Global growth slowed to 3.2% in 2022, well below expectations at the start of the year, held back by the impact of the war in Ukraine, the cost-of-living crisis, and the slowdown in China.

More positive signs have now started to appear, with business and consumer sentiment starting to improve, food and energy prices falling back, and the full reopening of China.

Global growth is projected to remain at below trend rates in 2023 and 2024, at 2.6% and 2.9% respectively, with policy tightening continuing to take effect. Nonetheless, a gradual improvement is projected through 2023-24 as the drag on incomes from high inflation recedes.

Annual GDP growth in the United States is projected to slow to 1.5% in 2023 and 0.9% in 2024 as monetary policy moderates demand pressures. In the euro area, growth is projected to be 0.8% in 2023, but pick up to 1.5% in 2024 as the effects of high energy prices fade. Growth in China is expected to rebound to 5.3% this year and 4.9% in 2024.

Headline inflation is declining, but core inflation remains elevated, held up by strong service price increases, higher margins in some sectors and cost pressures from tight labour markets.

Inflation is projected to moderate gradually over 2023 and 2024 but to remain above central bank objectives until the latter half of 2024 in most countries. Headline inflation in the G20 economies is expected to decline to 4.5% in 2024 from 8.1% in 2022. Core inflation in the G20 advanced economies is projected to average 4.0% in 2023 and 2.5% in 2024.

The improvement in the outlook is still fragile. Risks have become somewhat better balanced, but remain tilted to the downside. Uncertainty about the course of the war in Ukraine and its broader consequences is a key concern. The strength of the impact from monetary policy changes is difficult to gauge and could continue to expose financial vulnerabilities from high debt and stretched asset valuations, and also in specific financial market segments. Pressures in global energy markets could also reappear, leading to renewed price spikes and higher inflation.

Monetary policy needs to remain restrictive until there are clear signs that underlying inflationary pressures are lowered durably. Further interest rate increases are still needed in many economies, including the United States and the euro area. With core inflation receding slowly, policy rates are likely to remain high until well into 2024.

Fiscal support to mitigate the impact of high food and energy prices needs to become more focused on those most in need. Better targeting and a timely reduction in overall support would help to ensure fiscal sustainability, preserve incentives to lower energy use, and limit additional demand stimulus at a time of high inflation.

Rekindling structural reform efforts is essential to revive productivity growth and alleviate supply constraints. Enhancing business dynamism, lowering barriers to cross-border trade and economic migration, and fostering flexible and inclusive labour markets are key steps needed to boost competition, mitigate supply shortages, and strengthen gains from digitalisation.

Enhanced international cooperation is needed to help overcome food and energy insecurity, assist low-income countries service their debts, and achieve a better co-ordinated approach to carbon mitigation efforts.

OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2023

A Fragile Recovery

Summary

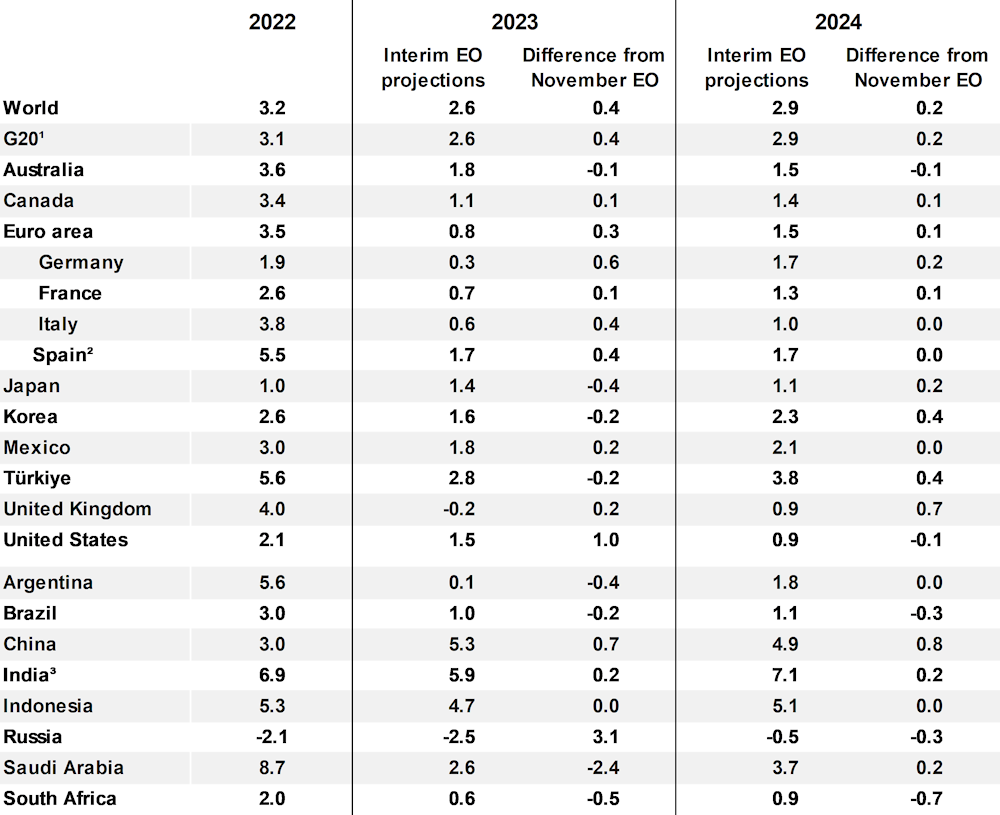

Table 1. OECD Interim Economic Outlook forecasts March 2023

Real GDP growth, year-on-year, per cent

Note: Difference from November 2022 Economic Outlook in percentage points, based on rounded figures. World and G20 aggregates use moving nominal GDP weights at purchasing power parities (PPPs). Revisions to PPP estimates affect the differences in the aggregates.

