Recent macroeconomic developments and short-term prospects

Monetary, financial and fiscal policies to promote stability and well-being

Addressing longer-run challenges to well-being

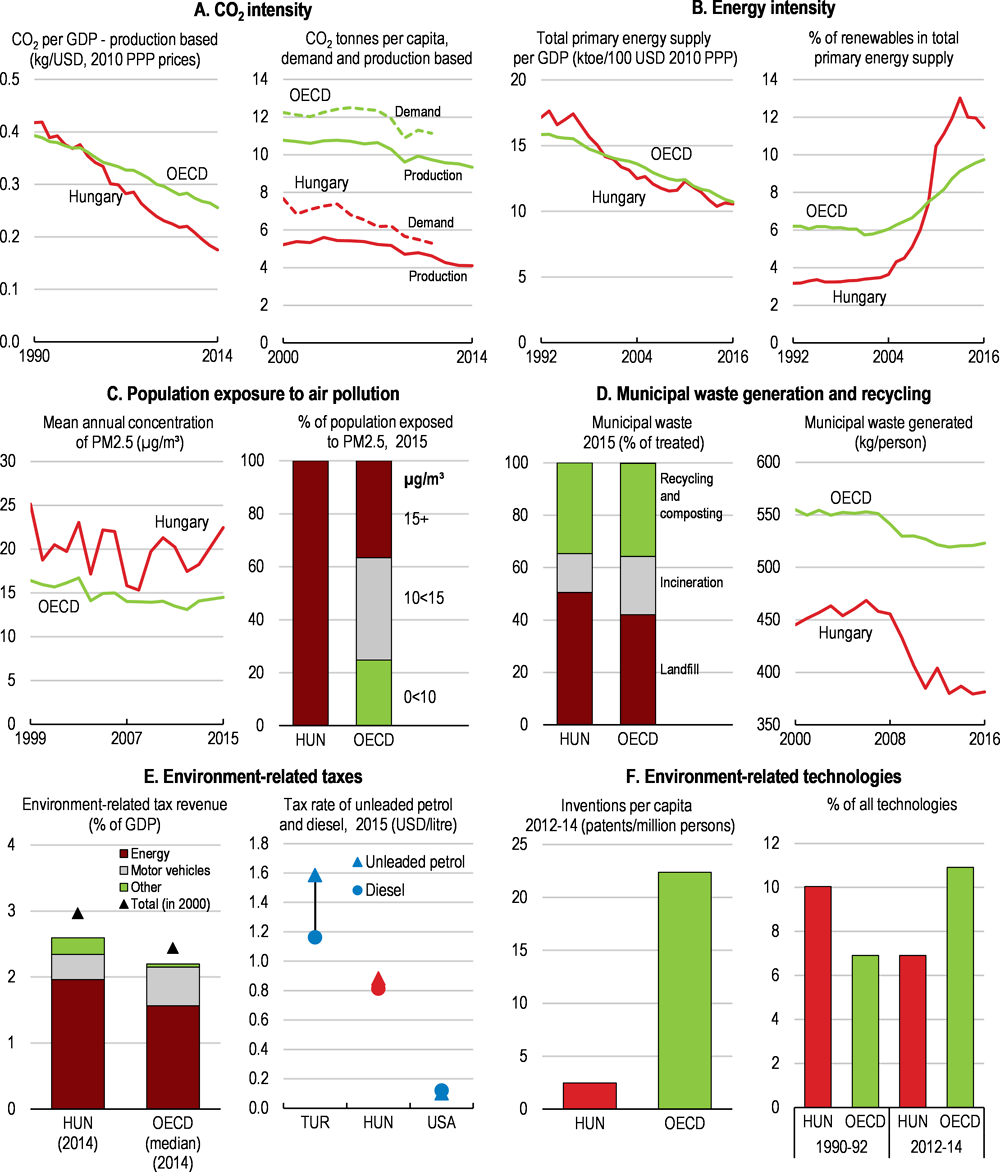

Greening growth requires mitigation of small particles emissions

OECD Economic Surveys: Hungary 2019

Key Policy Insights

Abstract

Key Policy Insights

The economy has grown strongly over the past five years. In 2017, growth exceeded 4% - a pace that the economy maintained in 2018 (Table 1). Initially, growth was driven by exports and then investments. As employment started to expand, the recovery has broadened to private consumption and housing investment; a development that is being reinforced by double-digit wage growth. Moreover, the economy is increasingly facing capacity constraints, leading to higher imports eroding the current account surplus.

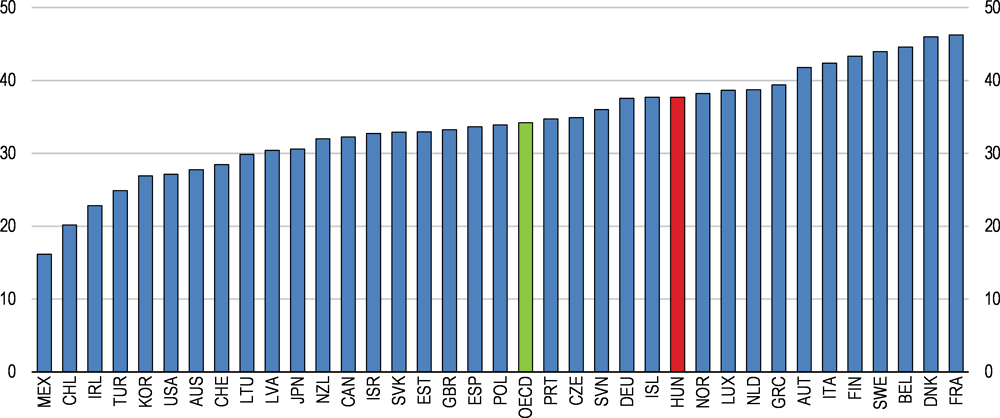

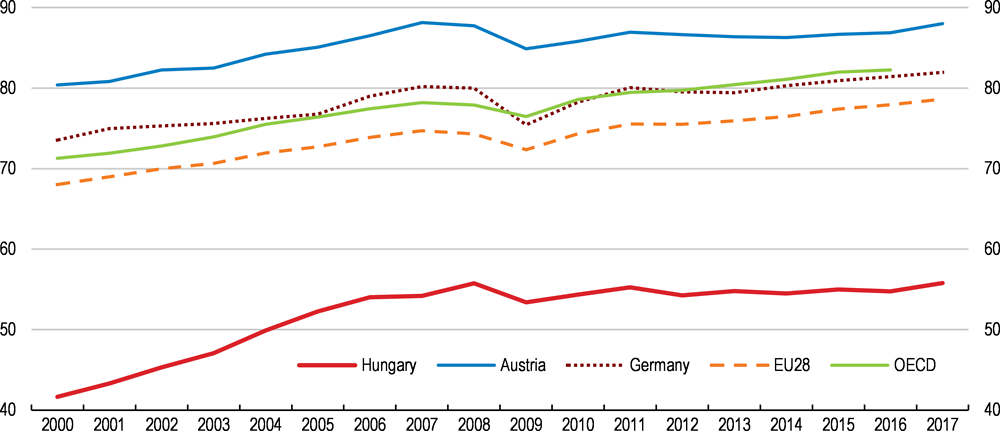

Since the early 1990s, the main growth driver of the Hungarian economy has been foreign direct investments that have helped modernising production and supported the successful integration into global value chains. Nonetheless, income per capita remains low, but convergence towards OECD and EU average incomes has started to resume. Per capita GDP has reached two-thirds of the OECD average and slightly more in comparison with the EU average (Figure 1).

The high reliance on foreign direct investment to drive growth has led to a regionally unbalanced growth pattern. The western and central regions – the main recipients of foreign investment – and Budapest area with its large positive agglomeration effects have grown faster than the rest of the country. The left-behind regions are characterised by low employment, a high number of social transfer recipients and poor integration into regional and national supply chains.

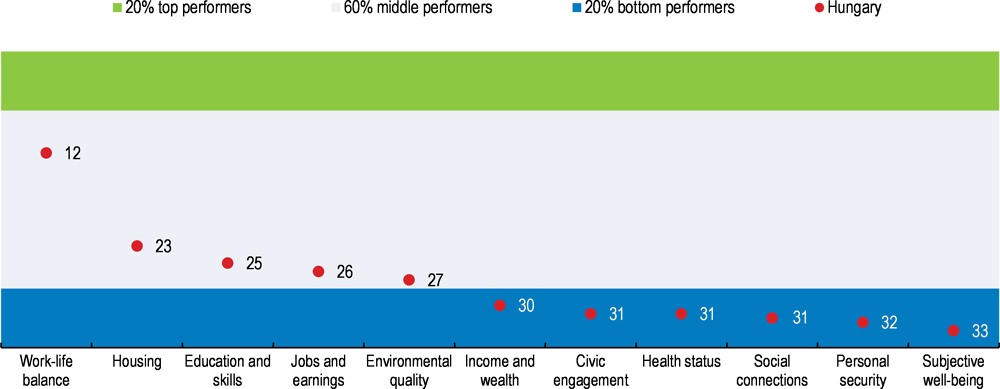

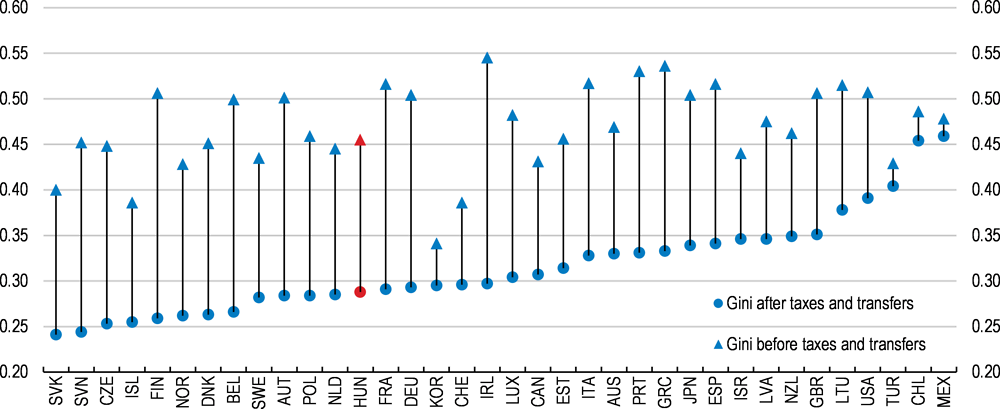

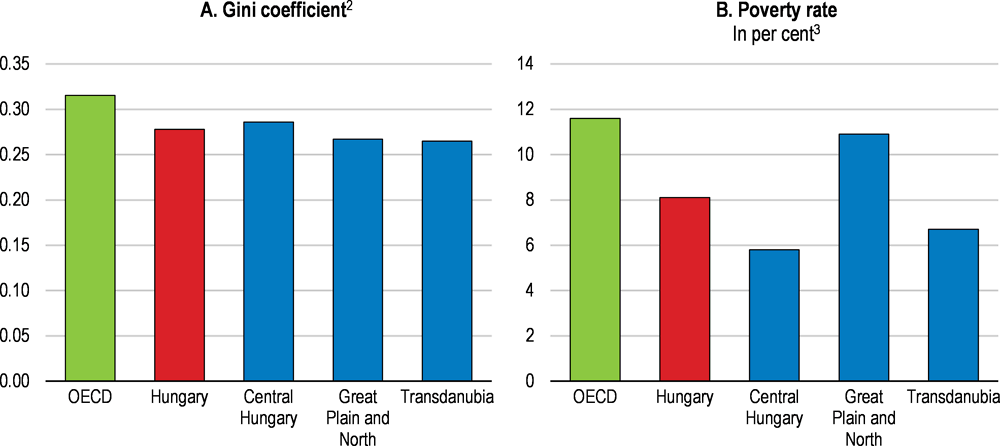

Long-term sustainability of growth requires an environment that creates opportunities for all. Hungary scores well in some aspects of well-being, particularly in work-life balance, but trails most other countries in other aspects, particularly health status (Figure 2). Another strength is that the tax-and-benefit system lowers inequality, although there is a strong regional element in poverty distribution (Figure 3). Looking ahead, enhancing well-being requires measures that improve incomes and health for the population and particularly for retirees and disadvantaged population groups. Higher incomes should come from high-productivity jobs and good wages as well as liveable pensions for all – a particular concern in view of the acceleration in population ageing.

Table 1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2005 prices).

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (HUF billion) |

||||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

32,592 |

2.2 |

4.4 |

4.6 |

3.9 |

3.3 |

|

Private consumption |

16,406 |

4.0 |

4.8 |

5.6 |

4.7 |

4.0 |

|

Government consumption |

6,505 |

0.7 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

7,223 |

-11.7 |

18.2 |

15.7 |

9.5 |

4.8 |

|

Housing |

631 |

9.7 |

16.0 |

10.3 |

9.1 |

3.9 |

|

Final domestic demand |

30,134 |

-0.6 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

5.2 |

3.6 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

377 |

1.4 |

-0.2 |

-1.6 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

30,511 |

0.8 |

6.7 |

5.2 |

4.9 |

3.6 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

28,568 |

5.1 |

4.7 |

8.3 |

7.5 |

5.9 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

26,487 |

3.9 |

7.7 |

9.6 |

8.8 |

6.3 |

|

Net exports1 |

2,081 |

1.4 |

-1.9 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.1 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

||||||

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

2.0 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

|

Output gap2 |

. . |

-1.9 |

0.3 |

2.2 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

|

Employment |

. . |

3.3 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

0.7 |

|

Unemployment rate |

. . |

5.1 |

4.2 |

3.6 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

1.0 |

3.6 |

4.5 |

4.9 |

4.3 |

|

Consumer price index |

. . |

0.4 |

2.3 |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|

Core consumer prices |

. . |

1.5 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

3.3 |

3.9 |

|

Household saving ratio, net3 |

. . |

8.1 |

7.3 |

10.8 |

10.6 |

10.8 |

|

Current account balance4 |

. . |

6.2 |

3.2 |

1.7 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

|

General government fiscal balance4 |

. . |

-1.6 |

-2.2 |

-2.4 |

-2.0 |

-2.0 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance2 |

. . |

-1.4 |

-2.3 |

-3.4 |

-3.4 |

-3.4 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance2 |

. . |

1.7 |

0.4 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.5 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht)4 |

. . |

75.9 |

73.3 |

70.6 |

67.7 |

65.7 |

|

General government net debt4 |

. . |

65.8 |

62.7 |

59.7 |

56.8 |

54.7 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

0.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

2.3 |

4.6 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

3.1 |

3.0 |

3.1 |

4.6 |

6.5 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. As a percentage of household disposable income.

4. As a percentage of GDP.

Source: OECD (2018), "OECD Economic Outlook No. 104, Volume 2018 Issue 2", OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

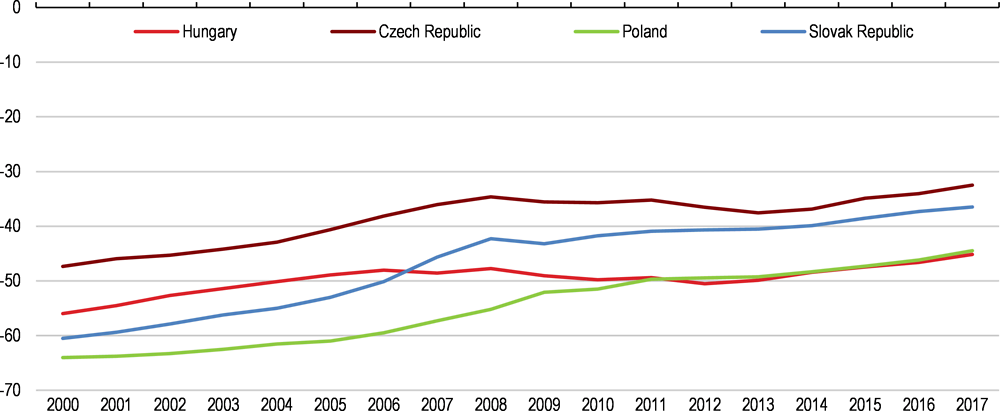

Figure 1. GDP per capita is converging to the OECD average, though slowly

GDP per capita gaps to the upper half of oecd countries. Upper half is weighted by the population.

Figure 2. Well-being can be improved

Better Life Index, country rankings from 1 (best) to 35 (worst), 2017¹

Note: Each well-being dimension is measured by one to four indicators from the OECD Better Life Index set. Normalised indicators are averaged with equal weights.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Better Life Index, www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org.

