This chapter proposes a series of indicators to assess the achievement of regional goals, as discussed in the previous chapters. The scorecard tracks the past performance of these indicators and sets targets for 2037. Where data are not available, it suggests information that national and local governments could collect to make the scorecard effective. The scorecard also maps each regional objective in the Action Plan against the Sustainable Development Goals and targets, ensuring coherence between policies adopted by the North with international standards of development.

Multi-dimensional Review of Thailand

Chapter 4. A scorecard to track sustainable development in the North

Abstract

The scorecard proposes indicators for measuring implementation and performance of the action plan until 2037

Scorecards with measurable indicators are used to monitor the implementation of policies and the achievement of desired results. The scorecard presented here proposes indicators to accompany the action plans presented in previous chapters. It can be employed for monitoring, decision making and ensuring accountability towards citizens, and should be regularly updated and made publicly accessible.

Each indicator is designed to provide a snapshot of the status quo and to establish a target for 2037. The scorecard presents the following values for all indicators:

The level attained by Thailand at the launch of the National Strategy 2037 and the 12th National Economic and Social Development Plan (NESDP) (2017 or latest available year).

The level reached during the five years prior to the launch of the NESDP.

The objectives to be attained by 2037 in line with the long-term National Strategy.

To help with the preparation of a multi-dimensional reporting system, the scorecard also maps each item in the Action Plan to the relevant Sustainable Development Goal.

Northern provinces develop capabilities to exploit their full potential

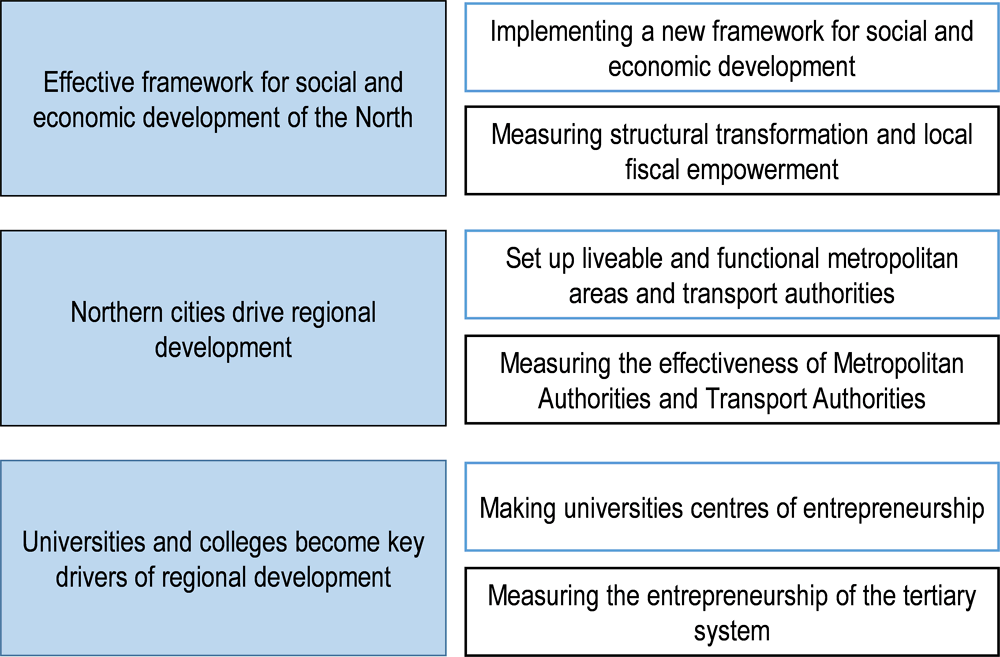

This section presents a series of indicators to track policies aiming to unlock the potential of Northern provinces. The scorecard divides indicators into two categories: those monitoring implementation of these actions, and those measuring their outcomes. Figure 4.1 summarises this distinction for each of the three goals of regional development.

