Recent developments, macroeconomic policies and short-term prospects

The housing boom

Fiscal sustainability

Inclusiveness for women, youth and seniors

Immigration policy

Reforms to increase productivity

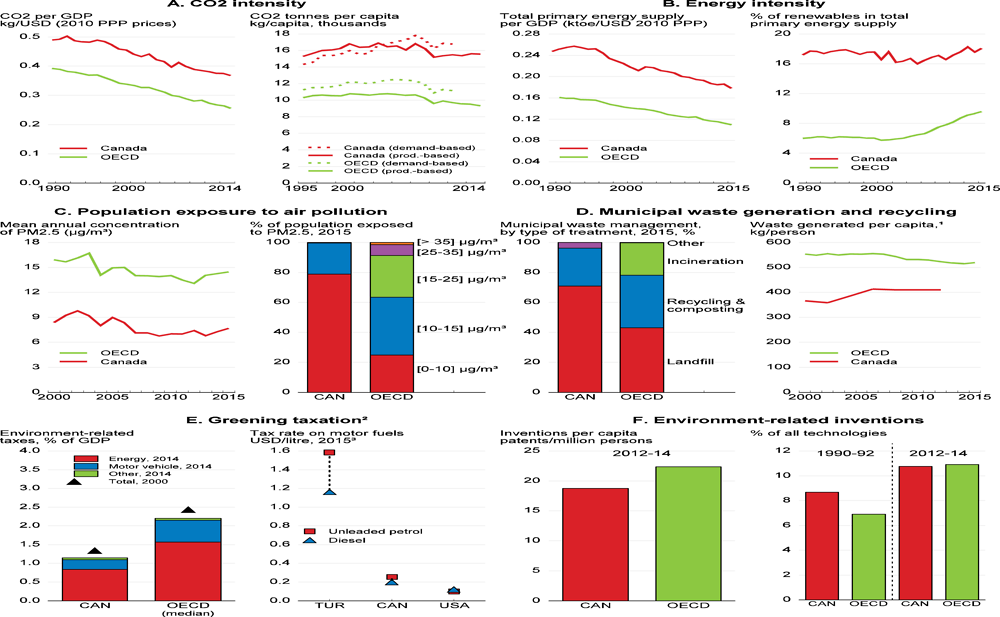

Environmental sustainability

OECD Economic Surveys: Canada 2018

Key Policy Insights

Abstract

The Canadian economy has recovered from the weak patch caused by the 2014 energy price slump. Good policy settings supported this recovery. Monetary policy was quickly eased and fiscal policy became stimulatory. The stimulus measures taken by the federal government were also aimed at making economic growth more inclusive and stronger in the long term. They included income tax cuts for the middle class, the introduction of the Canada Child Benefit and a large increase in infrastructure investment. And structural policy settings that contribute to the flexibility of the Canadian economy further supported the return to buoyant growth.

House price increases have been among the fastest in the OECD, creating affordability challenges that are most acute in fast-growing major cities. Macro-prudential measures have mitigated associated economic risks, but highly indebted borrowers will be vulnerable to high debt-service loads as interest rates increase.

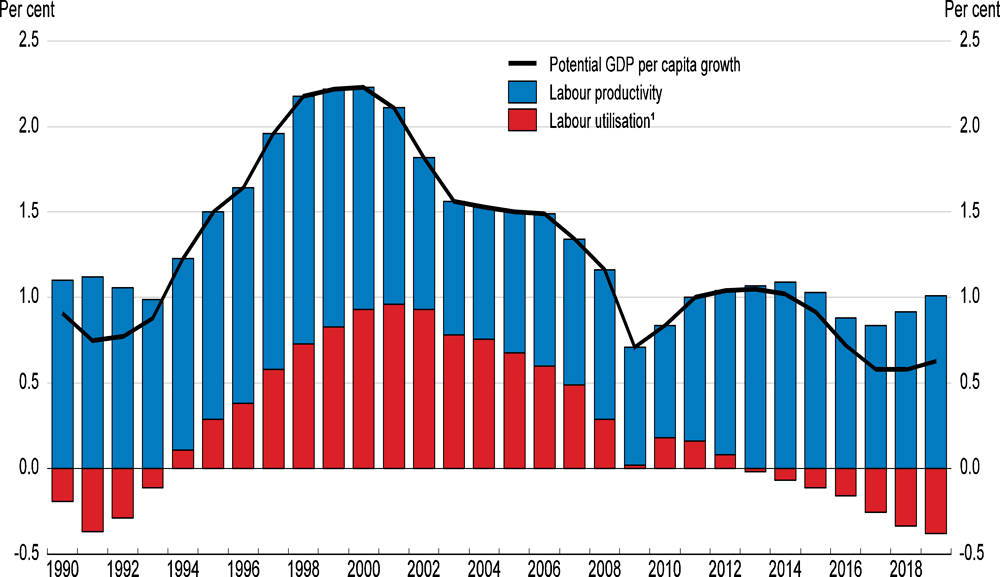

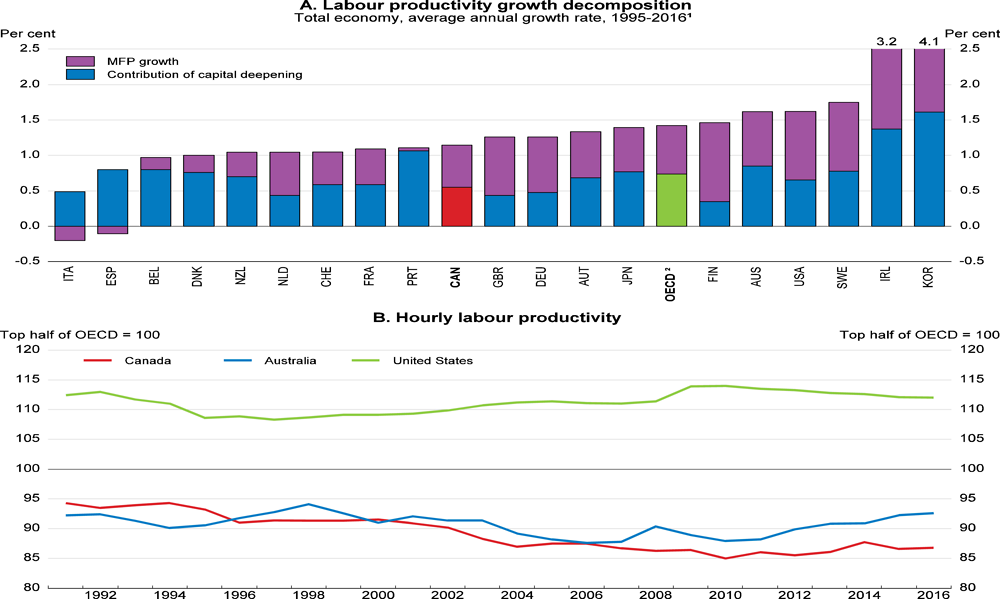

Canada faces longer-term challenges associated with an ageing population and weak productivity growth. Already, population ageing has reduced the contribution of labour utilisation (i.e. employment as a share of the population) to growth in potential real GDP per capita, cutting its annual average growth rate to 0.6%, which is less than the OECD average (1.1%) (Figure 1). The effects of population ageing are set to intensify over coming decades. And labour productivity growth remains below the OECD average. Labour productivity continues to be well below that in the top half of OECD countries.

Figure 1. Decomposition of potential real GDP per capita growth in Canada

1. Population aged 15-74 years old.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook 103 database.

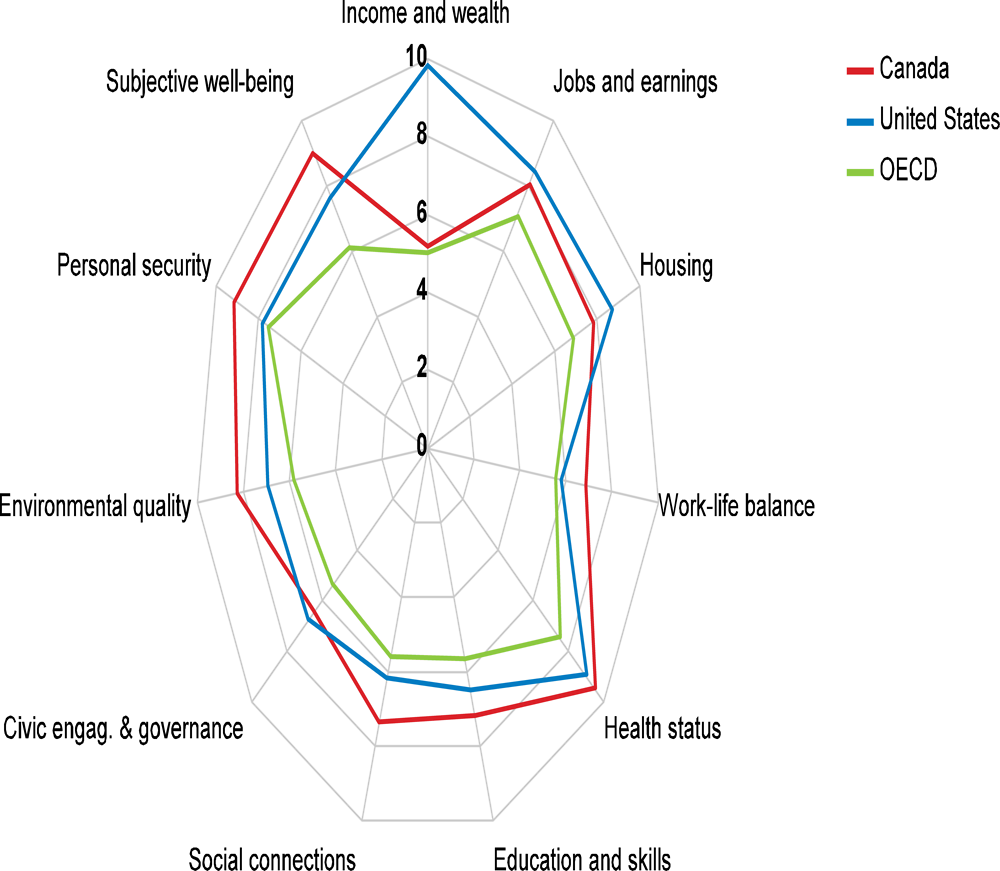

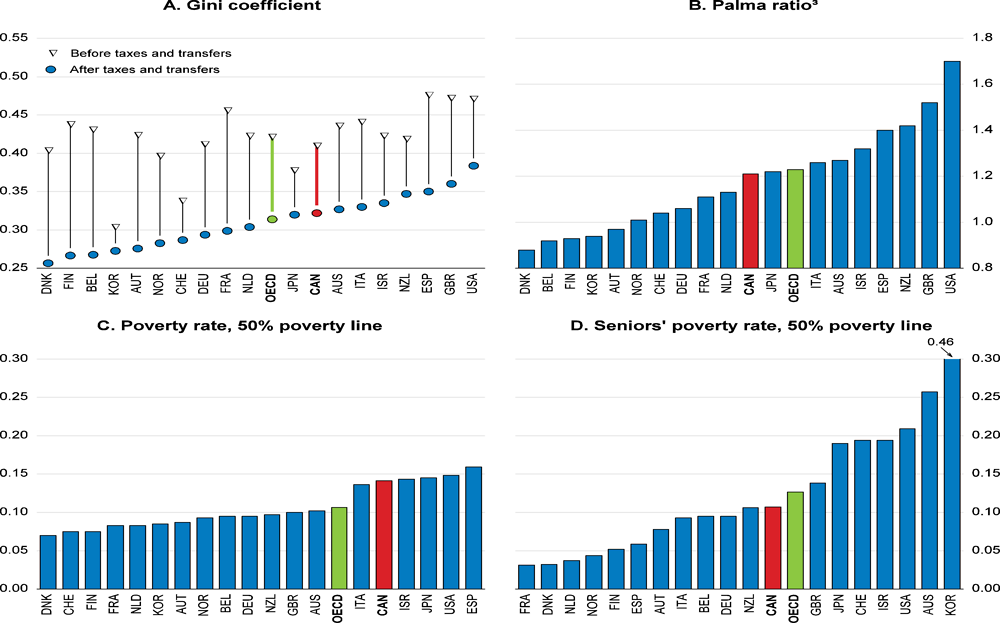

Canada scores highly in most dimensions of the OECD’s Better Life Index (Figure 2). Outcomes for health status, education and skills, social connections, environmental quality, personal security and self-assessed measures of well-being are all much above average. However, this does not mean that all Canadians experience high well-being. Income inequality among the working-age population is around the OECD average and has changed little since 2000, with less-than-average redistribution (Figure 3, Panels A and B). The relative poverty rate (based on a poverty line of 50% of median household income) is well above the OECD average (Panel C). By contrast, the over-65 poverty rate is below the OECD average, pointing to the effectiveness of Canada’s retirement income system (Panel D). Wealth inequality has also changed little since 2000, with the top fifth holding around two thirds of net wealth.

Figure 2. Well-being in Canada is high

Better Life Index,¹ 2017 edition

1. Each index dimension is measured by one to four indicators from the OECD Better Life Index (BLI) set. Normalised indicators are averaged with equal weights. Indicators are normalised to range between 10 (best) and 0 according to the following formula: (indicator value - minimum value) / (maximum value - minimum value) x 10. The OECD aggregate is weighted by population. Please note that the OECD does not officially rank countries in terms of their BLI performance.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Better Life Index, www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org.

Canadian women do well on a number of measures including years of education and life satisfaction, but gender inequality in earnings is considerably larger than the OECD average, and the gender employment gap has not shrunk since 2009. The skills of young Canadians have deteriorated and young males at the bottom of the earnings distribution have experienced weak wage growth. While the relative poverty rate for seniors is low, it has increased steadily since the mid-1990s.

