This chapter reviews policies to strengthen Germany’s productivity growth and prepare for changes in labour markets brought about by new technologies. The chapter also discusses how social protection and the bargaining framework should be reformed for the future of work. Germany enjoys a relatively high labour productivity level but productivity growth has been modest in recent years. There is room to boost productivity growth by accelerating the diffusion of new technologies throughout the economy. Vigorous entrepreneurship and innovation by small and medium enterprises are key for such technology diffusion while strong broadband and mobile networks widen the scope of data-intensive technologies that can be exploited to increase productivity. Widespread use of new technologies will bring about significant changes in skill demand and work arrangements. As in many countries, Germany saw a decline in the share of middle-skilled jobs in employment. A relatively high share of jobs is expected to be automated or undergo significant changes in task contents as a result of technological change. New technologies are also likely to increase individuals engaging in new forms of work, such as gig work intermediated by digital platforms. Such workers are less covered by public social safety nets such as unemployment insurance than regular employment.

OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2018

Chapter 1. Boosting productivity and preparing for the future of work

Abstract

Productivity growth is held back by slow adoption of new technologies

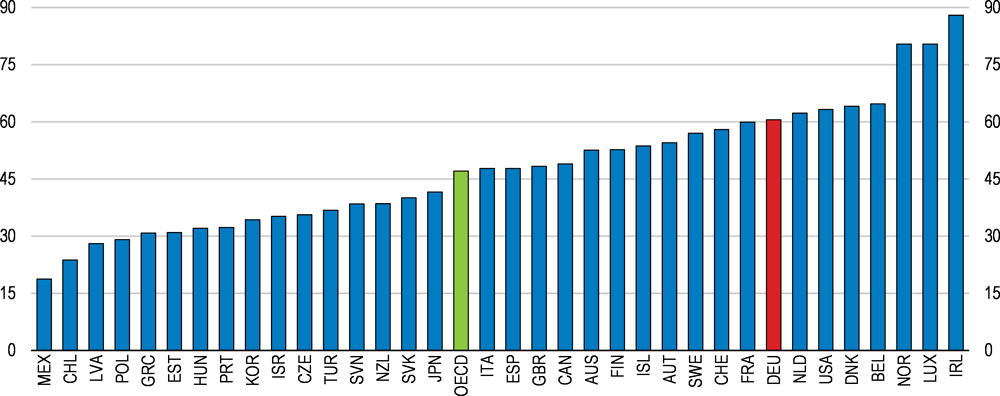

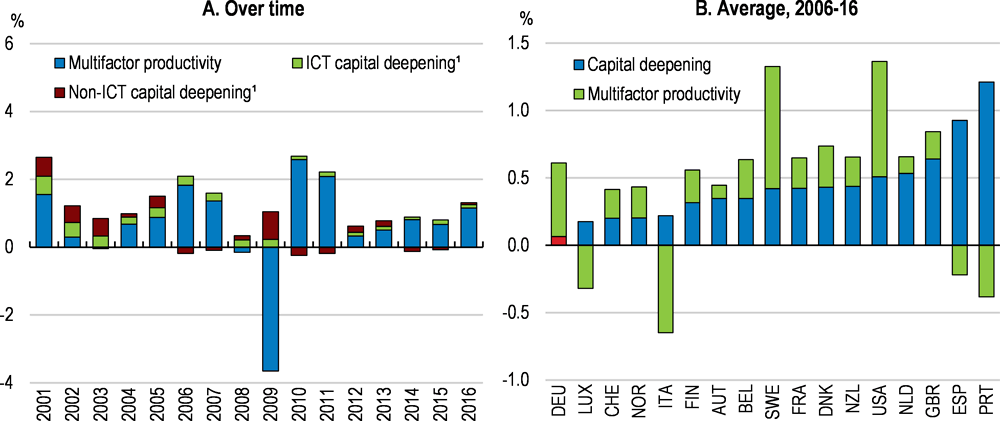

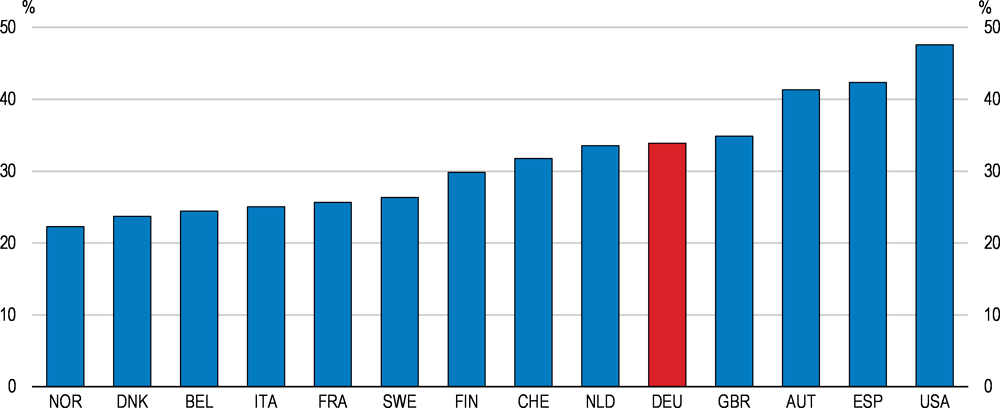

Germany enjoys relatively high labour productivity among OECD countries (Figure 1.1). However, labour productivity growth in recent years was subdued compared to the pre-crisis period, as in many other OECD countries,(Figure 1.2 Panel A) (OECD, 2016[90]). The contribution of capital per worker to labour productivity growth was very small, due to weak business investment (Figure 1.2 Panel B). Multifactor productivity (MFP) growth improved significantly during the swift economic recovery after the crisis, but it has slowed down since.

Figure 1.1. Labour productivity is relatively high

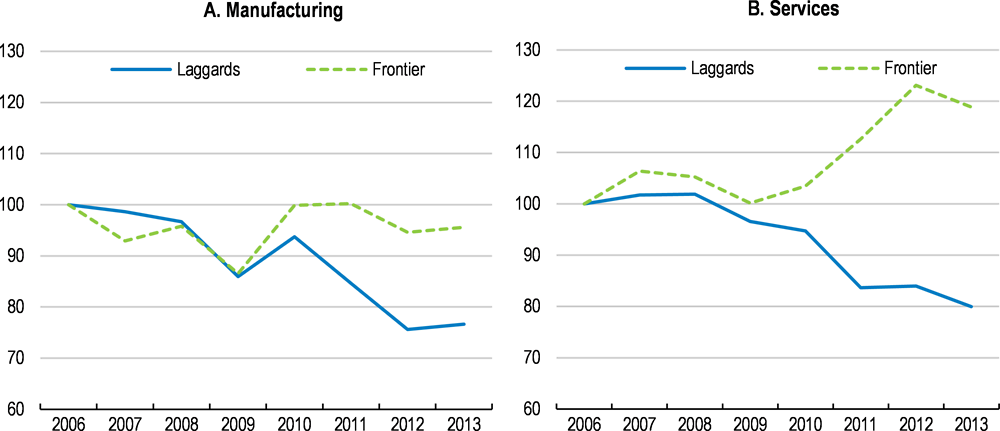

Real GDP in constant USD PPP per total hours worked, 2016

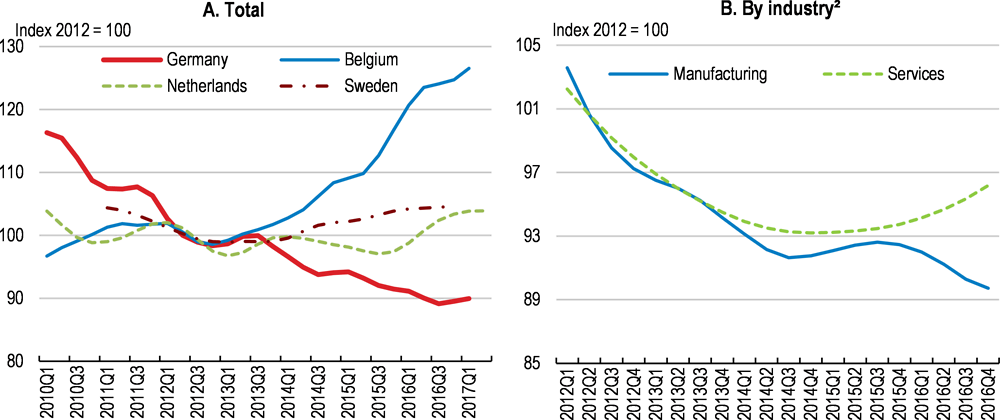

Slower MFP growth reflects several factors. For instance, Germany’s strong employment performance, particularly employment gains among low skilled workers, may have weighed on productivity growth (Boulhol and Turner, 2009[91]). Rising skill shortages are also likely to be holding back more productive firms from growing in size (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2015[92]). A recent OECD study emphasizes the role of increasing divergence in productivity between firms at the productivity frontier and the rest (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[93]). Indeed, the average MFP level of the most productive German firms (considered as firms at the productivity frontier) and that of other German firms diverged after the crisis, especially in the service sector (Figure 1.3). The divergence points to a slower diffusion of new technologies and knowledge from frontier firms to the rest of firms in the economy. It also implies substantial room to boost productivity growth by increasing the adoption of new technologies like digital technologies among lagging firms.

Figure 1.2. Labour productivity growth has been subdued

Contribution of capital deepening and multifactor productivity to labour productivity growth

Note: ICT (Non-ICT) capital deepening refers to the annual rate of change in ICT (Non-ICT) capital intensity that is defined as the ratio of ICT (non-ICT) capital services per hour worked.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Productivity Statistics (database) and OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Figure 1.3. The productivity gap between frontier firms and the rest has widened

Multifactor productivity level, indexed as 2006=100

Note: The charts show the evolution of multifactor productivity of the top 5% of German firms with highest productivity within each 2-digit sector (frontier firms) and the rest of firms (laggards). The productivity levels are normalised to 2006 = 100, and the indices are approximated by changes in log-productivity.

Source: Estimation by the OECD secretariat based on ORBIS dataset.

Faster technology diffusion can boost productivity in the service sector and among SMEs

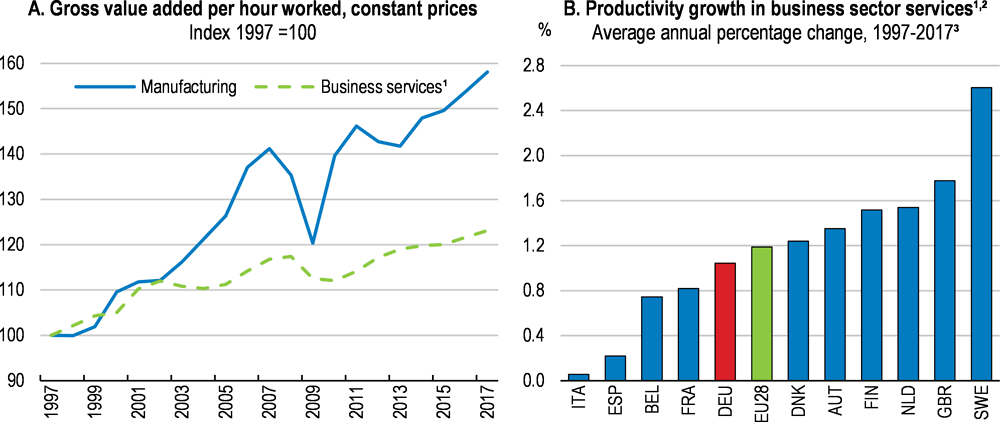

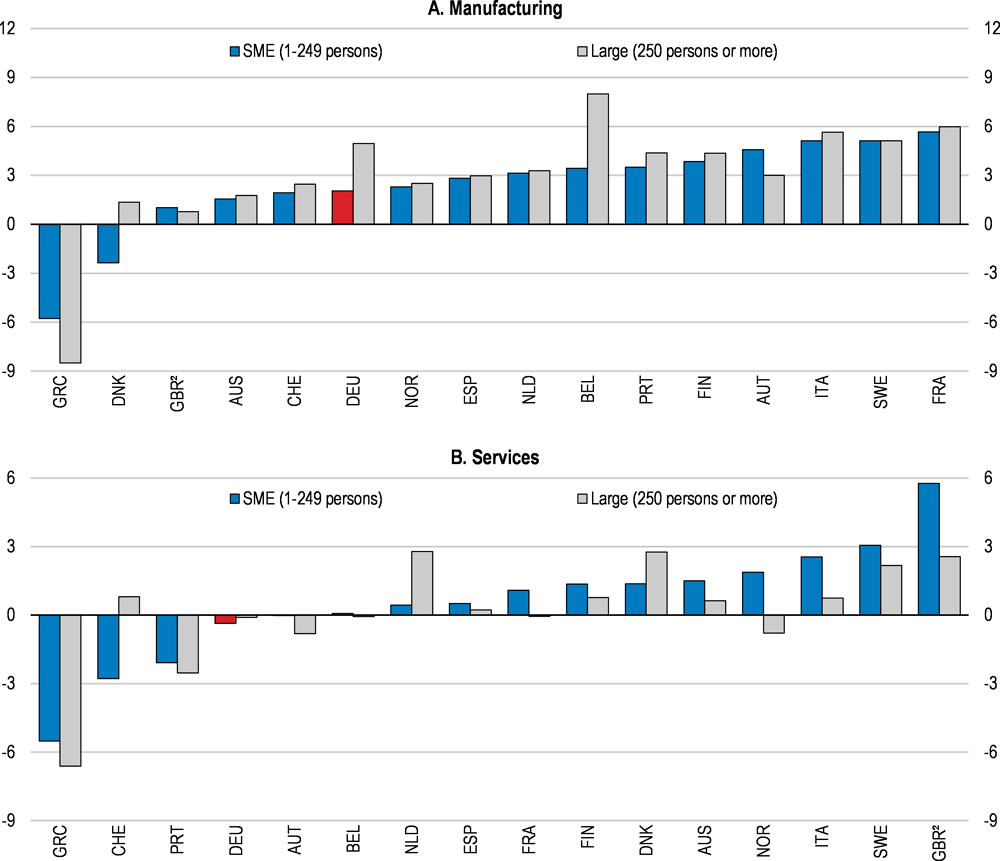

Labour productivity growth has been slower in the service sector compared to the manufacturing sector (Figure 1.4, Panel A) or to the service sector in several other advanced European economies (Figure 1.4, Panel B).

