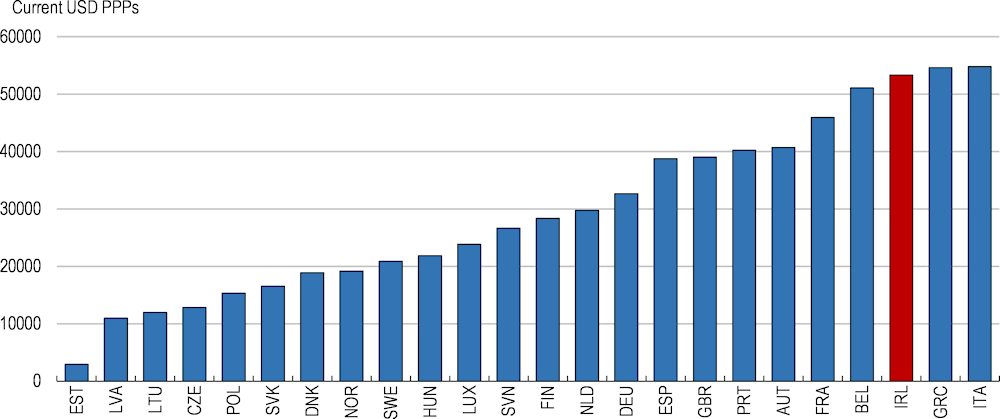

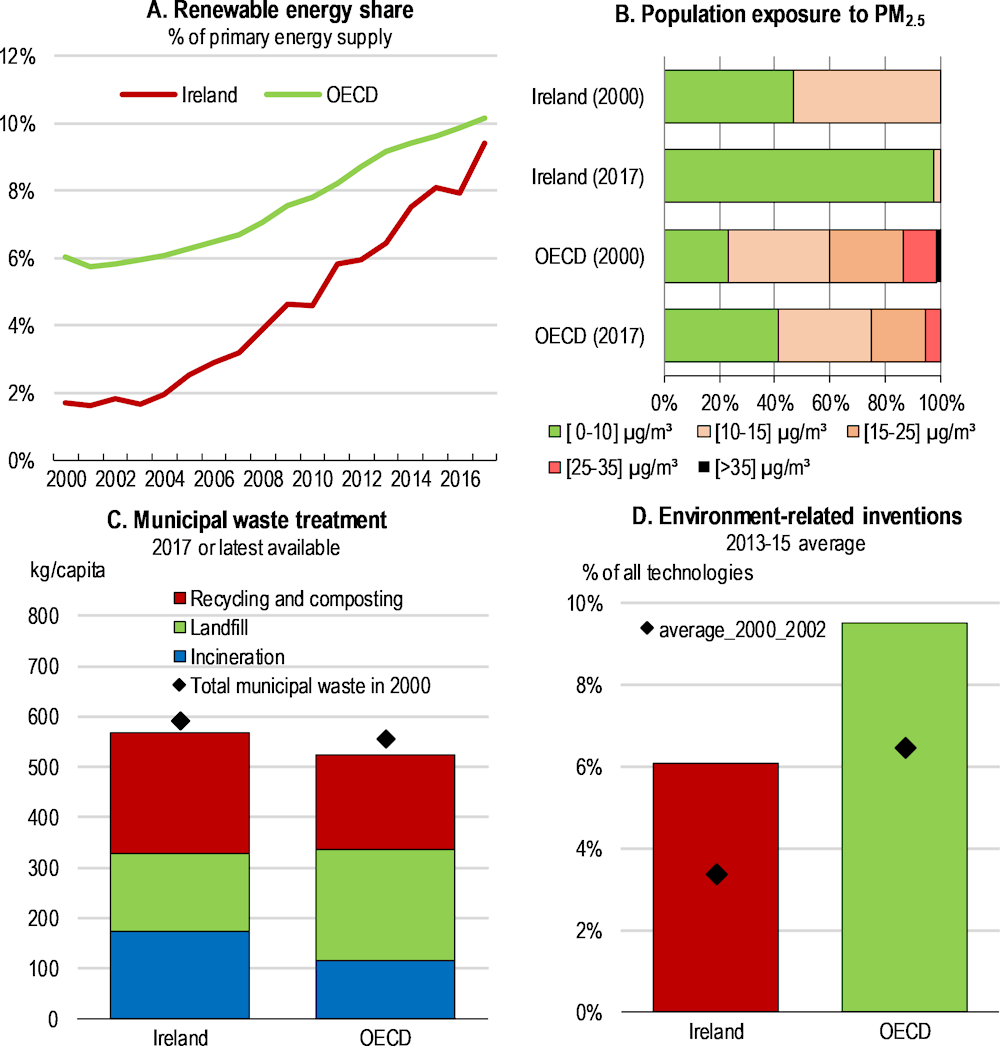

Ireland’s living standards remain high (Figure 1.1, Panel A). Growth has been strong, despite bouts of volatility. The average real wage was on par with the OECD average in the mid-1990s, but now stands more than 15% above. Furthermore, a highly redistributive tax and transfer system has contained income inequality in disposable incomes (Figure 1.1, Panel B).

OECD Economic Surveys: Ireland 2020

1. Key policy insights

Figure 1.1. Rising Irish incomes have been shared through the tax and transfer system

Note: In Panel B, data are for 2017 or the most recently available year.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database; OECD Income Distribution database.

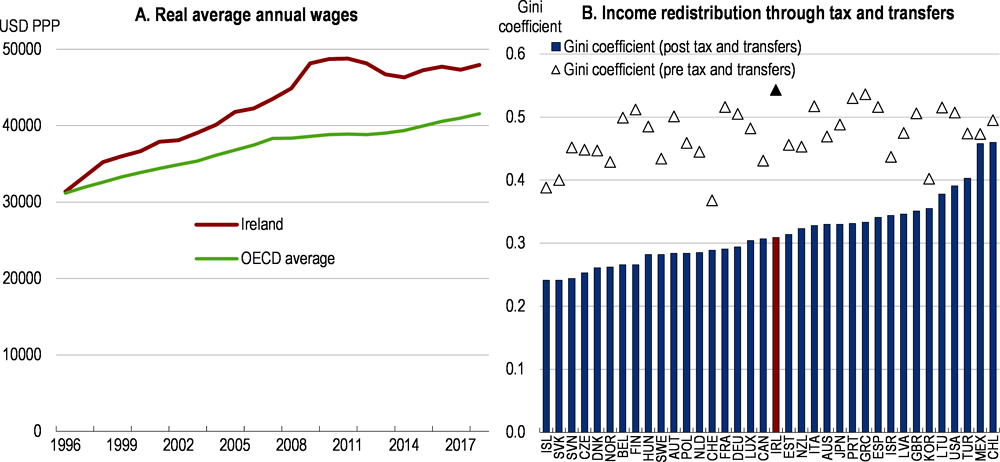

The population also benefits from a high level of wellbeing across other dimensions (Figure 1.2). Life satisfaction is high, according with the strong economy as well as other features such as low levels of pollution, strong community engagement and high perceived personal security. Performance in education depends less on socio-economic status than in most other OECD countries. The gender wage gap is also one of the lowest in the OECD, having declined markedly over recent decades. Ireland continues to be an attractive destination for foreign direct investment, with a stable political system, a relatively-young English-speaking population and a supportive regulatory and tax regime. Looking forward, the country is well positioned to take advantage of the opportunities presented by technological change, though there are various challenges that need to be carefully navigated.

Figure 1.2. Wellbeing is high across multiple dimensions

Dimensions of wellbeing, Index (50=OECD median performer)

Note: Education inclusiveness is based on the measure of variation in reading performance explained by a student’s PISA index of economic, social and cultural status. Data for the gender wage gap are for 2017 or the latest available year for each country used.

Source: OECD Better Life Index database; OECD Gender Data Portal; OECD PISA 2018 database.

The impressive economic growth of recent years has contributed to the economy beginning to run up against capacity constraints, with some skill shortages and strains on key infrastructure. The population is ageing, with the number of people aged over 65 outpacing that of the prime working age cohort since 2008. The structure of the economy is also undergoing sizeable change. Businesses located in Ireland have been keener to embrace new technologies than their counterparts in most other OECD countries, but the impact on productivity growth in most firms has been modest so far. These trends unfold against a backdrop of heightened global uncertainty and with scars of the financial crisis, notably high general government debt, fragilities in the banking sector and high long-term unemployment (Figure 1.2), still apparent.

The authorities have compiled a reform programme in response to these various challenges. Public investment decisions are to be aligned with a country-wide planning framework, Ireland 2040. In addition, Future Jobs Ireland set out a strategy to support businesses in embracing productivity-enhancing technological change and transitioning to a low-carbon economy, while promoting greater labour force participation and skill accumulation. With the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union in prospect, the authorities have also been putting in place a variety of supports for those Irish firms likely to be most affected.

In this context, the main messages of this Economic Survey are:

Government finances have improved markedly, but ongoing fiscal prudence is needed given ageing-related fiscal costs will substantially rise and high uncertainty in the global outlook.

Emerging capacity constraints can be mitigated by expanding supply. This can be enabled by raising labour force participation and reinvigorating productivity growth.

Further technological adoption by businesses will boost productivity if complementary improvements in skills are achieved. Policy settings in other areas, including competition and the labour market, need to be revisited as new technologies spread.

Recent macroeconomic developments and short-term prospects

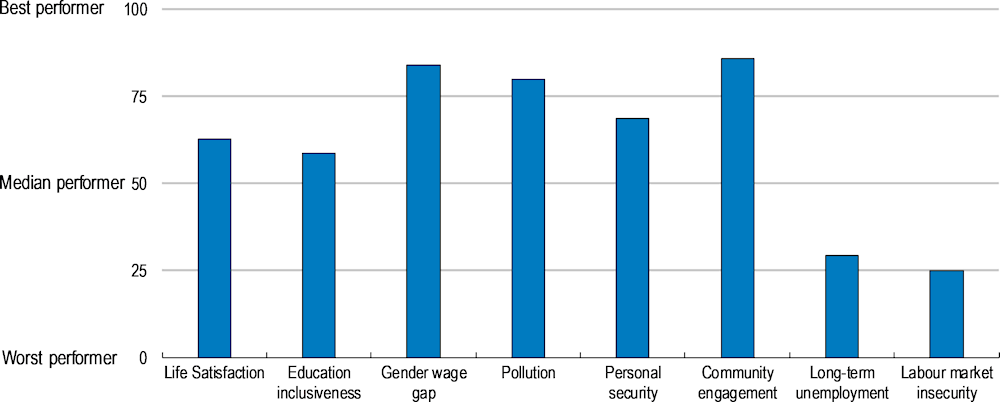

Economic performance has remained impressive, despite various uncertainties. Irish national accounts have been heavily distorted by the activities of multinational corporations in recent years, leading the authorities to develop new analytical measures, such as modified gross national income (GNI*; see the 2018 OECD Economic Survey of Ireland for a full description) and modified domestic demand.

Over the past year, modified domestic demand grew by around 3% (Figure 1.3). While investment activity has softened somewhat, private consumption growth has been solid. Exchequer tax receipts that are sensitive to the economic cycle, such as those related to income tax and value added tax, have been rising strongly.

Figure 1.3. The economy continues to expand vigorously

Annual percentage change

Note: The series are based on a trailing four-quarter average. Modified final domestic demand and modified gross domestic fixed capital formation are underlying measures of economic activity as they exclude the impact of volatile items that have little connection with the real economy such as trade in aircraft by aircraft leasing companies and trade in R&D and intellectual property.

Source: CSO, OECD calculations.

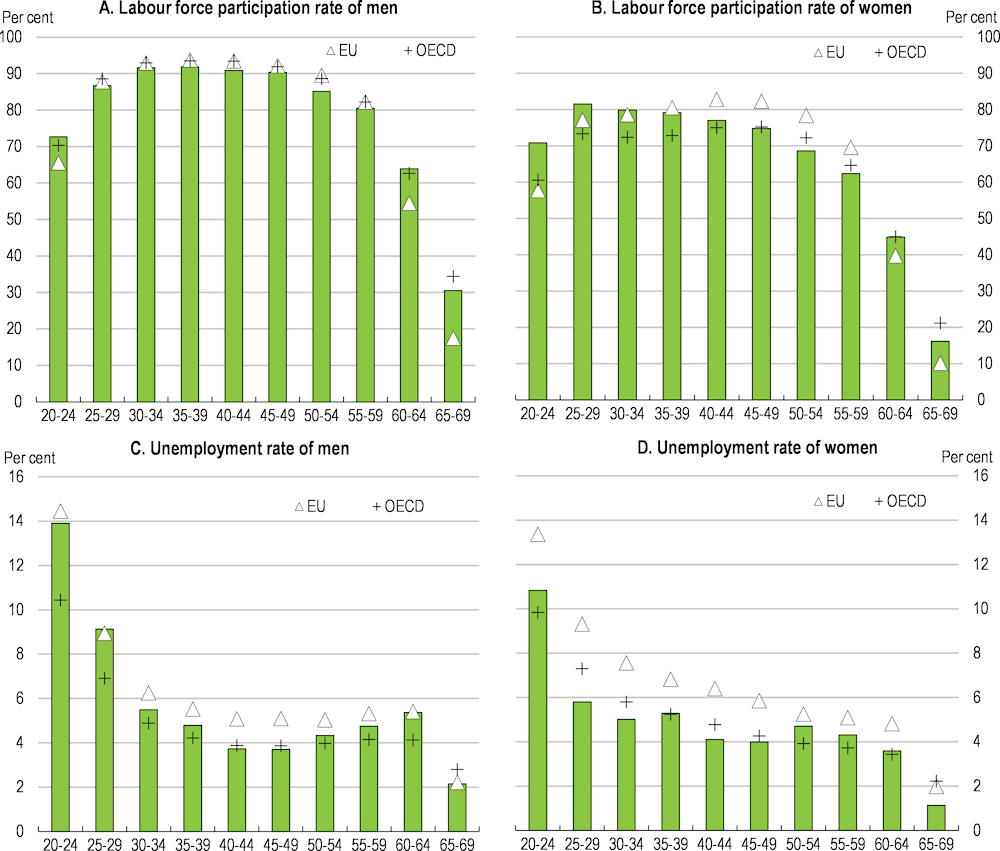

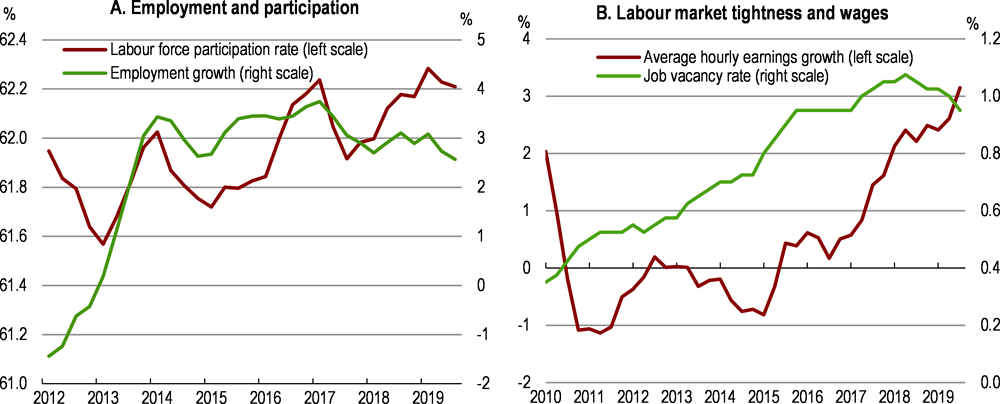

Buoyant consumption growth has reflected labour market strength. Total employment has risen by around 3% annually since 2013, driven fully by an increase in full-time employees. Brighter prospects have induced higher labour market participation (Figure 1.4, Panel A), especially for those of prime working age (25-54). Nevertheless, labour force participation remains four percentage points below the peak reached just before the financial crisis. Immigration plummeted between 2007 and 2010 but has resumed since, while fewer Irish emigrated. Net immigration has thus been positive and growing since 2015. Even so, the labour market has tightened with the continued decline in the unemployment rate. Indeed, the job vacancy rate has risen, putting upward pressure on wages. Average hourly wages have been growing by an annualised rate of 2½% in the past few years (Panel B), partly feeding into prices, particularly in services. Inflation would have been stronger over the past few years, if not for the appreciation of the euro against the British pound since the result of the Brexit referendum in 2016 (Economic Social and Research Institute, 2019).

