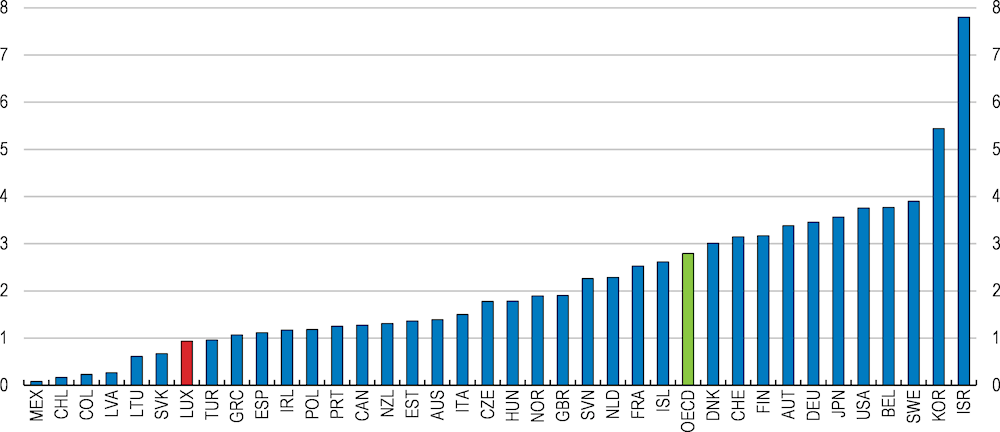

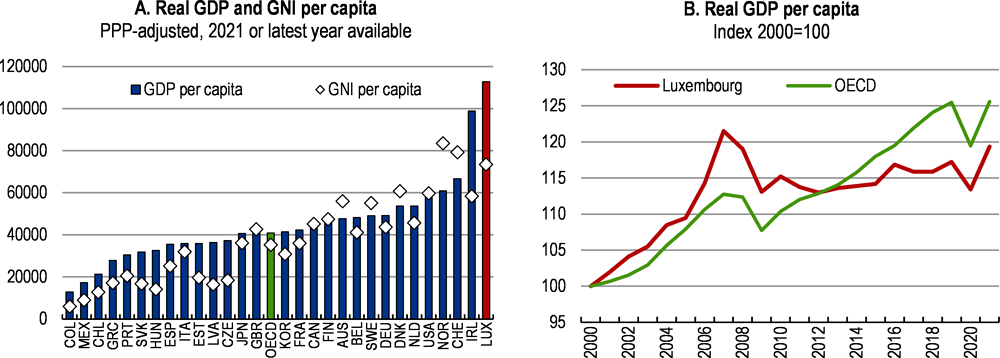

Luxembourg has the highest per capita income levels in the OECD when measured by GDP, and the third-highest after Switzerland and Norway, when measured by gross national income (Figure 1.1, panel A). Growth is jobs-rich, with the unemployment rate one of the lowest in the OECD. However, growth in GDP per capita has been below the OECD average since the global financial crisis (2008-09), following high growth in the early 2000s (Figure 1.1, panel B). The economy proved resilient in face of the shock from the 2020-21 COVID-19 pandemic, and the recovery was broad-based. The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and high inflation in 2022 have affected consumer and business confidence, stifling the economic recovery and making the outlook more uncertain.

OECD Economic Surveys: Luxembourg 2022

1. Key Policy Insights

Figure 1.1. Incomes remain high despite growth slowing down since the global financial crisis

Note: Gross national income captures the activity of residents, whereas GDP includes consumption by the large share of cross-border workers that enter the country every day.

Source: OECD National Accounts (database).

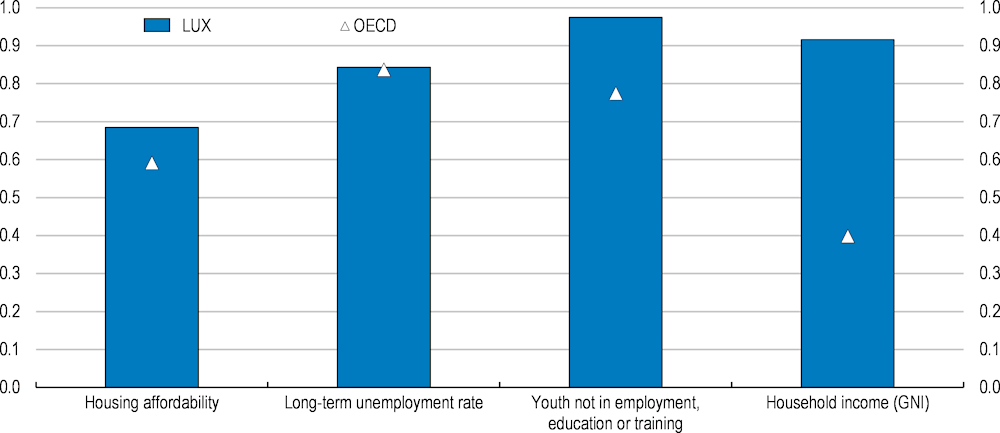

Luxembourg performs well relatively to other OECD countries across several non-economic indicators such as health, civic engagement, and safety, on top of high living standards (OECD, 2020[1]). Trust in government and in public institutions is above the OECD average and public integrity is perceived to be high (OECD, 2022[2]) There is still room for improvement: access to affordable housing is a concern, and educational attainment is uneven and strongly related to students’ socio-economic background (Figure 1.2) (European Commission, 2022[3]). While life satisfaction is comparatively high, obesity has been on the rise, in particular amongst younger people (OECD, 2020[1]). This could have an impact on the longer-term health of the population, and associated costs for long-term care of the elderly (European Commission, 2021[4]; OECD, 2021[5]; OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[6]). Environmental factors, such as high air pollution, also weigh on well-being in the country (OECD, 2020[1]).

Successfully maintaining the country’s high living standards, whilst transitioning to a green economy that secures the long-term health of the environment, will require fundamental changes in consumption and production patterns, and the effective use of all resources. Higher investments will be critical to enable this change, provided that they are aligned with long-term incentives to reduce carbon reliance and environmental protection. Successfully lengthening working lives, whilst maintaining the population’s health, will support growth, and also help reduce the pressure on housing, land and energy-use. This requires tackling longer-term challenges related to sluggish productivity growth and an ageing population, which will put pressure on government spending. Supporting higher productivity growth alongside the sustainable use of resources will minimise waste and the pressure on resources, ensure Luxembourgish firms are well-positioned to take advantage of new markets and reduce the need for drastic decisions on fiscal spending in the future.

Figure 1.2. Household income is high, but long-term unemployment and housing can improve

Well-being indicators, scale 0 (worst) to 1 (best), 2020

Note: This chart shows Luxembourg's relative strengths and weaknesses in well-being when compared with other OECD countries. The index is constructed so that 0 represents worst outcome and 1 represents the best outcome among OECD countries.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD How's Life? Well-being database.

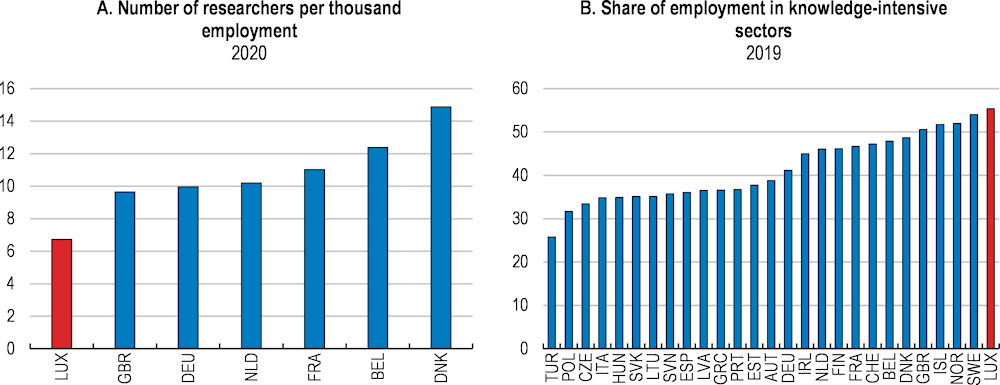

In terms of productivity levels, there are sharp differences between Luxembourg’s best performers and the global best performers, as well as within Luxembourgish sectors. While productivity in Luxembourg’s manufacturing sector, which includes large multinational firms such as Arcelor Mittal, often exceeds the OECD average, the sector is a small part of the national economy. Other sectors perform less well, including the large financial sector, which on average had the second lowest productivity (measured as value-added per person employed) in the OECD, in the period 2001-21 (OECD, 2021[7]). Skills-mismatches are high, which is also weighing on productivity, and those excluded from the labour force are difficult to integrate back into the system.

