The Finnish economy recovered rapidly from the pandemic but now faces deteriorating global conditions, especially since Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Inflation has soared, reducing disposable incomes, exports have weakened and the investment environment has become less favourable. Finland is well placed to cope with the loss of energy supplies from Russia, although replacing gas in industrial uses with other energy sources will take time. Monetary conditions are becoming less accommodative and the structural budget deficit has increased, mainly owing to expenditures related to the Russia’s war against Ukraine. Fiscal consolidation is required to meet Finland’s medium-term objective and to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio over the longer run. To close the gap in living standards with the other Nordics, reforms are needed to boost productivity growth, especially to strengthen innovation, and to raise the employment rate. Finland is on track to meet its gross greenhouse gas emissions abatement objectives, but not the forestry and other land-use sink targets needed to meet the 2030 EU effort-sharing target for this sector and the 2035 net zero emissions target stipulated in the Climate Change Act. There is considerable scope to increase the efficiency of greenhouse gas emissions abatement measures.

OECD Economic Surveys: Finland 2022

1. Key policy insights

Abstract

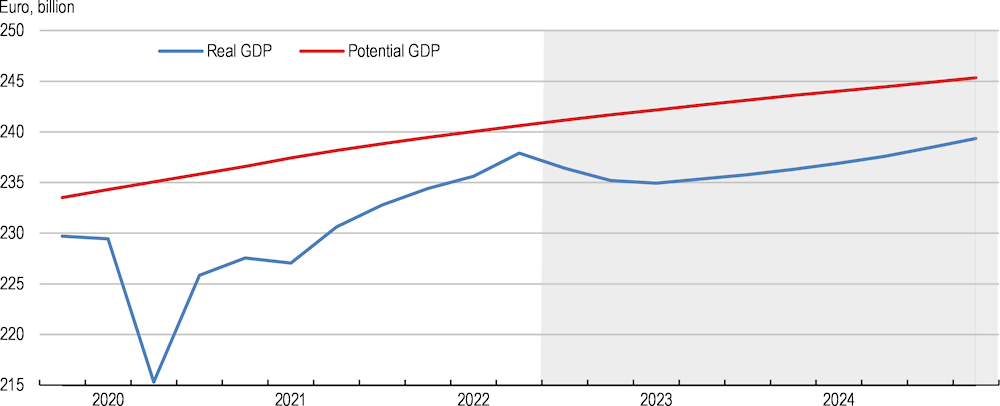

Finland had recovered from the COVID-19 shock by the second quarter of 2021 and was enjoying solid economic growth before Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. However, rising energy prices from late 2021 as the global recovery from the COVID shock gathered pace began to weigh on the recovery in Finland and other energy importers. Russia’s war against Ukraine caused energy and other commodity prices to soar, slowing the economies in Finland and its main trading partners (Box 1.1). Finland has taken a greater hit from shrinking exports to Russia than most other EU countries, despite such exports having already fallen to a small share of total exports before the war began, following years of sanctions since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. Output is expected to remain well below its potential level in 2024.

Box 1.1. Key features of the Finnish economy

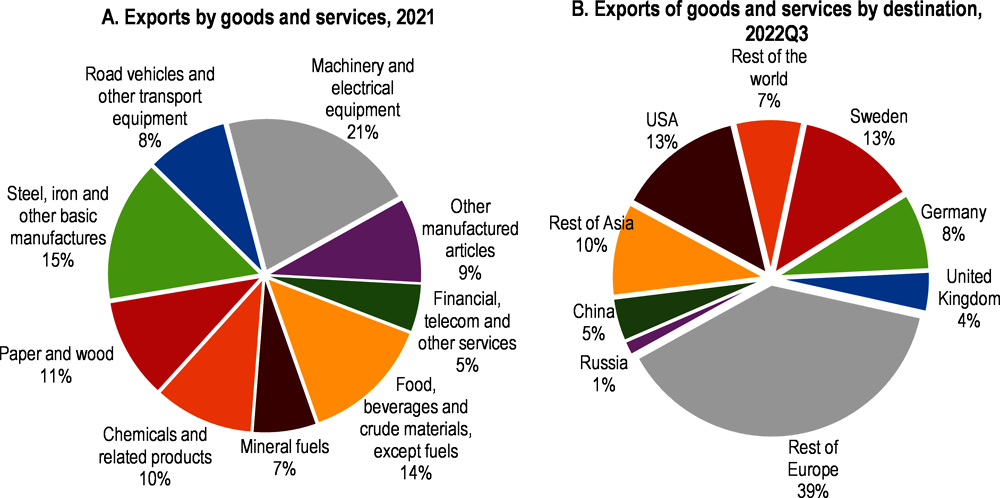

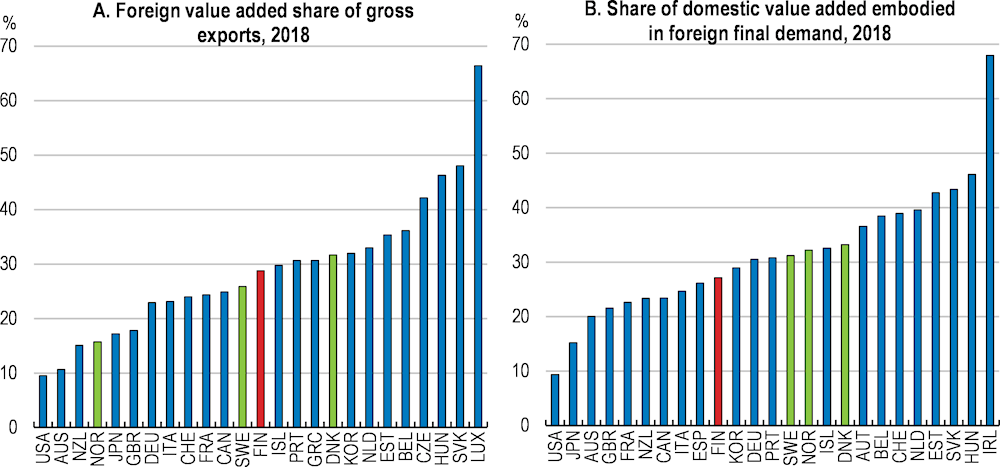

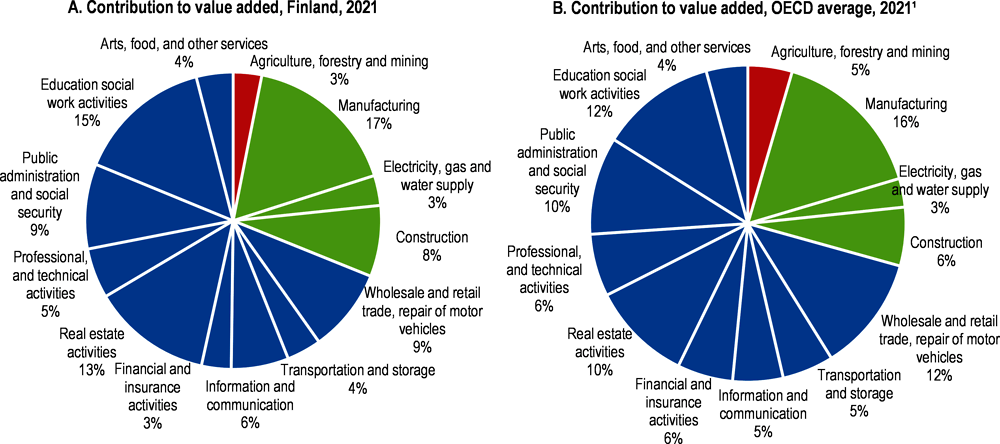

Finland has a small population (5.5 million) but a land mass (338 000 square kilometres) that is almost as big as Germany’s. It shares a 1 340-kilometre land border with Russia. Services account for 70% of value added, close to the OECD average (Figure 1.1). The largest service sectors are education and social work activities, real estate activities and wholesale and retail trade. In manufacturing, which accounts for the same share of value added as the OECD average, the largest sectors are wood and paper products, and manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products. Finland’s largest categories of exports are machinery and electrical equipment, and steel, iron and other basic manufactures (Figure 1.2, Panel A). Finland is highly dependent on European export markets – almost two-thirds of exports are to EU countries, with the largest shares going to Sweden and Germany (Figure 1.2, Panel B). Russia only accounts for a small share of Finnish exports. The export ratio (38%) in Finland is lower than in the other Nordics and similar-sized European countries (Figure 1.3), partly reflecting trade sanctions on Russia and low inward foreign direct investment (OECD, 2017). Finland is well integrated in global value chains in terms of the use of imported inputs in its exports (Figure 1.4, Panel A), but not so much as a provider of inputs to other countries’ production to meet final demand (Figure 1.4, Panel B), which may be an advantage in the short run even though it holds back productivity in the long run.

Figure 1.1. The structure of the Finnish economy is similar to the OECD average

1. 2020 data for Canada, Chile, Iceland, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and United Kingdom.

Note: Shares may not add up to 100% owing to rounding. Service sectors are shown in blue.

Source: OECD (2022), National Accounts (database).

Figure 1.2. The largest export categories are machinery and basic manufactures and EU countries the largest export markets

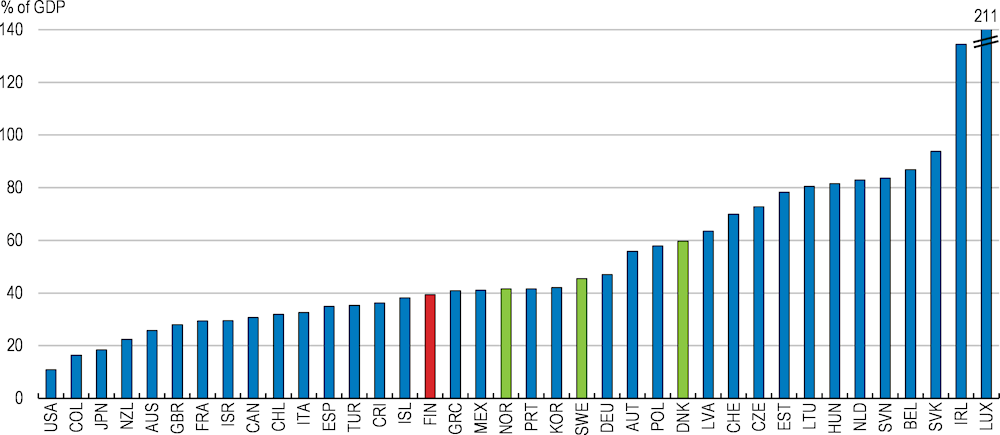

Figure 1.3. Finland’s export intensity is low for a small EU country

Exports of goods and services, 2021

Source: Source: OECD (2022), Trade in goods and services (indicator). doi: 10.1787/0fe445d9-en, 2022.

Figure 1.4. Finland is not highly integrated in global value chains

Following Finland’s application in May 2022 to join NATO, Russia terminated gas and electricity exports to Finland. While most gas was imported from Russia, gas only represents 5% of total energy consumption (Box 1.2) and plans are advanced for sourcing it elsewhere, in LNG form. Additional electricity from local sources and from Sweden and Baltic countries has replaced imports of electricity from Russia, which represented 10% of electricity consumption. The new nuclear power plant will supply 14% of Finland’s electricity when it reaches normal operating capacity in winter 2022-23. Oil imports from Russia fell sharply following the beginning of the war and ended in July. Finland is well advanced on the transition away from fossil fuels, with renewables already a larger source of energy.

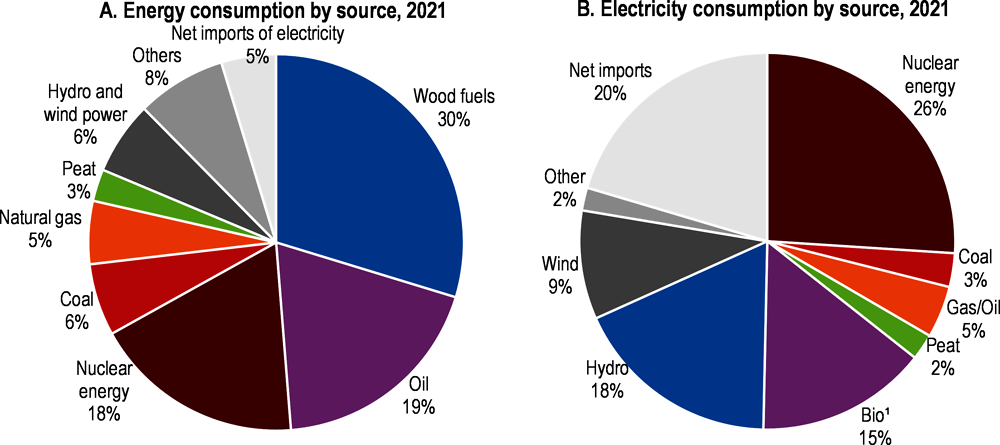

Box 1.2. Energy sources and security in Finland

The largest energy sources in Finland are wood fuels, oil and nuclear (Figure 1.5, Panel A). The use of wood fuels in heat and power plants is mainly based on the use of by-products from the forest industry. These products account for more than 70% of renewable energy production. Renewable energy sources accounted for 42% of total energy consumed in 2021, exceeding fossil and peat sources (34%) for the first time. Natural gas only accounts for 5% of energy consumption, much less than in most other European countries. It is mainly used in industry and district heating production, not in property-specific heating as in most other European countries. Coal is declining as an energy source and will be banned by law after the winter of 2029.

Finland's electricity supply is diverse in terms of both energy sources and production technology. About 85% of electricity production is emissions-free (Figure 1.5, Panel B). In 2021, more than half of Finland's electricity production was generated with renewable energy sources with nuclear power accounting for a further 32%. Fossil fuels and peat accounted for 14% of electricity production. The share of electricity imports has been quite high (around 20% on average) in recent years. Electricity is imported (on a net basis) from the Nordic countries and, until May, was also imported from Russia. The bringing on stream of the Olkiluoto 3 nuclear power plant (it has been functioning on a trial basis since March 2022 with steadily rising production), which will account for 14% of Finland’s electricity consumption when it reaches full operating capacity in winter 2022-23, and additional construction of wind power, which is competitive despite not being subsidised, will drastically reduce the share of imports.

