Research serves as the foundation for advancements in artificial intelligence (AI). This chapter explores Germany's position in the global landscape of AI research. With its national AI strategy emphasising the importance of reinforcing and expanding its research excellence in AI, Germany aims to remain at pace with rapid international progress. Germany ranks highly worldwide, excelling in robotics, automation, and in AI research in energy and manufacturing. German research institutions like the Max Planck Society and Siemens rank among the top globally, and a network of six AI excellence centres aim to enhance Germany's standing in AI technologies. While funding for AI research is available from various sources, mechanisms could be made more agile to align with the rapidly evolving technology landscape. The German AI research community is characterised by a strong gender disparity, underscoring the need for Germany to strengthen efforts to increase women’s representation in AI.

OECD Artificial Intelligence Review of Germany

3. Research

Abstract

Research underpins progress in AI. Both the 2018 German national AI strategy and its 2020 update emphasise the need for Germany to reinforce and expand its research excellence in AI to keep up with rapid international developments (German Federal Government, 2020[1]). Accordingly, the national AI strategy foresees several measures in this regard.

Box 3.1. Research: Findings and recommendations

Findings

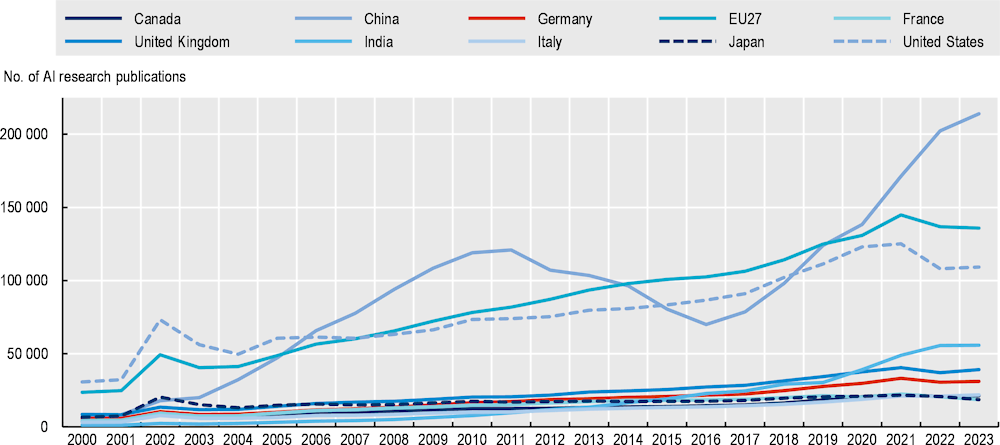

Germany is well-positioned in research internationally, ranking fifth worldwide in number and quality of publications. However, countries such as India have quickly climbed the ranking in recent years, albeit not in terms of quality.

Public and private German institutions both rank in top positions for the quality of their AI research (the Max Planck Society and Siemens).

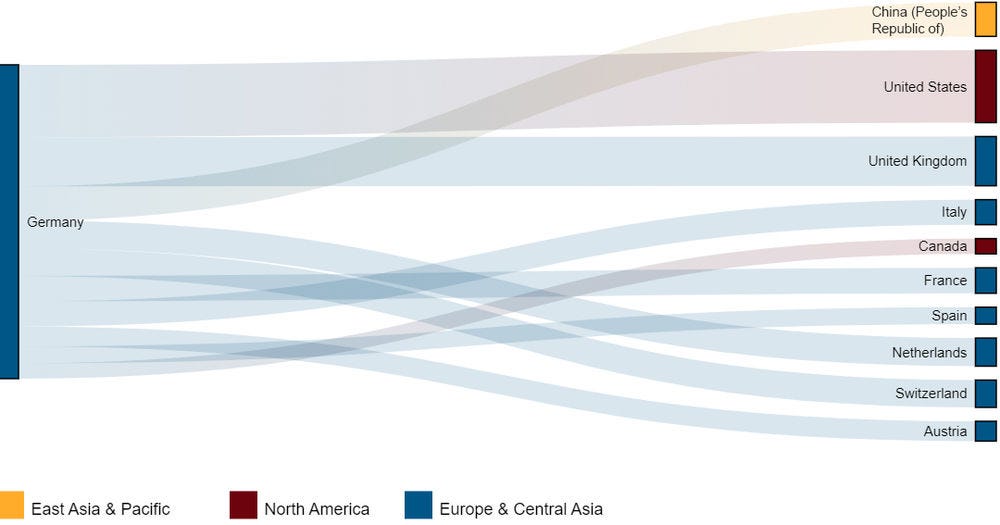

German institutions participate in many European Union (EU)-funded AI projects. However, German institutions collaborate more with institutions from the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) than European ones.

