This chapter discusses the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on the world of work, affecting skill requirements, job roles, work organisation and employment relationships. As Germany moves to manage the transformative impact of AI on the labour market, several challenges emerge related to adopting AI in the workplace. These include a lack of comprehensive understanding of AI skill demand, slow progress in including AI skills in vocational training regulations, a lifelong learning system that needs updating and predominantly neutral career guidance. Social dialogue is pivotal in navigating AI transitions, but social partners often lack sufficient AI expertise. In response to these challenges, it is crucial for Germany to improve the anticipation of AI skill demand, actively promote education and training opportunities in AI, fostering flexibility in adult learning, incentivise employer-led AI training, enhance consultations and secure AI expertise at the workplace.

OECD Artificial Intelligence Review of Germany

5. The world of work

Abstract

The 2018 AI strategy and its 2020 update focused on a holistic, human-centred approach that recognises the importance of preparing businesses and workers for the adoption and the responsible use of AI. The strategy highlights three policy levers to achieve these goals: i) actions to strengthen the anticipation and assessment of the skills needed for AI adoption, including the development of skilled-labour monitoring; ii) the development of tools to enable workers to build relevant skills in the context of the German National Skills Strategy; and iii) strengthening the voice of workers in the introduction of AI tools and applications in the workplace.

Box 5.1. The world of work: Findings and recommendations

Findings

National assessment exercises in Germany lack focus on AI skills, hindering understanding of demand despite perceived shortages.

Progress in updating vocational training regulations to include AI is slow, but in practice, employers and training providers can go beyond what is specified in these regulations.

Germany faces challenges promoting lifelong learning for some groups, with implications for the effective upskilling and reskilling of adults for AI adoption.

Public employment services are committed to providing “neutral” career guidance and services, limiting their active role in guiding education and training choices towards AI.

Small initiatives such as futures centres and training consortia address localised gaps in AI skills development by targeting workplace training in AI skills.

The lack of AI-related expertise among social partners and of resources to acquire it are the main challenges faced by social partners to support their members in the AI transition. Insufficient transparency and experiences to cover AI in co-determination are also noted as critical issues.

Several projects have been launched by social partners and federal ministries to offer training and enhance AI-competences, but co-ordination between all these initiatives is an issue.

The German Work Council Modernization Act is generally seen as positive by workers’ representatives but insufficient because it only applies to firms with a work council and falls short of what is needed in terms of co-determination when it comes to AI and algorithmic system.

Recommendations

Collect information on the supply and demand of AI skills through a dedicated analysis in the context of the Skilled Labour Monitor or through an ad hoc study.

Promote education and training opportunities in AI in the context of the Public Employment Services (PES)’ Lifelong Vocational Guidance programme and, more widely, ensure that information on opportunities in AI-occupations is readily available.

Increase flexibility and modularity in adult learning, especially in continuous vocational education and training, by using elective qualifications to integrate AI content for adaptive up- and reskilling.

Incentivise employers to provide AI-related training through capacity-building exercises and targeted subsidies.

Encourage consultations and co-operation with social partners, work council members and employees on AI introduction.

Foster AI-related knowledge in the workplace and facilitate access to external expertise. Create incentives to build AI competences and join forces with social partners to promote AI-related expertise to all stakeholders in the workplace.

Upskilling and reskilling adults for AI

Germany's adult upskilling and reskilling system must become more systematic and flexible to close the skills gap in AI effectively. Employers cite skill shortages as a primary barrier to AI adoption, higher than in several other countries, indicating a need for enhanced skills development. Adult learning system faces challenges, with wide gaps in participation rates across socio-economic groups, impacting AI skill acquisition. While vocational training in Germany slowly incorporates AI, public initiatives and regulation updates are not sufficiently AI-focused.

