This chapter explores how labour markets can be a lever to help Panama increase equity and find a path towards inclusive growth. It argues that Panama’s dual labour market has been both the cause and a consequence of Panama’s large inequalities. Panama’s successful economic growth in the past decade has been based on a growth model that encompasses labour market inequality. While the productive tradeable service sector offers formal jobs for a few skilled workers; many low-skilled Panamanians are self-employed or informally employed in small, low-productive, non-tradeable service sector or agriculture firms. This chapter discusses a comprehensive policy package that would rebuild the social contract in Panama from a quality employment perspective. This chapter covers policies to strengthen education quality, endow workers with better skills, mitigate the perverse effects of labour informality and provide labour incentives to promote better quality jobs.

Multi-dimensional Review of Panama

Chapter 2. Building better skills and creating formal jobs for all Panamanians

Abstract

Quality employment is a key element in a country’s growth and development process. At the same time, it is central to a strong social contract, understood as a tacit pact between the state and citizens (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018). Although Panama has a relatively small, young population, employment is a crucial element since it acts as a link between quality economic growth, poverty reduction and income equality.

Panama’s dual labour market is both a source and a reflection of Panama’s large inequalities. The scarcity of good employment opportunities has been one of Panama’s long-lasting obstacles to making the labour market more inclusive, displaying significant variations across levels of education, income and regions. Panama’s successful economic growth model of the past decade has reinforced labour market duality. The productive tradeable service sector – mainly financial intermediation and trade, logistics and communications activities surrounding the Canal and the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) – that led Panama’s strong growth offers formal jobs for a few skilled workers in Panama City and Colón. In contrast, many working-age Panamanians encounter severe labour-market difficulties. Most of them are self-employed or informally employed in small, low-productive non-tradeable service sector or agriculture firms in the outskirts of Panama City and the provinces.

Strong economic growth has provided new, quality employment for some low-skilled workers, mainly in construction and transport, making the labour market more inclusive. The expansion led by the productive and competitive tradeable services sector spiked the demand for both public and private infrastructure. To fulfil this demand, the non-residential construction sector grew for more than a decade at a rate that is equivalent to doubling its stock of structures every four years. Large infrastructure projects, such the expansion of the Canal, the renovation of Tocumen airport, office buildings, warehouses and telecom infrastructure, generated a demand for low-skilled workers. Between 2003 and 2017 the construction sector created one out of every five new jobs and more than doubled its labour force. As such, construction absorbed some of the labour released by agriculture and fishing and provided low-skilled workers with more productive and better paying jobs. This employment shift can probably explain some of the improvement observed in informality and inequality reduction within these years.

Yet, the demand for non-residential construction cannot grow indefinitely at a higher rate than the rest of the economy – and in fact it has already started to slow down –, presenting a risk of losing some of the progress achieved in employment, poverty and inequality (Hausmann, Espinoza and Santos, 2016).

Creating formal quality productive jobs for future generations is Panama’s main challenge in terms of poverty and inequality reduction. While the tradeable services sector has led Panama’s growth and employment story for some decades, its poor direct employment creation capacity and the economic deceleration of the past five years has raised concerns. Though Panama is still growing at a strong pace – average annual rate of 5.6% between 2013 and 2017 –, the number of people out of work in Panama rose for the first time since the 1990s, reaching 6.1%, as a result of weakening labour demand and the subsequent drop in the number of new, salaried jobs created. Likewise, informality has gone back to its pre-boom growth path. Going forward, if the economy does not change its ability to generate employment, Panama will need to grow at an annual average of almost 6% of gross domestic product (GDP) for the next ten years to create enough jobs for future generations and fulfil its demographic dividend.1

To continue on the path towards a more inclusive labour market and avoid the dual market trap, Panama has to work on a policy package that includes economic diversification and better education. Employability barriers in Panama are mainly related to scarce formal job opportunities and insufficient work-related capabilities, but also poor market regulation, lack of law enforcement and poor financial incentives to look for a job (such as low potential pay, low-quality jobs and no unemployment insurance).

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows: it begins with an overview of employment and informality in Panama before going on to examine the main drivers of Panama’s labour market duality. These are: i) sectoral labour intensity and productivity differences; ii) firm size and self-employment; iii) pension coverage; iv) education and skills; and v) enforcement of labour laws. Assessing these drivers is key to making the Panamanian labour market strong, sustainable and inclusive, to reduce inequalities and to improve the lives of all Panamanians.

High labour market duality, informality and inequality

The high incidence of informality is one of the most salient features of Panama’s labour market. Informality is a key obstacle to making Panama more inclusive and labour productive. Although Panama’s economic growth has created more than half a million jobs since 2003, almost one-third of those jobs are poor-quality, informal jobs. Moreover, since 2012 two-thirds of all new jobs were informal (INEC, 2017). Informal workers are defined here as those workers (salaried and self-employed) who are not affiliated to social security systems (do not pay pension contributions) and therefore will not have the right to a pension when retired. Informality represents large losses for workers (in the form of social protection, low savings or upskilling), for firms and the wider economy (reducing productivity and tax revenues, for instance). Its interaction with contributory social-protection systems creates a vicious cycle: the majority of informal workers contribute irregularly, if at all, thereby weakening the systems which then provide insufficient support to workers when they need it. At the same time, insufficient savings accentuate old-age poverty.

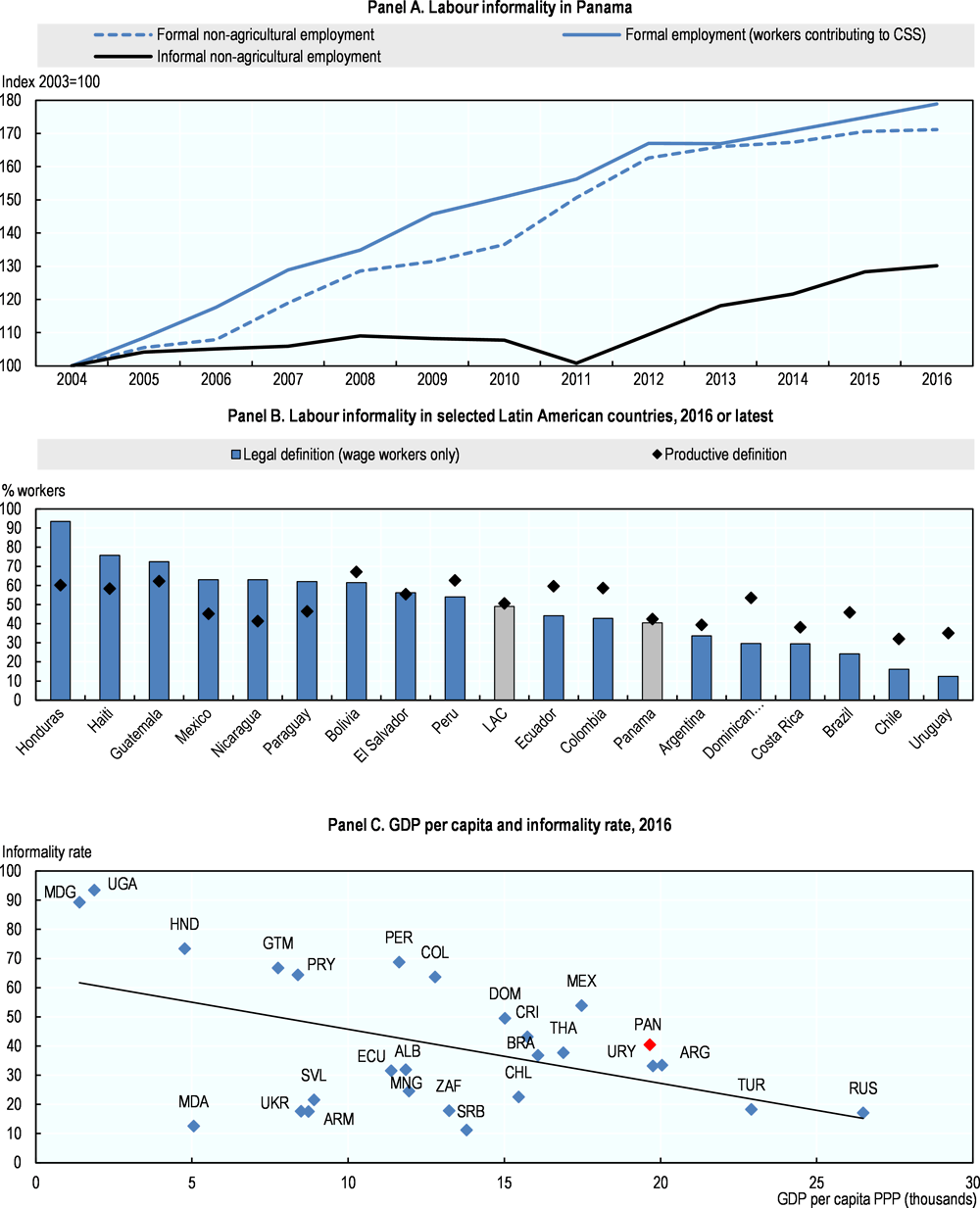

Informality is high and affects the most vulnerable workers

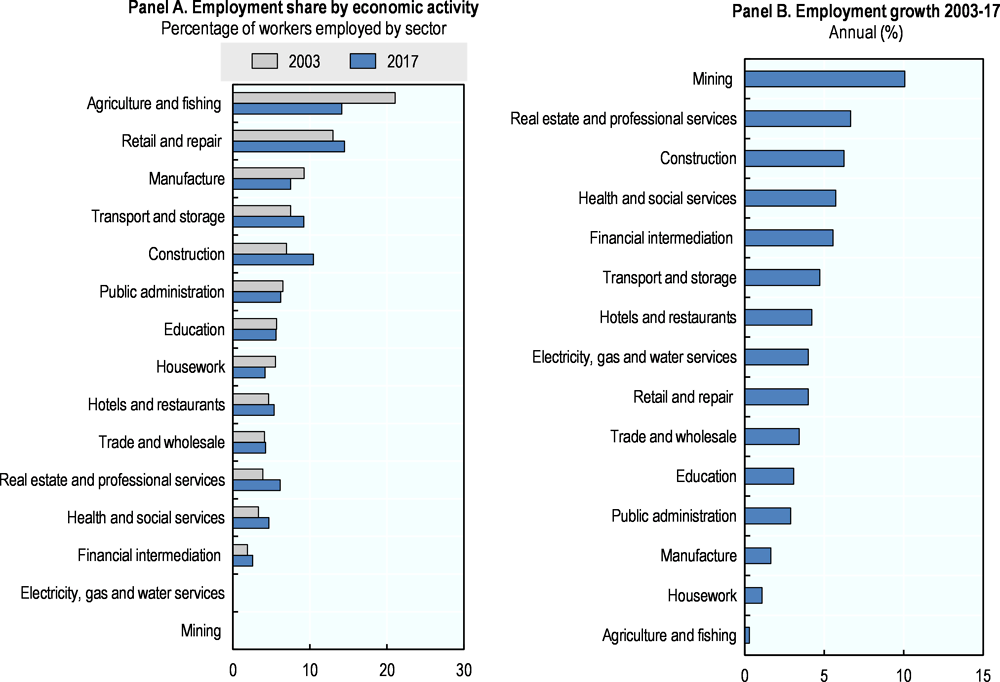

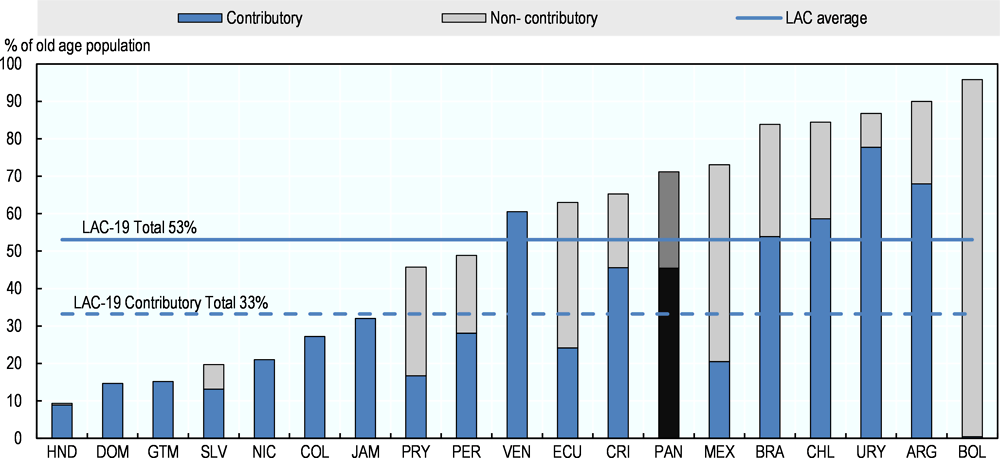

The informal sector in Panama is smaller than in most Latin America countries, but large by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) standards. Despite recent progress, labour informality remains higher than in other countries with similar levels of development such as Argentina, Turkey and Uruguay. In fact, in 2016, labour informality still affected around four out of ten non-agricultural workers and almost half of all Panamanian workers, especially affecting those in the lowest quintiles of the income distribution and thus contributing to inequality (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Informality rates in Panama and selected Latin American countries (LAC)

Notes: Legal definition of informality used unless specified: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired; for cross-country comparability rates are calculated for wage and salary workers only. Productive definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they are salaried workers in a small firm, non-professional self-employed, or zero-income workers. For Panel B, LAC average of 17 countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay. Data for Argentina are only representative of urban areas and wage workers.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC (National Institute of Statistics and Census of Panama), OECD and World Bank tabulations of SEDLAC (CEDLAS and World Bank, 2016), ILO, ILOSTAT (2017) and IMF (2017), World Economic Outlook (database).

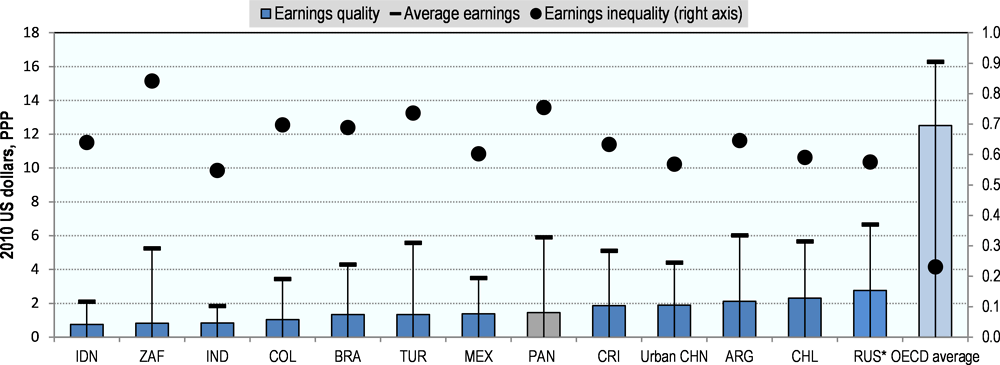

Box 2.1. Job quality in Panama

Overall job quality, a multi-dimensional concept capturing several job characteristics that contribute to the well-being of workers, is relatively low in Panama. The OECD Job Quality Framework is structured around three dimensions that are closely related to people’s employment situation: earnings quality (a combination of average earnings and inequality); labour market security (capturing the risk of unemployment and extreme low pay); and the quality of the working environment (measured as the incidence of job strain or very long working hours). These three dimensions jointly define job quality and should be considered simultaneously, together with job quantity, when assessing labour market performance. The OECD (2015a) has adapted the job quality framework to emerging economies by taking into account their labour market specificities, such as the weakness of social protection (inadequacy of benefits and low coverage of social insurance schemes), the relative high rates of working poverty, and the more limited data available for these countries.

