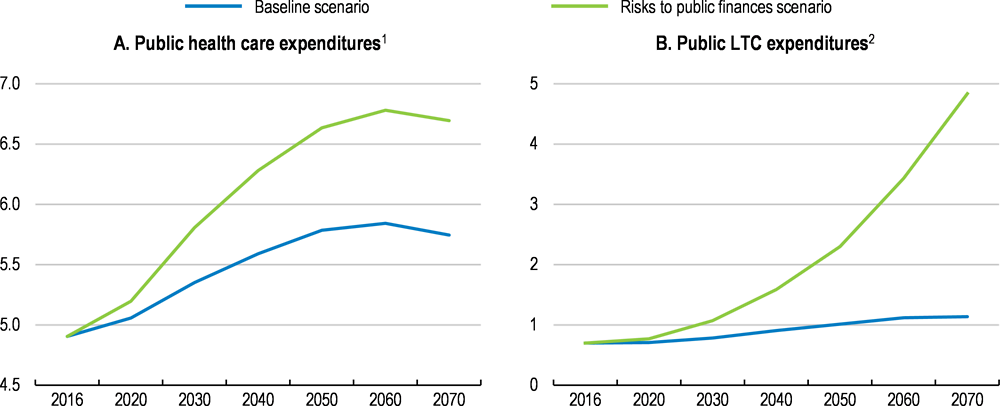

Population ageing is leading to rising financing pressures in the pension, health care and long-term care systems. Official projections suggest that ageing-related spending could increase by 3.2% of GDP by 2070. Less optimistic assumptions about demographic developments and labour market outcomes could add several percentage points to pension spending. Moreover, the risk of old-age poverty is relatively high in the earnings-related pay-as-you-go pension system, and expected pension benefits are difficult to calculate. Measures to correct these issues could double the projected increase in public pension spending in the long run. In addition, the centralised health care system has relatively little use of price signals, contributing to reduced access and outcomes that are worse than elsewhere. Structural reform could improve efficiency, but securing a projected increase in life expectancy of 10 years, aligning it with the EU average, is likely to require additional public resources. This, together with the cost of new technologies and improving quality and coverage, could increase spending by as much as 50% by 2070. The fragmented long-term care system is putting a relatively large responsibility for such care on family members, implying that public spending in this area will increase, particularly as economic structural changes affects the geographical distribution of the population.

OECD Economic Surveys: Hungary 2019

Chapter 1. The challenges of sustaining Hungary’s pension and health systems

Introduction

The Hungarian population is ageing and shrinking, increasing pressures on ageing-related spending and the contribution base (European Commission, 2018a). In 2016, there were 2.5 million old-age pensioners, roughly one-quarter of the population (Ministry for National Economy, 2017). Total public expenditure on pensions was 9.7% of GDP in 2016, while public expenditure on health and long-term care was 5.6% of GDP (European Commission, 2017). Over the longer term, the number of old-age pensioners is set to rise while the overall population will shrink from 9.8 million to 8.9 million nearly doubling the old-age dependency ratio (European Commission, 2017). The resulting decline in the old‑age support ratio is particularly challenging for pay-as-you-go pension schemes such as Hungary’s as pension spending is financed by contributions of current workers (Fall and Bloch, 2014).

One of the main problems that the pension system will face is therefore that spending on pension benefits will increase faster than contributions. If no offsetting measures are taken, general government debt (Maastricht definition) could exceed 180% of GDP by 2070 (see Key Policy Insights). In addition, the design of the current system involves a high risk of old-age poverty, as well as large variations in pension benefits between workers with similar careers but retiring at different time. Moreover, it is difficult for people in the labour market to predict their future pension benefits. The health system, meanwhile, is based on central planning with little use of price signals, hampering its ability to adjust health-care supply to the demographic changes. An additional challenge is to enhance the sector’s low efficiency as life expectancy is presumed to increase by a decade to converge with the European average – a development that is likely to raise health spending towards European levels. The first part of this chapter will analyse the challenges related to the structure of the current pension system, the second part of the chapter will focus on health policy.

The public pay-as-you-go pension system runs a deficit

Well-functioning pension systems are both actuarially fair (people receive pensions in proportion to their contributions) and actuarially neutral (early or late retirement leads to decrements or increments to their pension benefits to correct for missing contributions or over-contributions) (Fall and Bloch, 2014) (Queisser and Whitehouse, 2006). To be actuarially fair, people should receive in retirement the same as what they paid in when working, together with the investment returns on the accumulated assets before retirement (Fall and Bloch, 2014).

The Hungarian pension system is a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) single pillar, earnings-related scheme with defined benefits (DB) (OECD, 2017a). It is not fully actuarially fair owing to the non-linearity of pension accruals and the valorisation of earnings, and there is a lack of actuarially neutral adjustment for early retirement rules for women who can retire without penalties. These are discussed below.

At least 15 years of work is required to receive some pension benefits, and 20 years are required for a full pension. There is no basic (universal) state pension. Those with fewer than 15 years’ accrual are not entitled to a pension, but can receive social assistance, worth around 8.3% of average gross earnings, or roughly 12%-19% of net earnings (with in-kind benefits worth around 25% of the value of benefits) (OECD, 2017a). Only Turkey, Mexico and Korea provide lower safety-nets within the OECD (OECD, 2015a).

There is a minimum monthly pension of HUF 28 500 (EUR 90) for workers with at least 20 years’ accrual. It is mainly relevant for low-wage income earners who lost income during the transition to a market economy in the early 1990s, and currently few pensioners rely on it (OECD, 2017a) (Ministry for National Economy, 2017). However, the cohorts born between 1960 and the 1980s, who were the most affected by the economic transition, will have had more difficulty earning a full pension, and as many as 4% of a cohort may have to rely on the minimum pension, or the social safety net (Augusztinovics et al., 2009).The amount of the minimum pension is 40% below of the poverty level (defined as half the median wage). It has been unchanged in nominal terms since 2008 and is used to benchmark other social benefits. Safety-net incomes ought to be indexed to prices to maintain purchasing power.

The PAYG system includes all workers, including the self-employed, and provides survivors' pensions. Nearly all other schemes or special regimes have been abolished or are being phased out (Ministry for National Economy, 2017). Workers and employers pay social security contributions of 10% and 19.5% of gross earnings, respectively (Ministry of the National Economy, 2018). In 2018, 79.5% of the total social contributions went to the Pension Insurance Fund while the rest was directed to the Health Insurance Fund (Ministry for National Economy, 2017). In addition, the 2018 Budget Act allocates additional subsidies of 0.2% of GDP, to cover pension payments.

A second pillar of a mandatory private defined contributions (DC) scheme to supplement the PAYG system was dissolved in 2010 and the funds transferred back to the state to repay public debt (OECD, 2012) (Freudenberg, Berki and Reiff, 2016). In doing so, an important funding source for future pensions was removed (Box 1.1). In the third pillar, various voluntary pension insurance and savings schemes have around 1.3 million members.

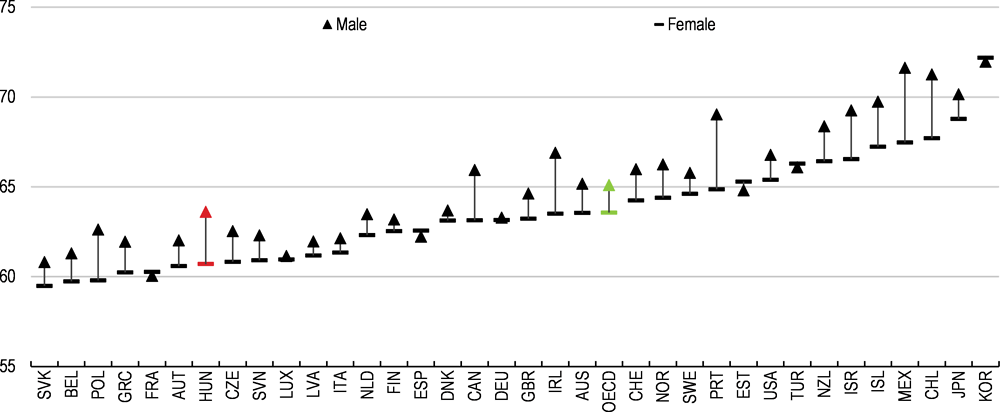

The statutory retirement age is gradually being increased to 65 years by 2022 for men and women (Box 1.1). It was 63.5 at the beginning of 2018. The retirement age is lower than in most other OECD countries, and will remain below the OECD average even after 2022 (European Commission, 2018b) (OECD, 2017a). The government has sought to increase the effective retirement age by raising the official pension age while abolishing most forms of early retirement (OECD, 2017a) (OECD, 2018a). Curbing early retirement combined with the increase in the statutory retirement age has increased the effective retirement age by just over one year to 62 years for men and women combined since 2012 (European Commission, 2018a). However, the effective retirement age remains well below the OECD average, especially for women (Figure 1.1).

In 2017, the pre-tax pension replacement rate (the ratio of initial pensions to last earnings) for Hungary was 58.7% (OECD, 2018b), above the OECD average of 52.9% (OECD, 2017a). Since January 2012, pension benefits have been indexed to prices, based on the projected consumer price index (CPI) in the annual budget. A retroactive upwards correction takes place by end-year in case the full-year CPI overshoots projections (OECD, 2017a).

A pension premium is paid to existing pensioners at end-year if annual GDP growth exceeds 3.5%, and provided the budget is evolving according to projections. The premium is calculated by subtracting 3.5 from the year’s GDP growth in percentage points and multiplying it with 25% of the monthly pension payment, with a ceiling of EUR 250. In 2017, the majority of pensioners received an additional pay-out of around EUR 37, but some only received the minimum of EUR 20. To ensure that pensioners benefit from periods of economic upswing, a less arbitrary solution would be a rules-based system, such as wage (or part-wage) indexation.

Figure 1.1. The effective retirement age remains below the OECD average, especially for women

Box 1.1. Recent pension reforms

The 2009 reform

The statutory retirement rage was raised from 62 years to 65 years, increasing by 0.5 years every year for cohorts born after 1952, to be fully implemented by 2022.

Indexation of pension benefits in retirement was switched in steps from a 50% price-50% wage index (so-called "Swiss indexation") to pure price indexation linked to the national CPI which was implemented from 2012 (Domonkos and Simonovits, 2016).

The 2010 reform (the "switchback reform")

The government reversed the three-pillar system introduced by the 1997 Pension Law:

• The second mandatory defined contributions pillar was de facto eliminated. Roughly 90% of the capital (around 11% of GDP) accumulated between 1998 and 2010 by the mandatory private pension funds was transferred into the general government budget, leaving a sizeable budget surplus in 2011 (OECD, 2012) (Freudenberg et al, 2016). All payments out from the pillar were suspended, and all previous mandatory payments (employer and employee contributions) were diverted into the PAYG scheme (Freudenberg, Berki and Reiff, 2016).

• From 2011, new labour market entrants are automatically enrolled in the PAYG system.

• Before the reversal more than 70% of the labour force were members of a labour market pension fund. After the reversal only 102 000 scheme members stayed in the defined‑contribution scheme; essentially young people and high-income earners. According to the current rules, remaining members accrue pensions in the first pillar, but they can only make additional payments to the second pillar on a voluntary basis, and there is no annuity upon retirement but a lump sum payment. Today some 57 000 members remain in the scheme (Casey, 2012) (Freudenberg, Berki and Reiff, 2016).

The 2011 reform: abolishing early retirement and 2011 income-tax reform

• From 2011, all forms of early retirement were abolished (with exception of women with 40 years' service, the “Women 40” scheme). Prior to 2011 more than 30% of pension beneficiaries were below the statutory retirement age, mainly owing to early retirement or disability (OECD, 2010). Disability pensions were separated from the old-age pension system and transformed into a special disability provision, as was rehabilitation.

• Special service pension benefits for the armed forces where abolished, with the exception of recipients having reached the age of 57 before December 2011 (OECD, 2018a).

• The special treatment of workers in arduous/hazardous work was eliminated. Replaced by a “benefit prior to retirement age”, where benefits are not means-tested, financed by taxes paid to the general budget. Some 2 000 people receive these benefits every year (OECD, 2018a).

• The flat-rate income tax reform of 2011 led to an increase of post-tax net earnings. It also simultaneously removed the tax-free bottom income threshold (Kosa, 2012). As a result, wage‑earners who retired post-2011 will have earned higher pensions for the same contribution rates than previous retirement cohorts. High-income groups have befitted disproportionately as low‑income groups no longer have a tax-free threshold and therefore have a lower take-home pay on which pension entitlements are calculated (Czeglédi et al., 2016).

Calculation of pension benefits

Pension entitlements are calculated from monthly average earnings net of income tax and social contributions. An accrual rate is attributed for each year worked. At retirement, the total accrual is converted into pension benefits by multiplying the accumulated accrual rate with average lifetime earnings. Earnings are adjusted annually by the previous year’s national average-wage increase (known as valorisation) to reflect rising economy-wide welfare during the service time (OECD, 2017a) (Czegledi et al., 2017) (Ministry for National Economy, 2017) (Freudenberg, Berki and Reiff, 2016) (OECD, 2018a). Above HUF 372 000 (EUR 1 200) a gradual reduction to earnings is applied for the benefit calculation (see footnote in Table 1.1), but there is no upper earnings ceiling for pension accrual (Ministry for National Economy, 2017). For an individual earning HUF 500 000, this means that the pensionable income is HUF 479 300 (Table 1.1).