Figure 1.4. Productivity growth in the service sector is low

1. Excludes real estate.

2. Labour productivity growth is defined as the annual change in gross value added (in volume terms) per hour worked.

3. 1999-2016 for Belgium.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Productivity Statistics (database).

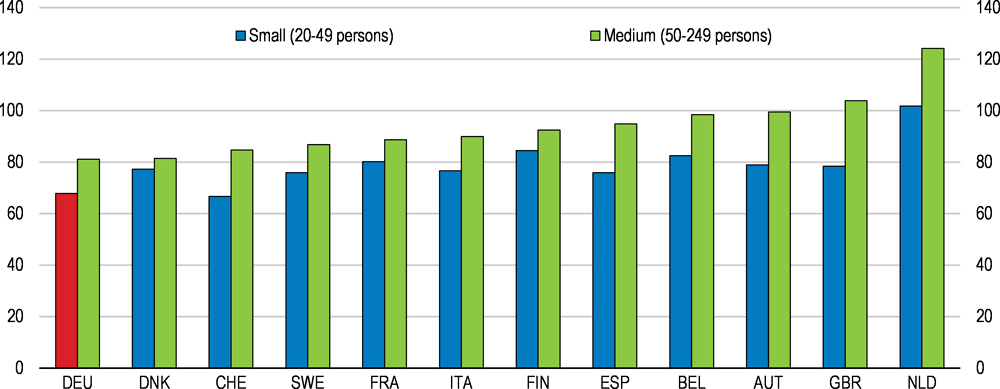

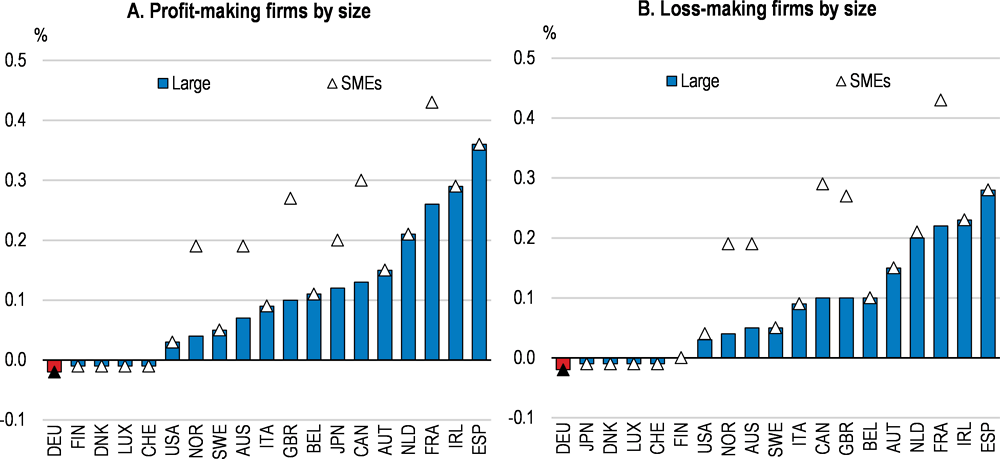

Within the manufacturing sector, labour productivity growth has been significantly slower among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) compared to large enterprises Figure 1.5, Panel A). In contrast, productivity growth has been weak for both SMEs and large enterprises in the service sector (Figure 1.5, Panel B). Furthermore, in both manufacturing and service sectors, German SMEs’ productivity growth underperformed SMEs in several other advanced economies markedly. This has contributed to a productivity gap between SMEs and large firms that is larger than many other advanced European economies (Figure 1.6). The gap is particularly pronounced in the manufacturing sector where medium-sized firms are only 65% as productive as larger firms (OECD, 2017[94]). These observations indicate that there are large untapped productivity gains from enhancing diffusion of new technologies among firms in the service sector and among SMEs. Boosting productivity growth of SMEs in the service sector would improve the overall productivity performance of the sector, given that about two-thirds of workers in this sector are employed by SMEs (OECD, 2017[94]).

Figure 1.5. Labour productivity growth of small and medium sized enterprises is low

Real value added per person employed, average annual growth rate, 2009-2014 or latest year¹

1. Average annual growth rate over 2010-14 for Switzerland, 2009-13 for France and 2009-12 for Finland and Portugal.

2. The charts exclude small unregistered businesses; these are businesses below the thresholds of the value-added tax regime and/or the pay as you earn (PAYE) regime.

Source: OECD (2017), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017.

Figure 1.6. The productivity gap between large firms and SMEs is large

Value added per person employed for SMEs, percentage of the level of large firms, 2014, or latest year

Note: Large firms are firms with more than 250 employed persons.

Source: OECD (2017), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017.

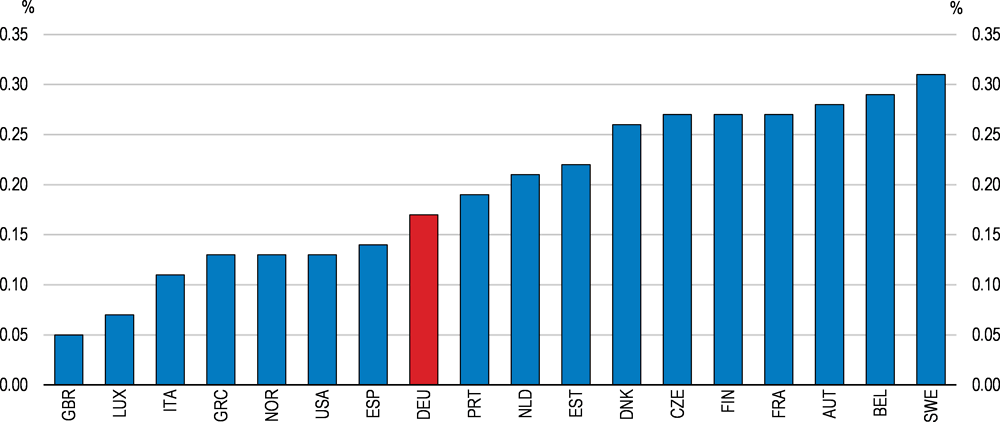

Knowledge-based capital contributes little to productivity growth in Germany

Knowledge-based capital (KBC) increasingly determines productivity growth, because it plays a central role in the diffusion of new technologies through commercialisation, learning and complementary organisational change required for new technologies to yield productivity gains (OECD, 2013[95]). Germany’s investment in KBC is concentrated in the manufacturing sector, and is predominantly R&D and organisational capital (Belitz, Le Mouel and Schiersch, 2018[96]). Investment in the service sector is low when compared to the manufacturing sector, or to the service sector of other countries. The low investment intensity in the service sector results in low overall investment in KBC compared to other advanced OECD countries (OECD, 2016[9]), and a smaller contribution of KBC to labour productivity growth (Figure 1.7).

A recent study (Belitz et al., 2017[97]) has shown that investment in KBC contributes to higher productivity of German firms, but that it is concentrated among large firms in the manufacturing sector and in a few service sectors such as ICT services or telecommunication. SMEs invest a significantly lower share of their value added in KBC than large enterprises, although the marginal gains in productivity from a unit of investment in KBC are similar in large firms and SMEs (Belitz et al., 2017[97]). This implies that stronger KBC investment by SMEs can contribute to closing the large productivity gap with large firms. Investment in software and organisational capital, two types of KBC that are often complementary in reaping the benefits of digitalisation (Brynjolfsson, Hitt and Yang, 2002[98]) are particularly associated with large productivity gains (Belitz et al., 2017[97]).

Figure 1.7. The role of knowledge-based capital in productivity growth is small

Contribution of KBC to labour productivity growth, business sector, 2000-14

Note: Contributions are calculated using a standard non-parametric growth accounting method for market sectors (i.e. ISIC Rev.4 Divisions 01 to 82 excluding 68, and 90 to 96) for the overall period, assuming constant returns to scale and full competitive markets, where production technology takes a log linear form and output elasticities are equal to factor shares. KBC capital includes software, R&D and organisational capital.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2017: The digital transformation.

Investment in some KBC involves large upfront costs and considerable uncertainties on its return. The intangible nature of KBC makes it less suitable as collateral, which limits the possibility of small younger firms debt financing the investment in KBC (OECD, 2013[95]). Also, due to its non-rival nature, KBC is associated with strong economies of scale. The return to KBC investment depends crucially on how fast innovative firms that deploy novel KBC can expand their market shares and grow in size. An efficient resource allocation that allows innovative firms to attract sufficient capital and personnel is thus essential for promoting stronger KBC investment among smaller firms (OECD, 2016[9]).

Vigorous entrepreneurship accelerates technology diffusion

Entrepreneurship is an important driver of technology diffusion. Young firms often introduce new technologies into markets (OECD, 2015[99]). They also engage more in high-risk break-through innovation (Färnstrand Damsgaard et al., 2017[100]). ICT start-ups introduce new digital services. In this way they open new pathways for entrepreneurial activities, by increasing availability of affordable digital tools and access to market demand through digital platforms (OECD, 2017[101]). Entrepreneurship that effectively deploys new technologies and business models is particularly important in boosting the productivity in the service sector and among SMEs.

New enterprise creation in Germany has been declining since the financial crisis (Figure 1.8, Panel A), although it has been recovering in the service sector after 2015 (Figure 1.8, Panel B). Firm creation has been declining in all regions except in Berlin.

Figure 1.8. New enterprise creation is weak

Number of new enterprises, by industry, trend-cycle¹

1. The trend-cycle component is extracted from quarterly data by applying seasonal adjustment to quarterly series. Refer to the source for more details.

2. Manufacturing refers to ISIC Rev.4 Divisions 10 to 33. Services refer to Divisions 45 to 82 excluding 64 to 66.

Source: OECD (2017), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017.

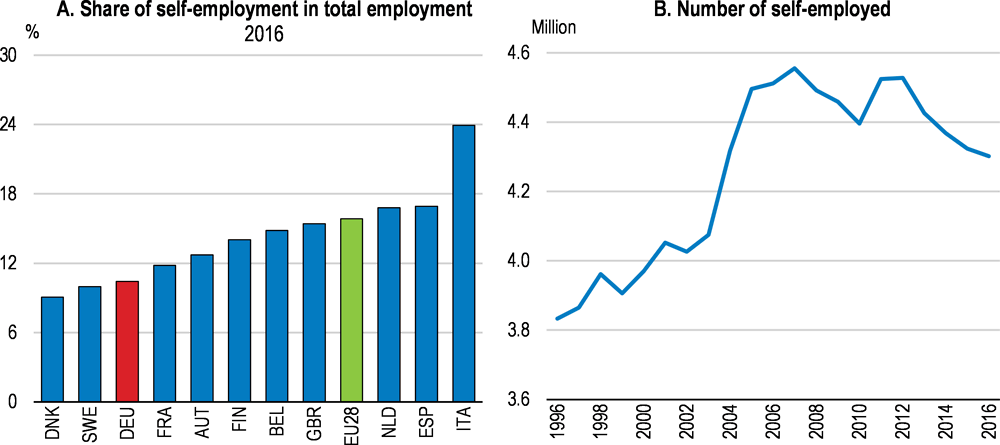

Self-employment in Germany is around 10% of total employment, lower than in many other advanced European countries (Figure 1.9, Panel A). The number of self-employed increased rapidly after 2002 as labour market reforms that tightened access to unemployment benefits and unfavourable labour market conditions encouraged the unemployed to start their own business (Figure 1.9, Panel B). It has been decreasing since 2012, as improved labour market conditions reduced such necessity-driven start-ups (KfW, 2017[102]).

Figure 1.9. The share of self-employment is relatively low

Source: OECD (2018), "Labour Force Statistics: Summary tables", OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database).