Figure 1.4. Labour market conditions have strengthened

Note: In Panel A, employment growth is calculated as annualised percentage change from quarterly data and the labour force participation is the four quarter moving average. In Panel B, average hourly earnings growth is calculated as annualised percentage change from quarterly data and the job vacancy rate is the four-quarter moving average.

Source: CSO, OECD calculations.

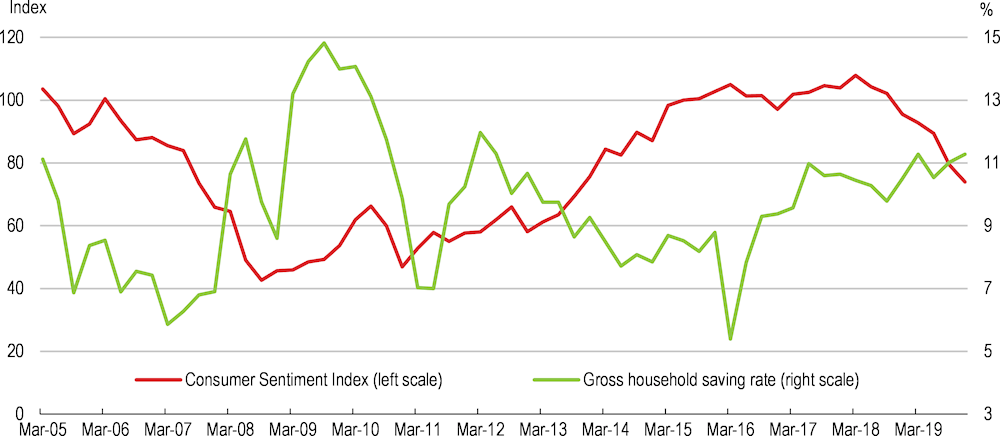

Consumer spending would be even stronger, were it not for high uncertainty. Consumer sentiment is at its lowest level since 2014 and households’ saving rate has risen since the mid-2010s (Figure 1.5). Total credit extended to the sector has also fallen, though this mostly reflects a contraction in credit for house purchases amid tighter macroprudential lending standards.

Figure 1.5. Consumer sentiment has begun to ease amid uncertainty

Indicators of household saving and consumer sentiment

Note: The measure of consumer sentiment is calculated as quarterly averages of monthly readings.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database, Economic Social and Research Institute (ESRI).

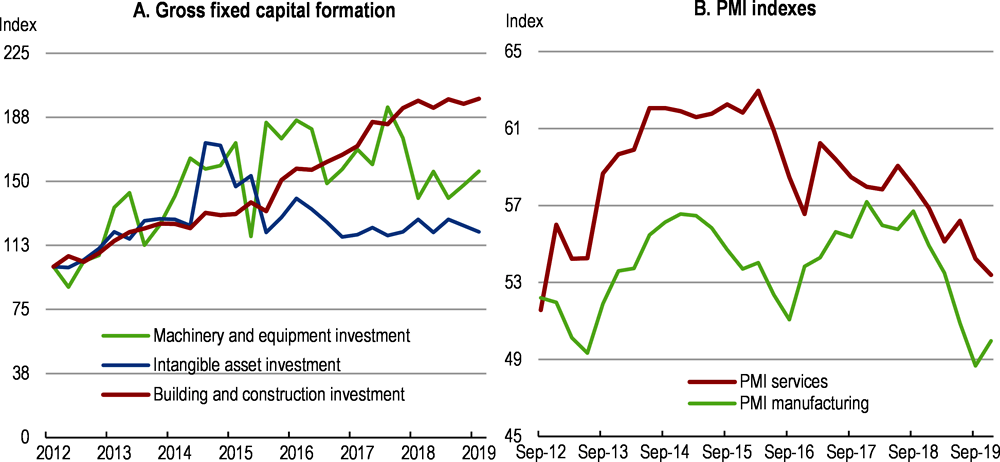

Investment activity continues to be driven by strong growth in housing construction (Figure 1.6, Panel A), a catch-up following the collapse in dwelling supply during the financial crisis (OECD, 2018a) and in the face of population growth. New dwelling completions rose by around 20% in the first three quarters of 2019 compared with a year earlier. Around 21,000 dwellings were likely completed in the full year, contributing to slowing house prices, especially in Dublin. Nevertheless, dwelling rents have continued to rise rapidly and projected demographic changes suggest further increases in the number of new homes is required: the central bank recently estimated that around 34,000 homes are needed each year to 2030 assuming continued high migration and no change in household formation rates (Conefrey and Staunton, 2019). The authorities established new institutions and revised planning guidelines in accordance with several of the recommendations in the 2018 OECD Economic Survey of Ireland aimed at raising housing supply (Table 1.1; also see Chapter 2).This should continue to be a focus for policymakers.

Table 1.1. Past recommendations on increasing housing supply

|

Recommendations in previous Survey |

Actions taken since March 2018 |

|---|---|

|

Encourage local councils to rezone underutilised sites as residential. |

An independent Office of the Planning Regulator has been established to ensure that the zoning and planning decisions of local authorities are aligned with the National Planning Framework and that planning systems are functioning in a coherent way. |

|

Relax building regulations in urban centres relating to minimum dwelling sizes and bans on north-facing apartments. |

In March 2018, the Department of Housing published new guidelines for planning authorities on new apartments titled; “Sustainable Urban Housing: Design Standards for New Apartments”. The new guidelines allow for the construction of north-facing apartments where necessary. |

|

Protect debtors against slipping into poverty by continuing to raise the social housing stock. |

In Budget 2020, the housing budget was increased by almost €300 million to €2.6 billion. The increase included an additional €20 million for homeless services. |

Figure 1.6. Construction activity has been supporting investment

Note: Panel A presents data on gross domestic fixed capital formation. The machinery and equipment component excludes investment in aircraft related to leasing and the intangible assets component excludes R&D service imports and trade in intellectual property. The excluded components tend to be distorted by the activities of multinationals. In Panel B, data are on a three-month moving average basis.

Source: CSO, Markit Economics.

Other building and construction spending has also been robust, partly reflecting public projects under the Ireland 2040 plan. In contrast, investment in non-aircraft machinery and equipment and intangible assets has stagnated since 2015 amid heightened global economic and political uncertainty. This accords with a continued decline in bank lending to small and medium enterprises. In recent months, purchasing managers indexes have weakened, especially for the manufacturing sector (Figure 1.6, Panel B), portending softer private business investment.

Fiscal policy has been expansionary over the past year, with strong public capital spending and steadily growing government consumption. The estimated underlying primary budget balance fell by around ½ per cent of GDP in 2019, suggesting that the increase in the headline budget balance was entirely attributable to stronger cyclical conditions and interest rate developments.

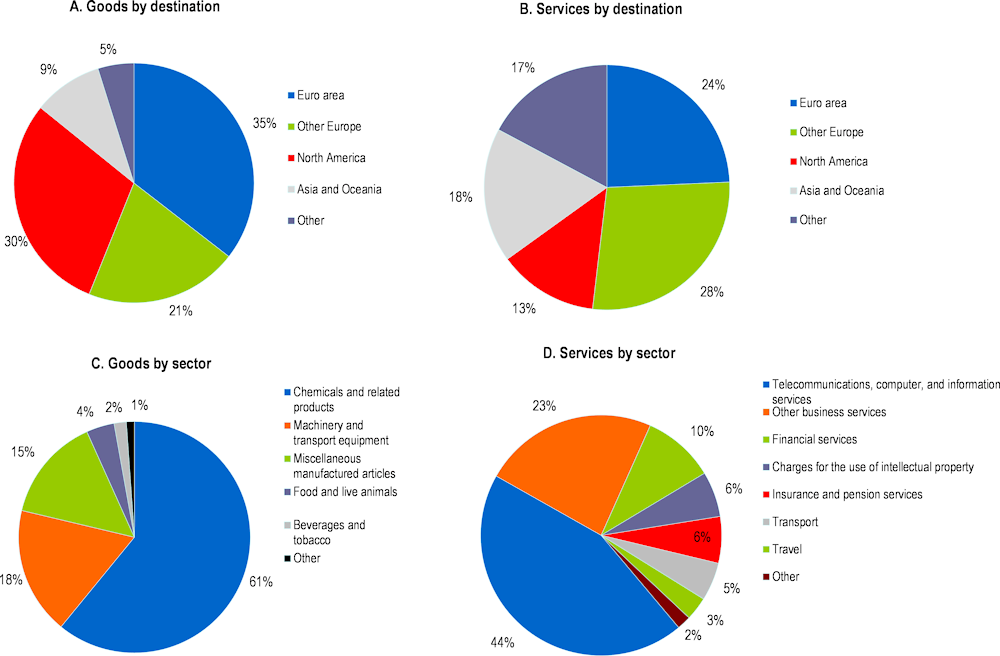

Ongoing export momentum has also supported the domestic economy. Services exports have soared over recent years, mostly driven by computer services. The services sector now accounts for around half of all Irish exports. Merchandise exports have expanded more moderately, partly due to the slowdown in the European economies that are the major markets for such goods (Figure 1.7, Panel A).

Figure 1.7. The majority of Irish exports are bound for Europe

Share of exports by sector and destination

Note: Data presented in Panels A, B and D are for 2017. Data presented in Panel C are an average over 2016-18.

Source: OECD International Trade Statistics.

Despite robust aggregate export growth, the United Kingdom’s planned departure from the European Union (“Brexit”) and slowdown have started to affect Irish trade in some sectors. The United Kingdom accounts for 14% of all Irish exports. Exports of machinery and equipment, chemicals and tourism to Ireland’s large neighbour have either stagnated or fallen since the UK referendum on EU membership in 2016. The 2018 OECD Economic Survey of Ireland presented estimates derived from the OECD METRO model that suggested Irish exports in some sectors such as agriculture and food could fall by around 20% in the event of a trade arrangement between the UK and EU governed by the World Trade Organisation’s Most-Favoured Nation Rules. So far, however, there is not clear evidence of significantly weaker exports in these sectors resulting from Brexit uncertainty (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019a).

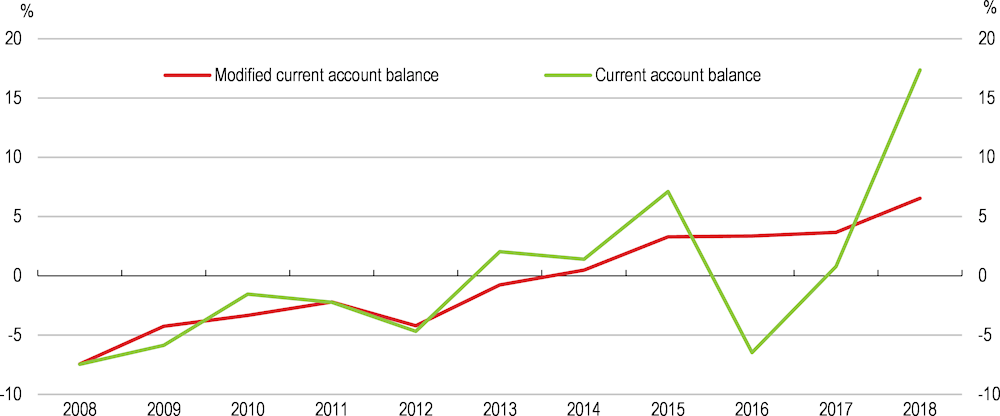

Overall, the Irish economy has gained competitiveness and external imbalances have declined in recent years. The growth in Irish exports has outpaced the expansion in Irish export markets, signalling gains in export market share. Ireland’s current account is volatile and heavily influenced by the activities of multinationals. However, in underlying terms, it has moved from a deficit of 7½ per cent of GNI* in 2008 to a surplus of 6½ per cent in 2018 (Figure 1.8). Although the current account surplus has been inflated by recent unexpectedly high corporate tax revenues, it would have still recorded a surplus of around 4% of GNI* in 2018 if windfall corporate tax receipts from 2015 to 2018 were excluded (Department of Finance, 2019a).

Figure 1.8. The current account has moved into surplus

Current account balance, percentage of GNI*

Note: The modified current account balance adjusts for three main distortions affecting the interpretation of the headline current account: intellectual property imports, imports of aircraft related to leasing and profits of companies that establish a legal presence in Ireland while investing little in the country.

Source: CSO, OECD calculations.

Looking ahead, on the assumption of an orderly Brexit (i.e. the transition period is assumed to end smoothly), economic growth is set to moderate but remain slightly above estimated potential output growth (Table 1.2). Lingering Brexit-related uncertainty will constrain business investment and private consumption. Housing–related construction and public capital projects will continue to support the economy, although mounting capacity constraints may hinder growth in these areas. The unemployment rate will continue to fall to historically very low levels with wage pressures building. As higher wages further feed into prices, competitiveness will deteriorate absent a resurgence in productivity growth. A slowdown in demand in Ireland’s major trading partners will also contribute to lower export growth.

In the event of an orderly Brexit, fiscal policy is expected to exert a broadly neutral influence on economic conditions. Given that the economy is expected to grow slightly above estimated potential output growth and that euro area monetary policy settings are exerting a stimulatory effect, fiscal policy should be tightened to have a slightly contractionary influence. That said, the high level of uncertainty at present means that the authorities should prepare to make further counter-cyclical adjustments to fiscal policy settings if either upside or downside shocks eventuate.

