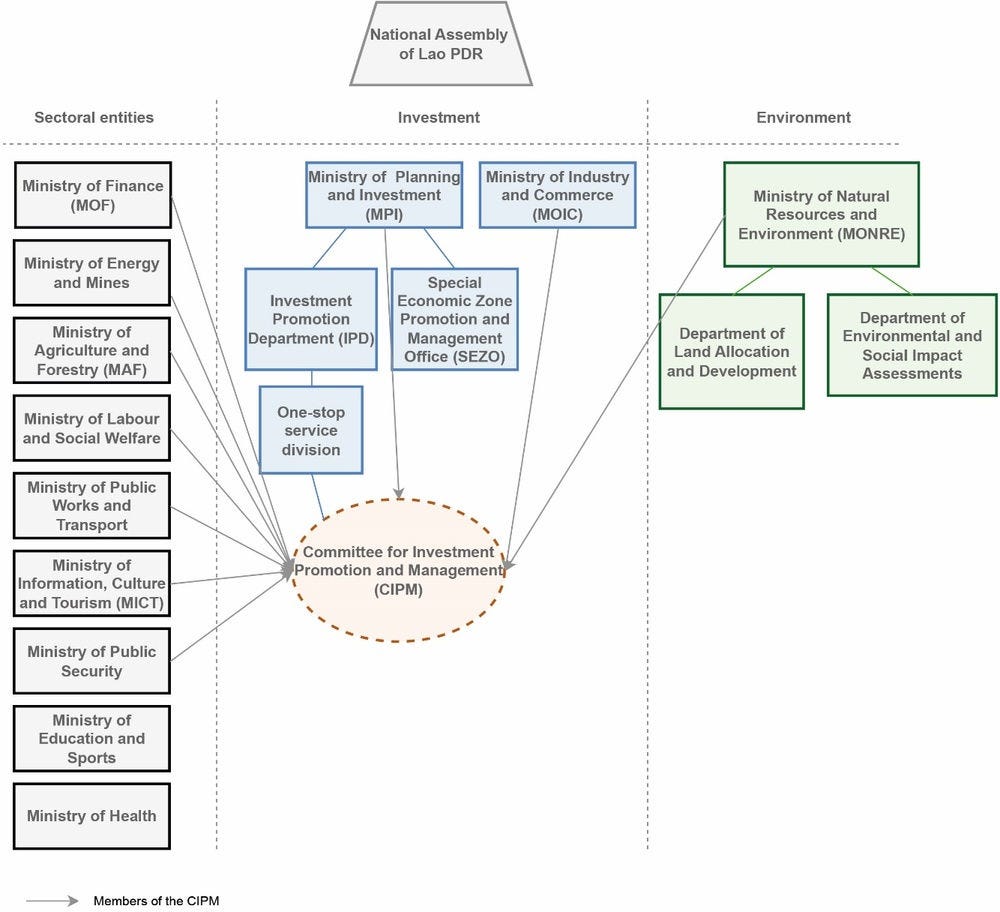

Improve co‑ordination between different government entities and between the public and private sectors. Countries that have been successful in attracting investment have mastered a whole-of-government approach to investment promotion and facilitation (OECD, 2015[12]). In Lao PDR, there is scope for better inter-institutional co‑ordination and alignment of strategic objectives and priorities among the different government entities involved in the design and implementation of investment policies. This could be achieved through the establishment of more formal channels for co‑ordination between the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI), the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (MOIC), the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE), and sectoral ministries. One possibility would be establishing an advisory board to the Investment Promotion Department (IPD) of the MPI that includes representatives both from these government entities and from the private sector. Similarly, Lao PDR would benefit from better communication between the public and private sectors. An effective and institutionalised public-private dialogue process at a high level could allow for more easily solving investors’ grievances and for better prioritising the reforms required in order to facilitate doing business in Lao PDR.

Improve the availability of skilled labour in Lao PDR through in-house training in private enterprises and the provision of better information on those skills that are in demand in the labour market. Different policies (such as tax incentives for training, for example) could encourage more in-house training by private enterprises. In addition, improved co‑ordination between the private sector, the government and educational institutions could help better align Lao PDR’s educational offerings with those skills that are in demand in the labour market. This process could be facilitated through the regular engagement of relevant stakeholders in a dedicated council or committee. Finally, an effective skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) system could identify the types of occupations, qualifications and fields of study that are in demand in the labour market in Lao PDR, or that may become so in the future (OECD, 2019[13]).

Improve institutional capacity and inter-institutional co‑ordination in land administration and management, and accelerate the implementation of the 2019 Land Law. A significant share of land in Lao PDR is not formally registered, and the responsibility for land use management is divided among a large number of institutions (National Assembly, 2019[14]), which lack sufficient co‑ordination (MRLG/LIWG, 2021[15]). This can create challenges for investors in accessing land. While a World Bank project is already in the process of significantly expanding formal land registration (World Bank, 2023[16]), going forward, it would be beneficial to simplify the institutional set-up for land management and to enhance inter-institutional co‑ordination between MONRE and line ministries. In addition, in order to ensure clarity for investors on land rights in rural areas that are governed by customary land rights and in state forest areas, it would be important to accelerate the implementation of the 2019 Land Law. Finally, additional reforms to Lao PDR’s legal framework for land rights are required in order to add further clarity to existing legislation on customary land rights and formal tenure documents in relation to state forest land (Derbidge, 2021[17]; Derbidge, 2021[18]; Derbidge, 2021[19]).

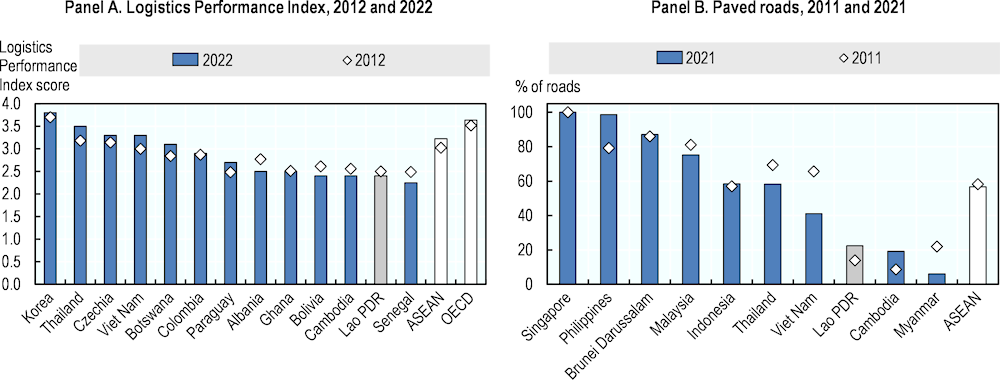

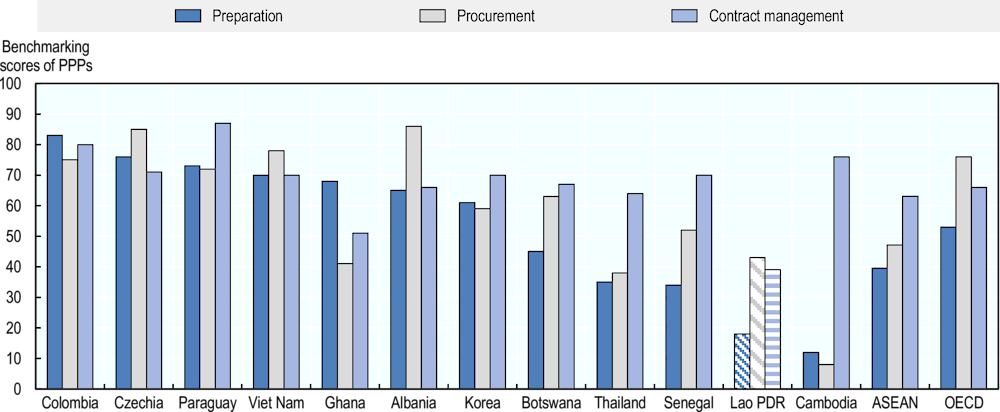

Enhance Lao PDR’s capacity for public-private partnership (PPP) delivery, strengthen infrastructure planning and improve the management of PPP-related fiscal risks. This could allow for making use of PPPs in order to improve Lao PDR’s transportation infrastructure in the long term. In order to improve PPPs’ value for money, it would be important to strengthen Lao PDR’s capacity to prepare, procure and manage PPP projects. In order to ensure that those projects with the greatest benefits are implemented first, Lao PDR requires a medium- to long-term infrastructure plan, including a pipeline of infrastructure and PPP projects with clear prioritisation based on a cost-benefit analysis. In light of the negative impact that past PPPs have had on public finances in Lao PDR, which account for almost one-half of the country’s public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt stock, it would also be important to improve the management of PPP-related fiscal costs and risks throughout the project life cycle. Allowing for effective risk sharing with private investors requires reducing the country’s high amount of public debt (see Chapter 3 on sustainable development financing) (OECD, 2017[4]; OECD, 2012[20]).