1. The European Union is a full member of the G20, but the G20 aggregate only includes countries that are also members in their own right.

2. Spain is a permanent invitee to the G20.

3. Fiscal years, starting in April.

Source: Interim Economic Outlook 113 database; and Economic Outlook 112 database.

Table 2. OECD Interim Economic Outlook forecasts March 2023

Headline inflation, per cent

Note: Difference from November 2022 Economic Outlook in percentage points, based on rounded figures. The G20 aggregate uses moving nominal GDP weights at purchasing power parities (PPPs). Revisions to PPP estimates affect the difference in the aggregate.

1. The European Union is a full member of the G20, but the G20 aggregate only includes countries that are also members in their own right.

2. Spain is a permanent invitee to the G20.

3. Fiscal years, starting in April.

Source: Interim Economic Outlook 113 database; and Economic Outlook 112 database.

Table 3. OECD Interim Economic Outlook forecasts March 2023

Core inflation, per cent

Note: Difference from November 2022 Economic Outlook in percentage points, based on rounded figures. The G20 Advanced Economies aggregate uses moving nominal GDP weights at purchasing power parities (PPPs). Revisions to PPP estimates affect the difference in the aggregate. Core inflation excludes food and energy prices.

1. The European Union is a full member of the G20, but the G20 aggregate only includes countries that are also members in their own right.

2. Spain is a permanent invitee to the G20.

Source: Interim Economic Outlook 113 database; and Economic Outlook 112 database.

There are signs of some pick-up in global growth after weakness in late 2022

1. Global growth in 2022 was 3.2%, some 1.3 percentage points weaker than expected in the December 2021 OECD Economic Outlook, reflecting the effects of Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, the drag on household incomes from high inflation, rising interest rates and continued disruptions in China. In the fourth quarter of last year, growth slowed in most G20 economies (Figure 1, panel A). Global trade declined, with a continued recovery in international tourism offset by a drop in merchandise trade volumes (Figure 1, Panel B). Outcomes were particularly soft in the Asia-Pacific region in the last few months of 2022, with output stagnating in Japan, activity in China held back by continued lockdowns and a wave of infections, and a downturn in the tech sector hitting output and exports in Korea. Growth was also weak in Europe, with output declines in many Central and Eastern European economies and energy-intensive industries, amidst strong adverse effects from extremely high energy prices. The main positive surprise in late 2022 came from the United States, with continued labour market resilience outweighing the impact of higher interest rates on private investment.

Figure 1. Global growth slowed through 2022

Per cent, q-on-q

Source: Interim Economic Outlook 113 database; CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis; and OECD calculations.

2. Beyond the G20, some emerging and developing economies that were already facing economic headwinds in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the spike in many commodity prices after the start of the war in Ukraine have also been feeling negative effects from the rise in interest rates in advanced economies over the past year. A number of developing economies in Africa, Asia and the Americas have experienced sharp economic downturns and acute balance of payments pressures.

Recent indicators point to stronger activity in early 2023

3. Monthly data in early 2023 point to a near-term improvement in growth prospects in the largest economies. Activity data in the United States surprised on the upside in January, and labour markets remain tight across almost all G20 economies, including in Europe, supporting private consumption. Survey indicators have also strengthened from the troughs seen in late 2022. Consumer confidence has started to improve, and enterprise survey indicators have stabilised or rebounded in all major regions (Figure 2). In February, more firms reported rising output than falling output in all major economies, with substantial jumps in the United States, the euro area, China and the United Kingdom.

4. The improvement in activity and sentiment in the main G20 economies in early 2023 is due to the decline in global energy and food prices (Figure 3), which boosts purchasing power and should help to lower headline inflation, as well as the expected positive impact of China’s reopening on global activity. The fall in energy prices partly reflects the impact of mild winter temperatures in Europe, helping to preserve gas storage levels, as well as lower energy consumption in many countries. The impact of the measures taken against Russian energy exports has also been more limited than initially expected, with Russia largely maintaining export levels by expanding sales in other markets, albeit at substantially discounted prices. Food and fertiliser prices have also come down from their peak last year. Nonetheless, energy and food prices remain well above the levels seen prior to the pandemic, leaving many lower-income households still facing budget pressures. Food and energy security also remain fragile, especially in emerging and low-income economies and households.

Figure 2. Survey indicators signal an improvement in early 2023

Source: S&P Global; and OECD Main Economic Indicators database.

