This chapter discusses the strategic and trustworthy use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the public sector, such as for back-office functions of public-facing digital services. It examines existing strategy efforts in the public sector, how they align to broader European Union (EU) efforts, and potential levers for implementation. It covers real-world use cases, spotlighting large language models and emerging best practices. The chapter looks at the key governance capacities Germany has put in place (e.g. leadership, policy-making authority and co-ordination) and its enablers (e.g. data, funding, procurement mechanisms and skills). A focus on transparency notes actions taken and opportunities for further advancements. Finally, it identifies promising international practices that may provide Germany with lessons and makes seven recommendations for action.

OECD Artificial Intelligence Review of Germany

8. Spotlight: AI in the public sector

Abstract

The use of trustworthy AI in the public sector can significantly impact public policies and services. It can free up a significant amount of public servants’ time, allowing them to shift from mundane tasks to high-value work, increasing public-sector efficiency and effectiveness. Governments can also use AI to design better policies and make better, more targeted decisions, enhance communication and engagement with citizens and residents, and improve the speed and quality of public services. While doing so, they need to ensure that the use of AI systems in the public sector is transparently communicated to citizens, and that the AI systems do not lead to discriminatory outcomes. Germany has embedded AI in the public sector as a strong component of its national AI strategy.

Box 8.1. AI in the public sector: Findings and recommendations

Findings

Germany has solid strategies for public sector AI, though stronger enablers for implementation and co-ordination could drive progress. The 2023 Data Strategy begins to strengthen these.

The establishment of expert-staffed data labs and the 2023 Data Strategy commitment to launch them in every ministry are excellent steps towards adoption of AI in the public sector, horizontal governance and co-ordination.

Despite delays in establishing the Centre for Artificial Intelligence in Public Administration (Beratungszentrum für Künstliche Intelligenz in der Öffentlichen Verwaltung, BeKI) under the Federal Ministry of the Interior and for Community (Bundesministerium für des Innern und für Heimat, BMI), the effort is now underway. The Centre has initiated several projects and is positioned to be a source of guidance on AI use in the public sector. Public-sector organisations could benefit from additional clarification about roles and responsibilities in AI governance between BMI and ministries.

The Federal Government demonstrated its ability to be meticulous and transparent in ad hoc reporting on the use of AI in the public sector. However, the public sector currently lacks systematic monitoring and transparency of AI use.

Recommendations

Strengthen the focus on strategy implementation by publishing a periodically updated roadmap with specific commitments and actions for each goal, laying out responsible entities, allocated budget and milestones, and monitoring mechanisms.

Strengthen co-ordination and collaboration among federal entities, and with Länder and cities, both formally (e.g. councils) and informally (e.g. networks and communities of practices).

Through BMI and its BeKI, ensure the timely issuance of planned guidance on the use of AI in the public sector, which should also clarify the entity’s roles and responsibilities with regards to horizontal policy making for public sector AI efforts.

Encourage ministries to develop guidelines on adopting AI in the public sector in their own contexts, and work with them to ensure these guidelines are consistent with national strategies and governing rules and norms.

Explore the development of front-end (e.g. algorithmic impact assessment) and back-end (e.g. algorithmic auditing) processes and guidelines.

Consider developing a central, public, searchable registry of AI systems in use in the public sector. Depending on if and how the previous recommendation is implemented, this could be done automatically.

Consider baseline training for all civil servants whose roles directly or indirectly involve using or being impacted by AI.

Strategic approach to AI in the public sector

Germany's AI strategy incorporates AI into public sector efficiency, open government data (OGD), and security. Its concrete actions and clear objectives include improving service delivery and emergency response capabilities. It complements national and EU strategies, emphasising human-centred AI and public-private partnerships to enhance public services and security.

Germany put in place solid strategies for AI in the public sector

Like most countries that have developed a national AI strategy, Germany embedded AI in the public sector as a strong component of its 2018 national strategy. While several parts have indirect implications for AI use in the public sector, two sections can be seen as particularly relevant: “Using AI for tasks reserved for the state and administrative tasks” and “Making data available and facilitating its use”. Across these, three main topics emerge:

Public sector efficiency and effectiveness. The potential to utilise AI to improve services delivered by the public sector with regards to their efficiency, quality, and security. This could make administrative processes easier to understand and reduce processing times for citizens.1

Open Government Data. One key priority for the Federal Government is the expansion of open access to government data, which was further strengthened in the 2021 Open Data Strategy.

Internal and external security. The Federal Government affirms its interest in using AI for emergency response and the maintenance of internal and external security. One important component of this is information technology (IT) security, an area in which the Federal Government commits to promoting public-sector research and to ensure the development of adequate expertise for the relevant authorities.

The 2020 strategy update can be characterised as a move towards general capacity-building in the public sector. It also strongly reinforced the security elements of the original strategy, discussing the potential of AI for defending against cyber-attacks, emergency and disaster control, and earth observation.

The new 2023 Data Strategy serves to reinforce these focus areas by highlighting the potential for large language models (LLMs) for both back-end and public-facing activities, as well as highlighting the importance of data as an input to AI systems and proposing the introduction of chief data officers and open data co-ordinators in each federal ministry. It is also committed to identifying and preventing discrimination at the data level.

In some areas the path to implementation is less obvious

Roadmaps and enablers, i.e. clear objectives, specific actions, timeframes, funding, and monitoring mechanisms are essential for driving progress in implementing AI strategies in the public sector (Berryhill et al., 2019[1]).

With regards to public sector efficiency and effectiveness, the national AI strategy sets clear objectives for AI in the public sector: to provide citizens and residents with information and services in a more targeted, accessible, and tailored fashion. However, it generally does not contain granular, specific actions for meeting these objectives.

OGD’s objective is also clear: to make data “open by default”. Compared to public sector efficiency and effectiveness, specific actions regarding OGD are clearer through the combination of the AI strategy, the 2021 Open Data Strategy and the 2023 Data Strategy. For instance, the 2018 strategy called for amending the E-Government Act, establishing a new open data portal, and putting in place specific precautions to protect citizen privacy (e.g. pseudonymisation/anonymisation of data, differential privacy processes). Aside from publishing more data, it discusses actions to facilitate increased access and use.