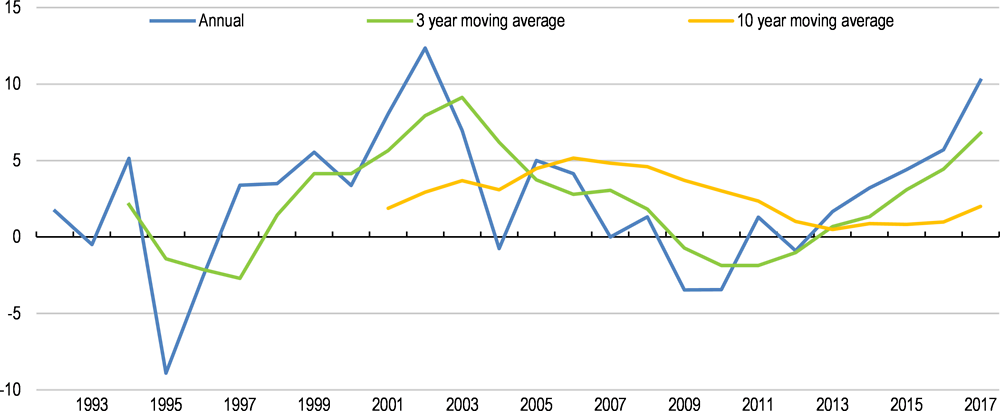

The large fluctuations in wage growth is translated into hard-to-predict variations in the monetary value of initial pension benefits as past wage developments are used to calculate the present-day value of earnings, whereas pension benefits received in retirement are indexed to prices, meaning that they do not follow wage developments. As a result, initial pension benefits vary for workers with similar wage careers but with different retirement years. Because real wages have risen by around 20% since 2016, someone who retires in 2018 will have a 20% higher initial pension than a 2016 retiree with a similar wage career. To increase predictability, authorities could benchmark against a moving average of real-wage developments, such as a ten-year moving average of wage growth, to take account of the business cycle, which would almost remove the fluctuations and ensure better predictability of future pension entitlements (Figure 1.2). To ensure transparency, the calculated average, whether using 10 years or another number, would need to be made public every year.

Table 1.1. Benefit calculations

% of average net earnings, unless otherwise stated1

|

|

Earnings-related |

Minimum pension |

Non-eligible for minimum <15 years’ service |

Early retirement (before 65 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

First 10 years of coverage |

33% |

No pension entitlement if < 15 years coverage, but an old-age allowance may be received (see next column). |

For a couple: allowance is 85% of minimum pension Single person < 75 years: 100% of minimum Singe person > 75 years: 135% |

nil |

|

11-25 years of coverage |

Add 2% per year worked |

After 20 years of service: HUF 28 500/month (unchanged since 2008) |

nil |

|

|

26-36 years of coverage |

Add 1% per year worked |

nil |

||

|

37-40 years of coverage |

Add 1.5% per year worked |

Available for women with at least 40 years' eligibility |

||

|

41 and above |

2% per year worked |

n/a |

||

|

Late retirement (working past statutory retirement age) |

0.5% per month worked after statutory retirement age |

n/a |

1. Earnings are valorised with economy-wide average earnings to the year preceding retirement. Pension benefits are adjusted to changes in the consumer price index. For higher levels of the accordingly calculated average valorised net wages (above a pre-set level – HUF 372,000 (around EUR 1,200) there is a progressive reduction to be applied. (Only 90% of the incomes between HUF 372,000 and 421,000 (around EUR 1,350), and 80% of the monthly incomes above 421,000 have to be taken into account). For instance, if the average monthly income is HUF 500,000, the pensionable average income is HUF 479,300. (372.000*100%+((421,000-372,000)*90%+(500,000-421,000)*80%).

Source: OECD (2017a), Pensions at a glance 2017: Country Profiles – Hungary; Freudenbert et al, "A Long-Term Evaluation of Recent Hungarian Pension Reforms", MNB working papers, 2016.

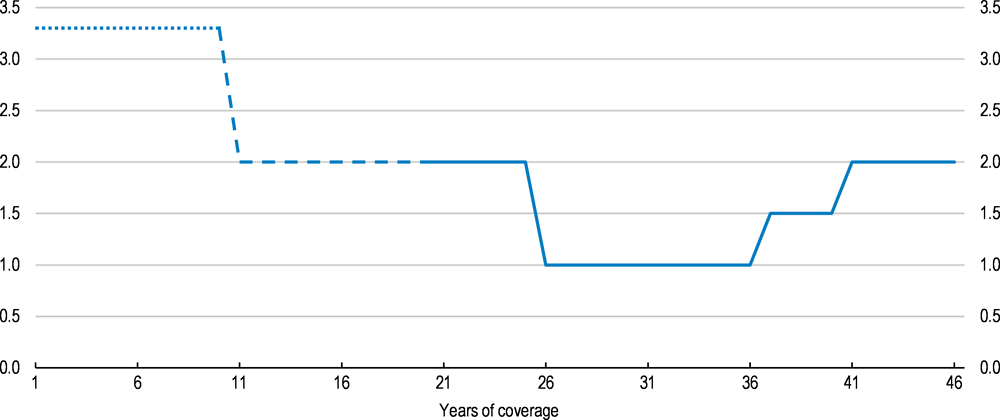

The accruals system is non-linear and rates vary with the length of the contribution period. The accrued rights are front-loaded the first 10 years, before gradually falling the next 26 years, where after they rise again until retirement (Figure 1.3). For workers earning the average salary throughout their career, the accruals system leads to a replacement rate (the ratio of initial pensions to last earnings) of 92% of the last salary after a career of 46 years.

The front-loading of accrued rights aims to reward workers with shorter careers, typically low-income groups. However, the non-linearity of the rates makes it difficult for individuals to fully assess the optimal time to retire (Fall and Bloch, 2014) (Blöndal and Scarpetta, 1999). A constant accruals rate of around 2% would enable workers to better calculate their accrued replacement rate, and is likely to keep budget expenditures unchanged while leading to similar pension outcomes for full-career workers. Across the OECD, only Hungary, Greece, Spain and Luxembourg have accrual rates that vary with service time. In addition, a Pension Monitor system would enable individuals to keep track of their expected pensions. A pension monitor enables employees to calculate their expected pension by entering details about salary, length of service and expected year of retirement; it may also offer additional services to help individuals manage their future pensions. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the Pensions Regulator hosts a website where employers, employees, pension insurers and pension providers can obtain advice, including about voluntary pension schemes (The Pensions Regulator, 2018).

Figure 1.2. Using a moving average for valorisation would smooth fluctuations

Year-on-year percentage change in real wages

Figure 1.3. Non-linear benefit accrual rates lead to less predictable pension outcomes

As a percentage of earnings1

1. The earnings-related pension is calculated as 33% of average earnings for the first ten years of coverage. Each additional year of coverage adds 2% from year 11 to 25, 1% from year 26 to 36, 1.5% from year 37 to year 40 and 2% thereafter. 20 years of service is required for both the earnings-related pension and the minimum pension.

Source: OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: Country Profiles - Hungary.

The increase in the accrual rates after 36 years aims to encourage workers to remain in the labour market. Moreover, there is a bonus pension increment of 0.5% for every month worked past the statutory retirement age without claiming the pension. After a year, the pension will therefore be increased by 6%, which is close to actuarial neutrality (OECD, 2017a) (Queisser and Whitehouse, 2006). This kind of pension bonus system is used elsewhere in the OECD (OECD, 2017a). However, public sector employees are not allowed to work beyond the statutory retirement age, for no clearly stated reasons. The rules should be applied evenly in the public and private sector although ending mandatory retirement altogether is not without controversy (OECD, 2017a). Employers in particular often argue that their businesses could not run as efficiently without it. Mandatory retirement is also a convenient mechanism for parting with unproductive workers. Ultimately, though, there is no reason why someone who still performs well be forcibly retired just because of age (OECD, 2017a). There are no data available on the number of people who defer pensions after retirement age (OECD, 2018a).

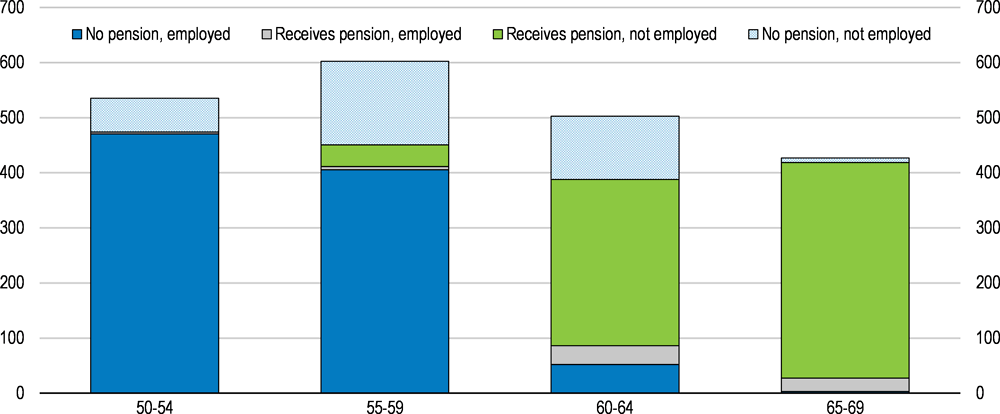

Other policy instruments are needed to flank the pension system in order to raise the effective retirement age, which is one of the fundamental requirement to ensure the long-term sustainability of the PAYG system, along with increasing the retirement age (Fall and Bloch, 2014). Increasing the employment rate of the above-55 also underpins the long-term projections in the EU’s Ageing Report, discussed below (Figure 1.4) (European Commission, 2017). The employment rate of workers aged 55-64 in Hungary is 52.7%, below the OECD average of 60.8%, although it rose by a third between 2011 and 2018 (OECD, 2018c).

Figure 1.4. Pensioners generally do not work after 65

In thousand persons, 20121

Note: Data refer to those persons who live in private households and who are either a) working at the time of the survey or b) not working at time of the survey but who did work after the age of 50.

Source: Eurostat (2018), "Transition from work to retirement", Eurostat Database.

Policies should focus on encouraging older workers to remain in the labour market until the pensionable age, and providing incentives to keep working beyond the pensionable age by deploying measures that promote the employment of older people, such as upgrading skills, providing appropriate help in finding jobs if unemployed, and encouraging employers to provide better suited working conditions and working-time arrangements (OECD , 2006), (OECD, 2016a) (OECD, 2018a). A recent survey shows that one-fifth of Hungarian pensioners would be willing to take a job provided employers offered flexible working conditions. More than half of those willing to work would take a part-time job, one quarter would work flexible hours, 10% would telework and only 10 % would take a full-time job (GKI, 2018). Current tax-incentives for employers who hire the long-term unemployed, women and older people could also be extended to the over-65s, especially in the SME sector (Zoltán, 2014) (OECD, 2016b) (Ministry of the National Economy, 2018) (Svraka, Szabó and Hudecz, 2014). From 2019, old-age pensioners who work will no longer pay social contribution taxes, only the personal income tax of 15%.

Other measures, such as phased retirement, with a partial withdrawal of pensions, might be beneficial for older workers as a way to smooth income and consumption. Some countries allow phased retirement, such as France (Box 1.2), but this is currently not possible in Hungary (OECD, 2016a) (OECD, 2018a). Past the statutory retirement age, it should also be possible to better combine pensions and work income. This is uncommon in the private sector, and in the public sector pension payments are suspended for people who continue to work past retirement age (OECD, 2017a).

Box 1.2. Flexible retirement schemes

An increasing number of workers surveyed in the EU would prefer to combine work and partial pension than to fully retire (Eurofound, 2016). Eleven countries currently allow this within the OECD: Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Japan, Norway and the United States. If people make pension contributions for work while receiving an early-retirement benefit, pensions are either recalculated each year to reflect these new contributions, or once the pension is eventually claimed.

Limitations and eligibility criteria for combining work and receiving early pension vary widely across countries. In France, for instance, there are two different schemes allowing to combine work and retirement:

Progressive retirement (Retraite progressive), pre-retirement: Wage and pension can be combined starting from the legal age of retirement (62 for the generation born in 1955) or the age of 60 for those who have contributed at least 150 quarters. The insured reduces the number of working hours (40% to 80% of effective work) and receives the corresponding share of wage combined with a share of old-age pension. The insured keeps contributing and pensions are recalculated to reflect these new contributions.

Accumulating work and pension (Cumul emploi-retraite), post-retirement: Someone who has retired can work and combine wage and pension without limit if the full-rate retirement conditions are fulfilled (legal retirement age + number of years of contribution; or legal age without penalties). Wage and pension can be combined up to a certain limit if the insured does not meet those conditions. In either case, working retirees do not earn additional pension entitlements.

The French programme, introduced in 2003 and reformed in 2009 to improve access, has been successful. In 2016, 478 000 people, 3.4% of French pensioners, were working whilst receiving some pension benefits. It has also helped boost the employment rate of those aged 60-64 which nearly doubled to 29.2% between 2007 and 2017.

Source: (OECD, 2013) (OECD, 2017a) (Musiedlak and Senghor, 2017) (INSEE, 2018).

Most forms of early retirement have been abolished

Early retirement for men, regardless of occupation, is no longer possible. Retiring because of disability is now subject to strict assessment, and benefits are no longer classified as pension (OECD, 2017a) (OECD, 2018a). However, early retirement remains possible for women with at least 40 years’ of eligibility, including periods in paid work or in receipt of maternity benefits, known as Women 40 (OECD, 2017a) (OECD, 2018a). The scheme has been popular, with early data indicating that as many as 80% of entitled women have chosen to retire (Freudenberg, Berki and Reiff, 2016). The system is not actuarially fair, particularly as women live longer than men (Queisser and Whitehouse, 2006).

The retirement age should be the same for men and women, with the possibility of taking early retirement with pension decrements, provided the system remains actuarially neutral (OECD, 2017a). Indeed, closing down the option of retiring early might involve an excessive degree of compulsion (Blöndal and Scarpetta, 1999), although a minimum retirement age needs to be established to avoid misuse of the system. The actuarially neutral decrement would subtract around 6% of pension entitlements for each year prior to the statutory retirement age; keeping the current increments of 6% for retirees who keep working, including in the public sector.

Truncated careers reduce pension entitlements

The design of the Hungarian pension system means that those with reduced lifetime earnings, such as the unemployed, late entrants into the labour market and, to a lesser extent, women who take maternity leaves, have smaller pensions (Fall and Bloch, 2014) (OECD, 2017b). (Czeglédi et al., 2016) (Domonkos and Simonovits, 2016). The unemployed accrue pension rights from the unemployment benefits, but the unemployment benefit period is limited to 90 days, the shortest in the European Union (European Commission Staff Working Document, 2018) (Kosa, 2012). Thereafter, the unemployed may receive the so-called job-seeker aid if they are less than five years away from retirement, but it does not accrue pension rights (OECD, 2017a). Younger unemployed may receive means-tested benefits, but they do not accrue pension rights.