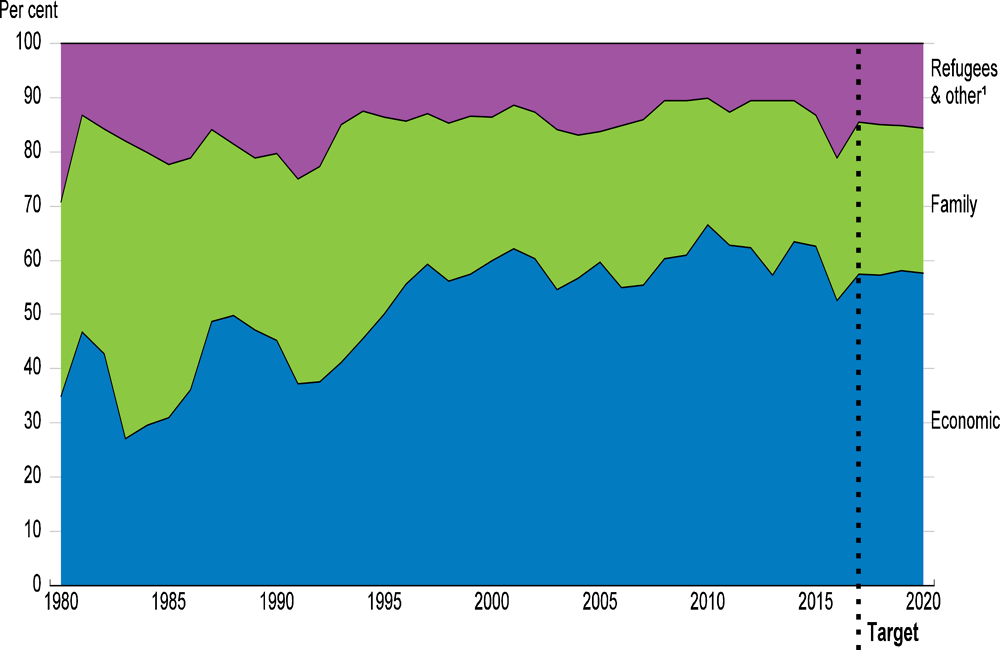

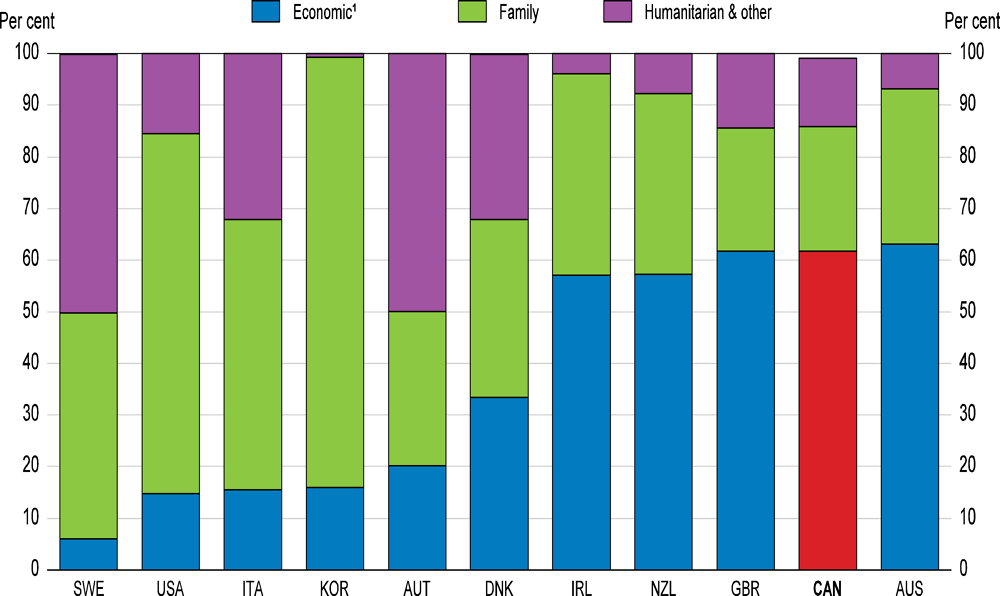

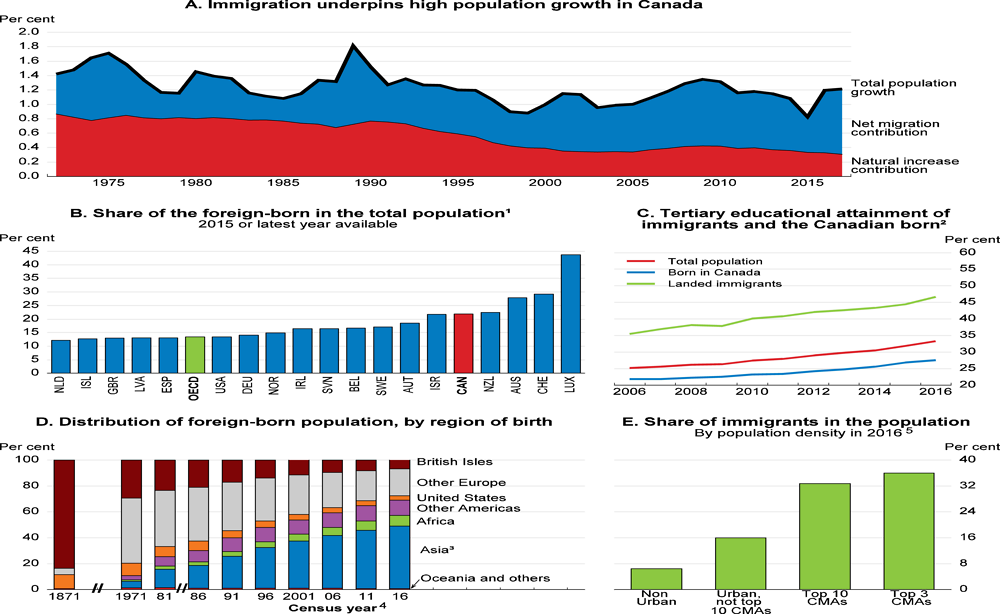

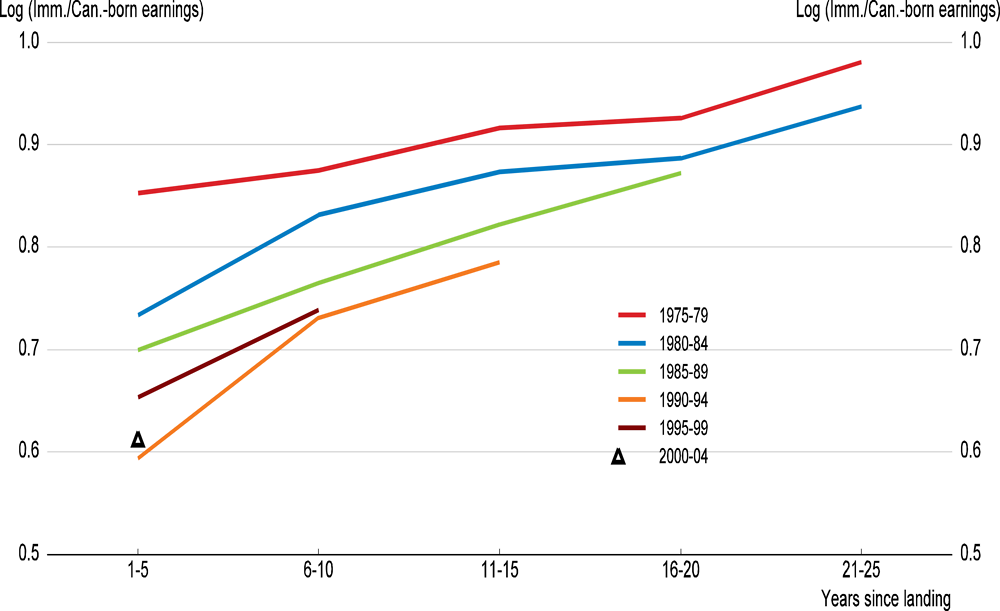

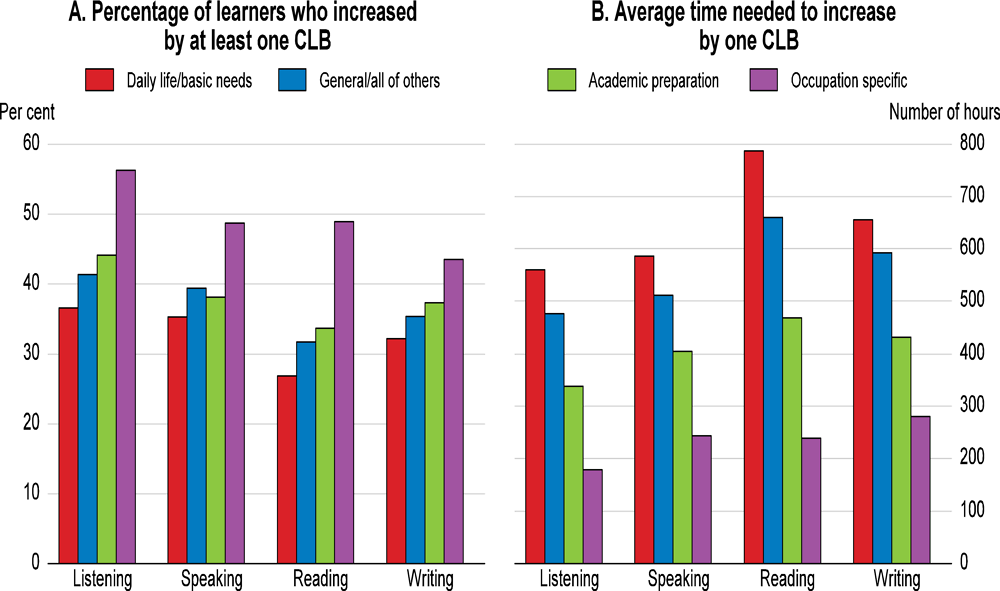

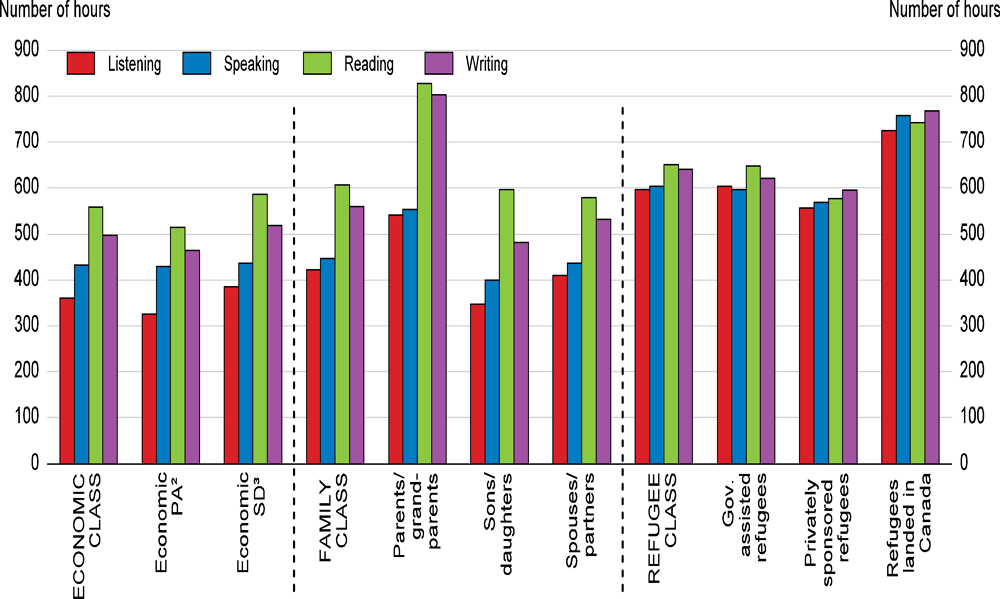

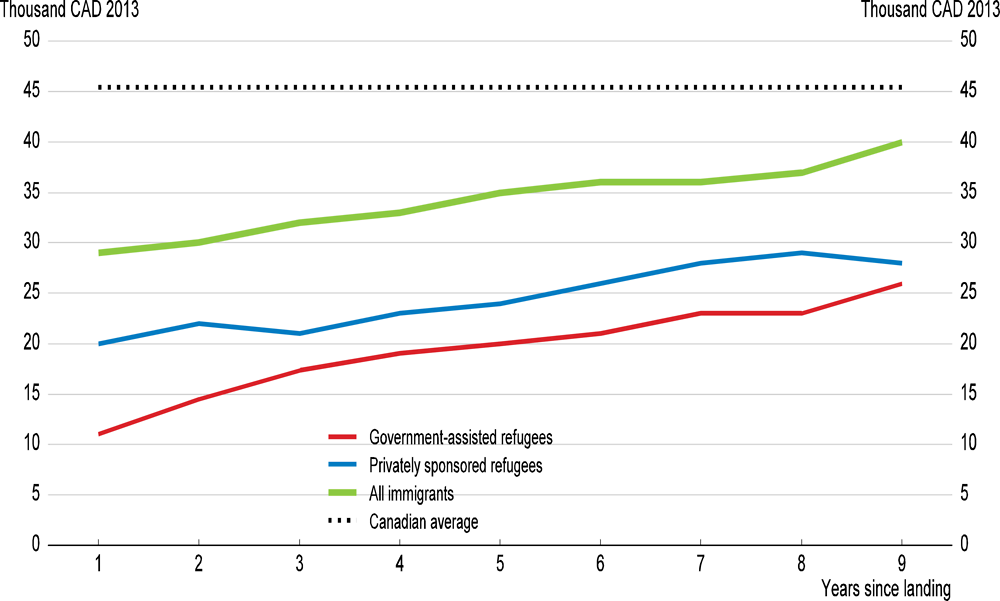

Canada’s immigration policies are amongst the most successful in the world. It welcomes large numbers of immigrants from diverse backgrounds, who contribute to the economic dynamism and cultural diversity of the country, and maintains high levels of social cohesion. On most measures, immigrants are well integrated. However, labour-market integration challenges remain. Immigrants earn considerably less than the Canadian-born with similar education attainment, age and place of residence. Narrowing this gap by selecting immigrants with higher earnings prospects and improving integration measures would result in more immigrants fully realising their potential, boosting their well-being.

Figure 3. Income distribution and relative poverty rates¹

2016 or latest available year²

1. Working-age population in Panels A, B and C. Population over 65 in Panel D.

2. 2014 data for the OECD aggregate.

3. Ratio of income of the top 10% to income of the bottom 40%.

Source: OECD, Income Distribution database, http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/income-distribution-database.htm.

Against this background, the main messages of this Economic Survey are:

House prices and household debt are high, notably in Toronto and Vancouver, undermining housing affordability and posing economic risks.

Improving labour market outcomes for women, youth and seniors would help to counter the effects of population ageing and make growth more inclusive.

Enhancing labour-market integration of immigrants would increase inclusiveness, as well as productivity and incomes.

Recent developments, macroeconomic policies and short-term prospects

Economic growth has recently eased towards more sustainable rates as capacity constraints tighten

