Recent macroeconomic developments and short-term prospects

Solving the legacies of the crisis by buttressing the financial system and public finances

Addressing medium-term challenges for wellbeing

OECD Economic Surveys: Ireland 2018

Key Policy Insights

Abstract

The Irish economy continues to grow rapidly and has come a long way since exiting the EU-IMF financial assistance programme in late-2013. In the subsequent years, nominal measures of national income have grown by over one-third. The labour market, which is probably the best barometer of economic trends at present, has shown a decline in the unemployment rate from above 15% to close to 6%. At the same time, Ireland continues to outperform other OECD countries in many non-income indicators of wellbeing, such as personal security, environmental quality and the strength of social connections.

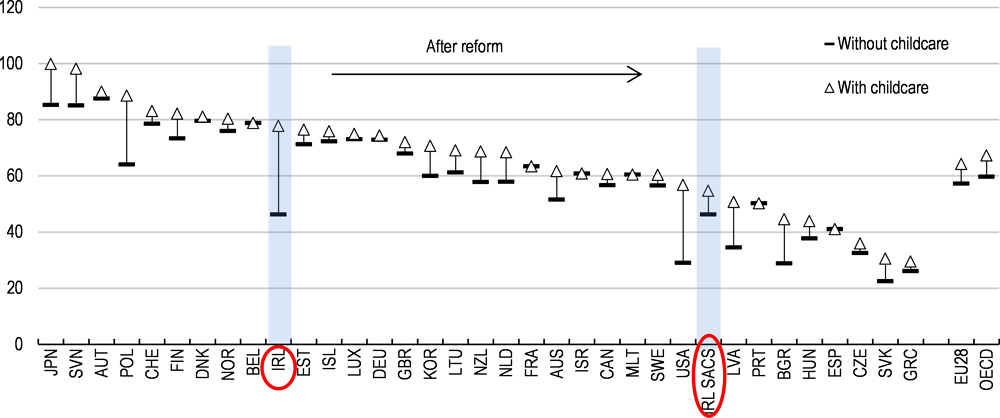

The economic recovery has benefitted from past reforms. New measures have focused on changes to the budgetary framework and macro-prudential policies which have safeguarded the economy against a new banking and fiscal crisis. Barriers to employment have also been reduced by improving job creation schemes, ongoing reductions in childcare costs and lowering marginal tax rates for low-income households.

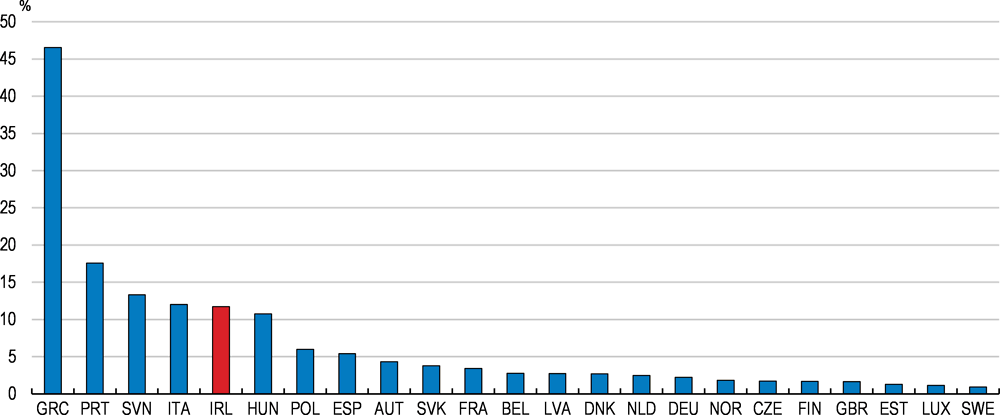

Both public finances and the stability of the financial sector have also improved in recent years. With heightened uncertainty relating to the United Kingdom’s planned departure from the European Union (“Brexit”; Figure 1) and potential reductions in corporate tax rates in other countries, such progress is welcome. Yet, the ability for the economy to absorb a fresh economic shock is threatened by public debt per person remaining one of the highest in the OECD and a large stock of non-performing loans lingering on bank balance sheets.

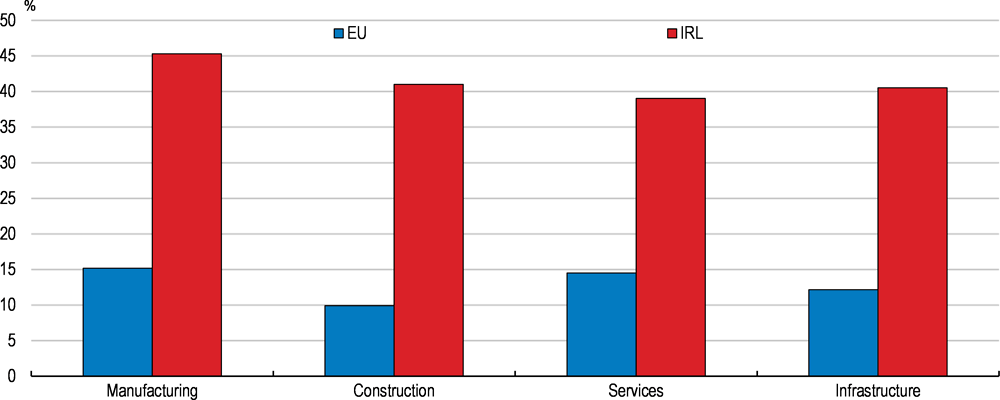

Figure 1. Many Irish firms believe they are negatively exposed to Brexit

Proportion of firms expecting a negative impact from Brexit.

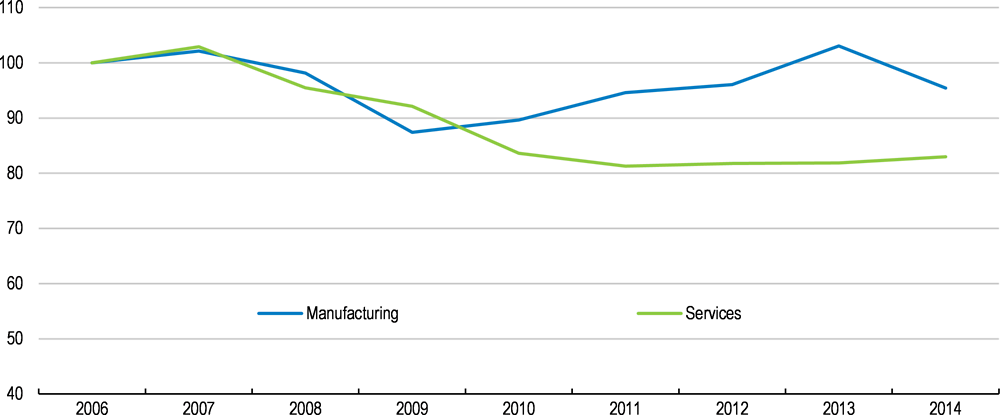

Resilience to future shocks is also weakened by underlying fragilities in the economy. Aggregate productivity has been rising in recent years, but this has owed to the performance of some large foreign-owned companies. New firm level analysis, undertaken in tandem with this Economic Survey, highlights that the majority of firms in Ireland experienced a decline in productivity between 2006 and 2014 (Figure 2). Consequently, a critical question to further raise living standards in Ireland is how to enhance the productivity of local Irish firms. This is the focus of the thematic chapter of this Economic Survey and the growth-impact of some of the related reform recommendations are quantified in Box 3 (further below).

Figure 2. Most businesses have experienced a decline in productivity

Median firm productivity (Index 2006 = 100)

Note: The firm level analysis using OECD MultiProd is explained in more detail in the thematic chapter. The figure above shows multifactor productivity (using the Solow method) of the median firm in the productivity distribution at each point in time. These results are consistent with labour productivity estimates based on both micro and macro data.

Source: Department of Finance (2018a).

There are other medium-term challenges to wellbeing on the horizon. With the population likely to expand notably over the coming years, pressures will mount on the health system and existing infrastructure. Furthermore, unless inclusive-minded reforms are undertaken, the burden of these pressures may disproportionately fall on lower-income households. Such pressures need to be addressed while ensuring that pro-cyclical budgetary policy is avoided.

Against this backdrop, the main messages of this Economic Survey are:

The resilience of the economy to future shocks needs to be buttressed by improving the stability of public finances and the financial system.

Creating the conditions for sustainable productivity growth of local firms is critical to supporting future Irish living standards.

While Ireland is a rich country with a highly redistributive tax and transfer system, there are several areas where wellbeing could be improved over the medium-term, including the supply of housing, water infrastructure, health services and labour market participation.

Recent macroeconomic developments and short-term prospects

The Irish economy has continued to grow robustly over the past four years. The recovery from the crisis was initially driven by exports due partly to improved cost-competitiveness (OECD, 2015). Subsequently, growth has also been supported by domestic demand. The strength of underlying economic activity has been difficult to gauge over the past two years due to some distortions in the headline national accounts measures (Box 1). Nonetheless, estimates of underlying domestic demand, which exclude volatile components related to the activities of multi-national enterprises (MNEs), grew by around 5% in 2016.

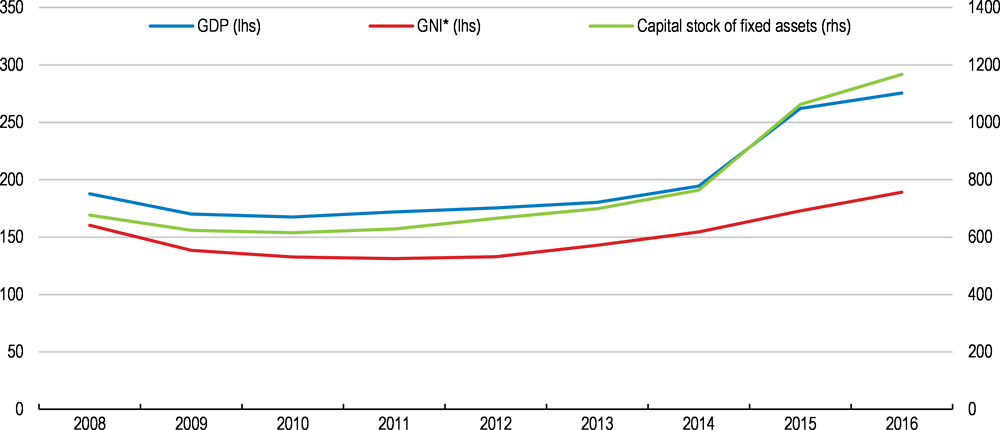

Box 1. Modified GNI – A new indicator of underlying economic activity in Ireland

Irish economic indicators recently made headlines due to an enormous upward revision for the year 2015. According to the Irish Central Statistics Office, real GDP grew by 25.6% in 2015 (compared to 8.3% recorded in 2014 and the initial estimate of 7.8% in 2015) while real GNP rose by 16.3%. The strength of these figures reflects issues associated with measures of economic activity produced in accordance with international standards in an increasingly globalised economy.

A small number of multinational enterprises (MNEs) relocated their intellectual property assets to Ireland in 2015. This resulted in a huge increase in the Irish capital stock. In 2015, the gross capital stock of fixed assets rose by some 300 billion Euros (compared with Irish GDP of 195 billion in 2014). The relocation of intellectual property assets was accompanied by a substantial increase in exports through contract manufacturing (for more details, see FitzGerald, 2015).