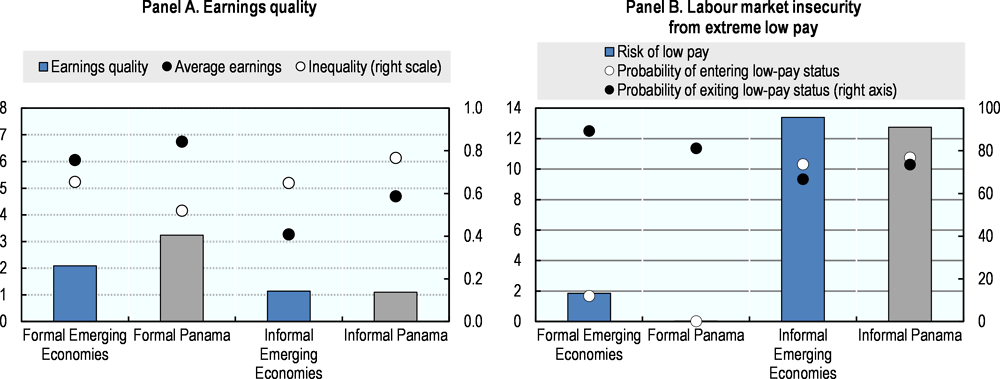

Similar to other Latin American countries, Panama’s job quality is much lower than the OECD average in two out of the three dimensions. The results show special concern on the quality of earnings and risk of entering extreme low-pay status. Earnings inequality is particularly large in Panama. The levels of earnings inequality are more than three times higher than that in OECD countries as in most emerging economies (Figure 2.2) (OECD, 2015a).

Figure 2.2. Earnings are lower and more unequal than in OECD economies

Note: Calculations are based on net hourly earnings and concern 2013 values, except for Brazil (2009), Chile (2009), China (2009), Argentina (2010), India (2011) and Panama (2016). The OECD average is a simple cross-country average of earnings quality. Data for Argentina are representative of urban centres of more than 100 000 inhabitants. The figures for Russia are based on imputed data on households' disposable income from information on income brackets, and therefore include the effect of net transfers. Individual hourly income for two-earner households was calculated using available information on partners' employment status and working hours.

Source: OECD calculations based on national household -Encuesta Continua de Hogares- (INEC, 2016) and OECD (2015b).

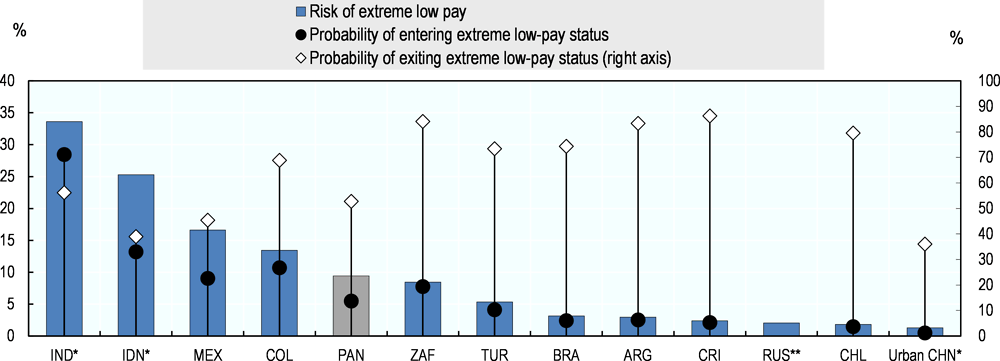

The risk of workers falling into extreme low pay in Panama is high. Although workers in other emerging economies such as India, Mexico and Colombia face higher risk of workers falling into extreme low pay; Panama’s risk of falling into extreme low pay more than triple that of Argentina, Brazil and Costa Rica. Moreover, social transfers are not fully able to reduce this risk which translates into higher levels of overall labour market insecurity than in most OECD countries (2015a).

Figure 2.3. Labour market insecurity due to extreme low pay is higher than in OECD economies

Notes: The low-pay threshold is set at USD PPP 1 in terms of net hourly earnings and corresponds to a disposable income per capita of USD PPP 2 per day in a typical household of five members with a single earner working full-time. The choice of the household size follows Bongaarts (2001) and is based on data from Demographic and Health Surveys. Country rankings are generally robust to changing the low-pay threshold. The probability of entering and exiting low-pay status are calculated by the pseudo-panel methodology proposed by Dang and Lanjouw (2013) using the sample of employed individuals. The risk of low pay is calculated by (the scaled transformation) of the probability of entering low-pay status times the inverse of the exit probability, and shows the likelihood that an individuals’ earnings below the low-pay threshold at any given time. The data displayed represent net hourly earnings adjusted for social transfers. Calculations are based on 2009-10 data, except for Brazil (2009-11), Chile (2009-11), China (2008-09), Costa Rica (2010-12), India (2011-12), Mexico (2010-12), Russia (2010-12), South Africa (2010-12), Turkey (2011-12) and Panama (2013-16). The data for China, India and Indonesia do not contain transfers, so an insurance rate of 0% is assumed. For Russia, transition probabilities could not be estimated due to categorical income data. The corresponding risk figure therefore represents the share of employed working-age individuals living in households with a monthly disposable income of less than RUB 6000, which corresponds to an hourly low-pay threshold of USD PPP 1.14 (as of 2010) for a member of a two-earner family working full-time.

Source: OECD calculations based on national household -Encuesta Continua de Hogares- (INEC, 2016) and OECD (2015b).

Figure 2.4. Job quality is worst for informal than formal workers

Note: Figures represent unweighted country averages across all sampled emerging economies except Indonesia. Due to missing information, China was excluded from the calculation of labour market security in Panel B. Classification between formal and informal status is based on social security payments (employees) and business registration (self-employed), except for Colombia and Russia where information on work contract (written or not) was used, and Panama where information pension contributions was used for all workers.

Source: OECD calculations based on national household -Encuesta Continua de Hogares- (INEC, 2016) and OECD (2015b).

Informal jobs in Panama have poorer earnings quality and larger insecurity from the risk of low pay than formal jobs, similar to other emerging economies. Figure 2.4 uses the job quality framework to measure the quality gap between formal and informal jobs in Panama along two dimensions of the OECD Job Quality Framework. Although earnings inequality is similar among formal and informal workers; on average, formal workers earn more than informal workers. Thus the earnings quality of formal workers is substantially higher. Lower average earnings for informal workers are consistent with the perception that informal jobs are less productive. In addition, the analysis of upward and downward earnings mobility reveals that downward mobility is generally higher in informal jobs, whereas upward mobility is significantly larger in formal jobs. This means that workers holding informal jobs face a higher risk of wage loss as well as fewer opportunities for wage improvements.

Source: OECD Employment Outlook 2015.

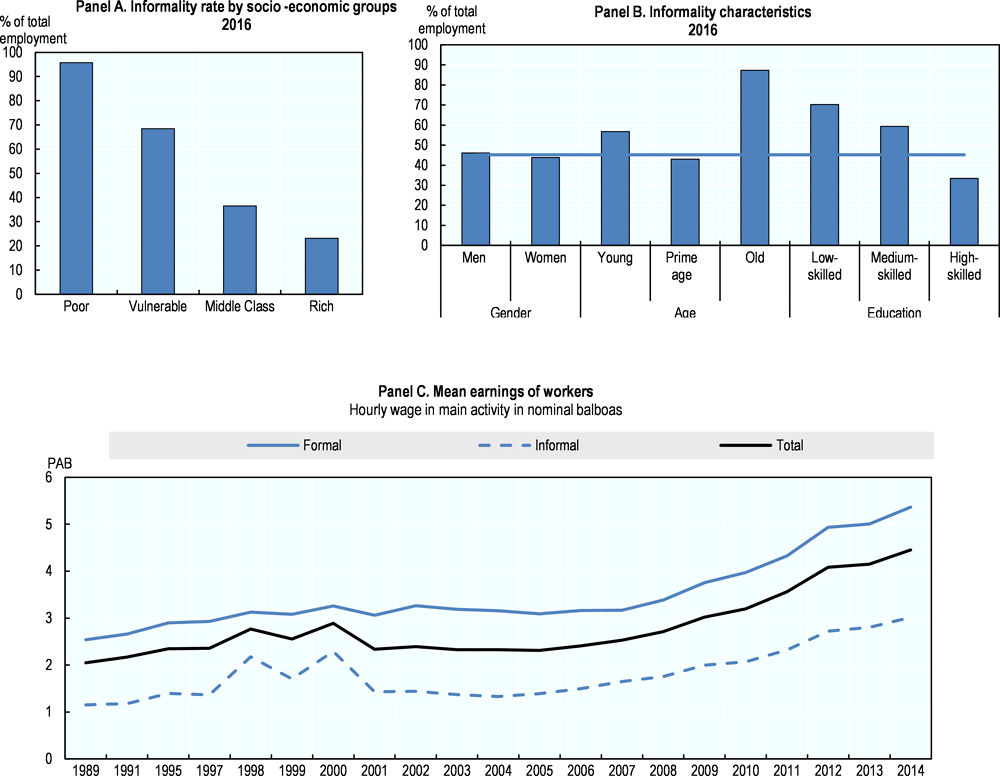

The incidence of informality is much higher for workers from poor and vulnerable households, youth, and the less educated, perpetuating the vicious cycle of inequality and low productivity (Figure 2.5). In fact, labour informality and low skills are strongly connected, decreasing as workers attain higher levels of education. Almost 70% of the working population with only primary education are employed in unregistered jobs, compared with only 33% of those who attained a tertiary degree. Likewise, youth are more likely than their adult counterparts to end up in informal employment (INEC, 2017).

Figure 2.5. Informality enhances inequality

Notes: PAB = Panamanian Balboa.[i] Panels A and B: Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired; for cross-country comparability rates are calculated for wage and salary workers only. Panel C: Productive definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they are salaried workers in a small firm, non-professional self-employed, or zero-income workers. A firm is considered small if it employs fewer than five workers. The three skills level groups are formed according to years of formal education: low=0 to 8 years, medium=9 to 13 years, and high=more than 13 years.

Source: INEC (2017), CEDLAS and World Bank (2016), SEDLAC (Socio-economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean), http://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/en/estadisticas/sedlac/.

