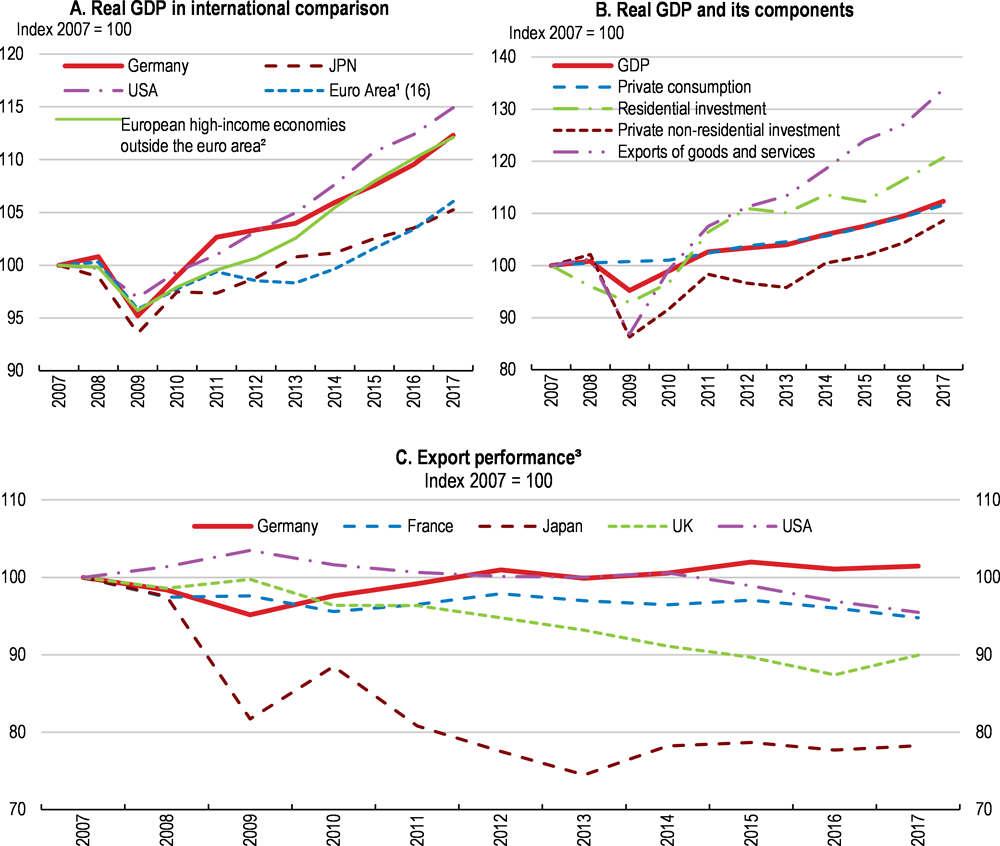

Germany has been enjoying strong economic performance in recent years, building on strengthened domestic demand, good social outcomes and export performance. Exports have benefited from a large, productive and innovative manufacturing sector which has reinforced its position in sectors of long-standing comparative advantage, notably cars, chemical products and machine tools. Record-low unemployment, employment growth and real wage gains have underpinned private household demand. Business investment is picking up.

OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2018

Key policy insights

Economic and social wellbeing are strong

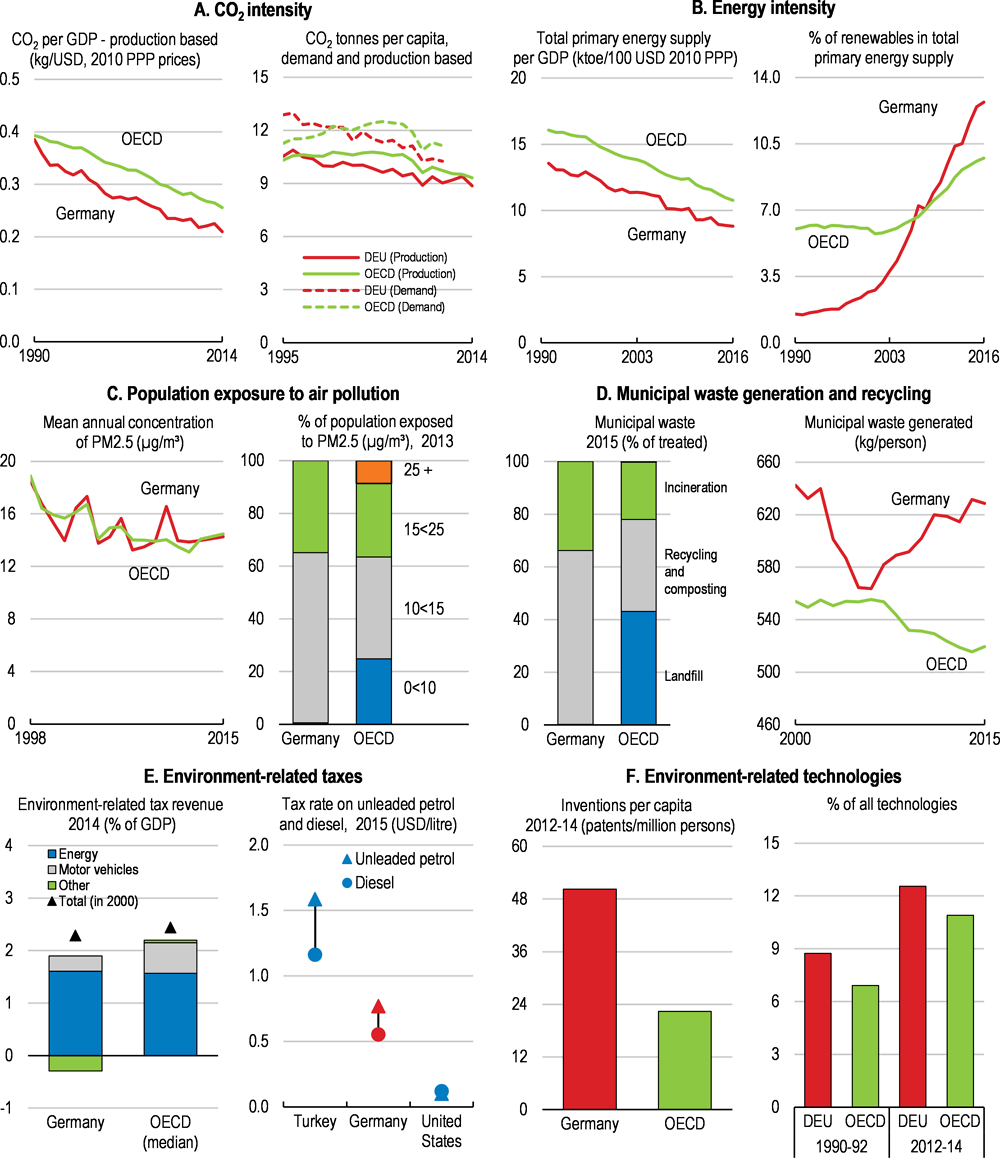

Figure 1. How's life in Germany?

Better Life Index, 2017

Note: Each well-being dimension is measured by one to four indicators from the OECD Better Life Index set. Normalised indicators are averaged with equal weights. Indicators are normalised to range between 10 (best) and 0 (worst) according to the following formula: (indicator value - minimum value) / (maximum value - minimum value) x 10.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Better Life Index, www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org.