In this context, the headline GDP figure is becoming less relevant for explaining underlying economic activity in Ireland, which is problematic for policy-makers. An Economic Statistics Review Group was convened in 2016. It proposed a Modified Gross National Income (GNI) indicator that adjusts standard GNI for the depreciation of foreign-owned domestic capital assets and the retained earnings of re-domiciled firms (both of which are not considered relevant for explaining the resources available to the domestic population). The Central Statistics Office announced its first estimates in July 2017 with nominal GNI* growth of 11.9% in 2015, still very robust but significantly lower than the 34.7% nominal GDP growth reported for the year (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Growth in modified GNI has recently been weaker than GDP

Current prices, euro billions

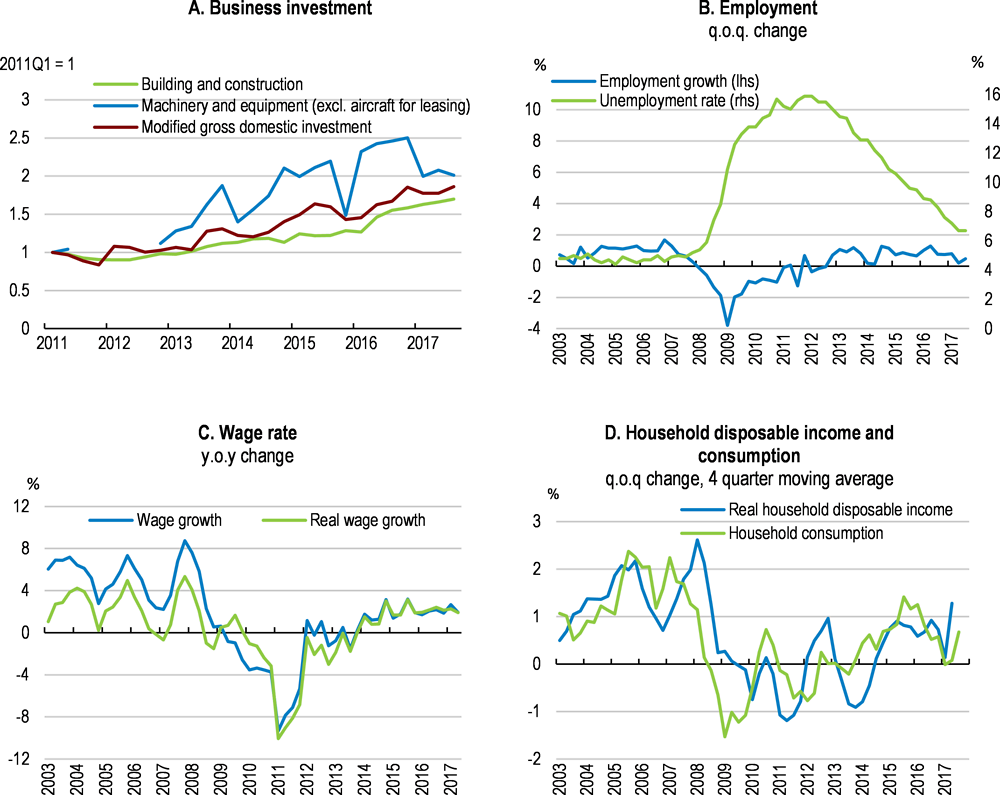

Business investment was significantly boosted by intellectual property (IP) investment by multinational enterprises in 2016, and intellectual property assets now account for around half of total business investment. Abstracting from such volatile items, investment among local Irish firms has been recovering, albeit from a very low base (Figure 4, Panel A). This has occurred despite SMEs facing lending interest rates that are among the highest across the euro area. Many local firms have instead opted to finance investment from retained earnings (Department of Finance, 2017a). Property prices have been rising rapidly due to excess demand that has partly owed to a natural rise in the population as well as a return to net inward migration. Construction investment has picked up in response, albeit off a low base (Figure 4, Panel A).

Figure 4. Domestic demand has been solid

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), Central Statistics Office.

Employment has risen in line with the recovery in economic conditions. This has led the unemployment rate to fall to around 6½% (Figure 4, Panel B). The tightness in the labour market in some sectors has contributed to a pick-up in wage growth over the past two years (Figure 4, Panel C), with household disposable incomes also buoyed by cuts in direct taxes (including cuts in the Universal Social Charge; Figure 4, Panel D). These factors have supported household consumption (Figure 4, Panel D). Nevertheless, inflationary pressures remain contained so far due to the appreciation of the euro against the sterling dampening import prices.

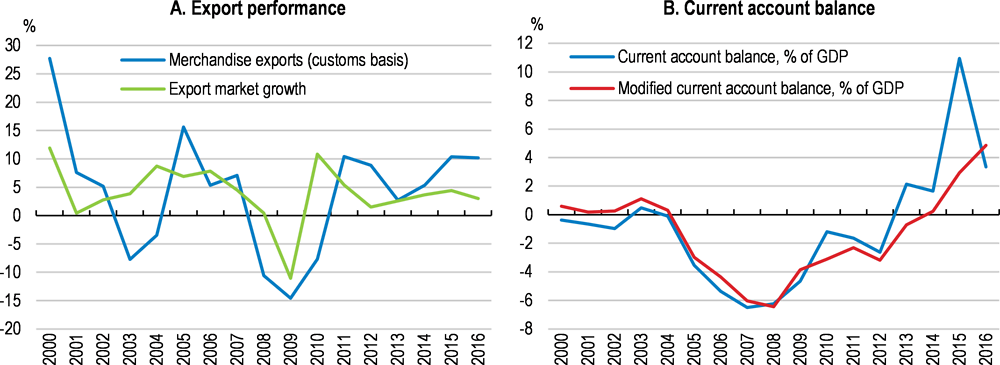

On the external side, exports have continued to rise, even excluding volatile items attributed to multinational enterprises (Box 1). Irish goods exports have tended to grow faster than external demand, with the emergence of pharmaceutical goods, computer and information services and financial services as key exports (Byrne and O’Brien, 2015). Consequently, Ireland’s export performance and current account balance have steadily improved (Figure 5). Trade with the UK has held up, despite the appreciation of the euro against sterling. Nevertheless, the impact of these exchange rate developments may only become evident with a lag.

Figure 5. Export performance has been strong and the current account balance has improved

Note: “merchandise exports (customs basis)” excludes contract manufacturing trade.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); Central Statistics Office of Ireland.

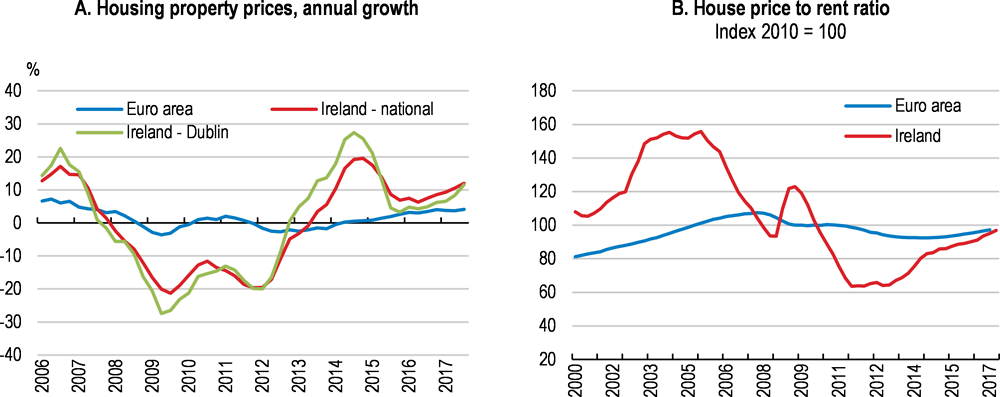

Looking ahead, the Irish economy is projected to expand at a more sustainable pace over the next two years (Table 1), with limited further productivity gains. Despite a less contractionary fiscal stance than in past years, activity in the domestic sector, notably business investment among Irish firms, will rise at a more moderate pace. Equipment investment will weaken, with the prospect of Brexit dampening confidence even if an agreement on a transition period is concluded. Employment growth will slow, but the labour market will increasingly tighten, feeding wage pressures and higher inflation. Weaker real disposable income growth will result in some easing in household consumption growth. On the back of high property prices (Figure 6, Panel A, B), construction investment will be solid, although dwelling supply is still expected to fall short of demand (Duffy et al., 2016). The exposure of the Irish economy to both significant internal and external shocks remains high (Table 3).

Table 1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices)

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (EUR billion) |

||||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

194.2 |

25.5 |

5.1 |

4.0 |

2.9 |

2.4 |

|

Gross value added excl. MNE dominated sectors (GVA*) |

134.1 |

7.3 |

5.1 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

|

Private consumption |

83.4 |

4.2 |

3.2 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

|

Government consumption |

31.4 |

2.1 |

5.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

40.3 |

27.9 |

59.7 |

-19.7 |

4.9 |

3.3 |

|

Housing |

4.2 |

4.9 |

13.7 |

11.5 |

6.2 |

7.4 |

|

Final domestic demand |

155.1 |

10.0 |

21.0 |

-6.9 |

3.2 |

2.4 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

5.1 |

-0.2 |

0.5 |

-5.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

160.2 |

8.8 |

20.2 |

-14.7 |

3.2 |

2.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

219.4 |

38.5 |

4.7 |

4.3 |

1.1 |

3.5 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

185.4 |

26.0 |

16.4 |

-5.0 |

0.5 |

4.0 |

|

Net exports1 |

34.0 |

18.6 |

-9.2 |

10.2 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.0 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

|

Output gap2 |

. . |

-0.4 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

|

Exports of goods |

|

11.3 |

8.7 |

. . |

. . |

. . |

|

Employment |

. . |

3.5 |

3.7 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

1.8 |

|

Unemployment rate |

. . |

9.9 |

8.4 |

6.7 |

5.8 |

5.6 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

7.3 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

|

Consumer price index (harmonised) |

. . |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

0.3 |

1.4 |

2.1 |

|

Core consumer prices (harmonised) |

. . |

1.6 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

2.1 |

|

Household saving ratio, gross3 |

. . |

6.8 |

6.7 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

5.9 |

|

Current account balance4 |

. . |

10.9 |

3.3 |

6.9 |

8.5 |

8.8 |

|

General government fiscal balance4 |

. . |

-1.9 |

-0.7 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance2 |

. . |

-1.1 |

-1.3 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

-0.9 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance2 |

. . |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht)4 |

. . |

77.1 |

72.9 |

71.9 |

69.2 |

67.0 |

|

General government net debt4 |

. . |

57.6 |

55.5 |

53.2 |

50.6 |

48.3 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

0.0 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

1.1 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

Underlying indicators of economic activity |

||||||

|

Modified Gross National Income (GNI*)5 |

154.5 |

11.9 |

9.4 |

|||

|

Modified Total Domestic Demand5 |

149.7 |

8.1 |

6.5 |

|||

|

Modified Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF*)5 |

31.7 |

25.2 |

13.0 |

|||

|

Modified Current Account Balance (CA*)4 |

. . |

2.9 |

4.9 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP. Based on OECD estimates of cyclical elasticities of taxes and expenditures. For more details, see OECD Economic Outlook Sources and Methods.

3. As a percentage of household disposable income.

4. As a percentage of GDP.

5. In current prices.

6. Modified GNI adjusts for the depreciation of foreign-owned domestic capital assets and the retained earnings of re-domiciled firms (see Box 1).

7. Modified GFCF and TDD: adjusts for investment related to leasing aircraft and R&D related intellectual property imports.

8. Modified CA adjusts for the depreciation of foreign-owned domestic capital assets and the retained earnings of re-domiciled firms in the same way as the modified Gross National Income (see Box 1) and for excluding imports related to leasing aircraft and R&D related intellectual property imports.

9. The substantial growth in exports and imports in 2015 is largely driven by “contract manufacturing” by multinational enterprises (see Box 1). The substantial growth in gross fixed capital formation and imports in 2015 and 2016 is largely related to the on-shoring of intellectual property which was imported to Ireland.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Figure 6. Property prices are rising strongly

Source: Eurostat, Central Statistics Office, OECD Analytical House Price Indicators database.

