Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Alberto Gonzalez Pandiella

OECD

Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Alberto Gonzalez Pandiella

OECD

Education and training are a high priority for Costa Rica that devotes to them more than 6.5% of GDP, one of the highest spending shares among OECD countries. However, educational outcomes remain poor and firms struggle to fill their vacancies, particularly in technical and scientific positions, which may endanger Costa Rica’s capacity to keep attracting foreign direct investment. Its complex fiscal situation requires Costa Rica to improve efficiency and quality of public spending in education to better support growth and equity. There is a fundamental need to improve the quality of early and general basic education to avoid that too many Costa Ricans leave education too early and without the skills needed to find a formal job. This requires a more targeted support to students with learning gaps, improving teachers’ selection and training and expanding access to early education. Revisiting the university funding mechanism will improve its accountability and can help increase the number of graduates in scientific areas. Reforms in vocational education may increase the supply of high-quality technicians, which will reduce existing skills mismatches and help more Costa Ricans access better-paid formal jobs.

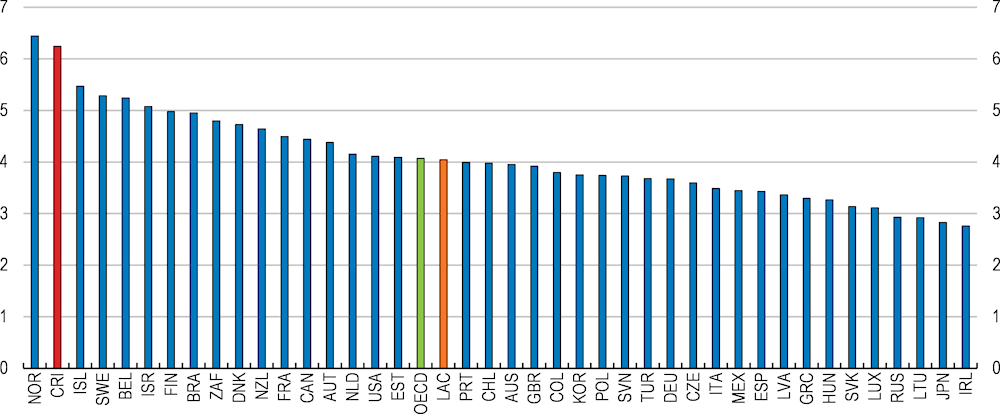

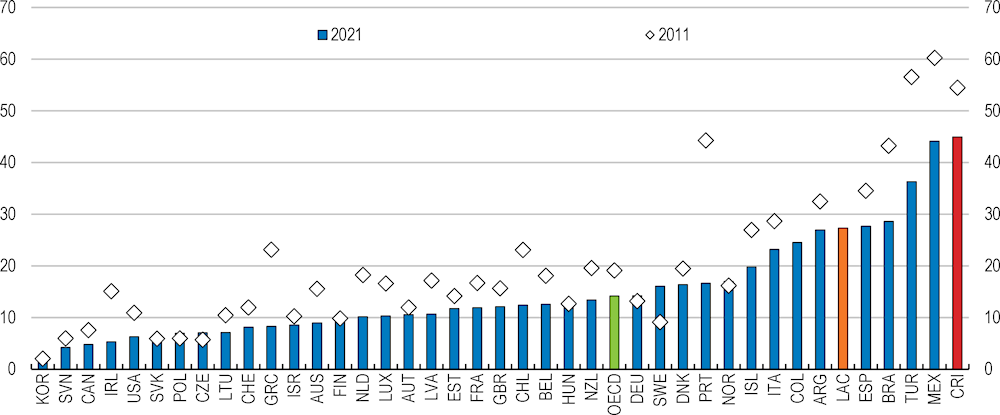

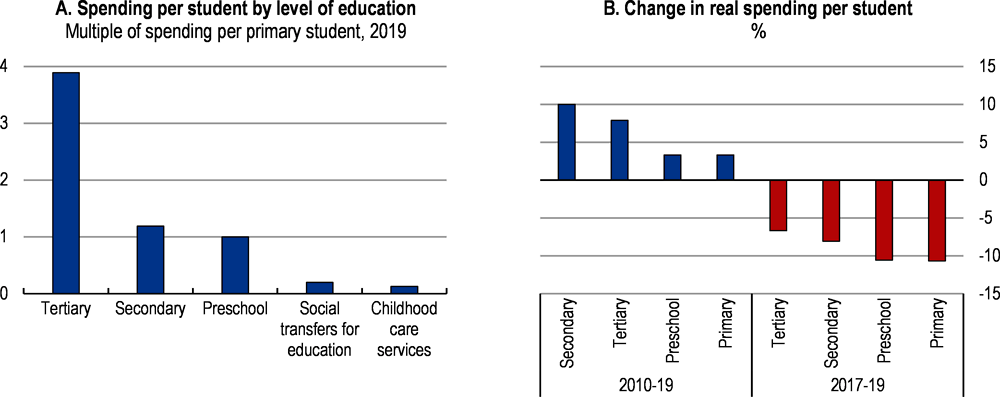

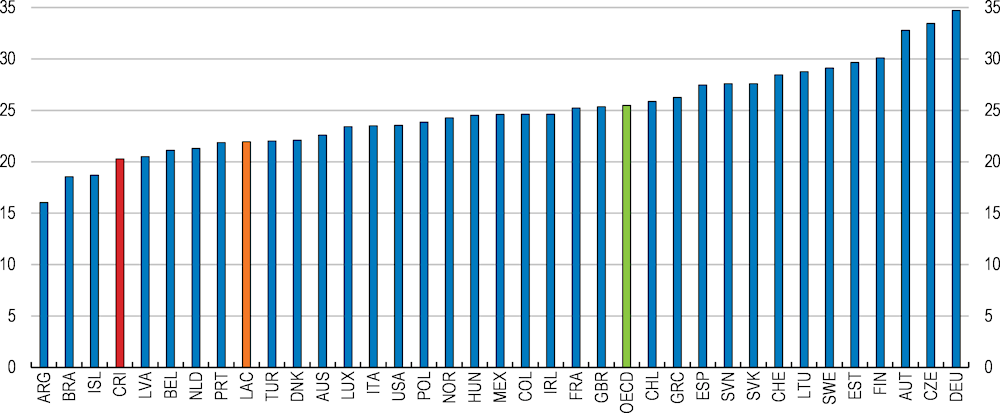

Education and training are a high priority in the political agenda of Costa Rica that spends around 6.5% of GDP on education (Box 2.1), the second highest share across OECD countries (Figure 2.1), though below the 8% achieved in 2017. Universal and high-quality education is crucial for equality, promoting social mobility and productivity. Training, re-skilling and up-skilling will become more and more a necessity to provide current and future workers with the right skills to integrate into a labour market whose needs change fast driven by technological change, climate change, digitalisation and automatisation.

Spending in education, % of GDP, 2018

Note: Data for Costa Rica refers to 2019. LAC refers to Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil. The education budget is distributed to the Ministry of Public Education (Preschool, I and II Cycles, III Cycle and Diversified Education); the Special Fund for Higher Education (5 public universities: UCR, TEC, UNA, UNED, UTN), and the Care Network, CEN-CINAI, INA and about 50 other institutions.

Source: OECD Education Database.

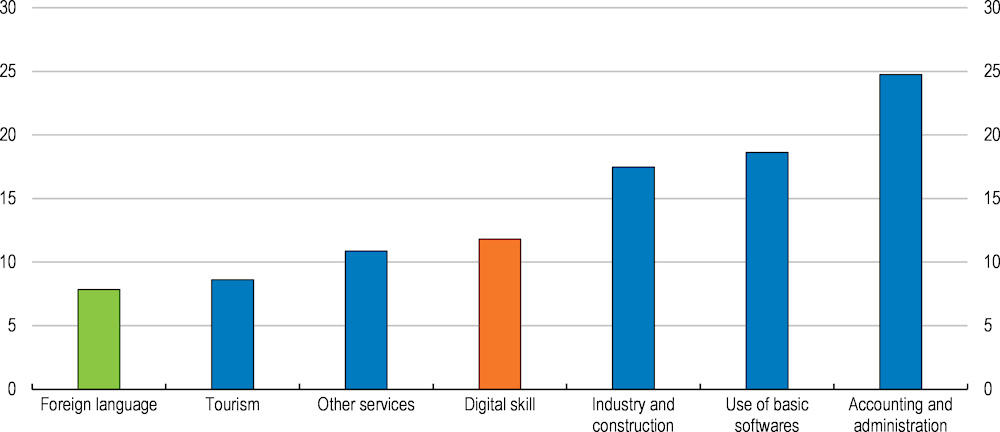

Developing highly skilled talent is key to allow Costa Rica to keep transforming its production structure towards knowledge intensive and high value added sectors, also by continuing to attract a large and stable inflow of FDI (see Chapter 1). Currently, firms struggle to find highly qualified technicians and tertiary graduates, especially in scientific fields, leaving many formal jobs vacant. In the services sector, one job offer out of three is for technicians and one out of four for professionals with tertiary education (INEC, 2018[1]). In the industrial sector, around one third of firms report that technicians are the most difficult workers to recruit (UCCAEP, 2021[2]). Digital skills and a good knowledge of a foreign language, especially English, should be strengthened at any level of education, but especially at an early age. These skills, together with having completed secondary education, are becoming essential requirements for a formal job. However, the vocational educational and training system (VET) supplies mostly low-skilled technicians, provides little work practice and offers too few opportunities to acquire advanced digital skills or specialise in STEM sectors, fuelling a mismatch between labour demand and supply. The lack of talent in regions outside the Greater Metropolitan Area (GMA) limits their possibility of attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). Currently, 95% of the industry related to technology innovation and 70% of the export industry is located in the GMA, which corresponds to 3.7% of the territory of Costa Rica and hosts around 52% of the whole population.