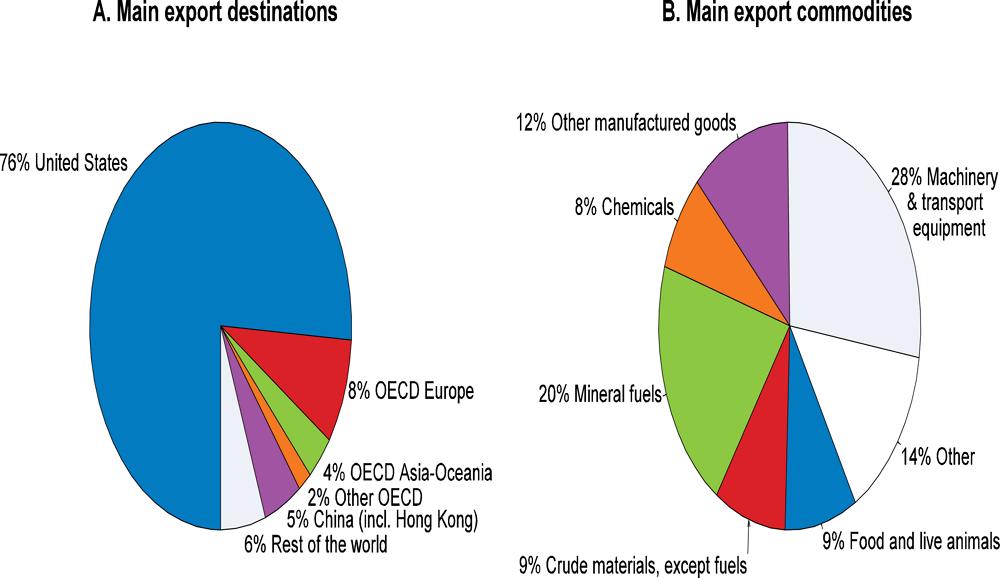

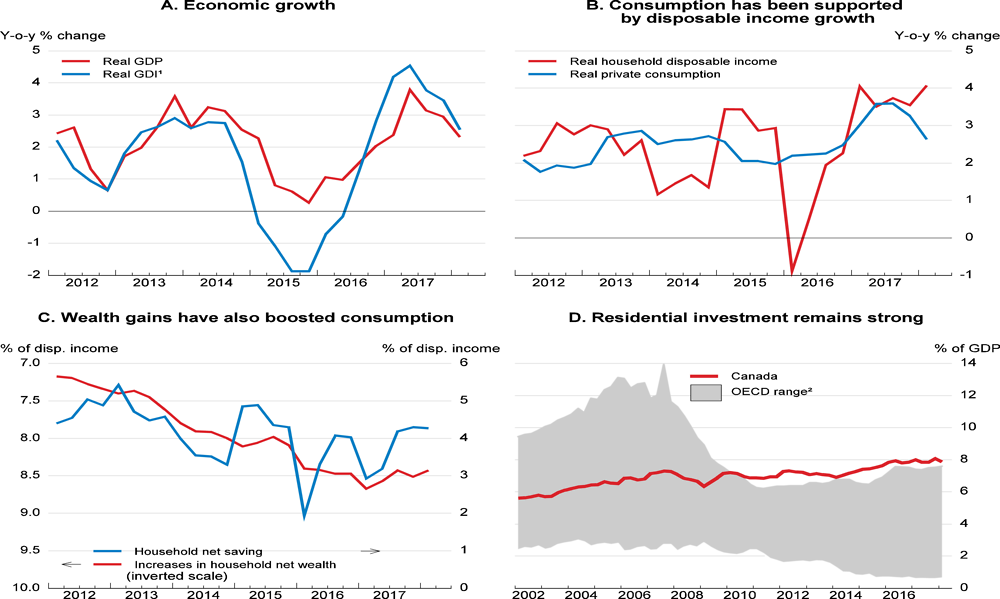

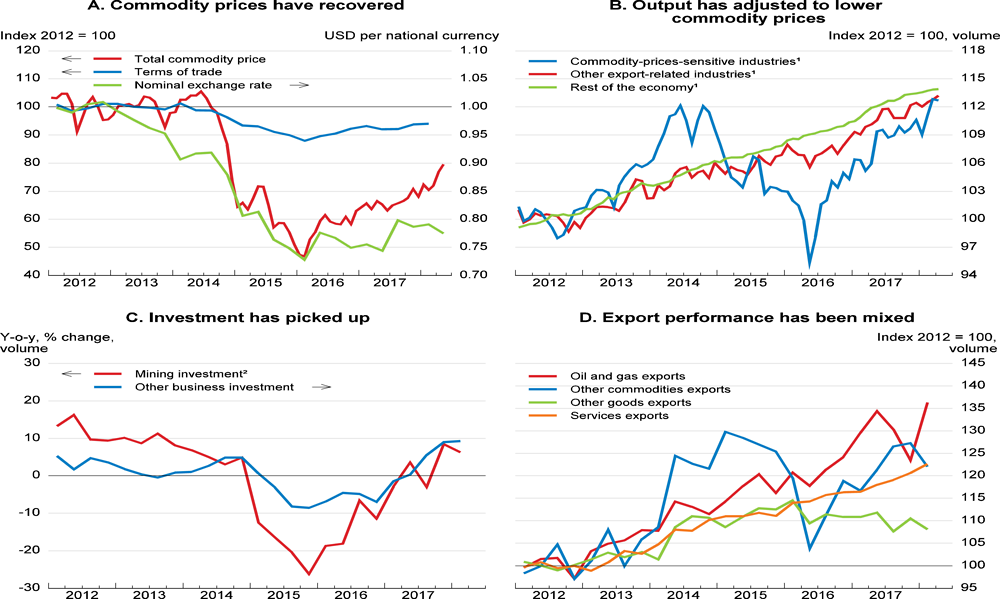

Growth has returned to a more sustainable pace following strong increases until mid-2017 (Figure 4). Private consumption, which was the major driver in 2017, slowed late in the year with the removal of some monetary policy stimulus and smaller wealth gains from house price gains. The GDP share of residential investment is the OECD’s largest but is far below the pre-crisis peaks in countries such as Ireland and Spain that experienced housing bubbles (Panel D). Canada’s export mix means it is highly exposed to developments in the US economy and commodity markets (Figure 5). Adjustment to the fall in commodity prices that started in 2014 is now complete, with the mid-2016 rebound in commodity-producing industries boosting growth. Business investment has picked up but remains weaker than before the commodity price fall, in part because upstream oil and gas investment is being held up by pipeline capacity constraints and regulatory barriers to their expansion, which have curtailed exports as well.

Figure 4. Factors driving the economic expansion

1. Real Gross Domestic Income (GDI) equals real GDP adjusted for changes in the terms of trade.

2. Excluding Canada.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 380-0065; OECD, Economic Outlook database.

Figure 5. Exports of goods by market and commodity

Share of total exports, 2017

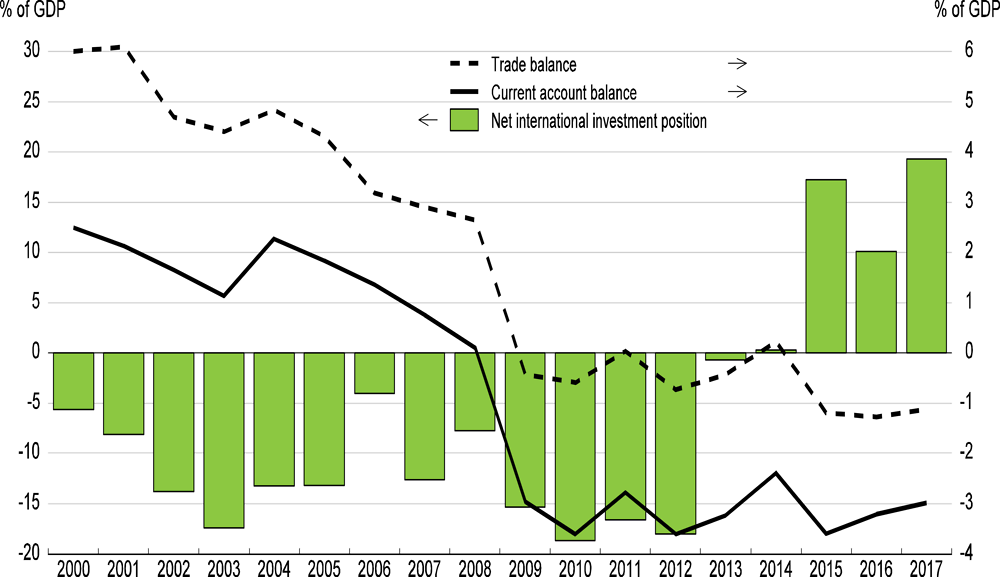

The real effective exchange rate has recovered along with commodity prices since the start of 2016, although it has fallen in recent months owing to US fiscal stimulus and the threat of tariffs on exports to the United States and remains well below 2010-13 levels. Non-commodity goods exports have seen little growth (Figure 6). The current account has been in deficit since the Global Financial Crisis, and in 2017 Canada recorded the third-largest deficit (as a share of GDP) among OECD countries. Even so, Canada's net international investment position turned positive in 2014 (Figure 7), driven by the effects of commodity price falls during 2014 and 2015: depreciation of the Canadian dollar increased the net position by 20 percentage points of GDP, while a sharp fall in the value of Canadian assets held by foreigners contributed a further 10 percentage points (LeBoeuf and Fan, 2017[1]).

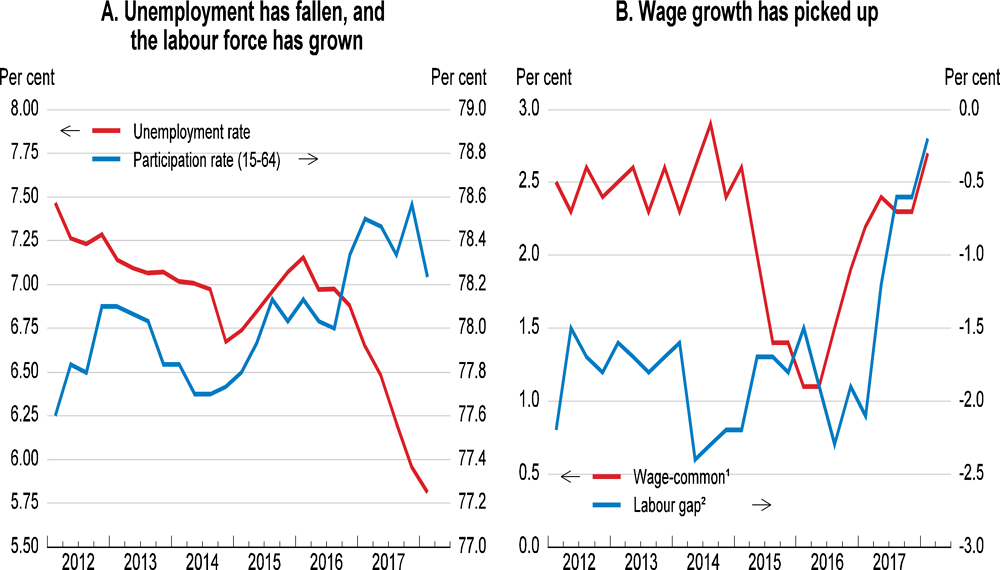

Employment growth has been strong, and the unemployment rate has equalled the record low since comparable records began in 1976. The rate is now below the OECD’s estimates of the structural rate, although such estimates are quite uncertain. The youth (15-24) unemployment rate has fallen to 11%, low historically and compared with the OECD average of 13%. At the same time, more people have entered the labour force (Figure 8, Panel A). The working age (15-64) employment rate has exceeded the previous cyclical peak from 2008, although the Bank’s labour market indicator points to some remaining slack owing to a drop-off in working hours of full-time employees that has not yet been fully reversed despite increased employment being accompanied by an increase in average hours per worker in 2017.

Figure 6. Adjustment to the fall in commodity prices is complete

1. Three-month moving average of real output. For more detail on the sectoral definition, see notes in Bank of Canada (2016).

2. Includes oil and gas. Also includes some engineering structures investment that may relate to other sectors.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook database; Bank of Canada (2016), Monetary Policy Report, April, Chart 9 updated; Statistics Canada, Tables 176-0075, 379-0031, 380-0068 and 380-0070.

As in many other countries, labour market strength was slow to translate into wage growth, but it has now picked up (Figure 8, Panel B). The latest Labour Force Survey data show hourly wage growth of close to 3% per year for full- and part-time employees alike (Statistics Canada, 2018[2]). Wage growth will be boosted over the next few years by increases in provincial minimum wage rates (Table 1). Bank of Canada researchers estimate that these increases will boost average hourly wage rates by 0.7% and inflation by around 0.1 percentage point in 2018, while reducing employment and GDP by 0.3% and 0.1%, respectively (Brouillette et al., 2017[3]).

Figure 7. External sector indicators

Figure 8. The labour market is tightening

1. Composite measure of wage pressures summarising data from the Labour Force Survey, National Accounts, Productivity Accounts, and Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours. For more detail, see Brouillette et al. (2018).

2. Deviation of aggregate hours worked from their estimated potential level.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook and Short-Term Labour Market Statistics databases; D. Brouillette et al. (2018), “Wages: Measurement and Key Drivers”, Staff Analytical Note 2018-2, Bank of Canada, charts 3 and B-3; Bank of Canada (2018), Monetary Policy Report, April.

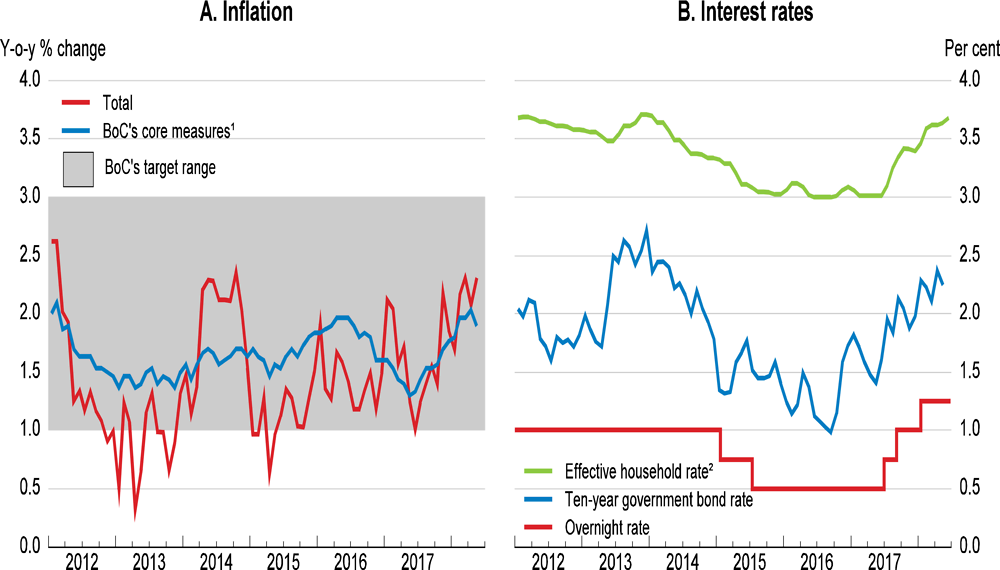

Consumer price inflation has increased to around the mid-point of the Bank of Canada’s 1-3% annual medium-term target band, as have the Bank’s preferred underlying inflation measures (Figure 9, Panel A). Inflation expectations are well-anchored, with almost all responses to the latest Business Operations Survey expecting inflation to fall within the target band.

Table 1. Scheduled minimum wage increases vary considerably across provinces

|

Minimum wage as of: |

Percentage increase |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 January 2017 |

1 January 2019 |

||

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

10.50 |

11.22 |

6.9 |

|

Prince Edward Island |

11.00 |

11.55 |

5.0 |

|

New Brunswick |

10.65 |

11.22 |

5.4 |

|

Nova Scotia |

10.70 |

11.07 |

3.4 |

|

Québec |

10.75 |

12.00 |

11.6 |

|

Ontario |

11.40 |

15.00 |

31.6 |

|

Manitoba |

11.00 |

11.35 |

3.2 |

|

Saskatchewan |

10.72 |

11.18 |

4.3 |

|

Alberta |

12.20 |

15.00 |

23.0 |

|

British Columbia |

10.85 |

12.65 |

16.6 |

Note: In provinces where minimum wages as of 1 January 2019 are yet to be announced, these were calculated based on minimum wages as of 1 January 2018, incorporating 2% CPI growth where minimum wages are indexed to the CPI.

Macroeconomic policies are becoming less expansionary

Some monetary stimulus has been withdrawn through three official interest rate hikes since mid-2017 (Figure 9, Panel B). With the economy around potential, growth near the potential rate and core inflation at the mid-point of the target band, monetary stimulus would appear to be steadily less necessary. The OECD assumes that the policy rate will be progressively increased by 75 basis points to 2.0% by the end of 2019, which remains below the Bank of Canada’s estimated range for the neutral rate (2.5-3.5%).

Figure 9. Inflation has returned to near the middle of the Bank of Canada’s target range

1. Average of the Bank of Canada’s 3 preferred core inflation measures (CPI-trim, median and common).

2. Weighted-average of various mortgage and consumer credit rates.

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 326-0022, 326-0023, 176-0043 and 176-0048; Bank of Canada, https://credit.bankofcanada.ca/financialindicators.

Rising global long-term interest rates will also tighten monetary conditions. Global term premia (i.e., the difference between long- and short-term rates) are likely to rise as the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank unwind quantitative easing. The Bank of Canada estimates that 50-75% of changes in US term premia, which are also affected by ECB premia, flow into Canadian term premia. Canadian long-term rates are currently about 60 basis points below US rates, a historically wide margin, showing confidence in Canadian policy settings.

The overall stance of fiscal policy is estimated to have been stimulatory over the past two years, during which the underlying primary budget balance of general government declined by 1.8% of GDP, to be neutral in 2018 and slightly stimulatory in 2019 (Table 2). The 2016-2017 stimulus primarily reflects federal-level developments, while that in 2019 primarily reflects developments in Ontario. The 2016-17 stimulus supported the economy during the weak patch caused by the fall in oil prices, but, with adjustment now complete and the economy back around potential, such support is no longer warranted. While the federal debt-to-GDP ratio is likely to decline somewhat over the five-year budget planning horizon, the government has dropped its other objective of returning the budget to balance over that period Table 3).

Table 2. Fiscal projections

As a percentage of GDP

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Projections |

|||||

|

Revenues |

39.8 |

39.6 |

39.3 |

39.0 |

39.0 |

|

Expenditures |

39.9 |

40.7 |

40.3 |

40.0 |

39.9 |

|

Budget balance |

-0.1 |

-1.1 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

|

Primary balance |

0.5 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

|

Underlying primary balance |

1.7 |

0.9 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.6 |

|

Change |

0.6 |

-0.8 |

-1.0 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

|

Gross debt |

97.5 |

97.8 |

93.8 |

93.6 |

93.5 |

|

Net debt |

29.1 |

29.2 |

24.8 |

24.6 |

24.5 |

|

Budget balance by government level1 |

|||||

|

Federal |

0.3 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

|

Provincial, territorial, local, aboriginal |

-1.0 |

-1.2 |

-1.0 |

-1.3 |

-1.3 |

|

Canada/Québec Pension Plans |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

1. Government Financial Statistics.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 385-0032 and OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook 103 database.

Table 3. Federal government medium-term budget outlook1

As a percentage of GDP

|

2016-17 |

2017-18 |

2018-19 |

2019-20 |

2020-21 |

2021-22 |

2022-23 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Budget revenues |

14.4 |

14.5 |

14.5 |

14.5 |

14.5 |

14.6 |

14.5 |

|

Programme expenses |

14.1 |

14.2 |

14.0 |

13.9 |

13.8 |

13.7 |

13.6 |

|

Public debt charges |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

Budget balance |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.7 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

|

Federal debt |

31.0 |

30.4 |

30.1 |

29.8 |

29.4 |

28.9 |

28.4 |

1. Fiscal years end 31 March.

Source: Finance Canada, Budget 2018.

Provincial governments should establish budget agencies to provide independent analyses, as recommended in the last Survey (Table 4). In addition, they should strengthen their fiscal rules to target their overall and not just their operational balances, to establish a clear link between deficit and debt targets (IMF, 2017[6]). Estimates of the fiscal impact of the recommendations in this Survey are given in Box 1.