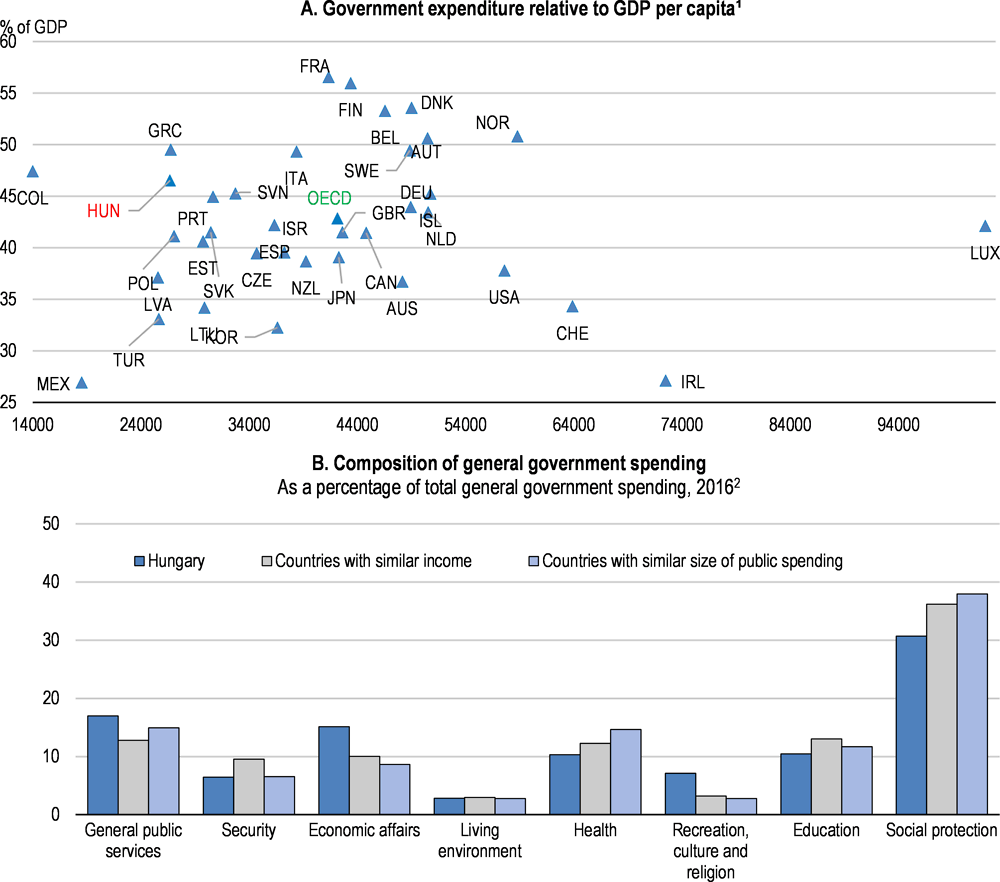

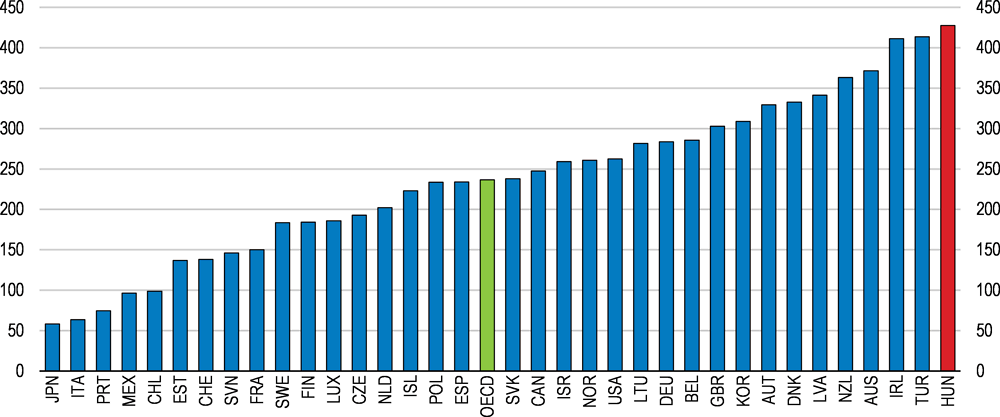

Figure 3. Redistribution reduces inequalities

Changes in the Gini coefficient due to taxation and transfers, 2016¹

1. 2015 for Chile, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Switzerland and Turkey. 2014 for Hungary, New Zealand and Mexico. The Gini coefficient has a range from zero (when everybody has identical incomes) to one (when all income goes to only one person). Increasing values of the Gini coefficient thus indicate higher inequality in the distribution of income.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Income Distribution Database.

Inequality has remained low, even with the sharp rise in unemployment during the crisis. Poverty is relatively low, but has a strong regional dimension (Figure 4). Poverty rates are higher in the northern and eastern part of the country, reflecting local economies that used to be reliant on out-dated mining and heavy industries. As economic activity disappeared, these regions were left with high shares of public transfer recipients, such as enrolees in public work schemes, disadvantaged groups (e.g. Roma) and low-income pensioners. Inequality is highest in Budapest, reflecting the creation of many high-income jobs in the service sectors. Nonetheless, even low-income earners in Budapest fare better than elsewhere in the country.

Figure 4. Inequality and poverty are relatively low but vary across regions

After taxation and transfers, 2013¹

1. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the latest data available for each country.

2. The Gini coefficient has a range from zero (when everybody has identical incomes) to one (when all income goes to only one person). Increasing values of the Gini coefficient thus indicate higher inequality in the distribution of income.

3. The poverty rate shows the share of the population with an income of less than 50% of the respective national median income. Income is adjusted for differences in household size.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Regional Well-Being Database; and OECD (2018), OECD Income Distribution Database.

Improving living conditions requires not only that production continues to move up the value chain, but also that local comparative advantages are better exploited and that left-behind regions have better linkages to the rest of the economy, which would add to productivity growth. In addition, improving the skills of the labour force is key to enable growth. Presently, there is a need to respond to emerging and widening labour shortages, which would benefit from higher female labour participation and better integration of job seekers. This is also important for preparing for the impact of an ageing population. The key messages of this Economic Survey are:

The economy is expanding rapidly, and macroeconomic policies need to be gradually tightened to prevent overheating and stem rising inflation.

Population ageing will eventually put pressure on public finances, particularly on pension and health spending. Policies should be devised and implemented early to head off these pressures.

Better mobilising labour and improving skills in poor regions, together with better links with regional and national supply chains, are the key to long-term sustainable growth in living standards.

Recent macroeconomic developments and short-term prospects

The economic recovery is maturing

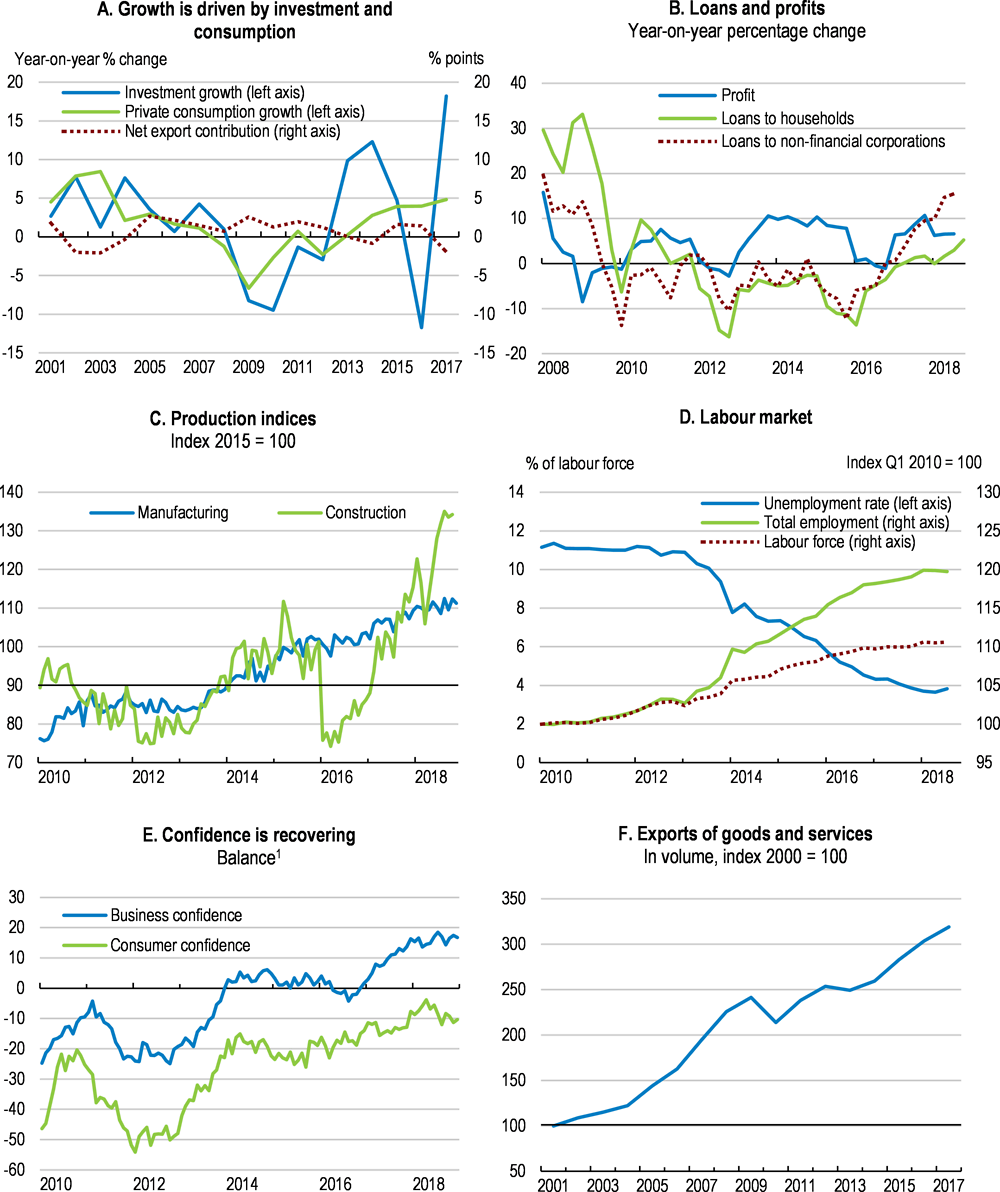

Growth is increasingly being driven by private consumption, which is underpinned by expanding real incomes, reflecting strong real-wage and employment growth, high consumer confidence and supportive macroeconomic policy stances (Figure 5). In 2017, investment rebounded strongly, partly reflecting the start of a new funding cycle for EU structural funds. Higher housing investment reflects rising incomes, low interest rates and government subsidies, including for families with three or more children (Ministry for the National Economy, 2018a).

Business investment is supported by favourable monetary conditions and high profits, driven by the ongoing recovery in manufacturing production that requires capacity expansion as well as a higher reliance on capital in production in reaction to the tight labour market (Hungarian Central Bank, 2018) (Figure 5, Panel B and C). Most of the business investment is taking place in large and, increasingly, in foreign-owned export-oriented firms, particularly in the automotive sector (Endresz and Bauer, 2017, p. 14) (Palócz et al., 2016) (OECD, 2017). However, all of manufacturing has benefited from the investment upswing.

Hungarian-owned firms, which are mostly SMEs, seem to have increased their investment less, judging from the relatively slow expansion of bank credit to the corporate sector, though it picked up more recently (see below) (Palócz et al., 2016). The government has a number of investment support programmes in place for SMEs, including the Supplier Development Programme (Ministry for the National Economy, 2018a).

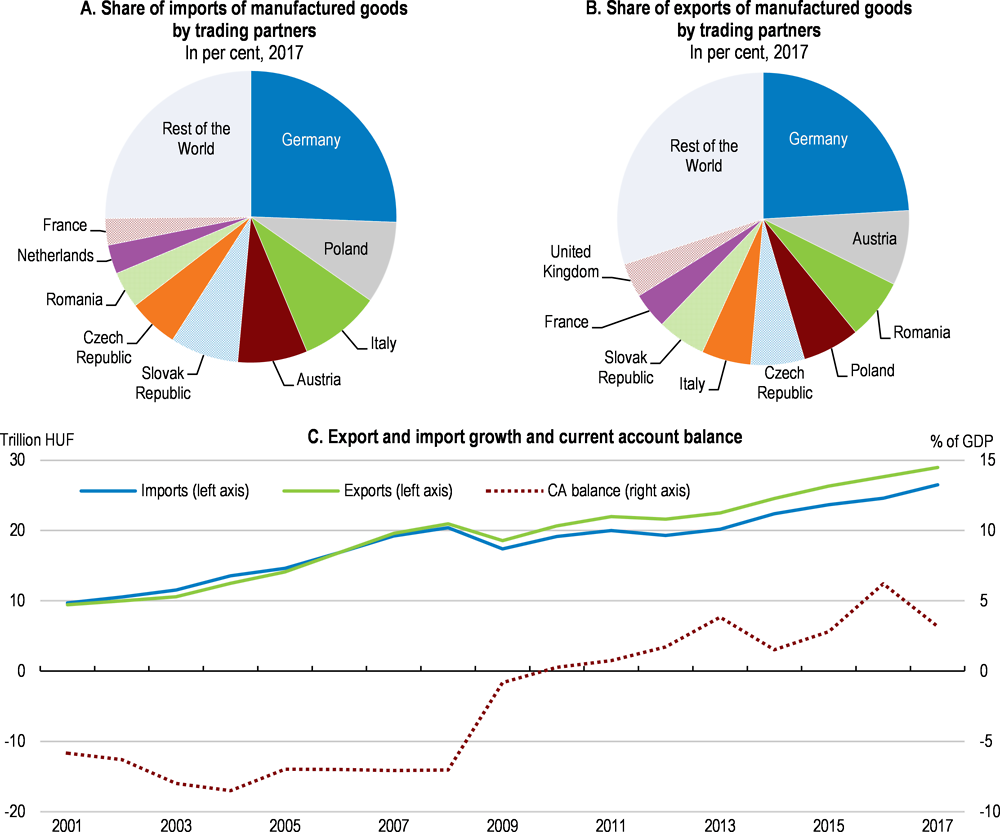

In 2017, exports accelerated as activity in Hungary’s trading partners picked up and as new production capacity in export-oriented firms, particularly in the car, and, to a lesser extent, chemical industry, came into operation (Figure 5, Panel F; Figure 6, Panels A and B). This development has further skewed exports towards transport equipment and machinery (56% of exports by value in 2017) and chemical products (12% of exports by value in 2017). Imports rose even faster in 2017, reflecting the high import-content in exports and strong growth in domestic consumption, narrowing the current account surplus.

Figure 5. Economic developments are strong

1. Business confidence is calculated as an unweighted average confidence indicators for manufacturing, construction, retail trade and services excluding retail trade.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); OECD (2018), OECD Main Economic Indicators (database); and Thomson Reuters.

Figure 6. Trade is mainly with Europe

Source: OECD (2018), OECD International Trade by Commodity Statistics (database); OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and OECD (2018), OECD Resilience Database.