Figure 3. Energy and food prices have fallen in recent months

Index 2019 = 100

Note: Based on Brent oil prices in USD; TTF natural gas prices for Europe; Newcastle coal price in USD; FAO global price indices for food, cereals and vegetable oil; and urea fertiliser price in USD.

Source: Refinitiv; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations; World Bank; and OECD calculations.

5. Survey data point to a strong pick-up in China in January and February, and part of the pent‑up household savings from the zero-COVID-policy period will likely be spent in 2023, boosting aggregate demand. A resumption in international travel by Chinese residents will provide a further boost to global air traffic and services trade, with the strongest gains likely in neighbouring Asian economies based on visitor patterns prior to the pandemic (Figure 4, Panel A). At the same time, stronger commodity demand from China, which accounts for a large share of consumption in many markets, is likely to put some upward pressure on commodity prices (Figure 4, Panel B). This is particularly the case if Chinese energy demand strengthens significantly, after stagnating in 2022.

6. Global financial conditions have tightened considerably since the start of 2022. Real long-term interest rates have risen sharply, triggering repricing across asset classes, including equities, and generating sizeable unrealised losses on the bond portfolios held by financial institutions. Signs of the impact of tighter monetary policy have started to appear in parts of the banking sector, including regional banks in the United States. In a number of economies, actual and expected credit growth has slowed, even turning negative in some recent bank lending surveys, including in the euro area. This is reflected in the related contraction of the broad money supply in several large economies, after the strong growth seen during the pandemic. The US M2 money supply aggregate recently declined on a year-on-year basis for the first time in more than 60 years. The sustained appreciation in the US dollar through much of 2022 has however been partially reversed, helping to bring down the domestic currency prices of imported food and energy in many countries.

Figure 4. The reopening of China will affect global demand

Note: Panel A: data for Australia are for the year to June 2019 and data for France are for 2018. Panel B: 2021 data for oil, natural gas, fertilisers, maize and cotton, and 2020 for all other commodities.

Source: OECD Interim Economic Outlook March 2020; International Energy Agency; OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook database; World Bank; World Fertilizer Association; and OECD calculations.

Headline inflation is declining, but core inflation is proving sticky

7. Headline consumer price inflation and core inflation (excluding food and energy) generally remain well above central bank objectives, but headline inflation has begun to decline in most economies. This primarily reflects the easing of energy and food prices (Figure 3). There continues to be a marked divergence in inflation rates across countries, with inflation still at relatively low levels in some Asian economies, including China and Japan, but very high in Türkiye and Argentina. The recent easing of headline inflation has also been mirrored in household and market-based inflation expectations in the major advanced economies.

8. The decline in headline inflation has yet to be matched by falling core inflation (Figure 5), since strong cost pressures and, in some sectors, higher unit profits continue to push up prices. Goods price inflation has begun to decline in most countries (Figure 6), reflecting the broader downturn in the sector last year, as well as the gradual normalisation of the composition of demand from goods to services and the easing of global supply chain bottlenecks. In contrast, services price inflation has continued to rise, with higher energy and transport costs being passed through into retail prices, demand for services strengthening, and unit labour cost pressures remaining elevated amidst tight labour markets.

9. Low unemployment and high vacancy rates in most major economies (Figure 7), together with the extended period of high inflation, have put upward pressure on nominal wage growth. However, in some countries, including the United States, the pace of wage increases has now started to level off or even decline. Nonetheless, in most countries wage growth remains at rates that, if sustained for some time, would be inconsistent with inflation returning to target given weak underlying productivity growth, unless corporate profit margins contract.

Figure 5. Core inflation is proving persistent

Per cent, year-on-year

Note: Based on the consumers’ expenditure deflator for the United States, the harmonised index of consumer prices for the euro area and the consumer price index for Japan.

Source: OECD Consumer Prices database; Eurostat; and OECD calculations.

Figure 6. Services price inflation is still rising

Per cent, year-on-year

Note: Based on the consumers’ expenditure deflator for the United States, the harmonised index of consumer prices for the euro area and the consumer price index for Japan. Data for the United States and the euro area are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis; European Central Bank; OECD Consumer Prices database; and OECD calculations.

Figure 7. Labour markets remain tight

Note: Panel A: The average year-on-year percentage change in wages and salaries advertised in job postings on Indeed, controlling for job titles. Panel B: Job vacancies per unemployed is the ratio of the number of unfilled vacancies to the unemployed population aged 15 and over. The unemployed population of Germany is the 3-month average of the unemployed population aged 15-74.

Source: Indeed Wage Tracker; OECD Short-Term Labour Market Statistics database; Eurostat; and OECD calculations.

Growth is projected to remain moderate with inflation declining gradually

10. Global growth is projected to remain at a below-trend rate in 2023‑24, with inflation moderating gradually as the quick and synchronised monetary policy tightening over the past year takes full effect (Figure 8, Figure 13). Lower commodity prices, and the full reopening of China underpin a modest upward revision to the growth projections in 2023 from the OECD Economic Outlook in November 2022, but the growth benefits of these changes should be limited to the short term. Demand is likely to be cushioned by further easing of household saving rates in many countries, with households yet to fully use the additional savings accumulated during the pandemic. The impact of tighter financial conditions is otherwise likely to be felt throughout the economy over time, particularly on private investment. The disruption from the war in Ukraine is also likely to continue to weigh on global output both directly and indirectly through the impact on uncertainty, continuing risks to food and energy security, and the significant changes taking place in commodity markets as price caps and Western embargos on Russian energy outputs take full effect.

