This chapter explores how regional development can be a lever to help Panama continue on its growth trajectory and achieve more inclusive socio-economic outcomes. It discusses Panama’s current multi-level governance architecture, identifying where it should be strengthened to better support the design and implementation of regional development policy. In addition, it evaluates the need for a more strategic approach to regional development and greater capacity in subnational finance, institutional co‑ordination, and quality public service delivery, at all levels of government. A special focus is placed on Panama’s local authorities in light of specific resource challenges and the 2014 decentralisation reform. Finally, the chapter looks into what would be necessary to achieve a strategic shift towards a “place-based” policy approach for regional development, and provides recommendations for action.

Multi-dimensional Review of Panama

Chapter 3. Strengthening regional development policy to boost inclusive growth

Abstract

Regional development is a policy lever for sustainable and inclusive growth in Panama. To better meet national objectives of sustained development with greater inclusiveness, a number of territorial challenges should be addressed (OECD, 2017a). These include ensuring more equal access to public services across regions, reducing the level of labour market informality, and strengthening the mechanisms that can finance development. A regional development strategy that is built around the unique and competitive attributes of each region – a “place-based” approach – supported by effective multilevel governance mechanisms could help Panama achieve more inclusive socio-economic outcomes.

This chapter is dedicated to exploring regional development as a policy lever for Panama to better meet its sustainable growth and inclusiveness aims, and focuses on the need to improve strategic planning and implementation frameworks. It begins by reviewing Panama’s multilevel governance structures as they relate to regional development, explores the benefits associated with a “new paradigm” approach, and identifies multi-level governance tools, particularly with respect to co‑ordination, that could strengthen institutional capacity to realise regional development aims. It concludes with a series of recommendations for regional development.

Why a national-level regional development policy matters

A national level policy establishes the guiding principles for decision making and action with respect to a specific sector (e.g. education, transport, energy) or a multisector concern (e.g. regional economic development, labour markets, social inclusion). In a regional development context, the purpose and value of a national regional development policy is several fold. First, it sets the guidelines for decision making and action in a complex, multistakeholder policy area. Second, when well designed, executed and monitored, a national-level regional development policy can help align priorities and build greater coherence and complementarity among the various actors involved, particularly since sector priorities and approaches may differ among them. When regional development is approached in terms of a policy package (rather than individual sector interventions), there is less potential for the unintended and undesirable effects that can arise when policy measures are undertaken in isolation (OECD, 2012). Third, it facilitates capitalising on cross-sector policy synergies that can better promote inclusive and sustainable growth.

Regional development is a key multisector policy area that promotes well-being and economic prosperity. Taking a regional perspective, including an aim to promote growth in all regions, rather than focusing on high or low performance regions, is likely to yield economies that are less vulnerable to external shocks (OECD, 2012). At the same time, there is increasing agreement that the quality of governance structures (institutions and frameworks) plays a significant role in the ability to generate sustained increases in wellbeing and economic prosperity (EC, 2017a). Regional development policy contributes to inclusive and sustainable growth by acting as a framework for action at the national and subnational level.

Approaches to regional development in OECD countries

Investing in regions, including the less-performing ones, is beneficial for sustainable growth. While there is no question why governments should invest in regions that are engines of growth, policy makers and the public can question why it is just as important to invest in regions that are less dynamic. Regions that underperform can be costly to national budgets. Missed growth opportunities go hand in hand with lower tax revenues, and ensuring adequate public service delivery can be very expensive. In addition, if the decline is not reversed, political pressures can lead to expensive policies dedicated to sustaining communities and living standards through transfers, which in time can lead to conflict (particularly as wealthier regions tire of paying for such support) (OECD, 2012).

Shifting from an approach that focuses on transfers and subsidies as generators of wellbeing and growth to one that concentrates on identifying and building the productive potential of each region can contribute to regional dynamism and national inclusive growth (OECD, 2012). Over the past few decades, OECD countries have done precisely this, using regional development policy to promote more integrated and market-oriented approaches in order to solve national growth challenges. This has resulted in a “new paradigm” driving the design and implementation of regional development policy (Table 3.1), where effort and resources are concentrated on building competitive regions by bringing together actors and targeting key local assets rather than ensuring the redistribution from leading to lagging regions (OECD, 2009a; OECD 2009b).

Table 3.1. Old and new paradigms of “place-based” regional development policy

|

Action |

“Old” Paradigm |

“New” Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

|

Objectives |

“Balancing” economic performance by compensating for spatial disparities |

Tapping underutilised regional potential for competitiveness |

|

Strategies |

Sector-driven approach |

Integrated development projects |

|

Tools |

Subsidies and state aid |

Development of soft and hard infrastructure |

|

Actors |

Central government |

Different levels of government |

|

Unit of territorial analysis |

Administrative regions |

Functional regions |

|

Focus |

Redistribution from leading to lagging regions |

Building competitive regions by bringing together actors and targeting key local assets |

Source: OECD (2009b), Regions Matter: Economic Recovery, Innovation and Sustainable Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264076525-en.

The goal of regional development policy is to ensure that different types of regions are able to thrive and offer a high quality of life for their residents (OECD, 2016a). Introducing such a policy in and of itself will not automatically generate growth or inclusiveness. It serves as a framework to guide the implementation of sector and cross-sector policies and programmes that can – in the short, medium and long term – contribute to the performance of a country and its regions. It needs to be complemented not only by effective sector policies that support infrastructure, labour markets, and innovation, but also by effective multilevel governance structures – the institutions and frameworks supporting relationships, decision making, and implementation processes between national and subnational levels of government, including subnational development planning.

Panama’s multilevel governance structures supporting regional development

The design and execution of regional development policy relies heavily on the successful interaction of multiple levels of government, government sectors, actors and interests. It must align national and subnational objectives and priorities, and its implementation depends on the capacity, including human, financial, and infrastructure endowments, of all levels of government. Its success also relies on empowered, accountable, and properly resourced subnational governments, both regional and local. Panama’s multilevel governance structures (i.e. the institutions and frameworks) that support regional development are centralised and top-down, not fully able to promote a “place-based” or “new paradigm” approach. This is further limited by the minimal role that subnational governments play in the country’s economic and social development.

Panama’s territorial administrative structures

Panama is a presidential republic of over four million inhabitants. Compared to OECD member countries, it is similar in population to Ireland, New Zealand and Norway. In total area it is slightly smaller than the Czech Republic. It is a unitary country with two levels of government established constitutionally: national and municipal. At the subnational level, administration is divided into two administrative tiers, with municipalities divided into submunicipal units (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Panama: Subnational administrative bodies

1. Within the context of the decentralisation law and in order to ensure government transfers, Panama counts 78 municipalities with the 78th municipality being the combination of three comarcas: Madugandí, Wargandí and Guna Yala.

2. Panama’s three comarcas have a total of 2 073 populated areas broken down as follows: Kuna Yala (117), Emberá (82), Ngäbe Buglé (1 874). The two indigenous groups that are embedded in provinces, Kuna de Wargandí and Kuna de Madungandí, have 5 and 23 populated areas, respectively. Note that for these last two areas, data is in anticipation of the census in 2020, for the others data is from February 2018.

Sources: Adapted from: OECD (2017a), Multi-dimensional Review of Panama: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278547-en; editorialox (n.d.), “Panama” available: http://www.editorialox.com/panama.htm; Data for indigenous settlements provided by Panama from INEC (National Institute of Statistics and Census of Panama).

Provinces are deconcentrated entities of the central government. Each is led by a presidentially appointed governor and administered by a Junta Territorial composed of representatives from each line ministry. An indirectly elected Provincial Council1 acts as an advisory body to the governor. Provinces do not have revenue-generating capacity, and are responsible for implementing the plans and programmes developed by the national government. Comarcas with provincial status are semi-autonomous, and have traditional, “communal” structures (Box 3.1). They can generate their own revenues, often from tourism, fishing, and crafts that are transferred into a community treasury or fund. Other comarca revenues come from state transfers and from remittances to family by community members living and/or working outside the comarca.

Each province is divided into autonomous municipalities (distritos), which themselves are divided into subunits – corregimientos. Municipalities are led by democratically elected mayors and have municipal councils comprised of two representatives from each corregimiento.

Box 3.1. Comarcas: Panama’s indigenous territories and communities

Approximately 12% of Panama’s population is a member of one of seven indigenous groups. The majority live either in one of three semi-autonomous comarcas or in indigenous territories embedded in provinces. Combined, these territories cover about 24% of the country’s total land mass. Functioning as collectives, the communities are governed by local leaders. Additionally, there are 10 General Congresses and two General Councils, representing the maximum authority for the indigenous population of Panama. Comarcas are represented in Panama’s National Congress. Each comarca has its own organic (constituting) law, which recognises the right of the communities to hold collective property (within the comarca), and contains specific references to natural resources, government, justice, economy, culture, education, and health. While not always the case, poverty levels are generally higher and wellbeing outcomes are generally lower in the comarcas than in Panama’s non-indigenous provinces.

Sources: UNDP (2014), Imaginando un Futuro Común: Plan de Desarrollo Integral de los Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá, United Nations Development Programme, New York, available http://www.pa.undp.org/content/panama/es/home/library/poverty/sistematizacion-plan-desarrollo-indigena.html; OECD (2017a), Multi-dimensional Review of Panama: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278547-en.