Current entrepreneurship in Germany is primarily driven by start-ups motivated by business opportunities (KfW, 2017[102]), which tend to bring more innovation to the market, employ more staff and survive longer. Yet, the number of such opportunity-based start-ups has been declining as well, as potential entrepreneurs are less willing to choose self-employment that is associated with significantly lower income security than employment (KfW, 2017[102]). Indeed, financial risk is the top reason cited by the individuals that seriously considered starting their own business but abandoned their plan to do so (Metzger, 2015[103]). As discussed below, the relatively high costs of failure and lower coverage of the self-employed with social protection are likely to constitute an effective barrier to entrepreneurship.

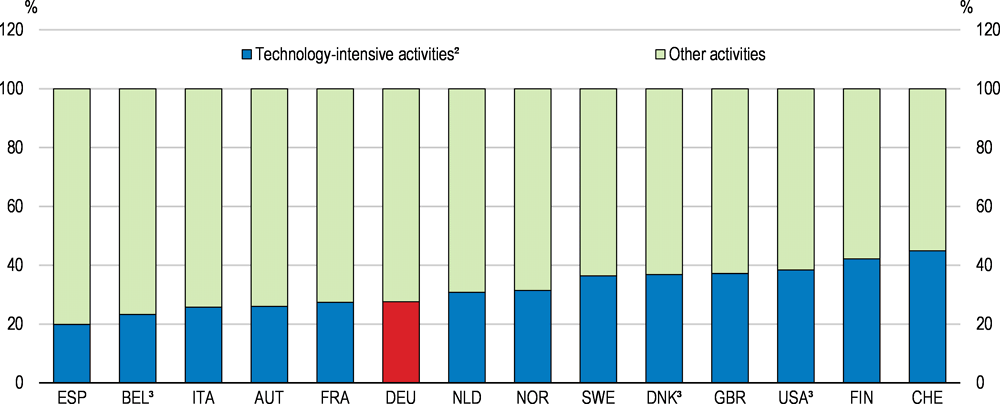

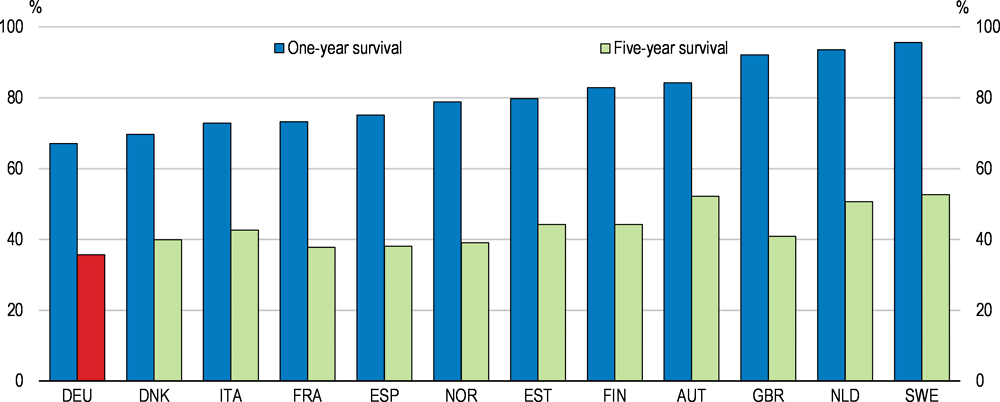

Entrepreneurship in Germany is biased towards low-tech sectors. There are few start-ups in knowledge intensive service sectors. The share of jobs created by new firms in technology-intensive sectors is low compared to several other advanced economies Figure 1.10). In 2016, only 9% of entrepreneurs conducted research and development (R&D) in order to turn technological innovations into new products and services (KfW, 2017[102]). Furthermore, businesses operated by the self-employed have a smaller chance to survive in Germany than in several other advanced European economies (Figure 1.11) in spite of favourable economic conditions. This may also be related to the higher chance of finding good employment opportunities in Germany.

Figure 1.10. Entrepreneurship is concentrated in less technology-intensive activities

Share of sectors in total employment created by employer enterprises birth¹, 2014 or latest year

1. An employer enterprise birth refers is the birth of an enterprise with at least one employee.

2. Technology-intensive activities refer to industry, information, communication, financial intermediation, real estate, and professional scientific and technical activities.

3. 2013 for Belgium and Denmark. 2012 for the USA.

Source: OECD (2017), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017.

Figure 1.11. The survival rate of the self-employed business is low

Source: OECD/EU (2017), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2017: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship.

Promoting women’s entrepreneurship

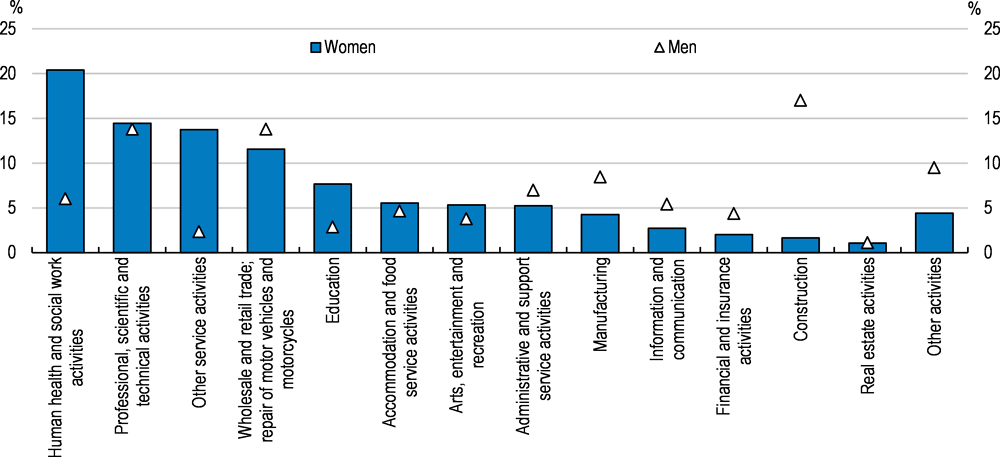

The role of women in entrepreneurship in Germany is small, especially in sectors where technology diffusion is strong. Only 8% of all active female workers are self-employed, less than in the average of European Union countries (13%), although this share has been rising (OECD, 2017[104]). About 90% of self-employed women work in the service sector, mostly in personal and business services and rarely in technology intensive services such as information and communication (Figure 1.12). Only 13% of high tech start-ups are led by women (OECD, 2017[104]). Female entrepreneurship is also motivated more by necessity than by business opportunities and about two-thirds of self-employed women are “solo” self-employed (OECD, 2017[104]), who include employee-like workers (see below). Across several OECD countries including Germany, start-ups founded by one or more women are less likely to receive financing from venture capital than other start-ups and a smaller amount of finance if they receive any (Breschi, Lassébie and Menon, 2018[105]). More vigorous entrepreneurship by women, especially in high technology sector, can enhance technology diffusion.

The commercialisation of new technologies and the introduction of new business models applying new technologies require advanced entrepreneurial skills. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), one-third of surveyed women in Germany reported that they have knowledge and skills to start up a business (Figure 1.13). However, this share is lower than among men, as in all countries (OECD/EU, 2017[106]). The existing entrepreneurship education in Germany, mostly offered in upper-secondary vocational training and in tertiary education, promotes a classic model of entrepreneurship (i.e. full-time self-employment), that is often not conducive for women (OECD, 2017[104]). For instance, many entrepreneurial women run their start-ups part-time, most likely due to family obligations (KfW, 2017[102]). The entrepreneurial education should advocate diverse forms of entrepreneurship (OECD, 2017[104]). The National Agency for Women Start-up Activities and Services (Bundesweite Gründerinnenagentur) provides adult education targeted to encourage female entrepreneurship.

Figure 1.12. Women’s self-employment is concentrated in less technology intensive services

The sectoral share of self-employment, 2016

Note: The share of each sector in the self-employment of 16 to 64 years old women and men.

Source: Eurostat (2018), Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) Statistics.

Figure 1.13. About one-third of German women have entrepreneurial skills

The share of surveyed women with knowledge to start up a business¹, 18-64 year-olds, 2012-16

Note: Share of surveyed 18-64 years-old women who responded “yes” to the question “Do you have the knowledge and skills to start a business?” The difference between men is the difference between surveyed men who responded “yes” to the question.

Source: OECD/EU (2017), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2017: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship.

Although self-employment may allow women to choose flexible working hours and thus balance work and family obligations, self-employed women across OECD countries actually work longer hours than women employees (OECD/EU, 2017[106]). In Germany, they work on average 14% longer hours than women employees. While the longer working hours are motivated by diverse reasons, it is likely to be partly due to the relatively low net income from self-employment compared to employment (OECD/EU, 2017[106]). In Germany, the annual net median income of self-employed women was 10% lower than that of employed women in 2015.

Women’s full-time entrepreneurship is likely to be held back by the same factors discouraging women’s full-time employment, notably the high tax burden on second earners as well as insufficient supply of full-day childcare and full-day schooling. Women’s entrepreneurship could be encouraged by making entrepreneurship more compatible with giving birth. Maternity benefit coverage depends on the women’s choice of health insurance package. Self-employed women on maternity leave receive a benefit of about 70% of their previous income if they are covered by statutory insurance and have opted for sickness benefits. Alternatively, if they have purchased private health insurance with an option for a daily sickness allowance, they may receive a sickness allowance during the maternity protection period if they do not work or if they work only a limited time. In both cases, self-employed women with full maternity benefit coverage pay higher insurance contributions than self-employed workers without full coverage. Hence, the economic costs of childbirth are not spread across society, which raises the burden to women who consider going into maternity. By contrast, in the Netherlands, all self-employed women can receive a maximum of 100% of the minimum wages for 16 weeks, paid from general tax revenue (Conen, Schippers and Schulze Buschoff, 2016[107]). Ensuring adequate maternity benefits also for self-employed women would make entrepreneurship more compatible with giving birth.

Promoting role models encourages women’s entrepreneurship and breaks gender stereotypes (OECD, 2017[104]). It can also encourage female students to pursue studies in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields, where women are under-represented (Kugler et al., 2017[108]). The Federal Ministry of Economy and Energy (BMWi) has launched an initiative (FRAUEN unternehmen) that advocates successful examples of female entrepreneurship. This initiative can be stepped up by advocating examples of successful female entrepreneurs in technology intensive sectors and cases of successful business models that effectively adopted new technologies in personal and professional services.

Increased presence of women in companies’ management boards is effective in enlarging the pool of experienced female managers who are role models to potential entrepreneurs (Schmitt, 2015[109]). Following the introduction of legislation requiring publicly traded companies to have at least 30% female board members, the share of women on the supervisory board of those companies rose to 32%. However, the share of women on the boards of the largest listed firms is still lower than in Nordic countries and France (Holst and Wrohlich, 2018[110]). The government should encourage more firms to increase women’s presence in the highest decision-making bodies. A higher share of women on boards is associated with better corporate performance in some cases (Post and Byron, 2015[111]) and with stronger corporate social responsibility (Bear, Rahman and Post, 2010[112]).

Reducing further the administrative burdens on entrepreneurship

The administrative burdens on entrepreneurship are still considerable. Setting up a company in Germany takes more procedural steps and more time than in other advanced OECD economies (The World Bank, 2018[113]). There is scope to reduce the complexity of administrative procedures, for instance, by applying more generally the “silence is consent” rule, whereby licences are automatically issued if the competent authority does not act within the statutory period (OECD, 2016[9]).