11. Average annual growth of global GDP in 2023 is projected to be 2.6%, recovering to 2.9% in 2024, a rate close to the pre‑pandemic trend, but sub-par compared to earlier decades (Table 1, Figure 9). Projected global growth over 2023-24 would be weaker than in any two-year period since the Global Financial Crisis, excluding the slump at the beginning of the pandemic. All but two G20 economies are projected to have slower growth in 2023 than in 2022, with China being a notable exception owing to the easing of anti-COVID restrictions.

Figure 8. Policy interest rates have risen more rapidly than in other recent cycles

Cumulative monthly increase in policy interest rates since the start of the tightening cycle, per cent

Note: “Current” denotes the current policy tightening cycle, “Past” shows the average of the previous three monetary policy tightening cycles. M1-M12 denote months, with the first policy rate increase occurring in month 1 (M1).

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database; Bank for International Settlements; and OECD calculations.

Figure 9. Global growth is weaker than expected prior to the war in Ukraine

Per cent, year-on-year

Note: Projections from the current Interim Economic Outlook and the December 2021 and November 2022 OECD Economic Outlooks.

Source: OECD Interim Economic Outlook 113 database; OECD Economic Outlook 110 database; OECD Economic Outlook 112 database; and OECD calculations.

12. For the United States, growth is expected to be below potential in both 2023 and 2024, as monetary policy moderates demand pressures. While average annual growth is projected to fall both this year and next, quarter‑on‑quarter growth rates are expected to bottom out in the latter half of 2023 and improve thereafter. Growth in the euro area will also be slow in 2023, but the benefits of lower energy prices and declining inflation should help growth momentum to gradually improve, leaving average annual growth in 2024 almost double the projected 0.8% in 2023. The United Kingdom is also expected to have a mild rebound in 2024, with output rising by 0.9% after a year-on-year decline in 2023. Japan, which will have additional fiscal stimulus this year and no change in policy interest rates is projected to grow between 1‑1½ per cent per annum in 2023 and 2024. Korea and Australia will benefit from the expected growth rebound in China, offsetting the impact of tighter financial conditions.

13. The emerging-market economies in Asia are likely to be less affected by the global slowdown, helped by the rebound in China and more moderate inflation pressures. Growth in China is projected to rebound to 5.3% this year, before easing to 4.9% in 2024. India’s growth is projected to moderate to around 6% in FY 2023‑24, amidst tighter financial conditions, before picking to recovering to around 7% in FY 2024‑25, while Indonesia’s economy will continue to expand by between 4.7-5% per annum over 2023-24. Growth in many other emerging‑market economies, including Brazil and South Africa, is projected to be sluggish over the next two years, at about 1% per year on average. Activity in Türkiye is likely to be held back significantly in the early part of 2023 by the large losses from the recent earthquakes, but recover as reconstruction spending picks up, with full year growth of 2.8% in 2023 and 3.8% in 2024. Output in Russia is expected to decline this year and next, as the drag from economic and financial sanctions starts to build.