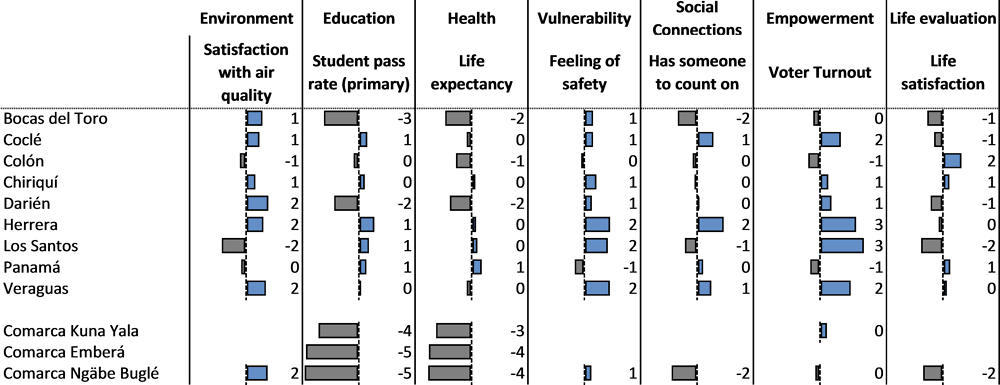

First-tier outcomes and growth patterns can reinforce territorial disparities

There is a large gap between provinces and comarcas in terms of wellbeing outcomes. Residents of comarcas are much more likely to live in poverty and report lower levels of satisfaction about their living conditions. They are also at greater risk of having an informal job, or not having access to drinkable water in their dwelling. The lowest level of electricity coverage in Panama is among the indigenous population. However, low outcomes in material and living conditions are also evident in the provinces as well, generally those that are rural, and regardless of whether they have a high percentage of indigenous residents (Figure 3.1) (OECD, 2017a).

A strategic approach to regional development, supported by a policy for its implementation, can help mitigate a risk of ad hoc growth and development, and better ensure the ability to successfully address inequalities. Projections indicate that provincial population growth between 2010 and 2020 is expected to range from a low of 1.6% in Los Santos, to 33.5% in Bocas del Toro. The population of Panama City is expected to increase by over 20% in this same 10-year period, a growth level also expected of the three comarcas2 (Controlaría del Gobierno de Panamá, 2010). In light of this, there are two points that should be underscored. First, the population is expected to grow most in some of the least-advantaged territories, where quality of life/wellbeing outcomes are already low, particularly in the comarcas, Bocas del Toro, and Los Santos (OECD, 2017a). Second, Panama City is also expected to grow significantly and the challenge will be to ensure adequate infrastructure, housing, amenities, and service delivery capacity to keep up with growing demand, while also maintaining or improving quality of life. While appropriate spatial and land-use planning is fundamental to meet the challenges represented by such growth, they complement and contribute to a regional development policy; they do not replace it.

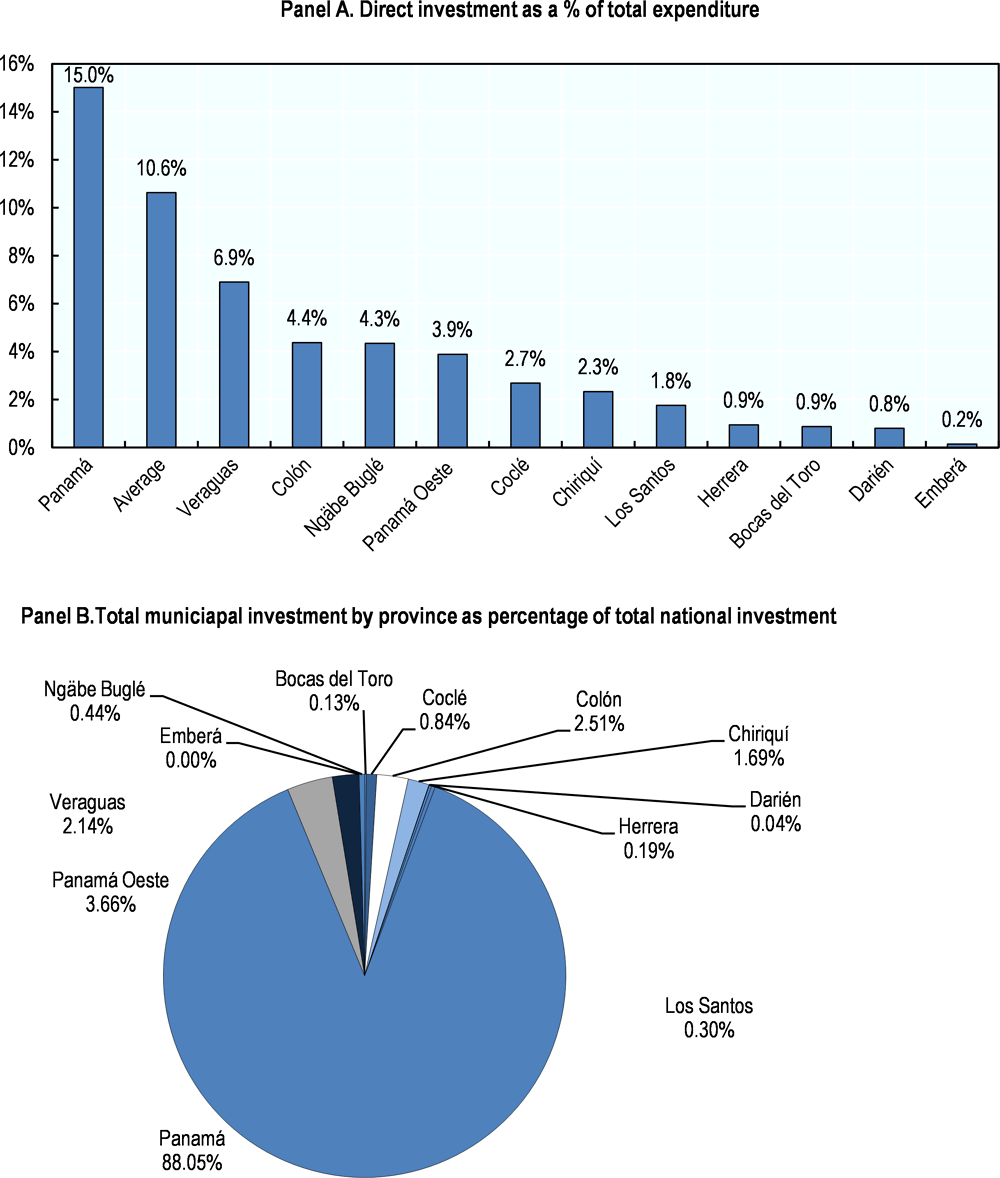

Figure 3.1. Quality of life by regions

Notes: This analysis looks at the original province of Panamá, although Panamá and Panamá Oeste recently split. Z-score or standard score stands for the signed number of standard deviations by which the regional outcome is above or below the national average. This normalisation enables an assessment of how much a region’s performance is deviating from that average.

Source: OECD (2017a), Multi-dimensional Review of Panama: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278547-en.

Normative and institutional frameworks for the subnational level

Territorial administration is governed by a series of laws, some of which date to the 1970s, and others which were recently introduced. These include the Constitution; Ley N9-106 Sobre Regimen Municipal from 1973 which establishes municipal categories, autonomy and structure; Law No. 37 of 2009 Que Descentraliza la Administración Pública – Panama’s first decentralisation law; and Law No. 66 of 2015 Que Reforma la Ley 37 de 2009, which updates and amends Law No. 37 of 2009. In addition, a national policy for land use with a horizon to 2030 (Política Nacional de Ordenamiento Territorial), together with an action plan establishing priorities, is under preparation by the Ministry for Housing and Land Use (Ministerio de Vivienda y Ordenamiento Territorial).

Planning frameworks for regional development could be better targeted

Regional development in Panama is guided by successive government programmes, currently the Plan Estratégico de Gobierno 2015-2019 (PEG) (Box 3.2). The document outlines the president’s objectives and approach for the country’s development, including at the subnational level. It is implemented by sector-driven projects and programmes. However, this plan does not guide regional development in the long term. Rather, regional development is a central level process guided by government strategies that are limited to a period of five years. Implementation depends on the plans of each line ministry, as well as the articulated needs of local authorities that emerge from provincial government bodies. Panama is also developing a 12-year national development plan, the Plan Estratégico Nacional con Visión de Estado – Panamá: 2030, which can be a valuable longer-term strategic document to embed broader national objectives, although it does not specifically refer to regional or territorial development.

Box 3.2. The territorial dimension to Panama’s Government Strategic Plan, 2015-2019

In the current government programme – the Plan Estrategico de Gobierno 2015-2019 (PEG) – the overall ambition is to promote greater sustainability and equality, increased competitiveness and more effective investment throughout the country. In order to achieve this, the PEG calls for a national “master plan” for land use and territorial development supported by a new legal framework, greater citizen and business participation in territorial and urban interventions, and building institutional capacity at all levels of government. It includes a section dedicated to modernising the public sector that focuses on public finance and investment effectiveness, as well as on taking a more strategic approach to public management, promoting civil service reform, and advancing the decentralisation agenda.

Source: Gobierno de la República de Panamá (2014), Un Solo País: Plan Estratégico de Gobierno 2015-2019, Gobierno de la República de Panamá, Panama, available: http://www.mef.gob.pa/es/Documents/PEG%20PLAN%20ESTRATEGICO%20DE%20GOBIERNO%202015-2019.pdf

There are several concerns with this approach to regional development planning and implementation. First is the lack of a link to a larger strategy, one built using longer-term strategic foresight, solid evidence bases, and which establishes clear outcome objectives. This means that there is limited guidance for decision making and action by line ministries and their relevant agencies, and little that can be used to support monitoring, evaluation and government accountability. Second is the limited time horizon (five years) for implementation – it corresponds to one presidential term and is not tied to a longer term vision or investment strategy (OECD, 2017a). This is particularly challenging as the concrete results stemming from a strategically-based regional development policy can take longer to materialise. Third, there is no requirement that sector plans be binding in terms of implementing regulatory or investment policies to achieve objectives set in the government plan (OECD, 2017a).

OECD and non-OECD countries use a variety of mechanisms to ensure their regional development strategies have a longer-term dimension, and link to sector and subnational planning. For instance, some countries use a legal framework to support strategic regional development planning and implementation at a central or subnational level. This is the practice in Finland (Act on Regional Development, 2014), Slovenia (Law on the Promotion of Balanced Regional Development), Switzerland (Federal Law on Development Policy, 2006), and Ukraine (Law on Fundamentals of State Regional Policy, 2014) (OECD, 2016b; Verkhovna Rada, 2015) while others use white papers (e.g. Australia, UK), state strategies for regional development (e.g. Sweden) or other framework documents such as state-region planning contracts (e.g. France) or regional growth programmes (e.g. New Zealand) specifically dedicated to the task (OECD, 2016b). In addition, some countries dedicate funds to regional development planning in their national budget codes or through dedicated special funds.