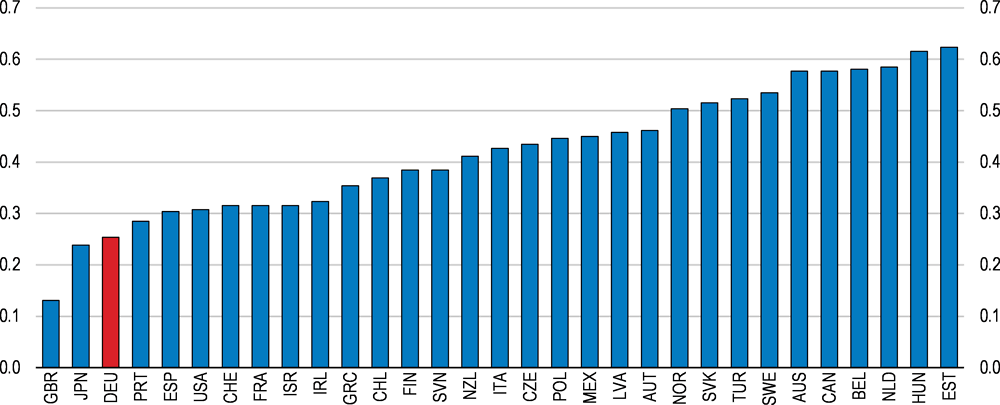

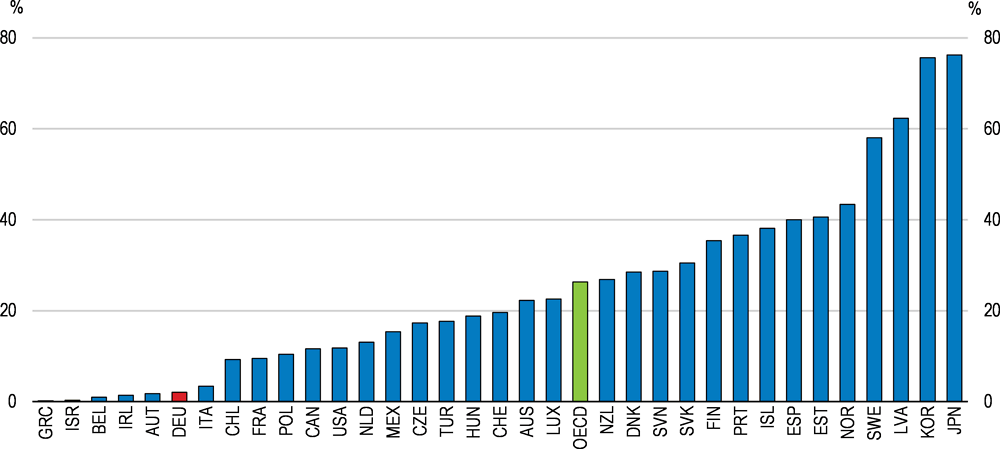

Administrative burdens can also be reduced by a well-developed e-government service that allows all procedures needed for starting up a company to be processed online. The government currently provides few online application forms and issuance of licences and certificates. Few individuals submit forms online (Figure 1.14). Furthermore, the scope of available services differs across municipalities and information is scarce (Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation, 2017[114]). Data exchange among authorities or between authorities and citizens is low, requiring firms and individuals to submit similar information to several authorities.

Figure 1.14. The use of e-government services is low

The share of individuals submitting forms to authorities online, 2016 or latest year

Note: Data refer to using the Internet for sending filled forms in the last 12 months. For country exceptions, see footnotes for Figure 4.15 in the publication, OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017.

Steps were taken to establish nationwide uniform online services while expanding the scope of services. Important legislation in late 2016 laid the framework for such upgrading of e-government service. For instance, the Online Access Improvement Act stipulated that the central and local governments must offer their administrative services online within five years and make them accessible via centralised administrative portals at the national or Länder level. Furthermore, the central government was given a mandate to design access to the administrative services of the Federal, Länder and municipal authorities. This legislation should be implemented swiftly. Upgraded e-government services should particularly enhance data exchange among authorities or between authorities and citizens.

Nationwide upgrading of e-government will raise demand for ICT solutions. For instance, digitalisation of some of the most essential administrative services would require an investment of around EUR 1.7 billion (Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation, 2016[115]). Public expenditure on e-government can be used to stimulate entrepreneurship, by reserving part of the public tender to ICT start-ups. An extensive use of e-procurement, which Germany employs little (OECD, 2016[9]), encourages firms to adopt digital technologies and facilitate the participation of ICT start-ups in the public tender process.

Digitalisation of public services generates large administrative data. These data are valuable for researchers and entrepreneurs who can introduce new knowledge and products. However, the central government data portal (GovData) launched in 2015 is incomplete as it was left to each jurisdiction to decide on which administrative data should be made available on the portal. Some Länder are not participating. The data portal needs to be upgraded both in quality and scope. A law implementing open data principles in the federal administration entered into force in July 2017. Some Länder are also drafting their own laws for open data. In order to ensure uniform access to public data, the government should establish common criteria for administrative data that must be made available. In South Korea, the front runner in online accessibility to government data, the government mandates ministries and municipalities to make all data that match such criteria available in a centralised government portal (OECD, 2017[116]).

Making the insolvency regime less penalising to failed entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurship that leverages new technologies involves high risk of failure and a trial and error process. An efficient insolvency regime allows entrepreneurs to exit unsuccessful business in a timely fashion and start a new venture (Calvino, Criscuolo and Menon, 2016[117]). In particular, insolvency regimes which avoid harsh penalties for bankrupt entrepreneurs reduce the risk of entrepreneurship and are associated with higher rate of firms creation (Lee et al., 2011[118]). While an insolvency regime that is lenient to debtors may hold back lending, international evidence suggests that entrepreneur-friendly reforms in insolvency regime overall increase entrepreneurship (Fossen and König, 2015[119]). For instance, the reform of German personal bankruptcy law in 1999, which introduced debt relief measures, promoted entrepreneurship (Fossen, 2014[120]).

As a result of substantial reforms to facilitate restructuring, Germany’s insolvency regime is among the most efficient in OECD countries (Figure 1.15). However, bankrupt entrepreneurs must wait up to 6 years until they are discharged from pre-bankruptcy indebtedness, resulting in high personal costs for failed entrepreneurs compared to many other OECD countries. The discharge period is on average 2.9 year among OECD countries (Adalet McGowan, Andrews and Millot, 2017[121]). The reform in 2014 allowed the discharge period to be reduced to 3 years, if the bankrupt entrepreneur repays 35% of debt. However, the repayment condition can be too demanding in some cases and could then undermine the purpose of providing a fresh start to failed entrepreneurs (Fossen and König, 2015[119]). The government should consider making the conditions for early discharge more flexible while maintaining adequate safeguards for creditors.

Figure 1.15. The insolvency regime is among the most efficient in OECD countries

OECD indicator of insolvency regime, composite indicator based on 13 components, 2016

Note: The OECD insolvency regime indicator capture (1) personal costs to failed entrepreneurs that include the time to discharge, (2) lack of prevention and streamlining and (3) barriers to restructuring. Higher values of the composite indicator correspond to more inefficiency.

Source: Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), "Insolvency regimes, zombie firms and capital reallocation", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1399.

Ensuring a competitive business environment

Regulatory barriers to entry in some service sectors prevent new firms from introducing innovative business models that exploit new technologies. Some professional services in Germany remain protected by exclusivity rules and entry regulations. For example, some legal transactions for creating new businesses require notary services at a high regulated price, which also adds to administrative burdens on entrepreneurship.

It is particularly important to ensure that new markets created by digital technologies such as digital platforms remain competitive and open to entry. In highly dynamic digital services, large incumbents often acquire young innovative firms to expand their market dominance. An amendment to the competition law was passed in 2017 empowering the competition authority to investigate mergers and acquisitions (M&A) involving companies with relatively small turnover (less than EUR 5 million) but large transaction value (more than EUR 400 million) (BMWi, 2017[122]). The competition authority can also halt an M&A until the investigation concludes. The contestability of technology-intensive markets can also be preserved by allowing innovative start-ups to grow quickly (see below).

Supporting the innovation and growth by young firms and SMEs

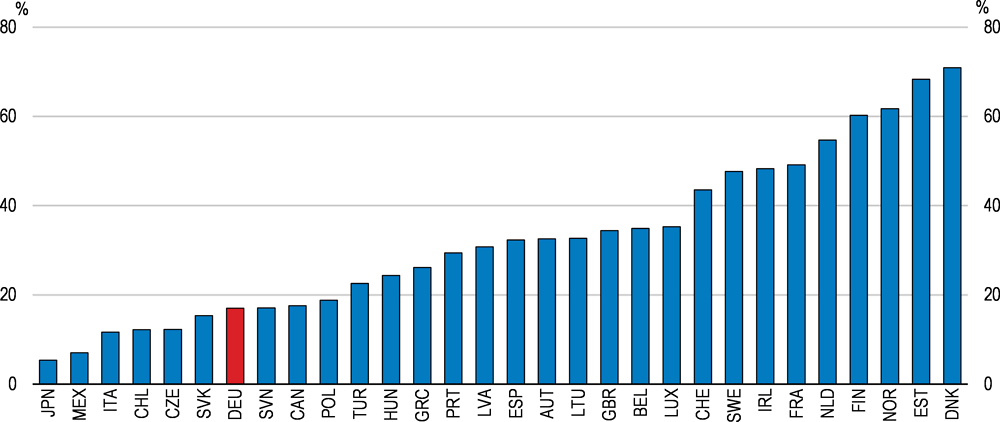

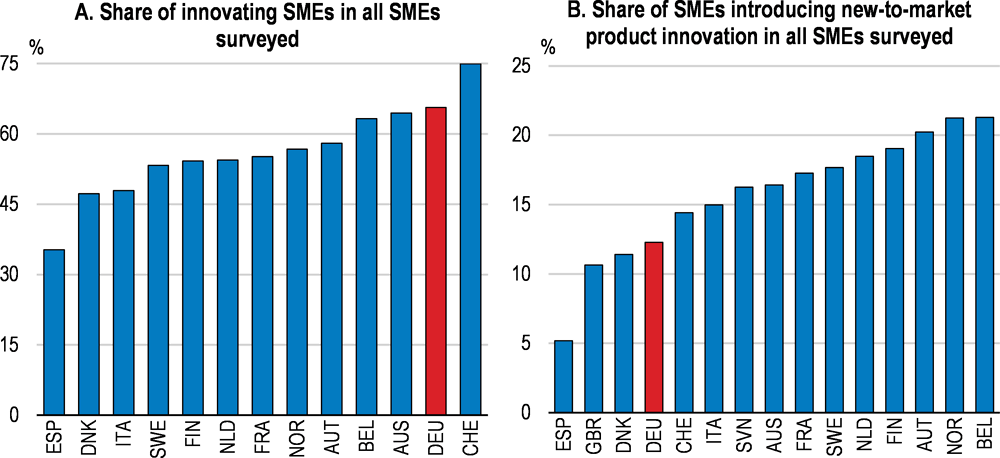

Fast technological diffusion requires smooth resource allocation to innovative firms (Andrews, Criscuolo and Menon, 2014[49]). This is particularly important for start-ups at growth stage and for SMEs which need external funding to carry out drastic innovation. Although SMEs in Germany are on average more innovative than those in other advanced European countries (Figure 1.16, Panel A), they engage in incremental innovation rather than in radical innovation. For instance, fewer SMEs introduce novel products in Germany than in peer countries (Figure 1.16, Panel B). Furthermore, the number of innovating SMEs in Germany is decreasing (KfW, 2016[123]). Subdued innovation activities such as research and development (R&D) hold back productivity growth and also limit the capacity of SMEs to absorb new technologies. In particular, the low take up of digital technologies by SMEs constrains their innovation capabilities, as ICT investment leads to more innovative activity (Fabritz, 2014[124]).

Figure 1.16. German SMEs engage more in incremental innovation

2012-14

Note: Based on the 2017 OECD survey of national innovation statistics and the Eurostat, Community Innovation Survey. International comparability may be limited due to differences in innovation survey methodologies and country-specific response patterns.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017.

The investment costs for radical innovation may be becoming increasingly penalising for SMEs, as they need to spend more for qualified research and development personnel (Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation, 2016[115]). While Germany offers various types of research grants and technical assistance such as Competence Centres, it does not provide tax relief for business R&D activities (Figure 1.17). Most OECD countries combine direct support and tax incentives to stimulate innovation (Appelt et al., 2016[125]). The coalition agreement envisages the introduction of R&D tax incentives. The effectiveness of such tax incentives depends on their design. Many countries provide more generous tax relief to SMEs than large firms by targeting explicitly young firms or SMEs. (Figure 1.17, Panel A). Young firms or smaller firms indeed tend to react more strongly to R&D tax incentives than large firms (Appelt et al., 2016[125]).

In order to fully benefit young and small firms and projects involving basic research, R&D tax incentives often include cash refunds or reductions in social security and payroll taxes. For instance, France’s Crédit d'Impôt Recherche provides young firms and SMEs immediate tax reimbursement on 30% of R&D expenses up to EUR 100 million. France also offers abatement of corporate tax and social security contributions for small firms younger than eight years which spend more than 15% of total expenditure on R&D for a limited period (Jeune Entreprise Innovante programme). The tax incentives should also be designed to allow young firms that are not yet generating taxable profits to be able to benefit. Many countries indeed provide R&D tax relief to loss-making firms (Figure 1.17, Panel B), through a carry forward measure. For example, Ireland allows the R&D credit to be carried forward indefinitely or to be refunded gradually over a three year period that follows the R&D investment.

Figure 1.17. Germany does not provide tax relief to R&D expenditure

Tax subsidy rates on R&D expenditures (1-B-Index), by firm size and profit scenario, 2017

Note: 1-B index is an indicator capturing the extent to which the tax subsidy relieves the R&D costs of firms. It is based on quantitative and qualitative information representing a notional level of tax subsidy rate under different scenarios. It requires a number of assumptions and calculations specific to each country.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2017: The digital transformation.

The effectiveness of R&D tax incentives also depends on the broader regulatory environment and how they are combined with direct support to innovation. Rigorous ex-post evaluation is needed to assess whether R&D tax incentives are stimulating innovation by SMEs in a cost-efficient way.