Skill shortages are a critical barrier to AI adoption

The share of workers with AI skills is small in Germany – as in other OECD countries – but has grown rapidly since 2011. Recent research shows that the average share of workers with AI skills in total employment across the OECD is just over 0.3%, ranging from 0.5% in the United Kingdom (UK) to 0.2% in Greece. The share in Germany is around the OECD average but has increased almost fivefold in the last decade. In all countries, the AI workforce is overwhelmingly highly educated and predominantly male. Women are underrepresented in the AI workforce, especially in Germany (Green and Lamby, 2023[1]).

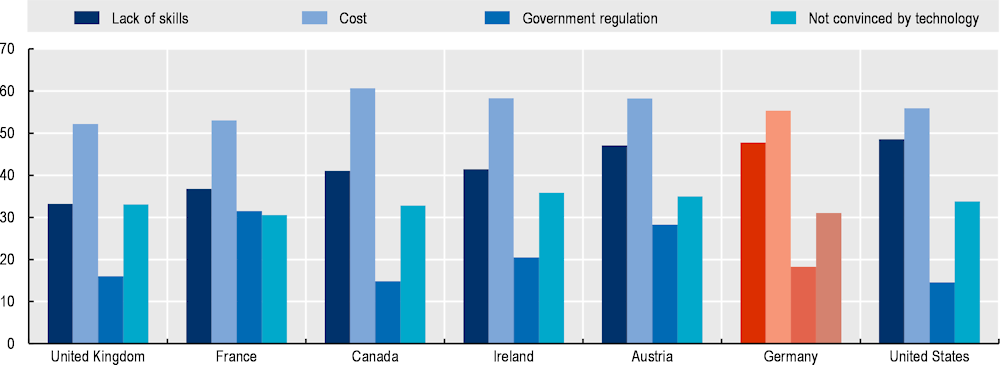

Employers in Germany are more likely to cite lack of skills as a barrier to AI adoption than employers in other countries, notably in Austria, Canada, France, Ireland and the UK (Figure 5.1). 48% of employers in Germany cite a lack of skills as a barrier to adopting AI, a proportion second only to the United States (US), where 49% of employers say the same. Germany faces challenges in supporting adults to develop AI-‑relevant skills.

Figure 5.1. Lack of skills and cost are the main barriers to AI adoption in Germany

Share of employers who cite the following reasons as barriers to the adoption of AI, 2022

Note: All employers were asked: “I’m going to list a few potential barriers to the adoption of artificial intelligence. In each case, please tell me whether it has ever been a barrier to adopting artificial intelligence in your company: High costs/Lack of skills to adopt artificial intelligence/Government regulation/Not convinced by the technology/Any other barriers not previously mentioned”.

Source: Lane, M., M. Williams and S. Broecke (2023[2]), “The impact of AI on the workplace: Main findings from the OECD AI surveys of employers and workers”, https://doi.org/10.1787/ea0a0fe1-en.

The system for upskilling and reskilling adults faces challenges

While adult participation in upskilling and reskilling is slightly above the average of European OECD countries, it lags OECD countries with similar skill development systems, such as Austria, the Netherlands and Switzerland (OECD, 2021[3]). By international standards, Germany has wide disparities in learning participation across socio-economic groups, with low-skilled adults, the unemployed and those on low incomes lagging behind (OECD, 2021[3]). While the launch of the National Skills Strategy (Nationale Weiterbildungsstrategie) in 2019 signalled a commitment to promoting a culture of continuous skills development (BMAS et al., 2019[4]), a recent OECD report on continuing education and training in Germany highlights the continued need to undertake systematic reform of the system for upskilling and reskilling adults (OECD, 2021[3]). The report argues for a more systematic, flexible, and less complex adult learning system in Germany. These recommendations are directly relevant to upskilling and reskilling adults for the successful and reliable adoption of AI. Addressing the issues highlighted in the report is critical to creating an adaptive and effective system capable of meeting the demands of training individuals for AI-related skills in a rapidly evolving technological landscape.