At the subnational level, development planning instruments are gradually being introduced and focus on the municipal level. Article 13 of the original law on decentralisation (No. 37) included a hierarchy of planning instruments, beginning with the government plan, followed by a national land-use plan, provincial development plans, municipal development plans and finally ending with corregimiento development plans (República de Panamá, 2009). As the law was suspended and then reintroduced, this planning hierarchy appears to have been modified. The amended decentralisation law requires municipal development planning in the form of district strategic plans (Planes Estratégicos Distritales – PED). These are combined development and land-use plans (República de Panamá, 2015) that are intended to link back to the Strategic Government Plan 2015-2019 (PEG) and the National Strategic Plan 2030 (Plan Estratégico Nacional con Visión de Estado-Panamá: 2030). Prior to this, it is reported that local level development planning was under the responsibility of the central government, based upon identified needs that were communicated upward by local authorities, and for which the central government would design the corresponding plan.

Institutional responsibility for regional development is fragmented

Responsibility for regional development is fragmented across sectors in Panama. The Ministry of Economy and Finance (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas – MEF), and specifically its Direction for Public Policy, and Department for Regional Planning within the Direction for Investment Programming, play important roles. Line ministries with a territorial logic, such as the ministries of Agriculture, Education, Employment and Labour Force Development, Health, Housing and Land Use, Social Development, and the Vice-ministry for Indigenous Affairs, as well as relevant agencies, are also involved, realising their objectives through a variety of plans and programmes. In addition, the Ministry of Government and its Department for Planning and International Co‑operation also have a hand in the cross-sector co‑ordination of subnational initiatives that support productive development. Finally, the Secretariat for Decentralisation will likely play an increasingly visible role with respect to local development and development planning.

This institutional framework underscores two issues. First, responsibility for regional development is highly fragmented, within institutions as well as among actors across sectors. Second, there is no government body exclusively dedicated to regional development in terms of its design, implementation, co‑ordination, monitoring and evaluation. When confronted with this degree of fragmentation, institutional co‑ordination becomes fundamental and inter-ministerial co‑ordination is an important ingredient for success, given the complexity and cross-sectoral nature of regional development policy.

Centre-of-Government (CoG) bodies are often responsible for ensuring co‑ordination across government, for instance in the area of regional development. Cross-government co‑ordination committees, in turn, can delegate the oversight of the policy’s implementation to a specific ministry, which can be vital to success. In Panama, however, the level of influence that the CoG has over line ministries to encourage co‑ordination is relatively low – limited to expressing its views rather than potentially executing sanctions. Also, there appears to be limited to no responsibility on the part of the CoG to organise cross-government policy co‑ordination committees. Panama together with Paraguay belong to the few countries in the region where this is the case. In the others, there is responsibility for such organisation on at least one level (OECD, 2016c).

In sum, regional development in Panama could be strengthened through more targeted normative and institutional frameworks. Currently, two frameworks lead the regional development process, the PED and the Law on Decentralisation, the implementation of which are supported by the individual strategies and plans of line ministries and other government bodies. A dedicated national regional development policy could help bring these pieces together and ensure continuity over the medium term (see sections below).

Generating regional level growth depends on greater subnational capacity

Panama’s subnational governments face financial challenges and constraints in administrative and management capacity that can limit successful regional development and the implementation of place-based plans and programmes. The law on decentralisation could help address these, however it is in its early stages and so it is too soon to assess its real or potential impact.

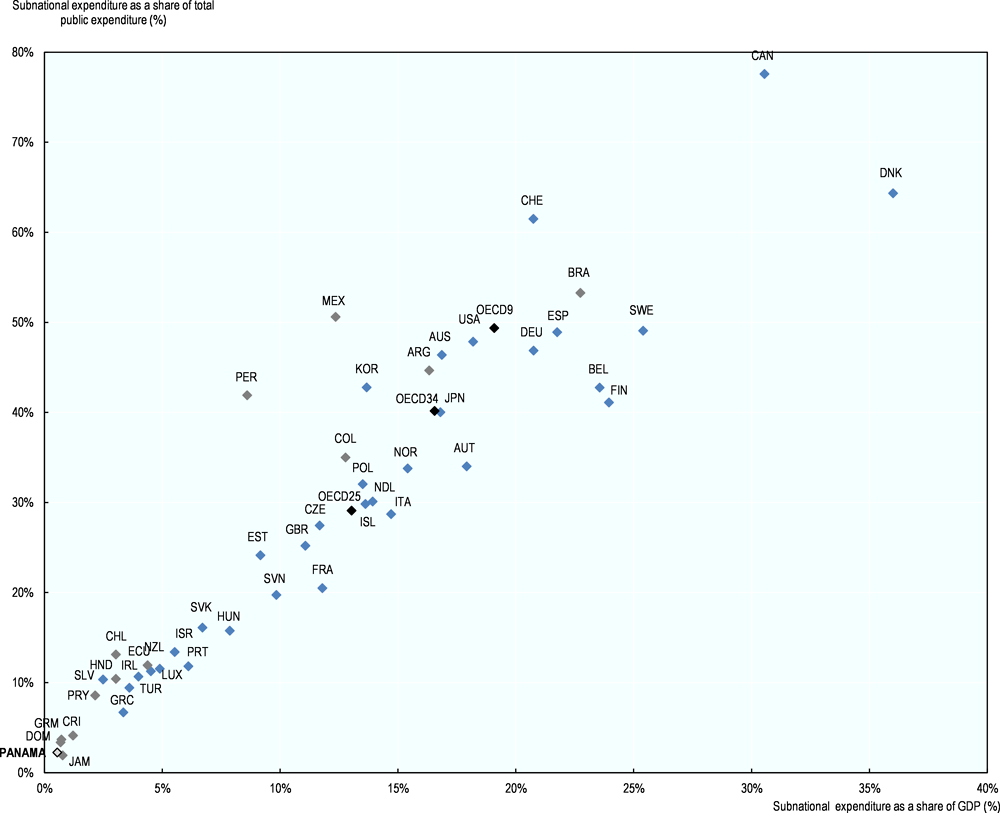

Subnational fiscal and financial frameworks

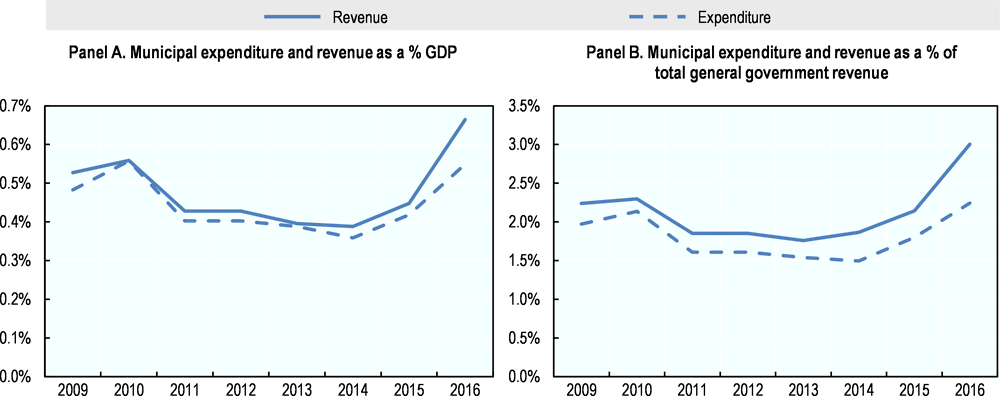

As currently structured, Panama’s financing and investment frameworks do not easily support a “place-based”, regionally-driven approach to development. This is true at the provincial and municipal levels, where governments play a limited role in public expenditures, supposing a high degree of centralisation (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Subnational government expenditure is low in Panama (2014)

Notes: Data for Panama are for 2016. Subnational government calculations for Panama reflect expenditure by municipalities and Juntas Comunales, because provincial expenditure is counted as part of central government expenditure. Panama is highlighted in bold, Latin American countries in grey, OECD countries in blue.

Source: OECD calculations from Contraloría General de la República – Dirección General de Fiscalización, Municipalidades de la República y Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas Dirección de Presupuesto de la Nación (DIPRENA); OECD (2017b), Making Decentralisation Work in Chile: Towards Stronger Municipalities, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279049-en.

Provincial frameworks

Provincial governments have no own-source revenue, and their expenditures are financed directly from the central budget. Their fiscal frameworks are limited to the immediate budget year (i.e. there is no multi-annual budgeting), and are frequently not formula based. Instead, line ministries are responsible for financing their sector’s subnational responsibilities, and funds are assigned annually after the ministries have defined their budgets with the Ministry of Economy and Finance. Once funds are allocated, each sector redistributes funds down the line (i.e. to the province and from there to specific areas such as schools or hospitals) based on identified local needs and projects. Funding gaps arise, and if there are insufficient funds one year, then programming waits until the next year’s budget round. Panama’s time span for fiscal projections is up to five years – a time span common to a majority of Latin American and Caribbean countries. There is no requirement for the budget to be based on long-term fiscal projections – as practised by 70% of countries in the region – nor must it take demographic change into account (OECD, 2016c). Fiscal projections can be useful for identifying future expenses in light of expected demographic and economic change, and can contribute to the reform agenda (OECD, 2016c).

This approach to managing provincial fiscal and investment funds can challenge sustainable regional and local development. Provincial authorities have little to no discretion over the use of funds in a cross-sectoral manner since budgets are handed down by the line ministry and kept within the corresponding sector. However, in some cases, such as healthcare, recent changes allow a degree of interchangeability within a sector which is a step toward greater fiscal decision-making autonomy at the provincial level. What this means for regional development, though, is that funds are limited unless the associated development programming is sector driven, or a special budget or fund for regional development is allocated by the central government. It also makes a “place-based” approach more challenging as provincial governments are limited in their ability to prioritise spending needs and act accordingly.

Municipal frameworks

At the municipal level, the picture is somewhat more complex, as there is no particular legal framework that regulates central level transfers to municipal governments (World Bank, 2013). These are often left to presidential discretion. In addition, central government transfers do not have standard frameworks, such as rules or formulas. This lends a degree of unpredictability to transfers, thereby contributing to a lack of budget predictability among local authorities (World Bank, 2013).