Start-ups at the growth-phase often find it difficult to finance their investment due to their young age, limited collateral and high risk. Young German high-tech start-ups particularly rely on equity financing (Metzger and Bauer, 2015[126]). Yet, the supply of private venture capital and growth financing is limited (OECD, 2017[94]). In 2017, private equity investment in Germany amounted to EUR 11.3 billion, 80% of which was buyouts (BVK, 2018[127]). Growth financing and venture capital comprised only 12% and 8% of total equity investment, respectively. Several measures promote equity financing for start-ups at different stages of development. They provide government-funded venture capital in partnership with private investors. For example, a public fund provides equity to business angels for financing innovative companies in their early phases, while another finances fast-growing underfunded companies. Altogether, these funds amount to approximately USD 4 billion (OECD, 2017[101]). Furthermore, legislation adopted in 2016 expanded the options for carrying forward losses when a business is sold. This tax reform may increase the supply of venture capital.

Initial public offering (IPO) is a key avenue for innovative start-ups in growth phase to attract sizable capital. It also provides private venture capital with high-return exit opportunities. However, the number of IPOs in Germany has been subdued after the financial crisis (Metzger and Bauer, 2015[126]). The number of IPOs and their value in Germany (Deutsche Börse) is considerably smaller as compared to the United Kingdom (London Stock Exchange), Switzerland (SIX Swiss Exchange) or Sweden (Nasdaq Stockholm) (Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2017[128]). A new market segment in Deutsche Börse for young high growth firms (“Scale”) was launched in 2017, replacing the previous equivalent segment “Entry Standard,” with stricter admission criteria and follow-up obligations. A network was founded by the stock exchange Deutsche Börse for firms that have the potential for an IPO (Deutsche Börse Venture Network), which can provide technical assistance to help young firms seeking IPOs comply with those procedures.

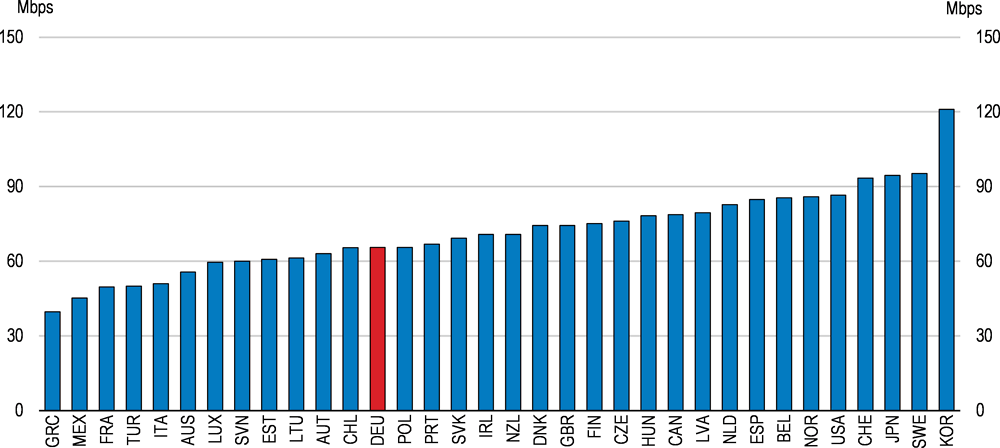

Strengthening competition in high-speed broadband networks

High-speed Internet is a prerequisite for the adoption of many data-intensive new technologies (OECD, 2017[101]). However, the average Internet connection speed is considerably slower in Germany than in peer countries (Figure 1.18). Furthermore, the connection speed to access the Internet varies greatly across regions within Germany. The government and the business community recognise that lagging average Internet connection speed is an important impediment to more intensive use of digital technologies (BMWi, 2017[129]). Meanwhile, related to lower levels of competition, average mobile data use is low in Germany compared to many OECD countries.

Figure 1.18. The internet connection speed is slow

Akamai's average peak connection speed, Q1 2017

Source: Akamai (2017), “Akamai’s state of the Internet report: Q1 2017 report”, https://www.akamai.com.

Expanding use of data-intensive new technologies in the near future, such as autonomous vehicles, will require digital infrastructure with significantly higher transmission capacity. Although network operators are deploying more fibre into their network to cope with the growing demand for data transmission, the deployment of fibre in the final connections to users has been very slow (OECD, 2017[101]). As a result, only 2.1% of broadband subscriptions in Germany are fibre connections, a share that is much smaller than in most other advanced OECD countries (Figure 1.19).

Figure 1.19. Fibre penetration is significantly lower than the OECD average

Percentage of fibre in total broadband subscriptions, June 2017

Note: Fibre subscriptions data includes FTTH, FTTP and FTTB and excludes FTTC.

Source: OECD (2018), Broadband Portal, www.oecd.org/sti/broadband/oecdbroadbandportal.htm.

The government aims at rolling out a comprehensive gigabits network throughout the country by 2025. A public and private sector consortium (Netzallianz Digitales) agreed to invest EUR 100 billion to reach this goal. However, the government acknowledges that a faster pace of investment is needed to reach the goal (BMWi, 2017[122]). It foresees additional public investment especially in rural areas where private, unsubsidised infrastructure provision may not be sufficient (BMWi, 2017[122]). The coalition agreement put forth the Gigabit Fund of EUR 10 to 12 billion using revenues from a forthcoming radio spectrum auction. Public funding for investment projects should be based on cost-benefit analysis.

Private investment in gigabit networks should be accelerated while strengthening competition. The government envisages allowing providers of a fibre access network to charge higher wholesale prices to third parties, in order to make the investment more attractive (BMWi, 2017[122]). However, if this fibre is provided by a new entrant and the access price for the wholesale fibre network is considerably higher than that of a copper network, Internet service providers may prefer to use the existing copper network to provide less expensive services (Briglauer, Cambini and Grajek, 2017[130]), even though the quality of services offered could be substantially higher when using a fibre network. This may reduce the demand for fibre networks and thus the return to such investment. On the other hand, if fibre networks are provided mainly by the incumbent replacing copper networks, the envisaged higher wholesale price would result in higher access prices and a substantial increase of the incumbent’s market power. This would limit access by small firms and by consumers to high-speed Internet services. An alternative path would be lighter regulation for wholesale-only providers of fibre networks.

The efficiency of investment in gigabit networks can be improved by adequate regulation. For example, the government recently introduced regulation making it mandatory to lay fibre optic cables in the construction of new roads and residential buildings, a welcome measure that increases supply of fast networks at lower cost. The government can extend this obligation to the renewal and repair of existing roads and buildings.

Regulation can be used to invigorate competition by promoting market entry in mobile networks. Germany has three mobile network operators. Experience across countries has shown that moving from three to four operators (such as in France) makes a substantial difference for service prices and innovation (OECD, 2014[51]). Higher demand for mobile services would also raise the demand for services on the fixed broadband network, facilitating their quicker deployment and reducing access prices, as scale economies could be utilised. The upcoming spectrum auction for mobile communication is an opportunity to boost market entry. For example, the Canadian government has been setting aside a significant share of radio frequency spectrum to new entrants, in order to promote competition (Industry Canada, 2014[131]). The German government could consider a similar approach to foster new entry for the next radio spectrum auction expected to be used for 5G. The potential demand from new entrants can be large. For instance, Australia, Italy and Singapore are moving from three to four mobile operators in 2018.

German workers need to prepare for the future of work

The diffusion of new technologies has often been associated with concerns that it displaces workers whose tasks and skills are rendered obsolete (Autor, 2015[132]). Routine tasks follow well-defined protocols which can be programmed and executed by computer-controlled machines. While many routine manual tasks have already been automated, digital technologies are now automating routine cognitive tasks often performed by middle-skilled workers (Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003[133]; Goos, Manning and Salomons, 1993[134]).

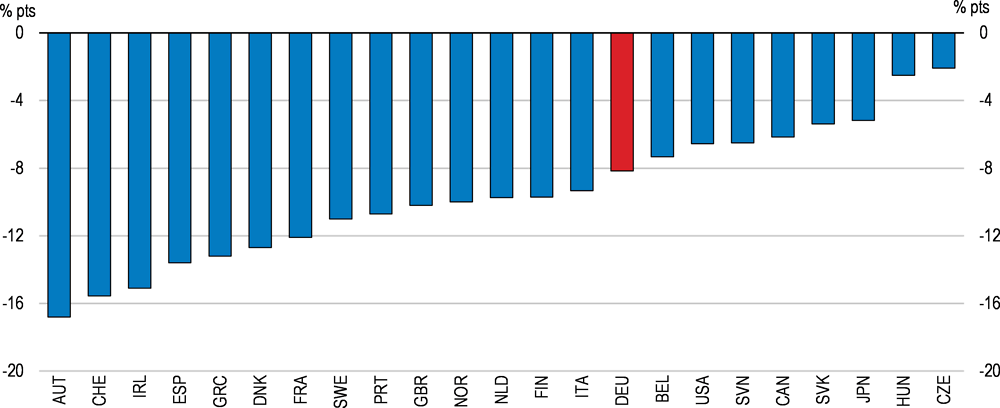

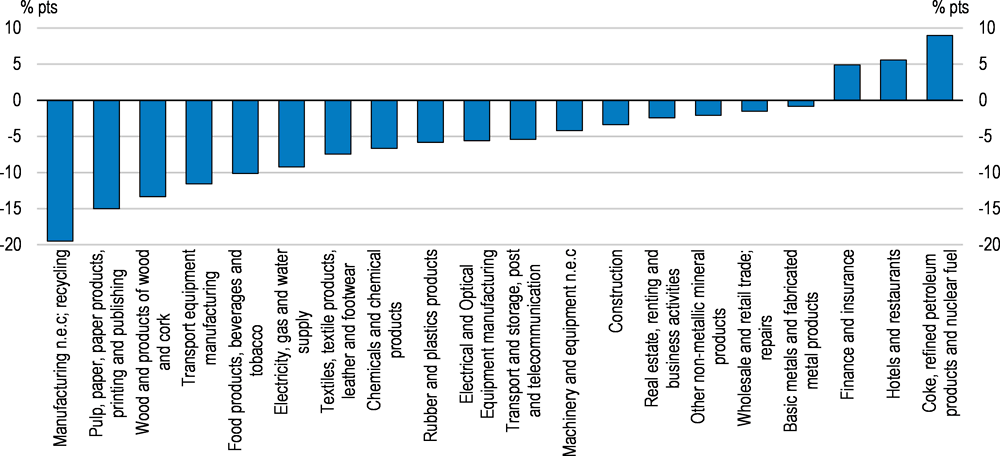

Across OECD countries, the share of jobs requiring mid-level skills has declined (Figure 1.20), while those of high-skilled and low-skilled jobs increased. This phenomenon has also occurred in Germany, although not to the same extent as in Nordic countries and the United Kingdom. While some growing service and sales occupations are classified as low-skilled jobs, they require vocational education and training in Germany and thus may be considered middle-skilled jobs (BDA, 2017[135]). However, such jobs earn only two-thirds of the mean hourly wage in Germany (Eurostat 2014 Structure of Earning Survey). The share of middle-skill jobs in Germany decreased in a wide range of manufacturing industries and important services such as wholesale and retail trade (Figure 1.21). However, it increased in a few sectors such as finance and accommodation. Decreasing middle-skill jobs implies diminished opportunities for low-skilled workers to upskill and move up to jobs that provide decent income and living standards.

Cognitive non-routine tasks typically taken up by high-skilled workers are less likely to be automated (Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003[133]). In particular, digital technologies increase the demand for workers endowed with skills that are complementary, such as advanced reading, numeracy and problem solving skills (OECD, 2016[136]). Those workers are likely to be well remunerated. On the other hand, it is foreseen that the demand for low-skilled workers will decrease in Germany, although not as much as for middle-skilled workers (Warning and Weber, 2017[54]). Low-skilled workers are also likely to suffer wage losses as they compete with displaced middle-skilled workers for low-skilled jobs. The impacts of new technologies on labour demand and earnings inequality are compounded by the “winner-takes-all” product market structure brought about by new technologies such as digital platforms. The large rents generated by such a market structure tend to accrue mostly to top managers and investors financing the innovation (Guellec and Paunov, 2017[137]).

Figure 1.20. The share of middle-skilled jobs in employment has declined

Percentage point change in the share in total employment between1995 and 2015

Note: Middle-skilled occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 4, 7, and 8. These are clerks (group 4), craft and related trades workers (group 7), and plant and machine operators and assemblers (group 8).

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Employment Outlook 2017.