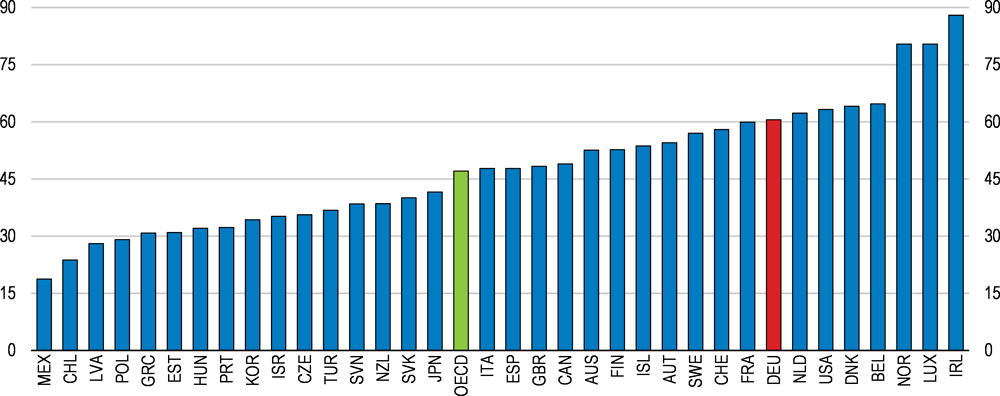

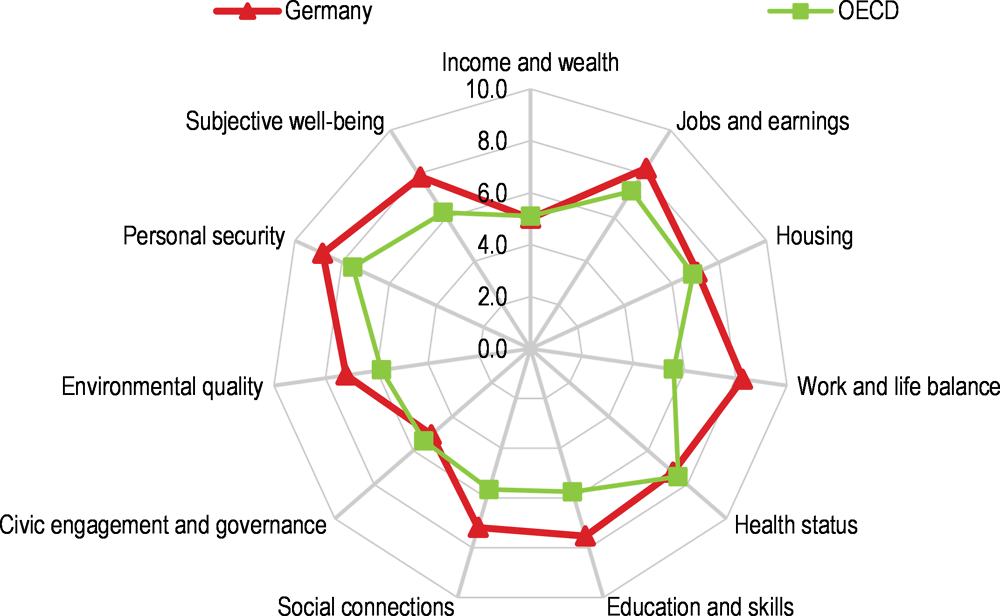

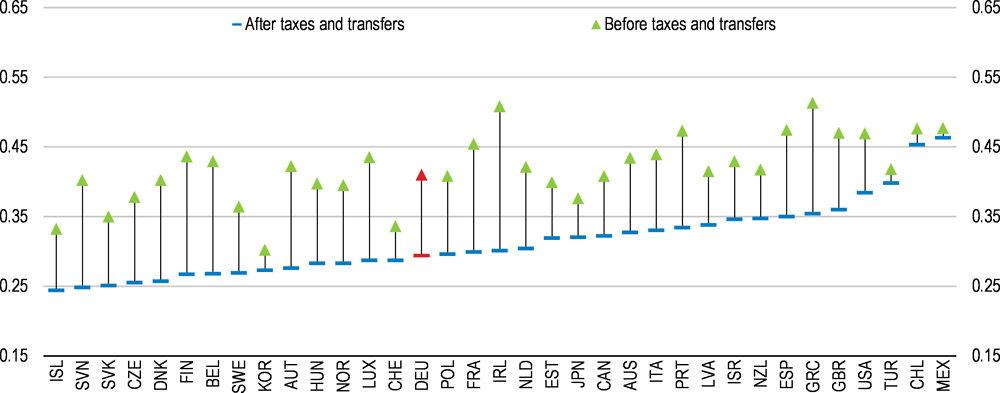

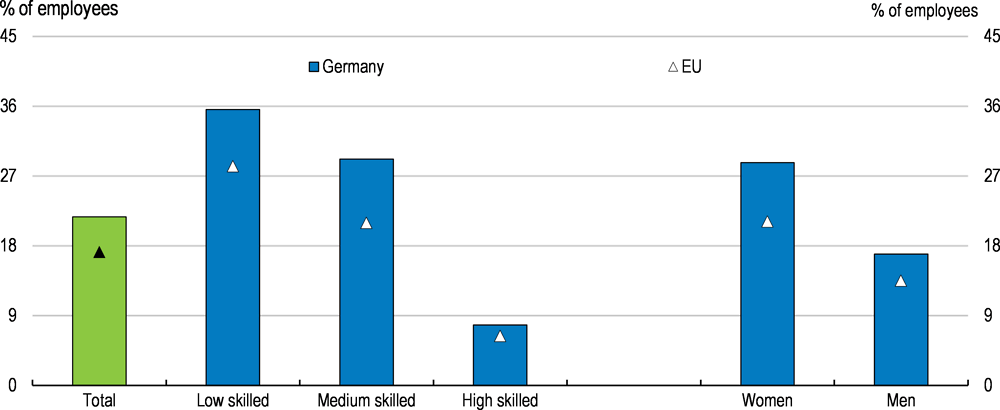

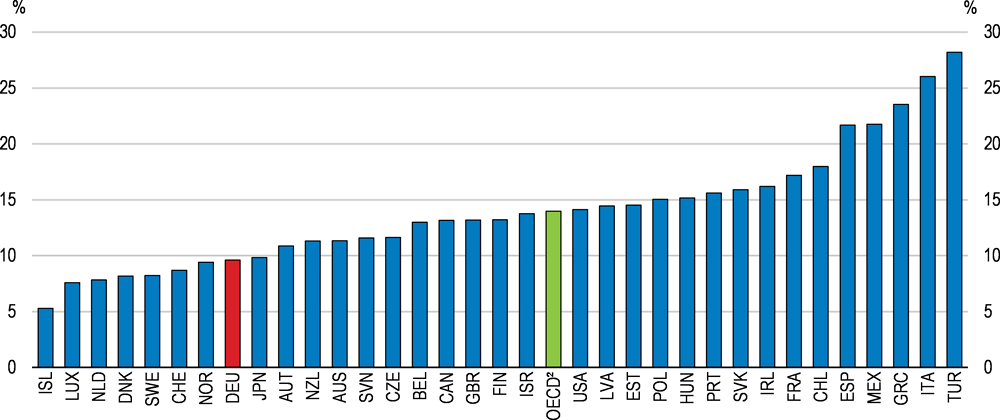

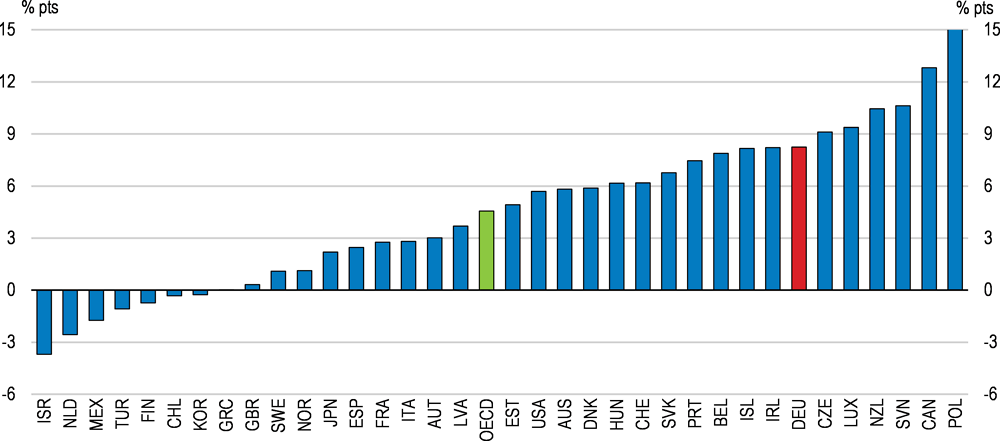

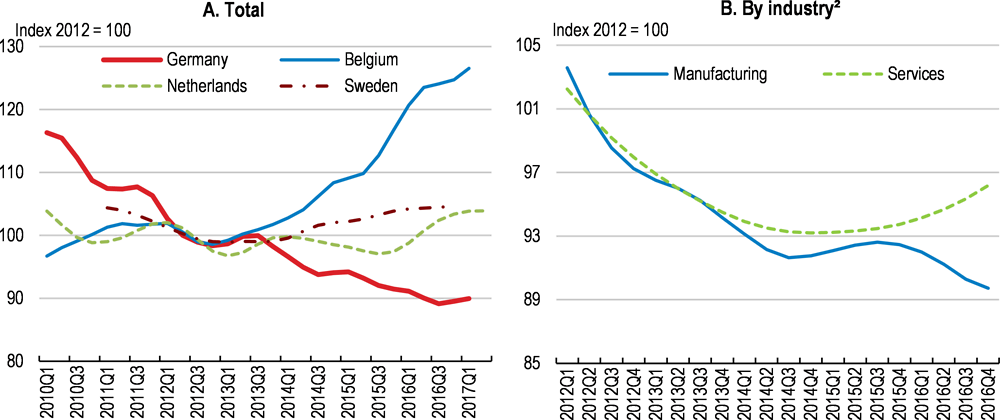

On aggregate, the population enjoys a high standard of living, as reflected in broad measures of well-being (Figure 1). Personal security, work-life balance, jobs and earnings as well as subjective wellbeing are particularly good. Almost the entire population is educated to upper secondary level and PISA scores are in the upper range of OECD countries, though still at some distance from best-performing countries. While health outcomes are relatively good overall, self-assessed health among adults with low education is poor (OECD, 2017[1]). Median household wealth is modest, in part reflecting a highly unequal distribution of wealth across households, low housing wealth, and a relatively short period of prosperity in Eastern Germany, where incomes are still lower. While wealth and market incomes are concentrated, disposable household income among the working age population is more equally distributed than in other large OECD economies (Figure 2). The share of population in relative income poverty is lower than in most OECD countries (Figure 3). Poverty is strongly concentrated in some regions. A high incidence of low pay employment, especially among low and middle-skill workers and among women, is a major driving force (Figure 4). Housing costs have risen in major urban centres and are now high, damping housing well-being indicators.

Figure 2. Income inequality among the working population is lower than in most OECD countries after taxes

Gini coefficient, scale from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality), 18-65 year-olds, 2015 or latest year

Note: After taxes and before transfers for Hungary, Mexico and Turkey.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Social and Welfare Statistics (database).

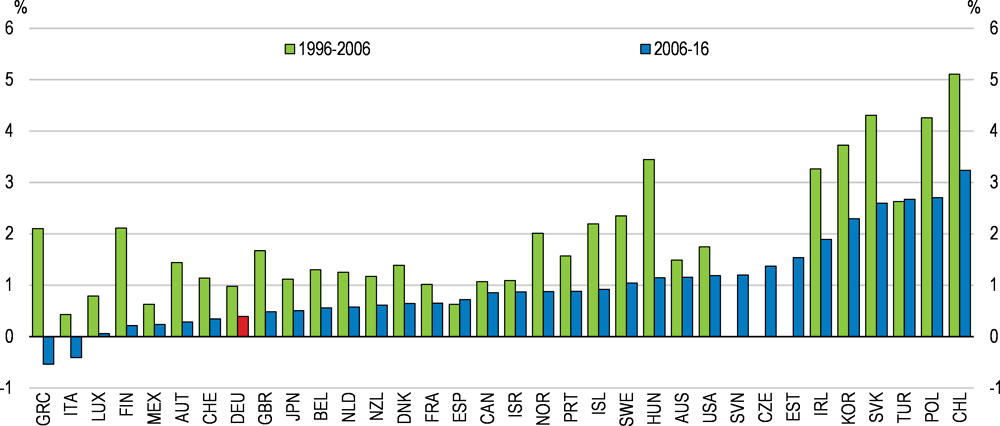

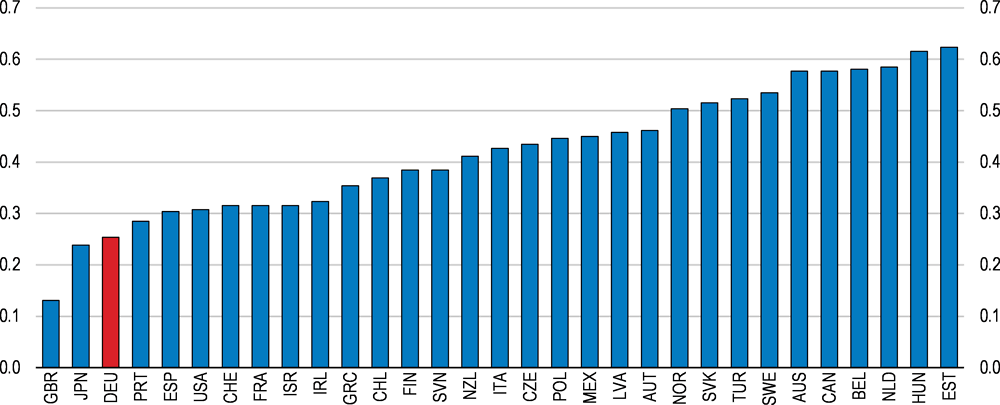

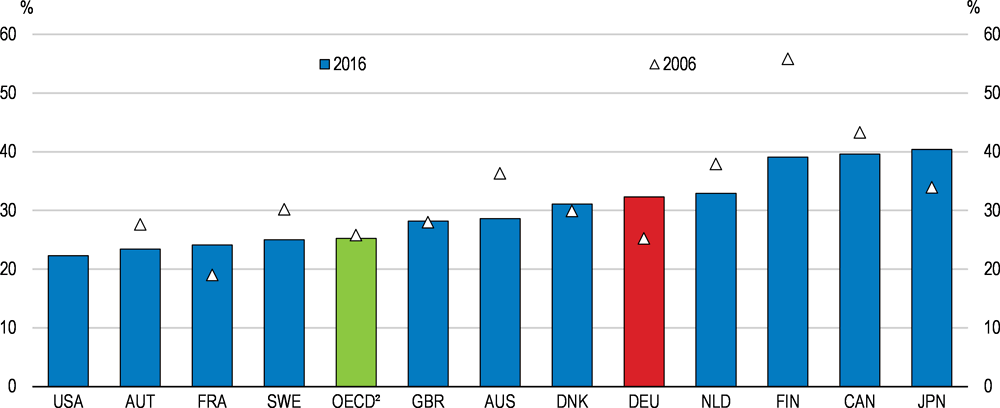

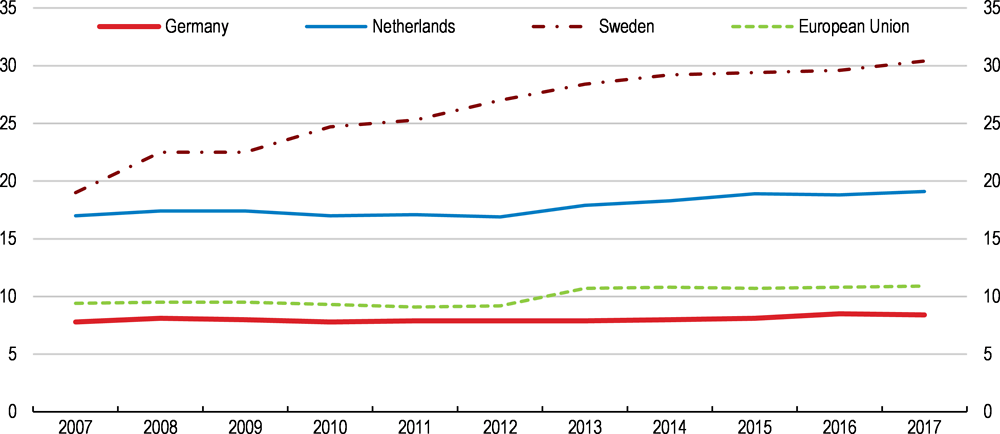

In this context, the main concern for policy makers is to make sure strong social and economic outcomes are sustained in the future, in the face of several challenges. As elsewhere, trend productivity growth has diminished (Figure 5), partly reflecting weakening technology diffusion. Past labour market reforms (the Hartz reforms), while having boosted employment, may have contributed by raising the share of workers with low qualifications. Productivity convergence in Eastern Germany has also slowed. However trend productivity growth has also been low in international comparison in recent years. Productivity growth is key to rising incomes, especially in the context of demographic ageing, which will reduce labour supply.

Figure 3. Relative poverty is lower than in most OECD countries

Share of population with disposable income below the poverty line¹, total population, 2015 or latest year

1. The poverty line is 60% of median household income. Household income is adjusted to take into account household size.

2. Unweighted average.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Social and Welfare Statistics (database).

Figure 4. The incidence of low-pay employment is high

Low-wage earners by education and gender, 2014

Note: Low-wage earners are defined as those employees earning less than two thirds of the median gross hourly earnings. Low skilled, medium skilled and high skilled are defined respectively as educational attainments of below upper secondary (ISCED 0-2), upper and post-secondary (ISCED 3-4) and tertiary (ISCED 5-8). All employees excluding apprentices working in enterprises with 10 or more than 10 employees and which operate in all sectors of the economy except: agriculture, forestry and fishing (NACE Rev. 2, section A); and public administration, defence and compulsory social security (NACE Rev. 2, sections O).

Source: Eurostat (2018), Employment and working conditions (database).