Figure 4.1. The scorecard distinguish between indicators measuring implementation and those measuring outcomes

Note: The objectives for indicators measuring implementation are presented in rectangles with blue borders. The objectives for indicators measuring outcomes are presented in rectangles with black borders.

Where data are available, regional objectives for 2037 are computed with respect to the past performance of regional champions. Otherwise, the scorecard presents data that national and local governments were able to collect with a view to better guiding policy implementation in line the recommendations of the MDCR.

An effective strategy and strong LAOs drive the development of the North of Thailand

The scorecard proposes a series of indicators to implement a new framework for social and economic development in the North (Table 4.1). The Action Plan presents a bottom-up and data-driven approach designed to uncover the local potential for innovation. At the centre of this new regional policy framework is an institutionalised public-private strategy group called Smart Lab. Chapter 2 presents Smart Labs as small and dynamic working groups that gather local authorities, entrepreneurs from rising and innovative sectors and academic experts. Depending on the number of sectors and economic activities emerging as comparatively advantageous from the data analysis, each province may have several Smart Labs. Provincial, regional and central authorities need to consolidate the development strategies produced by each Smart Lab.

The creation and activity of Smart Labs can be monitored by the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC), relevant ministries and local administrations. A basic indicator in this regard is the number of Labs created in each province of the North. Local stakeholders are responsible for the organisation of these Labs; however, national and regional authorities should track the discovery process, map the initiatives throughout the country, and ensure the coherence of existing national and regional strategies.

Data analysis could support the discovery process of the Smart Labs. As a first step, the NESDC, local authorities and universities could sift through production surveys and censuses to identify products that contribute significantly to provincial net value added, relative to the rest of the country. Such products would have a revealed comparative advantage (RCA) significantly high and represent the current strengths in the region.1

The number of manufacturing sectors with a revealed comparative advantage is increasing. The analysis of the industrial census suggests that Northern provinces have significantly high comparative advantage in 73 sectors, on average (Table 4.1). This figure increased from 2012. Phichit “created” the highest number of sub-sectors between 2012 and 2017 (around 3 per year). With a similar performance, the North could almost double the number of sectors contributing significantly to the provincial value added. Note that these figures refer only to the manufacturing sector, obtained through the Industrial Census. More detailed information about the value added generated by other sub-sectors (for example, in agriculture and tourism) would allow for a more complete assessment of the strengths of the Northern provinces.

Table 4.1. An effective strategy and strong LAOs drive the development of the North of Thailand

|

SDG |

Recommendation |

Indicator |

2012 |

2017 |

2037 |

Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected result 1: Create a strategy for developing the Northern Region, building on local discovery |

||||||

|

|

Smart Labs for entrepreneurial discovery of business and innovation potential (3) |

Number of Smart Labs created in the province |

||||

|

|

Support strategy process with analysis of product and innovation data, as well as crowdsourcing (2) |

Average number of subsectors that contribute significantly to provincial value added |

67 |

73 |

129 |

Convergence towards best performer (Phichit) |

Note: The average number of subsectors that contribute significantly to provincial value added is measured using the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) indicator. The RCA is based on net value added of productive manufacturing activities derived from the Industrial Census 2012 and 2017. Activities are classified according to the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) at the two-digit group level.

The purpose of the Smart Labs and the data-driven discovery process is to expand the productive capabilities of the North. Table 4.2 presents a series of indicators to measure the productivity of main economic sectors in the region as well as the diversification of its economy. The analysis and RCA and the product space methodology would give a sense of the degree of specialisation of the Northern economy. In the absence of relevant data, the Herfindahl-Hirschmann index could work as a good measure of the average diversification of the local economy (see Chapter 2 for more details).2

The North could improve sectoral productivity by following in the footsteps of regional best performers. For example, the productivity of the agricultural sector in the best performing province – Nakhon Sawan – grew by 4.9% every year between 2012 and 2016. If this rate is maintained, average regional productivity could triple by 2037. Similarly, manufacturing productivity in the most productive manufacturing province – Kam Phaeng Phet – has increased by 7% every year between 2012 and 2016. If the North converged to this rate, regional manufacturing could become four times more productive. The average Northern province could increase its tourism revenue per number of visitors by benchmarking policies to the experience of the regional champion in the field – Chiang Mai.