Vocational training regulations tend to be technology-neutral

Training in vocational information technology (IT) skills accounts for a small proportion of all training provided by employers in Germany, but this proportion has increased between 2015 and 2020, according to data from the European Continuing Vocational Training Survey. Looking at the German vocational training system overall, while there are more than 300 vocational training profiles and regulations, there has been relatively little focus on creating specific vocational profiles for AI occupations. Similarly, the process of updating training profiles involving the social partners often takes one to two years, which limits regulations’ ability to respond to sudden technological changes.

Training regulations for some IT occupations, such as information technology specialists, were updated in 2020 (BIBB, 2020[5]). Efforts to update continuous vocational training for IT professions are in progress. A pilot project in Baden-Württemberg – KI B3 – brings together government actors, universities and the Chamber of Commerce to develop continuing vocational training modules and qualifications in AI and machine learning (Vössing, 2023[6]). Yet, these are only relatively modest changes in the broader context of Germany’s vocational education and training (VET) system. According to experts interviewed for this report, the slow pace of change is not necessarily problematic. Training regulations are generally worded in a technology-neutral way and intended to be minimum standards. This allows employers and education and training institutions to incorporate new developments related to AI into the curriculum if they wish.

Several smaller and more targeted public initiatives aim to address workplace training for AI skills, including the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, BMAS) projects Hubs for Tomorrow (Zukunftszentren) (BMAS, 2022[7]), which aims to support companies in the digital transition, and Continuing Education and Training Associations (Weiterbildungsverbünde) (BMAS, 2023[8]), in which several companies and stakeholders in the education landscape and regional labour market actors collaborate to efficiently organise and implement training measures across company boundaries, including in the field of AI.

Training choices are not typically steered towards AI

There is no discernible focus on AI skills when it comes to training supported by the PES, part of Germany’s active labour market policy package. While they can provide information on AI job opportunities, the PES is committed to providing neutral career guidance and support to individuals and enterprises. The extent to which education and training choices are directed towards in‑demand skills is extremely limited (OECD, 2017[9]). Maintaining a neutral stance while preserving individual autonomy may be insufficient to proactively address the urgency of acquiring AI skills in a rapidly evolving labour market.

Anticipating demand for AI skills

Germany's national skills assessment lacks focus on AI. While demand for AI skills is low but rising, no comprehensive data on AI skill needs exist, and existing forecasts overlook AI specifics.

National skill anticipation exercises have no specific focus on AI skills

Despite the commonly used narrative of an unmet demand for AI skills in Germany, notably from employers (Lane, Williams and Broecke, 2023[2]), surprisingly little attention is paid to the issue in national skills assessment and anticipation exercises. There is a lack of robust national data on the demand for AI skills from public sources.

The two most prominent national assessment and anticipation exercises for skilled labour are the Skilled Labour Monitor (Fachkräftemonitoring), commissioned by the BMAS (IAB/BIBB/GWS, 2023[10]), and the Bottleneck Analysis (Engpassanalyse) from the Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) (Bundesagentur für Arbeit, 2023[11]). The Skilled Labour Monitor provides an annual medium- and bi-annual long-term overview of the likely development of labour supply and demand in Germany. It is conducted under the joint direction of the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung, BIBB) and the Institute for Employment Research (Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, IAB) and in co-operation with the Institute for Economic Structure Research (Gesellschaft für Wirtschaftliche Strukturforschung, GWS). The Bottleneck Analysis uses a set of standardised indicators to identify occupations or occupational groups where there are shortages and is carried out annually by the Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit). There are several other sectoral or regional skills forecasting exercises (OECD, 2016[12]; 2021[3]).

None of the existing exercises provide a comprehensive picture of the demand for AI skills in Germany. According to interviewees, there are several factors that explain this shortcoming, including a strong focus on forecasting occupational rather than skill demand, methodological difficulties in defining AI skills, and scepticism towards new data sources such as online job vacancy data for skill forecasting exercises. There is also a widely held view amongst interviewed experts that specialised AI skills are still only required by a small share of jobs in the labour market.