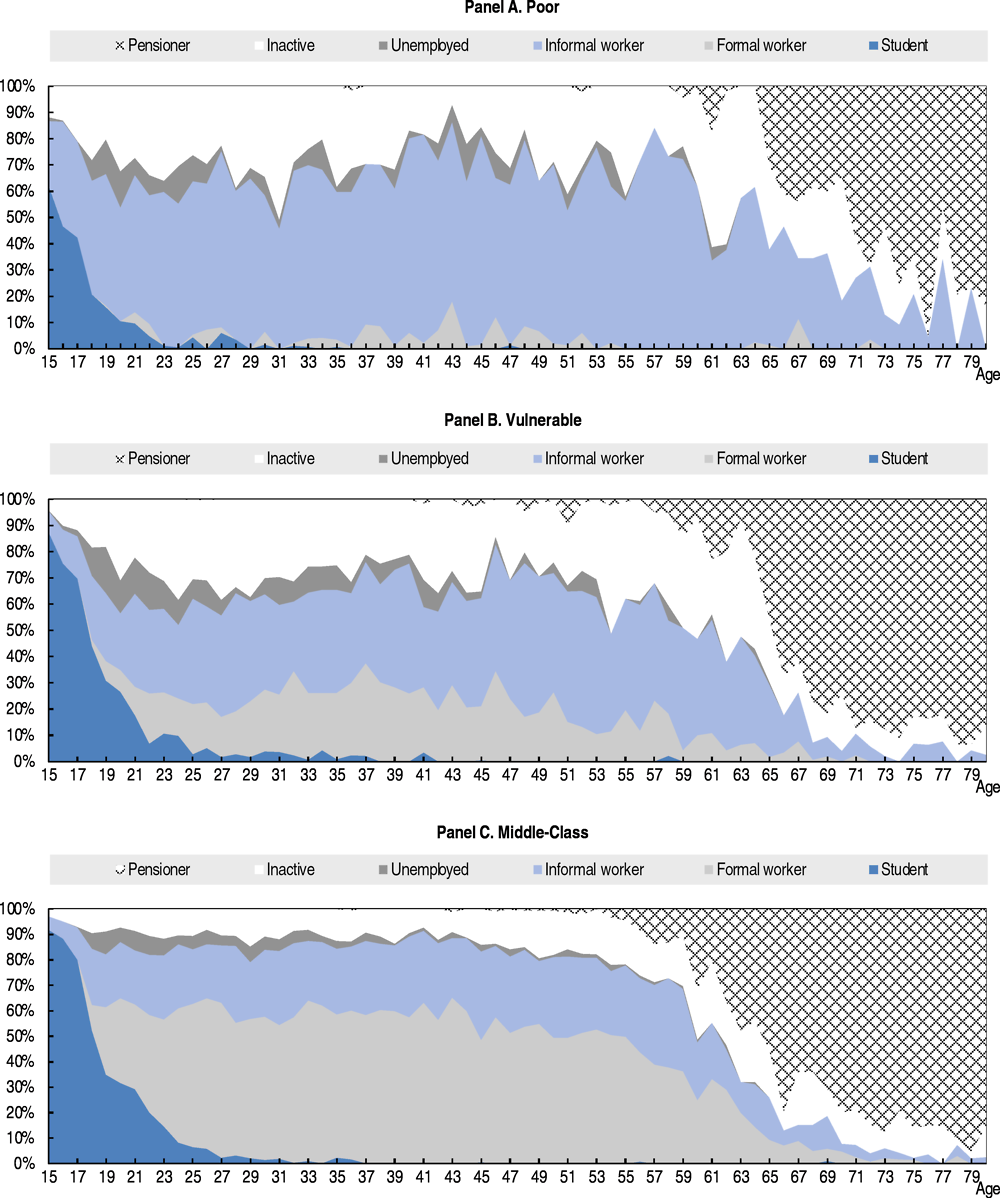

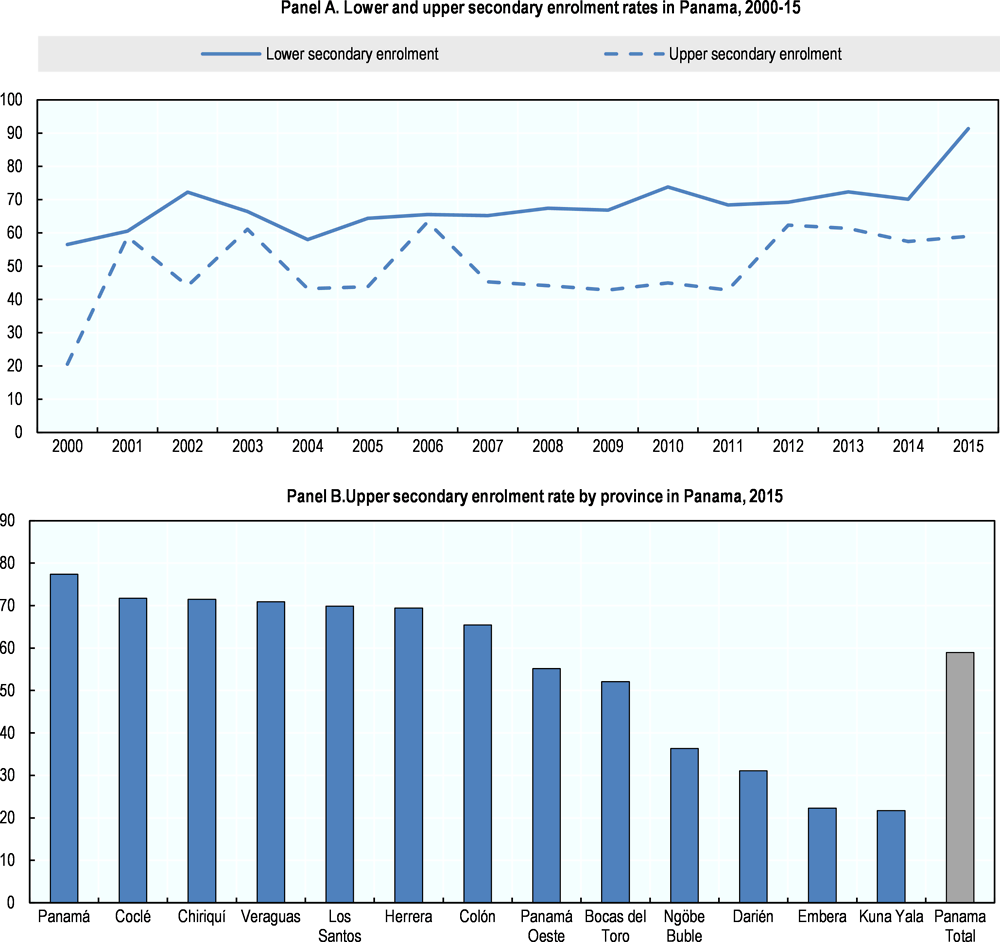

Inequalities in the labour market start early. Young workers from poor or vulnerable families are more likely to hold informal jobs than those from the middle class. Likewise, youth from these households leave school earlier than their peers in better-off households (Figure 2.6). At age 15, six out of ten young people living in poor households are in school; at age 30, however, eight out of ten are informal workers or inactive. In vulnerable households, six out of ten young people aged 30 are working informally or inactive. In contrast, remarkable differences are observed among consolidated middle-class households: nine out of ten of youth are in school at age 15, while six out of ten have a formal job at age 30.This suggests that a certain degree of labour market segmentation exists in Panama, making the transition from school to work a particularly relevant stage in young people’s careers and futures (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2016).

Figure 2.6. Activity status by single year of age and socio-economic status (2016)

Notes: Socio-economic classes are defined using the following classification: “Poor” = individuals with a daily per capita income of USD 4 or lower. “Population at risk of falling into poverty” = individuals with a daily per capita income of USD 4-10. “Middle class” = individuals with a daily per capita income of USD 10‑50. Poverty lines and incomes are expressed in 2005 USD purchasing power parity (PPP) per day). Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

Box 2.2. The informality trap

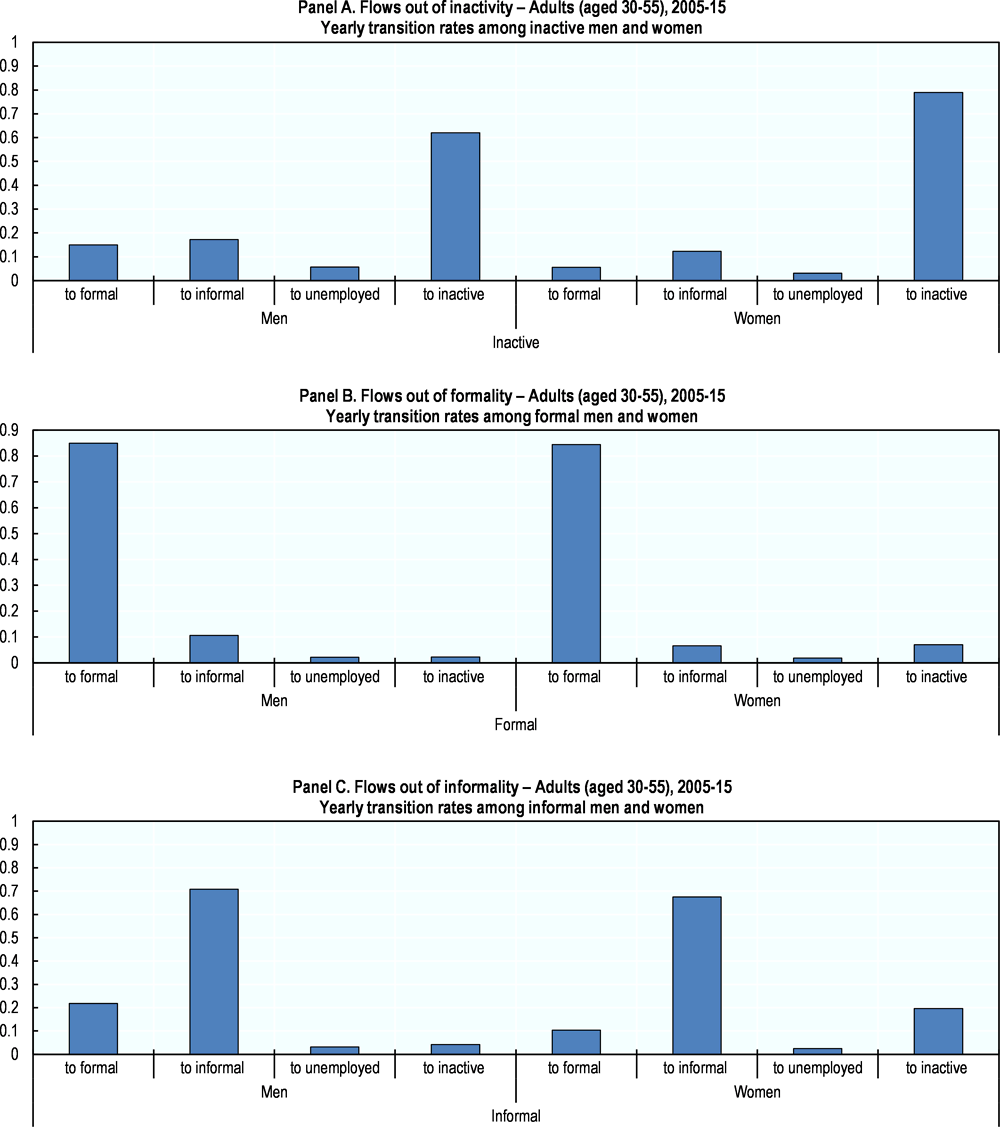

Latin America’s labour market exhibits frequent flows between formal “good” jobs and informal “bad” jobs (Bosch, Melguizo and Pages, 2013). Flows out of informal jobs are more common than those out of formal jobs, as a considerable number of informal workers make the transition into formal jobs every year. Panel data capturing the dynamics of how workers aged 30 to 55 move in and out of informal employment in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico show that on average 34% of female workers and 29% of male workers who are currently in the informal sector will not remain there after a year (Figure 2.7). Almost 10% of female informal workers will move into formal jobs, and 22% of males will do so.

Flows out of the formal sector and into the informal sector are sizeable, stressing the need to place better incentives to stay in, or move towards formality. On average, 15% of workers who are currently in the formal sector will not be so within a year. Almost 10% will be informal workers a year later, compared with 3% who will be unemployed (Figure 2.7). This raises three labour policy issues in Latin America. First, formal jobs are scarce, and more quality jobs are needed. Second, unemployment benefits might not be generous enough to support the unemployed while they look for quality jobs, forcing them to take lower-quality jobs instead. And third, in some countries, the relatively high cost of formalisation for workers might encourage some of them to prefer informal types of employment.

This pattern of entering and leaving the formal sector is also evidence that informal jobs are more unstable owing to a higher risk of job loss. Informal jobs appear to be associated with a higher probability of making the transition into unemployment or inactivity than formal jobs, particularly among women. Transitions from informality into unemployment do not seem much higher for women than men, while transitions from informality to inactivity are quite high for women. Almost two out of three informal female workers who transition out of informality every year become inactive, compared with only 14% of informal male workers. Certainly, this can also result from personal choice. Women who are planning to leave the labour force soon for family reasons, for example, may be more likely to look for more flexible work, and thus self-select into informal work (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2016).

Overall, informal jobs seem to be a trap for most workers, particularly for youth, women and low-skilled workers, having long-term adverse effects on equity. While holding an informal job might be a “springboard” for some, it can have scarring effects for most workers’ employment prospects and future wages. Bosch and Maloney (2010), and Cunningham and Bustos (2011) found that informal salaried work may actually act as a preliminary step towards the formal sector. In fact, it might be a standard queue towards formal work, especially for younger workers, which can serve as training time and not necessarily harm an individual’s career path. However, Cruces, Ham and Viollaz (2012) found strong and significant scarring effects in Argentina: people exposed to higher levels of unemployment and informality in their youth fare systematically worse in the labour market as adults (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2016). Additionally, informal firms generally provide workers with fewer opportunities for human capital accumulation and are less productive (La Porta and Schleifer, 2014). All of this might thus pose an additional burden in earnings and career advancement to the most vulnerable (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2016).

Figure 2.7. Flows in Latin America’s labour market

Notes: Results show yearly transition rates into and out of informality. This analysis is limited to urban populations in four countries (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Chile) owing to data limitations. Data for Argentina are representative of urban centres of more than 100 000 inhabitants. Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired.

Source: OECD and World Bank tabulations of LABLAC (CEDLAS and World Bank, 2016).

Informality goes hand in hand with the Panama’s dual economy and dual labour market

Overall, strong and steady growth has led to job creation in Panama between 2001 and 2017 at an average annual employment growth of 3.4% (INEC, 2017). Panama has been one of the fastest-growing economies in the world over the previous decade, at double the regional growth rate. This growth has been led by the development of a modern tradeable service sector – financial intermediation and mainly trade, logistics and communications activities surrounding the Canal and the SEZs –, which mostly employ skilled labour. At the same time, both public and private infrastructure projects demanded by this growing logistics service sector have fuelled further growth through non-residential construction and created new – formal – jobs for non-skilled workers.

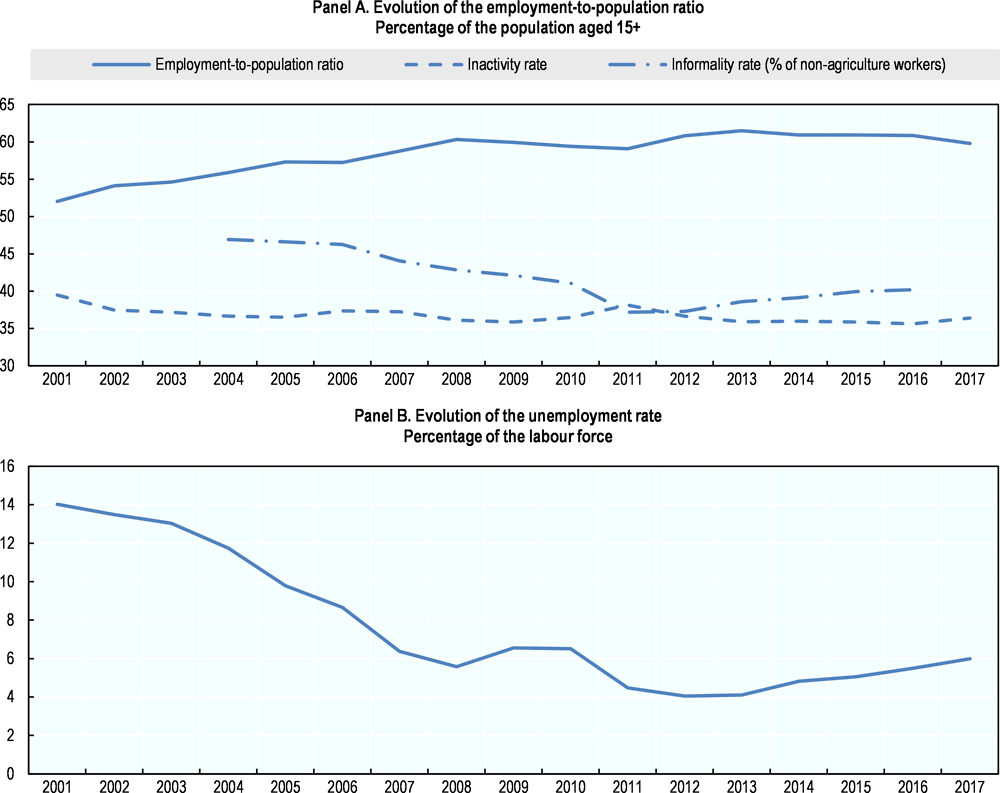

This period of expansion (2001-17) can be divided in three sub-periods: an initial growth period, the peak growth period, and slow-down period. Analysing only the extremes of the period does not provide a full picture of what happened with employment and job creation in Panama. As such it is important to differentiate these three stages. As overall economic growth strengthened from 2003-07, employment grew fast at an average of 4% as the employment to population ratio rose, unemployment halved and informality fell almost 3 percentage points. From 2007 through 2012, informality fell almost 7 percentage points as employment continued to grow, but both employment to population ratio progress and unemployment decline significantly slowed. Finally, since 2012 Panama’s employment rate has stagnated around 60% (population aged 15 and over) and informality has increased as a result of weakening labour demand and the subsequent drop in the number of new, salaried jobs created (ECLAC/ILO, 2016). This slowdown is also reflected in the rising unemployment rate (6.1% in the third quarter of 2017), which especially affects workers with only primary and secondary education (Figure 2.8) (INEC, 2017).

