This peer review report assesses progress made since the 2016 peer review, highlights recent successes and challenges, and provides recommendations for the future. The report was prepared with reviewers from the Czech Republic and Japan, with support from the OECD Secretariat.

Spain, the 13th largest Development Assistance Committee (DAC) member by volume, has recently set out a comprehensive reform agenda for its development co-operation, grounded in high public support. The agenda involves reforming the legislative and regulatory framework, setting out new priorities and objectives for Spanish co-operation and increasing the official development assistance (ODA) budget.

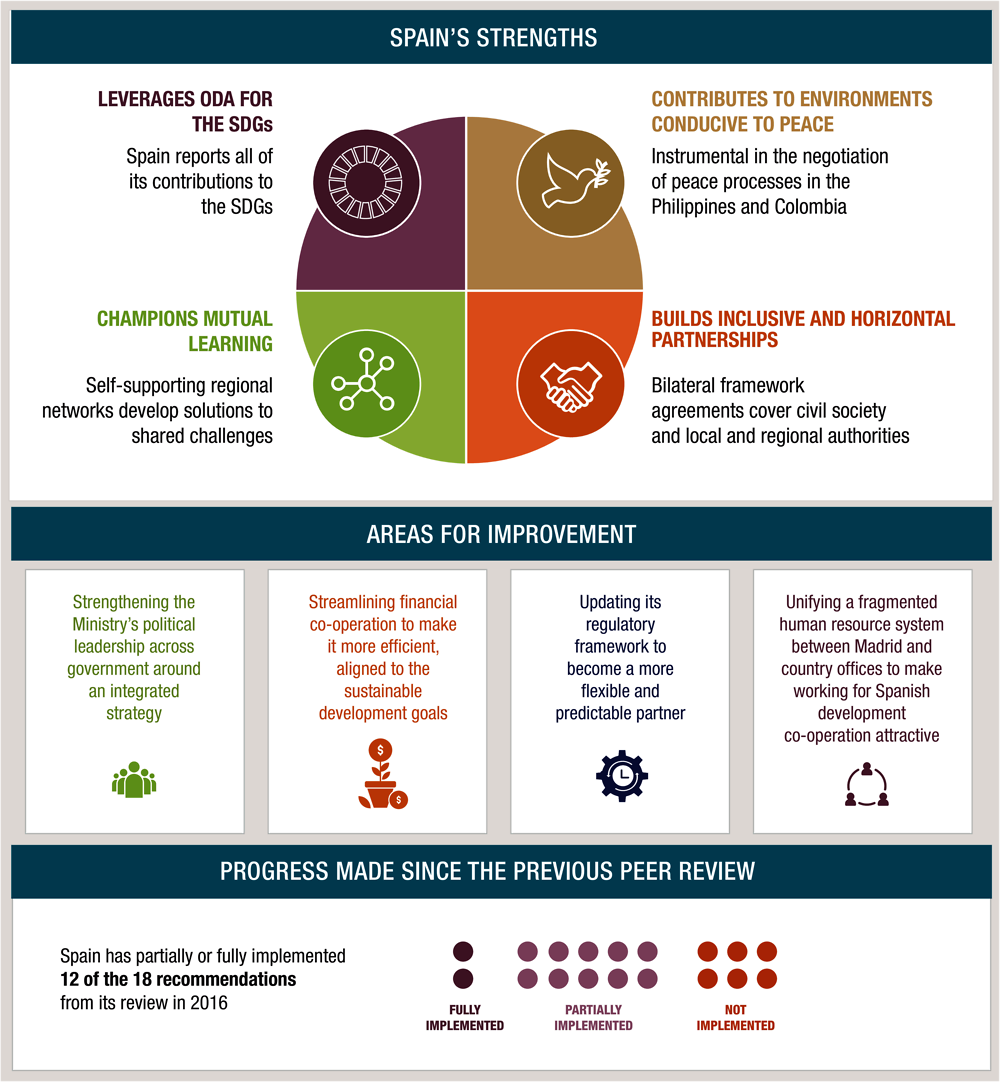

Spain is committed to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the highest level. It has made international co-operation a state policy, central to its external action, to use as a lever and catalyst to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) globally and has committed to strengthen policy coherence mechanisms. By clearly linking its bilateral co-operation frameworks (MAPs) to the SDGs, Spain also helps its partners advance the agenda locally. Spain has increased transparency and accountability surrounding its total official support for sustainable development (TOSSD) and its alignment with the SDGs when communicating to the general public and parliament.