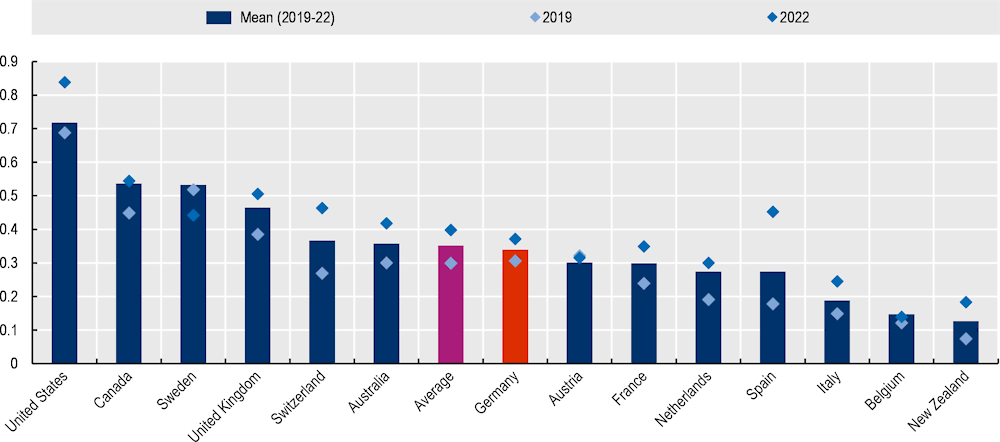

International evidence suggests that demand for AI skills is low but growing

International evidence from a new OECD study confirms this view, showing that specialised AI-related vacancies still account for only a small proportion of all job vacancies advertised online (Figure 5.2). In Germany, less than 0.4% of advertised vacancies explicitly required AI skills in 2022. This is slightly below the average of countries for which data are available and half that of the US, where 0.8% of advertised vacancies required such skills. However, demand for AI skills in Germany is growing rapidly and has increased more than 20% between 2019 and 2020 (Borgonovi et al., 2023[13]; Green and Lamby, 2023[1]).

The analysis also shows that the demand for AI-related jobs is highly concentrated in specific industries and occupations. Interestingly, Germany has the highest share of vacancies requiring AI skills that are in the manufacturing sector of the countries analysed (Borgonovi et al., 2023[13]).

Figure 5.2. Jobs requiring AI skills account for a small proportion of all advertised jobs

Percentage of online vacancies advertising positions requiring AI skills, by country

Notes: The figure shows the percentage of online vacancies advertising positions requiring AI skills by country. This corresponds to the total number of online vacancies requiring AI skills relative to all vacancies advertised in a country. Vacancies requiring AI skills are vacancies in which at least two generic AI skills or at least one AI-specific skill were required (see Borgonovi et al. (2023[13]) on generic and specific skills). Countries are sorted in descending order by the highest average share across 2019 to 2022 of vacancies requiring AI skills. Average refers to the average across countries with available data.

Source: Borgonovi, F. et al. (2023[13]), “Emerging trends in AI skill demand across 14 OECD countries”, https://doi.org/10.1787/7c691b9a-en.