Formal job creation is still a challenge for Panama, even though employment grew during the three periods. It was only during the period of fastest economic growth and employment creation (2007-12) that informality significantly decreased. While the benefits of economic growth can trickle down to the informal, without formal employment-oriented policies, growth by itself cannot be relied upon to translate spontaneously into productive jobs and better working conditions. The pattern and sources of growth are equally important in reducing labour informality in the long run.

Figure 2.8. The improvement of labour market conditions is slowing

Note: Legal definition of informality: a worker is considered informal if (s)he does not have the right to a pension when retired.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

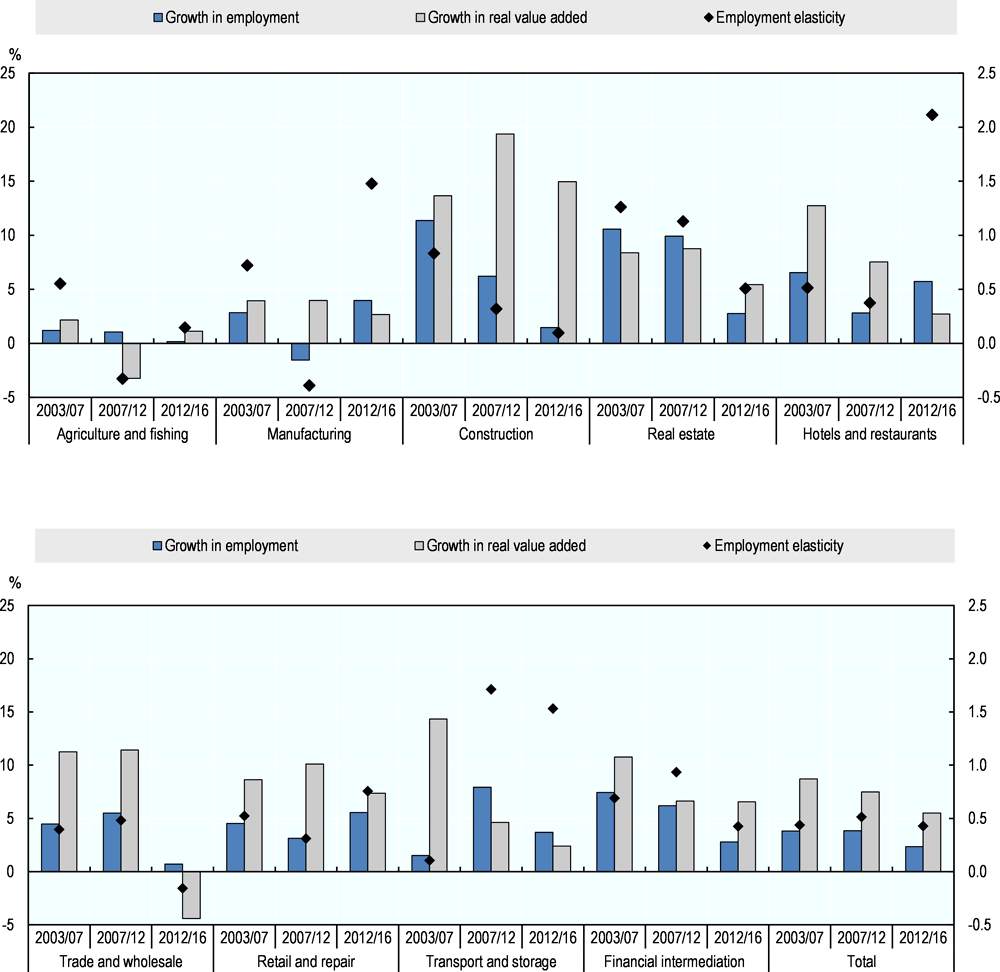

Figure 2.9. The employment structure is changing for low-skilled workers

Growth resulted in some changes in the employment composition of Panama during the last decade, especially for low-skilled workers. The high demand for non-residential construction, and goods and services created changes in GDP composition that have been accompanied by changes in the structure of employment, in particular over the high-growth spell between 2003 and 2012. Job creation has been driven mainly by the construction and real estate as well as the trade sector – wholesale, transport and storage – retail and repair, which together account for almost two-thirds of all new jobs created in Panama from 2003 to 2017 (INEC, 2016). At the same time, there has some been labour reallocation from primary sectors to other sectors of the economy (Figure 2.9). The construction boom has demanded low-skilled workers and absorbed some of the labour released by agriculture and fishing. While construction created almost 100 000 jobs since 2003 (16% of all new jobs) and expanded its share of employment from 7% to 10%, agriculture created only 27 000 new jobs from 2003 to 2016 (5% of all new jobs) reducing its employment share from 21% to 15%. To a lesser extent, the transport, storage and communication sector expanded its share of employment from 7% to 9% and created 12% of all new jobs, although not all of them were for low-skilled labour. At the same time, employment in retail and repair also grew and surpassed agriculture and fishing in share of people employed (14.5% and 14% respectively). Still, agriculture and fishing continues to be the second largest employer in Panama even though the sector has registered low employment growth, low activity growth and a corresponding loss of share of GDP (INEC, 2017).

This employment shift can probably explain some of the improvement observed in inequality since the early 2000s. As low-skilled workers moved from agriculture to construction and transport jobs their salaries increased and informality fell. Yet, now that the construction boom is expected to decelerate and the modern service sector demanding high skills is expected to continue leading growth, there is a risk of losing some of the progress achieved in terms of poverty and inequality (Hausmann, Espinoza and Santos, 2016).

Creating formal high-quality productive jobs for future generations stands out as one of Panama’s main challenges in the next decade. While the dual economy has led Panama’s growth and employment story for some time now, it is time for other sectors to play a more important role in creating jobs.

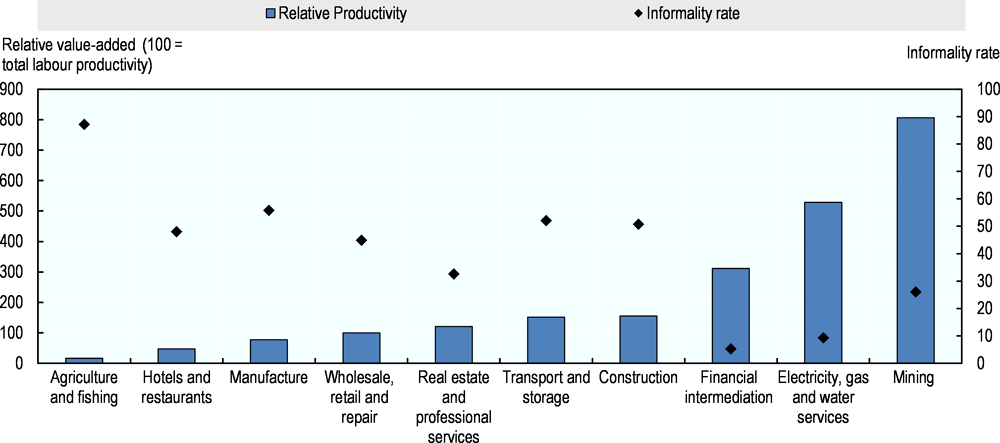

Informality is closely linked to productivity

The most direct connection between productivity and labour informality is that low-productive workers do not produce enough value-added to cover the costs of being hired formally. Their production remains profitable only under informal working conditions. Evidence confirms this strong correlation between low productivity and high informality, with higher levels of informality concentrated in developing countries (La Porta and Shleifer, 2014). Panama is no exception; the least productive sectors such as agriculture and fishing, wholesale retail and repair, hotels and restaurants, and manufacturing are highly informal, and employ two-thirds of all informal workers (Figure 2.10).

Informality increases wage dispersion, negatively affecting equity. Formal workers earn, on average, significantly more than informal workers. Lower average earnings for informal workers are consistent with the consensus view that informal jobs are less productive.

Figure 2.10. Relative productivity and labour informality in Panama, 2016

Note: Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired. Labour productivity is measured as the annual value added (the value of output less the value of intermediate consumption) per employee.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

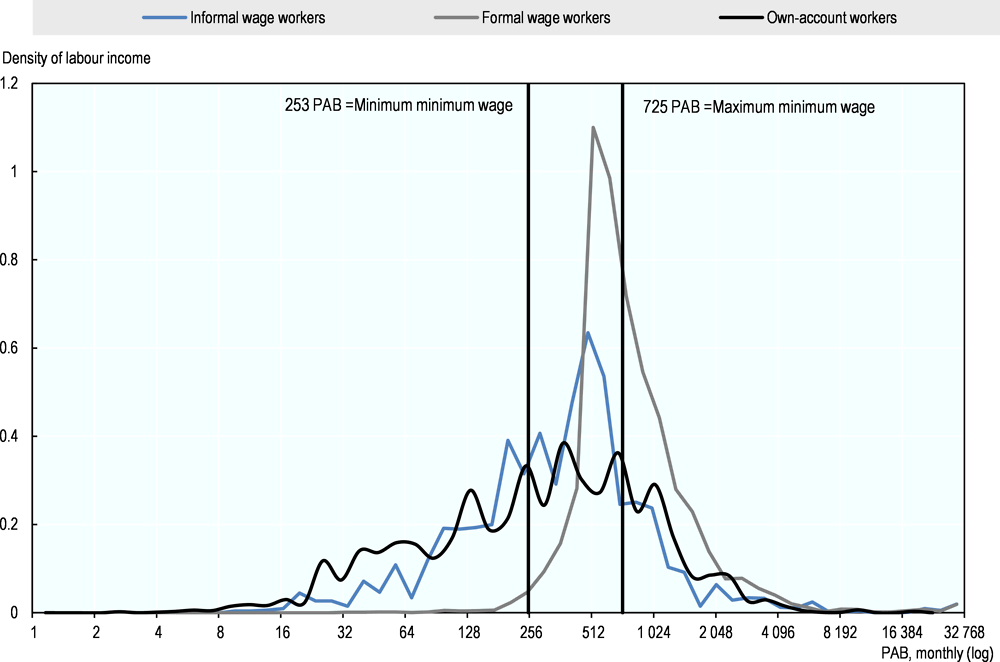

The productivity level of a large share of informal workers leads to an output per worker that does not cover the minimum costs of formal hiring (i.e. the minimum wage). If labour income is used as a proxy for labour productivity, then the productivity of almost two-thirds of workers in Panama is below the minimum wage they would need to be paid if they were hired formally (plus the social security contribution costs). Low productivity, then, is a functional barrier to formality for these workers, as employers will not readily bear the costs of the formalisation of workers who do not produce enough to cover the costs. In fact, labour income of more than half of informal wage workers – around 65% – remains below the average minimum wage of PAB 423, while 47% of them remain below the least generous minimum wage in Panama of PAB 253 and 85% of them remain below the highest minimum wage in Panama of PAB 725. The income distribution of own account workers is very similar to that of informal wage workers with two out of three own account workers earning less than average minimum wage (Figure 2.11).

On the other hand, the productivity of formal workers appears sufficient to bear these costs. Only 8% of formal wage workers earn monthly salaries close to or below the average minimum wage of PAB 423 (and less than 2% of formal wage workers less than the lowest minimum wage of PAB 253). Although it appears that the minimum wage is too low to be binding for most formal jobs, it may affect the formalisation decision of a significant share of workers. The minimum wage plays a benchmark role, which can be seen by the density of informal workers earning between the highest and lowest minimum wages (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11. Informality and earning, 2016

Notes: Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired. Kernel estimates of monthly-equivalent labour market incomes for dependent workers based on their classification as formal or informal. The horizontal bars represent the lowest and highest minimum wage of the minimum wage matrix (PAB 253 and PAB 725 respectively in 2017).

Source: OECD estimates based on microdata from Encuesta de Propsitos Multilpes of 2016 (INEC, 2016).

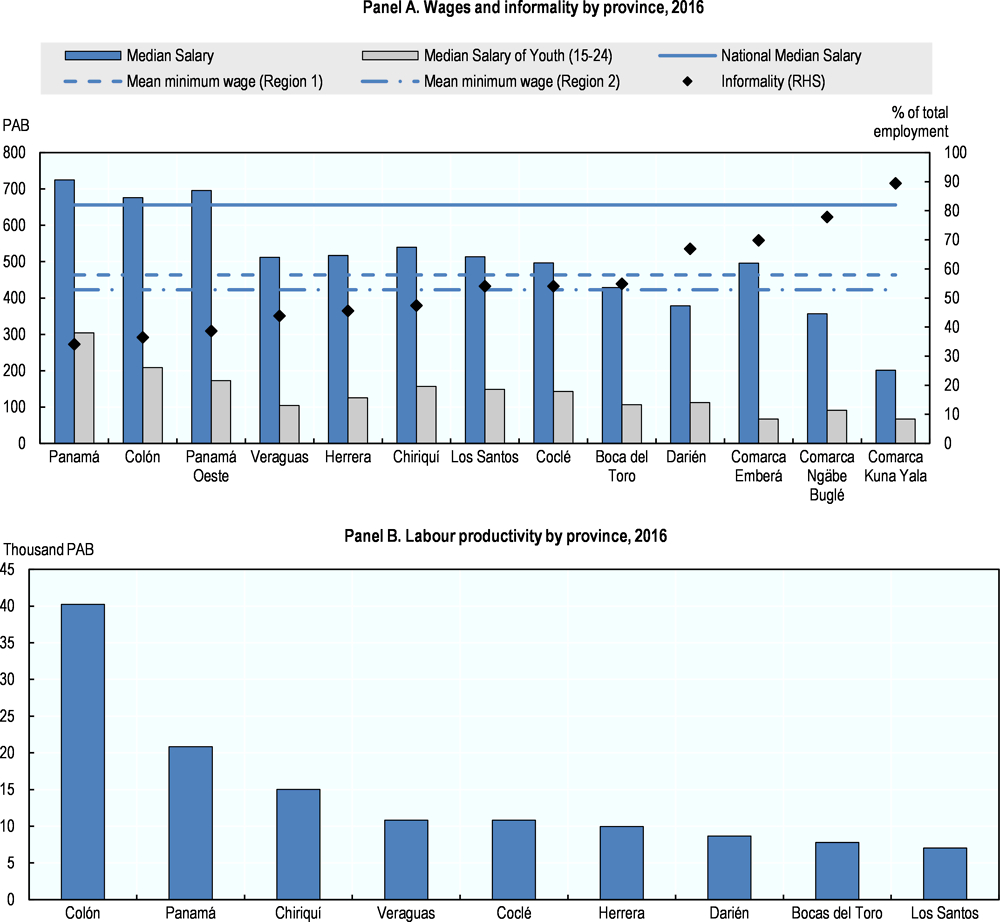

Differences in informality rates across regions are closely linked to differences in productivity levels as well as to the proportion of social security over total labour costs. There are significant differences in total labour costs (partly related to the complex minimum wage matrix) and the wedges on workers’ wages (implied formalisation costs – that is, the portion of the total labour costs that goes towards paying taxes and social security contributions) between departments, urban and rural settings, and geographic areas (Figure 2.12). In general, urban settings have higher labour costs, more so in Panama where the minimum wage matrix differentiates among urban and rural areas establishing a lower minimum wage for workers in rural areas. Moreover, although formalisation costs are proportional among all departments, there is greater variance with respect to total labour costs. Informality tends to be lower in geographic locations where the total labour cost is further from the minimum labour cost (i.e. Coclé, Boca del Toro, Darién and the comarcas). In this regard, the presence of competitive and productive industries such as the financial sector or the Canal and the SZEs compared to low-productive agriculture and fishing, retail and repair, and hotels and restaurants are better indicators of higher levels of income and, thus, of higher labour costs and lower levels of informality (Céspedes, Lovado and Ramirez, 2016; OECD, 2015a).