Figure 5. Trend productivity growth has diminished and is low in Germany

Average annual rate of trend labour productivity growth

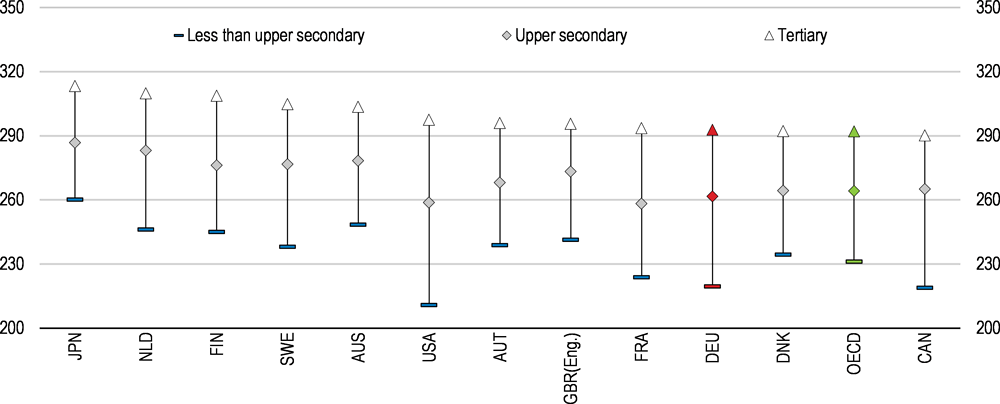

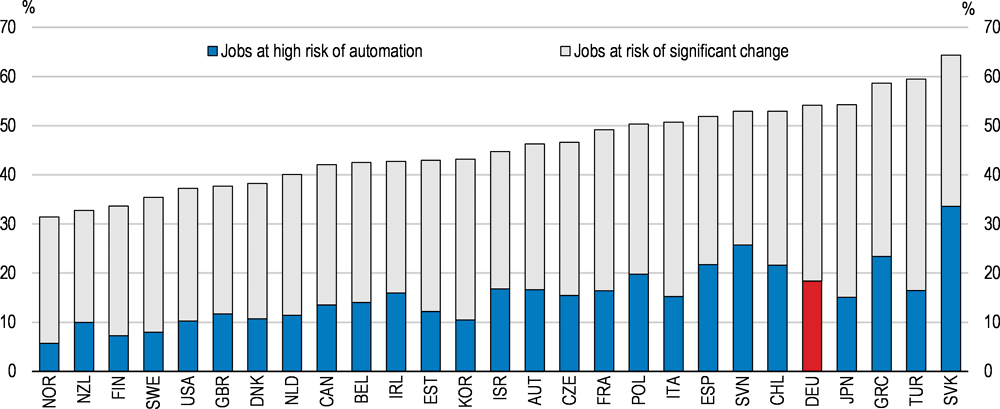

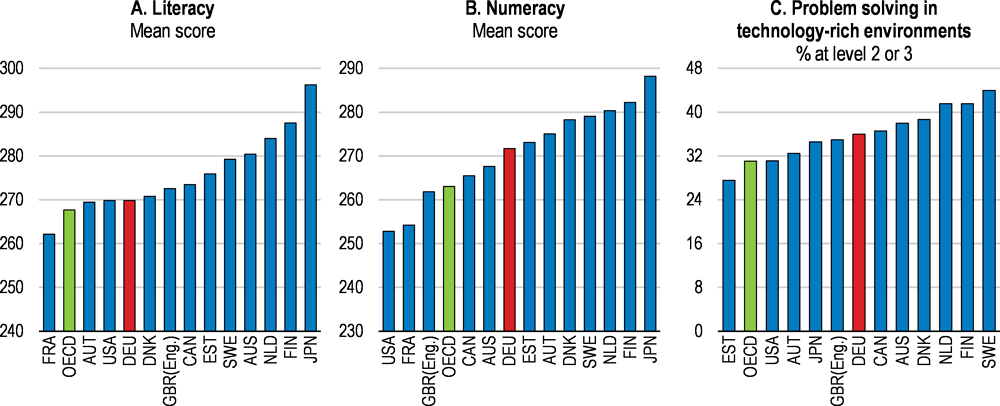

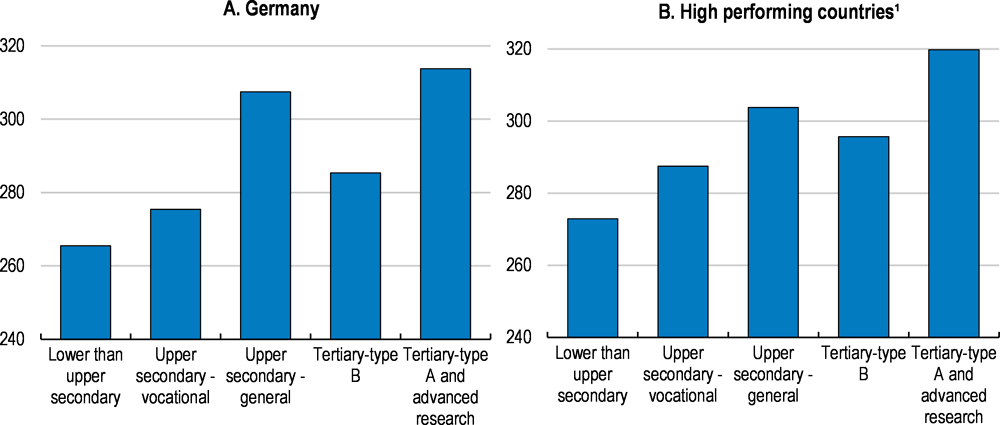

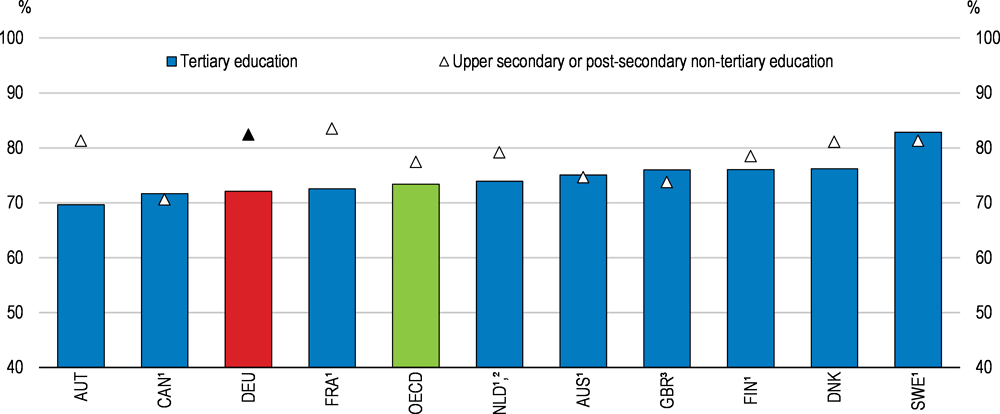

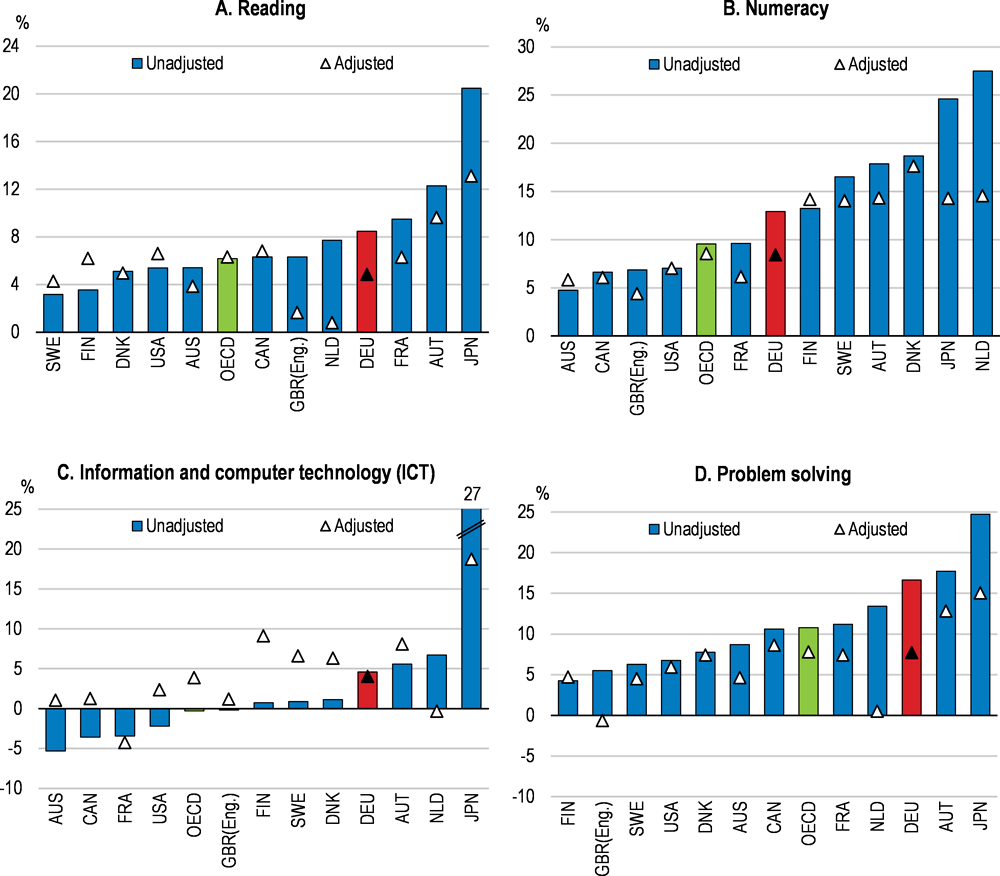

Skills are becoming more important as technological change and globalisation are advancing. A skilled workforce, reflecting in part Germany’s renowned vocational education and training system and strong science and engineering skills, have delivered high labour productivity, especially in the manufacturing sector, good job quality (OECD, 2017[2]) and an excellent integration of young people in the labour market (Figure 6). However, cognitive and digital skills among the adult population are weaker and more dispersed than in leading OECD countries. Germany has undertaken impressive education reforms which have improved outcomes for disadvantaged youth, but scope remains to reduce the impact of socio-economic and immigration background further. Efforts are undertaken but need to be stepped up to reduce inequality of market incomes and poverty risk, improve upward social mobility and boost economic growth overall (OECD, 2015[3]).

Figure 6. Most German youth are either in employment, education or in training

Youth not in employment, education or training (NEET), per cent of 15-29, 2016 or latest year¹

1. 2015 for Ireland and Chile. 2014 for Japan.

2. Unweighted average.

Source: OECD (2017), "Education at a glance: Educational attainment and labour-force status", OECD Education Statistics (database).

Against this backdrop, the main messages of this Economic Survey to increase living standards for all are:

New technologies must be exploited more extensively to boost wellbeing and productivity, with benefits for the whole society. Boosting entrepreneurship especially among women, wider access to high-speed Internet and strengthening digital skills would allow faster and more sustainable adoption of new technologies.

Accelerated skill-biased technological change requires workers to be ready to adapt throughout their life time, including through strong skills and life-long learning. Better use of workers’ skills, especially among women, can also boost productivity.

Enhancing education opportunities for people with weak socio-economic background would help ensure that technological change brings better access to economic opportunities to all. Labour market regulations and social safety nets need to adapt to the changes new technologies bring to the labour market, so their benefits can be broadly shared.

The coalition agreement of the new German government (Box 1) addresses some of these challenges and includes some steps towards the recommendations developed below, notably by proposing to strengthen education and skills, lowering the taxation of low wage incomes, strengthening innovation and entrepreneurship, and addressing environmental challenges in transport. As recommended in this Survey it also aims at using fiscal space for this purpose.

Box 1. Key features of the programme of the new government

The coalition agreement between the two conservative parties (CDU and its Bavarian ally CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD) includes a comprehensive overview of planned measures and additional government spending for these purposes.

Government spending: The political objective of a balanced headline budget is kept. Budgetary space in the federal government’s budget is estimated at EUR 46 billion (1.5 % of GDP; envisaged to be spent almost entirely in the three year period of 2019-2021). Of it 8 billion are planned to be given as support to the Länder to relieve them for the costs of integrating refugees. Priority spending areas are education, family benefits and pensions. In addition, revenues from auctioning 5G licences will be used for investment in high-speed broadband infrastructure and digital equipment of schools. Surpluses in the social security system will be reduced to lower social security contributions.

Tax policy: The government intends to reduce the unemployment insurance contribution rate by 0.3 percentage points, shift about 0.5 percentage points of health insurance contributions from employees to employers, and to reduce employee-paid social security contributions for low-paid workers above the mini-job income threshold of EUR 450 (midi-jobs). Steps to raise the taxation of interest income received by households to the standard income tax rate are envisaged. From 2021, income tax reductions worth EUR 10 billion, mostly for middle-income households, are planned.

Labour market policy: The government plans to reduce the scope for fixed-term contracts. A legal right for temporary limited part-time work, with the right to return to the previous working hours in companies employing more than 45 employees, will be introduced. In order to reduce long-term unemployment the government aims to strengthen active labour market policies. The government plans to introduce an immigration law to facilitate immigration of skilled workers. The agreement proposes to strengthen participation of women in executive positions in the private and public sector. The government plans to subsidise domestic services in private households to promote reconciliation of work and family life, and to foster regular employment in this sector.

Pension reform: The government intends to keep the pension benefit replacement rate constant at 48% until 2025 while limiting pension contributions to 20%. This may have little effect on pension spending before 2025. For the time after 2025 a pension reform commission will be set up to investigate how to stabilise pension contributions and benefits. Furthermore a new basic pension will be introduced for people with long contribution records. They will receive a retirement income exceeding social assistance benefits by 10%, subject to a means test. Disability pension entitlements and pension entitlements for mothers who have raised 3 or more children will be increased. The government plans to introduce compulsory pension insurance for the self-employed, eventually including them in the public pay-as-you-go pension scheme with an opt-out possibility.

Innovation and entrepreneurship: The government plans to raise R&D spending from currently below 3.0% to 3.5% of GDP by 2025. The High Tech Strategy will be further developed and focus on digitalisation and artificial intelligence (AI). In order to incentivise private R&D spending, especially within SMEs, the introduction of tax incentives will be considered. To facilitate start-ups, the government plans to introduce a “One-Stop-Shop” and a VAT exemption for the first years after starting a business. It will also examine further tax incentives for venture capital. Public health care insurance contributions for low-income self-employed workers will be reduced.

Child care, education and skills: The government plans to improve child care and school education, including full-day care and schooling. By 2025, a legal right to primary full-day school places will be introduced. Schools will be better digitally equipped. To address needs due to technological change and strengthen ICT skills, a national life-long learning strategy with social partners will be put in place. Furthermore programmes will be introduced to upgrade skills in vocational education and address challenges from digitalisation, including a "digital pact for schools" (Digitalpakt Schule), the "vocational education and training pact" (Berufsbildungspakt) and an updated “Alliance for Initial and Further Training" (Allianz für Aus- und Weiterbildung). In addition the government plans to increase grants for adults in life-long learning. It also envisages introducing minimum apprenticeship pay. Challenges related to digitalisation and the upgrading of skills for the future of work are widely recognised in Germany`s coalition agreement where these challenges are addressed accordingly.

Family benefits: The agreement proposes to raise family benefits (child benefits, child benefit supplements for low income households and child tax allowances as well as better in-kind benefits for low-income families e.g. for school lunch). The government plans to target additional education support to pupils from low-income households. Furthermore it plans to introduce substantial tax incentives and grants for private home purchases for families with children (EUR 1 200 per child per year for maximum of ten years).

Climate policy: The government intends to implement additional measures to reduce the gap in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions with respect to the 2020 climate goal. To meet the 2030 GHG emission target, it envisages reducing coal-fired energy generation while supporting structural change in the affected regions. Low emission transport policy will be strengthened (rail, public transport, low- and zero emission mobility, support for car sharing). Measures to improve air quality especially in cities will be implemented. Among other things, the government wants to increase the purchase bonus (Umweltbonus) for low-emission light commercial vehicles and taxis and to expand the charging infrastructure for cars to facilitate electric transport. The government also plans to introduce digital test fields for autonomous driving and open transport regulation for new shared mobility services.

Economic growth has been robust

Germany’s recovery from the global financial and economic crisis has been stronger than in the euro area as a whole (Figure 7, Panel A). Past structural reforms have increased the resilience of the German economy. Germany has benefited from its status as a safe heaven, which results in capital inflows when other euro area countries experience financial or fiscal difficulties. Residential investment has expanded strongly. Exports have gained momentum and business investment is accelerating in the context of the euro area recovery (Figure 7, Panel B). Unusually among high-income countries, German exporters have maintained market shares (Figure 7, Panel C). However the euro exchange rate has also strengthened somewhat recently.

Figure 7. Growth has been strong

1. Euro area countries which are OECD members.

2. Includes Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. The weighted sum of growth rates of their GDP in volume is used for the aggregate.

3. Export performance is measured as the ratio of actual export volume to the country’s export market size.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

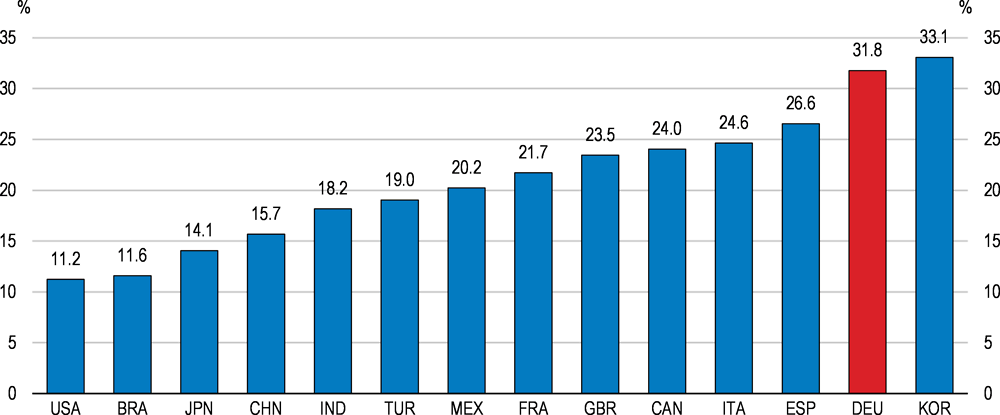

The strong export performance relies on the highly innovative manufacturing sector that is deeply integrated in global value chains (GVCs). For a large economy, Germany earns an unusually high share of value added from foreign final demand (Figure 8). German firms supply high value added goods, with a marked specialisation on capital goods. Global demand for capital goods has strengthened over the past 15 years, in the context of the increasing weight of emerging economies. German firms specialise in highly complex, technology-intensive goods which compete less with exports in emerging economies, such as China (Figure 9). Large German manufacturing firms have expanded their global production networks, incorporating more foreign value added (Figure 10). This has helped retain competitiveness and penetrate dynamic emerging markets.