However, municipalities can generate own-source revenue from fees, fines and taxes (e.g. municipal taxes, tax on alcoholic beverages, and on livestock [abattoirs], which is paid to the municipality of the animal’s origin), income from public lands, properties or municipal assets; duties on the extraction of a variety of natural resources (e.g. wood, sand, stone, clay, coral) and on public performances (e.g. concerts) (Gobierno de Panamá, 1972/2004). Despite their autonomous status, however, municipalities have few attributed responsibilities. Those that they do have are heavily concentrated on general urban amenities and education with some additional services in public health, transport, recreation and culture (Annex A) (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, 2002). This links to the limited weight of municipalities in general government expenditure, estimated at 2.2% in 2016, representing around 0.5% of GDP (Figure 3.3). This is significantly different from the OECD average where municipal governments represent 40% of public expenditure and 17% of GDP. It is also far from many other Latin American countries.

While municipal revenue levels remain low, they have been rising since 2014 (Figure 3.3), as a result of the reintroduction of the Law on Decentralisation. In addition, municipal revenue is starting to grow faster than expenditure, which may reflect the impact of the law’s injection of funding for investment that has not yet been matched by an increase in the level of responsibilities that require spending. Despite these upward trends, however, Panama’s municipalities generate very limited revenue and have low expenditure levels as a percentage of GDP and as a percentage of total general government revenue. In Chile, for example, one of the OECD’s most centralised countries, subnational government revenue represented 3.6% of GDP and 15.5% of general government revenue in 2016 (OECD, 2017c), compared to Panama’s 0.7% of GDP and 3.0% of general government revenue.

Figure 3.3. Municipal expenditure as a percentage of GDP and total general government revenue

Source: OECD calculations from Contraloría General de la República – Dirección General de Fiscalización, Municipalidades de la República y Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas Dirección de Presupuesto de la Nación (DIPRENA).

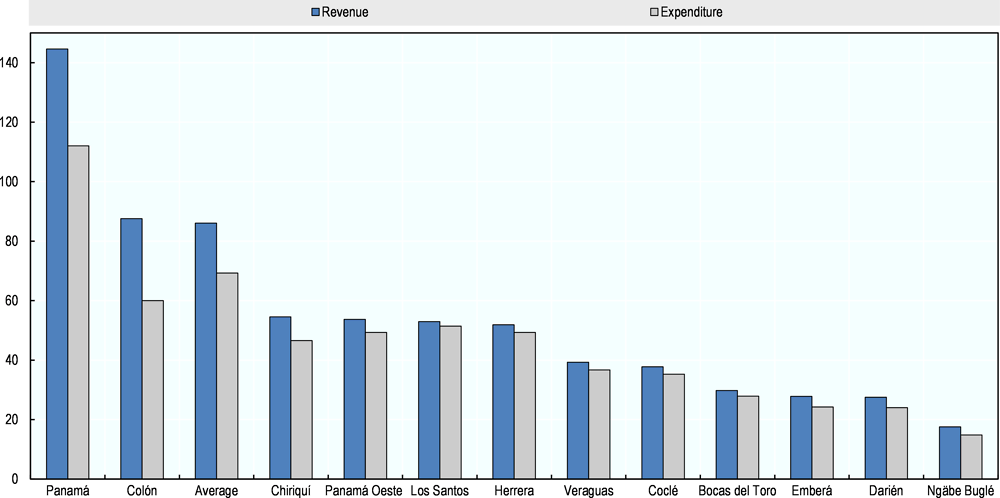

Despite these positive shifts in municipal financing, municipal expenditure is unevenly distributed across municipalities. For example, municipalities in the province of Panamá were responsible for 62% of all municipal expenditure in 2016, underscoring large differences in the ability of local authorities to deliver quality public services and effectively administer a municipality. Disparities are also evidenced by municipal expenditure per capita, which in 2016 ranged from an average of PAB3 14 in the communities of Ngäbe Buglé to an average of PAB 112 in those located in the province of Panamá (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Per capita municipal revenues and expenditures, 2016 (USD)

Source: OECD calculations based on data from Contraloría General de la República –-DIPRENA.

Overall, Panama’s expenditures per capita are extremely low compared to other economies (Table 3.3). On the one hand, this reflects the limited number of services and other responsibilities ascribed to local authorities, and on the other hand the limited amount of income generated by municipalities.

Table 3.3. Municipal expenditures per inhabitant are low, 2016

|

Country |

Municipal expenditures |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

per inhabitant (USD) |

as % GDP |

As % general government expenditure |

|

Panama |

70 |

0.5% |

2.2% |

|

Chile |

648 |

3.0% |

13.0% |

|

Greece |

894 |

3.3% |

6.7% |

|

Turkey |

706 |

4.0% |

11.0% |

Note: PAB 1 = USD 1.

Sources: OECD calculations based on data from Contraloría General de la República – DIPRENA; OECD (2017c), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (brochure), www.oecd.org/regional/regional-policy (database: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en).

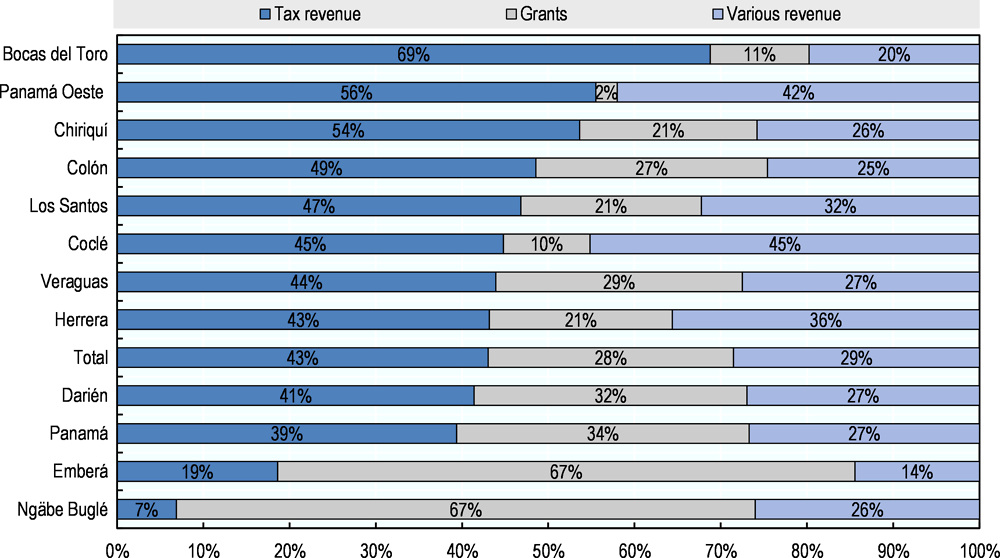

Of importance to regional – and local – development is the ability for subnational governments, including municipalities to invest. In 2016, 11.6% of municipal expenditure, on average, was dedicated to direct investment in infrastructure and large facilities. This is a level close to the OECD average (11.2%). This ability among Panamanian municipalities is relatively new, as in 2012 and 2015 direct investment accounted for only 4% and 6% of their expenditure, respectively. There are, however, large disparities across municipalities. In three provinces (Herrera, Bocas del Toro, Darién) and one comarca (Emberá), direct investment represented less than 1% of municipal expenditure in 2016 (Figure 3.5, Panel A). In the same year, among the municipalities located in Panamá province direct investment represented 15% of municipal expenditure and overall accounted for 88% of total municipal direct investment (Figure 3.5, Panel B). It should be remembered, however, that the share of municipalities in total public direct investment remains extremely low – 1.6% compared to the OECD average of 59.3% (Contraloría General de la República, 2018). Overall, municipal investment is very low, and concentrated mainly in Panama City.

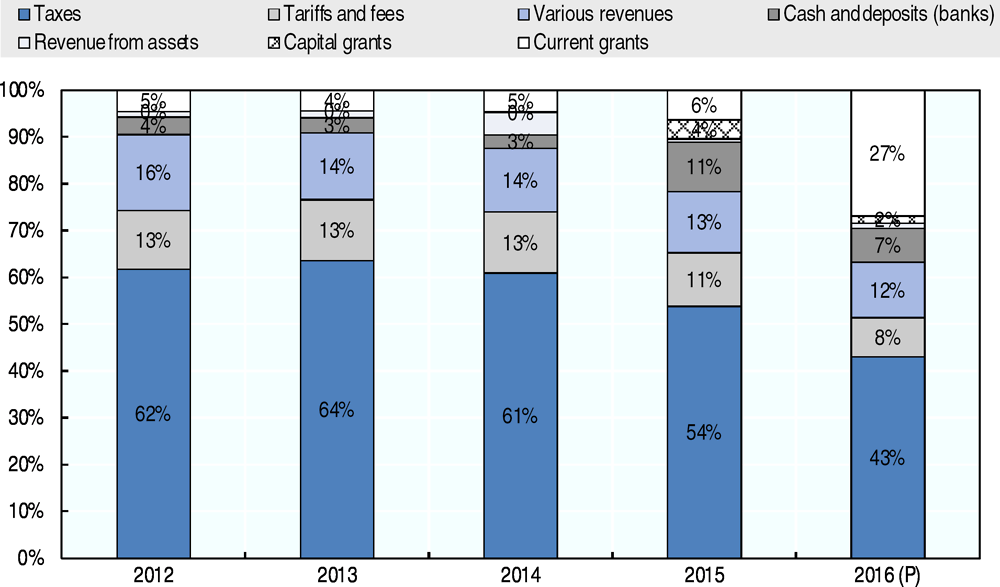

Figure 3.5. Investment at the provincial level (2016)

On the revenue side, taxes are the main source of municipal income. While since 2014, and especially 2015, municipal revenue has been increasing as a percentage of GDP and total general government revenue (Figure 3.4), taxes have decreased as a share of municipal revenue since 2015 when municipalities started to receive grants linked to the decentralisation reform (Figure 3.5). The result is a significant increase in the weight of grants, and especially current grants, in municipal budgets. On the one hand, this can mean that the proportion of municipal budgets generated by taxes and other own-revenue sources is declining, thereby limiting fiscal autonomy. Central government transfers are often linked to specific uses, while own-source revenue can be used at municipal discretion and is associated with greater spending autonomy. On the other hand, it also means a more diversified and, in this case, balanced financing system for local authorities.