With regard to internal and external security, the 2018 strategy included some fairly concrete actions, such as social media forensics and steps to protect children against sexualised violence on the internet. The 2020 update introduced more specific actions, including expanding AI-related capabilities of the Central Office for Information Technology in the Security Sector (Zentrale Stelle für Informationstechnik im Sicherheitsbereich, ZITiS), a service provider for all federal security authorities; using AI to monitor climate change and other systemic issues, and more related to law enforcement end defence. In addition, the 2023 Data Strategy introduced specific actions related to using LLMs for a variety of public sector use cases, potentially contributing to all three of the primary focus areas.

Germany has made significant progress on many of its goals outlined in its national AI strategy related to AI in the public sector, particularly in the domains of network- and capacity building and enhanced emergency response. In other domains, such as data, security, and regulation, it appears that many of the goals have not yet been met, though several elements appear to be gaining momentum.

The AI strategy’s public-sector components align with complementary national strategies and the EU Co-ordinated Plan on AI

Overall, the public sector-relevant components of Germany’s AI strategy were explicitly designed to be cohesive with other national strategies issued by the Federal Government, and they do indeed appear well‑aligned. Other strategies include the Digital Strategy, Data Strategy, Open Data Strategy, the High-Tech Strategy 2025, the Government Digitalisation Strategy, and the Startup Strategy (BMWK, 2022[2]). Relevant strategies published by individual ministries, such as the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF) Digital Strategy are also consistent with the broader federal strategies.

Vertically, the national AI strategy is well aligned with the EU Co-ordinated Action Plan on AI. Alignment with strategies and guidelines from the EU appear particularly important for AI in the public sector. For instance, the European Union Regulation on Artificial Intelligence (the “EU AI Act”) (EU, 2024[3]) takes a risk-based approach to AI use cases. Many AI systems used by the public sector may fall under heightened risk designations due to their connections with critical infrastructure and citizen services and benefits.

Components of Germany’s national strategies relevant to AI in the public sector are also generally aligned with the EU co-ordinated plan (EC, 2018[4]). For instance, they address human-centred AI, although they do not include specific implementation actions. Human-centred AI has also been reinforced in the guidelines of a number of individual ministries (BMAS, 2023[5]).

The EU co-ordinated plan also encourages the use of AI across domains, from fighting climate change to enhancing security and curing diseases. As discussed in other parts of this section, these goals are also a high priority for the envisioned use cases for using AI in German public services. The EU co-ordinated plan mentions the trade-offs between using AI for security while still maintaining other standards and values, a tension that is also brought up in the German AI strategy.

The EU co-ordinated plan calls for more public-private partnerships, especially with start-ups and innovators. The 2018 strategy also calls for this, with the 2020 update calling for targeted public procurement processes and GovTech approaches to strengthen economic development among businesses that can, in turn, generate AI solutions for public sector use.

AI use cases in the German government

AI is increasingly used at national, state, and local levels across Germany

Germany tends to have lower public sector digital maturity and digitalisation of public services compared other OECD and peer countries (OECD, 2020[6]; bidt, 2023[7]; EC, 2022[8]). This includes a lack of networking between government databases, in part due to Germany’s federal structure, which limits the ability to leverage public sector data as fuel for AI.2

Despite this context, there is already a wide variety of public sector AI initiatives at both national and subnational levels of government (Evers-Wölk, Kluge and Steiger, 2022[9]; Engelmann and Puntschuh, 2020[10]). The 2023 Government AI Readiness Index by consulting firm Oxford Insights (2023[11]) ranks Germany eighth out of 193 countries in terms of its government’s capacity to integrate AI into the public administration for the public good.3 Current use cases span the spectrum from front-office, public facing applications to back-office systems that help civil servants engage in the business of government (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1. Best practice examples of AI in the German public sector

|

Example |

Key characteristics |

|---|---|

|

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is used to answer citizen’s questions about the Covid-19 pandemic and current restrictions, making them less dependent on opening times and response times of relevant authorities. |

|

|

A system that classifies and extracts information from documents (specifically Immatriculation Certificates) parents need to submit to be eligible to receive child assistance. The system checks submitted documents for a) whether it is a valid certificate (and with what probability it is), b) whether it is for the right child, c) whether it is for the right semester and d) whether it comes from a recognised German university. The system suggests a decision that is then approved by a human. |

|

|

Indoor robots measure buildings with laser scanners and cameras. From the data it obtains, it builds a 3-D model that can be used on mobile devices. This enables blind and disabled people to autonomously navigate office buildings of administrative entities. |

|

|

Light sensors track the traffic situation at a given intersection. The extracted data are used to control traffic lights at various intersections. Claimed results include reduced transit times (by 25%), reduced environmental pollution and reduced noise levels. |

|

|

Automated image recognition is used to differentiate between child pornography and similar but legal images (e.g. from family holidays). Selected images flagged as abuse/pornography are forwarded to staff. |

|

|

Evidence (publicly accessible data like news reports, NGO reports, socio-economic indicators and climate data) is gathered and a multifactorial analysis is conducted to assess the likelihood of emerging political crises (called PREVIEW: Prediction Visualisation and Early Warning). The risk of conflict and expected fatalities can be predicted. Results are escalated to human staff that conduct qualitative assessments. |

|

|

A LLM assists public servants by summarising texts for them, streamlining the work on cabinet bills by improving interoperability, assists in background research and generates text from human input (see Box 8.2 for additional details). |

|

Note: The source material did not always provide the exact name of the use case.

Source: Analysis of Engelmann, J. and M. Puntschuh (2020[10]), AI in Authorities’ Use: Experiences and Recommendations, https://www.oeffentliche-it.de/documents/10181/14412/KI+im+Beh%C3%B6rdeneinsatz+-+Erfahrungen+und+Empfehlungen.