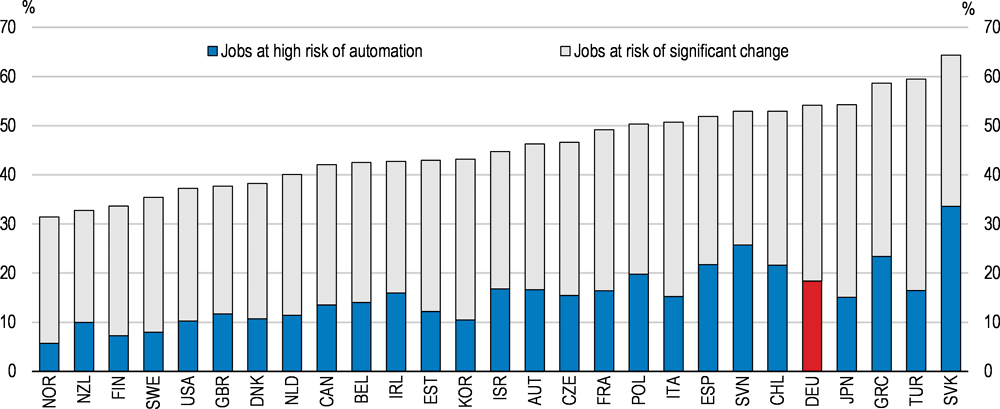

According to estimates using workers’ reports of tasks involved in their job from the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), Germany has a relatively high share of jobs that are at risk of automation (Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[138]). In about one-third of jobs, between 50% and 70% of tasks are at risks of automation (Figure 1.22). While these jobs may not be substituted by machines, workers will need to acquire new skills as these jobs likely will undergo radical transformation.

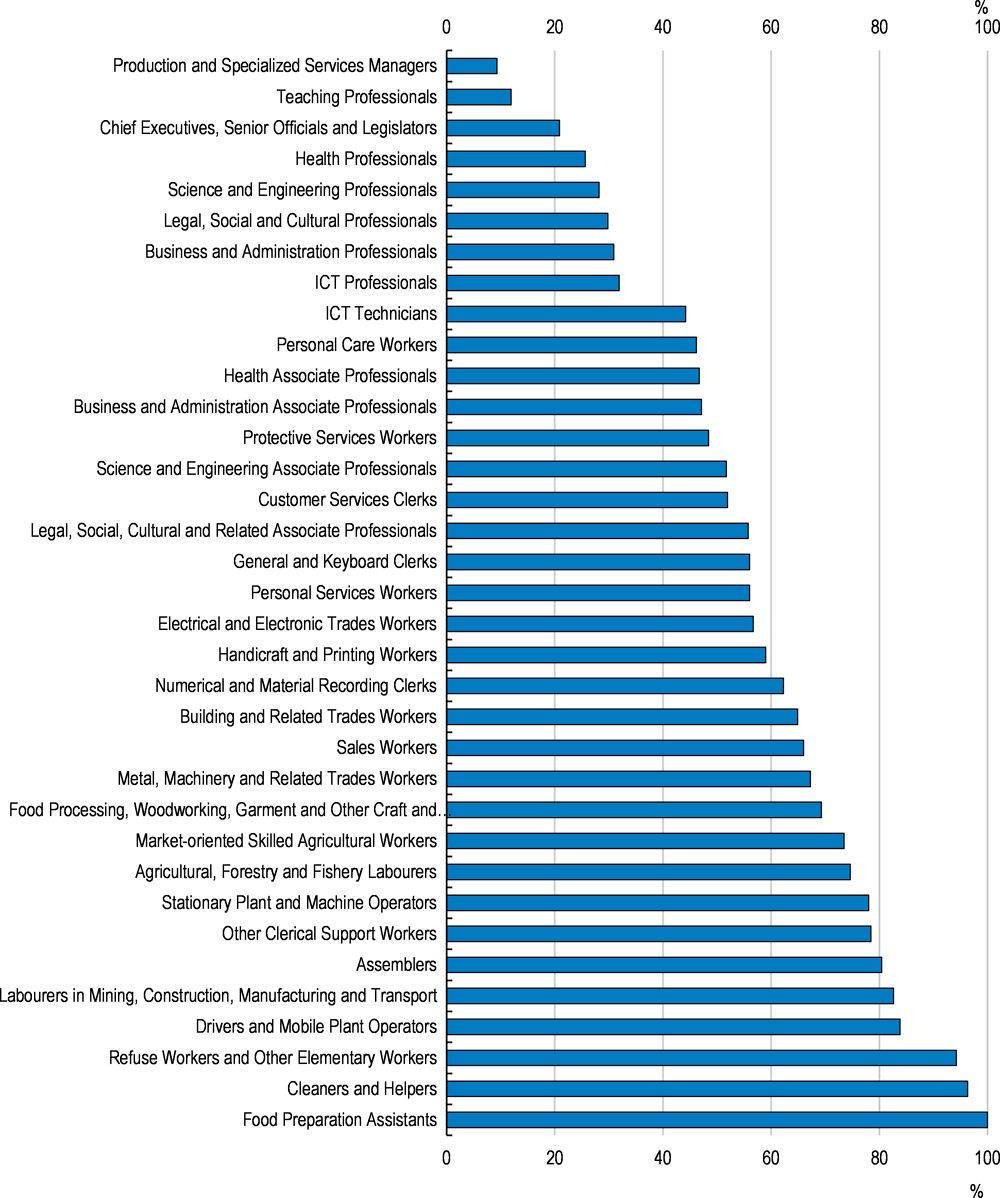

The risk of automation or radical changes in tasks differs substantially across jobs in Germany (Figure 1.23). While low skill routine jobs such as food preparation assistants, cleaners and refuse workers are most prone to such risks, some mid-level skill jobs requiring at least some training such as drivers and machine operators or jobs involving cognitive routine tasks such as clerical support workers are also highly exposed to the risk of automation. On the other hand, managers and professionals with specialised knowledge, who are mostly engaging in non-routine cognitive tasks, are least prone to automation.

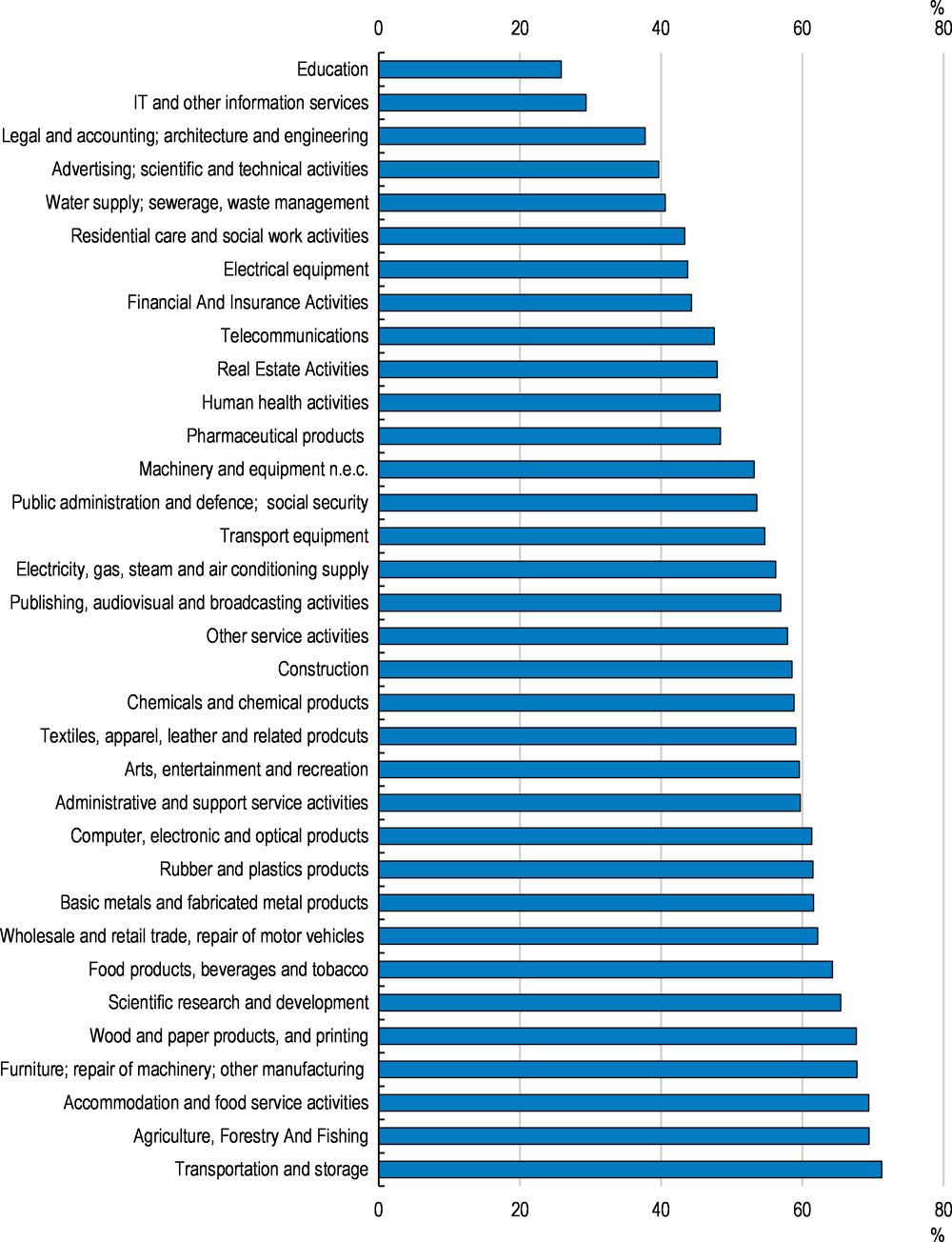

The risk of automation or radical changes in tasks also differs substantially across industries (Figure 1.24). Labour intensive services such as transport and storage, accommodation as well as wholesale and retail trade have the highest shares of jobs that are prone to such risks. These services included 23% of employment in Germany in 2016 (European Labour Force Survey). On the other hand, sectors that already underwent significant digitalisation such as ICT services and telecommunication have relatively low shares of jobs prone to automation. Sectors that are characterised by non-routine cognitive tasks such as education and professional services or non-routine manual tasks like care and social work activities are also less exposed to the risk of automation.

Figure 1.21. Middle-skilled jobs in Germany decreased in a wide range of sectors

Percentage point change in the share in total employment between1995 and 2015

Note: Middle-skilled occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 4, 7, and 8. That is, clerks (group 4), craft and related trades workers (group 7), and plant and machine operators and assemblers (group 8).

Source: OECD calculations based on European Labour Force Survey.

Figure 1.22. Many jobs are at risks of significant change

The share of jobs at high risk of automation and significant change

Note: Jobs are at high risk of automation if the likelihood of their job being automated is at least 70%. Jobs are at risk of significant change if the likelihood is between 50 and 70%.

Source: Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), "Automation, skills use and training", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Figure 1.23. Low- to mid-level skill jobs face particularly high risk of automation

The share of jobs at high risk of automation and significant change, by occupation

Note: Jobs are at high risk of automation if the likelihood of their job being automated is at least 70%. Jobs are at risk of significant change if the likelihood is between 50% and 70%.

Source: Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), "Automation, skills use and training", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Figure 1.24. Manufacturing and some services face particularly high risk of automation

The share of jobs at high risk of automation and significant change, by industry

Note: Jobs are at high risk of automation if the likelihood of their job being automated is at least 70%. Jobs are at risk of significant change if the likelihood is between 50% and 70%.

Source: Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), "Automation, skills use and training", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The current trends in the labour market driven by digitalisation indicate the need to prepare many workers for new jobs and tasks shaped by digital technologies. To this end, the coalition agreement foresees strengthening preventative active labour market policies to increase the employability of workers, especially at old age, through continuous skill updating and career counselling. It also envisages increasing participation in lifelong learning. While these initiatives are welcome, low- and middle skilled workers whose jobs are most vulnerable to technological change participate less in lifelong learning than high-skilled workers (OECD, 2016[9]). Efforts to reach out to low- and middle skilled workers and encourage their upskilling are needed to ensure the effectiveness of those measures. Chapter 2 elaborates on skill formation and its effective use.

Higher flexibility in work must be flanked by effective worker protection

Preventing exploitation under flexible work arrangements

Digital technologies offer opportunities for more flexible work arrangements which allow workers to balance work with family obligations and leisure. German workers indeed express strong preference for more autonomy with respect to where and when to work (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 2017[139]). Especially for working parents, being able to work at least partially from home improves work-life balance considerably. Increasingly many German parents express wish for such work arrangement, but often face unavailability due to their employers not offering such an option (Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, 2016[140]). At the same time, flexible work arrangements increase risks of overwork and breakdown of boundaries between work and private life that impact worker’s health negatively. Also, diffusion of new digital technologies are shaping new norms so that workers are expected to be reachable outside working hours, which can jeopardise work-life balance (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 2017[139]).

Germany’s Working Time Act contains regulations that are stricter than the European Working Time Directive. For instance, the working hour limit is on a daily basis (eight hours per day) instead of weekly, and the rest day is designated as Sunday. Those regulations may limit work flexibility in Germany compared to other European countries (The Council of Economic Experts, 2017[141]). Although the Working Time Act already includes provisions to extend the daily working hours upon collective agreement, it is worth assessing if such provisions are sufficient for fully reaping the benefits of flexible work arrangements. In the near term, there may be a case for allowing employers and employees to choose between daily or weekly limits on working hours through collective agreement, while maintaining the general daily limit as default where such agreements do not exist. In the medium term, comprehensive legislation stipulating a worker’s right to choose the length of working time or scheduling of their working time should be introduced. This view was also expressed in a white paper by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 2017[139]) although it does not represent the official government view.