Table 4. Past OECD recommendations on fiscal policy

|

Recommendations in past Surveys |

Actions taken since the previous Survey |

|---|---|

|

Strengthen the fiscal framework by adopting a medium-term debt-to-GDP target, taking into account the outlook for provincial/territorial debt, to ensure that general government finances are sustainable, as well as the associated multi-year budgeting and spending ceilings. |

The federal government has committed to reducing the federal debt-to-GDP ratio over a five-year period but has not specified targets. It has also noted that it remains committed to eventually returning to balanced budgets without providing a timeframe. |

|

Establish provincial budget agencies, as in Ontario, or, better still, an agency reporting to the Council of the Federation that provide(s) independent analysis of fiscal forecasts and cost estimates for policy proposals. |

No action taken. |

Box 1. Quantifying this Survey’s fiscal recommendations

The estimates in Table 5 are based on data from publicly available sources. They quantify the approximate net general government budgetary impact of recommendations in this Survey. Some recommendations (such as reducing marginal effective tax rates for Guaranteed Income Supplement recipients) are not quantifiable without further specific design decisions, and others (such as consolidation of labour market information) are already funded or primarily involve simplification of existing arrangements.

Table 5. Potential annual long-term fiscal effect of OECD recommendations

|

% of GDP |

CAD billion per year |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Increase funding for active labour market policies |

-0.12 |

-2.7 |

|

Further increase childcare funding |

Net long-term cost much smaller than the short-term outlay |

|

|

Increase the age of eligibility for public pensions |

0.15 |

3.4 |

Note: Calculated based on fiscal year 2018-19 GDP projections. Elimination of the preferential tax rate for small companies is at both the federal and provincial levels of government, excluding any dynamic effects due to changes in behaviour or economic growth. The increase in funding for active labour market policies is based on increasing spending per unemployed worker as a share of GDP per capita from 5.9% to 8.9%, halving the 11.8% gap with the OECD median. The net fiscal impact of increased childcare funding is based on outcomes in Québec, as documented in Fortin, Godbout and St-Cerny (2013[7]). There are likely to be significant short-term fiscal costs associated with increased childcare funding, with an estimated CAD 7.5 billion annually required nationally to operate childcare programmes with similar coverage to Québec’s (Fortin, 2018[8]). The fiscal impact of increasing the age of eligibility for public pensions is based on a one-year increase, using estimates from the Office of the Chief Actuary that exclude any dynamic effects on economic growth from people working longer (2016[9]).

NAFTA threats and US tax reform are weighing on the outlook

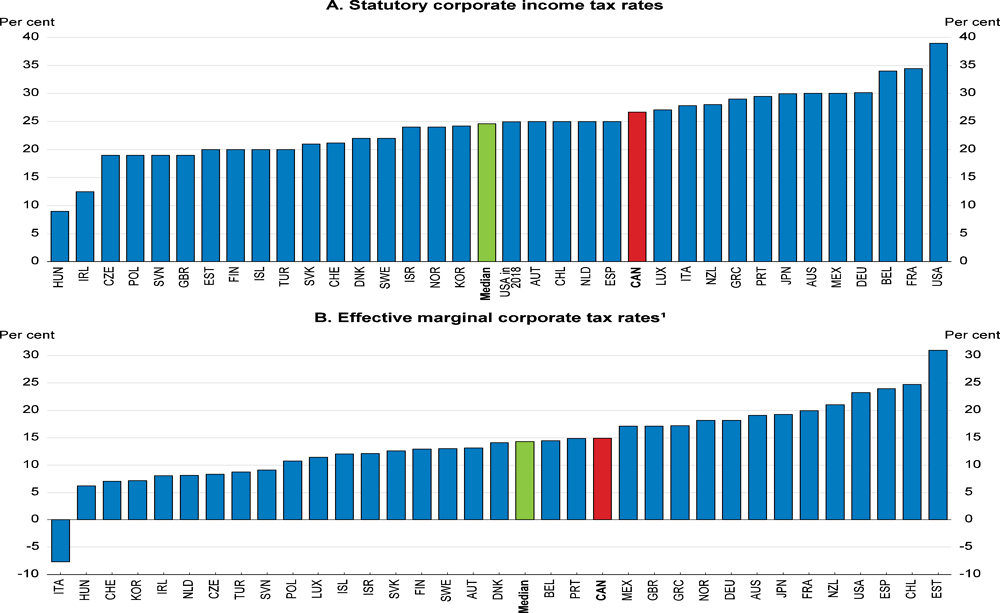

Uncertainty about the future of NAFTA and other aspects of US trade policy are weighing on the outlook and may be dampening the growth of business investment. The Bank of Canada (2018[10]) estimates that trade policy uncertainty could reduce the level of business investment and exports by 2.1% and 1.0%, respectively, by the end of 2020. The US corporate tax reform has also decreased the relative attractiveness of investing in Canada, reinforcing the negative effects of NAFTA uncertainty. Canada’s nominal and marginal effective corporate tax rates were substantially lower than those in the United States, but this advantage has now effectively disappeared (Figure 10); Finance Canada estimates that the post-reform US marginal effective tax rate (including sales taxes) is 19.2%, slightly above the Canadian rate of 17.6%. The Bank of Canada (2018[10]) estimates that the US tax cut will reduce business investment in Canada by 0.9% by the end of 2020. The government should review the tax system to ensure that it remains efficient -- raising sufficient revenues to fund public spending without imposing excessive costs on the economy -- equitable and supports the competitiveness of the Canadian economy.

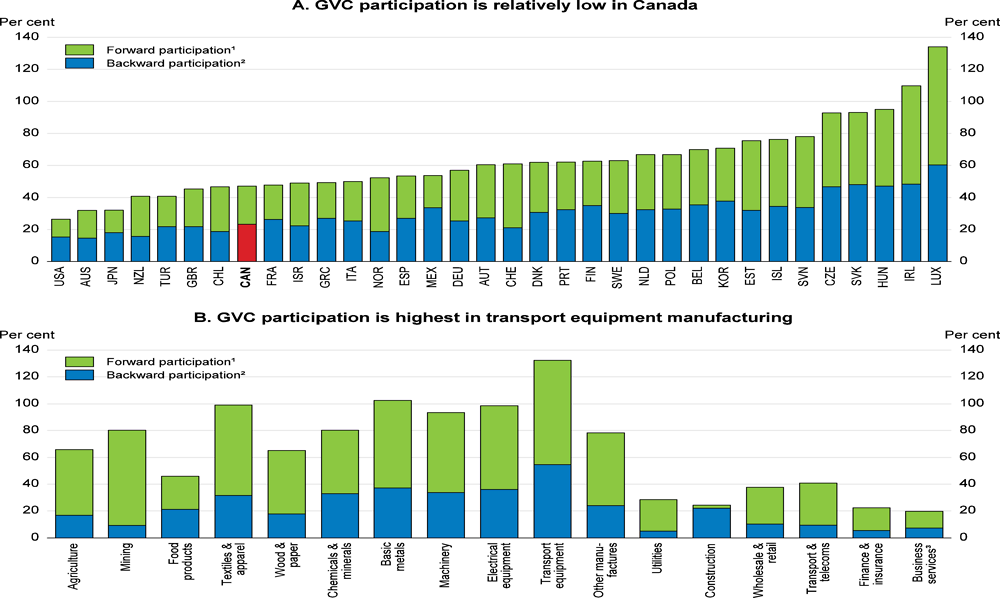

Figure 10. Corporate income tax rates, 2017

1. The effective marginal corporate tax rate is the percentage increase in the cost of capital of a marginal investment - that is, an investment that pays just enough to make the investment worthwhile - as a result of the corporate income tax rate and tax base. This measure does not include sales taxes.

Source: OECD, Tax database; Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, CBT tax database.

Canada has benefited greatly from openness to international trade, which increases incomes and well-being through the increased productivity that results from greater scale and production specialisation, and more diverse consumer choice. For example, NAFTA has contributed to the development of cross-border supply chains, typified by those in the automotive manufacturing industry. Canada’s participation in such regional or global value chains is more limited than in strongly interconnected European and Asian countries but has expanded recently and is notably higher in some sectors, such as transport equipment (Figure 11). Participation in such value chains extends and diversifies potential export markets, fosters investment, increases competitive pressures and entails technological, skill and managerial spillovers. To the extent that deeper integration in value chains spurs innovation, it is also likely to contribute to upward social mobility (Aghion et al., 2015[11]). If NAFTA were to be terminated, potential losses are estimated to amount to around 0.5% of GDP in the short term and 0.2% of GDP in the long term, when displaced labour and capital will have been reallocated (Box 2). There is considerable uncertainty around these estimates, and effects could be larger if services trade is impeded. The spectre of permanently losing exemption from 25% US tariffs on imports of steel and 10% on aluminium would add to the costs if NAFTA renegotiation were to fail, as Canada is the biggest source country for US imports of both metals. Such trade was worth just over CAD 16 billion in 2017 (about 0.8% of GDP). On the other hand, the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership are positive developments that reflect the Canadian government’s efforts to further promote trade and will deliver long-term benefits to Canadians.

Figure 11. Global value chain (GVC) participation, 2014

1. Domestic value added embodied in foreign exports as a percentage of total gross exports.

2. Foreign value added embodied in exports as a percentage of total gross exports.

3. Real estate, renting and business activities.

Source: OECD-WTO, Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), http://oe.cd/tiva.

Box 2. Simulating the potential economic effects of NAFTA termination

Several institutions have modelled the economic impact of tariffs rising from those set under NAFTA (Table 6). There is considerable variation across different estimates, reflecting the use of different economic models and other analytical differences, with three key factors standing out:

Impacts are more severe in the short and medium term, when labour and capital markets are still adjusting and employment is lower than otherwise.

Studies that model increases in non-tariff barriers to trade, including barriers to trade in services, find substantially higher costs of termination.

Impacts are smaller where Canada chooses not to raise import tariffs, or where the United States–Canada Free Trade Agreement remains in force.

Adding to uncertainty, these studies exclude the loss of dynamic productivity growth benefits arising from the NAFTA agreement, for example from expansion of value chains across North America and increases in foreign direct investment. Canada’s participation in global value chains increased between 2011 and 2015 (Escobar, 2018 forthcoming[12]).

Table 6. Estimated impact of NAFTA termination on level of real GDP (%)

|

Initial impact (2018-19) |

Long-term impact |

|

|---|---|---|

|

CD Howe |

n/a |

-0.6 |

|

IMF |

-0.4 |

-0.1 |

|

Moody’s Analytics |

-0.7 |

-0.2 |

|

Oxford Economics |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

|

Rabobank |

Medium-term impact (to 2025) of -2.0 |

|

|

Scotiabank |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

Note: Researchers from the CD Howe Institute modelled a scenario where tariffs on trade between the United States, Canada and Mexico revert to WTO most-favoured-nation levels, as well as taking into account the impact of removing NAFTA provisions that ease services market access. The IMF modelled a scenario where the United States raises the average tariff on imports from Canada by 2.1 percentage points to the WTO most-favoured-nation level, with no retaliation from Canada. Moody’s Analytics modelled a scenario where trade between the United States and Mexico reverts to most-favoured-nation tariffs while trade between the United States and Canada is based on United States–Canada Free Trade Agreement rules. Oxford Economics modelled a scenario where tariffs on US trade with Canada and Mexico would rise in line with most-favoured-nation rules (an average tariff on US imports of 3.5%), while trade between Canada and Mexico continues under NAFTA rules. Rabobank modelled the same tariff increases as Oxford Economics, in conjunction with an increase in non-tariff barriers that roughly doubled the impact on Canada. Scotiabank modelled reversion to a 3.5% most-favoured-nation tariff on US imports from Canada and Mexico, with Canada and Mexico reciprocating with identical tariffs on NAFTA trade.

Economic growth is projected to remain solid

Economic growth is projected to ease from 3% in 2017 to around 2% in 2018-19 as private consumption and government spending slow, the former as interest rates rise further, house price appreciation slows and job growth eases (Table 7). Business investment will be supported by capacity constraints, high profitability and still low financing costs, but oil and gas exports will continue to be held back by pipeline capacity constraints until mid-2018. Infrastructure investment is set to rise this year and to remain at an elevated level thereafter, partly to make up for earlier delays in implementing the government’s 12-year CAD 187 billion programme. Export growth will be driven by strengthening global demand, notably from US fiscal stimulus and investment growth. Inflation may rise to slightly above the 2% target band mid-point and unemployment should fall somewhat.

Table 7. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2007 prices)

|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (CAD billion) |

||||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

1 990 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

3.0 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

|

Private consumption |

1 110 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

1.8 |

|

Government consumption |

404 |

1.6 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

1.8 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

487 |

-5.1 |

-3.0 |

2.8 |

4.2 |

3.2 |

|

Housing |

141 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

1.8 |

1.1 |

|

Business |

274 |

-11.0 |

-9.0 |

2.4 |

5.5 |

4.3 |

|

Government |

71 |

0.4 |

5.2 |

3.9 |

5.3 |

3.9 |

|

Final domestic demand |

2 001 |

0.3 |

1.1 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

2.1 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

9 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

0.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

2 010 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

3.8 |

2.7 |

2.1 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

628 |

3.5 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.7 |

4.4 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

647 |

0.7 |

-1.0 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.9 |

|

Net exports1 |

- 20 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

-0.9 |

-0.7 |

0.1 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

||||||

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

2.0 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

|

Output gap2 |

. . |

-1.9 |

-2.2 |

-0.8 |

-0.3 |

0.4 |

|

Employment |

. . |

0.9 |

0.7 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

|

Working-age population (15-74) |

0.8 |

1.1 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

|

Unemployment rate3 |

. . |

6.9 |

7.0 |

6.3 |

5.7 |

5.5 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

-0.8 |

0.6 |

2.3 |

2.7 |

2.3 |

|

Consumer price index |

. . |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

|

Core consumer prices4 |

. . |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.6 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

|

Household saving ratio, net5 |

. . |

4.6 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

|

Terms of trade |

-6.9 |

-1.9 |

3.0 |

2.1 |

0.1 |

|

|

Trade balance6,7 |

. . |

-2.5 |

-2.4 |

-2.3 |

-2.2 |

-2.1 |

|

Current account balance6 |

. . |

-3.6 |

-3.2 |

-3.0 |

-2.7 |

-2.5 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

2.1 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

2.5 |

3.6 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. As a percentage of the labour force.

4. Consumer price index excluding food and energy.

5. As a percentage of household disposable income.

6. As a percentage of GDP.

7. Goods and services.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook 103 database.

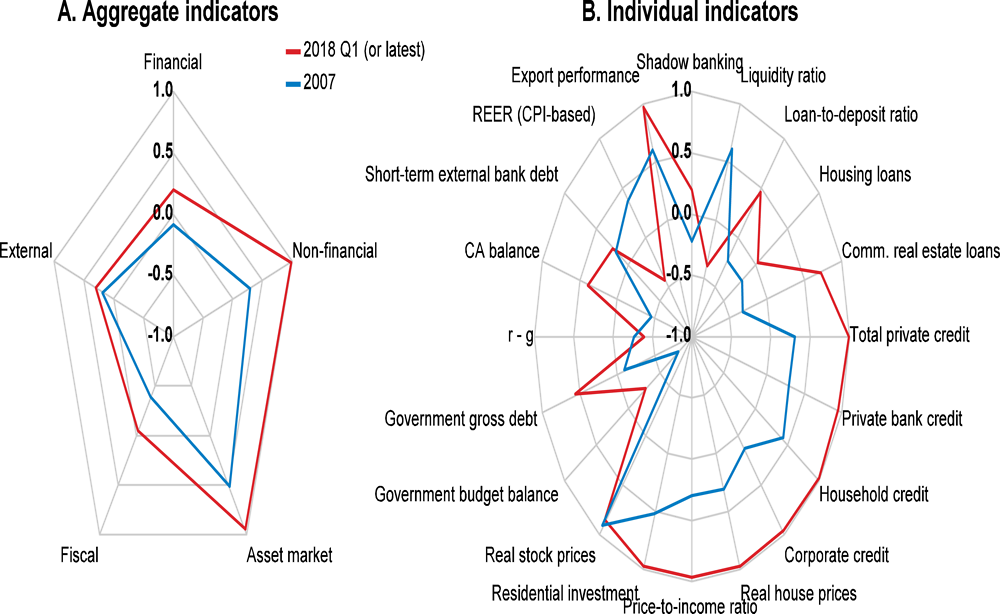

Major risks to the projection concern increases in restrictions on global trade and a disorderly housing market correction (see below). Macro-financial vulnerabilities are substantially higher than at the end of the last expansion, as rapid appreciation in house prices and the associated expansion in household debt has created substantial financial, non-financial and asset-market risks (Figure 12). Fiscal vulnerabilities remain close to their long-term averages but have increased relative to 2007 due to an increase in government debt. The greatest uncertainty concerns trade restrictions, with Canada exposed to the fallout from increased tariffs on imports into the United States and retaliatory measures elsewhere. Investment intentions surveys indicate that this uncertainty is already constraining Canadian investment. There would be further negative implications for growth if NAFTA were terminated (Table 8) or alternatively a boost to investment if uncertainty were resolved under similar or increased market access. Faster growth is also possible if private consumption or residential investment growth do not slow as much as anticipated or if a stronger synchronised global upturn pulls up investment and exports.