Figure 1.5. Renewables are a larger energy source than fossil fuels

1. Bio includes black liquor, other wood fuels and other renewables.

Source: Statistics Finland.

Breaking away from Russian energy

The European Council has called for an end to dependence on imports of Russian gas, oil and coal as soon as possible. It prohibited coal imports from Russia from August 2022 and set deadlines for ending oil and gas imports of end-2022 and 2027, respectively. To meet these deadlines and in addition to the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 legislative package (European Commission, 2022[1]), the European Commission has published the REPowerEU Plan, setting out the EU’s strategy to move away from Russian fossil fuels, become more self-sufficient in energy and speed up the clean energy transition. The REPowerEU Plan is based on three pillars: diversification of natural gas supplies and common purchases of natural gas, LNG and later hydrogen via the EU Energy Platform; boosting energy efficiency and energy savings; and accelerating the deployment of renewables. Member states are expected to include in their updated Recovery and Resilience Plans a new REPowerEU chapter that will include reforms and investments to help achieve the REPowerEU objectives. Russia has accelerated the phasing out of EU gas imports by cutting off supplies to a growing number of countries and severely restricting supplies to others.

Oil and coal are global fuels with multiple sources of supply. Several Finnish companies have announced that they are rapidly changing their sources of supply. There are mandatory storage arrangements for oil and natural gas.

Regarding natural gas, the situation is still challenging, even though natural gas accounts for only 5% of Finland's total energy consumption. The Balticconnector pipeline, which was opened two years ago, will provide an alternative source of gas supply through the Baltics. The liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure is being expanded: Gasgrid Finland Oy and US-based Excelerate Energy, Inc. signed a ten-year lease agreement for the LNG terminal ship Exemplar (with a capacity of 151 000 cubic metres of LNG) in May 2022, which will be operational by end-2022. Moreover, this infrastructure can be used more efficiently. However, these sources do not cover the entire demand for natural gas. While the manufacturing sector has made progress in replacing natural gas with other materials, replacing all natural gas used by industry is challenging in the short term.

The cessation of electricity imports from Russia in May 2022 has increased the price of electricity in Finland by approximately 4-5 EUR / MWh; the imported Russian electricity was relatively cheap, being produced in coal-fired power stations not subject to emissions pricing.

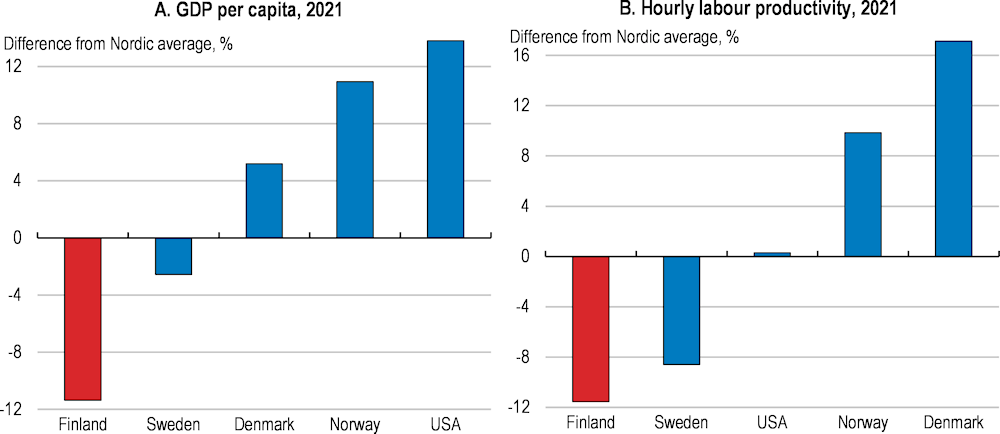

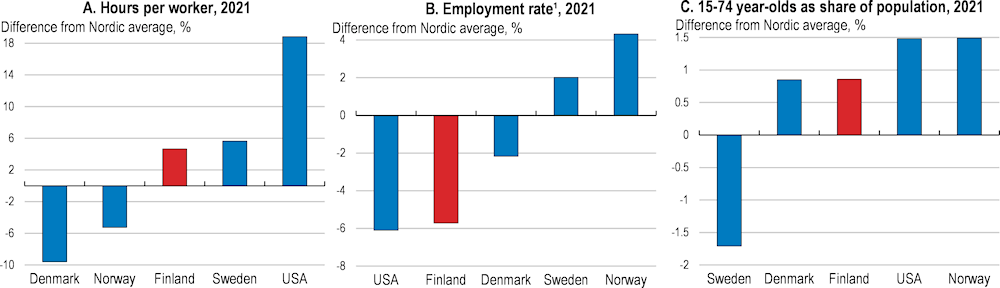

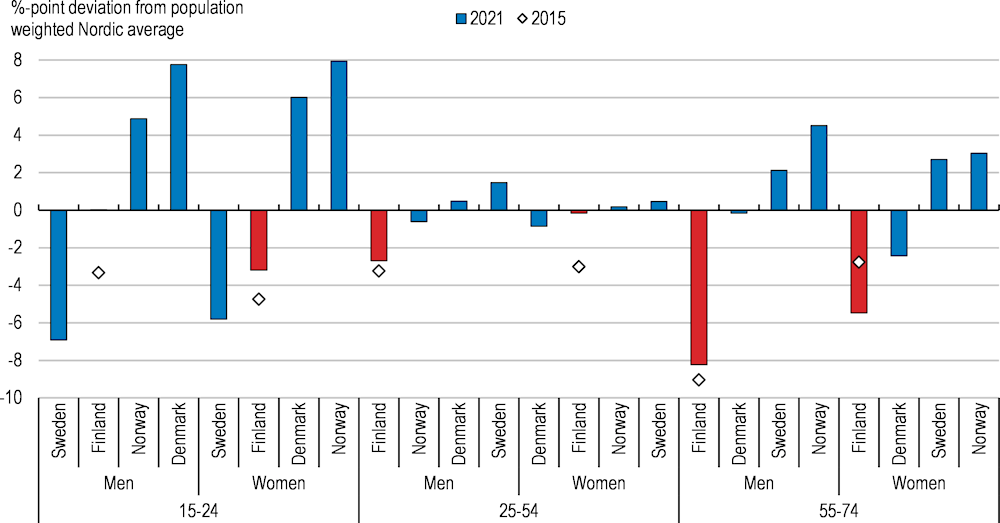

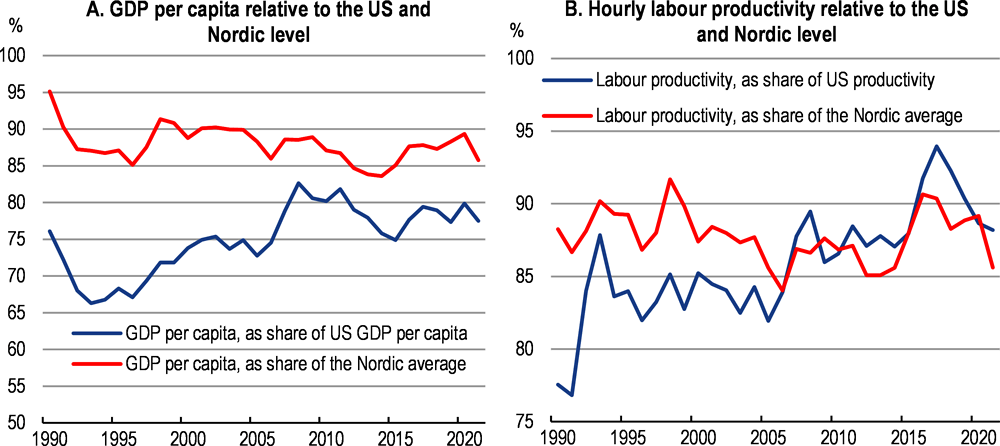

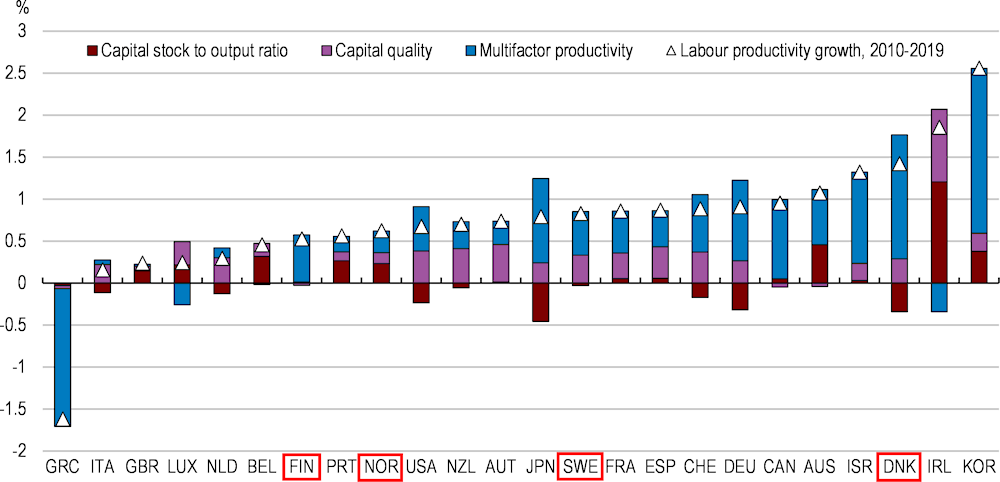

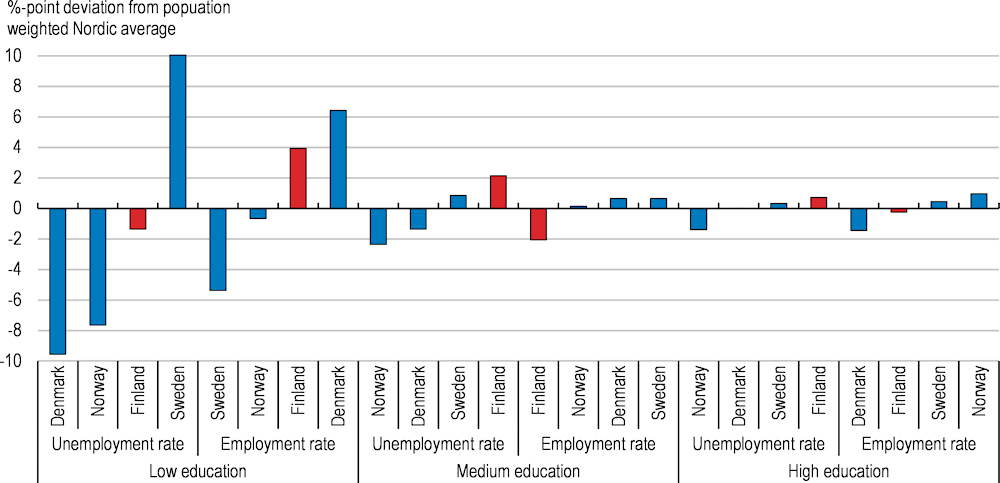

Following a sharp fall in the early 1990s, GDP per capita (at PPP exchange rates) increased to around 80% of the US level (a proxy for the population-weighted upper half of the OECD) in the late 2000s, where it remains today (Figure 1.6 and Figure 1.7). This increase was entirely explained by faster productivity growth in Finland than the United States, which lifted Finnish productivity to a little over 90% of the US level in recent years. GDP per capita and labour productivity have remained around 10% below the Nordic (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden here and in the rest of the Survey) average in recent decades. High skills shortages, low investment and resource misallocation have prevented Finland from closing this productivity gap. Annual hours per worker and the share of the working-age population in the total population are higher in Finland than the Nordic average, pushing up GDP per capita relative the Nordic average, but the employment rate is lower, with the opposite effect (Figure 1.8). Key reforms and policy announcements since the 2020 Survey are dominated by labour market reforms aimed at reducing unemployment and increasing the employment rate (Box 1.3).

Figure 1.6. GDP per capita and labour productivity have increased relative to the US level but not relative to the Nordic average

1. At current PPP exchange rates.

2. The Nordic average is population weighted.

Source: OECD (2022), Economic Outlook (database).

Figure 1.7. GDP per capita and labour productivity are below the Nordic average

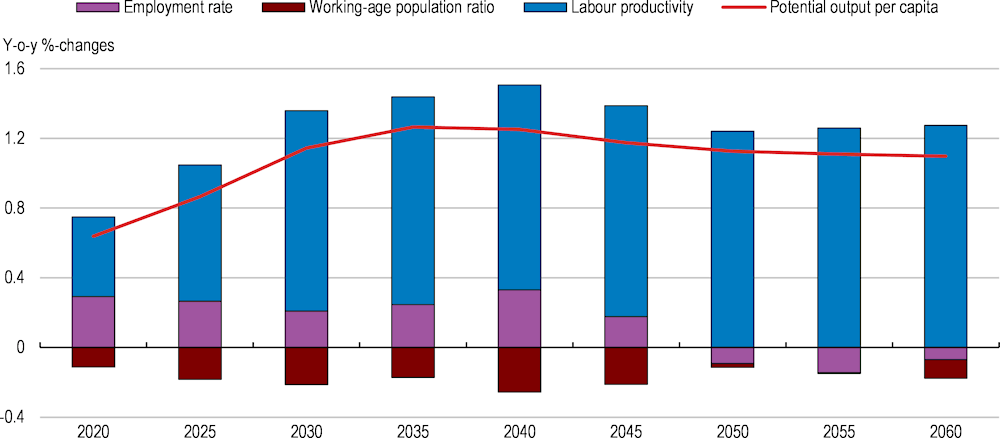

Population ageing weighs on long-term growth prospects. In the OECD’s latest long-term projection, the combined effects of slowing growth in the employment rate and a falling working-age-to-population ratio reduce the growth in potential output per capita from around 1.3% in the mid-2030s to 1.1% from the late 2040s onwards (Figure 1.9). These rates are close to those projected by the Bank of Finland (in the baseline scenario, falling from 1.3% in the mid-2030s to 1.0% in the 2050s) but lower than projected by the Ministry of Finance (rising from 1.4% in the 2030s to 1.6% in the 2050s), which assumes higher labour productivity growth than either the OECD or the Bank of Finland.