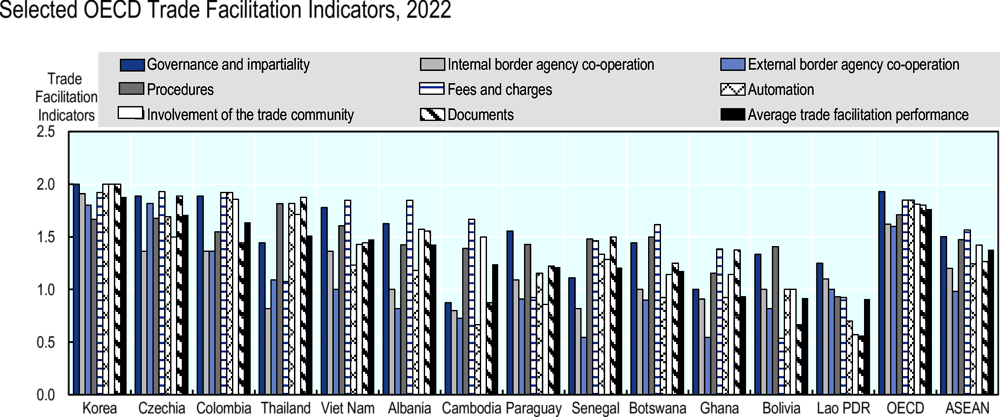

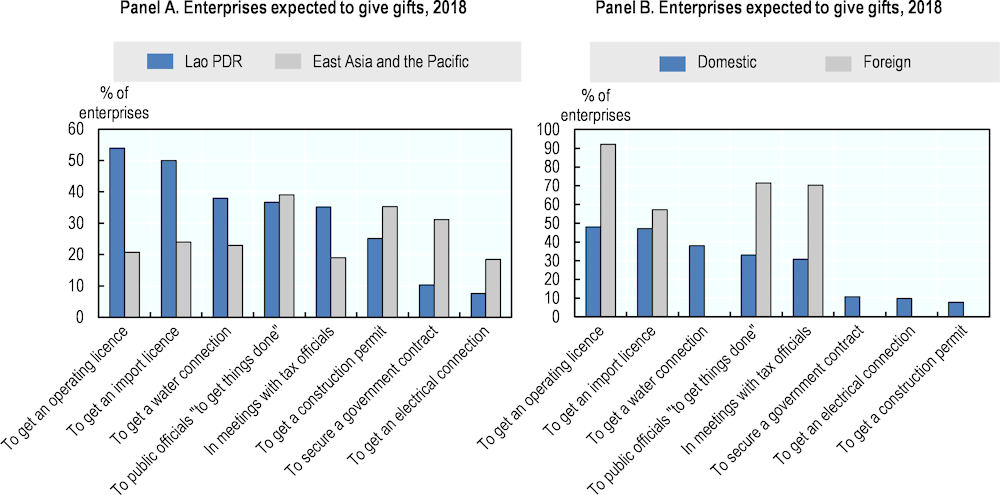

Improve the predictability of the regulatory framework for investment and the effectiveness of the court system while introducing policy tools that promote integrity among public officials. Gift-giving and informal payments, both on a small scale and in order to buy political support, can affect the efficiency of enterprises operating in Lao PDR (GAN Integrity, 2020[21]; ECCIL, 2022[22]). In order to reduce opportunities for corruption, first and foremost, Lao PDR requires a more stable, clearer, more predictable and more consistently applied regulatory framework for investment and an effective, fair and independent court system. An effective public procurement system that disburses public funds sustainably and efficiently is another critical element (OECD, 2015[12]). In addition, improved human resource management, training and counselling could enhance the integrity of lower-ranking public officials in Lao PDR. Integrity tools and mechanisms in high-risk areas such as conflict of interest and lobbying, as well as political whistleblower mechanisms, could also enhance public officials’ integrity (OECD, 2015[12]).

In addition, there are several other policy areas where implementing reforms would be highly beneficial. Recommended reforms include the following:

Simplify Lao PDR’s institutional and regulatory framework for starting an investment project. A large number of institutions are involved in this process, and there are three different avenues for obtaining an investment licence, depending on the sector and type of investment. Combining the responsibility for issuing investment licences for different types of investments under the umbrella of a single institution and reducing the number of institutions involved in the allocation of investment licences could speed up the licensing process, enhance efficiency, increase transparency and solve co‑ordination problems between entities.

Strengthen the implementation of social and environmental safeguards for investment projects. Lao PDR’s Law on Investment Promotion contains detailed social and environmental obligations for investors. In addition, two types of environmental impact studies exist in Lao PDR, and environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are mandatory for most investment projects. However, it has been reported that EIAs are treated as just a formality, with limited follow-up or impact on project design. In addition, the monitoring and inspection of environmental obligations could be improved.

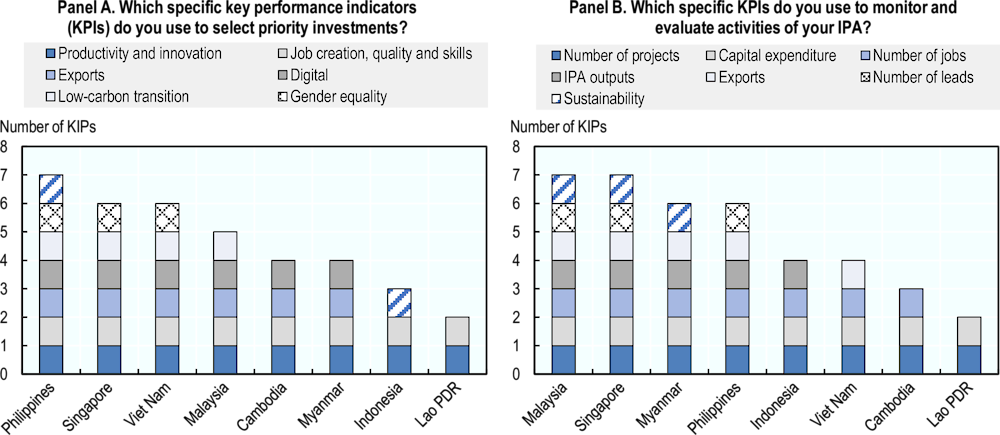

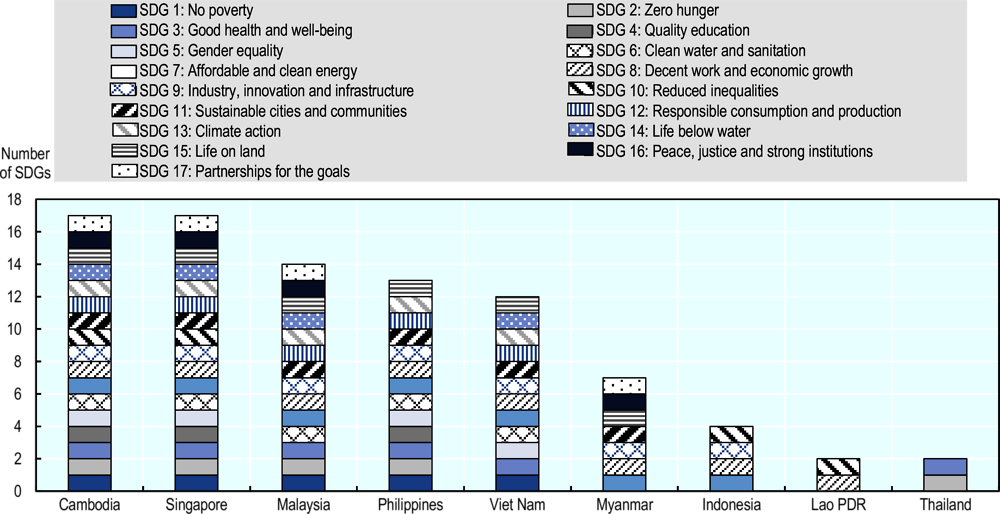

Develop more sophisticated and better targeted policies, activities and tools for investment promotion, which should include a greater focus on environmental and social sustainability. Lao PDR would benefit from a clear and coherent inward investment promotion strategy that articulates the government’s vision on the contribution of investment towards environmental protection and social development. More targeted investment promotion efforts, including investor targeting and lead generation, could attract greater investment in Lao PDR’s nine priority sectors, many of which advance social and environmental goals. Tools such as a local supplier database, business matchmaking and supplier development services could encourage more local linkages between international investors and domestic enterprises. It would also be important to introduce more key performance indicators (KPIs), both for selecting priority investments and for monitoring and evaluating the IPD’s activities, including KPIs linked to the environmental and social impacts of investment projects. Finally, in order to allow the IPD to develop these tools and activities, it would be beneficial to gradually endow it with more and better human and financial resources, as well as technical and managerial skills.

Increase positive spillovers from Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to the local economy and improve SEZs’ social and environmental performance. Investment in Lao PDR’s SEZs has increased impressively since 2014. SEZs can facilitate access to land for investors in Lao PDR and offer spaces for policy experimentation. They can generate FDI, create jobs, contribute to economic diversification and upgrading, and allow for the transfer of knowledge, technology and skills. However, SEZs also generate costs, including administrative costs, forgone tax revenues as a result of tax incentives, and the cost of resettling local communities. Potentially significant profits earned by SEZ developers, combined with discretion in granting approval for new SEZs, could also create opportunities for rent seeking. In addition, international experience shows that SEZs often face challenges in generating linkages with the local economy and creating quality jobs. Lao PDR could increase the positive impacts and spillovers from SEZs to the local economy through the right policy and regulatory mix, by encouraging local business linkages, and through skills development. At the same time, comprehensive and strategic planning of SEZ development could reduce opportunities for rent seeking. There is also scope to improve the regulation of the social and environmental aspects of SEZs in order to limit their negative externalities on the environment and local communities.

Redesign tax incentives to be based on expenditure rather than income and to more actively advance social and environmental goals. A good enabling environment is more important for attracting and retaining investors than generous tax incentives are. While investment tax incentives can be complementary to a good enabling environment for investment, Lao PDR could consider phasing out the use of income-based incentives in favour of expenditure-based incentives, such as accelerated depreciation and tax allowances or credits. Income-based tax incentives generally attract investments that are already profitable early in the tax relief period, while expenditure-based tax incentives reduce specific costs, thereby encouraging investments that might not occur without the incentives. In addition, incentives should be designed to encourage positive spillovers to the economy and society, such as local linkages, training and skills development, and environmental protection. Incentives for investors that offer training could potentially contribute to bridging Lao PDR’s skills gap. It would also be important to reduce discretion in the allocation of incentives for concessions (which creates avenues for corruption) and to improve monitoring and evaluation of investment tax incentives.

Intensify efforts aimed at promoting and implementing international RBC and due diligence standards in the local context. First and foremost, this includes developing an institutional and policy framework for RBC, including a special dedicated RBC body or government focal point and a national RBC policy or action plan. RBC efforts should also be incorporated more systematically into investment promotion activities. In addition, home-grown RBC programmes targeted at specific high-risk industries, such as the mining, hydropower and agricultural sectors, could be developed in order to raise awareness and encourage the implementation of due diligence in business practices. Lao PDR would also benefit from better access to remediation and grievance mechanisms for addressing the negative impacts of investment projects (particularly the negative environmental and social impacts). RBC for concession investments could be improved through including stronger safeguards in concession agreements and making these agreements public.

This chapter, which is organised into eight sections, examines how to encourage more sustainable investment in Lao PDR that contributes to social and environmental goals. The first section examines trends in and characteristics of FDI as well as the impacts of such investment on the environment and society. The following subsections evaluate policies to better harness investment for Lao PDR’s sustainable development. Section two analyses overarching challenges for investors in Lao PDR and presents policy options to tackle these challenges. Section three assesses the governance and institutional framework for investment, and section four analyses the legal and regulatory framework. Section five analyses investment promotion and facilitation policies in Lao PDR, while section six evaluates Lao PDR’s SEZs. Section seven examines Lao PDR’s framework for investment tax incentives. Finally, section eight assesses RBC in Lao PDR.