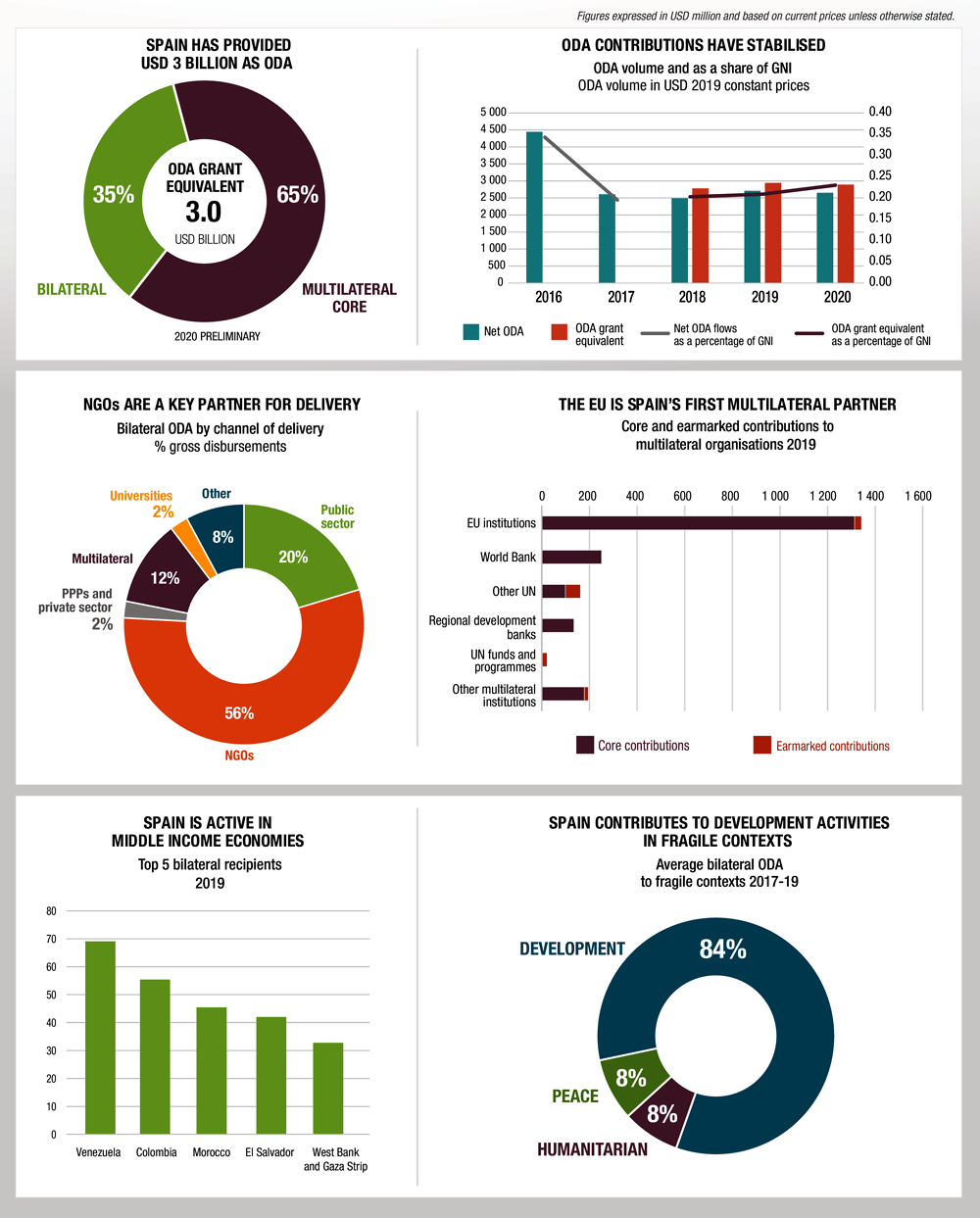

In fragile contexts, development and peace activities are strongly linked, in line with the OECD Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace nexus. Spain engages in conflict mediation and cultural co-operation to create environments conducive to sustainable peace and to facilitate conflict resolution, thus reinforcing its long-term political engagement in peace processes. NGOs are a great asset. While NGOs implement 56% of Spain’s bilateral ODA, they deliver 86% of Spain’s engagement in fragile contexts enabling it to engage at very local levels, cementing trust and participation.