Costa Rica has achieved near universal attendance in primary education but still too many young students in Costa Ricans do not complete secondary education. Grade repetition and educational exclusion remain sizable and affect disproportionately the most vulnerable, reducing their probability of finding a formal job and perpetuating social and economic inequalities. International students’ assessments, such as PISA, show that the quality of education needs improving, with too many 15-year old students having low reading skills and even worse performance in mathematics and sciences. Educational exclusion and poor learning outcomes prevent many young Costa Ricans from accessing tertiary studies, and the number of tertiary graduates has been stalling in recent years. The provision of educational services in Costa Rica has been discontinued during the last four years. The teachers’ strike in 2018, to protest against the fiscal reform, and in 2019, to protest against a bill aimed at limiting the right to strike, caused cumulatively around four months of missed classes. The outbreak of the pandemic caused school closures and the shift from face-to-face to remote education in 2020 and 2021, thus provoking further disruption in the provision of educational services and aggravating pre-existing educational weaknesses and learning losses, with potentially scarring effects on current cohorts of students.

Increasing the quality of the education and VET system is also crucial to improve the resilience of the economy to the challenges of population ageing and technological change that Costa Rica faces (see Chapter 1). Many traditional jobs will be automated and the new ones that will be created will require new skills. A flexible and efficient VET system that provides the necessary reskilling and upskilling for at-risk or displaced workers, and produces more technicians in areas that are less at risk of automation in Costa Rica (e.g. telecommunication and information technology) (Amaral, 2019[3]), would avoid exacerbating inequality. Better-educated and high-productive workers are necessary in a future where fewer workers must be able to pay benefits to a larger number of retirees.

This chapter describes the main challenges that Costa Rica faces to increase access to education and training and improve its quality, and discusses policy options to tackle them. Costa Rica’s limited fiscal space requires the government to prioritise where to concentrate its spending efforts. A substantial re-priorisation of expenditures in favour of compulsory schooling and ECECs and away from tertiary education, where spending per student is higher than in the average OECD country, would have large social benefits and contribute to reduce inequalities.

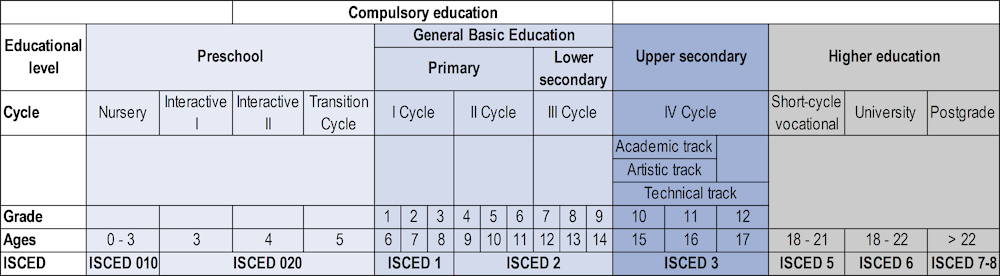

The education system in Costa Rica includes preschool or early child education and care services (ECES), primary education, (lower and upper) secondary education, and tertiary education. Compulsory education includes the last two years of preschool (Interactive II and Transition Cycle) and general basic education (primary school (I and II Cycles) and lower secondary school (III Cycle)).

Preschool education is divided into the following sections: Nursery (from birth to 6 months), Babies (from 6 months to 1 year old), Maternal Education Level 1 (from 1 year to 2 years old), Maternal Education Level 2 (from 2 years to 3 years and 6 months old), Interactive I (from 3 years and 6 months to 4 years old), Interactive II (from 4 years to 5 years old ) and Transition cycle (from 5 years to 6 years old). Early age care services (0-3 years) are voluntary, while preschool is compulsory for children from four years of age. Babies, Maternal Education Level 1 and 2, and Interactive I belong to non-formal education.

Primary education is divided in two 3-year cycles and includes grades from first to sixth. Lower secondary education (III Cycle) goes from seventh grade to ninth grade.

Upper secondary education (IV Cycle, Educación Diversificada) is free but not compulsory. It comprises three tracks: the academic and artistic track, which last two years, and the technical track, which lasts three years. Completing upper secondary education is required to access higher education. Students completing the technical track obtain the qualification of mid-level technician.

Higher education is offered at universities (public and private), university colleges and higher education institutes. A bachelor’s degree requires a four-year programme, the programmes of licenciatura last five years (six years in the case of medicine and surgery). Master’s degrees’ (going beyond university bachelor´s degree or licenciaturas) last two years. Doctoral academic programmes last at least three and a half years.

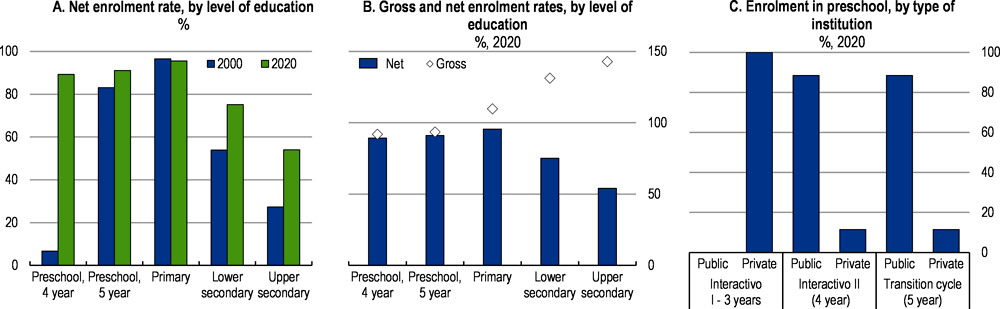

Costa Rica has remarkably increased access to preschool for four-year-old children (Figure 2.2, Panel A) by making the last two years of preschool (ages 4 and 5) compulsory in 2018. This very welcome reform recognizes the fundamental role of preschool education on the cognitive and socio-emotional development of children. Experiences received between 2 and 5 years of age are key to reduce or prevent learning issues in successive phases of education (UNICEF, 2020[4]; PEN, 2011[5]).

Note: The gross enrolment rate is the total enrolment in a specific level of education, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the population in the official age group corresponding to this level of education. It can exceed 100% because of early or late entry and/or grade repetition. The net enrolment rate is the ratio of children of official school age who are enrolled in school to the population of the corresponding official school age.

Source: PEN 2021.

At earlier ages (0-3 years), the enrolment rate is very low (below 3% compared to an OECD average of 36.1%) and the supply is offered almost entirely by private institutions (Figure 2.2, Panel C). Children from disadvantaged households are less likely to attend ECEC. While 60% of children from low-income households (first income quintile) are enrolled in preschool (from three to five years), the share is above 70% for children from high-income households (top income quintile) (SEDLAC, 2021[6]). Costa Rica should expand the coverage of early education and care to children below 4 years, giving priority to low-income households.

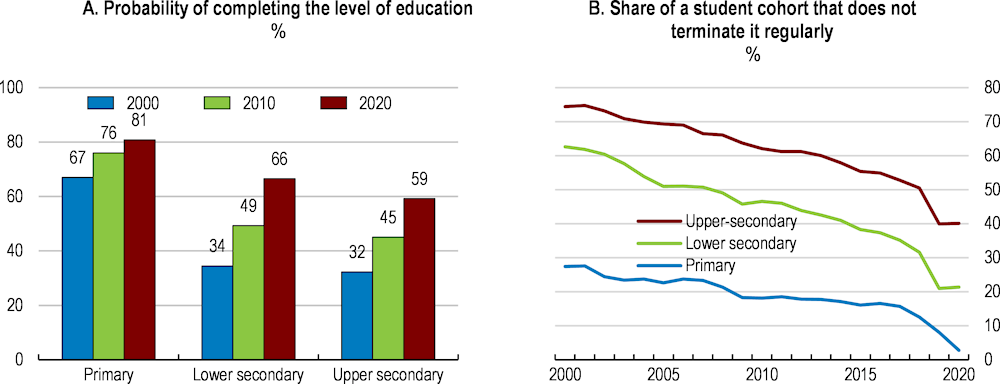

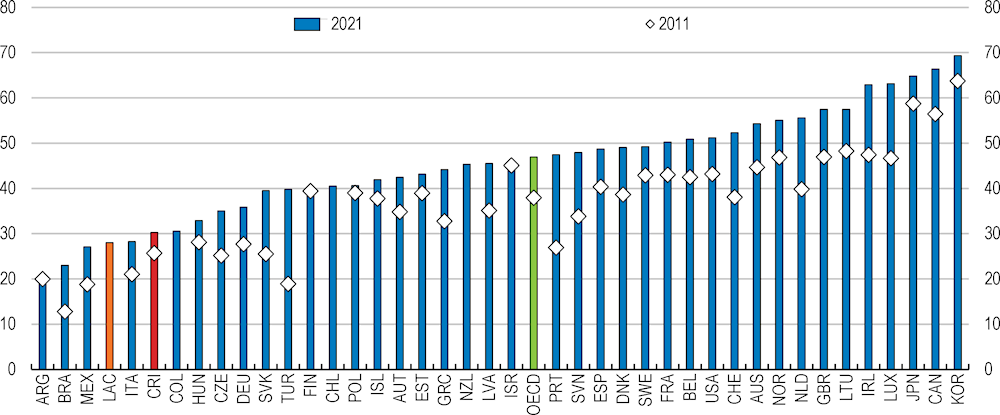

While most Costa Rican’s now finish primary education, many of them still finish school without a lower or upper secondary degree (Figure 2.3). The net enrolment rate in lower and upper secondary school remains low (Figure 2.2, Panel B) and Costa Rica has the highest share of young adults with educational attainment below upper secondary among OECD members (Figure 2.4). This represents a serious limitation to the development of human talent and restraints the demand for higher education, as upper secondary schooling is a requirement to access it (Box 2.1). Completing upper-secondary schooling is becoming an essential requirement to find a job in Costa Rica. For example, three out of four jobs offered by private firms in the services sector required at least full secondary education (Figure 2.5) (INEC, 2018[1]).

A key problem to tackle is educational exclusion in secondary education. In recent years Costa Rica reduced educational exclusion by strengthening prevention measures (Box 2.2). However, a young Costa Rican had only a probability of 66% of completing lower secondary school, and even a lower probability of completing upper secondary school (59%), in 2018, the last year before the pandemic hit, (Figure 2.3, Panel A). Still too many students leave after primary school, which points to persistent issues in the quality of education (Figure 2.3, Panel B) and highlights the lack of policies to help students in the transition from primary to secondary education.