Figure 3.6. Changes in municipal revenue 2012-2106

Note: 2016 figures are projected.

Source: OECD calculations from Contraloría General de la República –DIPRENA.

In addition to disparities among municipalities in terms of expenditure levels, there are also disparities in terms of revenue generation (Figure 3.6). For instance, while in Ngäbe Buglé only 7% of municipal revenues came from taxes, in Bocas del Toro, taxes represented 69% of municipal revenues. Meanwhile, grants contributed only 2% to the revenues of Panamá Oeste’s municipalities, but 67% to the communities of Ngäbe Buglé. This can signal a significant discrepancy in the capacity to raise revenue, and also indicates highly different degrees of dependence on central government support.

The province of Panamá and its municipalities are the leading generators of municipal revenues – accounting for 65% of total municipal revenue in 2016. They also received 77% of all central government transfers, and accounted for 59% of municipal tax revenue in 2016. This creates a territorial disparity in terms of financial resources that can be translated in differences regarding the quality of public services provided.

Figure 3.7. Municipal revenue by category in 2016 (%, provincial level)

Municipal administrative and management capacity is constrained

As autonomous entities able to generate own source revenue, local authorities are expected to cover their operating and administrative costs, as well as deliver services and invest in development. However, this does not appear to be the case for the majority. It is currently estimated that 77% of Panama’s municipalities are receiving state subventions for operating and administrative costs. In some provinces all or all but one municipality require support from the central government (AMUPA, unpublished). This challenge can be linked to various factors including size (population and territory) and demographic makeup – those with higher levels of poverty, and/or a lower percentage of an active population in the formal labour market – will have greater difficulty generating sufficient resources to meet their operational costs.

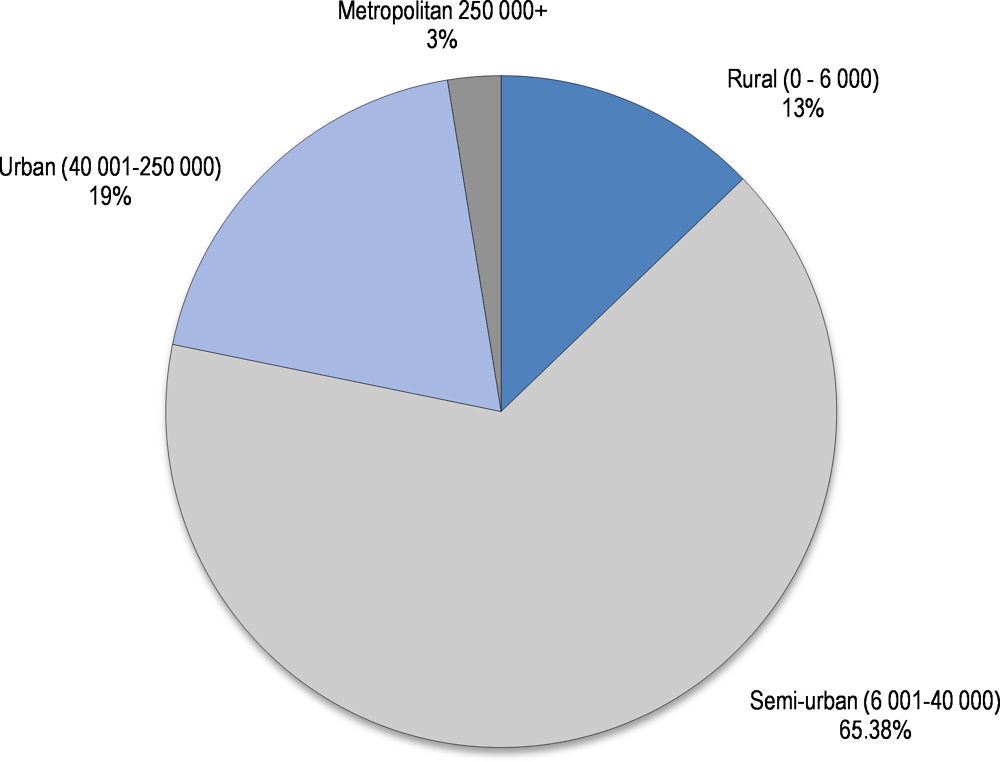

A population imbalance across municipalities can further impact disparities in municipal capacity, including in management and administration, service delivery and development planning. While municipal (administrative) fragmentation appears to be limited in Panama, population levels are not evenly spread across the territory, and thus there is a certain degree of imbalance.4 This is reflected, at least in part, by the discrepancies in revenue and expenditure between Panama (city and province) and other parts of the country.

Panama’s system of municipal classification may be compounding territorial disparities at the local level and contributing to resource challenges. Panama’s four-category classification of municipalities5, identifies the bulk of municipalities as semi-urban (51 in total), with an additional 10 being rural, 15 urban, and two metropolitan (Figure 3.7). However, this system may not reflect each territory’s actual economic and social dynamic, which can undermine the ability to develop territorially appropriate policies and plans, and to identify the actual costs of service delivery as well as opportunities for revenue generation. A functional area analysis often more accurately captures the economic, social and connectivity factors contributing to a territory’s productivity.

Figure 3.8. Population levels in each category of municipality (2010)

Note: Data from 2010, last official census.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Controlaría del Gobierno de Panamá (2010), “Boletín 16: Estimaciones y Proyecciones de la Población Total del País, por Provincia, Comarca Indígena, Distrito y Corregimiento, según sexo y edad: años 2010-2020”, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo, Panamá, Panama, available at:

https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=10&ID_PUBLICACION=556&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=3.

The classification system raises two concerns with respect to regional development. First is the large percentage of rural plus semi-urban municipalities (79%). This can exacerbate intermunicipal and interregional disparities based on revenue generation capacity, and affects capacity and outcomes in municipal delivery. In addition, if one considers the differences in minimum wage paid in urban versus rural municipalities, the system may be supporting segregation between urban and rural communities (see Chapter 2). Ultimately, this undermines greater inclusiveness.

The second concern is the subdivision of municipalities into smaller units, the corregimientos. Submunicipal administrative units are more frequent in countries with very populous municipalities, such as Ireland, Korea, Japan, New Zealand or the United Kingdom, where average municipal populations range from a low of almost 70 000 in New Zealand to a high of almost 223 000 in Korea (OECD, 2017c; OECD, 2017d). Panama certainly has populous municipalities. However, these are not the majority and corregimientos are characteristic of all municipalities, not just the larger ones. This can fragment municipal decision making, as each corregimiento has its own leadership. Corregimientos are represented on the municipal council as well as on the provincial council (Consejo Provincial), giving them a fair amount of representative power. This is not negative but the co‑ordination mechanisms within municipalities need to be sufficiently strong to ensure adequate and effective prioritisation and decision making across the municipal territory.

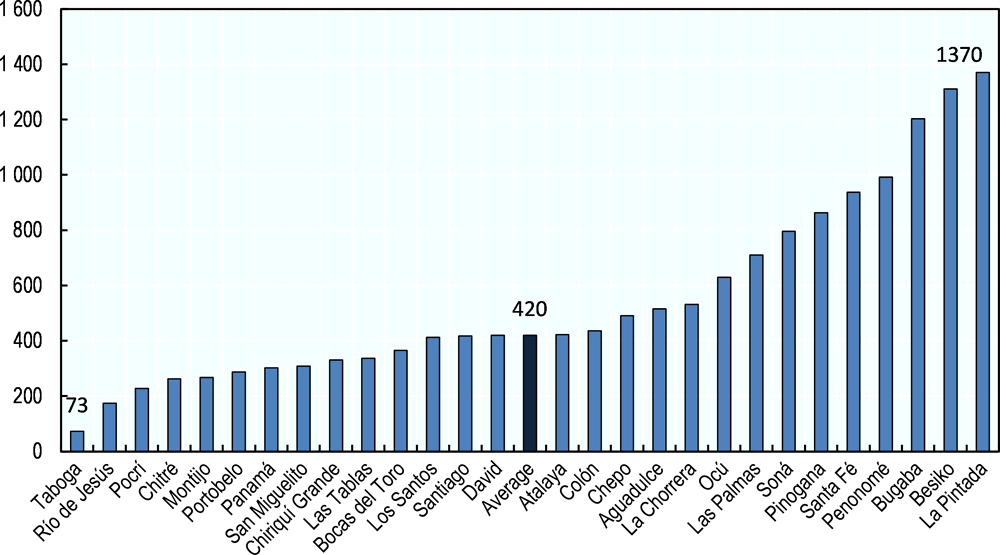

Municipal administrative and management capacity is also challenged by human resource limitations. This is evidenced first by the number of inhabitants per municipal staff – on average there are 420 people per civil servant. However, as with financial capacity, there are significant disparities – ranging from a ratio of 73:1 in Taboga to 1 370:1 in La Pintada (Figure 3.8). Low staffing levels could reflect the limited tasks assigned to municipalities, of the difficulties to meet administrative costs which then limits hiring, and also of a skills gap, i.e. an inability to recruit staff with the necessary skills.

Figure 3.9. Number of inhabitants per municipal staff member, 2013

Note: For reasons of legibility, this figure is limited to a representative sample of municipalities and provincial capitals.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the national statistics office.

Sufficient financial capacity is needed to guarantee the high skills of public servants. The law on decentralisation (discussed below) stipulates that all municipalities must employ a municipal engineer, a legal advisor, an administrator, a planner, a person responsible for citizen services, and a person responsible for municipal services. This should address some specific capacity issues. However, it may not be enough if the quantity and variety of responsibilities increase with the advancement of the decentralisation process. Thus, sufficient financial capacity will be fundamental to ensure that remuneration levels are appropriate to recruit subnational public servants with the right skills and experience.

Panama’s Law on Decentralisation

Decentralisation is a tool that contributes to realising national and subnational government objectives by transferring a range of powers, responsibilities and resources from central government to elected subnational governments in three interconnected areas (OECD, 2017d):

Political decentralisation: involves a new distribution of powers (including how subnational administrators are selected) with the objective of strengthening democratic legitimacy.

Administrative decentralisation: involves a reorganisation and clear assignment of tasks and functions between territorial levels to improve the effectiveness, efficiency and transparency of national territorial administration.