Figure 1.8. Hours per worker are higher than the Nordic average and demographics are more favourable, but the employment rate is lower

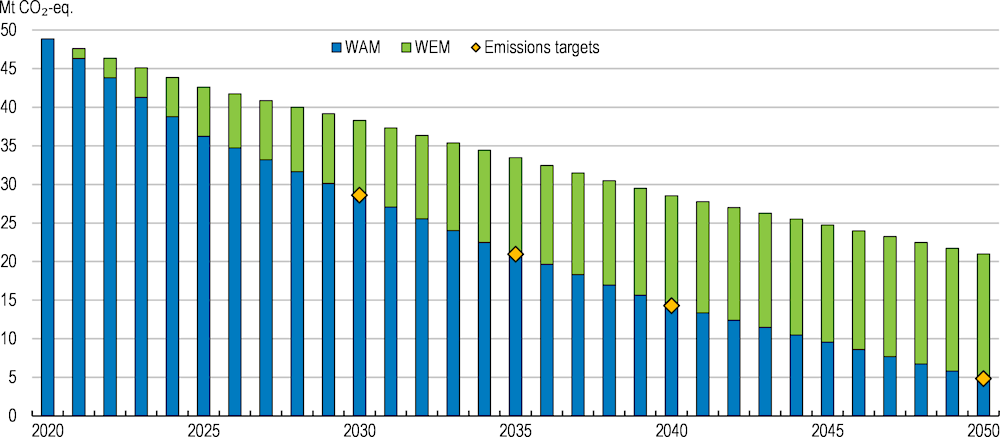

Finland has reduced gross greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 33% since 1990 compared with an OECD average of 6%, to per capita levels that are 18% below the OECD average, and further substantial reductions are in prospect (Figure 1.10). It achieved its 2020 EU effort-sharing abatement target (covering non-EU Emission-Trading-Scheme sectors and excluding the forestry and other land use sectors) of 16% of 2005 emissions but faces more ambitious abatement targets over coming decades. A new Climate Change Act came into force in 2022 that stipulates that Finland must meet its international abatement obligations – currently, a 50% reduction in EU effort-sharing sector emissions from the 2005 level by 2030, which corresponds to a 39% reduction from the 2020 level (28 Mt CO2-eq.), to which will soon be added Finland’s share (17 Mt CO2-eq.) of the EU forestry and other land-use sink to be reached by 2030 - and its carbon neutral target (i.e., net zero emissions) by 2035. While Finland is almost on track to meet the 2030 gross emissions effort-sharing target - the Climate Change Panel (CCP) judges that only modest further measures (1 Mt CO2-eq.) are needed to meet this target – substantial increases in Finland’s forestry and other land-use sink from the current level (minus 2 Mt CO2-eq.) will be needed to meet its targets. There is scope to reduce abatement costs in effort-sharing sectors by reducing the biofuels mandate to the minimum level required by the European Union and compensating by aligning the carbon price used to calculate carbon tax rates on heating fuels with that used for transport, subjecting heat combustion using peat to the same tax regime as other fossil fuels and, if necessary, increasing the carbon price used to calculate carbon tax rates. Russia’s war against Ukraine and the ensuing energy crisis have made the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables and nuclear power that is necessary to meet GHG emissions abatement objectives an imperative for energy security.

Box 1.3. Key reforms and policy announcements since the 2020 Survey

Labour market

The government has implemented and announced numerous reforms that contribute towards achieving its goal of increasing employment by 80 000 by the end of the decade and, in the process, reducing unemployment and the structural budget deficit. The most important such reforms are:

Increasing the age of eligibility to extended unemployment benefits for unemployed older workers (known as the ‘unemployment tunnel’ to early retirement) from 61 to 62 for persons born in 1962 or later.

Closing entry to extended unemployment benefits by 2025, which will entail abolition of the scheme by 2027 when the last entrants reach 65, the maximum age for receiving the benefit.

Introduction of the Nordic labour services model in May 2022. It provides job seekers with intensive public employment service contact from the beginning of their unemployment spell and gives them more support for job search than under the former system.

Transferring employment and economic development services to municipalities in 2024 to improve the quality of these services and accelerate employment of job seekers. The new funding model will encourage municipalities to develop and offer efficient services.

Parental leave has been reformed, with effect from September 2022, to encourage fathers to take a greater share of parental leave, thereby reducing the career development penalty for mothers and hence the gender wage gap.

The extension of compulsory education to 18 years of age was implemented in 2021.

Innovation

The government has announced its intention to increase R&D spending to 4% of GDP by 2030, of which one third would be public R&D spending.

It has also announced a scheme to accelerate immigration of high-skilled workers in certain professions.

COVID-19

In September 2021, the Government adopted a revised hybrid strategy that aims to lift restrictions imposed due to the pandemic, while ensuring that the healthcare system does not become overburdened and that the epidemic does not become uncontrolled. Although restrictions on hospitality and leisure were maintained during the surge of the Omicron variant, all remaining restrictions on businesses were lifted in March.

National defence and Russia’s war against Ukraine

As a result of Russia’s war against Ukraine, Finland applied to join NATO in May 2022.

In 2021, the government ordered new F35A fighter jets for EUR 10 billion. These purchases will increase the budget deficit from 2025 to 2030, when the planes are delivered.

Measures taken since the war began to strengthen defence and assist Ukrainian refugees increase annual government expenditure by 0.1-0.3% of GDP; in all, measures taken in response to the war contribute 0.8% of GDP to the structural deficit this year and next.

Macroprudential policy

To curb rising household indebtedness, the Board of the Finnish Financial Supervisory Authority (FIN-FSA) returned loan-to-value restrictions for non-first home buyers to the pre-pandemic level (85%) in October 2021 (the limit for first home buyers remains at 95%). In June 2022, the government announced its intention to limit the maximum maturity of housing and housing company loans to 30 years, reduce the maximum amount housing companies can borrow for new construction to 60% of the unencumbered price of the flats to be sold and to require amortisation of such loans to begin during the first five years, all with effect from July 2023. Moreover, the Board of the FIN-FSA increased the macroprudential buffer requirements by 0.5 percentage point for the two largest other systematically important (O-SII) credit institutions in June 2021.

Climate change

A new Climate Change Act came into force in July 2022. It stipulates that Finland must meet its international abatement obligations and its carbon neutral target (net zero emissions) for 2035. In addition to the net zero target, the Act includes abatement targets for 2030, 2040 and 2050, a land-use-sector strategy and targets to increase carbon sinks.

Figure 1.9. Population ageing will slow growth in GDP per capita from the 2030s

Figure 1.10. Greenhouse gas emissions are projected to decline substantially

Gross greenhouse gas emissions with existing (WEM) and additional (WAM) measures

Note: The ‘with existing measures’ (WEM) scenario includes climate and energy measures implemented by 31 December 2019. Measures approved by the government after 1 January 2020 are included in the ‘with additional measures’ (WAM) scenario. For more details on the two scenarios, see (Honkatukia et al., 2021[2]).

Source: (Honkatukia et al., 2021[2]).

Against this background, the key messages of this Economic Survey are that:

To close the gap in GDP per capita with the other Nordic countries, productivity growth must increase, especially by boosting innovation, and the employment rate rise, notably for older workers. Addressing the structural shortage of skilled workers through tertiary education and migration reforms is critical for strengthening productivity growth.

Fiscal consolidation is required to stabilise the government debt-to-GDP ratio in the long run. Regular comprehensive expenditure reviews would help to identify savings. The healthcare and long-term-care reform will contribute to putting public finances on a sustainable path if counties’ incentives to improve efficiency are strong enough.

Further measures are needed to improve the efficiency with which Finland’s greenhouse gas emissions abatement objectives are achieved and to increase the forestry and other land-use sink.

The Finnish economy recovered quickly from the COVID-19 shock, but now faces deteriorating global conditions

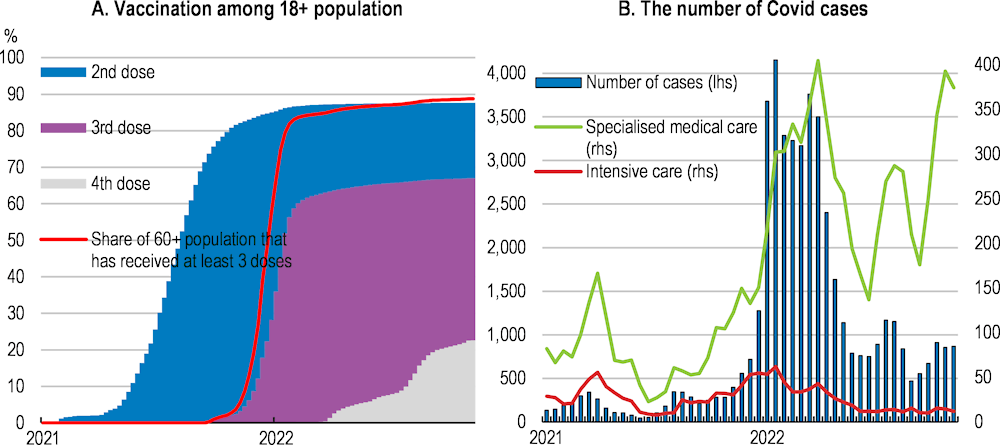

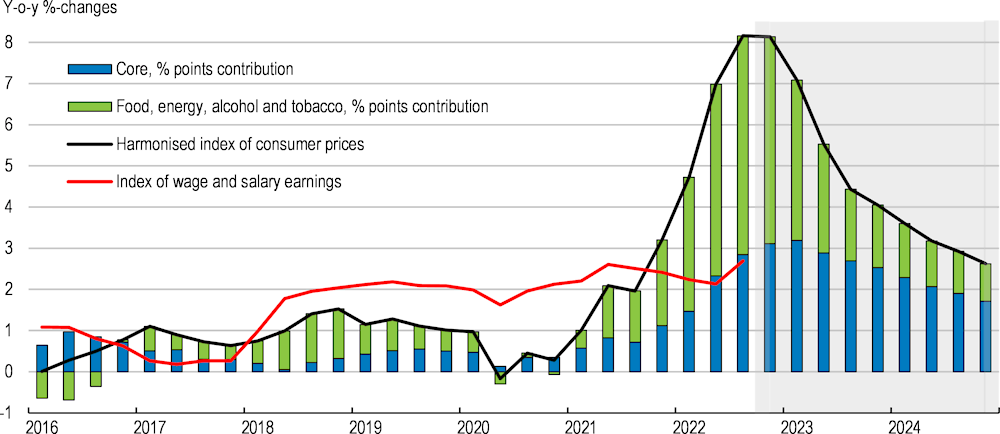

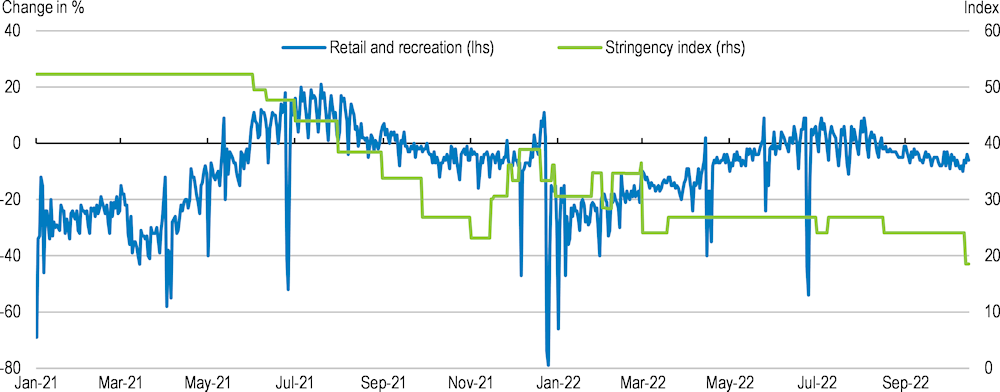

Finland enjoyed a quick recovery in 2020-21 from the COVID-19 shock. Output and the output gap had returned to the pre-COVID level by the second quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, respectively (Figure 1.11). With a rapidly increasing share of the population vaccinated (Figure 1.12, Panel A), mobility strongly rebounded during the second quarter of 2021 (Figure 1.13), regaining pre-pandemic levels. A substantial easing in the stringency of containment measures also began at this time (Box 1.4). These developments paved the way for private consumption expenditure to recover, especially in service sectors that had been most adversely affected by the pandemic, notably hospitality and leisure. With similar developments in Finland’s export markets, exports also rebounded. However, with the rest of the world also emerging from the pandemic, energy prices began to rise markedly in late 2021, aggravating the increases in inflation through 2021 caused by strong demand but still disrupted supply, notably of services and of goods that depend on global supply chains (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.11. The economy recovered quickly from the COVID-19 shock but since has been weighed down by deteriorating global conditions

Figure 1.12. Vaccinations and less virulent COVID-19 variants have limited serious case numbers

Figure 1.13. Mobility was not much affected by the Omicron variant in early 2022

Note: The Oxford Government Response Stringency Index captures the strictness of ‘lockdown style’ policies that primarily restrict people’s

behaviour. It is a composite measure based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans, rescaled

to a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest response). For more information, see: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirusgovernment-response-tracker#data. Mobility change is a comparison relative to a baseline day before the pandemic outbreak. Baseline days represent a normal value for that day of the week, given as median value over the five‑week period from January 3rd to February 6th, 2020.