In AI research topics, Germany ranks third in robotics and automation, fourth in computer vision and natural language processing, and fifth in artificial neural networks worldwide.

Germany’s funding system is uniquely positioned, as applicants can apply for joint funding programmes, EU funding, and federal and Länder funding. However, this diversity of funding often causes uncertainty in practice, and funding requirements are reported to be bureaucratic and cumbersome for applicants.

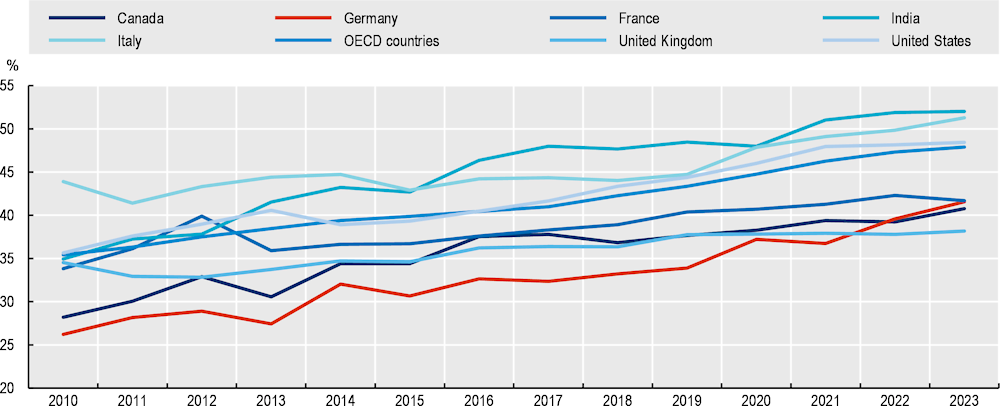

Even though the gender gap in AI research has decreased in recent years, it is still larger than in peer countries. Several federal ministries and universities have launched initiatives to counteract this trend.

Recommendations

Implement agile funding mechanisms that can adapt to the rapidly changing landscape of AI research.

Double down on efforts to increase the involvement of women and under-represented communities in AI research and development (R&D) and collaborate between ministries to address structural issues underlying unequal opportunities for the participation of women in the labour market.

AI publications

German institutions reported a notable increase in AI research publications since 2018, ranking fifth globally in number and fourth in quality, with strengths in computer vision and robotics.

In Germany’s national AI ecosystem, its solid research base is a strength

German institutions published about 31 105 AI publications in 2023, representing a 26% increase since 2018. Germany ranks fifth internationally (Figure 3.1) in number of AI publications, following the US, China, the UK and India. It is fourth when considering publication quality, as measured by the number of times a publication has been cited. Public and private German institutions rank in top positions for the quality of their AI research: the Max Planck Society ranks second worldwide alongside the University of California Berkeley, while Siemens ranks seventh among leading global companies producing AI research (OECD.AI, 2023[2]).

Figure 3.1. Germany ranks fifth worldwide in number of AI publications

Note: More than 600 000 AI scholarly publications were extracted from Elsevier’s Scopus archives using core AI keywords such as back-propagation neural network, genetics-based machine learning, Cohen-Grossberg neural networks, back-propagation algorithm, and neural networks learning. Chapter 1 of Elsevier’s “Artificial Intelligence: How knowledge is created, transferred, and used” report provides more details on the methodology used to identify AI publications.

Source: OECD.AI (2023[3]),AI Research Publications Time Series by Country, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualisation=ai-publications-time-series-by-country (accessed on 12 October 2023).