The risks to the economic outlook are tilted to the downside. The exact impact of Brexit on the economies of the United Kingdom and European Union is highly uncertain and depends on the nature of any trade arrangement eventually agreed, but a sharp slowing in demand from these areas will notably weaken the Irish economy given its high dependence on trade. The re-imposition of customs and border controls and additional administrative burdens along the UK “Land Bridge” has the potential to significantly increase costs for traders (Box 1.1). The Irish Maritime Development Office estimate that over €21 billion of trade was carried out via the UK Land Bridge in 2016. Furthermore, beyond the central forecast scenario and its associated risks, a disorderly resolution to the Brexit transition process, a ratcheting up of trade policy tensions directly involving European economies and an oil supply shock would considerably alter the outlook (Table 1.3).

Box 1.1. Irish trade and the United Kingdom “Land Bridge”

The United Kingdom “Land Bridge” is a term used to describe a route that connects importers and exporters in Ireland to international markets via the United Kingdom road and ports network. It is a strategically important means of access to Ireland’s main export markets in the European Union as it delivers transit times at least twice as fast as alternative routes. As a result, the Land Bridge has typically been favoured by traders in perishable goods, those that rely on speed of delivery as a competitive advantage and those that trade in high value added goods where shorter transit times reduce working capital requirements.

A recent study by the Irish Maritime and Development Office produced an estimate of the volume of Irish trade that uses the Land bridge to access the European Union. In 2016, it was estimated that around 40% of Irish exports in both volume or value terms travelled via the Land Bridge. In addition, around 13% of Irish import volumes and values used the route.

Source: Breen, et al. (2018).

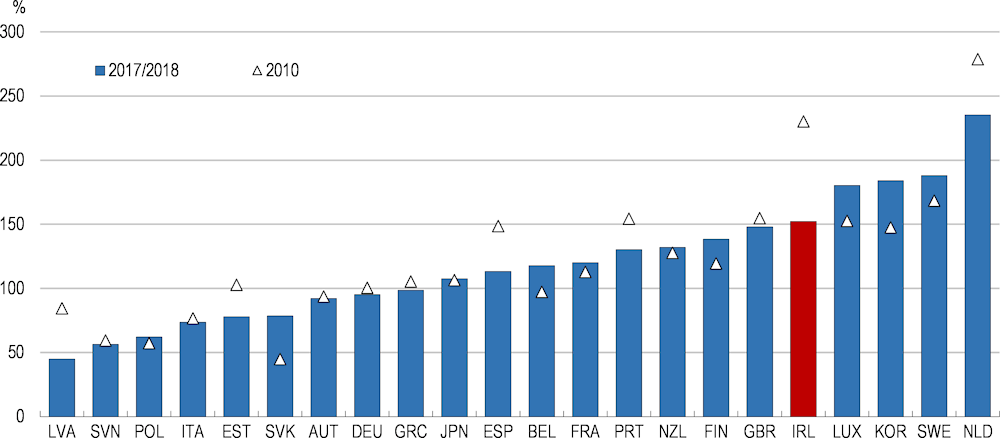

If negative risks eventuated, some of the Irish economy’s vulnerabilities could compound the pain. Legacies of the financial crisis could also amplify a negative economic shock. The debt burden of the household sector remains high by cross-country standards, though it has declined notably over the past decade (Figure 1.9). Public sector debt is also still high and fragilities in the financial sector remain a source of concern for policymakers (both discussed further below). A great asset to the Irish economy, but also a vulnerability, is the high share of foreign-owned firms in the business sector. They currently account for around one in five jobs in Ireland (both direct and indirect effects) and the bulk of corporate tax revenues. The 2018 OECD Economic Survey of Ireland documented a large positive productivity gap between foreign-owned and locally-owned firms in the Irish economy. Furthermore, foreign-owned firms primarily source inputs from abroad (OECD, 2020a), with such firms in key sectors like chemicals and computer, electronic and optical products sourcing less than 10% of their materials within Ireland. Foreign-owned firms are internationally mobile and a fading of their desire to locate in Ireland could weigh heavily on the economy. Rising international tax competition as well as new international tax agreements as part of the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process (discussed further below) could influence the future location decisions of foreign-owned firms.

While corporate debt is high by international standards, it is inflated by the debt of large multinational enterprises to foreign counterparties that are often within the same corporate group. Abstracting from these liabilities, Irish corporate debt is roughly in line with that in other European countries (Department of Finance, 2019b).

Table 1.2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

|

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ireland |

Current prices EUR billion |

Percentage changes, volume (2017 prices) |

||||

|

GDP at market prices |

271.4 |

8.2 |

8.3 |

6.2 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

|

Private consumption |

91.8 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.1 |

2.6 |

|

Government consumption |

33.5 |

3.5 |

4.4 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.1 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

96.4 |

-7.6 |

-20.0 |

41.8 |

-18.3 |

4.4 |

|

Final domestic demand |

221.6 |

-0.4 |

-4.8 |

20.3 |

-4.4 |

3.5 |

|

Stockbuilding |

7.1 |

1.5 |

-2.6 |

0.6 |

-2.3 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

228.7 |

9.5 |

-6.1 |

19.3 |

-7.7 |

4.3 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

328.0 |

9.1 |

10.5 |

11.3 |

5.4 |

3.5 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

285.3 |

0.8 |

-2.7 |

23.0 |

-0.3 |

4.5 |

|

Net exports |

42.7 |

10.2 |

15.3 |

-6.6 |

7.3 |

0.2 |

|

Memorandum items |

||||||

|

GVA, excluding sectors dominated by foreign-owned multinational enterprises |

_ |

4.8 |

3.9 |

4.8 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

|

GDP deflator |

_ |

1.1 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

|

Harmonised index of consumer prices |

_ |

0.3 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

|

Harmonised index of core inflation |

_ |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

_ |

6.7 |

5.7 |

5.0 |

4.8 |

4.7 |

|

Output gap (% of potential GDP) |

_ |

-2.7 |

1.7 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

_ |

6.0 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

|

General government financial balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

|

Underlying government primary balance (% of potential GDP) |

_ |

2.6 |

1.1 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP) |

_ |

77.4 |

76.0 |

71.0 |

66.2 |

64.9 |

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition (% of GDP) |

_ |

67.8 |

63.6 |

58.6 |

53.8 |

52.5 |

Note: Projections are based on the assumption of an orderly Brexit process, whereby the transition period ends smoothly. The values for stockbuilding are contributions to changes in real GDP (in level in the first column). The forecast assumption for exports is that contract manufacturing activity (exports of goods produced abroad under contract from an Irish-based entity) by multinational enterprises is assumed to remain at the 2019 level in 2020 and 2021. GVA stands for gross value added.

Table 1.3. Low probability events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Disorderly Brexit process |

It is possible that the Brexit transition process could conclude without an agreement on the future relationship between the United Kingdom and European Union. A significant increase in barriers governing relations with the UK and a major slowdown in that economy could have large negative economic effects on Ireland. |

|

Ratcheting up of trade policy restrictions |

As a small open economy that is a hub for commercial transactions between the United States and Europe, Ireland is particularly exposed to any ratcheting up of trade policy tensions. |

|

Oil supply shock |

Any interruption to global oil supply that causes an increase in oil prices will negatively impact consumer demand and competitiveness. While the energy intensity of Irish production is low, the country has no domestic oil production and depends heavily on oil for transport and heating. |

|

A repricing of global risk premia |

A sudden drop in global risk appetite could lead to a rise in interest rates and declining asset values. Irish financial firms have direct exposure to global financial markets, including the global leveraged loan market, and the indebtedness of the household and public sectors remains high. |

Figure 1.9. Household debt remains high

Household debt as a share of net disposable income

Note: The blue bars present the latest available data point, which corresponds to either 2017 or 2018.

Source: OECD Resilience database.

Safeguarding financial stability

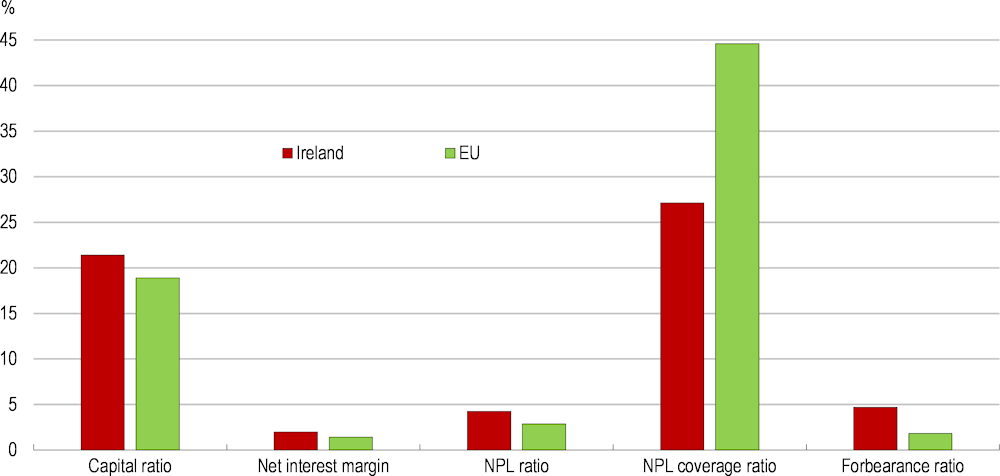

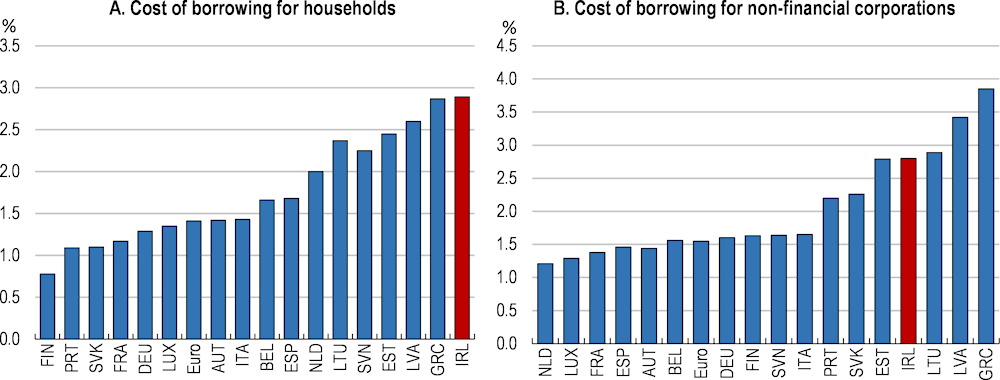

The Irish banking sector has deleveraged markedly since the financial crisis, with balance sheets having contracted by around 60% since 2009. More stable sources of funding now make up a larger share of liabilities and banks have become more resilient to shocks. The leverage ratio (the ratio of core capital to total assets) was close to double the average EU value in early 2019, with the retail banking sector having twice as much Tier 1 capital relative to risk weighted assets as in 2010. Interest margins are relatively comfortable (Figure 1.10), mainly due to lower funding costs and interest rates on mortgage loans and SME loans that are higher than in other countries (European Commission, 2019a).

The results of 2018 EU-wide stress tests suggest that Irish banks could weather a significant downturn. The tested banks had enough capital to remain solvent in the event of Europe-wide recession, while maintaining lending to the rest of the economy in line with debt repayments from borrowers. The Central Bank of Ireland has actively deployed macroprudential policy measures to buttress the stability of the financial system. Since 2015, macroprudential mortgage rules such as loan-to-value and loan-to-income limits have been applied. A countercyclical capital buffer is currently set at 1% and additional capital buffers are applied to six supervised institutions identified as systemically important.

The Central Bank recently opted to maintain the regulated loan-to-income and loan-to-valuation limits for 2020. The measures have become increasingly binding as housing prices outpaced incomes (Kelly and Mazza, 2019). With a housing market that continues to suffer from supply constraints, this signals that the measures are working as intended: encouraging mortgage lending that reflects borrower’s debt servicing capacity and leaning against the conditions for another credit-fuelled boom-bust housing cycle to take root. A recent counterfactual analysis estimated that dwelling prices would have been 26% higher in early 2019 if the macroprudential mortgage measures had not been introduced (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019b).

Figure 1.10. Irish banks are well capitalised but the share of non-performing loans remains high

The macroprudential toolkit should continue to be evaluated against emerging risks. The current set of policy measures assume an orderly Brexit scenario. They are also focused primarily on the banking sector, despite the share of non-bank financial institutions having risen dramatically over recent years (IMF, 2019). The development of a systemic risk buffer should be considered, following the agreement of the Minister of Finance to transpose the measure into Irish law and give responsibility to the central bank for its implementation and calibration. If adopted, this tool would allow the central bank to impose additional capital requirements on banks to safeguard the financial system against an idiosyncratic shock. Having the systemic risk buffer in the macroprudential toolkit could be especially important for a very open economy like Ireland that has been prone to volatility in the past.

Irish retail bank profitability has recovered since the crisis. However, a number of the systemically important Irish-headquartered banks are still trading below book value, indicating that market participants are pessimistic about future profitability and asset quality. Costs in Irish banks are inflated relative to other European banks (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019b) and have been rising: the aggregate cost-to-income ratio picked up from 56% in mid-2016 to around 63% in 2019. Downward pressure on net interest margins due to the low interest rate environment and the lingering high stock of non-performing loans (NPLs) on bank balance sheets have also been weakening bank profits.

The NPL ratio fell from around 15% in mid-2016 to 5% in 2019, aided by portfolio sales and improved economic conditions. Moreover, the stock of NPLs more than one year past due halved in the year to June 2019. Nevertheless, the aggregate NPL ratio in Ireland remains elevated compared to European peers (Figure 1.10) and many of the remaining NPLs on bank balance sheets may be difficult to cure (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019c). This partly reflects weak collateral enforceability due to slow repossession proceedings relative to other countries (O’Malley, 2018; National Competitiveness Council, 2019). Repossession is especially slow for primary dwellings (OECD, 2018a) and mortgages tied to such dwellings remain the main source of the remaining NPL stock.

Slow repossession proceedings provide a disincentive for both the borrower and lender to engage in the repossession process. Reflecting this, the proportion of loans granted forbearance in Ireland was over double the European Union average in 2019 (Figure 1.10). Furthermore, over half of the remaining principal dwelling arrears balances are long-term in nature (over 720 days past due). Relatively weak mortgage enforceability in Ireland means that increased provisioning for non-performing housing loans may be needed, especially as such provisions are relatively low in Ireland. Although NPL sales have mostly been at values within provisioning levels, increased provisioning requirements would encourage banks to reduce their stock of NPLs more rapidly and allow them to do so without threatening their solvency. In any case, higher NPL provisions are likely to be required over the coming year as part of the European Central Bank’s Supervisory Expectations for Prudent Provisioning (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019b). European Union regulations have also been amended to introduce minimum coverage (i.e. a “prudential backstop”) for losses caused by future loans that turn non-performing (European Union, 2019).