Figure 2.12. Informality, wages and productivity by province

Notes: Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired. Labour productivity measured as the value added (the value of output less the value of intermediate consumption) over the annual average personnel employed per month.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

Box 2.3. Estimating wage differentials for informal and female workers

Household data from 2016 make it possible to estimate the determinants of wages in Panama, accounting for a number of specific characteristics of the job, including characteristics of the worker, the employer and also regional differences. Such wage estimations also allow an approximation of the wage differentials that informal workers and women face on labour markets, conditional on other factors. These estimations are presented below.

The estimated coefficient for the indicator variable representing a formal worker, defined by contributing to the social security system, suggests a wage differential of 35% less than formal workers, all else being equal. In other words, informal workers on average are paid one-third less than formal workers with equal personal and job characteristics. Similarly, female workers earn a wage differential of 30% less than men (Table 2.1).

Individual characteristics that the estimations account for include age, approximated by three age groups. Relative to those aged between 29 and 64, youths earn less while older workers earn more. Educational attainments of the individual are accounted for in the estimations through five different categories. Predictably, wages are rising with higher educational attainments.

Table 2.1. Wage estimation results. Dependent variable: Log of monthly total labour income

|

|

Coefficient estimate |

Standard error |

|---|---|---|

|

Informal |

-0.347*** |

0.00149 |

|

Women |

-0.308*** |

0.00137 |

|

Age under 25 |

-0.156*** |

0.00196 |

|

Age 50 to 60 |

-0.0135*** |

0.00148 |

|

Illiterate |

-0.227*** |

0.00464 |

|

Some secondary education |

0.179*** |

0.00196 |

|

Secondary education completed |

0.345*** |

0.00198 |

|

Some post-secondary education |

0.511*** |

0.00241 |

|

Tertiary education completed |

0.903*** |

0.00219 |

|

More than 5 years with current employer |

0.164*** |

0.00129 |

|

Public sector employee |

0.313*** |

0.00287 |

|

Domestic employee |

0.185*** |

0.00396 |

|

Hours worked |

0.0230*** |

0.00005 |

|

Constant |

4.616*** |

0.00461 |

|

Fixed effects for 12 major regions |

included |

|

|

Fixed effects for 21 industries |

included |

|

|

Observations |

14 412 |

|

|

R-squared |

0.547 |

|

Notes: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10%, 5% and 1%, respectively.

Source: OECD estimates based on microdata from Encuesta de Propsitos Multilpes of 2016 (INEC, 2017).

A productive transformation is needed to create more and better jobs

Informality is directly linked to Panama’s dual economic structure. On one hand, a small share of the working population – less than 20% – is employed in the high-productivity industries such as the financial intermediation sector and the modern tradeable service sector – logistics, communications, transport, trade services, and information – which mostly consist of formal jobs but create little employment. On the other hand, almost half of the population works in low-productivity, informal services and agriculture. This contributes to labour market segmentation: informal and formal sectors are largely separated, with a large informal sector consisting mainly of many poorly educated agricultural, retail or construction own account or microenterprise workers running firms that add little value, and a formal sector of educated workers who run bigger, more productive firms in the tradeable services sector.

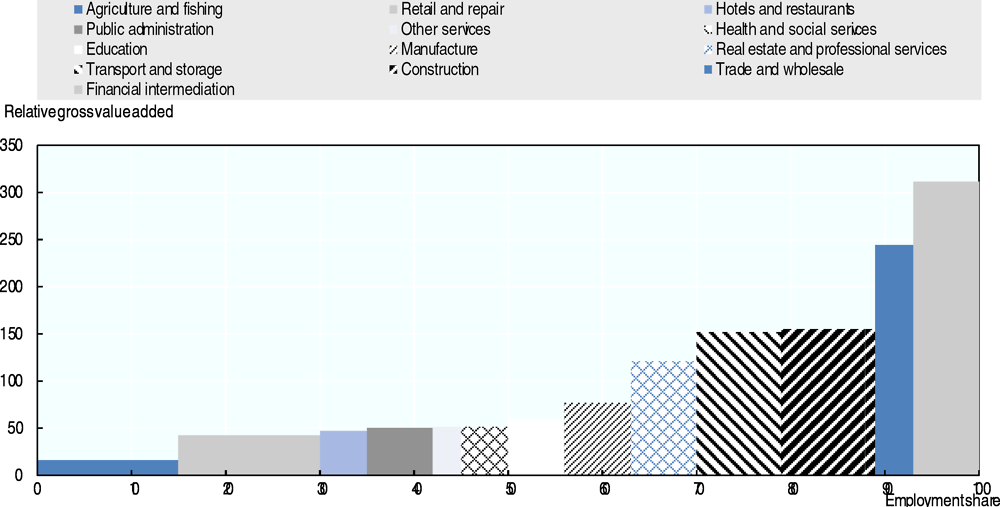

The most productive sectors create little employment

Panama’s employment it is still concentrated in low-productivity, informal sectors. Although the construction boom created new formal jobs, two out of three workers in Panama are employed in a sector with below average labour productivity such as agriculture and fishing, retail and repair, and hotels and restaurants, a fact that might be at the core of the large income inequality in Panama (Figure 2.13). Moreover, half of the Panamanian construction workers are still employed informally, while the activity is expected to slow down. This demonstrates both the inverse relationship between productivity and informality and that Panama’s economy is not currently conducive to increased formal job creation.

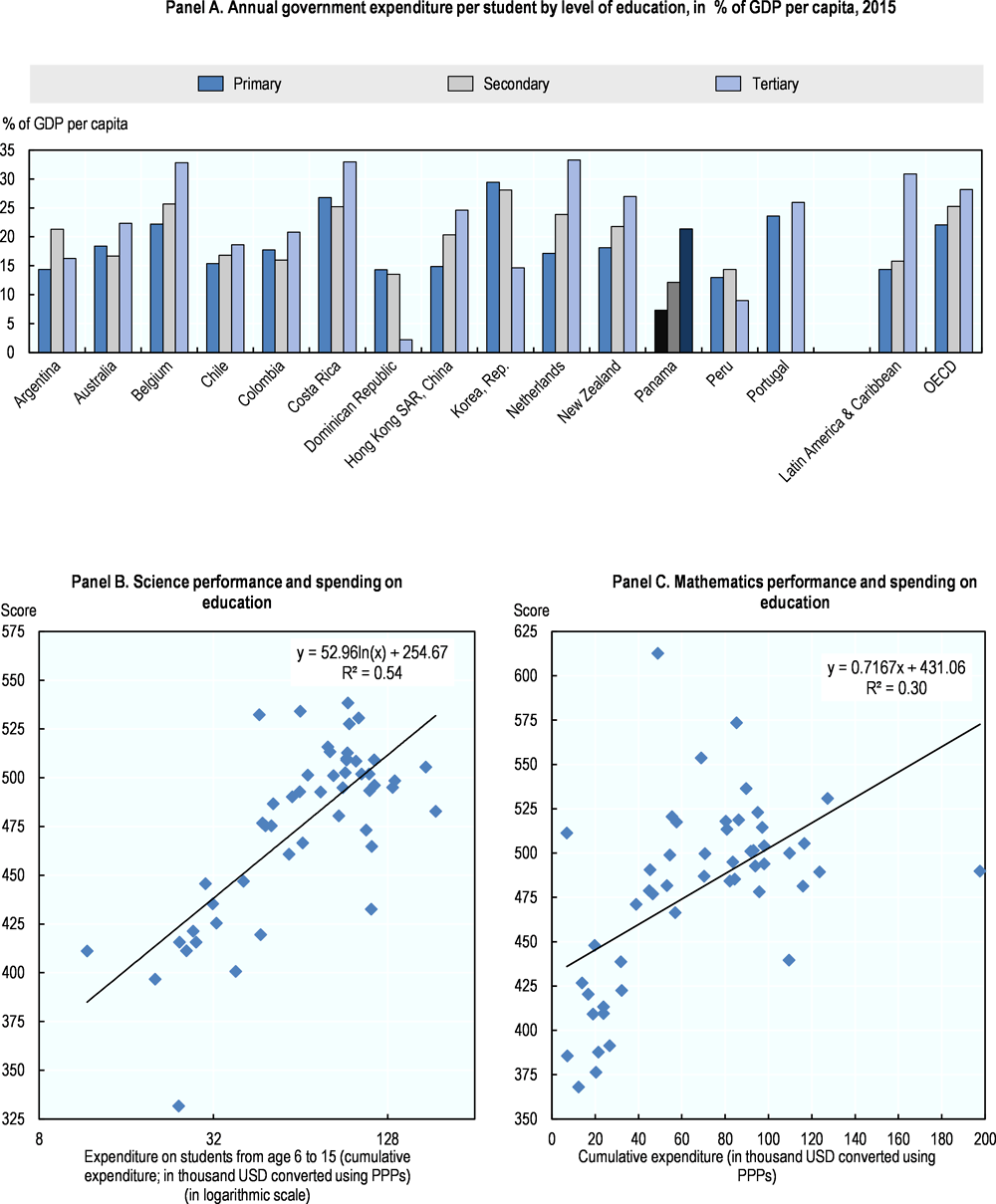

Relative productivity across sectors shows some particularities of the Panamanian economy: a highly productive modern tradeable service sector, a fast-growing construction sector and a low-productivity non-tradeable service sector. The labour productivity of Panama’s financial sector and logistic sector activities – trade, repackaging services, and transportation, storage and communications – are between 2.5 and 3 times the total labour productivity (Figure 2.13). These are the internationally competitive activities that have driven Panama’s economic growth in the last two decades. Additionally, the construction and real-estate sectors have made significant gains in productivity, driven by expansion of the Canal and the renovation of Tocumen airport, office buildings, warehouses, telecom infrastructure, shopping malls and other infrastructure demanded by the modern service sector. At the same time, the non-tradeable service sector – mainly retail and repair, hotels and restaurants, education, health and social services – halves the total labour productivity of Panama but employs half of the working population. The analysis on the basis of sector-level data is limited by the level of detail available in labour statistics. For example, Figure 2.13 bundles private and public education and health services as well as all sectors in manufacturing, whose productivity levels are very different. More notably, it aggregates all trade and wholesale activities, while there are large productivity gaps between Panama Canal-related activities, the SEZs, and other types of wholesale. Likewise it considers the agricultural, livestock, hunting, forestry and fishing sectors as a whole as well as aggregate all restaurants and hotels whose productivity levels are very heterogeneous across the country under the same category.

Figure 2.13. Productivity and the distribution of labour in Panama, 2016

Note: Labour productivity is measured as the annual value added (the value of output less the value of intermediate consumption) per employee.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

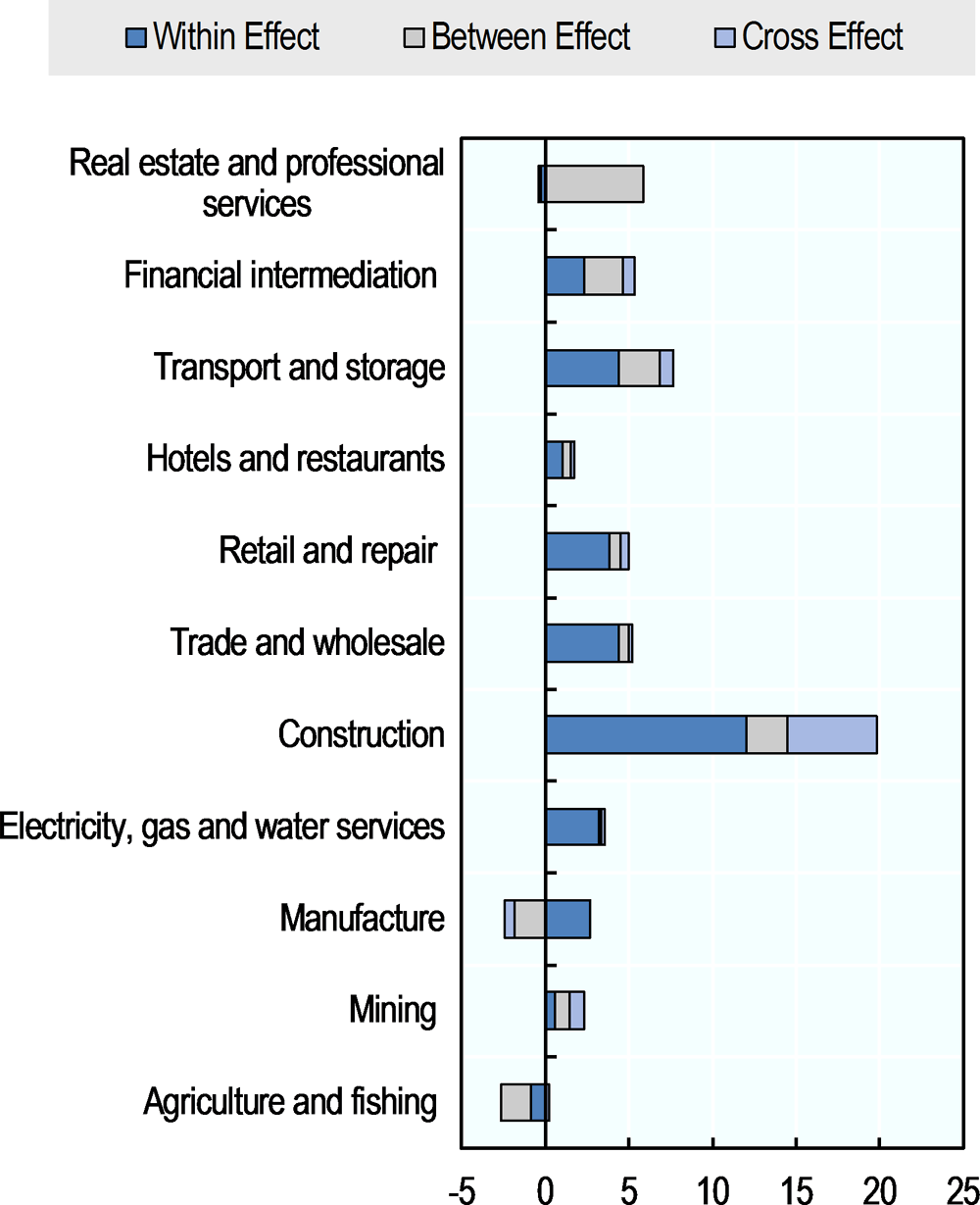

There are significant productivity gains to be realised through labour reallocations from less to more productive sectors as well as through endowing workers with better skills (Figure 2.14). Three of the five sectors that employ the largest shares of the population (retail and repair, agriculture and fishing, and manufacturing) are among the sectors with the lowest productivity. Although labour productivity in retail and repair –the largest employment sector in Panama– has increased, it still very low (43%) compared to overall labour productivity. Similarly, labour productivity in agriculture, livestock, hunting, forestry and fishing – which has dropped in the past decade – is only 16% of the average productivity, while the sector employed 14% of the workforce in 2016 – the second largest employment sector. In addition, labour productivity in hotels and restaurants is less than half the average productivity and has great potential in a country that has natural resources to serve as a worldwide vacation destination.