Note: Panel A: The probability of completing primary school refers to a person between 12 and 16 years of age, of completing lower secondary school to a person between 15 and 19 years of age and of completing upper-secondary school to a person between 18 and 22 years of age. Data for 2020 could be overestimated due to evaluation procedures being relaxed during the pandemic. Panel B: Share of a student cohort enrolled in the first year of an education level that does not terminate it regularly because of dropout or grade repetition.

Source: PEN 2021.

Percentage of 25-34 year-olds with below upper-secondary education as the highest level attained

Note: LAC refers to Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil.

Source: OECD Education Database.

Distribution of job positions according to minimum education required, %, 2019

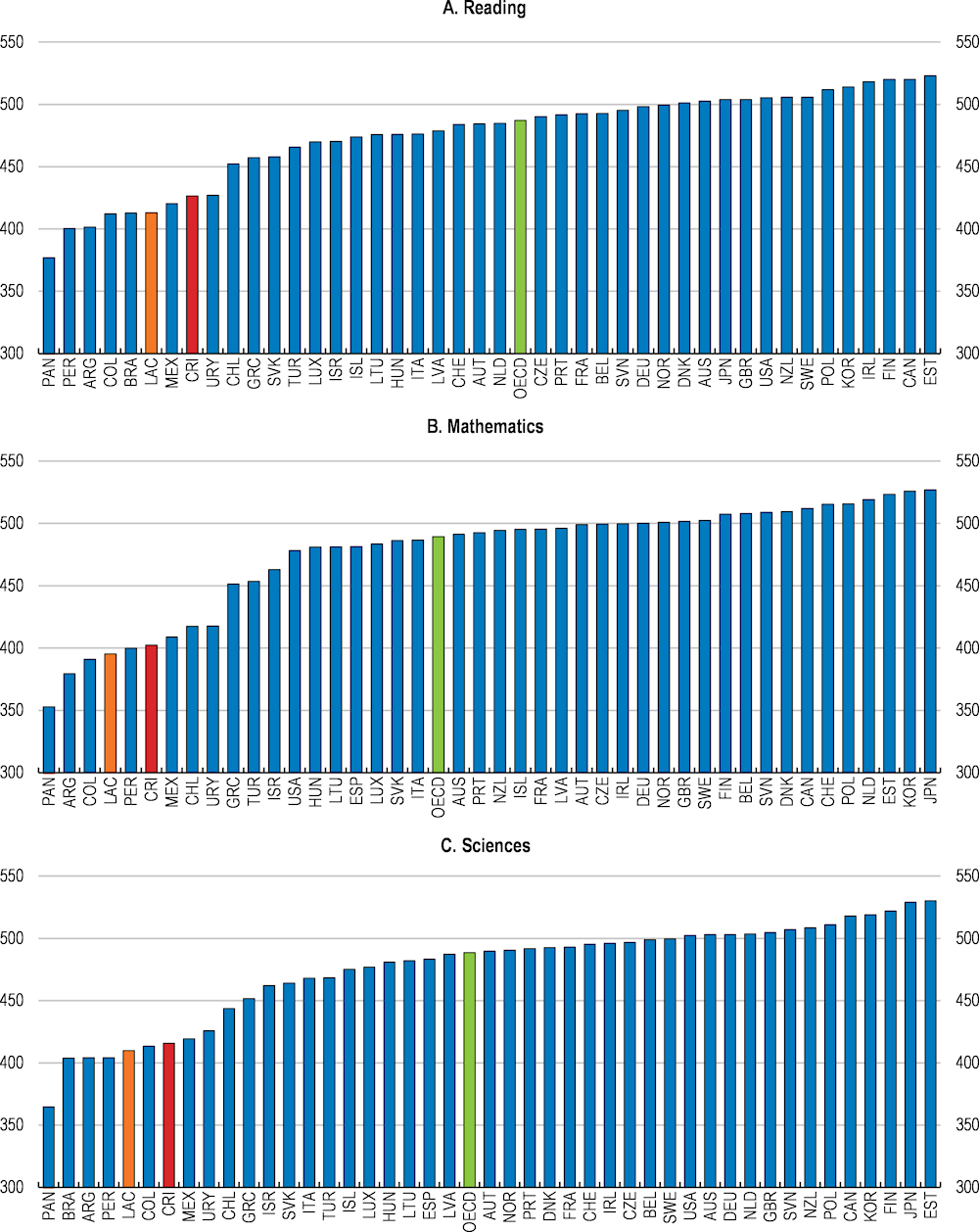

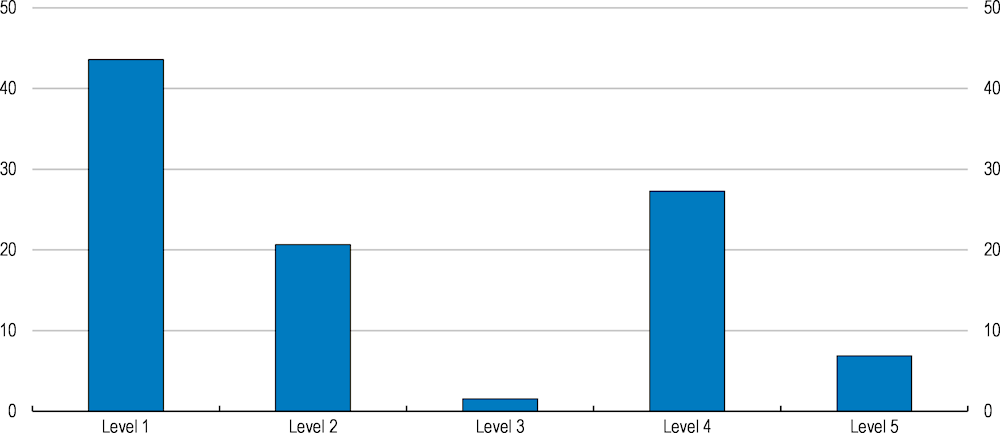

A consequence of the poor quality of education is that too many students in Costa Rica perform below the minimum level of skills in national and international student assessments. The performance of 15-year-old Costa Rican secondary students in the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) continues to be below the OECD average in reading, sciences and mathematics (Figure 2.6). The proportion of students scoring at the two lowest levels of performance is far higher than the OECD average (Figure 2.7). Results also show no improvement in reading and science scores between 2012 and 2018, once the impact of changes in the coverage rate are taken into account (OECD, 2019[7]). These results are in line with those from the 2019 fourth regional comparative and explanatory study (ERCE) (UNESCO, 2019[8]). Moreover, both ERCE 2019 and PISA 2018 show persistent gaps in performance between boys and girls, with girls outperforming boys in reading, and boys outperforming girls in mathematics and sciences. PISA tests also highlight that boys have better digital skills. National tests assessing educational performance in English knowledge show that only one third of the students (fifth grade and tenth or eleventh grade) achieve the level of knowledge of English that they are expected to have.

The pandemic has further exacerbated learning gaps. It caused discontinuity in the provision of educational services in 2020 and 2021, with Costa Rica recording one of the longest school closure among OECD countries (175 days) (OECD, 2021[9]). Shifting from face-to-face to remote learning led to a reduction of the curriculum covered at school, which together with difficulties with connectivity or in following classes, increased educational losses especially among students from vulnerable groups (e.g. poor, migrant, indigenous, students without internet connection and preschool students). The pandemic in 2020-21 also followed teachers’ strikes in 2018 and 2019, thus extending to four years the period of time during which the provision of educational services were discontinuous in Costa Rica. Educational losses due to a protracted school closure may have a large impact on labour-market chances and career earnings of the affected students, especially for the most disadvantaged ones, and on GDP growth if adequate policies to make up for such losses are not put in place (Égert et al., 2020[10]; Hanushek and Woessmann, 2022[11]).

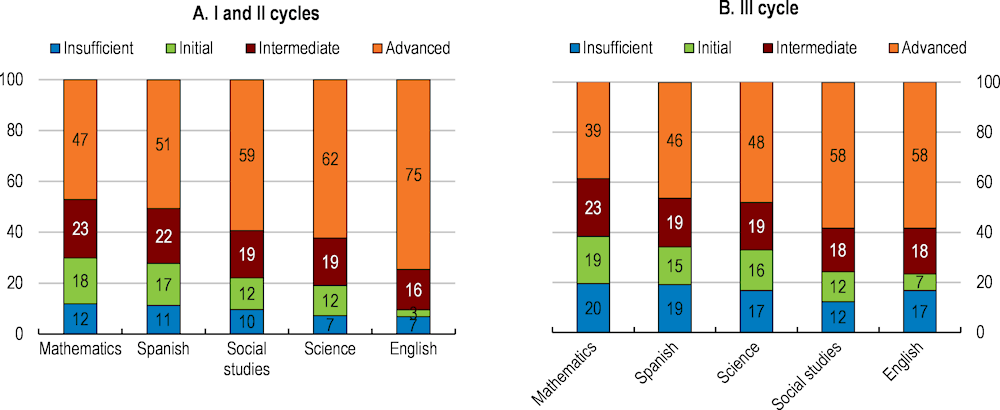

Several tests, among which the 2021 students’ performance diagnostic tests performed on students from primary (I and II cycle) to lower-secondary school (III cycle), the 2019 ERCE tests, the Ministry of Education’s school census, and the Test of English for Young Learners and Linguistic Performance Tests, were used as input in the National Comprehensive Plan for Academic Levelling 2022-25 (Plan Integral de Nivelación Academica 2022-25), that provided an assessment of learning needs after the pandemic. Results show that the share of students in need of support because of an insufficient or initial level of knowledge ranges between 10% (English) and 30% (mathematics) in primary school, and between 24% (English and French) and 38% (mathematics) in lower secondary (Figure 2.8). Educational needs are concentrated among students in first year of primary school, where one student out of three reports an insufficient level of knowledge of Spanish and mathematics. Still in 2021 no support staff had been provided to attend students most in need (Murillo, 2021[12]).

Score in PISA 2018

Note: LAC refers to Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Panama, Peru, and Uruguay.

Source: OECD PISA International Dataset.

Distribution students' PISA score in reading, mathematics and science by level, % of students, 2018

Share of student with insufficient level, by grade and subject, I to III cycle, 2021

Note: The knowledge of a student in a subject is considered as insufficient when it is below the level that a student of that grade should have acquired according to the grade curriculum.