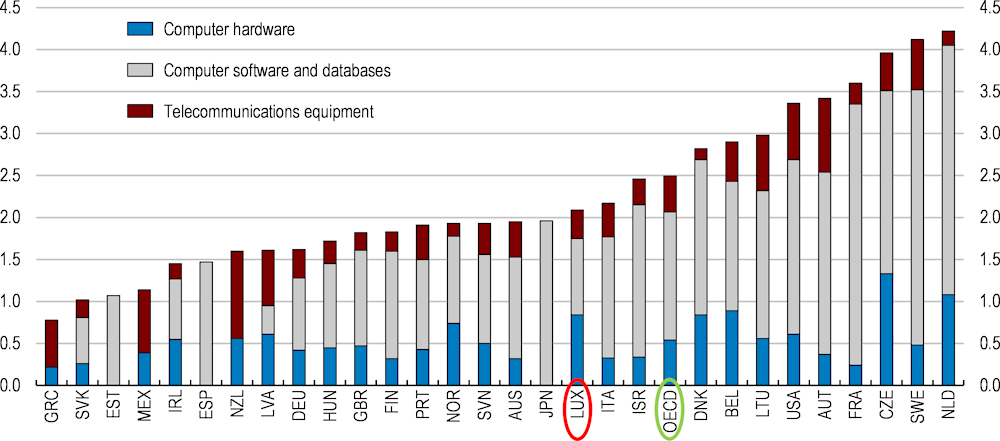

Strong public investment has not been matched by the private sector, owing partly to the structure of the Luxembourg economy which is characterised by a high share of financial services. Corporate investment as a share of gross fixed capital formation is the second lowest in the OECD, at 45.7% (compared with an average of 60% in the OECD, and 90% of total investment in Ireland), while the share of general government investment is the highest anywhere in the OECD (OECD, 2021[7]). A rapidly ageing population will pose challenges for sustaining workforce growth, particularly if current early retirement rates persist. The old-age dependency ratio will more than double (from less than 25% to more than 56%) by 2070, leading to a steep increase in pension expenditure and the cost of long-term care (European Commission, 2021[8]). Without efforts to raise productivity growth or increase labour supply to offset an ageing workforce, fiscal pressure will increase by more than 10 percentage points of GDP by 2060 (Guillemette and Turner, 2021[9]).

The transition towards a low-carbon and digitalised economy should be taken as an opportunity to support stronger long-term growth. The climate strategy to 2050 outlines a large number of plans to respond to climate risks. Strong co-operation between the state and the private sector in the financial services sector has supported innovation in the financial sector. More generally, the authorities have taken a proactive stance to create the foundations for a flexible, responsive, and fast-growing economy into the future. This is important since, given Luxembourg’s high economic openness, the country needs to be resilient to external shocks, such as higher inflation brought by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, or supply-chain shocks (Figure 1.3, Panel C).

In this context, this Survey’s key messages to strengthen further the resilience of the Luxembourgish economy in the face of new challenges are the following:

Fiscal support to households vulnerable to the current energy shock should be targeted and temporary to avoid fuelling inflationary pressures and to maintain incentives for energy savings. Significant reforms to the pension system are necessary to reinforce fiscal sustainability.

Migration policies and incentives to raise the working age in Luxembourg are required to offset the ageing workforce’s impact on potential growth. Lifelong learning programmes are needed to ensure workers’ adaptability.

Meeting ambitious green transition goals requires a broad set of policy tools. Reducing overall energy intensity requires adjusting incentives to densify housing and to reduce the reliance on cars. Setting a more ambitious long-term carbon-tax path, accompanied with adequate support for vulnerable firms and households, is also key.

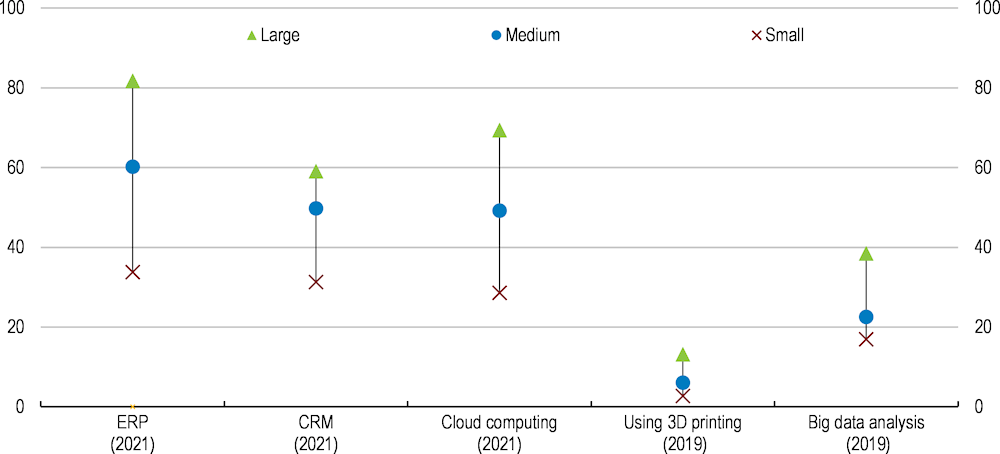

Raising productivity growth and reducing resource intensity requires laggard firms to absorb better existing innovations, and faster digitisation in small-and medium-sized firms (SMEs). To support productivity growth and economic diversification, public innovation investment should better target specific projects, while corporate R&D investment could be better supported through matching public funding.

Luxembourg rebounded strongly from the pandemic but is facing new risks

The post-COVID-19 recovery has been strong, but high inflation creates significant risk

The economy proved resilient to the COVID-19 pandemic, thanks notably to decisive government action early on. COVID-19 support measures were sizable and equivalent to just over 4.2% of GDP, including government loan guarantees as detailed in a 2022 OECD report on the Luxembourgish government’s response to the pandemic (OCDE, 2022[10]). Household assistance during the pandemic included direct income support, supplemented with financing of partial unemployment. Firm level support included direct transfers as well as furlough schemes to help meet staff costs. COVID-19 related assistance was broad-based and delivered quickly, in keeping with best practice given the breadth and depth of the economic shock. Most of the assistance was directed towards employment support, with a higher share of GDP directed towards wage support than many peers. A relatively high proportion of liquidity support was provided via deferred tax and social security payments, which were almost double the value of guarantees granted. To date, the long-term impact on the economy from bankruptcies and permanent exclusion from the labour force seems limited (OCDE, 2022[10]). Government support has continued to respond to ongoing shocks.