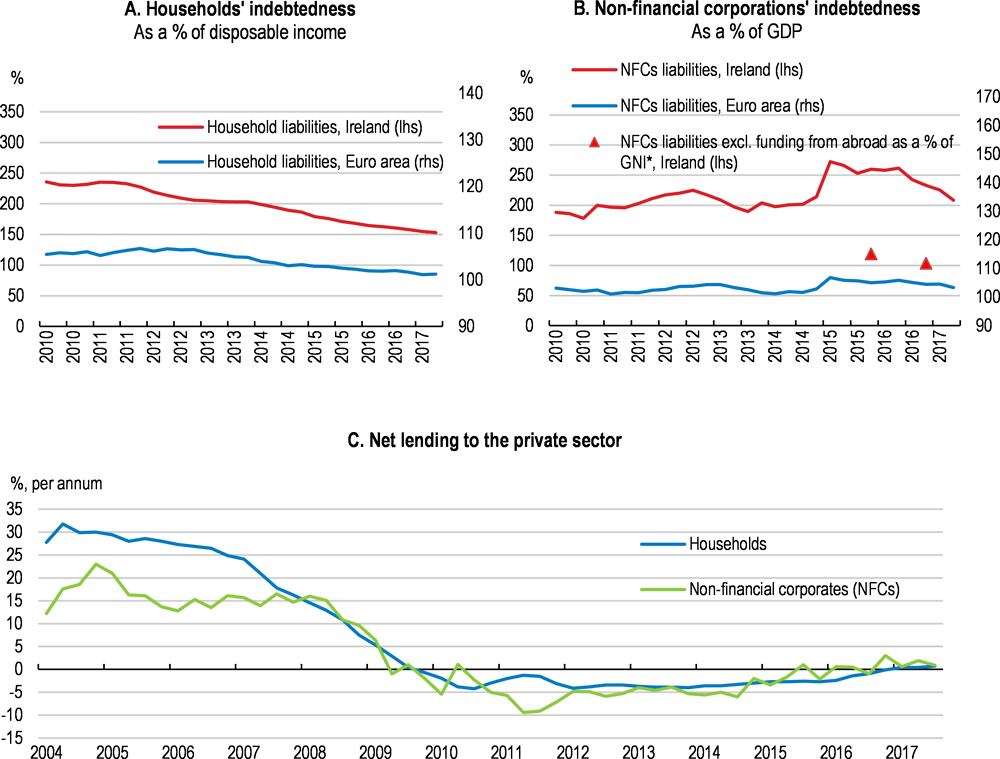

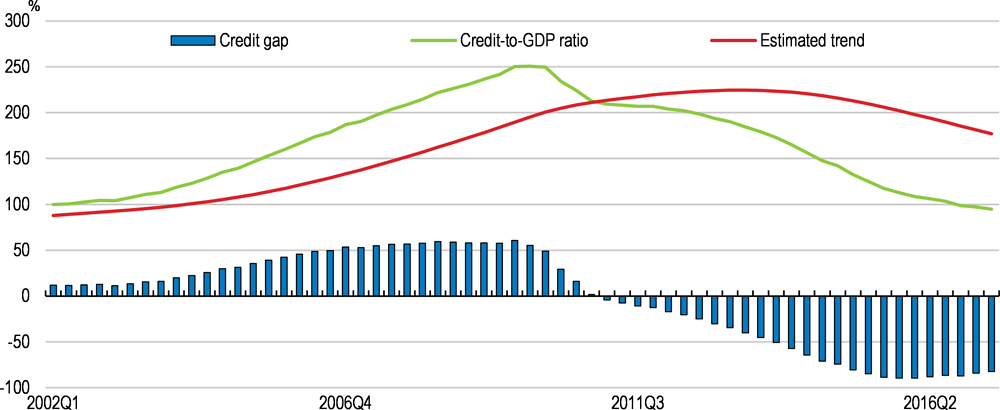

Risks to the outlook are elevated. On the upside, a stronger-than-expected recovery in Ireland’s trading partners may lead to a larger boost in exports and investment than is currently projected. Furthermore, property prices may increase more strongly, which would support construction activity in the near term. However, such a scenario may also sow the seeds of another property bubble, especially if it is associated with a strong pick up in credit growth from its currently low levels (Figure 7, Panel C). A disorderly trajectory for Brexit negotiations is a key downside risk which would heighten uncertainty and lower consumption and investment growth. Alternatively, increased clarity about the future trade relationship – especially if it begins to look more likely that an agreement with minimal tariff and non-tariff barriers will be reached – could have the opposite effect. In mid-December 2017, the first phase of negotiations between the EU and the UK resulted in an agreement to move to the second phase related to transition and the framework for the future relationship. Nonetheless, the eventual outcome of negotiations remains highly unpredictable.

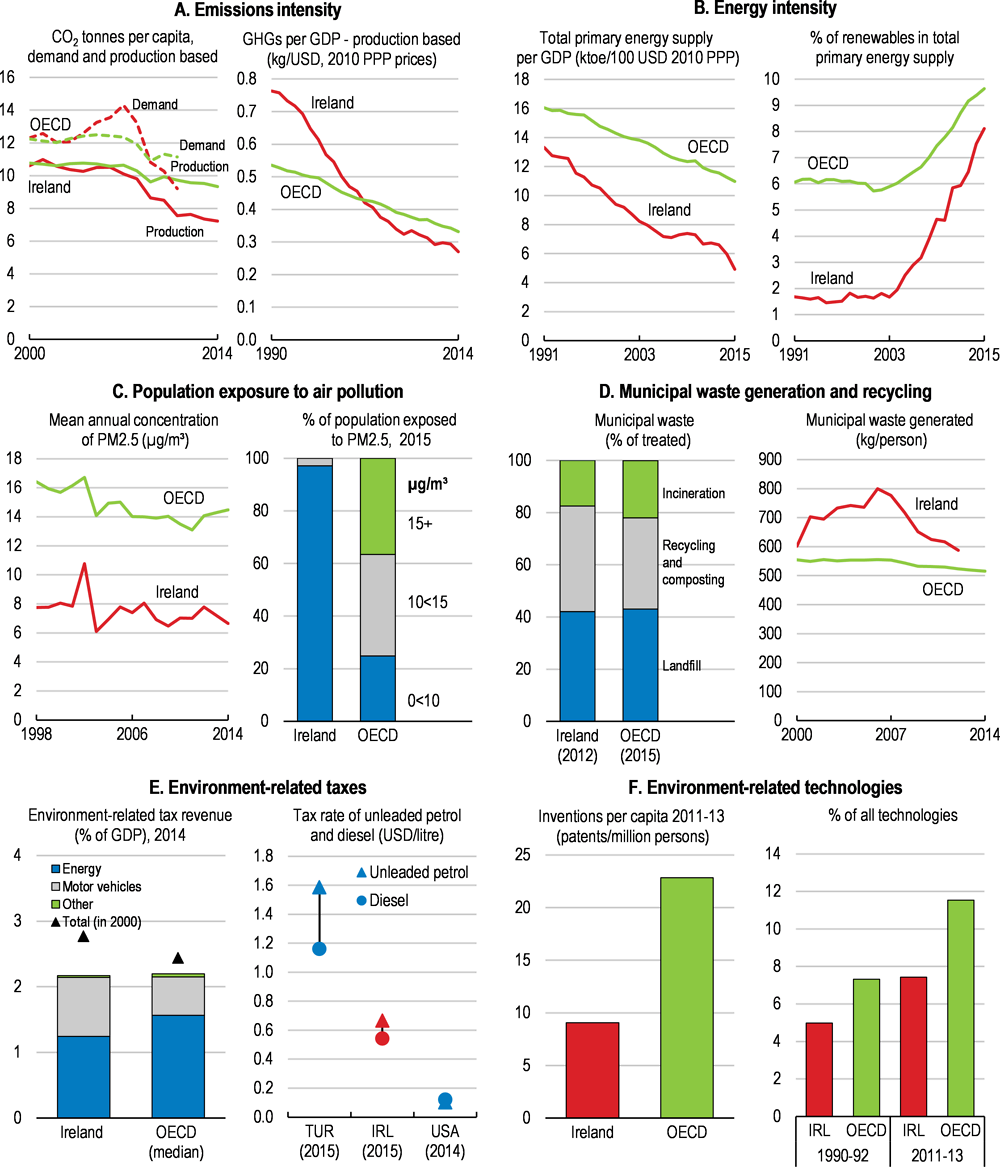

Figure 7. Private sector indebtedness remains high

Persistently high private indebtedness also poses a downside risk (Figure 7, Panel B), as it leaves the economy sensitive to rising interest rates. A more rapid tightening of the domestic labour market could raise labour costs by more than expected, undermining cost competitiveness and the exports of local Irish firms. While geopolitical tensions in oil producing countries could significantly raise energy prices, activity in Ireland would be impacted to a lesser degree than in most other countries due to lower energy intensity of production (Figure 18, Panel B further below).

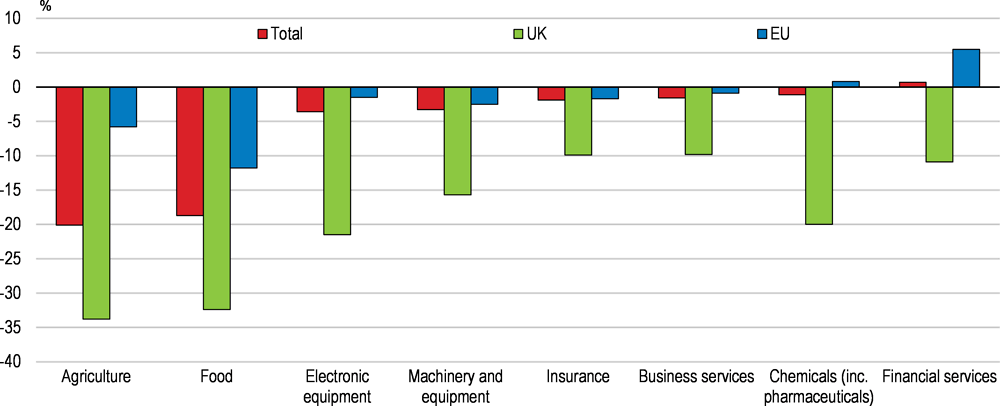

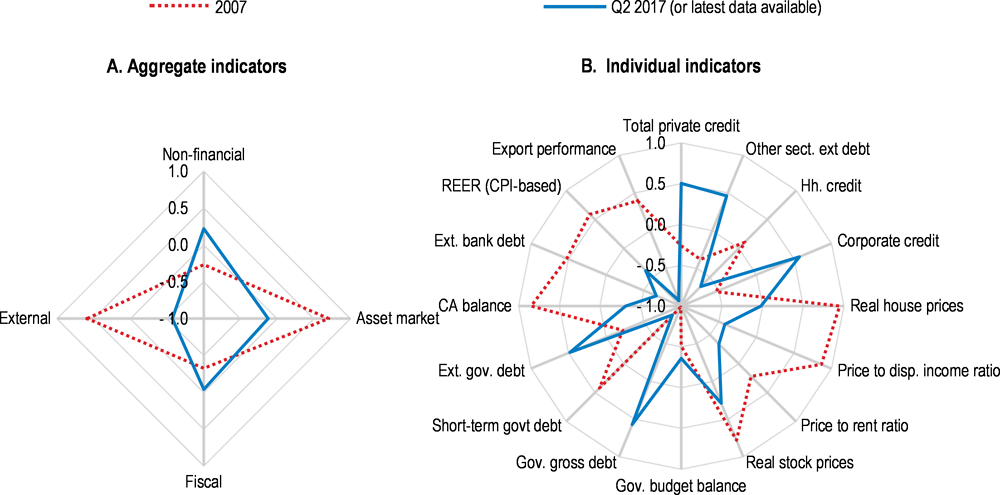

Overall, macro-financial vulnerabilities have decreased since 2007, but remain high in some areas due to the legacies of the crisis (Figure 8, Panel A). External debt has been significantly reduced, notably in the banking sector (Figure 8, Panel B). Property prices, though rising rapidly, remain somewhat below the long-term average (Figure 8, Panel B). In contrast, despite having declined in recent years, public and private sector debt remains above pre-crisis levels (Figure 8, Panel B), reducing the ability of the economy to withstand a future economic shock (Table 2). Such shocks could come in the form of a significant increase in policy barriers governing relations with the UK. Indeed, new modelling of a stylised Brexit scenario using the OECD METRO model highlights that a substantial increase in bilateral trade protection will have a relatively large negative impact on Irish exports. There will be substantial differences in the sectoral and regional impacts of such a shock (Box 2). For example, external demand for the agriculture and food sectors will be particularly hard hit. In contrast, the financial services sector may experience a slight increase in external demand.

Figure 8. Macro-financial vulnerabilities remain high in some areas

Index scale of -1 to 1 from lowest to greatest potential vulnerability, where 0 refers to long-term average, calculated for the period since 2000¹

Note: Each aggregate macro-financial vulnerability dimension is calculated by aggregating (simple average) four normalised individual indicators from the OECD Resilience Database. Individual indicators are normalised to range between -1 and 1, where -1 to 0 represents deviations with the observation being below long-term average [less vulnerability], 0 refers to long-term average and 0 to 1 refers to deviations where the observation is above long-term average [more vulnerability]. Non-financial dimension includes: total private credit (% of GNI*), other sector external debt (% of GNI*), household credit (% of GNI*), and corporate credit (% of GNI*). Asset market dimension includes: real house prices, price-to-income ratio, price-to-rent ratio and real stock prices. Fiscal dimension includes: government budget balance (% of GNI*) (inverted), government gross debt (% of GNI*), short-term government debt, and external government debt. External dimension includes: current account balance (inverted), external bank debt (% of GNI*), real effective exchange rate, and export performance.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2017), OECD Resilience Database.