Northern provincial economies should keep on diversifying. Between 2012 and 2016, the Herfindahl-Hirschmann index has been decreasing because economic activity is spread more equally across sectors. If the Northern provinces were diversifying at the same speed as the regional best performer, the index would decrease further by 0.01 points every year until 2037. As the North moves up the development curve, provinces will specialise in fewer sectors, depending on their openness to trade and integration within the national and global value chain (Jean Imbs and Wacziarg, 2003[1]).

Table 4.2. An effective strategy and strong LAOs drive the development of the North of Thailand

|

SDG |

Recommendation |

Indicator |

2012 |

2017 |

2037 |

Methodology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected result 1: Create a strategy for developing the Northern Region, building on local discovery |

|||||||

|

|

Support strategy process with analysis of product and innovation data, as well as crowdsourcing (2) |

Agriculture value added per worker (constant BHT) |

34 512 |

34 785* |

99 216 |

Convergence towards best performer (Nakhon Sawan) |

|

|

|

Support strategy process with analysis of product and innovation data, as well as crowdsourcing (2) |

Manufacturing value added per worker (constant BHT) |

162 188 |

201 437* |

907 981 |

Convergence towards best performer (Kam Phaeng Phet ) |

|

|

Tourist revenue per number of visitors |

3 147 |

9 534 |

Convergence towards best performer (Chiang Mai, 2017) |

||||

|

Herfindahl-Hirschmann index of economic concentration |

0.33 |

0.27* |

0.13 |

Convergence towards best performer (Chiang Mai) |

|||

|

Expected result 2: Strengthen LAOs in the Northern Region – experiment with innovation in tax collection and transfers |

|||||||

|

|

Test innovative methods for property tax collection to increase LAO revenues (4) |

LAOs’ direct tax revenue (% GPP) |

0.4 |

0.5* |

3.5 |

Convergence towards best performer (Uttaradit) |

|

|

LAOs’ direct tax revenue (% LAOs’ total revenues) |

4.8 |

5.4 |

9.2 |

Convergence towards best performer (Chiang Mai) |

|||

|

|

Experiment with a simplified but more effective system of transfers (6) |

LAOs’ revenue from grants (% LAOs’ total revenues) |

52.4 |

48.0 |

26.0 |

Convergence towards best performer (Chiang Mai) |

|

|

LAOs’ revenue from general grants (% LAOs’ total revenue from grants) |

42.2 |

91.2 |

Constant |

||||

|

Gini coefficient of subnational government revenues, grants |

0.2 |

0.2 |

Constant or decreasing |

||||

Note: * 2016 is the latest year available for GPP.

Source: The values available are the authors’ calculation based on data provided by the Department of Local Administration, Ministry of Interior.

The scorecard proposes indicators to track the fiscal empowerment of LAOs. This is crucial to develop local productive capacities. Local authorities need to strengthen their fiscal position and autonomy in order to better exploit local potential and tackle obstacles to local growth. The proposed indicators measure the share of local revenues collected by provinces and the income from transfers. LAOs should be able to increase more taxes as a share of total revenue and depend less on total grants. Moreover, Thailand should prefer general grants to conditional ones and thus invert the current trend.

Northern cities drive regional development

Cities can become drivers of regional development once they are properly defined. Urban areas in Thailand are currently defined along administrative borders and therefore underestimate the actual number of “urban users”: most of them commute every day from neighbouring administrations. The North could pioneer such a redefinition to better tailor and co-ordinate the provision of integrated urban services.

To redefine its cities, the North could apply the OECD Functional Urban Area (FUA) methodology. A preliminary analysis shows that there are four main metropolitan areas with more than 100 000 inhabitants in the North: Chiang Mai, Phitsanulok, Chiang Rai and Mae Sot (Table 2.3, Chapter 2). To refine this result and define FUAs, relevant authorities should survey the commuting time of households living in the existing urban centres – as defined by NSO – and within a distance of 300 km.