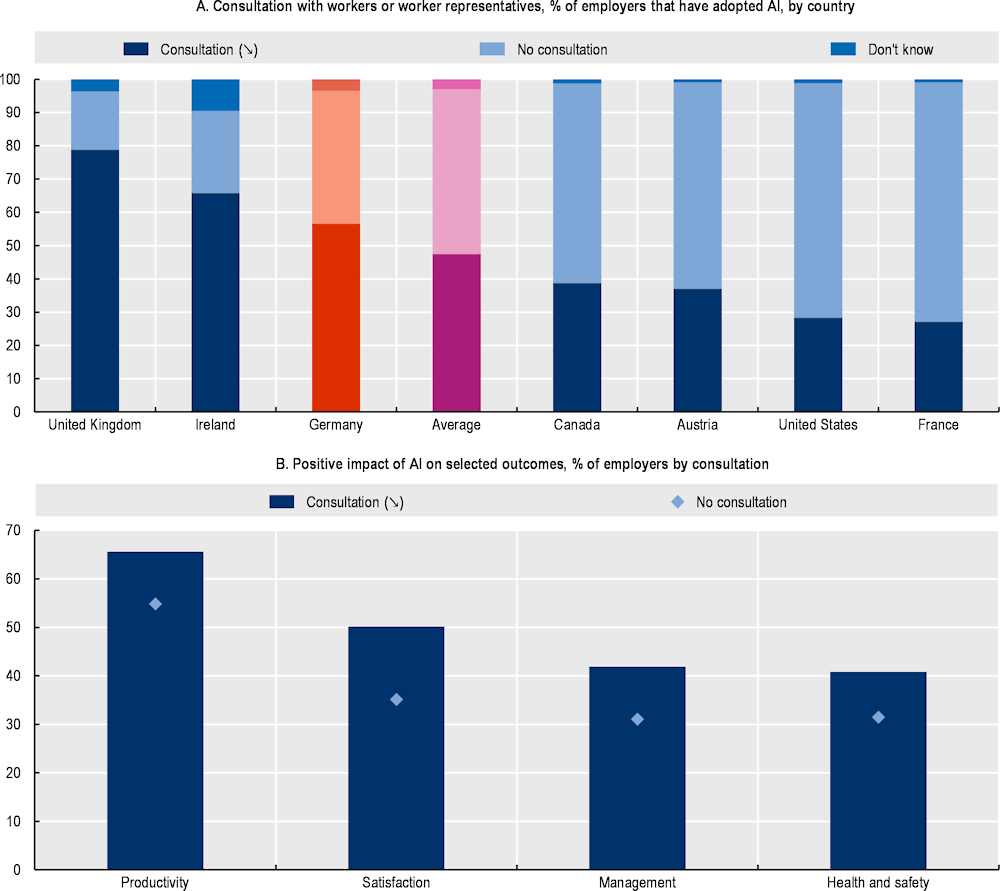

Social dialogue

Social dialogue is vital in navigating AI transitions. In the workplace, recent evidence points for example to the beneficial role of workers consultation for working conditions and performance. Yet, social partners face expertise and resource limitation. As seen in Germany’s Works Council Modernization Act, training and expert consulting are instrumental for informed decision making on AI in workplaces.

Collective bargaining and social dialogue have an important role to play in supporting workers and businesses in the AI transition. Recent OECD work points notably to the beneficial role of workers’ voice for working conditions and performance (Figure 5.3). Across OECD countries, both unions and employers’ organisations have launched national and international initiatives. Social partners engage in outreach and awareness campaigns highlighting the need for new competencies and training requirements, as well as areas of concern such as the trustworthy use of AI (OECD, 2023[14]). Yet, social partners’ activities are often limited by their lack of AI-related expertise and capacities and resources to attain it. In that context, it is crucial to offer them training opportunities or provide expertise on AI at the workplace or firm level.

One way to secure such expertise beyond the training of social partners themselves is the recruitment or consultation of technical experts. This could not only ensure better technical understanding within unions and employers’ organisations, but also ensure the recognition of workers’ interests in the workplaces where technology is developed. In turn, this could contribute to more trustworthy technology. One example in this respect is the German Works Council Modernization Act passed in 2021, which facilitates exercising the right to consult an external expert in cases where the Work Council has to assess the introduction or use of AI.1

Figure 5.3. Employers who consult workers or workers representatives are more likely to report positive impacts of AI on worker productivity and working conditions, 2022

Notes: In Panel A, employers were asked: “Does your company consult workers or worker representatives regarding the use of new technologies in the workplace?”. In Panel B, employers that have adopted AI were “Has artificial intelligence had a positive effect, negative effect or had no effect on worker productivity/worker satisfaction/managers’ ability to measure worker performance/health and safety in your company?”. Figures in Panel B show the proportions of employers that reported a positive effect. Average is the unweighted average of countries shown in Panel A.