Source: Google LLC, Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/; Hale, T., S. Webster, A. Petherick, T. Phillips and B. Kira (2020), Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government.

Figure 1.14. Inflation has soared

Box 1.4. Finland’s COVID-19 strategy

Finland’s strategy in response to the Covid-19 pandemic can be divided into four phases:

Early strategy: in the first stage of the pandemic, policy measures were based on a precautionary principle owing to the enormous uncertainties surrounding the virus. The objective was to reduce pressure on the healthcare system and gain time to be able to properly assess future scenarios. To this end, Finland undertook unprecedented control measures to limit social contact.

Pre-vaccination intermediate strategy: after the immediate onset of the pandemic, the strategic objective shifted slightly. Minimizing the number of severe cases and deaths remained the overarching objective, but at the same time society was allowed to function more normally than in the initial phase. This strategy hinged on the effective use of epidemiological data, which allowed for flexible control measures.

Vaccination scale-up intermediate strategy: with vaccines developed, Finland proceeded to vaccinating its population as quickly as possible. The vaccination order was based on age and underlying health condition. Restrictions on social contact remained until vaccination coverage was so high that control measures could be gradually phased out.

Strategy since March 2022: with vaccinations progressing steadily, the final restrictions were lifted in the summer of 2022. The aim now is to keep society as open as possible and to support the post-pandemic economic recovery. New restrictions are to be avoided, and if re-imposed, they should be as limited and local as possible. At the same time, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health is monitoring the pandemic closely and the distribution of a fourth vaccination dose has been expanded to mitigate a potential resurgence in the winter season. The government has also submitted legislative proposals that would make it possible to swiftly re-impose restrictions if need be. Improving the resilience of the healthcare system is key to avoid new widespread restrictions in the future.

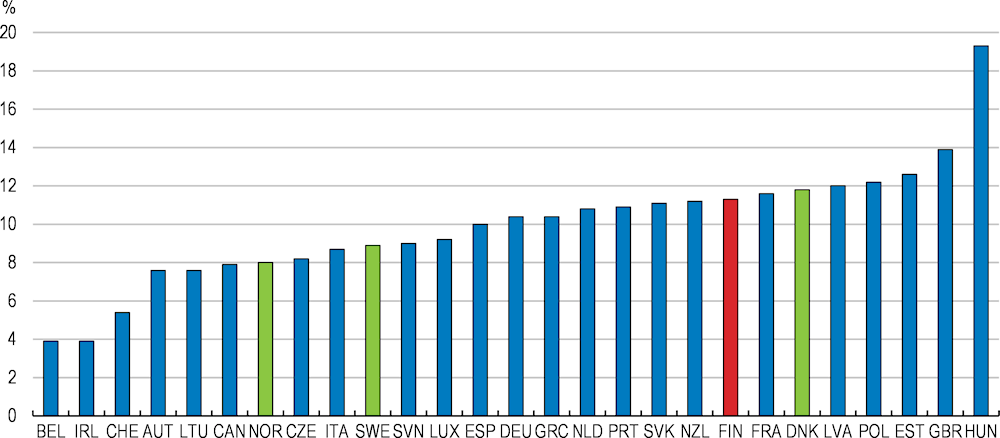

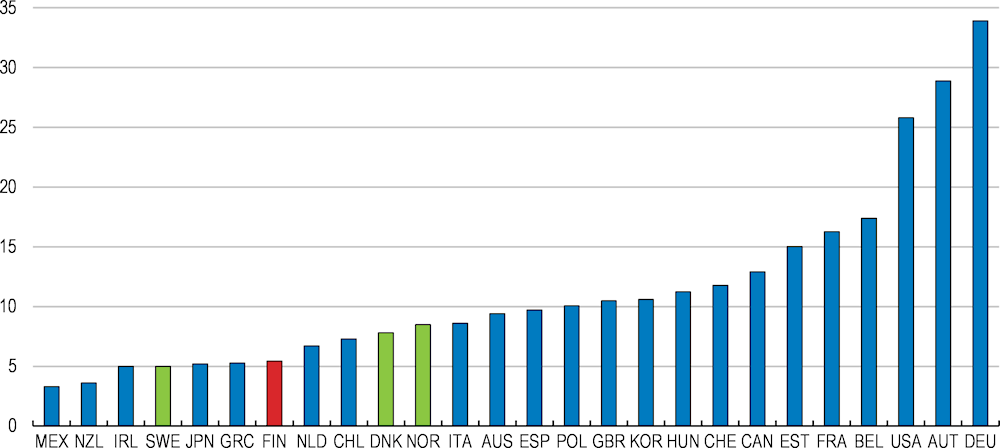

Figure 1.15. Finland had relatively few ICU beds before the pandemic

ICU beds per 100 000 population

Note: 2014 data for Canada and Denmark, 2016 data for Ireland, 2017 data for Chile, Germany, Mexico and Spain, 2018 data for Austria, France, Hungary, Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and the United States, 2019 data for Australia, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Japan, Korea, New Zealand and Poland and 2020 data for Italy, Sweden and the UK (England).

Source: OECD (2020); Berger et al. (2021).

Despite a low COVID-related death toll compared with other OECD countries and high vaccination coverage (87% of the adult population had received at least two doses by November 2022), the pandemic highlighted vulnerabilities in the Finnish hospital system. In the early stages of the pandemic, non-urgent social welfare and healthcare services had to be reduced owing to staff shortages. As the pandemic dragged on, the lack of psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses and home care-personnel hampered the availability of mental care and home-care services. The relatively slow start to Finland’s vaccine rollout can also in part be explained by lack of vaccination personnel in primary health care. The pandemic also put strain on intensive care-unit (ICU) beds, the supply of which was relatively low by OECD comparison (Figure 1.15). To increase ICU capacity, hospitals had to convert operation theatres and recovery areas. Finland’s fragmented healthcare system, where services are in large part financed and organised by municipalities, might also have made managing the pandemic more complicated. The healthcare- and social-care reform should help to address this problem by streamlining the healthcare system. Healthcare, social care and rescue services will be transferred from municipalities to 21 larger wellbeing services counties from the beginning of 2023. The counties will be allowed to collect patient fees, but the funding will mainly be needs-based and come from central government.

There was an upsurge in serious COVID-19 cases in early 2022 but it had only minor economic effects and receded swiftly in April (Figure 1.12, Panel B). COVID-19 is not expected to be a significant drag on the economy this year. Although restrictions on hospitality and leisure were maintained during the surge of the Omicron variant, all remaining restrictions on businesses were lifted in March. However, there is a risk that restrictions may be imposed again if the number of COVID-19 cases surges and consequently threatens to overburden the healthcare system.

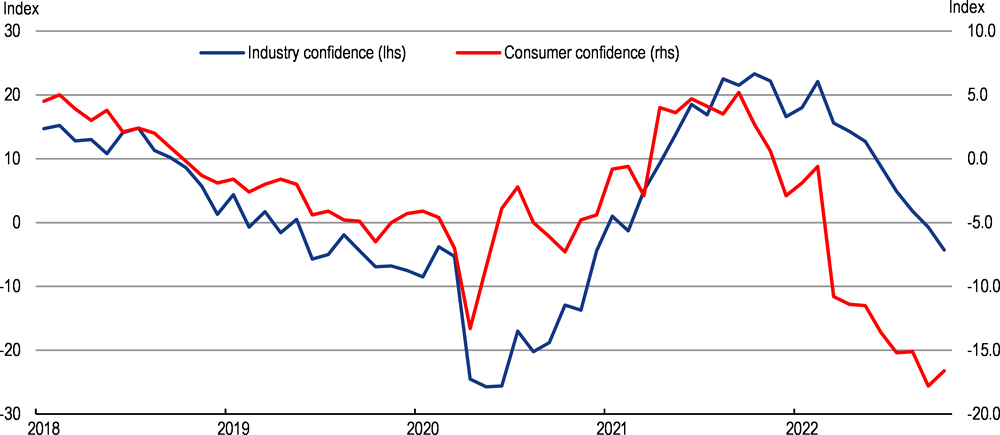

Russia’s war against Ukraine caused further large increases in energy and food prices, which rose by 32% and 13%, respectively, in the year to the third quarter of 2022 and together accounted for around one half of HICP inflation of 8.2% in this period (Figure 1.14), the highest rate since the first quarter of 1991, when this series began. Core HICP inflation increased to 4.2% in the year to the third quarter of 2022 as higher energy and food prices fed into other HICP components. Despite falling real wages (Figure 1.14), private consumption increased sharply during the first half of 2022, underpinning strong economic growth, as households drew down savings accumulated during the pandemic. Wage growth is projected to rise to an annual rate of 4% in 2023-24, which would still entail a significant decline in real wage rates since 2021, as is to be expected in a country that has experienced a fall in its terms of trade. Russia’s war against Ukraine has also eroded consumer confidence, which has fallen to the lowest level since the series began in 1995, and business confidence, portending further weakness in consumption and investment expenditure (Figure 1.16). Exports fell sharply in the first half of 2022, reflecting normalisation following a major ship delivery in late 2021, a decline in telecommunications, data processing and information services exports, a downturn in Finland’s main export markets and a fall in exports to Russia.

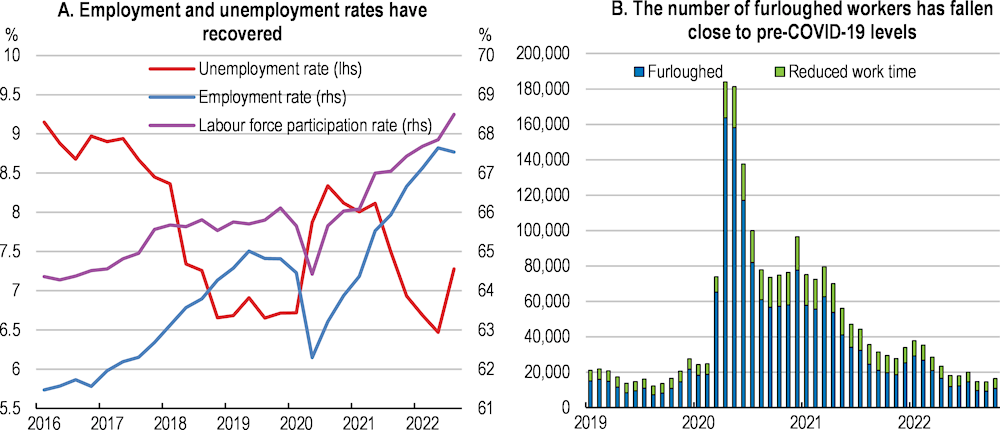

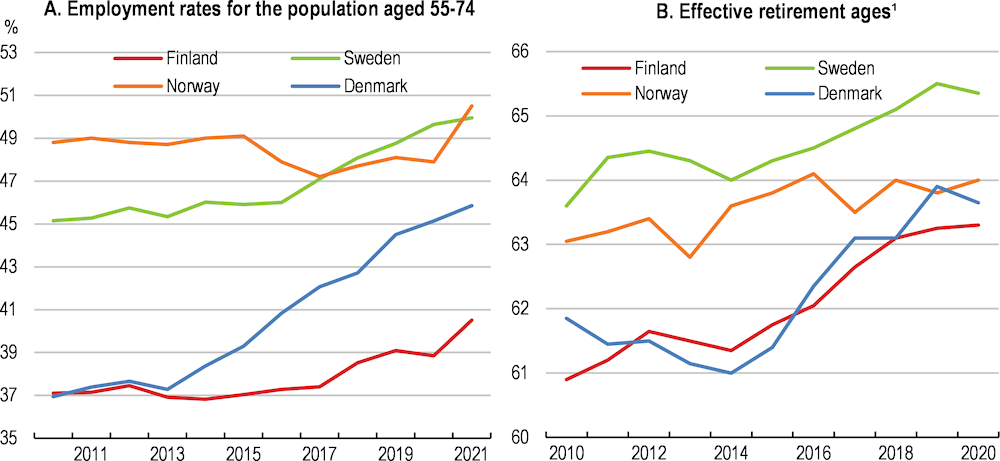

Finland enjoyed a strong labour market recovery from the COVID-19 shock until the second quarter of 2022. The employment- and unemployment rates regained pre-pandemic levels by mid-2021 and early 2022, respectively (Figure 1.17, Panel A), posting their best performances since 1987 and 2008, respectively. The 2017 pension reform (see below) has also contributed significantly to the increases in the employment- and participation rates by encouraging older workers to delay retirement. The participation- and employment rates of the population aged 55-64 years increased by around 5 percentage points from mid-2020 to mid-2022, reaching 76% and 70%, respectively, far above pre-pandemic readings. The long-term unemployment rate began to fall in late 2021 but, at 1.6% in mid-2022, remains higher than before the pandemic. The large increase following the pandemic partly reflects the greater impact it had on sectors (such as hospitality) that are relatively intensive in workers (low skilled, young) who typically experience greater labour-market difficulties than others. The increase (in terms of registrations) was much greater for foreign-born workers (120%) than for the native born (66%). As is usual during a labour market recovery, the decline in long-term unemployment lags that in unemployment. The temporary layoff (i.e., furlough) scheme, which entails a temporary interruption of work and payment of wages while other aspects of the employment contract remain in force, attenuated the labour market impact of the pandemic and laid the ground for a rapid return to normal by limiting hysteresis effects. By late 2022, the number of furloughed workers (classified as being employed in labour market statistics) had fallen to pre-pandemic levels, far below the levels reached in 2020 (Figure 1.17, Panel B).