Once FUAs are defined, they should be equipped with Metropolitan Authorities and Transport Authorities (Table 4.3). Each Metropolitan Authority is a government layer, established through legislative decree and similar to the existing metropolitan area of Bangkok and Pattaya. The Metropolitan Authority co-ordinates the provision of public services and investments in infrastructure throughout the whole FUA. Those living within the Authority’s boundaries elect a mayor, who is then directly accountable for the execution of the development plan for the FUA. A Transport Authority could work independently from the Metropolitan Authority to co-ordinate the transport system of all existing administrative units encompassed by the FUA.

Table 4.3. Set up liveable and functional metropolitan areas and transport authorities

|

SDG |

Recommendation |

Indicator |

2013 |

2017 |

2037 |

Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected result 3: Re-organize urban policies for performance and accountability |

||||||

|

|

Establish a metropolitan authority for Chiang Mai, then also for other Northern cities (8) |

Define Metropolitan Authorities by legislative decree |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

|

Expected result 4: Inclusive and sustainable urban infrastructure |

||||||

|

|

Create a transport authority for Chiang Mai, then also for other Northern cities (10) |

Establish Metropolitan Transport Authorities by legislative decree |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Note: The four FUAs should encompass the following urban agglomerations which have more than 100 000 inhabitants, as identified through the analysis of the Global Human Settlement Layer: Chiang Mai, Phitsanulok, Chiang Rai and Mae Sot (Table 2.3, Chapter 2).

The scorecard proposes a series of indicators to track the impact of Metropolitan Authorities and Transport Authorities on well-being (Table 4.4). Indicators should monitor accessibility to infrastructure, as well as infrastructure quality, in the four Northern FUAs. To ensure accurate policy targets the indicators require frequent updates. The necessary data collection could be carried out on a yearly basis through a combination of door-to-door and online surveys. In addition, satellite imagery and remote-sensing data could provide real-time information relevant for certain indicators, such as commuting patterns.

Table 4.4. Measuring the effectiveness of Metropolitan Authorities and Transport Authorities

|

SDG |

Recommendation |

Indicator |

2012 |

2017 |

2037 |

Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected result 4: Inclusive and sustainable urban infrastructure |

||||||

|

|

Build a data system to monitor the quality of urban infrastructure (11) |

Average commuting time within a metropolitan area (minutes) |

49.3* |

|||

|

Average travel distance (km) |

17.8* |

|||||

|

|

Build a data system to monitor the quality of urban infrastructure (11) |

Municipal water withdrawal (% of total water withdrawal) |

||||

|

Treated municipal wastewater per year (109 m3/year) |

||||||

Note: * Average commuting time and distance refers to the Chiang Mai urban area only, as identified by (Jittrapirom and Emberger, 2013[2]).

Universities and colleges become key drivers of regional development

The tertiary education system in Thailand could work to develop entrepreneurship among its students and in local communities (Table 4.5). To achieve this objective, universities and local colleges need to adapt their coursework to the needs of the local labour market and incorporate entrepreneurship values. Identifying such courses requires a census of the current offer of tertiary institutes (Byun et al., 2018[3]).3 Universities and entrepreneurs can also form partnerships to develop specific research questions for business development. Chapter 2 presented the Christian Doppler Research Association in Austria as a possible example for Northern provinces to follow.

Table 4.5. Making universities centres of entrepreneurship

|

SG |

Recommendation |

Indicator |

2013 |

2017 |

2037 |

Methodology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected result 5: Universities promote entrepreneurship education |

|||||||

|

|

Integrate technical education with entrepreneurship education (12) |

Average number of entrepreneurship courses, by university |

|||||

|

Expected result 6: Universities support entrepreneurship |

|||||||

|

|

Create networks of universities and private sector to support SMEs and start-ups (14) |

Average number of university-enterprise labs, by province |

|||||

Selected indicators could then measure the impact of entrepreneurship graduate programmes and support (Table 4.6). One possible indicator is the share of youth and adults with advanced ICT skills. The Ministry of Education could, moreover, survey adults of working age to measure their skills and to establish how they are used at home, at work and in the wider community. The OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) provides excellent guidelines in this regard. The Ministry of Education could also organise a census of courses offered by tertiary institutes and assess their “level of entrepreneurship”. Central and local authorities, as well as potential international donors, could assess the performance of university-enterprise labs by measuring the number of patents or peer-reviewed articles published by affiliated researchers.