Trends, characteristics and impacts of FDI in Lao PDR

In 1986, Lao PDR started a structural reform process to gradually transition from a centrally planned economy to a more open, market-led economy under the New Economic Mechanism. Lao PDR joined ASEAN in 1997. This supported its integration into the regional and global economy. Lao PDR’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in February 2013 and the creation of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015 further accelerated the country’s economic reforms and integration into the world economy (OECD, forthcoming[23]) (OECD, 2017[4]).

Since 2006, FDI inflows to natural resource sectors in Lao PDR from China and other neighbouring countries have increased impressively

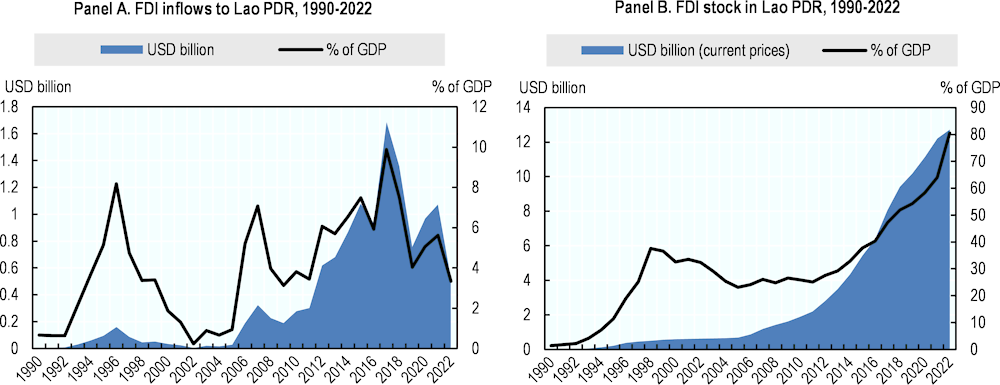

FDI inflows to Lao PDR increased impressively between 2006 and 2017, following a brief peak in 1996 (Figure 5.1, Panel A). FDI inflows to Lao PDR peaked in 1996, but declined thereafter as a result of the Asian Economic Crisis (IFC, 2021[24]). In 2006, FDI started rising sharply as a result of the Lao PDR government’s TLIC (nayobay han din pen theun)1 policy, which facilitated large concession investment projects in the hydropower and mining sectors and, to a lesser extent, in the agricultural sector (largely focused on rubber, eucalyptus and cash crops) (World Bank, 2006[1]). Many of these investment projects were facilitated through PPP, especially in the case of hydropower. Following a decline during the 2007‑08 global financial and economic crisis (IFC, 2021[24]), FDI started expanding rapidly again in 2012, peaking at inflows of USD 1.69 billion in 2017. This compares with inflows of USD 187.4 million in 2006. Since 2012, Lao PDR has more than quadrupled its FDI stock in terms of absolute value (Figure 5.1, Panel B).

FDI inflows to Lao PDR have decreased gradually since 2017, but remain significant. FDI inflows started declining in 2018, experienced a short rebound in 2020‑21, but continued decreasing in 2022. This decline can be attributed to Lao PDR’s high amount of public debt and deteriorating creditworthiness, which has rendered risk sharing between private investors and the government through PPPs more difficult (see the Chapter 3 on sustainable development financing). The COVID‑19 pandemic, which hit the country in 2020, has also contributed to the decline in FDI inflows. In addition, Lao PDR’s challenging macroeconomic situation is discouraging investors. Despite this decline, however, FDI inflows to Lao PDR remain significant.

FDI has been one of the main drivers of economic growth in Lao PDR over the last two decades. Between 2006 and 2017, which is the period during which FDI inflows to Lao PDR increased most dramatically, GDP growth averaged 7.7% annually. This compares with only 5.4% GDP growth in ASEAN member states, 3.5% in Thailand and 6.3% in Viet Nam. Among ASEAN Member States, only Myanmar experienced higher average GDP growth during this period (8.9%) than Lao PDR (World Bank, 2024[3]). FDI has contributed to economic growth in Lao PDR mainly through capital accumulation and the exploitation and export of Lao PDR’s natural resources (OECD, 2017[4]; CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]).

Figure 5.1. FDI inflows to Lao PDR have increased impressively since the mid-2000s

Source: (UNCTAD, 2023[25]), Bilateral FDI database on flows and stocks, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.FdiFlowsStock (accessed on 15 October 2023).

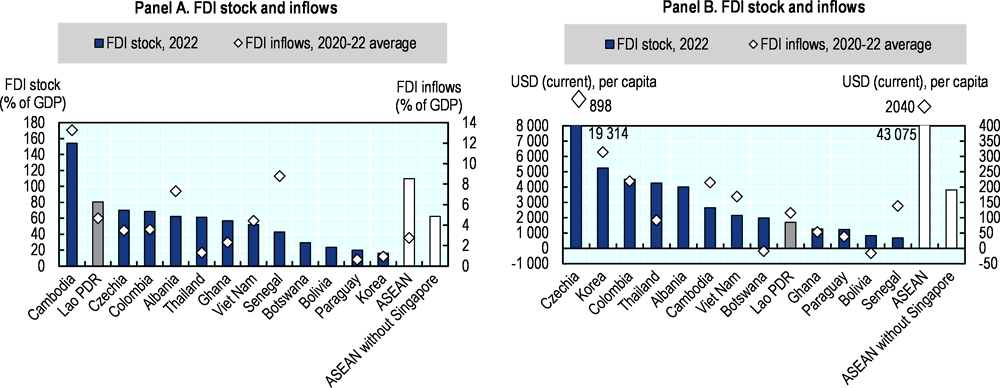

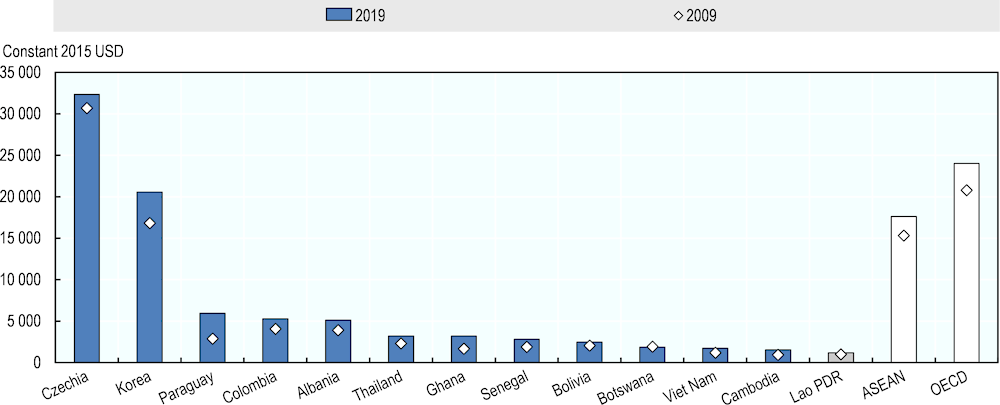

Lao PDR is performing well in terms of FDI as a share of GDP compared with other countries in the ASEAN region and elsewhere in the world, but less so when FDI is measured per capita. Lao PDR’s FDI stock amounts to 80% of its GDP; this is more than the share in most comparator countries and is 20 percentage points higher than in Thailand and 30 percentage points higher than in Viet Nam (Figure 5.2, Panel A). In ASEAN member states, only Cambodia and Singapore have a higher FDI stock than Lao PDR when measured as a share of GDP. Average FDI inflows to Lao PDR (as a percentage of GDP) were almost three times higher than in Thailand, almost twice as high as in ASEAN member states and above those in Viet Nam between 2020 and 2022. However, Lao PDR’s good performance can be partly attributed to the country’s relatively low GDP per capita, and the country is not performing as well when considering the FDI stock and inflows per capita (Figure 5.2, Panel B): Lao PDR’s FDI stock per capita is only 40% of Thailand’s and 60% of Cambodia’s. FDI inflows per capita were 30% lower on average than those in Viet Nam between 2020 and 2022.

Figure 5.2. Lao PDR is performing well compared with other countries in the Southeast Asia region and with countries elsewhere in the world in terms of FDI as a share of GDP, but FDI remains relatively low when measured on a per-capita basis

Note: “Bolivia” refers to “Plurinational State of Bolivia”.

Source: (UNCTAD, 2023[25]), Bilateral FDI database on flows and stocks, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.FdiFlowsStock.

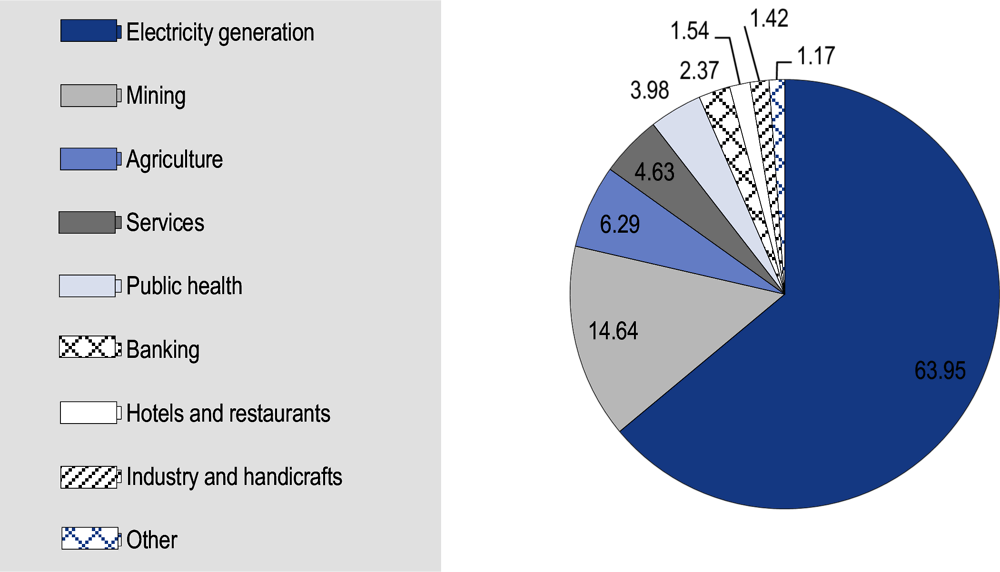

Most FDI in Lao PDR is directed towards natural resource sectors, largely through land concessions. FDI in Lao PDR is concentrated in electricity generation, largely hydropower (63.7%) and mining (14.6%) (Figure 5.3). Agriculture is the third-largest recipient sector of FDI (6.3%). On the other hand, investment in more technology- and labour-intensive sectors such as manufacturing (handicrafts and industry: 1.4%) remains relatively low. Investment in tourism (hotels and restaurants: 1.5%) accounts for only a small share of total FDI as well. Most investment in natural resources occurs through land concessions, frequently through PPPs, especially in the case of hydropower: between 1989 and 2018, the area under land concessions in Lao PDR increased from approximately 200 000 hectares (ha) to approximately over a million ha. Forty-five percent of these concessions are agriculture concessions, 41% are mining concessions, 14% are tree plantation concessions and 1% are concessions for hydropower stations (CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]).

