This chapter provides a development diagnostic of Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), focusing on the “prosperity”, “people” and “planet” pillars of the United Nations’ (UN’s) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It examines the impressive economic advancements fuelled by investments, commodity exports and tourism, juxtaposed with the challenges of stagnant structural transformation and unequal distribution of opportunities. Emphasising the need for a vibrant private sector in fostering employment and productivity across diverse sectors, this chapter underscores the necessity of stimulating broader-based economic growth. Under the “people” pillar of the SDGs, it highlights the imperative of prioritising human capital development and stresses the need to bolster funding capacity. Addressing environmental concerns, this chapter underscores the urgency of preserving Lao PDR’s natural wealth amid escalating environmental pressures, particularly air pollution and carbon emissions. Finally, it explores the nation’s increasing vulnerability to climate change, highlighting the need to develop integrated approaches to sustainable development.

Multi-dimensional Review of Lao PDR

2. Development diagnostic: Prosperity, people, planet

Abstract

Prosperity: Moving from booming commodities to broad-based opportunities

Impressive economic growth promoted by investments, commodity exports and tourism

Lao PDR’s economy has been one of the fastest growing in the world. With an average annual growth of 7.1% between 2000 and 2019, Lao PDR’s economy has been the second-fastest-growing economy among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member States and the 13th fastest-growing economy globally (World Bank, 2024[1]).

Booming investment was an important driver of Lao PDR’s economic success, spurring large-scale infrastructure projects and a push into the mining and energy sectors. Between 2006 and 2017, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows grew almost tenfold, from USD 187.4 million (United States dollars) to USD 1.69 billion. Investment in Lao PDR’s Special Economic Zones reached a cumulative USD 7.6 billion in 2021 (Dalavong, 2021[2]). The government’s Turning Land into Capital (TLIC) (nayobay han din pen theun) policy facilitated large concession investment projects (World Bank, 2006[3]) in hydropower (64% of investment in Lao PDR between 2017 and 2021), mining (15% of investment) and agriculture (6% of investment). Between 1989 and 2018, the area under land concessions in Lao PDR increased from approximately 200 000 hectares (ha) to more than 1 000 000 ha. Forty-five percent of these concessions are agriculture concessions, 41% are mining concessions, 14% are tree plantation concessions and 1% are concessions for hydropower stations (CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[4]).

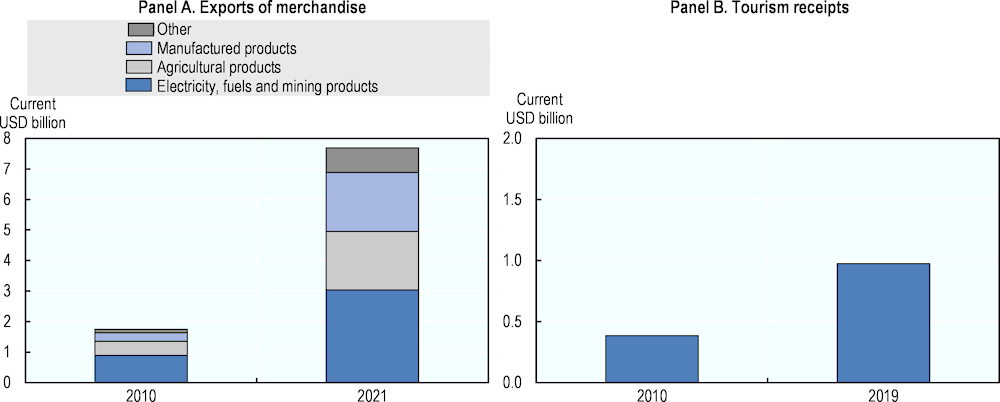

Figure 2.1. Exports: Commodities and tourism have seen strong growth

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 15 November 2023).

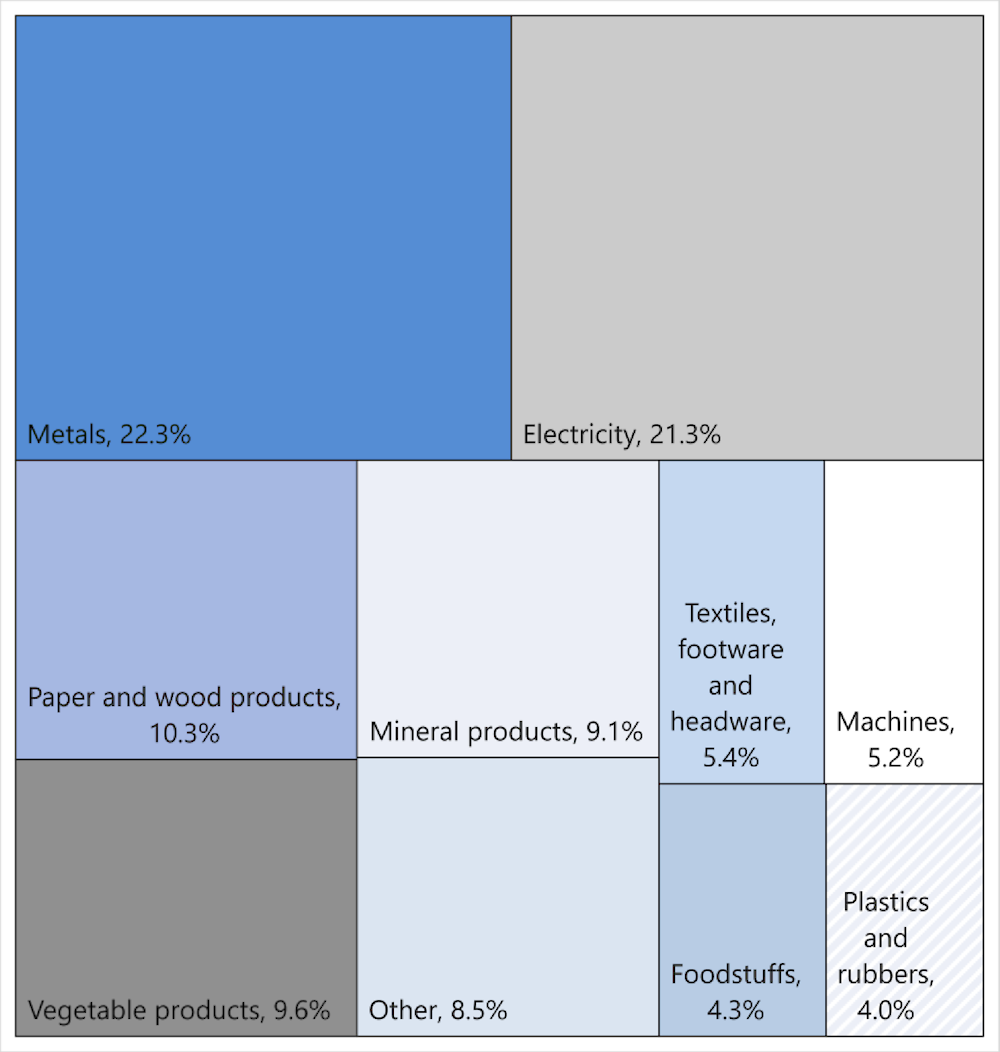

Exports grew rapidly, mirroring the investment push into energy and commodities as well as tourism expansion. Exports in goods grew more than fourfold between 2010 and 2021, reaching USD 7.7 billion in 2021 (up from USD 1.7 billion in 2010) (Figure 2.1, Panel A). Up until the COVID‑19 pandemic, tourism had kept pace with the rapid growth of other exports, and accounted for a significant share of sectors and about 10% of gross domestic product (GDP) (Figure 2.1, Panel B; Box 2.1). Large hydropower projects made electricity the second most important export product (21.3% of trade). Exports of metals and ores like gold, iron and others boomed as well, followed by agriculture- and forestry-based products like cassava, rubber (of which Lao PDR is the seventh-largest global exporter, with exports worth USD 300 million in 2021), paper and pulp. Metals (accounting for 22.3% of exports) are Lao PDR’s most important export goods, followed by paper and wood products (10.3%), vegetable products (9.6%), and minerals (9.1%). Mining products accounted for more than 30% of Lao PDR’s exports and were also the second-largest recipient of FDI in Lao PDR (15% of FDI inflows) in 2021 (Figure 2.2) (Ngangnouvong, 2019[5]; IFC, 2021[6]).

Figure 2.2. Natural resources constitute the bulk of exports

Lao PDR’s exports by category (percentage of trade), 2021

Source: (Simoes and Hidalgo, 2011[7]), “The Economic Complexity Observatory: An Analytical Tool for Understanding the Dynamics of Economic Development”, Workshops at the Twenty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. https://oec.world/en/profile/country/lao?tradeScaleSelector1=tradeScale0&depthSelector1=HS2Depth. Data from 2021 (accessed 15 January 2024).

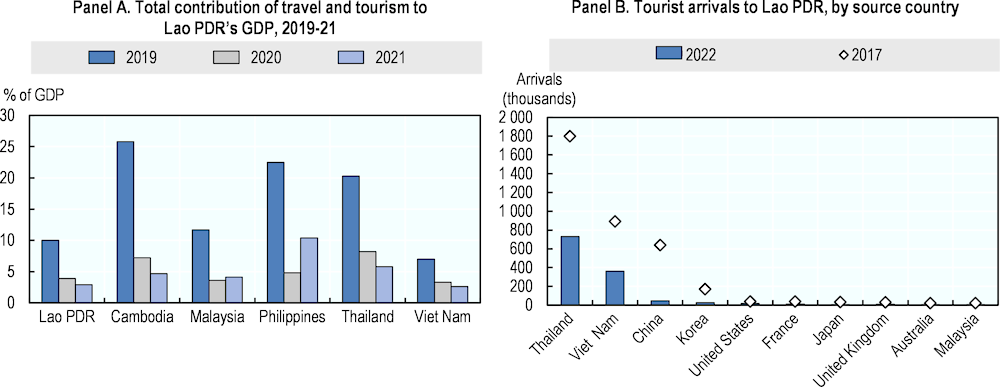

Box 2.1. Tourism in Lao PDR: An important sector with potential for revival after COVID‑19

Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020, Lao PDR registered 4.79 million international tourist arrivals, primarily from neighbouring countries. Tourism receipts accounted for 13.9% of Lao PDR’s exports, and the tourism sector accounted for 9.1% of GDP and created 300 000 jobs. The sector took a major hit when foreign tourism was restricted during the COVID‑19 pandemic. As restrictions have been lifted, the sector has started showing signs of recovery, although travel and tourism have not yet reached pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. The tourism sector’s contribution to Lao PDR’s economy

Source: Panel A: (UN Tourism, 2024[8]) “Global and regional tourism performance” (database), https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 20 November 2023). Panel B: (UN Tourism, 2024[8]) “Global and regional tourism performance” (database), https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 10 December 2023).

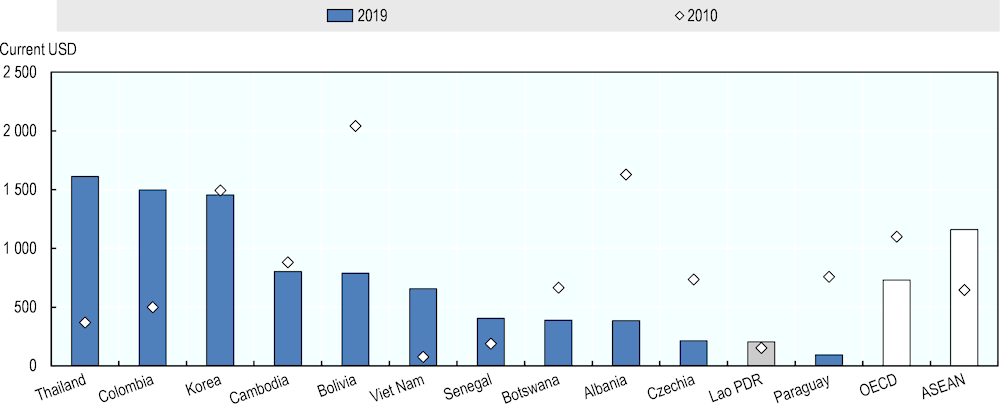

Attracting tourists who stay longer and spend more would increase resources. Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, tourism receipts per arrival in Lao PDR amounted to USD 203 in 2019, less than one-fifth of the ASEAN average (USD 1 160) (Figure 2.4). Many tourists from neighbouring countries visit Lao PDR for a single day only, whereas tourists coming from farther away often combine a vacation in, for example, Thailand with a short stopover in Lao PDR. There are some options for Lao PDR to attract tourists to stay longer:

facilitating access to Lao PDR’s numerous tourist sites through improved connectivity and transportation infrastructure

improving the tourism products offered in Lao PDR, including ecotourism and nature tourism, historical sites, ethnocultural tourism, adventure tourism, agriculture tourism, and wellness tourism.