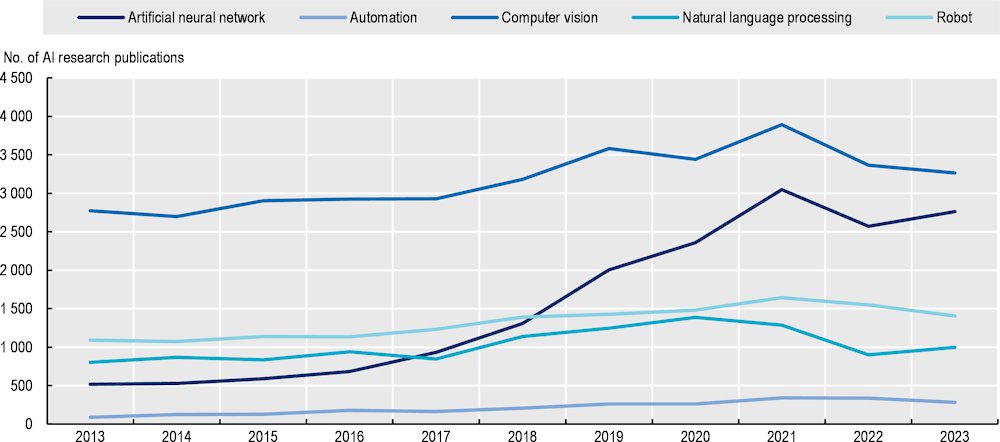

In line with current research trends in other countries, German institutions publish the most on computer vision, a field of AI enabling computers to interpret and understand the visual world from images, videos, and other inputs (Figure 3.2). Computer vision applications can be used in many domains, including automotive, medicine, and manufacturing (e.g. quality anomaly detection). In this field, the country ranks fourth worldwide for the quality of publications (calculated in terms of citations).1 Germany also has a competitive advantage in robotics and automation, ranking third worldwide in these fields of research (calculated in terms of citations). Germany also ranks fourth in natural language processing. Since 2016, AI publications in Artificial Neural Networks, the machine learning sub-domain which has enabled the rapid advancements of AI, including in generative AI, have dramatically increased, and Germany currently ranks fifth worldwide in this domain for the quality of its AI publications (OECD.AI, 2023[4]).

There are two more areas of AI specialisation where Germany and Europe are leading research. In energy, where they explore AI uses to improve the efficiency and reliability of generating and distributing energy. They also have an edge in manufacturing research, to optimise and automate production, inventory, and predictive maintenance (OECD.AI, 2023[5]). It is crucial for Germany to remain competitive in the future AI‑heavy transportation industry, and in manufacturing, for example by further leveraging the use of AI in robotics.

While Germany compares well in AI research worldwide, the size of the leading global competitors – China, India and the US, which is growing rapidly – makes it essential for Germany to leverage co-operation with EU27 countries. Effectively, Germany is the country with the highest participation in AI‑related projects funded by the EU research programmes, both in number of projects and in terms of funding. In 2023, German institutions were involved in over 290 projects, for a total funding of about EUR 310 million (OECD calculation based on Community Research and Development Information Service data). But Germany collaborates more with the US and the UK than with individual EU countries (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.2. German institutions publish in all key AI topics

Source: OECD.AI (2023[4]), Trends in AI Application Areas by Country, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualisation=trends-in-ai-application-areas-by-country (accessed on 12 October 2023).

Figure 3.3. German institutions mainly collaborate with partners in the United States and the United Kingdom

Source: OECD.AI (2023[6]), Domestic and International Collaboration in AI Research Publications, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualisation=domestic-and-international-collaboration-in-ai-publications (accessed on 5 November 2023).

To support research collaboration nationally, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF) helped to create the Network of German Centres of Excellence for AI Research (Netzwerk der Deutschen Kompetenzzentren für Forschung zu Künstlicher Intelligenz), six leading AI research institutions funded by federal and state budgets: i) Berlin Institute for the Foundations of Learning and Data (BIFOLD); ii) German Research Centre for Artificial Intelligence (Deutsches Forschungszentrum für Künstliche Intelligenz, DFKI); iii) Munich Centre for Machine Learning (MCML); iv) Lamarr Institute for Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence North Rhine-Westphalia (LAMARR); v) Centre for Scalable Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence Dresden/Leipzig (ScaDS.AI); and vi) Tübingen AI Centre (TUE.AI). While the objective is for these institutions work together to strengthen Germany as a top location for AI technologies and increase German AI research's national and international visibility (DFKI, 2023[7]), stakeholders say it has yet to act as a network. While the BMBF actively promotes stronger collaboration in the German AI research community, e.g. via the All-Hands-Meeting of the competence centres and the “AI Grid”, there could be considerations to introduce incentives to deepen co-operation, for instance through funding for joint projects.