Figure 5.3. Investment in Lao PDR is concentrated in electricity generation and mining

Approved foreign and domestic investment projects by sector, 2017‑21

Source: (IPD, 2021[26]), Statistics, https://investlaos.gov.la/resources/statistics/ (accessed on25 September 2023).

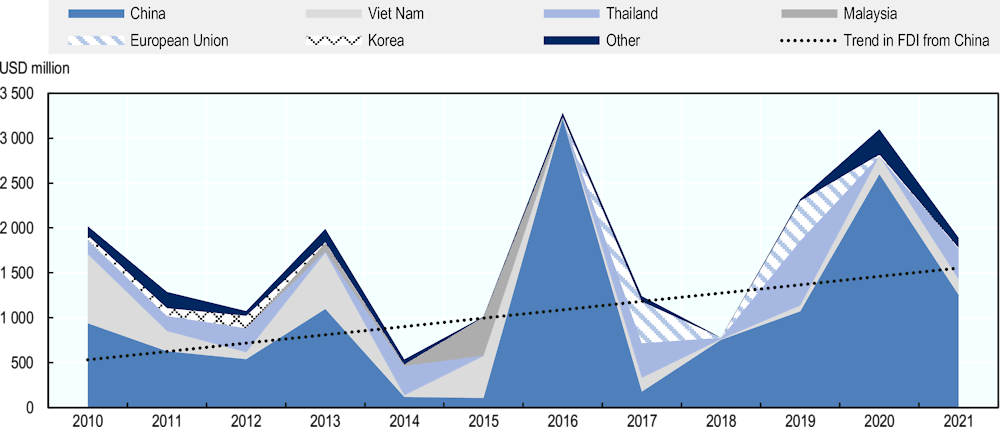

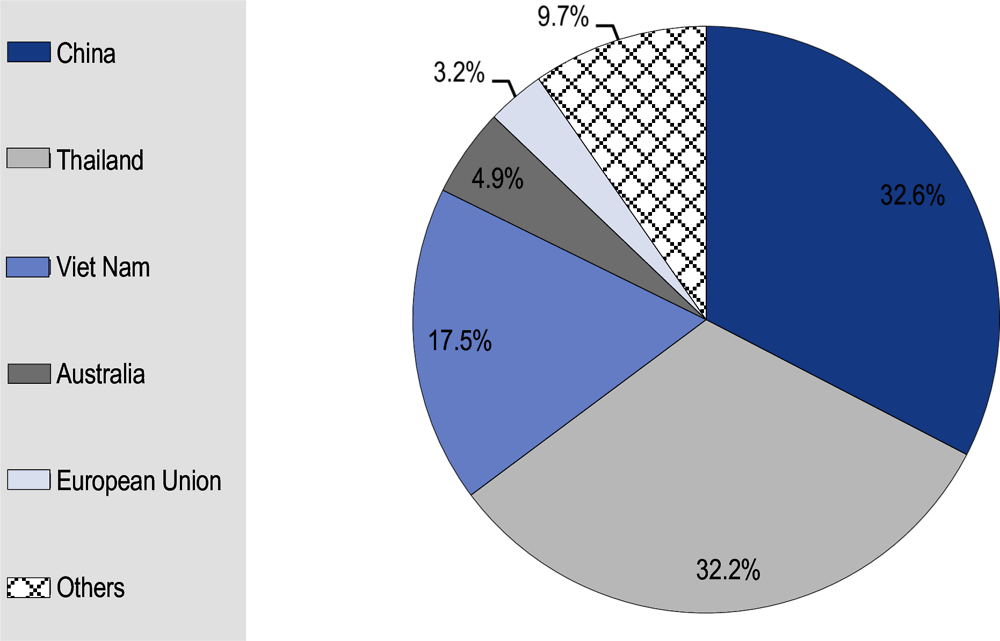

FDI in Lao PDR is dominated by China, which accounted for 66% of FDI inflows to Lao PDR and for 63% of Lao PDR’s FDI stock in 2021 (Figure 5.4). FDI from China has been increasing over time: between 2012 and 2016, an average of 42.5% of Lao PDR’s FDI inflows originated from China, but this number rose to 60.6% between 2017 and 2021. FDI from China peaked in 2016 at USD 3.2 billion and again in 2020 at USD 2.6 billion. These peaks and the overall increase in Chinese FDI coincide with the construction of the Boten–Vientiane railway (which connects Vientiane with the town of Boten on the Chinese border) between 2016 and 2021, and the expressway connecting Vientiane with Vang Vieng, both of which were funded by Chinese investors through PPPs (Medina, 2021[27]; Xinhua, 2020[28]). In addition, China has been one of the most important investors in hydropower and mining in Lao PDR in the past, and it has also invested in agriculture, real estate, and entertainment and tourism sites. Other important countries of origin of FDI in Lao PDR are Thailand, Viet Nam and France; Thailand accounted for 31.5% of Lao PDR’s FDI stock in 2021 (IMF, 2023[2]).

Figure 5.4. China is the main country of origin of FDI inflows to Lao PDR, and FDI inflows from China have been increasing

FDI inflows to Lao PDR by region of origin, 2010‑21

Note: The linear trend line for FDI inflows from China is calculated based on the actual values for FDI inflows from China using the method of least squares.

Source: (IPD, 2021[26]), Statistics, https://investlaos.gov.la/resources/statistics/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

There is scope to increase the number of jobs created, local linkages and other positive spillovers from FDI to the local economy

There is some evidence for business linkages between foreign and domestic enterprises in Lao PDR’s manufacturing sector. The evidence suggests that foreign enterprises in Lao PDR’s manufacturing sector sourced approximately one-half (49%) of inputs locally in 2018, in line with the East Asian and Pacific average (50% of inputs sourced locally) (World Bank, 2018[29]). This relatively high share of locally sourced inputs can most likely be attributed to the subcontracting of local garment producers by foreign enterprises for activities such as cut, make and trim (OECD/UNIDO, 2019[30]). In addition, this result relies on a very small number of foreign manufacturing enterprises and may not be representative of the whole sector.

Overall, however, Lao PDR would benefit from FDI that creates more quality jobs and business linkages with the local economy. Lao PDR’s manufacturing sector is small and receives only a small share of FDI. The bulk of FDI in Lao PDR is directed towards natural resource sectors such as mining and hydropower, which are capital intensive, unsustainable over time and conducted in isolation from other economic activities, and these sectors create few jobs and business linkages with domestic enterprises. In addition, foreign enterprises often experience difficulties in hiring skilled labour locally in Lao PDR and therefore tend to import a relatively large share of workers in sectors such as construction (OECD, 2017[4]; IFC, 2021[24]). Even in SEZs, which host many of Lao PDR’s foreign manufacturing companies where jobs are more labour-intensive than on natural resource projects, the number of jobs created remains only moderate, at 8.9 jobs overall and 4.9 jobs for domestic workers per USD 1 million invested (SEZO, 2023[31]). This compares with 12.8 jobs per USD 1 million invested in SEZs in Poland (as of 2018) (UNCTAD, 2019[32]).

Lao PDR could encourage more positive spillovers from FDI in terms of local environmental practices. Foreign investors can have a positive impact on environmental safeguards and protection because of the more climate-friendly business practices they adopt in order to conform to more stringent international environmental standards. One of the most important channels for such spillovers is through supply chain relationships with domestic suppliers, partners and buyers. Foreign enterprises can, for example, influence their suppliers’ practices by requiring environmental certifications or adherence to certain standards as a precondition for doing business. Foreign enterprises may also share knowledge and technologies with their suppliers in order to help improve the environmental outcomes associated with their economic activities (OECD, 2022[33]). Since the bulk of FDI in Lao PDR is directed to natural resource sectors, few supply chain linkages occur and there are thus limited opportunities for positive spillovers in terms of environmental and social standards and protection. In the hydropower sector, dam projects financed by international donors such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) usually take the EIA process very seriously and aim to comply with international social and environmental safeguards, such as the “No Net Loss Biodiversity” principle (OECD, 2017[4]). However, potential positive spillovers to suppliers or to hydropower dam projects financed by other investors have not been evaluated.

Opportunities and challenges in key investment sectors

Electricity generation

Lao PDR is one of the richest countries in hydropower resources in Southeast Asia and is one of the region’s largest generators of hydroelectric power. Approximately 70% of electricity in Lao PDR is generated from hydropower, while the remainder is largely generated from coal (IRENA, 2023[34]). Lao PDR has more than 80 operational hydropower dams, two of them on the Mekong River, with a total generating capacity of 9 483 megawatts (MW). An additional 30 hydropower dams are under construction and more than 200 are planned (IHA, 2023[35]).

FDI in hydropower in Lao PDR originates mainly from China and Thailand and has been influenced by growing demand for electricity in neighbouring countries. Lao PDR has experienced rapid growth in installed hydropower capacity since 1993, when it opened the electricity generation sector to foreign investment. Thailand is the largest investor in hydropower in Lao PDR and the largest market for Lao PDR’s hydropower exports. In 1993, Lao PDR and Thailand signed their first memorandum of understanding (MOU), aiming to achieve 1.5 gigawatts (GW) of installed hydropower capacity in Lao PDR to supply the Thai market. This MOU has been amended several times since 1993, and in 2022, Lao PDR signed an agreement with Thailand to export 10 500 MW of hydropower to the Thai market (Yong, 2023[10]; IHA, 2023[35]). Viet Nam is a much less important importer of Laotian electricity than Thailand, but it does plan to expand electricity imports from Lao PDR. In 2022, Lao PDR signed MOUs with Viet Nam to export 8 000 MW of electricity to serve the Vietnamese market by 2030 and to implement 25 projects with a combined capacity of 2.18 GW (IHA, 2023[35]; Greater Mekong Subregion Secretariat, 2022[36]). In 2021, Lao PDR exported 21 872 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity to neighbouring countries, more than 50% of the total amount of electricity it generated (World Bank, 2023[37]; IRENA, 2022[38]).