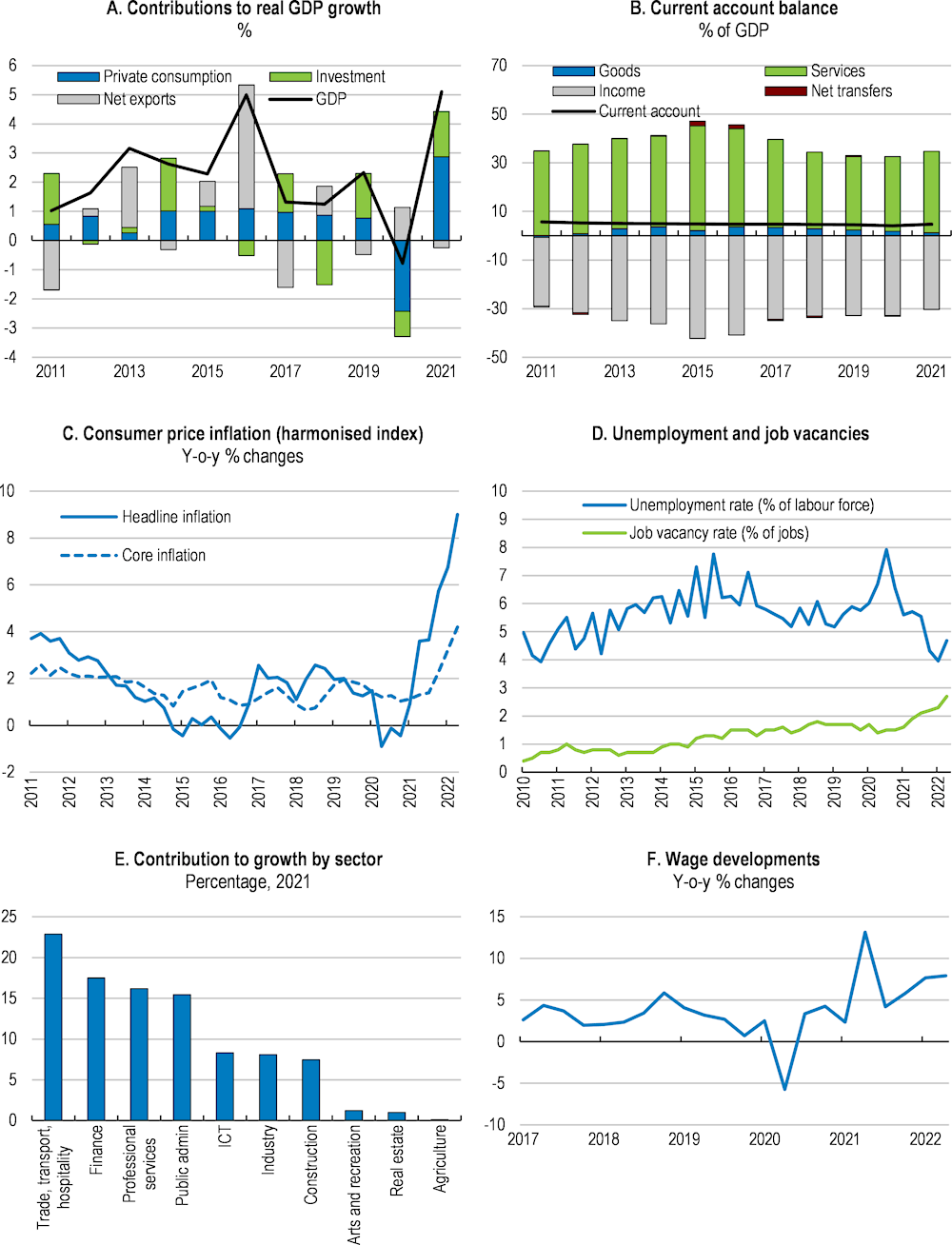

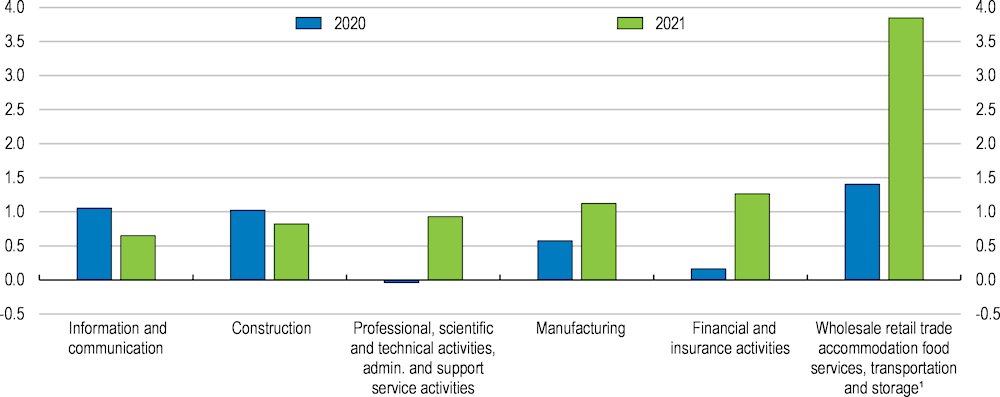

The high share of services that could rely on teleworking also helped limit the impact of the crisis. Nearly 40% of jobs are in the services sector, including public administration. The downturn in 2020 was comparatively mild, and the recovery has been robust, taking real GDP growth to 5.1% in 2021. A strong recovery in financial markets lifted growth in the financial sector, which accounts for around 25% of the economy.

Job creation has been brisk since mid-2021, in step with the recovery. Total unemployment is at its lowest level for over 15 years, and vacancies are high (Figure 1.3, Panel D). Thanks to buoyant activity, the surplus on services trade has supported a persistent current-account surplus in recent decades of around 4%-5% of GDP, despite large deficits on the primary income account (Figure 1.3, Panel B).

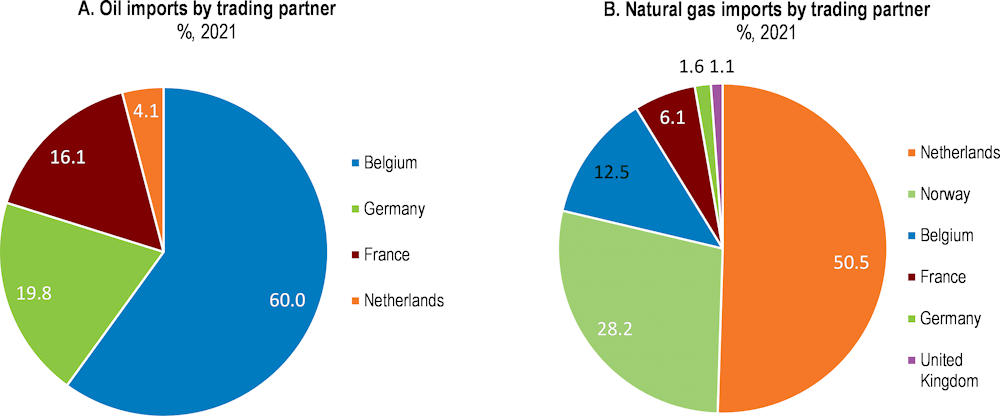

Figure 1.3. Growth is broad-based, and pressures are rising in the economy

Luxembourg, as the rest of the European Union, has been affected by the rising gas and electricity prices owing to the supply restrictions arising from the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine, even though Luxembourg has relatively little direct exposure to Russia, which accounts for just 1.7% of total trade. Base metals imported directly from Russia account for just 0.4% of all base metal imports, versus 97% from the European Union (some imports may have transited through third-party countries, but this is not accounted for in official data). Oil and gas imported directly from Russia are negligible (Figure 1.4). Natural gas accounts for 25% of all energy consumption and much of the gas imported is used for industrial purposes, mainly steel and glass manufacture, but also in the textile and cement industries, in addition to electricity production. Imported gas runs mainly from LNG terminals in Belgium, which increases potential suppliers, for instance from Canada or Algeria. Luxembourg does not possess its own gas storage facilities, but it participates in the Pentalateral Forum on Energy (comprising Benelux, France, Germany, Austria and Switzerland). An agreement was signed in late March 2022 to improve gas storage co-operation, and to force suppliers to fill stocks before the winter heating period (Gouvernement Luxembourgeois, 2022[11]).

Figure 1.4. Exposure to Russia’s oil and gas is negligible

Oil and gas imports, 2021

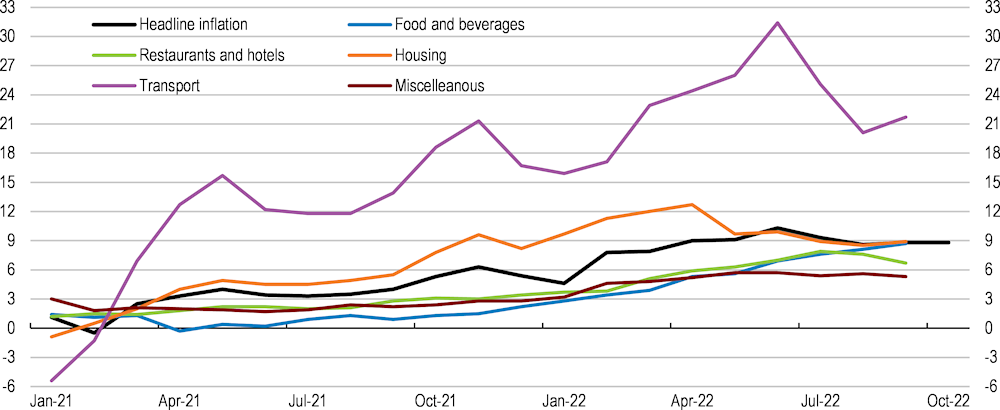

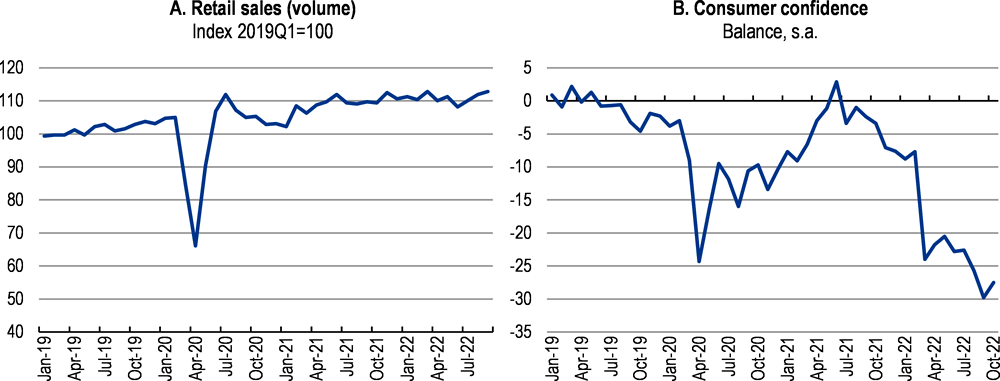

Russia’s war against Ukraine has aggravated inflationary pressures, which had already started building towards the end of 2021 on the back of supply bottlenecks. While some increases are supply-driven, rising demand is also contributing, and inflation has broadened to include personal services, travelling and entertainment, as well as clothing and household goods (Figure 1.5). Headline inflation is expected to average 8.2% in 2022 according to the harmonised price index, on the back of higher energy and food price inflation. Rising inflation is eroding consumer confidence and disposable incomes (Figure 1.6) and, combined with labour market bottlenecks, fuels wage pressures. All wages, salaries, and some social benefits, such as pensions and family allowances, are indexed to inflation. They are automatically increased by 2.5% when the price level has gone up by 2.5% since the time the last wage indexation occurred. The total wage rate rose by 5.4% in 2021, in part owing to a wage increase of 2.5% in October 2021 because of the wage indexation scheme. A further 2.5% increase occurred on 1 April 2022 when the automatic indexation kicked in again, contributing to the 6.2% annual rise in hourly wages in the second quarter of 2022.

Figure 1.5. Inflation is broad-based

Headline inflation and its main components, year on year % change

Note: "Housing" includes housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels; "Miscellaneous" includes personal care, social protection, insurance, and other services n.e.c.

Source: Eurostat, Harmonised Price Indices.

Figure 1.6. War and rising inflation are depressing consumer confidence

Source: OECD, Monthly Economic Indicators (database); and Eurostat, Business and consumer surveys (database).