Dozens of initiatives are directly related to AI in the federal public administration, with an allocated budget of EUR 193 million (Bundestag, 2023[12]). The majority of these initiatives focus on back-office tasks, with the largest proportion of current uses involving improving government efficiency (e.g. motor vehicle administration), though some also touch on public sector integrity (e.g. monitoring financial requirements, payment tracking, and fraud prevention), scientific research (e.g. plant and weather research), public health (e.g. disease anomaly tracking), and civil security (e.g. early crisis detection, investigating deepfake detection, cyber threat defences). Some current efforts involve public-facing services, such as chatbots to answer questions related to motor vehicle taxes and customs laws, with more planned for the future, including voice assistants.

AI is also increasingly used at sub-national levels in states and cities, with a larger proportion focused on public-facing services. This is to be expected, as sub-national governments, especially cities, tend to have the closest contacts with the public. Besides the use of language models (LMs), discussed below, AI can be seen in service robots and automated services, such as:

The city of Ludwigsburg uses the ServiceRobot L2B2 to greet people in the entrance area of the local city office and to provide information about responsibilities across offices.

The city of Karlsruhe has established a “completely digital local city office” in which citizens can handle their concerns independently in an entirely digital process.

With the help of the so-called Speed Capture Station, citizens of the city of Aschaffenburg can capture biometric photos, fingerprints, and signatures themselves on site in the citizen service office before they apply for an ID card or passport. This eliminates the time-consuming process of capturing the various biometric data at service counters and the need to bring passport photos with them.

Spotlight on language models

At the sub-national level, a number of cities are using LM-based tools to facilitate public services. The cities of Heidenheim and Heidelberg both use chatbots to help citizens and residents find information in a conversational manner. The state of Baden-Württemberg also has chatbots for citizen tax inquiries, and as a back-office took for public servants (Box 8.2). The state of Bavaria, too, uses a chatbot to help provide citizens with information on 2 800 different services (Initiative D21, 2023[13]).

Box 8.2. F13 in Baden-Württemberg

Introduced by the innovation laboratory Baden-Württemberg, F13 is a LM developed to assist public servants with their daily tasks, freeing them up and increasing their capacity to work on important projects by streamlining their work processes.

F13 was designed to:

Summarise long texts. Administrators can choose different levels of compression, although a final review by a human is recommended.

Streamline the work on cabinet submissions and bills. Comments from documents are automatically uploaded and shared with collaborators, and updates as well as status reports can be downloaded by staff members.

Assist in research. Public servants can ask questions about documents they upload or questions relating to a database of legislative and official documents (including protocols from plenary meetings, etc.). Example: “What measures are currently being considered for encouraging commuting to work by bicycle?”.

Generate text from human input. Users can upload documents (including notes, studies, etc.) which are then synthesised into a coherent text. Adjustable parameters include the length and the thematic focus of the text. Example: “Summarise the current state of the discourse around the move to regenerative energies”.

Source: Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg (2023[14]), “Künstliche Intelligenz in der Verwaltung”, https://stm.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/service/presse/meldung/pid/kuenstliche-intelligenz-in-der-verwaltung.

AI-based voice assistants are also increasingly used in Germany. Since March 2019, Fraunhofer Institute for Open Communication Systems (Fraunhofer-Institut für Offene Kommunikationssysteme, FOKUS) and Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology (Fraunhofer-Institut für Digitale Medientechnologie, IDMT) have been working together on the project Speech Assistance for Citizen Services (S4CS). The goal is to develop an AI demonstrator that supports citizens in applying for administrative services through simple and intelligent communication in natural language. An example is applying for parental allowances, which has been tested in the city of Hamburg.

While LMs feature heavily in some of the use cases, LLMs and their use in the public sector have only recently started to be mentioned in the 2023 Data Strategy, according to which a simplification of unstructured data use for LLMs is planned. An examination of possible use cases is also foreseen, with a special focus on respecting data security, data protection and digital sovereignty. This process will be accompanied by BeKI, the Algorithm Assessment Centre for Authorities and Organizations with Security Tasks (Algorithmenbewertungsstelle für Behörden und Organisationen mit Sicherheitsaufgaben, ABOS), the Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (Bundesbeauftragter für den Datenschutz und die Informationsfreiheit, BfDI) and the data laboratories. The BMI also plans to develop overarching guidance on the use of LLMs in 2024 through BeKI. Switzerland recently issued guidance on the use of generative AI tools in the public sector (CNAI, 2023[15]), promoting responsible experimentation and specifying precisely what types of uses are allowed and prohibited, which may be a useful reference as Germany continues to explore this space.

Transparency on public-sector use of AI could be enhanced

The German Federal Government has demonstrated its ability to identify all AI initiatives and uses underway in the public sector and to report on them in a public and transparent manner. However, the strongest instance of this has occurred in response to a parliamentary inquiry from the political opposition (Drucksache, 2022[16]). As a result, Germany published details on federal ministries and subordinate ministries current and planned uses of AI, representing over 35 entities and nearly 80 use cases.

Such tracking and transparency can help inform citizens and build trust in how the public sector uses AI. While German citizens are open minded regarding the use of AI in the public sector, they often do not understand its potential benefits nor understand where and how AI and algorithmic systems are being used (Initiative D21, 2023[13]). Despite the huge potential to leverage this technology for public sector purposes, the 2023 Data Strategy lacks concrete plans for universal requirements and transparency standards for these systems that are, according to AlgorithmWatch (AlgorithmWatch, 2023[17]), already used in public administration. The Federal Government could take a more proactive stance in this regard by advocating and facilitating transparency measures, for example through the establishment of an open, searchable register of AI solutions used in the public sector. BMI officials reported that the development of such a register is underway as a project of BeKI, with a minimum viable product expected in the first half of 2024. In developing such a product, the AI registers of Helsinki (Finland) and Amsterdam (Netherlands) could be used as informative reference examples in that they track how algorithms are being used in municipalities (OECD.AI, 2023[18]). Furthermore, Germany could draw inspiration from the United Kingdom (UK)’s Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard, which comprehensively organises how the public sector, including government, should disclose information when using algorithmic tools (OECD.AI, 2023[18]).

Building key governance capacities

High-level support

Success in public sector AI requires governments to set the right tone from the highest levels of government (Berryhill et al., 2019[1]). The inclusion of a solid public sector component in the national AI strategy is one part of this. In addition, OECD interview participants indicated that internal managerial recognition of the importance of AI in the public sector has been clear since the launch of AI system ChatGPT in November 2022, which has generally raised awareness on the technology.