Figure 8. Germany draws high value added from participation in global value chains

Share of domestic value added embodied in foreign final demand, % of total domestic value added, 2014

Note: Domestic value added embodied in foreign final demand captures the value added that industries export both directly, through exports of final goods or services, and indirectly via exports of intermediates that reach foreign final consumers (households, government, and as investment) through other countries.

Source: OECD (2018), "TiVA Nowcast Estimates" in OECD International Trade and Balance of Payments Statistics (database).

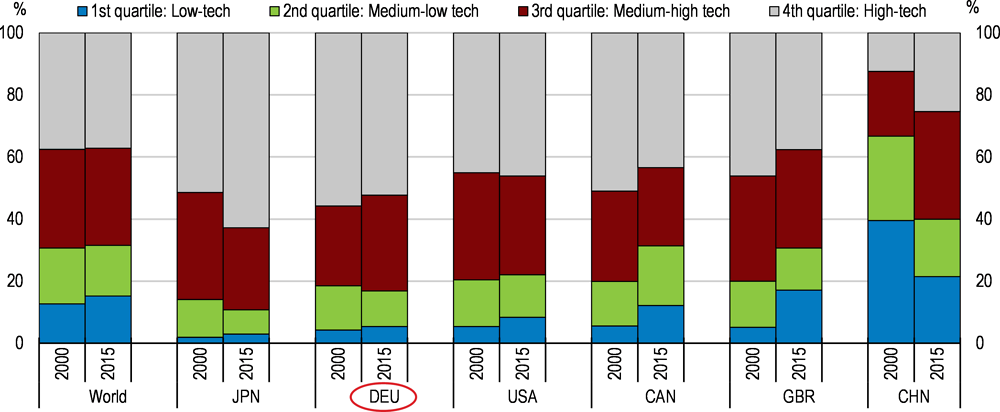

Figure 9. Germany's exports are strong in high-tech goods

Share of export by complexity quartile, 2000 and 2015

Note: Complexity is defined by the implied productivity of the product (PRODY) using the methodology of Hausmann, R., J. Hwang and D. Rodrik (2007), “What you export matters”, Journal of Economic Growth, Springer, vol. 12(1). PRODY is calculated by taking a weighted average of the per capita GDPs of the countries that export the product. The weights are the revealed comparative advantage of each country in that product. The products are then ranked according to their PRODY level. An example of product in the 4th (highest) quartile is magnetic imaging resonance (MRI) machines used in scans in hospitals which ranked 18th in 2015, out of 4989 products listed in the Harmonized System 6 classification. A product in the 1st (lowest) quartile is crayons ranked 4218th in 2015. The analysis is carried out using a high level of product disaggregation to try to capture specialisation at different stages of the production chain.

Source: OECD (2018), "OECD Economic Outlook No. 102 (Edition 2017/2)".

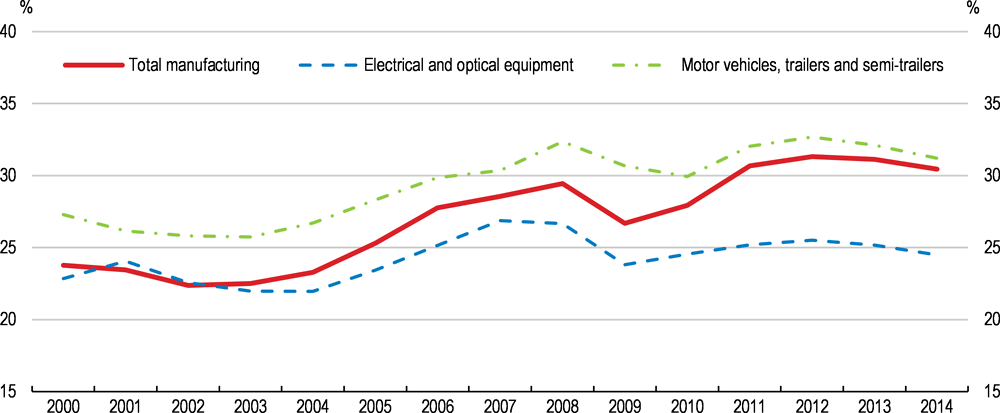

Figure 10. The manufacturing sector has increased its global sourcing

The share of foreign value added embodied in gross exports

Note: Data from 2012 to 2014 are TiVA nowcast estimates, which are extended estimates of the "Trade in Value Added (TiVA)" database based on more recent trade flow data.

Source: OECD (2018), "Trade in Value Added - December 2016" and "TiVA Nowcast Estimates" in OECD International Trade and Balance of Payments Statistics (database).

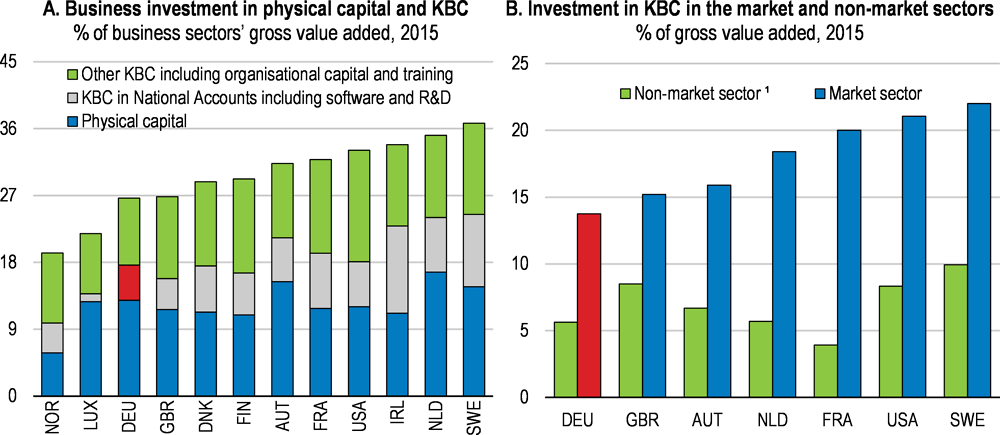

Business investment is picking up as capacity utilisation is above long-term average. Also confidence and demand in the euro area have strengthened, contributing positively to growth in Germany. But business expenditure on knowledge-based capital (KBC), including software and databases or firm-sponsored training, remains lower than in leading OECD countries (Figure 11). Spending on these intangible assets has become an increasingly important driver of productivity (OECD, 2015[4]).

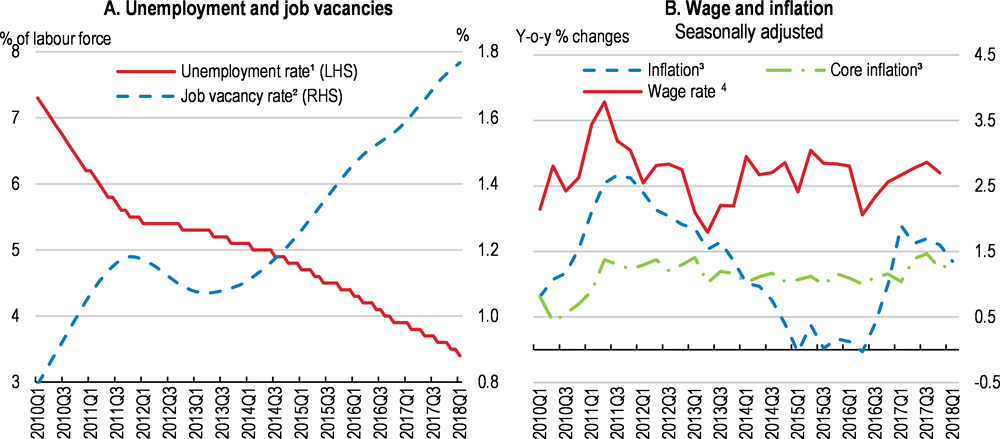

Vigorous employment growth has pushed the unemployment rate to a record low, while the number of vacant jobs is rising strongly (Figure 12, Panel A). Jobs in long-term care and jobs related to construction have recorded the longest vacancy durations. Employment growth, low unemployment and real wage growth underpin household consumption. Residential construction has picked up markedly, boosted by the housing needs of immigrants, higher household incomes and low interest rates.

Figure 11. Investment in knowledge-based capital (KBC) is lower than in leading economies

Note: The non-market sector consists of the following NACE Rev. 2 sections: (1) public administration and defence; (2) education; and (3) human health and social work activities, (4) scientific research and development and (5) arts, entertainment and recreation.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2017: The digital transformation.

Rising wages, especially at the bottom of the wage distribution, are welcome as this will reduce worker poverty and further strengthen domestic demand. While wages are growing above inflation and productivity, they have not grown as much as could be expected on the basis of historic norms, given low unemployment (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2016[5]). This could be explained by declining collective bargaining coverage. It may have reduced wage growth by about 0.2 percentage points annually (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2016[5]). In some sectors, wage growth is still influenced by more modest collective agreements negotiated some years ago.

Recent collective bargaining outcomes suggest a modest acceleration of wages. In the metal industry, where unions remain relatively strong, negotiated wages will rise by about 3% on an annual basis. In sectors where collective bargaining is still ongoing, unions have demanded around 6% higher wages, somewhat more than in earlier years (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2018[6]). Unions have increasingly negotiated non-wage benefits, such as better work-life balance, by giving workers more leeway to reduce working time (with a proportional cut in pay), for example, to look after children. Immigration may have reduced the extent to which wage growth responds to domestic unemployment. The trend increase in the dispersion of wages in past decades has not continued in recent years. Low-pay workers have benefited from the gradual introduction of the minimum wage in all sectors since 2015, and a tight labour market has diminished competition for jobs with low skill requirements.

Real wage gains diminished as consumer price inflation rose in 2017 (Figure 12, Panel B) mostly reflecting higher oil prices. Core inflation also rose to 1.5%, reflecting spillovers from oil prices, notably in transport services, as well as higher capacity utilisation (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2018[6]). In recent months inflation has not risen further. Credit growth also remains modest. However, capacity utilisation in industry has climbed well above historic averages. Capacity constraints appear most binding in construction where prices have risen significantly. Immigration is allowing employment to expand despite low unemployment. On aggregate, despite a tight labour market and supportive fiscal and monetary policy conditions, there is so far little sign of overheating.

Figure 12. The labour market is tight but nominal wage growth has remained broadly stable

1. Population aged 15-74 years. Based on the German labour force survey.

2. Percentage of unfilled job vacancies relative to total employment.

3. Harmonised consumer price index (HICP). Core HICP excludes energy, food, alcohol and tobacco.

4. Average nominal wage per employee.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) and Statistisches Bundesamt.

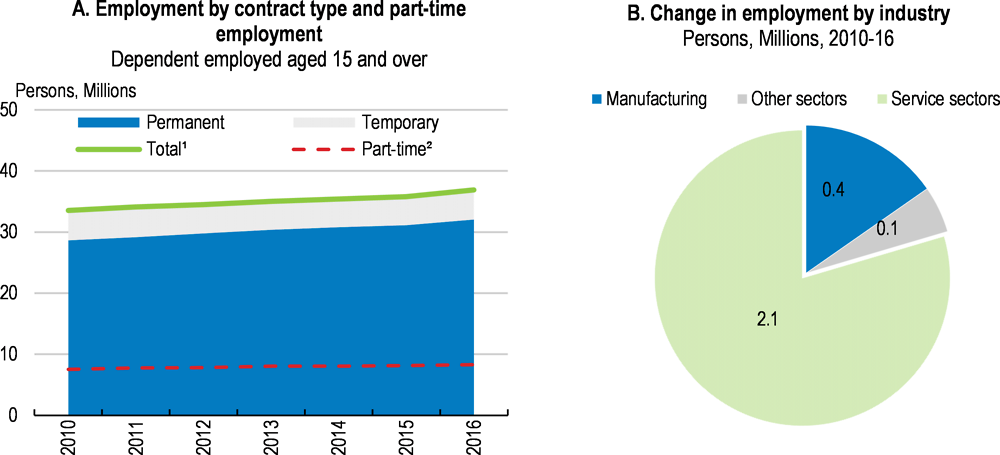

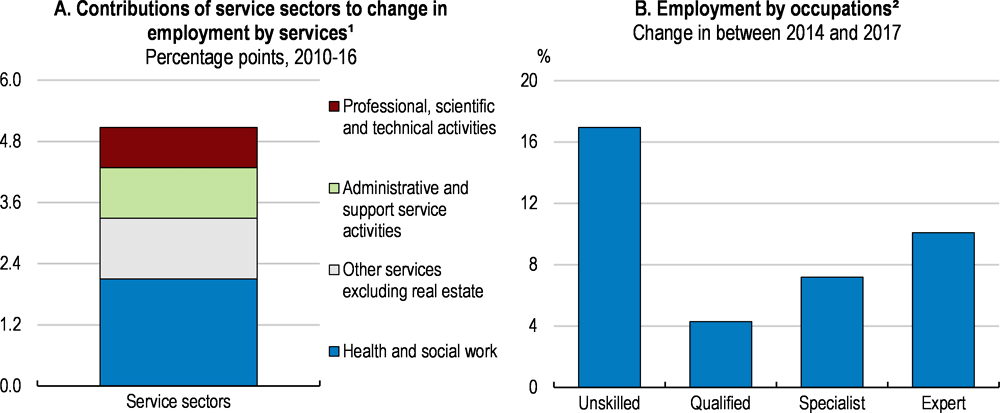

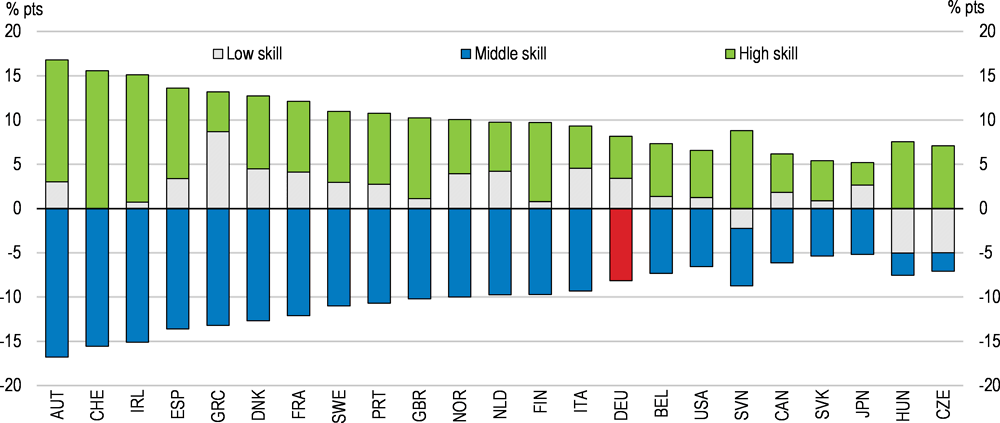

Most new jobs are full-time permanent contracts (Figure 13), which is welcome, as non-regular forms of employment are typically less productive and raise in-work poverty risks. Expanding labour supply has fed most of the employment gains, notably immigration. Hours worked among women have risen, in part reflecting expanding childcare, but most employed women continue to work part-time. Employment has mostly grown in services. Health services, professional services and support services have contributed strongly (Figure 14 panel A). Data shows that professional services provide high value-added activity and highly paid jobs, while health and support services provide many low value-added and low-paid jobs, for example, in long-term care, cleaning, security. Employment growth has been strongest for jobs with the high skill demands (experts and specialists) as well as with the lowest skill demands (Figure 14, Panel B). The impact of skill-biased technological change may have contributed (see below). Employment of immigrants and formerly unemployed workers may also have made it easier to fill vacancies for low-skill jobs.