Source: Ministry of Public Education.

Several policies exist in Costa Rica to reduce educational exclusion:

The programme young adults (Jóvenes Adultos) targets the population above 15 years of age who did not complete primary or secondary school (potentially 1.4 million person, half of which are below 40 years of age).

The National Grant Fund (Fondo Nacional de Becas, FONABE), until 2021, and currently the programmes Avancemos provide grants to participate in programmes for educational reincorporation for adults up to 40 years old. The Directorate of Equity Programs of the Ministry of Education provides post-secondary scholarships.

The programmes I am in (Yo me apunto) and PROEDUCA, aimed to reduce educational exclusion in secondary school, were merged in 2018 into the Unit for the Permanence, Reintegration and Success in Education (Unidad para la Permanencia, Reincorporación y Éxito Educativo, UPRE). Since 2018 each school has a UPRE tasked with identifying, supporting and monitoring students at risk of exclusion from education.

The strategy Building Bridges for the Future (Construyendo Puentes para el Futuro) was launched during the pandemic to strengthen the permanence in education of all students. It favoured the creation of networks among students, teaching staff, and families to provide support and maintain alive the links between students and schools.

Learning outcomes in Costa Rica are strongly associated to socioeconomic conditions. Students from households with a high socioeconomic background are more exposed to cultural stimuli, benefit from better conditions for studying at home, including the availability of books, access to internet and digital devices, have better educated parents who may also pay for extra lessons, and have better educational performance (Figure 2.9). On the contrary, most low-performing students are from vulnerable groups (PEN, 2021[13]), including indigenous or immigrant population (Box 2.3), and have a higher likelihood of dropping out (Figure 2.10).

Reducing inequality of opportunities in education would improve substantially learning outcomes. For example, PISA tests show that students from private schools (around 10% of all secondary students) outperform those from public schools and that if all students performed as the average student from a private school, the score of Costa Rica in reading would increase to 460, approaching the OECD average of 485 (Bos, 2019[14]). However, students from private schools are mostly from high-income households (PEN, 2021[13]) and the performance disparity between public and private schools in Costa Rica actually disappears after accounting for students’ and schools’ socioeconomic status (OECD, 2021[15]).

The pandemic deepened inequality in education opportunities. Many families, especially those with a low socioeconomic background, were ill prepared to support the education of their children. Technological vulnerability caused many Costa Rican students educational exclusion, at least partially. Around 45% of the students enrolled in the 2020 academic year (535 thousand out of 1.180.000 students from primary to upper secondary) did not benefit from adequate conditions to continue receiving educational services because they lacked either technology devices (computer, tablet) or an internet connection (PEN, 2021[13]). Most of these students belonged to vulnerable groups. For instance, while around 78% of students from families in the top income quintile had access to a good internet connection, the share drops to 41% for students from families in the bottom income quintile (PEN, 2021[13]).

Average performance by socioeconomic condition, ERCE 2019

Share of a given population attending any educational level, by age and equivalised income quintiles, %, 2019

Reading score by attendance to preschool

Note: Reading skills are defined as the capacity of reading, understand tests and implementing complex strategies to process information (analysis, synthesis, interpretation).

Source: OECD PISA Database.

Immigrants in Costa Rica are around 9% of the total population (Census 2011), a majority of which from Nicaragua (75% of the immigrant population). A large proportion of adult immigrants is employed in low-skilled and low-wage informal jobs in agriculture, construction and domestic services. Immigrants tend to be poorer than locals (OECD, 2017[16]) and their wage is on average around 60% of that of native workers (OECD, 2018[17]).

Young immigrants between 15 and 17 years are less likely than locals in the same age group to be enrolled at school, and those who attend school have worse learning outcomes. Immigrant students performed worse than native students in PISA 2018 in science (20 points less), reading (26 points less) and math (30 points less) (OECD, 2019[18]).

Despite a lower access to education, a worse economic condition and poor learning outcome, immigrants are less likely than locals to benefit from social programmes in education (conditional cash transfers, grants, transport and food aid) (OECD, 2017[16]). A specific academic levelling program for immigrant students and a better targeting of social programmes in education towards the immigrant population would reduce inequality of opportunities in education, and improve his perspective for future employability and social inclusion.

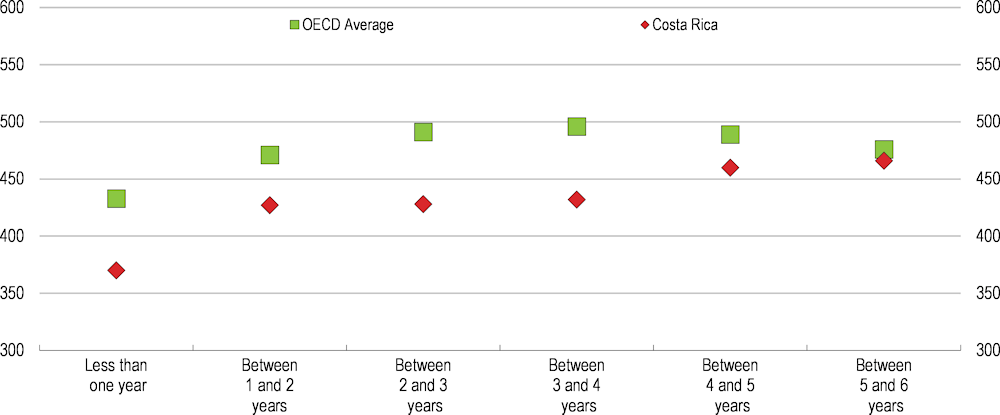

International evidence shows that attending preschool increases students’ performance in any subject and at any level of education (OREALC-UNESCO, 2015[19]), and results from PISA 2018 confirm it (Figure 2.11). However, children from low-income households are far less likely to attend preschool than children from top-income households (Figure 2.10). Extending preschool may contribute to bridge the gap in results between Costa Rica and OECD countries (Bos, 2019[14]).

Investing in early education produces long term positive effects that are above their initial costs (OECD, 2017[20]), especially when targeting children between 0 and 3 years (Maureen M Black, 2017[21]). Given that in one third of the households with children below 6 years of age the adults have low educational attainment (PEN, 2015[22]), the benefits from extending access to ECEC since an earlier age are potentially large and would contribute to reducing inequality in education. The four-hour school day for children between three and five years of age could be extended (PEN, 2017[23]) to better attend children’s learning needs, especially those from vulnerable groups.

The Ministry of Labour estimates that an additional 90 thousand children should attend ECECs. To this aim, further spending for infrastructure and additional preschool teachers would be required. A project of co-payment mechanism involving several stakeholders (households, firms, local governments) was launched on a small scale to provide alternative sources of funding to the expansion of the capacity of ECEC services for children below 4 years of age. If it proved successful, it could be scaled up. The design of childcare benefits should also be modified as currently many employed women from low-income households are not eligible for childcare benefits as the income threshold is too low.

The governance of the set of social policies targeting early childhood remains fragmented among several ministries - IMAS (social and economic inclusion), MEP (education services), the Health Ministry and PANI (human rights) that also has coordination tasks. Recent improvements in their coordination are represented by their interaction in the programmes NiDo, though for a limited period, and RedCudi. However, having a single institution with overall responsibility for delivering the national policy across the whole sector could provide better monitoring and accountability (OECD, 2017[24]).

There have been advances in coverage, quality, training and monitoring of ECEC provided within communities. However, mechanisms for evaluating the performance of preschool teachers and the overall quality of ECEC provision remains incomplete, as quality standards and teachers’ performance evaluations exist only for early education services for children between 4 and 6 years old. Completing the ongoing process for the definition of qualification frameworks for the whole ECEs would help filling this gap.

Costa Rica started in 2008 a curriculum reform to update content and teaching practices of all subjects from preschool to upper secondary to increase the quality of education. While study programmes have all been revised, their effective implementation in class is heterogeneous across subjects and levels of education. A full implementation of the reform would require retraining part of in-service teachers, adapting the formation of new teachers, adjusting the didactic material, providing an adequate infrastructure, and a continuous monitoring to adapt the content of the curriculum to the evolving needs of society.

Improvements in the curriculum are particularly important at the primary level. While the vast majority of primary schools (91.5%) offers the basic curriculum (Spanish, mathematics, science, social studies, civic education and English), only 8.5% of them offer the complete curriculum, which includes complementary subjects (informatics, music, plastic arts, physical education, industrial arts and home education), even though it should be offered by all primary schools since 2008. Lack of infrastructure and of teachers in specific subjects are among the causes of the incomplete coverage. Moreover, the wage scheme provides incentives for teachers to work in schools not offering the full curriculum but operating under a different regime (doble jornada) where they earn more by working more hours by teaching the same class to different groups of children attending the morning or the afternoon shift. However, students at schools operating under a doble jornada regime only attend one shift (morning or afternoon), thus receiving each month 60 hours of class less than what they would receive under a full time regime.

Extending the full curriculum to all schools would reduce the relevance of students’ socioeconomic background on their performance and increase equity in education, as vulnerable students are less likely to receive support from their families. A practical challenge for extending the full curriculum to all schools is the need for better infrastructure conditions and more food and transportation services for students. Modifying the economic incentive for teachers to work under a doble jornada regime could help increase the number of schools offering the full curriculum. In the medium-long run, adapting part of the curriculum to cover subjects related to local conditions and extend the range of complementary subjects (e.g. financial education, self-care strategies) would help meet the needs of local communities and improve students’ development.

Giving the rise in digitalization, digital skills could be strengthened at any level of education, and the curriculum should also give sufficient attention to equipping students with digital skills since an early age. Digital skills do not depend only on having access to digital technology but also on how they are used (Erstad, 2010[25]). Acquiring good digital skills is fundamental to integrate in modern society and increase employability (Zúñiga, 2021[26]). Costa Rica should address inequality in education due to technological vulnerability by targeting universality of digitalisation. This could be achieved by legislating and implementing the National Programme of Digital Literacy, which is still pending; and making progresses in the implementation of the Ley de Creación del Bono de Conectividad para la Educación that aims to ensure access to connectivity throughout the country within five years.

Further academic and economic support should be provided to low performing primary and secondary students to reduce educational exclusion and grade repetition and increase equality of opportunity in education. International evidence shows that providing learning support at an early age improves learning outcomes (UNESCO, 2019[8]) and helps reduce inequality in education.