Preserving tourism as a potential sector to grow. Going forward, it would be important to more systematically take into account the impact on tourism when deciding on the location of new investment projects such as mines, dams and power plants. In addition, the issue of air pollution from the traditional slash-and-burn agricultural practice, especially during the burning season, would need to be taken into consideration.

Figure 2.4. Tourism receipts per arrival in Lao PDR are relatively low

Tourism receipts per arrival, 2010 and 2019 (current USD)

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 10 November 2023).

Lao PDR’s strategic positioning within Southeast Asia and its integration with regional frameworks have been instrumental in its economic growth. In the mid-1990s, Lao PDR’s regional integration intensified as it became a member of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) and subsequently joined ASEAN. This participation in regional frameworks in fast-growing markets led to a significant increase in trade. Between 1990 and 1998, Lao PDR’s trade grew from 36% to 84% of its GDP (World Bank, 2024[1]). By 2021, ASEAN member states accounted for a substantial portion of Lao PDR’s trade, with 57% of imports and 53% of exports originating from these countries (World Bank, 2021[9]).

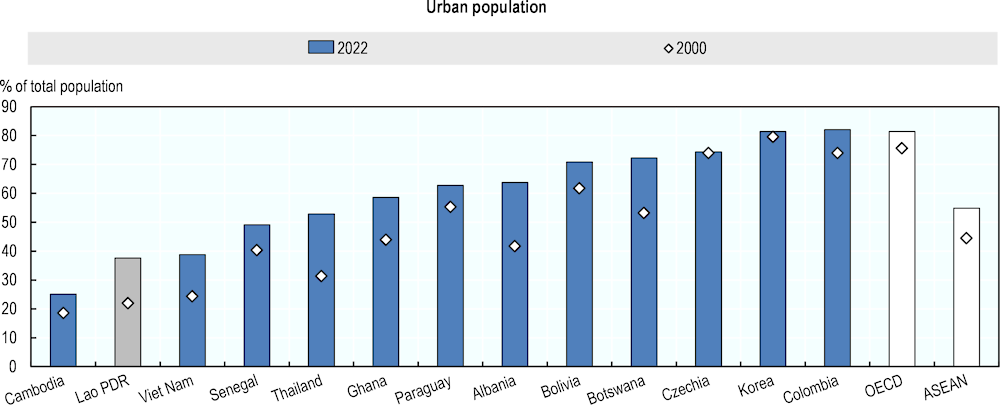

Along with its economic growth, Lao PDR has experienced rapid urbanisation that is expected to continue. Lao PDR has experienced one of the fastest rates of urbanisation growth in the Southeast Asia region and among its peers, reaching 37.6% urbanisation in 2022 (Figure 2.5). The share of urban population in Lao PDR is still low in comparison to its peers, however. Recent estimates indicate that the share of urban population in Lao PDR will reach 47.7% by 2025 (UN Habitat, 2023[10]).

Figure 2.5. Lao PDR has a growing urban population, but still has a lower urbanisation rate than its peers

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 9 November 2023).

There is also stagnating structural transformation and an unbalanced distribution of opportunities

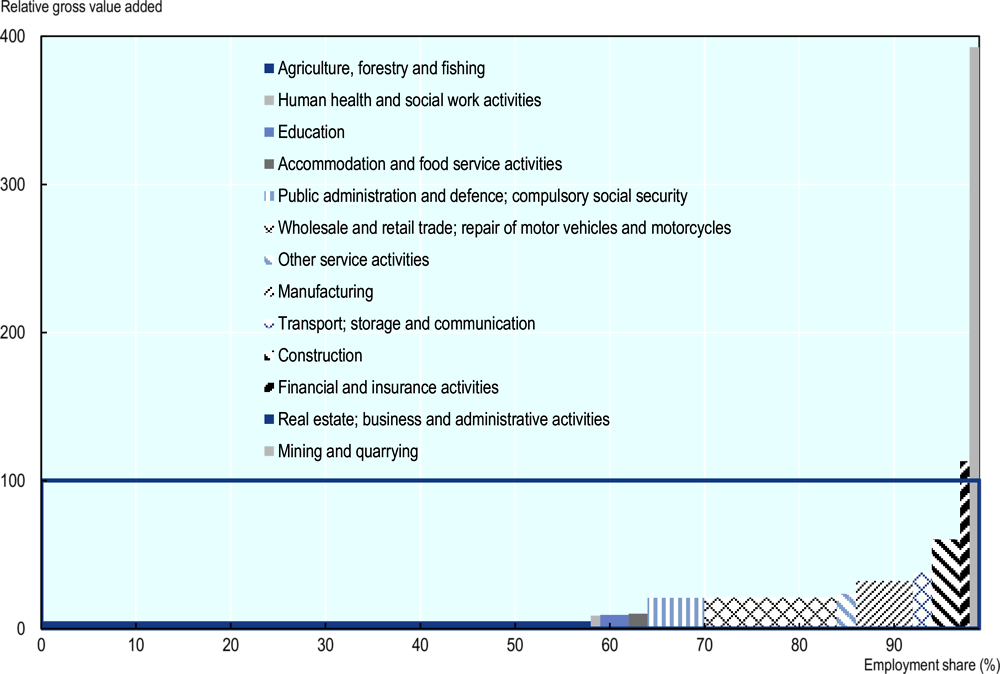

Stagnating structural transformation and an unbalanced distribution of opportunities are the flip side of the importance of commodities and the concentration of economic power. Past growth and investment in Lao PDR were highly concentrated in a few sectors and dominant state-owned enterprises (SOEs). More than 90% of workers remain in sectors dominated by informal employment, with more than 50% working in the agricultural sector, generating limited income, added value and tax revenue (Figure 2.6) (Box 2.2). Manufacturing – often the cornerstone sector for economic transformation – accounts for only 8.8% of Lao PDR’s GDP (compared with 20.5% on average among ASEAN Member States, 27.0% in Thailand and 24.8% in Viet Nam), and the sector’s contribution to Lao PDR’s GDP has stagnated and even moderately decreased since the early 2000s. The manufacturing sector is dominated by textiles and clothing (which accounted for 15.7% of the manufacturing sector in 2017) and food processing (accounting for 33.4% of manufacturing in 2017) (IFC, 2021[6]; World Bank, 2024[1]).

Figure 2.6. Lower-productivity sectors, particularly agriculture, account for a large share of employment in Lao PDR

Relative gross value added and employment share by economic sector, 2021

Note: Y-axis: 100 = average national gross value added by sector. X-axis: percentage of total employment. Weighted average productivity (y-axis) is normalised to 100; a sector with a relative gross value added greater than 100 is more productive than the average. Labour productivity is measured as the annual value added (the value of output less the value of intermediate consumption) per employee.

Source (ILO, 2023[11]), “ILO modelled estimates”, ILOSTAT (database), https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/; (United Nations, 2023[12]), UNdata (database), https://data.un.org/Default.aspx; (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (data accessed on 15 November 2023).

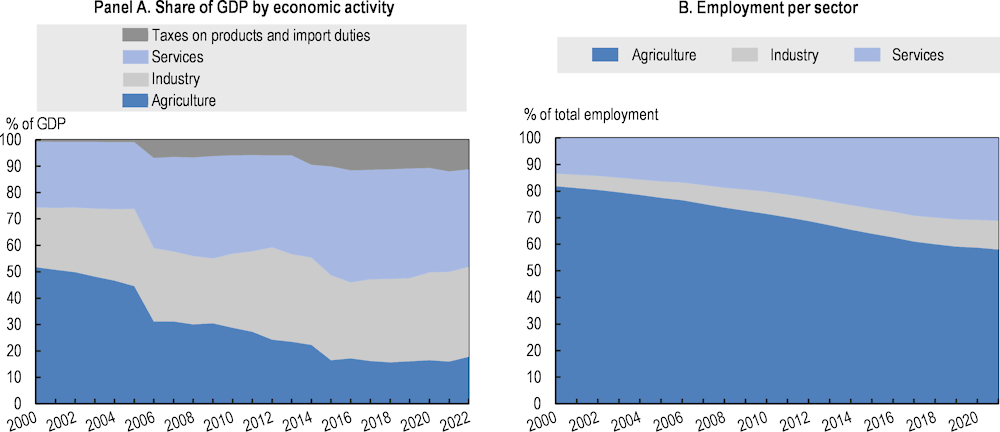

Box 2.2. Agriculture in Lao PDR: An important driver of economic growth

Lao PDR’s agricultural sector constitutes an important part of the country’s economy and involves a majority of the population. Agriculture is the main source of income and livelihood in rural Lao PDR. The contribution of the agricultural sector to Lao PDR’s GDP has been significant, but has declined over the years, from 51.8% in 2000 to 17.8% in 2022 (Figure 2.7, Panel A). Over the same time period, the agricultural sector’s share of employment has decreased from 80% to 58%, which compares with an ASEAN average of 39% (Figure 2.7) (World Bank, 2024[1]).

Figure 2.7. The agricultural sector employs a majority of the population of Lao PDR but constitutes a smaller part of the economy

Share of GDP by economic activity, and employment per sector

Note: Panel A: “Agriculture” consists of agricultural cropping, livestock and livestock products, forestry and logging, and fishing. “Industry” consists of mining and quarrying, manufacturing, electricity, water supply and sewage, waste management, and construction. “Services” consists of wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles; transportation and storage; accommodation and food; information and communication; financial and insurance activities; real estate activities; professional, scientific and technical activities; public administration and defence; education; human health and social work; and other services. Data for 2022 are based on estimates. GDP at constant market price. Panel B: Percentage of total employment is based on a modelled International Labour Organization (ILO) estimate.

Source: Panel A: (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2022[13]), Statistical Yearbook, https://laosis.lsb.gov.la/. Panel B: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 23 November 2023).

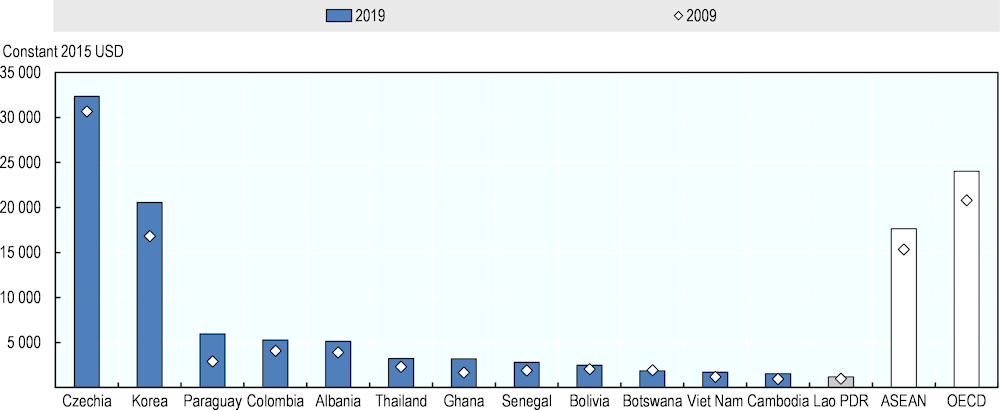

Reflecting the importance of subsistence and smallholder farming, agricultural productivity remains low in Lao PDR. While the country’s agricultural outputs have increased as a result of commercial operations, overall agricultural productivity in Lao PDR remains low. Agricultural productivity (measured as value added per worker in agriculture, forestry and fishing) in Lao PDR is only 6.7% of the ASEAN average and increased at an annual rate of only 1.8% between 2009 and 2019 (Figure 2.8) (World Bank, 2024[1]).

Figure 2.8. Agricultural productivity remains low in Lao PDR

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 29 January 2024).

Opportunities for productivity and sustainability within the agricultural sector

Lao PDR’s geographic location offers an opportunity for regional connectivity in terms of importing and exporting agricultural products. Investment in the mechanisation and modernisation of agriculture, combined with traditional knowledge and the better organisation of smallholder farmers, could help to increase the sector’s productivity. Additional opportunities include the following:

Transitioning to more environmentally sustainable practices, such as organic farming, could increase farmers’ income while improving the environment (OECD, 2024[14]).

The expansion of longer-cycle crops (such as coffee, tea and sugar cane) and non-timber forest products (such as certain mushrooms) could reduce the damage to the environment caused by short-cycle crops like cassava and bananas.

Harnessing the synergies between the agricultural and tourism sectors could lead to increased collaboration and increase value added. Tourism has many linkages with the agricultural sector, providing the potential to absorb seasonal excess labour in rural areas and encourage the production of higher-value-added agricultural goods and related products. For instance, tourism enterprises can purchase significant quantities of organic agricultural products (ADB, 2021[15]).