Figure 2.14. Productivity increases are led by within-sector growth with a few exceptions

Notes: The total change in productivity can be broken down into a within-industry effect, measuring the average yearly growth of output per employed person driven by technical change and capital accumulation; a between-industry effect measuring compositional shifts in sectoral shares of employment and relative price changes driven by reallocation of labour resources between sectors; and cross effect measuring the productivity gains which are driven by increases in the employment/market shares of firms whose productivity is increasing quickly, driven by the interaction between productivity changes and employment shares. In particular, the cross-sector effect represents the joint effect of changes in employment shares and sectoral productivity. This term is positive if, on the average, labour goes to sectors whose productivity is growing.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

Productivity gains in most major sectors in the past 13 years have been achieved with overall falling elasticity of job creation to economic growth. Figure 2.15 shows the growth in real gross value added, employment, and employment elasticity of growth across the sectors with the largest employment shares in the economy. The employment elasticity is a measure of the percentage change in employment associated with a 1‑percentage-point change in economic growth. It represents a convenient way of summarising the employment intensity of growth or sensitivity of employment to output growth. As such, it can indicate the ability of an economy to generate employment opportunities for its population – as a percentage of its growth process – as well as used to track sectoral potential for generating employment (Islam and Nazara, 2000). A positive employment elasticity of growth indicates that increased output is associated with increased employment. An elasticity lower than 1 indicates that output is growing more quickly than employment, signifying both increases in productivity and in employment.

Figure 2.15. Employment elasticity across selected sectors in Panama, 2003-16

Elasticity varies considerably across sectors ranging from transport and storage, which experienced the most job-friendly growth, to agriculture, which has seen a reduction of its workforce. Most of the big actors in the services sector, including construction, real estate, trade and wholesale, transport, storage and communications, have generally been employment intensive during the past decade. They have also experience falling elasticity since fast employment growth was accompanied by steady productivity growth. As a result, their job creation capacity is slowing down. These sectors have created considerably fewer new jobs since 2012 compared to what happened at the beginning of the 2000s. Greater employment generation in these sectors is crucial to benefit from the demographic dividend as well as to reduce informality.

Additionally, the trend in the manufacturing, restaurant and hotel sector, and transport and storage where elasticity is above 1 and growing, is a call to attention. Manufacturing, restaurants and hotels are among the sectors with the lowest productivity in the economy – below the aggregate average – and their employment shares are growing; a further fall in productivity could be a cause for concern. Fostering labour reallocation towards more productive services is therefore an avenue to increase overall productivity in the economy.

Overall, the aggregate employment elasticity estimates for Panama have increased during the period of fastest economic growth. It varied from 0.44 during 2003-07 to 0.51 during 2007-12 and back to 0.43 from 2012-17. This implies that for every 10% change in real GDP, there is about 4.3% change in employment. Going forward, although stepping up the employment intensity of growth would be hard since elasticity is close to 0.5, it is the relative cost of capital vis-à-vis labour and the nature of investment demand that will determine to what extent growth would be job-creating. On a rough basis, about 400 000 new workers will need a job in the next 10 years. If Panama’s employment intensity of growth stays constant the economy will need to grow at almost 6% GDP annually for the next decade to meet the demographic dividend.

Promoting value-added economic activities to generate sustainable growth and employment

The noted link between employment, informality and productivity levels, along with Panama’s economic structure, indicate productive transformation as a key policy area to promote more formal jobs in the medium to long term (OECD, 2017). Policies that favour formal job creation should be combined into longer-term planning, with a strong link to the broader national development strategy. Creating formal jobs requires the promotion of an economy which, from the supply side, has workers with higher levels of productivity and skills and, from the demand side, can create good-quality formal jobs to absorb those workers.

Panama needs to spur economic activities so that they overtake construction and allow the country to continue growing at a sustainable pace. The country should promote more complex economic activities in the provinces to help decentralise growth and make it more inclusive (Hausmann, Espinoza and Santos, 2016; Agosin et al., 2014).

On one hand, Panama could further upgrade and expand the service sector to new activities. There is a need to increase value-added in exports, and in particular the export of services, which remains the most important component in the export profile. While exports on services represent close to 95% of total exports, the services’ value-added generated for these exports remains low compared to benchmark economies. Transitioning from infrastructure-driven growth (i.e. investments in the housing market in Panama City, the Canal and Tocumen airport) to more diversified and knowledge-driven growth requires better and higher investments in innovation. Panama began to promote innovation and to invest in science, technology and research in 2004. Promoting innovation in a small, service-oriented economy such as Panama’s is challenging. The country has managed to increase domestic research capabilities and to introduce incentives to invest in innovation. Panama is still far from achieving the critical stage to improve its innovation capacities and to score well in traditional innovation indicators consistent with its level of development (see OECD, 2017).

On the other hand, Panama could invest in value-added regional manufacturing such as agro-industry products. Panama’s exported goods have “low complexity” and share few connections with more sophisticated products. Panama’s current export basket of goods is mainly composed of low-complexity products, which comprise close to 76% of goods. High complexity products amounted only to 5% (Hausmann, Morales and Santos, 2016). Moreover, the proximity of Panama’s current export basket of goods to more sophisticated goods is low. The basket of goods remains rather isolated, clustered around raw materials and far from capital-intensive activities, where the largest potential to develop new high-value-added products lies (Hausmann, 2012). An export basket of goods that relies on merchandise that is labour-intensive to produce, and uses low levels of technology and processing, creates few linkages with the rest of the economy. In turn, the lack of linkages limits the possibilities for incorporating further value-added into the exports (OECD, 2017).

The development of international tourism is another opportunity for Panama to consolidate a diversification strategy. Foreign tourism flows have increased at an average annual rate of 9%. The core of international tourism in Panama comes from the United States and neighbours Colombia and Venezuela, with 307 458, 307 076 and 235 023 registered visitors in 2015 from a total of 1 946 290 visitors, which represents almost half of tourism. Still, Panama lags behind benchmark countries such as Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic and Uruguay which had between three to six million tourists in 2016. The emergence of tourism as a promising sector should be developed hand in hand with both the strengthening of the modern tradeable service sector and positioning of the country as a logistics hub, which will provide the perfect air and water connectivity to foster broader international tourism and territorial development. The decentralisation of tourism-related activities remains an essential objective for the government in coming years. To this end an ambitious capacity-building programme is being implemented with local municipalities.

Additionally future benefits of the Canal and the tradeable service sector should expand to other sectors and regions to increase competitiveness and equity in Panama. The sectoral shifts and rising wages in the Canal cluster underscore a larger concern about loss of competitiveness and concentration of economic activities. In addition to rising labour costs, the rising prices of intermediate goods and labour will make the agricultural, manufacturing and certain service sectors less competitive. While the Canal is a fundamental source of high-quality jobs and high salaries, there is a risk of increasing the concentration of production and exports around it unless the Canal’s direct benefits and spillovers are further expanded in Panama.

The Plan Estratégico de Gobierno 2015-2019 (Government Strategic Plan 2015-2019) anticipates the Canal will diversify activities towards energy including generating electricity, exploiting the trade of liquefied natural gas and liquefied petroleum gas, and bunkering (GRP, 2014). The expansion may allow the development of hub-spoke economies (i.e. moving cargo from smaller to larger vessels for the longer hauls). Construction of shipyards in the Atlantic entrance of the Canal for post-Panamax ships is also foreseen, as well as carrying out top-off operations for ships that do not satisfy the draught restrictions.

Furthermore, investment in infrastructure beyond Panama City is particularly necessary given the country’s geography, increasing competitiveness and fostering of local tourism. At the same time new infrastructure projects in the provinces could open up profitable opportunities, generate employment and promote local economic development.

Boosting formalisation in independent workers and firms

Informality can take place either by election or by exclusion. Workers and firms may make a rational choice to operate informally based on a cost-benefit analysis. However, they may also be pushed into informality if the conditions and costs imposed by formality preclude it as an alternative, e.g. make the job unsustainable or the firm unprofitable (Perry et al., 2007). Three scenarios emerge based on cost-benefit rationales: 1) informality by choice, when both firms and workers perceive the costs of formality to outweigh the benefits; 2) informality for evasion, when firms remain informal, even if the benefits of formality outweigh the costs; and 3) informality by exclusion, when workers work informally, even if the benefits of formality outweigh the costs and they would be willing to assume those costs, because there are no formal jobs available (OECD, 2016a).

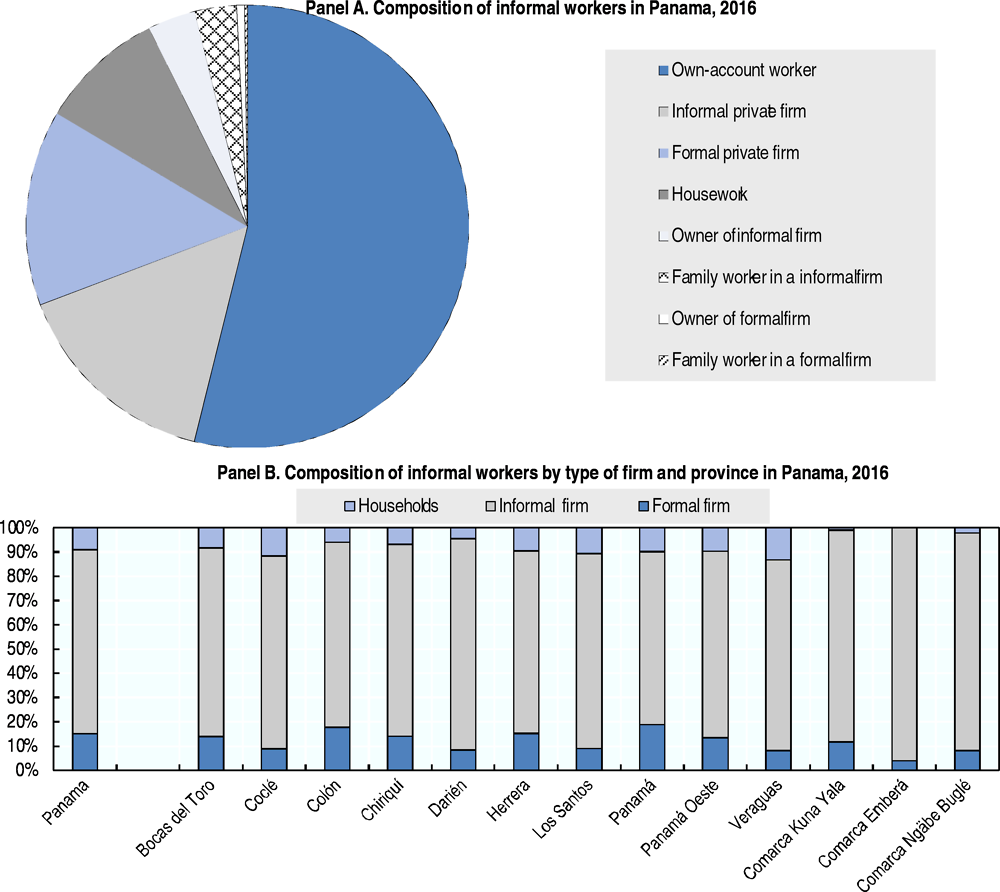

Labour informality is largely explained by self-employment and small informal firms

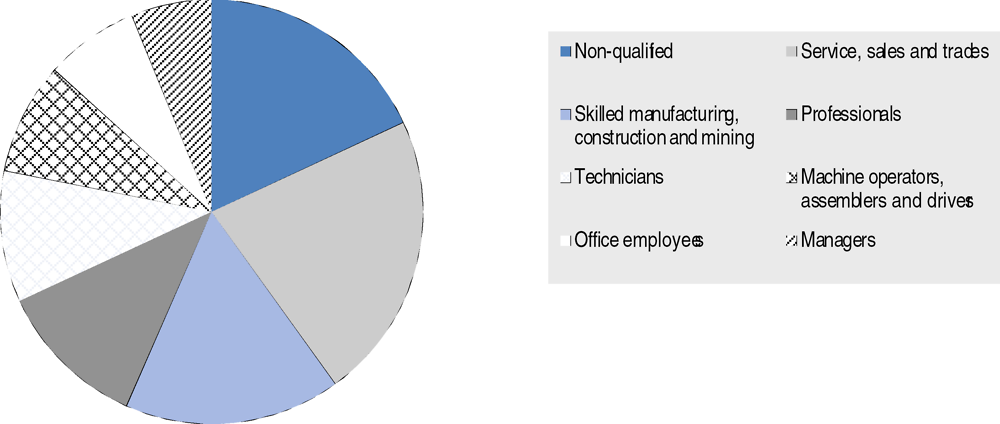

A significant share of informal employment in Panama is not voluntary and rather a necessity for most workers involved. One traditional explanation in the literature is that a large share of informal employment is the result of low levels of formal job creation and as a result many workers lack occupational alternatives. The self-employed represent by far the largest group of informal workers in Panama at 54% of total informal workers, followed by 15% of informal wage workers who work for informal firms, 14% of informal wage workers who work for formal firms and 9% domestic workers (Figure 2.16).