Labour market shortages are emerging and widening

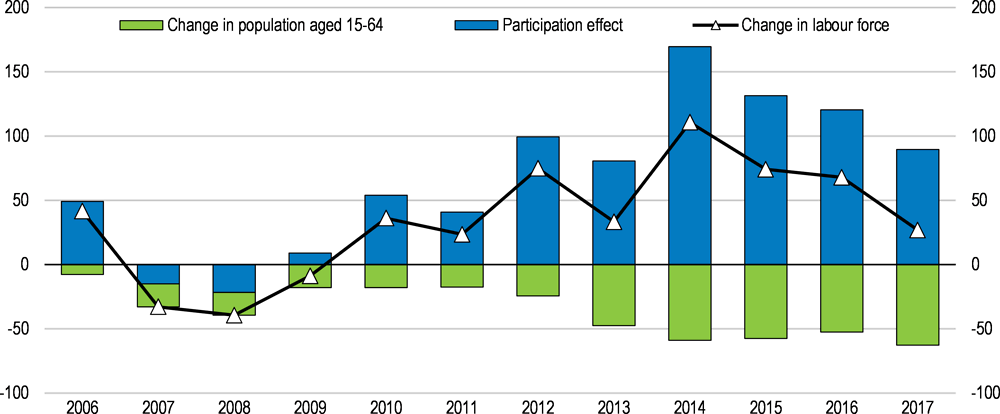

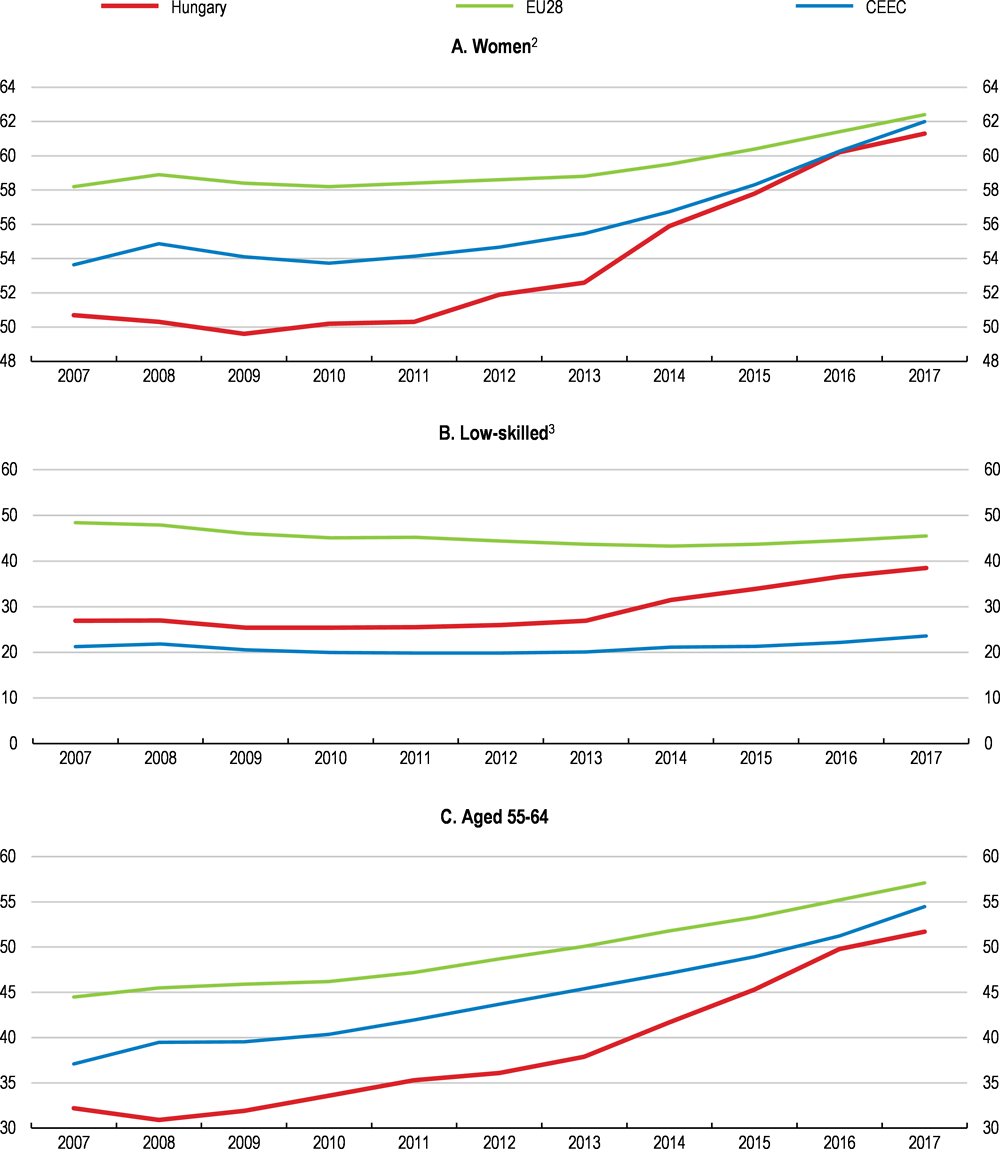

In 2017, total employment creation slowed, reflecting strong private sector employment creation and a decline in public employment Figure 5, Panel D). Moreover, the number of enrolees in public work schemes fell to just below 150 000, aided by increased search incentives for enrolees as the ratio of their (non-indexed) wages to the rising minimum wage was reduced from 77% to 59% between 2012 and 2018. The improved labour market situation has also benefited groups with weak attachments (including females, older and low-skilled workers and long-term job seekers) partly helped by the extensive use of public work schemes, vocational training subsidies and lower social security contributions (Figure 7) (OECD, 2016), (Ministry for the National Economy, 2018). Labour supply has increased as the positive effects of improved labour market prospects offset the ageing-related shrinking of the working-age population (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Employment rates of women, the low-skilled and older workers have risen

In per cent¹

1. Central and Eastern European countries (CEEC) include the Czech Republic, Poland and the Slovak Republic.

2. Data refer to the population aged 15-64.

3. Low skilled refer to those with less than primary, primary and lower secondary education (ISCED levels 0‑2). Data refer to the population aged 15-64.

Source: Eurostat (2018), "LFS series - detailed annual survey results", Eurostat Database.

Figure 8. Higher participation is helping to offset the effect of ageing in the labour market

Change in 1 000 persons

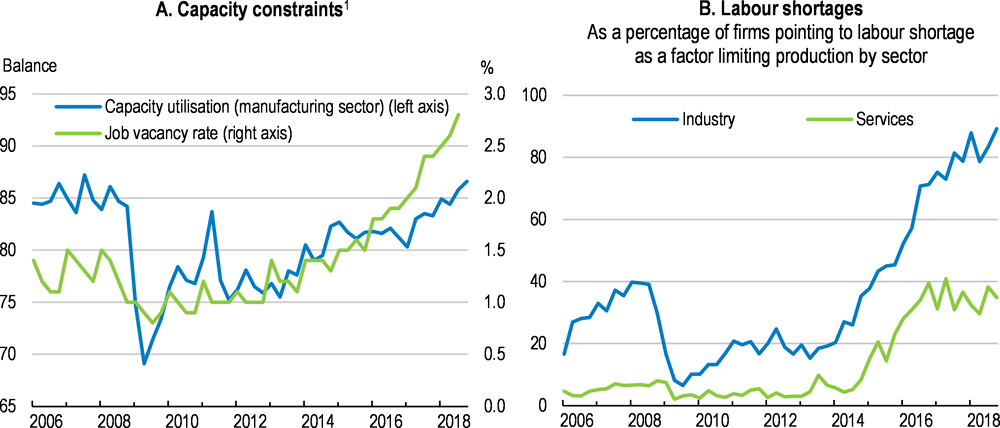

The labour market has been tightening significantly, as indicated by the historically low unemployment rate, the increasing number of firms having problems in hiring qualified workers and the more-than-doubling of the job vacancy rate since 2010 (PwC, 2018). Migration of skilled workers and increasing number of cross-border commuters are contributing to the labour market shortages. In addition, capacity utilisation has been rising since 2012 (Figure 9) (Eurostat, 2018a).

Figure 9. Capacity constraints are increasing

1. Job vacancy rate refers to the sum of the number of occupied posts and the number of job vacancies.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Main Economic Indicators (database); Eurostat (2018), "Job vacancy rate", Eurostat Database; and Eurostat (2018), "Business and consumer surveys", Eurostat Database.

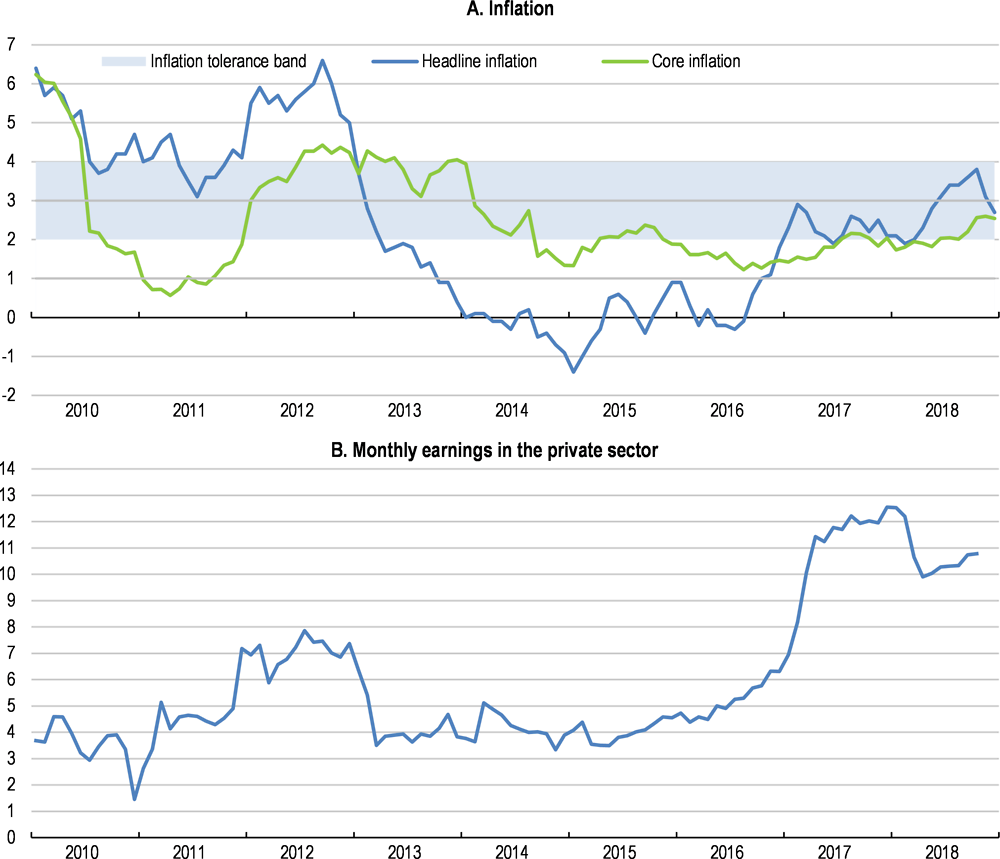

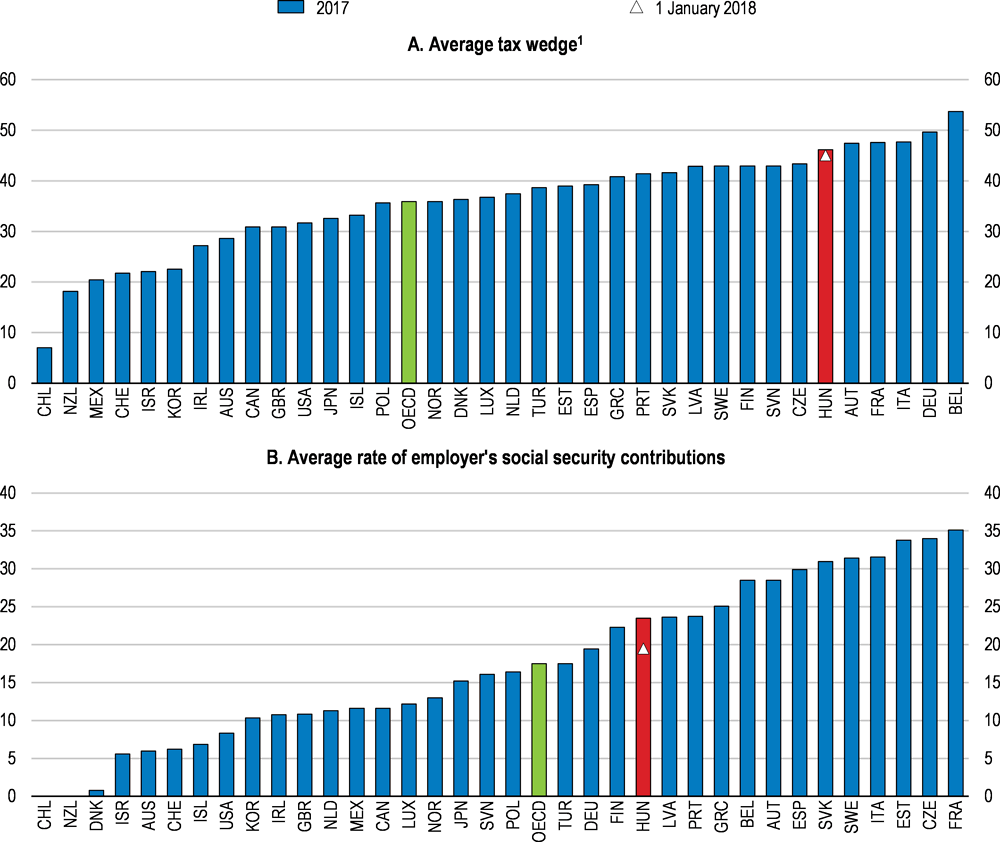

The tightening labour market has led to higher wage growth, which exceeded 10% in both 2017 and 2018 on the back of stronger underlying wage dynamics and higher minimum wages (Figure 10, panel B). A 2016 tripartite 6-year wage-agreement raised minimum wages by 15% and 25% in 2017 and by half as much in 2018. Further increases are planned for 2019-22 subject to annual reviews by the Permanent Consultation Forum of the government and social partners. These reviews should assess whether additional minimum wage increases will harm external competitiveness and employment. Employers were compensated by a cut of more than one-quarter (accumulated over 2016-2018) in their social security contribution rates to19.5% (Figure 11). Further reductions to 11.5% in 2022 are conditioned on continued wage increases, but the 2019 budget contains a 2 percentage points cut to be implemented in July (Ministry for the National Economy, 2018a).

Figure 10. Inflation is picking up

Year-on-year percentage change¹

1. Core inflation excludes energy and food. Three-month moving average for monthly earnings in the private sector.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Main Economic Indicators (database).

Figure 11. The tax wedge is being reduced

For a single person with average earnings, as a percentage of gross wages

1. The tax wedge is the sum of personal income tax and employee plus employer social security contributions together with any payroll tax less cash transfers, expressed as a percentage of labour costs for a single person (without children) on average earnings. The 1 January 2018 observation reflects only Hungarian measures.

Source: OECD (2018), "Taxing Wages: Comparative tables", OECD Tax Statistics (database).

Headline inflation has picked up and passed the central bank’s target of 3% (with a tolerance band of +/-1%) by mid-2018 and reached 3.8% in the autumn before coming down below 3% as one-off effects disappeared, reflecting that most of the increase had been driven by higher food and energy prices (Figure 10, panel A). Core inflation (excluding energy and food) has started increasing, before stabilising around 2 ½% in the autumn. Nonetheless, surveys from spring 2018 indicated low inflation expectations at that point in time (Central Bank of Hungary, 2018a). More recent EU surveys confirm this pattern into the summer, before household inflation expectations started to edge up.

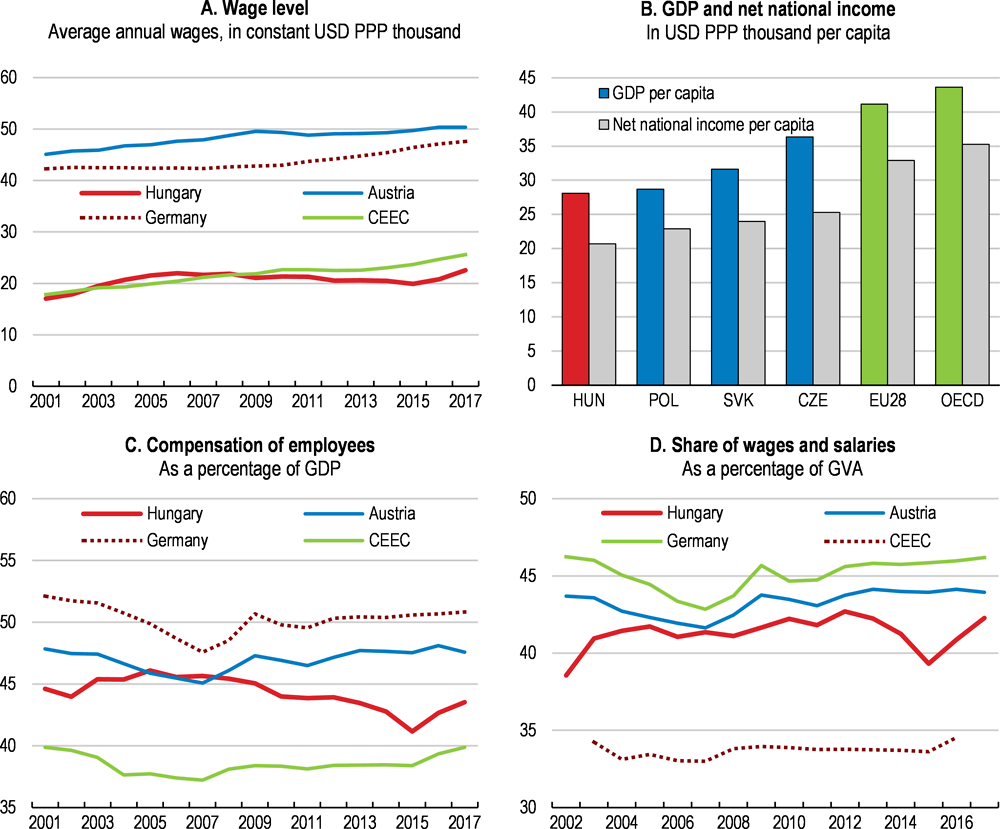

Since 2015, labour productivity growth has been well below real wage growth, leading to higher unit labour costs. The associated increase in the wage share has been larger than in other CEEC countries (Figure 12). The share remains lower than in the 2010s. However, if wage growth continues to outpace productivity growth in the same manner, then the wage share will be higher than at the peak of the previous cycle, while contributing to higher unit labour costs. Wage competitiveness is not yet a risk factor, but continued rising wages could put pressure on external competitiveness in the near future. Such a development could discourage inwards FDI. On the other hand, rising wages are also an integral part of incomes catching up towards richer OECD countries. Moreover, higher wages could stem emigration of high-skilled workers and attract skilled labour. This would support a shift to higher productivity activities, increasing the attractiveness for foreign investors and furthering growth.