Table 4.6. Measuring the entrepreneurship of the tertiary system

|

SDG |

Recommendation |

Indicator |

2013 |

2017 |

2037 |

Methodology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected result 5: Universities promote entrepreneurship education |

|||||||

|

|

Integrate technical education with entrepreneurship education (12) |

Youth and adults with information and communications technology (ICT) skills (% age-relevant population) |

|||||

|

|

Integrate technical education with entrepreneurship education (12) |

Students attending entrepreneurship courses (% tertiary students) |

|||||

|

Expected result 6: Universities support entrepreneurship |

|||||||

|

|

Create networks of universities and private sector to support SMEs and start-ups (14) |

Average number of patents registered by researches and companies affiliated with the labs |

|||||

|

Average number of peer-reviewed publications published by researchers affiliated with the lab |

|||||||

Northern provinces adopt a risk management approach to water security

The scorecard proposes a series of indicators to monitor the adoption of a risk management approach to water and disaster management in the North. The first group of indicators are adapted from the OECD Water Governance Indicators. The NESDC and the OECD independently assessed the performance of Thailand with respect to the OECD Water Governance indicators. The OECD based the assessment on the material and information collected during the workshops and the meetings with local authorities in Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai, held in November 2018 (Table 4.7). It is preferable to assess current performance against these indicators and set future targets as part of a multi-stakeholder participatory process. Thailand could revisit these indicators possibly via the NWRC and collate the views from each line ministry and stakeholder involved in water management. This could be implemented via a facilitated workshop. In the long term, the North should aim to reduce the impact of floods and droughts and improve the wastewater sector to curb pollution.

As part of the multi-stakeholder review of performance, Thailand should also consider collecting the data and tracking indicators concerned with the implementation of water-related SDGs and the water security indicators developed by the Asian Development Bank as part of its Asian Water Development Outlook (AWDO) exercise. The AWDO indicators are a composite indicator of five water-related dimensions – household, economic, urban, environment and resilience (ADB, 2016[4]).

Table 4.7. The transition towards a risk management approach to water security requires empowered and evidence-based regional decision-making as well as good infrastructure

|

SDG |

Recommendation |

Indicator |

2013 |

2018 |

2037 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected result 1: Regional actors are empowered to deliver water management responsibilities |

||||||

|

|

The national strategy is structured to empower the development of localised and prioritised regional strategies (1) |

Effective implementation of cross-sectoral policies and strategies promoting policy coherence between water and key related areas, in particular environment, health, energy, agriculture, land use and spatial planning. |

4 (2) |

5 |

||

|

|

Clarity over roles, responsibilities and reporting requirements should be ensured (2) The role and responsibilities of River Basin Management Organisations must be clear and add value (4) |

Existence and implementation of mechanisms to review roles and responsibilities, to diagnose gaps and adjust when need be. |

4 (4) |

5 |

||

|

|

Position the National Water Resources Committee (NWRC) as the multi-stakeholder platform for decision making on water management issues (3) |

Existence and functioning of an inter-ministerial body or institutions for horizontal co-ordination across water-related policies. |

4 (3) |

5 |

||

|

Expected result 2: Robust, evidence based decision making prioritises regional action |

||||||

|

|

Data must be centralised and include information on floods, droughts, water supply and demand and water quality (5) |

Existence and functioning of public institutions, organisations and agencies in charge of producing, co-ordinating and disclosing standardised, harmonised and official water-related statistics. |