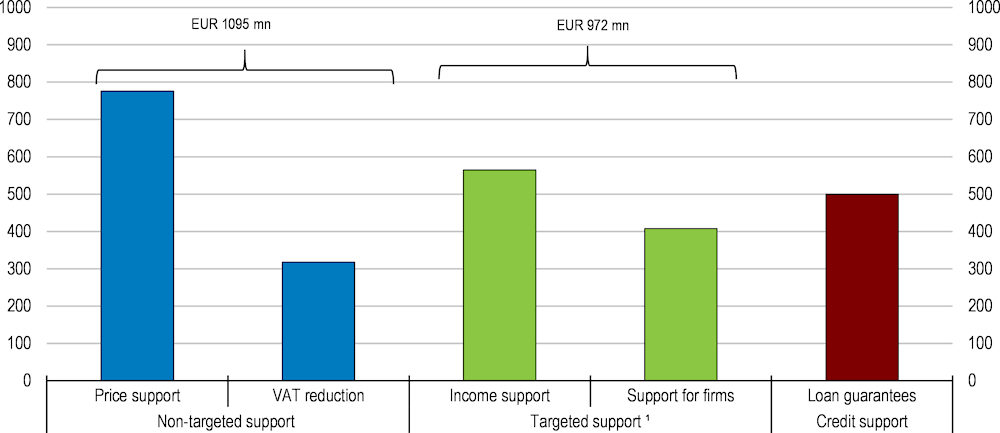

To mitigate the negative effects of rising prices on household incomes and competitiveness, the government responded with a series of support packages costing close to EUR 2.6 billion (3.3% of GDP). The total cost of the latest package, agreed with social partners in September 2022, is EUR 1.1 billion. The latest measures aim to limit inflation increases – and related wage-indexation increases – by capping domestic gas and electricity price increases between October 2022 and December 2023, and reducing most VAT rates by 1 percentage point in 2023. Rent subsidies and an annual energy bonus for lower-income households, introduced earlier in 2022, have been extended into 2023. Until June 2023, businesses can apply, if their energy costs are at least 80% higher than in 2021, for a subsidy covering 70% of their additional energy costs over and above this 80% increase. Moreover, state-backed business guarantees remain in place (Le Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, 2022[12]). Subsidies for energy efficiency investments were strengthened and introduced for long-term renewable energy power purchase agreements. Social partners agreed that any future wage indexation increases will be implemented in full. In March, they had agreed to postpone the July 2022 wage indexation increase until 1 April 2023.

Figure 1.7. Policy support is tilted towards non-targeted measures

Budget measures 2022-23, Euro million

1. Targeted measures are directed at households or firms, based on criteria such as income or energy consumption levels.

Source: Ministry of Finance, Draft Budget Plan 2023, OECD estimates.

New sizeable energy price increases could pose risks for firms and households that are unable to quickly reduce energy consumption Targeted support measures are welcome as there is a small but growing set of households in energy poverty, at 4.9%. The government’s latest support package is estimated to limit expenditure increases from higher living costs to 3% for all income groups in 2022 (STATEC, 2022[13]). In addition, an expanded and free public transport network provides important flexibility to reduce transport-related energy consumption, and subsidies for energy efficiency investments in homes and businesses are available.

The risks arising from policy support in the form of price measures will rise if energy prices are very high over the medium term. Wage increases from indexation would be postponed, and could increase pressure for continued fiscal support. VAT reductions may not be fully passed on by business and could be difficult to phase out. Price caps for gas and electricity will disproportionately benefit those who consume the most, and are likely to blunt incentives to lower consumption. Overly generous support to protect households’ income could further increase inflationary pressures, which are already broadening to include personal services, travelling and entertainment, as well as clothing and household goods.

To minimise these risks, the authorities should ensure that support is temporary and well-targeted to the most vulnerable. The government should monitor the impact of VAT reductions, and ensure rates are normalised promptly, as Germany did in 2020-21. More targeted support measures, delinked from energy consumption, would be a more effective tool to support the most vulnerable without blunting the incentives to increase energy efficiency. This is particularly the case in Luxembourg, where the retail price of energy is relatively low compared to neighbouring countries (see Chapter 2). Price caps can be applied to a fixed quantity of energy per household to minimise energy savings disincentives. In the Netherlands, price caps were applied to the quantity of gas consumed by the median household, with higher levels of consumption incurring higher prices.

Government support to firms must avoid the risk of encouraging low-productivity “zombie” firms that are unviable without state support. Support to firms should be targeted to viable firms, whose cost structure make them particularly vulnerable to high energy costs. Larger firms that have access to finance or pricing power can better manage the transition to higher energy costs. To the extent that government supports these firms in the energy transition, it should encourage the switch to alternative production technology (see Chapter 2).

The current period of high inflation has highlighted the potential risks stemming from the automatic wage indexation system. Wage indexation can induce a price-wage spiral, particularly in the current context of high inflation and tight labour markets. Shocks to inflation can have longer-lasting effects in the presence of second-round effects, and the latter are more are more likely in the presence of wage indexation. There is also a risk of a longer lasting upwards effect on inflation expectations (Lünnemann and Wintr, 2010[14]; Koester and Grapow, 2021[15]; Boissay et al., 2022[16]). Generalised wage increases also disproportionately benefit those with higher salaries.

Although Luxembourg’s social partners have demonstrated pragmatism in considering the impact of indexation, agreements can take time to implement. There is no clear policy to guide lawmakers or social partners as to how best apply retroactively any delayed increases in indexation, such as the one that was decided by the social partners in March 2022. Retroactively introducing these increases could exacerbate business cycle effects, if introduced too early or too late in the recovery. After the current period of high inflation, social partners should be consulted, and the government should implement reforms to the wage-indexation system to better guard against the risks to productivity, employment and inflation.

Whilst wage indexation mechanisms are intended to protect living standards, they can have a detrimental effect on competitiveness. In Belgium, the wage formation process is legally prescribed by a ceiling for wage growth, known as the wage norm, and wage indexation. The wage norm varies over time, and is set with reference to historic divergences in wages between Belgium and its main trading partners, projected Belgian inflation, projected wage growth in core trading partners and a “safety margin” to account for forecasting errors (OECD, 2022[17]). The OECD recommended to Belgium to closely monitor the effect of wage and price inflation on international competitiveness (OECD, 2022[17]). Connecting wage indexation to other countries’ wage growth could be part of a solution to protect competitiveness. However, a broader range of cost-competitiveness criteria could be considered and be given a sufficiently high weight.

Growth will slow down in 2022-23 and risks are on the downside

GDP will slow to around 1.7% in 2022 and 1.5% in 2023, before picking up to 2.1% in 2024. Falling consumer sentiment, supply constraints in goods exports and slowing manufacturing activity, along with rising global interest rates will hold back economic growth in 2023 (Table 1.1). From a household perspective, higher interest rates will increase payment obligations and the vulnerability of certain borrowers, particularly those with lower incomes or with variable rate loans, and confidence has plummeted to the lowest level in two decades owing to the war in Ukraine and rising uncertainty (Figure 1.6). Nonetheless, government support and a cut in VAT rates, alongside a still-strong labour market, are expected to partially offset the impact of high inflation on disposable incomes and will sustain private consumption in 2023. Spending is set to pick up as energy prices normalise towards the end of the forecast period, and inflation starts falling back during 2023, as a result both of rising interest rates, and some impact from the energy price cap and VAT rate cuts. Core inflation is projected to be sustained in 2023, owing to second round effects of energy price increases, high wage growth and supply-constraints related to COVID-19 lockdowns in China. If energy prices stay high for longer, inflation may remain higher than foreseen, and household demand could be further depressed.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices)

|

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

|

|

Current prices (billion EUR) |

|||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

60.1 |

2.3 |

-0.8 |

5.1 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

|

Private consumption |

20.2 |

2.3 |

-7.2 |

9.4 |

2.8 |

2.0 |

|

Government consumption |

10.1 |

2.3 |

7.3 |

5.5 |

2.9 |

3.4 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

9.7 |

9.3 |

-3.2 |

6.1 |

-2.8 |

-2.5 |

|

Housing |

2.3 |

4.9 |

-2.8 |

-11.3 |

-4.6 |

-2.2 |

|

Final domestic demand |

40.0 |

4.0 |

-2.5 |

7.5 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

-0.3 |

0.5 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

40.5 |

4.0 |

-2.9 |

8.4 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

118.7 |

4.5 |

0.2 |

9.7 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

99.0 |

5.7 |

-0.5 |

11.9 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

|

Net exports1 |

19.6 |

-0.5 |

1.1 |

-0.2 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

||||||

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

2.0 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

|

Output gap2 |

. . |

0.5 |

-2.3 |

0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.7 |

|

Employment |

. . |

2.7 |

1.4 |

2.3 |

2.7 |

2.2 |

|

Unemployment rate |

. . |

5.4 |

6.4 |

5.7 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

1.4 |

4.6 |

6.1 |

6.0 |

1.1 |

|

Consumer price index (harmonised) |

. . |

1.6 |

0.0 |

3.5 |

8.2 |

4.0 |

|

Core consumer price index (harmonised) |

. . |

1.8 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

4.5 |

4.1 |

|

Household saving ratio, net3 |

. . |

8.3 |

19.0 |

12.4 |

12.9 |

14.9 |

|

Current account balance4 |

. . |

3.4 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

6.4 |

5.6 |

|

General government fiscal balance4 |

. . |

2.2 |

-3.4 |

0.8 |

-0.2 |

-2.2 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance2 |

. . |

2.0 |

-2.1 |

0.6 |

-0.1 |

-1.9 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance2 |

. . |

1.7 |

-2.3 |

0.3 |

-0.3 |

-2.1 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht)4 |

. . |

22.4 |

24.5 |

24.6 |

27.0 |

30.5 |

|

General government net debt4 |

. . |

-54.2 |

-50.1 |

-51.9 |

-48.0 |

-44.5 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

0.6 |

3.8 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

-0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.4 |

1.9 |

5.1 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. As a percentage of household disposable income.