Funding for AI research in Germany comes from different sources. These include European (e.g. Horizon Europe), federal and state programmes, as well as joint programmes between universities and industry. The BMBF funds AI research, development, and application work of 50 ongoing measures that focus on research, skills development, infrastructure development and transfer to application. As part of the BMBF AI Action Plan published in November 2023, these are supplemented by at least 20 further initiatives. Moreover, BMBF’s AI budget has increased annually since 2017, most significantly between 2021, 2022, and 2023 (Table 3.1).

On its Federal Funding Advisory Service (Förderberatung des Bundes) website (Förderberatung des Bundes, 2024[8]), the federal government provides an overview of funding opportunities for applicants by consolidating access to initiatives on a centralised platform, including personalised advice. However, many interviewed experts were unaware of its availability and expressed a need for a specific centralised database. Promotion efforts are needed to reach a broader audience of potential users. Given the pace of AI development, researchers need to receive financial support more rapidly and with minimal bureaucracy. The research community (Humboldt Foundation, 2023[9]) suggests relying on the EU’s evaluation process for projects, which can be considered a “seal of excellence”. Proposals for projects evaluated above threshold by the EU panels but not funded for budgetary reasons could be considered for financial support from national sources, provided German institutions implement them.

Table 3.1. Funding for AI research in Germany

|

Year |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 (planned) |

2024 (planned) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EUR million |

17.4 |

20.5 |

41.9 |

85.7 |

120.2 |

280.4 |

427.2 |

483.3 |

Source: Based on BMBF (2023[10]), BMBF‑Aktionsplan “Künstliche Intelligenz”, https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/de/forschung/digitale-wirtschaft-und-gesellschaft/kuenstliche-intelligenz/ki-aktionsplan.html (accessed on 30 November 2023).

Gender representation in AI research

Despite some progress, women remain underrepresented in German AI research and AI leadership positions. Enhancing diversity in AI development through increased female participation can lead to fairer and more ethical outcomes of AI systems.

Women are under-represented in AI research

The increasing deployment of AI systems has raised the importance of ensuring fairness, lack of bias and non-discrimination of AI systems. An overrepresentation of male AI developers can lead to gender bias in AI through biased training data, subjective design choices overlooking considerations important to underrepresented groups, the introduction of unintentional biases and stereotypes, and a lack of diverse perspectives in addressing user needs. This imbalance may result in AI systems that perpetuate societal stereotypes and inadequately cater to the preferences and requirements of diverse user groups, including women (Leavy, 2018[11]; Nadeem, Abedin and Marjanovic, 2020[12]).

Increasing women and minorities representation in the design of AI systems can enhance AI systems by providing diverse perspectives and experiences during development, leading to more comprehensive and inclusive outcomes. Female developers, who might be more attuned to biases affecting women, play a crucial role in identifying and effectively addressing these biases. Diverse teams contribute to balanced decision making, fostering fair, ethical, and user-aligned AI systems. This inclusivity results in AI applications that better understand and cater to the diverse needs of users, ultimately improving user experience and satisfaction across various demographic groups (Gallego et al., 2019[13]).