Standardisation: 5 Harmonisation: 1 (1) |

5 |

||

|

|

Data must be centralised and include information on floods, droughts, water supply and demand and water quality (5) Information must be used to inform decision making, prioritise compliance and enforcement activities, water allocation and infrastructure priorities (8) |

Existence and level of implementation of mechanisms to identify and review data gaps, overlaps and unnecessary overload. |

3 (3) |

5 |

||

|

|

A revised list of policy tools should be deployed to achieve national and regional objectives (7) |

Existence and level of implementation of mechanisms to review barriers to policy coherence and/or areas where water and related practices, policies or regulations are misaligned. |

4 (2) |

5 |

||

|

Expected result 3: Appropriate infrastructure solutions are selected with adequate capital and O&M budgets allocated |

||||||

|

|

A robust financial plan should be developed and aligned with delivery of the strategic plan (9) |

Existence and level of implementation of mechanisms to assess short, medium and long-term investment and operational needs and ensure the availability and sustainability of such finance (9) |

n/a (1) |

4 |

||

|

Existence and level of implementation of policy frameworks and incentives fostering innovation in water management practices and processes (10) |

3 (2) |

4 |

||||

Note: OECD assessment in brackets. Key: 1 = Not in place; 2 = Framework under development; 3 = In place, not implemented; 4 = In place, partly implemented; and 5 = In place and fully functioning. Top figure = NESDC analysis, Figure in brackets = OECD analysis.

Source: (OECD, 2018[5]).

Northern provinces need to centralise data to improve the management of disaster risk and water resources. One of the main results of the MDCR is the lack of harmonised and centralised data on the impact of floods and water usage. In order to enhance the management of natural resources and prevent future losses from floods and droughts, the North could pioneer a new harmonised and accessible dataset of water security. Table 4.8 proposes a series of indicators that this dataset could include.

Table 4.8. Enhance data capability to measure water security

|

SDG |

Indicator |

2013 |

2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Measuring water usage |

|||

|

|

Produced municipal wastewater per year (109 m3/year) |

||

|

Collected municipal wastewater per year (109 m3/year) |

|||

|

Treated municipal wastewater per year (109 m3/year) |

|||

|

Total water withdrawal (109 m3/year) |

|||

|

Agricultural water withdrawal (109 m3/year) |

|||

|

Industrial water withdrawal (109 m3/year) |

|||

|

Municipal water withdrawal (109 m3/year) |

|||

|

Agricultural water withdrawal (% of total water withdrawal) |

|||

|

Industrial water withdrawal (% of total water withdrawal) |

|||

|

Municipal water withdrawal (% of total water withdrawal) |

|||

|

Measuring disaster impact |

|||

|

|

Flood duration per year |

116* |

|

|

Total deaths by flood per year |

195* |

||

|

Total number of people affected by flood per year |

2 000 000* |

||

|

Damage caused by flood by type per year (USD 000) |

8 100* |

||

|

Number of droughts per year |

|||

|

Total deaths by drought per year |

|||

|

Total number of people affected by drought per year |

|||

|

Damage caused by drought per year (USD 000) |

|||

Note: The latest figures measuring the impact of floods that are available only for the North date back to 2005 (Singkran, 2017[6]; FAO, 2016[7]).

Going forward: Measuring the SDGs at regional level for an integrated performance measurement framework

The SDGs are the global tool for measuring multi-dimensional development. The above proposed scorecard links each action to an SDG. However, going forward it would be desirable to collect data on SDG indicators at provincial and regional level in Thailand to allow for an integrated performance measurement framework. As an example of such a framework, Table 4.9 links the expected results of the action plan to the relevant SDG targets. Once data for these SDG targets is available at regional and provincial level this could be used for performance tracking with the same methods and principles as the scorecard presented in this chapter.