However, another element is strong signalling and communication from national leaders regarding the importance and potential benefits of AI in the public sector. Enhanced visibility on this topic from national leaders could demonstrate that it is a priority and further provide support for public servants at all levels, enabling them to push for innovation and progress. The United States (US) Executive Orders on “Promoting the Use of Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence in the Federal Government” (The White House, 2020[19]), and “Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence” (The White House, 2023[20]) are perhaps the most comprehensive recent examples, as they were issued by the President. The 2023 Executive Order has a strong overarching focus on AI in the public sector.

Policy making, co-ordination, and guidance

Overall, Germany appears to have a relatively low level of centralised policy making and co-ordination of public sector AI efforts in order to support the implementation of the AI and data strategies. However, this seems to be improving, and the Government recently stated that it is working on closer strategic alignment across government entities and on developing relevant procedures for AI (OECD, 2023[21]).

There appears to be a lack of clarity regarding responsibilities for issuing horizontal policies and guidance on AI in the public sector. The BMI is the appropriate entity for this role, with individual ministries responsible for implementation in alignment with their own mission and institutional context. BMI's guidance is to be provided through BeKI. Its establishment has been announced and is currently being built, although not at the necessary speed. BMI also plans to provide formal policies and guidance in 2024, as requested by several ministries.

Most of the work on AI in the public sector is handled by and within ministries, which can have different rules for if, when and how AI is used (Handelsblatt, 2023[22]). This may lead to inconsistency in approaches and the ability to learn lessons from experience, and to duplication of efforts in different ministries. Some ministries have put in place solid guidance on AI design and adoption that could serve as a model for others (BMAS, 2022[23]), while other ministries have not formalised an approach. For the implementation of AI efforts, ministries are often reliant on the co-operation of the Länder, which have recently been criticised for moving too slowly on incorporating AI into the public sector (Deutschlandfunk, 2023[24]).4

There are at present few mechanisms for horizontal co-ordination for public sector AI activities across the Federal Government. While semi-annual invitational events for ministries to discuss AI projects have been taking place in 2023, there is little evidence of more integrated co-ordination mechanisms at the national level. In other countries, such mechanisms take the shape of formal structures (e.g. inter-ministerial councils) and informal co-operation channels (e.g. networks and communities of practice). However, German official stated that they are taking steps to address this through BeKI, which will be responsible for cross-government co-ordination. Some pilot efforts are already underway, with several meetings and exchanges held on various topics (e.g. how to use LLMs in the public sector, what AI infrastructure is appropriate in the public), with members also able to connect organically and horizontally.

Transversal co-ordination with sub-national governments also appears limited, though the IT Planning Council (IT-Planungsrat) has been set up to co-ordinate the work of Germany’s Federal and State Governments on matters relating to IT technology and has begun work to address AI co-ordination challenges. Its Federal IT Co-operation (Föderale IT-Kooperation, FITKO) has been created to co-ordinate and advance the digitisation of public administration (FITKO, 2023[25]). This is a common challenge in countries with a federal structure and remains perhaps one of the more difficult issues to address.

The 2023 Data Strategy includes plans to establish interconnected data laboratories with Chief Data Officers/Scientists and Open Data Co-ordinators within each federal ministry. These labs have already been launched in all ministries, receiving strong support and recognition as signs of success from interviewees. Similar actions have been taken by other countries, such as the US, with generally positive effects (Federal CDO Council, 2023[26]). Relatedly, a co-operation platform for data labs has been put in place called IMAG.

Such efforts are a step in the right direction and can help promote systems synergies and collective learning while avoiding duplication and overlap. Some existing promising practices with regards to forming cross-government networks or communities of practice could help inform or inspire German efforts, with some examples including Brazil’s National Digital Government Network (Brazilian Government, 2023[27]), Chile’s Network of Public Innovators, and the AI Community of Practice in the US (Centers of Excellence, 2023[28]).

While existing cross-cutting efforts are limited but growing, some success is apparent within individual ministries. In particular, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, BMAS) has developed a collaborative network for interaction and exchange, the Network Artificial Intelligence in Employment and Social Protection Services, which began with a push by the ministry but is now growing organically to include more than 20 organisations. The network has been active in developing informal guidelines on how to implement AI in the public sector in a human-centred and trustworthy way, according to the BMAS officials interviewed. Such a model could be helpful in bridging siloes across ministries and could inform BMI efforts.

In terms of reaping the results and benefits of AI, the national AI strategy calls for “cross-project incentives for a sustainable utilisation of results, for instance by making algorithms available in open-source form, by disclosing the prepared project data, for instance as open AI training data, or by researchers liaising closely on best practices as well as on any setbacks and problems encountered”. This approach is very promising, though the OECD could not find evidence of its implementation, and German officials interviewed were somewhat unsure to what extent any existing efforts would qualify under this, though they believed that Germany’s new Data Strategy would help make data more transparent.

Promoting accountability

The Trusted AI initiative and the ABOS aims at facilitating accountability, such as through impact assessments, for entities with a high need for data protection and for those involved in security. However, such efforts are at an early stage.

For both security entities and beyond, Germany could look to best practices established by other countries with regards to front-end algorithmic impact assessment, which can help public officials take a risks-based approach to AI accountability before deployment, as well as back-end auditing processes to ensure AI systems are functioning in a trustworthy manner after deployment (OECD, 2023[29]; Ada/AI Now/OGP, 2021[30]). In terms of the front-end aspects, best practices can be provided by the Canada’s Directive on Automated Decisions Making and associated Algorithmic Impact Assessment (Government of Canada, 2023[31]), Chile’s General Instruction on Algorithmic Transparency (Consejo para la Transparencia, 2023[32]), and the US Government Accountability Office (GAO)’s AI Accountability Framework (US Government Accountability Office, 2023[33]). With regards to retrospective auditing, solid examples include the Netherlands Court of Auditors (NCA) algorithmic auditing framework. Germany’s own Supreme Audit Institution also jointly developed an AI auditing white paper with Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, and the UK that can support efforts in this direction (auditing algorithms, 2023[34]).