Figure 1.16. Consumer and business confidence have fallen

Figure 1.17. The labour market has recovered swiftly

Employment- and unemployment rates for the population aged 15-74, seasonally adjusted

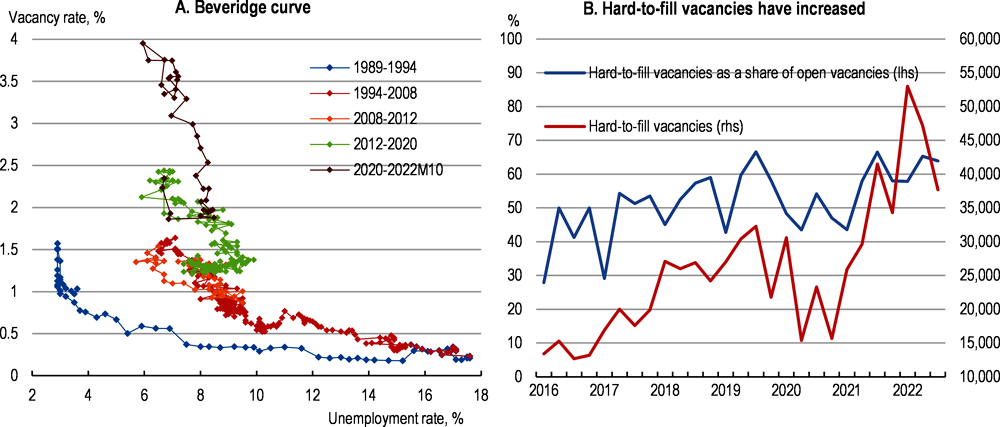

Labour market tightness (vacancies relative to unemployment) has increased markedly recently and there appears to have been an upward shift in the Beveridge curve (Figure 1.18, Panel A). These developments are consistent with firm surveys that report a lack of qualified labour and difficulties to fill open vacancies (Figure 1.18, Panel B). Given the fast recovery and rapid increase in employment, part of the mismatch may be temporary, reflecting frictions in filling jobs. Such mismatch should diminish as growth in labour demand slows. Nevertheless, the upward shift in the Beveridge curve over many years suggests that mismatches are largely structural. Labour shortages are most apparent in public administration, education, human health and social work activities, with shortages having grown most for human health and social work activities. These shortages of qualified labour in non-cyclical professions are likely to persist even as the economy slows. Reducing such mismatch is likely to require training of workers and/or relaxation of skill requirements in jobs as well as stronger incentives for workers, unions and firms to compromise (to improve match acceptance rates). Despite tight labour market conditions, nominal wage growth has remained subdued to date, lagging far behind inflation (see Figure 1.14). Collective agreements concluded to date point to wage increases of around 2.6% in 2022, slightly higher than in 2021. However, municipal workers and nurses recently negotiated a premium over private-sector wage increases (‘the general line’), which could weaken wage coordination in the Finnish system, which is already less formal than in Nordic peers, resulting in higher future wage increases.

The economy is set to stall in 2023 but GDP growth is projected to recover to 1.1% in 2024, with the negative output gap widening to 2.7% of potential GDP by 2024 (Table 1.1). Consumption will weaken in response to falling real wages but subsequently recover as wages rise. Export growth will decline markedly with export markets, which are being hit by the large reduction in gas supplies from Russia, but pick up as these energy sources are replaced and export markets recover. Despite support from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) (Box 1.5), business investment is projected to remain weak through 2023 owing to the economic downturn and more uncertain economic outlook caused by Russia’s war against Ukraine but to strengthen in 2024 as the global outlook improves. The unemployment rate should peak at around 8% and only fall slightly by the end of 2024. Inflation will fall to 3.1% in 2024, when the energy shock will have passed.

Figure 1.18. Job matching has deteriorated and vacancies have become more difficult to fill

Note: Due to a methodology change in the Labour Force Survey (LFS), data on the active population only go back to 2009. For 1989-2008, data from the old LFS have been used to calculate the vacancy rate. Hard-to-fill vacancies are open job vacancies during the reference period that the employer finds hard to fill.

Source: Statistics Finland; OECD, Short-Term Labour Market Statistics (database).

Box 1.5. The Recovery and Resilience Facility is financing environmental, human capital and digital investments

To support the post-pandemic economic recovery in Europe, the European Union launched the Next Generation EU recovery package. The largest part of the package is the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which consists of loans and grants amounting to EUR 723.8 billion. RRF funding is allocated based on member countries’ population, GDP and unemployment rate, as well as on how hard the economy was hit by the pandemic. Finland’s share of RRF funding was originally estimated to EUR 2.1 billion but has since been lowered to EUR 1.8 billion as the Finnish economy has fared better than forecast. Finland has included most of its RRF revenue and expenditure in the budgets for 2021-23. When preparing its Recovery and Resilience Plan, Finland concentrated on a few major packages rather than on distributing resources to many minor projects with smaller impact. The Recovery and Resilience Plan is centred on four key elements:

Green transition: EUR 695 million has been earmarked for investments that will help Finland reach its target of carbon neutrality in 2035. The investments focus on producing and distributing clean energy, such as solar power, offshore wind power, biogas and waste heat recovery, but there is also support for industrial circular economy solutions and for green innovation, for example in hydrogen technology. There are also efforts to reduce the climate impact in the construction sector.

Digitalisation: investments in digitalisation include the Digirail project, expanding high-speed internet connection to areas not served by market actors and support for cutting-edge technologies in AI, 6G networks, quantum computing and microelectronics. The Digirail project seeks to make rail transport safer and more flexible by leveraging digital technology. Making travel and goods transport by rail more attractive will also support climate objectives. Improving digital infrastructure and boosting the development of new technologies will benefit citizens and businesses alike, as it generates new job opportunities and facilitates remote work.

Employment and skills: Investments aim to increase the number of student places at higher education institutions and to enhance digital learning, enabling location-independent study. Public employment services will be digitalised, work- and education-based immigration encouraged and services directed at youth and those with impaired capacity for work. Funding has also been targeted at the tourism and cultural sectors, which were hit hard by the pandemic. More specifically, financial support will be available for measures enhancing export opportunities and thus resilience to future crises.

Healthcare and social services: Several challenges related to the availability and cost effectiveness of the fragmented social welfare and healthcare services are addressed. The objective is to enhance access to health and social services across the country and remove the backlog in the provision of services related to the COVID-19 pandemic. RRP will contribute to the implementation of the seven-day care guarantee from the current three-month deadline. A wide range of digital innovations in the social and healthcare sector are promoted to increase resource efficiency, support preventive services, enable the sharing of expertise between regions and service providers and strengthen the role of customers.

Source: Ministry of Finance.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage changes unless specified, volume (2009/10 prices)

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (EUR billion) |

|||||||

|

GDP at market prices |

233.5 |

1.2 |

-2.2 |

3.0 |

2.2 |

-0.3 |

1.1 |

|

Private consumption |

123.9 |

0.7 |

-4.0 |

3.7 |

2.3 |

-0.6 |

1.4 |

|

Government consumption |

53.5 |

2.0 |

0.3 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

-0.3 |

0.1 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

56.2 |

-1.5 |

-0.9 |

1.5 |

3.0 |

-0.7 |

0.2 |

|

Final domestic demand |

233.6 |

0.5 |

-2.3 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

-0.6 |

0.8 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

0.5 |

-0.9 |

0.2 |

-0.1 |

3.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

236.4 |

-0.3 |

-1.9 |

3.0 |

6.3 |

-0.6 |

0.7 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

89.8 |

6.7 |

-6.8 |

5.4 |

-0.5 |

1.9 |

3.1 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

92.7 |

2.4 |

-6.0 |

6.0 |

9.0 |

1.2 |

2.3 |

|

Net exports1 |

-1.6 |

1.6 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

-3.7 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|||||||

|

Potential GDP |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

|

|

Output gap2 |

-1.2 |

-4.6 |

-3.0 |

-1.9 |

-3.0 |

-2.7 |

|

|

Employment |

1.1 |

-1.5 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

-0.6 |

0.2 |

|

|

Employment rate (% of population aged 15-74) |

64.8 |

63.5 |

65.6 |

67.4 |

67.2 |

67.6 |

|

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force, 15-74) |

6.7 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

7.0 |

7.9 |

7.8 |

|

|

GDP deflator |

1.5 |

1.5 |

2.5 |

6.0 |

4.7 |

3.1 |

|

|

Terms of trade |

-0.5 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

2.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

|

Harmonised index of consumer prices |

1.1 |

0.4 |

2.1 |

7.0 |

5.3 |

3.1 |

|

|

Harmonised index of core inflation³ |

0.7 |

0.5 |

1.2 |

3.6 |

4.3 |

3.1 |

|

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

0.4 |

4.7 |

2.0 |

-1.4 |

-1.2 |

-1.3 |

|

|

General government financial balance (% of GDP) |

-0.9 |

-5.5 |

-2.7 |

-2.5 |

-3.9 |

-3.6 |

|

|

General government cyclically-adjusted balance2 |

-0.2 |

-2.6 |

-0.8 |

-1.4 |

-2.1 |

-1.9 |

|

|

General government underlying primary balance2 |

-0.1 |

-2.5 |

-0.9 |

-1.6 |

-2.3 |

-2.2 |

|

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP)⁴ |

78.4 |

90.8 |

85.0 |

84.9 |

87.2 |

88.8 |

|

|

General government net debt (% of GDP) |

-62.7 |

-64.1 |

-72.4 |

-72.6 |

-70.3 |

-68.6 |

|

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition (% of GDP) |

64.9 |

74.8 |

72.4 |

72.2 |

74.5 |

76.2 |

|

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

-0.3 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

-2.6 |

-2.2 |

-1.9 |

|

|

Short-term interest rate |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

0.5 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

|

|

Long-term interest rate |

0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

1.9 |

5.1 |

5.0 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP; 2. As a percentage of potential GDP; 3. Harmonised index of consumer prices excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco; 4. National Accounts basis excluding unfunded liabilities of government employee pension funds.

Source: OECD (2022), Economic Outlook (database).

Key downside risks are that Russia’s war against Ukraine is more protracted than expected and that Russia cuts off gas supplies to more EU countries by end-2022, which would prevent the rebuilding of European gas stocks during summer 2023 and result in shortages during the winter of 2023-24 (tail-risk events that could entail major changes to the outlook are summarised in Table 1.2). These developments would increase energy prices and inflation and reduce industrial production in Finland’s main trading partners, notably Germany, with adverse ramifications for economic activity and employment in Finland. A more protracted war would increase uncertainty about the economic outlook, reducing business investment. Foreign investors could demand a premium on returns on Finnish investments to compensate for risks arising from Finland’s geographical proximity to Russia. There is also the risk that tightening global financial conditions could depress the housing market and consumption and investment. Banks’ high dependence on wholesale funding and high exposure to real estate lending could aggravate the problem. On the upside, private investments catalysed by the RRF could be higher than projected.

Table 1.2. Events that could entail major changes to the outlook

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Russia escalates its war against Ukraine, leading to a more protracted conflict. |

A deeper, more drawn-out conflict would heighten the pressure on those of Finland’s trade partners that have not been able to adapt their energy infrastructure. |

|

Geopolitical tensions rise, resulting in sanctions and countersanctions that drastically reduce trade between China and the EU and North America. |

The global economy would fall into a recession and would face severe supply chain disruptions, depressing economic activity and increasing inflation in Finland and other advanced economies. |

|

A new, more virulent coronavirus variant arrives that is resistant to existing vaccines. |

Economic activity would fall as people avoid activities that put them at risk and/or are restricted by containment measures to avoid intensive care facilities becoming overwhelmed. |

Macroeconomic policies are becoming less expansionary

Monetary policy is becoming less accommodative

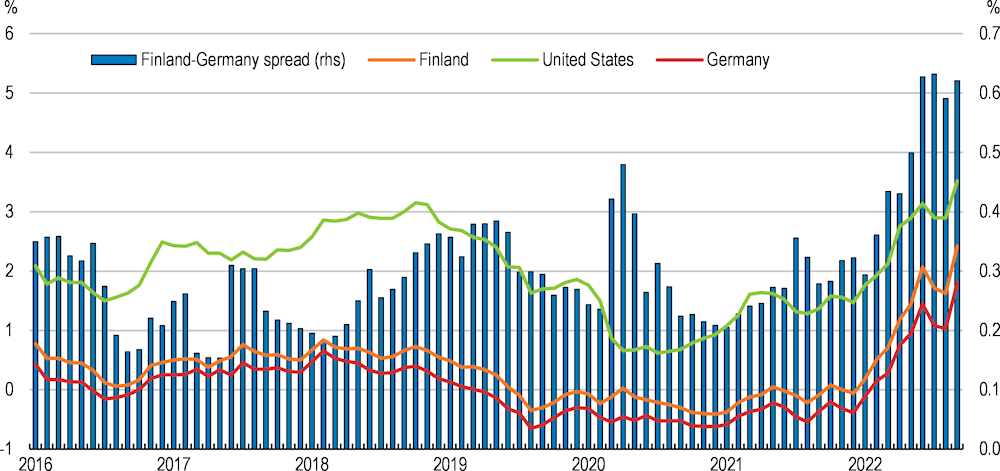

Monetary conditions have been highly accommodative in recent years. European Central Bank (ECB) policy rates on the main refinancing operations, the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility were cut to 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.50% in September 2019 and remained at these levels until July 2022, when the ECB increased them by 50 basis points. The ECB increased these rates by a further 75 basis points in both September and November 2022 and indicated that it expects to raise rates further over the coming several meetings of the Governing Council to dampen demand and guard against the risk of a persistent upward shift in inflation expectations. Quantitative easing helped to depress Finnish long-term government bond yields, which were negative most of the time in 2020-21. Long-term government bond rates have increased markedly since late 2021, mainly reflecting the increase in global rates but also Russia’s war against Ukraine and the flight to safe havens during uncertain times, which have increased the risk premium (spread) over German rates (Figure 1.19).