Extending protection to the self-employed working on digital platforms

Digital platforms facilitate more efficient matching between the demand and supply of labour, products and tasks. This creates greater opportunities for workers to enjoy the flexibility and benefits of freelancing, and to combine several jobs. As more workers take up short-term one-off jobs (gig work) on digital platforms, the number of self-employed workers, especially those without employees (solo self-employed) is likely to rise. Not all platform workers are (solo) self-employed, because there are employees, students or pensioners who also work on digital platforms to earn additional income. On the other hand, some (solo) self-employed working on digital platforms can be regarded as employees, if they are bound to rules on working hours and places of work or are dependent on equipment and tools provided by the platform or the customer (Waas et al., 2017[142]). They can also be regarded as “employee-like persons” if their primary income depends on the revenue from the work they receive via a specific platform or customer (Waas et al., 2017[142]).

The share of solo self-employed in Germany has been rising since the 1990s but declined somewhat in recent years to 5%. This contrasts with some countries such as the United Kingdom or the Netherlands where the share surged. However, the current strong labour market performance may be masking a structural increase in solo self-employment facilitated by digital platforms, as opportunities to work as an employee are abundant.

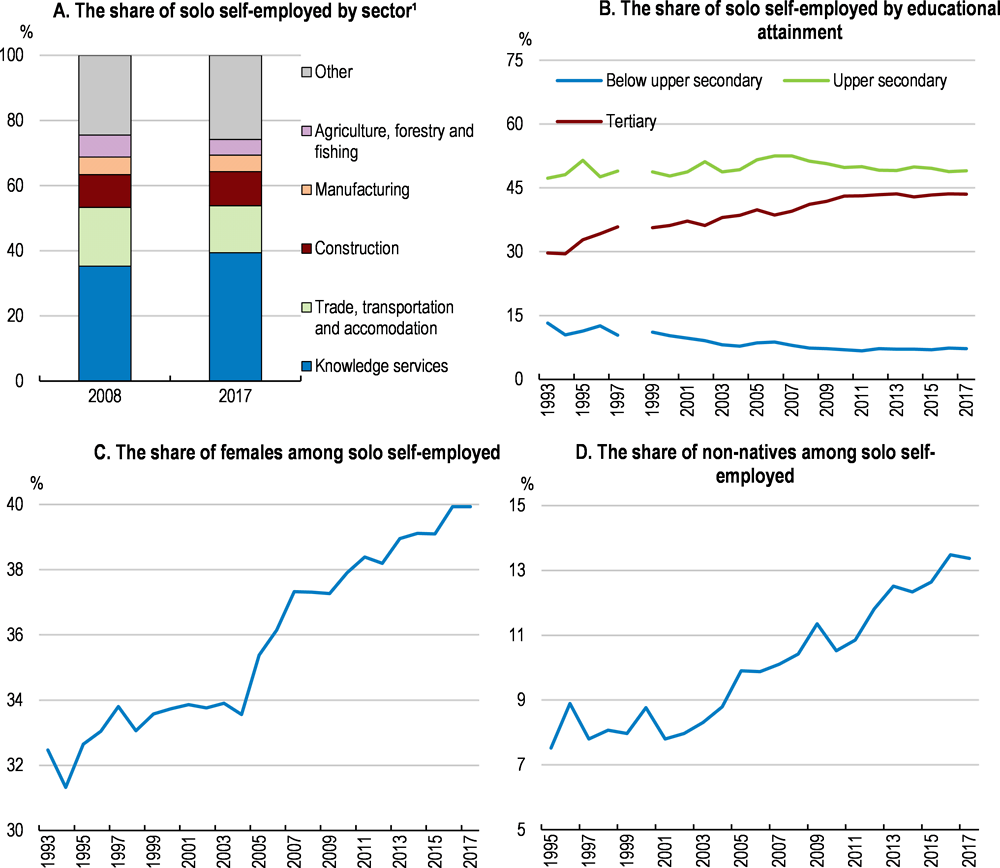

Solo self-employed include diverse types of workers. Some 40% of the solo self-employed engage in knowledge-intensive activities such as professional services, information and communication, art and entertainment, teaching and finance (Figure 1.25, Panel A). Also, they have become more likely to be highly educated (Figure 1.25, Panel B). On the other hand, one-third of solo self-employed engage in less technology intensive activities such as health and social work, wholesale and retail and construction. Some individuals choose solo self-employment out of necessity, for instance because standard employment does not provide sufficient work flexibility or income (Conen, Schippers and Schulze Buschoff, 2016[107]). The share of women and immigrants in solo self-employment have been rising (Figure 1.25, Panel C and D). About 40% of solo self-employed are women. The share of immigrants is likely to rise further as some refugees who are granted asylum may start their own businesses.

As in many countries, measures to protect workers from exploitative work conditions in Germany are intended for employees and do not extend to most of the self-employed. For instance, the statutory minimum wage does not apply to the self-employed. There are also no legal measures to protect the self-employed from excessive working hours or job termination, and this also applies to self-employed workers who rely on digital platforms for employment. The self-employed also do not enjoy paid holidays and paid sick leave, which are guaranteed by law for employees. The self-employed are also not covered by the mandatory accident insurance against workplace injuries, except for few occupations. They enrol on voluntary basis to insurance provided by professional associations (Berufsgenossenschaft) and pay the contributions themselves. Such gaps in protection measures between employees and the (solo) self-employed are problematic when the self-employed are employee-like persons.

The self-employed are often not covered by the social protection that workers with standard employment contracts enjoy. In particular, with exception of some professionals, the self-employed in Germany are not covered by the mandatory public pension. This raises the risks of old-age poverty where the self-employed have to rely on social assistance benefits during their retirement (Spasova et al., 2017[143]). Extending the coverage of mandatory public pension to the self-employed allows Germany to prepare for the future of work. The new government indeed plans to introduce compulsory pension insurance for the self-employed, eventually including them in the public pay-as-you-go pension scheme. Inclusion in the public pension system appears to be the most effective, for example to cover disability risks, ensure integration with the means-tested minimum pension and avoid mobility barriers.

Figure 1.25. The solo self-employed in Germany are diverse

15-64 year-olds

Note: Classification of economic activities based on NACE Rev. 2.

Source: Eurostat (2018), Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) Statistics.

The self-employed in Germany are required to enrol in health insurance but are not covered by the public health insurance unless they were insured by public insurance before becoming self-employed (Spasova et al., 2017[143]). They must instead purchase private insurance with contributions that are not income contingent. The self-employed earning low income often face difficulties in paying such contributions (OECD, 2014[144]). The government should allow all self-employed to enrol in public healthcare insurance.

Establishing bargaining frameworks for platform workers

Some workers providing services on digital platforms can be comparable to employees (see above). Yet, platform workers tend to receive lower compensation compared to dependent employees doing the same job (Katz and Krueger, 2016[145]). Their bargaining power with respect to customers or platform providers can be weakened by the lack of representation and collective bargaining framework. Increasing the representation of platform workers would allow them to engage in effective bargaining for their remuneration as well as for benefits such as workplace injury insurance.

European competition regulation forbids independent contractors from bargaining collectively (OECD, 2017[146]). However, such regulation does not apply to the self-employed that are deemed as employee or employee-like persons. Also, the Collective Agreement Act allows trade unions and professional associations to engage in bargaining on behalf of the self-employed, if they are deemed employee-like persons (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 2017[139]). The government is providing support for online platform workers to organise. Some social partners have engaged to set up a guideline for the contract relation on digital platforms. Further steps to establish an effective bargaining framework for platform workers that are deemed as employee-like persons are warranted.

Recommendations for boosting productivity and preparing forthe future of work

Strengthen entrepreneurship

Ease the conditions for bankrupt entrepreneurs to be discharged of debt after three years while maintaining adequate safeguards for creditors.

Create a one stop shop to process all procedures for starting up a company online.

Encourage firms to increase women’s presence in the highest decision making bodies.

Promote competition in and expand higher speed broadband networks

Use the upcoming radio spectrum auction to promote competition in the mobile market.

Consider reserving a part of the auction of radio spectrum for new entrants.

Foster deeper and faster deployment of fibre in fixed networks through competition, such as that generated by municipal networks, particularly in smaller cities and rural areas.

In the absence of sufficient infrastructure competition, continue to ensure that access seekers have the ability to provide services over fibre networks, particularly those that involve public funding. Also look for opportunities to lighten regulations for wholesale-only networks.

Strengthen the protection of workers with flexible work arrangements

Make enrolment in public old-age pension mandatory for the self-employed who are not covered by old-age pension insurance.

Open access to public health insurance to all self-employed.

Support platform workers deemed to be employee-like persons to get organised.

References

[92] Adalet McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2015), “Labour Market Mismatch and Labour Productivity: Evidence from PIAAC Data”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1209, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5js1pzx1r2kb-en.

[121] Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), “Insolvency regime, zombie firms and capital reallocation”, Economic Department Working Paper, No. 1399, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5a16beda-en.

[42] Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), “Insolvency regimes, zombie firms and capital reallocation”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1399, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5a16beda-en.

[179] Agasisti, T. et al. (2018), “Academic resilience: What schools and countries do to help disadvantaged students succeed in PISA”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 167, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e22490ac-en.

[70] Agora Energiewende (2016), The Power Market Pentagon, Agora Energiewende.

[87] Ahrend, R. and A. Schumann (2014), “Does Regional Economic Growth Depend on Proximity to Urban Centres?”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2014/7, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz0t7fxh7wc-en.

[205] Aizenman, J. et al. (2017), Vocational Education, Manufacturing, and Income Distribution: International Evidence and Case Studies, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w23950.

[189] Alt, C. et al. (2017), DJI-Kinderbetreuungsreport 2017; Inanspruchnahme und Bedarfe aus Elternperspektive im Bundesländervergleich, Deutsches Jugendinstitut, https://www.dji.de/fileadmin/user_upload/bibs2017/DJI_Kinderbetreuungsreport_2017.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2018).

[194] Anders, Y. et al. (2011), “Home and preschool learning environments and their relations to the development of early numeracy skills”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 27, pp. 231-244, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.08.003.

[174] Andrews, D., A. Caldera Sánchez and Å. Johansson (2011), Housing Markets and Structural Policies in OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris,, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kgk8t2k9vf3-en.

[93] Andrews, D., C. Criscuolo and P. Gal (2016), “The best versus the rest: the global productivity slowdown, divergence across firms and the role of public policy”, OECD Productivity working papers, No. 05, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/63629cc9-en..

[49] Andrews, D., C. Criscuolo and C. Menon (2014), “Do Resources Flow to Patenting Firms?: Cross-Country Evidence from Firm Level Data”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1127, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz2lpmk0gs6-en.

[125] Appelt, S. et al. (2016), “R&D Tax Incentives: Evidence on design, incidence and impacts”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 32, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlr8fldqk7j-en.

[36] Arentz, O. et al. (2016), “Der Dienstleistungssektor in Deutschland-Überblick und Deregulierungspotenziale”, Otto-Wolff-Discussion Paper, Instituts für Wirtschaftspolitik an der Universität zu Köln, https://www.iwp.uni-koeln.de/fileadmin/contents/dateiliste_iwp-website/publikationen/DP/OWIWO_DP_01a_2015_rev_2.pdf (accessed on 04 June 2018).

[132] Autor, D. (2015), “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 29/3, pp. 3-30.

[133] Autor, D., F. Levy and R. Murnane (2003), “The skill content of recent technological change: an empirical exploration”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118/4, pp. 1279–1333.

[53] Autor, D., F. Levy and R. Murnane (2003), “The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118/4, pp. 1279–1333.

[191] Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung (2016), Bildung in Deutschland 2016. Ein indikatorengestützter Bericht mit einer Analyse zu Bildung und Migration., Bertelsmann Verlag, Bielefeld.

[135] BDA (2017), Labour market on an OECD comparison: good marks for Germany.

[112] Bear, S., N. Rahman and C. Post (2010), “The Impact of Board Diversity and Gender Composition on Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Reputation”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 97, pp. 207-221.

[97] Belitz, H. et al. (2017), “Wissensbasiertes Kapital in Deutschland: Analyse zu Produktivitäts-und Wachstumseffekten und Erstellung eines Indikatorsystems Studie im Auftrag Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie”, DIW Berlin.

[96] Belitz, H., M. Le Mouel and A. Schiersch (2018), Company productivity increases with more knowledge-based capital, DIW Berlin.

[233] Bertelsmann Stiftung (2018), Formale Unterqualifikation auf dem deutschen Arbeitsmarkt.

[230] Bertelsmann Stiftung (2018), Ungelernte Fachkräfte: Formale Unterqualifikation.

[198] Bertelsmann Stiftung (2017), Länder-Monitor Frühkindliche Bildungssysteme.

[85] Bertelsmannstiftung (n.d.), Demographischer Wandel: Bevölkerung - neue Berechnung, https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/unsere-projekte/wegweiser-kommunede/projektnachrichten/bevoelkerungsvorausberechnung/ (accessed on 9 January 2018).