Fiscal decentralisation: involves delegating taxing and spending responsibilities to subnational tiers of government. The degree of decentralisation depends on both the amount of resources delegated and the autonomy in managing such resources (e.g. decisions on tax bases, tax rates and the allocation of spending).

Decentralisation can more actively involve subnational authorities in the development of their territories, while also building accountability for performance, quality and results. In addition to the “traditional” reasons for introducing decentralisation6, some countries, such as Chile and Mexico, use decentralisation reforms to fight against poverty and large territorial disparities, or to preserve historical, linguistic and cultural specificities (e.g. in Belgium, Finland, Italy, Spain and the UK). There is also some evidence that countries with more devolved spending responsibilities tend to have a higher GDP per capita (OECD, 2017d).

Panama’s Law on the Decentralisation of the Public Administration (the Decentralisation Law) as amended is intended to build municipal capacity so that local authorities can better assume municipal development and service responsibilities (Box 3.3). It establishes the administrative structure for comarcas and local governments. In addition, the law requires municipalities and comarcas to develop PED. These plans are to link directly to the relevant sections of the PEG. The law also increases municipal funding by establishing two municipal level investment funds and foresees a gradual transfer of responsibilities once it is determined that municipalities have been accredited by the Secretariat for Decentralisation and show they have the capacity to meet such responsibilities.

Box 3.3. Panama’s Laws on the Decentralisation of the Public Administration

Law No. 37 of 2009 on the Decentralisation of the Public Administration (Ley No. 37 Que Descentraliza la Administración Pública) was introduced in 2009. It defines the principles and objectives of decentralisation and local governance, establishes categories of municipalities according to population and density, foresees a development planning hierarchy, classifies, defines and lists the responsibilities to be delegated to local authorities, and establishes a multistakeholder, autonomous government entity to oversee the process. It takes a gradualist approach to decentralisation, permitting the transfer of competences to local authorities once their competence has been accredited, and they have completed an application process. This law was suspended by the subsequent government before it was fully implemented.

In 2015, Law No. 66 was passed, updating and amending the original legislation. Law No. 66 maintains the gradualist approach and the concept of accreditation before assignment of responsibilities. However, it amends the original law (Law No. 37) with the objective of improving local investment capacity by supporting the Ministry of Economy and Finance’s capacity to collect property and real estate tax, create an intermunicipal solidarity fund, target investment funding, improve citizen participation and transparency and promote local development and land-use planning. In addition, Law No. 66 stipulates the responsibilities that can be attributed to municipalities funded by resources from the collection of the property and real estate tax. Broadly these include: maintenance and improvement of education, healthcare, recreation, and sports facilities; basic public services to homes (e.g. aqueducts, street lighting, waste management and recycling services); infrastructure for public safety; construction and maintenance of social service facilities; construction and maintenance of infrastructure for tourism and culture; construction and maintenance of infrastructure for socio-economic development (e.g. urban and public infrastructure, water landings, municipal markets, infrastructure for municipal microenterprises, and support for the agricultural sector).

Sources: República de Panamá (2009), Ley No. 37 Que Descentraliza la Administración Pública, República de Panamá, Gaceta Oficial Digital, Panama, available at: http://www.organojudicial.gob.pa/cendoj/wp-content/blogs.dir/cendoj/ADMINISTRATIVO/ley_37_de_2009_que_descentraliza_la_administracion_publica.pdf; República de Panamá (2015), Ley No. 66, Que Reforma la Ley 37 Que Descentraliza la Administración Pública, República de Panamá, Gaceta Oficial Digital, Panama, available at: https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/27901_A/GacetaNo_27901a_20151030.pdf.

Panama’s decentralisation process is just getting started. However, care will need to be taken that it does not fall short of its intentions in three critical ways.

First is the limited extent of fiscal autonomy it appears to offer. The financial capacity component of the reform provides municipalities with two investment-financing sources. The first fund derives from the property and real estate tax. Of the funds transferred into this investment budget by the central government, urban municipalities can use 90% for investment in hard infrastructure in areas outlined by the law (e.g. public works such as roads, lighting, water, electricity, etc.) and municipal services (see Box 3.3) and 10% for increasing their administrative budgets. All other classifications of municipalities can dedicate 75% of the funds for investment in hard infrastructure and 25% for administrative capacity (República de Panamá, 2015). The intention of this fund is twofold. First it aims to give municipalities more opportunity to finance development projects, particularly in infrastructure; and second it is a way to support local authorities which have had difficulty covering their operating and administrative costs in the past. This increase in funding is welcome and it appears to be having some effect on local revenues, as discussed above. It could be made even stronger if it were accompanied by greater spending autonomy by local governments. As it now stands, local authorities are limited in how the development funds are spent, and they have no ability to increase the property or real estate tax rate to grow the fund. The second investment fund is an equalisation mechanism, the Solidarity Fund – Fondo de Solidaridad – which can be used to finance service and “soft-infrastructure” projects and programmes. It is a common pool fund with a redistribution formula, part of which is based on population. There is general agreement that this fund needs to be reformed. The Public Works and Municipal Services programme (Programa de Obras Públicas y de Servicios Municipales) transfers USD 110 000 to each junta comunal (the representative body of each corregimiento), of which 70% can be used for investment projects (subject to citizen consultation) and the remaining sum can be dedicated to administrative or operational functions (República de Panamá, 2015). Certainly the introduction of these funds is a large shift from the past when priorities and spending were centrally managed. However, the funds are in essence central level transfers and not a delegation of fiscal responsibilities. Thus, fiscal decentralisation through the law is limited.

Second, administrative decentralisation requires further clarification in the criteria of selection, funding and transfer of responsibilities. Service and administrative responsibilities will be delegated to accredited municipalities that have proven capacity to manage their investment funds based on their investments and results achieved. Accreditation requires a completed PED, and each municipality must apply to receive delegated responsibilities. It is expected that in 2018 the Secretariat for Decentralisation will begin the process of determining municipal capacity, classifying municipalities according to ability, and then identifying which responsibilities will be transferred. It is a form of asymmetric decentralisation which can be successful for ensuring improved service delivery by municipalities. However, there is a need to clarify: a) the criteria that will be used to determine capacity and/or eligibility for the responsibilities; b) how municipal classifications will be matched to responsibilities – will responsibilities be grouped into sets, or will it be a pick–and-choose approach; c) how the new responsibilities will be funded, if through a central level transfer or through greater revenue-generating capacity at the local level; and d) how to ensure a balanced transfer of responsibilities across the territory and across sectors. There is a risk of generating incoherence in the degree of decentralisation and even greater subnational inequality, particularly if smaller municipalities do not have the capacity to take on additional responsibilities.

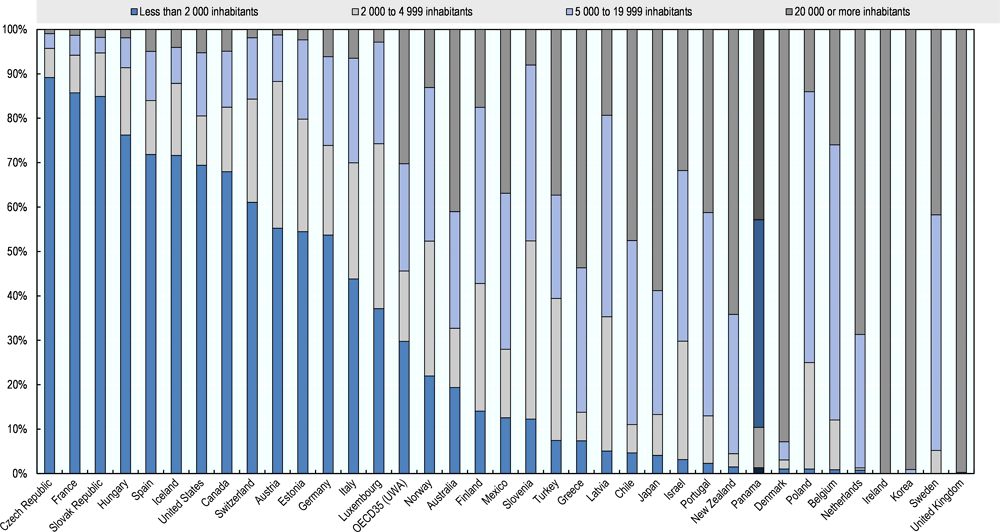

Third, the success of decentralisation may depend on addressing municipal capacity. There is a resource gap at the local level. In some countries this is due to scale and excessive fragmentation (too many small municipalities). In other cases it is due to limited municipal revenues. In Panama, only a very small percentage of municipalities have less than 5 000 inhabitants (Figure 3.9), and so the problem is more likely to be due either to the cost of service delivery or to low revenue-generating capacity rather than fragmentation. Given the limited service responsibilities attributed to municipalities, the former is not likely to be a significant factor. The latter, low revenue-generating capacity, however, is highly probable. Diverse factors can contribute to the resources shortfall, including the high levels of labour force informality, which then impacts tax revenue (see Chapter 4). However, for such a reform to be successful subnational authorities must have the administrative capacity and revenue-generating base to meet the responsibilities which they are assigned. While the current decentralisation law provides them with additional funds in the form of transfers, it does not necessarily solve the problem in the long run because it is not increasing their capacity to meet cost obligations, by either reducing expenditures or increasing revenues.

It is still too early to determine if the decentralisation law will lead to a more decentralised approach and, through this, will better support regional development at the local level. Its success will rest on, among other things, the capacity of municipalities to manage their revenues in light of new expenditure responsibilities (e.g. generate more revenue or reduce costs), the responsibilities that are transferred down, and the degree of autonomy local authorities have with respect to municipal management, prioritising investment, delivering services and using their resources. Panama may wish to consider the guidelines for effective decentralisation that the OECD has developed as these can help governments identify where and how they can strengthen their approach to decentralisation (e.g. through a clear, coherent and balanced decentralisation process, sufficient subnational capacity, adequate co‑ordination mechanism and room for pilots or experimentation) (Annex C).

Figure 3.10. Municipal population levels by number of inhabitants

Note: Data for Panama comes from 2010 census.