Figure 12. Wage levels remain low in Hungary despite recent increases

Note: Central and Eastern European countries (CEEC) include the Czech Republic, Poland and the Slovak Republic.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database); OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and OECD (2018), OECD National Accounts Statistics (database).

Bolstering productivity growth has to address the dichotomy between the mainly foreign-owned, export-oriented and innovative firms with strong growth and profits, and the domestic SME sector with low productivity growth, little technological spill-over and a low propensity to innovate (European Commission Staff Working Document, 2018). This requires more competition on domestic markets to foster competitive firms, pointing to a need for reduced regulatory barriers and improved regulatory policy formulation as discussed in the previous Survey (OECD, 2016a) (Bania et al., 2017). More competitive firms would also have stronger investment incentives, but human capital also needs to be enhanced, especially in skills upgrading and on-the-job training of workers (OECD, 2016a).

Prospects and risks

Economic activity remained strong in 2018 but will moderate in 2019 as capacity constraints tighten further. This means that demand will increasingly be met through imports and inflation will continue to rise. Private consumption will progressively drive growth, as real incomes continue to expand and household savings fall. Public investment is set to gradually slow as the EU funding cycle matures. Business investment will continue to respond to the need for expanding production capacity. Exports will be supported by external demand and new industrial capacity, but rising costs will slow gains in export market shares. The pace of import growth is driven by domestic demand and will continue to exceed that of exports, further reducing the current account surplus.

An escalation of international trade disputes could cut demand for Hungary’s exports, and undermine investor confidence. Faster-than-expected wage increases could spill over into prices and unhinge inflation expectations, requiring an abrupt change in policy stances, which would exaggerate the boom-bust business cycle pattern. If productivity growth fails to catch up to the increases in real wages, then external competitiveness would be eroded, reducing export growth and Hungary’s attractiveness to inward FDI. On the other hand, stronger-than-expected productivity gains would bolster the capability to absorb rapid wage gains and secure faster income convergence.

Besides these risks, the economy is exposed to some potential vulnerabilities, which have low probabilities but have large impacts on the economy. These include renewed turbulence in international financial market that would reduce banks' willingness to lend, hurting investments and other events (Table 2).

Table 2. Potential vulnerabilities of the Hungarian economy

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

A sharp increase in geopolitical tensions, particularly in Europe. |

Such tensions would lead to investors seeking refuge in safe harbours, potentially precipitating currency outflows from Hungary owing to interest-rate differentials and recent currency fluctuations, with knock-on effects on inward private sector investment. |

|

Emerging market economies turbulence spreading to Hungary |

A sharp currency depreciation could force an abrupt and large increase in monetary policy rates, resulting in a confidence crisis that suppress growth |

|

A sharp reduction of EU funding of structural Programmes in the next funding period starting in 2021. |

A deterioration in funding would severely hamper implementation of the government’s development strategies. |

Monetary, financial and fiscal policies to promote stability and well-being

Monetary policy is supportive

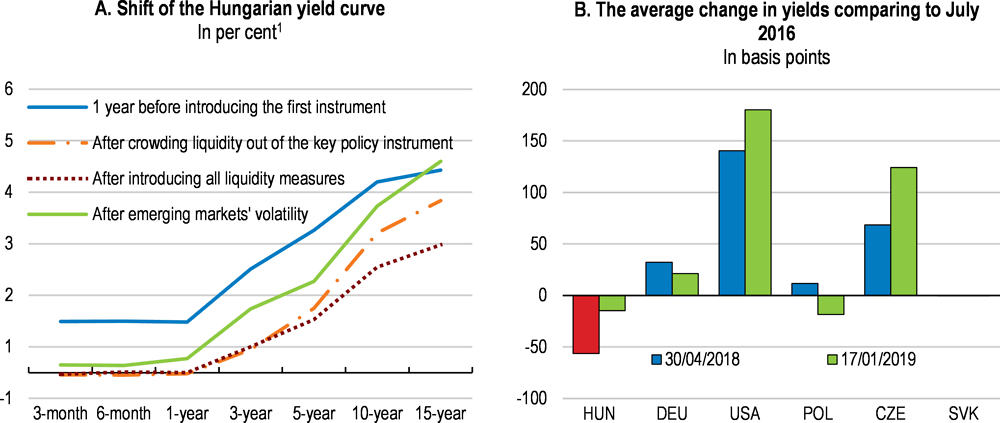

Policy interest rates have been unchanged since September 2017 when the overnight central bank deposit rate was cut to -0.15% and the base rate was kept unchanged at 0.9% (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2017a). In addition, the central bank used unconventional measures to lower the yield curve, although with limited impact for longer maturities (Figure 13) (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2017a) (Virág and Nagy, 2016).

Figure 13. The yield curve has steepened

1. Exact dates: 1 year before introducing the first instrument: 20-09-2015; After crowding out liquidity of the key policy instrument: 20-09-2017; After introducing all liquidity measures: 18-01-2018; After emerging market's volatility: 11-06-2018.

Source: Thomson Reuters.

In September 2018, the central bank announced that it is prepared for a gradual and cautious normalisation of monetary policy, while maintaining policy rates. As a first step, some of the unconventional monetary policy tools – including a three-month deposit facility, a mortgage-bond purchase programme and an interest rate swap facility – will be phased out by end-2018. During the phasing out period, a Funding for Growth Scheme Fix will be introduced to encourage commercial banks to provide fixed-term loans to SMEs following similar programmes in the past (Central Bank of Hungary, 2018b) (Central Bank of Hungary, 2018c) (Central Bank of Hungary, 2018d).

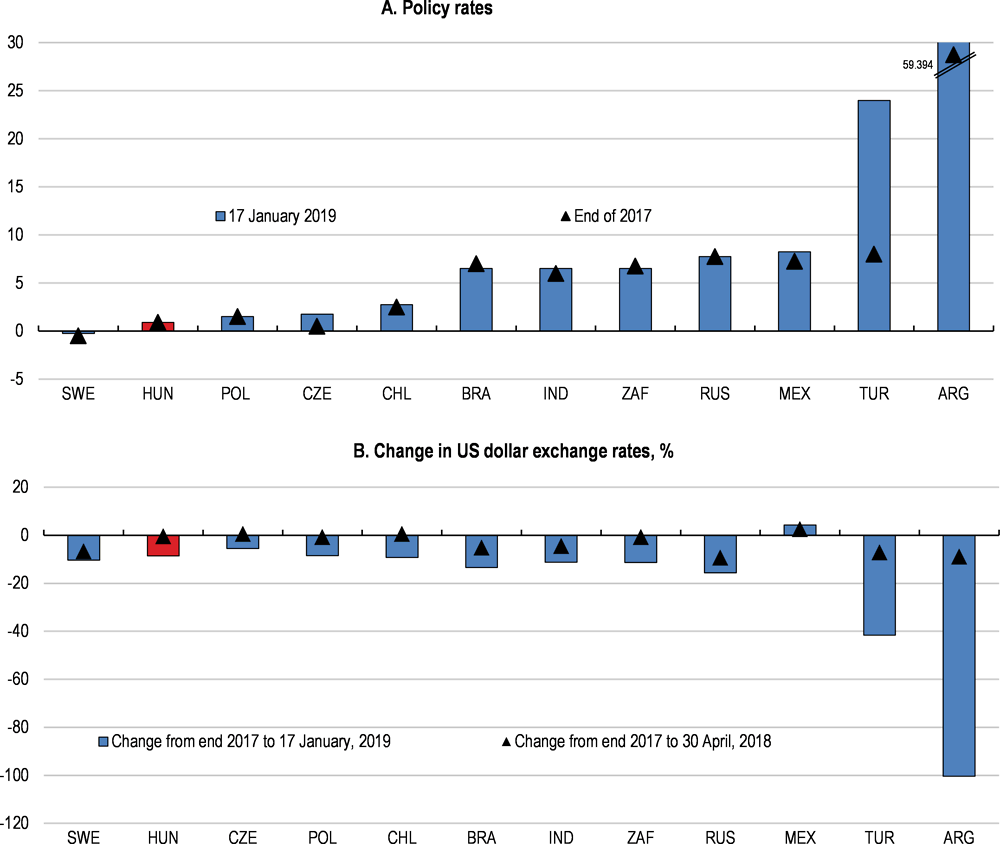

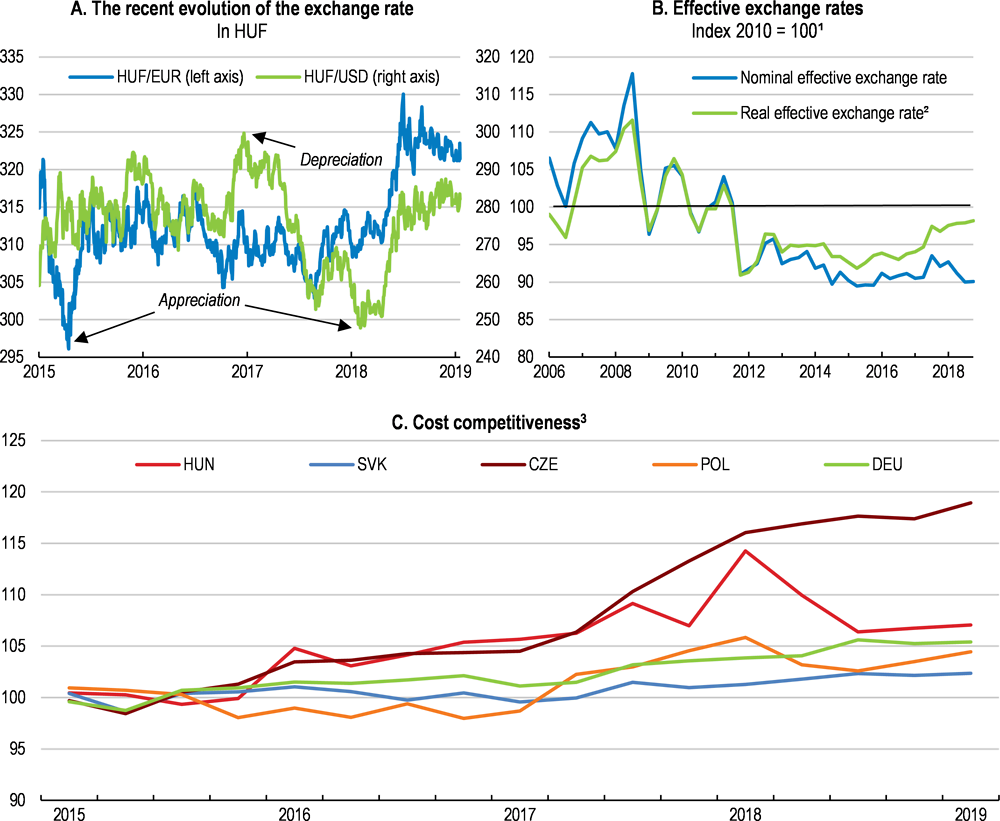

The currency has fluctuated. In 2017, the currency appreciated against the euro and the US dollar, despite a widening interest-rate differential. In 2018, increasing volatility in emerging markets led to a sharp depreciation and higher yields more than reversing the previous appreciation (Figure 14, Panel A and B). This development addresses some of the concern that the currency may be somewhat overvalued (IMF, 2018). The currency depreciation also mitigated some of the increases in unit labour costs brought about by strong real-wage growth (Figure 14, Panel C). However, other economies with floating exchange rates have been forced to hike policy rates in response to large depreciations to stem capital outflows, irrespective of the fundamental value of their currency (Figure 15). Moreover, as real interest rates remain negative, in a context of rising global interest rates Hungary may be vulnerable to currency outflows as investors seek better yields.

Figure 14. Emerging market volatility has spilled into the Hungarian markets

1. At constant trade weights.

2. Real effective exchange rates take account of price level differences between trading partners. Movements in real effective exchange rates provide an indication of the evolution of a country’s aggregate external price competitiveness.

3. A rise in the indices represents a deterioration in that country's competitiveness. Real exchange rates are a major short-run determinant of any country's capacity to compete. Note that the indices only show changes in the international competitiveness of each country over time.

Source: Thomson Reuters; and OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

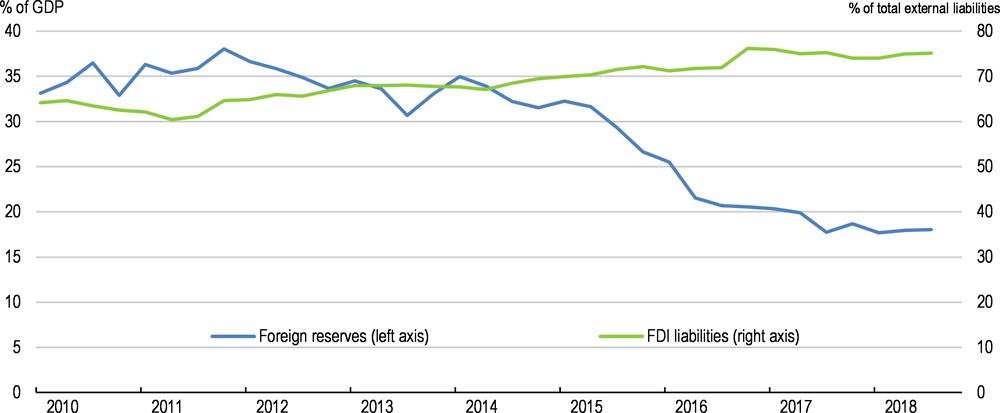

International reserves have declined by one-third between 2014 and 2017, mainly reflecting the conversion of households’ foreign currency mortgages to domestic denominations. This also reduced the import cover rate below three months (Figure 16) (IMF, 2018). At present, this in itself does not give rise to concern and the latest IMF Article IV consultation concluded that foreign reserves remain adequate.

The currency depreciation has contributed to higher inflation, though less than other factors such as higher commodity prices and excise duties. The fast wage increases combined with rising inflation are likely to have contributed to the increase in inflation expectations since mid-2018. This calls for a normalisation of monetary policy to ensure that inflation expectations remains well anchored, including a gradual increase in policy rates and the continued exiting from unconventional monetary policy measures. The authorities may need to resort to earlier and much more substantial tightening if the depreciation continues under the influence of international financial disturbances affecting emerging markets economies, or if there is a faster-than-expected normalisation of international monetary conditions.