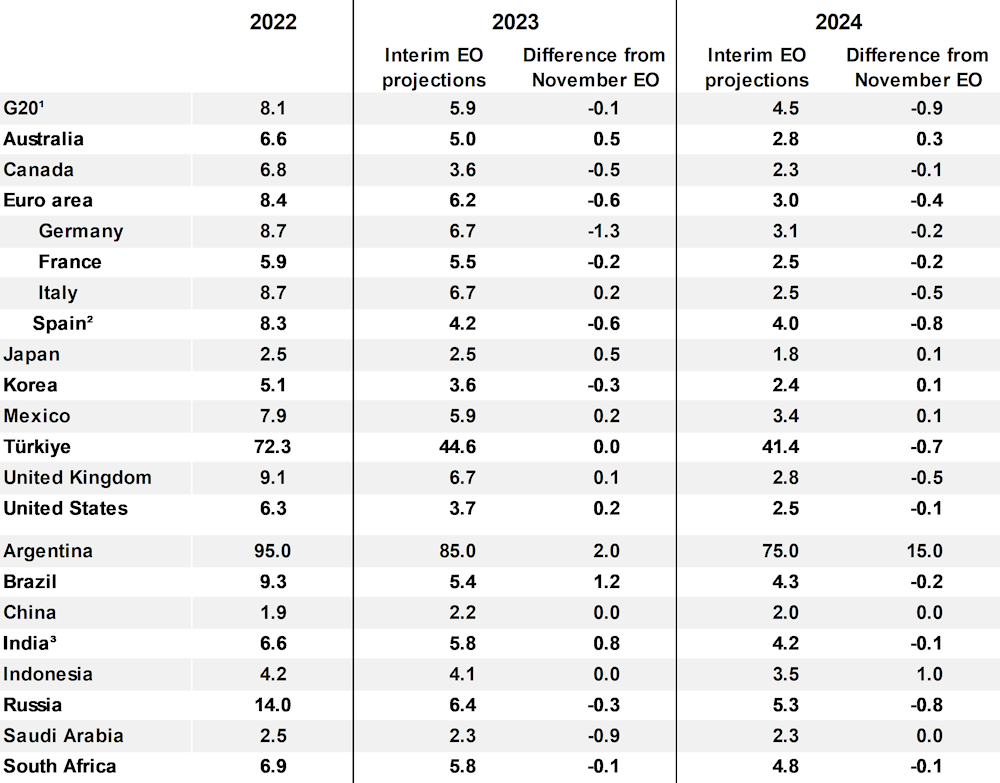

14. With global economic growth slowing, energy and food price inflation subsiding, and monetary tightening by most of the major central banks increasingly taking effect, consumer price inflation is expected to moderate. Headline inflation is projected to decline in 2023 and 2024 in almost all G20 economies (Table 2). Even so, annual inflation will remain well above target almost everywhere through most of 2024 (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Inflation is projected to decline gradually

Annual consumer price inflation, per cent

Note: Projections for India refer to fiscal years, starting in April.

Source: OECD Interim Economic Outlook 113 database.

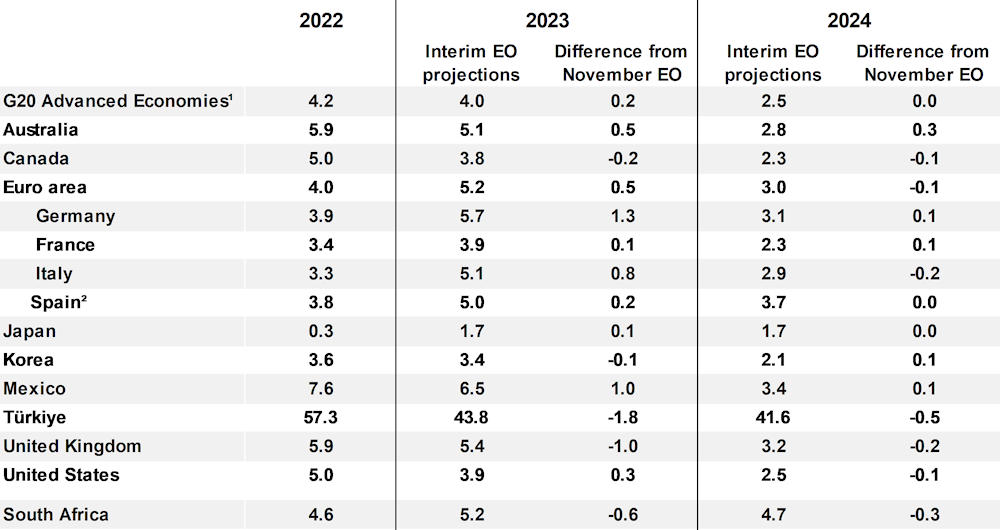

15. In the United States and Canada, where inflation peaked in mid-2022 and where the tightening of monetary policy began earlier than in many other large advanced economies, faster progress in bringing inflation back to target is expected than in the euro area or the United Kingdom. US core inflation (based on the private consumption deflator) is projected to average around 4% in 2023 and 2½ per cent in 2024 (Table 3). By the end of 2024, both headline and core inflation in the United States and Canada would be only a little above 2%. As the pressure from higher food and energy prices eases in Japan, headline inflation is projected to be back below 2% by the end of 2023 and to average 1.8% in 2024. By contrast, with the sharp rises of energy prices in 2022 still working their way through the economy, both headline and core inflation will remain above target in the euro area for longer. Annual headline inflation in the euro area is projected to come down from 8.4% in 2022 to 6.2% in 2023 and 3% in 2024. Core inflation in the euro area, which rose during 2022, is projected to average over 5% in 2023, before easing to 3% in 2024.

16. Most of the emerging-market economies in the G20 are also projected to see gradual declines in inflation over the next two years, although the levels and profiles vary quite widely. The major emerging Asian economies are expected to experience low (China) to moderate (India and Indonesia) inflation rates in 2023-24. Inflation is projected to remain above target in Brazil and Mexico in 2023, but decline within the upper half of the inflation target band by the end of 2024, helped by the early action taken to tighten monetary policy. Inflation is also expected to moderate in South Africa, dropping below 5% by 2024.

Downside risks predominate

17. Risks have become somewhat better balanced in recent months but remain tilted to the downside. In particular, the fraught geopolitical situation ensures that uncertainty remains high, including concerning the course of the war in Ukraine and its consequences for the global economy. An important related risk is a renewed worsening of food security in emerging and developing economies. Despite the improvements in grain shipments from Ukraine from mid-2022 and good harvests in several major wheat-growing countries, the market remains vulnerable both to renewed disruption caused by the war as well as extreme weather events, which have become more common. Trade-related tensions also remain a concern, with the cumulative coverage of goods-related import restrictions imposed by the G20 economies continuing to rise, and several non-G7 countries having introduced new export restrictions on food, feed and fertilisers following the start of the war in Ukraine. Medium-term risks to growth and prices are also rising from growing fragmentation of global-value chains and, in some cases, a shift to higher-cost but less distant locations from parent companies.