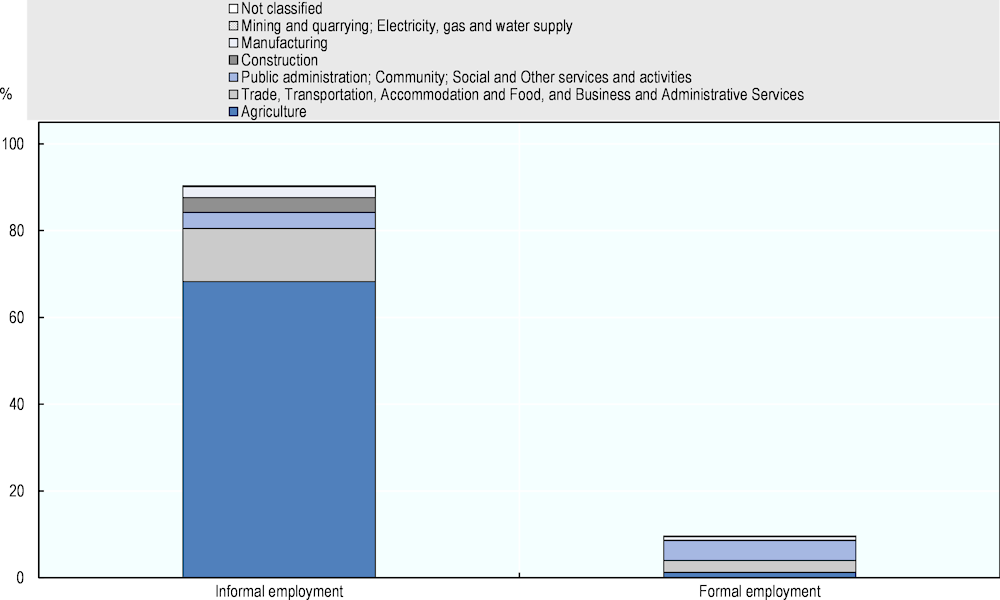

Similar to the uneven sector distribution as a share of GDP, the share of informal employment in Lao PDR stands out in comparison to other countries and illustrates the concentration of opportunity among a small share of the population. In the Labour Force Survey 2022, informal economy workers1 accounted for 90.5% of the workforce (Figure 2.9). The share of informal economy workers was significantly higher in rural areas (at 91.2%) than in urban areas (at 69.4%) (ILO, 2023[11]). There were only modest gender differences, with 91.6% of women and 89.5% of men in informal employment (ILO, 2023[11]). Informal workers are more likely than employees and employers to experience low job and income security and are less covered by social protection and employment regulation. The formal sector, which comprises only 9.5% of employment, is dominated by public administration and community, social and other services (48.4% of formal employment) (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9. The informal economy employs a majority of the population in Lao PDR, mainly within the agricultural sector

Contribution of different sectors to the total amount of informal and formal employment in Lao PDR (2022)

Source: (ILO, 2023[11]), “ILO modelled estimates”, ILOSTAT (database), https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on 29 January 2024).

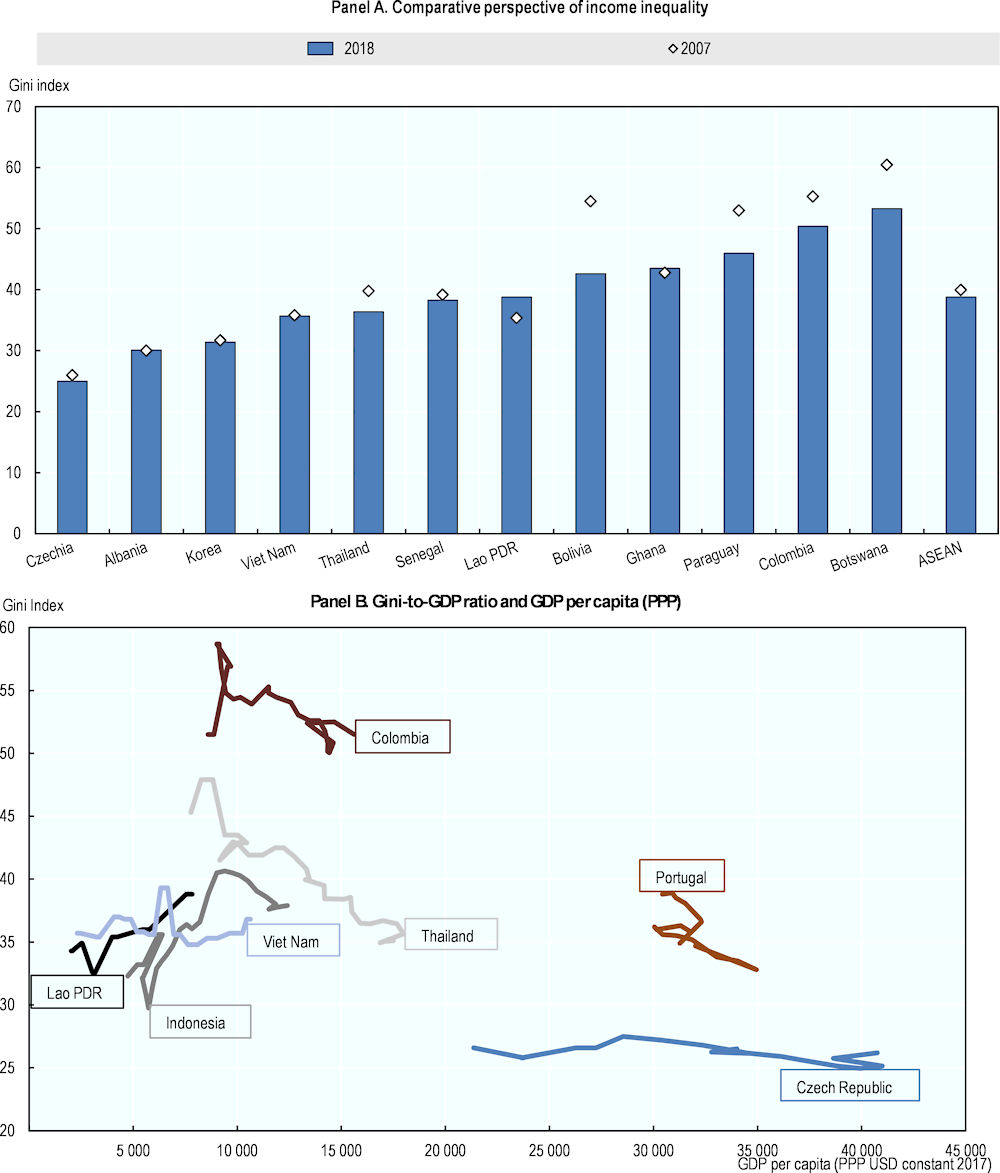

The unequal distribution of opportunities is reflected in increasing inequality. Lao PDR’s remarkable economic growth has mainly been attributed to capital-intensive sectors, such as mining and energy, which have created limited employment opportunities. This has left household incomes growing significantly slower than the rest of the economy, especially at the lower end of the income distribution. Instead, growth has been more favourable at the top end of the income distribution, and inequality continues to rise. The Gini index for Lao PDR increased from 35.4 in 2007 to 38.8 in 2018 (Figure 2.10, Panel A). While Lao PDR follows the upward-sloping Gini-to-GDP per capita trajectory of its neighbours, much lower levels of inequality are possible (Figure 2.10, Panel B).

Figure 2.10. Income inequality is increasing in Lao PDR

Note: Panel A: Data for Albania are from 2008 instead of 2007; data for Botswana are from 2009 and 2015 instead of 2007 and 2018; data for Colombia are from 2009 instead of 2007; data for Ghana are from 2005 and 2016 instead of 2007 and 2018; data for Korea are from 2006 and 2016 instead of 2007 and 2018; data for Senegal are from 2005 instead of 2007; and data for Viet Nam are from 2006 instead of 2007. For the ASEAN average, data are missing for Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia and Singapore. Data for Malaysia and the Philippines are from 2006 instead of 2007. Panel B shows Gini-to-GDP ratio and GDP per capita paths between 2001 and 2021. The Gini-to-GDP ratio is calculated as the Gini coefficient divided by GDP (constant 2017 USD).

Source: Panel A: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database) https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 29 March 2024) Panel B: Authors’ compilation based on World Bank (2024[1]).

A thriving private sector that promotes employment and productivity across multiple sectors would be key to achieving more broad-based economic growth

A level playing field and supportive conditions could help enterprises grow and become formal. The Lao PDR economy’s current profile of high informality and limited productivity in most sectors (Figure 2.6) reflects a lack of opportunity for private enterprises to grow and create innovation and opportunity for Laotians. Informal enterprises exhibit significantly lower productivity compared with their formal counterparts, with only 13% of the sales per worker of a formal firm (World Bank, 2019[16]). Yet, many enterprises remain informal, often as a result of the multiple obstacles to formalisation. A level playing field that offers the same conditions and rules of engagement to all economic actors, no matter their background and size, is key to allowing for more formalisation.

Reflecting Lao PDR’s level of development and its concentrated economic structure, the vast majority of firms are micro-businesses. These account for 94.2% of all enterprises in the country (126 168 micro-businesses). In addition, small enterprises (5‑19 employees) account for 4.9% of all enterprises (6 600 small enterprises), medium-sized enterprises (20‑99 employees) account for 0.7% (954 medium enterprises), and large enterprises (more than 100 employees) account for 0.2% (276 large enterprises), according to the latest Economic Census survey III (2019‑20) (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2020[17]).

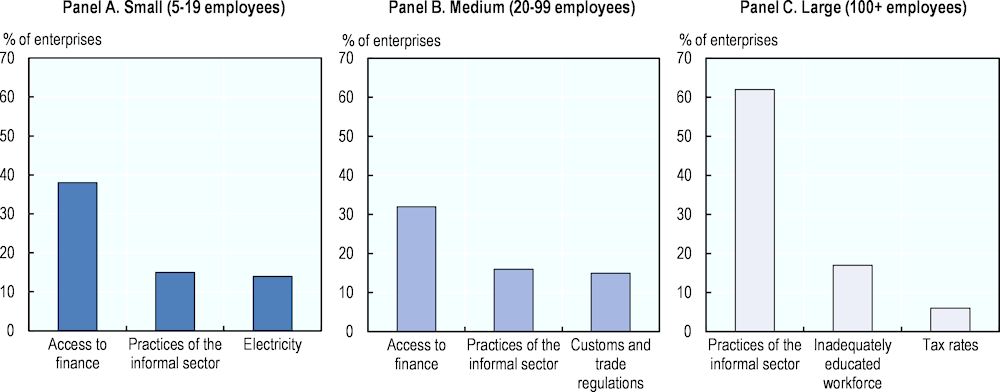

Access to finance is a key obstacle for small and medium-sized enterprises in the formal sector (Figure 2.11). Only 49.3% of small enterprises have a checking or savings account, and only 20.1% have a bank loan/line of credit (World Bank, 2019[16]). Consequently, internal company financing (89%) largely dominates sources of finance, followed by bank financing (6%) and equity (3%). A more open and competitive financial sector would be a key requirement in order to advance private sector development. Currently, most banks in Lao PDR are state-owned or are joint ventures with public shareholders. Chapter 3 provides recommendations for financing sustainable development.

Figure 2.11. Access to finance is a key constraint for small- and medium-sized enterprises in the formal sector

Top three business constraints in the private formal non-agricultural sector, by enterprise size

Source: (World Bank, 2019[16]), Lao PDR 2018 Country Profile, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/content/dam/enterprisesurveys/documents/country-profiles/Lao-Pdr-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

As firms grow larger in size, the availability of human capital becomes a binding constraint (Figure 2.11). Private investors in Lao PDR experience shortages in technical and vocational workers (such as mechanics; maintenance workers for heavy machinery; technicians and technical workers for dam maintenance; construction workers; and nurses), as well as a lack of engineers. Soft skills such as reliability, timeliness, work ethic and a willingness to work can be difficult to find for investors as well.

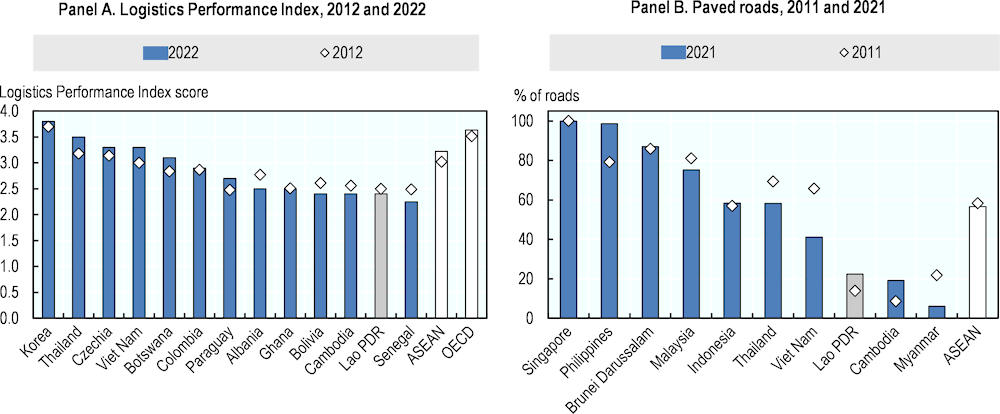

For the agricultural sector, export-based manufacturers and the tourism sector, high transportation costs remain a challenge. Significant progress on the construction of important highway and train routes has been made in recent years. Nevertheless, the road network in Lao PDR remains limited, and many areas of the country are difficult to access (Figure 2.12). Transportation costs along important trade corridors are between 1.4 and 2.2 times higher in Lao PDR than in Thailand (IDE-JETRO, 2017[18]).