Figure 15. Some central banks have been forced to sharply increase policy rates

Figure 16. Foreign reserves are declining

Financial sector vulnerability could be further reduced

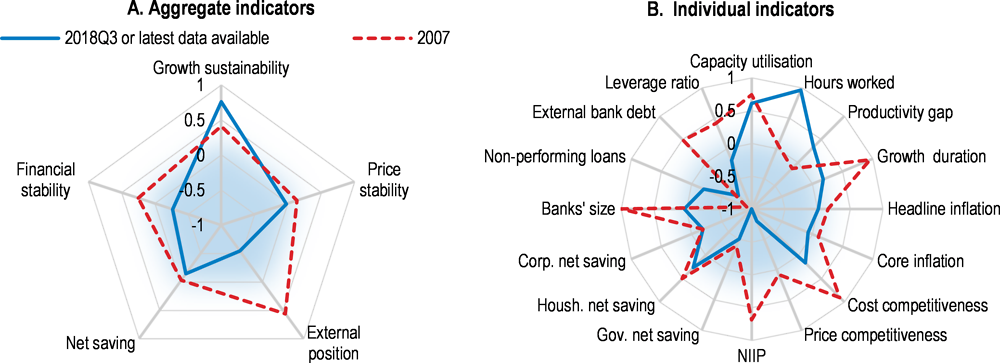

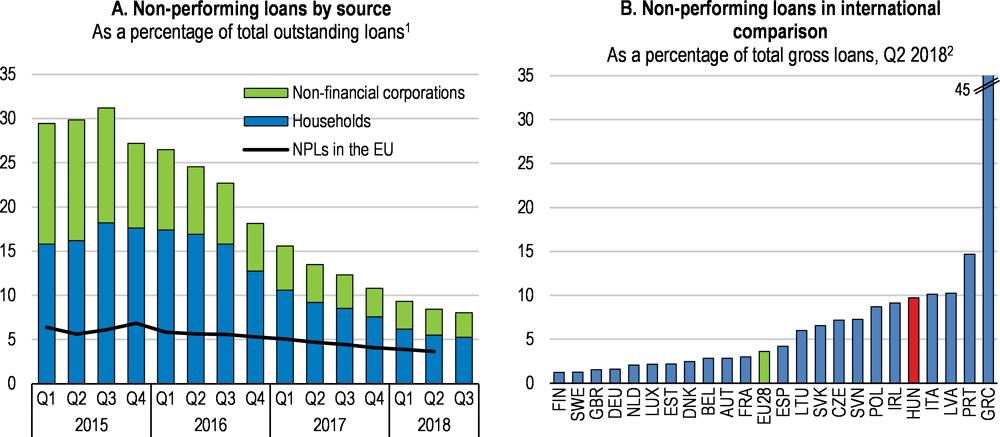

Since 2015, the stability of the financial sector has improved markedly (Figure 17). Banks’ capital adequacy ratio is around 20% which – while improved – implies lower capital buffers than Hungary’s regional peers (IMF, 2018). The banking liquidity coverage ratio is 189%, providing banks with adequate shock absorbing capacity in line with Basel and national regulatory requirements (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018a). Other indicators also point to good health. Return on assets (ROA) and equity (ROE) were around 1.5% and 14% respectively by mid-summer 2018, close to historical highs, reflecting solid profitability on the back of historically high profits; although much of the profitability is concentrated in the largest banking groups (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018a). In addition, banks have continued to reduce their share of non-performing loans (NPLs). However, the level remains relatively high (Figure 18). The main problem resides with the household sector, which accounts for almost three-quarters of NPLs (90 days delinquency), while the share of corporate NPLs is considered to be in line with normal risks for such loans (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018b).

Further reduction in NPLs is facilitated by the strong economy, but may be hampered by a lack of an official trading platform and a framework for selling impaired loans. After fewer than three years of operation, the central bank sold the Hungarian Restructuring and Debt Management Ltd. (MARK), created to absorb bad debts to a private investor in early 2017 (OECD, 2016a) (APS Investment, 2017). MARK had an initial positive effect. Nonetheless, the sale runs somewhat against current European Union reform efforts to develop, among others, a secondary market for NPLs and prevent future NPL build-ups (OECD, 2018a). The central bank has introduced macro-prudential tools (including a Systemic Risk Buffer) to discourage holding NPLs, which may support the secondary market for NPLs. The Systemic Risk Buffer accelerates portfolio cleaning as it levies capital surcharges on banks that keep their non-performing loans beyond a certain duration or threshold as recommended in the last Survey (Table 3) (OECD, 2016a).

Figure 17. Macro-financial vulnerabilities have diminished significantly since 2007

Deviations of indicators from their real time long-term averages (0), with +1 representing the greatest vulnerability and -1 (the centre point) the least

Note: Each aggregate macro-financial vulnerability indicator is calculated by aggregating (simple average) normalised individual indicators. Growth sustainability includes: capacity utilisation of the manufacturing sector, total hours worked as a proportion of the working-age population (hours worked), difference between GDP growth and productivity growth (productivity gap), and an indicator combining the length and strength of expansion from the previous trough (growth duration). Price stability includes: headline and core inflation. External position includes: the average of unit labour cost (ULC) based real effective exchange rate (REER), and consumer price (CPI) based REER (cost competitiveness), relative prices of exported goods and services (price competitiveness) and net international investment position (NIIP). Net saving includes: government, household and corporate net saving. Financial stability includes: banks' size as a percentage of GDP, share of more than 1 year overdue loans of households (non-performing loans), external bank debt as percentage of total banks’ liabilities, and capital and reserves as a proportion of total liabilities (leverage ratio). Due to data availability data for non-performing loans refer to 2009 instead of 2007 and the deviation from long-term average is not calculated in real time.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2015), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) and Datastream.

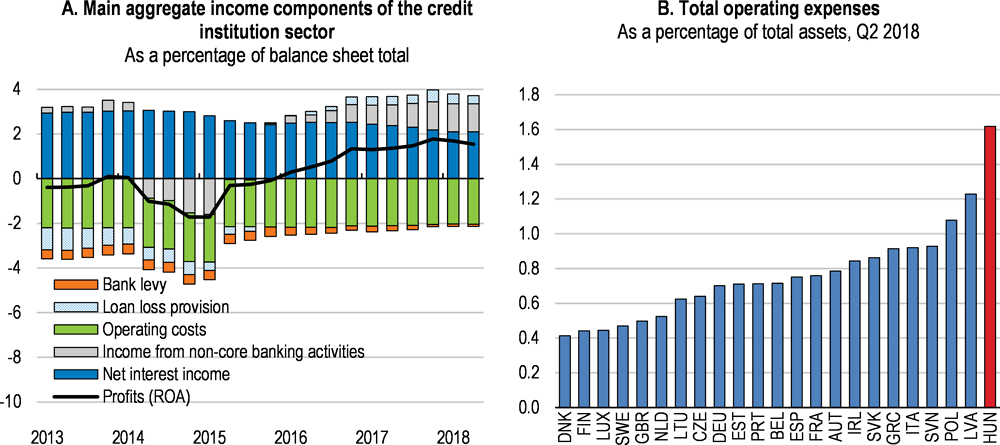

Another part of the European Union’s reform efforts is the continued restructuring of the banking sector. A sign of insufficient restructuring is that although the profitability of the banking sector has continued to improve, this has mainly arisen from non-core activities, such as trading, dividend incomes etc. (Figure 19) (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018b). Without profits from non-core activities, a number of credit institutions (with a combined market share of 20%) would be loss-makers. More generally, the sector has the highest operating and staffing costs in the CEEC region, reflecting a combination of high concentration and a low degree of competition (Figure 19, Panel B) (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018a) (IMF, 2018) (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2017c). The government could spur competition in the sector through privatisation of the remaining state-owned banks to help foster the financial sector’s ability to contribute to growth.

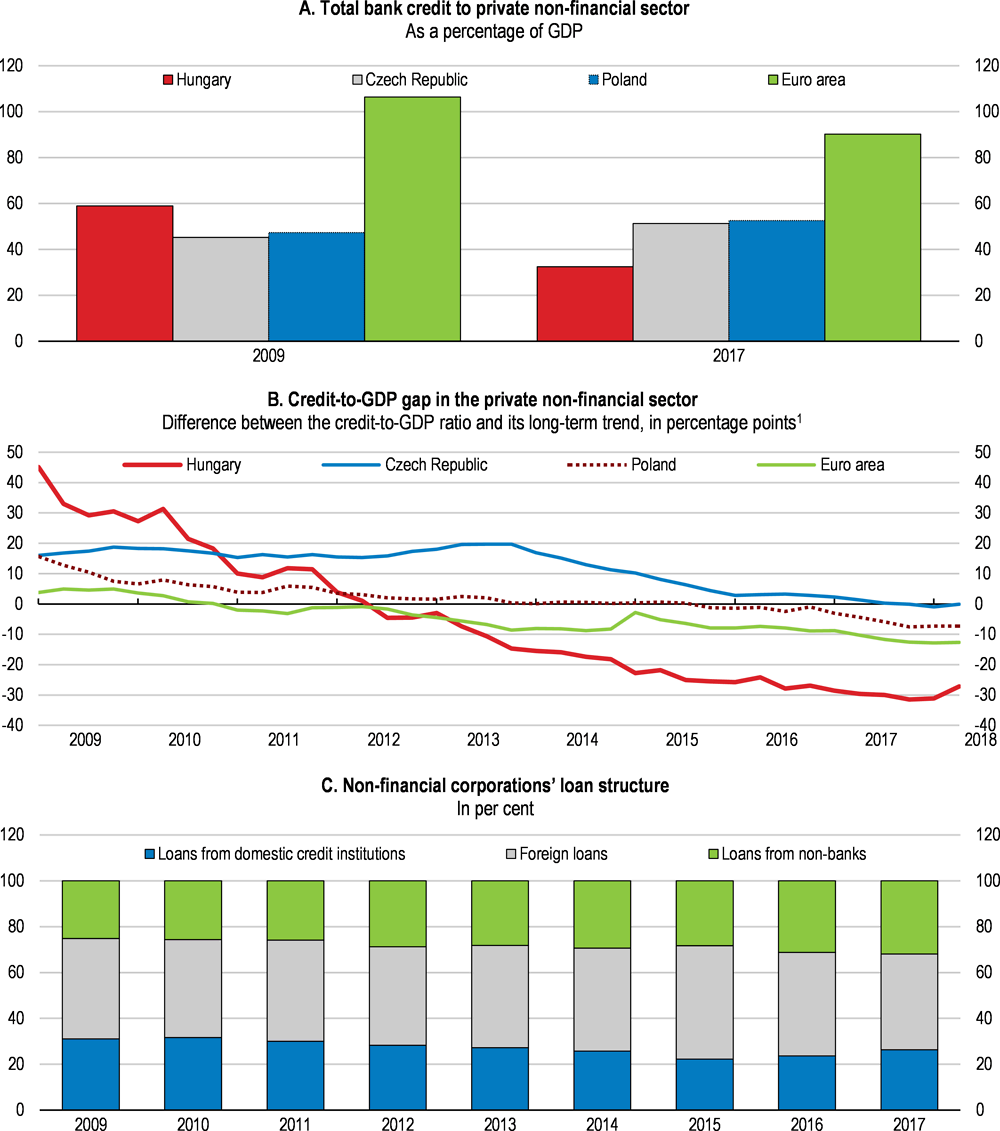

Despite the improved health of banks, they only started extending credit again in 2017, and the volume of total credit remains below pre-crises levels (Figure 20, Panel A). Demand for mortgage loans has been stimulated by government measures (the Family Housing Subsidy Programme) as well as central bank measures, including a consumer-friendly housing loan programme and the promotion of fixed interest loans. Nonetheless, the household credit-to-GDP level remains lower than in peer countries (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018a). Some of the unconventional monetary policy measures are aimed at supporting credit extension to the corporate sector and particularly SMEs (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018c) (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2017d). In June 2018, the overall loan volume to the corporate sector was 12% higher y-o-y. Nonetheless, corporate loans as a share of GDP has remained basically unchanged (Figure 20, Panel C).

Figure 18. The ratio of non-performing loans has fallen

1. Non-performing loans refer to loans with more than 90 days delinquency.

2. Data refer to domestic banking groups and stand-alone banks.

Source: MNB (2018), "XI. Money and capital markets", Statistics, Magyar Nemzeti Bank; and ECB (2018), "Consolidated Banking data", Statistical Data Warehouse, European Central Bank.

Figure 19. Low banking sector efficiency is a concern

Source: MNB (2018), "Financial Stability Report", Magyar Nemzeti Bank, May; and ECB (2019), "Consolidated Banking data", Statistical Data Warehouse, European Central Bank.

Arguably, the banking sector could extend credit further. Deposits have grown faster than credits and lending is lagging economic growth, suggesting a nearly neutral impact on growth (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018a) (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018c). Moreover, the gap between the credit-to-GDP ratio and its long-run trend indicates room for stronger credit expansion Figure 20, Panel B). This suggests that the withdrawal of all unconventional monetary policy measures together with a more competitive and risk-bearing banking sector would allow the sector to resume its traditional credit role.

Figure 20. The stock of credit is relatively low

1. Credit-to-GDP gap is based on total credit to the private non-financial sector as a percentage of GDP.

Source: BIS (2018), "Credit to the non‑financial sector", BIS Statistics Explorer, Bank of International Settlements; and MNB (2018), "XII. Financial accounts (financial assets and liabilities of institutional sectors)", Magyar Nemzeti Bank.

Table 3. Past recommendations on monetary policy and financial sector

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Reduce tax burdens of banks and improve tax design. |

In January 2017, the levy on larger banks has been reduced from 0.24% to 0.21% of assets, although the tax on small banks, of 0.15% of assets, remained unchanged. Since 2017, banks are eligible for transaction duty reduction if their number of clients from financial services increases. |

|

Consider moving towards to a more neutral policy stance. |

In September 2017, the central bank has lowered the overnight central bank deposit rate from -0.05 to -0.15% and kept the base rate unchanged at 0.9%. |

|

Expand capital surcharges on nonperforming loans detained by banks beyond a certain period. |

Since 2017, banks have to comply with enhanced capital requirements, if their stock of impaired project financing loans exceeds 30% of domestic Pillar 1 capital requirement. |

|

Implement a strategy for the asset management company to step-up offloading of non-performing assets. |

In early 2017 the Hungarian Restructuring and Debt Management Ltd. (MARK Zrt.) was sold to a private investor, removing an official trading platform for impaired loans. |

|

The ownership of the stock exchange should return to private ownership over the medium-term. |

No action taken. |

Fiscal policy should be more forward looking

Fiscal policy is being loosened. On the revenue side, employers' social security contribution rate was lowered in 2017 and again it 2018 to 19.5% (from 27%), as recommended in the previous Survey. The corporate income tax rate was also lowered to 9% in 2017. The total revenue reductions are 1.8% of GDP in 2017 and 0.7% of GDP in 2018, constituting a permanent reduction in the revenue-to-GDP share, (European Commission, 2018a) (Ministry for the National Economy, 2018). Additional minor revenue losses, amounting to 0.2% of GDP in 2017 and 0.1% in 2018, came from the lowering of the VAT rate on selected products (European Commission, 2018a). The government’s main objective for this lowering was to combat VAT fraud. By contrast, the previous Survey recommended increasing the reliance on consumption taxes (Table 6). Moreover, these changes have added to a complex and administratively costly VAT system. This contributes to a persistent, albeit narrowing, VAT gap (the difference between expected and collected VAT receipts) which stood at 13% in 2016, the most recent figure available (European Union, 2018). Other smaller tax measures had an estimated budgetary cost of 0.1% of GDP in both 2017 and 2018 (European Commission, 2018a). The 2019 budget contains additional tax reductions for families with at least two children; another 2 percentage point reduction in employers' social contribution rate, and tax relief for small businesses, subtracting another 0.4% of GDP from revenue.

Public spending has been expanding since 2017, reflecting renewed disbursements from EU structural funds and an increase in housing subsidies (with a budget cost of 0.1% of GDP) (European Commission, 2018a). Moreover, in 2018 public wages were increased by between 5% and 18% as part of the agreed 30% cumulated public wage increases for the years 2017 to 2019, adding 0.4% of GDP to the public wage bill (Ministry for the National Economy, 2018b) (European Commission, 2018a). On the other hand, the lower social security contributions reduced the wage bill by an estimated 0.2% of GDP. The 2019 budget contains higher spending on security, education, unemployment benefits, and on transport and telecommunications infrastructure and services. Nationally funded investment projects will add 0.7% of GDP to spending in 2019 (European Commission, 2018a).