Figure 1.19. Long-term government bond rates and the spread over German rates have increased

Macroprudential and financial policies should be tightened to contain financial stability risks

Russia’s war against Ukraine has had little direct effect on Finnish financial institutions. They had low exposures to Russia at the onset of the war - claims on Russian entities only amounted to 0.1%, 0.3% and 0.4%, respectively, of banks’, insurance companies’ and investment funds’ assets and have continued to decrease – and indirect exposures were moderate - about one quarter of loans to non-financial corporations (NFCs) were to vulnerable sectors that were energy intensive or had strong connections to Russia via trade links (i.e., more than a 5% share of exports or imports). The stock and bond prices of a number of large firms with significant exposure to Russia – fell sharply at the onset of the war, increasing funding costs, but have since been relatively stable. Fortum (BBB, 51% government owned), which had a EUR 5.5 billion exposure to Russia before the war (reduced to EUR 3.3 billion by 30 September 2022) and held a 76% stake in Uniper, the German company developing the North Stream II gas pipeline, experienced large falls in its share price until Uniper’s divestment to the German government in September 2022. Increased collateral requirements on energy derivatives contracts have dramatically increased liquidity requirements for energy companies, including Fortum. To ease this liquidity stress, the Finnish and Swedish governments have committed to provide significant liquidity support to energy companies.

In addition to increasing the risk of loans to companies in vulnerable sectors, Russia’s war against Ukraine has adversely affected the operating environment for Finnish financial institutions by increasing commodity prices and disrupting energy supplies in Finland and its main trading partners, reducing economic growth, and increasing Finland country risk (see above) and the risk of cyber-attacks. To minimise potential disruption from cyber-attacks, a national backup system for the payments infrastructure has been created.

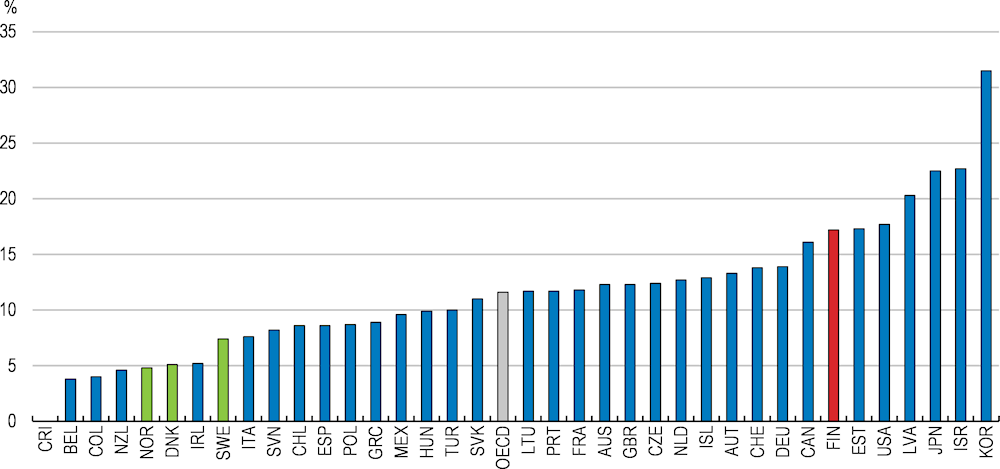

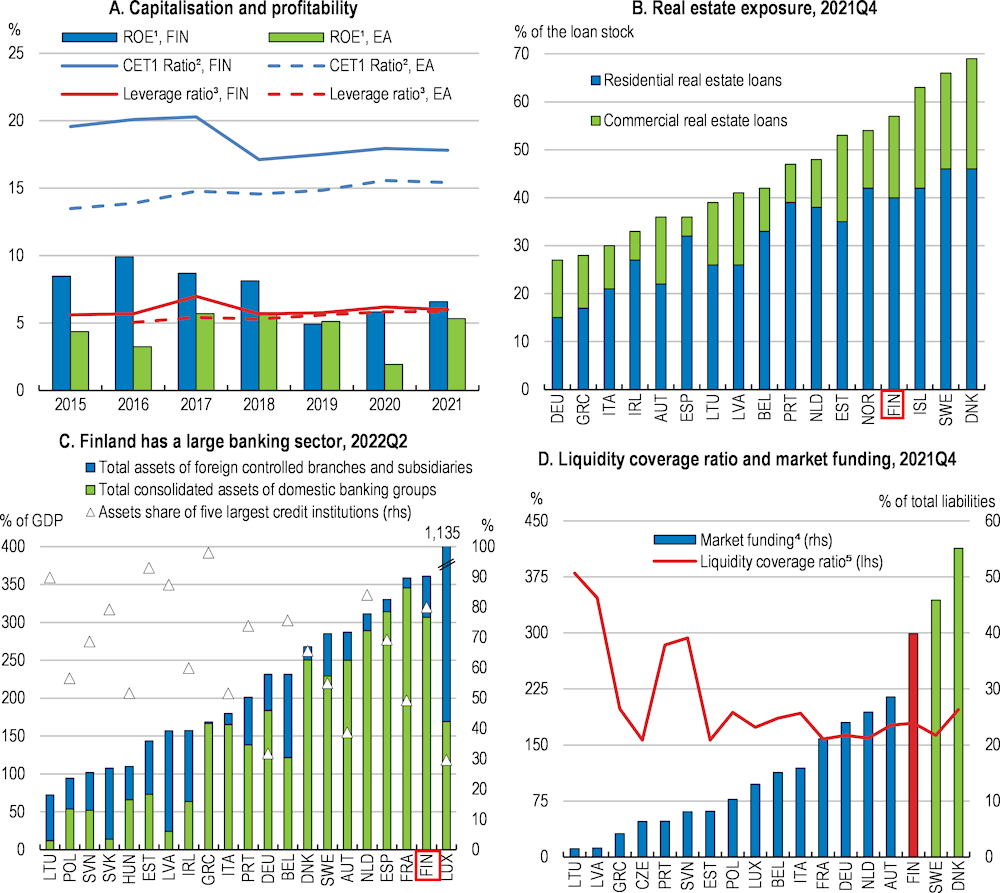

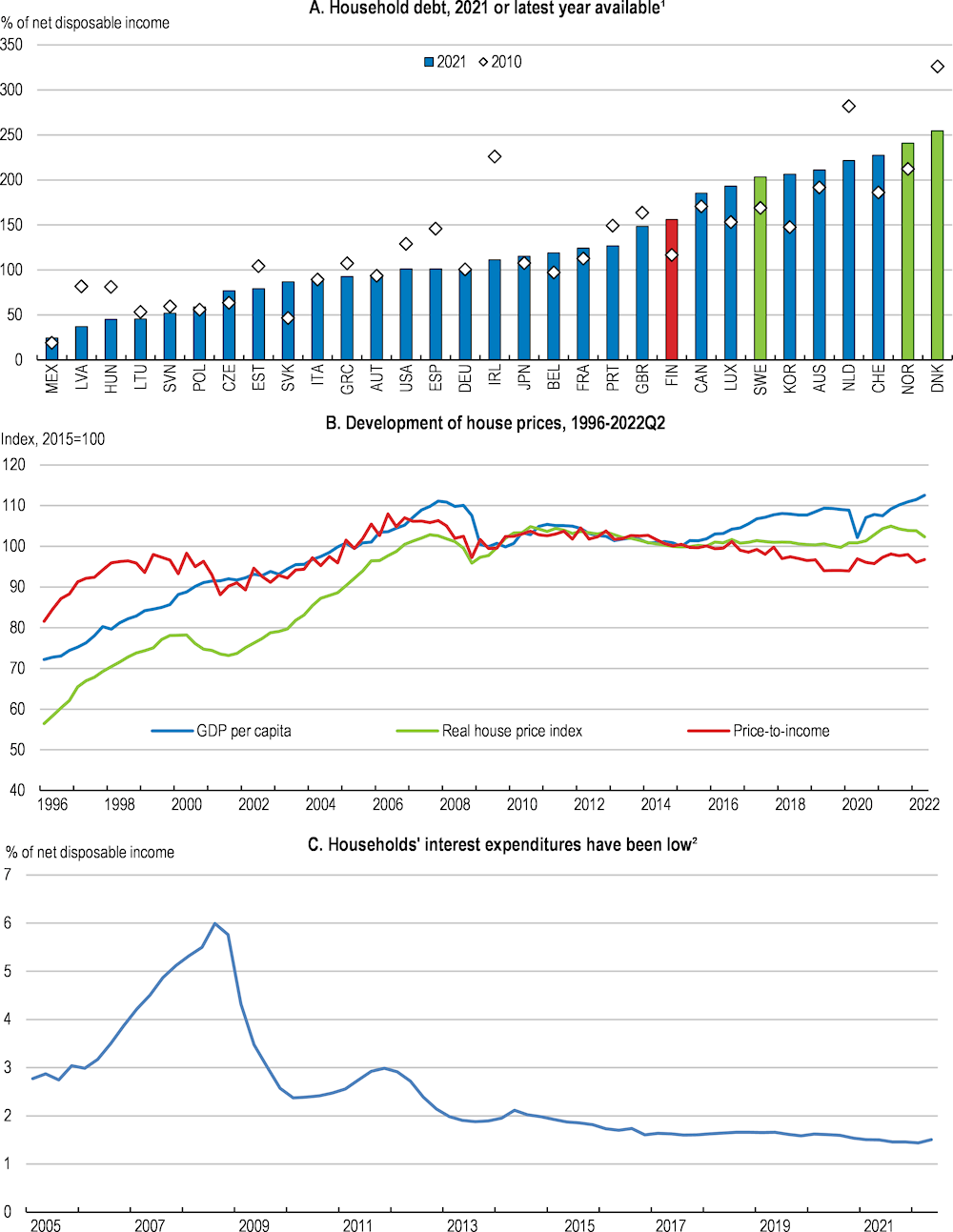

Finnish financial institutions are well capitalised (Figure 1.20, Panel A), increasing their resilience to cope with structural vulnerabilities, notably high household indebtedness (three quarters of which is housing loans including housing company loans) (Figure 1.21, Panel A) and large housing loans with long maturities; housing company loans on behalf of households grew by 75% in the five years to 2022 Q1 and account for 80% of total housing company loans. Households are vulnerable to rising interest rates as over 90% of housing loan rates are linked to Euribor, typically for one year, although 28% of new loans by value in recent years have been hedged against interest-rate risk. On the other hand, housing affordability has not deteriorated over the past decade (Figure 1.21, Panel B) and households’ interest expenditure has fallen as a share of net disposable income (Figure 1.21, Panel C). Housing loans account for 40% of loans granted to households and non-monetary corporations resident in Finland. Finnish financial institutions also have large residential- and commercial real estate loan exposures in the other three Nordics. In all, residential- and commercial real-estate loans comprise 40% and 28%, respectively, of the loan stock, which is high by international comparison (Figure 1.20, Panel B). Other vulnerabilities are the banking system’s substantial size (Figure 1.20, Panel C), concentration and interconnectedness and the high reliance on wholesale market funding (Figure 1.20, Panel D), making it vulnerable to market disruptions. Progressively introducing limits on wholesale funding as a share of total funding, as in New Zealand, would help to increase bank resilience to funding shocks.

Figure 1.20. The banking system is well capitalised but with structural vulnerabilities

1. Return on equity. 2. Common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital relative to risk-weighted assets. 3. Tier 1 capital relative to assets. 4. Deposits and debt securities relative to total liabilities. 5. Liquidity buffer relative to net liquidity outflows over a 30-calendar day stress period.

Note: First quarter data for Norway in Panel B. In Panel D, market funding data are from 2020 Q4.

Source: European Central Bank and European Banking Authority.

Figure 1.21. Household indebtedness is high but interest expenditures are low and housing affordability has not deteriorated

1. 2020 data for Japan, Mexico and the United States. Households include non-profit institutions serving households.

2. Households excluding non-profit institutions serving households. The interest-to-income ratio has been calculated as total interest expenditure before FISIM allocation over a four-quarter moving average of net disposable income. No adjustment has been made for interest deduction.

Source: OECD (2022), Economic Outlook (database); Statistics Finland.

To curb rising household indebtedness, the Board of the Finnish Financial Supervisory Authority (FIN-FSA) returned loan-to-value (LTV) restrictions for non-first home buyers to the pre-pandemic level (85%) in October 2021 (the limit for first-home buyers remains at 95%). In June 2022, the government put forward its legal proposal to limit the maximum maturity of housing- and housing company loans to 30 years, reduce the maximum amount housing companies can borrow for new construction to 60% of the unencumbered price of the flats to be sold and to require amortisation of such loans to begin during the first five years, all with effect from July 2023. These measures, which reduce the risk of bank losses, should be complemented by debt-service-to-income (DSTI) or loan-to-income (LTI) restrictions, which reduce the risk of households not being able to service their mortgages. Fifteen OECD countries have de jure debt-servicing restrictions and a further three have de jure loan-to-income restrictions (van Hoenselaar et al., 2021[3]). Empirical evidence suggests that DSTI restrictions may be more effective than LTV restrictions in curbing credit growth (Cerutti, Claessens and Laeven, 2017[4]) (Claessens, Ghosh and Mihet, 2013[5]) (Poghosyan, 2020[6]). Hoenselaar et al. (2021[3]) document empirical studies that find that LTV and DSTI restrictions combined are effective in limiting the build-up in household credit. Nevertheless, the government chose not to give the FIN-FSA the power to introduce DSTI restrictions, contrary to the advice of the FIN-FSA, the Bank of Finland and the recommendation in the 2020 Survey (Table 1.3), owing to concerns that it may disproportionately affect first-home buyers. Such concerns could be eased by setting a higher DSTI cap for first-home buyers, as is already done for LTV restrictions in Finland. Even so, first-home buyers would still likely be the most affected. On the other hand, their risk of default and the associated high personal costs would also be diminished. The Board of the FIN-FSA issued a non-binding recommendation on debt-servicing-to-income limits in June 2022 and will assess the need for a sectoral capital risk buffer for mortgages with high debt-to-income or debt-servicing-to-income ratios.