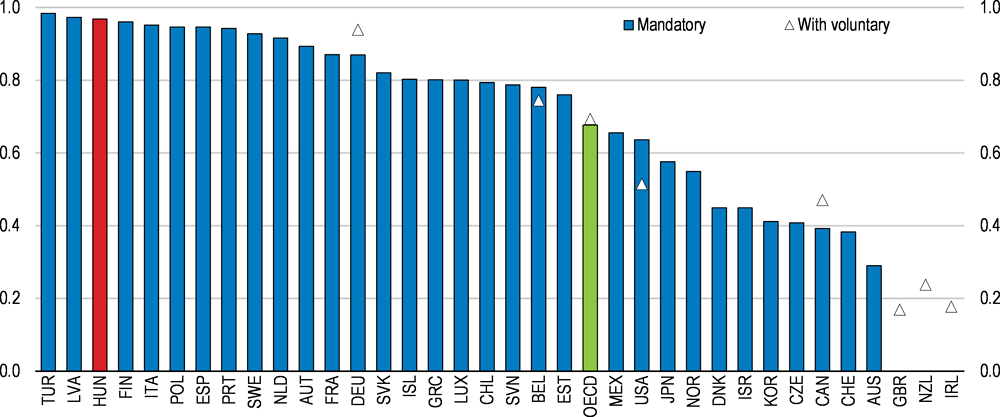

The negative impact of career breaks on pension entitlements is particularly strong in Hungary because of no other offsetting measures (OECD, 2017a) (OECD, 2017b). In a recent OECD-wide simulation of interrupted careers (late labour market entry and periods of unemployment lasting ten years), Hungary has the lowest pension outcome for individuals with career interruptions who face a shortfall of roughly 32% in pension benefits compared to the pay-out with a full career (Figure 1.5) (OECD, 2017b).

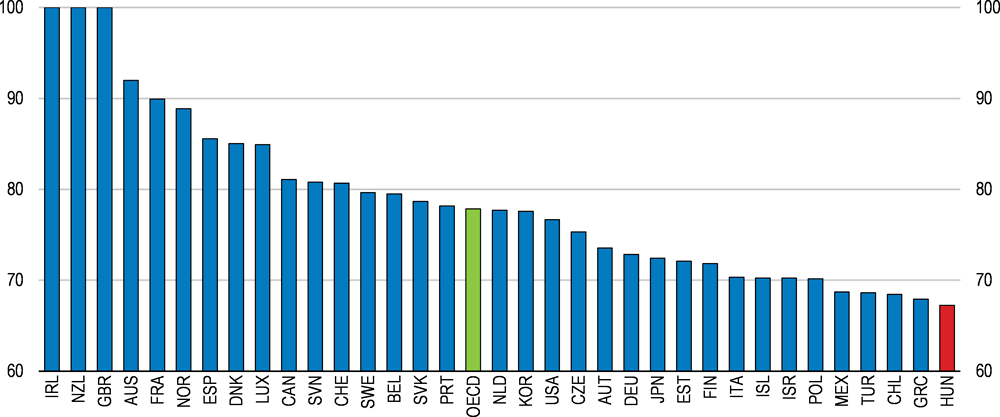

Figure 1.5. Workers with career interruptions have low pensions in Hungary1

Gross pension entitlements as a percentage of full-career entitlements, mandatory pensions only2

1. Pension entitlements are calculated for male average earners who enter the labour market at 25 years old (rather than the standard 20) and spend ten years unemployed between the ages of 35 and 45. What they would receive is measured against the OECD baseline pension, corresponding to a full career from the age of 20.

2. In Luxembourg and Slovenia labour-market latecomers with career gaps must work 5 years more than workers with unbroken careers to qualify for a full pension. The same figure is 4 years for France and 2 years for Germany and Spain.

Source: OECD (2017), Preventing Ageing Unequally, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Working women also face career interruptions if they have children. The gender gap in pensions has been comparatively low as women had similar participation rates as men prior to transition away from Communism (Figure 1.6). At present, the labour market participation rate (15-64 years) is 63.5% for women and 77% for men (European Commission, 2017). On average, men’s benefits are around 15% higher than that of women (including widows’ survivor pensions), and women face a higher risk of old-age poverty (European Commission, 2017) (Freudenberg, Berki and Reiff, 2016) (OECD, 2017a) (OECD, 2017c). Some of this may be caused by long maternity leaves, which can last up to three years per child (OECD, 2016b). Pension entitlements are accrued from maternity benefits, which in the third year falls to EUR 90 a month (OECD, 2017a).

Although women are allowed to work while receiving maternity benefits after six months, the lack of adequate childcare facilities means that many choose to stay at home (OECD, 2016b). This leads to lower accrued pension benefits over time (Ministry of the National Economy, 2018) (OECD, 2017c). However, new family tax allowance rules in place since January 2018 increase post-tax earnings of women after maternity, leading to better pension outcomes relative to men with the same initial wage career, provided the tax-benefit is used by the woman (for a couple, either spouse may use the deduction). To avoid eroding the tax base and to remain more actuarially fair, family allowances should be wholly cash-based.

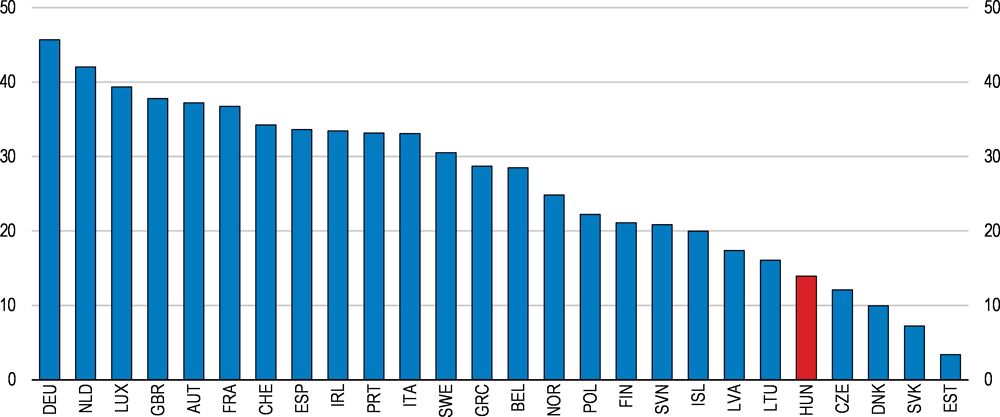

Figure 1.6. Gender gap in pensions is relatively low

In per cent, 65+ year-olds, 2014 or latest available1

1. 2013 for Austria, Denmark, Greece, Finland, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia and Spain. The gender gap in pensions is defined as: (1 - (women's average pension/men's average pension)) *100). 'Pensions' include public pensions, private pensions, survivor's benefits and disability benefits. The gender gap in pensions is calculated for people aged 65 and older.

Source: OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Despite the family allowance, long maternity absences combined with the Women 40 scheme that also shortens the contributory career may eventually lead to a widening of the gender gap in pensions unless corrective action is taken. Measures should be taken to shorten the maternity leave to durations seen in other European countries (around 12 months), while taking steps to improve the work-life balance for women, such as offering adequate childcare pre-kindergarten (OECD, 2016b) (OECD, 2017c).

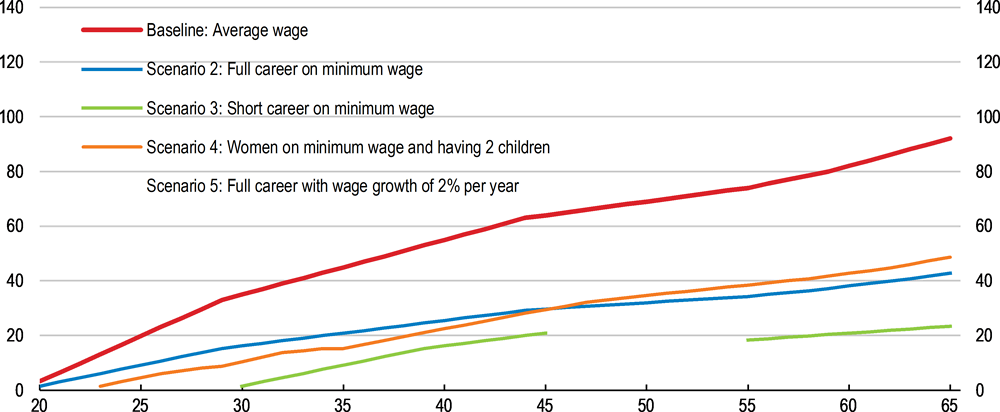

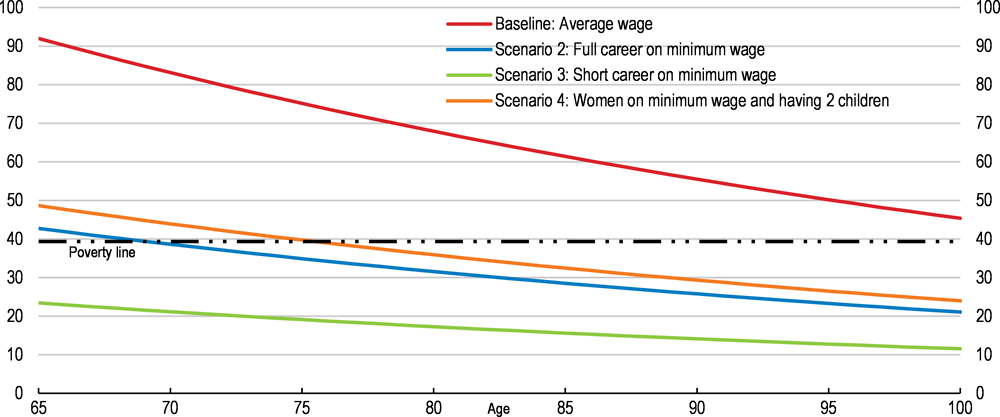

The earnings related pension system implies that truncated careers and low wages lead to relatively low pensions. OECD calculations show that the accrued pension, as a share of average incomes, for low-income earners and those with career interruptions are very low. For both groups, pensions are below 50% of average earnings by the time they reach retirement (Figure 1.7). A single mother with two children earning the minimum wage will benefit from the new income tax allowance, but even so her accrued pension will still be low compared to average earnings. An additional concern is that in retirement these low‑income earners rapidly fall into old-age poverty (see below). On the other hand, the system implies that those with a wage career may earn pensions well in excess of average wages by the time they retire.

Figure 1.7. Theoretical accrued monthly pension benefits

As a percentage of average monthly net salary1

1. Average net monthly earnings of full-time employees was HUF 197 516 in 2017. The baseline scenario assumes average wage for a career of 46 years from age 20. Scenario 2 assumes minimum wage for a career of 46 years. Scenario 3 assumes earning the minimum wage for a short career of 27 years, with a late entry to the labour market and ten years spent in unemployment. Scenario 4 assumes women having 2 children (with 3 years absence from the labour market after each birth) and earning the minimum wage for a career of 37 years. Scenario 5 assumes a full career with wage growth of 2% per year for 43 years, starting from average wage level, with later entry into the labour market, reflecting time spent in education.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from Hungarian Central Statistical Office.

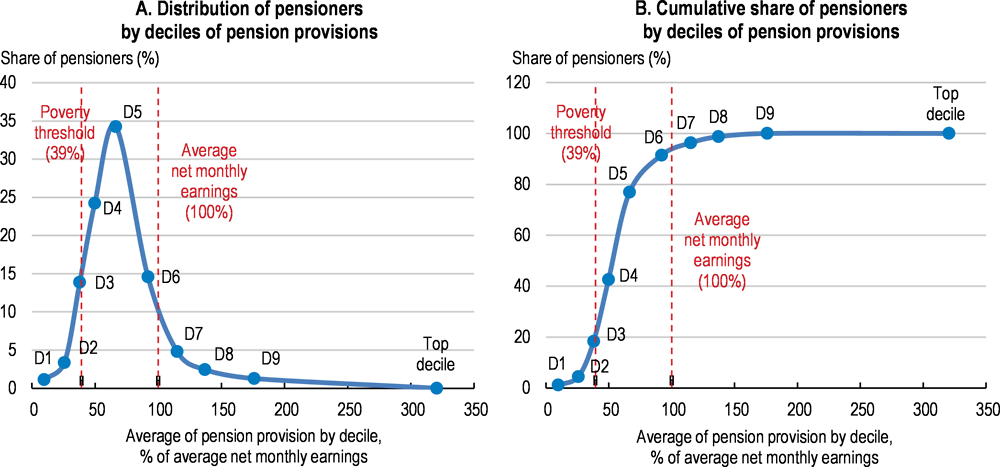

Old-age poverty is a concern

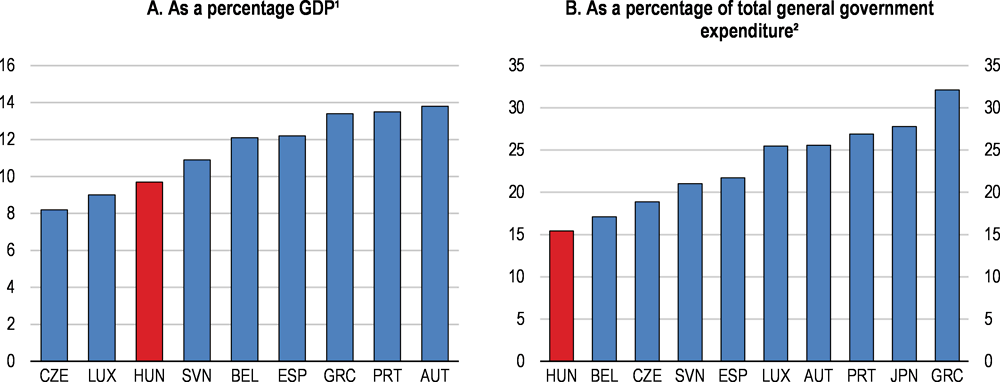

Currently, roughly 20% of pensioners receive pension benefits that are below the relative poverty threshold of HUF 77 500 a month (EUR 240; defined as half of the median wage). Even with additional in-kind benefits, 16.8% of the over-65s live in poverty or social exclusion (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2016). This is above the OECD average of 12.6% of all individuals over 65 who live in relative income poverty (Figure 1.8, Panels A and B) (Ministry of the National Economy, 2018) (OECD, 2015a). It results from several factors: many current pensioners retired with career interruptions caused by to the economic transition in the 1990s and subsequent economic crises, leading to low pension entitlements. In addition, workers with late labour market entry due to university studies or difficulty in finding a first job, and workers with career breaks accumulate lower pensions (OECD, 2017d). As a result, public expenditure on pensions is relatively low in comparison with countries with similar systems (Figure 1.9, Panels A and B). The average pension is HUF 129 637 (EUR 400). Approximately 66 000 old-age pensioners are not entitled to a pension. Moreover, 6 958 pensioners received social benefits because their income fell below the required minima in 2016. Low-income pensioners also have shorter life expectancies (Czeglédi et al., 2016).