18. Another central risk concerns the uncertain scale and duration of the monetary tightening required to lower inflation durably. Continued increases in cost pressures or margins, or renewed signs of an upward drift in medium and longer-term inflation expectations would compel central banks to keep policy rates higher for longer than currently expected, triggering sizeable movements in financial markets, as occurred following the higher-than-expected readings for US job growth and inflation in early 2023.

19. Higher interest rates could also have stronger effects on economic growth than expected, particularly if they expose underlying financial vulnerabilities. While a cooling of overheated markets, including real estate markets, and repricing of financial portfolios are standard channels through which monetary policy takes effect, the full impact of higher interest rates is hard to gauge. Debt levels and debt service ratios were elevated in many economies even before the impact of higher interest rates was felt (Figure 11). Increased stress on households and companies, and the greater potential for loan defaults, raise risks of potential losses at banks and non-bank financial institutions. In addition, sharp changes in market interest rates and in the current market value of bond portfolios could also further expose duration risks in the business models of financial institutions, as highlighted by the failure of the US Silicon Valley Bank in March. Prompt actions to safeguard depositors while penalising shareholders, and enhanced regulation in the aftermath of the global financial crisis reduce the risk of broad financial contagion from such events. Moreover, house prices have already begun to adjust to policy tightening, with nominal price declines now under way in many economies (Figure 12) and real house prices falling even more rapidly given high consumer price inflation. Past experience suggests that slumps in housing markets can exert a substantial drag on economic activity, and significantly heighten financial risks.

20. Many emerging-market economies could also face increasing difficulties in servicing elevated debt and deficits as global interest rates rise, especially in commodity‑importing economies or ones in which there is a mismatch between the currency composition of liabilities and external revenues. Low-income economies are particularly at risk of debt distress. IMF debt‑sustainability analyses for low-income countries suggest that over half of the 69 economies assessed were either experiencing debt distress or at high risk of distress as of January 2023.

Figure 11. Financial vulnerabilities arise from high debt and rising debt service ratios

Per cent

Note: Total debt given by private non-financial debt at market value and general government debt at nominal values. Advanced (AE) and emerging economy (EME) aggregations based on PPP weights.

Source: Bank for International Settlements; and OECD calculations.

Figure 12. House prices have begun to decline as monetary policy takes effect

Per cent change in nominal house prices since most recent peak

Note: The latest value is February 2023 for Australia, Norway and the United Kingdom; January 2023 for Germany, Korea, the Netherlands and New Zealand; December 2022 for Canada, Sweden and the United States. The most recent monthly peak was November 2021 in New Zealand, January 2022 in Australia, February 2022 in Sweden, April 2022 in Canada, May 2022 in Korea, June 2022 in Germany and the United States, July 2022 in the Netherlands, and August 2022 in Norway and the United Kingdom. All data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: CoreLogic; Europace; Federal Housing Finance Agency; Nationwide; Real Estate Norway; Reinz; Statistics Denmark; Statistics Korea; Statistics Netherlands; Teranet-National Bank House Price Index; Valueguard; and OECD calculations.

21. In Europe, the risk of a critical shortage of energy supplies has diminished but not disappeared. Current gas storage levels are near record levels for the time of year, contrary to earlier fears. Consumption has declined sharply in the face of record high prices, helped by warm weather during the Northern Hemisphere winter and investments in energy efficiency. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports also remain at high levels, helped by new offshore storage capacity in some countries and some residual imports by pipeline from Russia. Nonetheless, challenges remain in securing sufficient storage levels for the 2023‑24 winter. Supply from Russia in 2023 is likely to be minimal, in contrast to the early months of 2022, and the likely rebound in demand in China could increase competition for tight global LNG supply. This could push up energy prices once again, resulting in another spike in consumer prices and further economic dislocation. Risks of higher prices also remain in oil markets, given considerable uncertainty as to how Western sanctions on oil and oil products from Russia will affect global supply.

22. A failure to agree on the raising of the US federal debt ceiling is a low probability event, but one that would potentially have substantial adverse consequences. The ceiling was already reached in January 2023, and later this year the scope for procedures to get around that constraint will be nearly exhausted. While an agreement is likely at some point, delays in achieving this would raise uncertainty and create financial turbulence, as in 2013. Failure to reach agreement at all would bring more severe macroeconomic dislocation given the current scale of the Federal budget deficit and the actions needed to close this quickly.

Policy requirements

Monetary policy

23. Most central banks have continued to tighten monetary policy in recent months, reflecting persisting broad price pressures and the need to prevent high inflation from becoming entrenched in inflation expectations and cost pressures. A handful of central banks that tightened monetary policy at an early stage have now announced a pause to assess the economic impact of the cumulative increase in policy rates, including the Bank of Canada and the Central Bank of Brazil. Others, including the Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia, have continued to tighten, while starting to reduce the pace of tightening and communicating that policy rates will remain high for an extended period of time.