To further promote non-performing loan resolution, the authorities should also identify measures to speed up repossession proceedings. As discussed in the 2018 OECD Ireland Economic Survey, slow repossession procedures partly reflects high frequency of adjournments of mortgage arrears cases before the courts (OECD, 2018a). The authorities should consider standardising the ‘suspended’ possession order, like in the United Kingdom (CCPC, 2012). This would better encourage engagement between the borrower and lender by granting lenders a collateral possession order for a future date with the suspension of possession conditional on well-defined criteria. Trade-offs exist, as such a policy may have the unintended consequence of encouraging collateral to be run down by debtors. The impact of any such policy change on debtor wellbeing should also be evaluated, with the reform carefully designed to ensure that the benefits with regard to reducing uncertainty and encouraging the provision of finance outweigh any unintended costs.

Table 1.4. Past recommendations on improving financial stability

|

Recommendations in previous Survey |

Actions taken since March 2018 |

|---|---|

|

Introduce regulatory measures to incentivise banks to further reduce non-performing loans. |

The Central Bank of Ireland takes part in the Single Supervisory Mechanism at the European Union level. In March 2018, the European Central Bank published the final version of its “Addendum to the ECB Guidance to banks on non-performing loans: supervisory expectations for prudential provisioning of non-performing exposures”. |

|

Grant creditors a possession order for a future date. |

No specific action taken. |

New financial sector entrants

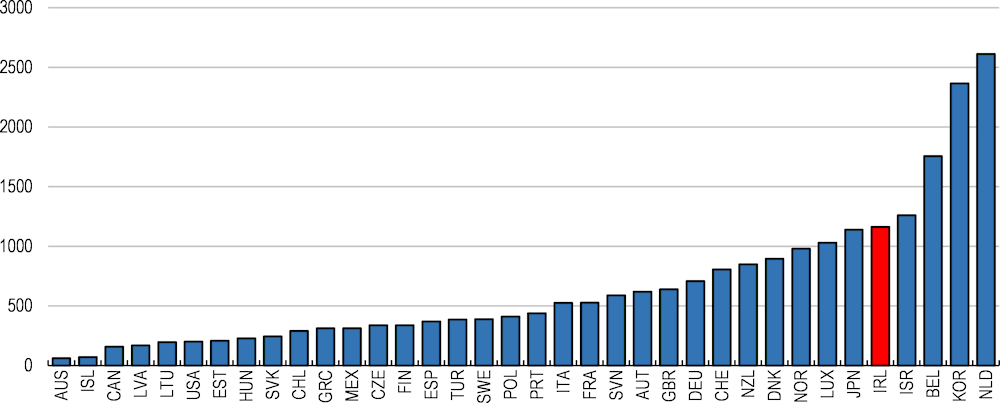

The reduction in the size of bank balance sheets has coincided with strong growth in the non-bank financial sector. Investment funds, the largest part of Ireland’s non-bank financial sector, have increased their balance sheet more than six-fold since the end of 2008. In mid-2019, such funds had assets under management of €2.6 trillion (around 8 times annual GDP).

Most of the exposure to non-bank financing entities lies with non-residents. The assets and liabilities of such entities are reasonably well diversified geographically, though around 30% of their assets and funding are directly related to the United States (IMF, 2019). In recent years, the links between non-banks and the Irish economy have been growing. Irish resident investment funds now hold around one-third of the stock of investable commercial real estate (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019b). Furthermore, domestic banks now invest about 12% of their assets into investment funds and other non-bank financial intermediaries and around 10% of bank funding derives from these sources (IMF, 2019). These tighter links increase the risk that a shock to the non-bank financial sector would affect real economy.

Some segments of the non-bank market are highly leveraged. In particular, real estate investment funds notably increased their leverage over the past five years. This was partly due to the introduction of a 20% tax rate on foreign investors holding shares of funds investing in Irish property, which induced shareholder loans to be increasingly used in place of equity (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019b). As part of Budget 2020, the government introduced limitations on deductions for interest expenses in an attempt to disincentivise high levels of leverage by real estate investment funds. Nonetheless, even after abstracting from the increase in shareholder loans due to the earlier change in taxing arrangements, such funds remain highly leveraged relative to European peers (Central Bank of Ireland, 2019b). A risk is that an increase in market interest rates (for instance, through a sudden drop in global risk appetite) could result in forced sales of real estate assets.

Given the wide variety of entities and activities in the non-bank sector, the authorities must continue to invest resources in monitoring developments and enhancing their capability to conduct robust stress tests of the sector. In doing so, care should be taken not to introduce excessive regulatory burdens that would hold back the development of innovative financial solutions providing alternatives to bank financing. Bank interest rates are relatively high in Ireland (Figure 1.11), partly due to a lack of competition in the financial sector following the financial crisis, so new sources of finance should be encouraged.

Figure 1.11. Market interest rates are high in Ireland

Technology has enabled the entry of new business models of credit intermediation that operate online (“fintech”), such as lending-based crowdfunding and balance sheet lenders (leveraged non-bank institutions that transform risk and maturity). Online alternative financing is quite developed in Ireland relative to most other EU countries (Figure 1.12). Such sources of finance can both introduce competition to the traditional banking sector and provide access to finance for entities that have trouble obtaining credit from traditional banks. For instance, some young entrepreneurial firms that have few physical assets and a limited track record may turn to online alternative financing platforms. The emergence of fintech can reduce the systemic importance of some existing entities. Furthermore, platform intermediation may be less prone to self-fulfilling bank runs than traditional banks as borrowers and lenders are connected directly, meaning that a lender's return does not depend on the actions of other lenders (Havrylchyk, 2018). At the same time, growth in decentralised financial technologies may bring risks to financial stability. For instance, peer-to-peer lending patterns are often prone to pro-cyclicality and pose legal and administrative challenges for recovery resolution (Financial Stability Board, 2019).

Recently, Big Tech companies with a large user base have entered the EU payments market (e.g. Apple Pay, Google Pay and peer-to-peer payments and donations via Facebook Messenger). Some of these have done so by obtaining licenses in Ireland. The scale of the network that Big Tech companies possess makes their potential for disruption to the existing market especially large. Their entry can make cross-border payments less expensive and time-consuming for consumers. Some entrants are adopting a “freemium” business model, by which payment services have no financial cost for users but their data is collected and can be used for advertising and other functions. This information could be used by Big Tech companies to create credit-scoring models that are sold to banks and other loan originators. Past work has highlighted that information from users’ online activity can substantially improve the prediction of default when combined with credit bureau scores (Berg et al., 2018). In principle, better prediction of default would enhance financial stability.

Figure 1.12. Fintech financing is comparatively common

Online alternative finance, 2017

The size of Big Tech firms and their large existing customer network may have adverse consequences for competition in the market. Online payments may be characterised by winner-takes-all dynamics, as the value to customers of a platform is likely to increase with the number of active users. Many Big Tech firms also have considerable gatekeeper power due to their ability to bar other companies from accessing their technological infrastructure (Khan, 2018). While increased market concentration is not necessarily undesirable, policymakers must ensure that incumbents do not defend dominant positions through anticompetitive conduct. This includes through Big Tech companies acquiring smaller innovative firms that could grow into potential competitors.

Only around one-third of fintech firms are regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland or another European country (Enterprise Ireland, 2018) and unregulated entities have no reporting obligations to the regulator. While some of these unregulated firms do not provide financial services, many undertake activities that can have implications for consumer protection, market conduct, payment activities and financial stability. Designing a robust regulatory framework requires intimate knowledge by regulators about emerging business models and risk management practices. An “Innovation Hub” has been launched by the central bank to increase engagement between regulators and fintech firms and has received around six enquiries each month (Central Bank of Ireland, 2018). This should be complemented by ensuring that regulators have the power to obtain relevant information from those unregulated entities in the fintech or Big Tech domains that undertake activities that have implications for the functioning of the financial sector and consumer protection. At the same time, care should be taken to ensure that reporting obligations do not impose an inordinate administrative burden on these firms.

The central bank and competition authorities should also continue to closely monitor the level of market concentration in the non-bank financial sector, especially with the emergence of payment services through Big Tech companies. If such entities launch a new payment service via a subsidiary, the Irish regulators treat the new firm the same way that they would any other start-up. However, given the potential market power afforded to such payment services from the existing network of the parent company, greater scrutiny of the competitive consequences on the market of the firm’s entry is required.

Ensuring fiscal sustainability

Recent fiscal developments

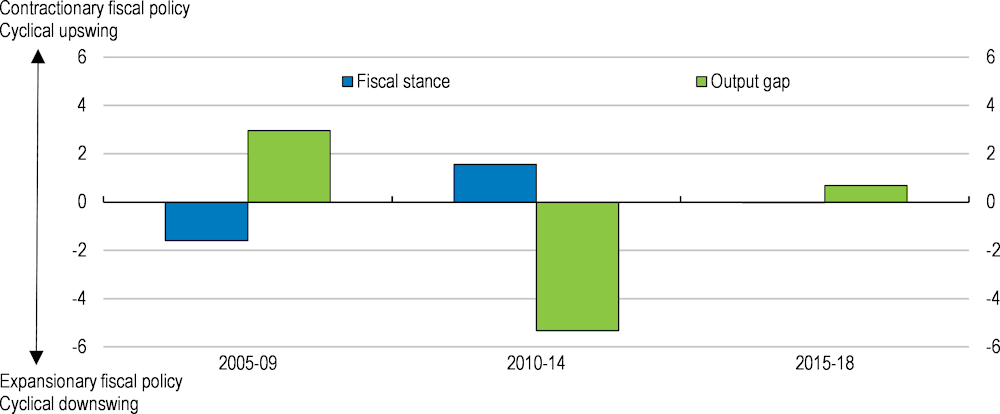

Ireland’s fiscal position continues to improve. For the first time in a decade, the budget balance returned to surplus in 2018. However, in the past few years the improvement has not reflected a structural tightening of fiscal policy. Instead, unexpected corporate tax receipts and interest savings have enabled the government accounts to balance. Against a backdrop of emerging capacity constraints, fiscal policy has been too loose, even if it has been less pro-cyclical than in 2005-09 or 2010-14 (Figure 1.13). The authorities should be vigilant to ensure that the historical pattern of fiscal policies that have amplified, rather than smoothed, the economic cycle is not repeated.

Figure 1.13. Fiscal policy has recently been less pro-cyclical but should have been tighter

Measured fiscal stance and output gap

Note: The figure presents the simple average of the fiscal stance (defined as the change in the underlying primary budget balance as a percentage of GDP) and the output gap over successive time periods. An increase in the fiscal stance denotes a contractionary fiscal stance. A positive output gap means actual GDP exceeds estimated potential output.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database, OECD calculations.

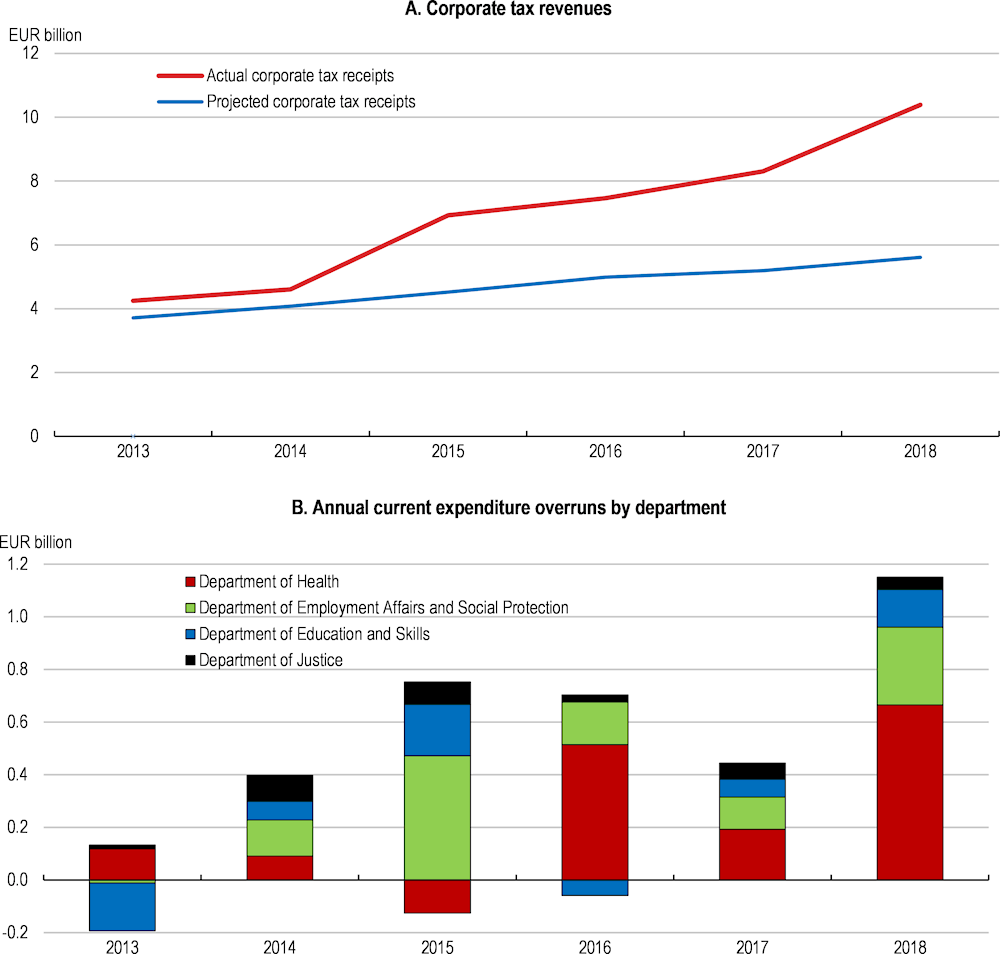

The recent rise in corporate tax receipts is likely to be unwound over the medium term and the authorities should plan accordingly. The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council has estimated that corporate tax receipts in 2018 were 30-60% (equivalent to 1½-3% of GNI*) higher than expected based on the economy’s underlying performance (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2019; Figure 1.14, Panel A). The concentration of corporate tax receipts continues to increase: the top 10 taxpaying companies accounted for 45% of overall corporate tax revenues in 2018, up from 39% in 2017 (Department of Finance, 2019c). The Department of Finance has taken the prudent approach of assuming that around one third of corporate tax receipts are non-recurring in their preparation of the subsequent year’s budget. However, unbudgeted expenditures over the past few years have meant that a substantial portion of these non-recurring receipts have been spent within the year (Figure 1.14, Panel B).

Figure 1.14. Windfall corporate tax revenues have been accompanied by expenditure overruns

Note: In Panel A, corporate tax receipts are projected using the best-performing modelling approach outlined in Casey and Hannon (2016). In Panel B, the four largest departments by current expenditure are shown. Expenditure overruns are calculated as the difference between the outturn and budgeted gross current expenditure for that year.

Source: Irish Fiscal Advisory Council.