Table 2. Possible shocks to the Irish economy

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcome |

|---|---|

|

Brexit |

A significant increase in policy barriers governing relations with the UK, and notably Northern Ireland, in the areas of trade, investment and labour markets would have large negative economic effects on Ireland. |

|

Increased international tax competition |

A significant reduction in corporate tax rates elsewhere (including the US) could reduce the attractiveness of Ireland as a destination for multinational enterprises. |

|

Rise in protectionism |

The Irish economy has benefited greatly from the globalisation process, so any significant reversal would have a detrimental impact. |

Box 2. Simulating the economic effects of an illustrative Brexit scenario

Past work has suggested that the consequences of the United Kingdom’s planned departure from the European Union (i.e. “Brexit”) will be felt more acutely in Ireland than in most other countries (Barrett et al., 2015). However, there are expected to be vastly different impacts across sectors of the Irish economy (Department of Finance, 2016). With this in mind, an illustrative Brexit scenario is simulated using the OECD METRO Model. This computable general equilibrium model consists of 13 regions (with the UK and Ireland disaggregated from the rest of the European Union), covers 27 sectors of the economy and specifies eight types of production factors (land, capital, natural resources and five different types of labour).

The modelled scenario is purely illustrative and does not represent a judgment about the most likely outcome of Brexit negotiations. Under the scenario, trade relations between the UK and all of its partners, both EU and non-EU, are assumed to be governed by the World Trade Organisation’s Most-Favoured Nation Rules. Consistent with past OECD work (Kierzenkowski et al., 2016), the scenario assumes that tariffs on goods exported from the UK increase to the importing country’s World Trade Organisation Most-Favoured Nation bound rates once the UK formally exits the EU. The UK contemporaneously imposes tariffs, equivalent to EU bound rates, on goods imports from the EU. The scenario is extended to consider non-tariff measures (NTMs) that could arise once Brexit occurs due to regulatory divergence and the associated increase in compliance costs (e.g. through border checks, health or technical compliance reviews, customs declaration).

The results highlight that the negative economic impacts of Brexit may be much larger for Ireland than for the average of all other EU countries (consistent with past work; i.e. Department of Finance, 2017b). However, there is a high degree of heterogeneity in the impact on exports across Irish sectors (for further details, see Arriola et al., 2017) and Figure 9 illustrates some of the most affected sectors. The most severe contraction in exports is for the Irish agriculture and food industries, which experience a fall in gross exports of around 20%. This mostly reflects a reduction in trade with the UK, but there is also a decline in exports to the other remaining EU countries. While not as large in value terms, there are falls in exports from other important sectors such as chemicals (which includes pharmaceuticals), business services, insurance and machinery and equipment. Notably, exports from the financial sector increase by 1% as a result of the Brexit scenario. UK financial services exports to the EU26 countries are simulated to decline notably, resulting in Irish financial services exports picking up to fill some of the void. The results suggest that financial services exports from Ireland to the EU26 would rise by around 6% following the shock.

Figure 9. There are disparities in sectoral impacts under the Brexit scenario

% change in gross Irish exports of selected sectors, by destination

Some of the sectors hardest hit in the illustrative scenario are concentrated in rural areas, highlighting regional disparities from the economic impact. For example, the majority of employment in the agriculture and food sectors is outside of Dublin. This is also true for the manufacturing sector, a large share of which is located in the Midlands and Border region. The fact that the latter has experienced the slowest post-crisis labour market recovery of any region suggests that the realisation of the illustrative Brexit scenario could be accompanied by rising poverty in this region and expanding aggregate income inequality. In response, the government should be prepared to deploy or reorient targeted social policies accordingly.

Incorporating the trade shock from METRO as well as assumptions relating to changes in exchange rates and sovereign risk premium into the National Institute Global Econometric Model (NiGEM) provides an indication of the potential GDP effects of the illustrative shock on Ireland. The results suggest that real GDP would fall by around 2½ per cent in the long run through the effect on trade and uncertainty. Nevertheless, it should be highlighted that the GDP effects are sensitive to the choice of model and assumptions about the increase in NTMs: while the macroeconomic channels are not as well specified in the METRO model, it estimates a larger decline in output for the observed trade shock – around a 4½ per cent fall in real GDP. Furthermore, using the Core Structural Model of the Irish economy (COSMO), previous work by Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute and Department of Finance find that the imposition of WTO MFN trade restrictions with different assumptions taken in relation to NTMs (than those assumed in METRO) would result in a 3.8% decline in real GDP (Bergin et al., 2017).

There may be countervailing impacts to the trade shock due to a relocation of foreign direct investment from the UK if such a shock were realised. Nevertheless, the economic impact of such relocation is estimated to be modest (Arriola et al., 2017), with the costs of the illustrative Brexit scenario likely to far outweigh any benefits for the Irish economy in net terms.

Solving the legacies of the crisis by buttressing the financial system and public finances

Continuing to stabilise the financial system

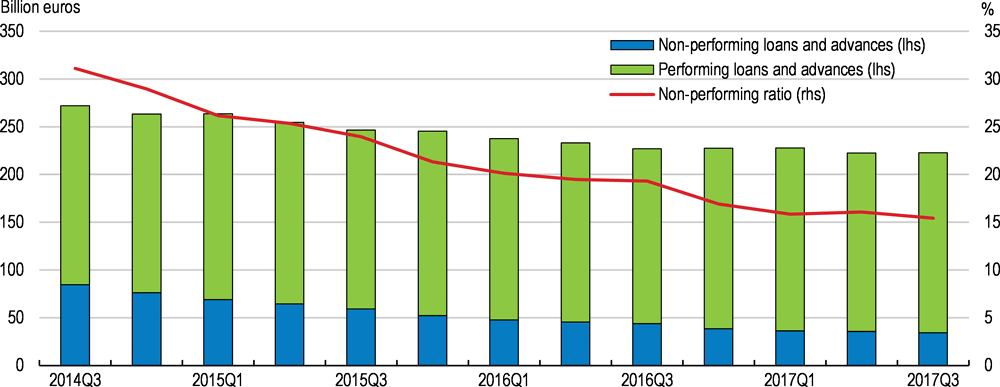

Ireland has emerged from a severe banking crisis with a deleveraged, recapitalised and restructured banking sector (OECD, 2015). The size of banks has shrunk and the quality of bank assets has improved (Figure 10), owing to the improvement in general macroeconomic conditions and specific actions undertaken by banks (i.e. restructures, sales, debt redemptions and write-offs). The aggregate bank capital adequacy ratio has improved: the fully-loaded (based on the Basel III rules that will apply at the end of the transition period in 2019) Tier I capital ratio stands at around 17% on average across Irish retail banks, around 9 percentage points higher than at the start of 2014. Looking forward, Brexit could present a headwind to future bank profitability. This could be the case, for instance, if it reduces borrowing by UK entities from Irish banks, has a negative economic impact on local Irish firms or is accompanied by a further depreciation in the pound sterling against the euro.

Figure 10. The size of banks has been reduced

Note: Data are consolidated and collected in accordance with the EBA’s FINREP reporting requirements.

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

Despite higher capital buffers, the banking system remains impaired due to a stubbornly high stock of non-performing loans (NPLs), leaving it vulnerable to possible shocks in the future. The NPL ratio, although having declined markedly, remains well above the EU average (Figure 11). Since the crisis, Ireland has made significant efforts to reduce NPLs. First, 11 500 property-related impaired loans worth 74 billion euro (43.5% of 2009 GDP) were transferred to the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA), a “bad bank”, and removed from banks’ balance sheets. These impaired loans were essentially large-scale commercial property loans and the contingent liabilities that this created for the state have now been fully eliminated. However, outside of these loans, the stock of NPLs remaining on banks’ balance sheets has also declined. The reduction in NPLs has been particularly rapid in the business sector, partly because the repossession of business assets is straightforward if collected by the receiver specified in the original loan contract, in which case a court order is not required.

Figure 11. The non-performing loan ratio remains high

Note: As described in the EBA’s risk indicator guide, the NPL ratio is calculated based on gross volumes from a sample of 189 European banks. See the EBA’s methodological guide (http://www.eba.europa.eu/risk-analysis-and-data/riskindicators-Guide).

Source: European Banking Authority (EBA), “Risk Assessment Report of the European Banking System, November 2017”.

In contrast, the NPL resolution has been slow in cases where the debtor’s primary dwelling is contested. These are usually mortgage loans or SME loans where the business owner has committed personal guarantees with their dwelling as collateral. In contrast with business assets, repossession of primary dwellings requires a court order, the issuance of which is inefficient.

Further resolution of NPLs is a challenge

There has been substantial progress in reforming the regulatory framework to address NPLs on bank balance sheets since the crisis. For example, the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) has issued specific guidelines in addition to those set out in the EU Capital Requirements Regulation and Capital Requirements Directive IV. These have included recommendations on disclosure, provisioning, loan restructures and collateral valuation. In March 2017, the European Central Bank also produced guidelines on NPL management practices and processes (ECB, 2016).

In contrast, there has been less progress in strengthening the regulatory framework relating directly to writing-off NPLs (ECB, 2016). The 2017 ECB guidelines have sections relating to NPL write-offs, but these are very general and not binding. The authorities may consider introducing stronger incentives for banks to reduce the stock of NPLs such as additional provisioning requirements for longstanding problem loans, as has been done in some other European countries. The introduction of such provisioning requirements should be accompanied by reforms improving the efficiency in collateral enforcement and strengthening the personal insolvency regime (see thematic chapter).

Improving the efficiency of repossession proceedings

NPLs have primarily been resolved through restructures rather than repossessions when the debtor’s primary dwelling is used as collateral. Debt restructures, even if successful, can impose a large debt servicing burden on the borrower over a long time. Almost 120 000 current primary dwelling accounts have been restructured at end-September 2017. As of mid-2017, around one third of these were in the form of arrears capitalisation, whereby some or all of the outstanding arrears are added to the remaining principal balance and then repaid over the life of the mortgage. In about 25% of cases, restructures have been in the form of a split mortgage, whereby a portion of the mortgage is warehoused at a lower interest rate for future payment. So far, the majority of restructured accounts are meeting the terms of the restructuring agreement.

The resolution of NPLs through restructures will become more difficult given the share of highly distressed borrowers is increasing. There are still 51 750 primary dwelling accounts in arrears (accounting for 7% of total outstanding primary dwelling accounts). Out of the accounts currently in a legal process (around 12 000), around 87% are over 720 days past due and 60% have already had some type of forbearance or modification, but remain non-performing (CBI, 2016a). A large proportion of the borrowers are highly indebted with limited income, meaning they are unlikely to be able to bear the cost of a restructured loan. In such cases, loss of ownership is likely to be inevitable, through repossession, mortgage to rent or voluntary surrender.

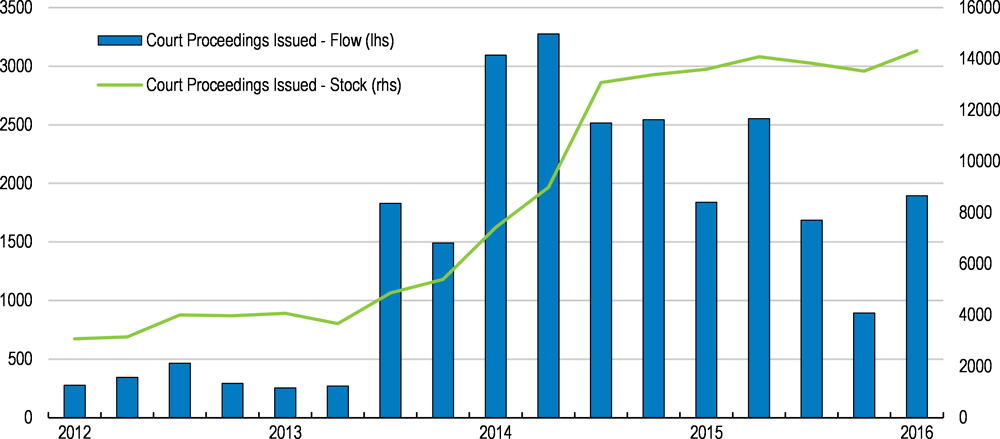

Improving judicial efficiency in repossession proceedings is a key factor for further addressing NPLs (ECB, 2016). As it stands, Ireland’s repossession process for residential properties takes a long time. From when the legal process for repossession commences, it has typically taken around 1½ years for a matter to be concluded (Expert Group on Repossessions, 2013). Despite a steady decline in applications for new court proceedings related to primary dwelling repossessions, the stock of accounts before the courts has remained stubbornly high (Figure 12). In 2016, less than 10% of primary dwelling accounts before the courts were repossessed with a court order.