24. Financial conditions are also now being tightened in a number of advanced economies due to reductions in central bank balance sheets, either by not (or not fully) reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds or by active sales of securities. The impact of quantitative tightening is uncertain, with few previous precedents to inform policy analysis. Nonetheless, it is likely to be lower than that of quantitative easing, which had both market liquidity effects and additional effects from signalling the easier stance of monetary policy when policy rates were at their effective lower bound. In the event that significant financial vulnerabilities materialise, as in the United Kingdom last autumn and the United States at present, clear communication will be essential if quantitative tightening is to continue as planned alongside temporary policy measures designed to improve market liquidity and minimise the risk of contagion.

25. Calibrating domestic monetary policy actions is difficult and policies will need to remain responsive to new data, given uncertainty about the speed at which higher interest rates take effect and the potential spillovers from restrictive policy in other countries. Simultaneous tightening by many countries is likely to limit the effects of domestic policy tightening on exchange rates, potentially lengthening the period of time or raising the degree of policy tightening needed to return inflation to target. At the same time, the widespread tightening by many countries is likely to reduce global demand and prices to a greater extent.

26. Several quarters of positive forward-looking real interest rates and below-trend growth will likely be needed to lower resource pressures durably and achieve sustained disinflation, particularly where demand pressures are an important source of inflation. Policy interest rates in the advanced economies are projected to peak at 5¼‑5½ per cent in the United States, 4¾ per cent in Canada, 4¼ per cent in the euro area (the main refinancing rate) and the United Kingdom, and 4.1% in Australia in 2023 (Figure 13, Panel A). The projected decline in inflation over the next two years could allow a mild policy easing in some economies in 2024, particularly ones where the tightening cycle is already close to completion. In Japan, where underlying price pressures remain relatively modest, an accommodative policy stance is assumed to be maintained but with further gradual adjustments to the yield curve control framework to allow a steeper yield curve.

27. Tighter global financial conditions, the continued rise in policy rates in the advanced economies and persisting inflation pressures limit the room for policy manoeuvre in most emerging-market economies (Figure 13, Panel B). The differential between domestic and US policy rates is likely to remain an important policy consideration, especially in countries with sizeable foreign currency denominated debt and where inflation expectations are particularly sensitive to the domestic currency price of food and energy. The frontloading of policy tightening in Brazil, could allow some easing in policy interest rates from the latter half of 2023, with India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa all starting to lower policy rates only in 2024.

Figure 13. Policy interest rates in the major economies

Per cent, end-of-quarter

Note: Main refinancing rate for the euro area.

Source: OECD Interim Economic Outlook 113 database.

Fiscal policy

28. Over the past year, many countries have introduced new measures, or extended existing ones such as subsidies, to cushion the impact of higher food and energy prices on households and businesses. In the absence of such support there would almost certainly have been sizeable real income declines in many countries and widespread hardship amongst poorer households. With energy and food commodity prices below their recent peaks but still well above the levels seen only a few years ago, there is a case for gradually withdrawing broad policy support but continuing efforts to provide targeted support for those most in need. A timely reduction in aggregate support, together with steps to improve targeting, would help ensure fiscal sustainability, preserve energy-saving incentives, and limit additional demand stimulus at a time of high inflation.

29. Support to energy consumers was about 0.7% of GDP in the median OECD economy in 2022 but above 2% of GDP in some countries, especially in Europe. For the OECD as a whole, similar levels of support are foreseen for 2023 (Figure 14), though the eventual fiscal costs will heavily depend on the evolution of energy prices. Policy support has so far been predominantly untargeted. Extensive use has been made of measures such as price caps or lower VAT rates on the full amount of energy consumed, which reduce marginal energy prices for all households or firms (Figure 14). Countries have also implemented untargeted reductions in average energy prices through energy-related income support, including via price caps that apply only up to a particular consumption threshold. Though easy to implement in a timely way, these forms of support are costly and, when marginal energy prices are set below market prices, weaken incentives to reduce energy use. Income support unrelated to energy use, which can be relatively well-focused due to targeted budgetary transfers, is expected to account for only a limited share of total support in 2023.

30. Targeting requires the identification of the households and firms most in need of support. Households already receiving low-income-related assistance are one indicator, but others could include the inability to renovate an energy‑inefficient dwelling or high energy needs due to age or illness. Advantage should be taken of digitalisation, combining different databases, and making broader use of digital tools for data collection (such as smart meters) and faster payment delivery. Making price caps applicable only up to energy consumption levels clearly below average consumption, and focusing support on otherwise-viable companies, especially SMEs, would improve the design of support schemes and the incentives to lower energy consumption. More broadly, support should incentivise energy efficiency, facilitate adjustment to higher energy costs, and avoid hampering reallocation by preserving energy‑intensive activities that are not sustainable in the medium term.

Figure 14. Fiscal policy support remains largely untargeted

Cost of fiscal support by type of measure, USD billions, calculated using 2022 bilateral exchange rates

Note: Based on an aggregation of support measures in 42 countries. Support measures are in gross terms, i.e., not accounting for the effect of possible accompanying energy-related revenue-increasing measures, such as windfall profit taxes on energy companies. Where government plans have been announced but not legislated, they are incorporated if it is deemed clear that they will be implemented in a shape close to that announced. Measures classified as credit and equity support are not included. When a given measure spans more than one year, its total fiscal costs are assumed to be uniformly spread across months. For measures with no officially announced end-date, an expiry date is assumed and the fraction of the gross fiscal costs that pertains to 2022-23 has been retained.