Figure 1.8. The majority of pensioners receive pensions below average net wages

January 20181

1. Average net monthly earnings of full-time employees was HUF 197 516 in 2017. Panel A shows the distribution which indicates that just over 60% of all pensioners receive pensions that are below average net monthly earnings, with the largest share receiving around 75% of average earnings. Panel B sums the deciles.

Source: OECD calculations.

Figure 1.9. Public spending on pensions is relatively low

2016

1. The depicted countries all have mainly or solely a public defined benefit pension system.

2. Excludes early retirement benefits.

Source: European Commission (2018) 2018 Aging Report; OECD (2018), OECD National Accounts Statistics (database).

The current pension design replicates wage inequalities

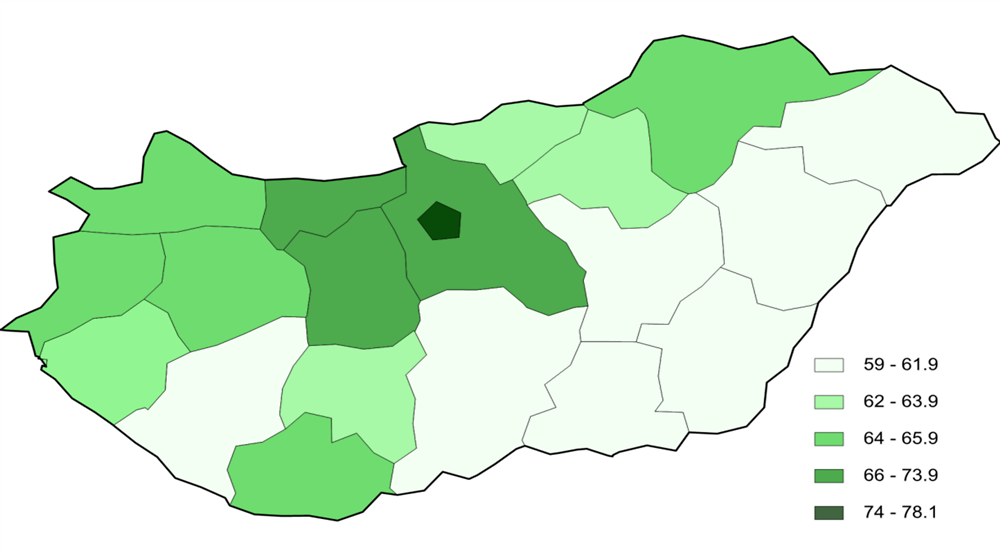

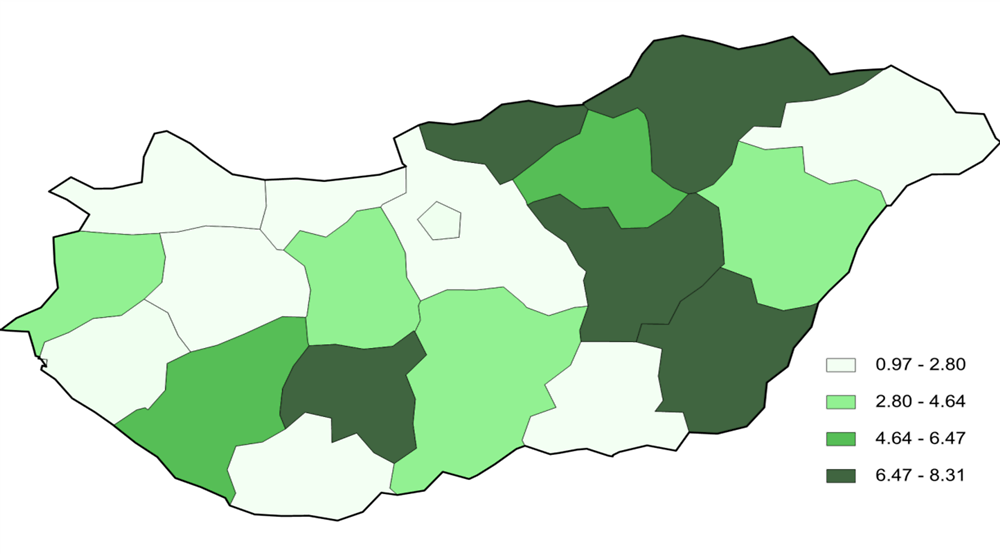

Because there is no universal or basic state pension, contrary to most public pension systems in the European Union, the pass-through of wage inequality in Hungary is higher than on average in the OECD (OECD, 2017b) (European Commission, 2018b). The average relative position of new pensioners in the overall pension income distribution is thus maintained after retirement. More than 85% of an increase in wage inequality is passed through into pensions, because of the low social safety net and absence of basic state pension (Figure 1.10) (European Commission, 2018b) (OECD, 2017b). This also translates into regional disparities in pension incomes, reflecting lifetime incomes (Figure 1.11) (see also Chapter 2).

Figure 1.10. Wage inequality leads to pension inequality

Percentage point change in the Gini index of pensions for a 1 percentage point increase in the Gini index of wages, full career case1

1. Data refer to gross (i.e. pre-tax) wages and pension benefits.

Source: OECD (2017), Preventing Ageing Unequally, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Price indexation contributes to old-age poverty

Other factors contributing to old-age poverty include the price-indexation rule which entails that the value of benefits will decline relative to wages over time (OECD, 2015a). The problem materialises quite fast owing to the low initial pensions for many wage earners. For instance, pensioners retiring at 65 after earning the minimum wage all their life will have an initial pension of less than 50% of average wages, and will fall into relative poverty before the age of 70, while a working mother with two children will fall into poverty ten years into retirement (Figure 1.12). To stay out of relative poverty, a worker needs to have had a full career without interruptions, and with wages close to the national average, in order to have accumulated a sufficiently large initial pension by the time they reach the statutory retirement age.

Figure 1.11. Regional distribution of pensions reflects regional income disparities

Average of full pension provision by county, as a percentage of net monthly earnings, January 20181

1. Average net monthly earnings of full-time employees was HUF 197 516 in 2017.

Source: Ministry of Human Capacities.

Figure 1.12. Low-wage earners fall into poverty within 5-10 years of retiring

As a percentage of average monthly net salary¹

1. Average net monthly earnings of full-time employees was HUF 197 516 in 2017. The baseline scenario assumes average wage for a career of 46 years from age 20. Scenario 2 assumes minimum wage for a career of 46 years. Scenario 3 assumes minimum wage for a short career of 27 years. Scenario 4 assumes women having 2 children (with 3 years absence from the labour market after each birth) and earning minimum wage for a career of 37 years.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from Hungarian Central Statistical Office.

Old-age poverty can be mitigated with a basic state pension

To alleviate old-age poverty and mitigate the pass-through effects from the earnings-related system, a basic state pension could be implemented for everyone who reaches retirement age. This would also include current recipients of the social safety-net benefits, as is the case for instance in the Nordic countries (OECD, 2015a). Countries with a basic state pension have fewer poor old-age pensioners (OECD, 2017d).

To assess the potential cost of a basic pension, OECD analysed three scenarios:

Extending the current minimum pension of HUF 28 500 to all current pensioners, regardless of accrued entitlements. The cost is negligible (at 0.01% of GDP), affecting roughly 18 500 people.

Doubling the minimum pension amount to HUF 57 000 for all current recipients who receive below this amount. This would cost 0.04% of GDP, affecting 67 300 people.

Providing a basic pension equivalent to the current relative poverty level of HUF 77 500, helping 218 500 people and costing around 0.15% of GDP, compared to total public expenditure on pensions which stands at 9.7% of GDP (European Commission, 2018c).

A basic pension could potentially be financed through a ceiling on pension benefits. For example, based on data on the distribution of current pension benefits, a ceiling on today’s pensions equivalent to 150% of average economy-wide net earnings (roughly EUR 910) would fully fund proposal (2), a basic state pension of HUF 57 000. However, the same ceiling would only fund one-third of the cost of a higher state pension set at the relative poverty line. Currently 19 OECD countries impose a cap on pension benefits, with an average ceiling at 184% of average economy-wide earnings (OECD, 2015a). Voluntary pension schemes allow for topping up pensions (see last section). A cap on the highest pensions could be matched by a cap on contributions for actuarial fairness, as is the case in several OECD countries such as Slovakia or Canada for instance (OECD, 2017a), but the present calculations do not include this aspect.

Offering a state pension may adversely affect the labour market by eroding incentives to work and contribute, given how long it would take to accrue the same amount of pension from working. In the current system, to earn equivalent pension entitlements as in proposal (2) (HUF 57 000), a worker on the minimum wage would have to work for 25 years. Nonetheless, the mandatory pension scheme would still allow them to accrue at least one‑third more in benefits by working a full career under current rules. To be fully poverty‑alleviating, the basic state pension may be additional to the normal pension accrual, in which case the labour market distortions would be less important while the fiscal costs would be considerably higher.

Demographic trends will put pressure on public spending on pensions

The population is ageing and shrinking

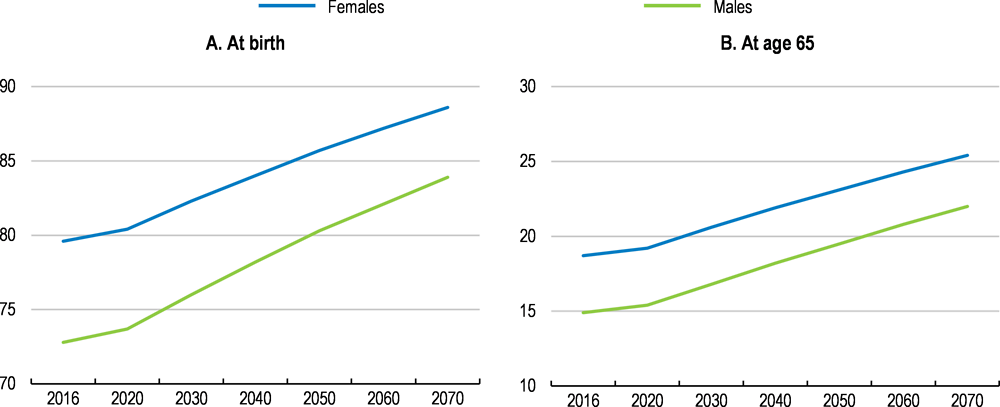

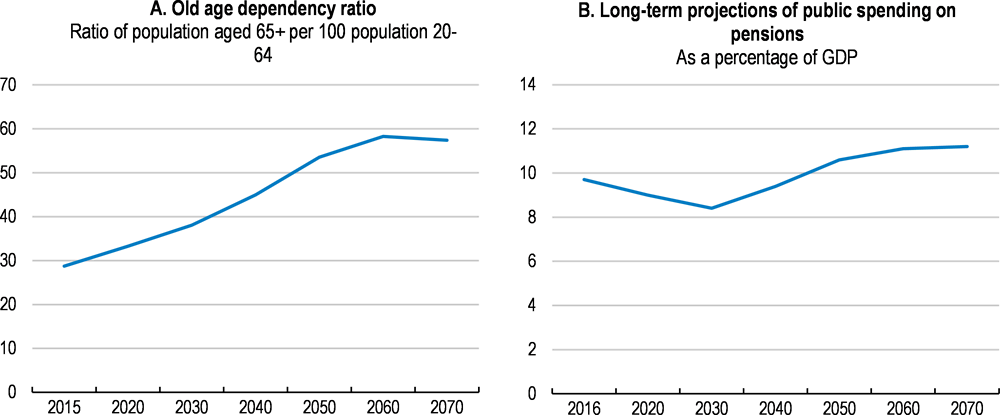

Demographic developments will put pressure on the PAYG system. The population is ageing and shrinking, eroding the contribution base, while life expectancy is presumed to increase by 10 years by 2070 (Table 1.2) (European Commission, 2018b). There are two waves of ageing with the first large post-war generation currently entering retirement and another wave starting after 2030, leading to a doubling of the old-age dependency ratio to 52% over the next 50 years, partly caused by a drop in the working-age population of 11.1% (Figure 1.13, Panel A and Panel B) (Figure 1.14) (European Commission, 2018b).

Table 1.2. Main underlying assumptions for the long-term pension projections

|

|

2016 |

2030 |

2050 |

2070 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demographic projections |

||||

|

Population (million) |

9.8 |

9.7 |

9.3 |

8.9 |

|

Prime age population (25-54) as % of total |

41.9 |

38.8 |

34.1 |

34.0 |

|

Elderly population (65 and over) as % of total |

18.5 |

22.2 |

28.2 |

29.1 |

|

Old-age dependency ratio (20-64)1 |

29.8 |

38.2 |

53.7 |

57.3 |

|

Macroeconomic assumptions |

||||

|

Potential GDP (growth rate) |

1.9 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

|

Employment (growth rate) |

1.7 |

-0.2 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

|

TFP (growth rate) |

0.7 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

|

Labour force assumptions |

||||

|

Labour force (20-64) (thousands) |

4 587 |

4 677 |

4 053 |

3 760 |

|

Participation rate females (20-64) |

68.0 |

78.5 |

78.5 |

78.6 |

|

Average effective exit age (total)2 |

61.7 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

|

Employment rate (20-64) |

71.6 |

79.3 |

79.3 |

79.4 |

1. Old-age dependency ratio=Population aged 65 and over as % of the population aged 15-64 or 20-64.

2. Based on EC calculations of the average probability of labour force entry and exit observed. The table reports the value for 2017.