Source: Lane, M., M. Williams and S. Broecke (2023[2]), “The impact of AI on the workplace: Main findings from the OECD AI surveys of employers and workers”, https://doi.org/10.1787/ea0a0fe1-en.

Interviews conducted with trade unions and employer representatives2 confirm that limitations due to insufficient AI-related knowledge and resource constraints are among the main challenges they face regarding AI adoption in the workplace. They refer to AI as a “black box” and point to the diverse and complex range of AI topics that require technical expertise to understand AI potential. Time and resource constraints are also reported as a concrete challenge, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Other important challenges outlined by the unions include the lack of a common definition (hence understanding) for AI between employers and employee representatives and of transparency from employers and AI providers regarding the use and goals of AI in the company. Finally, they also highlight insufficient experience and routines to cover AI in co-determination.3

Despite these challenges, several initiatives and projects have been launched by social partners to offer consulting or training services (websites, guides, trade unions’ educational institutions, etc.), and by the government, such as the future centres and regional competences centres set up by the BMAS and the Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF). However, social partners point to the lack of co-ordination between the various initiatives. This multiplicity of training programmes may be confusing, notably for employer representatives trying to provide the best match for companies while monitoring effectiveness.

Finally, views about the introduction of the German Work Council Modernization Act are mixed even if generally seen as positive. Workers’ representatives (unions) consider it as insufficient because it only applies to firms with a work council in place4 and falls short of what is needed in terms of co-determination when it comes to AI and algorithmic systems. Trade unions consider that there needs to be enforceable co-determination for framework process agreements that cover all process stages of the operational use of AI and algorithmic systems (before introduction through to evaluation).5 In addition, they hint to the potential source of conflict it may create when implementing the Act since employer and work councils first need to agree whether AI is really at stake and whether the involvement of an external expert is required, as employers support as much as possible the use of in-house expertise because it is less costly and less time consuming.6

Recommendations

Strengthen information collection on the supply and demand of AI skills

While the well-established narrative of a significant AI skills shortage in Germany might be true, there is no robust and granular national evidence on the supply and demand of AI skills in the labour market. To design employment policies that facilitate the successful and responsible adoption of AI, skills assessment and anticipation exercises urgently need improvement. Given the relatively small size of the labour market for specialised AI skills, this should be done as an ad hoc study. For example, the Skilled Labour Monitor could include this analysis as a focus in one of its editions.

Alternatively, the BMAS could commission a separate study as a research report. Any national analysis of supply and demand regarding AI skills should draw on international examples to define AI skills and assess demand, including from the OECD (Borgonovi et al., 2023[13]; Green and Lamby, 2023[1]). However, such an assessment and anticipation exercise should focus on the national context and occupations rather than skills in labour market. Given the dynamic nature of the AI skills market, any exercise should be repeated after a maximum of years, ideally. In all cases, strengthening skills assessment and anticipations will require close collaboration with industry stakeholders to identify emerging trends and gaps.

Promote education and training opportunities through PES and career guidance

The PES’ role in guiding career choices and providing information on job prospects is crucial. Indeed, the German PES have recently extended their offer of career guidance to working people through the Lifelong Vocational Guidance programme (Bundesagentur für Arbeit, 2023[15]). Despite the mandate for neutral guidance, there's an opportunity to highlight the emerging opportunities within AI-related occupations strategically. By disseminating information on AI career prospects and offering clear pathways for skills development and career progression, PES can actively contribute to steering individuals towards AI-related opportunities. The recent move to provide PES guidance counsellors with teaching and learning materials on future digital skills, AI and cybersecurity is a positive development in this regard. Working closely with industry stakeholders and drawing on a strong evidence base of skills demand is critical to ensuring that guidance aligns with current and anticipated AI labour market needs. Good practices in steering training choices through guidance and financial incentives can be found in Australia and Estonia, and elsewhere (OECD, 2017[9]).