Figure 12. The process of collateral repossession is slow

Note: Underlying data is confidential.

Source: CBI (2016a).

The elevated stock of accounts before the courts is due to the high frequency of adjournments. In some instances, the documents submitted to the court by the lender are not adequate and the grounds for forbearance pleaded by the borrower evolve over time, which both often result in further adjournments. This problem was addressed in a 2015 reform which introduced standardised documentation outlining the grounds on which repossession is being contested, accompanied by a statement of means. The authorities should evaluate whether this reform has had any success in improving case management of repossession proceedings (including through accelerating them), though the persistent high stock of court proceedings (Figure 12) suggests that any impact has been limited.

In order to speed up repossession proceedings, case management should be improved further. The authorities should consider standardising the ‘suspended’ possession order, like in the United Kingdom (CCPC, 2017). This would grant lenders a collateral possession order at a future date with the suspension of possession only conditional on well-defined criteria. By reaching a court mandated solution at an early stage, engagement between the borrower and lender would be better encouraged, standardising and speeding up repossession proceedings, while raising predictability for both parties. Trade-offs exist, as such a policy may have the unintended consequence of encouraging collateral to be run-down by debtors in some instances. The impact of any such policy change on debtor wellbeing should also be evaluated, with the reform carefully designed to ensure that the benefits with regard to reducing uncertainty and encouraging the provision of finance outweigh any unintended costs.

Protection of debtors

To protect heavily indebted households from slipping into poverty, adequate flanking policies are essential. The introduction of the “Abhaile” scheme in 2016, which provides vouchers to those with mortgage arrears so that they can access independent financial and legal advice, was important in this context. Adding to this, the provision of social housing through the realisation of the government’s Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness – Rebuilding Ireland will be critical. This plan aims to deliver 50 000 additional long-term social homes across the period 2016 to 2021 (Table 3). Importantly for social inclusiveness, the new units will be integrated in mixed tenure developments alongside private owners. Other reforms that promote housing supply in the right locations (discussed further below) will complement these aims. It may be the case that ensuring an adequate housing safety net has a positive impact on the processing of repossession orders, as the availability of decent alternative housing is an important factor considered by the courts when hearing these matters.

Macro-prudential policy tools should continue to be actively deployed

In response to volatile property price cycles, the CBI introduced new macro-prudential mortgage lending regulations in February 2015. While allowing some discretion by the lenders, the regulations limited the loan-to-value ratio to 90% for first-time buyers and to 80% for other home purchasers and restricted the allowable loan-to-income ratio to 3.5. Following the regulations, the incidence of lending with high loan-to-value ratios (i.e. above the regulated thresholds) has declined (CBI, 2016b) and there is evidence of new borrowers having a lower risk of default (Joyce and McCann, 2016). A counterfactual study also suggests that actual new lending and house prices would have been higher in the absence of the new regulations (Cussen et al., 2015). In future, the authorities could consider fine-tuning the prudential requirements at the local level. The prudential measures adopted over the past two years had greater effects in Dublin than outside the capital (Kinghan et al., 2017).

The central bank has committed to an annual review of the mortgage market measures. In November, the 2017 Review of Macro-prudential Mortgage Measures was published. It confirms that the measures continue to operate as intended but contains two changes: namely, a reduction in allowances on lending above the 3.5 times loan-to-income limit and an adjustment to the calculation of the value of collateral for purchase-to-renovate properties (which is more conservative than the previous calculation). These changes have been introduced to make the regulations more effective in mitigating the risk of unsustainable mortgage lending in the future and took effect on 1 January 2018.

The central bank, as the designated authority for macro-prudential policy, has also introduced the counter-cyclical buffer framework to mitigate and prevent excessive credit growth and system leverage. The counter-cyclical buffer rate has been left unchanged at 0%. This is appropriate for now, given that early warning indicators relating to financial sector stress are benign (Figure 8; Figure 13). However, the rate should be raised appropriately when needed. In such a case, the authorities should verify if risk-weights to mortgage lending estimated by banks are appropriate for the measure to contain excessive credit growth (Jin et al., 2014).

Figure 13. Tighter macro-prudential policy is not warranted at this stage

Credit-to-GDP ratio and gap – National specific approach

Note: While applying the standardised methodology, the Irish national specific approach uses an alternative measure of credit and economic activity: it uses GNI* (see Box 1) instead of GDP and NFC credit from Irish resident credit institutions rather than the aggregate NFC credit. The estimated trend line is calculated using a Hodrick-Prescott filter. The credit gap is defined as the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from the long-run trend.

Source: Central Statistics Office, BIS and CBI calculations.

Table 3. Past recommendations related to improving financial stability

|

Recommendation |

Action taken since the July 2015 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Accelerate through the court system the resolution of non-performing loans that require repossessions |

Changes to court rules were introduced on 17 August 2015 to streamline the management of repossession cases by requiring key proofs to be lodged in writing. Following the changes, a Civil Bill for Possession must be accompanied by a sworn affidavit which provides information on the property concerned, occupation of the property, the security held by the lender, details of the loan agreement, the arrears owed and evidence that the lender has abided by the relevant central bank regulations. |

|

Continue to improve the responsiveness of housing supply including in the rental market and avoid home buyer subsidies. |

Rebuilding Ireland – Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness (July 2016) includes over 110 actions with an overarching objective to double the annual level of residential construction to 25 000 homes and deliver 47 000 units of social housing in the period to 2021. |

Maintaining fiscal sustainability

Ireland’s fiscal position has improved over the past decade: abstracting from one-off influences, the fiscal deficit declined from 11½ per cent of GDP in 2009 to around 1% by 2016 (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2017), with the adjustment being mostly structural.

Public finances have recently benefitted from a sharp increase in corporate tax receipts. In 2016, the corporate tax yield was close to 80% higher than the average collected over the four years to 2014. Corporate taxes have been by far the most volatile of Ireland’s tax heads over the past two decades (Casey and Hannon, 2016), but the recent increase was especially large. It appears to have been partly attributable to the economic recovery, given that most sectors exhibited rising tax payments. However, the financial and ICT sectors accounted for the bulk of the increase. There was also a rise in the concentration of tax receipts across firms, with the share of the top ten taxpayers in total corporate tax revenues rising to just below 40% (Department of Finance, 2018b).

As cautioned in the recent Review of Ireland’s Corporation Tax Code, though the increase in corporate tax receipts may be sustainable in the medium term, the inherent volatility in this revenue stream will remain (Coffey, 2017). The rise in the share of corporate tax in total tax revenue over recent years (Table 4) suggests that the exchequer’s total tax take will be more subject to volatility going forward. As a consequence, unbudgeted corporate tax receipts should be used to build fiscal buffers. This is especially important at present given the large share of multinational firms in the tax base in an environment of increased international tax competition. Indeed, around 80% of Ireland’s total corporate tax receipts are derived from multinational enterprises (Department of Finance, 2018b).

Table 4. Share of total tax revenues by tax head, %

|

|

2011 |

2017 |

|---|---|---|

|

Income Tax |

40.5 |

39.4 |

|

Value Added Tax |

28.6 |

26.2 |

|

Corporation Tax |

10.3 |

16.2 |

|

Excise Duties |

13.7 |

11.7 |

|

Other |

6.7 |

6.5 |

Source: Department of Finance.

In building fiscal buffers, the government has announced the establishment of a “Rainy Day Fund” to be financed through annual transfers from the government. It is intended that this will be used to help absorb future economic shocks at the same time as ensuring the long-term sustainability of public finances. The annual contributions to the fund have been agreed at 500 million euro per year over the 2019-21 period. Establishing such a fund rather than using contributions to pay down public debt is attractive insofar as it provides access to a liquid pool of cash in the event of a significant disruption to external funding markets.

Ireland has played an active role in implementing international tax reforms through the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, with the implementation of the remaining BEPS reforms currently subject to an ongoing consultation process. It is essential that the government remains proactive in the ongoing international efforts to co-ordinate tax standards and address BEPS. This process requires that all countries ensure that tax measures do not encourage commercial arrangements that are purely tax-driven and not accompanied by substantive economic activities.

The exact impact of recent corporate tax changes in the United States on the Irish economy and public finances is unclear: while the US move towards a territorial tax regime could incentivise US corporations that repatriate profits to invest in Europe, there are also new measures designed to encourage companies to relocate their intellectual property from foreign jurisdictions to the US. In addition, the details of any future international agreement relating to the taxation of the digital economy remain highly uncertain, making it difficult to speculate about their potential impacts on the Irish economy.

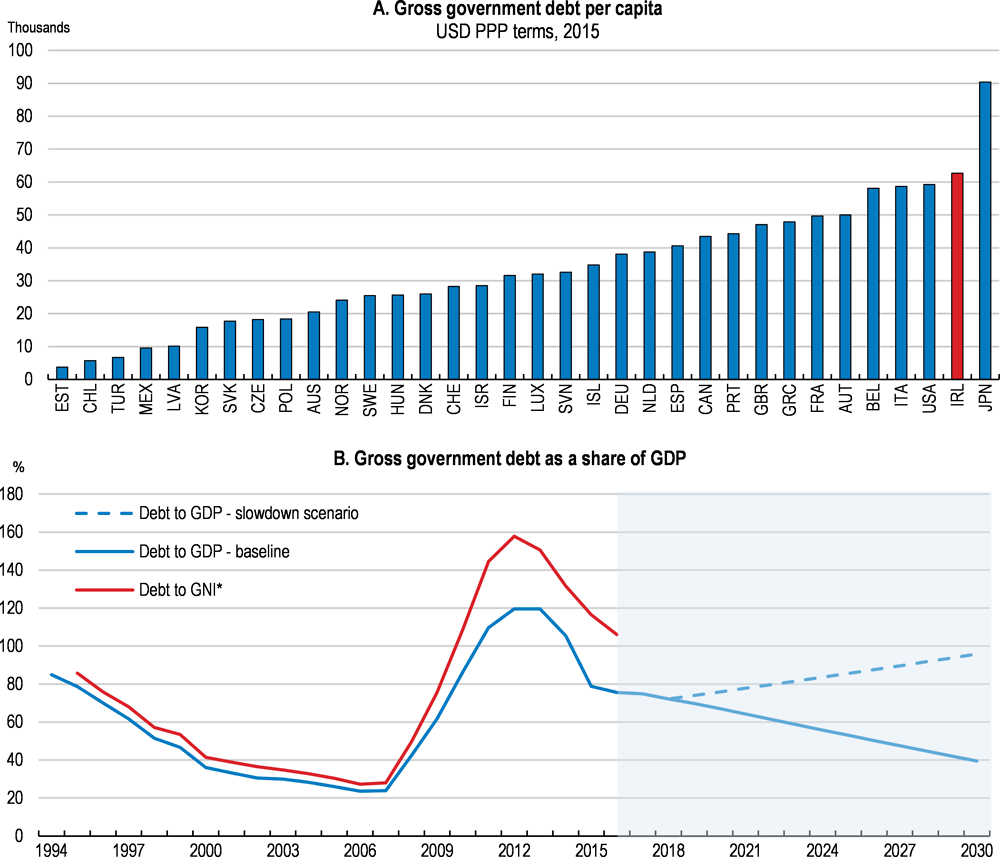

As a result of the reductions in the fiscal deficit, public debt ratios have begun to trend down. Nevertheless, gross public debt still remains above 100% of GNI* (and around 75% of GDP in 2016) and, in per capita terms, is one of the highest across the OECD countries (Figure 14, Panel A). That said, the maturity profile of public debt is relatively elongated by European standards, limiting rollover risk. The government is aiming to improve the fiscal position further, reducing gross public debt to 55% of GDP as an interim target and 45% once major capital projects have been completed. Achieving this target is prudent given Ireland’s high exposure to external shocks and the fact that automatic stabilisers should be allowed to operate if such a shock does eventuate. Nevertheless, targeting debt as a share of GDP is less meaningful in Ireland than in other European countries given the distortions in estimates of nominal GDP that exist (Box 1). As GNI* is less affected by one-off factors that do not reflect sustainable increases in national income, it is a better indicator of the capacity of the government to repay its debt. Consequently, the government should also set medium-term debt targets as a share of GNI*. With the publication of the 2018 Budget, the government highlighted a willingness to use public finance ratios as a share of GNI* for analytical purposes, which is welcome.