Table 1.3. Past recommendations on macroprudential policy and actions taken

|

Past OECD policy recommendations (key ones in bold) |

Policy actions since the 2020 Economic Survey of Finland (December 2020) |

|---|---|

|

Introduce a maximum debt-to-income ratio for household loans and a maturity limit for housing loans. |

The government introduced a 30-year maturity limit for housing loans that will take effect from July 2023. The Board of the Finnish Financial Supervisory Authority (FIN-FSA) issued a non-binding recommendation on debt-servicing-to-income limits in June 2022 and will assess the need for a sectoral capital risk buffer for mortgages with high debt-to-income or debt-servicing-to-income ratios. In June 2022, the government chose not to introduce a debt-to-income or debt-servicing-to-income restriction out of concern that it could disproportionately affect first-home buyers. |

|

The prudential supervisors should monitor the effects of looser capital adequacy, regulations and criteria for non-performing loans (NPLs) and collateral eligibility and tighten them as the economy recovers. |

The FIN-FSA monitors these effects. The loosening in capital adequacy requirements and regulations and criteria for NPLs and collateral eligibility are still in force. A return to normal pillar 2 guidance and capital buffer requirements is expected by end-2022 at the earliest. |

Preferential tax treatment of owner-occupied housing and of rental housing financed by housing company loans also encourage the accumulation of housing debt. For owner-occupied housing, mortgage interest payments have been tax deductible and neither imputed rents nor capital gains are taxable. These tax advantages are capitalised into property prices, increasing the size of loans needed to buy property. This tax treatment will become less favourable from 2023, when mortgage interest will no longer be tax deductible. The government should consider going further by taxing capital gains on the principal residence unless they are re-invested in another principal residence within a certain time, as in the United States; the re-investment option avoids lock-in effects, which would be harmful to labour mobility and efficient resource allocation, but not eventual payment of the tax. For rental housing financed by housing company loans, the tax advantage over direct financing is that taxation can be deferred until shares in the housing company are sold. Housing companies take out loans for renovation and new construction using their real estate as collateral and then charge shareholders, who have occupancy rights to individual residential units in the company property, a monthly fee for all running costs and the amortisation of each owner’s share of loan repayments. These arrangements encourage investors in rental properties to purchase them through a housing company as the fee, which includes principal repayments, can be deducted from rental income whereas principal repayments on other loans cannot. If the deduction is taken against rental income, it cannot be taken again against capital gains when shares in the housing company are sold. Hence, the tax advantage is the ability to defer taxation until the shares are sold, the value of which will depend on interest rates. This tax advantage should be terminated, as recommended in the 2020 Survey (Table 1.4). Tax on transfers of shares in a housing company (2%) is also lower than on direct property transactions (4%). As property transfer taxes impose substantial welfare costs by distorting housing- and labour market decisions (Eerola et al., 2021[7]), these taxes should be replaced by taxes with lower efficiency costs, such as annual real estate taxes.

Table 1.4. Past recommendations on tax reform and actions taken

|

Past OECD policy recommendations (key ones in bold) |

Policy actions since the 2020 Economic Survey of Finland (December 2020) |

|---|---|

|

Reduce the tax burden on labour. |

No action taken. The tax burden on labour has increased since the government came into office in 2019. |

|

Increase minimum- and maximum rates on recurrent taxes on immovable property, and better align the tax base with market valuations. |

No action taken. |

|

Broaden the consumption tax base and phase out reduced VAT rates. |

No action taken. |

|

Lower the normal interest rate used in the calculation of the unincorporated business taxation equity allowance. |

No action taken. |

|

Remove the preferential tax treatment on capital repayments of housing company loans for investors and align the stamp duty rate on direct property transactions with that on transfers of shares in housing companies. |

No action taken. |

Housing company loans are also associated with mispriced risks resulting from the cross-subsidisation of high-risk shareholders by others. This problem arises because such loans are mutually guaranteed by all shareholders: fee payment defaults by some shareholders must be paid by others should the company be unable to recover the fees in default by other means (such as selling the shares concerned or letting the defaulting shareholder’s apartment), a fact that many shareholders are unaware of or not able to price. One solution could be to make insurance cover compulsory for unrecoverable fees in default – insurance companies would levy higher premiums on high-risk shareholders than others (much as banks charge higher interest rates on loans to high-risk borrowers than on loans to others).

A useful additional element in the Finnish system to be launched in 2024 is the positive credit register. The register gathers information on the credits issued to Finnish individuals as well as their current income. The register will have very wide coverage on the type of exposures: it will include mortgages, student loans, consumption loans, credit cards and bank accounts with a credit limit, vehicle loans, loans for an investment purpose, part payments and leasing contracts. In the second stage, at the end of 2025, loans granted for an individual’s business operations will also be reported to the register. The positive credit register will improve lenders’ ability to test the creditworthiness of loan applicants, provide a source of reliable information on the credit market and create new ways to monitor the financial market for the macroprudential authorities.

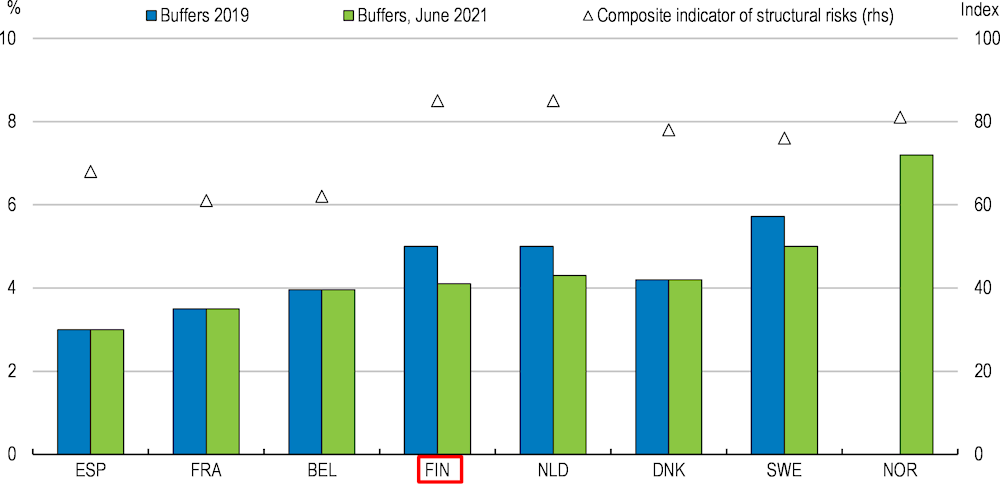

The Board of the FIN-FSA announced in June 2022 that the structural macroprudential buffer requirements for the two largest other systematically important credit institutions (O-SII) will be increased by 0.5 percentage point from 1 January 2023. This increase will strengthen these institutions’ loss-absorption capacity, thereby reducing the probability of financial crises and their negative impacts on the real economy and on the operation of the financial system. So as not to distort competition, buffer requirements should be set with regard to structural vulnerabilities. Kiviniemi (2022[8]) measures these by risk indicators capturing: the size of the banking sector; its concentration; the extent of cross-border activities; the concentration and financing structure of banks’ credit portfolios; and household indebtedness. Finland has similar structural risk levels as the other Nordics and the Netherlands but somewhat lower structural macroprudential buffers (Figure 1.22). The increase in buffer requirements will close the gap between Finland, on the one hand, and Denmark and the Netherlands, on the other, but not with Sweden and Norway. While the need to strengthen the resilience of the banking system remains, the gloomy and uncertain outlook for the economy and the financial system suggests any increases in the systematic risk buffer (SyRB) should be delayed so as not to have pro-cyclical effects.

Figure 1.22. Structural macroprudential buffers are smaller in Finland than in countries with similar structural risk levels

Note: For details on how the buffers and the composite indicator were constructed, see Bank of Finland Bulletin, 1/2022.

Source: (Bank of Finland, 2022[9]).

Legislation should also be changed to allow a positive neutral Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB). As demonstrated by Covid-19 pandemic as well as more recently by Russia’s war against Ukraine, large shocks outside the financial system may have cyclical effects on credit markets. In other words, there can be unexpected negative credit-cycle developments that are not preceded by a credit boom. The possibility of setting a positive rate for the CCyB even in the neutral credit market phase would allow macroprudential policymakers to address such developments.

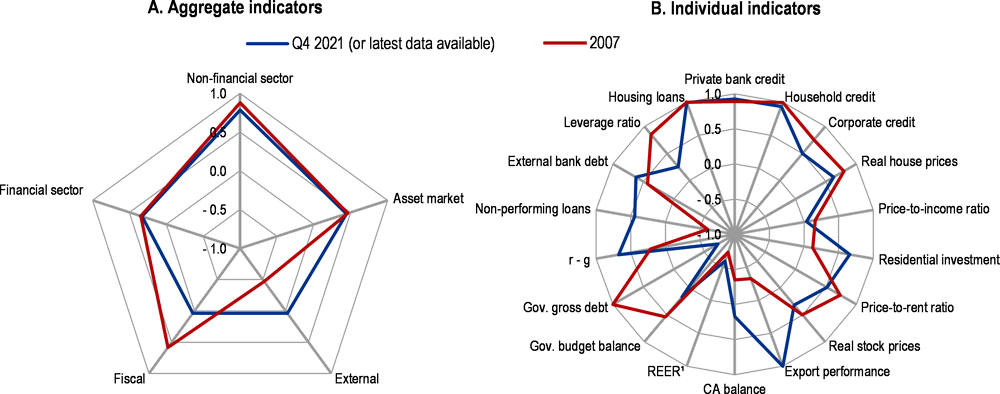

The greatest macro-financial vulnerability is in the non-financial sector (Figure 1.23, Panel A), reflecting high levels of private bank- and household credit, both of which are far above the long-term average and are around 2007 levels (Figure 1.23, Panel B). Asset market vulnerability is also above the long-term average, albeit less so than non-financial sector vulnerability. The main factors contributing to asset market vulnerability are high real house prices, residential investment and house price-to-rent ratios. Financial-sector vulnerability is also above the long-term average, albeit less so than non-financial sector and asset market vulnerabilities, mainly owing to high housing loans, external bank debt and non-performing loans, all of which are equal to or greater than in 2007.

Figure 1.23. High levels of private bank- and household credit are a major macro-financial risk

Index scale of -1 to 1 from lowest to greatest potential vulnerability, where 0 refers to long-term average

Note: Each aggregate macro-financial vulnerability indicator is calculated by aggregating (simple average) normalised individual indicators. Non-financial includes: private bank credit, household credit and corporate credit. Asset market includes real house prices, price-to-income ratio, price-to-rent ratio, residential investment and real stock prices. External position includes the current account (CA) balance as a percentage of GDP, export performance and real effective exchange rate based on relative unit labour costs. Fiscal includes the difference between the interest rate on the government bonds and expected growth rate (r-g), government budget balance and government gross debt, both expressed as a percentage of GDP. Financial includes the share of non-performing loans in total loans, external bank debt as percentage of total banks’ liabilities, banks’ assets as share of GDP, and capital and reserves as a proportion of total liabilities (leverage ratio).

Source: OECD Resilience Database.

Fiscal policy will be expansionary in 2023 but neutral in 2024

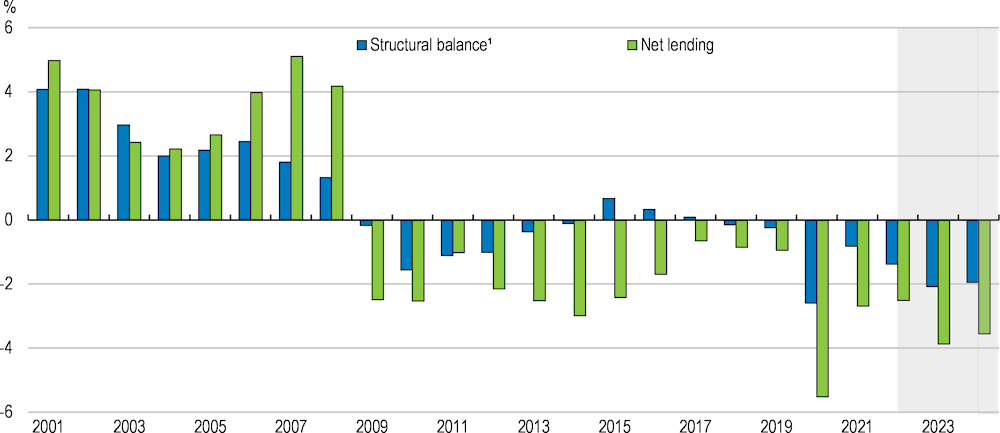

Following a marked fall in 2021 as the extent of COVID-19 support declined, the general government structural budget deficit is estimated to have increased by 0.6 percentage point to 1.4% of GDP in 2022, despite the termination of most remaining COVID-19 support measures, and is projected to rise to around 2% of GDP in 2023 and 2024 (Figure 1.24), with central and lower levels of government running structural deficits but pension funds a structural surplus of around 1% of GDP. Additional expenditures related to Russia’s war against Ukraine contribute 0.8% of GDP to the structural deficit in 2022 and 2023 and somewhat less in 2024. These include increases in defence expenditure and refugee-related expenditures (0.1-0.3% of GDP annually); the government estimates that there will be 60 000 (1.1% of the total population) applications for temporary protection in 2022 from people fleeing Ukraine. The government has also announced budget measures amounting to EUR 1.7 billion (0.6% of GDP) to cushion the impact of higher energy prices, including a temporary reduction in the VAT rate on electricity from 24% to 10% over December 2022-April 2023 (EUR 209 million), targeted assistance to households over this period (EUR 600) and targeted measures focused on transport (EUR 900 million), including a temporary reduction in VAT on passenger transport services, that expire at the end of 2023. These measures, most of which are targeted and warranted, largely account for the expansionary fiscal stance in 2023. All war-related expenditure increases as well as investments that boost energy production and help harness new technologies replacing fossil fuels are excluded from the government’s spending limits. The structural budget deficit over the projection period is around 1.8% of potential GDP higher than before the pandemic. General government gross debt (Maastricht definition) is projected to continue increasing, from 72% of GDP in 2021 to 76% in 2024.