[129] BMWi (2017), Monitoring Report | Compact DIGITAL Economy 2017, Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, http://www.bmwi.de (accessed on 05 February 2018).

[122] BMWi (2017), White paper digital platforms-Digital regulatory policy for growth, innovation, competition and participation, BMWi, https://www.de.digital/DIGITAL/Redaktion/EN/Publikation/white-paper.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 08 January 2018).

[180] Borgonovi, F. and J. Pál (2016), “A Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-Being in the PISA 2015 Study”, OECD Education Working Papers 40, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlpszwghvvb-en.

[58] Borgonovi, F. and J. Pál (2016), “A Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-Being in the PISA 2015 Study: Being 15 In 2015”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 140, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlpszwghvvb-en.

[203] Bos, W. (2014), ICILS 2013: Computer- und informationsbezogene Kompetenzen von Schülerinnen.

[91] Boulhol, H. and L. Turner (2009), “Employment-Productivity Trade-off and Labour Composition”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 698, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/224146182015.

[105] Breschi, S., J. Lassébie and C. Menon (2018), “A portrait of innovative start-ups across countries”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2018/2, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f9ff02f4-en.

[130] Briglauer, W., C. Cambini and M. Grajek (2017), “Speeding Up the Internet: Regulation and Investment in European Fiber Optic Infrastructure”, Discussion Paper, No. 17-028, ZEW.

[98] Brynjolfsson, E., L. Hitt and S. Yang (2002), “Intangible Assets: Computers and Organizational Capital Paper 138”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Macroeconomics, Vol. 1, pp. 137-199.

[238] Bundesagentur für Arbeit((n.d.)), Fördermöglichkeiten in der beruflichen Weiterbildung, https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/karriere-und-weiterbildung/foerderung-berufliche-weiterbildung (accessed on 25 January 2018).

[153] Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (2016), VET Data Report Germany 2015.

[161] Bundesinstitut für Berusbildung (2017), Jahresbericht 2016.

[165] Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung (2017), Arbeitszeit neu gedacht!, Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung.

[236] Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung((n.d.)), Weiterbildung, https://www.bmbf.de/de/weiterbildung-71.html (accessed on 25 January 2018).

[200] Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2016), Frühe Bildung weiterentwickeln und finanziell sichern.

[127] BVK (2018), The German Private Equity Market 2017 and Outlook for 2018, Deutscher Kapitalbeteiligungsgesellschaften eV, Bundesverband, https://www.bvkap.de/sites/default/files/press/20180226_presentation_bvk_annual_statistics_2017_engv1.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2018).

[172] Caliendo, M., S. Künn and R. Mahlstedt (2017), “The return to labor market mobility: An evaluation of relocation assistance for the unemployed”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 148, pp. 136-151, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.JPUBECO.2017.02.008.

[117] Calvino, F., C. Criscuolo and C. Menon (2016), “No Country for Young Firms?: Start-up Dynamics and National Policies”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 29, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jm22p40c8mw-en.

[183] Causa, O. and Å. Johansson (2010), “Intergenerational Social Mobility in OECD Countries”, OECD Journal: Economic Studies,, Vol. Volume 2010,, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-2010-5km33scz5rjj.

[240] CEDEFOP (2017), European Inventory on Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning, European Union.

[163] CEDEFOP (2017), European Skills and Jobs Survey.

[178] Chapman, B. (2006), Income Contingent Loans for Higher Education: International Reforms, Elsevier, North Holland.

[33] Clamor, T. and R. Henger (2013), “Verteilung des Immobilienvermögens in Deutschland”, IW-Trends, Vol. 40, pp. 69–82.

[48] Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation (2017), Research, innovation and technological performance in Germany - Report 2017.

[114] Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation (2017), Research, Innovation and technological performance in Germany - Report 2017, http://www.e-fi.de/fileadmin/Gutachten_2017/EFI_Report_2017.pdf (accessed on 08 January 2018).

[115] Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation (2016), Research, innovation and technological performance in Germany- Report 2016, http://www.e-fi.de/fileadmin/Gutachten_2016/EFI_Report_2016.pdf (accessed on 08 January 2018).

[45] Conen, W., J. Schippers and K. Schulze Buschoff (2016), Self-employed without personnel. Between freedom and insecurity, WSI (The Institute of Economic and Social Research Hans-Boeckler-Foundation).

[107] Conen, W., J. Schippers and K. Schulze Buschoff (2016), Self-employed without personnel: Between freedom and insecurity, The Institute of Economic and Social Research Hans-Boeckler-Foundation.

[227] De Grip, A. (2015), The Importance of Informal Learning at Work, http://dx.doi.org/doi: 10.15185/izawol.162.

[84] Deschermeier, P. (2017), Bevölkerungsentwicklung in den deutschen Bundesländern bis 2035, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln, http://dx.doi.org/10.2373/1864-810X.17-03-04.

[67] Desjardins, R. (2017), Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems: Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies and Constraints, Bloomsbury Academic.

[225] Desjardins, R. (2017), Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems: Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies and Constraints, Bloomsbury Academic.

[6] Deutsche Bundesbank (2018), Monatsbericht Februar 2018.

[10] Deutsche Bundesbank (2017), Financial Stability Review 2017.

[13] Deutsche Bundesbank (2017), The performance of German credit institutions, September 2017..

[5] Deutsche Bundesbank (2016), The Phillips curve as an instrument for analysing prices and forecasting inflation in Germany, pp. 31-46.

[237] Deutsches Institut für Internationale Pädagogische Forschung (2018), InfoWeb Weiterbildung, http://German Institute for International Educational Research.

[18] DIW/ZEW (2017), Entwicklung der Altersarmut bis 2036, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh.

[31] Downes, R., D. Moretti and S. Nicol (2017), “Budgeting and performance in the European Union: A review by the OECD in the context of EU budget focused on results”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 17/1 OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/budget-17-5jfnx7fj38r2.

[210] Effenberger, A. et al. (2018), How do educational attainment and age influence the consequences of job loss? An empirical study using longitudinal individual data from Germany.

[35] Égert, B. and P. Gal (2017), “The quantification of structural reforms in OECD countries: A new framework”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1354, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2d887027-en.

[204] Eickelmann, B., W. Bos and J. Gerick (2015), Wie geht es weiter? Zentrale Befunde der Studie ICILS 2013 und mögliche Handlungs- und Entwicklungsperspektiven für Einzelschulen. Schulverwaltung NRW.

[213] Euler and Severing (2016), Durchlässigkeit zwischen beruflicher und akademischer Bildung P o s it io n b e z ie h e n P r a x is g e s t a lt e n H in t e r g r ü n d e k e n n e n, https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/LL_GP_Durchlaessigkeit_Praxis_final.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2017).

[29] European Commission (2017), Quality of public finances: Spending reviews for smarter expenditure allocation.

[34] European Commission (2015), 2015 Ageing Report.

[215] European Commission, Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (2015), An in-depth analysis of adult learning policies and their effectiveness in Europe.

[66] Eurostat (2018), Education and training Statistics (database)..

[124] Fabritz, N. (2014), Investment in ICT: Determinants and Economic Implications, ifo Institut.

[100] Färnstrand Damsgaard, E. et al. (2017), “Why Entrepreneurs Choose Risky R&D Projects - But Still Not Risky Enough”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 127/605, pp. F164-F199.

[140] Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, W. (2016), Digitalisierung – Chancen und Heraus- forderungen für die partnerschaftliche Vereinbarkeit von Familie und Beruf.

[80] Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Consservation and Nuclear Safety (2016), Kurzinformation Elektromobilität bzgl. Strom- und Ressourcenbedarf.

[50] Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy (2017), White Paper Digital Platforms-Digital regulatory policy for growth, innovation, competition and participation.

[27] Federal Ministry of Finance (2017), “Wirkungsorientierung im Bundeshaushalt - mehr als Spending Reviews”, Monatsbericht September, pp. 34-40.

[15] Federal Ministry of Finance (2016), Vierter Bericht zur Tragfähigkeit der öffentlichen Finanzen.

[139] Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (2017), White Paper Work 4.0, http://www.bmas.de/EN/Services/Publications/a883-white-paper.html (accessed on 15 November 2017).

[72] Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure (2017), Verkehr in Zahlen 2017/2018.

[209] Forster, A. et al. (2016), “Vocational Education and Employment over the Life Cycle”, Sociological Science, Vol. 3, pp. 473-494, http://dx.doi.org/10.15195/v3.a21.

[120] Fossen, F. (2014), “Personal Bankruptcy Law, Wealth, and Entrepreneurship--Evidence from the Introduction of a "Fresh Start" Policy”, American Law and Economics Review, Vol. 16/1, pp. 269-312.

[43] Fossen, F. and J. König (2015), “Personal Bankruptcy Law and Entrepreneurship”, CESifo DICE Report, Vol. 13/4, pp. 28-34.

[119] Fossen, F. and J. König (2015), “Personal Bankruptcy Law and Entrepreneurship”, CESifo DICE Report, Vol. 13/4, pp. 28-34.

[229] Gaylor, C., N. Schöpf and E. Severing (2015), Wenn aus Kompetenzen berufliche Chancen werden, Bertelsmann Stiftung.

[11] German Council of Economic Experts (2016), Time for reforms. Annual report 2016/17.

[134] Goos, M., A. Manning and A. Salomons (1993), “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring”, American Economic Review, Vol. 104/8, pp. 2509-2526.

[211] Goos, M., A. Salomons and A. Manning (2014), “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring”, American Economic Review, Vol. 104/8, pp. 2509-2526.

[8] Grömling, M. (2014), “A supply-side explanation for current account imbalances”, Intereconomics, Vol. 49/1, pp. 30-35.

[162] Grundke, R. et al. (2017), “Having the right mix: The role of skill bundles for comparative advantage and industry performance in GVCs”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2017/03, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/892a4787-en.

[137] Guellec, D. and C. Paunov (2017), “Digital Innovation and the Distribution of Income”, NBER Working Paper Series, No. 23987, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge.

[167] Haan, P., A. Hammerschmid and C. Rowold (2017), “Geschlechtsspezifische Renten- und Gesundheitsunterschiede in Deutschland, Frankreich und Dänemark”, DIW Wochenbericht, Vol. 84 (2017), pp. 971-974.

[65] Hampf, F. and L. Woessmann (2016), “Vocational vs. General Education and Employment over the Life-Cycle: New Evidence from PIAAC”, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 10298.

[208] Hampf, F. and L. Woessmann (2016), “Vocational vs. General Education and Employment over the Life-Cycle: New Evidence from PIAAC”, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 10298, IZA.

[55] Hanushek, E. et al. (2017), “Coping with change: International differences in the returns to skills”, Economics Letters, Vol. 153, pp. 15-19.

[152] Hanushek, E. et al. (2017), “Coping with change: International differences in the returns to skills”, Economics Letters, Vol. 153, pp. 15-19, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2017.01.007.

[148] Hanushek, E. et al. (2015), “Returns to skills around the world: Evidence from PIAAC”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.10.006.

[149] Hanushek, E. et al. (2015), “General Education, Vocational Education, and Labor-Market Outcomes over the Life-Cycle *”, http://hanushek.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/hswz%20vocational%20final.pdf (accessed on 06 November 2017).

[38] Hanushek, E. and L. Woessmann (2008), “The Role of Cognitive Skills in Economic Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 463, pp. 607-668.

[147] Hanushek, E. and L. Woessmann (2008), “The Role of Cognitive Skills in Economic Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 463, pp. 607-668, http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jel.46.3.607.

[157] Heublein, U. et al. (2017), “Zwischen Studienerwartungen und Studienwirklichkeit”, Forum Hochschule 2017.

[74] Hochfeld, C. et al. (2017), Transforming Transport to Ensure Tomorrow’s Mobility: 12 Insights into the Verkehrswende, Agora Verkehrswende.

[207] Hoeckel, K. and R. Schwartz (2010), A Learning for Jobs Review of Germany. OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training., OECD, http://pac-files.oecd.org/acrobatebook/9111091e.pdf (accessed on 09 December 2017).

[110] Holst, E. and K. Wrohlich (2018), “Top-decision making bodies of large businesses: gender quota for supervisory boards is effective—development is almost at a standstill for executive boards”, DIW Weekly Report, Vol. 3, pp. 17-31, http://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.575403.de/dwr-18-03.pdf (accessed on 06 February 2018).

[131] Industry Canada (2014), Technical, Policy and Licensing Framework for Advanced Wireless Services in the Bands 1755-1780 MHz and 2155-2180 MHz (AWS-3), Spectrum Management and Telecommunications, https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/smt-gst.nsf/vwapj/SLPB-007-14E.pdf/$file/SLPB-007-14E.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2018).

[40] INRIX (2017), “Parking Pain Infographic for Germany”, The Impact of Parking Pain in the US, UK and Germany.

[39] INRIX (2016), INRIX 2016 Traffic scorecard Germany: Ein Leitfaden zur Stausituation in Deutschland.

[212] Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (2015), Berufsausbildung für Europas Jugend, Länderbericht Deutschland.