Immigration, mostly from other EU countries, remains strong and includes many highly skilled young workers. By contrast, most of the about 1 million refugees, mostly from the middle-east and Africa, who arrived in 2015 and 2016, have no recognised qualifications.

Germany has taken strong measures to facilitate labour market entry for refugees (2016 Economic Survey of Germany). In general, refugees may start working three months after registration. They also have access to preparatory courses to enter the vocational education and training system. Incentives to obtain qualifications have also been improved by offering guarantees to stay at least two years following completion of a vocational qualification to refugees with otherwise uncertain perspectives to stay. German language classes, support for integration in schools and counselling services have been stepped up. Language programmes integrate general and job-related language learning. Skills assessment has been reinforced (OECD, 2017[7]). Efforts continued in 2017 to help young refugees and migrants enter and complete vocational training, for example with programmes to support all youth with weak socio-economic background, including mentoring and coaching. In addition refugee recruitment advisors (“Willkommenslotsen”) help companies to find trainees among the refugees. Further steps could however be taken to open labour markets more generally, including by facilitating business creation, notably in the construction-related crafts, which can attract many immigrants and where there are capacity constraints (see below and the 2016 Economic Survey of Germany). The inflow of refugees diminished sharply in 2017.

Figure 13. Most jobs created are full-time permanent jobs and are in the service sector

Note: Based on labour force surveys.

1. Total employment is calculated as the sum of permanent and temporary employment and it is slightly different to the sum of full-time and part-time employment. The difference is 0.1%.

2. Part-time employment is defined as people in employment who usually work less than 30 hours per week in their main job

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database) and OECD National Accounts Statistics (database).

Figure 14. Jobs with the highest and the lowest skill demands have grown strongly

1. Based on labour force surveys for Panel A.

2. Unskilled jobs include simple tasks requiring little skill. Qualified jobs contain more complex tasks requiring intermediate vocational skills. Specialist jobs include highly complex and managerial tasks, typically requiring higher vocational skills. Expert jobs include the most knowledge-intensive tasks, typically requiring an advanced university degree.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD National Accounts Statistics (database) and the Federal Employment Agency of Germany.

Economic growth is expected to slow somewhat, as capacity constraints have been reached, including in the labour market (Table 1). Strengthening world trade and the recovery in the euro area are projected to sustain exports. The tight labour market will continue to boost private consumption. Wage growth is projected to pick up, although the response to tight labour market conditions will be damped by lower collective bargaining coverage in the services, immigration and the expansion of low-skill jobs. Consumer price inflation may rise modestly as higher wages can be absorbed in comfortable business profit margins. Remaining slack in some trading partners, notably in the euro area, may also damp inflation. A deterioration of exports, for example, as a result of protectionism affecting world trade or lower demand from China, could weaken economic prospects (Table 2). There are also downside risks related to the impact of the exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union, as it may disrupt the value chains in key German industries, including automotive production and chemicals. On the other hand, some businesses have announced they will transfer activity to Germany.

Table 1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2010 prices)

|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

20181 |

20191 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (billion EUR) |

||||||

|

Working-day adjusted GDP |

2,937.0 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

2.5 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

|

Private consumption |

1,595.5 |

1.6 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

|

Government consumption |

563.9 |

2.9 |

3.7 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

2.0 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

588.4 |

1.0 |

2.9 |

3.9 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

|

Housing |

172.7 |

-1.1 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

2.6 |

3.1 |

|

Business |

355.1 |

1.4 |

2.5 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

4.4 |

|

Government |

60.6 |

4.5 |

2.6 |

4.6 |

0.6 |

3.1 |

|

Final domestic demand |

2,747.9 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

2.4 |

1.6 |

2.2 |

|

Stockbuilding 2 |

-15.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

2,732.6 |

1.5 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

1,344.2 |

4.7 |

2.4 |

5.3 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

1,139.9 |

5.2 |

3.8 |

5.6 |

4.3 |

5.1 |

|

Net exports 2 |

204.4 |

0.1 |

-0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

||||||

|

GDP without working day adjustment |

2,932.5 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

1.5 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

|

Output gap 3 |

. . |

0.2 |

0.4 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

|

Employment |

. . |

0.8 |

2.4 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

|

Unemployment rate 4 |

. . |

4.6 |

4.2 |

3.7 |

3.4 |

3.3 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

2.0 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

2.1 |

|

Consumer price index (harmonised) |

. . |

0.1 |

0.4 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

2.0 |

|

Core consumer prices (harmonised) |

. . |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

2.0 |

|

Household saving ratio, net 5 |

. . |

9.6 |

9.7 |

9.9 |

9.9 |

10.0 |

|

Current account balance 6 |

. . |

9.0 |

8.5 |

8.1 |

8.3 |

7.9 |

|

Government primary balance 6 |

. . |

1.8 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

|

General government fiscal balance 6 |

. . |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance 3,7 |

. . |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance 3,7 |

. . |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht) 6 |

. . |

71.1 |

68.4 |

64.0 |

60.7 |

57.9 |

|

General government gross debt (national accounts definition) 6 |

. . |

79.2 |

76.5 |

71.7 |

68.4 |

65.6 |

|

General government net debt 6 |

. . |

43.0 |

41.1 |

36.6 |

33.8 |

30.9 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

0.0 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

0.5 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1. Projections

2. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

3. As a percentage of potential GDP.

4. Survey-based unemployment rate following the definition of the the International Labour Office.

5. As a percentage of household disposable income.

6. As a percentage of GDP.

7. The underlying balances are adjusted for the cycle and for one-offs.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), May.

Table 2. Possible shocks and their economic impact

|

Shock |

Possible outcome |

|---|---|

|

Rising protectionism in trade and investment. |

Lower world trade would hit German exports and investment, which could feed to lower private consumption and employment. Global value chains, in which Germany is closely integrated, would be disrupted. Exports to key trading partners outside the euro area (United States, China) could be particularly affected. |

|

Demand for German products in China could weaken markedly in the context of a financial crisis in China. |

Exports and the value of the stock of German foreign direct investment would fall, with a negative impact on investment, employment and private consumption. |

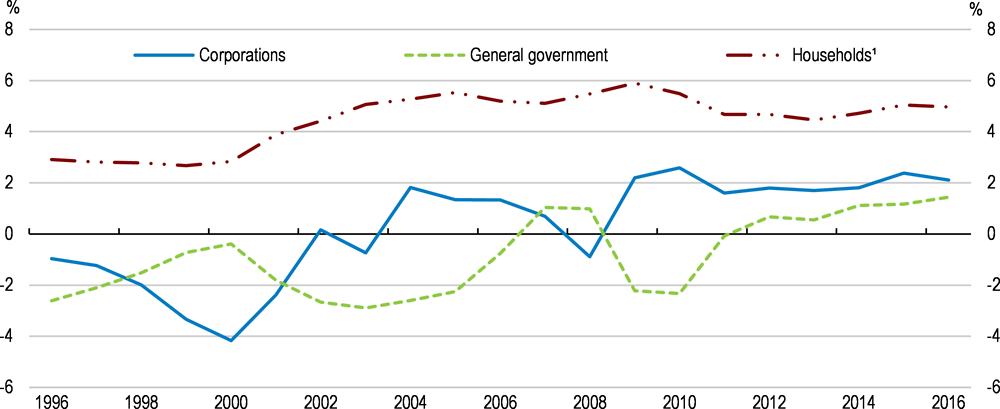

The current account surplus remains large

Germany’s current account surplus remains large. It correlates strongly with global demand for capital goods (Grömling, 2014[8]). The large external imbalance reflects excess saving by households, corporations and government (Figure 15). The saving-investment balance has risen in the government sector and in the corporate sector, where retained earnings have risen more than investment. Investment has fallen among large corporations quoted in the stock market (OECD, 2016[9]). German firms increased their equity to strengthen resilience to external shocks. One important factor contributing to boosting corporate savings has been the deep integration of German firms into global value chains through foreign direct investment and the associated profits of foreign affiliates. Excess saving by non-financial corporations is also observed in many other high-income countries.

A large part of the current account surplus can be attributed to structural factors like demographics, a competitive industry and the specific composition of German exports. In 2017, about 25% of the German current account surplus can be attributed to a surplus in the primary income balance, reflecting the income earned on Germany’s large net international investment position. At the same time, the 2016 Economic Survey identified barriers to the reallocation of resources, restrictive regulation in some services, skills shortages and uncertainty about prospects in the euro area as factors holding back domestic investment in Germany, including investment in knowledge-based capital.

Several policies recommended below that boost productivity and inclusiveness can reduce the current account surplus by stimulating investment and consumption. Policies which promote investment, entrepreneurship, the diffusion of new technologies, and skills, as recommended further below and in previous OECD Economic Surveys, would increase investment, as would using fiscal space to increase public investment in key infrastructure. However, such steps could also boost competitiveness in the long-term. Tax reductions on low wage earnings would boost private consumption. Policies that increase labour market participation and reduce poverty risks can also reduce precautionary savings. In particular, reforms that remove barriers to women’s full time employment and to better careers would protect households better against poverty risk. Policies to improve income prospects at older age would also reduce the need for households to save to prepare for old-age. This includes better opportunities for upskilling, stronger incentives to work at higher age, better insurance against income risks from disability and better access to low-cost pension annuities (see below).

Figure 15. Excess savings in the corporate and government sector increased

Saving-investment balances by sector as % of GDP

1. Includes non-profit institutions serving households.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2018), OECD National Accounts Statistics (database).

Low interest rates and high leverage are potential risks to the financial market

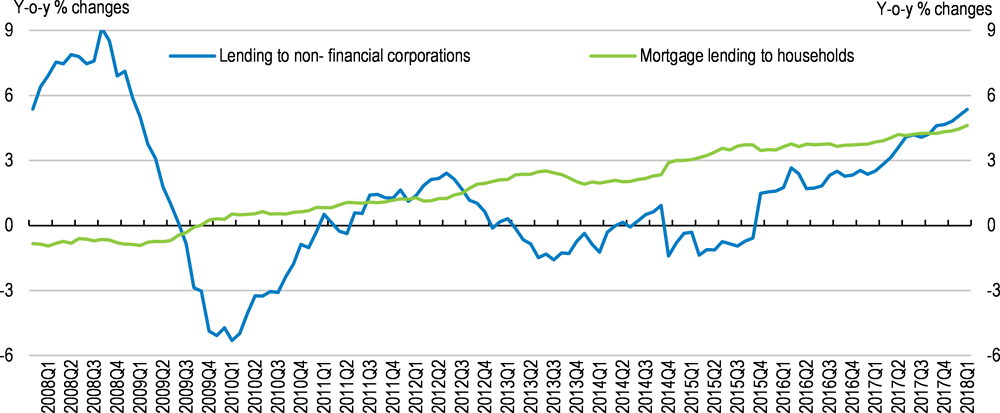

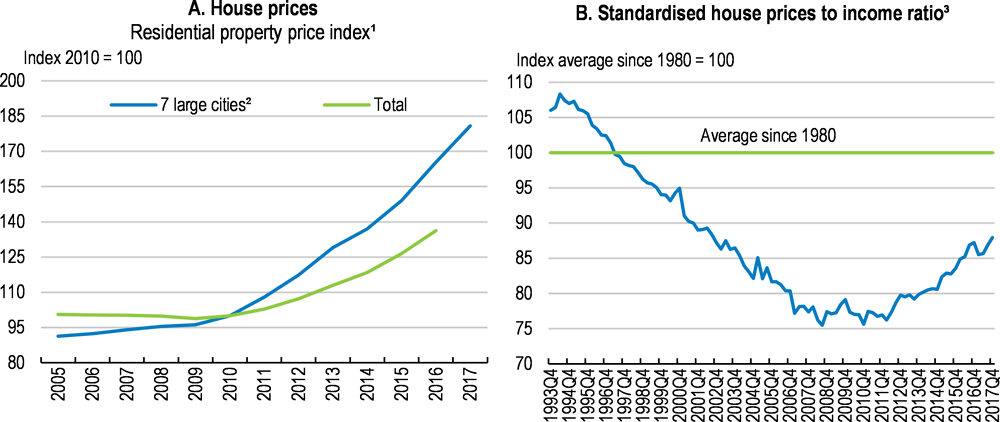

Lending to non-financial corporations and to households has picked up (Figure 16) but growth remains broadly in line with nominal GDP. The share of nonperforming loans is low. Banks have stepped up precautions against sudden changes in interest rates (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017[10]).

House prices have risen fast, especially in major cities (Figure 17, Panel A). So far, overall increases are primarily driven by fundamental market forces, notably housing demand and lower interest rates (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017[10]). Only in the major cities are prices higher than implied by fundamental market forces. The ratio of house price to household income is still lower than the long-run average (Figure 17, Panel B). Banks have not eased credit standards for housing loans (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017[10]).

The Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) has been given powers to take macroprudential measures such as ceilings on loan-to-value ratios. This is timely as risks related to the housing markets may arise in the future. However, imposing a ceiling on the loan-to-value ratio may not always be effective to halt a credit-driven price bubble, as a stable loan-to-value ratio may be consistent with high growth of both lending and house prices (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017[10]). The macroprudential toolkit can be strengthened by including a cap on the ratio of a borrower’s debt servicing relative to income. Such a cap was recently introduced in Denmark and Norway and is envisaged in Sweden.

The Bundesbank provides analysis to prepare macroprudential decisions. Its analysis must prove that banks’ lending practices pose macroprudential risks. However, it cannot conduct surveys of financial institutions on individual banks’ housing-related lending practices on a regular basis. It is important that the Bundesbank be able to collect such data regularly.

Figure 16. Credit growth is picking up

Growth of lending to non-financial corporations and mortgage lending to households

Figure 17. House prices are rising but remain broadly in line with income growth

1. Bundesbank calculations based on price data provided by Bulwiengesa AG.

2. Berlin, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Cologne, Munich and Stuttgart.

3. The nominal house price is divided by the nominal disposable income per head. It is standardised by being divided by the long-term average as a reference value over post-1980.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Analytical House Price Statistics (database) and Deutsche Bundesbank.

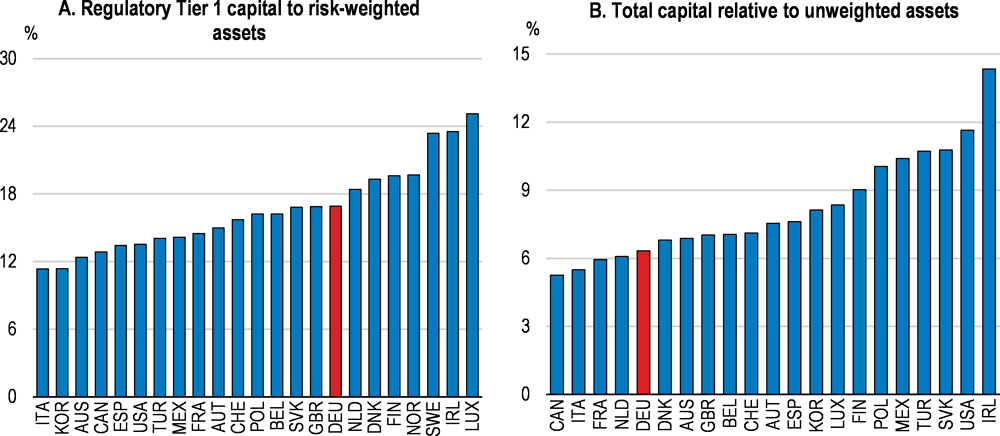

Bank capital relative to risk-weighted assets has increased. It is still lower than in some countries, but most of these have had to take macroprudential steps to prevent excessive housing-related lending (Figure 18, Panel A). Large banks calculate the risk weights of their assets with internal models, which may result in excessively good capital ratios (e.g. the (German Council of Economic Experts, 2016[11]). The rules concerning risk weights in internal risk models have recently been tightened somewhat in the context of the Basel III agreement.

Banks are still highly leveraged. The unweighted capital ratio of banks in Germany remains lower than in many OECD countries (Figure 18, Panel B). Leverage is particularly high in the largest banks. The seven largest banks’ leverage ratio (following the definition in the capital requirements regulation which banks have to fully implement by 2022) amounted to 3.7% mid-2017. Since the new tools to resolve globally active systemically-important banks in financial distress are still untested, the low capacity of equity to absorb losses exacerbates the distorting impact of implicit government guarantees. The perception that too-big-to-fail banks may be rescued by the government in case of distress can lead to excessive risk-taking by the banks, impair the quality of their lending, put taxpayers’ wealth at risk and aggravate the destabilising macro financial effects of asset price fluctuations. The authorities should induce banks to further strengthen capital buffers where necessary.

Figure 18. The capital to asset ratio is low

2017 or latest year¹

1. 2016 for Italy, France, Switzerland, Belgium, the United Kingdom and Norway and 2014 for Korea.

Source: IMF (2018), IMF Financial Soundness Indicators Database.

The exposures to derivatives can be a factor in propagating systemic risks, as they raise interconnectedness between institutions, especially to the extent that the derivatives are not centrally cleared. The rapid growth in derivatives trade in the past has been motivated not only by the need to hedge risks but by tax and regulatory arbitrage and speculation (OECD, 2014[12]). Derivative positions are concentrated in large banks, aggravating the risks associated with high leverage. The weight of derivatives in their assets has declined but still amounts to around 20%. Germany has introduced legislation to separate retail banking from investment banking, but the separation requirements could be more effective, as argued in the 2014 Economic Survey. Steps by the German government would be particularly timely as the European Commission has abandoned plans to legislate separation requirements at the EU level. Such steps may help change the strategic relation between the supervisory authorities and the banks, with the supervisor being less under pressure to stand behind a systemically important bank when it faces problems, as relatively smaller and less complex banks tend to be easier to resolve if in distress.

As the 2014 Economic Survey pointed out, the regional Landesbanken, which are mostly owned by Länder governments, have had a poor track record in efficiency and vulnerability to solvency risk. Profitability has remained substantially weaker than in other banks since 2012 (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017[13]). Their balance sheets have shrunk by 40%, but they remain important banks, with assets worth about 30% of GDP. Owing to their strong financial links with other banks, notably the savings banks, and their role in interbank lending, they have a substantial systemic weight. One Landesbank merged. Another Landesbank is in the process of privatisation, after it failed to meet requirements by the European Commission. The two Länder governments owning this Landesbank will make losses on account of the support they provided over the past ten years. These losses may amount to about 5% of the GDP of the two Länder’s GDP.

Regional government ownership of the Landesbanken has caused a governance problem due to the international nature of their business. Landesbanken have supported shipping in Northern Germany, holding back the reallocation of resources. Further progress in their privatisation could also reduce risks and facilitate the exit of banks with poor profitability (OECD, 2016[9]; OECD, 2014[12]).

Fiscal policy can help address structural challenges

Germany’s budgets are governed by top-down and multi-year budgeting. They are bound by a structural general government medium term deficit objective of 0.5% of GDP agreed with the European Union. According to national constitutional rules, a structural deficit limit (0.35% of GDP) applies to the federal government and, from 2020 onwards, balanced budget rules to the Länder. The Stability Council (Stabilitätsrat), a joint body representing the German federal government and the Länder, monitors their budgets and the social security system. It is tasked with making sure that these, taken together, comply with the medium-term objective and, if necessary, issues recommendations. The Stability Council is assisted by an independent advisory board. A panel of independent experts provides revenue projections which guide government budgeting.

Tax revenues relative to GDP amount to 38% of GDP, more than in the OECD on average (34%). This ratio has increased in recent years, partly reflecting bracket creep. The fiscal position is sound and the general government budget has been in surplus since 2014. According to OECD projections, government gross debt (Maastricht definition) is expected to fall below 60% of GDP in 2019 and net debt close to 30%. According to government estimates the general government structural budget balance may amount to a surplus of 0.75% of GDP in 2019, though without incorporating the budgetary measures foreseen by the new government. Structural surpluses are also expected in the federal government budget and in the social security system. The OECD estimates the new measures to reduce the general government surplus by 0.25% of GDP in 2018 and 2019. Although the timing of the measures is uncertain, social security contributions are likely to be reduced and subsidies for families purchasing owner-occupied housing are likely to be introduced in the near term. In addition spending to improve childcare provision, full-day primary schooling and schools’ digital equipment is expected to rise in 2018 and 2019. Income tax allowances and child benefits will also rise. Nonetheless, tax revenue growth is likely to increase the government surplus to 1.5% of GDP by 2019. Additional budget space consistent with meeting Germany’s budget rules could amount to 0.4% of GDP.

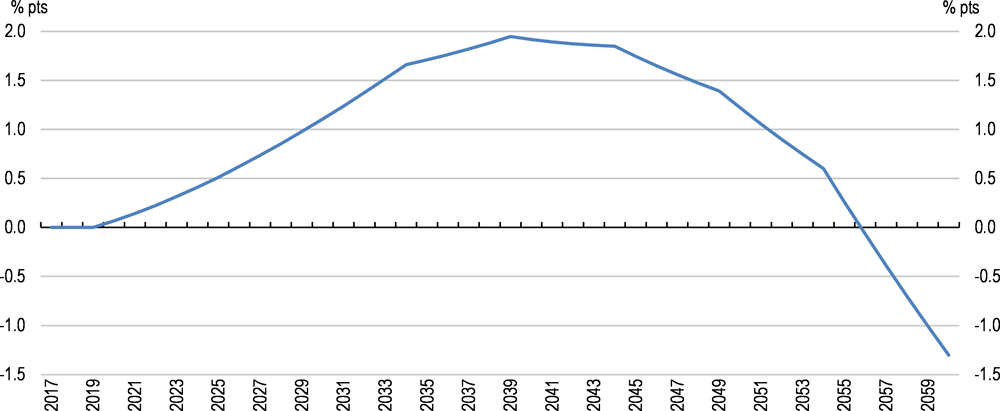

The strong fiscal position provides some room to fund additional priority spending in the near term. However, fiscal leeway should be used in a prudent manner, taking capacity constraints into account. Enrolling more young children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds in high-quality childcare and providing more full-day primary schooling are welcome spending priorities of the new government. A policy package which includes the budgetary and tax policies in Table 5 below and key growth-enhancing structural reforms (Box 2) would imply structural government deficits in the medium term, which would still be consistent with budgetary rules. The policy package would raise the ratio of government debt to GDP modestly in the medium term, and even reduce it in the long-term, reflecting the impact of the indexation of the statutory retirement age to life expectancy, which would lower pension spending (Figure 25 below). The baseline and reform scenario assume that commitments to budget rules are kept and do not assume that higher ageing-related spending increases the government deficit. Stronger support for young children is particularly effective to strengthen skills in the long term. Simulations suggest that investment in childcare, early childhood education and full-day schools could improve the sustainability of government finances in the medium and long-term, by boosting GDP growth and reducing the risk of benefit dependency when the children reach adulthood (Krebs and Scheffel, 2016[14]). These steps would also make it easier, especially for women, to reconcile family life and full-time employment. Policies to boost skills and gender equity have large potential to boost long-term growth (Box 2). By improving the earnings potential among individuals at the lower end of the skill distribution, boosting support for very young children may, in the long-term, help reduce the need for cash transfers to prevent poverty.

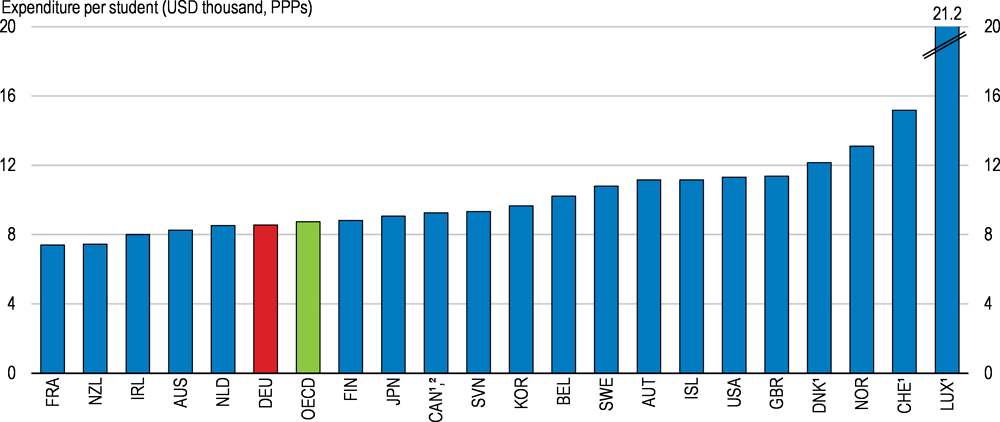

Spending on childcare and early childhood education is substantially lower than in Denmark or Sweden for example. Primary education spending is relatively low in comparison to other high-income countries (Figure 19). It is welcome that the government plans to address these priority spending areas.

Further improvements could in part be funded by remaining fiscal space and reducing tax breaks for households with children, while maintaining child cash benefits. As argued in the 2016 Economic Survey (OECD, 2016[9]), these tax breaks do not increase labour supply because they widen the gap in the taxation between first and second earner in a household. They do not reduce poverty significantly because they provide the most relief to high-income households. By contrast, better childcare and early childhood education reduce poverty and raise the labour supply of women the most. Child cash benefits have also proven effective in reducing poverty, especially the supplementary benefit for low income households (OECD, 2016[9]).

There is also scope to improve the efficiency of government funding for childcare and early childhood education. Most government funding is provided by Länder and municipalities. Some Länder and their municipalities reimburse individual institutions for their operating costs without consideration to the number of children attending. In others, funding of individual institutions includes a demand-based add-on (for example, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Schleswig-Holstein). Indeed, allowing the money to follow the children could strengthen incentives to offer formal childcare in locations and at times which suit parents, improving efficiency.

Other spending priorities include the rollout of high-speed fibre broadband infrastructure, which is poor, especially in rural regions, as foreseen in the coalition agreement. Accelerating rollout could improve economic development of rural regions which has fallen behind and boost GDP (Box 2). Spending on life-long learning and on low-emission transport infrastructure also needs to be stepped up (see below). The coalition agreement foresees subsidies for acquiring owner-occupied housing and higher pensions for mothers having raised three or more children in the past. These measures are not targeted to low-income households. This will limit the budgetary space available for spending that would support growth-enhancing structural reform.

Figure 19. Primary education spending is low

Annual public expenditure per student by educational institutions for all services, in primary education, 2014

1. Public institutions only.

2. Primary education includes data from pre-primary and lower secondary education.

Source: OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators.