Improving the environmental and social sustainability, safety, and rentability of hydropower development in Lao PDR

It is important to reduce adverse social and environmental impacts of hydropower development. Large-scale hydropower dams in Lao PDR have been associated with negative effects on water quality and sediment flows, hydrology and water levels, aquatic ecosystems, biodiversity, fish migration and capture fisheries, food security, and the livelihoods of local populations. Fluctuating water levels and the loss of nutrient-rich sediment flows, which are blocked by dams, negatively affect agricultural productivity and the livelihoods of communities that depend on agriculture. Mekong River hydropower dams also obstruct fish migration routes, thereby affecting food security and the livelihoods of local communities that rely on fishing. Fish constitutes an important source of protein in Lao PDR, particularly for vulnerable and poor communities (Yong, 2022[6]; OECD, 2017[4]; Intralawan et al., 2018[7]). The total cost2 of the two already constructed and seven planned hydropower dams on the mainstream Mekong River in Lao PDR, plus two hydropower dams in Cambodia, is estimated at USD 18 billion. This outweighs the benefits from electricity generation, improved irrigation and flood control from these dams, which are estimated at USD 11 billion (Intralawan et al., 2018[7]).

It would also be beneficial to improve the safety of hydropower dams in Lao PDR. Maintenance of dams is often limited because of the Lao PDR government’s lack of capacity and a shortage of skilled workers such as maintenance technicians and engineers. This has led to concerns about the safety of many older dams. In 2018, the Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy dam in Champassak province collapsed, causing 71 deaths, displacing 14 440 people, and severely damaging 4 160 ha of farmland, which remains largely covered with mud and debris as of 2024. Similar so-called “saddle dams” exist in several other locations in Lao PDR and have not been replaced or reinforced since the collapse of the Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy dam (RFA Lao, 2022[39]; Inclusive Development International and International Rivers, 2019[40]).

There is scope to increase the benefits linked to hydropower development for Lao PDR through an improved design of power purchase agreements (PPAs) and better export management. Many hydropower dams in Lao PDR have been delivered through PPPs. The conditions of the PPAs signed by Électricité du Laos (EDL) with the private owners of hydropower dams are in many cases unfavourable for EDL (see the section on PPPs). For example, an independent review found that the 29‑year PPA between the government of Lao PDR and the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) for the Xayaburi Dam, the first dam built on the mainstream Mekong River in Lao PDR, places the government of Lao PDR in a risky and disadvantaged position with EGAT (Yong, 2023[10]). Moreover, despite being a net electricity exporter, Lao PDR has to import electricity during the dry season as a result of fluctuating water levels combined with a fragmented electricity grid. The cost of these electricity imports from Thailand (USD 0.11 per kilowatt hour (kWh)) is twice the rate of Lao PDR’s electricity exports to Thailand (USD 0.05 per kWh) (Yong, 2023[10]).

Abundant investment opportunities remain in Lao PDR’s energy generation sector despite several challenges

Despite the challenges outlined above, abundant investment opportunities remain in Lao PDR’s electricity generation sector. Other renewables (such as wind or solar power, which are frequently used to complement hydropower) and storage technologies (such as battery storage or pumped storage) constitute opportunities: complementing hydropower with these technologies could enable a reduction in the seasonality of electricity generation and the variability of Lao PDR’s power supply, thereby allowing the country to become a more reliable energy exporter and to increase the prices it charges for power exports. One example of such complementary power generation is the 600 MW Monsoon Wind Power Project close to the Vietnamese border, which is currently under development. The Monsoon Wind Power Project is financed by several international financial institutions, donors and private investors, including the ADB (ADB, 2023[41]). In addition, there are also opportunities to expand electricity exports to Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam; however, exports to Malaysia and Singapore are constrained by weak interconnecting infrastructure in central and Southern Thailand (World Bank, 2021[42]).

In order to continue expanding electricity generation and fully exploiting existing hydropower, significant investment in Lao PDR’s transmission and interconnection infrastructure would be required. Lao PDR’s electricity grid is fragmented across three regional grids. As a result of this fragmentation, surplus electricity generated cannot always be used or exported. Further expansion of hydropower generation capacity and exports as well as those of other renewable energy sources would require investment in domestic transmission infrastructure and in the regional interconnection of Lao PDR’s electricity grid (OECD, 2017[4]). Investment needs in domestic transmission and interconnection infrastructure are estimated at USD 1.2‑1.7 billion (World Bank, 2021[42]).

In planning and designing additional hydropower dams, it will be important to carefully assess the impact of climate change. Climate change may affect Lao PDR’s hydropower generation capacity through prolonged droughts and water shortages. This was already the case between 2019 and 2021, when water levels in the Mekong River fell to unprecedentedly low levels. This can potentially compromise the economic viability of hydropower dams in Lao PDR. In addition to climate change, uncoordinated investment in hydropower dams by different operators could also affect water levels and, in turn, Lao PDR’s hydropower generation capacity (Yong, 2022[6]).

Reducing the debt of Lao PDR’s public electricity company Électricité du Laos (EDL) could facilitate future investment in Lao PDR’s electricity sector. EDL accounts for 45% of PPG debt, which stood at 112% of Lao PDR’s GDP in 2022 (World Bank, 2023[43]). This debt is largely the result of disadvantageous investments in electricity generation (mainly hydropower) and transmission infrastructure by EDL, financed to a large extent through PPPs with limited investment rationale and which were not appropriately designed and managed (see the section on PPPs) (World Bank, 2021[42]). This significant amount of debt compromises EDL’s creditworthiness and limits its scope for signing PPAs for new investment projects in renewable energies. One option for electricity producers to circumvent this problem is signing PPAs for new power plants directly with the utility companies in neighbouring countries such as Thailand or Viet Nam. This option is especially feasible when these plants are located close to Lao PDR’s borders. In the long term, it would be important to reduce EDL’s debt and to increase its creditworthiness.

Mining

Mining is the second-largest recipient of FDI in Lao PDR (15% of FDI inflows), and mining products account for more than 30% of Lao PDR’s exports. Copper, gold, silver, lignite, anthracite and gypsum account for the largest share of mining production in Lao PDR. Zinc, lead, bauxite and aluminum are also extracted in the country (Ngangnouvong, 2019[44]; IFC, 2021[24]). There are currently 49 enterprises operating in Lao PDR’s mining sector, and mining concessions are dominated by China and Viet Nam (Ngangnouvong, 2019[44]; Financial Times, 2023[45]). The largest mines in Lao PDR are Phu Bia Mining Ltd.’s Phu Kham mine (which is 90% owned by PanAust Ltd. and 10% by the Lao PDR government) and Lane Xang Minerals Ltd.’s Sepon mine (which is 90% owned by Chifeng Jilong Gold Mining Co., Ltd . and 10% by the Lao PDR government). Both are Chinese-owned and Australian-operated enterprises (OECD, 2017[4]; Ngangnouvong, 2019[44]).

In the planning and preparation process of new mines and power plants, it will be important to carefully assess such projects’ effects on the tourism sector. Mining projects and hydropower dams are frequently located in protected areas or close to important tourism and natural sites. These projects’ adverse impacts on the environment and scenery can discourage tourism. For example, the construction of two new coal power plants – Boualapha Power Plant, located in the Boualapha District in Khammouane province, and Xekong Power Plant, located in Xekong province – is currently planned or ongoing (Phonesack Group, n.d.[46]). Boualapha Power Plant was originally planned for construction very close to Hin Nam No National Park, which is proposed as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site, but the government of Lao PDR is reconsidering construction of the power plant following a call from international donors to stop the project. Going forward, it will be important to more systematically take into account the impacts of mines and power plants on tourism when deciding on the location of new projects.

Agriculture

Agriculture is the third-largest FDI recipient sector (6%) in Lao PDR, and agriculture, food and forestry products account for more than 30% of the country’s exports. Timber, rubber and sugar are important recipients of FDI and, more recently, there have also been increasing investments in banana producers. FDI in forestry and agriculture originates largely from China (primarily directed towards the acacia, eucalyptus and rubber industries), Thailand (largely sugar) and Viet Nam (mainly rubber) (OECD, 2017[4]; Financial Times, 2023[45]; CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]; Sylvester, 2018[8]). Investors largely fund producers of agricultural commodities for export, and China is the biggest export market for these products (Village Focus International/National University of Laos, 2019[9]). There has been a trend away from large-scale state land concessions and towards contract farming and non-state land leasing in Lao PDR’s agricultural sector. This has been influenced by both government policies and investors seeking alternatives to large-scale land concessions as a result of the challenges linked to accessing land (CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]; Sylvester, 2018[8]).

Lao PDR’s agricultural sector constitutes an important part of the country’s economy. The agricultural sector’s contribution to Lao PDR’s GDP has declined from close to 50% in 1990 to 14.6% in 2022. Nevertheless, this remains elevated compared with other ASEAN member states (11%) and OECD member countries (1.4%). Moreover, as much as 58.1% of Lao PDR’s population works in the agricultural sector compared with 4.8% of the population in OECD member countries and 46.5% in ASEAN Member States on average (as of 2021) (World Bank, 2024[3]). Seventy percent of agricultural land in Lao PDR is used for the cultivation of rice. Maize, Job’s tears (or adlay millet), sweet corn, rubber and coffee account for a large share of the remaining agricultural land area. In recent decades, with the increase in agricultural land concessions, exports of agricultural products and contract farming, Lao PDR’s agricultural sector has transitioned from subsistence agriculture to a more commercial orientation (Village Focus International/National University of Laos, 2019[9]; CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]).

Agricultural productivity remains low in Lao PDR. Agricultural productivity in Lao PDR, measured as value added per worker in agriculture, forestry and fishing, is only 6.7% of the ASEAN average and increased at an annual rate of only 1.8% between 2009 and 2019 (Figure 5.5). This is too slow to catch up with the agricultural productivity of more developed countries (ECCIL, 2022[22]; World Bank, 2024[3]).