Figure 2.12. Lao PDR performs worse than comparators in the Southeast Asia region and elsewhere in the world in terms of road transportation infrastructure and logistics

Note: Panel A: Senegal data are from 2018 instead of 2022. Panel B: Indonesia, Lao PDR and Myanmar data are from 2020 instead of 2021; Viet Nam data are from 2017 instead of 2021.

Source: Panel A: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Data accessed on 23 November 2023; Panel B: (ASEAN, 2023[19]), ASEANstats, https://www.aseanstats.org/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

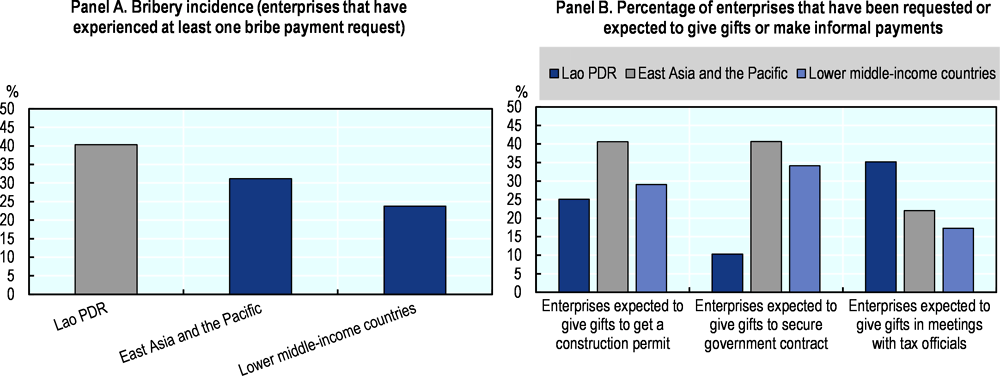

Furthermore, the prevalence of bribery in Lao PDR adds another layer of complexity to the business environment. Forty percent of enterprises in the private formal non-agricultural sector have reported encountering at least one instance of a bribe payment request across various transactions, encompassing tasks such as paying taxes, acquiring permits or licences, and securing utility connections. This figure exceeds the corresponding percentages in both the East Asia and the Pacific region (31%) and the average of lower middle-income countries (21%). Notably, bribery rates are the highest for engagements with tax officials (Figure 2.13). Chapter 5 provides a more detailed analysis of the constraints to private sector development and sustainable investment in Lao PDR, and provides recommendations to increase this investment.

Figure 2.13. There is a significant prevalence of bribery in the private formal non-agricultural sector in Lao PDR

Source: (World Bank, 2019[16]), Lao PDR 2018 Country Profile, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/content/dam/enterprisesurveys/documents/country-profiles/Lao-Pdr-2018.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

People: Making human capital development a priority

In order to ensure that no one is left behind in Lao PDR’s continued development, inequality and poverty need to be addressed

Lao PDR has been able to translate its economic growth into important development gains in household income, poverty reduction, education and healthcare. Extreme poverty fell from 25.4% to 7.1% between 2002 and 2018, and poverty at the national poverty threshold fell from 46.0% to 18.3% between 1992‑93 and 2018‑19 (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2022[20]). Multi-dimensional poverty (which has been officially recognised by the government of Lao PDR and takes into account deprivation in healthcare, education, water and sanitation, housing, and access to information) has also declined, especially in rural areas, mirroring the decline in monetary poverty (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2020[21]; OPHI, 2023[22]). Lao PDR has made steady progress in expanding access to education and achieving nearly universal primary education, making primary school compulsory and free up to and including the fifth grade. Progress in health outcomes has been equally significant. Maternal mortality dropped from 284 deaths per 100 000 births in 2010 to 126 deaths per 100 000 births in 2020, and the mortality rate for children aged under 5 years improved from 61 deaths per 1 000 births in 2010 to 44 deaths per 1 000 births in 2020 (World Bank, 2024[1]).

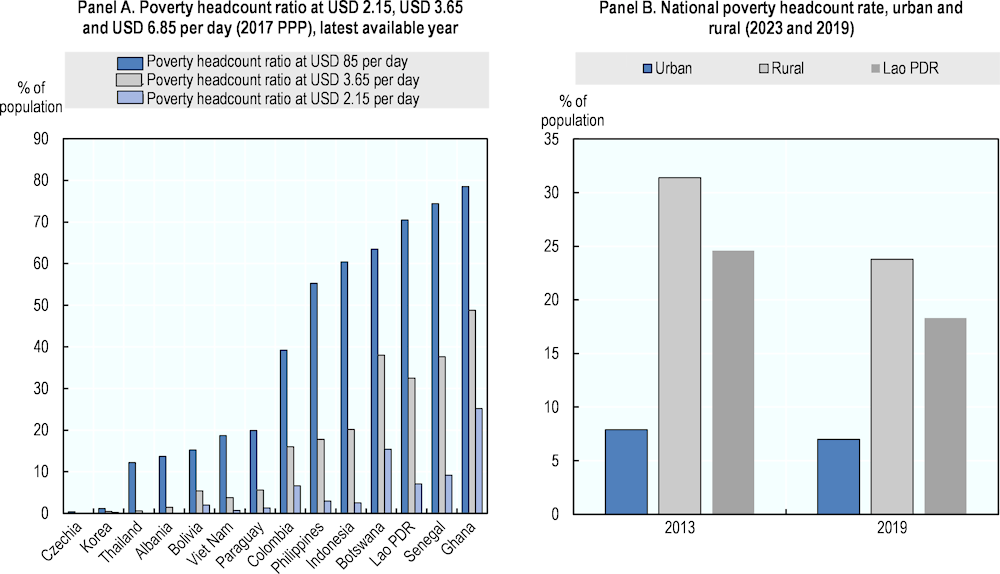

Nevertheless, poverty remains a challenge, especially in rural areas. Despite progress in reducing poverty, poverty levels remain high, especially for the higher poverty measures (i.e. the share of the population living on less than USD 3.65 and USD 6.85 per day) (Figure 2.14, Panel A). In 2018, 32.5% of the population lived on incomes of less than USD 3.65 per day and 70.5% lived on incomes lower than USD 6.85 per day (World Bank, 2023[23]). Despite rapid poverty reduction in rural areas, a majority of those living in poverty live in rural areas, and significant gaps between the poverty rates in urban and rural areas remain. The rural poverty rate dropped by 7.6 percentage points between 2013 and 2019 (to 23.8%), while urban poverty has stagnated (Figure 2.14, Panel B). Some segments of society are experiencing new poverty prompted by landlessness and dispossession as a result of investment projects, concessions and other factors (Ingalls, 2018[24]). Provinces in both the north and south of Lao PDR have experienced a rapid reduction in poverty, but discrepancies persist across regions. Poverty reduction has stagnated in central Lao PDR, which has historically been the country’s wealthiest region (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2020[21]).

Figure 2.14. The poverty rate in Lao PDR remains a challenge

Note: Panel A: Latest data available: Botswana (data from 2015); Korea and Ghana (data from 2016); Lao PDR and Senegal (data from 2018); Albania, Czechia and Viet Nam (data from 2020); and Paraguay (data from 2022).

Source: Panel A: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Panel B: (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2020[21]), Poverty in Lao PDR, Key Findings from the Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey, 2018-2019, https://data.laos.opendevelopmentmekong.net/en/dataset/182169a3-6f97-4ade-81fb-755267a9c54e/resource/ffcc354f-a036-46f2-af9b-710ff47b5213/download/poverty-profile_eng-editing-23.7.2020-1.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

Vulnerable groups are at risk of being left behind. Despite the poverty reduction that has occurred in recent years, poverty remains high among minority ethnic groups. Out of the three largest ethnic minority groups in Lao PDR – the Mon-Khmer (which comprise 22% of the population), the Hmong-lu Mien (9% of the population) and the Chine-Tibet (3% of the population) – the Hmong-lu Mien has the highest poverty rate. This group constitutes 19% of those living in poverty despite making up only 9% of the population (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2020[21]; Lao Statistics Bureau, 2016[25]). The widening disparities among ethnic groups have multiple causes, including differences in household human and physical assets and economic opportunities, as well as high fertility rates and low school progression (Pimhidzai and Houng Vu, 2017[26]).

Human capital development presents a pressing development need for which funding capacity must be strengthened

A more balanced growth path would increasingly rely on human capital. The current trajectory of capital-intensive investments in natural resource extraction and energy generation only required relatively limited amounts of skilled labour. Accordingly, the employment effect of these sectors has been small. Other sectors, however, like manufacturing, agri-business, tourism and most services, will need larger numbers of qualified labourers. Beyond education and skills, human capital also requires adequate healthcare and a minimum level of social services.

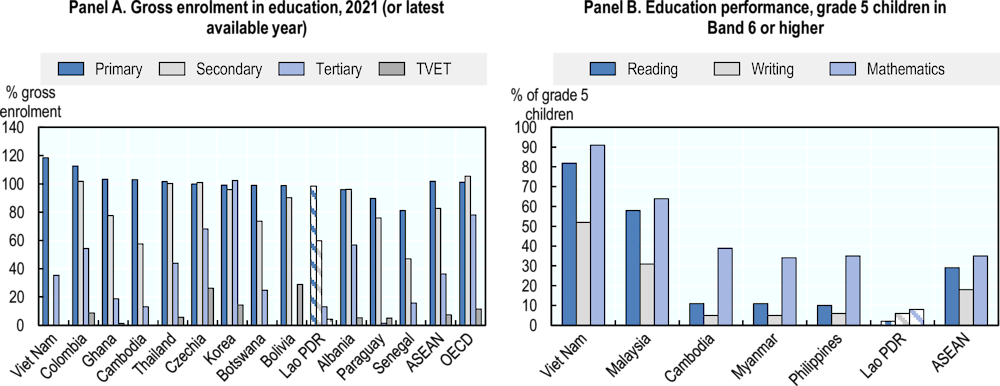

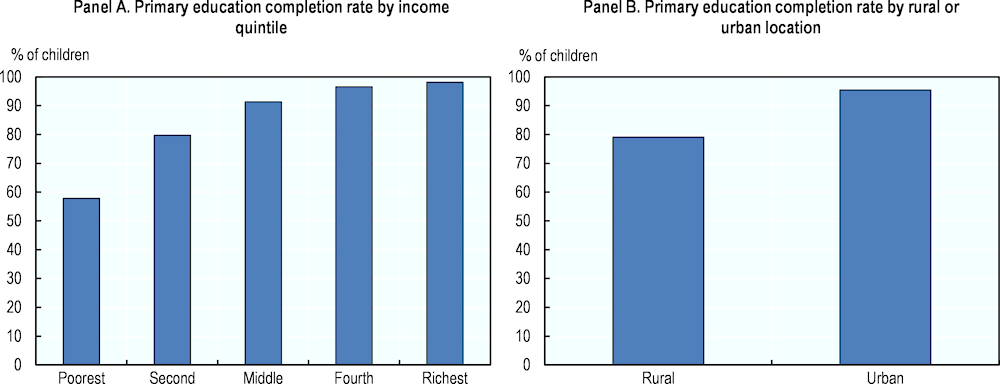

Despite significant past success, the current outlook on education and skills is challenging. Lao PDR has made steady progress in expanding access to education and achieving nearly universal primary education in the last decade, making primary school compulsory and free up to and including the fifth grade. Despite this significant progress in expanding access to primary and secondary education, enrolment levels have started to decline and the dropout rate remains high, particularly for the rural population (Figure 2.15). Only 79% of the rural population in Lao PDR has completed primary education. The completion rate for the poorest quintile of the population also remains low, at 58% (Figure 2.15) (UNICEF, 2022[27]).

The quality of education is also of concern. Student performance on standardised tests in Lao PDR is among the lowest in the Southeast Asia region (Figure 2.15, Panel B). Students’ learning outcomes are low, leaving children without essential knowledge and skills. Teachers’ limited capacity, a weak pedagogical support system, challenges in multi-grade teaching, and the lack of teaching/learning materials are some of the key constraints resulting in the low quality of education in Lao PDR. As a result, job prospects for graduates are limited. These limited job prospects do not incentivise student enrolment at school. This is reflected in low enrolment rates above the primary level: enrolment in secondary and tertiary education and in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in Lao PDR are lower than in comparators in the Southeast Asia region (World Bank, 2024[1]).