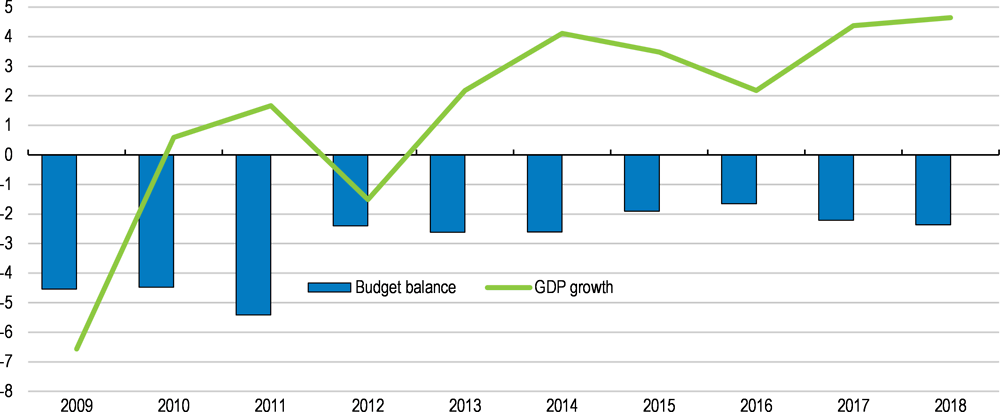

Overall, the general government budget deficit will have widened to an estimated 2.4% of GDP in 2018 before slightly narrowing in 2019, reflecting the fact that the budgetary effect of a looser fiscal stance is broadly offset by strong economic growth, leaving the revenue and spending broadly stable as a share of GDP (Table 4). The implied deterioration in the structural deficit mainly reflects the tax reductions (Figure 21). These have mostly focused on reducing taxation on labour and corporate income with positive employment and growth effects in the medium term, while the short-term implication is a continuation of a pro-cyclical fiscal stance (OECD, 2011). Given the risks of an overheating economy, the government should tighten the fiscal stance for cyclical reasons to avoid overheating and thus prolong the economic upswing. Fiscal policy should avoid excessive pro-cyclicality in order to build up sufficient buffers to meet medium-term challenges.

Table 4. Fiscal indicators

As a percentage of GDP.

|

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 ¹ |

2020 ¹ |

|

Spending and revenue |

|||||

|

Total revenue |

45.1 |

44.7 |

44.3 |

44.3 |

44.2 |

|

Total expenditure |

46.8 |

46.9 |

46.6 |

46.5 |

46.3 |

|

Net interest payments |

3.1 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

|

Budget balance |

|||||

|

Fiscal balance |

-1.6 |

-2.2 |

-2.4 |

-2.2 |

-2.2 |

|

Cyclically adjusted fiscal balance² |

-0.7 |

-2.3 |

-3.4 |

-3.6 |

-3.5 |

|

Underlying fiscal balance² |

-1.4 |

-2.3 |

-3.4 |

-3.6 |

-3.5 |

|

Underlying primary fiscal balance² |

1.7 |

0.4 |

-0.9 |

-1.1 |

-0.6 |

|

Public debt |

|||||

|

Gross debt |

97.3 |

91.9 |

89.5 |

86.6 |

84.8 |

|

Gross debt (Maastricht definition) |

73.8 |

71.3 |

68.9 |

66.0 |

64.1 |

|

Net debt |

65.8 |

62.7 |

59.7 |

57.0 |

55.1 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP

2. As a percentage of potential GDP

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Figure 21. The size of the budget deficit is hidden by the strong economy

As a percentage of GDP¹

1. Figures for 2018 are projections.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

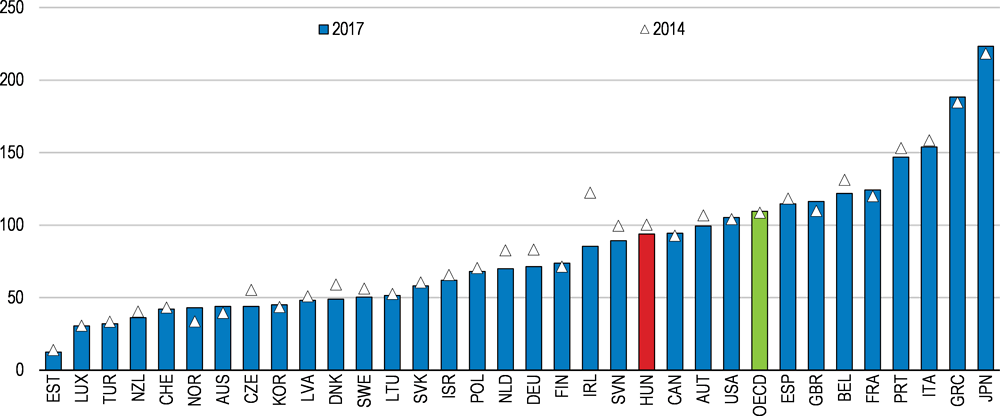

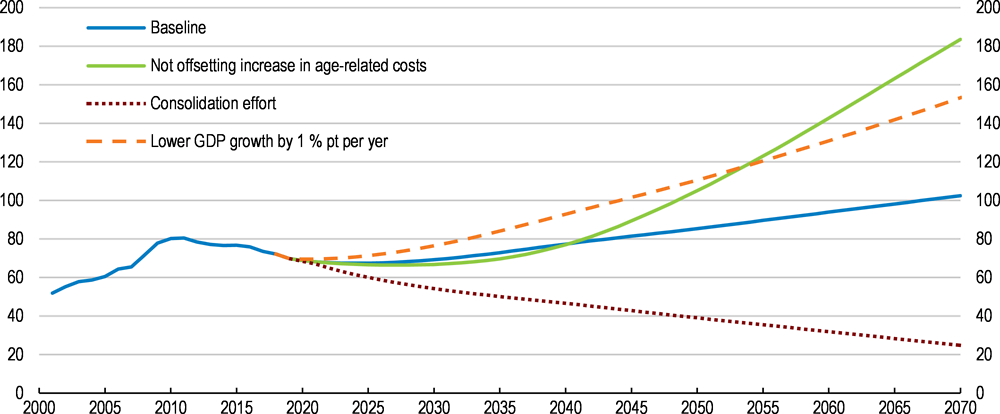

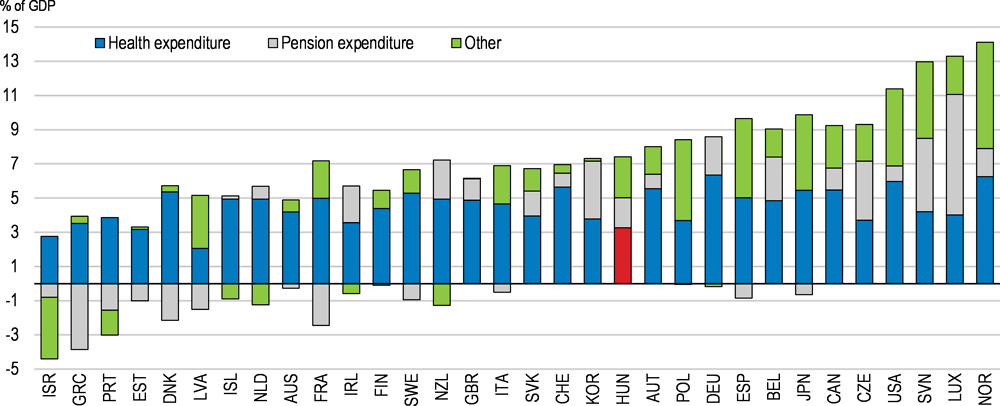

The public debt-to-GDP ratio has declined since its peak in 2014, bringing it just below the OECD average (OECD, 2016a) (Figure 22. General government contingent liabilities remain at nearly one-quarter of GDP. Almost 40% of these are related to government ownership in the financial sector. In addition, one-fifth arises from government controlled entities in non-financial sector, such as the potential cost of the state-owned energy company keeping energy prices at internationally low levels, as raised in the previous Survey (OECD, 2016a) (OECD, 2018b) (Eurostat, 2018b). In line with the constitutional obligation to reduce the public debt-to-GDP ratio to less than 50%, the incoming government has reiterated its commitment to continue a gradual debt reduction. However, the OECD's estimate is that with the current fiscal policy stance the debt-to-GDP ratio will start to increase again after 2019 (Figure 23, Table 5, baseline scenario). Debt would increase markedly faster if the projected increases in age-related spending are not offset by savings in other areas (Not offsetting increase in age-related costs scenario). Similar effects arise if long-term growth fails to materialise as expected, for example if structural reforms fails to raise productivity growth (Lower GDP growth scenario) (European Commission, 2018a). Only fiscal tightening in line with Hungary’s Convergence Programme would keep the public-debt-to-GDP ratio on a downwards trajectory (Consolidation effort scenario) (Ministry for the National Economy, 2018b) (European Commission, 2018a).

Figure 22. General government gross debt

As a percentage of GDP¹

1. 2016 instead of 2017 for Japan, Korea, Turkey and the OECD aggregate.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Improving the resilience of small open economies, such as the Hungarian one, depends on achieving low debt levels (Fall and Fournier, 2015). In this sense, the current debt level, of which one-fifth is held in foreign currencies, is a potential source of fiscal fragility for Hungary with its floating exchange rate, particularly in a context of increasing financial instability for emerging market economies. In addition, a continuous lowering of public debt could form part of a pre-financing strategy to deal with the fiscal consequences of population ageing as discussed below. The government has already taken some measures to reduce the debt burden since the last Survey. The main fiscal and structural recommendations in this survey can substantially support the realisation of the government’s debt objective (Table 6 and Table 7).

Figure 23. More fiscal consolidation effort is needed to reduce public debt

General government debt, Maastricht definition, as a percentage of GDP¹

1. The baseline scenario assumes a continuation of the policy stance of 2019 with a primary deficit of 0.9% of GDP, and inflation around 3%, and real GDP growth initially increases then averages 1.5% in line with assumed productivity growth, as projected under assumed convergence with the European Union (European Commission, 2018). The "Not offsetting rising age-related costs" scenario assumes that increased spending on health and pensions will add an additional 3.2% point of GDP to annual government spending by 2070, in line with European Commission (2018). The “Consolidation effort” scenario assumes, in line with the government's medium-term fiscal objective, budget consolidation of 1.6% of GDP until 2022 and thereafter a primary budget surplus of 0.7% of GDP. The “lower GDP growth” scenario assumes that real GDP growth is 1 percentage points lower than currently projected in the EU convergence scenario for the entire simulation period.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2018), "The Long View: Scenarios for the World Economy to 2060", OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 22., OECD Publishing, Paris; and European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)" Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

Table 5. Debt scenarios

|

Scenario |

Assumptions |

|---|---|

|

Baseline. |

A continuation of the policy stance of 2019 with a primary deficit of 0.9% of GDP Main macroeconomic variables are inflation around 3%, and real GDP growth initially increases then averages 1.5% in line with assumed productivity growth, as projected under assumed convergence with the European Union (European Commission, 2018) |

|

Not offsetting increase in age-related costs. |

Increasing spending on health and pensions will add an additional 3.2% point of GDP to annual government spending by 2070, in line with European Commission (2018). |

|

Lower GDP growth. |

Real GDP growth is 1 percentage points lower than currently projected in the EU convergence scenario for the entire simulation period. |

|

Consolidation effort. |

In line with the government's medium-term fiscal objectives as stated in the Convergence Programme 2018-2022, budget consolidation of 1.6% of GDP until 2022 and thereafter a budget surplus of 0.7% of GDP. |

Source: European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)" Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

Table 6. Past recommendations on fiscal policy

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Continue reducing public debt in accordance with the fiscal rule. |

Since 2016, total debt-to-GDP ratio has declined further to 73.3%. |

|

Reduce government expenditures to further lower the structural deficit. |

No action taken. |

|

Continue the fight against VAT fraud. |

Since 2017, the compulsory use of online cash registers has been expanded to particular service sectors and from 2018, the use of the online invoice system became obligatory. In 2018, the VAT rate has been reduced further on selected products. |

|

Rely more on non-distortive consumption taxes. |

In 2016-2019, the excise duty rate on tobacco products will have been increased gradually, and the excise duty rate on petrol, petroleum and diesel has been linked partially to the world price of Brent crude oil. |

|

Sell stakes in state-owned banks. |

In 2016 and 2017 public stakes in MKB and in Gránit Bank have been sold, leaving Budapest Bank (8th largest) fully state-owned, Erste bank (5th largest) with a 15% and FHB bank (11th largest) with a 7.3% share. |

Table 7. Potential fiscal consequences of key recommendations

|

Recommendations with potential fiscal impact |

Impacts on fiscal balance |

|---|---|

|

Revenue raising measures: |

|

|

Make up for revenue shortfalls from recent lowering of social security contributions and simplify the VAT regime by introducing a single VAT rate. |

A uniform VAT rate of 22% would be revenue neutral. Raising the VAT rate by an additional 5 percentage points would cover the 2.6% of GDP revenue shortfall. |

|

Link the retirement age to life expectancy. |

Increasing the statutory retirement age to 70 years in steps from 2029 will fully cover the projected long-term pension spending increase to 2.7% of GDP. |

|

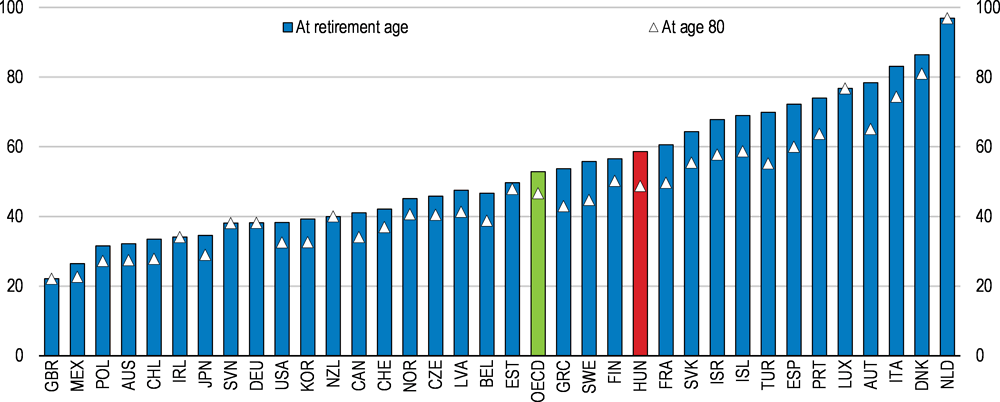

Combat old-age poverty by introducing a basic state pension at twice the current minimum pension. |

Less than +0.1% of GDP. Capping pensions at 150% of average wages would fully cover the fiscal cost. |

|

Spending increasing measures: |

|

|

Improving the efficiency of health care provision. |

Restructuring health care provision is revenue neutral if savings from closing hospitals are spent on outpatient care. Establishing country-wide group practices would cost +0.1% of GDP. Other costs are negligible. |

|

Enhance the capacities and efficiency of long-term care. |

Full coverage of cash benefits and vouchers costs +1.2% of GDP. |

|

Expand crèche coverage to 80%. |

+0.2% of GDP |

|

Double duration of unemployment benefit to six months. |

+0.3% of GDP. |

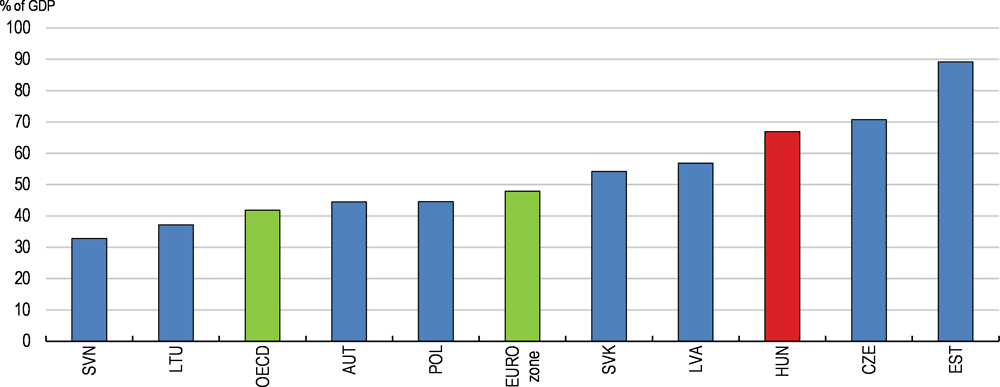

Towards a more growth-friendly and equitable tax system

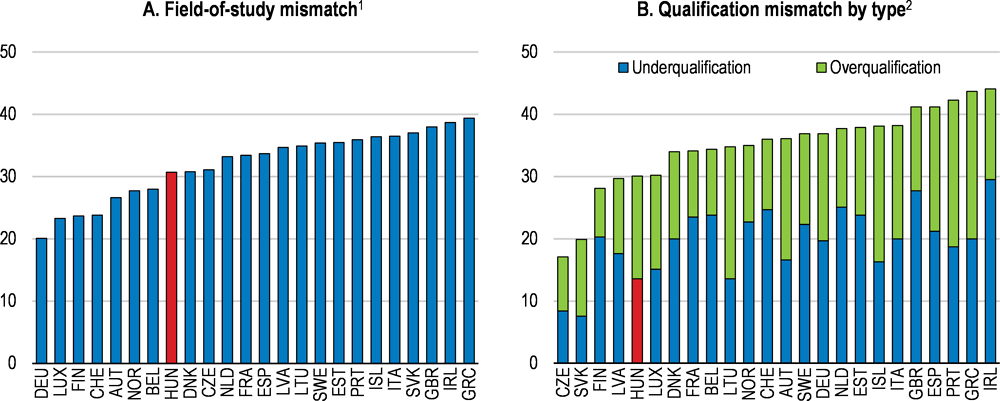

As discussed below, ageing-related spending pressures are rising with population ageing. Reforms may contain some of these spending pressures, but not all. In the absence of offsetting savings elsewhere, such spending would have to be financed through increases in the already high tax-to-GDP ratio (Figure 24). As an illustration, OECD calculations suggest that an increase of 10 percentage points in the social security contribution rates is needed in the long run. However, such an outcome would hurt growth. Insofar as it is necessary to raise additional revenues, this should be done in the least growth distortionary manner possible.