Source: European Commission (2017), The 2018 Ageing Report, Underlying Assumptions and Projection Methodologies, Institutional Paper 065, November 2017.

Figure 1.13. Life expectancy is rising, including for pensioners

In years

Source: European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic & Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)", Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Institutional Paper 079, May, Luxembourg.

Ageing-related spending is estimated by the EU commission to decrease by 1.3 percentage points of GDP until 2030, and then to increase by 2.8 percentage points of GDP between 2030 and 2070 (Table 1.3) (European Commission, 2018b). The initial decline in pension spending hinges on a somewhat optimistic assumption that the effective and statutory retirement ages will become fully aligned by 2025 (Figure 1.15). If this fails to materialise, ageing-related cost‑increases may be even higher. Other factors which may increase spending would include changing the indexation of benefits to mitigate old-age poverty, provided this is implemented, and the cost of the Women 40 scheme. Pension contributions, meanwhile, are projected to fall over time, leading to a deterioration in the balance between projected spending on pensions and projected contributions of 2.7% of GDP by 2070 (Table 1.3).

Figure 1.14. The active population will be shrinking, while the share of pensioners will increase

As a percentage of total population by gender1

1. Data refer to baseline projections.

Source: Eurostat (2017), "Population on 1st January by age, sex and type of projection", Eurostat Database.

Table 1.3. Main policy scenarios and projections

% of GDP unless otherwise indicated.

|

|

Avg ch 16-70 |

2016 |

2020 |

2025 |

2030 |

2035 |

2040 |

2045 |

2050 |

2055 |

2060 |

2065 |

2070 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Potential Real GDP (growth rate) |

1.6 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

2.4 |

2.1 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

|

Average effective exit age (Total) |

3.3 |

61.7 |

62.8 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

|

Average effective exit age (Women) |

3.8 |

61.0 |

62.4 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

64.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public pensions, gross as % of GDP |

1.5 |

9.7 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

8.4 |

8.6 |

9.4 |

10.3 |

10.6 |

10.8 |

11.1 |

11.2 |

11.2 |

|

Public pensions, contributions as % of GDP |

-1.0 |

9.4 |

8.3 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.5 |

|

Gross replacement rate at retirement % (Old-age earnings-related pensions) |

3.7 |

45.5 |

46.1 |

46.0 |

47.6 |

48.3 |

49.3 |

48.4 |

48.9 |

48.7 |

48.6 |

49.2 |

49.2 |

|

Benefit ratio |

-7.7 |

40.4 |

37.1 |

34.8 |

32.8 |

31.8 |

32.0 |

32.6 |

32.3 |

32.0 |

32.0 |

32.3 |

32.7 |

|

Average contributory period, years (new pensions, earnings-related) |

4.7 |

32.8 |

34.5 |

35.0 |

37.2 |

37.6 |

37.8 |

37.1 |

37.4 |

37.4 |

37.6 |

37.9 |

37.5 |

|

Scenarios that differ from the baseline (evolution of public pensions, gross as % of GDP)

|

|||||||||||||

|

High life expectancy (+2 years) unchanged retirement age |

2.1 |

9.7 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

8.5 |

8.7 |

9.6 |

10.6 |

10.9 |

11.2 |

11.6 |

11.7 |

11.8 |

|

Lower fertility (-20%) |

3.4 |

9.7 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

8.4 |

8.6 |

9.5 |

10.6 |

11.1 |

11.6 |

12.2 |

12.7 |

13.1 |

|

Higher TFP growth (+0.4 p.p.) |

0.6 |

9.7 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

8.4 |

8.5 |

9.1 |

9.9 |

10.0 |

10.1 |

10.3 |

10.3 |

10.3 |

|

Lower TFP growth (-0.4 p.p.) |

2.6 |

9.7 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

8.4 |

8.7 |

9.7 |

10.8 |

11.3 |

11.7 |

12.1 |

12.3 |

12.3 |

|

Policy scenario linking retirement age to increases in life expectancy |

-0.1 |

9.7 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

8.2 |

8.4 |

8.7 |

9.4 |

9.8 |

9.7 |

9.7 |

9.6 |

9.6 |

Source: European Union, Ageing Report 2018, cross-country tables, AWG data base.

Figure 1.15. The old-age dependency ratio is rising and will peak in 20601

1. Data are based on the technical assumptions by the EU AWG, i.e. convergence towards the EU mean.

Source: Eurostat (2017), "Population on 1st January by age, sex and type of projection", Eurostat Database; and Ministry for National Economy (2018), "Magyarország konvergencia programja 2018-2022".

Benefit ratios will keep falling, increasing the risk of poverty

Benefit ratios (pension benefits as a share of wages) are projected to decrease by 7.7 percentage points to 32.7% (Table 1.4), because of the spread between wage growth and consumer price inflation, although the drop is less steep than in Poland or in Slovakia. Falling benefit ratios increase the risk of older pensioners lacking sufficient incomes relative to wage earners, which will be exacerbated in periods of higher wage growth (Simonovits, 2014). Moreover, the EU’s Ageing Report’s main underlying assumption is income convergence towards the European mean. However, increased productivity growth, which is a pre-requisite for income convergence, would in fact widen the wedge between replacement rates and benefit ratios (European Commission, 2017).

Table 1.4. Benefit ratios and replacement rates in Europe

Public pensions: earnings-related

|

Benefit ratios |

Replacement rates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2016 |

2070 |

2016 |

2070 |

|

|

Czech Republic |

39.9 |

37.6 |

43.1 |

41.1 |

|

Hungary |

40.5 |

32.7 |

45.5 |

49.2 |

|

Poland |

52.3 |

21.6 |

61.4 |

23.0 |

|

Slovenia |

34.1 |

33.3 |

34.7 |

35.7 |

|

Slovakia |

44.8 |

33.5 |

49.0 |

50.2 |

|

EU27³ |

45.2 |

33.2 |

46.3 |

38.1 |

|

EA³ |

48.5 |

35.8 |

49.9 |

41.2 |

1. The ‘Benefit ratio’ is the average benefit of pensions as a share of the economy-wide average wage.

2. Baseline scenario. The ‘Replacement rate’ is calculated as the average first pension as a share of the average wage at retirement; to allow comparisons, the figure reported here includes only earnings-related public pensions.

3. EU, EEA: Unweighted average, EU 27 excludes the United Kingdom.

Source: European Commission (2018), The Ageing Report 2018, Economic and budgetary projections for the 27 EU Member States (2016-2070), 6/2018, Brussels.

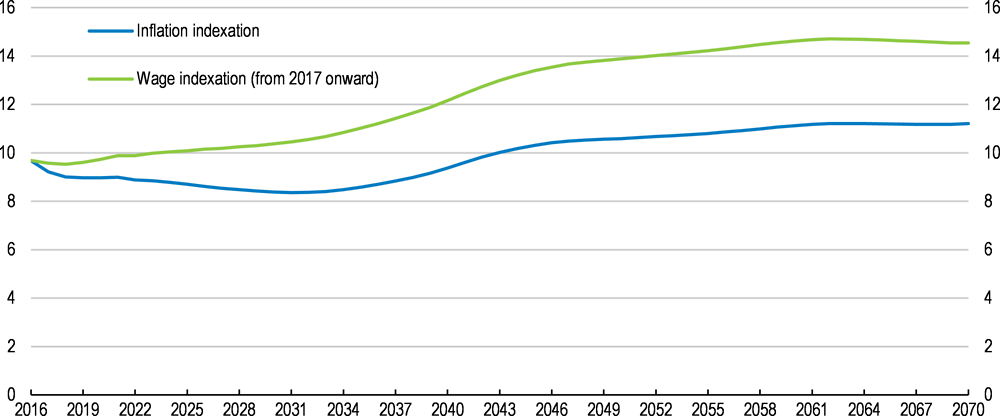

A number of OECD countries maintain benefit ratios by linking pensions to wage-growth, or to a weighted index between wages and prices, rather than to CPI. OECD calculations indicate that full wage-indexation would add 3 percentage points of GDP to public pension spending to the projected increase in the Ageing Report (Figure 1.16) (European Commission, 2018b) (Ministry of the National Economy, 2018). To reduce the budgetary cost, the indexation could use an even share of price and wage developments which would slow the erosion of the benefit ratio, but would nonetheless increase public spending on pensions.

Figure 1.16. Difference in cost between indexing pension benefits to wages and to inflation

Public pension expenditure, as a percentage of GDP

Source: OECD calculations based on European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic & Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)", Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Institutional Paper 079, Luxembourg.

The Women 40 scheme will widen the financing gap

The Women 40 scheme will further increase pressure on the PAYG scheme. The longer retirement period for women and the absence of any pension deduction increase expenditures without a concomitant reduction in benefits (Freudenberg, Berki and Reiff, 2016). Moreover, the average age of female retirees is still below that of males, while the assumptions in the EU Ageing Report are based on a projected exit age of 65.1 for both men and women (Table 1.4) (European Commission, 2017). However, if 80% of women continue to retire after 40 years of working, the amount of social contributions could be reduced by around 0.6% of GDP, according to OECD calculations, widening the funding gap more than currently assumed. As such, the Women 40 scheme should be abolished in favour of having the same retirement age for men and women, boosting the contribution base and improve actuarial fairness.

Table 1.5. The effective retirement age is going up, but remains lower for women

Average age at awarding of the benefit.

|

Old-age pension |

Women with 40 years’ service |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year of retirement |

male |

female |

female |

|

|

2012 |

62.7 |

59.2 |

57.8 |

|

|

2013 |

62.3 |

59.6 |

58.0 |

|

|

2014 |

62.9 |

59.6 |

58.3 |

|

|

2015 |

62.8 |

60.0 |

58.7 |

|

|

2016 |

63.1 |

61.0 |

59.0 |

|

Source: Central Administration of National Pension Insurance: Statistical yearbook 2015, 2014 and Statistical pocketbook 2016.

Financing the spending increases

Altogether, the pension funding gap may be higher than currently assumed by almost 4% of GDP, if measures to mitigate poverty and the effect of the Women 40 are included. Other deviations from the baseline will also increase spending above current projections, including lower fertility, or lower growth than currently assumed (Table 1.6). Within the existing pension system, three parameters can be activated to finance some of the projected increases in pension spending without any other offsetting measures: increasing the pension age; lowering pension benefits through a lowering of accrual rights, or through pre-funding in the form of a buffer fund.

Table 1.6. Risks to projected public pension expenditure

Increases in public pension expenditure above baseline scenario in 2070, % of GDP, unless stated otherwise

|

Changes to the baseline scenario |

Avg change 16-701 |

20702 |

|---|---|---|

|

Higher life expectancy than projected (+2 years), unchanged retirement age |

2. |

10.6 |

|

Lower fertility by -20% |

3.4 |

1.9 |

|

Lower TFP growth (-0.4 p.p.) |

2.6 |

1 |

|

Indexing pension benefits to inflation |

4.5 |

3.0 |

|

Women 40 (reduction in contributions) |

- |

0.6-0.8 |

1. Total estimated change in public expenditure from 2016 to 2070, in % of GDP. 2. Increase in public expenditure above the baseline.

Source: European Union, Ageing Report 2018.

Raising the statutory pension age by linking it to life expectancy once the current pension reform (which raises the retirement age to 65 by 2022) has been completed, would keep spending broadly constant as a share of GDP over time, compared with the baseline scenario, but would still leave a funding gap (Table 1.5) (European Commission, 2017). An additional effect of longer work lives would be to increase contributions. For example, OECD calculations find that raising the number of contributory years by five years would increase total contributions by 1.1% of GDP, sufficient to cover the remaining funding gap (Table 1.17).

Funding the increase in projected spending can also be achieved by lowering replacement rates. To cover the financing gap, the average replacement rate would have to be lowered (through reductions in accrual rights) by some 8 percentage points. However, this would further exacerbate the risk of old-age poverty.