Costa Rica could provide students with accumulated educational losses the necessary support through remedial programmes (Box 2.4), including offering additional or specialised pedagogical support, be it through teaching assistants and mentors, extending hours of classes, organising holidays programmes and after school tutoring (Box 2.5). Priorities could be defined on the basis of results from 2021 diagnostic tests that highlighted that students with learning gaps are concentrated in early grades.

Low-performing students, especially if from vulnerable groups, could benefit from policies strengthening personalised support. For example, France’s 2016 lower secondary reform allows schools to allocate up to three hours per week to different forms of personalised support. In Portugal, the Education Territories of Priority Interventions Programme (TEIP) has successfully reduced educational exclusion in almost all school levels, by designing and implementing multi-year improvement plans in areas with a high average share of socially disadvantaged population. Also, many countries have invested in digital platforms that offer more personalised learning opportunities (Estonia, Korea, Slovenia and Latvia).

In Costa Rica, conditional cash transfer programs aimed to support education of vulnerable groups, like Avancemos, lose effectiveness for poor targeting, as a significant number of benefits are delivered to not vulnerable households (see Chapter 1). Other economic aid aimed at supporting access to education to students from vulnerable households (poor and extremely poor), who are around one third of all students across levels of education, also fall short of target. For example, only 10% of eligible households with children in preschool, and 56% of those with children in secondary schools, actually received any grant or economic aid in 2020 (PEN, 2021[13]). The National Registry of Beneficiaries of Social Programmes (Registro Nacional de Información y Registro Único de Beneficiarios del Estado, SINIRUBE) should become the central tool to improve the targeting of education policies towards low-income families.

Reducing class size could also help reduce educational exclusion in Costa Rica. A recent study finds some evidence that reducing the seventh grade class size by 10 students would increase the pass rate by 5 percentage points (from 70% to 75%) (Vega-Monge, 2021[27]). Costa Rica could attempt a cost-efficient strategy of reducing the class size in grades that record more dropouts (seventh and tenth grade).

International evidence highlights that providing professional development opportunities for teachers, the presence of a large vocational education programme and having attended preschool are factors strongly and positively correlated to reducing educational exclusion (Bonnet, Forthcoming[28]). Costa Rica could strengthen pedagogical support and in-service teacher professional development to further reduce educational exclusion. The range of training activities may include courses on education-related topics or methods; participation in a network of teachers formed specifically for the professional development of teachers; and mentoring and/or peer observation and coaching.

To reduce the role of socio-economic conditions on educational performance, public resources could be allocated among schools on the basis of student needs. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Pupil Premium Programme allocates additional funding to schools for each student receiving free school meal. This funding is used to put in place measures that improve the learning outcome of disadvantaged students. Schools are held accountable for their spending through inspections and online statements (OECD, 2021[29]).

Alternative measures could be found to grade repetition, which has generally unfavourable effects on repeaters’ academic achievement (Goos, 2021[30]) and causes segregation by expelling low achievers. Creating a programme that addresses the shared academic needs of groups of students may be an efficient approach when it is not possible to provide customized intervention. Teachers may receive training to learn how to diversify their approach so as to meet the needs of their low-performing students. In addition, the learning time of low performing students could be extended through after-school, week-end or summer programs (Protheroe, 2007[31]).

Several countries during the pandemic recruited temporary teachers or other staff in at least one educational level to implement measures to support students in need, and organised remedial programmes providing additional or specialised pedagogical support for students in need of special support, which in some cases was extended at the reopening of the schools. In France temporary teachers were hired to cover the absences of teachers testing positive and in Luxembourg temporary staff was hired to assist teachers with organisational and administrative tasks. Spain implemented a wide-ranging education recovery plan including teaching assistants and mentors providing personalised support to students with specific educational needs, both inside and outside of school hours. Finland and Denmark provided additional funding for remedial programmes, also targeted at disadvantaged students. In Portugal, schools provided students at risk with greater training and education. In France a learning holidays programme was organised during the summer of 2020 to help one million students catch up on learning.

Source: OECD (2021), Education Policy Outlook 2021: Shaping Responsive and Resilient Education in a Changing World.

In the spring of 2021, the Esade Centre for Economic Policy and the Fundación Empieza Por Educar launched Menttores, a programme providing free afterschool tutoring for deprived pupils hardest hit by Covid-19. Menttores consisted of an 8-week long, intensive online tutoring program, with three 50-minute sessions a week for pupils aged 12 to 15 (years one and two of compulsory secondary education in Spain) in Madrid and Catalonia. Priority was given to schools in low-income districts with a high share of immigrants. All afterschool tutoring was carried out using digital devices in groups of two pupils per mentor and focused on maths and social-emotional support (motivation, well-being, work routines). Fifty-two academic mentors took part. Forty-five of them were paid for, qualified secondary school teachers and the remainder were volunteers. All of them received training. The programme was completed by 96.6% of pupils, attending an average of 17 sessions (70.8% of all sessions) and 920 minutes (76.7% of the target).

Results show that pupils taking part in the programme experienced a significant improvement, as the programme led to a 17% increase in end-of-year maths grades, the equivalent of six months of learning. Children who took part in the programme were 30% more likely to pass the subject (maths) than children in the control group. The programme reduced the share of pupils repeating the academic year by 8.9 percentage points, equivalent to a reduction by 75% compared to the control group. The programme also had a positive impact on pupils’ socioemotional wellbeing and aspirations, as participants were 31% more likely to want to continue studying the academic track in upper secondary school (post-compulsory secondary schooling) than those who did not participate.

Source: (Arriola, 2021[32]).

In Costa Rica there is a poor governance of school infrastructure, which makes infrastructure projects difficult to develop and prone to fail to meet their timeframe and budget objectives. Costa Rica lacks an accurate inventory of its educational infrastructure and existing data are partial and based on school inspections from the Directorate of Educational Infrastructure (technical professionals in engineering and architecture) or the Ministry of Health (health and safety requirements). The lack of a complete inventory that provides key information on schools including their location, the population attended or the state of the infrastructure (building and equipment), prevents a timely planning of interventions and efficient use of resources to address prior educational needs, with the risk of not acting on schools with the greatest vulnerability.

School infrastructure needs are important. Around one fifth of schools (874 out of 4335), enrolling 21% of the student population, had infrastructure maintenance needs in 2021 (e.g. poor conditions of water supply, electricity, sanitation facilities, sewage or structures damaged by weather conditions), despite efforts to improve school infrastructure conditions over 2014-19, with an average investment of 50 billion colones (0.125% of GDP 2021). Around 88% of classrooms in primary and secondary public schools were assessed as in good condition in 2020, an improvement with respect to 73% in 2014 but below the almost 100% of private schools (MPE, 2021[33]). In 2020, because of the pandemic, resources planned for public education infrastructure were cut by 14% (10 billion out of 72) leaving many schools initially planned to be renovated unattended. The budget for school maintenance in 2022 (CRC 11 billion) is insufficient to attend the extra costs for maintenance (estimated at CRC 310 billion). Following inspections from the Ministry of Health, around 20% of the schools in 2022 received a health and safety risk notice (orden sanitaria) for not meeting health and safety requirements for the life and physical integrity of students and staff. The estimated cost of the interventions required to restore health and safety standards in these schools amounts to CRC 298.5 billion (0.75% of GDP 2021).

Costa Rica would benefit from having a centralised and standardised system of information of infrastructure projects that could provide a timely picture of ongoing projects and their status. Currently, information is dispersed across different departments, is not standardised and often outdated, which makes impossible an effective control and use of effectively available resources for construction works (around 95 billion colones).

A more efficient management of school infrastructure could produce some savings. For example, around one third of the 1587 single-teacher schools could be merged into larger schools with adequate infrastructure, under the condition that a public transportation system for students were available (Sanchez, 2016[34]).

In Costa Rica 3189 out of 4763 school have internet connectivity but the bandwidth is insufficient to meet current and future schools needs. The 2018 project Red Educativa del Bicentenario aims to provide all schools with broadband connectivity, but it is progressing slowly. As of December 2021, broadband internet connectivity had been provided to 52 of the 4514 schools.

Following past OECD recommendations, a law proposal was presented aimed at introducing standardised rules, principles and methods for public investment projects with the greatest impact to apply to all public institutions except for non-state public entities and state-owned companies operating in competitive markets. The proposal should include a taxonomy of public investment projects, the requirement of performing a cost-benefit analysis of the project and the inclusion of environmental criteria. This reform could help reduce the time required to carry out investments and increase efficiency. Well-designed Public-Private Partnerships could also help to reduce infrastructure gaps (see Chapter 1).

Social dialogue between local actors and main stakeholders in education proved successful in providing connectivity infrastructure for households and schools in remote areas. In the canton of Santa Cruz a pilot project involving local authorities, SUTEL and Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE), reduced the time necessary to obtain the required permissions for connectivity infrastructure from 15 months to 15 days, also by creating a one-stop shop in the local government. The ongoing project will provide all schools and around 2300 households with children in the area with internet connection. This initiative could be scaled up throughout the country.

Making better use of digitalisation could help improve the quality and efficiency of the education system by easing the monitoring of students’ learning outcomes and of resource allocation. By integrating all data about students, schools and teachers, policymakers would have better information to design and target policy interventions, including providing support to vulnerable students and investing in infrastructure in underserved areas.

Costa Rica made progresses in the digitalisation of the education system with two digital platforms: SABER and SIRIMEP. The SABER platform aims at integrating all information of the educational system. It collects individual digital data of students and schools and it was key during the pandemic to help identify students suffering from technological exclusion and assess the state of internet connectivity in schools. The platform SIRIMEP leverages on SABER and was created during the COVID 19 pandemic as a short-term emergency tool to collect data on students’ performance, easing the monitoring of students’ progress. However, it suffers from operational problems and should be integrated with the unified system of the education system.

The General Comptroller (CGR, 2021[35]) detected weaknesses in the design of the platform SABER, including uncertainty about its funding, its scope and the exact timeline of its implementation as only three of eight phases have been implemented. Lack of integration with the ministry of education or academic management systems (virtual classrooms, virtual tools, collaboration, statistics, curricula, grades, evaluations), prevents early warning and analytical modules from producing the necessary input for decision-making. Ensuring the implementation of SABER is key to provide Costa Rica with a tool that would enhance the monitoring and assessment of students’ learning outcomes, guarantee more equity in education and an efficient allocation of resources.