4. As a percentage of GDP.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) with projections from "OECD Economic Outlook No. 111" and updates, November 2022.

Public investment of over 4% of GDP annually will continue to support infrastructure, the green transition, and innovation. Business investment, in contrast, will be subdued in 2022-23 as higher interest rates, labour market shortages and supply constraints delay investment decisions, despite some support from the government Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP). Because Luxembourg’s economy recovered fairly swiftly from the COVID-19 pandemic compared to some other EU member states, the total size of the NextGenerationEU (NGEU) recovery package (of which the RRP is part) for Luxembourg was reduced from an initial EUR 93 million to EUR 82.7 million. The impact on GDP for Luxembourg is highly dependent on spillovers from neighbouring countries. The European Commission has estimated that 0.7 percentage points of the total projected 0.8% GDP impact by 2026 will come from spillovers from the packages of other countries (European Commission, 2021[18]). These estimates do not include the impact of additional structural reforms, which could significantly boost the overall growth benefits (European Commission, 2021, p. 38[18]). Box 1.1, and Table 1.5 present OECD estimates of the impact of these structural reforms. As discussed further in this chapter, the labour market is tight, and several sectors are struggling to find enough skilled workers, including in the construction and the information-communications-technology (ICT) sectors, which may hamper implementation of the RRP. Export growth will moderate, as global financial market conditions remain difficult, and some supply-chain restrictions endure.

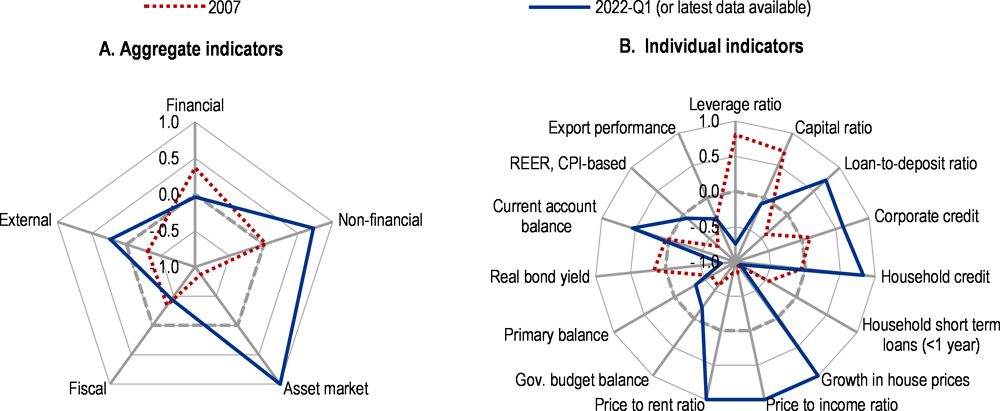

Risks to the outlook are tilted to the downside. Domestically, low interest rates in recent years have compounded the impact of structural factors in supporting rising real-estate prices and increased mortgage indebtedness. Indicators point to historically high risk in the credit and housing markets (Figure 1.8), although holdings of financial assets and wealth gains for past price increases should mitigate the impact of potential shocks. Externally, Luxembourg remains vulnerable to supply-side shocks, which would affect its main trading partners. Further sharp rises in inflation and long-term borrowing rates would worsen financial conditions, and cause stock markets valuations to fall. If this was to be compounded by defaults of bonds or a sharp drop in investment fund assets, for instance in the case of a faster-than-expected tightening of monetary policy, this could create a ripple effect in financial markets, which could harm Luxembourg’s growth prospects (see also Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Low-probability events that could lead to major changes to the outlook

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcome |

Possible policy action |

|---|---|---|

|

Sharply reduced housing prices |

Sharp reversals in real estate prices and steep increases in interest rates could put some households in financial distress and endanger financial stability. |

Address structural factors in housing and construction markets that contribute to supply shortages. If appropriate, broaden borrower-based macroprudential instruments. |

|

Escalating trade tensions or heightened financial volatility because of the war in Ukraine could affect the investment fund industry. |

A sharp reduction in global liquidity causes heightened redemptions in investment funds and money market institutions, reducing financial sector output globally, including in Luxembourg. |

Maintain close supervision of banks and investment funds. Potentially increase minimum reserve requirements to preserve liquidity. |

|

Outbreak of a new vaccine-resistant COVID-19 variant |

New waves of vaccine-resistant infections could potentially lead to new lockdown measures, further reducing confidence and lowering domestic consumption. |

Monitor health developments closely and continue to encourage vaccination, including booster shots. Keep contingency plans for moving to online work where possible and maintain stocks of personal protective equipment even as infection rates slow. |

Figure 1.8. Macro-financial vulnerabilities have increased in the asset and housing markets

Index scale of -1 to 1 from lowest to greatest potential vulnerability, where 0 refers to long-term average

Note: 1. Each aggregate macro-financial vulnerability dimension is calculated by aggregating (simple average) normalised individual indicators from the OECD Resilience Database. Individual indicators are normalised to range between -1 and 1, where -1 to 0 represents deviations from long-term average resulting in less vulnerability, 0 refers to long-term average and 0 to 1 refers to deviations from long-term average resulting in more vulnerability.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2022), OECD Resilience Database, April.