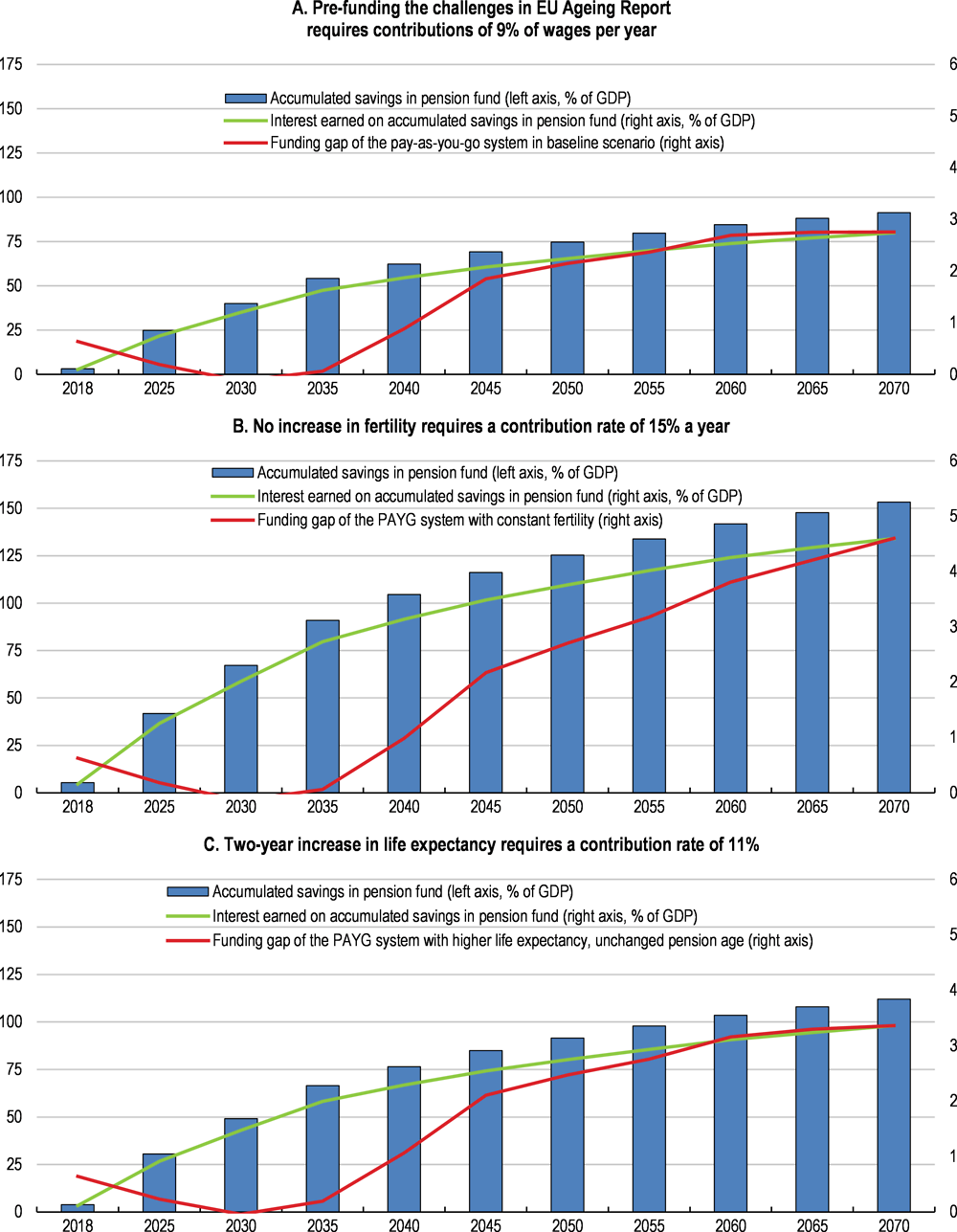

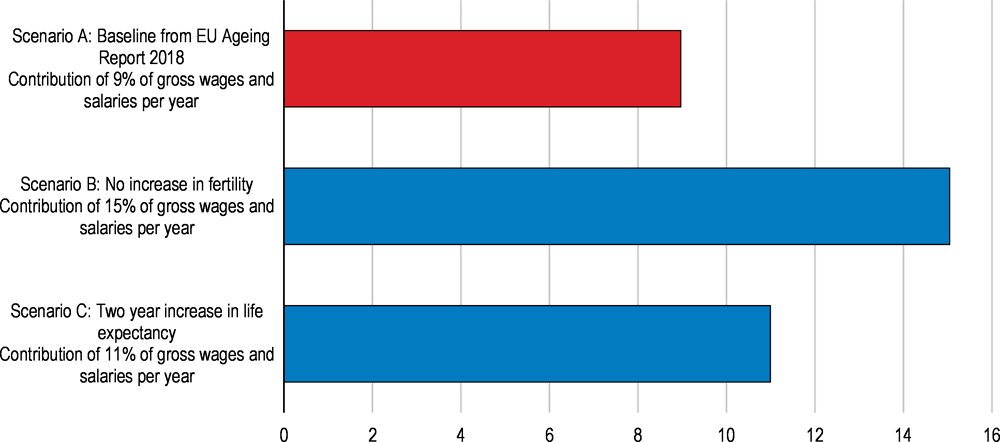

Pre-funding of pensions is also an option. OECD calculations based on the assumptions of having to plug a funding gap of 2.7% of GDP by 2070 (from the EU Ageing Report projections) show that the creation of a pension savings or “buffer” fund with a mandatory contribution rate of 9% of wages and salaries would fully cover the projected gap between pension spending and contributions by 2070. This would raise the current contribution rate by 30%, more or less matching reductions in the social security contributions since 2016 (Figure 1.17 and 1.18, baseline scenario). More optimistic demographic assumptions, such as a gradual two-year increase in life expectancy, leads to a higher contribution rate if there is no adjustment in the pension system’s parameters, as people remain in retirement for longer. On the other hand, if the expected increase in fertility fails to materialise then pre-funding could require an almost doubling of the contribution rate to make up for a smaller contribution base (Figure 1.17, Panels B and C).

Figure 1.17. Pre-funding future pension spending requires higher contributions

Calculations showing required savings to meet projected pension spending needs in 2070

Note: The figure shows a model calculating how much would need to be saved into a savings-fund to be able to pre-fund the gap between contributions and pension spending by 2070. The model aims to demonstrate the required magnitude of contributions in order for the interest earned on the accumulated savings to be sufficient to pay the cost of future pensions. Scenarios are taken from the EU Ageing Report 2018. The calculations are based on the following assumptions: contributions into the savings fund start in 2018; the accumulated savings are multiplied with the interest rate of 3.5% every year; an annual pay-out to pensioners of 3% of the accumulated savings is applied from 2035 onwards. The funding gap refers to the projected shortfall in pension contributions relative to pension spending in 2070 in the PAYG system, as per EU Ageing Report Projections.

Source: OECD calculations based on European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic & Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)", Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Institutional Paper 079, Luxembourg.

Figure 1.18. Potential pension contributions to a pre-funded buffer fund match recent reductions

As a percentage of gross wages and salaries¹

Source: OECD calculations based on from European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic & Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)", Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Institutional Paper 079, Luxembourg.

With full mandatory enrolment, the first option with additional contributions of 9% of gross wages, would effectively slightly more than reverse the recent reductions in social security contributions (European Commission, 2018a) (Ministry of the National Economy, 2018). Opting instead for auto-enrolment typically sees 60-80% coverage, based on the experience in countries such as the UK. Creating a pension buffer fund to pre-fund future pension liabilities will benefit future retirees, but at the expense of current workers who will pay more tax. Creating a pension fund would finance new entitlements and ensure that the PAYG system remains sustainable in the long term. However, a pension buffer fund cannot finance past entitlements. Moreover, it would erode wage competitiveness by raising current contributions.

Voluntary savings can boost pension benefits

Overall pension benefit adequacy can be supported by an effective voluntary or mandatory private savings scheme to increase old-age income. For instance, Australia, Denmark, Iceland and Norway have highly targeted programmes, using mandatory private pension provisions to top up public pensions, while Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States have the best pension coverage provided by voluntary schemes (OECD, 2017a).

The third pillar of voluntary pension savings has a comparatively low take-up. Assets in all retirement vehicles represent 5.9% of GDP, and 4.3% of GDP for the state-backed pension fund, the lowest share in the OECD (OECD, 2018d). At present, the third pillar system provides three options for savings: a state-backed voluntary pension fund; a pre-pension savings scheme entirely invested in securities; or pension insurance (portfolio investment, which pays out an annuity upon retirement, typically indexed to life expectancy). In total, some 1.7 million Hungarians have some form of voluntary pension savings, with the state-backed voluntary scheme taking the lion’s share with 1.1 million accounts in 2017.

The schemes used to be attractive as the employer’s contributions to their employees’ voluntary savings were tax exempt. Since 2009, ever-changing rules have made the schemes less attractive, and at present, the total tax burden on contributions is 40.71%, which is payable by the employer. This has substantially reduced employers’ contributions.

All three schemes qualify for tax-benefits for employees, equivalent to a 20% refund of income tax paid into the pension account up to a limit. The tax refund ceiling is HUF 130,000/year (EUR 420) for those retiring before 2020, otherwise it is HUF 100 000 for individual retirement accounts; HUF 150 000 for voluntary private pension funds and HUF 130 000 for pension insurance schemes (OECD, 2015b). Individuals may combine several accounts but the total tax refund cannot exceed HUF 280 000 a year. There does not seem to be any meaningful reason for the various rates, and the tax incentives should be aligned and equalised for all schemes. Subsidies should be limited, with voluntary pensions being instead subject to the standard taxation of savings instruments (OECD, 2014a).

To be a useful complement to PAYG pensions, two main issues need to be addressed: low financial literacy and enrolment. Unless enrolment is automatic (with the possibility of opting out), as in the United Kingdom for instance, the take-up of voluntary pension schemes tends to be low. Due to higher savings capacity and financial literacy among advantaged socio-economic groups, voluntary pension coverage is heavily biased in favour of workers with high earnings (OECD, 2017b). Voluntary pensions might therefore magnify the tax exemptions for the better-off, and as a result tend to increase old-age inequality. When coverage is low as in Hungary, then in the special case of low-income earners incentives such as targeted matching contributions or a flat introductory bonus contribution should be used to encourage their participation of low-income earners within well-designed auto-enrolment schemes (OECD, 2014a) (OECD, 2017b).

Flat-rate subsidies and matching contributions have been used in for example Italy, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Turkey. Incentives could also target financial assistance towards lower income individuals (OECD, 2016a) (OECD, 2017b). Irrespective of targeting, such measures often carry substantial fiscal costs, and should always be only temporary. However, the scale of the pension challenges means that policy action across many different policy measures is required and that policy actions are needed as early as possible.

Table 1.7. Fiscal cost and funding of key recommendations on pensions

|

Recommendations with potential fiscal impact |

Impacts on fiscal balance |

|---|---|

|

Link the retirement age to life expectancy |

Pension spending is projected to increase by 2.7%. Linking the statutory retirement age to gains in life expectancy after 2022 would fully cover the projected long-term increase. An increase of 5 contributory years would add 1.1pp of GDP in pension contributions. |

|

Combat old-age poverty by introducing a basic state pension at HUF 57000 (twice the current minimum pension). |

+0.04% of GDP. Expense would be fully covered by capping maximum pensions at 150% of average wages. |

Source: OECD.

Box 1.3. Main recommendations on pensions

Key recommendations are bolded

Ensuring sustainability of the pension system

Complete the ongoing increase of the statutory retirement age to 65 by 2022. Thereafter link it to gains in life expectancy.

Abolish the Women 40 scheme.

Taking steps to alleviate old-age poverty

Introduce a basic state pension to guarantee a minimum income for all pensioners.

Improving the design of the current system

Impose a single flat accruals rate of around 2%.

Implement flexible retirement, with a symmetrical system of actuarially neutral pension increments and decrements of around 6% a year, including for public employees.

Provide incentives for participation in third pillar voluntary pension funds through targeted temporary matching contributions or a flat introductory bonus contribution.

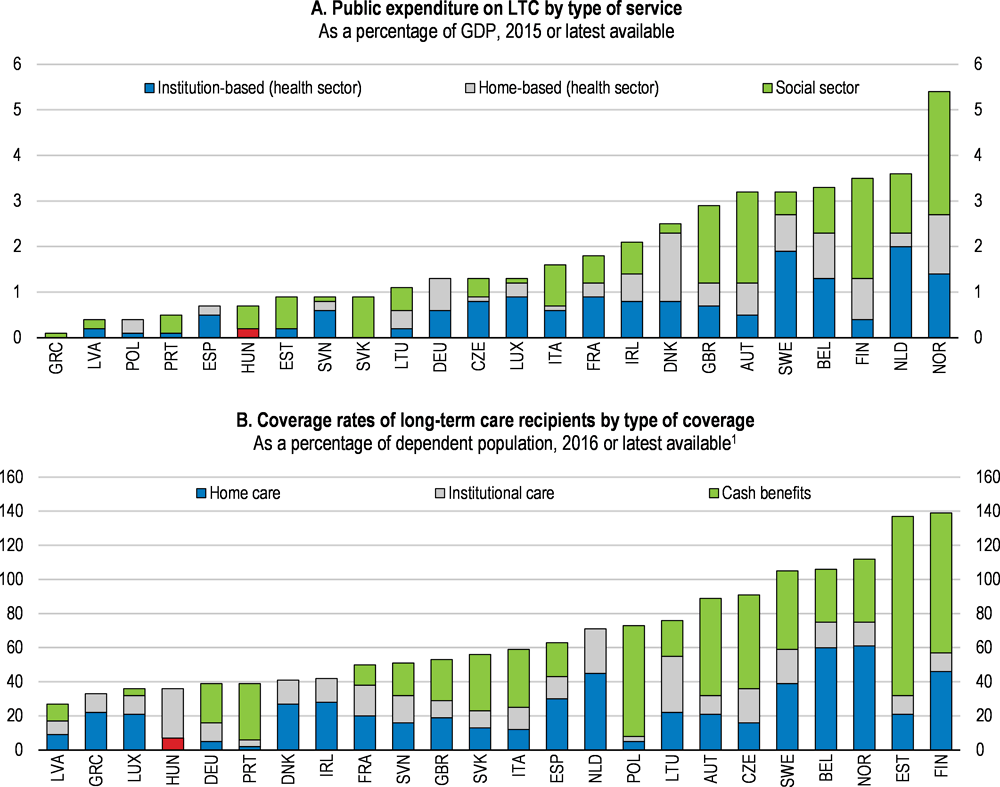

The health sector is facing multiple challenges

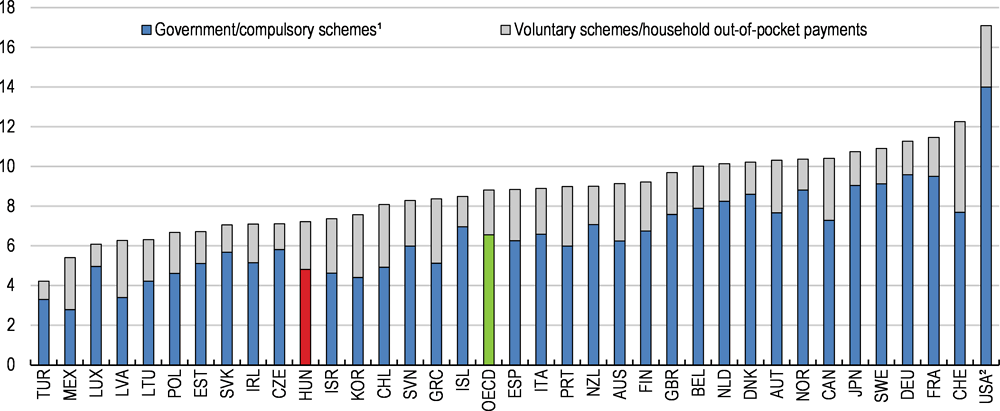

Hungary’s health-care sector is facing multiple challenges, including the generally poor health status of the population, unequal access to health services (particularly in rural areas) and rising health needs from an ageing population, including more treatment for chronic conditions. Moreover, health-care costs are rising and will continue doing so as new and expensive technologies is introduced. Ageing will also increase demand for long-term care (LTC). So far, health-care reforms have been modest. There has been limited restructuring of the hospital sector despite the ongoing urbanisation process (Chapter 2). Moreover, only recently have measures been taken to address a shortage of health care professionals, reflecting the emigration of health care workers. Earlier decentralisation reforms have subsequently been reversed (Box 1.4). More generally, the public health care system has been underfunded and is therefore characterised by persistent hospital debts and an increase in the market share of private health care providers. Total health care expenditure has stagnated since the mid-2000s while public spending on health care has fallen relative to GDP (Figure 1.19).