Figure 12. Evolution of macro-financial vulnerabilities

Index scale of -1 to 1 from lowest to greatest potential vulnerability, where 0 refers to long-term average, calculated for the period since 1970¹

1. Each aggregate macro-financial vulnerability dimension is calculated by aggregating (simple average) normalised individual indicators from the OECD Resilience database. The financial dimension includes: shadow banking (% of GDP), the liquidity ratio, the loan-to-deposit ratio, housing loans and commercial real estate loans. The non-financial dimension includes: total private credit, private bank credit, household credit and corporate credit (all in % of GDP). The asset market dimension includes: real house prices, price-to-income ratio, residential investment (% of GDP) and real stock prices. The fiscal dimension includes: the government budget balance (% of GDP), government gross debt (% of GDP) and real bond yield minus potential growth rate (r-g). The external dimension includes: the current account balance (% of GDP), short-term external bank debt (% of GDP), the real effective exchange rate (REER) and export performance. Most financial data start in 2005.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2018), OECD Resilience database, May.

Table 8. Possible shocks affecting the Canadian economy

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Housing market correction |

A housing market correction would reduce residential investment, household wealth and consumption, with Canada’s high level of residential investment amplifying the potential impact. A sufficiently large shock could even threaten financial stability. Fiscal costs from government-backed housing insurance would arise only under very large price falls with widespread defaults, as insurers hold substantial capital reserves. The IMF (2017[6]) has estimated that a 30% decline in house prices initiated by tighter global financial conditions would have a negative effect on GDP of around 3% in the short term, with consumption 3.5% lower due to wealth effects and investment 18% lower. Such a large decline would need to be triggered by developments external to the housing market, such as substantial increases in unemployment or interest rates. |

|

Increased global trade restrictions |

As a small, open economy, Canada is highly exposed to increases in trade restrictions, particularly barriers to trade with its major trading partner, the United States. An increase in trade restrictions would slow Canadian growth through dampening exports and investment, with larger effects if a global trade war reduced economic growth among key trading partners. A number of modelling exercises indicate that Canadian GDP could be around 0.5% lower if NAFTA were terminated, but with considerable uncertainty (Box 2 above). Negative effects would be concentrated in industries with supply chains that are integrated across North America, such as automotive manufacturing. Business services could also face substantial losses due to their importance as intermediate inputs, which would be exacerbated if NAFTA provisions easing services market access were removed (Ciuriak et al., 2017[13]). |

|

Disorderly financial asset price deflation with normalisation of monetary policy |

Excess liquidity has driven up global prices for financial assets, cutting yields to historically low levels. Monetary policy normalisation will see short-term interest rates and term premia rise; increasing US budget deficits are also likely to push up term premia If the scale of monetary tightening needed to contain inflation is greater than expected, there could be sharp falls in asset prices, which would depress economic growth through lower business investment and private consumption. |

The housing boom

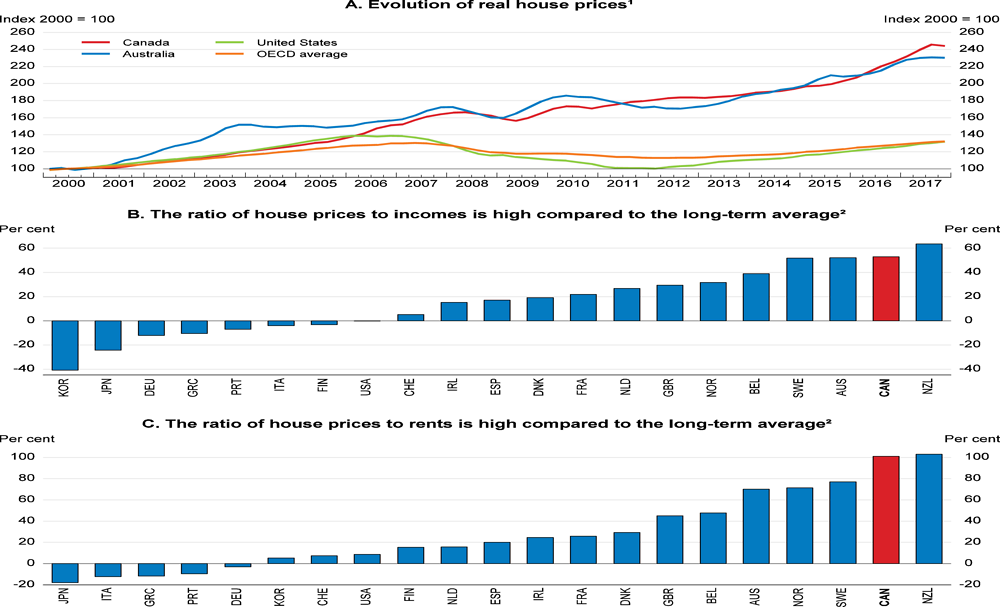

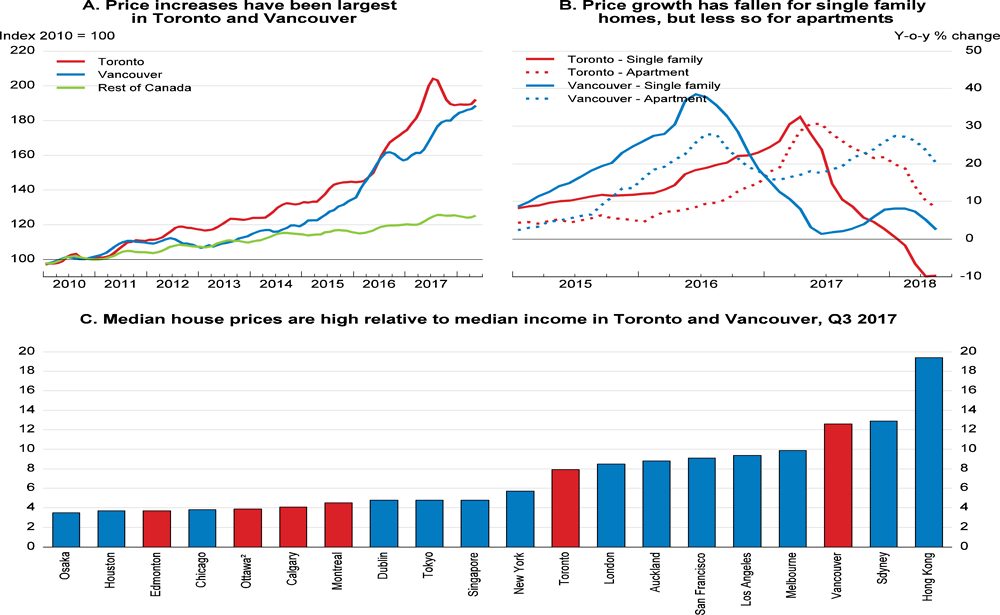

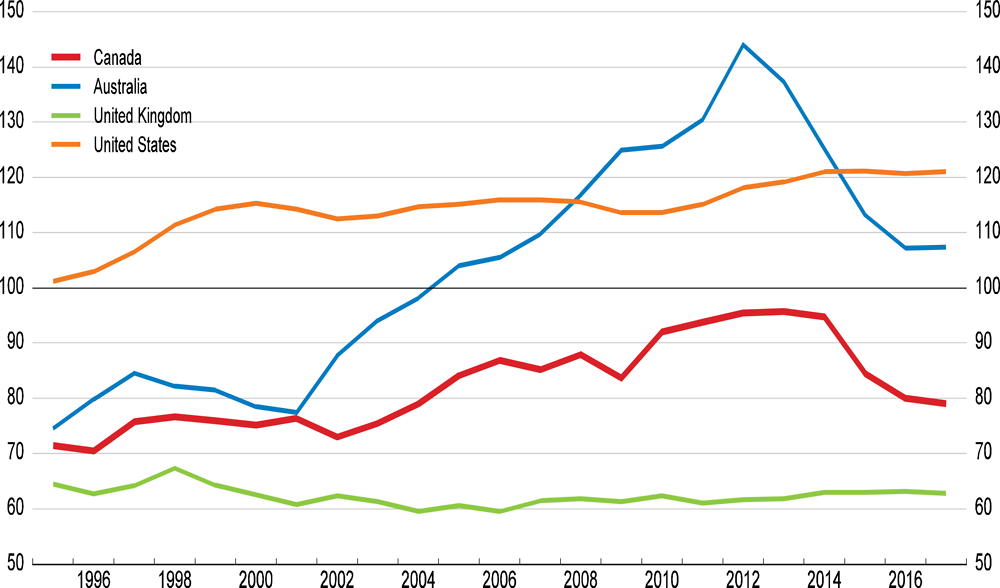

Canadian house prices have more than doubled in real terms since 2000, outpacing incomes and rents (Figure 13). Concerns around house price increases are concentrated on the Toronto and Vancouver markets (Figure 14). They are considered to be highly overvalued by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), and price pressures have spilled over to the neighbouring markets of Victoria (British Columbia) and southern Ontario. Provincial governments have responded with policy measures to ease housing market pressures, notably the introduction of foreign buyers’ transaction taxes for purchases in Vancouver (August 2016; rate raised and expanded geographically in February 2018) and Toronto (as part of the Ontario Fair Housing Plan, announced in April 2017). In each case these measures were followed by a period of weaker price appreciation. While this is a positive sign of market stabilisation, the resumption of price growth in Vancouver in 2017 raises the possibility that cooling in Toronto might also be temporary. National average house price growth was 4.5% in the year to May 2018, well down from the peak of over 14% in mid-2017 (Teranet and National Bank of Canada, 2018[18]).

Increasing demand has been a key driver of price growth, including speculative activity in the expectation of further gains. The CMHC estimates that demand-side factors such as low interest rates, higher incomes and population growth (primarily due to immigration) can explain 75% of Vancouver’s price increases between 2010 and 2016, but only 40% of Toronto’s. Foreign buying has also supported demand, notably in Vancouver, where in 2017 non-residents owned 4.8% of residential properties (3.4% in Toronto) (Gellatly and Morissette, 2017[19]).

Figure 13. House prices have grown rapidly relative to fundamental drivers

1. Nominal house prices deflated by the private consumption deflator.

2. Deviation of the latest observation Q4 2017 from the long-term average. The long-term average starts in Q1 1980 for most countries, with a few exceptions. The price-to-income ratio starts in Q1 1981 for Denmark, Q1 1986 for Korea and New Zealand, Q1 1987 for the United Kingdom, Q1 1995 for Portugal and Q1 1997 for Greece. The price-to-rent ratio begins in Q1 1986 for Korea, Q1 1988 for Portugal and Q1 1997 for Greece.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook database.

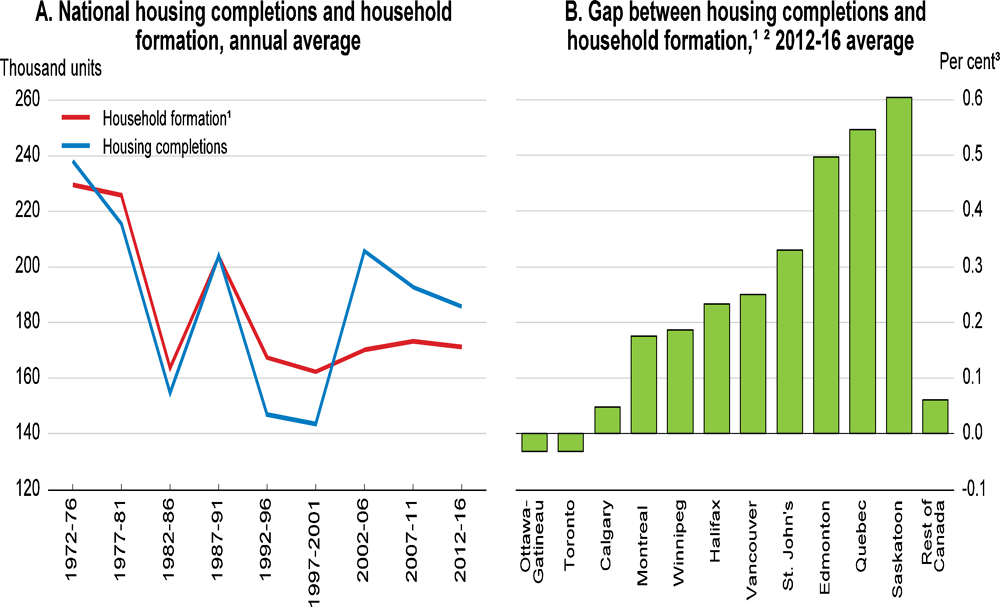

Housing supply responses have been weak in some large urban centres (Figure 15). In Toronto, housing completions have struggled to keep pace with household formation, the number of completed but unsold units has declined to one of the lowest levels ever recorded, and the condominium apartment vacancy rate is only 0.7% (CMHC, 2018[20]). Relatively weak supply responses to price increases in Toronto and Vancouver, due to regulatory and physical constraints, meant that large price increases were needed to balance demand and supply, contributing to speculative activity by fuelling expectations of future price growth (CMHC, 2018[21]). Conversely, the stock of completed yet unsold units is at or above thresholds used to determine overbuilding in Calgary, Edmonton, Saskatoon and Regina (CMHC, 2018[20]).

Figure 14. House prices are particularly high in Toronto and Vancouver

1. Includes Gatineau.

Source: Teranet and National Bank of Canada, House Price Index; Canadian Real Estate Association, MLS Home Price Index; Demographia (2018), 14th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2018.

Related high household debt is an important economic vulnerability

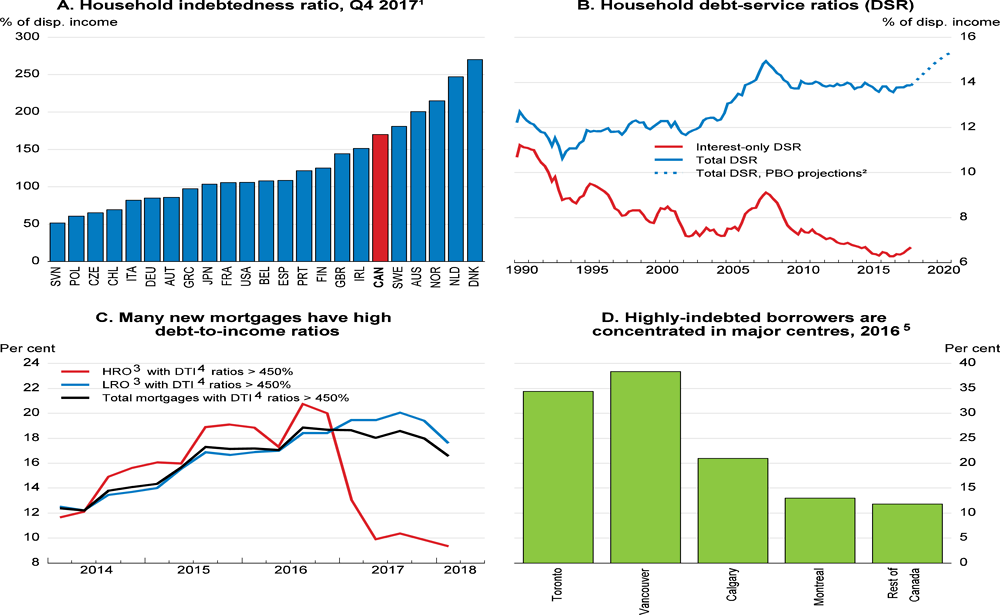

Household debt has reached 170% of disposable income, high by international comparison (Figure 15, Panel A) and up from 100% two decades ago. High debt makes households more vulnerable to external shocks such as increases in interest rates or unemployment. The Bank of Canada has identified elevated household indebtedness as the most important vulnerability for the Canadian financial system (Bank of Canada, 2017[22]). Debt-servicing costs have been held down by low interest rates but could reach levels not seen since at least 1990 with policy rate normalisation (Panel B). While most mortgages are issued on a recourse basis, vulnerability is heightened by mortgage rates that are rarely locked in for more than five years. Only 22% of loans with major banks will not face an interest rate reset for three years or more (Bank of Canada, 2017[22]). Banks are well-capitalised and protected by mostly public mortgage insurance, which covers more than half of outstanding mortgage debt, but this pushes substantial risk back onto the taxpayer: government-backed insurance coverage amounted to 36% of GDP in 2015 (Finance Canada, 2016[23]). The 2014 Survey first recommended reducing government exposure and moral hazard by tightening mortgage insurance to cover only part of lenders’ losses (Table 9). The prevalence of mortgage insurance has declined recently, with over 80% of new mortgages in 2017 not requiring it, partly because more homes now exceed the CAD 1 million limit for government-backed insurance.