Introducing national student standardised tests, joint with an efficient information system collecting data on the evolution of students’ performance, could help ensure continuity in the assessment of students’ performance to quickly detect weaknesses in the education system, elaborate evidence-based policy solutions and assess their effectiveness. For example, these tests could be especially useful in areas such as the assessment of foreign languages competences. These tests should be carefully designed as to avoid potential problems related to the limited scope of their assessment with respect to the number of subjects covered and depth of the assessment (Morris, 2011[36]). Teachers might also have incentives to focus their teaching on subjects and skills covered in the tests thus neglecting curriculum areas that are not assessed. Some of these issues could be minimised by careful design, such as including open-ended questions (written essays, oral communication and collaborative problem solving), as well as implementing other monitoring tools to better assess critical thinking, analytical or problem solving skills. Using standardised testing for diagnostic purposes only could reduce incentive to strategic behaviours on the part of schools and teachers.

Improving the quality of teachers is relevant for any level of education. Indeed, foundations built at an early stage shape students’ future performance, other than having an influence on their earning and employment trajectories.

Assessing motivation and pedagogical aptitudes of applicants to programmes in education would help select potentially high-quality teachers. Having completed secondary schooling is the only requirement to access programmes in education in private universities, while in public universities the access is conditional on obtaining a threshold score in the entry exam. An assessment of motivation and aptitude could be introduced in the entry exam for programmes in education in public universities.

There is also a need to better match the number of study places with the needs of the education system. While the overall supply of graduates in education grew faster than the demand for new teachers between 2007 and 2014, there is scarcity of teachers in specific areas such as preschool education, special education and English in primary schools. This occurs because graduates in education receive a specific training that depends on the level of education (preschool, primary or secondary) and the subject they will be teaching. The participation in a public competition for a specific teacher’s position is then limited to graduates with that specialisation. To reduce the observed imbalance between demand and supply, Costa Rica could consider the introduction of quotas in programmes of education where the supply is expected to remain above the demand in the short and medium term.

Modifications to the hiring system would make it possible to select the best teachers and reduce inefficiencies. The current recruiting system focuses mostly on observables such as experience and educational attainment, which are imperfect proxies of a teacher’s abilities. Costa Rica should implement promptly the eligibility test to select new teachers, as established by law in 2020 and in accordance with a 2012 ruling of the constitutional court that requires participants to public competitions to pass a test of knowledge (OECD, 2017[24]). Currently, such a test is required only for foreign language teaching positions (English and French). The introduction of a formal induction and probation period would also help ensure that initial teachers are supported at the beginning of their profession (OECD, 2017[24]).

The eligibility test could be designed in accordance with the standards that graduates in education should have at the end of their studies, as established in the 2022 National Qualification Framework for Tertiary Programmes in Education (Marco Nacional de Cualificaciones de las Carreras de Educación). The pass approval rate to the test could also give a signal about the quality of different tertiary programmes in education. This would push students to demand for quality programmes (PEN, 2018[37]) and provide universities with an incentive to revise their programmes according to the framework.

Almost all teachers have tertiary education in Costa Rica but the title by itself is not a guarantee of the quality of the training received, and evidence shows that programmes in education are heterogeneous in terms of content and quality (Badilla, 2016[38]). Universities may ask the National Accreditation System for Higher Education (Sistema Nacional de Acreditación de la Educación Superior, SINAES) to accredit their programmes to signal that they fulfil minimum standards of quality. However, accreditation is not compulsory and in practice very few programmes in education are accredited (13%, SINAES 2022), most of them offered by public universities (35 out of 44). Evidence from teachers’ quality assessments performed by the Ministry of Public Education (MPE) in English (2008 and 2015) and mathematics (2010) highlights that graduates from public universities tend to perform better than graduates from private universities (PEN, 2015[22]). However, the large majority of graduates in education are from private universities (around 70% over 2014-20). Moreover, few private universities currently offer to their students the possibility of engaging in teaching practices. Making teaching practices a part of the eligibility test for new teachers, or a compulsory requirement for the accreditation of any education degree, would push universities to widen their use.

The current recruiting system could be modified to provide a stronger incentive for students to attend accredited programmes. Public competitions for new teacher positions grant only two additional points to accredited programmes, out of a maximum score of 110. This is an insufficient incentive and students take into account other criteria than accreditation in choosing the programme to attend, such as a shorter duration (Lentini, 2017[39]). Making the accreditation of education programmes compulsory is an alternative venue to improve the preparation of future teachers (OECD, 2017[24]). The accreditation of a programme could be automatic when it is granted by an international recognised accreditation organisation.

Too many positions remain vacant at the end of each public competition, which points to inefficiencies in the recruiting system. Public competitions are commonly used by in-service teachers to move to a different school, which under current regulation is allowed for exceptional motives only (e.g. sickness). There is no penalty in refusing a place and in-service teachers can refuse it if it does not suit their preferences. Around four out of ten positions remained vacant in 2017 because they were refused (La Nación 2017). Vacancies are a cost for the Ministry of Public Education, which has to start a new hiring process, and for students, who risk not having a teacher at least for a part of the academic year. This system also makes it difficult to assign teachers to the schools that most need them. Costa Rica could improve the efficiency of the recruiting system by reducing the incentive for in-service teachers to use public competitions for mobility reasons. This could be achieved by modifying regulation to facilitate mobility of in-service teachers. Current financial incentives to encourage high value-added teachers to move to schools most in need could be strengthened (Box 2.6), though a pre-requisite for such incentives to be effective is a sound assessment system of teachers performance, possibly against measurable goals for each educational program.

In Australia, the High-Achieving Teachers programme, which began in 2020, provides alternative employment-based pathways into teaching for high-achieving individuals committed to pursuing a teaching career. Over three years, the programme will recruit 440 high-achieving university graduates with the knowledge, skills and experience that schools need. Participants are placed in teaching positions in Australian disadvantaged secondary schools with shortages of teachers. The goal is that students at disadvantaged schools will benefit when high-achieving university graduates, including those with a science, technology, engineering, and/or mathematics degree and those from a regional background, are recruited to teach at their school.

In Canada, an ECEC centre in North Winnipeg, which is targeted to children with multiple risk factors and is located at the heart of an impoverished, predominantly Indigenous community, actively recruits and trains local staff, resulting in lower turnover than would otherwise be the case and greater trust between parents and staff.

France created Priority Education Zones (ZEPs) with special resources aimed at disadvantaged schools. The main objective of the ZEPs is to decrease the differences in academic achievement between students with socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds and other students. To attract teachers to these schools, the government has introduced various incentives. New teachers starting at ZEP schools are able to draw on a network of education advisors and mentors to support them. Smaller class sizes (no more than 25 students per class) with more time for teamwork, resources for cultural and sports projects with students, and paid consultation time are also meant to attract teachers to these schools. There are also bonus schemes with an annual premium of EUR 1 734 gross for teachers in schools in which 55% of the students belong to the least favoured socio-economic categories, and EUR 2 312 gross for those teachers in schools in which 70% of the students belong to the least favoured socio-economic categories.

In Spain, a credit system allows teachers working in more disadvantaged and diverse school settings in particular regions to obtain extra credits. These credits can be used to gain promotions, choose to move to another school and obtain a salary increase after six years.

Since the 1999-2000 school years, the state of Washington has awarded salary incentives for National Board Certified Teachers (NBCTs) in high-need schools. In 2007, Washington also introduced an additional bonus for teachers in high poverty schools. During the first year of the new bonus programme, the number of NBCTs in Washington increased by 88%. By 2013, the gap in board certification between low- and high poverty schools had not only decreased but reversed.

Strengthening teachers’ in-service training in terms of access, coverage and quality of training could help increase the quality of the education system in Costa Rica. It would also reduce inequality of opportunity in education.

A poor students’ performance in reading skills highlights that more teachers could benefit from in-service training to acquire pedagogical skills and teaching practices that improve students’ reading habits, such as asking students to read long and complex texts and using different types of texts (fictions, digital texts, charts, tables) in class (Barquero, 2021[44]; Reimers, 2008[45]). Preschool teachers, instead, could receive specific training to promote the early development of literacy and language skills through the use of best practices such as shared reading, increasing children’s vocabulary and better attend to the needs of students with difficulties in oral communication (PEN, 2019[46]). Reading skills affect lifelong learning ability, and gaps in reading skills developed at an early age produce a persistent effect and perpetuate inequality. Strengthening reading skills of disadvantaged groups from an early age should be a priority for Costa Rica.

To make the change in the curriculum effective, more teachers could receive adequate training, and support by consultants or experienced peers, as to help them implement the new curriculum in class. Indeed, many teachers felt unprepared to apply the new teaching practices and continued to use traditional ones (PEN, 2018[37]). The introduction of a Teacher Mentoring Strategy in topics related to learning to read and write for primary school teacher from grade 1 to 3 is a welcome initiative.

Providing quality in-service training could help improve learning outcomes in mathematics and sciences. Theory and evidence highlight that inquiry learning is more effective than the traditional teacher-centred deductive approach in developing students’ scientific literacy, problem solving and cognitive skills (Cairns, 2019[47]). Training could then contribute to extend the use of the inquiry learning approach in science education.

Integrating IT technology in the education system has the potential to improve its coverage and quality, to facilitate the teachers’ professional development and help the learning process of students (Minea-Pic, 2020[48]). Recent initiatives have increased the supply of training for teachers in the use of IT for pedagogical purposes, including a variety of courses offered virtually. During the COVID 19 crisis almost all teachers received virtual training on how to teach in a digital learning environment (e.g. creating a collaborative classroom or connect in professional learning communities) and, in 2021, around 2000 teachers participated to the Teacher Update Webinar Program aimed to develop digital and pedagogical competencies using Microsoft Teams. Costa Rica could nevertheless expand training in IT for pedagogical purposes and in developing digital didactic material (Zúñiga, 2021[26]). Including these trainings also in tertiary programmes in education could help more teachers have strong digital skills and the ability to use them effectively.