Box 1.4. The organisation and governance of the health care sector

The widening gap in health status between Hungary and Western European countries by the early 1990s led the first government after the transition to begin reform of the health care system. The ownership and administration of service providers, such as hospitals, were devolved from the central to local governments. The financing was based on a single insurance model (Gaál, 2004). However, the combination of strong focus on cost-containment since the mid-1990s and a lack of coherent long-term strategy have hampered further reforms.

Due to unfavourable macroeconomic condition and ever increasing pharmaceutical spending, the focus of health policy shifted towards cost-containment in the mid-1990s (Gaál, 2004). Health care spending has been unstable ever since with short spending sprees and extended periods of cost-containment and budget cuts (Gaál et al., 2011). The economic crisis in the second half of 2000s reinforced the austerity measures in the health sector.

In the second half of the 2000s, the role of the private sector was increased to enhance the efficiency and funding of the health care system. However, reform initiatives to introduce managed competition of multiple health insurers as well as outsource the provision of health services to private companies failed due to political and public objection (Gaál et al., 2011).

In recent years, the direction of health policies turned towards re-centralisation. To address chronic inefficiencies and regional inequities in health care provision, the central government’s role in terms of governance has been strengthened since 2012. Currently, policy formulation, rule enforcement and all financial and budgetary decisions are controlled by the central government (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017). Health care is administered by the State Secretariat for Healthcare within the Ministry of Human Capacities. The leading health care agency within the Ministry is the National Healthcare Services Centre (NHSC), which is an umbrella organisation of other (formerly independent) agencies and it is responsible for hospital planning and care coordination, among others (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017).

The ownership structure of the health care system has also been centralised. The provision of inpatient and outpatient specialised care and the ownership of hospitals have been transferred back to central government (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017). After having lost its self-governance status in 1998, the National Health Insurance Fund Administration (NHIFA) was dissolved into the Ministry of Human Capacities altogether in early 2017 (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017). As a result, the NHIFA lost its autonomy and only kept its administrative functions, while its traditional role of hospital supervision became the responsibility of NHSC. The financing structure of the health care system has changed considerably since the mid-2000s. The decrease in employers’ health insurance contribution to the Health Insurance Fund (HIF) has been accompanied by an increase in budgetary contributions. Since 2012, employers’ contributions have been replaced with a non-earmarked social contribution tax. The current model is a hybrid between a financing structure where insurance rights are acquired through social security contributions and a general taxation based model where all citizens are entitled to health care that is financed from the budget.

Figure 1.19. Health care spending has been relatively low

As a percentage of GDP, 2017

1. Public health spending refers to health spending by government schemes and compulsory health insurance. In the case of Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, spending by private health insurers for compulsory insurance is also included in public health spending. The OECD average is an unweighted average of all 36 member countries.

2. Data for USA are for 2016.

Source: OECD (2018), "Health Expenditure and Financing", OECD Health Statistics (database).

Health outcomes are characterised by low health status and large disparities

Notable strengths of the health-care system include near universal health-care coverage and high vaccination rates for communicable diseases. Nonetheless, health outcomes are unsatisfactory. The share of avoidable deaths in the light of current medical knowledge and technology among the population below 75 at 41% is almost 10% above the European Union (EU) average. Indeed, according to the latest poll by Ipsos among 28 countries surveyed Hungarians are by far the most worried about the state of the health care system with 71% of the adult population responding that health care is the most worrying topic (Ipsos, 2018).

The level of health spending partly explains this poor situation; indeed, according to some estimates, if health expenditure were increased to the Austrian level (from 8% to 10% of GDP), then male mortality is estimated to fall by about 13% (Lackó, 2015). However, inefficient care provision is also an important driver of unsatisfactory health outcomes.

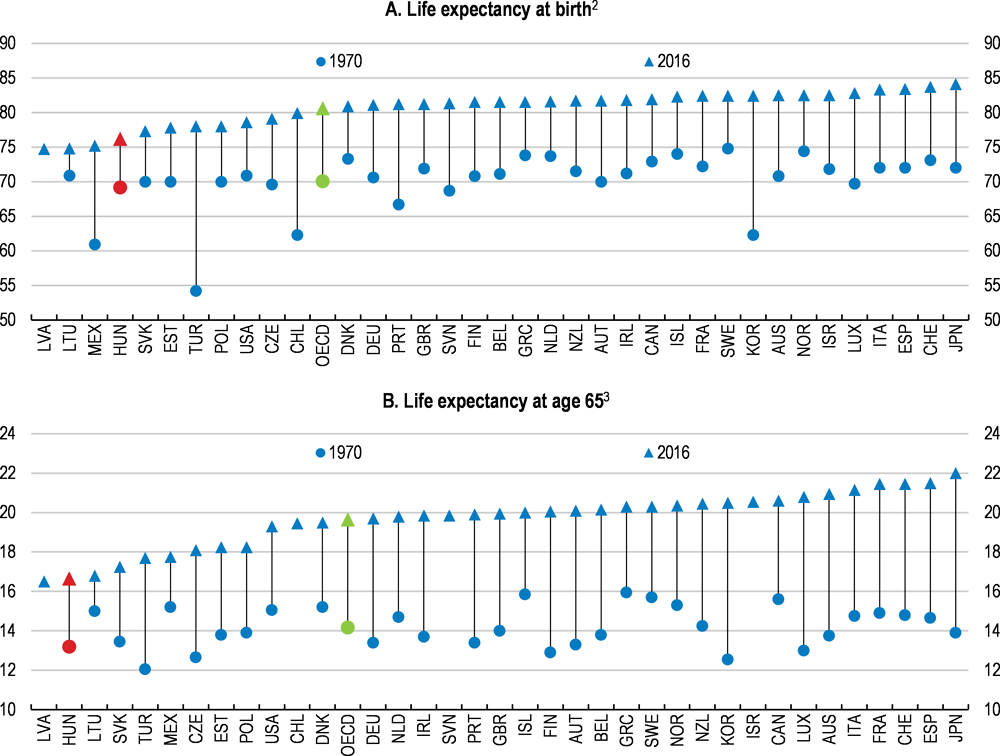

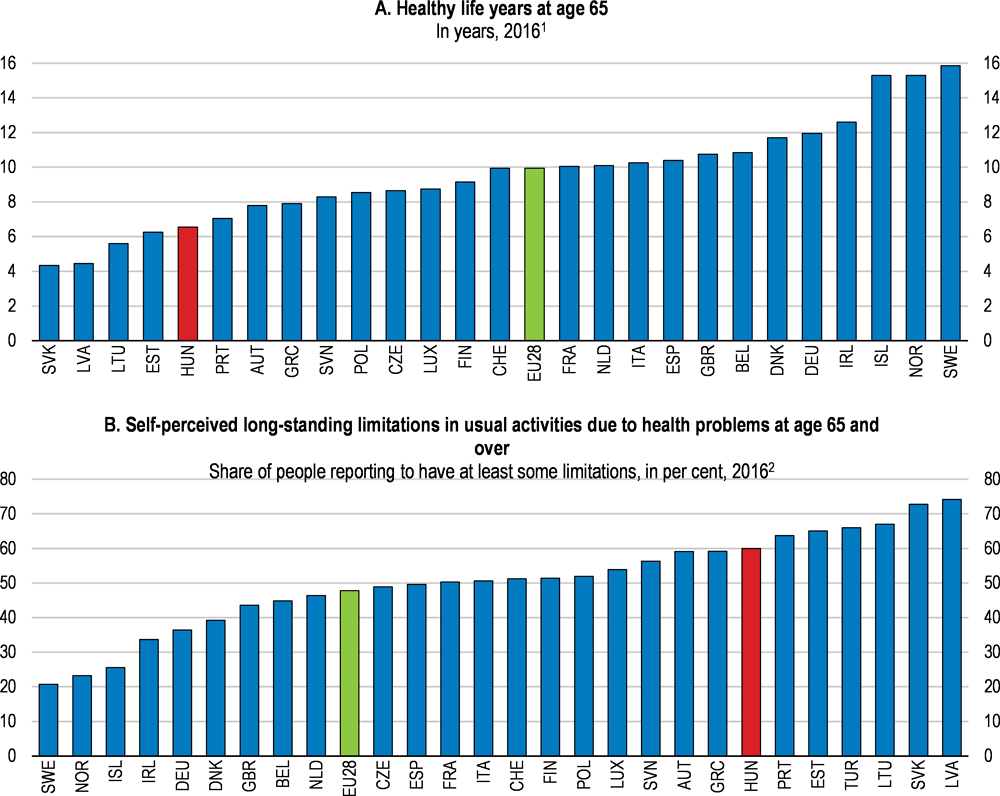

Life expectancy at birth is the fourth lowest among OECD countries (Figure 1.20, Panel A). Similarly, remaining life expectancy at age 65 is internationally low despite recent improvements (Figure 1.20, Panel B). This reflects one of the highest mortality rates in the OECD, which is mainly driven by death from diseases of the circulatory system and cancer. Furthermore, disparities in life expectancy is larger than elsewhere with 30-year old male tertiary-education graduates expected to live 11 years longer than similarly-aged males with below-upper secondary education – a gap that is 4 years higher than on average among OECD countries. In addition, regional differences in health outcomes have been increasing since the mid-1990s, leading to a 3-year gap in life expectancy at birth between the richest region, Central Hungary, and the relatively poor Northern Hungary (Orosz and Kollányi, 2016; Uzzoli, 2016) (ÁEEK, 2016).

Figure 1.20. Health status of the population is poor in international comparison

In years1

1. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

2. 2015 instead of 2016 for Canada, Chile and France. 1971 instead of 1970 for Canada, Israel, Italy and Luxembourg.

3. 2015 instead of 2016 for Canada, Chile and France. 1971 instead of 1970 for Canada, Finland, Italy and Luxembourg. Life expectancy at age 65 is calculated as the unweighted average of the life expectancy at age 65 of women and men.

Source: OECD (2018), "Health Status", OECD Health Statistics (database).

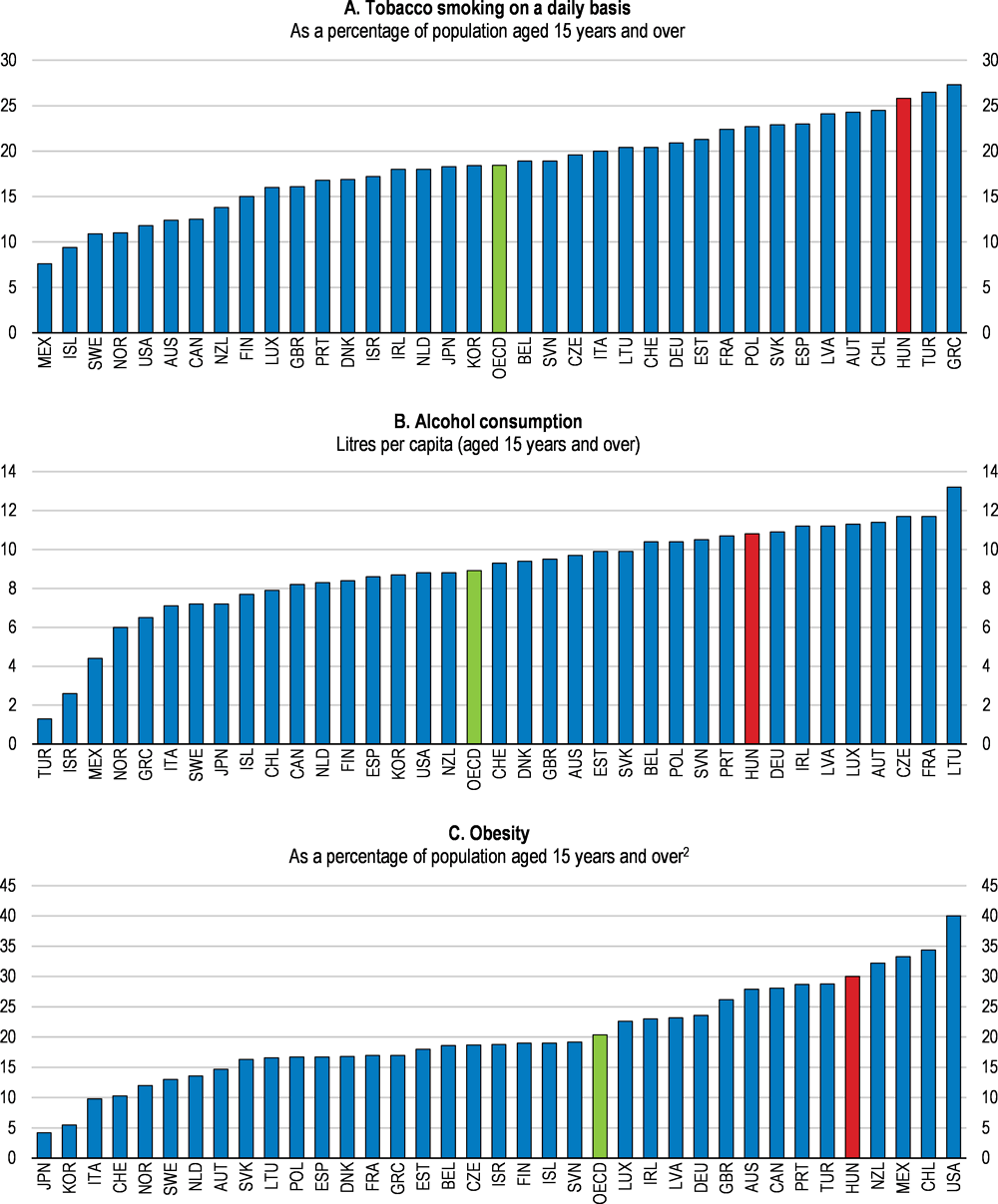

Lifestyle factors have a greater negative impact on life expectancy than elsewhere in the OECD. Almost 40% of overall life years lost due to diseases and disabilities is linked to unhealthy lifestyles (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017). This is the fourth highest share in the EU. Hungarians are among the heaviest smokers in the OECD and alcohol consumption is nearly a quarter higher than the OECD average (Figure 1.21, Panels A and B). In addition, the 30% obesity rate is one of the highest among OECD countries (Figure 1.21, Panel C). Unhealthy lifestyles are partly a reflection of little focus on preventive care. Spending per capita on preventive care, including public health promotion programmes, has fallen by nearly 40% in real terms since the mid-2000s. In the past, ambitious public health programmes have often been watered down at the implementation phase (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017).