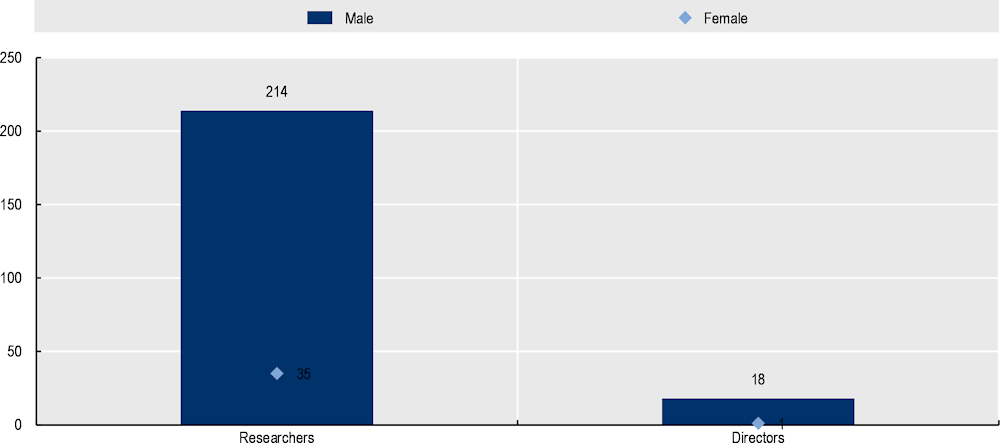

Gender and other divides in the AI research ecosystem limit inclusion of women in AI development and reduce the number of skilled AI workers available in the country. In Germany, the gender gap in AI research has been narrowing in recent years: in 2023, 41% of AI publications had at least one female author, compared to 33% in 2018 (Figure 3.4). However, only 7% of publications were authored by women exclusively in 2023 (slightly up from 5% in 2018), while 58% were written by men only (significantly down from 67% in 2018). The gender gap in AI research remains broader than in peer countries (such as France and the US). The gap is also present in leadership positions: as of January 2023, none of the six German Centres of Excellence for AI Research is led by a woman, and only 14% of the researchers or principal investigators in these centres were women (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.4. The gender gap in AI research is broader in Germany than in peer countries

Share of AI publications authored by at least one woman

Notes: This chart shows the percentage of AI publications in Scopus with at least one female author by country and over time. For this experimental indicator, Elsevier assigned a gender value only to those authors in the Scopus dataset for whom the algorithm used returned a gender probability of 85% or higher. Due to a lag in reporting, figures for the latest quarter may appear slightly lower than they actually are. This is automatically corrected in subsequent updates.

Source: OECD.AI (2023[14]), Share of Women in AI Scientific Publications by Country, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualisation=share-of-women-in-scientific-publications-by-country-2 (accessed on 5 November 2023).

Differences in men's and women’s careers start early, when making choices about education (OECD, 2017[15]). For example, on average only 0.5% of 15-year-old girls across OECD countries aim to become information and communication technology (ICT) professionals, compared to 5% of boys. This difference in career expectations is carried into tertiary education. Across OECD countries, young men dominate ICT studies, constituting 79% of new entrants on average. In 2021, the proportion of women among first-year students in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) field and in Germany reached 34.5%. This is a record high but still shows women opt for STEM studies less frequently than men, and among different STEM fields there are significant variations. For instance, in computer science, the percentage of female first-year students in 2021 was only 21.8% (OECD, 2023[16]).

Figure 3.5. Representation of women in the German AI Excellence Centres is low

Number of women researchers/principal investigators and directors of German Centres of Excellence for AI Research, 2022

Source: Analysis based on information from the six German Centres of Excellence for AI Research’s websites (https://www.dfki.de/web; https://www.bifold.berlin/; https://mcml.ai/; https://lamarr-institute.org/; https://scads.ai/; https://tuebingen.ai/).

Federal programmes in place to put more women in tech

Recently, the German Federal Government launched several initiatives to close the gender gap in AI research and in technology. They include leveraging interactions with young women to assist them in making career choices, targeted support at universities, and programmes funding women-led AI research teams.

“MissionMINT” aims to put more women in STEM (MINT) by supporting and inspiring young women transitioning from school to university and from university to the job market. Through joint projects, role models, network activities and workshops, the programme exposes women to opportunities in the STEM sector to break down prejudices and create opportunities to experiment (BMBF, 2023[17]). Influencing career choices through representatives from the AI field is certainly one of the key policy levers to increase the number of women in AI. While the programme goes in the right direction, it should be expanded to include a focus area on AI.

The number of women in AI and science declines as careers advance. Barriers, such as cultural norms (i.e. gender-assigned roles), implicit biases, and the unique impact of parenthood on women’s careers, are more likely to reduce participation in science at higher levels than a lack of talented women at the early career stage (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2023[18]; EC, 2021[19]; Stadler et al., 2023[20]).

Since 2020, the BMBF has supported female-led junior research groups in AI through its funding measure “Female AI junior scientists" (KI-Nachwuchswissenschaftlerinnen). The programme aims to increase the proportion of qualified women in leadership positions in German AI research, and to strengthen the influence of female scientists sustainably. While the focus is placed on AI research on novel and innovative topics, family-work balance conditions at the applicants’ respective universities are also considered as an allocation criterion. In 2023, the BMBF published a new call for junior female AI scientists.

The Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth’s (Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, BMFSFJ) “Third Equality Report” focused on digital gender equality (BMFSFJ, 2021[21]). The report highlighted potential for gender-based discrimination in AI, such as biased human resources tools, and provided recommendations for ways the federal government can address these issues. Examples include promoting gender-sensitive and inclusive technology development and risk assessments of algorithmic human resource systems.

German computer science departments have targeted support for women. Nearly all of the 20 largest German universities have networks, coding initiatives, mentoring programmes, project funding or equal opportunity councils for women in computer science (Informatik). Most of these measures are not AI‑specific; only two universities have targeted programmes for women in AI.

Beyond these programmes, it is essential to acknowledge the more extensive, systemic issues affecting the number of women in AI R&D, STEM, and the workplace in general. Existing income taxation rules for couples reduce labour supply incentives, particularly for women (OECD, 2023[22]). Cultural factors still place childcare responsibilities in predominantly on women. In places where external childcare facilities are limited, women are likely to be more affected than men, and to be required to make corresponding adjustments to their employment. For instance, in Tübingen, where the CyberValley is located, the operating hours of kindergartens have recently been reduced (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 2023[23]). This indicates the need to look at broader issues when devising policies related to AI, such as the distribution of domestic labour and care responsibilities between men and women.

In the future, Germany should double down on efforts to increase women in AI through larger programmes that focus on AI. Germany should continue encouraging education initiatives targeted at young women to raise awareness about roles and paths in the AI field, recognising that a degree in computer science is not a prerequisite. Increasing the visibility and showcasing female leaders in AI would contribute to overcoming societal stereotypes, expose them to career options and encourage girls to pursue AI careers. Early engagement through extracurricular AI programmes such as bootcamps or practical projects can foster interest, confidence, and competence. To support women who chose careers in AI, it is crucial to develop mentorship programmes and ensure equal workplace opportunities, including through better work-life balance support.

Recommendations

Implement agile funding mechanisms that can adapt to the rapidly changing landscape of AI research

Funding programmes for AI research are highly decentralised and often rely on a lengthy process to select projects for awarding grants. Given the pace of AI developments, researchers need to receive financial support fast and with minimal bureaucracy. German programmes could rely on the EU’s project evaluation process, which can be considered a “seal of excellence”. Projects rated above threshold but not funded for budgetary reasons could be considered for financial support from national sources, provided they are implemented by German institutions.

Double down on programmes aimed at involving women in AI R&D, and collaborate between ministries to address structural issues of unequal opportunities for women’s participation in the labour market

Increasing the number of women in AI development is necessary to reduce the risks of bias and discrimination in AI algorithms. To increase the AI-skilled labour force there needs to be more women. While the gender gap in AI research in Germany has narrowed in recent years, women are still under-represented in the AI ecosystem, including in leadership positions. Current efforts to increase women’s participation in AI go in the right direction and should continue and be expanded. At the same time, inter‑ministerial efforts should address broader structural factors that reduce women’s participation in the labour market such as the availability of childcare facilities.

References

[10] BMBF (2023), BMBF-Aktionsplan “Künstliche Intelligenz”, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/de/forschung/digitale-wirtschaft-und-gesellschaft/kuenstliche-intelligenz/ki-aktionsplan.html (accessed on 30 November 2023).

[17] BMBF (2023), “MissionMINT – Wir stärken die Innovationskraft von Frauen im akademischen MINT-Bereich”, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/de/forschung/gleichstellung-und-vielfalt-im-wissenschaftssystem/mint-pakt/mint-pakt_node.html#:~:text=F%C3%B6rderrichtlinie%20%E2%80%9EMissionMINT%20%E2%80%93%20Frauen%20gestalten%20Zukunft%E2%80%9C&text=In%20den%20sensiblen%20Pha (accessed on 11 October 2023).

[21] BMFSFJ (2021), Dritter Gleichstellungsbericht - Digitalisierung geschlechtergerecht gestalten, Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/service/publikationen/dritter-gleichstellungsbericht-184546 (accessed on 11 October 2023).

[7] DFKI (2023), Netzwerk der Deutschen Kompetenzzentren für Forschung zu Künstlicher Intelligenz, Deutsches Forschungszentrum für Künstliche Intelligenz GmbH, https://www.dfki.de/web/qualifizierung-vernetzung/netzwerke-initiativen/ki-kompetenzzentren (accessed on 12 October 2023).