However, data from the German Adult Education Survey show that the PES accounts for only around a third of all career guidance for adults in Germany (BMBF, 2019[16]), with 26% of individuals receiving guidance from educational institutions, 21% from further education providers, 18% from employers and employer organisations, and 16% from specialised guidance providers. Given the decentralised nature of career guidance provision in Germany, information on opportunities in AI-related occupations must be centralised for public use. This could happen on the newly developed national online portal for continuing education and training (My NOW, mein NOW). Denmark's UddannelsenGuiden (www.ug.dk) and New Zealand's Occupation Outlook app are among the many good examples of high-quality online portals for education and training opportunities (OECD, 2021[17]).

Increase flexibility and modularity in adult learning, especially in VET

AI technologies require a paradigm shift in adult education, particularly VET, which too often expect adults to take long courses leading to full qualifications, rather than participating in shorter, more targeted, and modular learning opportunities that are more reactive to technological developments (OECD, 2021[3]). VET courses must become diverse and modular to ensure accessibility and reflect the dynamic nature of AI-related skills. However, German education and training stakeholders often perceive modularity with scepticism (OECD, 2021[3]). To address this, Germany should make greater use of elective qualifications (Wahlqualifikationen), which are shorter, modular elements of full vocational qualifications. Introducing AI content into VET qualifications through these instruments allows them to adapt more frequently to new requirements and opens the door for individuals to take up this modular offer as part of their upskilling or reskilling pathway.

Incentivise employers to provide AI-related training

Most adult learning takes place in the workplace. However, German employers provide limited training in AI compared to other countries (Lane, Williams and Broecke, 2023[2]). Recognising the central role of employers in shaping a skilled AI workforce, policies to incentivise and support AI-related training initiatives should be strengthened. Looking at good practices, Estonia has extensive experience in supporting enterprises with digital skill development (OECD, 2021[18]).

This would primarily address obstacles to training faced by SMEs. Promising initiatives that develop employers’ capacity to provide training to adapt to technological opportunities include Hubs for Tomorrow (Zukunftszentren) and Continuing Education and Training Associations (Weiterbildungsverbünde). These should be evaluated and strengthened as needed. Germany also supports in-company training through the Qualification Opportunities Act (Qualifizierungschancengesetz) and the Work of Tomorrow Act (Arbeit-von-Morgen-Gesetz). The BMAS could explore whether specific incentives for training in introducing AI could be provided through this instrument or if a specific financial incentive programme for AI would be more effective.

Encourage consultations and co-operation with social partners on AI introduction

Considering the positive role of social dialogue in the workplace, the government should encourage consultations and discussions on AI introduction with social partners, work council members, and employees. Policy makers should also support mutual understanding and shared diagnosis of challenges and use knowledge platforms and co-operation to share practices on new initiatives and technological innovation among actors. Getting involved early and regularly in AI-related issues brought up by employee and co-determination bodies could enhance trust and acceptance for introducing AI into the workplace.

Foster AI-related knowledge in the workplace and facilitate access to expertise

The government should add financial incentives for building AI competences – notably reaching out to SMEs – and join forces with social partners to promote AI-related expertise to management, work council members, and supervisory board members. Considering the variety of existing AI-related training initiatives, the government should encourage more transparent and systematic networking between actors and programmes. Finally, the government could facilitate access to external expertise by simplifying the implementation process.