Financial sector risks are rising

Fast-rising housing prices pose challenges

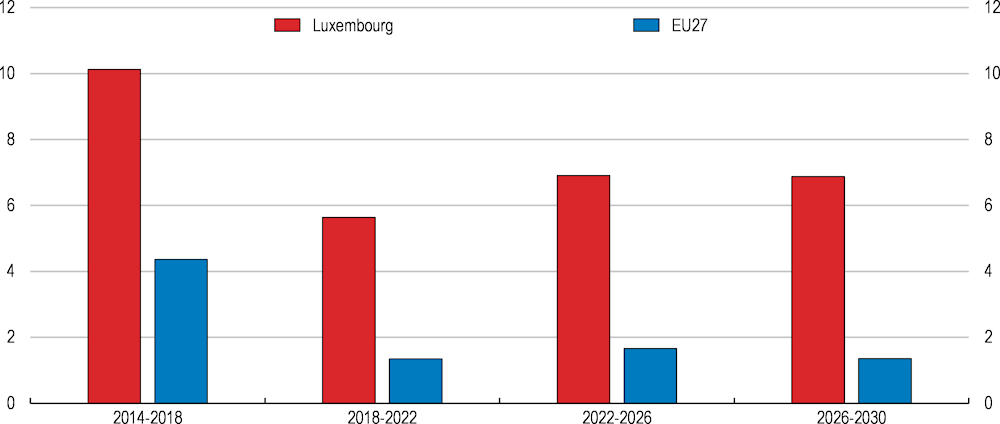

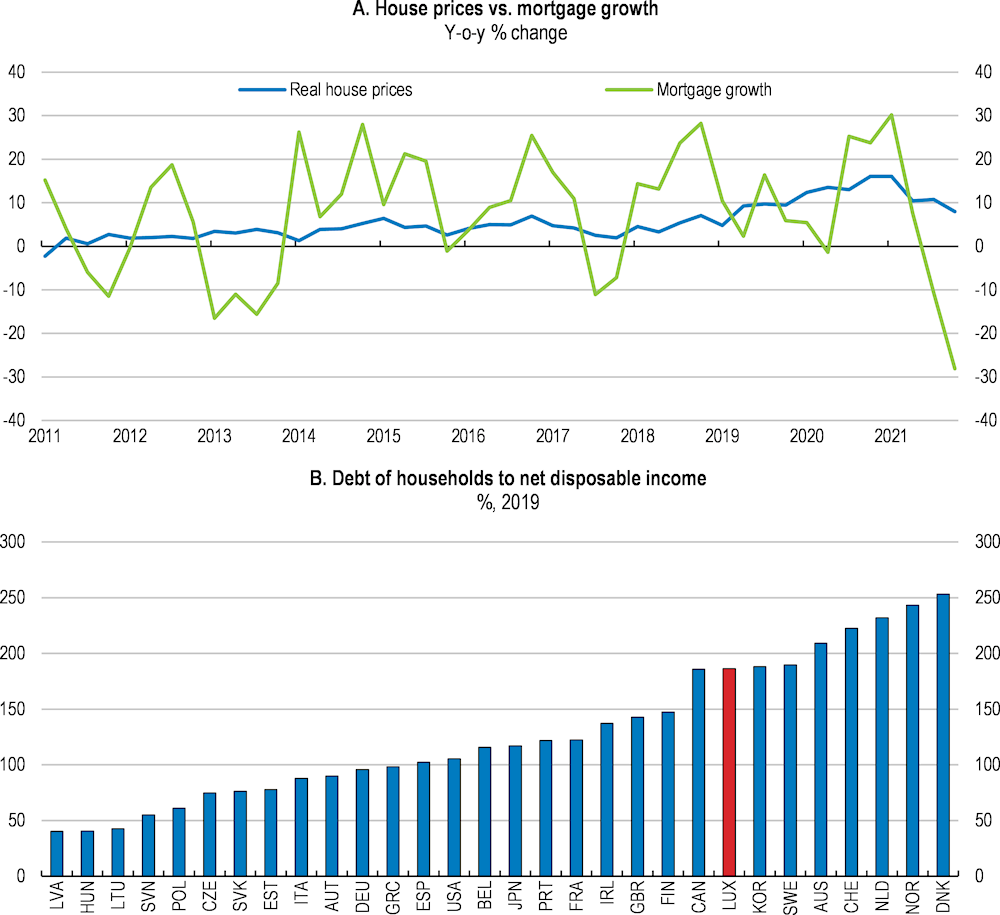

House prices have been increasing rapidly since the start of 2019 for both new and existing dwellings. On average, prices have risen by 9.7% per annum over the past five years, almost double the 4.9% EU average. The sharp increases in housing prices have worsened most household affordability ratios. Mortgages account for the bulk of household debt, which stood at 180% of total net disposable income in the first quarter of 2022 (Banque Centrale du Luxembourg, 2022[19]) (Figure 1.9). Price-to-income ratios are well above their long-term trends. Aggregate debt service to income ratios have remained high since 2018 at above 40% for all income categories. Loan-to-value ratios of new loans increased since 2018 from 73.0% to 76.5%. New loans are increasingly weighted towards those with higher incomes.

The risks to the financial sector from the housing market boom require continued monitoring. Aggregate sector exposures are low: household debt makes up just under 10% of the total banking loans issued, and almost two-thirds of that are in Luxembourgish mortgages. However, most of this debt is held by a handful of Luxembourgish banks, who hold on average 22% of their assets in mortgages. This concentration requires intensified monitoring, as these banks could suffer difficulties if house prices decline in response to higher interest rates.

From a household perspective, higher interest rates could increase payment obligations and the vulnerability of certain borrowers, particularly those with lower incomes. 51% of homeowners still have variable rate loans (Banque Centrale du Luxembourg, 2022[19]), even though since 2015, most new loans have been issued at a fixed rate, and central bank estimates of loan origination suggests many households renegotiated at lower fixed rate mortgages (Banque Centrale de Luxembourg, 2022[20]). Valuation gains in houses and holdings of liquid assets should help borrowers smooth any shocks to interest payments. Residential real estate data from the regulator (Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier‑CSSF), shows that debt-service-to-income ratios of lower- and medium-income households (earning less than EUR 75 000 a year) are 42%, similar to the 40% average of all households. Debt-to-income ratios are 999% for lower and middle-income households, compared to an average of 1024% for all households. 31% of low-income households in Luxembourg are overburdened by housing costs, compared to 28% in the European Union, according to the 2020 Eurostat Survey on Income and Living Conditions (Koulischer, Perray and Tran, 2021[21]). Luxembourg faces a much lower risk of default on mortgages within five years in the case of job loss than t neighbouring countries (3% compared to 10%) (IMF, 2021[22]). Nonetheless, the IMF (IMF, 2021[22]) estimates that low and middle-income households face a much higher risk of default (30%) than this average, in the event of losing their job.

The authorities activated several new macroprudential policy measures in 2021 to protect borrowers from housing market risks. As of January 2021, legally binding loan-to-value limits have been put in place, of 80% for buy-to-let loans, 90% for primary residence loans and 100% for first time buyers. A higher countercyclical capital buffer requirement of 0.5% of common equity tier 1 capital was also introduced in 2021. Macroprudential policy may have helped to reduce tail-risks for new borrowers (IMF, 2021[22]) According to the CSSF, 35% of new loans with a debt-to-income ratio above 900% went to lower-income households in the second half of 2021, down from 41% a year earlier. The current rising interest rate cycle is expected to further reduce risk appetite, mortgage lending and house prices. Nonetheless, authorities should stand ready to apply additional macroprudential measures if needed. In Norway, Sweden and Denmark, countries with buoyant housing markets, counter-cyclical capital buffers are 1.5% and will increase further in 2023.

Borrower-based measures such as debt service to income caps can help mitigate risks whilst potentially restricting access for first-time buyers less (OECD, 2021[23]). An expanded set of regularly updated public data to evaluate housing market developments and risks by household borrower types could support policy co-ordination. For example, higher interest rates or macroprudential policy to reduce borrower vulnerability could reduce mortgage access for certain types of borrowers, who might be in a particular need of a mortgage to finance deep renovations to green their homes. A regularly published report, with analysis according to household income categories as well as buyer types, could increase information to policy makers and the market. For example, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority publishes an annual report on the local mortgage market, with detailed information on the volume and distribution of household debt, as well as stress-test related information. Expanding the set of aggregate indicators to also estimate the risks of over-consumption and over-investment associated with the housing market would improve understanding of the channels through which the housing boom may affect macroeconomic stability (Svensson, 2020[24]). The Bank of England for example provides estimates of housing equity withdrawal.

In addition to macroprudential measures, a wide range of measures will be necessary to increase the flexibility of housing supply over the long term. Structural factors have played an important role in supporting high house-price growth. Land hoarding and high administrative costs (e.g. lengthy building permissions procedures) have hindered investment in the housing stock, exacerbating the impact of continued population growth, shrinking household sizes and demand for larger homes (OECD, 2019[25]; Reinesch, 2022[26]; Paccoud et al., 2021[27]; Observatoire de l’habitat, 2022[28]).

The government has taken steps to raise housing supply (Table 1.3). Planned increases in national tax rates for vacant land and unused buildings to discourage land hoarding are welcome and must be implemented quickly (OECD, 2019[25]). Increasing the supply of affordable housing is a core focus of the government’s strategy. The Pacte Logement 2.0, released in 2021, includes technical and financial support for municipalities to develop their affordable housing strategies, and financial incentives to increase the supply of rental housing. Social housing must make up a defined minimum amount in new developments under the special development plan, which will be transferred to municipalities or the state. The supply of government-built affordable housing units is expected to increase by approximately 200 units a year. Housing supply incentives should only apply to areas identified for development in the Master Programme for Spatial Planning, to discourage further urban sprawl and car usage (see Chapter 2). Encouraging greater densification of homes alongside energy efficiency renovations could help to reduce the pressure on the built environment and reduce the potential trade-off between housing supply and resource intensity (see Chapter 2).

Figure 1.9. The housing market continues to place households under pressure

Source: OECD Analytical house price indicators; Banque Centrale du Luxembourg; and OECD, National Accounts at a Glance.

Mortgage interest deductions for owner occupied property should be removed gradually to reduce distortions in housing demand, which favour wealthier households (OECD, 2019[25]). To ensure that this does not hurt access to the housing market, the interest deduction could be replaced by more targeted measures, such as an income-tested property tax credit (Causa, Woloszko and Leite, 2019[29]). In the United States and Canada, some regional governments provide lump sum exemptions, whilst others provide support in the form of tax credits to low-income families (Brys et al., 2016[30]). Increasing immovable property taxes could bring wider socioeconomic benefits. Whilst corporate wealth taxes are relatively high, Luxembourg currently collects almost no recurrent taxes on immovable property compared to a level of 1% of GDP on average in the OECD. In addition to potentially raising revenue (OECD, 2018[31]) and increasing housing supply, higher immovable property taxes could support a more sustainable housing market and encourage investments in other assets, rather than residential property. The liquidity impact of raising property taxes on people with low incomes and non-liquid assets could be managed by spreading immovable property tax payments throughout the year.

Table 1.3. Previous recommendations to boost economic resilience and access to housing

|

Recommendation |

Action taken |

|

Produce additional macro prudential measures, such as limits to loan-to-value or loan-to-income ratios. |

The law of 4 December 2019 sets out the macroprudential framework for activating borrower-based measures, such as limits to loan-to-value, debt-to-income and debt-service-to-income. Binding loan to value limits became effective on 1 January 2021. |

|

To increase the stock of social rental housing while preserving social mixity, directly finance new land acquisition by public providers of social housing. |

Public spending on the creation of affordable housing has increased from EUR 40 million in 2017 to EUR 170 million in 2021. Legislation to finance the construction of at least 6000 homes with a cost of over EUR 1.5 billion was approved. The Pacte Logement 2.0 increased local authorities’ power to purchase land and set minimum social housing requirements for developments that will pass to the hands of the state. Developers will in exchange be allowed to densify the land more than current regulations. |

|

Increase taxation of non-used constructible land. Turn recurrent taxes on immovable property into a more important fiscal resource, e.g. by regularly aligning the tax base with the market price of the property. |

As part of a wider reform to map all properties and update cadastre values, it is planned to impose taxation on unused, constructible land. A full review of the cadastre, with a view to updating property values and mapping unused land and housing is being undertaken in 2022. |

|

Phase out or at least reduce the current mortgage interest deduction |

No action taken. |

|

Link housing allowances and rents in the social housing sector to reference rents at the local level, in order to ensure lower-income households’ access to areas in the city centre. |

No action taken. |

Financial risks need to keep being closely monitored

Low interest rates in recent years have been supporting high levels of demand and risk appetite, which in turn have underpinned rising asset prices. Luxembourg has benefitted from the resultant steady growth in financial market activity. However, low rates have also imposed costs. Low interest rates have contributed to low bank profitability, as in most of Europe. More recently, the robust local economic recovery in the context of the low interest rates has contributed to accelerating inflation. The lags in price setting could mean that inflation continues to increase even as economic activity slows in response to higher interest rates. If the euro area monetary policy stance proves too loose for Luxembourg, additional financial (but also fiscal, see next section) measures might need to be taken.