Despite the potential benefits of receiving in-service training, few teachers in Costa Rica use it. A 2015 survey found that only around 40% of the teachers surveyed had received professional training in the past year (PEN, 2021[13]), and around 80% of teachers had received in-service training between 2019 and 2021 (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo y de Inversión Pública 2019-2022). These numbers are low if compared to international experience, as according to OECD assessments around 94% of teachers in 31 countries in 2018 participated in at least one professional development activity in the previous year (OECD, 2019[49]). Moreover, post-training in class support is also weak in Costa Rica, as it available only for 30% of the trainings (PEN, 2021[13]). Post-training in-class support should be strengthened. Finally, the diffusion of the benefits of training to other teachers is also limited.

Despite access to training is available all over the year, it is concentrated at the end of the academic year to not interrupt the educational process. Access to training could be enhanced by making training more easily accessible all year long at least to a part of the teachers, thus accelerating the update of the teaching staff. Some of the teachers receiving training could be temporarily replaced by support teachers or graduates in education with the benefit that these would acquire teaching practice. A larger use of virtual training might also increase access to training and reduce its cost.

Better assessment of the results of teachers’ training is needed. The Institute for Professional Development Uladislao Gámez Solano (UGS) is charged with the implementation of the 2016 National Plan for Continuous Training “Actualizándonos” (Plan Nacional de Formación Permanente) which aims to strengthen the teachers’ training system. However, the UGS is understaffed to properly assess the outcome of training. Its monitoring and assessment department employs only nine people compared to the 80000 employees in the Ministry of Public Education. Given this limitations, the UGS evaluates the relevance, effectiveness and short-term impact of the training activities by asking training participants to assess how satisfied they are with the training received as well as providing an evaluation of the learning achieved and its applicability.

The current system for assessing teachers’ quality does not create adequate incentives for principals and teaching staff to engage in a continuous process of improving the quality of the educational services they provide. The periodic report sent by the Ministry of Public Education to schools’ principals, which highlights the weaknesses of their students on the basis of the results in national standardised exams, is rarely used as an input to take concrete actions (PEN, 2018[37]).

The yearly teachers’ assessment prepared by school principals is ineffective in supporting a continuous improvement in teaching efforts. School principals restrain from signalling teachers’ weakness to not deteriorate the relationship with the staff members (PEN, 2018[37]). Thus, almost all teachers receive a positive evaluation (99.7% in 2016). The Ministry of Public Education could increase the use of assessment tests of teachers’ knowledge and use results for designing new training programmes. These tests are rarely used but helped improve the quality of English teachers in the past.

Following past OECD recommendations (OECD, 2017[24]) Costa Rica is developing a framework for the assessment of the quality of education that has to be presented for approval to the Higher Council of Education (Consejo Superior de Educación, CSE). The framework will indicate what tasks and evidence should be considered for teachers’ assessment, as well as provide guidance on how to give teachers feedback and provide support. Costa Rica has joined in 2021 the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) to strengthen the monitoring of teaching quality in the educational system.

The management of public funding by Education and Administrative Boards (Box 2.7) (Juntas Administrativas and Juntas de Educación, EAEs) shows inefficiencies and lack accountability and transparency. The members of the EAEs do not always have the competencies that are necessary to carry out administrative tasks, such as the knowledge of relevant regulation, which causes an inefficient use of public resources. This is especially relevant in areas with indigenous communities where the members of the EAEs rarely receive training or supervision by the Ministry of Public Education nor official documentation that is translated into indigenous language.

The activity of the administrative boards is often hampered by municipalities that delay the appointment or the dismissal of their members or do not follow legal procedures thus opening up legal contentious, with repercussion on the continuity in the provision of education services. A reform of the regulation of the boards could help prevent the inaction of local municipalities from paralyzing the activity of EAEs. Reforming the minimum requirements of EAEs’ members and ensuring that they receive an adequate training to fulfil their role could help improve their efficiency.

Education and administrative boards (Juntas Administrativas and Juntas de Educación, EAEs) are decentralized entities with legal personality and own assets that by law are tasked with guaranteeing the right to education and to establish a link between the school and the local community. In coordination with the school principal and teachers, EAEs manage the public funds received from the Ministry of Public Education (MPE) to provide schools with the goods (e.g. food, technical equipment or teaching material) and the services (e.g. transportation, and canteen services, technical support, payment of basic services) that they need as to guarantee the right to education. The members of the EAEs are appointed by the Municipal Council, must meet requirements set by law and should receive an adequate training to fulfill their role provided by the Ministry of Public Education. EAEs are obliged by law to use the Single System of Public Purchases (SICOP) when purchasing goods and, limitedly to the purchase of food supply, they are compelled to buy from the National Production Council (Consejo Nacional de Producción, CNP). EAEs must submit every year a budget accountability report that respect predefined accounting standards. In areas with indigenous communities the EAEs integrate a Local Indigenous Council made of members of the indigenous community.

Financial controls over EAEs budgets are weak and overall it lacks a systematic supervision at the regional and national level, thus hindering a clear picture of the overall efficiency of the EAEs. The quarterly reports that EAEs must submit to regional Directorates often do not respect the required standards, or are submitted late and the Ministry of Public Education rarely orders external audits on EAEs budget report. A regulatory reform of the EAEs governance could help increase their accountability and transparency, also by digitalising budget procedures to ensure the respect of standards. A more frequent use of the power to order external audits could also help boost budget transparency of EAEs.

Evidence shows that the obligation that food purchases from the EAEs must pass through the National Production Council (Consejo Nacional de Producción, CNP) results in paying higher prices than if EAEs could operate freely in the market. Changing this regulation that de-facto assigns monopoly power to the CNP would permit EAEs to achieve large savings. Also, more EAEs should implement school orchards to promote their potential in supplying school canteen.

In Costa Rica, the constitution mandates a target budget for education of 8% of GDP, and significant resources have been allocated to education and training over time. However, large and increasing government deficits have raised the level of debt that is currently close to 70% of GDP (Chapter 1), implying that the fiscal rule will be containing spending in education in the next years (Figure 2.12). Against this background, Costa Rica has to prioritise its education spending and also address the learning losses suffered in recent years to avoid long-lasting scarring effects.

Overall spending on education has fallen in recent years, but it has fallen the least in tertiary education (Figure 2.13, Panel B) education. Moreover, current spending per student is the highest in tertiary education, around four times that in primary, secondary or preschool (Figure 2.13, Panel A). This is much higher than in the average OECD country, where total expenditure per student in tertiary education is around 1.7 times than in primary, secondary and post-secondary vocational non-tertiary (OECD, 2021[50]). Such a regressive spending structure needs to change and spending should be reprioritised towards earlier levels of education, as investment in these areas produce positive long-term economic and social benefits that are far higher than the initial cost (Psacharopoulos, 2018[51]; OECD, 2017[52]).

Addressing changes in spending needs due to low fertility rates require careful long-term planning. Smaller cohorts will lead to a gradual decline in the number of students in education. At the same time, enrolment rates in secondary and tertiary education are likely to increase, as they are currently low.

Spending containment measures should focus on current spending, as large increases in spending in the past did not lead to a substantial improvement in education infrastructure. Savings could be obtained by making a more efficient use of resources. For example, reducing grade repetition, which is high in secondary school in Costa Rica (above 10% on average between 2010 and 2018) and costly (4% of total spending in primary and secondary education for the average OECD country) could help (OECD, 2012[53]). The digitalisation of education might increase spending efficiency, for instance, by providing a clearer map of the distribution of teachers and students over the country, which would help avoid misallocating the teaching staff that causes schools to be under- or overstaffed. Digitalisation could also help reduce overreporting in the number of students in schools, which currently leads to larger than needed transfers.

Note: Between 2010 and 2022 the budget allocated to the Special Fund for Higher Education (FEES) grew by 2.5 times in nominal terms.

Source: PEN 2021.

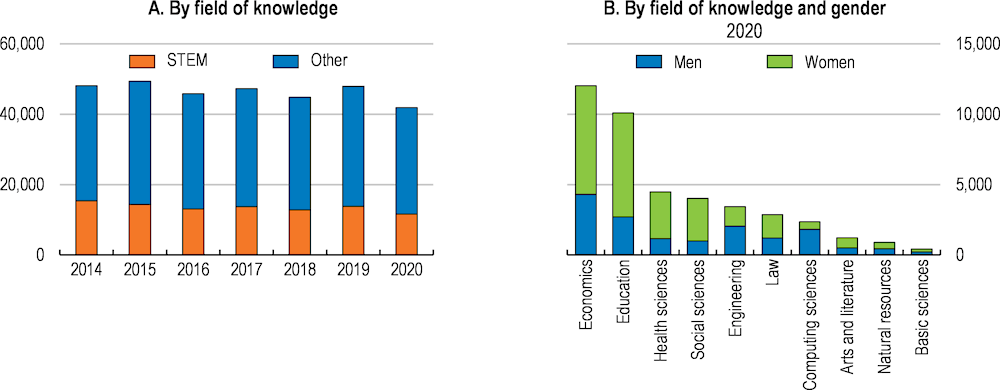

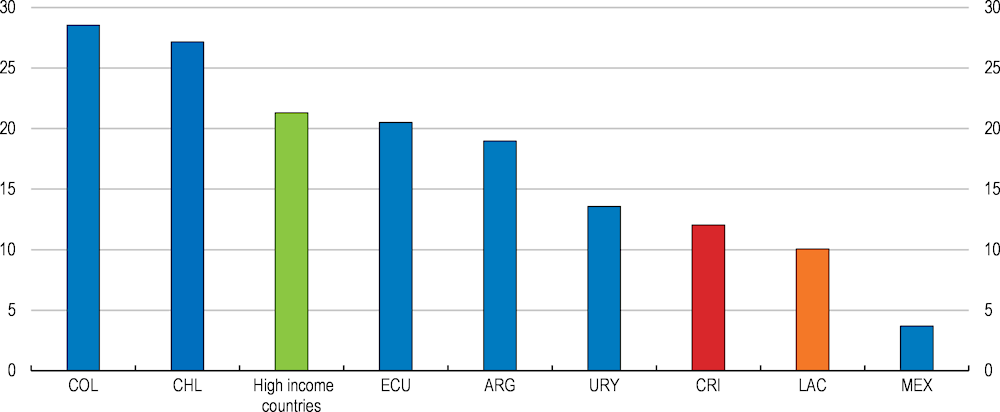

The rate of higher education attainment has increased over the last decade. The proportion of young adults with higher education is higher than in some peer countries in the region such as Brazil, Argentina and Mexico, but still below the OECD average (Figure 2.14). However, the absolute number of degrees awarded by Costa Rican higher education institutions has stalled in recent years (Figure 2.15, Panel A). This is partially due to a high average time to graduation, favoured by the possibility of taking the same exam without penalty several times, the presence of students being enrolled in multiple degrees and the reduction in the number of graduates from private universities, and because there is no further room for an increase in the enrolment rate in tertiary education of students from advantaged socioeconomic groups, which was a major factor in the overall increase in the number of tertiary graduates in past years, having their enrolment rate already reached a very high level (Figure 2.18).