Figure 24. Tax revenues are already high as a share of GDP

As a percentage of GDP, 2017¹

Property taxation, the least distortive type of tax, plays a relative small role in Hungary (Johansson, 2016). Immovable property taxes are optional and levied by municipalities (OECD, 2012a) (OECD, 2010). Raising recurrent taxes on immovable property could involve giving municipalities incentives to have a minimum local property tax or introduce a national property tax. Such measures would make the tax system more neutral vis-a-vis other types of investment and thus improve resource allocation (OECD, 2010).

The VAT system is complicated with a range of reduced rates on selected items. However, reductions implemented in 2006-2009 have not really benefited low-income groups (Cseres-Gergely, 2017). Thus, moving towards a single VAT rate would be less distortive. A single VAT rate could be some 5 percentage points lower than the current standard rate without revenue losses. This could be combined with better targeted social transfers to help low-income households (OECD, 2014a) (Cseres-Gergely, 2017) (Arnold, 2011) (OECD, 2012a). Moreover, tax allowances for families or owner-occupied housing are costly in terms of foregone revenues without favouring equity, and should be replaced by better targeted means-tested transfers (Rawdanowicz, Wurzel and Christensen, 2013). Expenditure in connection with family support is estimated at 4.8% of GDP in 2018 (Ministry for National Economy, 2017).

Savings in non-ageing related spending could, at least partly, avoid the need for increases in taxation. Indeed, the ratio of public spending-to-GDP is relatively high, particularly compared with other countries with similar income levels (Figure 25, Panel A) (OECD, 2016a). Moreover, spending is tilted towards general public services and general economic affairs compared with countries with similar income levels or size of public spending (Figure 25, Panel B). This reflects high interest payments on public debt and the relatively high share of the labour force employed by the public sector (including public work schemes enrolees). The public wage bill could be reduced through faster adaptation of e‑government measures and public administration reform that focuses on securing a competitive public wages and improving the quality of public service provision (IMF, 2018).

Figure 25. The tax structure is tilted towards consumption and labour taxes

Addressing longer-run challenges to well-being

Broadening growth

During the crisis, the income convergence process halted and only started again in 2013 (Figure 1). The large reliance of inwards FDI to support the convergence process by building up a modern capital stock and linking production to global value chains has also resulted in relatively large capital outflows, reflecting the remuneration of invested capital FDI (Figure 26) (Jirasavetakul and Rahman, 2018). This is also reflected in a relatively large wedge between GDP per capita and net national income per capita and in a relatively low wage share compared with more advanced economies. Thus, achieving faster income convergence does not only rely on achieving faster growth, but also on going beyond the reliance on inward FDI and developing domestic growth drivers.

Figure 26. Hungary is benefitting from a relatively high stock of inward FDI

In 2017, the government established a National Competitiveness Council to further productivity growth and income convergence. The Council consists of leaders from government, private and public sectors as well as representatives from academia, and relies on inputs from ministries and the Central Bank to identify relevant structural reform. The Central Bank has suggested 180 measures in areas covering labour market, health care, education, research and development, regulation, and SME support (Palotai and Virag, 2016) (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2018d). Many of these have been discussed in previous Surveys, and this Survey focusses on widening the growth process to include less developed regions, improved human capital formation and better utilisation of available labour resources, including measures to improve health and pension systems. Implementing the key structural reform recommendation in this survey would already have a large impact on incomes (Box 1.).

Box 1. Simulations of the potential impact of structural reforms

The impact of the key structural reform recommendations in this Survey is simulated by using historical relationships between reforms and growth in OECD countries. The presented estimates assume swift and full implementation of reforms of reduced the effective maternity leave to 1 year, gradually increase the legal retirement age by 5 years and improved health outcomes. The transmission mechanisms are mainly through the associated increase in the labour supply.

Table 8. Potential impact of structural reforms on GDP per capita after 10 years

|

Structural policy |

Policy change |

Total effect on GDP per capita |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Before reform |

After reform |

||

|

Health policy |

|||

|

A. Improved health outcomes that reduces the disability rate from 7.7% to 6% of the labour force |

1.8% |

||

|

Labour market policies1 |

|||

|

B. Increase the legal retirement age by 5 years |

65 years |

70 years |

5.1% |

|

C. Reduce effective maternity leave to 1 year |

3 years |

1 year |

1.4% |

|

Total A+B+C: |

8.3% |

||

Source: OECD calculations based on Balázs and Gal (2016), "The quantification of structural reforms in OECD countries: A new framework", OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol. 2016/1 and Balázs (2017), “The quantification of structural reforms: taking stock of the results for OECD and non-OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, forthcoming.

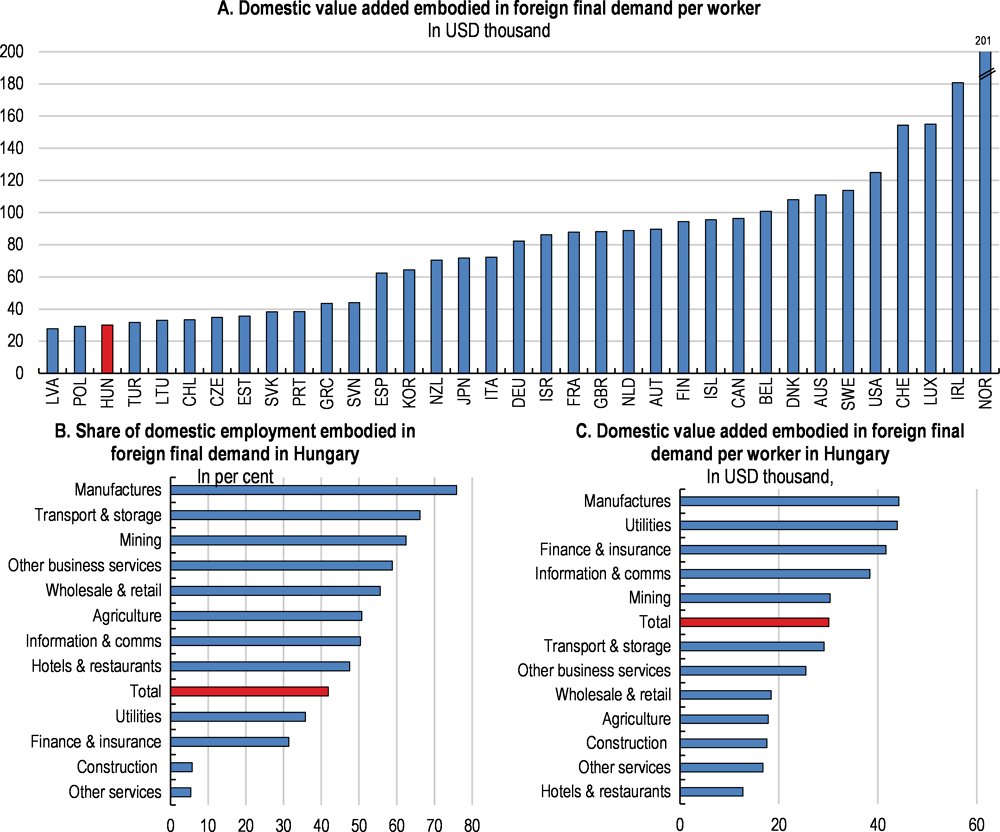

The large inflows of FDI have, in many respects, contributed to the emergence of a dual economy. Inward FDI is driven by multinational companies moving their production destined for their international markets to Hungary. The recent reduction in the corporate tax rate would support business investment, including from abroad, which according to OECD estimates could bolster GDP growth by 0.2 percentage point after 10 years (Égert, 2018). However, the intermediate inputs into their production are imported or come from foreign-owned sub-contractors in Hungary. Indeed, available evidence indicates that Hungarian-owned firms, particularly SMEs, do not benefit from inward FDI in terms of higher sales, employment or productivity (Bisztray, 2016). As a result, the benefits to the domestic economy of the integration into global value chains in the form of domestic value added in final foreign demand has been low (Box 2). The other important growth area is the capital region that has benefitted from strong agglomeration effects and increasing demand for business services.

Fostering the development of local SMEs is a complex process, since the ability for local firms to exploit their comparative advantage depends on how well they are integrated into local and national networks. These include physical infrastructure (transport, communication, etc.), knowledge networks (local education and research centres) and links with other business and policy makers to identify local advantages and to provide framework conditions. However, the high degree of centralisation of government responsibilities is likely to hamper this process.

Box 2. Economic upgrading through integration in the Global Value Chains (GVCs)

Geographic proximity to Western European markets, significantly lower labour costs, well-developed transport infrastructures and increasing agglomeration economies have contributed to high integration in GVCs over the last two decades (Pavlínek, 2015). Nonetheless, domestic value added in exports is among the lowest in the OECD (Figure 27, Panel A). This reflects that although more than 40% of all jobs are generated through participation in GVCs and nearly 80% of manufacturing jobs. However, many of these jobs are in less knowledge intensive activities, such as assembly in the automotive industry (Figure 27, Panel B and C).

Figure 27. Benefits from participating in GVCs are moderate

2015¹

1. Domestic value added embodied in foreign final demand per worker refers to domestic employment embodied in foreign final demand. Business activities also include real estate and rental services.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD STAN (database); and OECD (2018), Trade in Value Added (TiVa) (database).

Raising the value added from GVC participation requires either traditional process and product upgrading or better integration through functional and chain upgrading, i.e. entering existing or new higher value added GVCs, respectively (Humphrey and Schmitz, 2002) (OECD, 2013]). In all cases, policy measures to pursue such upgrades need to focus on promoting human and physical capital formation as well as the exploitation of local comparative advantages.

Sources: Based on OECD (2017), Employment Outlook 2017; OECD (2017) Skills Outlook 2017: Skills and Global Value Chains.

Hungary has gone from being possibly the most decentralised to the most centrally organised country in the OECD (Hoffman, 2014). Development policies are determined and financed at the centre. This leads to a situation where local development hinges on national priorities and where local authorities focus on centrally-financed projects, including EU funds (Kovacs, 2015). At the same time, there are few attempts to identify local economic advantages and develop local networks to integrate into regional or national supply chains (Hajnal and Ugrosdy, 2015).

To better adapt policies to local conditions, local authorities should be given more responsibility for identifying and implementing relevant projects to develop their local economies. OECD work finds that in an increasingly interconnected world local governments are well placed to provide support for local firms, while central governments are best placed to address inequality issues (Broadway and Dougherty, 2018). Project selection could be improved through greater co-financing, which would give local authorities a direct economic stake in selecting the best projects. Not all local authorities have the capacity for identifying and selecting projects, as they are very small or very poor. In such cases, local authorities could enter horizontal cooperation to generate the sufficient administrative capacity. Alternatively, they could be provided with administrative and technical support from higher levels of government (Bartolini, Stossberg and Blöchliger, 2016). In addition, such devolution of power would have to be accompanied by greater revenue raising powers for local authorities. This would allow the central government to withdraw from detailed policy analysis and implementation to concentrate on more traditional supervision of local governments to secure that the devolution of powers lead to improved outcomes (Phillips, 2018) (OECD, 2017b).

Regional growth can emerge by promoting agglomeration effects between cities and with their surrounding area through better functioning housing and transport infrastructures to promote geographical mobility and allow better integration into local and national networks (see below) (Ahrend et al., 2017). In poor rural areas, employment can be fostered by developing tourism and agriculture. However, there are only few measures in place for either sector to integrate into other sectors or exploit networks to move up the value added chains This often requires measures at the local level and could include branding and the creation of high-value added tourism experiences, for example through culinary services based on local produce (OECD, 2014). Social media could be used to reach new visitors and promotion of new tourist services to supplement traditional heritage- and culture-based experiences. Such initiatives have to be complemented with the development of a modern international tourism promotion strategy.

Faster regional growth and convergence will lift the low level of aggregate labour productivity part of the way towards advanced economies (Figure 28). This can be supported at the local level by lifting up the skills of workers, which would enable local firms to benefit from knowledge diffusion and technological adaptation to move production from low-skilled activities to higher-skilled and higher-value activities (OECD, 2017c; Morrison, Pietrobelli and Rabellotti, 2008; OECD, 2015a). To better support local SMEs, vocational schools should have greater freedom to adjust courses and curriculums to reflect the needs of the local labour market. In addition, the schools should specialise more to exploit economies of scale and scope, for example to better invest in modern machinery and equipment. This needs to be combined with stronger mobility incentives, both for students to pursue their preferred courses and for graduates to relocate to areas with job opportunities that match their acquired skills. These efforts should be supported by measures to promote life-long learning, for example individual learning accounts as recommended in the last Survey (OECD, 2016a).

Figure 28. Productivity has failed to catch up

Real GDP per persons employed, in USD thousand, constant prices, 2010 PPPs¹

Addressing labour market challenges

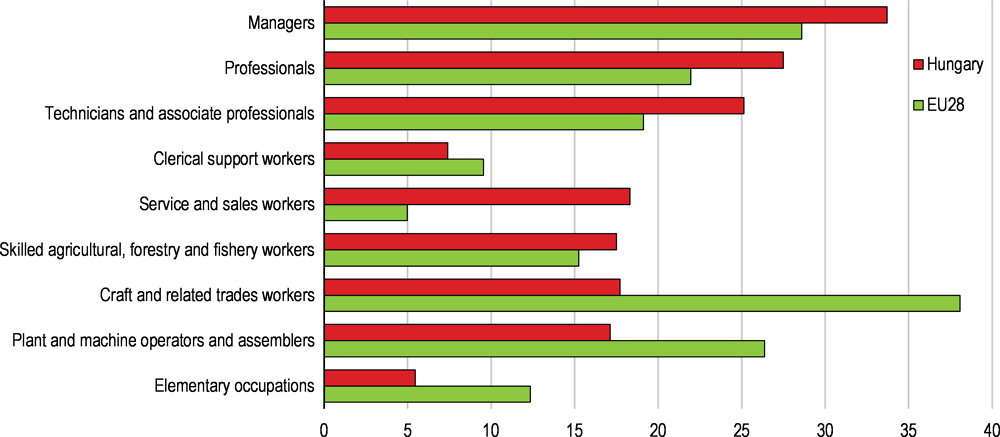

The labour market is shifting towards higher-skilled employment (Figure 29). This reflects that over the past decades, the service sector has expanded and industry has moved from mining and heavy industries to higher value-added production that links into global value chains. This has led to an increase in medium and high technological intensive manufacturing, although manufacturing accounts for a smaller part of overall employment (OECD, 2016a). Moreover, agriculture is characterised by very small farms, indicating considerable scope for growth-enhancing restructuring that would further reduce employment in that sector. These changes are taking place as firms increasingly search for skilled workers. Thus, to sustain growth it is becoming increasingly important to adjust and enhance skills, improve allocation of labour and mobilise all underutilised labour resources.