Figure 5.5. Labour productivity in Lao PDR’s agricultural sector is the lowest among regional and other comparators

Value added per worker in agriculture, forestry and fishing

Note: Agricultural productivity can be defined as agricultural production per unit of input. Inputs include not only labour but also land and capital. As such, land productivity (agricultural output per unit of land) and capital productivity (agricultural output per unit of capital) constitute other measures of agricultural productivity (FAO, 2017[47]).

Source: (World Bank, 2024[3]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 25 September 2023).

Agriculture is linked to deforestation, soil pollution and land degradation. The annual deforestation rate in Lao PDR amounted to 0.3% between 1982 and 2010, and agricultural land increased by 59% between 1999 and 2011. As of 2018, forest coverage in Lao PDR amounts to 43.5% (CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]). Deforestation and land degradation can be attributed to an increase in investment in commercial plantations of short-cycle so-called “cash crops” (which are often planted in monocultures), such as cassava, bananas, starch, Job’s tears or maize, for export to neighbouring countries. These crops rapidly deplete the soil and are drivers of deforestation (Sylvester, 2018[8]). In addition, the agrochemicals used in these plantations contaminate soil and water sources (Village Focus International/National University of Laos, 2019[9]). Illegal logging, influenced by bans on logging in neighbouring countries and increased demand for timber, has also contributed to deforestation and land degradation in Lao PDR. Hydropower development and the construction of transportation infrastructure in order to access mining sites are additional but less important drivers of deforestation (OECD, 2017[4]). Land degradation is exacerbated by the high land erosion risk in Lao PDR as a result of its steeply sloping terrain and relatively shallow soil (CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]). Lao PDR’s vulnerability to climate change is further exacerbating these challenges.

The commercialisation of agriculture in Lao PDR can have adverse social impacts, including health risks and rural indebtedness. The expansion in the use of agrochemicals such as fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides and the resulting increase in pollution has created significant health risks in rural areas, especially for the communities living in these areas (Village Focus International/National University of Laos, 2019[9]). In addition, contract farming has contributed to rural indebtedness as farmers borrow money for agricultural inputs in order to improve their yields. It has also contributed to food insecurity as communities reorient their production towards market commodities (CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[5]).

These challenges in Lao PDR’s agricultural sector translate into ample opportunities for productivity- and sustainability-enhancing investment in the sector. Investment in the mechanisation and modernisation of agriculture, combined with the traditional knowledge of the sector and a better organisation of smallholder farmers, could increase the sector’s productivity and expand agricultural production and the value added generated by agriculture. The expansion of longer-cycle crops (such as coffee, tea, sugar cane, and non-timber forest products such as certain mushrooms) could reduce the damage to the environment caused by short-cycle crops such as cassava or bananas. In addition, Lao PDR’s geographic location, improving regional connectivity and the availability of suitable land constitute advantages for investment in tree plantations.

Tourism

Lao PDR’s tourism sector accounts for only a small share of FDI inflows (1.5%), but its contribution to Lao PDR’s economy is increasing. In 2020 (prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic), Lao PDR registered 4.79 million international tourist arrivals, tourism receipts accounted for 13.9% of the country’s exports, and the tourism sector accounted for 9.1% of GDP and created 300 000 jobs. Tourists originated mainly from other Asian countries, most importantly Thailand (45% of international tourist arrivals in 2019), China (21%), Viet Nam (19%) and Korea (4%) (UNDP, n.d.[48]). There are several large tourism investment projects by Chinese enterprises in development, such as a USD 9 billion project by enterprises from Hong Kong, mainland China and a Lao PDR SEZ in Champasak province, which aims to transform the have area into one of the leading tourism sites in Southeast Asia in order to attract 1.3 million visitors per year (MOIT Vietnam, 2021[49]; Clark, 2021[50]).

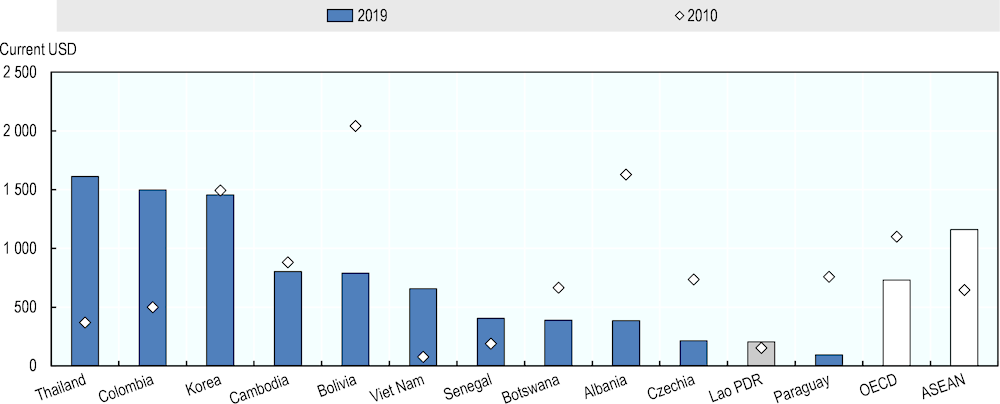

Lao PDR’s relatively low tourism receipts per arrival open opportunities for expanding tourism value added by attracting more tourists who stay longer and spend more money. Tourism receipts in Lao PDR amounted to only USD 203.30 per arrival in 2019, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic; this was less than one-fifth of the ASEAN average (USD 1 159.70) (Figure 5.6). In addition, tourism receipts per arrival have not increased quickly enough since 2010 to catch up with other countries in the region. Lao PDR’s low tourism receipts per arrival can be attributed to tourists’ short average length of stay in the country; many tourists from neighbouring countries visit Lao PDR for only one day (for example, to visit a temple), while tourists coming from farther away combine a vacation in Thailand with a short stopover in Lao PDR. Lao PDR could increase tourism receipts per arrival by designing policies to attract tourists for longer periods of time and by expanding the high-end segments of its tourism industry. Facilitating access to the country’s numerous tourist sites through improved connectivity and transportation infrastructure would be key to encouraging tourists to stay longer.

Figure 5.6. Tourism receipts per arrival in Lao PDR are only one-fifth of the ASEAN average

Tourism receipts per arrival, 2010 and 2019

Source: (World Bank, 2024[3]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 25 September 2023).

There are many opportunities to increase the contribution of tourism to Lao PDR’s economy by diversifying the sector. This includes the diversification of both the source markets of tourists and of tourism products (UNDP, n.d.[48]). The latter includes ecotourism and nature tourism, historical sites, ethnocultural tourism, adventure tourism, agriculture tourism, and wellness tourism. Improving the tourism products offered in Lao PDR could also help attract tourists for longer stays and increase the amount of money they spend in the country.

Better protecting UNESCOWorld Heritage Sites and reducing pollution from slash-and-burn agriculture around tourism sites could help make Lao PDR more attractive to tourists. Slash-and-burn agriculture is a traditional farming method that consists of burning vegetation in order to create a nutrient-rich layer of soil. Widespread seasonal burnings in Lao PDR close to key tourism sites, such as the city of Luang Prabang, cause severe air pollution and smog. This negatively affects the tourism sector through booking cancellations, tourists deciding against visiting Lao PDR during the burning season, and by tarnishing Lao PDR’s reputation as a tourism destination (Delgado and Siviero, 2023[51]; Rieger, 2020[52]). In this context, developing an effective strategy for reducing slash-and-burn agriculture in areas close to important tourist sites could boost tourist arrivals during the slash-and-burn season. In addition, it would also be important to better preserve and protect special tourism zones such as Luang Prabang. In Luang Prabang, this would require the regular maintenance and repair of traditional buildings using appropriate techniques and materials (UNESCO, 2023[53]), as well as minimising loud noise and disturbing music and preserving the traditional cityscape by preventing the over-commercialisation of the traditional city centre (Liu et al., 2019[54]).

Manufacturing

There is scope to expand Lao PDR’s manufacturing sector, which remains small and receives much less FDI (1.4% of FDI inflows) than the country’s natural resource sectors. Manufacturing accounts for only 8.7% of Lao PDR’s GDP compared with 20.5% on average in ASEAN Member States, 24.8% in Viet Nam and 27% in Thailand, 18.1% in Cambodia (in 2022) and 13.2% in the OECD (in 2021) and the sector’s contribution to GDP has stagnated and even moderately decreased over the last two decades (World Bank, 2024[3]). This reflects a very slow and stagnating structural transformation from agriculture to manufacturing and services in Lao PDR. The country’s manufacturing sector is dominated by textiles and clothing (15.7% of the manufacturing sector in 2017) and food processing (33.4% of the manufacturing sector in 2017) (IFC, 2021[24]; World Bank, 2024[3]). In addition, an electrical components manufacturing industry is developing in Lao PDR (World Bank, 2021[42]). Medium- and high-technology manufacturing accounts for only 3.8% of the sector’s value added (World Bank, 2024[3]). Manufacturing enterprises in China, Thailand and Viet Nam that want to diversify their production bases present a potential opportunity for Lao PDR to expand its manufacturing base (ECCIL, 2022[22]).