Table 4.9. The scorecard is a multi-dimensional tool to track development of the North

|

Goal for the development of the North |

SDG |

SDG target |

|---|---|---|

|

Effective framework for social and economic development of the North |

|

2.4 Ensure the presence of sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, help maintain ecosystems, progressively improve land and soil quality, and strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters. |

|

|

8.2 Achieve higher levels of economic productivity through diversification, technological upgrading and innovation, including through a focus on high value added and labour-intensive sectors. |

|

|

|

9.b Support domestic technology development, research and innovation in developing countries, including by ensuring a conducive policy environment for, inter alia, industrial diversification and value addition to commodities. 9.2 Promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and increase significantly the share of employment of industry and GDP, in line with national circumstances, and double it in least developed countries. |

|

|

|

17.1 Strengthen domestic resource mobilisation, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection. |

|

|

Northern cities drive regional development |

|

11.a Support positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas, by strengthening national and regional development planning. 11.1 Ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services, and upgrade slums. 11.3 Enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanisation and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries. |

|

Universities and colleges become key drivers of regional development |

|

4.3. Ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university. 4.4. Substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship. |

|

|

8.3. Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalisation and growth of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services. |

|

|

|

9.5 Enhance scientific research and upgrade the technological capabilities of industrial sectors in all countries, in particular developing countries, including by encouraging innovation and substantially increasing the number of research and development workers per 1 million people and public and private research and development spending. |

|

|

Regional actors are empowered to deliver water management responsibilities |

|

6.5 Implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary co-operation, as appropriate. 6.b Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management. |

|

Robust, evidence-based decision making prioritises regional action |

|

6.4 By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity. 13.1 Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries. 13.2 Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. 13.3 Improve education, awareness raising, and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning. |

|

Appropriate infrastructure solutions are selected with adequate capital andO&M budgets allocated |

|

6.1 By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all. 6.3 By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimising the release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater, and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally. 11.5 By 2030, significantly reduce the number of deaths and the number of people affected by disasters and substantially decrease the direct economic losses relative to global GDP caused by disasters with a focus on protecting the poor and people in vulnerable situations. |

Source: Authors’ work.

References

[4] ADB (2016), Asian Water Development Outlook 2016, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/189411/awdo-2016.pdf.

[3] Byun, C. et al. (2018), “A study on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education programs in higher education institutions: A case study of Korean graduate programs”, Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, Vol. 4/3.

[7] FAO (2016), AQUASTAT, http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/data/query/index.html?lang=en (accessed on 21 January 2019).

[1] Jean Imbs, B. and R. Wacziarg (2003), “Stages of diversification”, American Economic Review, Vol. 93/1, pp. 63-86.

[2] Jittrapirom, P. and G. Emberger (2013), Chiang Mai City Mobility and Transport Survey (CM-MTS) Report 2012, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, https://www.ivv.tuwien.ac.at/fileadmin/mediapool-verkehrsplanung/Diverse/Forschung/International/CM-MTS/CM-MTS.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2019).

[5] OECD (2018), Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator Framework and Evolving Practices, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264292659-en.

[6] Singkran, N. (2017), “Flood risk management in Thailand: Shifting from a passive to a progressive paradigm”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 25, pp. 92-100.

Notes

← 1. A province p has a comparative advantage in sector s if the net value added (VA) produced in this sector relative to the overall provincial VA is larger than the relative VA in sector s in the rest of the country (). Formally

A significantly high comparative advantage is such that . See Chapter 2 for more details.

← 2. The Herfindahl-Hirschmann index is defined as:

Where is the index for province p, is the GPP of province p in sector s, is the total GPP of province p, and n is the number of economic sectors (classified according to the International Standard Industrial Classification at the two-digit group level). An index value closer to 1 indicates a province’s economy is highly concentrated in a few sectors (i.e. concentration is very high). On the contrary, values closer to 0 reflect provincial economies that are more homogeneously distributed among a series of sectors.

← 3. Entrepreneurship graduate classes could be both theoretical and empirical. Theoretical classes introduce students to methodologies for the identification of entrepreneurial opportunities, the development of a business model and plan, patent law, accounting and finance, entrepreneurial marketing, HR strategy and venture growth strategy. Hands-on sessions complement theoretical classes with internships and analysis of relevant business case studies.