Strategic foresight and anticipation

Overall, little work is done on anticipatory governance of public sector AI. One notable exception is the GIRAFFE project (Government Insight, Research, Analytic, Foresight, Function and Exploration) of the BMI which has as an explicit goal to aid the digital transformation of the administration. Some ministries like the BMBF outsource their foresight engagements to private actors, and the Federal Government commissions research by research institutes into strategic foresight. Additional efforts that are not AI-specific but relevant to the increasing use of AI in the public sector are the Competence Centre for Strategic Foresight (Kompetenzzentrum Strategische Vorausschau) which focuses on security policy and is housed under the Federal Academy for Security Policy (Bundesakademie für Sicherheitspolitik, BAKS), a roundtable for strategic foresight where all federal ministries are involved and a Future Council that briefs the chancellor (Zukunftsrat des Bundeskanzlers). Somewhat less directly the Competence Centre for Public IT (Kompetenzzentrum Öffentliche IT, ÖFIT), which is externally situated but funded by BMI, serves as a contact and think tank for the digitalisation of the public sector and seeks to take a systems approach considering emerging trends and new developments (BIH, 2023[35]).

Putting critical enablers in place

Open government data

Beyond its role to strengthen democracy and public governance, OGD remains important for fostering innovation, including the development of new public and private sector services and business models. Overall, OGD is a foundational element for advanced digital governments. By increasingly integrating with data-intensive systems like AI, OGD becomes a key input for data-driven decision making within and outside the government, feeding into better policies and services. It also contributes to the trustworthiness of automated decisions by serving as a reliable and traceable data source.

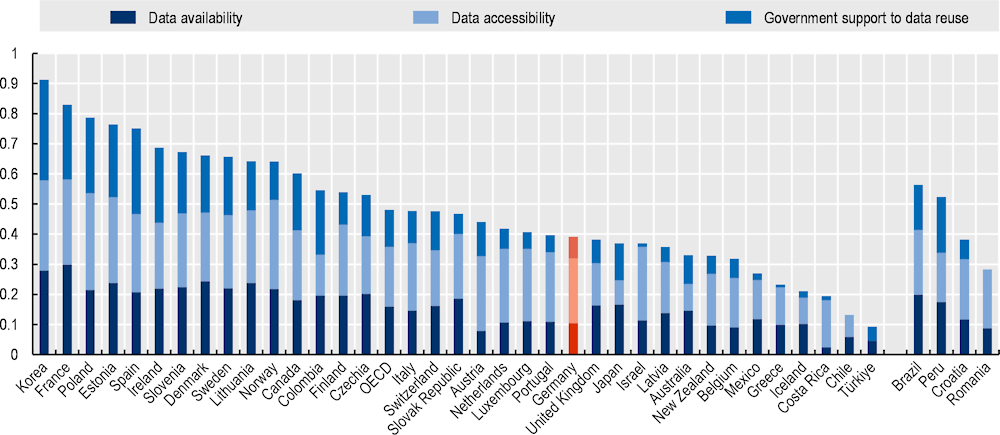

According to the 2023 OECD Open, Useful, and Re-usable data (OURdata) Index, which benchmarks efforts made by governments to design and implement national OGD policies, Germany lags considerably in data availability and support to data re-use (Figure 8.1), even though data accessibility is relatively high.

Figure 8.1. Germany performs below the OECD average in data availability and re-use, above on data accessibility

Source: OECD (2023[36]), 2023 OECD Open, Useful and Re‑usable data (OURdata) Index: Results and key findings, https://doi.org/10.1787/a37f51c3-en.

Enhancing internal expertise and resources

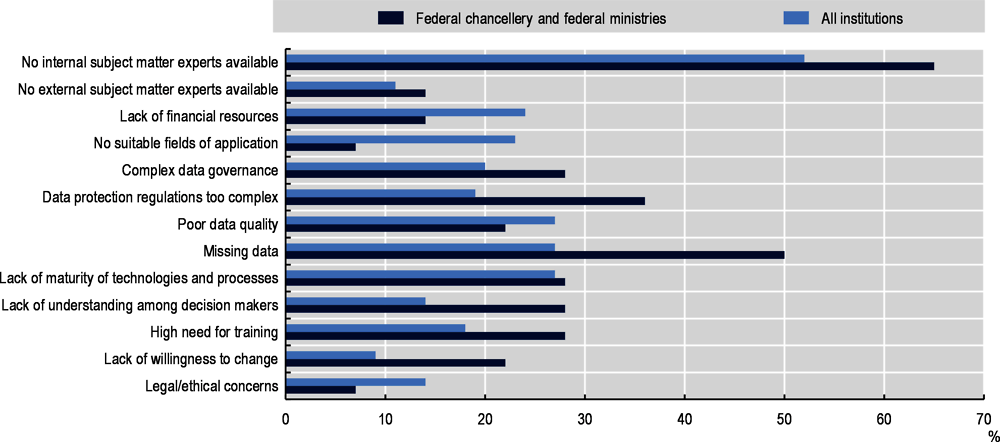

Talent development and expertise acquisition are of crucial importance to the Federal Government.5 Although the need to develop AI expertise within the public sector is acknowledged in the national AI strategy, no implementation details or concrete plans are provided. A 2021 survey found that the number one issue in using AI in the public sector may be the lack of internal expertise (Figure 8.2; however, BMI officials suggest this may no longer be the case due to new upskilling efforts and the recruitment of experts, such as those staffed to the data labs.

The recruitment of experts to work in the data labs was cited as a success by several interviewees, though, as common in other countries, the pay rate relative to the private sector was raised as a challenge. Interviewees also noted that literacy in data and AI of existing public servants was limited and that some baseline level of mandatory training could be helpful. Suggestions ranged from the reinforcement of courses already available (e.g. from the Digital Academy) to strengthening the role of the data labs in promoting AI literacy in their respective ministries.