Figure 2.16. Composition of informal workers in Panama, 2016

Note: Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

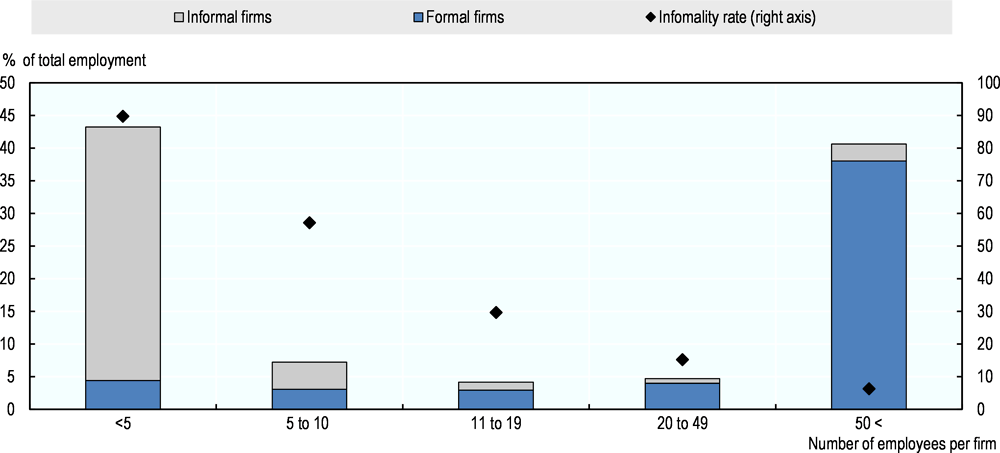

The labour market in Panama is also dual in terms of employment by firm size. Almost half of total employment in Panama is composed by informal workers in micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), especially dedicated to agriculture but also manufacturing, construction, commerce and transport, while most of the other half of the working population is employed in formal large firms: 43% of workers are employed in firms of less than 5 workers where informal rates are as high as almost 90%, while another 40% is employed in firms with more than 50 workers where most of the employment is formal (INEC, 2017) (Figure 2.17). In 2010, the first MSMEs survey done under the initiative for the Economic Inclusion of the Informal Sector in Panama (PASI for its acronym in Spanish) found that Panama has nearly 200 000 MSMEs that employ almost 430 000 workers, which means an average of 2.2 workers per MSME (CNC, 2010).

Figure 2.17. Employment composition and informality by firm size in Panama, 2016

Note: Legal definition of informality: workers are considered informal if they do not have the right to a pension when retired.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC.

Almost half of the MSMEs have only one worker and constitute a quarter of the employment generated by the sector. Two–worker companies constitute 21% of MSMEs and generate 19% of employment; companies with 3 to 5 workers represent a quarter of the MSMEs and generate almost a third of the sector’s employment. MSMEs with 6 to 20 workers account for 6% of the total number of companies and 24% of employment (CNC, 2010).

Labour informality is extremely high among MSMEs and firms show different levels of compliance. Only 11% of all MSMEs pay the social security quota for all its workers and 9% pay for only some workers; while 59% of companies do not pay social security for any workers. Yet, 21% of the MSMEs employees have social security for other circumstances, for example, they are covered by the social security of their families or are pensioners (CNC, 2010).

Labour informality among MSMEs goes hand in hand with firm informality. PASI identified bottlenecks that MSMEs face to register and operate formally. As such, they classified companies by five main types of informality: (i) those that do not register workers at the Caja de Seguridad Social (CSS –- Social Security Agency) Social Security Agency (68%); (ii) those that do not pay for workers’ social security (79%); (iii) those that do not have a single taxpayer registry (67%); (iv) those that lack an operation permit (66%); and (v) those that lack the local government/municipality permit (60%). Only 6% of all MSMEs2 comply with all requisites (CNC, 2010).

A large number of informal MSMEs serve as subsistence employment for poor and vulnerable women. The majority of most informal business owners have had poor access to education – 27% did not complete secondary, 20% only finished primary school, and 15% had no education. Additionally, there is a strong gender bias in the sector: 57% of informal businesses are owned by women and 32% are owned by men, while only 10% are owned jointly. It is important to highlight that most business owners felt they made more money under the informal sector, which is particularly important as their enterprises represent between 75-100% of their household income. Their vulnerability is most evident through the fact that 40% of PASI-surveyed enterprises were unable to gain financing due to lack of collateral and are highly indebted to informal forms of finance. Moreover, almost 40% of informal business owners had previously owned an informal business, demonstrating a systemic and long-term trend (CNC, 2010).

Recent efforts to curb informality in MSMEs have focused on firm registration and have had limited results. Although there has been a lot of work done by Autoridad de la Micro Pequeña y Mediana Empresa (AMPYME – MSME Authority), few MSMEs are formal. In fact, Panama has put in place a number of measures to foster the formalisation of firms. These include a portal to ease the creation of a firm – Panamá Emprende –, training services, and fiscal incentives, such as access to financing and a two-year exemption from income tax for new micro firms with a turnover cap of PAB 150 000 (Law No. 33 of 2000) which covers over 100 000 firms. Firms in this scheme are included in a special registry that also grants them access to a number of other support services provided by AMPYME. Still, some firms, especially small and medium firms, have benefited from little reduction of overall formalisation costs.

The incorporation of productive units under Law No. 33 of 2000 is too broad. The main objective of this law is to establish a regulatory regime to promote the creation, development and strengthening of MSMEs, which it clearly defines. Medium-sized firms are defined as firms with turnover of between PAB 1 million and PAB 2.5 million. The inclusion of such firms under the small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) umbrella is debatable and can cause difficulties in the implementation of SME policy since firms with a turnover of around PAB 2 million have very different registration and operating constraints than firms with a turnover of PAB 150 000.

Moreover, innovative legislation passed in 2013 that would enable the incorporation of microenterprises and facilitate tax requirements has not been implemented. Law No. 132 of 2013, which regulates the creation of limited liability microenterprises, could also serve as a productivity-enhancing tool since it forces microenterprises to separate firm bookkeeping from household accounts.

A reason why MSME legislation has not been more effective in reducing labour informality among MSME workers is that the efforts to facilitate the inclusion of MSME workers in the social protection system has not been implemented. There have been no developments between the CSS and the institutions supporting MSMEs to foster labour formalisation. Although Law No. 33 states that the CSS and AMPYME should seek the massive incorporation of own account workers and MSME employees in the social security system, little has been done to create the appropriate mechanisms to promote labour formalisation that is financially sustainable for MSMEs and especially for independent workers. Neither Panamá Emprende nor the SME registry are explicitly linked to social security, nor to any of the special regulations for SMEs, including the payment of social security contributions, which are handled by the CSS. Moreover, the limited liability microenterprise law does not incorporate any stipulations to facilitate pension savings for owners and employees.

Simplify the tax burden for MSMEs and independent workers

MSME taxpayers of low fiscal significance in Panama undoubtedly constitute the most difficult sector to control and formalise. For the purposes of their identification and the design of a tax regime that recognises their taxpaying capacity and needs, they should be distinguished by i) their economic magnitude and ii) their economic activity. In terms of economic magnitude it is important to differentiate owners, independent workers and employees since the formalisation constraints they face are different and so is the proper policy response.

Panama could implement a simplified tax regime open to individuals, single-owner firms and micro units. This regime could encourage micro producers and retailers to become formal through the payment of a small monthly fee contingent on the level of annual sales being less than PAB 150 000 – which represents 96% of micro and small enterprises and accounts for 82% of the employment of the sector (CNC, 2010). At the same time the CSS should adapt its contribution quotes for independent workers both in terms of frequency and payment method and enforce the mandatory contribution of independents to the CSS in order to reduce labour informality and ensure that all workers have pension savings.

A simplified tax and pension scheme could serve as an attractive and efficient way to formalise independent workers – also called single-person microenterprises. Simplified regimes reduce the administrative burden and make it easier for low-income, informal taxpayers to comply with both the tax and social security regime by paying several taxes – such as the sales tax, pension and health insurance – in a single payment. The primary objective of its implementation is not to increase the collection of taxes but to reduce the regressive effect of compliance costs for small firms, avoiding overburdening the tax administration with a large number of small taxpayers whose revenue collection is very limited. At the same time, by including pension contributions it reduces the fragmentation derived from the contributory schemes of the formal/informal labour market, and promotes universal coverage of the population in the health and pension dimensions of social protection.

Earlier experience in Latin American countries shows that simplified regimes for small taxpayers should favour simplicity over equity of the system. As such, the fixed-fee system by category appears as the more advisable system since it does not require firms to fill out a complex and detailed income tax form. Categories should be defined by gross revenue or turnover in conjunction with a secondary parameter such as physical magnitude, number of employees or electricity used, as well as to distinguish between economy activities. Special regimes that are exclusively based on revenues or turnover encounter several operational problems since revenues and billing are difficult to control at such small scales. At the same time, relying solely on income can perpetrate the so-called “fiscal dwarfism” effect, forcing companies to stay small so as not to have to pay higher taxes. Finally, it is very important that simplified regimes be updated regularly (González, 2006).

Box 2.4. The simplified tax regime in South America: A labour formalisation tool

In the face of persistent informality among small taxpayers, Argentina and Brazil together with most South American countries developed simplified tax regimes to incorporated self-employed workers and microenterprises into their tax registries. Although these schemes are different among countries, they facilitate the payment of one or more taxes and ensure a minimum level of social protection (pensions for old age and/or health) to a large number of small taxpayers.

The Argentine Monotributo is a simplified tax regime that ensures independent workers and microenterprises comply with their tax obligations. In a single monthly payment it concentrates workers’ obligatory payments for social security contributions (health insurance and pension savings), income tax and value-added tax of the goods and services sold. Payments fees are fixed according to 11 presumptive categories defined on each individual worker or microenterprise’s turnover, number of employees, square metres of land used, electrical energy consumed and rent. Moreover, payments are differentiated among workers and firms that provide services from those that sell goods.

The eligibility requirements of the Argentine Monotributo are simple. Any independent microenterprise or co‑operative worker with a maximum of 3 members can register under this scheme if their annual gross income is lower than ARP 1 050 000 (around USD 52 000) for those selling goods or ARP 700 000 (around USD 35 000) for those providing services. Additionally, independent worker, microfirm or co‑operative cannot register under this scheme if they sell imported goods, or goods have a per unit price higher than ARP 2 500 (around USD 125).

Similarly, the Simples and the Sistema de Recolhimento em Valores Fixos Mensais do Tributos do Simples Nacional (SIMEI) schemes replace multiple tax obligations with a single payment in Brazil. The former is especially designed for MSMEs and the latter for independent workers up to an annual turnover cap of BRL 60 000 (around USD 16 500). Under the Brazilian corporate legislation, microenterprises are defined as those that have an annual gross income equal to or lower than BRL 120 000 (around USD 33 000) and small enterprises as those that register an annual gross income higher than BRL 120 000, but equal to or lower than BRL 1 200 000 (around USD 330 000).

Simples is a progressive tax based on firms’ monthly gross revenue, firms’ activity and tax on industrialised products (IPI) contribution, which offers lower rates compared to the payment of all them separately. This regime allows the unified collection of municipal, state and federal taxes replacing the payment of the corporate income tax, social contributions on net profits, social contributions paid by companies, contributions for social security financing, IPI, tax on the circulation of goods and interstate transportation services (ICMS), tax on services (ISS), and employer’s social security contribution. In addition, MSMEs under the Simples regime are exempt from paying several taxes including the contributions to social services such as Sesc, Sesi, Senai, Senac, Sebrae and the employer’s syndicate contribution.

Likewise, SIMEI replaces the federal income tax from Simples for a fixed monthly fee. SIMEI payments are composed by the social security contribution (5% average minimum wage), a flat fee of BRL 5 for the state tax ICMS and a flat fee of BRL 1 for the municipal tax ISS. Simples and SIMEI also provide access to benefits such as support for maternity, illness and retirement, among others.

All three schemes promote registration and financial inclusion. While Simples and SIMEI allow registration in the National Registry of Legal Entities, which makes it easier for enterprises to open bank accounts, make loan applications and issue bills; the Monotributo offers a one-month payment refund to independent workers and microenterprises that comply with all monthly payments during a calendar year using debit or credit cards.

Facilitate the operation of formal businesses

Panama should extend the use of methods to incorporate SMEs as well as contribute to reduce firms’ operating costs related to formalisation. Although the creation of Panamá Emprende encourages the registration of firms in Panama by introducing a computer system that automates, facilitates and reduces the time and costs of opening a new business, it does not simplify or reduce administrative and operational costs for SMEs. Efforts should be made to make AMPYME’s’ unique registry a useful tool for MSMEs. Registration in Panamá Emprende does not result in the automatic granting of benefits. Regularly updating the registry’s information as well as linking it to all the benefits enumerated in Law No. 33 of 2000 is essential to prevent the registry from becoming an extra administrative burden for MSMEs. Additionally, AMPYMEs could work on alternative ways to reduce the compliance costs of operating formally by analysing the costs and procedures MSMEs face while operating among different economic activities and regions, as well as working on ways to reduce barriers to MSMEs’ access to international goods and capital markets.

Panamá Emprende should serve as a tool to facilitate municipal licensing. Panamanian MSMEs need several municipal licensing levels and administrative procedures in order to operate. Some of these are costly, but mostly they are another level of bureaucracy for MSMEs. To relieve MSMEs from such burdens, the existing Panamá Emprende one-stop shops and online portal could be used for licensing procedures at both local and national levels. This would result in better co‑ordination among national and local administrations in terms of business regulation, and also help to reduce red tape and recurrent costs associated with formal status.

Establish a clearer and simpler system to determine minimum wages

Panama has a complex minimum salary matrix. Every other year the government of Panama institutes a new minimum salary matrix though executive decree. The matrix is fixed by the national government following the advice of the Minimum Wage Commission and details the salary adjustment according to region, economic activity and size of the firm. The 2017 matrix lists 81 different hourly minimum wages that range from 1.53 to 3.47 PAB per hour. The agricultural sector has the lowest minimum wage and SEZs and airport workers the highest one.

Most of the minimum wages have increased at similar rates since the late nineties. This indicates that aggregate considerations dominate over sectoral or firm-level productivity considerations, generating a general increase of salaries. In practice, the evolution of minimum wages sets a floor to the evolution of sectoral minimum wages, which may erode competitiveness in certain industries. The reliance on national negotiations to set sectoral minimum wages is a symptom of the weakness of collective bargaining in the country.