Figure 15. Housing construction has exceeded demand recently, but with considerable geographic variation

1. Household formation adjusted for 2016 Census undercount based on preliminary national undercount applied pro rata to estimates of undercount by Central Metropolitan Areas from the 2011 Census.

2. Household formation in Saskatoon, St John's, Québec City and Montreal adjusted for revised 2011 Census population estimates.

3. As a percentage of private dwellings in 2011.

Source: Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (2017), Household Formation and the Housing Stock, May 2017 Update, Figure 2.1; Statistics Canada, Table 027-0049 and 2011(/2016) Census; OECD calculations.

New mortgage holders in markets that have experienced strong price growth are particularly vulnerable. Many new mortgage holders -- especially in Toronto and Vancouver -- have loan-to-income ratios exceeding 350 or even 450% (Figure 16, Panels C and D), at which level the rate of arrears arising from a negative economic shock is more than ten times that for mortgagees with debt-to-income in the 100-250% range (Cateau, Roberts and Zhou, 2015[24]). Aggregate household debt is concentrated among middle-income groups. For recent mortgages with a loan-to-value ratio of no more than 80% the share with a high loan-to-income ratio is greatest among borrowers with lower incomes (Bank of Canada, 2017[22]).

Figure 16. Household debt levels are high, particularly so among some new borrowers

1. Total household outstanding debt as a percentage of household gross disposable income. Q1 2016 for Japan, Q1 2017 for Norway and the United Kingdom, Q3 2017 for Austria, Chile, Czech Republic and Poland.

2. PBO projections for the debt service ratio have been adjusted down by 0.86 percentage points to reflect a change in the starting point for projections following revisions to historical data and new data available up to the first quarter of 2018.

3. High-ratio originations (HROs) are new mortgages with a down payment of less than 20%, for which mortgage insurance is mandatory. Low-ratio originations (LROs) are new mortgages with a down payment of 20% or more.

4. Debt-to-income ratio.

5. Share of new low-ratio loans with debt-to-income ratio above 450%.

Source: OECD, National Accounts - Household Dashboard database; Statistics Canada, Table 380-0073; Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (2017), Household Indebtedness and Financial Vulnerability, Chart 1; Bank of Canada (2018), Financial System Review, June, Chart 4.

Macro-prudential measures have mitigated risks

A series of macro-prudential measures adopted since 2008 have sought to lower housing-market risks. The most important of these for insured loans were tightening loan-to-value caps (from 100 to 95% for the first CAD 500 000 and 90% for the next CAD 500 000 of new mortgages, and from 95 to 80% for refinancing), with a debt-servicing “stress test” against a standardised rate (Table 9). The household debt-to-income ratio could have been close to 200% as of late 2016 (rather than the actual 167%) without these measures (Krznar, Arvai and Ustyugova, 2017[25]). Since 1 January 2018, banks have also been required to stress test debt servicing for uninsured mortgages. It is too early to tell how much this change will lower the incidence of highly indebted uninsured borrowers, as has already occurred for new borrowers with a down payment of less than 20% who must purchase insurance.

Table 9. Past OECD recommendations on addressing housing-market challenges

|

Recommendations in past Surveys |

Actions taken since the previous Survey |

|---|---|

|

Continue to tighten macro-prudential measures, and target them regionally, including through increasing capital requirements in regions with high house price-to-income ratios. |

From October 2016 the Minister of Finance required all insured borrowers to qualify under maximum debt-servicing standards based on a “stress test” against the higher of the contracted mortgage rate or benchmark five-year fixed mortgage rate published by the Bank of Canada. Previously this requirement had applied only to variable-rate mortgages and those with terms of less than five years. In January 2018 the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions set a new minimum qualifying rate stress test for uninsured mortgages based on the greater of the five-year benchmark rate published by the Bank of Canada or the contracted mortgage rate plus 2%. Federally regulated financial institutions are also required to establish and adhere to lower loan-to-value ratio limits in markets where prices have escalated to high levels relative to fundamentals. |

|

Tighten mortgage insurance to cover only part of lenders’ losses in case of default. Keep increasing the private-sector share of the market by gradually reducing the cap on the CMHC’s insured mortgages. |

No action taken. CMHC’s share of the mortgage insurance market has declined from about 65% in 2014 to less than half. |

|

Expand affordable municipal rental housing supply and densification by adjusting zoning regulations to promote more multi-unit dwellings. |

The 2018 Homes for British Columbia programme includes plans to work closely with municipal governments to eliminate barriers to affordable housing and develop new tools, such as rental zoning. |

|

Monitor the unregulated mortgage-lending sector more closely to improve understanding of risk exposures. Increase cooperation and information sharing between federal and provincial financial regulators. |

Canadian authorities are continuously monitoring shadow-banking entities, including through their participation in the Financial Stability Board's information-sharing exercises. |

|

Continue efforts to legalise and encourage secondary suites and laneway housing in single-family residential zones. Remove property-tax-rate differentials that disadvantage multi-unit rental properties relative to owner-occupied housing. |

The Ontario Planning Act requires municipalities to allow for secondary suites within single-detached, semi-detached and townhouse dwellings, and the Ontario Building Code was revised in 2017 to reduce the cost of construction of new two-unit homes. The City of Ottawa passed legislation to allow construction of secondary dwellings, and the City of Toronto held consultations on laneway housing proposals in late 2017. |

|

In areas of rapid house price appreciation, increase incentives for private-sector development of rental housing in appropriate areas through tools such as development charge waivers, reduced parking requirements and expedited permit processing. |

Some cities, including Edmonton and Ottawa, have reduced minimum parking requirements for urban development. |

The government should monitor the effects of recent macro-prudential tightening, especially the prevalence of highly indebted, low-income borrowers, and stand ready to act if circumstances change. Should rapid house-price appreciation resume, further tightening may be needed. Moreover, the higher loan-to-value limit for the share of insured loans below CAD 500 000 is not directly related to the riskiness of the loan and should be brought into line with the limit for the portion above CAD 500 000 by adjusting one or both thresholds. As noted by the IMF (2017[6]), close coordination between federal and provincial authorities is also critical: provincially regulated financial institutions should be encouraged to adhere to federal mortgage underwriting standards, and monitoring of systemic risks in, and linkages with, securities markets and provincially regulated institutions is needed.

Shortages of affordable housing raise inclusiveness issues

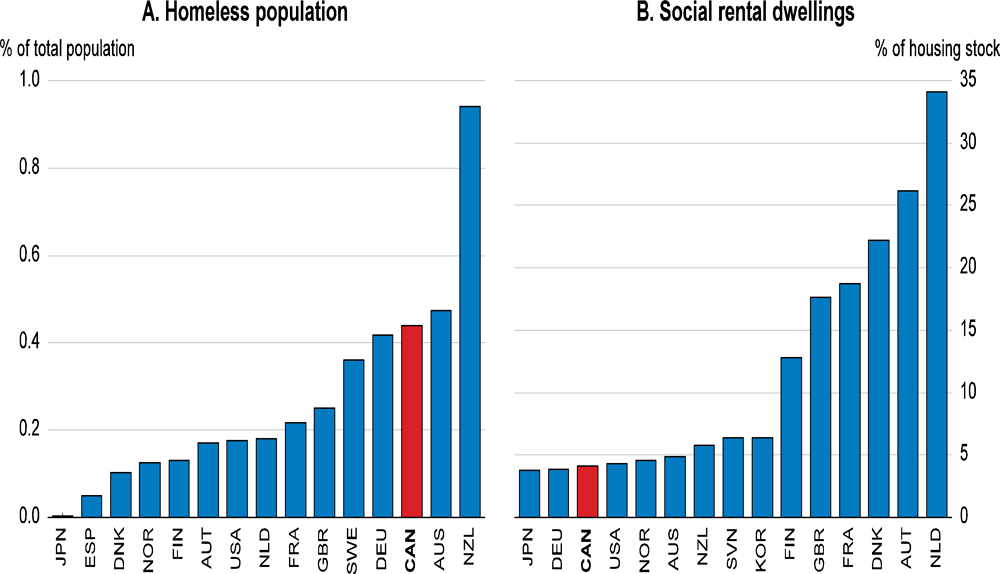

Housing affordability has worsened steadily since 2009 (Bank of Canada, 2018[26]). Compared with homeowners, a greater share of renters spend 30% or more of their income on housing, and rents have increased by 8% in real terms over the past decade (CMHC, 2017[27]). Canadians spend more of their disposable income on housing than residents of most OECD countries (OECD, 2017[28]). As of 2016, 1.7 million or 12.7% of households were estimated to be in “core housing need” (Statistics Canada and CMHC, 2017[29]). As described in the 2014 Survey, the lack of affordable housing creates serious challenges for low-income households, particularly those living in the major cities that have seen the greatest increases in house prices and rents.

Government programmes to assist with housing needs form a complex and often confusing patchwork, with most falling under either social or affordable housing (Office of the Auditor General of Ontario, 2017[30]). Social housing has not expanded significantly since the early 1990s, and much of the stock is ageing and needs repair and maintenance (Figure 17). Rents are set at a fixed share (generally close to 30%) of income, which represents a generous subsidy for those in urban areas with high rents. These factors have led to severe shortages in major centres, with a predicted queue of up to 14 years for recent applicants in high-demand Ontario locations (ONPHA, 2016[31]). Joint federal-provincial affordable-housing programmes aim to support low-income households through measures including grants for the construction of affordable rental units and rent subsidies. Affordable housing has been the major focus of initiatives in recent years, for example in Ontario where there are a number of programmes aimed at improving housing availability and affordability. The National Housing Strategy, launched in November 2017, provides CAD 40 billion over 10 years to construct 100 000 new housing units, repair 300 000 existing units, enhance rental-construction financing and provide housing allowances to needy households.

Figure 17. Homelessness is high and social housing stocks are low

2015 or latest year available

Source: OECD, OECD Affordable Housing database, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

This Strategy is projected to help up to 530 000 Canadians, but inequity between those with access to social housing and those without will continue. Construction of new units under the plan will be insufficient to eliminate waiting lists. Periodically reviewing tenure in social housing based on income would ensure that social housing goes to those who need it most, as would prioritising placement of applicants with the greatest needs in Ontario (where, apart from victims of domestic abuse, social housing is provided on a first-come first-served basis). New rental allowances should be based on a norm and not actual rent (coupled with minimum housing standards) to avoid overspending and should take into account implications for labour-force participation.

Fiscal sustainability

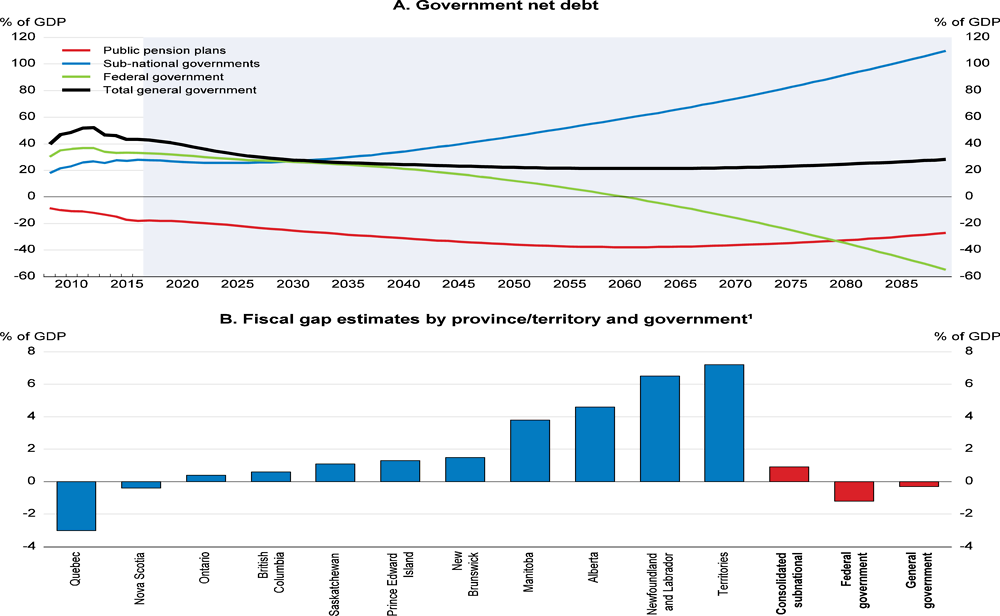

Fiscal policies are sustainable overall, but not for all levels of government

The Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) (2017[32]) estimates that, for all levels of government combined, Canada’s fiscal policies are sustainable for at least several decades – on current policies, government net debt is projected to decline somewhat relative to GDP over the next four decades and then to rise slowly but remain below the current level (Figure 18, Panel A). This means that significant changes in tax or expenditure levels relative to GDP are not needed for long-term debt sustainability – tax levels are slightly higher than needed to finance expenditure and hold the debt-to-GDP ratio unchanged over the long run: the overall fiscal gap is minus 0.3% of GDP (Panel B). Having sustainable fiscal policies may increase economic efficiency by smoothing taxes and/or the marginal benefit cut-offs for government expenditure over time.

However, overall sustainability reflects continuously declining net debt as a share of GDP at the federal level and ever rising debt at the provincial/territorial level. The federal fiscal gap is -1.2% of GDP while the consolidated provincial/territorial gap is 0.9% of GDP; taking into account Ontario’s expansionary FY 2018-19 budget, which was released after these projections, the sub-national government fiscal gap would now be around 0.3% of GDP higher. Fiscal gaps range from -3% of GDP in Québec, where the government is cutting its high net debt-to-GDP ratio (Table 10), to 6.5% of GDP in Newfoundland-Labrador, which, like Alberta, is having to adjust to the post-2014 decline in oil prices.

One cause of provinces’ difficulties is rising health-care costs, even when, as in these projections, excess cost growth (i.e., growth exceeding the sum of nominal GDP growth and that due to population ageing) is assumed to be zero; it averaged 0.3 percentage point per year over 1982-2015. In this projection, health-care costs rise as a share of GDP because of population ageing. Provinces with the largest increase in the old-age dependency ratio will also experience the largest declines in the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) from the federal government as a share of health-care costs (Table 11). This is because the CHT, like other federal transfers, is not adjusted for provinces’ age structures, contrary to recommendations in past Surveys (Table 12). However, age is only one factor, albeit an important one, that influences a province’s need or ability to provide services. To help provincial and territorial governments support home care and mental health, the federal government confirmed an allocation of CAD 11 billion over 10 years to this end in the 2017 budget.

The PBO (2018[33]) estimates that if the CHT were to grow in line with projected health expenditure in each province and the territories (combined), the federal fiscal gap would deteriorate by 0.3 percentage point and the sub-national fiscal gap would improve by the same amount. Across provinces and territories the improvement would range from 0.1 percentage point in British Columbia to 0.7 percentage point in Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island. In this scenario, the federal government would continue to have a substantial negative fiscal gap (taxes are higher than needed to finance expenditures and stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio), while most sub-national governments would continue to have positive gaps, albeit smaller to varying degrees.

Figure 18. Government sector net debt and fiscal gap estimates over the long term

1. Fiscal gaps in 2016 for each province and the territories are expressed relative to their corresponding provincial/territorial GDP. The consolidated subnational fiscal gap is expressed relative to the national GDP.