[19] EC (2021), She Figures 2021: Gender in Research and Innovation - Statistics and Indicators, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, European Commission, https://doi.org/10.2777/06090.

[8] Förderberatung des Bundes (2024), Förderfinder des Bundes, Federal Funding Advisory Service, https://www.foerderinfo.bund.de/SiteGlobals/Forms/foerderinfo/bekanntmachungen/Bekanntmachungen_Formular.html?cl2Categories_Foerderer=bund (accessed on 29 January 2024).

[13] Gallego, A. et al. (2019), “How AI could help - or hinder - women in the workforce”, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/artificial-intelligence-ai-help-hinder-women-workforce (accessed on 5 December 2023).

[1] German Federal Government (2020), Strategie Künstliche Intelligenz der Bundesregierung - Fortschreibung 2020, https://www.ki-strategie-deutschland.de/files/downloads/201201_Fortschreibung_KI-Strategie.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2023).

[9] Humboldt Foundation (2023), Sieben Empfehlungen zur Künstlichen Intelligenz (KI) an die Deutsche Bundesregierung, https://www.humboldt-foundation.de/fileadmin/Bewerben/Programme/Alexander-von-Humboldt-Professur/Positionspapier_zur_Kuenstlichen_Intelligenz_Recommendations_on_AI.pdf (accessed on 2023 October 2023).

[11] Leavy, S. (2018), “Gender bias in artificial intelligence: The need for diversity and gender theory in machine learning”, Conference paper, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Susan-Leavy-4/publication/326048883_Gender_bias_in_artificial_intelligence_the_need_for_diversity_and_gender_theory_in_machine_learning/links/5bce138aa6fdcc204a001d87/Gender-bias-in-artificial-intelligence-the-need-for.

[12] Nadeem, A., B. Abedin and O. Marjanovic (2020), “Gender bias in AI: A review of contributing factors and mitigating strategies”, ACIS 2020 Proceedings, https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2020/27.

[16] OECD (2023), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en.

[22] OECD (2023), OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9642a3f5-en.

[15] OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281318-en.

[2] OECD.AI (2023), AI Research Publication Time Series by Institution, OECD, Paris, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualization=ai-publication-time-series-by-institution (accessed on 12 October 2023).

[3] OECD.AI (2023), AI Research Publications Time Series by Country, OECD, Paris, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualization=ai-publications-time-series-by-country (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[6] OECD.AI (2023), Domestic and International Collaboration in AI Research Publications, OECD, Paris, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualization=domestic-and-international-collaboration-in-ai-publications (accessed on 5 November 2023).

[14] OECD.AI (2023), Share of Women in AI Scientific Publications by Country, OECD, Paris, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualisation=share-of-women-in-scientific-publications-by-country-2 (accessed on 5 December 2023).

[5] OECD.AI (2023), Top Policy Areas in AI Publications by Country, OECD, Paris, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualization=top-policy-areas-in-ai-publications-by-country (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[4] OECD.AI (2023), Trends in AI Application Areas by Country, OECD, Paris, https://oecd.ai/en/data?selectedArea=ai-research&selectedVisualisation=trends-in-ai-application-areas-by-country (accessed on 12 October 2023).

[20] Stadler, B. et al. (2023), The “PARENT” Initiative: PArents in REsearch aNd Technology, https://doi.org/10.34726/4822.

[18] Statistisches Bundesamt (2023), “6,5 % weniger Studienanfängerinnen und -anfänger in MINT-Fächern im Studienjahr 2021”, https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2023/01/PD23_N004_213.html#:~:text=Frauen%20entscheiden%20sich%20nach%20wie,2021%20bereits%2034%2C5%20%25. (accessed on 2023 November 2023).

[23] Süddeutsche Zeitung (2023), “Eltern nach Kürzungen der Kita-Öffnungszeiten besorgt”, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/leben/kindergaerten-tuebingen-eltern-nach-kuerzungen-der-kita-oeffnungszeiten-besorgt-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-230211-99-559092 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

Note

← 1. Global rankings are calculated on the basis of cumulative number of citations of AI research publications in the topic of application from 2000 to 2023, based on data from the OECD.AI Policy Observatory (OECD.AI, 2023[4]).