Initiatives like Lower Saxony’s Competence Centre for AI in Public Administration (KI-Kompetenzzentrum für die niedersächsische Verwaltung, KiKoN), with a goal to promote and accelerate the use of AI in public administration, exist only in individual states (Niedersachsen, 2023[37]); or with specific entity’s or subject domains, as is the case of Competency Centre for AI in the Federal Office for Information Security (Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik, BSI) (BSI, 2023[38]). Externally, the BMI funds the Competence Centre for Public IT (Kompetenzzentrum Öffentliche IT) which serves as a think tank and partner for matters of public IT, with a focus broader than just AI. Lastly, the private sector has filled some gaps by providing courses and classes teaching public service employees about the basics of AI (bitkom, 2023[39]).

Figure 8.2. Lack of in-house expertise is a key challenge of AI use in the public sector

Challenges in using data analytics and artificial intelligence in the public sector in %, 2021

Source: Bundesrechnungshof (2023[40]), Processes of Data Analysis and Artificial Intelligence in the Federal Administration, https://www.bundesrechnungshof.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Berichte/2023/ki-da-volltext.pdf, based on German Federal Audit Office survey conducted in October 2021.OECD interviews found mixed views on internal skills and expertise.

Governments can obtain the necessary human capital internally through innovative approaches to training and recruiting in new talent. Germany has done an excellent job in doing this with regards to the recruitment of experts in the data labs that have been launched so far. External promising practices that could help inform or inspire approaches in Germany include an AI training curriculum in the US, which was required as part of the AI Training Act to train and upskill the federal workforce on AI (US Congress, 2022[41]).

Securing external expertise and resources

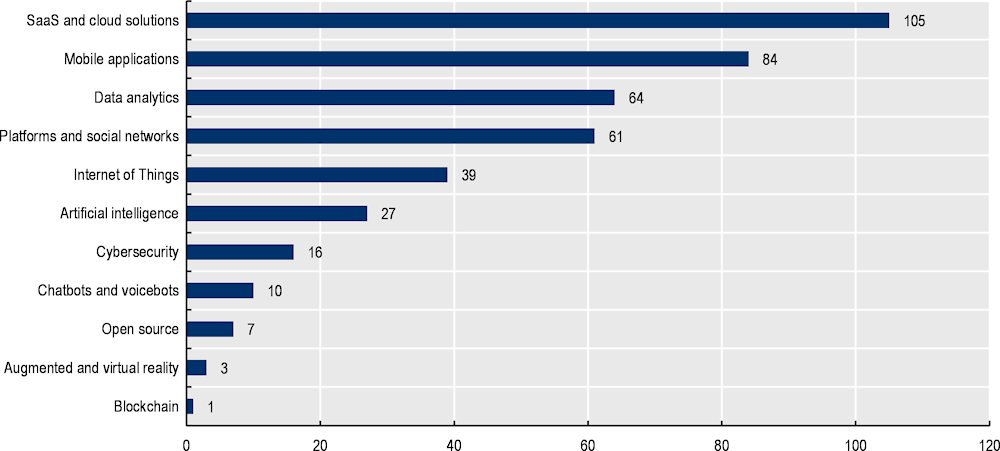

The national AI strategy includes plans to streamline and leverage public procurement processes to incentivise AI-based and open-source solutions provided by the private sector, especially by start-ups. In 2021, Germany had around 300 GovTech start-ups, with an annual growth rate in the three-digit range. Almost half of these are providing solutions for municipalities rather than for the federal government, mostly as cloud solutions and apps, with AI applications still being limited (Figure 8.3).

However, interviewees reported challenges in accessing public procurement opportunities for innovative solutions (see Chapter 4). The GovTech Campus Germany runs the Open Innovation Platform, where new ideas are being developed to make digital procurement solutions accessible to administrations at all levels of government. In its start-up strategy from 2022, the Federal Government commits to encourage and support public administrations in their co-operation with the tech scene to develop and test different use cases for AI systems, for instance through programmes like AI for Government, which provides infrastructure and compute capacity to businesses to promote AI solutions that can be incorporated by the public sector (BMWK, 2022[2]). The federal government also supports a programme called Procurement for Government. Finally, GovTech companies can also be supported by the Digital Hub Initiative, a project co-ordinated and overseen by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz, BMWK).

Figure 8.3. Start-ups are providing technology solutions to the German government

Number of GovTech start-ups in Germany, 2021

Source: GovMind (2021[42]), GovTech in Germany: A Systematic Market Review, https://govmind.tech/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/20210607-GovMind-GovTech-in-Deutschland.pdf.

With regards to public procurement for AI, some potentially promising practices in other countries include the Government of Canada’s AI Source List for the promotion of innovative procurement (Government of Canada, 2023[43]). AI Procurement in a Box from the OECD.AI Catalogue of Tools and Metrics may also be helpful (OECD.AI, 2023[44]).

Infrastructure

The national AI strategy outlines Germany’s plan to establish a centralised and openly accessible national data infrastructure complete with a cloud platform and the necessary computing capacity. However, there is no evidence to demonstrate that a national data architecture has been developed.

Regarding interoperability, the 2023 Data Strategy affirms that guaranteeing the interoperability of systems will be crucial for ensuring competitiveness, although this is mostly focused on businesses rather than public administration. Support is also expressed for open specifications and the use of international norms and standards for technologies like AI and Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT). Concretely, the strategy references GAIA-X as an example of an open and decentralised European data infrastructure, making use of shared rules, open-source code and standards for interoperability.

Learning from others

This chapter has sought to introduce promising practices from other governments pursuing relevant efforts regarding AI in the public sector. While no comprehensive comparative assessments exist regarding AI in the public sector, some work has identified potential opportunity areas for other countries that may be worth considering for Germany.

Although much larger in size, the US is well placed to serve as a peer for comparison when it comes to AI in the public sector, as it has similarities to Germany in its federal structure and has also placed a strong emphasis on the topic, including through two aforementioned Executive Orders. A recent report from the US GAO (2023[45]) reviews important requirements in adopting AI in the public sector and assesses public sector organisations’ action on achieving them. It takes into consideration over 1 200 current and planned public sector AI use cases. The report could provide useful lessons and help Germany avoid potential pitfalls. Key findings and recommendations touch on:

the development of public roadmaps for implementing strategy and policy guidance

the development and updating of public AI use case inventories

the issuance of government-wide policies and guidance on AI in the public sector

designating Responsible Artificial Intelligence Officers (RAIOs) – later renamed Chief Artificial Intelligence Officers (CAIOs) – in each top-level public sector department, charged with overseeing and co-ordinating AI plans and action and managing use case inventories

establishing, and conducting needs assessments, for public servant occupations related to AI.