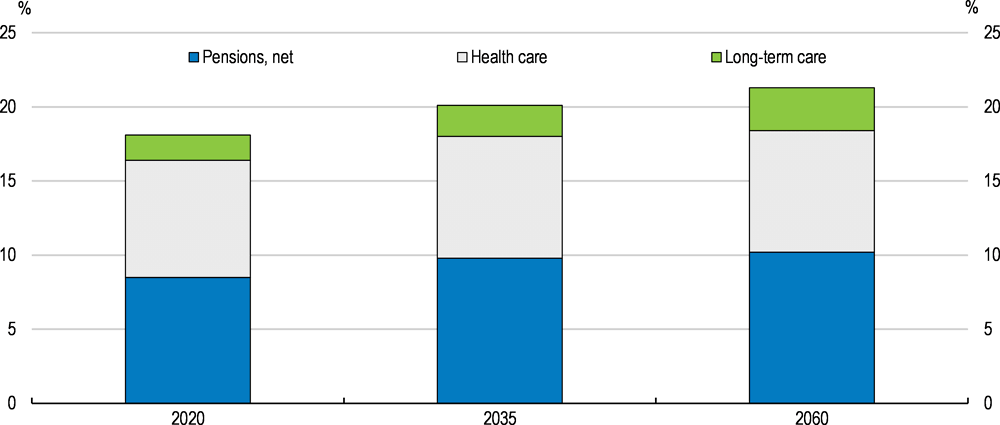

Ageing-related spending will increase, requiring better spending prioritisation

Looking further ahead, demographic change will increase the old-age dependency ratio and drive up public spending on old-age pensions, health and long-term care. The baseline scenario of the 2015 Ageing Report by the European Commission projects that spending could increase by almost 4% of GDP by 2060 (Figure 20), mostly driven by spending on pensions (net of taxes paid on pensions), and long-term care. These baseline scenarios broadly fall within the range of scenario projections by the German government. These also point to considerable uncertainty around projected spending beyond 2035. The temporary inflow of refugees in 2015-16 may reduce the increase of ageing-related spending only slightly, under the assumption that they are well-integrated into the labour market and stay in Germany durably (Federal Ministry of Finance, 2016[15]). By contrast, pension plans in the coalition agreement would further increase spending. Higher pension spending should be limited to reducing poverty risks.

Most of the increase in ageing related spending is projected to occur between 2025 and 2035, as the “baby boom” cohorts retire. However, in the long-term, the increase in ageing-related spending is mostly caused by gains in life expectancy. Since these gains are an ongoing process, resulting higher ageing related spending should not be prefunded with higher government surpluses today. Instead, structural reforms are necessary to provide workers with incentives and the capacity to extend working lives. Skills policies are critical in this regard (see below) and require higher government investment.

Figure 20. Ageing-related spending will increase

Projections on pensions, public health and long-term care spending as % of GDP

Source: European Commission (2015), "The 2015 ageing report: Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2013-2060)". Based on the reference scenario.

The statutory pension age will increase from age 65 in 2012 to age 67 by 2029 (meaning that people born in 1964 will only be able to retire with an unreduced pension in 2031). However, indexation of the retirement age to life expectancy, as recommended in the 2016 Economic Survey of Germany has not yet been introduced. It could reduce spending by 0.6% of GDP by 2060. Moreover incentives to work for longer still need to be strengthened by raising the pension premium for later retirement. According to OECD estimates postponing retirement still results in a loss of net pension wealth (OECD, 2017[16]). In many OECD countries, the premium for later retirement is large enough so retiring later increases net pension wealth. Germany could adopt a similar approach, as working for longer has social benefits, in addition to the private benefits for the worker who decides to postpone retirement. For example, longer working lives raise more tax revenue. Moving in this direction in Germany would therefore help raise income at high age while improving sustainability of government finances. It would also be inclusive as earlier retirement is often taken up by high-income individuals.

These steps need to be complemented by measures to lower income risks for workers who lose earnings capacity on account of disability before reaching retirement age, as the ageing process is unequal across socio-economic and professional backgrounds. Some progress has been made (Table 3). Indeed, poor health and low skills are important factors pushing older workers with weaker socio-economic status into early retirement. In addition, individuals with low lifetime income tend to have lower life expectancy, and Germany’s pension system does not redistribute except through taxation. Reflecting the increase in income inequality in past decades, inequality in health outcomes by socio-economic status is widening, and these differences are relatively large in Germany, according to an OECD assessment (OECD, 2017[17]). Old-age poverty is low, but the number of pensioners in relative poverty risk is expected to rise by 25% until 2035 (DIW/ZEW, 2017[18]). These points reinforce the case for limiting any increases in pension spending to steps which prevent old-age poverty, as recommended in the 2016 Economic Survey of Germany.

Länder governments bear part of the cost of pension spending, as they pay the pensions of their former civil servants. Most of Germany’s civil servants are employed by the Länder. To make sure the Länder take into account the financial burdens when they arise, they are required to build up reserves to cover pension commitments. However, the Länder have discretion as to how they calculate these reserves (Sachverständigenrat, 2017[19]). Since some high-debt Länder have benefited from bailouts by the central government in the past, incomplete budgeting of future pension commitments could result in moral hazard.

Table 3. Past recommendations and actions taken on pension reform

|

Recommendations |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Index the legal pension age to life expectancy. |

No action taken. |

|

Raise the pension premium for starting to draw old-age pensions later in life and do not reduce pensions for old-age pensioners who work. Allow working old-age pensioners to accrue benefits on social security contributions employers pay on their behalf. |

The pension premium remains unchanged. Since 2017, a partial pension and wage earnings can be combined in a more flexible and individual way. Wage earnings now reduce pensions by 40% only above a threshold of EUR 6 300 annually (previously the threshold was EUR 450 per month). Since 2017, individuals who continue to work after the statutory retirement age can choose to pay pension contributions and thereby accrue full benefits on all their pension contributions. |

|

Focus additional pension entitlements on reducing future old age poverty risks, for example, by phasing out subsistence benefit entitlements more slowly as pension entitlements rise. Fund such additional spending from general tax revenue instead of higher payroll taxes. |

From 2018, individual and occupational private pension savings will not be deducted from means-tested minimum pensions, up to a limit. |

|

Strengthen insurance against disability, for example by making it easier to claim legitimate private disability insurance benefits. Consider eliminating the discount from public disability benefits for claiming the benefit before the age of 63 years and ten months. Reconsider the cuts of these benefits as other income rises. |

Legislation in 2017 improved the benefits in case of reduced earnings capacity in the statutory pension insurance. A more flexible combination of partial pension and supplementary earnings also applies for disability benefits. |

|

Remove barriers to the portability of civil servant pensions. |

No action taken. |

|

Enroll all individuals in occupational pensions by default, allowing them to opt out. |

From 2018, social partners can agree enrolment by default in businesses covered by collective bargaining. |

|

Strengthen supervision of direct pension commitments of employers. Make contributions to the risk-pooling scheme dependent on risk indicators. |

No action taken. |

|

Reduce operating costs of subsidised, individual pension plans by improving comparability among providers. |

Since 2017, providers of subsidised individual pension plans are obliged to disclose costs and the implied reduction in the yield in a standardised fashion. |

|

Strengthen experience-rating in employer contributions to work accident and disability insurance. |

No action taken. |

Better prioritising public spending would help boost growth and wellbeing

Spending reviews provide evaluations of spending programmes with the objective to identify savings, improve efficiency by allowing to reallocate spending and create fiscal space (OECD, 2016[20]; 2011[21]). Systematic scrutiny improves prioritisation. Spending reductions, if needed, can be made sustainable (Robinson, 2014[22]). Spending reviews reconsider programme objectives and the impact of the resources devoted to them. The OECD regularly gathers expertise on spending reviews to develop best practice (OECD, 2017[23]; 2017[24]; 2016[25]).

Following the 2014 OECD Budget Review (OECD, 2015[26]), Germany introduced spending reviews in 2015 (Federal Ministry of Finance, 2017[27]). They are performed in inter-ministerial working groups and include external experts. They are coordinated by a steering committee headed by the Ministry of Finance. However, results are only used to prioritise spending within narrowly-defined policy areas, not to shift funds between broad policy fields, as is done in the United Kingdom for example (Federal Ministry of Finance, 2017[27]).

Germany can broaden the scope of spending reviews in various ways (Shaw, 2016[28]; OECD, 2016[25]). The Netherlands applies them comprehensively to wide policy areas (such as transport or health) while Canada and Denmark apply them to all the spending programmes conducted by selected departments. Canada also applies a horizontal approach across departments on selected policy areas (e.g. innovation in the public sector). At an earlier stage Canada reviewed spending ministry-by-ministry to redirect funding (Shaw, 2016[28]). Some countries, such as Ireland and United Kingdom, do comprehensive spending reviews across all government policy areas, covering established programmes as well as new programme proposals (European Commission, 2017[29]), usually at the beginning of a new government.

Spending reviews should draw on systematic ex-ante and ex-post evaluation. Canada for example has introduced a central registry of evaluation results. Ireland conducts evaluations every three years for all major blocks of spending. To be useful for spending reviews, evaluation requires defining clear programme objectives and introducing standards for the analysis of efficiency (Shaw, 2016[28]).

To ensure their systematic use, spending reviews can be integrated in budgeting procedures. In the United Kingdom, for example, comprehensive spending reviews were explicitly linked to the setting of departmental expenditure limits (OECD, 2011[30]). In Chile it is a requirement to incorporate recommendations from broad evaluations in the preparation of the budget. Defining cycles of recurrent spending reviews, such as in Denmark, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, also helps ensure their continued application.

Strengthening spending reviews would foster performance-oriented budgeting, which is less developed in Germany than in many OECD countries, such as Austria (Downes, Moretti and Nicol, 2017[31]), Canada and Ireland (Shaw, 2016[28]). Performance-oriented budgeting improves decision-making and public scrutiny (OECD, 2017[24]), thereby strengthening civic engagement and governance, a key wellbeing dimension (Figure 1 above). It can also improve the evaluation of whole-of-government policies, such as gender equity. Spending reviews could be legally required and to allow the review of priorities across broad policy areas (OECD, 2015[26]). The implementation of recommendations in spending reviews needs to be tracked closely (OECD, 2017[24]). They could also help set priorities within Länder budgets.

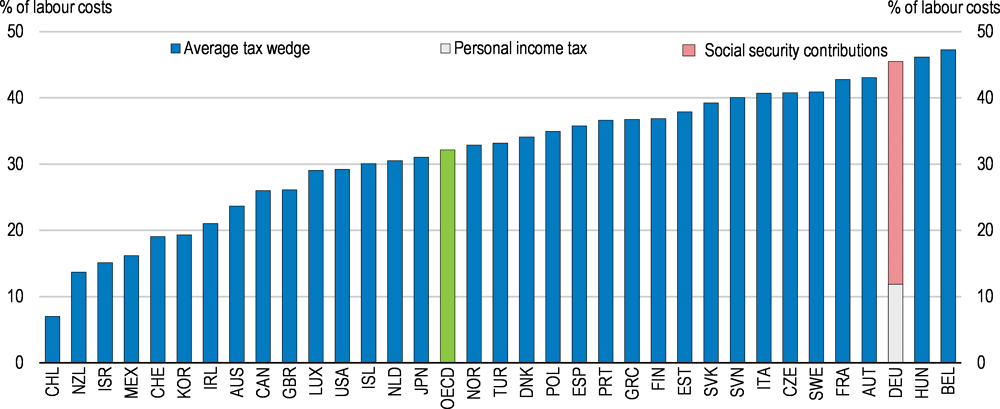

The tax system could be made more growth and equity friendly

The taxation of low labour incomes is high (Figure 21), mostly on account of social security contributions, and has fallen little below the level in 2016. Moreover, the increase in ageing-related spending is expected to entail an increase in ear-marked social security contributions, which fund pension, health and long-term care spending. Steps to reduce this tax burden and prevent future increases should therefore be a priority. It would also help workers maintain employability in the face of technological change (see below). The coalition agreement foresees reducing the unemployment insurance contribution rate by 0.3 percentage points. It also proposes to shift some social security contributions from employees to employers and to lower taxes and social security contributions paid by low-wage earners above the mini-job income threshold of EUR 450. Another option would be to phase out means-tested social assistance more slowly as wage earnings rise.

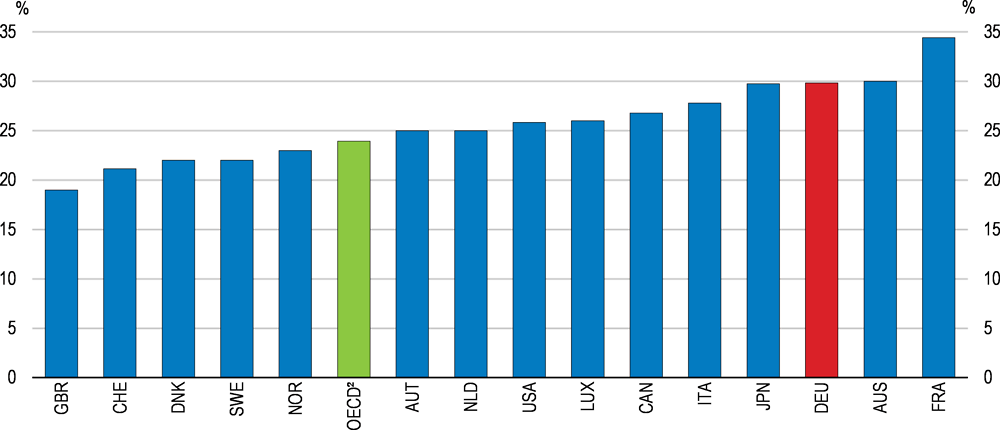

Second earners (often women) in households are taxed particularly highly which discourages full-time employment of women (Figure 22). Lower taxation of second earners would improve incentives to work longer hours and therefore give women better access to good professional carriers and reduce the gender earnings gap. Non-working spouses are ensured in public health insurance free of charge. Relating health insurance premiums to the number of adults in a household and introducing a separate tax-free allowance which can only be deducted from the earnings of the second earner would reduce the tax wedge on second earners. In some OECD countries, spouses’ incomes are assessed fully separately for income taxation. However, this would be inconsistent with the German constitution. Removing barriers to gender balance has a large potential for boosting long-term growth (Box 2).

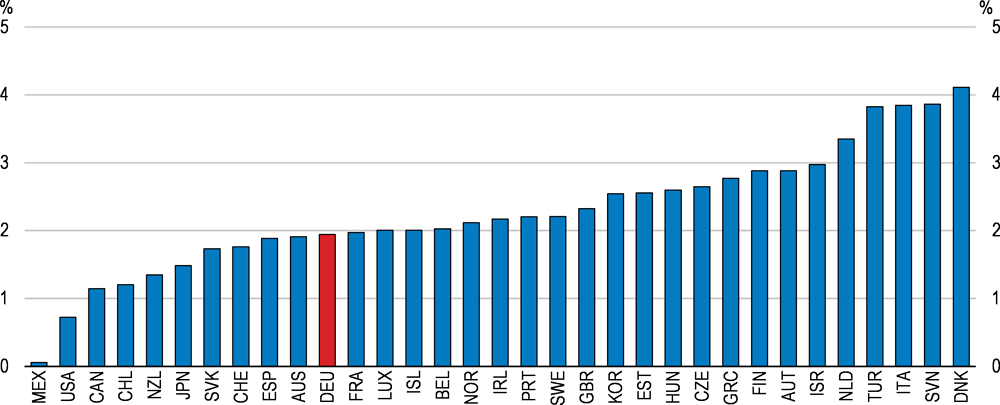

The taxation of corporate profits is higher than in other high-income OECD countries (Figure 23). However business investment has been subdued despite strong corporate profitability in recent years, suggesting that corporate income taxes may not constrain investment much at present. In recent years, several high-income OECD countries reduced corporate income taxes, including Spain, Italy, Norway, Luxemburg, the United Kingdom, Japan and the United States. Recently, France and Australia announced reductions. In the United Kingdom a further reduction is envisaged for 2020. This may put pressure on Germany to reduce its corporate income taxes.