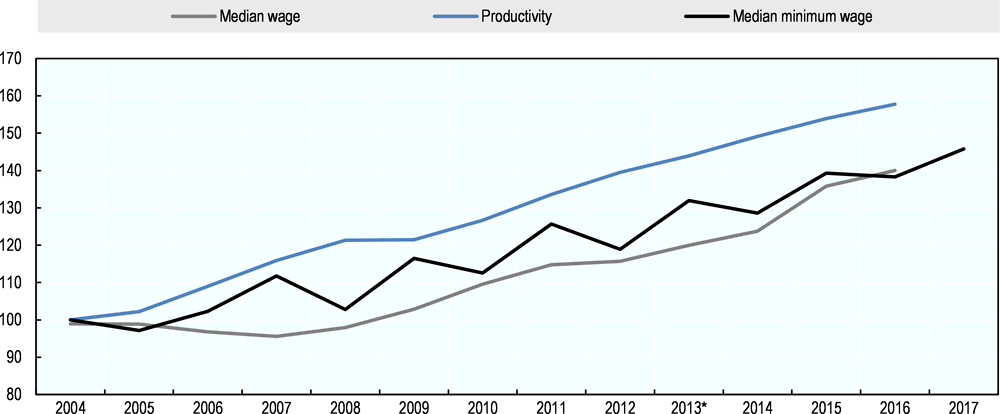

Over the past decade, aggregate labour productivity growth in Panama has been coupled with the growth in salaries. Figure 2.18 compares growth in aggregate labour productivity (real value added per worker) with two measures of real labour compensation: national real median wage and the median of all minimum wages for urban regions. From 2004 to 2012, the minimum wage growth followed closely the growth in productivity. Yet, since 2012 it has fallen slightly below productivity. Conversely, median wage growth fell below productivity growth from 2004 to 2007 and corresponded closely to productivity from 2008 through 2016. This comparison suggests that increasing productivity appears to raise real wages for the typical worker in Panama. However, this is not the case for all workers in all sectors.

Figure 2.18. Evolution of productivity and wages in Panama

Note: Labour productivity is measured as the annual value added (the value of output less the value of intermediate consumption) per employee. The median minimum wage represents the median of all minimum wages for region 1.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC and Ministry of Economy and Finance.

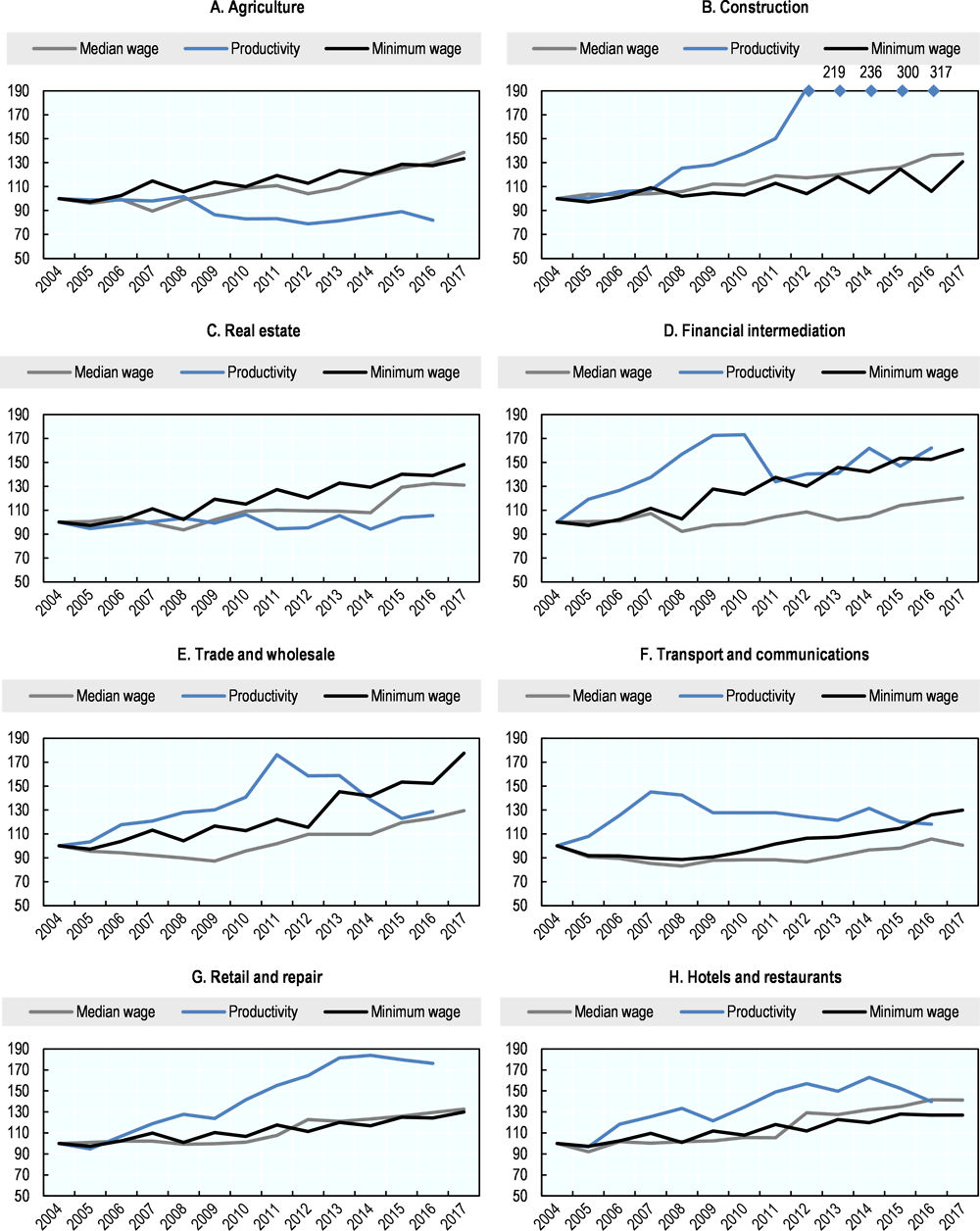

At the sector level, labour productivity growth in most sectors has decoupled from real median compensation growth. In the tradeable service sector, productivity and wages follow very different paths (Figure 2.19). In fact, in trade and wholesale, and transport and communication, for example, productivity fell after an initial spike, while wages continued to increase. This suggests that firms were not able to adjust wages to respond to the fall in productivity. Instead, they adjusted the quantity of employment as explained earlier in this chapter. On the contrary, in the non-tradeable service sector, where informality is more pervasive, wage growth remained significantly below productivity growth, implying that raising productivity is not sufficient to raise real wages for the typical worker in these industries. Both patterns suggest that there is a role for public policies to ensure that productivity gains are better shared in some industries, while not eroding competitiveness in other industries.

Figure 2.19. Evolution of productivity and wages in Panama by sectors

Notes: The minimum wage for primary activities was calculated as the simple average of all minimum wages for workers in agriculture, livestock, hunting, forestry, aquaculture and fisheries; the minimum wage for transport and communications is the average of the minimum wage for workers in transport within SEZs, waterways, aerial and complementary activities, ports, international airports, storage, deposit and mail, as well as workers in telecommunications and network maintenance; the minimum wage for retail and repair is the average of the minimum wages of workers in both small and large retail and repair firms; the minimum wage for hotels and restaurants is the average of the minimum wages of workers in small and large hotels and restaurants. The minimum wage for real estate is the average of the minimum wages of workers in real estate, rental and business activities. Labour productivity is measured as the annual value added (the value of output less the value of intermediate consumption) per employee by sector.

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by INEC and Ministry of Economy and Finance.

A clear and simple scheme to determine minimum wages is easier to implement and monitor. Complex minimum wage systems offer flexibility to tailor the evolution of the minimum wage to the conditions in each sector. However, more complex minimum wage matrices are more difficult to communicate, enforce and monitor, and require higher institutional capacity on the part of the state. In fact, they require that the members of a minimum wage board understand the characteristics of all the sectors, firms and regions. Thus, systems that are overly complex, like the one in Panama, tend to lose their effectiveness (ILO, 2017). While the minimum wage sets a floor informed by technical criteria, it should be distinguished from collective bargaining, which can be used to set wages above an existing floor. In the long run, strengthening collective bargaining at the firm or sector level would make the current complex matrix unnecessary. As working conditions would be negotiated between workers and firms and/or sectors, salaries would better reflect productivity changes guaranteeing both workers and firms profit from them.

Reduce the cost of formally hiring low-income workers

Labour supply and demand decisions are affected by taxation. Tax systems might deter employment by either diminishing the after-tax wage of employees, or increasing the employer’s labour costs (OECD, 2011a). From an employee’s perspective, larger net personal tax average rates (defined as the tax/benefit proportion of the gross wage an employee pays/receives after taking into account all mandatory income taxes and social security liabilities and cash transfer benefits) and net personal marginal tax rates (defined as the proportion of an additional unit of wage-earning income that is paid in respect of taxes and social security contributions net of additional benefits) provide greater incentives to reduce the worker’s labour supply and/or entry to the labour market. The latter is especially true for second earners. When the tax unit is the individual, the loss of tax allowances and credits on the basis of family income can discourage second earners’ labour market participation (OECD/CIAT/IDB, 2016).

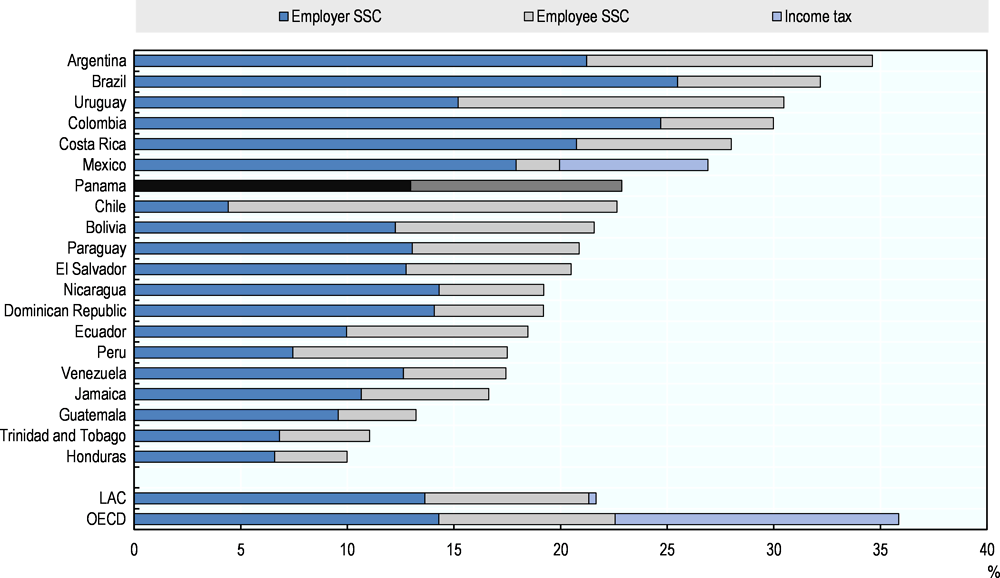

Panama’s tax wedge, a measure of the difference between the labour costs and an employee’s take-home pay, is similar to that of other Latin American economies. The tax wedge on average wage earnings in Panama is 22.9% of total labour costs. This is 1.2 percentage points higher than the average in LAC countries (21.7%) but lower than the OECD average of 35.9% (Figure 2.20). The tax wedge includes compulsory social security contributions (SSCs), which for employees are 9.9% and for employers 13%. No personal income tax is paid on an average wage. While these figures are similar to those for the region they contrast with the significant income taxes paid by average wage workers in OECD economies (OECD/CIAT/IDB, 2016). On average, the higher the tax wedge, the more costly labour becomes.

Figure 2.20. Income tax plus employee and employer social security contributions, 2013

Source: OECD/CIAT/IDB (2016), Taxing Wages in Latin America and the Caribbean, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262607-en.

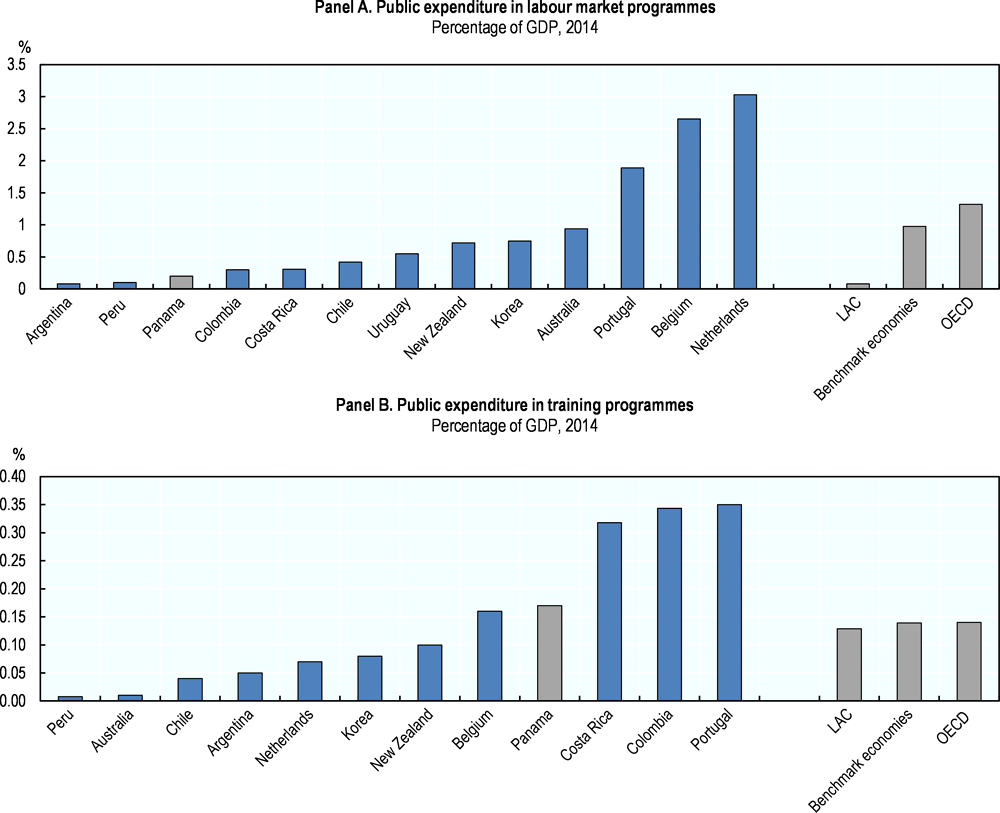

Formalisation costs from labour taxes do not explain informality for most workers in Panama, especially those in the upper three quintiles of the income distribution. Overall, higher informality rates among wage earners do not relate to higher formalisation costs in Panama. This is a distinctive feature that differentiates Panama from the rest of the region. Theoretical formalisation costs are defined as the proportion of workers’ income that grants them access to health care and pension savings. The interaction of average income levels and the existence of a legally mandated lower earning threshold to participate in these social security programmes increase their price in most countries in Latin America. Yet, the existing earnings threshold in Panama is low relative to reported income, making the formalisation cost for individuals proportional (23% of the worker’s income) throughout the income distribution. On average, other factors might influence an individual’s or employer’s choice between formality and informality. These might include job security; labour regulations (i.e. monetary and non-monetary registration costs, firing costs, vacations); the value a person places on the programme or services; expectations of receiving future benefits; and a component of myopic behaviour by the individual or employer.