Figure 14. Public debt ratios have improved but remain high

Note: In Panel B, the “Baseline” scenario takes the most recent OECD forecasts for the primary balance, real GDP and inflation from 2017-2019. Thereafter, real GDP growth is held constant at 2.2% per year and inflation at 1.8%. Department of Finance projections for the primary balance are used from 2020-2021 and then the balance is held constant at 2.3% of GDP. The “Slowdown scenario” takes the baseline to 2019 but then assumes a slowdown in real GDP growth and inflation to 1% per year and a primary deficit of 1% of GDP each year from 2020-2030.

Source: Department of Finance, OECD Economic Outlook, OECD Government at a Glance, OECD calculations.

Box 3. Simulations of the potential impact of structural reforms

Simulations based on historical relationships between reforms and economic indicators in OECD countries allow the potential impact of some of the structural reforms proposed in this Economic Survey to be gauged (several of these come from the thematic chapter that follows). These estimates assume swift and full implementation of reforms in three main dimensions: product market regulations, investment policies and labour market policies. In some cases, there may be countervailing policy recommendations (i.e. a land tax that replaces the local business tax) that are not quantified. Furthermore, the simulation results are based on cross-country estimates that do not reflect the unique institutional settings in Ireland which will influence their efficacy. As such, these estimates should be seen as purely illustrative. The policy changes that are assumed (detailed in the note to Table 5) are based on the specific policy recommendation, recent reforms in other countries and Ireland’s current policy settings in the particular dimension.

Table 5. Potential impact of structural reforms on GDP per capita after 10 years

|

|

∆GDP per |

Impact on supply side |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Structural policy reform |

capita |

components |

||

|

|

MFP |

K/Y |

L/N |

|

|

|

in percent |

in percent |

in pp |

|

|

Product market regulation |

||||

|

(1) Raise competition in the legal service sector |

0.99 |

0.72 |

0.15 |

0.14 |

|

(2) Streamline the permits and licence system |

0.33 |

0.24 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

|

Investment specific policies |

||||

|

(3) Rationalise the local business tax |

0.29 |

0.61 |

||

|

(4) Support business R&D further |

0.34 |

0.34 |

||

|

Labour market policies |

||||

|

(5) Enhance training programmes for workers |

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.04 |

|

|

(6) Withdraw benefits more gradually as earnings rise |

0.42 |

0.28 |

||

|

(7) Increase support for childcare services |

0.23 |

0.15 |

||

|

Total |

2.7 |

|||

Note: The policy changes that are assumed for each measure are as follows: (1) the OECD measure of regulation in professional services is lowered from 3.5 to 3.2 (which would be the value of the indicator if the recommended reforms were undertaken); (2) the OECD Product Market Regulation indicator relating to barriers to entrepreneurship is reduced from 2 to 1.9 (which would be the value of the indicator if the recommended reforms were undertaken); (3) Business tax revenues as a share of GDP are reduced from 0.8% to 0 (consistent with the recommendation in the thematic chapter to introduce a broad-based land tax to replace commercial rates); (4) Business R&D spending as a share of GDP is increased from 1.1% to 1.3% (the OECD average level), (5) Active Labour Market Programme spending per unemployed worker as a share of GDP per capita is increased from 14% to 14.5% (the OECD average level); (6) Family Income Supplement, an in-work benefit for the low-paid, is reduced at the withdrawal rate of around 30%, instead of 60% as is currently the case, consistent with the reforms recommended in OECD (2015), which would have an impact equivalent to a reduction in the representative replacement rate from 76.8% to 75.4%; and (7) Childcare spending as a share of GDP is raised from 0.9% to 1% (the size of reform typically observed in OECD countries).

Source: OECD calculations based on Egert and Gal (2017).

Expectations of further fiscal improvements are predicated on continued stable medium term economic growth. However, as discussed, vulnerabilities to the outlook are high. An outcome for Brexit negotiations that results in substantially higher bilateral tariff and non-tariff barriers between Ireland and the UK could have a serious negative impact on the Irish economy (Box 2). A scenario in which economic activity slows by more than expected would result in the public debt ratio rising markedly over the medium term (Figure 14, Panel B). In this context, the government should prepare a contingency plan that identifies productivity-enhancing fiscal initiatives that are temporary in nature and could have a large short-term impact on growth in the face of a negative shock. At the same time, many of the growth-enhancing structural reforms recommended in the thematic chapter of this Economic Survey (Box 3) along with adjustments to specific aspects of fiscal policy would put the economy, and public finances, on a firmer footing (Box 4).

Broadening the tax base in a growth-friendly manner

Some aspects of Ireland’s tax system both distort the efficient allocation of resources and narrow the tax base. Reforming such measures would raise fiscal space, leaving the government in a better position to tackle short-term external shocks or undertake the spending needed to tackle the medium-term challenges that lie ahead.

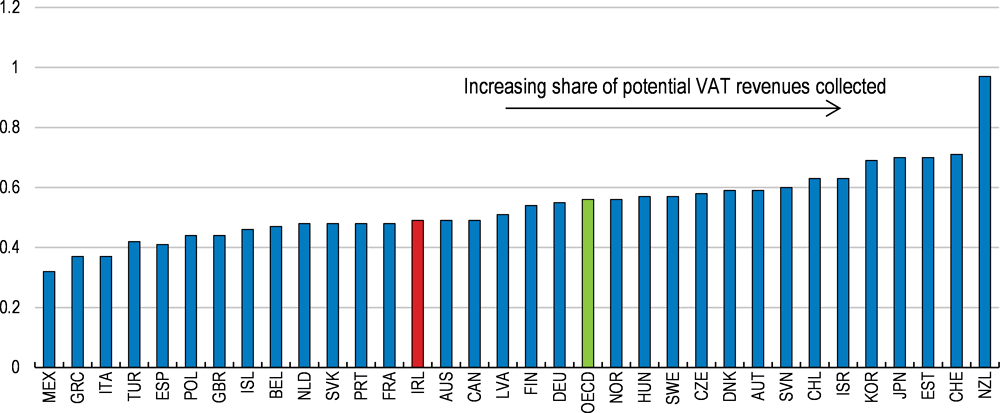

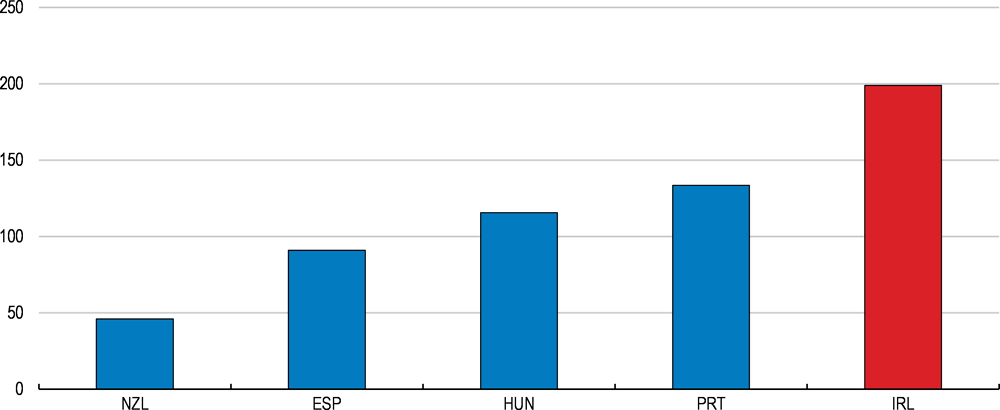

Value added taxes (VAT) contribute a slightly higher share of revenue in Ireland than in most other OECD countries. The level of VAT compliance is also relatively high (European Commission, 2017a). This is beneficial given consumption taxes are less harmful for growth than income and corporate taxes (Johansson et al., 2008). Nevertheless, Ireland’s VAT system has five different rates that can be applied depending on the item. Indeed, more revenue is lost from differential VAT rate treatment than in most other EU countries (European Commission, 2017a), with the majority of potential VAT revenues remaining uncollected (Figure 15; OECD, 2016b).

Figure 15. The majority of potential VAT revenues remain uncollected

VAT Revenue Ratio

Note: The VAT Revenue Ratio is the ratio between the actual value-added tax revenue collected and the revenue that would theoretically be raised if VAT was applied at the standard rate to all final consumption.

Source: OECD, 2016b.

While reduced VAT rates on some household products may be an attempt to make the tax more progressive, lower rates for items such as purchases at restaurants, hotels and cinemas likely work in the opposite direction. Furthermore, preferential VAT rates are very ineffective at targeting support to poor households compared with means tested benefits (OECD/Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2014). With this in mind, exemptions should be gradually eliminated to converge towards a comparatively uniform VAT rate, such as that implemented in New Zealand. A first step could be to streamline the VAT rate structure, moving from five different VAT rates to three. This could be done in a way that raises significant government revenue (Department of Finance, 2017c; Table 6). Nevertheless, such a reform may need to be accompanied by welfare spending that ensures vulnerable households are not negatively impacted.

The revenue base is also narrowed by other preferential tax rates which have little economic, social or environmental rationale. For instance, a lower rate of excise is paid on diesel fuel for road use compared with petrol. This excise gap has broadened since the financial crisis, contributing to a notable increase in the number of kilometres driven in diesel cars (Department of Finance, 2017d). Given air pollutant emissions are higher for diesel than petrol vehicles (European Commission, 2017b), this preferential treatment also has negative environmental and health consequences. While raising the excise rate on diesel to that levied on petrol is justified on environmental grounds, it would also raise an additional EUR 300 million per year for the exchequer (Department of Finance, 2017d).

There is also scope to increase revenues from property taxation by more regularly updating market values. Such taxes are one of the least distortive in terms of reducing long-run GDP per capita (Johansson et al., 2008). Ireland introduced a local property tax in 2013, but the share of property tax in total taxation remains around half that of countries such as the UK and Canada. The local property tax is levied on a self-assessment of the market value of a property. However, for most properties, taxes are currently being paid on the 2013 value, with a planned valuation update having been postponed from 2016 to 2019. This has meant households in locations where house prices have grown particularly fast face a sharp cliff in their property tax bill in 2019. A potential one-off measure to cushion the impact on the finances of such households is a gradual adjustment (i.e. over multiple years) of the tax base to the 2019 market value. This situation should be avoided in future by introducing a more regular reassessment of property values for the purposes of levying the tax. Such an adjustment to the system should be explored as part of the government review of the local property tax that will be undertaken during 2018. In this process, the authorities should also consider potential adverse impacts of a revaluation on lower-income households and whether current policy settings would be sufficient to protect them from slipping into poverty. Exemptions from the local property tax currently exist only for some forms of social housing and individuals affected by illness, although property tax liabilities can be deferred by low-income individuals under certain circumstances.

The authorities should also continue to phase out mortgage interest tax relief, the presence of which has likely done little to improve housing affordability given constraints to housing supply (discussed further below). The government intends to taper out the relief by 2020. This timeline should be adhered to with no further extensions granted. The elimination of mortgage interest tax relief should contribute just under EUR 200 million per year to government revenue (Box 4).

Box 4. Quantifying fiscal recommendations

The following estimates roughly quantify the fiscal impact of selected recommendations. It should be noted that some recommendations (such as more regular updates of property values for the purpose of calculating the local property tax) are not quantifiable given the available information and the complexity of the tax design. The estimated fiscal effects abstract from short-term behavioural responses that could be induced from the given policy change (in line with past OECD work modelling long-term scenarios; Johansson, et al. 2013).