The OECD’s comparative review of the use of AI in the public sector of Latin America and the Caribbean may also yield relevant approaches from the region (OECD/CAF, 2022[46]).

Recommendations

Strengthen the focus on strategy implementation

The existence of roadmaps and enablers is important for the implementation of AI strategies in the public sector. Germany’s strategy includes solid high-level objectives but is light with regard to achieving them through granular, actionable and clear steps. Such a roadmap could leverage the growing momentum around AI in the public sector in Germany and direct it towards the goals and objectives of the strategy in a systemic way.

Strengthen co-ordination

As there are various levels of planning for and using AI across and within levels of government in Germany, stronger co-ordination can help Germany take a systems approach to achieve strategic goals while minimising duplication, overlap, and fragmentation of efforts. Formal mechanisms, like councils, can hold ministries and other public sector entities accountable for achieving national strategic goals. Informal mechanisms, such as networks, can build capacities and connections among public servants through sharing experiences and lessons, and navigating the hurdles of adopting new technologies and approaches. Like other countries with a federal structure, co-ordination between the federal and subnational governments is likely to be the most challenging aspect, necessitating additional and dedicated efforts to build such touchpoints, perhaps through the IT Planning Council (IT-Planungsrat).

Clarify roles and expand guidance for the implementation of AI in the public sector

A lack of clarity about responsibilities for issuing policies on the use of AI in the public sector might limit progress in AI exploration and adoption. Clarification of roles can help empower an entity to take ownership and action over designing and issuing guidance, and thus give other public sector organisations boundaries, scope of action, and paths for achieving national strategic objectives. This can ensure that entity-specific strategies and guidance align with horizontal, federal efforts and goals.

Explore the development of algorithmic impact assessment and auditing processes and guidelines

Germany is exploring how to put in place accountability mechanisms such as algorithmic assessments for public-sector entities dealing with sensitive data or security issues. However, such mechanisms can be useful in a broader range of AI cases. Some countries, like Canada, require impact assessments for all instances of automated decision making, with low-impact systems facing minimal risk-mitigation requirements and higher-impact systems having addition responsibilities to uphold. Likewise, audit frameworks can ensure that deployed AI systems remain trustworthy. Germany should consider whether such approaches would enhance accountability for public-sector use of AI in the country.

Increase the transparency of AI use in the public sector

Much reporting on public-sector AI use cases has been prompted by parliamentary inquiry. Proactively maintaining an updated registry of public-sector use cases could build accountability regarding AI in the public sector and trust among citizens and residents. Creation of such a system could be automated. For instance, if public-sector organisations were required (as in Canada) to publish impact assessments as open data, an automated system could harvest these files to populate a registry.

Strengthen AI-related skills in the public sector

The creation and staffing of expert-driven data and AI labs in the German public sector is considered a success and significant step. However, as AI becomes more ubiquitous and Germany increases the adoption of trustworthy AI in the public sector, it might need to focus on upskilling workers already in public service and new hires without AI expertise. This could involve training in AI basics for public servants who might use or encounter AI in performing their duties, and more in-depth technical training for some, creating a pathway besides external recruitment for cultivating AI expertise.

References

[30] Ada/AI Now/OGP (2021), Algorithmic Accountability for the Public Sector, Ada Lovelace Institute, AI Now Institute and Open Government Partnership, http://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/algorithmic-accountability-public-sector.

[17] AlgorithmWatch (2023), “Statement on the data strategy of the Federal Government”, https://algorithmwatch.org/de/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Stellungnahme-Datenstrategie.pdf.

[34] auditing algorithms (2023), Auditing machine learning algorithms - A white paper for public auditors, https://www.auditingalgorithms.net./.

[1] Berryhill, J. et al. (2019), “Hello, World: Artificial intelligence and its use in the public sector”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 36, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/726fd39d-en.

[7] bidt (2023), Autorinnen und Autoren: Das bidt-Digitalbarometer. international, Bayerisches Forschungsinstitut für Digitale Transformation, https://doi.org/10.35067/xypq-kn68.

[35] BIH (2023), Kompetenzzentrum Oeffentliche IT, https://www.oeffentliche-it.de/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[39] bitkom (2023), “eGovernment: AI basics for public sector employees”, https://bitkom-akademie.de/zertifikatslehrgang/egovernment-ki-grundlagen-oeffentlicher-dienst (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[5] BMAS (2023), Selbstverpflichtende Leitlinien für den KI-Einsatz in der behördlichen Praxis der Arbeits- und Sozialverwaltung, Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Publikationen/a862-01-leitlinien-ki-einsatz-behoerdliche-praxis-arbeits-sozialverwaltung.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[23] BMAS (2022), Guidelines for the Use of AI in the Governmental Practice in Labour and Social Affairs, Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Publikationen/a862-01-leitlinien-ki-einsatz-behoerdliche-praxis-arbeits-sozialverwaltung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[2] BMWK (2022), Start-up Strategy, Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Existenzgruendung/start-up-strategie-der-bundesregierung.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[27] Brazilian Government (2023), Rede Nacional de Governo Digital, https://www.gov.br/governodigital/pt-br/transformacao-digital/rede-nacional-de-governo-digital.

[38] BSI (2023), Künstliche Intelligenz, https://www.bsi.bund.de/DE/Themen/Unternehmen-und-Organisationen/Informationen-und-Empfehlungen/Kuenstliche-Intelligenz/kuenstliche-intelligenz_node.html#doc451100bodyText3.

[40] Bundesrechnungshof (2023), Processes of Data Analysis and Artificial Intelligence in the Federal Administration, https://www.bundesrechnungshof.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Berichte/2023/ki-da-volltext.pdf.