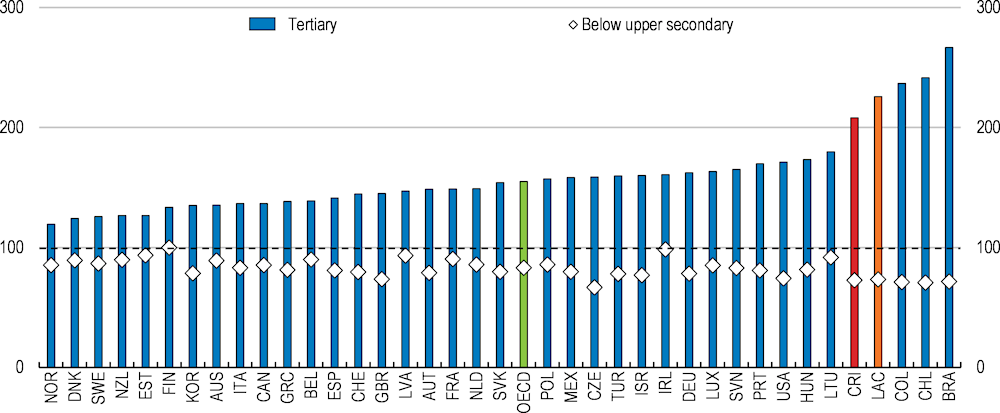

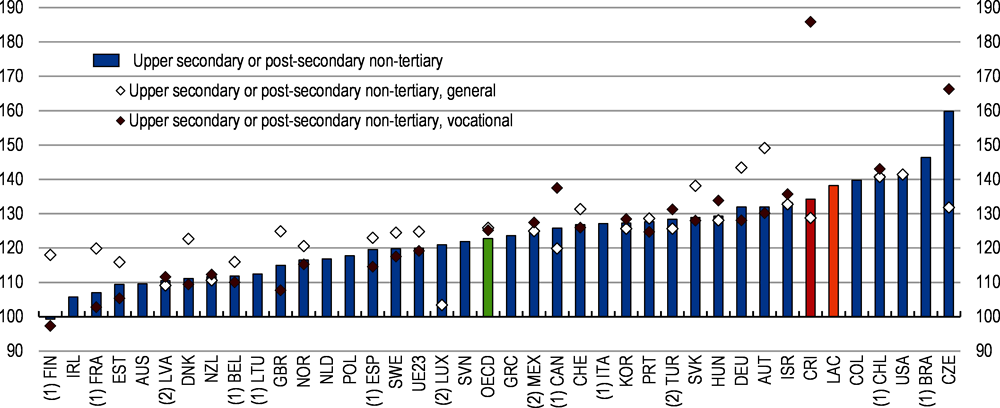

The stall in the supply of tertiary graduates contrasts with a relatively high demand for them, which translates into strong labour and economic returns to tertiary education in Costa Rica. Around one third of the jobs demanded by the private sector are for profiles requiring higher education in fields such as administration (40%), sciences and engineering (27%), education (12%) and telecommunication (8.2%) (CONAPE, 2021[54]). Tertiary graduates have the highest employment rate at around 70% (Figure 2.16, Panel A), and tertiary education provides access to formal jobs that are more resilient to economic fluctuations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the reduction in employment and labour market participation rate of people with tertiary education was lower than for population with lower levels of qualification (Figure 2.16, Panel B). Earning advantages gained from obtaining tertiary education in Costa Rica are the fourth highest among OECD countries (Figure 2.17).

Percentage of 25-34 year-olds with tertiary education as the highest level attained

Note: LAC refers to Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil.

Source: OECD Education Database.

Total degrees awarded by field of knowledge and gender

Note: The chart report all degrees provided by the five public and 51 private higher education institutes and include all tertiary education qualification levels from ISCED 5 (short-cycle tertiary education) to ISCED 8 (PhD).

Source: HIPATIA Dataset.

Improving spending efficiency on tertiary education is key for Costa Rica to boost tertiary graduation rates in an environment of limited fiscal space. Moreover, to increase secondary students’ graduation rates and level of preparation, which is a prerequisite for increasing the demand for tertiary education, Costa Rica would benefit from reorienting spending on education towards pre-tertiary levels.

Relative earnings of workers, by educational attainment, 25-64 year-olds with income from employment (full-time full-year workers); upper secondary attainment = 100, 2020 or latest year

Note: LAC refers to Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil.

Source: OECD (2022), Education at a Glance.

Access to tertiary education is positively correlated with socioeconomic conditions, and the net enrolment rate in tertiary education of families in the top income quintile is around ten times as high as that of families in the bottom income quintile (Figure 2.18). These inequalities are persistent, and in the past decade the increase in the net enrolment rate of top income households was twice that of bottom income households.

Net enrolment rate in tertiary education, by income quintile, %

To continue increasing the share of youth with tertiary education, efforts must be focused on extending access to students with a more vulnerable background, who are currently less likely to complete upper secondary school, tend to have a worse preparation for higher education or lack financial resources to engage in tertiary studies. Improving the quality of education at earlier levels of education and reducing further exclusion in secondary education, are critical pre-requisites for increasing demand for higher education and equality of opportunities in education in Costa Rica.

Educational losses suffered by younger cohorts in recent years are more likely to affect students from vulnerable groups and represent a further challenge to the goal of increasing enrolment in higher education. Strengthening student support services through orientation, mentorship and levelling classes during primary and secondary school would reduce these losses and increase future demand for higher education.

Lack of funding and information about funding, hinder access to university to more vulnerable groups. Social spending (grants and social aids) that increases equality of opportunity in education should not be reduced despite the limited fiscal space. Costa Rica should improve the targeting of its funding system to increase tertiary education attendance of students with potential and from a vulnerable background who may be unaware of available funding and of the returns of tertiary education, especially in rural areas. Student loans for higher education from CONAPE have been decreasing since 2013, while potential beneficiaries have increased. The use of government-backed student loans, with repayment terms based on future income, could be expanded for students with a middle-class background. This policy would imply very low fiscal risk given the high economic returns of tertiary education, and could be used to promote enrolment in fields of national interest such as STEM areas. A pilot project providing loans that do not require any collateral for students at the Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica could be extended to other universities. Reducing the time required for graduating in public universities in some fields in which it is longer than in private universities (e.g. degrees in education), but without reducing the quality of education, could reduce the opportunity cost of attending tertiary education and increase demand.

Graduation rates need to improve especially in sciences, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields. Even though the number of graduates remained stable or even increased in most STEM areas between 2015 and 2019, the share of STEM graduates remains low and below the OECD average (Figure 2.19) when all levels of higher education are taken into account (short-cycle tertiary, bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees). Increasing the share of graduates in STEM would help respond to the needs of the private sector, whose demand in fields such as telecommunications or integration of automatized systems in the production process is not satisfied by the current supply. Overall, information and telecommunications (IT) and engineering are among the fields providing the most opportunities to work in the private sector, while most graduates in education and, to a lesser extent, in health sciences are employed in the public sector (Figure 2.20), whose demand will be contained in the coming years.

In most STEM areas but medical sciences, where the number of women surpassed that of men in 2013, mostly due to nursing (Durán-Monge, 2022[55]), the gender gap in tertiary education has persisted or grown (telecommunications), and on average over 2014-20 the number of male graduates is twice that of female graduates. Exposing young girls to STEM fields and encouraging those who are interested to study scientific areas would help increase the number of women in STEM areas. Administrators and educators should create environments that correct existing negative perceptions that young girls may develop towards scientific disciplines. Mentorship programmes and highlighting of eminent women in the STEM industry may boost girls’ confidence in pursuing their studies in scientific fields. In France, a mentoring programme for female PhD students was established in 2015 to provide career guidance and help them gain confidence and nurture their ability to value their skills (Morris, 2021[56]). In 2021, the programme involved 100 mentors from three universities. In the United States, since 2008, the Massachusetts chapter of the Association for Women in Science (MASS-AWIS) has organised a Mentoring Circle programme geared towards junior scientists from academia and industry to receive advice, support and information from experienced mentors (Fridkis-Hareli, 2011[57]).

Tertiary graduates in STEM, % of all graduates, 2021 or latest year

Note: The distribution of graduates by field of study is calculated as the share of graduates from each field over the total of graduates. STEM includes all graduates (short-cycle tertiary, bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees) with a degree in natural sciences, mathematics and statistics; information and communication technologies; and engineering, manufacturing and construction. LAC refers to Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil.

Source: OECD (2022), Education at a Glance.

Sector of employment of people with tertiary education three years after finalising their studies, 2019

Promoting innovations in higher education could also help increase the quality and the attractiveness of STEM fields. This could materialise through the integration of advances in knowledge and technology into new courses and degrees, more and higher-quality research, and a tighter relationship between higher education institutions and society and businesses. The connection with the business sector is key as the private sector demand for skills should feed back into the supply of tertiary educational services. Regulation is a major obstacle to the creation of new courses or degrees. In private universities, the authorization process is slow and cumbersome, with a high volume of requirements and standards to be met, and the discretionary power held by the CONESUP makes it uncertain. In public universities, the main obstacle to innovation is a long and complex decision-making process in which many players may use a veto power. Streamlining regulation in public and private universities would facilitate the opening of new courses and programmes, also in hybrid or distance modes, while preserving their quality.