Source: Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (2017), Fiscal Sustainability Report 2017, Summary Figures 1 & 2, http://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/files/files/FSR_2015_EN.pdf.

Table 10. Provincial government long-term baseline scenario

|

|

Health expenditure |

Primary balance |

Net debt |

Canada Health Transfer |

Senior dependency ratio |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% of GDP |

% health expenditure |

% population 65+/15-64 |

|||||||||||||

|

2016 |

2091 |

Change |

2016 |

2091 |

Change |

2016 |

2091 |

Change |

2016 |

2091 |

Change |

2016 |

2091 |

Change |

|

|

NL |

9.3 |

15.7 |

6.4 |

-4.5 |

-7.9 |

-3.4 |

36.6 |

1293.1 |

1256.5 |

18.6 |

9.3 |

-9.3 |

28.6 |

75.3 |

46.7 |

|

NS |

10.0 |

15.4 |

5.4 |

4.0 |

-0.5 |

-4.4 |

28.4 |

-34.5 |

-62.9 |

23 |

16.7 |

-6.3 |

29.2 |

63.5 |

34.3 |

|

PE |

10.3 |

15.3 |

5.1 |

1.3 |

-4.0 |

-5.3 |

33.3 |

169.5 |

136.2 |

22.4 |

14.3 |

-8.1 |

28.9 |

56.9 |

28.0 |

|

NB |

9.3 |

14.1 |

4.8 |

-0.7 |

-1.0 |

-0.3 |

37.8 |

276.2 |

238.4 |

23.9 |

18.2 |

-5.7 |

29.7 |

63.9 |

34.2 |

|

QC |

8.2 |

11.1 |

2.8 |

3.8 |

4.9 |

1.1 |

47.1 |

-368.0 |

-415.1 |

25.6 |

23.0 |

-2.6 |

27.2 |

48.3 |

21.1 |

|

ON |

6.9 |

9.4 |

2.5 |

0.7 |

-0.9 |

-1.6 |

36.4 |

83.5 |

47.1 |

25.2 |

17.6 |

-7.6 |

24.2 |

48.1 |

23.9 |

|

MB |

9.3 |

11.7 |

2.3 |

-0.7 |

-5.8 |

-5.2 |

35.4 |

385.2 |

349.8 |

20.7 |

14.4 |

-6.3 |

22.7 |

40.6 |

17.9 |

|

SK |

7.2 |

8.3 |

1.0 |

-2.7 |

-1.5 |

1.3 |

11.1 |

119.1 |

108.0 |

20.7 |

15.0 |

-5.7 |

22.5 |

44.8 |

22.3 |

|

AB |

6.9 |

8.8 |

1.9 |

-5.6 |

-5.1 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

323.3 |

322.2 |

20.1 |

15.4 |

-4.7 |

17.1 |

36.4 |

19.3 |

|

BC |

7.4 |

9.1 |

1.7 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

-0.5 |

7.4 |

73.3 |

65.9 |

24.2 |

24.3 |

0.1 |

26.5 |

47.8 |

21.3 |

Source: Office of the Parliamentary Budgetary Officer (2017), Fiscal Sustainability Report 2017, Ottawa; OECD calculations.

Table 11. Factors related to differences in long-term spending pressures across provinces

Correlation coefficients

|

|

Health expenditure % of GDP |

Senior dependency ratio |

CHT share of health expenditure |

Primary balance % of GDP |

Fiscal gap % of 2016 GDP |

Net debt % of GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Health expenditure,% of GDP |

1.0 |

|||||

|

Senior dependency ratio |

0.9 |

1.0 |

||||

|

CHT share of health expenditure |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

1.0 |

|||

|

Primary balance, % of GDP |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

||

|

Fiscal gap, % of 2016 GDP |

0.2 |

0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

1.0 |

|

|

Net debt, % of GDP |

0.4 |

0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.3 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

Source: Office of the Parliamentary Budgetary Officer (2017), Fiscal Sustainability Report 2017, Ottawa; OECD calculations.

There also remains considerable scope to implement past Survey recommendations to reduce costs by boosting the health system’s efficiency (Table 12). Recent analysis of one of these recommendations – revising the core public health insurance scheme to include essential pharmaceuticals – suggests that there are substantial savings and equity gains to be made, albeit mainly to the benefit of households rather than governments (Box 3). The federal government recently announced the creation of an Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare and the Ontario government announced that its youth pharmacare plan would be extended to seniors from August 2019. The federal government is also working with provincial governments through the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Association to negotiate lower prices on prescription drugs.

Concerning the remaining part of general government - the funded second-pillar public pension schemes (Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Québec Pension Plan (QPP)) - PBO (2017[32]) provides a number of sensitivity analyses that support the qualitative conclusion that they are sustainable (Figure 18, Panel A). One risk not analysed in PBO (2017[32]) is that returns on equities, which account for 85% of the benchmark risk-parity portfolio, may be lower than assumed, given current high valuations. If equity returns were to be 0.75 percentage point lower, there would be a deficit of 0.1% of GDP (equivalent to 4.3% of annual contributions). That said, the Chief Actuary has done extensive sensitivity analysis of the rate of return used to assess the sustainability of the CPP over the next 75 years.

Table 12. Past OECD recommendations on federal transfers to provinces and health care

|

Recommendations in past Surveys |

Actions taken since the previous Survey |

|---|---|

|

Factor in interprovincial differences in age structure when calculating federal transfers to provinces. |

No action taken. |

|

Eliminate zero patient cost sharing for core services by imposing co-payments and deductibles. |

No action taken. |

|

Clarify the Canada Health Act to facilitate private entry in hospital services and mixed public/private physician contracts. |

No action taken. |

|

Replace historical-based cost budgeting of Regional Health Authorities (RHAs) with a formula-based approach. |

No action taken. |

|

Devolve integrated budgets for hospital, physician and pharmaceutical services to RHAs. |

No action taken. |

|

Increase the use of capitation or salary for physician compensation, and have RHAs regulate fees. |

No action taken. |

|

Move to activity-based budgets for hospital funding, contracting with private and public hospitals on an equal footing. Adjust overall budget caps up to reward efficiency. |

The three largest provinces (i.e. Ontario, Québec and British Columbia), representing over two-thirds of the population, have either implemented or announced future implementation of some activity-based hospital funding. |

|

Revise the public core package to include essential pharmaceuticals and eventually home care, selected therapy and nursing services. |

Since 1 January 2018, children and youth up to 24 years old in Ontario have free prescription drug coverage, regardless of family income. As part of federal budget 2018, the government announced the creation of an Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare. The Ontario government announced in its 2018 budget that its pharmacare plan, which currently benefits people aged 24 and under, will be extended to people aged 65 and over from August 2019. |

|

Regulate private health insurance (PHI) to prevent adverse selection, and remove tax exemptions for employer-provided private health-insurance benefits. |

No action taken. |

Box 3. Moving to a national pharmacare programme

Health-care costs could be reduced by extending access to publicly subsidised pharmaceuticals. Outside of Québec, public pharmacare programmes are limited to seniors and those on low incomes and, since January 2018 in Ontario, to children and youth. The Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (2017[34]) estimates that, had a universal national pharmacare programme been in place in FY 2015-16, the covered pharmaceutical expenses would have been CAD 4.2 billion (17%) lower (Table 13). Savings would have come predominantly from having a single purchaser and universal application of generic drug substitution; potential savings from moving from multiple administrators of drug benefit claims to a single administrator were not taken into account. Taking into account net co-payments and existing federal drug spending for certain populations and assuming that the Canada Health Transfer is reduced by provincial-territorial government savings, social security contributions would need to rise by CAD 8.0 billion to cover this federal expenditure. In this scenario all of the national savings would be allocated to households in the long run. Such a reform would also substantially reduce the proportion of Canadians (12%) unable to obtain necessary drugs because of their cost. The private-public pharmacare system in place in Québec also increased drug access but did not reduce taxpayer-financed drug expenditures and substantially increased expenditure by employers and households (Morgan et al., 2017[35]).

Table 13. Provincial government long-term baseline scenario

|

CAD billion, FY 2015-16 |

|

|---|---|

|

Eligible pharmaceutical expenditure |

24.6 |

|

of which |

|

|

Governments |

11.9 |

|

Private insurance plans |

9.0 |

|

Patients |

3.6 |

|

Same package, national pharma-plan |

20.4 |

|

National savings |

4.2 |

|

Federal cost of national pharma-plan |

|

|

Gross cost |

20.4 |

|

Existing programmes for selected groups |

0.6 |

|

Net co-payments |

0.4 |

|

Net cost |

19.3 |

|

less |

|

|

Provincial/Territorial savings |

11.3 |

|

Required increase in social security contributions |

8.0 |

|

Private-sector savings |

|

|

Private insurance plans |

9.0 |

|

Patients |

3.6 |

|

Net co-payments for the national programme |

-0.4 |

|

Increase in social security contributions |

-8.0 |

|

Total private-sector savings |

4.2 |

Source: Parliamentary Budgetary Officer (2017), Federal Cost of a National Pharmacare Program, Ottawa; OECD calculations.

Inclusiveness for women, youth and seniors

There is considerable scope to increase inclusiveness for women, youth and seniors through policy measures to improve their labour market outcomes (Chapter 1). Improving labour market inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in Canada is another way to boost labour force participation and well-being (Box 4).

Further steps are needed to narrow the gender wage gap

The total annual gender earnings gap among women who work full time, at 18% in 2016, is considerably larger than the OECD average, reflecting a large gender gap in hours worked, which in turn is partly attributable to Canadian women’s higher labour force participation rate than the OECD average (see Chapter 1). On an hourly basis, full-time working women earned 12% less than men. Around a third of the gap is estimated to reflect differences in observable characteristics such as education, occupation and industry of work (Schirle, 2015[36]). An important factor contributing to the wage gap is women’s under-representation in top-earning management and leadership positions, in part due to challenges faced by mothers in reconciling work and childcare responsibilities in jobs at the top of the earnings distribution (Fortin, Bell and Böhm, 2017[37]).

Providing better access to high-quality, affordable early childhood education and care (ECEC) is the best way to address the large gender wage gap and boost female labour participation. Just over half of the earnings penalty experienced by Canadian mothers can be explained by fewer years of work experience and more hours devoted to unpaid work (Vincent, 2013[42]). Québec’s experience with low-fee childcare is consistent with international evidence that affordable ECEC supports female participation, with one study finding this was sufficient to more than offset the upfront fiscal cost (Fortin, Godbout and St-Cerny, 2013[7]). ECEC is also important for child development: international studies, programme evaluations and quality measurements have repeatedly shown that access to ECEC programmes has positive effects on children’s well-being, learning and development (OECD, 2017[43]). The quality of care is critical, however, as low-quality ECEC can have detrimental effects on development and learning. Outcomes in Québec illustrate the importance of quality childcare, as high-quality public garderies improved cognitive and behavioural development even while behavioural development was dragged down by lower-quality care among some providers. Recent federal and provincial ECEC-boosting initiatives are promising, but even more needs to be done, with cross-country estimates indicating scope for a large lift to female employment from increasing ECEC spending to match that in leading OECD countries. Illustrative estimates of the long-term effects of this and other structural reforms discussed in this Survey on GDP per capita are shown in Box 5.

Box 4. Achieving labour force potential and improving the well-being of Indigenous Peoples

Socio-economic outcomes for Indigenous populations are worse on average than for other Canadians on a number of measures (Table 14). The extent of disadvantage varies across Indigenous groups: the gap with non-indigenous life expectancy ranges from around five years (First Nations and Métis) to more than 10 years (Inuit) (Chief Public Health Officer, 2016[38]), while the deficit in median after-tax incomes is 32% for the First Nations population, 24% for Inuit and 7% for Métis (Statistics Canada, 2017[39]). The relative youth and untapped labour-force potential of Indigenous peoples in Canada offers an opportunity, with a fifth of labour-force growth in the next 20 years estimated to come from Indigenous populations if the labour-force participation gap with other Canadians were to close (Drummond et al., 2017[40]).

As highlighted in the 2016 Survey, the federal government has appropriately made improving outcomes for Indigenous peoples a priority. Additional funding of almost CAD 5 billion over five years was allocated to improve the quality of life of Indigenous Peoples in the 2018 budget, with a focus on skills development, health, housing and child and family services. Building in programme-evaluation mechanisms at the outset is important to ensure that real progress is made, particularly if interventions are designed to make subsequent assessment as simple as possible through identification of control groups. A concurrent review of Indigenous employment and skills strategies recommends continuing work on better aligning federal and provincial Indigenous labour market programmes, seeking opportunities to enhance Indigenous skills training through targeted work experience programmes, as well as exploring how to expand access to higher education to support Indigenous students and increase employment in knowledge-intensive sectors (OECD, 2018 forthcoming[41]).

Table 14. Selected socio-economic outcomes for Canadian Indigenous Peoples, 2016

|

Indigenous Peoples |

Others |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Number in millions (% share) |

1.67 (4.3%) |

|

|

Per memorandum Indigenous in Australia |

0.65 (2.8%) |

|

|

Per memorandum Maori in New Zealand |

0.72 (15.4%) |

|

|

Demographics |

||

|

Average age (years) |

32.1 |

40.9 |

|

% aged 0-24 |

43.7 |

29.2 |

|

Housing conditions |

||

|

% in crowded dwellings |

18.3 |

8.5 |

|

% in dwellings in need of major repair |

19.4 |

6.0 |

|

Education |

||

|

% without a high school diploma |

25.6 |

10.8 |

|

Employment outcomes |

||

|

% employed, 25-54 (2017) |

70.3 |

82.7 |

|

Income |

||

|

Median after-tax income (CAD) |

24 277 |

31 144 |

|

Health outcomes (2011-14 average) |

||

|

% self-rated very good or excellent, 25-44 |

51.5 |

67.0 |

|

% daily smokers |

36.1 |

16.7 |

|

% heavy drinkers |

31.1 |

24.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census; Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey; Statistics Canada, ‘Health Indicator Profile, by Aboriginal Identity, Age Group and Sex’, Table 105-0512.

As Canada’s ECEC expands, quality should be prioritised to realise child development benefits. Regulatory oversight capacity needs to expand alongside service provision, in particular for family (as opposed to centre-based) daycare. Data and monitoring can be a powerful lever to encourage ECEC quality, with implementation of quality monitoring and rating improvement systems internationally associated with better staff-child interaction (OECD, 2018[44]). Development of a professional workforce is also critical. Linking teacher evaluation to training decisions, as in Korea, is a valuable way to encourage professional development, as in-service training stands out as a key driver of better child development and learning outcomes.

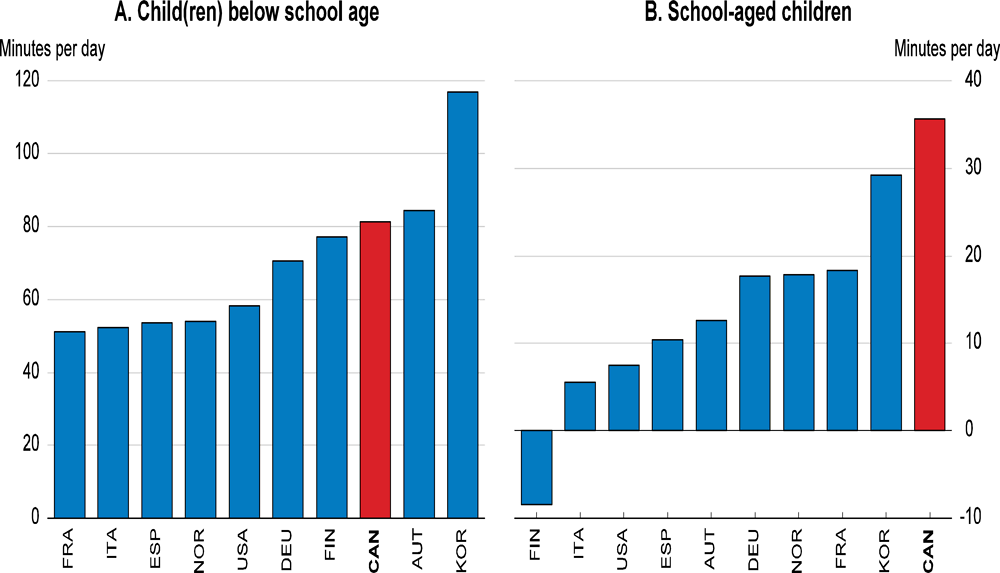

Encouraging fathers to increase their take-up of parental leave would also help to reduce the gender wage gap. The federal government announced an additional five weeks (or eight weeks at a lower payment rate) of non-transferable parental benefits for second parents in its 2018 budget, which over time should reduce the big gender difference in time spent on childcare activities (Figure 19). Fathers who take leave are more likely to take an active role in childcare both early on and after they return to work, and gender differences in time spent on paid work are smaller in countries where such differences in unpaid work are smaller. Take-up should be supported through information provision, leading by example in the public service and, if necessary, increasing payment rates for parental benefits. A 2017 change to parental leave that allows a longer leave period of 18 months, paid at a lower replacement rate of 33%, is less positive, as only the well-off are likely to be able to afford such a big income loss and it carries the risk of weakening some women’s labour force attachment.