Figure 2.15. Despite progress in enrolment in education, Lao PDR lags behind its peers in terms of secondary education enrolment and in terms of the quality of education

Note: Panel A: Latest data available: Thailand (2022 instead of 2021); Bolivia, Colombia, Czechia, Ghana and OECD (2020 instead of 2021). Primary enrolment: Paraguay (2015 instead of 2021). Secondary enrolment: Paraguay (2012 instead of 2021). Tertiary enrolment: Paraguay (2013 instead of 2021). TVET indicates enrolment in vocational education among 15‑24-year-olds. Panel B: The performance of grade 5 children is evaluated in six bands for reading, in eight bands for writing and in nine bands for mathematics.

Source: Panel A: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Panel B: (UNICEF/SEAMEO, 2020[28]), SEA-PLM 2019 Main Regional Report, Children’s learning in 6 Southeast Asian countries, https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/7356/file/SEA-PLM%202019%20Main%20Regional%20Report.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

Figure 2.16. The education completion rate in Lao PDR is low among the poorest and rural populations

Percentage of the total number of children who are 3 to 5 years older than the intended age for the last grade of primary education (11 years old for Lao PDR).

Source: (UNICEF, 2023[29]), MICS2017, https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/overview/#data (accessed on 20 November 2023).

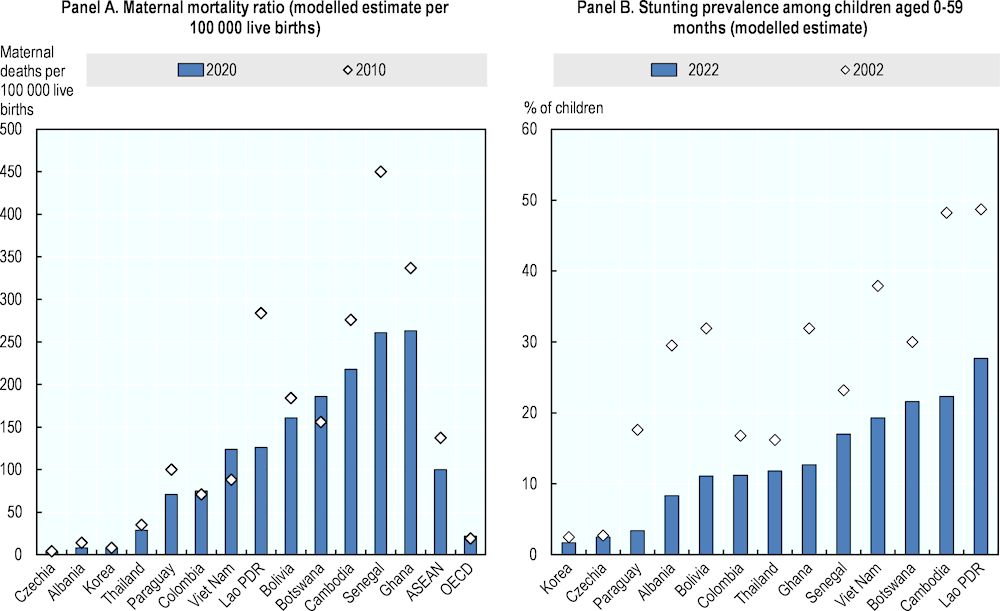

There has been remarkable progress in health outcomes, but maternal and child health remains a pressing issue. Further improving the quality of and access to healthcare remain priorities for sustainable development and for a human capital strategy. Maternal mortality in particular remains high in Lao PDR compared with the international average, notwithstanding significant progress the country has made (Figure 2.17, Panel A). Nutrition and food security remains a persistent problem, especially among low-income families in rural areas (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2020[30]). The prevalence of stunting due to chronic malnutrition among children aged under five years is high, at 27.7% in 2022 (UNICEF/WHO/World Bank, 2023[31]) (Figure 2.17, Panel B). Income and geographic inequalities in health service utilisation are further challenges reflecting the unequal access to health services (UNFPA, 2021[32]). While the government of Lao PDR has introduced a national free maternal and child health service policy, other barriers exist in terms of access to health services, especially for the poorer quintiles of the population. In addition to barriers to the physical accessibility of health services, ethnolinguistic barriers, cultural barriers and poor education are reported (World Bank, 2020[33]).

Figure 2.17. Lao PDR has made significant progress in health outcomes, but child and maternal health continues to be a pressing issue

Source: Panel A: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators; Panel B: (UNICEF/WHO/World Bank, 2023[31]), Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates Database, https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/malnutrition/ (accessed on 15 November 2023).

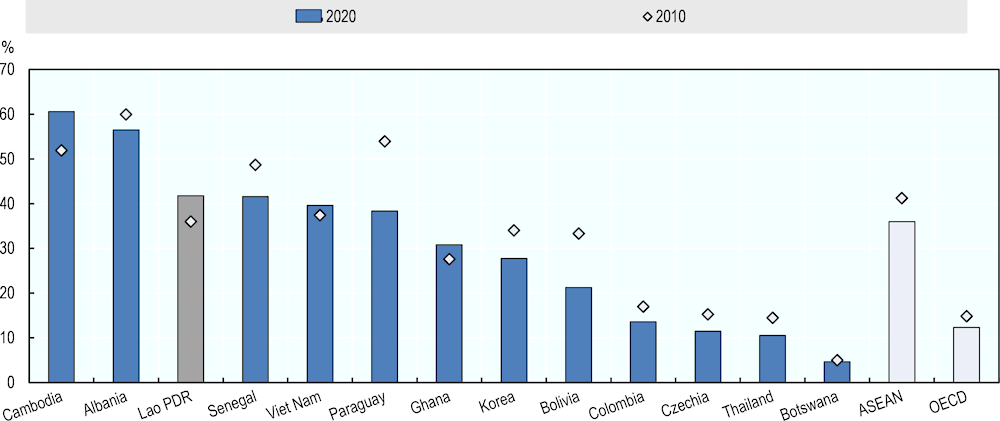

There has been significant health insurance expansion, but patients in Lao PDR spend more on healthcare in comparison with other countries. Lao PDR has a National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme that is funded by tax revenues and that provides social health protection to the population with a small co-payment at the point of care. Since its introduction in 2016, the NHI has drastically increased the number of people with health insurance coverage from 45% in 2016 to 94% in 2021, and has increased the use of public health services by 10‑30% (WHO, 2022[34]). However, challenges remain in ensuring complete or proper availability of NHI benefits. Some people are required to pay additional or excessive fees, while a range of other operational challenges affect the delivery and sustainability of the scheme. As a result, Lao PDR is one of the countries where out-of-pocket (OOP) healthcare expenditure has risen between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 2.18). High OOP healthcare expenditure has larger impacts on more vulnerable populations, as data from the most recent Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey, 2018‑2019 show that the poorest quintile of the population is less likely to seek healthcare due to financial barriers than the richest quintile of the population: 14.4% of the poorest quintile reported not seeking healthcare for financial reasons compared with 6.8% of the richest quintile (WHO, 2023[35]). Regional disparities have also been noted: people living in Vientiane (the capital of Lao PDR) reported paying more than double the amount in OOP payments compared with those living in other regions, and they experienced higher overall healthcare expenditure compared with those living in other regions (WHO, 2023[35]).

Figure 2.18. Patients spend more on healthcare in Lao PDR despite the expansion of health insurance coverage

OOP healthcare expenditure (percentage of total healthcare expenditure)

Note: Data for Albania are from 2018 instead of 2020.

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 15 November 2023).

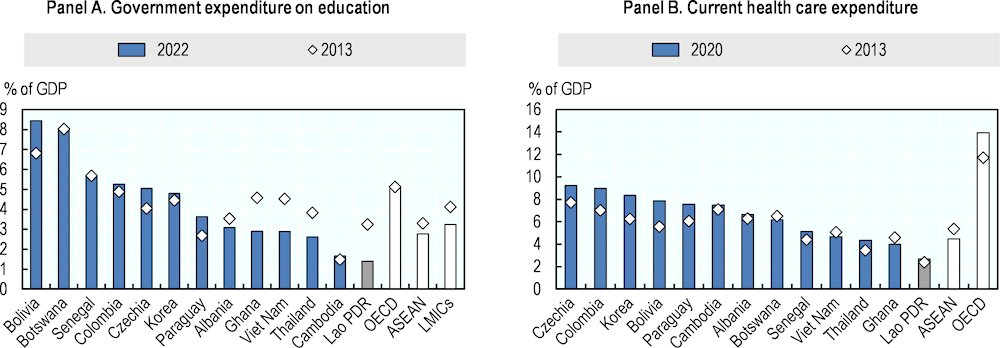

There is a lack of funding in the social sectors. Lao PDR’s limited fiscal space has constrained the government’s ability to expand spending on education, healthcare and social protection. Although health spending per capita has almost quadrupled since the year 2000, the country’s total spending on education, healthcare and social assistance as a share of GDP is low compared with its regional and income peers and is below international benchmarks (Figure 2.19) (World Bank, 2024[1]). Article 60 of the Education Law (2015) states that 18% of the national budget should go to education, but the latest figures reveal that actual budgetary allocation to education has remained low and in fact decreased from 15.8% in 2015‑16 to 13.1% in 2020‑21 (Government of Lao PDR, 2015[36]; UNICEF, 2021[37]). The financing gap has led to the cancellation of key teacher in-service training programmes, limited essential funding to district bureaus and schools, and stalled national investment in the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Education (WASH) in Schools programme (UNICEF, 2021[37]).

Figure 2.19. There is limited government expenditure on education and healthcare in Lao PDR

Note: Panel B: Data for Albania are from 2018 instead of 2020.

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 23 November 2023).

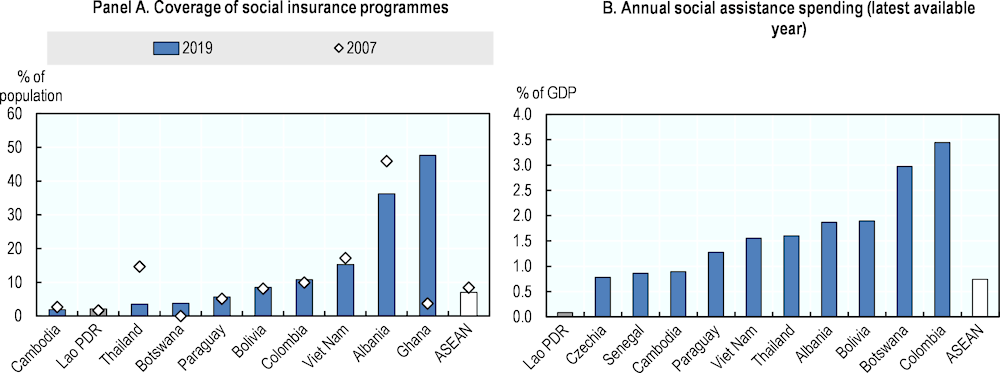

In addition, the social protection system has a low level of coverage. The total coverage of social protection is low (covering 2.1% of the population), as is spending, with 0.09% of GDP being spent on social assistance (Figure 2.20). This includes most public sector workers, slightly less than one-half of all workers in formal enterprises, and 24 000 self-employed workers (ILO, 2023[38]). Most of these workers are more likely than employees and employers to experience low job and income security, as well as less covered by social protection and employment regulation.

Figure 2.20. Coverage and spending on social protection are limited in Lao PDR compared with other countries around the world

Note: Panel A: No data were available for Czechia, Korea, Senegal and or OECD members member countries. Average for ASEAN Member States: data for the Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam are from 2006 instead of 2007, and data for Cambodia and Malaysia are from 2008 instead of 2007. Data for Cambodia are from 2013 instead of 2019, data for the Philippines are from 2017 instead of 2019 and data for Lao PDR are from 2018 instead of 2019. No data were available for Brunei Darussalam. Panel B: Social assistance expenditure refers to spending on benefits and administrative costs. Annual social assistance expenditure is calculated by aggregating programme-level social assistance data for the most recent available year during the period 2015‑21. Average for ASEAN Member States: data for Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines and Singapore are from 2015; data for Indonesia and Viet Nam are from 2016; data for Thailand are from 2018; and data for Lao PDR are from 2021. No data were available for Brunei Darussalam or OECD member countries. Data for Albania from 2018-2020, Bolivia 2015, Botswana 2018-2019, Colombia 2015-2020, Czechia 2016-17, Paraguay 2016-2017Senegal 2015.

Source: Panel A: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Panel B: (World Bank, 2023[39]), World Bank ASPIRE (database), https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/datatopics/aspire (accessed on 23 November 2023).