Lao PDR’s exports are dominated by natural resources and are largely directed to neighbouring countries

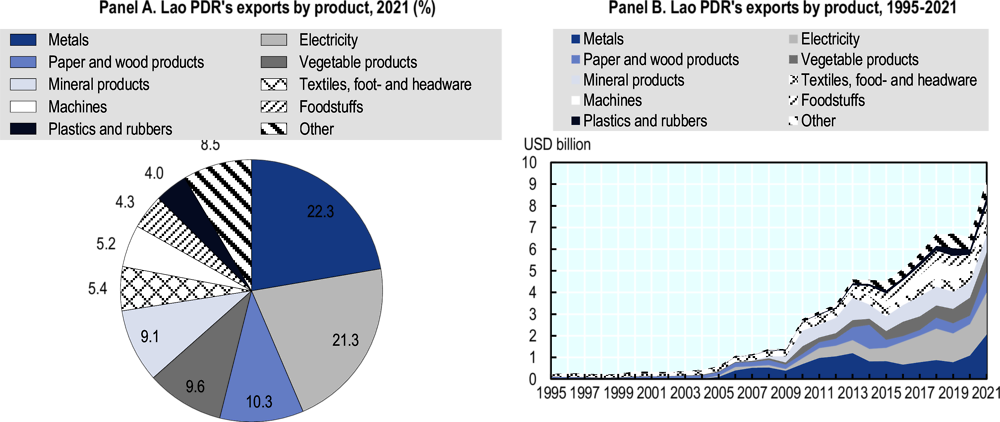

Lao PDR’s exports consist largely of natural resources and raw materials (approximately 70%), reflecting the focus of FDI. Metals (22.3% of exports) and electricity (21.3% of exports) are Lao PDR’s most important export goods, followed by paper and wood products (10.3%), vegetable products (9.6%) and minerals (9.1%) (Figure 5.7, Panel A). FDI in Lao PDR in the hydropower, mining and agricultural sectors is a major generator of and contributor to exports (OECD, 2017[4]). Lao PDR’s electricity, metal and mineral exports started expanding rapidly in 2005‑06 as a result of the increase in FDI inflows in land-based investments in the mining and hydropower sectors in the context of the TLIC policy (Figure 5.7, Panel B). Since then, Lao PDR’s electricity exports have increased at an annual growth rate of 24%, from USD 62.8 million in 2005 to USD 1.96 billion in 2021, while the country’s metal and mineral exports have increased at an annual rate of 22.9%, from USD 106.4 million in 2005 to USD 2.9 billion in 2021.

Figure 5.7. Lao PDR’s exports are concentrated in natural resources and raw materials

Source: (OEC, 2023[55]), The Observatory of Economic Complexity, https://oec.world/en (accessed on 25 September 2023).

Lao PDR’s main export destination countries are China (32.6% of exports in 2021), Thailand (32.2%) and Viet Nam (17.5%) (Figure 5.8). Exports to China consist largely of raw materials, including minerals and gold, paper and pulp, and agricultural products, especially bananas and rubber. These reflect Chinese FDI in the mining sector, the agricultural sector, and the wood and paper industry. More than one-half of Lao PDR’s exports to Thailand are electricity (59.9% in 2021), reflecting the large amount of Thai investment in hydropower. Other important export goods to Thailand are precious metals (mainly gold), agricultural products (mainly cassava) and intermediate manufacturing goods, which serve as inputs for manufacturing enterprises in Thailand such as parts for consumer electronics and optical equipment. Exports to Viet Nam consist largely of agricultural products such as rubber, beef, sugar, cassava and coffee, as well as electricity, minerals and wood products, and a small amount of intermediate manufacturing goods (Datawheel, n.d.[56]).

Figure 5.8. More than 80% of Lao PDR’s exports are directed to China, Thailand and Viet Nam

Lao PDR’s exports by partner economy, 2021

Source: (UN, 2023[57]), UN Comtrade, https://comtradeplus.un.org/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

Key opportunities to improve the investment climate

There are numerous opportunities to improve Lao PDR’s investment climate and to reduce the cost of doing business in the country. This includes increasing the availability of skilled labour and the supply of capable workers more generally. This also encompasses facilitating access to the land that the government has allocated to investors through land concessions and leases. Investment in transportation infrastructure and, in turn, a more vibrant logistics sector could reduce transportation costs. An effective judiciary and robust and fully enforced regulatory framework for investment could reduce opportunities for corruption. Better co‑ordination and policy alignment among those institutions involved in the investment process could reduce red tape and long and cumbersome business procedures.3 It would also be important to streamline and simplify the process of starting an investment project, which remains complex and involves three different channels for obtaining an investment licence. Moreover, Lao PDR requires a more stable, more predictable, clearer and more consistently applied set of policies, rules and regulations. In addition to these opportunities, it would be beneficial to stabilise Lao PDR’s macroeconomic environment. This includes reducing inflation and currency depreciation.

Improving Lao PDR’s business environment could encourage more investors to engage in activities that would limit the negative social and environmental impacts of their investment projects. This includes giving more importance to the EIA process; respecting environmental management plans; adhering to voluntary international social and environmental safeguards, such as Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC); and conducting public consultations with local communities and providing them with appropriate compensation for resettlement and expropriation. All these environmental and social safeguards generate additional business costs, which add to the already high overall cost of doing business in Lao PDR. Improving Lao PDR’s business environment and tackling overarching challenges to doing business there could allow more investors to pay these costs and ensure the sustainability of their investment projects.

This section focuses on the opportunities for policy reforms to tackle four overarching challenges for investors in Lao PDR. First, encouraging in-house training in private enterprises and improving information on those skills that are in demand in the labour market could enhance the availability of skilled labour in Lao PDR. Second, improving institutional capacity and inter-institutional co‑ordination in land administration and management and fully implementing Lao PDR’s 2019 Land Law could facilitate access to land for private investors. Third, PPPs could support the development of transportation infrastructure in Lao PDR. And fourth, a more predictable regulatory framework for investment and an independent court system combined with policy and regulatory tools that promote the integrity of public officials could reduce opportunities for corruption. The following subsections will discuss challenges for investors linked to governance and the institutional set-up, the legal and regulatory framework, and the implementation of investment policies in Lao PDR.

Investment policy options to improve the availability of skilled workers in Lao PDR

Improving the availability of skilled labour and human capital for private investors could significantly improve the investment climate in Lao PDR (IFC, 2021[24]; ADB, 2011[58]; ECCIL, 2022[22]; ECCIL, 2018[59]). Private investors in Lao PDR commonly experience shortages in technical and vocational workers such as mechanics, maintenance workers for heavy machinery, technicians and technical workers for dam maintenance, construction workers, and nurses, as well as a lack of engineers. Soft skills such as reliability, timeliness, work morale and a general willingness to work can also be difficult for investors to find. For example, some investors report that workers abandon the workplace to help their families during harvesting season and expect to return after the season is over (OECD/UNIDO, 2019[30]), while others report that workers in factories sleep during working hours. In order to fill vacancies, employers frequently have to offer higher salaries (which in many cases exceed the relatively low levels of labour productivity) or import labour from neighbouring countries, even for relatively low-skilled positions (ECCIL, 2018[59]). Both offering higher salaries and importing labour are expensive and generate additional business costs.

Lao PDR has achieved high primary school enrolment rates. Gross primary school enrolment stands at 98.5% in Lao PDR, which is in line with the average of ASEAN member states of 101.9% and the OECD average of 101.3%, as well as with most comparators in the Southeast Asian region and elsewhere around the world (Figure 5.9, Panel A). Primary school enrolment in Lao PDR has increased impressively over the last 50 years, from only 58% in 1971, but has experienced a decline between 2012 and 2021(Figure 5.9, Panel B).

Figure 5.9. Lao PDR performs worse than most comparators in secondary, tertiary and TVET enrolment, and enrolment has declined since 2012

Note: Panel A: Latest data available: Thailand (2022 instead of 2021); Bolivia, Colombia, Czechia, Ghana and OECD (2020 instead of 2021). Primary enrolment: Paraguay (2015 instead of 2021). Secondary enrolment: Paraguay (2012 instead of 2021). Tertiary enrolment: Paraguay (2013 instead of 2021). TVET indicates enrolment in vocational education among 15‑24-year-olds.

Source: (World Bank, 2024[3]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators; (World Bank, 2023[60]), Education Statistics, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/education-statistics-%5E-all-indicators (accessed on 20 September 2023).

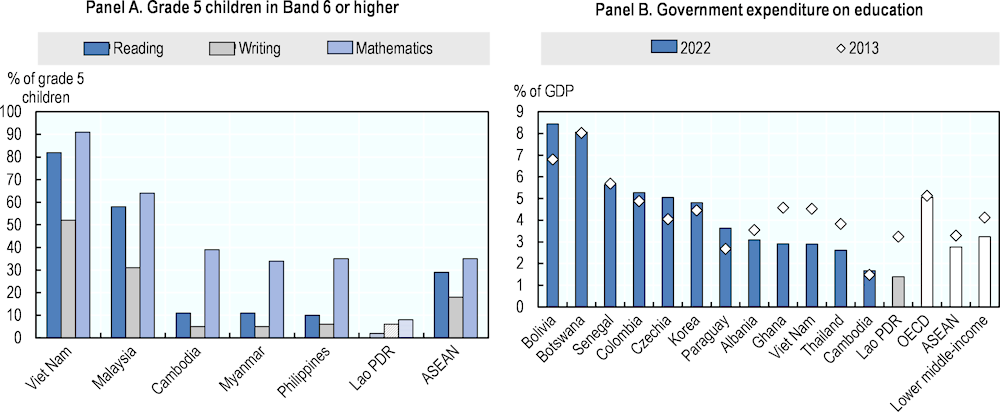

However, challenges in the quality of education and low enrolment rates above the primary level contribute to skilled labour shortages in Lao PDR. Student performance on standardised tests in Lao PDR is among the lowest in the Southeast Asian region (Figure 5.10, Panel A), indicating a low quality of education in Lao PDR. As a result, job prospects for graduates are limited. These limited job prospects do not incentivise student enrolment in school. This is reflected in low enrolment rates above the primary level: enrolment in secondary and tertiary education and in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in Lao PDR is lower than in comparator countries in the Southeast Asian region and elsewhere around the world (Figure 5.9, Panel A). The challenges in educational quality are linked to a lack of funding in the education sector. Lao PDR is the country that spends the least on education (as a share of GDP) among the included comparators (Figure 5.10, Panel B) (World Bank, 2023[61]).

Figure 5.10. Limited funding for education in Lao PDR contributes to the country’s low levels of student performance on standardised exams compared with other countries in the region and around the world

Note: Panel A. The performance of grade 5 children is evaluated in six bands for reading, in eight bands for writing and in nine bands for mathematics.

Source: Panel A: (UNICEF/SEAMEO, 2020[62]), SEA-PLM 2019 Main Regional Report, Children’s learning in 6 Southeast Asian countries, https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/7356/file/SEA-PLM%202019%20Main%20Regional%20Report.pdf; Panel B: (World Bank, 2024[3]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 20 September 2023).