The federal government also intends to introduce pay-equity legislation for its civil servants, workers in federally regulated sectors and any contractors bidding for public procurement jobs over CAD 1 million. While this is a worthwhile aim, in practice it is difficult to objectively evaluate the value of different types of work, and similar provincial schemes have had mixed success. The federal government is also subjecting all policy changes to a new “gender results framework” and will by law require gender-based analysis of future budgets. It is thus asking Statistics Canada to generate the relevant data.

Box 5. Simulation of the potential impact of structural reforms

The potential impact of some of the structural reforms proposed in this and the 2016 Survey can be gauged using simulations based on historical relationships between reforms and growth outcomes across OECD countries. Given that the simulations abstract from detail in the policy recommendations and do not reflect Canada’s particular institutional settings, the estimates should be seen as purely illustrative. The policy changes that are assumed (Table 15) are based on comparing Canada’s current policy settings with those of leading OECD countries.

Table 15. Potential impact of structural reforms on GDP per capita after 10 years

|

Change in GDP per capita |

Impact on supply-side components |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Multifactor productivity |

Capital–Labour ratio |

Employment rate |

||

|

Product market regulation |

Per cent |

Per cent |

Per cent |

Percentage points |

|

(1) Liberalise power generation and distribution |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Labour market policies |

||||

|

(2) Increase spending on effective active labour market measures |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

|

(3) Increase government support for childcare |

1.0 |

0.7 |

||

|

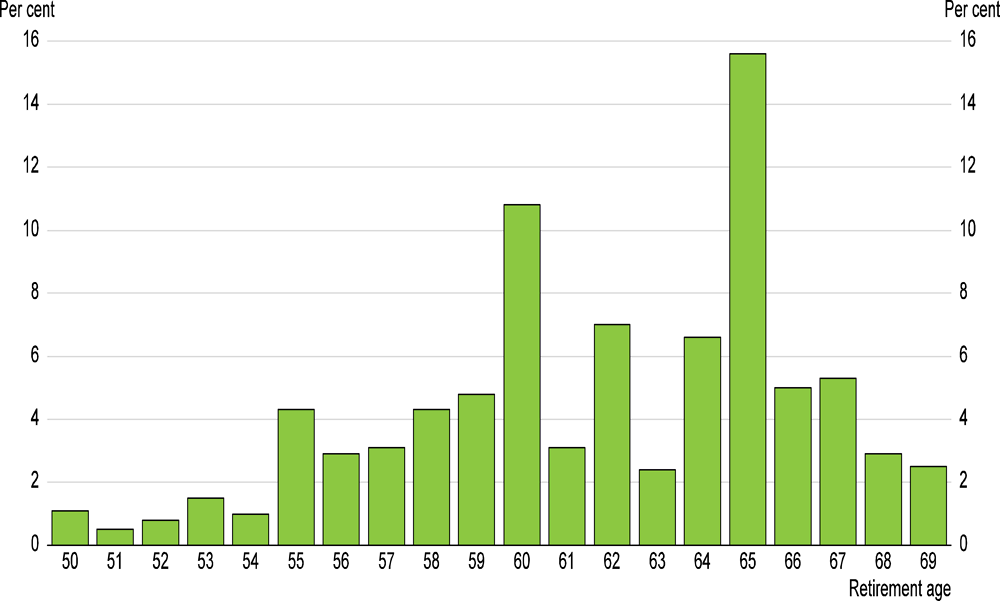

(4) Increase the retirement age |

0.2 |

0.2 |

||

|

Total |

2.3 |

|||

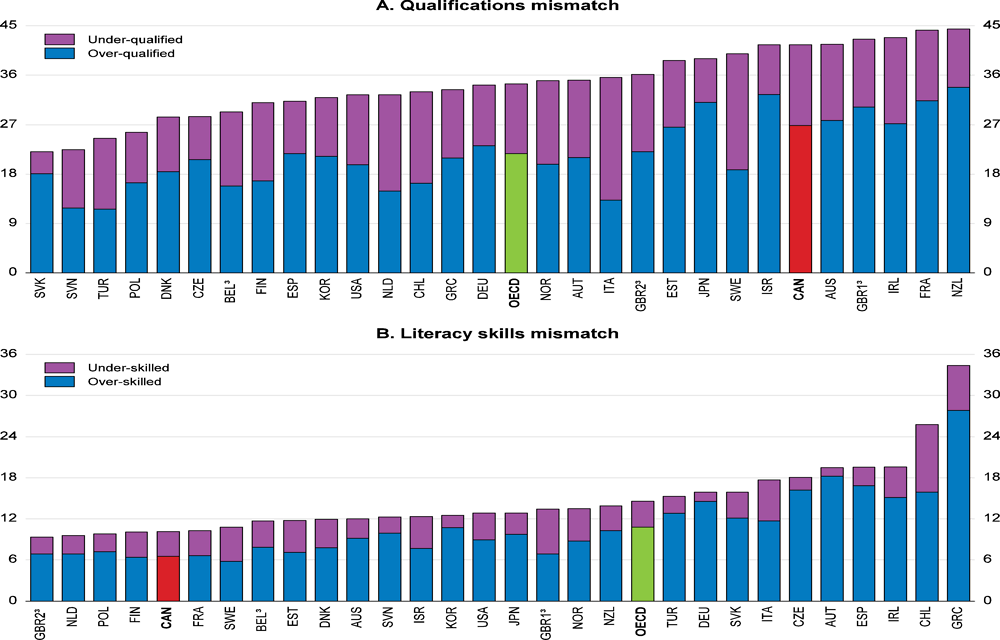

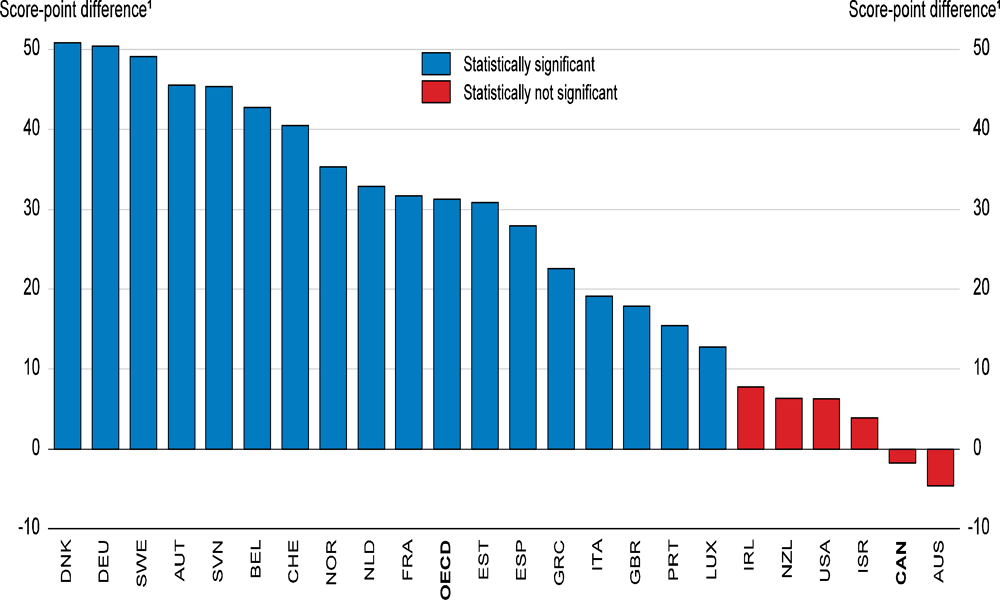

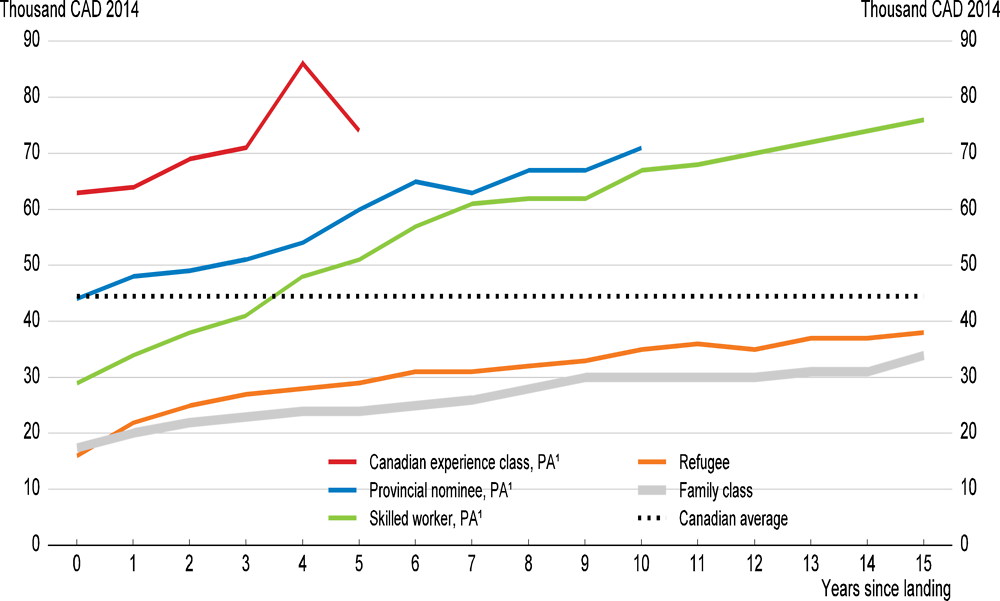

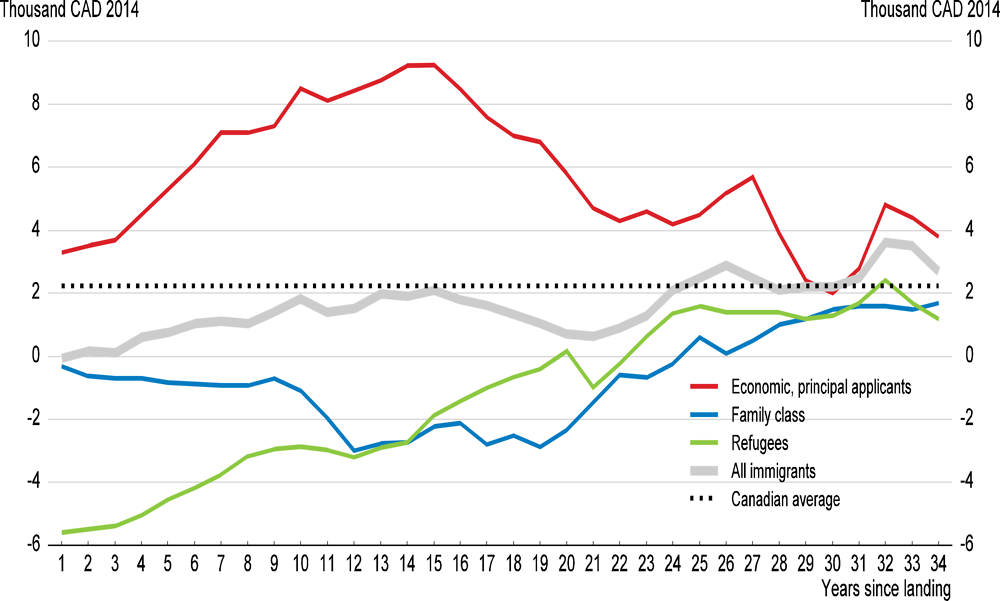

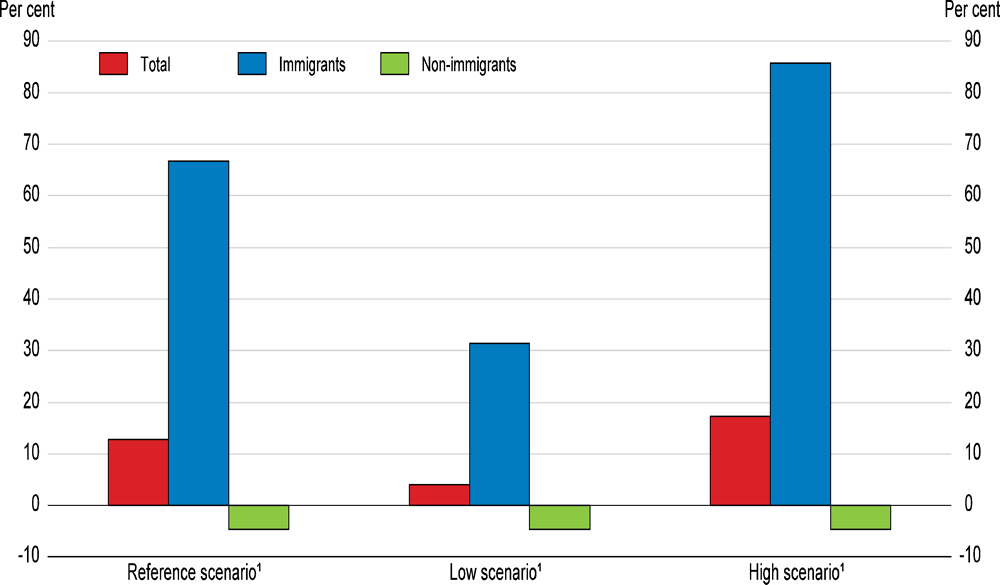

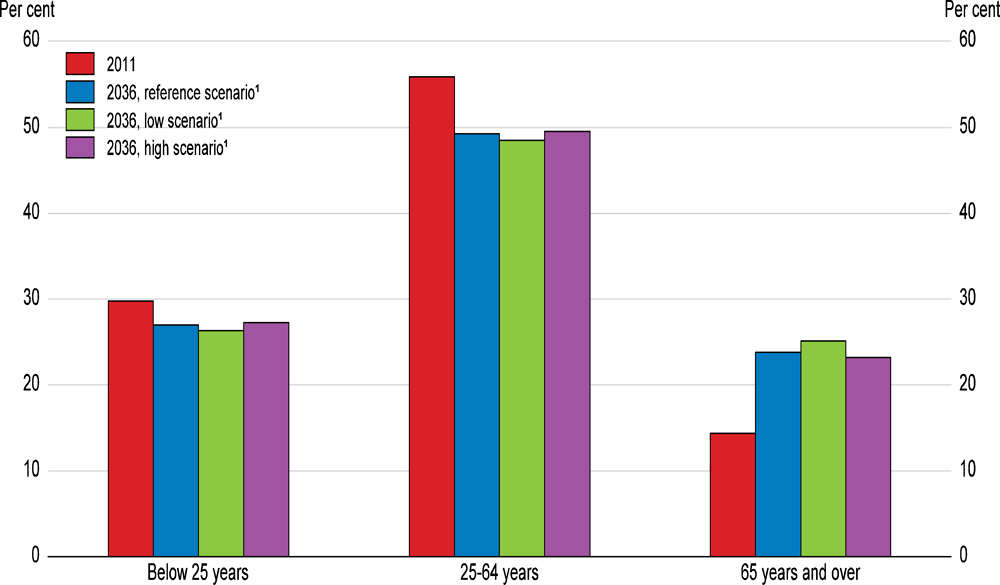

Note: Illustrative policy changes assumed for each measure are as follows: (1) The OECD measure of regulation in energy, transport and communications is lowered from 1.72 to 1.56 by reducing vertical integration and increasing competition; (2) spending on active labour market policies per unemployed worker as a share of GDP per capita is increased from 5.9% to 8.9%, halving the gap with the OECD median of 11.8%; (3) government support for childcare is increased from approximately 0.6% of GDP to 1.1% of GDP, matching spending in the province of Québec and at the 80th percentile of 20 OECD countries included in the analysis in Figure 1.8 in Chapter 1; and (4) the statutory retirement age is increased by 1 year.