[12] Bundestag (2023), Einsatz Künstlicher Intelligenz im Geschäftsbereich der Bundesregierung, https://dip.bundestag.de/vorgang/einsatz-k%C3%BCnstlicher-intelligenz-im-gesch%C3%A4ftsbereich-der-bundesregierung/298588 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[28] Centers of Excellence (2023), Community of Practice: Artificial Intelligence, https://coe.gsa.gov/communities/ai.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[15] CNAI (2023), Instruction sheets for the use of AI within the federal administration, https://cnai.swiss/en/products-other-services-instruction-sheets/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[32] Consejo para la Transparencia (2023), Sector público chileno avanza en inédita normativa de transparencia algorítmica en América Latina, https://www.consejotransparencia.cl/sector-publico-chileno-avanza-en-inedita-normativa-de-transparencia-algoritmica-en-america-latina/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[24] Deutschlandfunk (2023), “Scholz is urging federal states to respond to proposals to reduce bureaucracy”, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/scholz-draengt-bundeslaender-zu-antworten-auf-vorschlaege-zu-buerokratieabbau-100.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[16] Drucksache (2022), “Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Anke Domscheit-Berg, Dr. Petra Sitte, Nicole Gohlke, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion Die Linke”, https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/004/2000430.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

[8] EC (2022), eGovernment Benchmark 2022, European Commission, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/egovernment-benchmark-2022.

[4] EC (2018), Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:22ee84bb-fa04-11e8-a96d-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

[10] Engelmann, J. and M. Puntschuh (2020), AI in Authorities’ Use: Experiences and Recommendations, https://www.oeffentliche-it.de/documents/10181/14412/KI+im+Beh%C3%B6rdeneinsatz+-+Erfahrungen+und+Empfehlungen.

[3] EU (2024), Regulation (EU) 2024/ ...... of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act), https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/PE-24-2024-INIT/en/pdf.

[9] Evers-Wölk, M., J. Kluge and S. Steiger (2022), Artificial Intelligence and Distributed Ledger Technology in Public Administration: An Overview of Opportunities and Risks including the Presentation of Internationally Relevant Practical Examples, Institut für Technikfolgenabschätzung und Systemanalyse, https://publikationen.bibliothek.kit.edu/1000151158.

[26] Federal CDO Council (2023), CDO, https://www.cdo.gov/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[25] FITKO (2023), Fitko, https://www.fitko.de/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[45] GAO (2023), “Artificial intelligence: Agencies have begun implementation but need to complete key requirements”, United States Government Accountability Office, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-105980.

[31] Government of Canada (2023), Algorithmic Impact Assessment tool, https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/digital-government/digital-government-innovations/responsible-use-ai/algorithmic-impact-assessment.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[43] Government of Canada (2023), Artificial intelligence source list, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-services-procurement/services/acquisitions/better-buying/simplifying-procurement-process/artificial-intelligence-source-list.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[42] GovMind (2021), GovTech in Germany: A Systematic Market Review, https://govmind.tech/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/20210607-GovMind-GovTech-in-Deutschland.pdf.

[22] Handelsblatt (2023), Which ministries are already using AI – in surprisingly specific projects, https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/deutschland/kuenstliche-intelligenz-welche-ministerien-ki-bereits-einsetzen-in-erstaunlich-konkreten-projekten/29221386.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[13] Initiative D21 (2023), eGovernment MONITOR 2023, https://initiatived21.de/publikationen/egovernment-monitor.

[37] Niedersachsen (2023), “The state of Lower Saxony establishes a competence centre for artificial intelligence in administration”, https://www.mi.niedersachsen.de/startseite/aktuelles/presseinformationen/land-niedersachsen-grundet-kompetenzzentrum-fur-kunstliche-intelligenz-in-der-verwaltung-219423.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[36] OECD (2023), “2023 OECD Open, Useful and Re-usable data (OURdata) Index: Results and key findings”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 43, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a37f51c3-en.

[21] OECD (2023), G7 Hiroshima Process on Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Towards a G7 Common Understanding on Generative AI, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bf3c0c60-en.

[29] OECD (2023), Global Trends in Government Innovation 2023, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0655b570-en.

[6] OECD (2020), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 03, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

[44] OECD.AI (2023), AI Procurement in a Box, https://oecd.ai/en/catalogue/tools/ai-procurement-in-a-box (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[18] OECD.AI (2023), Database of National AI Policies and Strategies, OECD, Paris, https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/overview (accessed on 5 October 2023).

[46] OECD/CAF (2022), The Strategic and Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Public Sector of Latin America and the Caribbean, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1f334543-en.

[11] Oxford Insights (2023), Government AI Readiness Index 2023, https://oxfordinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/2023-Government-AI-Readiness-Index-1.pdf.

[14] Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg (2023), “Künstliche Intelligenz in der Verwaltung”, https://stm.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/service/presse/meldung/pid/kuenstliche-intelligenz-in-der-verwaltung (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[20] The White House (2023), Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence.

[19] The White House (2020), Executive Order on Promoting the Use of Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence in the Federal Government, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-promoting-use-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence-federal-government.

[41] US Congress (2022), S.2551 - AI Training Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2551.

[33] US Government Accountability Office (2023), Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-519sp.

Notes

Notes

← 1. Germans have for some time been optimistic about this: 68% responded in a survey that they expected AI to be able to speed up administrative processes and more recently, the proportion of people who primary see opportunities in using AI is higher in Germany than in other countries. Another recent survey found that a majority of citizens agree with the use of AI in the public sector so long as certain conditions are met (e.g. if fundamental decisions continue to be made by humans) (Initiative D21, 2023[13]).

← 2. A full review of digitalisation of the public sector is beyond the scope of this study, but making progress in this area will be foundational in achieving the strategic and responsible use of AI in the public sector.

← 3. The index considered 39 indicators across three pillars: i) government (including strategic vision, regulation, ethical considerations, capacities); ii) the technology sector (such as a mature ecosystem of innovative private-sector companies); and iii) data and infrastructure.

← 4. There are varying levels of activity in the development and deployment of AI across Länder, as indicated by the map at https://www.plattform-lernende-systeme.de/ki-landkarte.html. However, this tool is not exclusive to public sector use cases.

← 5. In a survey from 2021, more than half of all surveyed agencies reported a lack of internal experts.