There are high rates of migration to neighbouring countries, but low levels of remittances

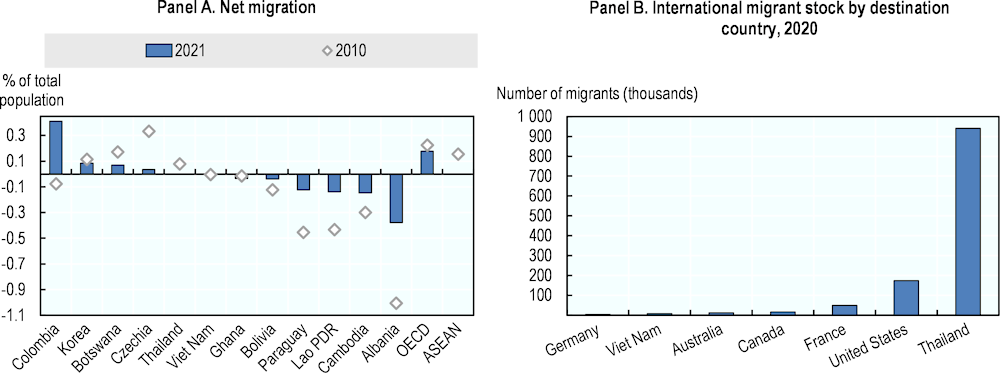

The migration rate from Lao PDR to neighbouring countries is high. Many skilled and unskilled workers in Lao PDR who are willing to work in a factory environment emigrate to neighbouring countries (primarily Thailand (Figure 2.21, Panel B)), where demand for low-skilled labour in sectors such as infrastructure, services, manufacturing and agriculture is high and minimum wages largely exceed those in Lao PDR. Although data for international migration are limited, estimates vary to a great extent, from 850 000 to 2.5 million (UNFPA, 2021[32]), and the net migration rate in relation to the population remains high in comparison with peer countries (Figure 2.21, Panel A). Laotian women are more likely to migrate abroad than men, with nearly 56% of Laotian migrants being women according to UN data (UNDESA, 2020[40]). Young women are more likely to leave rural provinces, moving out of agricultural communities into cities or to Thailand in search of employment (Ingalls, 2018[24]).

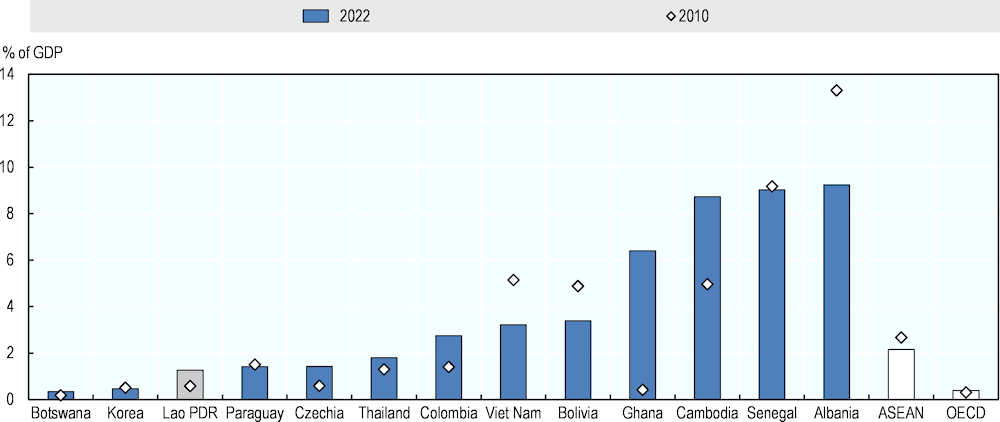

Figures on personal remittances may underestimate their true effect on household livelihoods. The share of remittances in relation to GDP in Lao PDR (1.26% of GDP in 2022) appears relatively modest when compared with those of other countries (Figure 2.22). This suggests that a significant portion of house’holds do not heavily rely on remittances as their primary source of income. Around 9% of households in Lao PDR receive remittances from abroad, and these remittances constitute 60% of their overall household income (IOM, 2022[41]). However, informal remittances may play a considerable role in household income, potentially accounting for up to 50% of total remittance transfers in the GMS. Consequently, national and official figures may underestimate the true impact of remittances on the macroeconomic level and on household livelihoods in Lao PDR (Asian Development Bank, 2013[42]).

Figure 2.21. Lao PDR has a high migration rate

Source: Panel A: Authors’ calculations based on (World Bank, 2024[1]) World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Panel B: (UNDESA, 2020[40]), International Migrant Stock (database), https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock.

Figure 2.22. Personal remittances are low in Lao PDR

Personal remittances received (2010 and 2022)

Note: The ASEAN average was computed by OECD staff, but due to the absence of data for Brunei Darussalam and Singapore in 2010 and for Singapore in 2022, these countries were excluded from the average calculations.

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Planet: Preserving Lao PDR’s abundant natural wealth and fighting air pollution

Lao PDR benefits from abundant natural endowments, but these have come under pressure

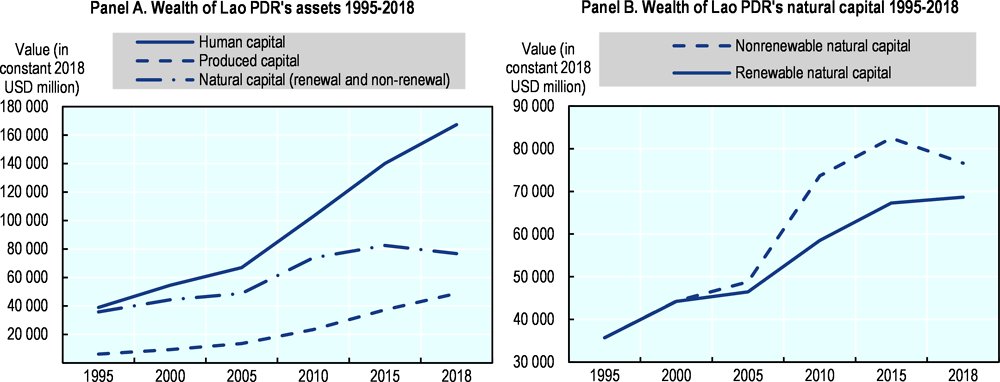

Lao PDR has an abundance of natural resources, namely water, mineral deposits and forests that cover the entire length of the country and serve important functions within the ecosystem. Lao PDR has one of the highest levels of forest cover in Southeast Asia. Its evergreen forests, karst landscape and mountainous forests have made Lao PDR one of the ten most important biodiversity ecoregions globally, with ongoing discoveries of new species (World Bank, 2020[43]). Forest resources are also crucial for economic development and individuals’ livelihoods in Lao PDR. Forestry rents contributed 1.5% to the country’s GDP in 2021 (World Bank, 2024[1]). Forests store carbon, help protect communities and infrastructure from the impacts of drought and flash floods, and contribute to the supply of clean water and food. In addition, forests provide invaluable non-timber forest products, such as food, materials used in construction and trade, and medicine, and are also a source of subsistence income in rural areas. Lao PDR’s terrain is also rich in mineral resources. With more than 570 mineral deposits identified in the country, including deposits of gold, copper, zinc and lead, Lao PDR was ranked as one of the most resource-rich countries in Asia in 2008 (Houngaloune, 2019[44]). In addition, Lao PDR’s water resources from surface and groundwater flows provide the country with irrigation, fisheries, plantations, livestock and hydropower potential.

Figure 2.23. Lao PDR’s natural assets are declining

Note: “Natural capital” refers to renewable natural capital (including forest timber, forest ecosystem services, mangroves, fisheries, protected areas, and crop and pasture land) and non-renewable natural capital (including oil, gas, coal, metals and minerals).

Source: (World Bank, 2021[45]), The Changing Wealth of Nations 2021: Managing Assets for the Future, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/wealth-accounting (accessed on 23 November 2023).

However, the current economic growth model has put the environment in Lao PDR under pressure. Lao PDR’s rich natural resources – including minerals, hydropower and its diverse ecosystem – have contributed to the country’s wealth and development in important sectors such as agriculture and tourism, providing jobs for more than 78% of its population (IFAD, 2018[46]). However, the current economic growth model has placed the environment under increasing pressure. While Lao PDR’s wealth of human capital has increased over time, its wealth of natural capital has started to decline, mainly due to a decrease in the amount of non-renewable capital such as metals and minerals (Figure 2.23). Research suggests that in recent decades, forest loss and degradation have cost the country nearly 3% of its GDP per year, and that the health effects caused by pollution have an estimated annual cost equivalent to 15% of Lao PDR’s GDP (World Bank, 2021[47]).

Lao PDR is home to important biodiversity, which needs protection. Of the 1 298 globally threatened species in the Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot (consisting of Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam, as well as some southern parts of the People’s Republic of China [hereafter “China”]), 281 (22%) are found in Lao PDR (Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, 2020[48]). Forests, grasslands and other terrestrial habitats are being degraded, fragmented and lost as a result of the expansion of industrial agriculture and commercial timber extraction (World Bank, 2020[43]).These habitats are home to many rare and endangered species. In addition, the recent surge in investment (both domestic and foreign) in mining and hydropower activities is resulting in negative effects on biodiversity, as these activities are often being undertaken in protected areas. Biodiversity is further threatened by land conversion, urban development, climate change and pollution. In addition, commercial tree plantations can also be a threat to biodiversity as they risk reduce the diversity of plants and habitants of numerous species.

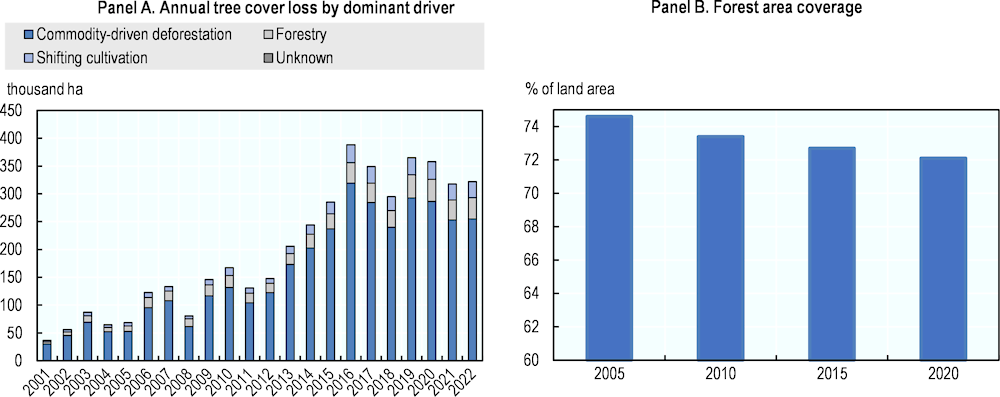

Deforestation, which is influenced by both legal and illegal economic activity, is a major challenge. Lao PDR has one of the highest levels of forest cover in Southeast Asia. An estimated 80% of the population are heavily reliant on forests for their well-being (UNEP GRID, 2023[49]). However, a combination of illegal logging, infrastructure development (such as hydropower, mining and roads) and the conversion of forests to agricultural land has caused forest loss. From 2001 to 2022, Lao PDR lost 4 370 000 ha of tree cover, which is equivalent to a 23% decrease (Global Forest Watch, 2023[50]) (Figure 2.24). Commercial agricultural expansion (commodity-driven deforestation) is the dominant driver of deforestation in Lao PDR (Figure 2.24, Panel A). Shifting agriculture (also called slash-and-burn agriculture) is another major driver of forest degradation in Lao PDR. This is a farming practice where farmers clear and burn forests in order to create ash-fertilised soil. Crops are then planted and harvested for one or two years in succession, after which the plot is abandoned and the practice is repeated in an adjacent patch of forest (Chen et al., 2023[51]).

Figure 2.24. The dominant drivers of deforestation in Lao PDR are linked to commercial agricultural expansion

Note: Panel A: The methods used to collect these data have changed over time, especially after 2015. “Commodity-driven deforestation” refers to large-scale deforestation linked primarily to commercial agricultural expansion. “Shifting agriculture” refers to the temporary loss of forest cover or permanent deforestation due to small- and medium-scale agriculture. “Forestry” refers to the temporary loss of forest cover from plantation and natural forest harvesting, with some deforestation of primary forests. The commodity-driven deforestation category represents permanent deforestation, while tree cover affected by the other categories often regrows. The dataset does not indicate the stability or condition of land cover after the tree cover loss occurs.