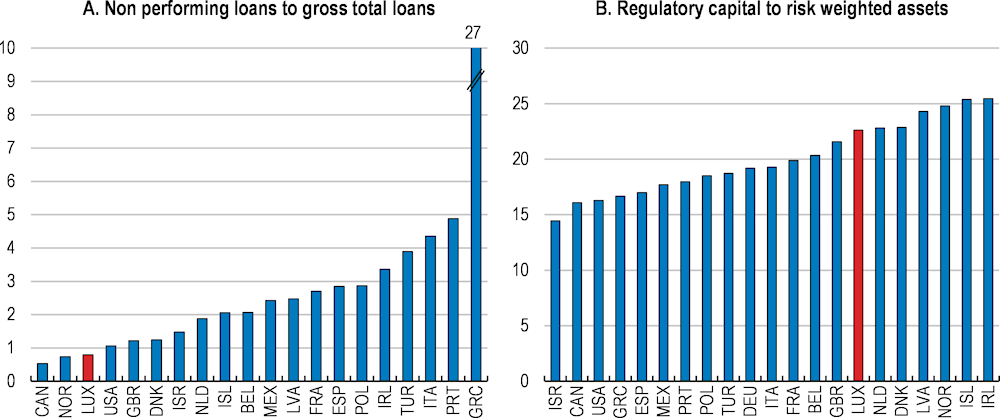

Luxembourg’s financial industry is well placed to cope with potential risks, and several steps have been taken since the last Economic Survey to raise its resilience (Table 1.4). Assets held by the financial sector grew by a robust 24% between 2019 and 2021. Supportive global fiscal and monetary policy offset market turbulence and the COVID-19 crisis. Non-performing loans are low as a share of total assets compared to OECD counterparts (Figure 1.10, panel A). Regulatory capital buffers are high (Figure 1.10, panel B), and liquidity has been increasing, even as capital buffers have fallen. The banking sector received around 60% of its deposits from financial intermediaries in 2021. Historically, investment funds’ bank deposits have increased in periods of high volatility. Authorities have continuously enhanced system-wide oversight of the investment funds sector. The proactive stance of regulators and firms in developing products to best utilise the green and digital transitions has maintained the attractiveness of Luxembourg as a financial market.

Nonetheless, as global monetary policy tightens, strains will increase, warranting continued monitoring. In March 2022, it was estimated that 17% of Luxembourgish banks had made a loss in 2021 (CSSF, 2022[32]). Higher rates should help to restore profits over the long term for both insurers and banks. However, in the short term, both banks and insurers will have to contend with the drop in the market value of their fixed-income holdings. In addition, non-performing loans are likely to rise further in 2022 and beyond, given that the war implies a second shock in quick succession for vulnerable firms, not just in Luxembourg but in Europe as a whole. Support from EU governments for firms affected by the war has not been as large as during the COVID-19 pandemic, although loan guarantee schemes have been increased in many countries including Luxembourg, helping to mitigate credit risk somewhat (Table 1.4). Heightened financial market volatility could prompt outflows and procyclical asset sales by investment funds, particularly open-ended ones. The authorities should continue to monitor banking exposures, including large cross-border exposures and intra-group transactions. They have undertaken a number of efforts to strengthen the investment fund sector’s macroprudential monitoring, including system-wide liquidity stress testing, and these efforts should continue.

Figure 1.10. The financial sector is in a strong position to respond to additional shocks

Note: Data for 2021 for Denmark, Iceland, Latvia, Luxembourg and Poland. All other countries 2020.

Source: IMF Financial Soundness Indicators.

Table 1.4. Previous recommendations to improve fiscal resilience and financial market surveillance

|

Recommendation |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Develop further the capacity to undertake regular system-wide stress tests of fund-bank linkages and consider publishing their results. |

The domestic regulator (CSSF) now runs fund-bank interlinkage stress tests twice a year. High-level results are shared with interested external public organisations. |

|

Improve access to credit for SMEs by introducing a central credit registry |

Anacredit, a central credit register for Luxembourg, is currently under construction by the BCL in co-operation with the European System of Central Banks. |

|

Continue to engage in international efforts to address tax challenges of cross-border activities and to strengthen tax transparency. |

Luxembourg has transposed directives implementing automatic exchange of information and introduced several OECD BEPS measures. Legislation has been passed to strengthen beneficial owners’ registers, with a new register created for trusts and requiring foreign nationals to use a national identity number in the companies register. |

|

Allow automatic stabilisers to work in case of a downturn and, if it intensifies, implement a countercyclical fiscal expansion. |

The government has responded to ongoing shocks. COVID-19 support measures included direct income support to households and financing of partial unemployment and maintenance of minimum wages. Support to firms included direct transfers and furlough schemes to meet staff costs. The total cost was over 4.2% of GDP and 8.6% of public expenditure. Support packages have also been implemented to respond to high energy prices. |

The fight against money laundering has been given greater prominence

The authorities have further strengthened legislation to reduce the risks of money laundering and corruption since the last Economic Survey. Important advances include strengthening beneficial owners’ registers, with a new register created for trusts and requiring foreign nationals to use a national identity number in the companies register. This activity is appropriate given the need to maintain the standing of Luxembourg in global finance. Compulsory compliance with the national identity numbers system should be accelerated, instead of leaving an open-ended timeline.

Luxembourg’s digital sophistication could be better harnessed in the fight against money laundering. Big data techniques are used by the prudential regulator to identify risks related to investment funds. They should be a core part of the strategy employed by the prudential supervisor to assist the Department of Justice to identify an increased number of cases for audit based on risk profiles. In France, for example, the prudential authority makes use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to understand risks. The prudential regulator could also provide guidance on how to manage anti-money laundering risks using artificial intelligence and machine learning, in much the same way it published guidance on the use of distributed ledger technologies and blockchain (CSSF, 2022[33]). In Hong Kong, case studies of “Reg-tech” solutions have been published to provide concrete examples to the market on how to tackle risks, including verifying customer identity and monitoring transactions (Ashurst, 2022[34]). Sharing information across financial institutions can also be a way to investigate risks, if privacy risks are appropriately managed. In Singapore, the monetary authorities have been working with six of the largest financial institutions to create a safe data platform to share information (Ashurst, 2022[34]).