The health sector has been a notable source of current expenditure overruns over the past few years, despite increased budget allocations. Another recurring issue has been the payment from the Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection of Christmas bonuses to social welfare recipients that are unbudgeted and adjusted from year to year based on “prevailing conditions”. In addition, some large public capital projects saw sizeable cost overruns. Ireland’s Comptroller and Auditor General has undertaken a review into significant time and cost overruns in recent capital projects in the higher education sector (Comptroller and Auditor General, 2019). Across both current and capital public expenditures, the historical pattern of cost overruns that are balanced through supplementary government financing creates little incentive for future public spending efficiency.

Further public spending overruns may crowd out other current or capital spending needs. As part of the National Development Plan 2018-2027, the government set aside €116 billion for public investment. This is a response to deep cuts to public capital investment through the crisis years and to expected future demographic pressures on infrastructure. Many such projects are much needed and cost overruns or poor project selection that crowd out public investments with high social returns must be avoided. Alternatively, additional unbudgeted public spending could slow the necessary continued reduction in government debt if other spending plans are maintained through increased borrowing.

In prioritising, costing and delivering public capital projects, the need for better availability of detailed data on public assets was underlined in the OECD Ireland Economic Survey 2018. More broadly, a recent OECD evaluation of the Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service identified poor data availability as an impediment to evidence-based policy making (OECD, 2020). A welcome development was the increased emphasis on improving data collection and identifying data gaps in the government’s 2019 Spending Review. New tools have also been developed such as the Investment Projects and Programmes Tracker that provides information on the progress of all major investments that make up Project Ireland 2040. However, continued efforts should be made to systematically collect information on the performance of existing public assets to better enable transparent, evidence-based prioritisation of future infrastructure projects. New Zealand provides an example of a country that identified data gaps as an impediment to robust infrastructure planning. Subsequently, a cross-sector infrastructure evidence base was published in 2014 and updated thereafter. The database provides performance indicators related to public assets as well as scenario analysis to identify future demand pressures on the infrastructure stock.

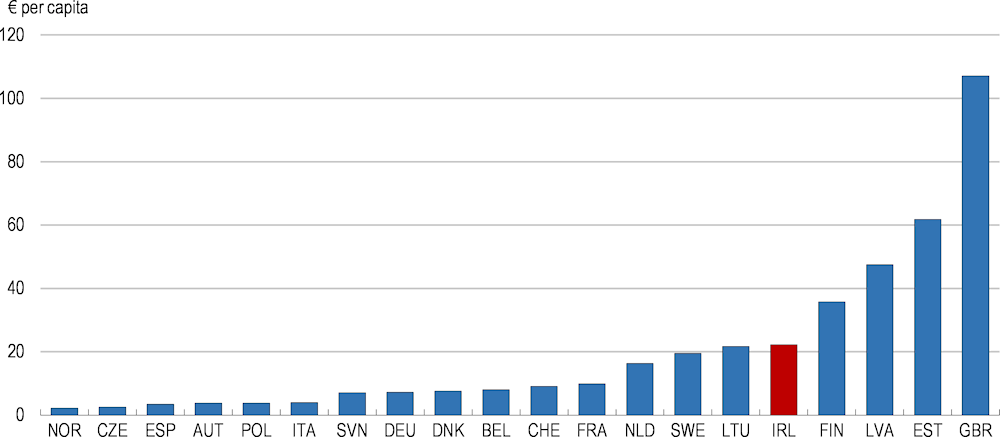

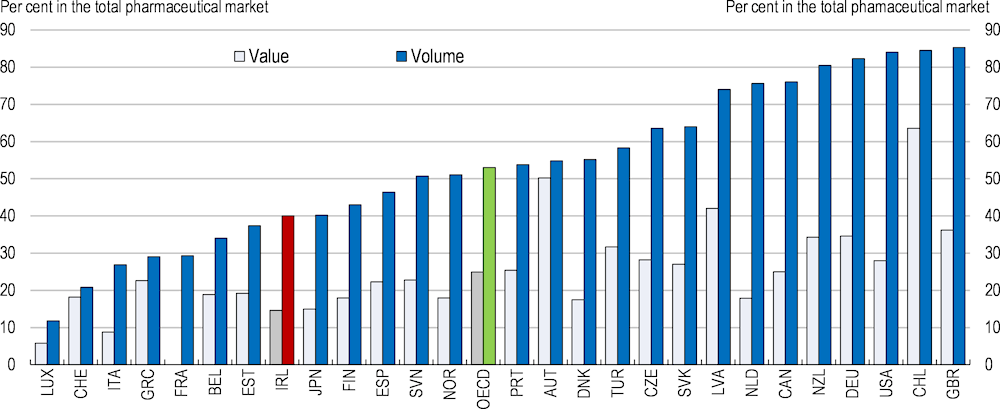

Government debt ratios continue to trend down, but gross general government debt remains high at above 100% of modified gross national income (GNI*). For Ireland, GNI* is a better indicator of the capacity of the government to repay its debt, insofar as it is less affected by one-off factors related to the activities of multinational enterprises. In per capita terms, general government debt is one of the highest in the OECD (Figure 1.15). Over half of long-term Irish government bonds are held by non-residents, that come with a higher risk of sudden stop in the event of a negative shock (Department of Finance, 2019d). Refinancing risk has been reduced through a significant increase in the average maturity of Irish government debt over the past decade. By 2018, average debt maturity was high compared with other European countries at above 10 years (Department of Finance, 2019d).

Figure 1.15. Government debt remains high on a per capita basis

The authorities have also now established the “Rainy Day Fund”, for use in the event of a severe adverse economic shock (Table 1.5). Initially, €500 million were to be transferred to the Fund from the Exchequer each year until 2023, and so far the Fund has accumulated €1.5 billion in liquid assets. Nevertheless, in preparing Budget 2020, the authorities chose not to transfer the earmarked €500 million to the Fund because of the potential challenges associated with a no-deal Brexit. Going forward, the transfer of the agreed amount to the Fund should be made each year, with the intended pool only reduced if a severe adverse economic shock does actually come to pass. Furthermore, the incoming government should commit to transferring further windfall corporate tax revenues to paying down general government debt and partly to the Fund to ensure future negative shocks can be offset through fiscal loosening.

Table 1.5. Past recommendations on public spending efficiency and taxation

|

Recommendations in the previous Survey |

Actions taken since March 2018 |

|---|---|

|

Set medium-term government debt targets as a share of measured underlying economic activity (i.e. GNI*). |

The government announced a target for public debt as a share of GNI* of 85% by 2025 and to 60% in the long-term. |

|

Pay down general government debt with windfall revenue gains and implement the proposed Rainy Day Fund. |

The National Surplus (Reserve Fund for Exceptional Contingencies) Bill 2018, which establishes the Rainy Day Fund, has now passed the Oireachtas. |

|

Identify productivity-enhancing fiscal initiatives that could also have a large short-term impact on growth in the face of a negative shock. |

In the event of a shock, the Rainy Day Fund could be used to maintain a planned level of capital spending, such as the projects currently planned in National Development Plan. |

|

Reduce the number of VAT rates. |

The number of VAT rates is unchanged. However, in Budget 2019, the government restored the VAT rate for most businesses in the hospitality sector to 13.5% from 9%. |

|

Reassess property values more regularly for the purposes of calculating local property tax. At the same time, protect those low-income workers adversely impacted. |

No specific action taken. |

|

Systematically collect information on the performance of existing public assets to better enable transparent, evidence-based, prioritisation of future infrastructure projects. |

The authorities improved data collection and identified data gaps as part of the 2019 Spending Review. |

Looking forward, the fiscal framework needs further reform, as some of the fiscal rules outlined in the EU Stability and Growth Pact are not entirely suitable in the Irish context. Ireland’s upwardly distorted GDP, along with inflated corporate tax receipts, flatter the Irish fiscal position when judged against fiscal rules that are based on GDP or on the closely-related measure of potential output growth that is harmonised across EU countries. As part of Budget 2020, the Department of Finance noted that key components of the EU fiscal rules such as the binding 3% of GDP threshold for the headline fiscal deficit, the 60% general government debt-to-GDP threshold, the “medium-term objective” and the “expenditure benchmark” (both of which depend on estimates of potential output growth) are misleading in the case of Ireland (Department of Finance, 2019e). To support the calibration of appropriate fiscal policy, Ireland should self-impose a more stringent set of fiscal targets. These should be based on GNI* (instead of GDP) and the measure of potential output growth that has been developed by Ireland’s Department of Finance and endorsed by the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council. The authorities recently made progress in this regard, announcing a target for public debt as a share of GNI* of 60% in the long term and around 85% by 2025.

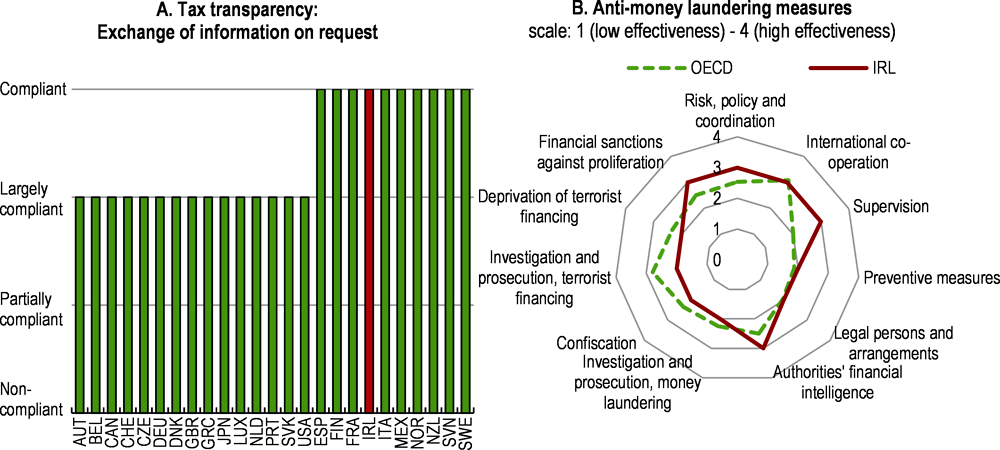

Ireland continues to be an active participant in efforts to advance international tax policy coordination. Numerous actions have been taken to implement recommendations from the OECD BEPS Action Plan. These include the introduction of country-by-country reporting for large multinational enterprises and the first OECD-compliant patent box, as well as early signature and ratification of the BEPS Multilateral Instrument.

The OECD has recently released two consultation documents on potential changes to the International Tax System. These proposals fall under two Pillars. Under Pillar 1, the Secretariat has proposed a Unified Approach that would establish a new nexus and allocate increased taxing rights to market/user jurisdictions. Under the proposal, countries would be allocated some taxing rights that would not be dependent on physical presence but would be largely based on sales (OECD, 2019a). Under Pillar 2, the consultation document outlines a proposal that would aim to ensure that all internationally operating businesses pay a minimum level of tax on their foreign income. This could impact the attractiveness of Ireland as a location for foreign direct investment. While many details of the proposals are still under discussion by the Inclusive Framework on BEPS, such an agreement would go some way to addressing the tax policy challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy.

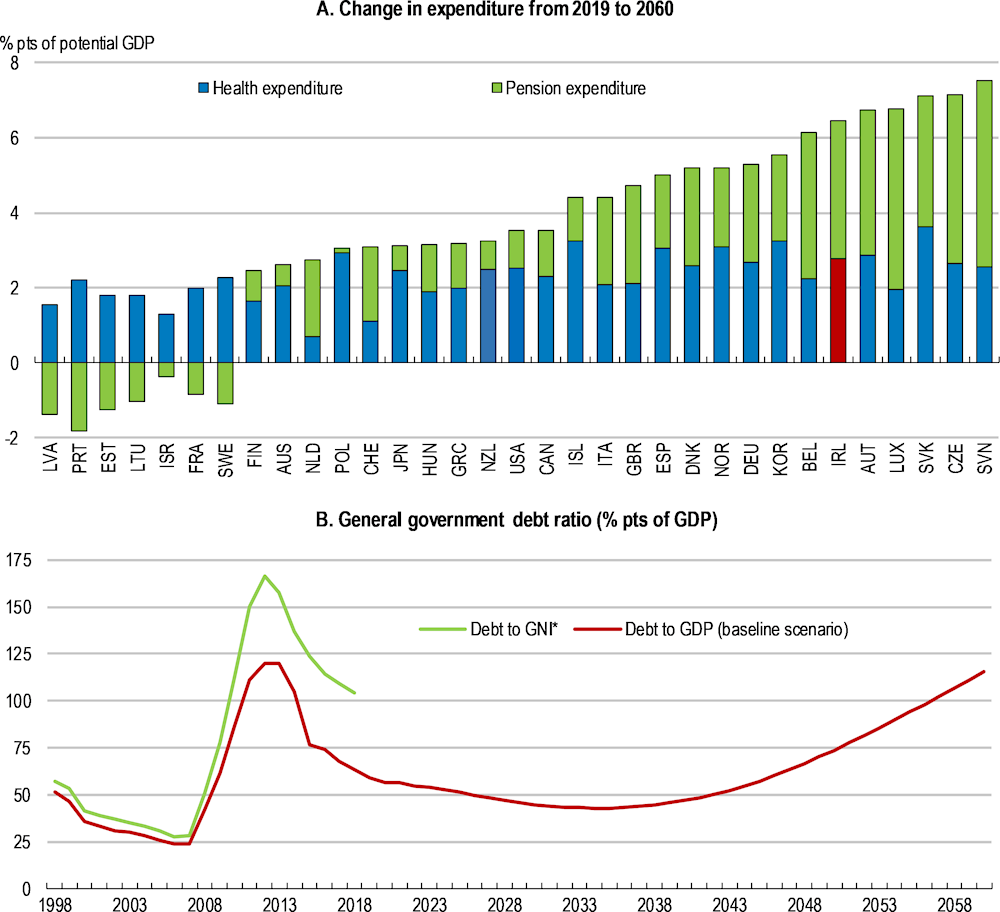

Substantial fiscal pressures loom on the horizon

Ageing-related costs will exert substantial pressure on public finances over the coming years. Current trends suggest the increase in public expenditure on health and pensions will be one of the largest in the OECD, expanding by over 6% of GDP by 2060 (Figure 1.16, Panel A). Government debt is projected to rise back above 115% of GDP absent offsetting policy measures (Figure 1.16, Panel B). Ageing may also put downward pressure on revenues, as it will lower the proportion of people active in the formal labour market in a tax system that relies heavily on labour taxation. Growth-enhancing structural reforms may provide some offset, but this will not be enough to put government debt on a sustainable trajectory.

Figure 1.16. Ageing costs will create substantial fiscal challenges

Future corporate tax revenues are also likely to slow. The authorities acknowledge that the windfall corporate tax revenues of recent years may not be sustained and new international tax rules around the digital economy could reduce corporate tax revenues further (Government of Ireland, 2019a). The impact of international tax changes on Irish tax receipts depends heavily on the exact rules adopted. Notwithstanding considerable uncertainty, the authorities recently estimated that corporate tax receipts could be €500 million lower per year between 2022 and 2025 as a result of the implementation of BEPS (Government of Ireland, 2020). This does not take into account potential secondary effects, such as the location decisions of multinational firms.