Source: Panel A: (Global Forest Watch, 2023[52]), Tree Cover Loss by Dominant Driver, www.globalforestwatch.org. Panel B: (FAO and UNEP, 2020[53]), The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people, https://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/en/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

Air pollution is a significant challenge

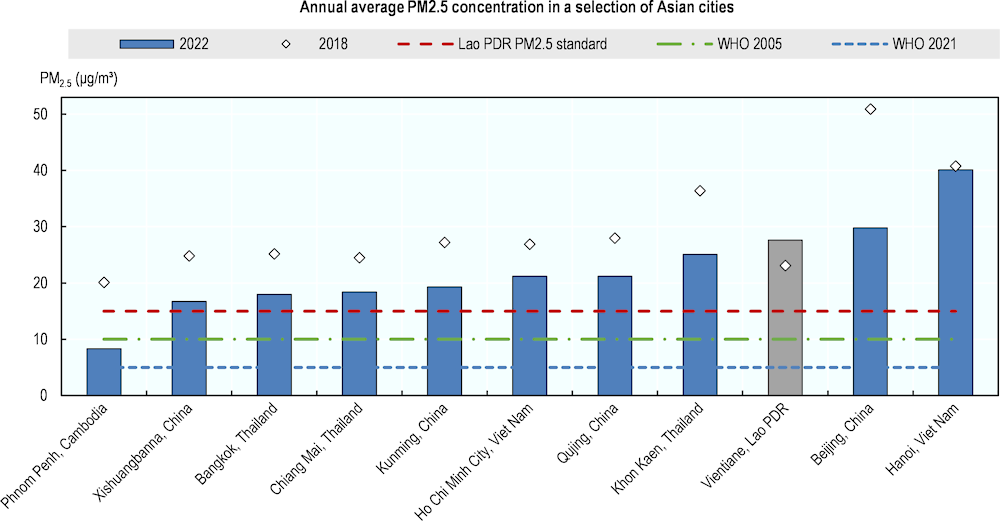

Air pollution presents a serious threat to well-being. Lao PDR was ranked 149th out of 180 countries in the 2022 Yale Environmental Performance Index, and was among the worst-performing countries for air pollution (Wolf et al., 2022[54]). Particulate matter, and especially particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 microns or smaller (PM2.5), is the outdoor ambient air pollutant that is associated with the largest quantity of negative health effects globally. Chronic exposure to PM2.5 considerably increases health risks, and the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in particular (OECD, 2024[55]). Although seasonal variations persist, monitored annual average PM2.5 concentrations for Lao PDR for 2018 and 2022 significantly exceeded national and international air quality standards (Figure 2.25). A recent World Bank study estimated that environmental pollution contributed to 10 000 deaths in Lao PDR in 2017 (22% of all deaths in Lao PDR), and 27% of these deaths were from ambient air pollution. The cost of health effects from ambient air pollution in 2017 amounted to 3.5% of Lao PDR’s GDP (World Bank, 2021[47]). Consequently, the burden of disease from ambient air pollution remains high (see Chapter 1 for further details).

Figure 2.25. Lao PDR has a high concentration of air pollution in comparison with other countries in Southeast Asia

Note: Data for Vientiane (Lao PDR) and Khon Kaen (Thailand) are from 2019 instead of 2018. The horizontal red line indicates the annual mean Lao PDR PM2.5 air quality standard of 15 microgrammes per cubic metre (μg/m3). The horizontal green line indicates the World Health Organization (WHO)’s 2005 PM2.5 air quality guideline of 10 μg/m3. The horizontal blue line indicates the recently revised WHO 2021 PM2.5 air quality guideline of 5 μg/m3.

Source: (IQAir, 2024[56]), World’s most polluted countries and regions, https://www.iqair.com/us/world-most-polluted-countries (accessed on 9 November 2023).

Burning wood and fuel oil plays a significant role in emitting atmospheric pollution. Lao PDR is affected by transboundary emissions from its neighbouring high-pollution countries of Cambodia, China, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam, especially during the dry season (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, 2020[57]). The use of fire in order to clear land for agricultural purposes (so-called slash-and-burn practices) also plays a significant role in emitting atmospheric pollution. In addition, inadequate solid waste management practices, such as open dumping and the burning of waste, also contribute to air pollution (FAO, 2023[58]). Although Lao PDR’s per capita waste generation rate is among the lowest in the Southeast Asia region, waste generation has doubled in Vientiane over the last decade and is expected to increase by another 46% by 2050 (World Bank, 2021[47]). The ban on burning garbage in Vientiane in December 2019 and the establishment of a hotline to report offences might reduce environmental damage if fully respected (The Laotian Times, 2019[59]).

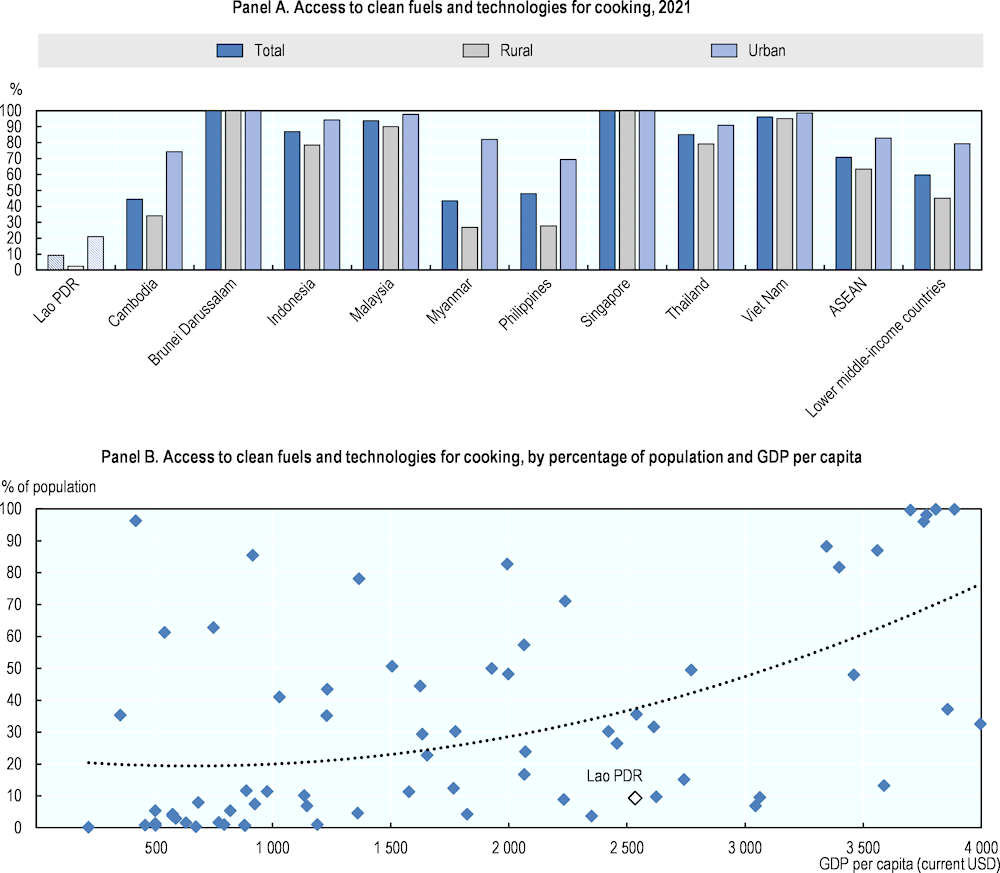

Figure 2.26. Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking across selected countries

Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking (percentage of the population and per capita), 2021

Source: Panel A: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Panel B: Authors’ compilation based on data from (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 23 November 2023).

The use of solid fuels for cooking causes serious household air pollution. In 2021, only 9.3% of the total population in Lao PDR, and 2.4% of the rural population, used clean energies (for example, gaseous fuels, electricity, as well as an aggregation of any other clean fuels like alcohol) as their primary cooking energies. This compares with 60% in other lower middle-income countries, and 71% across ASEAN Member States (Figure 2.26, Panel A). While the use of clean energies increased by nearly 30 percentage points between 2000 and 2021 in the selected countries in Southeast Asia, the increase in Lao PDR over this time period was less than 8 percentage points. The selected countries’ energy use in relation to income level indicates that 35‑45% of the population in Lao PDR would be expected to use clean energies as their primary cooking energies in 2021 based on the country’s per capita income level, rather than the actual level of 9.3% (Figure 2.26, Panel B).

Climate change: Lao PDR’s contribution and vulnerability to climate change is increasing

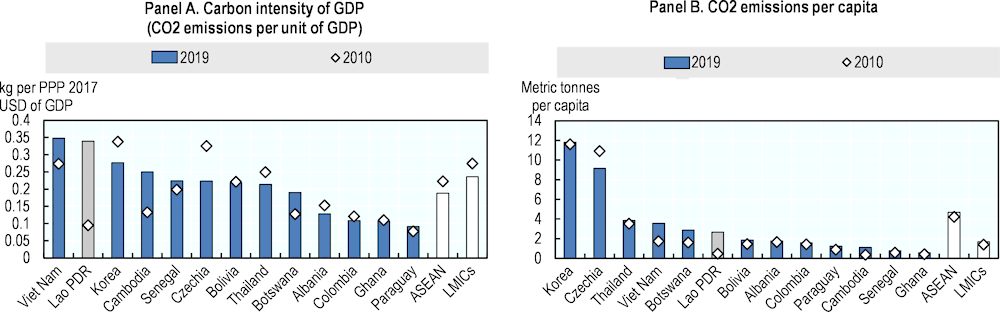

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in Lao PDR are high in relation to the country’s economic output. In relation to economic output, Lao PDR’s 2019 CO2 emissions (0.339 kilogrammes (kg) per 2017 purchasing power parity USD) were among the highest in the Southeast Asia region and were above the average for lower middle-income countries (0.236 kg per 2017 adjusted by Purchasing Power Parity USD) (Figure 2.27, Panel A). Notably, during the period from 2010 to 2019, Lao PDR demonstrated the most significant increase in carbon intensity compared with similar economies (Figure 2.27, Panel A). This surge can be primarily attributed to the commissioning of the 1 878 megawatt lignite-fired thermal plant in Hongsa in 2015, which produces electricity that is predominantly (95%) exported to Thailand. Furthermore, there are additional coal-fired plants in the pipeline – specifically in Xekong, Lamam, Houaphan and Boualapha – which could further elevate Lao PDR’s carbon intensity (Asian Development Bank, 2019[60]). Similarly, per capita CO2 emissions in Lao PDR (2.658 metric tonnes per capita) experienced the most substantial growth between 2010 and 2019 among a selection of comparable countries. Although Lao PDR’s CO2 emissions were aligned with those comparable countries in Southeast Asia in 2019, they remained 59% higher than the average for the lower middle-income country group (Figure 2.27, Panel B).

Figure 2.27. CO2 emissions, both per unit of economic output and per capita, are high in Lao PDR given its level of economic development

CO2 emissions per capita (tonnes) and per unit of GDP (kg per adjusted by Purchasing Power Parity USD 2015)

Source: (World Bank, 2024[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 10 February 2024).

Lao PDR showcases ambitious climate mitigation objectives, as demonstrated by its nationally determined contributions (NDCs), with investment needs estimated at USD 4.8 billion (representing around USD 500 million annually until 2030). In practice, this is far more than the total amount of climate-related development finance currently being accessed by the country, including for both mitigation and adaptation measures (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[61]).

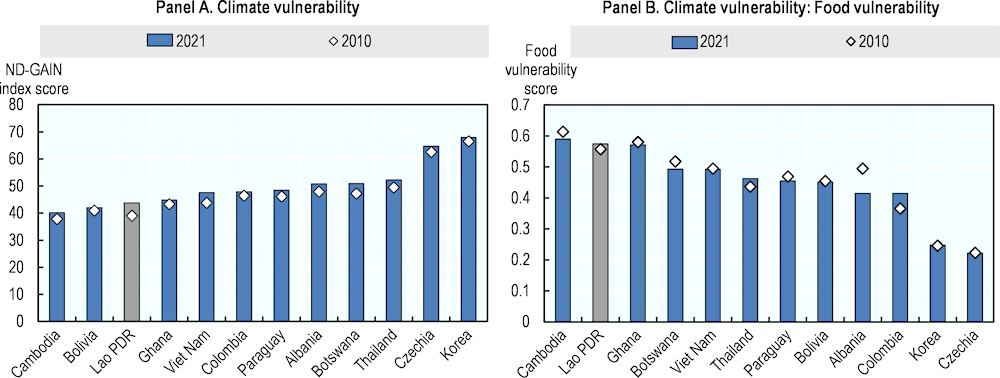

The importance of agriculture and hydropower for the economy make Lao PDR vulnerable to climate change. Lao PDR is vulnerable to natural disasters and extreme weather events, which have been increasing in frequency and intensity (Figure 2.28, Panel A). This vulnerability is further exaggerated by its lack of coping capacity (INFORM, 2022[62]). Almost all of Lao PDR’s farming systems are vulnerable to flooding, drought and the late onset of the rainy season, with a high vulnerability to food security (Figure 2.28, Panel B). With the population’s high level of dependency on traditional agricultural systems and a predominance of smallholder farms, the impacts of natural disasters can be devastating. Floods and droughts continue to be the most significant threats: some provinces experienced flooding every year between 2013 and 2019. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events, resulting in more frequent and more severe flooding in vulnerable and rapidly growing cities along the Mekong River (UNEP GRID Geneva, 2024[63]).