The COVID‑19 pandemic and the current economic crisis in Lao PDR have further exacerbated these challenges. As a result of these crises, government spending on education has decreased significantly from its already low levels, from 3.2% of GDP in 2013 1.4% of GDP in 2022 (Figure 5.10, Panel B). At the same time, official development assistance (ODA) has also been decreasing since 2018, and private financing for education is likely constrained by the economic crisis and the COVID‑19 pandemic. In addition, the pandemic and the economic crisis have accelerated the gradual increase in unemployment in Lao PDR, which had already been observed prior to the pandemic.4 This has further reduced the already low private returns on investment in education and households’ incentives to enroll their children in school. As a consequence of the decrease in funding and the decline in the returns to education, student enrolment has further declined: primary enrolment declined from 106% (gross) in 2017 to 98.5% in 2021, secondary enrolment declined from 67.5% (gross) in 2017 to 59.8% (gross) in 2021, and tertiary enrolment declined from 15.7% in 2017 to 12.9% in 2021 (Figure 5.9, Panel B) (World Bank, 2024[3]).

High migration to neighbouring countries is another cause of the skills shortages that private investors experience in Lao PDR. Most skilled and unskilled workers in Lao PDR who are willing to work in a factory environment emigrate to neighbouring countries, where minimum wages largely exceed those in Lao PDR and there is a high demand for low-skilled labour in sectors such as infrastructure, services, manufacturing and agriculture. At present, the minimum wage in Thailand (THB 354 (Thai baht) per day, which is equivalent to approximately THB 9 000 or USD 240 per month) is three times the minimum wage in Lao PDR (LAK 1.6 million (Lao kip), or approximately USD 80 per month) (ECCIL, 2022[22]). In 2018, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, 277 845 Laotians migrated to neighbouring countries. While this figure decreased during the COVID‑19 pandemic when many workers returned to Lao PDR (IOM, 2020[63]), it is reported that migration has picked up again in 2022‑23 and that the number of migrants exceeds those registered in 2018. This recent increase in migration can be attributed to the difficult macroeconomic conditions in Lao PDR, including high and accelerating inflation and declining real wages. As a result of the increase in emigration, hiring workers has become increasingly challenging for enterprises in Lao PDR independent of workers’ skill level. This is reported in the tourism sector as well as in SEZs, where demand for labour exceeds supply (SEZO, 2023[31]).

There is scope to improve the quality of TVET in Lao PDR and to better align those skills produced by TVET institutions with demand in the labour market. TVET institutions in Lao PDR are reported to experience shortages in qualified and trained teachers, which has been aggravated by the economic crisis. Teachers frequently lack teaching skills and industry experience. TVET curricula are often outdated, not aligned with private sector needs, and do not involve sufficient practical training. Many TVET institutions lack modern facilities and the equipment, machines and tools required for the practical training of students. Private sector involvement in TVET through financing, curriculum development and delivery of practical training could be improved. TVET enrolment has been declining in high-demand skill areas where skill shortages are greatest, such as the construction sector (ADB, 2011[58]; ECCIL, 2018[59]; UNESCO/UNEVOC, 2020[64]).

Encouraging in-house training and improving information on skills that are in demand in the labour market

In order to improve the availability of workers with the right skills in Lao PDR, it will be important to encourage more in-house training by private investors. Only 24.4% of enterprises in Lao PDR offer formal training to their workers, compared with 31.2% of enterprises in East Asia and the Pacific on average (World Bank, 2018[29]). This can be partly explained by the perception among employers in Lao PDR that in-house training might be seen as a benefit-in-kind and therefore taxed. It would be important to ensure that this perception changes and employers offering in-house training to their workers are not subject to any additional tax payments or charges (ECCIL, 2018[59]). In addition, in order to encourage more in-house training by private enterprises, tax incentives for training could be introduced, such as making training costs fully or partially tax-deductible (see the section on investment tax incentives). In the context of a limited budget for education and the structural challenges in Lao PDR’s education system, private enterprises are critical for equipping workers with the right skills and bridging the skills gap in the short term.

It would also be critical to improve co‑operation and co‑ordination between the private sector, the government and educational institutions (ECCIL, 2022[22]). For this purpose, stakeholders in Lao PDR (such as business associations, employers and businesses, trade unions and non-governmental organisations, educational institutions, and government institutions) could be regularly engaged through a dedicated council or committee. This process should be as inclusive as possible and should involve a sufficiently wide range of stakeholders, including those from emerging sectors of the economy such as new technology enterprises and training providers, which may be less well-represented in traditional institutions and entities (OECD, 2019[13]). Better co‑ordination between the private sector, the government and educational institutions could help better align the educational opportunities with those skills that are in demand in the labour market.

Lao PDR already has a public-private co‑ordination body for TVET: the National TVET and Occupational Skills Consultation and Development Council. It is chaired by the Minister of Education and Sports. The Minister of Labour and Social Welfare and the President of the Lao National Chamber of Commerce and Industry (LNCCI) are its vice chairs. Other members include the Assistant Minister of Education and Sports, the Assistant Minister of Labour and Social Welfare, the Directors-General of relevant departments, the chairs of relevant TVET associations, specialised experts, and representatives of TVET facilities. The National TVET and Occupational Skills Consultation and Development Council’s role is designing legislation, regulation, policies, strategies and projects for the development and management of TVET and occupational skills training, and advising the government of Lao PDR on TVET policies and skills development issues (National President of Lao PDR, 2014[65]).

However, the National TVET and Occupational Skills Consultation and Development Council has not succeeded in building strong linkages between the public and private sectors in TVET (ADB, 2011[58]; ECCIL, 2018[59]). In practice, the Council does not convene regularly and suffers from a lack of leadership. Its members are at a very high level and the Council’s budget is limited. Twelve trade working groups were established under the Council with the objective of overseeing skills, occupational and professional standards and curricula development, and of co‑ordinating with the private sector. However, no information is available on whether these working groups still exist and convene on a regular basis. As a result of these challenges, the National TVET and Occupational Skills Consultation and Development Council has not been very successful in practice in better aligning Lao PDR’s TVET system with private sector needs or in facilitating exchanges between businesses, the government and educational institutions (UNESCO/UNEVOC, 2020[64]; ADB, 2023[41]; ILO, 2016[66]).

In order to better align its education system (and in particular TVET) with the private sector’s needs, Lao PDR requires information on those skills that are either readily available or lacking in the labour market. Individuals and enterprises alike require this information in order to make decisions about which skills to develop. The government of Lao PDR needs this information to design relevant education and training policies and programmes. An effective SAA system could identify the types of occupations, qualifications and fields of study that are currently in demand in the labour market, or that may become so in the future. Such systems should use both quantitative and qualitative methods, as well as both short- to medium-term and longer-term evaluations in order to allow for robust analysis (OECD, 2019[13]). Both Norway and Portugal have developed comprehensive SAA systems that rely on effective policy co‑ordination between different public and private institutions (Box 5.1). A labour market information system, such as a robust labour market observatory with sufficient technical capabilities, could also contribute to identifying skills needs in Lao PDR.

Box 5.1. Norway and Portugal have developed regular SAA exercises and dedicated bodies for policy co‑ordination in skills development

SAA exercises and policy co‑ordination in Norway

The Norwegian Committee on Skill Needs was formed in response to the need for an evidence-based understanding of the country’s future skills needs. The Committee plays a key role in co‑ordinating between different ministries and stakeholder bodies in the area of skills needs assessments and responses. The Committee is funded by the Ministry of Education and Research, and its secretariat is within the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills in the Ministry of Education and Research. The Committee includes 18 members who represent social partners, ministries and researchers. It is tasked with compiling evidence on Norway’s future skills needs, contributing to open discussions and the better utilisation of resources between stakeholders, and producing an annual report with analyses and assessments of Norway’s future skills needs.

The Norwegian Committee on Skill Needs uses a comprehensive set of methods and tools in order to determine Norway’s current and future skills needs. These include employer surveys, surveys of workers or graduates, quantitative forecasting models, sector studies, qualitative methods and labour market information systems. The Committee also makes use of projections. Norway forecasts skills needs 10‑80 years into the future in the healthcare sector, and 35 years into the future in the education sector. Furthermore, it carries out 20‑year general occupational forecasts, and estimates employment trends in specific industries 1 year in advance as a direct input for the planning of training and employment policy. Unusually, these skills needs are forecast at both the national and regional levels.

SAA exercises and policy co‑ordination in Portugal

Portugal’s skills needs assessment system, the Sistema de Antecipação de necessidades de Qualificação (SANQ), was created in 2014. The SANQ is co‑ordinated by Portugal’s National Agency for Qualification and Vocational Education and Training. It has a consultative board that encompasses the public employment service and representatives of workers and employers, and that board receives technical assistance from the International Labour Organization (ILO). Its diagnostic exercises assess skills needs through both a retrospective analysis of labour market trends and a forecast of the future demand for certain qualifications. The system is used to plan the delivery of TVET for young people, and Portugal is considering expanding its use in order to plan the supply of adult learning programmes. Moreover, Portugal uses inputs of skills needs assessments in order to provide young people with career guidance through its network of Qualifica centres.

Source: (OECD, 2023[67]), Multi-dimensional Review of El Salvador: Strategic Priorities for Robust, Inclusive and Sustainable Development, OECD Development Pathways, based on (OECD, 2019[13]), OECD Skills Strategy 2019: Skills to Shape a Better Future.

In addition, it would also be important to improve the quality of education in Lao PDR (including TVET) and to increase funding for education, but that topic is beyond the scope of this chapter. This chapter focuses on the issue from an investment policy perspective. Investment policies include the provision of in-house training and strategies to improve the information available on those skills that are most in demand in the labour market. Developing detailed policy advice on how to deal with structural challenges in Lao PDR’s education system is therefore beyond the scope of this chapter.

Policy options to facilitate access to land for private investors in Lao PDR

In 2019, Lao PDR adopted a new Land Law, which has significantly improved the legislative and regulatory framework for land management. The 2019 Land Law is much more detailed, informative and clear than the 2003 Land Law. The 2019 Land Law provides clearer and more detailed regulations on concessions and leases of land by foreigners and specifies that concession rights can be traded. The new law also provides clearer and more detailed information on the zoning and classification of land; land surveys and protection; changes to land categories; land administration; the acquisition, use and loss of land use rights; and the management of state land. In addition, it makes MONRE’s central and co‑ordinating role in land management clearer and defines each ministry’s rights and obligations in the management of the use of land clearly. The law also introduces national and provincial land allocation master plans, land use strategies and strategic land use plans. It also includes a prohibition on encroachment and clarifies land use rights in the context of condominiums. Going forward, in order to facilitate its implementation, the 2019 Land Law would benefit from additional details and clarity (MRLG/LIWG, 2021[15]; National Assembly, 2019[14]).