The combination of still high public debt, elevated economic uncertainty and substantial future cost and revenue pressures require deep reforms to fiscal policy. There is scope to improve expenditure efficiency, but new streams of tax receipts will need to be found if government finances are to be made sustainable and large cuts to public services avoided. Ireland proved adept at implementing essential economic reforms that were well communicated to the population through the recent economic crisis, suggesting that such changes to fiscal policy are achievable.

Raising public spending efficiency

An ageing population will mean a greater share of government spending allocated to health, social care and pensions over the coming years. Combined with the fact that health and social protection have been experiencing the largest recent cost overruns (Figure 1.14, Panel B), improving public expenditure efficiency in these areas should be prioritised.

In the health sector, most of the recent increase in public funding has been directed toward hospitals. However, it has led to no significant increase in measured outputs (Lawless, 2018), insofar as the overall number of patients on hospital waiting lists has not declined (Health Service Executive, 2019). Unbudgeted health spending has been attributed to both weak spending controls and weak budget planning (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2018). Several recent initiatives have sought to improve spending efficiency in hospitals. Activity-based funding (whereby budgets are allocated to each hospital based on the number and complexity of patients) has replaced block funding for inpatient and day-case procedures. The Health Service Executive also introduced an Accountability Framework for the sector, with a review undertaken in 2015. However, several of the review’s recommendations, including the requirement for hospitals to produce their own productivity plans, have not been implemented.

The key instrument available to the Health Service Executive for budget planning is the National Service Plan. There are legislative requirements associated with these plans to have them set out the health services to be provided in the forthcoming year given the allocated budget envelope. Nevertheless, several of them have not been fulfilled in recent years (Connors, 2018). Going forward, the plan should: i) be drafted in line with the agreed budget published in mid-December every year, ii) provide estimates of the number of employees of the Health Service Executive during the period and the services to which they relate, iii) indicate the type and volume of health and personal social services to be provided during the plan period.

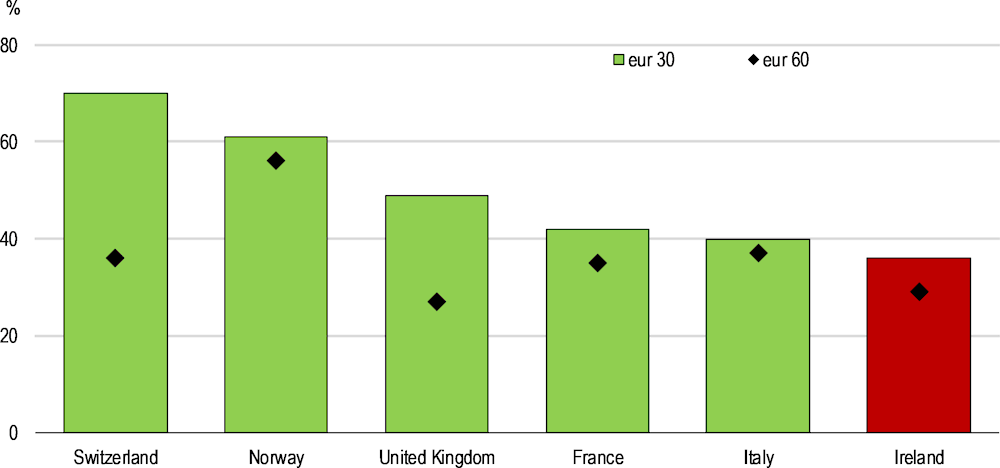

In the area of social protection, pension spending is anticipated to increase by around 0.7% of GDP over the next decade, accounting for half the increase in demographic-driven public costs. Ireland’s state pension operates on a pay-as-you-go basis, meaning that pension disbursements are funded by the taxes and social contributions of current workers. An expected rise in the old-age dependency ratio, from 20.5% in 2016 (i.e. 4.9 workers for every old age dependent) to 44% in 2051 (Parliamentary Budget Office, 2019), will then threaten the sustainability of the system. To help tackle this challenge, the state pension age was increased to 66 in 2014 and will rise to 67 in 2021 and 68 in 2027. Thereafter, it ought to be linked to changes in life expectancy. There is also scope for private pensions to play a greater role in the system, as private pension coverage is currently low in Ireland (OECD, 2019b). The authorities outlined a Roadmap for Pension Reform in 2018 which included an auto-enrolment system, whereby private pension contributions from employers and employees (subject to an earnings ceiling) will be partially matched by the government. This measure designed to strengthen private pension savings is scheduled to be introduced in 2022.

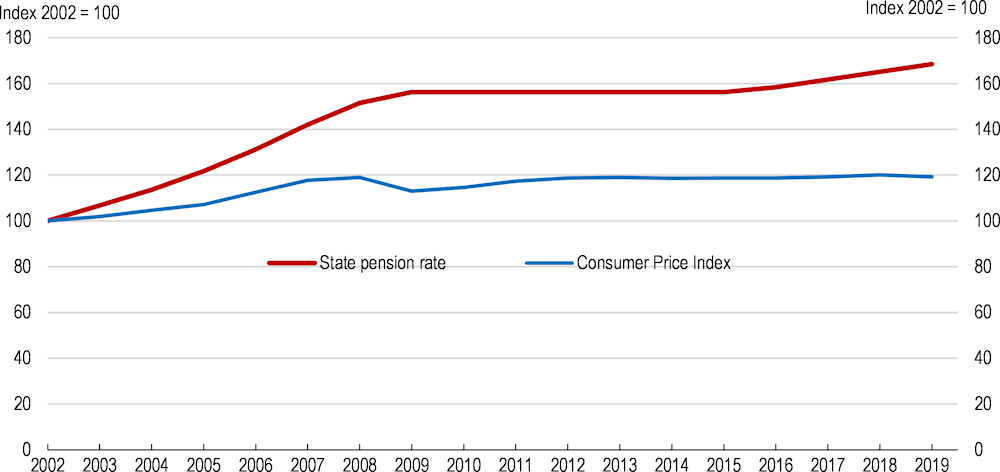

At present, increases in the State pension are determined in a discretionary manner as part of the annual budget process. This contrasts with many other OECD countries where the benefit rate is indexed to domestic wage or price developments. Since 2002, the state pension benefit has risen by 65%, following a heavily pro-cyclical pattern, compared to a 20% rise in Irish consumer prices (Figure 1.17). Compared with other OECD countries, the value of the basic pension in Ireland appears adequate at present (OECD, 2017b). Indexation of future benefit increases to consumer price inflation would be a more transparent system that, based on recent historical experience, would produce budgetary savings. In a similar vein, Christmas bonuses to welfare recipients should be delinked from revenue outturns in order to improve fiscal sustainability and to avoid fiscal policy exacerbating fluctuations in economic conditions. These bonuses should also be systematically included in government budget plans.

Figure 1.17. Basic pension benefits have outpaced consumer prices

Raising revenues through growth-friendly tax sources

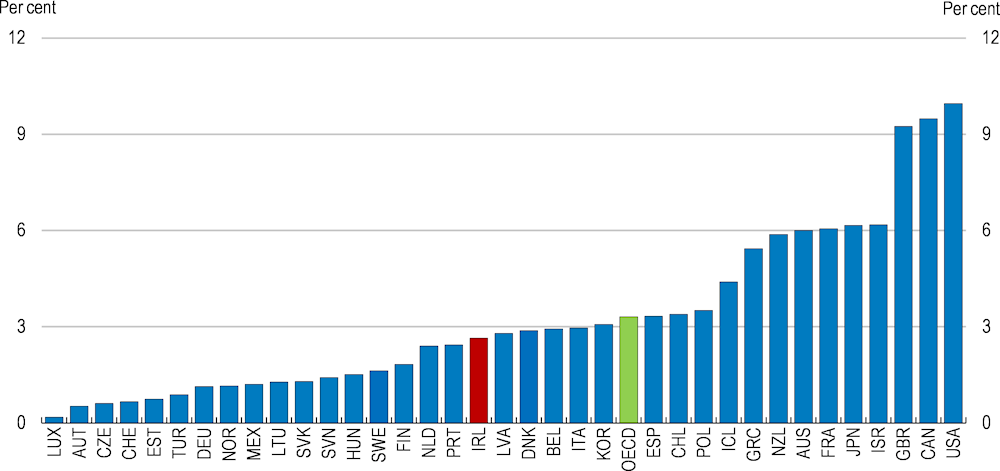

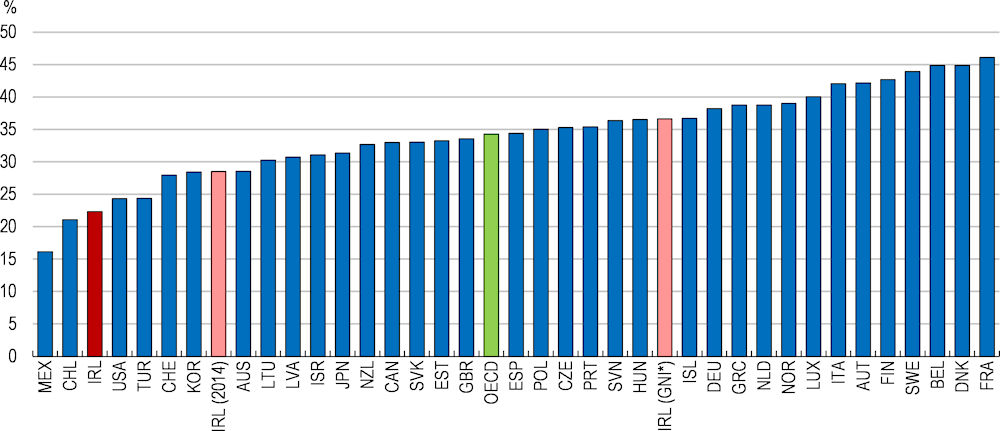

New sources of revenue are likely to be needed in addition to structural reforms and improvements in public spending efficiency to achieve a sustainable path of public debt. At present, the tax burden in Ireland is low compared with other OECD countries in Europe (Figure 1.18). In the first instance, the tax base of those forms of taxation proven to be less distortionary for economic activity or that dissuade undesirable activities should be broadened. Some changes in tax policy may have adverse distributional consequences that require offsetting policy adjustments to ensure that social cohesion is maintained.

Figure 1.18. The tax burden is low compared with most other European countries

Tax revenue as a percentage of GDP, 2018

Note: Data for Australia and Japan are for 2017. Given the distortions to Irish GDP, alternative measures for Ireland are also presented. Both the ratio of tax revenue to GDP in 2014 (before the significant distortions to Irish GDP occurred) and tax revenue as a share of modified gross national income (GNI*) are presented in pink. It should be noted that the latter measure is not strictly comparable to the measures for other countries that take GDP as the denominator.

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics database.

A recent laudable tax policy change was the restoration of the VAT rate for most businesses in the hospitality sector to 13.5% (from 9%), announced in Budget 2019 (Table 1.4). Consumption taxes are less distortionary to the economy than some other taxes such as those on income (Johansson et al., 2008) and the 2011 reduction of the Value Added Tax (VAT) rate for the hospitality sector to 9% had little economic merit. The experience of other European countries such as France suggest that the stimulatory impact of such measures on employment are modest (Benzarti and Carloni, 2017). Moreover, as many of the items in the sector are disproportionately consumed by those with relatively high incomes, the reinstatement of the 13.5% VAT rate for hospitality should not harm inclusiveness.

As highlighted in the OECD Ireland Economic Survey 2018, there is scope to further broaden the tax base and improve the efficiency of the tax system by moving from five different VAT rates to three. One aspect of this reform would be moving all items that are currently taxed at the zero rate to a VAT rate of 5%. As the zero rate is currently applied to many necessities (i.e. most food, books, children’s clothes and shoes, oral medicines), such a move would likely have adverse consequences for low-income households. With this in mind, part of the revenues raised from the reform should be used for targeted transfers to those on low incomes. Overall, a reform package that involved streamlining the VAT rates at the same time as increasing transfers to low-income households could improve the efficiency of the tax and transfer system and raise around 0.5% of GDP in government revenue (Table 1.6).

Ireland also relies relatively little on some other efficient tax sources, such as recurrent taxes on immovable property (Figure 1.19). Such taxes are less distortionary than taxes on income because they have less of an impact on decisions to supply labour, invest in human capital and other assets, produce and innovate (Johansson et al., 2008). As emphasised in the 2018 OECD Ireland Economic Survey, there is scope to increase revenues from recurrent property taxation by more regularly updating market values. However, since then, the authorities have delayed the revaluation of the properties that are the basis of the local property tax until 2020. This follows an earlier delay of the revaluation from 2016 to 2019. For most properties, taxes are being paid on their 2013 value or not at all (if built since 2013). Given steady increases in house prices, households in some locations would face a steep hike in property tax liabilities if the base were updated to the 2019 market value. To ensure a measure of stability in local property tax bills and protect the revenue source, an interdepartmental group has recently proposed several alternative methods for the revaluation.

Figure 1.19. Recurrent taxes on immovable property are underutilised

Recurrent taxes on immovable property, % of total taxation

Going forward, more regular revaluations of the local property tax base are essential. These should continue to be calculated on lagged valuations of dwelling prices to minimise the pro-cyclicality of the revenue source. More regular revaluations will help achieve the objective of minimising large and unexpected adjustments in the property tax liabilities of households. The fact that a higher tax rate is currently applied to properties valued at above €1 million and that the steepest rise in property values since 2013 has been in Dublin (a comparatively high-income area) suggests that a revaluation is unlikely to worsen aggregate income inequality. Nevertheless, harmful distributional consequences of changes in property tax liabilities should continue to be monitored. As further discussed in Chapter 2, the authorities may also consider replacing some of the current array of property taxes, such as stamp duty, with a recurrent land tax levied on site value. This could be done in a revenue-neutral way, but would encourage more efficient land use at the same time as having much less distortionary impact on the investment decisions of households and businesses (Blöchliger, 2015).