Figure 1.21. Lifestyle related health risks are high

2017 or nearest year available1

1. Data for tobacco smoking and obesity for Hungary refer to 2014. Data for alcohol consumption for Hungary refer to 2015. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

2. Self-reported data for Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. Measured estimates derived from health examinations are generally higher and more reliable than estimates derived from population-based health interview surveys.

Source: OECD (2018), "Non-Medical Determinants of Health", OECD Health Statistics.

The resources invested in health care are not used efficiently

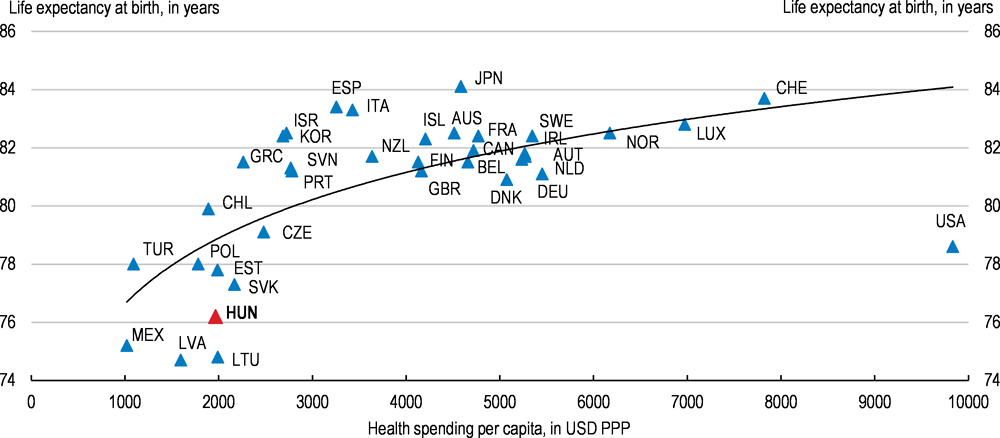

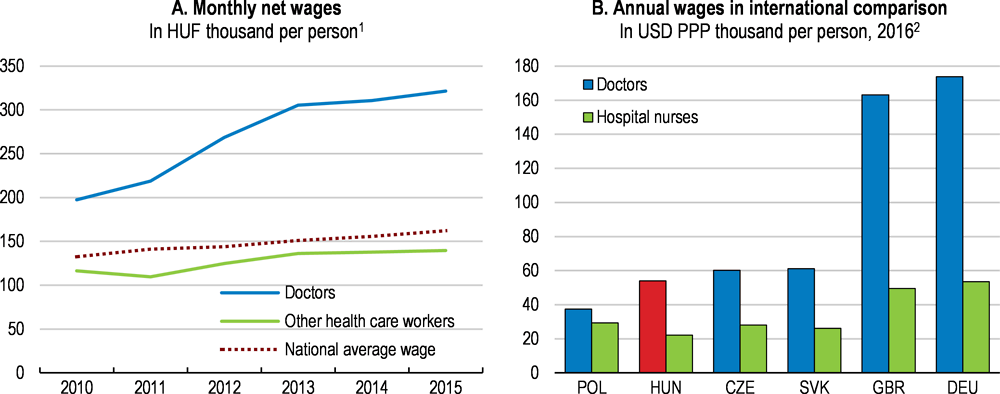

If the efficiency of resource utilisation was raised to the level observed in other OECD countries with similar health spending per capita, life expectancy could be raised by around 3 years (Figure 1.22). Moreover, if spending efficiency was aligned to the most efficient health care system in the OECD, it is estimated that amenable mortality could be reduced by more than 60%, boosting life expectancy by 5 years (Medeiros and Schwierz, 2015; Dutu and Sicari, 2016). The health care system is also underperforming relative to countries with similar health policies and institutions (Joumard, André and Nicq, 2010).

Figure 1.22. Better resource utilisation could boost life expectancy significantly

2016 or nearest year available1

1. 2015 for life expectancy at birth for Canada, Chile and France. PPP: purchasing power parity.

Source: OECD (2018), "Health Expenditure and Financing", OECD Health Statistics (database), July; and OECD (2018), "Health Status", OECD Health Statistics (database).

Reorganising health care provision would improve efficiency

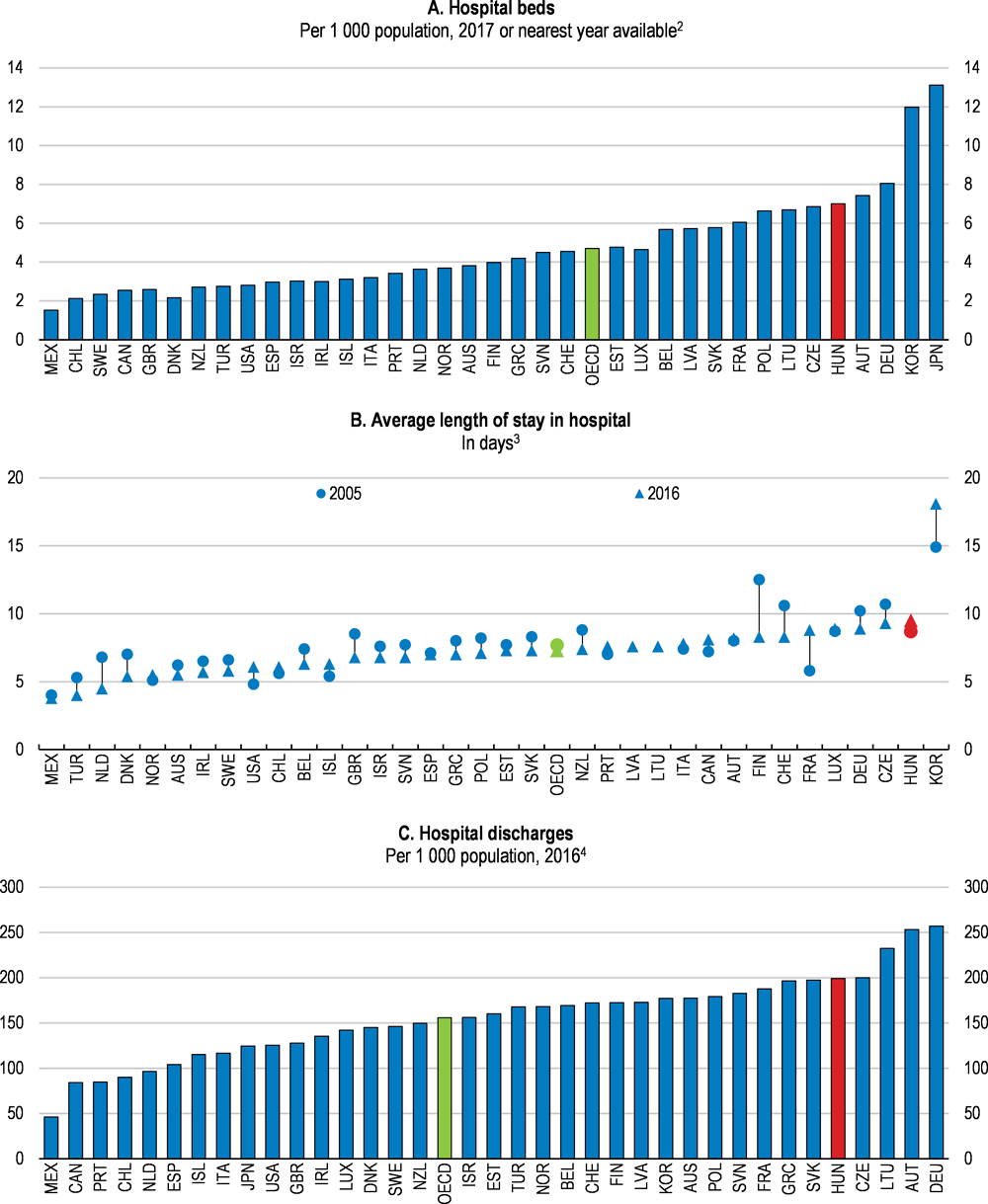

Health-care provision remains highly hospital-centred, despite a 30% decrease in the number of acute care hospital beds since 2000 (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017). However, the reduction in acute care beds has been mainly achieved by transforming acute care units into chronic care departments. Indeed, closing under-performing hospitals has proven to be politically difficult (Gaál et al., 2011). Since 2006, only a few hospitals have been closed down while some have been transformed into long-term care institutions (Krenyácz, Kiss and Révész, 2017). As a result, the number of hospital beds remains above the OECD average and the average length of hospital stay has increased to 9.5 days (Figure 1.23, Panels A and B). High hospital-discharge rates (a measure of overall hospital activities through the number of patients who leave a hospital after staying at least one night) also indicate an overuse of hospital-based inpatient care (Figure 1.23, Panel C).

Figure 1.23. Health care provision is highly hospital-centred1

1. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

2. 2016 for Hungary.

3. 2015 for Australia, New Zealand, Norway and Portugal. 2014 for the United States. 2012 for Greece.

4. 2015 for Australia, New Zealand, Norway and Portugal. 2014 for Japan. 2012 for Greece. 2010 for the United States.

Source: OECD (2018), "Health Care Resources", OECD Health Statistics (database); and OECD (2018), "Health Care Utilisation", OECD Health Statistics (database).

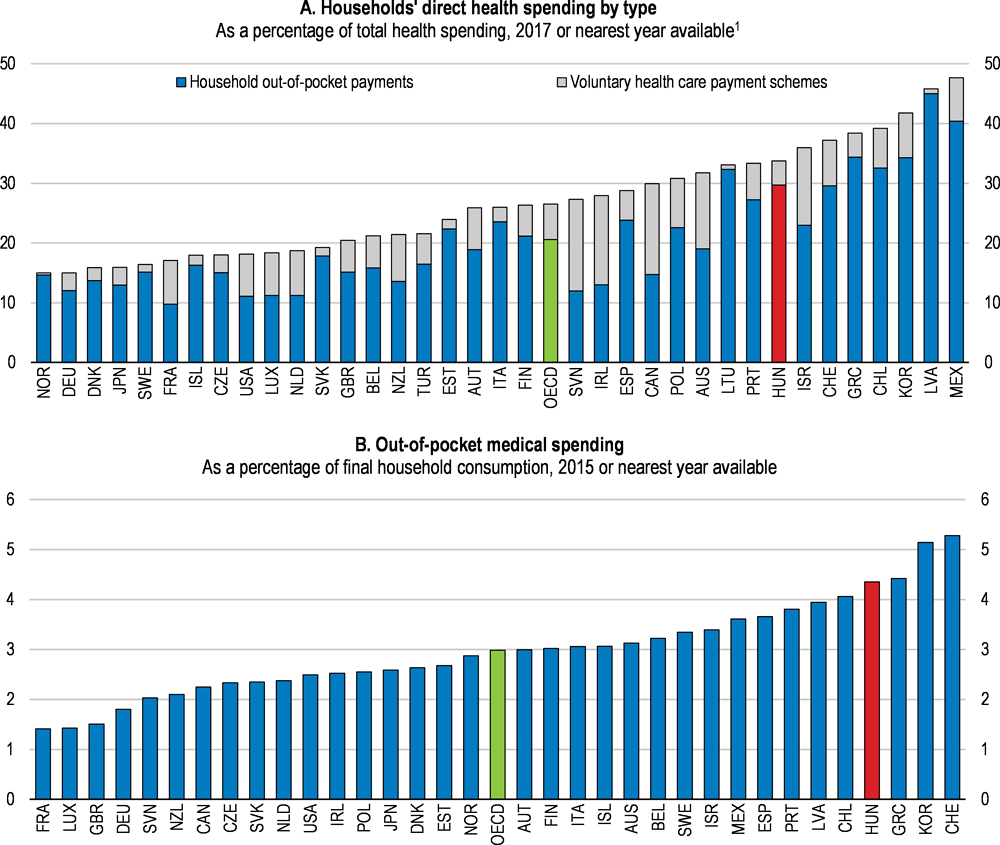

The hospital sector should be restructured, like in other OECD countries, by having fewer but better equipped hospitals that focus on complex cases, requiring high levels of specialised and technical care, and leave all other services to less resource intensive care settings (OECD, 2017d). Some progress in this direction is planned with the implementation of the Healthy Budapest Programme over the coming years. More generally, closing under-performing hospitals would release financial resources that could be invested in replacing obsolete medical equipment. Indeed, the number of high technology medical equipment, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units and computed tomography (CT) scanners, per capita is one of the lowest among OECD countries.