Table 6. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

|

Policy |

Measure |

Annual fiscal balance effect, % of GDP |

|---|---|---|

|

Additional expenditures |

||

|

Additional health spending |

Universal access to publicly funded health and social services along with additional health investment (as outlined in Committee on the Future of Healthcare, 2017) |

-0.4 |

|

Enhancing training programmes |

Active labour market programme spending per unemployed worker as a share of GDP per capita is increased from 14% to 14.5%. |

-0.0 |

|

Withdraw benefits more gradually as earnings rise |

Family Income Supplement, an in-work benefit for the low-paid, is reduced at a withdrawal rate of around 30%, instead of 60% (as is currently the case). |

-0.4 |

|

Increase support for childcare services |

Raise childcare spending as a share of GDP from 0.9% to 1% |

-0.1 |

|

Offsetting measures |

||

|

Budget balance effect associated with higher GDP induced by structural reforms highlighted in Box 3 |

||

|

Increased budget balance induced by stronger GDP |

The structural reforms highlighted in Box 3 are highlighted to raise GDP by 2.7% and employment ratios by 0.66 percentage points, respectively. The change in employment ratios would translate into a 0.3 percentage point improvement in the budget balance in the long-run (a 1% change in employment ratios is estimated to improve the primary balance by around 0.5 points for Ireland, OECD, 2010). Productivity improvements are assumed to be fiscally neutral in the long run according to the past OECD work modelling long-term scenarios (Johansson, et al., 2013). |

0.3 |

|

Additional revenues |

||

|

Reduce the extent of VAT rate differentiation |

Streamline VAT rates to be either 5%, 15% or 25% (using fiscal estimates from Department of Finance, 2017c) |

0.8 |

|

Raise excise on diesel fuel |

The excise on diesel fuel for road use is increased to be in line with that of petrol (using the fiscal estimates from Department of Finance, 2017d). |

0.1 |

|

Phase out mortgage interest tax relief |

Completely eliminate mortgage interest tax relief (using the fiscal estimates from Department of Finance, 2017e) |

0.1 |

|

Introduce tax on vacant properties |

Assumes a tax on vacant dwellings of 2% in the cities of Dublin, Cork, Galway, Limerick and Waterford (obtained from the 2016 Census and excludes holiday homes), assuming that such properties are valued at 20% below the market average in each area. |

0.1 |

Addressing medium-term challenges for wellbeing

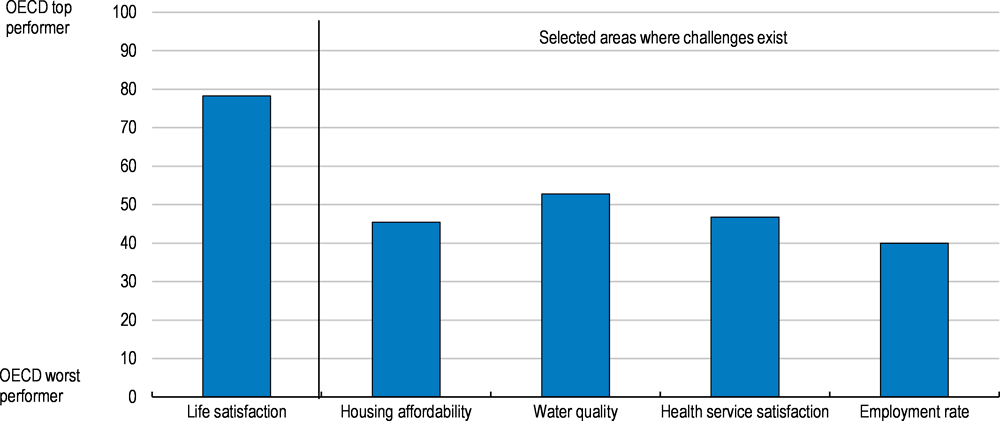

The Irish population enjoys a high level of wellbeing, reporting levels of life satisfaction that are close to the top of the OECD (Figure 16). Compared to individuals in other economies hard hit by the financial crisis, those in Ireland feel that they are much better off. Looking forward, further raising living standards in Ireland will depend on the ability to reignite productivity growth in local firms and this is extensively discussed in the thematic chapter of this Economic Survey. At the same time, there are several dimensions of wellbeing that are influenced by government policy and where there is significant scope for improvement. At present, challenges exist in the areas of housing affordability, the environment, the health system and in getting people into work. In many cases, more vulnerable households are the ones that are adversely affected by deficiencies in these areas. As such, well-designed reforms that prioritise these areas can be highly beneficial for inclusiveness. While there is still scope for spending efficiency gains in particular policy areas such as public infrastructure and health, government spending will also need to be boosted in some instances. In this context, there is a need to recognise the trade-offs in fiscal spending that exist and raising revenues through the tax reforms just discussed.

Figure 16. Wellbeing is high, but some aspects can be improved

Selected wellbeing indicators, 100 = top OECD country and 0 = bottom OECD country

Note: The figure represents the relative position of Ireland with respect to OECD's best and worst performer in each of the areas. For example, if the index is below 50, Ireland scores closer to the worst performing OECD country than the best performing OECD country on that dimension.

Source: OECD Better Life Index, OECD Government at a Glance.

Promoting increased housing supply

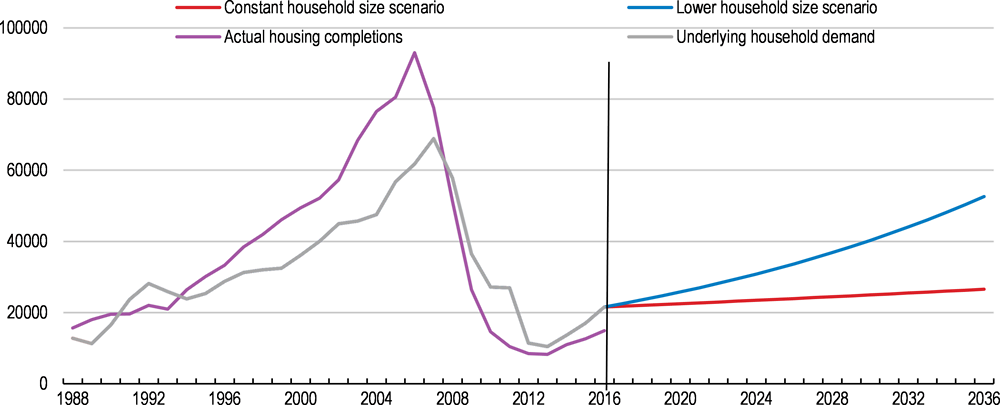

Housing supply contracted sharply from late 2007: the supply of new dwellings fell by over 90% between 2006 and 2013. The contraction in housing supply was sharper than that of underlying demand through these years (see Appendix 1), due to excess supply in the years beforehand and a reduction in the availability of finance for property developers once the crisis took hold.

The recovery in housing supply has been tepid in recent years. Underlying housing demand has outpaced actual supply (Figure 17), manifesting itself in stronger growth in house prices and rents (as already discussed). Such increases have been rapid in Dublin compared with the rest of the country. This has elevated housing affordability concerns and contributed to the number of homeless people in Ireland doubling between the start of 2015 and mid-2017. At the same time, rising housing costs for professionals may have dissuaded further foreign direct investment and return migration of Irish nationals living abroad (European Commission, 2017b).

Figure 17. The current level of housing supply is insufficient to meet future demand

Estimated underlying housing demand and actual completions, number of dwellings

Note: See Appendix 1 for a detailed discussion of these estimates. Previous work has highlighted that much of the increase in housing completions prior to the crisis were in areas with limited housing demand (Kitchin et al., 2012), meaning that the apparent oversupply of housing in those years has little relevance for the current balance in the housing market.

Source: Central Statistics Office, OECD estimates.

Projecting underlying housing demand highlights the need for an increase in dwellings over the coming decades. Estimates are sensitive to the assumption regarding average household size (see Appendix for details). However, even if it is assumed that household sizes halt their trend decline (some evidence of this was observed in the 2016 Census), new housing demand will exceed current annual housing supply in the future (Figure 17). If average household sizes continue to decline along the trend observed between 1996 and 2016, over 50 000 new dwellings per year will be needed by 2036. In 2017, only around 19 000 new dwellings were added.

The government has enacted reforms in recent years to improve housing affordability. Housing Assistance Payment limits have been increased and the government has also introduced a “help-to-buy” scheme. The latter measure provides first-time buyers a refund of income tax and deposit interest retention tax paid (over the previous four years) of as much as 5% of the dwelling purchase price. There have also been measures put in place to cap the growth in housing rents. For instance, landlords can now only review rents once every two years (previously annually) and limits have been placed on the magnitude of rent increases (4% per annum) for existing rental properties in parts of the country where rents are highest and rising. While all of these measures may improve affordability in the short-term, they will do little for affordability over a longer horizon if they feed into rising dwelling prices or dissuade investment in rental housing.

For a longer-term solution, policymakers must focus on measures that encourage greater housing supply. Some initiatives already implemented include the Local Infrastructure Housing Activation Fund, designed to provide the local public infrastructure needed to facilitate housing development (such as access roads), and the introduction of fast-track planning measures for large-scale housing developments. In the 2018 Budget, a tax deduction of up to EUR 5 000 for pre-letting expenses for previously vacant properties that were brought onto the rental market was announced. As it is unclear how much extra supply of rental housing this measure will induce, the government should also consider introducing a higher recurrent property tax rate on properties that are left vacant in city areas.

Housing construction costs are significantly higher in Ireland than in other European countries (Lyons, 2017), with stringent regulations on home building likely to be one contributing factor. National Building Control Amendment Regulations, introduced in March 2014, required self-certification of the safety and quality of dwellings by a registered architect. This contrasted with the regulatory approach undertaken in other countries, such as the UK and US, where local authorities are responsible for inspections and building certification. Evidence that the self-certification requirements inflated the cost of housing developments led to a ministerial review and the eventual relaxation of the regulations for one-off houses and extensions (Reynolds, 2015). The government should also eliminate the self-certification process for multi-dwelling projects. However, this will need to be accompanied by some public investment in local authorities to enable them to undertake more inspections and consistently enforce regulations.

There have also been new regulations by local councils which may have stifled the scale of new home building. For example, Dublin City Council introduced more stringent dwelling standards in 2008. At present, the allowed minimum dwelling size in Dublin is one of the highest in Europe (currently at 45m² for a one bedroom apartment) and there is a ban on north-facing apartments. The height of new developments is also limited to seven floors in most districts. These regulations increase housing costs and serve to reduce the population density in the capital city (which is already a low density city compared to other European capitals such as London, Berlin and Paris). Furthermore, they hamper inclusiveness by reducing the stock of inexpensive housing available on the private market. The national government has recently issued updated draft planning guidance for apartment design that takes some steps in encouraging greater housing density. For example, the allowable number of units per floor has been increased and requirements relating to the number of car spaces per development have been relaxed in areas with good access to public transport.

In promoting housing development in Ireland’s urban centres, efforts should be intensified to identify underutilised land in prime locations. In Dublin, there are multi-acre sites in valuable locations that house army barracks, bus depots and industrial estates that are vacant or no longer used at full capacity (Lyons, 2016). Some of these sites could be rezoned by local councils for mixed use, including residential. Coupled with this, there may be scope for a land tax to be introduced in order to promote more efficient land use. While Ireland currently has various taxes on property, such as commercial rates, a local property tax, a vacant site levy and stamp duty (all levied on the market property value), there is no pure land tax levied on site value. Aside from encouraging better land use, a pure land tax has hardly any distortionary effect on the investment decisions of households and businesses (Blöchliger, 2015). Indeed, some existing levies such as commercial rates that may distort the pattern of firm growth (discussed further in the thematic chapter) could be replaced by a land tax at a uniform rate. This could be done in a revenue neutral way, but would require new methods that allow land valuations to be separated from the value of improvements (Blöchliger, 2015). Other European countries, such as Denmark and Estonia, currently levy a land tax on site value.

Improving environmental sustainability

Air quality in Ireland is among the highest in the OECD, as Ireland has little polluting industry, few large conurbations, and dominant winds that come from the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 18, Panel C). Ireland's emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) per capita are below the OECD average and have been declining for some years (Figure 18, Panel A), first as electricity generation moved towards gas-fired power stations and more recently as use of renewables has increased. Nevertheless, there is scope to raise the share of energy that is sourced from renewables. Under the EU Renewable Energy Directive, Ireland is aiming to raise the share of renewable energy in total energy consumption from 8.6% in 2014 to 16% in 2020.

Figure 18. Green growth indicators are mixed

Household waste generation has been declining but remains higher, per capita, than the OECD average (Figure 18, Panel D). Increasing amounts are being recycled, but more waste is sent to landfill than in most EU countries (Central Statistics Office, 2016). The amount of waste sent to landfill increased between 2015 and 2016, requiring the government to make additional landfill space available. Continuing to transition away from landfill should be an ongoing focus of policymakers.

Ireland’s water infrastructure is a key environmental investment priority. Wastewater treatment facilities in many locations are incapable of meeting EU standards, negatively impacting upon the quality of waterways and the health of the population (Expert Commission on Domestic Public Water Services, 2016; European Commission, 2017c). It has been estimated that almost half of treated water is lost through leakage in the network, around double the share lost through leakage in the UK (Irish Water, 2015). Furthermore, boil water notices for households continue to be invoked due to contamination in some regions. According to the Environmental Protection Authority, as at mid-2017, the water supply serving around 15% of the Irish population was immediately at risk and required remedial action. It is estimated that investment of close to 14 billion euro will be required by Irish Water between 2018 and the mid-2030s to bring the infrastructure up to an acceptable standard. With the abolition of household water charges in early 2017, further investment will largely derive from general taxation (along with some fees from charges to non-domestic customers). The government should keep reviewing the regime for domestic water charging in order to ensure funding certainty to Irish Water over the medium-term.