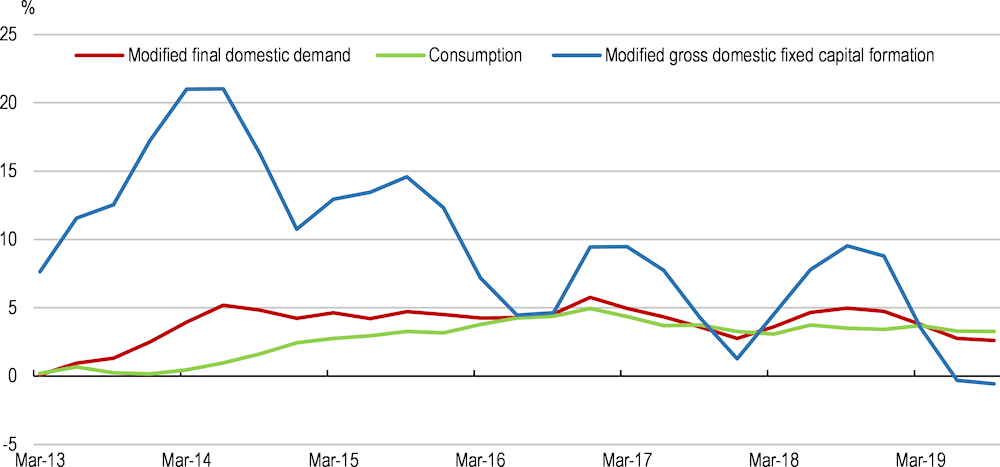

Environmentally-related taxes also need to be increased in order to reduce the damage that households and businesses do to the natural environment. Ireland will not achieve its targeted reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 or 2030, based on current policy settings. Environment-related taxation remains low compared with the average OECD country and less than half of Ireland’s energy-related CO2 emissions are priced above €30 per tonne, a low-end estimate of climate-related cost (Figure 1.20). The Irish government has expressed a deep commitment to decarbonisation and a Climate Action Plan has been published. Therein, it proposed that the carbon tax be raised from €20 per tonne of CO2 to €80 by 2030. The first step in this process was taken in Budget 2020, with the carbon tax raised to €26 per tonne of CO2 on petrol and diesel (its implementation for other fuels is being delayed until May 2020, after the winter heating season). Sustained action needs to be taken to achieve this policy adjustment, by increasing the carbon tax each year according to a schedule that is well communicated to households and businesses.

Distributional and poverty effects should be considered in designing a policy package that allows for steady upward adjustments in the carbon tax. Recent simulation results suggest that an increase in the carbon tax to €30 per tonne of CO2 would induce a 4% decline in emissions (Tovar Reaños and Lynch, 2019). However, the policy change is found to be regressive, as energy expenditure makes up a relatively large share of the expenditure bundle of poorer households. According to the simulations, such distributional consequences could be entirely unwound by recycling some of the increase in carbon tax revenues in the form of a targeted transfer to poorer households through the social welfare system. Nevertheless, such transfers should be thoughtfully designed to avoid disincentivising work. In increasing the carbon tax in Budget 2020, three different uses for the revenues were identified by the Minister of Public Expenditure and Reform: i) support for low-income families through an increase in the winter fuel allowance and energy efficiency upgrades for households at risk of energy poverty; ii) energy efficiency upgrades and new transition programmes for the Midlands region, which has seen job losses in the peat harvesting industry owing partly to government commitments to scale back peat burning in power stations; iii) measures to promote behavioural change such as investment in cycling projects and electric vehicle infrastructure.

Figure 1.20. Environmental taxes are low

% of total CO2 emissions from energy use, EUR per tCO2, 2015

Recent experience from other OECD countries may be useful as the authorities consider how to offset any regressive effects of future increases in the carbon tax. Simulations for Germany suggest that using two thirds of a carbon tax on transport and heating fuels for per capita lump-sum transfers would avoid making large groups of households worse off and would make most families as well as low-income households with relatively low per capita energy consumption better off (Bach et al., 2019). It may also be prudent to distribute such a payment ahead of the tax taking effect in order to help garner public support. An example of successful implementation of a carbon tax is British Columbia in Canada, which redistributed the revenues from the tax to households through tax reform. At the federal level, Canada has also used per capita lump sum transfers as well as transfers that vary depending on the remoteness of a household location. Location-contingent transfers could help reduce financial pressure on car-dependent households. Such transfers could be temporary and need not influence incentives if related to location at the time of introduction of the tax.

At the same time, other aspects of tax policy can be reformed to better deter environmentally damaging activities. The revenues derived from such adjustments can be used to undertake new green projects, to reduce other forms of taxation or to lower the government’s outstanding debt burden. Synthetic fertilisers are currently at the zero VAT rate, despite the negative environmental consequences of their use including soil and water pollution. With the broader reform of the VAT system recommended above, such fertilisers should eventually be moved to, at least, the standard VAT rate.

Box 1.2. Quantifying the impact of selected policy recommendations

Table 1.6 presents estimates of the fiscal effects of some of the recommended reforms. The quantification is merely indicative and does not allow for behavioural responses or the impact of the tax and spending measures on GDP growth. Table 1.7 quantifies the impact on growth of some of the reforms recommended in this Survey (quantification is not feasible for all of them).

Table 1.6. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

Fiscal savings (+) and costs (-)

|

% of GDP |

% of GNI* |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Expenditure items |

||

|

Improve the spending efficiency of the health sector |

0.8 |

1.3 |

|

Additional health spending |

-0.9 |

-1.4 |

|

Increased active labour market programme spending |

-0.6 |

-1.1 |

|

Total - expenditure |

-0.7 |

-1.2 |

|

Revenue items |

||

|

Broaden and streamline the VAT base |

0.5 |

0.7 |

|

Increase recurrent property taxation |

0.9 |

1.5 |

|

Total – tax reforms |

1.4 |

2.2 |

|

Total net fiscal savings (+) or costs (-) |

0.7 |

1.0 |

Note: The improvement in health spending efficiency assumes that health spending per capita on government schemes converges to the OECD average using 2018 as reference year. The additional health spending is based on the estimated recurrent cost of implementing the Sláintecare plan (Committee on the Future of Healthcare, 2017). The increase in active labour market programme spending assumes that both per participant spending and participation relative to the size of the labour force increases to the average of the top half of OECD countries. The scenario assumes that some offsetting savings are generated by streamlining passive labour market programmes at the same time. The illustrative VAT reform involves moving all VAT items to either a 5%, 15% or 25% rate, with the revenue yield from moving zero rate items to a 5% rate entirely spent on direct transfers to low-income households. The revenue estimates for the VAT reform are taken from Department of Finance (2019f). The additional property tax yield assumes that Ireland increases the share of recurrent property taxation in total taxation to the average of the top quartile of the distribution of OECD countries.

Table 1.7. Illustrative impact on GDP per capita from structural reforms

Difference in GDP per capita level from the baseline 10 years after the reforms, %

|

Reform |

Description |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Further reduce product market regulation |

Reforms that include reducing barriers to entry in legal services and further simplify licensing requirements and administrative procedures are undertaken over five years. The reforms are assumed to move Ireland’s product market regulation settings to the average of the quartile of countries with the most competition-friendly competition policy settings. |

1.4 |

|

New training programmes |

Educational attainment of the population gradually increases by 5% over 10 years. This would take Ireland from being ranked 22nd in the OECD (based on the measure of human capital from the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital) to number 18th at 2030. |

1.3 |

|

Ensure effective enforcement of the new criminal law |

Improve Ireland’s rule of law over five years so it corresponds with the average of the top quartile of OECD countries on the World Bank Rule of Law Index. |

1.6 |

|

Total |

4.3 |

Note: The model used for these simulations is a supply-side model focusing on the long-run. As such, it is not well suited to incorporating the implied increase in net fiscal savings highlighted in Box 1.6, partly because these are funded by recommended tax base broadening measures that are more likely to impact demand in the short to medium-term.

Source: Simulations based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

There is also a need for new policy settings that reduce road congestion. Dublin was the third most congested OECD city in 2018, behind Istanbul and Mexico City, according to the Tom Tom Traffic Index. In this context, the government should consider introducing congestion charging to incentivise avoiding trips at busy times and greater use of public transport. Nevertheless, before implementing such a policy, it is important to ensure adequate availability of alternative modes of transport to accommodate those switching away from motor vehicle travel. As part of the National Development Plan 2018-2027, the authorities prioritised new train infrastructure (e.g. the Metro link and DART expansion in Dublin), an overhaul of the bus system in Ireland’s cities and the expansion of cycling and walking infrastructure. At the same time, new modes of shared transport should be actively promoted (International Transport Forum, 2018; Chapter 2) and demand-management tools such as greater restrictions on parking should continue to be pursued. Along with congestion charging, distance-based charges for motor vehicles may need to be considered in the future to offset a depletion in government revenues as the car fleet moves further towards electric vehicles that pay no fuel excise tax.

Medium-term policy challenges

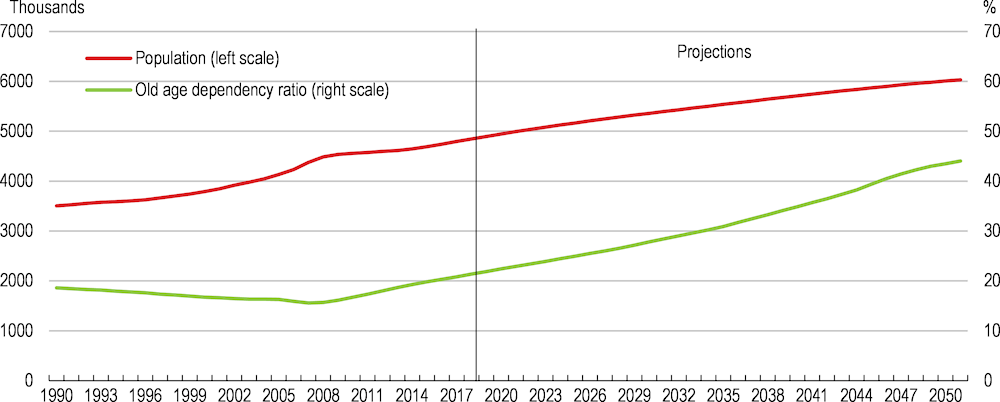

Looking ahead, there is a risk that capacity constraints are exacerbated by demographic pressures (Figure 1.21). The population is expected to grow by one quarter and the old age dependency ratio will more than double by 2050.

Figure 1.21. The population will grow and age markedly

Note: Projections are based on a central scenario assumption for migration and fertility.

Source: CSO.

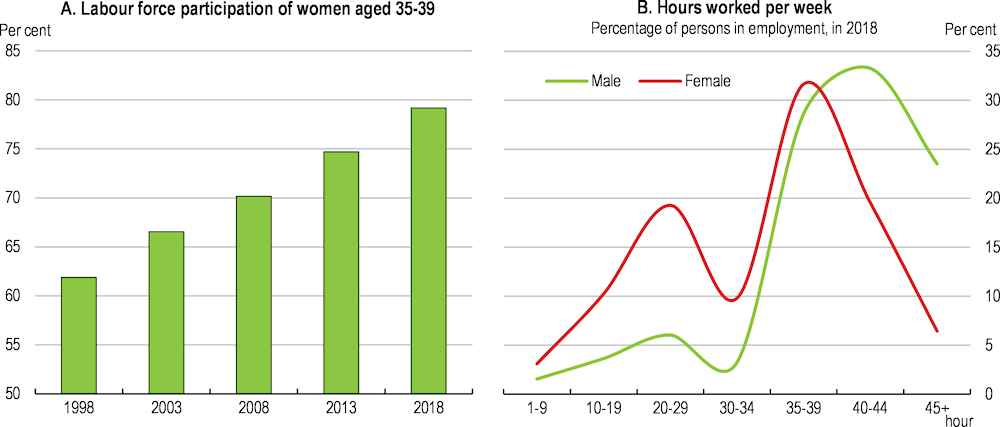

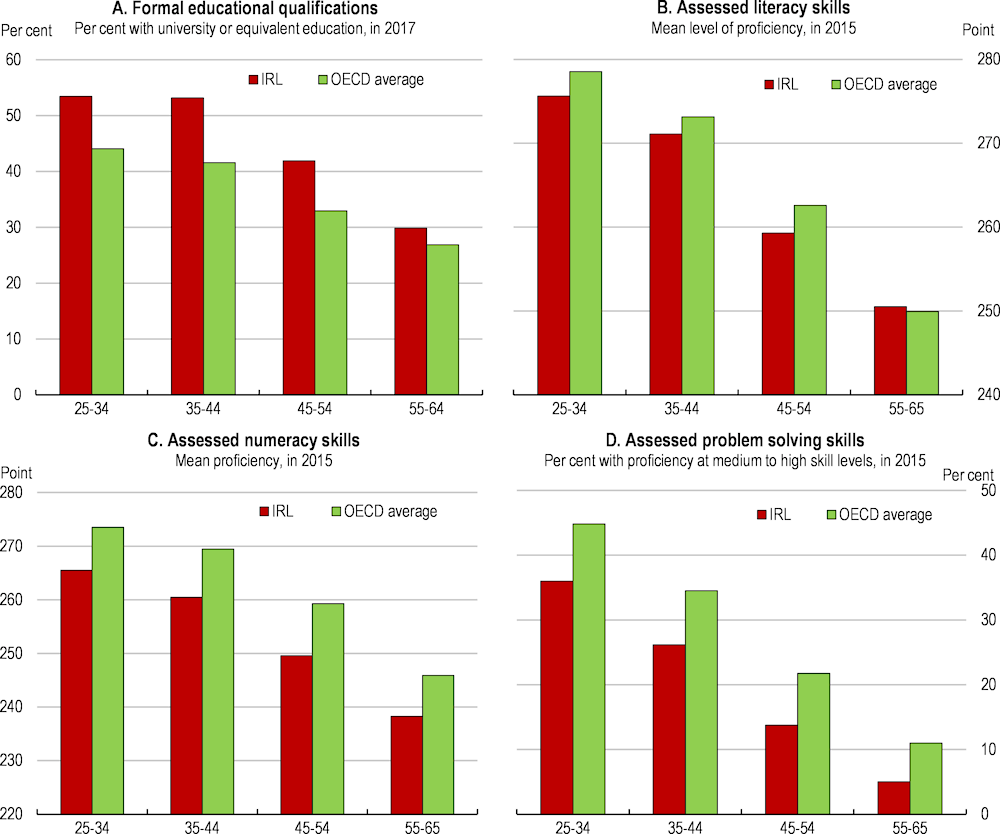

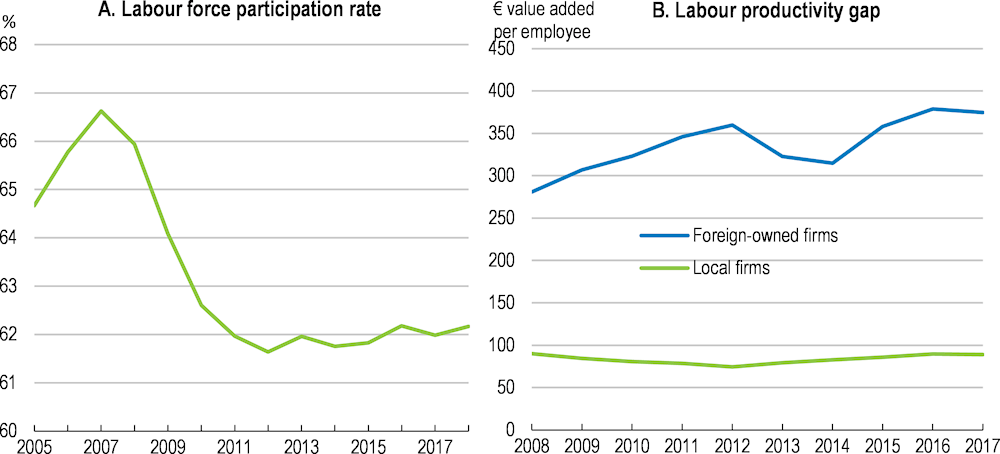

To meet this challenge, the supply side of the economy will need to continue to evolve. The labour force participation rate has fallen over the past decade as the population has begun to age and more young people have chosen to stay in education (Figure 1.22, Panel A). Ensuring that those that who wish to work are supported in doing so will be important over the coming years to promote both the inclusiveness and the competitiveness of the economy. This will require maintaining a health system that supports employment later in life.