Figure 21. Labour taxes on low incomes are high

Income tax plus employee and employer contributions less cash benefits for single person, no child, 67% of average earnings¹, 2017

1. 67% of the average wage earnings of a full-time worker in the private sector.

Source: OECD (2018), Taxing Wages Statistics (database).

Figure 22. Taxes on second earners are high

Difference in the average tax wedge between two- and one-earner family, 2017

Note: The bars show the difference between the tax wedge of a two- and a one-earner family. The main earner earns the average earnings and the secondary earner earns 67% of the average earnings of a full-time worker in a family of a married couple with two children. The tax wedge is the sum of personal income tax, employee plus employer social security contributions, minus benefits as a percentage of labour costs.

Source: OECD (2018), Taxing Wages Statistics (database).

Figure 23. Corporate taxes are higher than in most high-income OECD countries

Statutory corporate income tax rate¹, 2018

1. Basic combined central government and sub-central government corporate income tax rate.

2. Unweighted average of 35 OECD countries.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Tax Statistics (database).

Fiscal space could be used to reduce the taxation of low earnings further. More room for a reduction of taxes, in particular social security contributions, on wage income could be made by changing the tax mix. Consumption, environmental externalities, real estate and household capital income could be taxed more consistently, eliminating reduced rates and exemptions. Reduced VAT rates could be raised to the standard VAT rate. Shifting the tax system away from labour towards consumption, real estate and environmental taxes is growth-friendly (Johansson et al., 2008[32]). Little progress has been made on tax reform recommendations in previous Economic Surveys (Table 4). In part, this is because revenues from different taxes flow to different government levels. For example, social security contributions fund pensions, public health insurance institutions and unemployment insurance. Real estate taxes accrue to local governments. Broader tax reform would therefore need to be accompanied by reforms to the financial relationships between government levels.

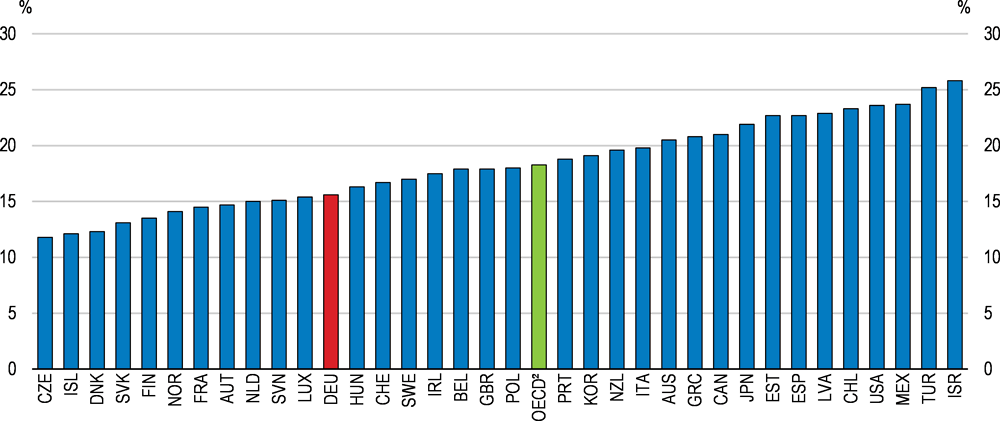

The revenue from environmentally related taxes accounts for 2% of GDP, only about half of what is raised in Denmark according to OECD data (Figure 24). Charges electricity consumers pay to finance subsidised feed-in tariffs for renewable energy are not included in environmental taxes, in Germany and elsewhere. The structure of Germany’s energy taxation sends inconsistent carbon abatement signals across fuels, as argued in previous Economic Surveys. Carbon intensive fuels are often taxed at lower rates per tonne of CO2 compared to low-carbon fuels. For example, diesel is taxed at a lower rate than gasoline on a per litre basis. However, burning diesel emits higher levels of CO2 per litre. Tax rates differ widely across energy users and fuels. Coal use is taxed at lower rates than natural gas use. Certain energy-intensive production processes are partially or fully exempt from energy taxes. In addition, tax expenditures for environmental harmful activities could be gradually phased out, energy tax rates could be aligned with carbon intensity and taxation of nitrogen oxide emissions could be introduced, as recommended in the 2016 Economic Survey.

Reforming the taxation of immovable property would be particularly timely in view of rising house prices. Valuations for the purpose of real estate taxation date back to 1964 (in Western Germany) and 1935 (in Eastern Germany). The constitutional court has recently required a reform to update valuations by 2024. Updating could be used to raise more revenues with relatively little economic distortion. Extending the taxation of capital gains to residential real estate which is not owner-occupied (i.e. owned by households for investment purposes only) would be particularly timely in view of house price developments and would also benefit inclusiveness, as the richest 20% of German households own 75% of the housing stock (Clamor and Henger, 2013[33]). It would also do away with a distortion which biases investment away from more productive investment.

Taxes on household capital income could be better aligned with taxation of other household income. Interest income, dividends and capital gains are taxed at a flat rate, which is in most cases lower than the personal income tax rate. Aligning tax rates on household capital income more closely with personal income tax rates would strengthen the tax system’s progressivity, as capital income is concentrated among wealthy households. It is welcome that the coalition agreement proposes to do so for interest income. In view of the international mobility of capital, which disconnects domestic saving from domestic investment decisions, taxing households’ capital income in line with the taxation of other household income need not hamper investment. Inheritance tax exemptions with respect to family firms lock in capital in these firms, harming reallocation and inclusiveness in view of the strong concentration of wealth. Steps to give more time for family-owned businesses to pay inheritance tax liabilities and to treat the inheritance tax liability as subordinate debt in the balance sheet can help avoid unwanted liquidations.

Figure 24. Environmental tax revenue could be higher

Environmental tax revenue as % of GDP, 2014

Source: OECD (2018), "OECD Instruments used for environmental policy", OECD Environment Statistics (database).

Table 4. Past recommendations and actions taken on tax reform

|

Recommendations |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Reduce social security contributions, notably for low income workers. |

Public pension contributions were lowered by 0.1 percentage points in 2018. |

|

Update real estate tax valuations while protecting low income households. |

No action taken. |

|

Extend capital gains taxes on residential real estate except for owner-occupied housing. |

No action taken. |

|

Raise the tax rates applying to household capital income towards marginal income tax rates applying to other household income. |

No action taken. |

A policy package which includes the budgetary and tax policies in Table 5 and key growth-enhancing structural reforms (Box 2) would imply structural government deficits in the medium term, which would still be consistent with budgetary rules. Nevertheless they would allow the debt-to-GDP ratio to fall substantially (Figure 25). The baseline and reform scenario assume that commitments to budget rules are kept and that higher ageing-related spending is offset by increased revenues or lower spending.

Table 5. OECD reform proposals on budgetary and tax policy

|

|

Budgetary impact (annually, % of GDP) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Estimated impact on government financial balance |

Short-term |

Long-term |

|

Increase spending on primary education per pupil to the level of Denmark or Sweden, in purchasing power terms of GDP |

-0.1%1 |

- 0.1% |

|

Increase government spending on early childhood education and childcare to the level of Sweden or Denmark, while reducing family tax breaks. |

-0.2%2 |

-0.2% |

|

Reduce taxation of wage earnings, while strengthening the taxation of environmental taxation, real estate taxes, the taxation of capital income received by households and raising reduced VAT tax rates to the standard rate |

- 0.1% |

-0.1% |

|

Index the statutory retirement age to life expectancy |

0 |

+0.6%3 |

Note: The short-term budgetary impact is 0.4% of GDP, equal to the OECD estimate of near-term budgetary space. The spending increases are constant shares of GDP.

1. Increase in government spending in Germany towards the level of spending per pupil observed in Denmark.

2. Raising government spending on childcare and early childhood education towards the level observed in Denmark and Sweden (% of GDP), while assuming that tax breaks for families with children in Germany are abolished and savings used to pay for childcare and childhood education.

3. Estimates by (European Commission, 2015[34]).

Figure 25. Policies which raise inclusive growth can be deficit financed in the short and medium term

Difference in government debt (% of GDP) between reform scenario and baseline scenario

Note: The baseline scenario assumes real GDP growth of 1% and an inflation rate of 1.5% after 2019. The primary balance is assumed to remain constant at its 2019 level (0.65% of GDP). The reform scenario assumes real GDP growth of 1.6%, which includes the annual average impact of structural reforms quantified in Box 2, as well as the budgetary measures in Table 5. The interest rate on government debt is assumed to converge to 1.8%.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Boosting productivity and preparing for the future of work are key medium-term challenges

As other OECD countries, Germany faces the challenge of making the most of technological changes, including through appropriate skills policies. This needs to include policies to remove barriers for women to good careers and to make better use of their skills. The GDP gain from structural reforms in these policy areas would be particularly large (Box 2).

Box 2. Simulations of the potential impact of structural reforms

This table gauges the potential impact of some of the key structural reforms proposed in this Economic Survey, based on OECD studies on relationships between reforms and growth and other studies. The simulation results are based on cross-country estimates that do not reflect the unique institutional settings in Germany. These estimates should be seen as purely illustrative.

Table 6. Potential impact of structural reforms on GDP per capita

|

Structural policy reform |

Change in GDP per capita |

Scenario |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

After 10 years |

Long run |

|

|

Product market regulation |

|||

|

(1) Upgrading e-government |

0.13% |

0.25% |

Creation of an online single contact point, where all notifications and licenses be issued or accepted via the Internet. |

|

(2) Reducing entry barriers to professional services |

2% |

2% |

Making regulations as competition-friendly as in the United Kingdom. |

|

Infrastructure investment |

|||

|

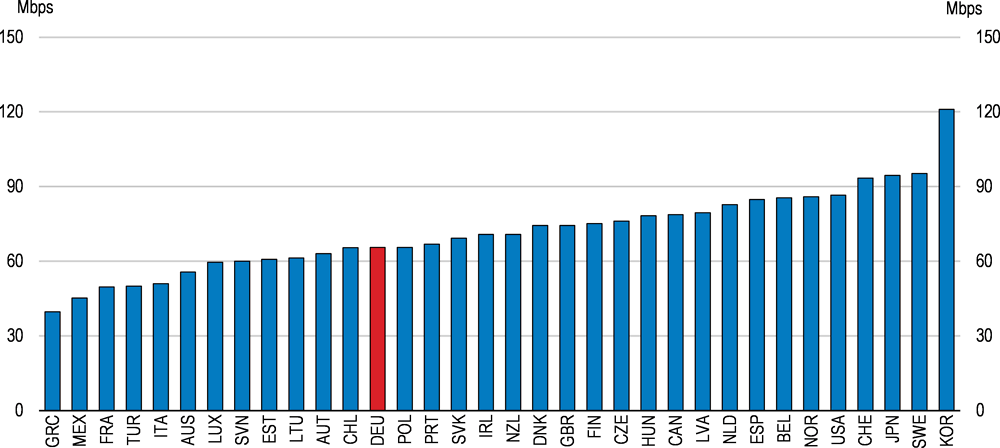

(3) Investment in high speed broadband |

3% |

3% |

Germany’s average connection speeds (15.3Mbts/s) catches up to the average of ten best performing OECD countries (21Mbts/s) (37% increase in connection speed) by 2025 |

|

Skills |

|||

|

(4) Boosting cognitive skills, including by improving the quality of childcare, expanding high-quality full-day primary education, improving general education within vocational education, strengthening life-long learning. |

- |

15% (75 years) |

Cognitive skills as measured by PISA or PIAAC move from an upper-middle to a top position among OECD countries. The improvement of cognitive skills takes place over a 20-year period. |

|

Labour market policies |

|||

|

(5) Remove barriers to women’s full-time employment and access to good careers, including by reducing the gap in the taxation of main and second earners, improving full-day childcare and primary education, improving gender balance in parental leave and encouraging firms to increase women’s presence in the highest decision making bodies. |

4.1% |

20% (45 years) |

Women’s labour participation rate and hours worked are assumed to converge to men’s. Women’s productivity per worker is assumed to converge to men, to the extent the earnings gap with respect to men’s earnings reflects differences in experience and hours worked. As women’s labour supply decisions and earnings depend on their experience, convergence is assumed to be gradual. Men’s participation rate, hours worked and earnings are assumed not to diminish in response, so the estimates are an upper bound. |

|

(6) Reduce taxation of labour income |

0.45% |

0.47% |

2.28 percentage point reduction in average tax wedge (the average size of reform observed across OECD countries), while increasing indirect taxes to keep tax revenue constant. |

|

(7) Indexation of the retirement age to life expectancy |

0.13% |

0.14% |

Proxied by the rise in statutory retirement age of 0.57 years (the average size of reform observed across OECD countries). |

|

Total |

10% |

41% |

|

|

Welfare gain (monetary equivalent, % of GDP) |

|||

|

(8) Introducing pricing of congestion and removal of regulatory hurdles to car-sharing. Electrification of car transport. |

6.76% |

Welfare gains from reforming urban transport, including reduction of congestion cost to zero. Reduction of pollution-related mortality and morbidity costs to zero. |

|

Note: Reforms are quantified using the framework of (Égert and Gal, 2017[35]) (1, 6, 7); (Arentz et al., 2016[36]) (2); (Kongaut and Bohlin, 2014[37]) (3); (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2008[38]) (4); (OECD, 2016[9]) (5); (INRIX, 2016[39]) (INRIX, 2017[40]) (8). Investment in high speed broadband is included in the coalition agreement.

Source: OECD calculations.

Productivity growth has slowed and new technology is adopted only slowly

Germany enjoys high labour productivity (Figure 26). However, it is held back by weak capital deepening and slower diffusion of new technology (Chapter 1). Technology diffusion can be accelerated by reinvigorating entrepreneurship and strengthening high-speed digital infrastructure.

Figure 26. Labour productivity is relatively high

Real GDP in constant USD PPP per total hours worked, 2016

Boosting entrepreneurship would accelerate technology diffusion