References

[5] BIBB (2020), Fachinformatiker/Fachinformatikerin - Fachrichtung Daten- und Prozessanalyse (Ausbildung), Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung, https://www.bibb.de/dienst/berufesuche/de/index_berufesuche.php/profile/apprenticeship/ujhz677 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[8] BMAS (2023), Das Bundesprogramm“Aufbau von Weiterbildungsverbünden”, Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, https://www.bmas.de/DE/Arbeit/Aus-und-Weiterbildung/Berufliche-Weiterbildung/Weiterbildungsverbuende/weiterbildungsverbuende.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[7] BMAS (2022), ESF Plus-Programm “Zukunftszentren”, Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, https://www.bmas.de/DE/Arbeit/Digitalisierung-der-Arbeitswelt/Austausch-mit-der-betrieblichen-Praxis/Zukunftszentren/zukunftszentren.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[4] BMAS et al. (2019), Nationale Weiterbildungsstrategie, https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Aus-Weiterbildung/strategiepapier-nationale-weiterbildungsstrategie.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 30 July 2020).

[16] BMBF (2019), Weiterbildungsverhalten in Deutschland 2018. Ergebnisse des Adult Education Survey-AES-Trendbericht, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, https://www.bmbf.de/SharedDocs/Publikationen/de/bmbf/1/31516_AES-Trendbericht_2018.html (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[13] Borgonovi, F. et al. (2023), “Emerging trends in AI skill demand across 14 OECD countries”, OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers, No. 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7c691b9a-en.

[15] Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2023), Die Lebensbegleitende Berufsberatung der BA, Bundesagentur für Arbeit, https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/datei/die-lebensbegleitende-berufsberatung-der-ba_ba035445.pdf.

[11] Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2023), Engpassanalyse, Bundesagentur für Arbeit, Nürnberg, https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/DE/Navigation/Statistiken/Interaktive-Statistiken/Fachkraeftebedarf/Engpassanalyse-Nav.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

[1] Green, A. and L. Lamby (2023), “The supply, demand and characteristics of the AI workforce across OECD countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 287, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bb17314a-en.

[10] IAB/BIBB/GWS (2023), Fachkräftemonitoring fuer das BMAS. Mittelfristprognose bis 2027, Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung and Gesellschaft für Wirtschaftliche Strukturforschung mbH, https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Publikationen/Forschungsberichte/fb-625-fachkraeftemonitoring-bmas-mittelfristprognose-2027.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3.

[2] Lane, M., M. Williams and S. Broecke (2023), “The impact of AI on the workplace: Main findings from the OECD AI surveys of employers and workers”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 288, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ea0a0fe1-en.

[14] OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2023 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a5f73ce-en.

[17] OECD (2021), Career Guidance for Adults in a Changing World of Work, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9a94bfad-en.

[3] OECD (2021), Continuing Education and Training in Germany, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1f552468-en.

[18] OECD (2021), Training in Enterprises: New Evidence from 100 Case Studies, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7d63d210-en.

[9] OECD (2017), Financial Incentives for Steering Education and Training, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272415-en.

[12] OECD (2016), Getting Skills Right: Assessing and Anticipating Changing Skill Needs, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252073-en.

[6] Vössing, M. (2023), “So kommt Künstliche Intelligenz in die berufliche Bildung”, https://www.ihk.de/ulm/online-magazin/im-fokus/fachartikel-ki-berufliche-bildung-5692358 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

Notes

← 1. Similarly, the agreement between the General Staff council of the city of Stuttgart and the city as a public employer stipulates that the staff council may use external consulting services at the city’s expense.

← 2. Both trade unions and employers’ representatives who were interviewed highlighted the critical role of work councils and co-determination actors in that area. Unfortunately, we could not manage to reach out work councils directly.

← 3. A potential additional obstacle may arise when the main project managers for AI implementation are abroad (e.g. in the US) and lack complete knowledge about German codetermination functioning and needs.

← 4. The workforce in companies with five or more employees can elect a works council on a voluntary basis. Works councils can only be established by an election of the workforce, so companies can operate without a works council until the workforce elected one. Consequently, the number of companies that have a works council is limited.

← 5. This point was emphasised by the Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (DGB) (German Trade Union Confederation) during the interview conducted for this study.

← 6. Therefore, the importance of having a common definition of AI mentioned before. This problem led to the DGB’s demand that the work council alone decide on the involvement of external expertise, regardless of the topic, i.e. even if is not about AI.