Source: Controlaría General de la República de Panamá (2010), https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=10&ID_PUBLICACION=556&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=3; OECD (2017c), “Subnational governments in OECD countries: Key data” (brochure), www.oecd.org/regional/regional-policy (database: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en).

Taking a “new paradigm” approach to regional development

There are several forces affecting Panama’s capacity for more inclusive territorial development. The first is strong socio-spatial segregation at the regional level that separates non-indigenous and indigenous, as well as urban and rural communities. This is mirrored by socio-economic segregation at the local level, particularly within large urban and metropolitan areas. Socio-spatial segregation, particularly of residences, by ethnicity, class or race, combined with an uneven spatial distribution of quality public services, results in limited opportunity for a percentage of the population (Greenstein et al., 2000). While this is particularly true in cities, it is certainly applicable to regions as well. Addressing this, requires strongly integrated activity across ministries and levels of government to build programmes and design service delivery that can begin to break down the barriers (horizontal co‑ordination), and a clear policy path outlined in a national level document dedicated to regional development and supported by subnational (provincial and comarca) plans (vertical co‑ordination).

The second is a policy of wealth redistribution based mainly on social transfers. Although they are well targeted, territorial differences in Panama’s wellbeing outcomes remain high (OECD, 2017a). Some consideration should be given to how to increase the sustainability of regions and communities so that such transfers are less necessary. There is a strong need for subnational governments to be able to generate wealth, and ideally manage at least some of it. This is closely linked to making sure the provinces, comarcas, cities and other categories of local communities are attractive places to live and offer opportunities for employment, which itself is linked to subnational development. The risk with Panama’s approach, particularly over the long term, is that it does not help lagging regions adjust their productive capacities.

The third is insufficient subnational capacity to partner with the national government in addressing social cohesion from a territorial perspective. Panama’s approach to territorial development has been “top-down”, expressed through successive government programmes, and driven by social and other transfers. This has left little room for subnational – and especially local – governments to build experience in dealing with complex policy matters in a “bottom-up” fashion. Provincial governments do so as extensions of the national government and its line ministries, comarca governments are semi-autonomous and thus not expected to undertake the same initiatives as provinces, and municipalities have limited resources, despite being where the impact of inequalities is most strongly felt. The result is a capacity gap at all levels of government in the area of regional development. This being the case, and given the principle of subsidiarity, subnational governments should have the capacity in terms of resources (financial, human capital and infrastructure) to play a stronger role in development of their territories.

Panama’s approach to regional development has focused on addressing economic disparities through subsidies and state aid transferred by the central government to provinces and comarcas, as well as redistributive policies and the funding of sector-driven projects. Given the socio-economic challenges, Panama may wish to consider shifting away from its traditional approach toward the “new paradigm” highlighted at the beginning of this chapter. From a strategic perspective, a “new paradigm” approach could help subnational authorities (e.g. provinces, comarcas, metropolitan areas) maximise their capacity to improve wellbeing outcomes. It can offer a more sustainable approach, and has the advantage of allowing greater flexibility in addressing and harnessing the unique opportunities offered by Panama’s different provinces and comarcas. It would mean, however, developing an explicit regional development policy at the national level, taking an integrated approach to policy and programming, developing effective performance measurement systems to generate accountability by government to citizens, and building stronger partnerships with subnational governments and other stakeholders to collectively identify unique competitiveness factors and capitalise on local assets.

A national regional development policy to improve co‑ordination across different levels of governments

An explicit national-level policy for sustainable regional development and growth would be beneficial in Panama as it could clearly articulate national territorial objectives and priorities, and build vertical co‑ordination and co‑operation mechanisms between relevant stakeholders across different levels of government. It could also engender greater coherence in the implementation of sector strategies and support policy and programming prioritisation at the subnational level. A policy of this kind can guide actors with diverse interests on how to proceed, while reinforcing and clarifying accountability of input and of results. Its success, however, depends on clear strategic direction on the part of the central government, as well as strong bottom-up involvement in order to build ownership between central and subnational authorities, the private sector, civil society organisations, and citizens (Cuadrado-Roura and Güell, 2008).

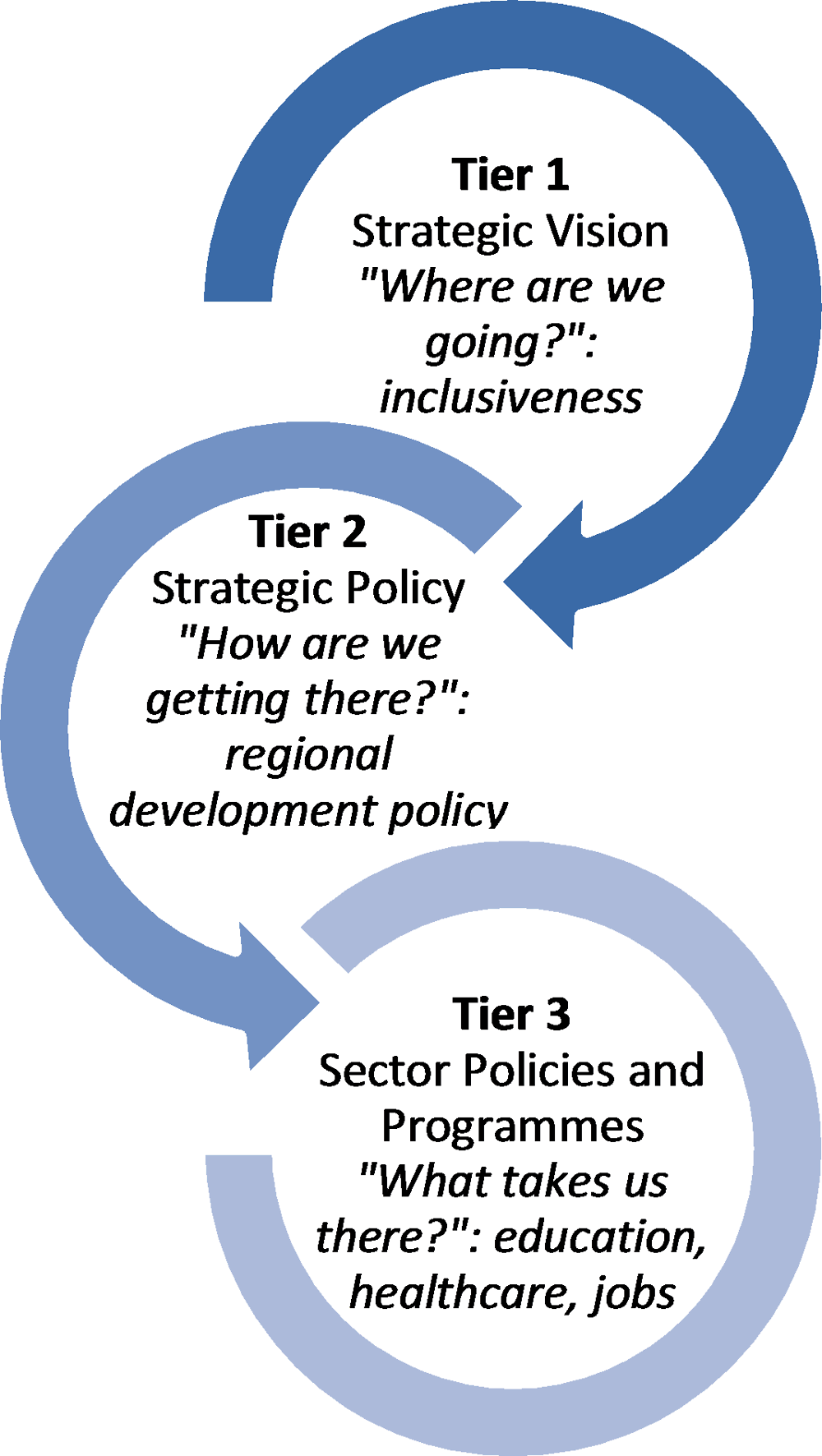

A general strategic framework for regional development is based on a clear hierarchy, in which each tier cascades down from the one above (Figure 3.10). The first tier sets the vision and should transcend political parties and election cycles, reflecting societal aspirations for the country. Tier 2 provides the roadmap for realising the larger ambitions, and finally the Tier 3 offers the practical dimension of implementation. In Panama, and specifically with respect to regional development, Tier 1 could correspond to a vision for a more inclusive society, supported by a national regional development policy with clearly articulated objectives (Tier 2), including, for example, poverty reduction among indigenous communities and rural areas, and realised through Tier 3 sector and subnational policies, programmes and projects that contribute to reducing poverty (e.g. healthcare, education, economy, labour, housing, public works).

Figure 3.11. The policy cascade: a schematic using a vision based on inclusiveness

Source: Adapted from OECD (2016f), OECD Territorial Reviews: Córdoba, Argentina, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262201-en.

A formalised national regional development policy would be valuable for supporting development goals, and for guiding relevant policy development and implementation among line ministries in the short and medium terms. One of the obstacles in Panama’s policy process, however, is a lack of technical capacity. Strengthening technical capabilities within ministries is on the government’s agenda and could improve planning and evaluation. To do so, however, additional in-work training is important, as well as building the professionalisation of Panama’s civil service through a more stringent and transparent admission process (OECD, 2017a).

Approaches to formalising regional development in selected countries

The formalisation of regional development strategies varies across countries. Some countries develop explicit long- or medium-term strategic documents (e.g. Ireland and Sweden), while others, such as Mexico, create a specific plan linked to the government programme, and still others use intergovernmental contracts (e.g. France and Colombia) (Box 3.4). Regardless of the approach, the majority of OECD countries, including the Czech Republic, Estonia, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Norway and Switzerland, follow an explicit regional development strategy defined in one or several documents. Those that do not have an overarching strategic policy include federal countries (e.g. Belgium, Germany and the United States). On average, countries have two strategic documents – in some cases a legal framework complemented by a more regularly updated plan (e.g. seven years is common in European Union (EU) countries to correspond with the EU policy cycle). This permits them to strike a balance between policy stability over time and flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances (OECD, 2016a). In all cases, however, formalised strategies and/or policies help co‑ordinate the diverse interests involved in regional development. In addition, they can provide some guidance for dedicated urban and rural development policies.