Spain places particular emphasis on collaborating with institutions from the European Union (EU) and other partners. The third-largest implementer of EU delegated co-operation, Spain invests heavily in influencing EU development policy in Brussels to increase the policy focus on inclusion. EU delegated co‑operation and Spain’s bilateral investments are complementary. Spain also works with multilateral development banks and bilateral development finance institutions to blend reimbursable and non‑reimbursable financing and extend the range of instruments it has at its disposal.

Spain champions horizontal partnerships and mutual learning. By leveraging technical expertise from the public sector, Spain has contributed to building shared knowledge and lasting networks supporting regional solutions to local and global challenges. Stakeholders consistently appreciate the MAP process and the dialogue conducted locally. Focus on ownership, transparency, inclusivity and long-term commitments builds trust, while peer-to-peer dialogues ease engagement on difficult issues and mobilise middle-income countries around the SDGs.

Consultation and inclusivity are core to Spain’s approach to development co-operation – a necessity given the diversity of its system. Domestically, Spain has developed whole-of-government and whole‑of‑society approaches and has been able to speak with one voice on key challenges such as debt forgiveness and COVID recovery. In partner countries, Spain has succeeded in agreeing comprehensive bilateral partnership frameworks based on open dialogue with partner country stakeholders and all Spanish co-operation actors, including civil society and local and regional authorities. Such inclusive dialogue helps amplify voices that would not necessarily be heard.

While diversity is a strength of Spain’s development co-operation, it also comes with challenges. Being responsible for a limited share of the ODA budget, the State Secretariat of International Co-operation (SECI) faces challenges steering all actors towards an integrated strategy and taking full advantage of their complementarities. Its enhanced political weight and clearer division of labour are opportunities to address these challenges when drafting the next Master Plan.

Diverse partnerships can make focused and predictable programmes in countries or territories more challenging within a segmented system. As comprehensive documents, MAPs are sometimes seen to contain multiple priorities and small projects. In addition, projects delegated by the EU or funded through the Development Promotion Fund (FONPRODE) are not systematically part of the MAPs, which limits Spain’s ability to link its technical and financial co-operation and mobilise its strong local knowledge and relationships. While technical co-operation offices make considerable efforts to build coherence across whole-of-Spain development co-operation locally, success requires intensive staff resources.

Knowledge sharing and institutional learning are works in progress. Despite impressive efforts to improve reporting at corporate level and renew and build on existing results frameworks in its programming, Spain has limited capacity to collect results or to fully understand the results of its public technical assistance. Efforts to improve institutional learning are challenged by the lack of a sustained strategic vision. Further efforts to systematise data collection, results monitoring and upward information flows could improve knowledge sharing, decision making and steering.

Tackling human resource challenges is fundamental. The split between generalists in Madrid and a pool of experts posted abroad with limited opportunities to work at headquarters creates a divided system. The lack of a development career path, poor terms and conditions and complex contractual arrangements, as well as limited use of the local talent pool all negatively affect Spain’s ability to attract and retain talent and build on internal knowledge. The upcoming comprehensive reform is an opportunity to reassess which skills will be needed and where, in order to deliver on Spain’s ambition.

A number of laws and regulations considerably impede the flexibility, predictability and efficiency of the development programme. Difficulties in providing multi-year funding, and long approval and reporting processes focused on inputs and outputs rather than outcomes, place administrative burdens on all parties and undermine efficiency and the quality of partnerships. Reforming this regulatory framework will be critical for Spain to be able to successfully mobilise all the instruments at its disposal.

In particular, Spain’s current institutional arrangements are holding back financial co-operation. The approval process for FONPRODE operations is very long and cumbersome, even more so considering the small volume of operations. FONPRODE’s model gives it limited ability to steer and govern operations since banking services and financial advice are provided outside of the Spanish Agency for International Development Co-operation (AECID), the implementing agency. FONPRODE could take fuller advantage of being part of AECID to make sustainable development central to its operations, building on the existing architecture and seeking greater complementarity between technical and financial co-operation.

Spain’s humanitarian policy takes a holistic view and reflects new ambitions, but the tools it has developed are narrow in scope. The new humanitarian early recovery fund, for example, covers initial humanitarian assistance, plus a further six months of funding. However, this does not often reflect the reality in fragile contexts where early development transition requires more flexible series of approaches that are less compartmentalised and part of a broader crisis management and development continuum.

Spain did not meet its national commitment to achieve 0.4% GNI as ODA by 2020. Yet, there are positive signs that Spanish development co-operation is moving in the right direction: building on strong public support for development co-operation, the 2022 budget will see the largest increase in ODA in a decade.