Figure 1.22. Labour participation and productivity of local firms remain low

Note: In Panel A, the labour force participation rate of the population is calculated as a four-quarter average and is based on the population aged over 15. In Panel B, data are for those firms in contact with the enterprise agencies of the Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation.

Source: CSO, Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation.

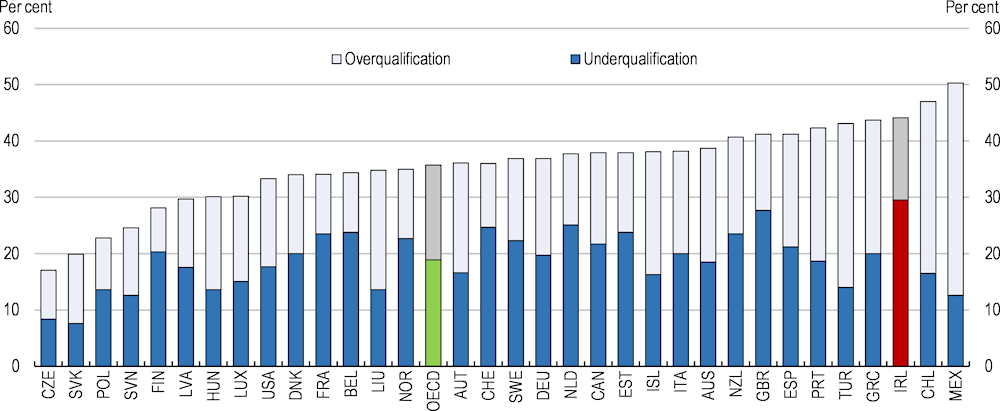

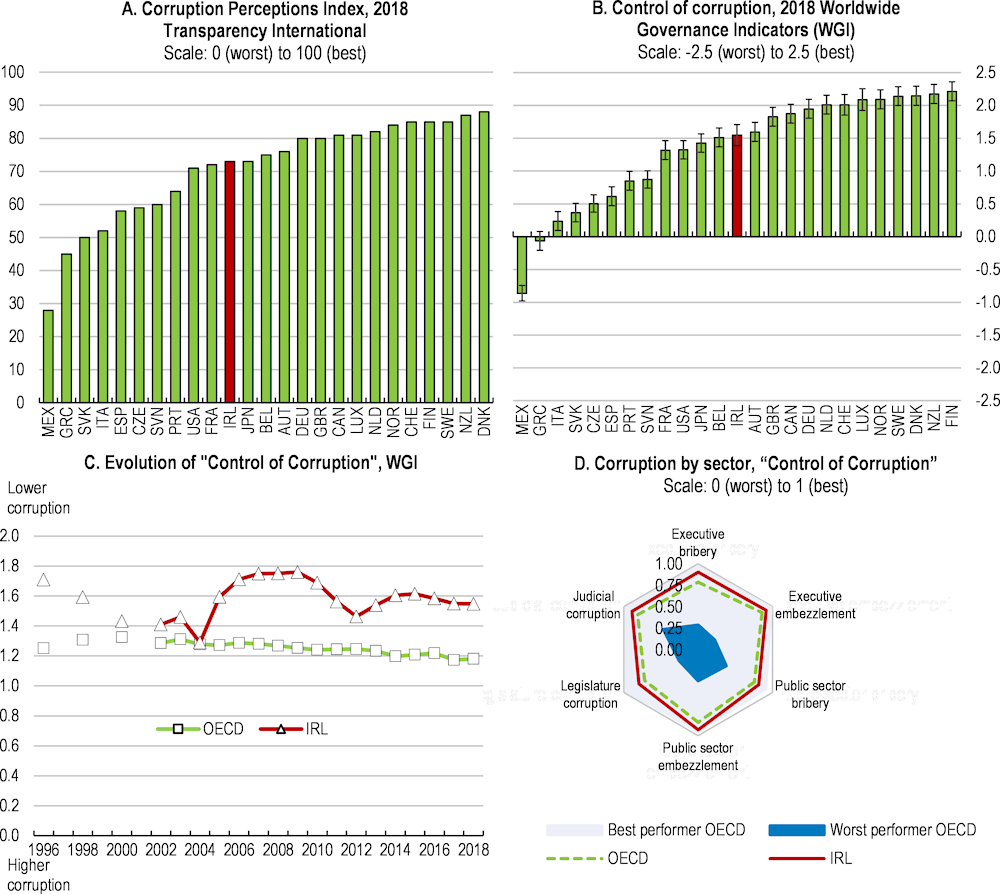

Improving the efficiency of production processes will also be key. The 2018 OECD Economic Survey of Ireland focused on supply-side issues stemming from the weak productivity growth of locally-owned enterprises (Figure 1.22, Panel B). The large productivity gap between foreign-owned and locally-owned enterprises has translated into wage differentials between the two types of firms, contributing to Ireland’s high level of market income inequality (Figure 1.1, further above). As such, boosting productivity in local businesses should also benefit inclusiveness. One area where government can support productivity is by ensuring institutional arrangements prevent and sanction economic crimes. Concurrently, an expanding economy and population will need to use natural resources more efficiently. This is particularly the case given the increasing risk of severe and irreversible impacts stemming from climate change.

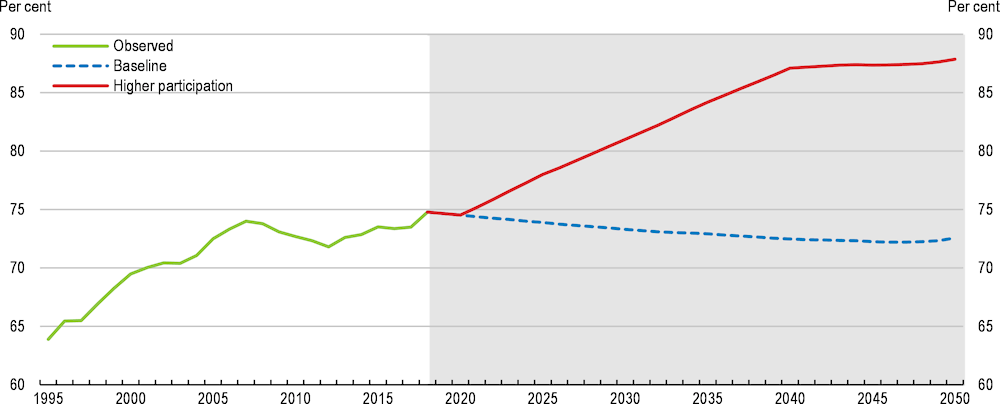

Better utilisation of the labour force to help alleviate capacity constraints

Future Jobs Ireland, the medium-term economic development strategy, sets a target of raising the labour force participation rates of those aged between 25 and 69 from 74.8% in 2018 to 78% by 2025 (Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation, 2019). To achieve this, a dramatic increase in the labour force participation of some cohorts will be required, notably women and older workers. For example, the illustrative scenario outlined in Figure 1.23 (“higher participation”) would put the labour force participation rate on a path to allow the 2025 target to be achieved. Under this illustrative path, the gender participation gap for those aged between 25 and 64 (currently at 13.6%) would need to be closed by 2040 and the participation rate of those aged 65-69 to rise from the currently observed 23.3% to 55.3% by 2050.

Figure 1.23. Labour force growth will significantly slow down without higher participation

Labour force participation rate of those aged between 25 and 69

Note: “Baseline” assumes that the labour force participation rates for both genders and all five-year age groups remain at their levels of 2018. “Higher participation” assumes the participation rates for each gender and age group as follows: the rates of men in each five-year age group between 25-29 and 45-49 increase to the levels prior to the crisis (averages over 2000-07) by 2025; the rates for men in five-year age groups of 50-54, 55-59 and 60-64 converge to that of the 45-49 age group by 2030, 2035 and 2040, respectively; the participation rates for men and women in age groups of 65-69 and 70-74 converge to the averages of the top third of OECD countries by 2035 and continue to rise at the same pace through 2050; the participation rates for women in each age group between 25-29 and 60-64 converge to those for men by 2040

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics; Central Statistics Office, Population & Labour Force Projections; OECD calculations.

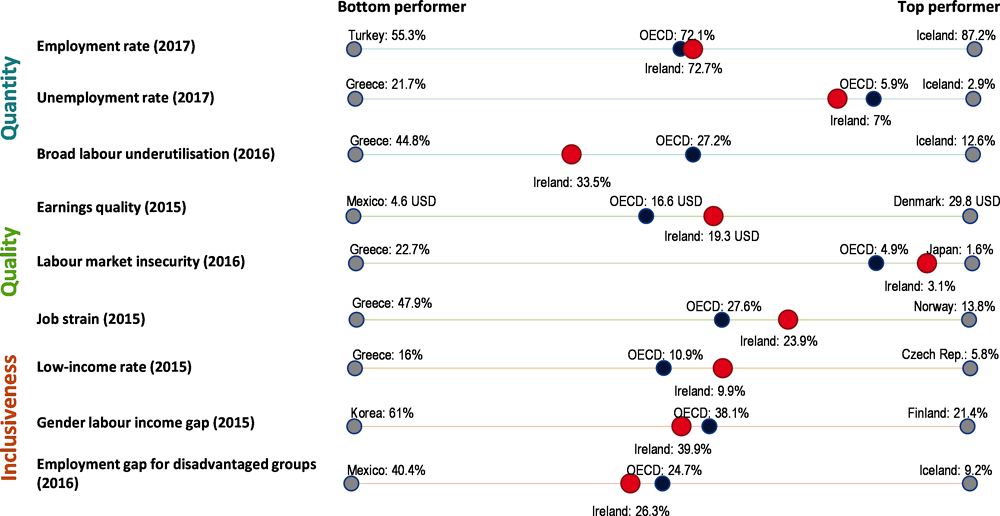

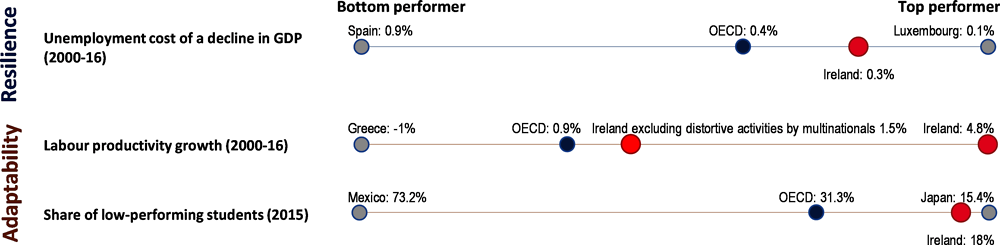

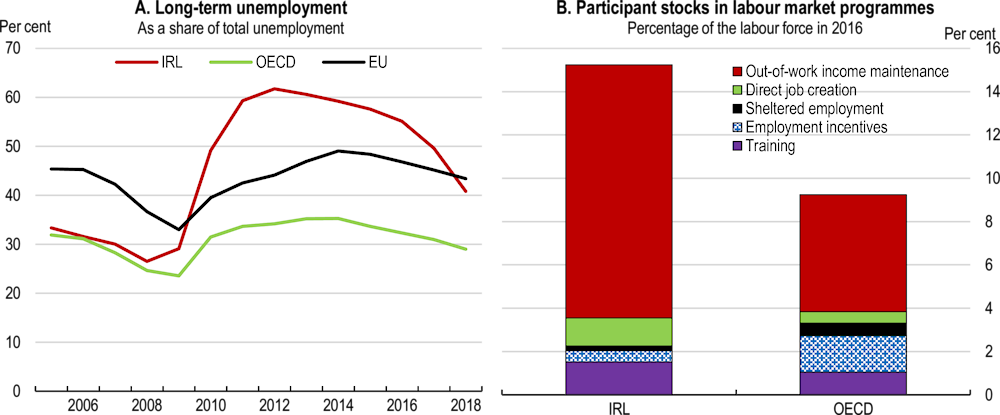

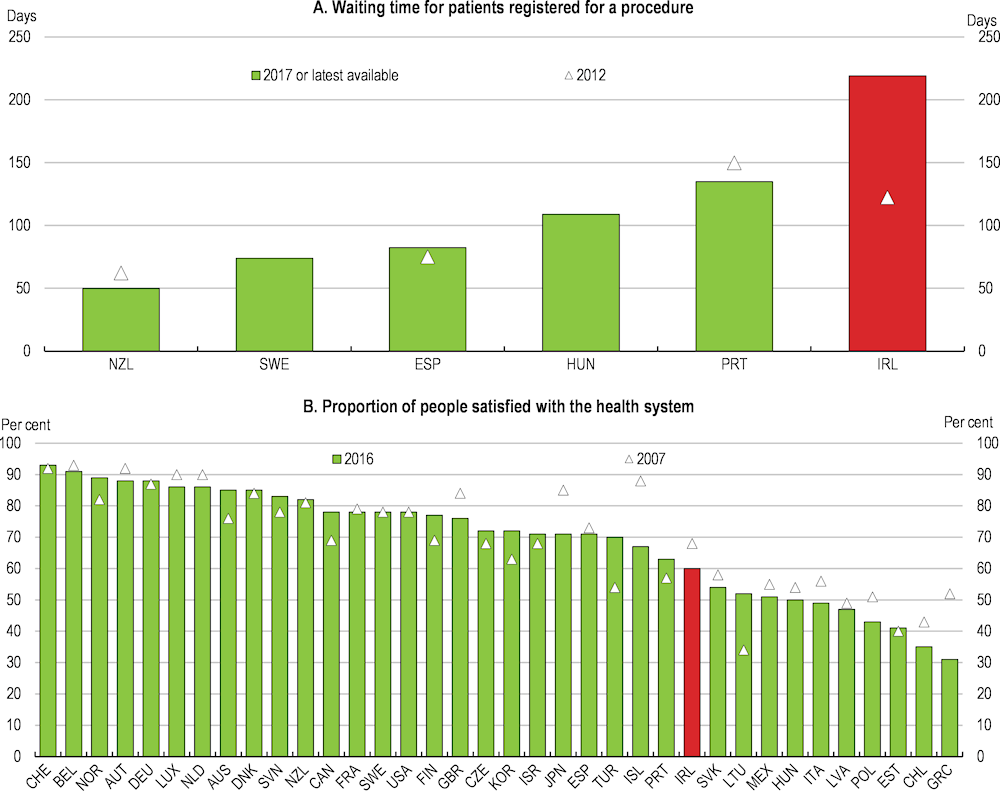

Reducing labour underutilisation and the pool of long-term unemployed