In making further investments in environmental infrastructure, measures that improve public spending efficiency – which is below the EU average (IMF, 2017) – need to be identified. For instance, there should be better efforts to systematically collect information on the financial and non-financial performance of existing assets. A lack of sufficient data has been one reason behind suboptimal capital investment decision-making in the water sector (Irish Water, 2015), but asset data has been similarly absent when making decisions about other types of infrastructure. The government has prepared a medium-term Public Capital Investment Plan, which is coordinated and aligned with the National Planning Framework. In future infrastructure planning, project evaluation and the assessment of maintenance costs will greatly benefit from better information about the performance of existing infrastructure assets. There may also be scope for improvements to the institutional framework to ensure the capital projects undertaken have the highest societal returns. For example, prior to project development, a mandatory process of consulting with future users should be put in place.

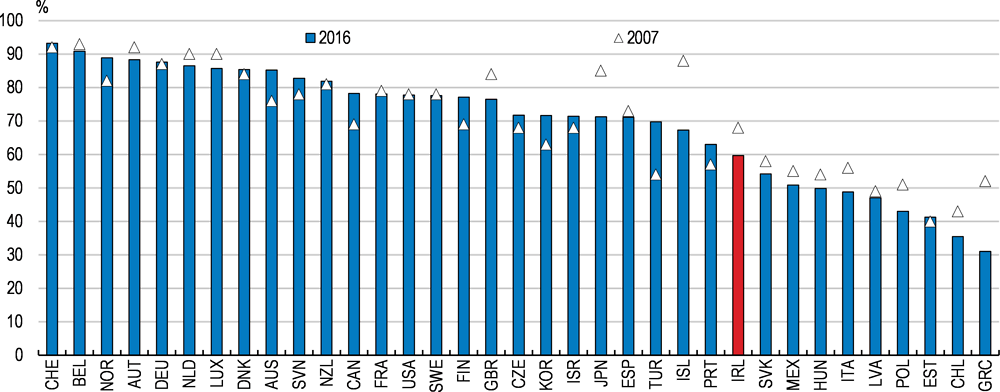

Expanding the provision of quality healthcare

A high performing health system is also integral to supporting labour force participation and the overall wellbeing of the Irish population. Demographic projections suggest the dependency ratio will rise in Ireland, with the number of people aged over 50 projected to increase by 600 thousand (equivalent to 13% of the 2016 population) between 2016 and 2031. However, the health system already struggles to meet the needs of the population. Citizen satisfaction with healthcare was lower than in most OECD countries in 2016 (Figure 19) and has fallen since 2007. The reduction in satisfaction coincides with falling public health expenditure through the crisis (Nolan et al., 2015). Furthermore, there are inequalities in the health system, with the gap in health status between high and low income individuals greater than in the average OECD country (OECD and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017).

Figure 19. Many Irish people are unsatisfied with the health system

Proportion of people satisfied with the availability of quality healthcare

Unlike most OECD countries, Ireland does not have universal coverage for primary healthcare. Low income households are eligible for a Medical Card which enables them to access general practitioner care and medicines free at the point of use (subject to a very small prescription charge). Visits to general practitioners are also free for children under the age of six and adults over 70. While roughly half the population have private health insurance, health insurance premia are high (Pacific Prime, 2016) and co-payments are applied on a broad range of services, including primary care (OECD and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017). Consequently, health costs can be prohibitively high for a group of the population with earnings that are below average but who are ineligible for free services.

In addition to high costs, access to healthcare is impeded by a congested hospital system that results in very high waiting times (OECD, 2016a; Figure 20). Those without insurance may find it particularly difficult to get adequate care, given that private health insurance patients get faster access to care within the public system in some cases (Committee on the Future of Healthcare, 2017). Furthermore, medical consultants in public hospitals may focus disproportionately on those with insurance as they are paid on a fee per service basis for treating such patients (rather than on a salaried basis for public patients; Department of Health, 2014). This two-tiered system of care is a factor behind the high inequalities in health status.

Figure 20. There are lengthy waiting times for medical procedures

Days waiting time for patients registered for a procedure, 2016 or latest available

Note: The figure shows the average waiting time across a variety of procedures; cataract surgery, coronary bypass, prostatectomy, hysterectomy, hip replacement and knee replacement. Data are for 2015 for New Zealand and 2016 for all other countries.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017.

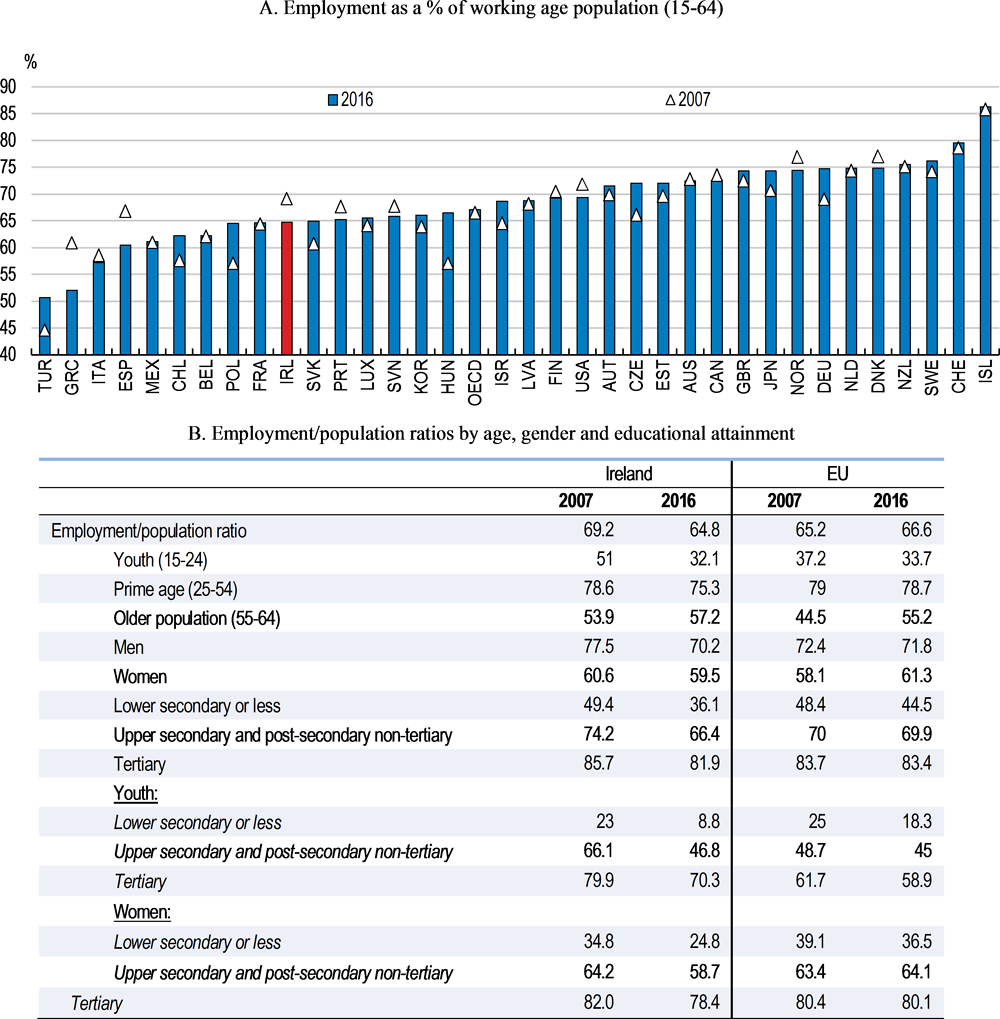

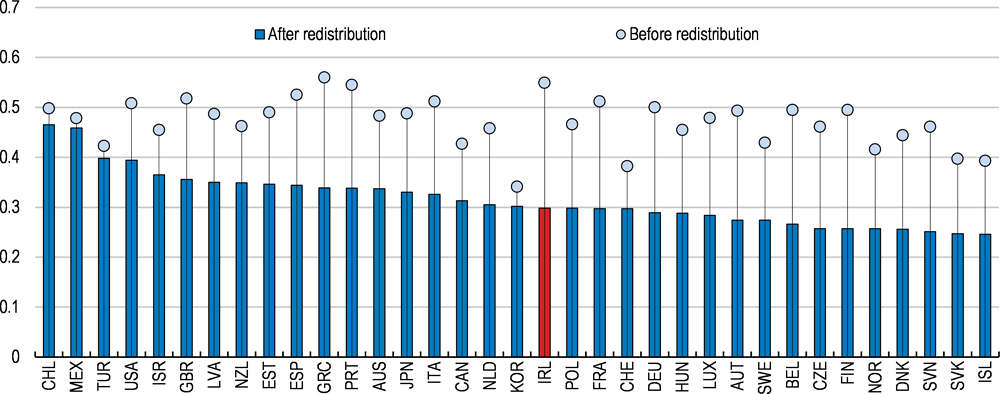

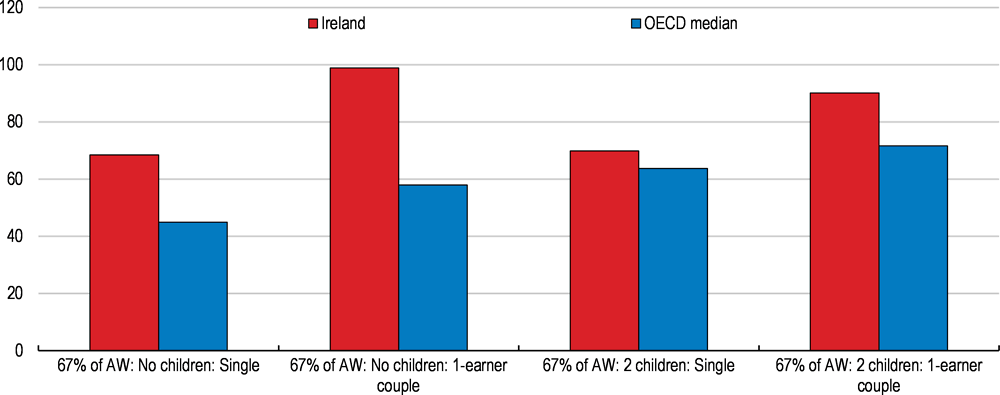

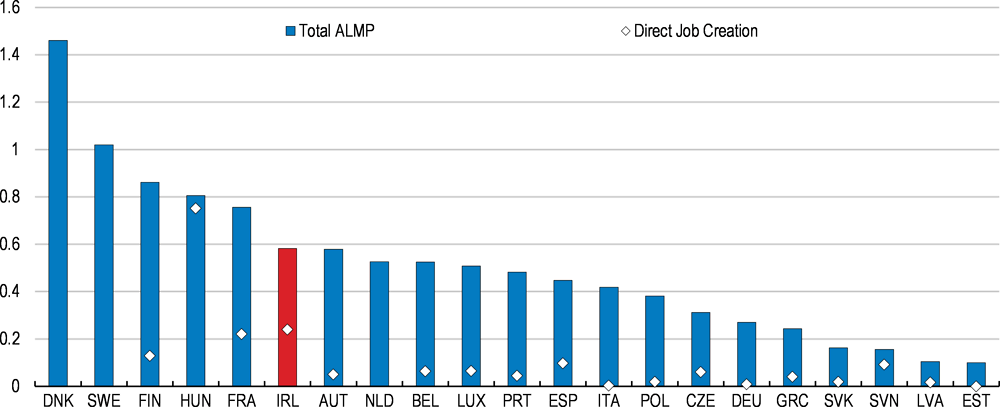

In recognition of these challenges, a cross-party committee was established with the aim of outlining a plan to provide broad access to quality health services within a single-tier health system. In May 2017, the committee delivered a final report, which had several recommendations that should be strongly considered by the government. These included the provision of a new health card (“Carta Slainte”) to all Irish people that would give access to publicly funded health and social services. To also meet burgeoning demand, there should be a rise in investment into health infrastructure and staffing. Taking into account inflation and changing demographics, implementing the plan would require an increase in funding of at least 7% each year for 5 years, as well as an additional 3 billion euro in transitional funding. The report envisioned that this would be met through general taxation, with direct payments by households contributing a lower share of health costs.