Figure 1.24. The structural budget deficit remains relatively large

General government, % of GDP

1. Cyclically-adjusted net lending, per cent of potential GDP.

Source: OECD (2022), Economic Outlook (database).

Table 1.5. Past recommendations on fiscal policy and actions taken

|

Past OECD policy recommendations (key ones in bold) |

Policy actions since the 2020 Economic Survey of Finland (December 2020) |

|---|---|

|

Stand ready to provide further fiscal stimulus in case the economic recovery is delayed. |

This has occurred, largely through additional expenditures related to the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine. |

|

Once the economic recovery is underway, implement consolidation measures, mainly by reducing expenditure, including on subsidies and tax expenditures, and also by increasing taxes that do not impose large economic distortions, such as VAT (broadening the standard-rate base) and recurrent real estate taxes. |

Measures to reduce the structural budget deficit have largely focused on increasing employment and thereby increasing revenue and reducing transfers expenditure. No action has been taken on reducing subsidies and tax expenditures or on increasing taxes that do not impose large economic distortions. |

|

Strengthen budget buffers. |

No action taken. |

Real public investment is projected to grow strongly in 2022 (8.5%) and 2023 (6.1%) and average around 4.5% of GDP (in current prices), which is much higher than the EU average (Ministry of Finance, 2022[10]). In 2022, public investment will be boosted by efforts to improve Finland’s security and to implement the green transition and to a lesser extent by projects financed by the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, partly offset by local government disposals of hospitals. Weakening local government finances and sharp price increases could, however, hamper civil engineering investments this year and next. In 2023, continued strong growth will be driven by central government measures to develop cybersecurity, national defence and border control but somewhat attenuated by the completion of transport infrastructure investments, the slowing of hospital construction and the ending of infrastructure subsidies. Civil engineering investments and other construction investments both account for close to 30% of public investments. Research and development investments account for just over 25% and machinery and equipment investments for just over 10% of the total. Public investment in housing construction has declined over the past decade, contributing to deteriorating rental housing affordability (OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, 2021[11]).

General government contingent liabilities grew strongly in the past decade to 27.1% of GDP in 2020, the highest level in the European Union. Concentration of loan guarantees in a small number of sectors and enterprises increases risks for government finances. One half of the guarantees are for the shipbuilding industry and their riskiness is likely to have increased owing to the pandemic. The Finnish Audit Office (2018[12])notes that risk levels of contingent liabilities vary greatly and rightly stresses the need to limit the overall risk to which they expose government finances rather than to set numerical stock ceilings by instrument category. To control risks, the Audit Office considers that there must be good justification for increasing contingent liabilities, a comprehensive risk assessment should be made before making any commitments, regular reports on the risk position should be submitted, and that limitations of risk permitted would reduce total risk.

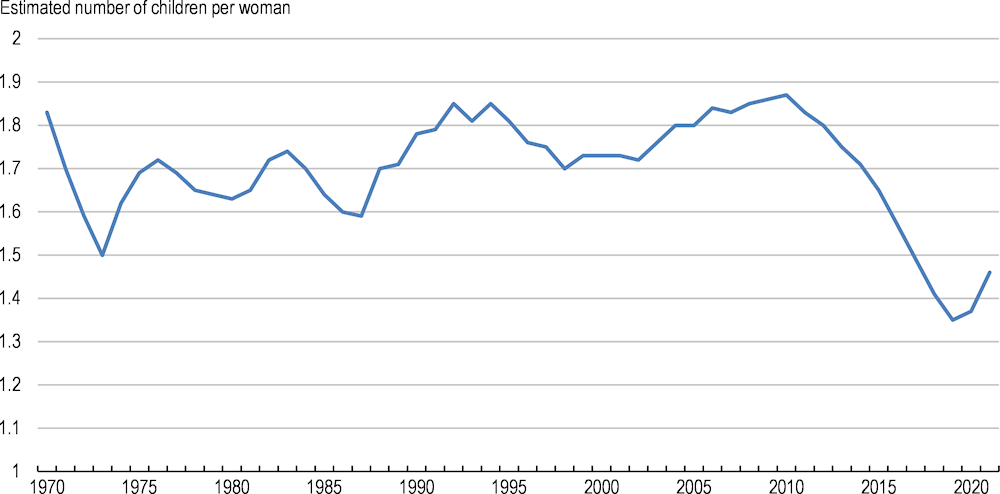

Restoring public finance sustainability

Age-related expenditures are projected to rise by only 4.5% of GDP between 2019 and 2070 (Table 1.6). Pension expenditures are projected to decline as a share of GDP until 2050 despite the age-dependency ratio increasing from 36.0% to 48.6% thanks to reforms that have greatly reduced the effects of rising life expectancy on expenditures (Box 1.6). However, pension expenditures will rise as a share of GDP in the subsequent two decades as a fall in fertility rates during the 2010s (Figure 1.26) filters through the population age structure, reducing the working-age population sooner than the population eligible for old-age pensions (on the assumption that the fertility rate remains at 1.5 over the projection period). Increases in contribution rates (currently 24.4%) to Finland’s (earnings-related) pension system, which is financed from both assets accumulated in pension funds (for one-fifth of private-sector pension expenditure) and pay-as-you-go (PAYG) contributions, would be required from the 2040s to ensure that the pension system remains sustainable. Education expenditures will initially fall as a share of GDP owing to smaller cohorts of youth but are assumed to rise subsequently to prevent a decline in the stock of human capital while healthcare- and long-term-care expenditures rise markedly reflecting both population ageing and, for healthcare expenditure, excess cost growth (i.e., long-term growth in healthcare expenditures relative to GDP that is not related to demographics) (Table 1.7).

Table 1.6. Pension reforms limit growth in age-related expenditures

|

2019 |

2030 |

2040 |

2050 |

2060 |

2070 |

2019 to 2070 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age-related expenditure |

% GDP unless otherwise stated |

||||||

|

Pensions |

13.3 |

13.3 |

12.4 |

12.2 |

13.0 |

13.8 |

0.5 |

|

Healthcare |

6.8 |

7.1 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

0.9 |

|

Long-term care |

2.0 |

2.7 |

3.5 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

5.3 |

3.3 |

|

Education |

5.6 |

5.3 |

4.9 |

5.1 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

-0.1 |

|

Total |

27.8 |

28.4 |

28.2 |

28.7 |

30.3 |

32.3 |

4.5 |

|

Participation rate² |

66.5 |

66.3 |

69.1 |

71.3 |

70.5 |

69.5 |

3.0 |

|

Old-age dependency ratio³ |

36.0 |

42.9 |

45.1 |

48.6 |

54.1 |

59.2 |

21.7 |

1. Baseline scenario. Data for 2019 and projections thereafter. Inflation is 2% from 2028 onwards.

2. For the population aged 15-74.

3. Population aged 65 and over relative to the population aged 15-64, in per cent.

Source: (Bank of Finland, 2021[13]).

Table 1.7. Key assumptions underlying debt-ratio projections

|

Annual growth rates, % |

2020-29 |

2030-39 |

2040-49 |

2050-59 |

2060-70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Potential output |

1.2 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Labour productivity |

1.1 |

1.3 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Hours worked |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

|

Human capital |

1.3 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Fixed capital |

1.3 |

1.7 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

Implicit nominal interest rate on public debt |

1.3 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

Non-interest property receipts (% of non-interest-bearing financial assets). |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

|

Real growth rate of non-interest property receipts |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

|

Government interest-bearing financial assets (% of GDP) |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

1. Baseline scenario. Data until 2021 and projections thereafter. Inflation is 2% from 2028 onwards.

2. Non-interest-bearing financial assets are shares and investments in mutual funds. Receipts from these investments were 2.3% of the value of such investments in 2021, compared with an average of 2.9% since 2000.

3. It is assumed that dividends grow at a real rate of 2.3% per year. This gives an approximate real return on equity investments of 4.6% and, with the risk-free real rate assumed to be 1%, an equity risk premium of 3.6% in the long run.

Source: (Bank of Finland, 2021[14]); OECD projections for implicit interest rates, return on equity investments (dividend yield and growth in dividends) and government financial assets.

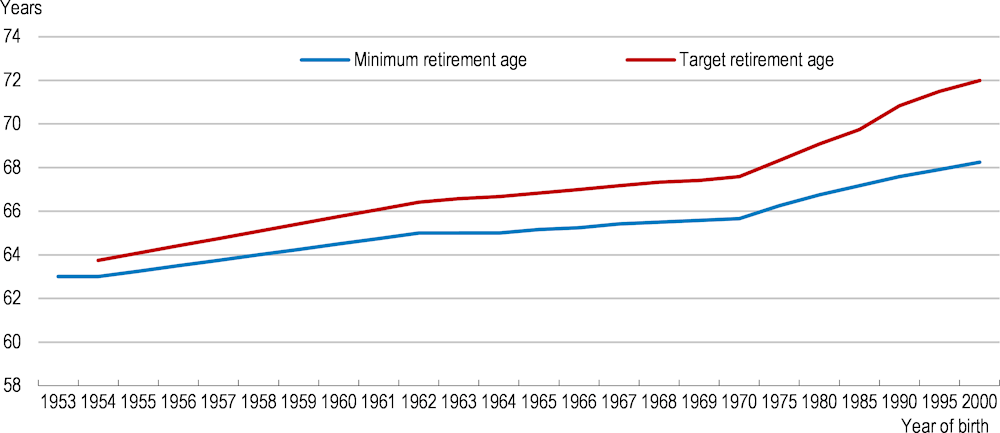

Box 1.6. Pension reforms have reduced the effects of growing life expectancy on expenditures

The 2005 reform introduced the life-expectancy coefficient, which reduces pensions for each cohort born after 1947 such that growing life expectancy does not increase the present value of pensions at age 62 from the level in 2009. This reform also changed the income base for calculating pensions from the last 10 years of each employment contract to incomes over the entire work history. The 2017 reform raises the minimum retirement age gradually from 63 to 65 by 2025 and will link it to life expectancy from 2030 in such a way that the share of adult life spent in retirement remains constant. To help people make informed decisions about the timing of their retirement, a target retirement age is calculated for each cohort that corresponds to the age at which the pension increment from delaying retirement offsets the reduction from the life expectancy coefficient (Figure 1.25). However, people born after 1985 will not be able to avoid lower pensions because their target retirement age exceeds 70, the age limit for pension contributions. To give these people the opportunity of contributing longer to avoid these pension reductions, this age limit should be indexed to the target retirement age beyond 70; this would not affect the pension system’s solvability as the extra contributions would offset the additional pension liabilities.

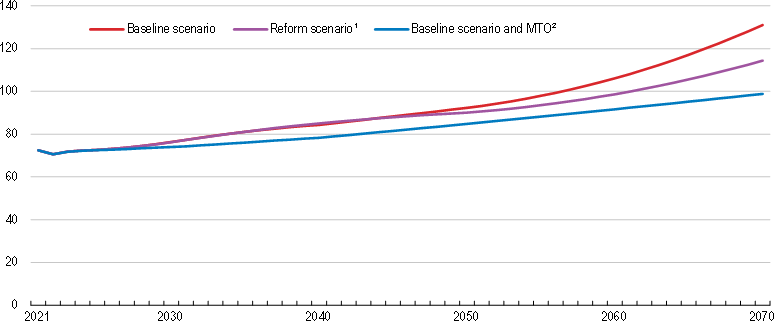

Figure 1.25. Target retirement ages are rising faster than minimum retirement ages

On unchanged policies (baseline scenario) and assuming that age-related expenditures grow in line with the projections in Table 1.6, the OECD projects that gross general government debt will increase from 72% of GDP in 2021 to 131% by 2070 and continue rising thereafter (Figure 1.27). This debt trajectory assumes that education expenditure volume per student increases from its present level to the level seen in the early 1990s. As a result, human capital stagnates from the late 2040s instead of declining (Table 1.7). With population ageing causing hours worked to decrease from the 2030s onwards, potential output growth is entirely driven by fixed capital, which is assumed to grow until the fixed capital to human capital ratio is the same as in the early 1990s. Potential growth stabilises at 0.5% from the 2040s onwards. In the reform scenario, where the innovation system becomes more effective and work-based immigration increases, gross general government debt rises to 114 % of GDP by 2070. If Finland reduces its structural budget deficit to the medium-term objective (MTO) of -0.5% of GDP by 2030, which is a legal obligation although not necessarily by 2030, and continuously takes consolidation measures to keep the structural deficit at this level, the debt ratio would increase from 72% of GDP currently to 99% by 2070. A more ambitious structural deficit objective would be required for long-term fiscal sustainability. Possible consolidation measures are discussed below.

Figure 1.26. The fertility rate¹ fell sharply over the past decade

1. The total fertility rate in a specific year is defined as the total number of children that would be born to each woman if she were to live to the end of her child-bearing years and give birth to children in alignment with the prevailing age-specific fertility rates. It is calculated by totalling the age-specific fertility rates in a given year.

Source: Statistics Finland.

The government is committed to reducing the structural budget deficit mainly by increasing employment, which will reduce transfers expenditure and increase government revenue. It has set a target of increasing employment by 80 000 by the end of the decade. The Ministry of Finance estimates that the employment measures taken to date or planned could increase employment by around 40 000 (see below) and reduce the structural deficit by EUR 450 million (EUR 1 billion before taking into account associated increases in expenditure), far short of the EUR 1-2 billion (0.4-0.8% of GDP) assumed by the government. Taking into account these measures, the effects of the war and the measures taken in response and good employment outcomes, the Ministry of Finance estimates that the sustainability gap (an EU measure (S2 indicator) of the amount by which the structural balance would need to increase for the debt-to-GDP ratio to be stable in the long run on unchanged policies) is approximately 2.5% of GDP (Ministry of Finance, 2022[10]), 0.5 percentage point less than at the time of the last Survey. The government has proposed further reforms to increase employment (see below) but for the time being there are no credible estimates of their effects.

Figure 1.27. Government debt would increase substantially under unchanged policies

Gross general government debt, % GDP