Box 3.4. Formalising regional development strategies: examples from select countries

Long- and medium-term regional development strategies: Ireland and Sweden

The National Spatial Strategy for Ireland 2002-2020 was developed to guide more balanced regional development. It aims to improve the spread of job opportunities throughout the country, improve the quality of life, and improve the places where people live. It examines the country’s economic and spatial structure, identifies how the various regions can contribute to realising the strategy’s objectives, and takes an integrated approach by indicating the role that policies promoting economic development (e.g. employment, tourism), housing, quality of life (e.g. social infrastructure, service delivery, urbanism), and the environment play in building and ensuring competitive regions. It also includes guidelines on implementation, clearly designating a ministry responsible for co‑ordinating the plan’s implementation, setting an implementation time frame, and building ownership among subnational governments through the preparation and adoption of statutory regional planning guidelines.

Sweden’s National Strategy for Sustainable Regional Growth and Attractiveness 2015-2020 serves as a guideline for regional authorities, state agencies, government offices, non-governmental organisations and other actors involved in regional growth efforts. The strategy aims to help actors prioritise regional-level activities, such as sectoral programming at the national level and regional-level development strategies. It is also used to support spending evaluations, specifically of national grants, and it monitors and steers the use of central government appropriations for regional growth measures. The strategy elaborates priorities for regional growth and how meeting these can help address societal challenges, and identifies policy tools for the strategy’s implementation. The document also highlights the role of regions in meeting the strategy’s objectives and the importance of subnational regional development strategies.

A dedicated regional development policy linked to the government programme: Mexico

Within the framework of its 2013-2018 National Development Plan, Mexico developed a Regional Development National Policy. It focuses on regional, urban and rural development, and includes infrastructure, competitiveness, social inclusion and environmental sustainability. The Ministry of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development complements the national policy with regional programmes for development covering to the north, south-southeast and central regions of the country, which are countersigned by 15 ministries.

A contractual approach to regional development: France and Colombia

France promotes its regional development and investment priorities through a series of planning contracts – Contrats de Plan Etat-Région – signed between the state and its regions on six- to seven-year cycles. In these planning contracts, the state and subnational authorities of all levels identify priorities and develop a common strategy to promote territorial competitiveness and attractiveness. In the current cycle, the six priority areas for investment are multimodal mobility; higher education, research and innovation; the environment and energy transition; digital technologies and very high-speed broadband; innovation, industries and factories of the future; and regions, with employment being the transversal priority linking the rest. In order to ensure equality between territories within regions, contracts mobilise specific resources for priority areas (i.e. urban priority neighbourhoods, vulnerable areas undergoing major economic restructuring, rural areas and others facing a deficit of public services, metropolitan areas and the Seine Valley).

Colombia has developed the contratos plan between the national government and departments to facilitate their interaction and to help deliver regional development policy. The contrato plan is a multiyear binding agreement between them and co-ordinates their investment agendas. Contracts focus on improving road connectivity, poverty reduction and support for regional competitiveness. The contrato allows departments and municipalities to co‑ordinate different sources of revenues from different levels of government.

Sources: Republic of Ireland, National Spatial Strategy for Ireland 2002-2020: People, Places and Potential, Government of Ireland, Stationary Office, Dublin, Ireland, available at: http://nss.ie/pdfs/Completea.pdf; Sweden, Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation (n.d.), National Strategy for Sustainable Regional Growth and Attractiveness, 2015-2020 – Short Version, Government offices of Sweden, Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation, Stockholm, Sweden, available at: http://www.government.se/information-material/2016/04/swedens-national-strategy-for-sustainable-regional-growth-and-attractiveness-20152020---short-version/; OECD (2016a), OECD Regional Outlook, 2016: Productive Regions for Inclusive Societies, Country Notes, OECD Publishing, Paris, available at: http://www.oecd.org/regional/oecd-regional-outlook-2016-9789264260245-en.htm; France, Ministère de la Cohésion des Territoires (2015), Les Contrats de Plan Etat-Région: Présentation Générale, Ministère de la Cohésion des Territoires, Paris, France, available (in French) at: http://www.cohesion-territoires.gouv.fr/les-contrats-de-plan-etat-region; OECD (2016d), Making the Most of Public Investment in Colombia: Working Effectively across Levels of Government, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265288-en.

An overall regional development policy with a framework to support comarca development

Incorporating the comarcas as a strategic component to national development would be an important step toward addressing the challenges posed by socio-spatial segregation. However, as part of the policy’s implementation, Panama may also wish to include a framework dedicated to the development of the comarcas to better work with and support the unique opportunities and complex challenges facing indigenous communities. Canada has taken this approach with its Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development (Box 3.5). In addition, Canada’s Department for Indigenous and Northern Affairs7 explicitly links its sustainable development objectives with the federal sustainable development strategy through its departmental plan. This plan also articulates a series of performance indicators that either contribute to a goal or target or are specific programme activities that support sustainability outcomes, for example clean drinking water, effective action on climate change, sustainable food, and safe and healthy communities (Government of Canada, 2017).

Box 3.5. Canada’s Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development

Introduced in 2009, the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development is a roadmap for the government’s actions and activities (i.e. legislation, partnerships and programmes) dedicated to increasing the participation of Canada’s First Nations, Inuit and Métis people in the Canadian economy, and to improve economic action for indigenous peoples throughout the country. The Framework emphasises strategic partnerships with indigenous groups, the private sector, provinces and territories. The Framework seeks to maximise federal-level investment by: i) strengthening entrepreneurship; ii) enhancing the value of indigenous assets; iii) building new and effective partnerships to maximise economic development opportunities; iv) developing indigenous human capital; v) more effectively focusing on the role of the federal government. Its aim is to build indigenous communities that are able to seize economic development opportunities, to achieve viable indigenous businesses and that have a skilled indigenous workforce.

Through a process of extensive engagement with indigenous communities the Framework has been adjusted since its introduction to reduce administrative burdens and programme duplication. The result is a streamlined set of five programmes dedicated to increasing the participation of indigenous communities in Canada’s economy and to help indigenous peoples pursue new opportunities for employment, income and wealth creation. To support this effort the government has integrated land management with economic development to facilitate support to communities as they build their economic base.

Sources: Government of Canada (2015), “Lands and Economic Development”, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Ottawa, Canada, available at: www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca; Government of Canada (2010), “Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development”, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Ottawa, Canada, available at: www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca.

In 2013-14, Panama embarked on a similar path with an integrated development plan for indigenous communities (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Integral de Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá), articulated in conjunction with the UNDP. The plan was based on a dialogue process between Panama’s indigenous communities, the government, the United Nations and the Catholic Church. The process called for establishing a National Council for the Development of Indigenous Communities in Panama (Consejo Nacional de Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá), which would oversee the Plan’s implementation and be responsible for designing and implementing future economic, social and cultural development strategies for indigenous communities (UNDP, 2014). A draft law establishing the Council and its responsibilities, including the integrated development plan, was presented to the National Assembly but failed to garner sufficient votes to be approved. As of 2018, the government is revisiting this Plan and has established a timeline for launching its implementation. In addition, a USD 80 million loan from the World Bank was announced in March 2018, specifically for this initiative (World Bank, 2018). As a complement to this plan and in direct support of its objectives, Panama may wish to consider this idea of a territorial development strategy for comarcas as part of a larger regional development policy, which could also help embed the action across electoral cycles. This should be accomplished with the active involvement of the comarcas and supported in its realisation through comarca development plans elaborated at the community level.

Introducing regional development planning at the provincial and comarca level

There is a need to reconcile national and subnational level development priorities. While at the national level priorities may be highly “macro” (e.g. inclusiveness), at the subnational level they are imminently practical (e.g. sanitation, schools and healthcare). These two perspectives are not mutually exclusive but rather mutually supportive. To capture the potential synergies, a link needs to be made between government aims and subnational priorities. Without such links regional development risks remaining a series of sector and ad hoc programmes and projects at the national and local levels that may not be complementary and therefore have difficulty effectively contributing to meeting development objectives in a coherent and integrated fashion.

Intermediate level plans could help bridge Panama’s goals and the immediate and highly practical development needs of subnational governments. Subnational regional development planning – including at the metropolitan level – can lead to greater responsibility being taken by the provinces and comarcas, particularly when the plans are designed, implemented and monitored at the subnational level and in dialogue with the central government. It would, however, require that each intermediate authority play an active role in identifying its development objectives and the mechanisms to realise them.

The capacity and capability challenges in planning seen at the central level are even more acute at the subnational level. Thus a focused effort on training and support for planning among subnational leaders would have to be made. Building the capacity among subnational officials to develop such plans, however, will be critical. This was the approach taken with the majority (73 of 77) of local authorities when developing their PED, for example. In these cases, the Direction for Investment Programming, through the Department for Regional Planning in the Ministry of Economy and Finance, developed a methodological guide and worked with local planners and in consultation with civil society and other stakeholders, to develop the PED. A similar approach could be taken if deciding to introduce regional-level development plans. In addition, consideration should be given to first developing a national-level policy which can subsequently be used to guide the design of subnational plans. This requires a region’s perspective of its priorities, strengths and weaknesses, and combines both top-down and bottom-up elements in development planning.

In addition, consideration should be given to building financial capacity as well. Regional development policies, plans and programmes are stronger when associated with funding. For instance, a regional development fund could be established as a fixed line item in the national budget and then distributed on a formula-based allocation system. Another option would be to combine a formula-based budget with a national development fund. This would provide each province with its own budget, affording greater budget visibility and decision-making flexibility, and would shift away from the current system of earmarked grants transferred by individual line ministries to a block operating, service and investment grant. Uruguay has adopted this method for financing its provincial tier and promoting regional and local development (Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Subnational financing mechanisms for development in Uruguay

Uruguay’s constitution establishes that 3.33% of total annual government income be transferred to its departmental (provincial) governments. The system is constructed so that subnational governments share in the economic success of the country and in case of economic difficulties the risk of budget shortfalls is somewhat mitigated as provincial governments know they will be guaranteed a certain amount of funding. If a provincial government does not meet its performance agreement as established with the national government, it does not receive its full portion of the 3.33% set aside. Thus, not only is there a monitoring mechanism built into the system, but also an incentive for responsible fiscal management and performance.