Figure 2.28. Lao PDR is experiencing increased climate vulnerability

Note: Panel A: The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Country Index summarises a country’s vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges in combination with its readiness to improve its resilience. The more vulnerable a country is, the lower its score is, while the more ready a country is to improve its resilience, the higher its score. Panel B: A country’s vulnerability to climate change is assessed through the food score in terms of food production, food demand, nutrition and rural population. Indicators consider the projected change of cereal yields, projected population growth, food import dependency, rural population, agriculture capacity and child malnutrition. The scale spans from 0 to 1, with a lower score corresponding to low vulnerability and a higher score corresponding to high vulnerability in the food sector. The most favourable score achieved throughout the world is 0.11, and the least favourable score is 0.79.

Source: (University of Notre Dame, 2023[64]), Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative, https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/download-data/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

Development priorities

To summarise, this diagnostic chapter identified four strategic pillars that can help Lao PDR build a more sustainable development path:

1. Prosperity: creating the conditions for opportunities to emerge in all sectors and for all citizens

2. People: making human capital development a priority

3. Planet: preserving Lao PDR’s abundant natural wealth, fighting air pollution and mobilising green finance

The 9th NSEDP and other strategies reflect many of these priorities, especially the focus on human capital development.

The remainder of this report focuses on financing as the most binding constraint. Charting a new development path that builds on these three pillars, will require significant amounts of smart investment and reallocation of spending. However, Lao PDR faces a challenging financing landscape and has limited capacity for taxation and revenue generation. Working with all its partners towards a more sustainable structure of its public debt obligations, strengthening revenue generation, and fiscal and debt management, and focusing on investment that is sustainable, are clear priorities at the time of this report.

References

[15] ADB (2021), Developing Agriculture and Tourism for Inclusive growth in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, https://doi.org/10.22617/SGP210337-2.

[19] ASEAN (2023), ASEANstats, https://www.aseanstats.org/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

[60] Asian Development Bank (2019), Lao People’s Democratic Republic Energy Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map, Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines, https://doi.org/10.22617/TCS190567.

[42] Asian Development Bank (2013), Facilitating safe labor migration in the Greater Mekong Subregion: Issues, challenges, and forward-looking interventions, Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong City, Philippines, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/30210/facilitating-safe-labor-migration-gms.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2024).

[4] CDE/University of Bern/MRLG (2019), State of Land in the Mekong Region, Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern, and Mekong Region Land Governance with Bern Open Publishing, https://servir.adpc.net/publications/state-land-mekong-region (accessed on 29 September 2023).

[51] Chen, S. et al. (2023), Monitoring shifting cultivation in Laos with Landsat time series, Remote Sensing of Environment, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2023.113507.

[48] Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (2020), Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot, https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/ep_indoburma_2020_update_final-sm_0.pdf.

[2] Dalavong, S. (2021), “Special Economic Zones in Lao PDR”, https://www.asean.or.jp/ja/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/1-2.SPECIAL_ECONOMIC_ZONES_IN_LAO_PDR.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2023).

[58] FAO (2023), Spatio-temporal dynamics of air pollution and the delineation of hotspots in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/CC4231EN.

[53] FAO and UNEP (2020), The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people, https://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/en/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

[52] Global Forest Watch (2023), “Tree Cover Loss by Dominant Driver”, https://data.globalforestwatch.org/documents/f2b7de1bdde04f7a9034ecb363d71f0e (accessed on 18 January 2024).

[50] Global Forest Watch (2023), Tree cover loss in Lao PDR, http://www.globalforestwatch.org.

[61] Government of Lao PDR (2021), Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), Lao People’s Democratic Republic, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/NDC%202020%20of%20Lao%20PDR%20%28English%29%2C%2009%20April%202021%20%281%29.pdf.

[36] Government of Lao PDR (2015), Education Law (No. 133 of 2015), https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=100539&p_lang=en.

[44] Houngaloune, S. (2019), Trends of gold mining industry in Lao PDR, National University of Laos.

[18] IDE-JETRO (2017), “Logistics Cost in Lao PDR”, https://www.ide.go.jp/library/Japanese/Event/Reports/pdf/20170224_finalreport.pdf.

[46] IFAD (2018), Lao People’s Democratic Republic Country Strategic Opportunities Programme 2018-2024, https://webapps.ifad.org/members/eb/125/docs/EB-2018-125-R-25.pdf?attach=1.

[6] IFC (2021), “Investment Reform Map for Lao PDR - A Foundation for a New Investment Policy and Promotion Strategy Lao PDR”, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/732601621326114842/pdf/Investment-Reform-Map-for-Lao-PDR-A-Foundation-for-a-New-Investment-Policy-and-Promotion-Strategy-Lao-PDR-Investment-Climate-Reform-Project.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2023).

[11] ILO (2023), “ILO modelled estimates”, ILOSTAT (database), International Labour Organization, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).

[38] ILO (2023), Understanding informality and expanding social security coverage in Lao People’s Democratic Republic: A quantitative study of the labour force and enterprise landscape, https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/RessourcePDF.action?id=58027.

[62] INFORM (2022), INFORM Risk Index, INFORM is a collaboration of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Reference Group on Risk, Early Warning and Preparedness and the European Commission. The European Commission Joint Research Centre is the scientific lead of INFORM, https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/inform-index.

[24] Ingalls, M. (2018), State of Land in the Mekong Region, Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern and Mekong Region Land Governance.

[41] IOM (2022), Remittance Landscape in Lao People’s Democratic Republic 2022, International Organization for Migration, Geneva, https://laopdr.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1906/files/documents/Remittance%20Landscape%20in%20Lao%20PDR%202022.07_Eng.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2024).

[56] IQAir (2024), World’s most polluted countries and regions, https://www.iqair.com/us/world-most-polluted-countries (accessed on 9 January 2024).

[13] Lao Statistics Bureau (2022), Statistical Yearbook, Lao Statistics Bureau, https://laosis.lsb.gov.la.

[20] Lao Statistics Bureau (2022), Where are the Poor in Lao PDR? Small Area Estimation: Province and District Level Results, Lao Statistics Bureau, https://laosis.lsb.gov.la/board/BoardList.do;jsessionid=IZsd-s6YrIIl2WArLCAMZwc3W_Fi_LnGQhYxCorO.laosis-web?bbs_bbsid=B404.

[17] Lao Statistics Bureau (2020), Economic Census III, Lao Statistics Bureau, https://laosis.lsb.gov.la/board/BoardList.do?bbs_bbsid=B404 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

[21] Lao Statistics Bureau (2020), Poverty in Lao PDR, Key Findings from the Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey, 2018-2019, Lao Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Planning and Investment, https://data.laos.opendevelopmentmekong.net/en/dataset/182169a3-6f97-4ade-81fb-755267a9c54e/resource/ffcc354f-a036-46f2-af9b-710ff47b5213/download/poverty-profile_eng-editing-23.7.2020-1.pdf.

[30] Lao Statistics Bureau (2020), Poverty Profile in Lao PDR (Poverty Report for the Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey 2018-2019), Ministry of Planning and Investment, https://laosis.lsb.gov.la/board/BoardList.do?bbs_bbsid=B404 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

[25] Lao Statistics Bureau (2016), Results of Population and Housing Census 2015, https://laos.opendevelopmentmekong.net/dataset/?id=4a2c03e0-2402-4691-b2fd-56277fc95c31.

[57] Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (2020), The First Biennial Update Report of Lao PDR, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/The%20First%20Biennial%20Update%20Report-BUR_Lao%20PDR.pdf.

[5] Ngangnouvong, I. (2019), “Mining in Laos, economic growth, and price fluctuation”, https://unctad.org/system/files/non-official-document/MYEM2019_Itthilith_Ngangnouvong_15042019.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2023).

[55] OECD (2024), Air pollution exposure (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/8d9dcc33-en (accessed on 15 January 2024).

[14] OECD (2024), Towards Greener and More Inclusive Societies in Southeast Asia, Development Centre Studies, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/294ce081-en.

[22] OPHI (2023), Global MPI Country Briefing 2023: Lao PDR, https://ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/CB_LAO_2023.pdf.

[26] Pimhidzai, O. and L. Houng Vu (2017), Lao Poverty Policy Brief: Why Are Ethnic Minorities Poor, World Bank group, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/501721505813643980/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

[7] Simoes, A. and C. Hidalgo (2011), “The Economic Complexity Observatory: An Analytical Tool for Understanding the Dynamics of Economic Development”, Workshops at the Twenty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, https://oec.world/en/profile/country/lao?tradeScaleSelector1=tradeScale0&depthSelector1=HS2Depth (accessed on 15 January 2024).

[59] The Laotian Times (2019), Vientiane Officially Bans Burning of Garbage, https://laotiantimes.com/2019/12/27/vientiane-officially-bans-burning-of-garbage/ (accessed on 4 January 2024).

[10] UN Habitat (2023), Country report 2023, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/06/3._lao_pdr._country_report_draft_30may_b5.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

[8] UN Tourism (2024), “Global and regional tourism performance” (database), UN World Tourism Organization, https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 18 January 2024).

[40] UNDESA (2020), International Migrant Stock (database), https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock (accessed on 20 November 2023).

[49] UNEP GRID (2023), Interactive Country Fiches: Lao PDR. Forest, https://dicf.unepgrid.ch/lao-peoples-democratic-republic/forest#section-drivers.

[63] UNEP GRID Geneva (2024), Climate change Lao PDR, UNEP, https://dicf.unepgrid.ch/lao-peoples-democratic-republic/climate-change#section-states.

[32] UNFPA (2021), Demographic change for development Lao people’s democratic republic 2030, https://lao.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/210624_unfpa_demographic_change_for_development_lao_pdr_2030_report.pdf.

[29] UNICEF (2023), “MICS2017”, https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/overview/#data (accessed on 18 January 2024).

[27] UNICEF (2022), UNICEF data, https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/overview/#data.

[37] UNICEF (2021), Public investment in Education Advocacy Brief. Investing more in Education to Boost the Economy, Graduate from Least Developed Country and Mitigate COVID-19 Impact, https://www.unicef.org/laos/media/3921/file/Public%20Investment%20in%20Education_Advocacy%20Brief.pdf.

[28] UNICEF/SEAMEO (2020), “SEA-PLM 2019 Main Regional Report, Children’s learning in 6 Southeast Asian countries”, https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/7356/file/SEA-PLM%202019%20Main%20Regional%20Report.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2024).

[31] UNICEF/WHO/World Bank (2023), Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates Database, https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/malnutrition/ (accessed on 29 November 2023).

[12] United Nations (2023), “UNdata (database)”, https://data.un.org/Default.aspx (accessed on 17 January 2024).

[64] University of Notre Dame (2023), “Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initative”, https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/download-data/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).

[35] WHO (2023), BRIEF: Health or hardship? The impact of National Health Insurance on financial protection in Lao PDR, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/countries/lao-people%27s-democratic-republic/who-brief---health-financing-in-lao-pdr---march-2023.pdf.

[34] WHO (2022), Updated National Health Insurance Strategy aims to better protect people, ensure financial sustainability, https://www.who.int/laos/news/detail/06-10-2022-updated-national-health-insurance-strategy-aims-to-better-protect-people--ensure-financial-sustainability.

[54] Wolf, M. et al. (2022), 2022 Environmental Performance Index, Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, https://epi.yale.edu/downloads (accessed on 2024).

[1] World Bank (2024), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 24 June 2022).

[23] World Bank (2023), Poverty and Inequality Platform database, https://pip.worldbank.org/home.

[39] World Bank (2023), “World Bank ASPIRE (database)”, https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/datatopics/aspire (accessed on 17 January 2024).

[47] World Bank (2021), Environmental Challenges for Green Growth and Poverty Reduction: A Country Environmental Analysis for The Lao People’s Democratic Republic, World Bank, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/646361631109058780/pdf/Environmental-Challenges-for-Green-Growth-and-Poverty-Reduction-A-Country-Environmental-Analysis-for-the-Lao-People-s-Democratic-Republic.pdf.

[45] World Bank (2021), The Changing Wealth of Nations 2021: Managing Assets for the Future, World Bank, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1590-4.

[9] World Bank (2021), World Integrated Trade Solution (database).

[33] World Bank (2020), A Policy Snapshot of Health and Nutrition in Lao PDR, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lao/publication/a-policy-snapshot-of-health-and-nutrition-in-lao-pdr.

[43] World Bank (2020), Lao Biodiversity: A Priority for Resilient Green growth, World Bank, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/34131.

[16] World Bank (2019), Lao PDR 2018 Country Profile, Enterprise Surveys, World Bank, Washington D.C., https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/content/dam/enterprisesurveys/documents/country-profiles/Lao-Pdr-2018.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2024).

[3] World Bank (2006), “Lao Economic Monitor”, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8c665d54-b521-5ace-b7e6-abd76716923d/content (accessed on 28 September 2023).

Note

← 1. This consists of two types of employment: those employed in the informal sector and those informally employed in the formal sector or in households.