Source: OECD Energy Support Measures Tracker; and OECD calculations.

Structural policy ambition needs to be rekindled

31. Both the immediate conjuncture and longer-term trends point to the important role for supply‑boosting structural reforms, in advanced and emerging economies alike. A substantial part of the worldwide upturn in inflation is estimated to have been driven by supply factors, as shown in the November 2022 OECD Economic Outlook. Rekindling reform efforts to reduce constraints in labour and product markets and strengthen productivity growth would both improve sustainable living standards and reinforce the recovery from the current slowdown by mitigating supply shortages and inflation pressures.

32. The current slowdown adds to the longstanding challenges for growth, resilience and well‑being from population ageing, the acceleration of digitalisation and the need to reduce carbon emissions. Underlying growth prospects have weakened considerably over the past decade, both in advanced and emerging-market economies (Figure 15, Panel A). In part, this is a function of demographic trends: as populations have aged, the contribution to potential output growth from increases in the working-age population has declined over time, although this was offset to some degree by higher employment rates. Primarily, however, the fall in the potential growth rate reflects slower underlying growth in labour productivity (Figure 15, Panel B), which has two components: capital per worker and total factor productivity (productive efficiency). Total factor productivity has grown more slowly over the past decade than in the decades before the global financial crisis, and capital investment has been much weaker.

Figure 15. Underlying growth prospects have slowed

Per cent, average per annum over the period shown

Note: In Panel A, G20 aggregates are combined using PPP weights. In Panel B estimates for the non-OECD economies are for 2002-2010 instead of 1996-2010 due to data unavailability in some countries.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 112 database; and OECD calculations.

33. One common priority in reviving trend growth in OECD economies is therefore the need to boost investment in a sustained manner and enhance productive efficiency. Reviving business dynamism by addressing barriers to the entry of young innovative firms and the exit of struggling firms would enhance competition, spur investment, and help ensure the necessary reallocation of resources across activities. Keeping international borders open to trade and investment and removing obstacles to cross-border trade in services and economic migration would help countries alleviate near-term supply-side pressures and improve future growth prospects. Strengthening workforce skills through well-designed adult learning policies, as well the number and gender mix of students studying science and technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) would help to boost the use of digital technologies and enhance labour market inclusion. Collectively, stronger skills, greater investment in high-speed broadband, and enhanced competition would substantially enhance the beneficial effects of digital technologies for productivity (Figure 16).

34. Large differences across countries in labour force participation rates, including gender gaps, also point to considerable scope for increasing total participation in the labour market. Overcoming the obstacles to greater female labour force participation can involve such reforms as ensuring sufficient entitlement to low-cost high-quality childcare, adapting available childcare to the working hours of different groups of workers, facilitating flexible working styles (including online work), and using the tax-benefit system to incentivise second earners to enter the labour market.

Figure 16. A range of structural policies can boost digital technology diffusion and productivity

Effect of reform on multifactor productivity of the average EU firm after 3 years, per cent

Note: Estimates of the impact of closing half the gap with the best-performing EU countries in a range of structural and policy areas. The effects correspond to the estimated productivity gains associated with greater diffusion of high-speed internet, cloud computing, and Enterprise Resource Planning and Customer Relationship Management software. 'Upgrading skills' covers participation in training, quality of management schools and adoption of High Performance Work Practices. 'Reducing regulatory barriers to competition and reallocation' includes lowering administrative barriers to start-ups, relaxing labour protection on regular contracts and enhancing insolvency regimes. 'Easier financing for young innovative firms' covers the development of venture capital markets and the generosity of R&D tax subsidies.

Source: Sorbe, S. et al. (2019), 'Digital dividend: Policies to harness the productivity potential of digital technologies', OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 26, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Climate change is among the areas where more international cooperation is needed

35. International cooperation and multilateralism are key to ensuring that the global economy strengthens in a way that is inclusive and sustainable. In this context, the launching in February 2023 of the Inclusive Forum on Carbon Mitigation Approaches (IFCMA) is intended to help its members achieve the common global net zero objective. The IFCMA aims to improve international collaboration through data sharing, mutual learning and dialogue. The first concrete actions are to take stock of the policy instruments in use across members of the Forum and measure their emission‑reducing effects.

36. The net zero transition, a vital objective in its own right, also offers an opportunity to help revive investment and innovation and so to contribute to raising potential growth rates. The International Energy Agency estimates that by 2030 annual global investment in clean energy will have to be in excess of USD 4½ trillion (at 2021 prices), up from an estimated USD 1.4 trillion in 2022. Measures to achieve the necessary increase in investment in clean energy include “green” public investment and subsidies, together with a clear commitment to pricing emissions and regulatory standards that make more investment projects viable. It is also essential to reduce environmental policy uncertainty, which has a negative impact on investment in both fossil fuels and clean energy, but to date most emissions remain under-priced and many policy signals are still unclear.