One of the main active labour market policy instrument is public work schemes administered by the Ministry of the Interior and provided by municipalities. These are being scaled down at a moderate pace. The schemes pay wages that are above social transfer and have been successful anti-poverty measures, but less so as an active labour market measure (ALMP) as until recently only 10%-12% of enrolees have subsequently found employment in the primary labour market. Since early 2017, the share has increased to 19%, partly reflecting increased job opportunities. The government should use the favourable labour market situation to scale down faster the schemes and to concentrate their use in poor rural areas as a poverty reduction measure.

The schemes could become effective as an active labour market measure by moving the responsibility for the schemes to the ministry responsible for labour affairs to better link them to other ALMP schemes and labour market institutions. In addition, the provision could involve the private sector to strengthen activities that links better to the requirements in primary labour market. Also, the training content could be enhanced further and better linked to skill requirements in the primary labour market. Combining this with mobility measures would further improve transition into the primary labour market as many of the low-skilled enrolees live in rural areas with limited economic activity.

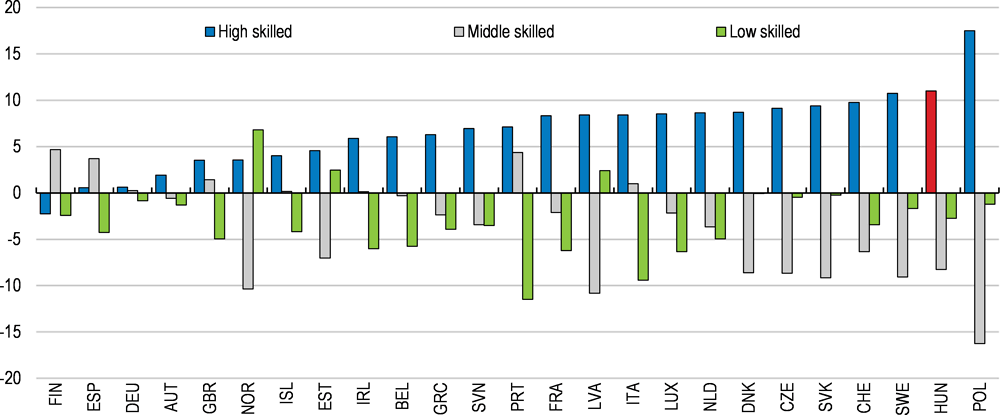

Figure 29. The shift towards high skilled employment is expected to continue

Change in share of total employment between 2015 and 2025, in percentage points¹

1. High-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 1, 2, and 3. That is legislators, senior officials, and managers (group 1), professionals (group 2), and technicians and associate professionals (group 3). Middle-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 4, 7, and 8. That is, clerks (group 4), craft and related trades workers (group 7), and plant and machine operators and assemblers (group 8). Low-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 5 and 9. That is, service workers and shop and market sales workers (group 5), and elementary occupations (group 9). The ISCO-88 major group 6 for skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers is excluded.

Source: CEDEFOP (2017), "Forecasting skill demand and supply", European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/events-and-projects/projects/forecasting-skill-demand-and-supply/.

The increasing labour scarcity and the continued restructuring of the economy mean that improved labour resource allocation is becoming more important to sustain growth. The turnover on the labour market is relatively low despite flexible labour market institutions (Figure 30). On the other hand, the allocation process is hampered by a lack of geographical mobility. This is related to a rigid housing market (only 7% of households moved within a two-year period – less than a third of the rate in the Nordic countries) dominated by owner-occupation and poor quality secondary and tertiary road infrastructure that add to commuting costs (McGowan, 2015). The rental segment of the housing market is very small (and increasingly targeting higher income tenants) and the government should ensure that taxation of investments in private rental and owner-occupation is neutral.

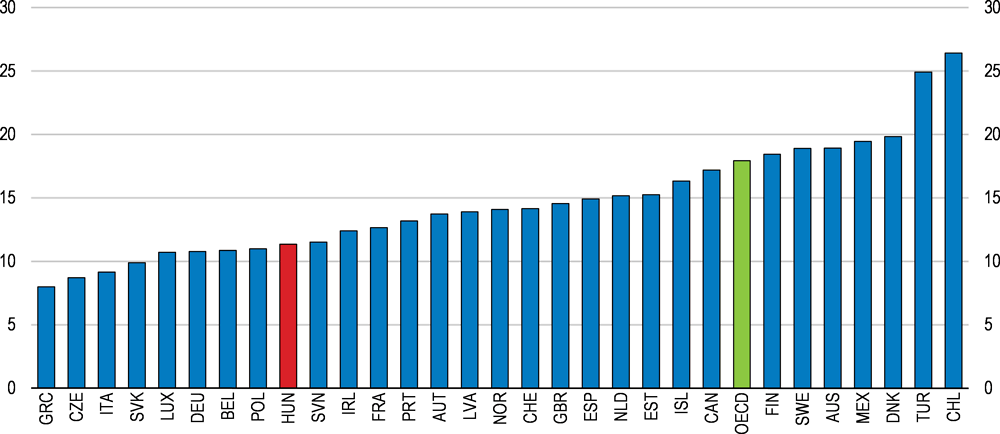

The short 3-months duration of unemployment benefits bolster participation incentives. On the other hand, the short duration also reduces job search and matching incentives, contributing to labour market mismatches (Figure 31). Part of the mismatch problem is cyclical, reflecting that employers have increasing problems of finding qualified workers. On the other hand, the very short duration of unemployment benefits gives unemployed insufficient time to find employment that matches their skills. Extending duration, to for example 6 months, would address this issue. Furthermore, search incentives could be enhanced by reducing benefits over time while providing mobility support for interviews and first phase of employment.

Figure 30. Labour market turnover is relatively low

Job separation rate, in per cent, 2016¹

1. 2015 for Australia and Denmark. Data refer to the difference between the hiring rate and the net employment change.

Source: OECD (2018) OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database).

Figure 31. Skills mismatches could be further reduced

As a percentage of all workers, 2016

1. Field-of-study mismatch arises when workers are employed in a different field from what they have specialised in.

2. Qualification mismatch arises when workers have an educational attainment that is higher or lower than that required by their job. If their education level is higher than that required by their job, workers are classified as over-qualified; if the opposite is true, they are classified as underqualified.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database).

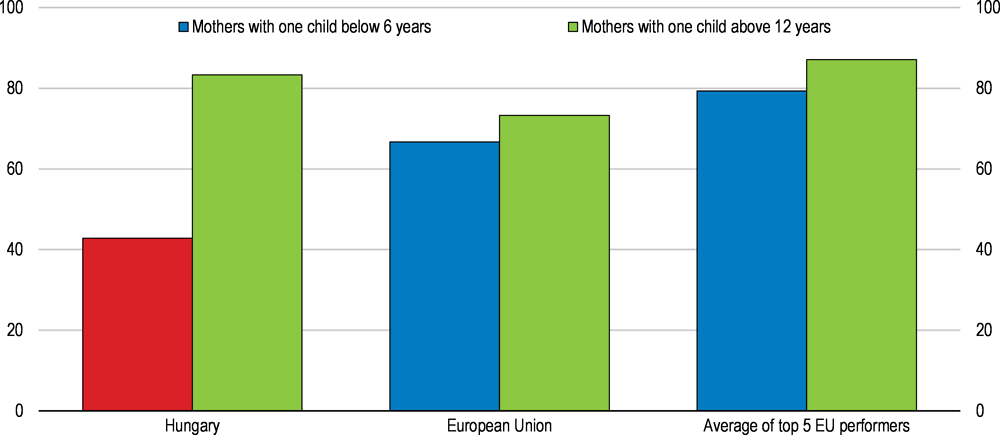

The female labour market situation has improved significantly, in many ways restoring the pre-transition situation of high female labour force participation and gender equality in education (Avlijas, 2016) (United Nations Development Fund for Women, 2006) (Czibere, 2014). By 2016, the female employment rate had reached a new high of around 60%, which is similar to the EU average, but more than 10 percentage points below best performers. The exception, however, is mothers with young children (below 6), who have much lower employment rates (Figure 32) (OECD, 2018c). This reflects leave that can last up to three years (consisting of six months maternity leave, 18 months parental leave and an additional year on lower benefits). The crèche system is being expanded in line with recommendations in the previous Survey (Table 9). The current enrolment rate of 17.5% is higher than in Hungary’s regional peers, but is still less than half the OECD average, often leading mothers to take the full leave period (Gábos, 2017) (Századvég, 2016). In addition, kindergartens have become mandatory from the age of 3 (boosting enrolment to 95.7% and thus surpassing the EU benchmark of 95%), but often have rigid opening hours (legislative requirements are 8 hours and usually kindergartens close early) which complicate achieving good work-life balances (Hermann, Bobkov and Csoba, 2014).

Figure 32. Mothers with young children have relatively low employment rates

As a percentage of working-age female population, 2017¹

1. Data refer to population aged 15-64.

Source: Eurostat (2018), "Gender equality", Eurostat Database.

The overall gender pay gap is 9% – 5 percentage points below the EU average. However, the combined long leave periods for maternity reasons reduce the incentive to hire young females and hurt their career prospects, which leads to a widening gender wage gap as education and skills requirements increase (Figure 33). The newly established Family and Career point programme supports returning mothers through training, coaching, and mentoring programmes. This is also reflected a relatively wide gap in the top income quintile with a 34% difference in pay between male and female managers – the largest in the EU (Sik, Csaba and Hann, 2013) (Szabó, 2017). Indeed, one-third of companies are headed by a female director, but rarely in highly paid executive jobs for large companies (Bisnote, 2017).

Table 9. Past recommendations on labour market

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken |

|

Further reduce tax wedge on low salaries and better target existing cuts in social security contributions. |

Tax wedge has been reduced by decreasing employers' social contributions by 7.5 percentage points. In 2018, the family tax base allowance for families with two children has been increased by 17%. |

|

Avoid increasing the minimum wage by more than warranted by inflation and productivity developments, and consider even freezing it for some time. |

The 2016 tripartite 6-year wage-agreement raised the minimum wage and the guaranteed wage minimum for skilled workers by 15% and 25% in 2017, respectively, and by 8% and 12% in 2018. In parallel, employers’ social security contributions were cut. |

|

Improve reintegration of public works participants. |

Since 2018, NGOs cooperating with PES provide: a) counselling and mentoring services; and b) financial benefits for disadvantaged jobseekers to foster their re-entry into the labour market. The 2017 “From the public work to the primary labour market" programme encourages public workers to find a job in the primary labour market by providing them benefits. |

|

Improve the evaluation of the efficiency of existing training programmes to better match different categories of participants to specific training programmes. |

Since 2016, PES has created individual action plans for all registered job seekers based on client profiling. |

|

Tighten the conditions for public work schemes by efficient implementation of a profiling system. |

In 2016, a new client profiling system was implemented to improve targeting of the public work schemes. |

|

Facilitate visa requirements to attract high-skilled immigrants in potential skill shortage domains. |

No action taken. |

|

Expand early childhood care. |

From January 2017, all local governments are required to organise crèche services where such services are demanded. |

|

Reduce the effective length of parental leave and provide incentives for paternity leave |

No action taken. |

Figure 33. Gender pay gaps are increasing with education and skills requirements unlike in the EU

As a percentage of mean hourly earnings of men, 2014¹

1. Gender pay gap is calculated as the difference in mean hourly earnings of men and women divided by mean hourly earnings of men. Data refer to industry, construction and services (except public administration, defence, compulsory social security).

Source: Eurostat (2018), "Gender equality", Eurostat Database.

Bolstering the employment rate of young women with children would support growth, preserve human capital, enhance available labour resources and expand female lifetime income, and particularly their pensions (OECD, 2012b) (Kinloch, 2015). The three-year leave period for maternity reasons is internationally long. For example, the Nordic countries have paid leave periods of one year or less, and they have some of the lowest gender gaps in the OECD. The government should enhance incentives for mothers to participate in the labour market. This should reduce the effective length of parental leave. This should be combined with greater possibilities for transforming part of it into paternity leave as recommended in the last Survey (OECD, 2016a). This would have to be accompanied by a large expansion of childcare facilities. The latter could be accelerated by incentivising the private sector through tax breaks to provide company based care, as in France. With a corporate tax rate of 9% the value of such breaks would be relatively low and may need to be complimented with more direct subsidies in addition to the financial support for workplace crèches (Brosses, 2012) (Varga, 2016) (OECD, 2016a) (European Commission Staff Working Document, 2018).

Working mothers also need more flexible working arrangements to secure an acceptable work-life balance. The government has already lowered social security contribution for employers hiring mothers with young children, allowed working mothers to receive maternity benefits after the child's first birthday and obliged employers to allow mothers to return on a part-time basis. The last, however, could potentially discourage firms from hiring young women, particularly in SMEs, or channel women into different and lower ("mommy track") career paths.

A better approach would be more flexible working arrangements with respect to daily working hours, teleworking, etc. that serve the needs of both employers and employees. The Labour Code allows for some flexible employment opportunities, such as the right for part-time employment for parents. Moreover, European Union co-financed programmes promote flexible employment in SMEs. Nonetheless, only a fraction of workers has such entitlements. In other countries (i.e. UK, Belgium, Germany) employees have the right to request flexible work schedule. The public sector could also lead by example by creating a flexible and inclusive working environment (OECD, 2016b).

Work-life balance could be improved further with more equal division of caring responsibilities, such as in Germany where the second parent's leave is added to overall leave period (Unterhofer and Wrohlich, 2017). The literature has pointed to other problems, such as a lack of role models (ILO, 2016) and gender stereotyping in the education system (United Nations, 2016). Career counselling or board representation rules could counter such problems (Wade et al., 2010) (Thomas, 2016). The complexities of achieving the proper work-life balance in the context of a dynamic Hungarian economic development point to a need for further research in this area.

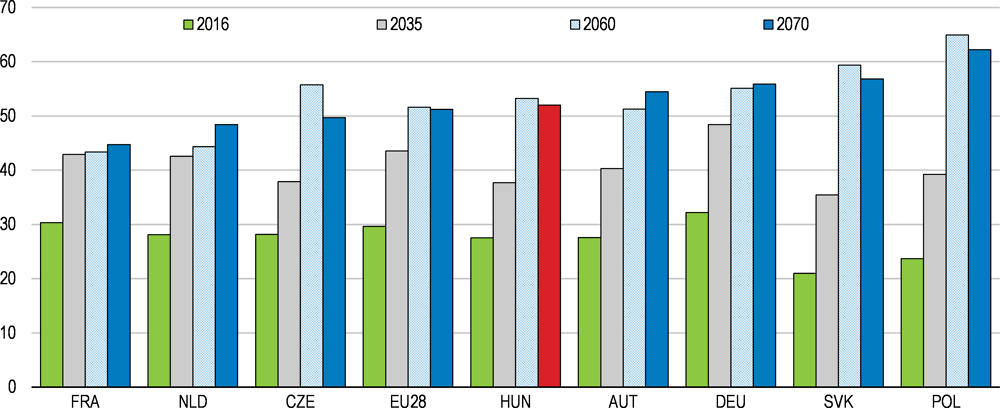

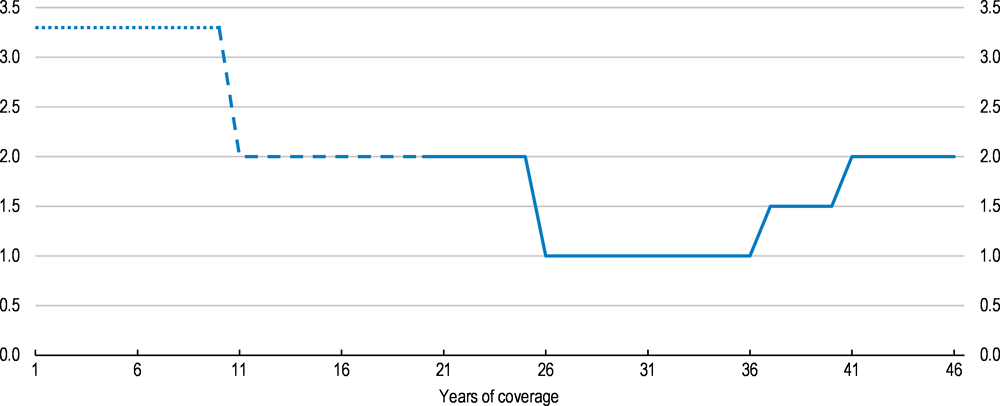

The population is ageing