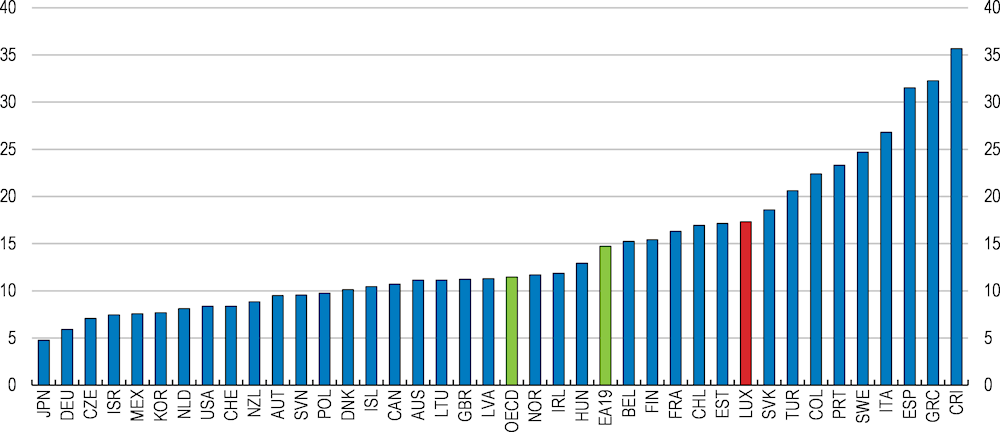

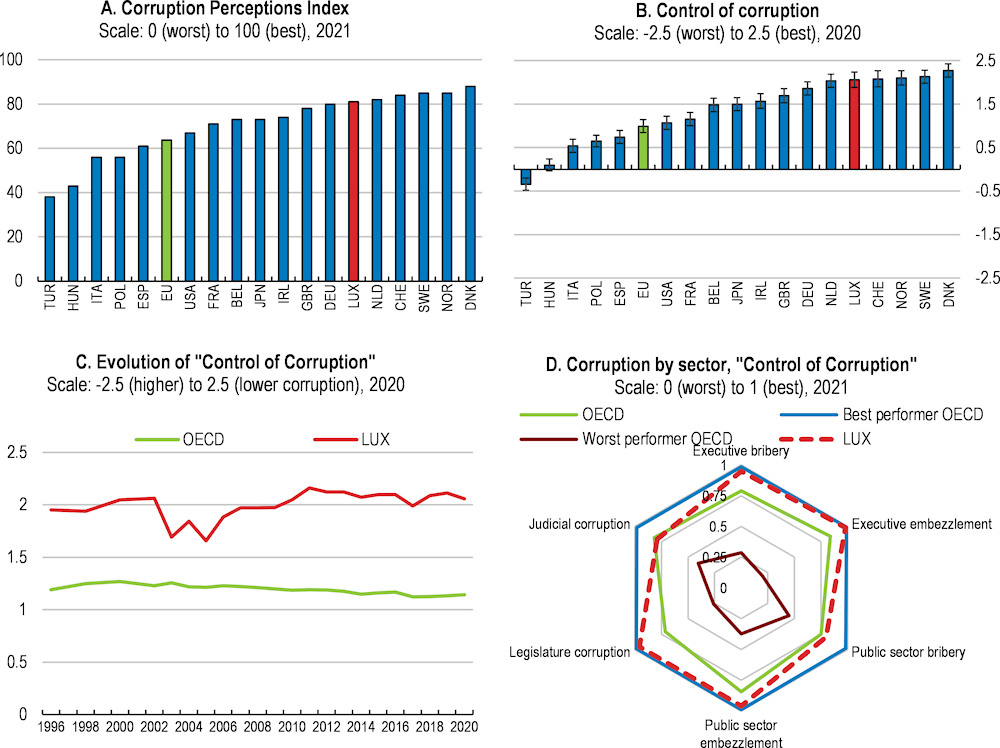

Overall perceptions of corruption remain low in the country, with Luxembourg one of the best performers in the OECD (Figure 1.11) A constitutional amendment is underway to strengthen the independence of the judiciary from an already high standard. It seeks to introduce a council that will select magisterial candidates before they are appointed by the Grand Duke (European Commission, 2021[35]). Legal protection for whistle-blowers was strengthened with the transposition of the European Whistle-blowers Act. The framework to govern conflicts of interest could be strengthened through extending the current revolving doors policy beyond members of government (European Commission, 2021[35]) and the disclosure of assets and gifts (GRECO, 2020[36]).

Figure 1.11. Perceptions of corruption are low

Note: Panel B shows the point estimate and the margin of error. Panel D shows sector-based subcomponents of the “Control of Corruption” indicator by the Varieties of Democracy Project.

Source: Panel A: Transparency International; Panels B & C: World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators; Panel D: Varieties of Democracy Project, V-Dem Dataset v12.

Fiscal policy should be used to tackle long-term challenges

Significant fiscal policy support has been provided, but debt remains low

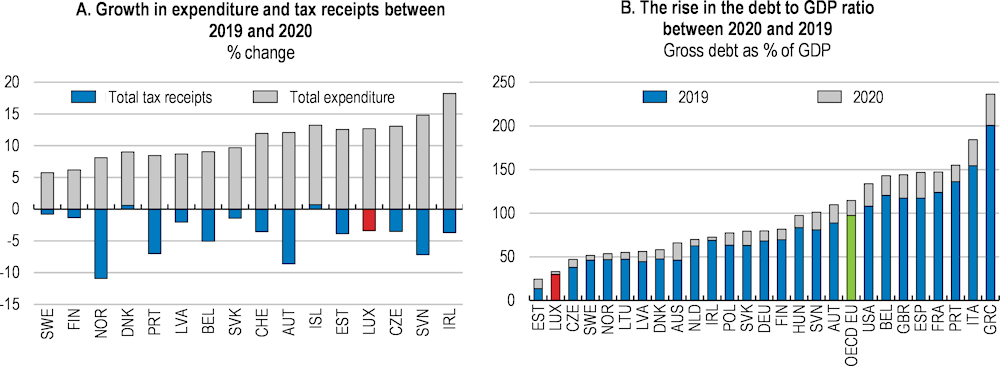

Policy support during the coronavirus crisis was substantial, mainly thanks to a sharp increase in spending (Figure 1.12, panel A). Nonetheless, the rise in total debt was markedly less than in most OECD peers (Figure 1.12, panel B) and well below the 8.5 percentage points increase in debt following the global financial crisis. This is mainly due to the resilience of tax revenues and economic growth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The impact of the war in Ukraine accounts for most of the increase in support in 2022, offsetting the withdrawal of COVID-19 related measures. The budget deficit, according to the government’s latest estimates (Ministère des Finances, 2022[37]), will gradually return to balance by 2026. In the context of rising but still very low real interest rates, tight labour markets and rising inflation, fiscal policy support should be highly targeted to the most vulnerable, to avoid contributing to cyclical inflationary pressures.

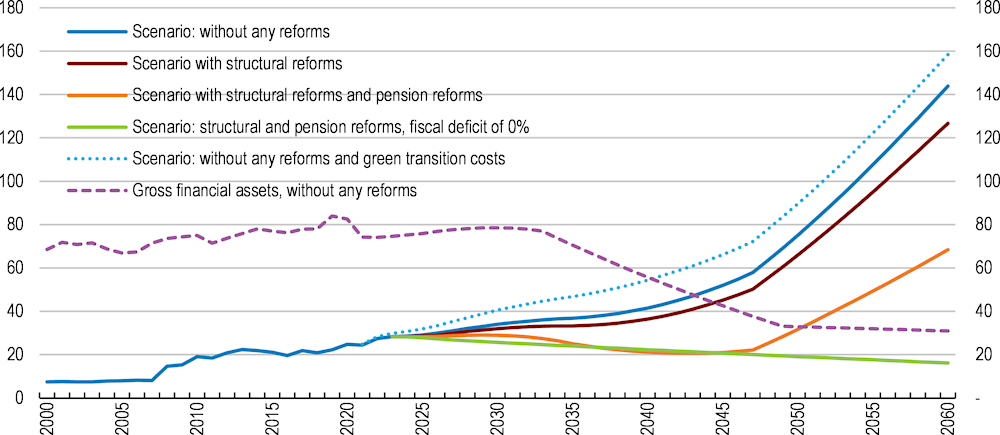

Figure 1.12. Debt levels remained contained despite a strong policy response to the COVID-19 crisis

The largest risk to the long-run debt outlook remains pension spending. Luxembourg’s very low current levels of gross debt as well as sizeable public assets will provide an important buffer. Total public assets stand at over 80% of GDP, reflecting both large numbers of state-owned companies in key utilities, as well as sizable holdings in certain private companies. Over the longer term, however, spending pressures related to ageing will reduce fiscal flexibility in the face of shocks (Figure 1.13). The draw-down of pension assets between 2030 and 2050 will help to offset rising pension costs, but once these assets are sold, pension liabilities are projected to rise steeply in the absence of meaningful pension reform.

Even a significantly higher rate of growth would require difficult fiscal choices to keep pension liabilities in check. The recent report assessing the pensions system showed employment growth of 2.7% is required alongside a reduction of an adjustment to real wages of benefits, in order for the system to be sustainable over the long term (IGSS, 2022[38]). STATEC’s 3% long-term growth scenario (Haas and Peltier, 2017[39]) projects employment growth of 0.7% per annum, with 50% of the workforce as cross-border workers. Employment growth of nearly 3% would imply a substantial increase in growth and demand for housing, transport, and energy, which would further compound the challenges of the green transition. Therefore, pension system reform is crucial for economic resilience.

Figure 1.13. Ageing is the largest long-term fiscal risk and cannot be solved with growth alone

Gross public debt, Maastricht definition, % of GDP

Note: The scenario with no ageing related reforms includes the impact of projected rising net public pensions, long-term care and health costs, consistent with European Commission estimates, which add 8.6 percentage points of GDP to annual government spending in 2060. The drawing down on pension fund reserves from 2027, reflected by the decline in gross financial assets, helps fund pension spending increases until the late 2040s, when pension reserves reach zero. Non-pensions gross financial assets grow at 0.61% per annum throughout the forecast, the average annual return over 2000-20. Pensions reforms including raising contribution rates, raising early retirement to 62 years, linking retirement to life expectancy, increasing migration by 33% and raising the employment rate of older workers by 10 percentage points. The structural reforms scenario assumes real GDP growth is 1 percentage point higher each year compared to the baseline due to structural reform implementation. The costs of the green transition are based on achieving a range of targets set by the government. This list is non-exhaustive and subject to significant uncertainty, including the pace of the transition and the costs of financing, and do not include any revenue effects from the transition.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2021) Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and Long-term baseline projections; (European Commission, 2021[8])

The challenges of the green transition will also need to be accommodated. The government has already undertaken a number of measures to encourage greater energy efficiency, including in response to the energy crisis. Direct investments and subsidies to support the green transition investments will require sustained spending commitments, in addition to private investment. The rate at which spending rises will vary according to the price of carbon, the generosity of subsidies as well as take-up rates. Forecasting the direction of revenues from the transition is less certain. The potential revenue gains or losses from a carbon tax, and how they might be used, will depend on various factors, including the chosen level of carbon tax and how neighbouring countries’ fuel pricing will evolve (see Chapter 2). Table 1.7 highlights potential net fiscal implications of the green transition at -0.35% of GDP annually over the medium term. The uncertainty of this estimate increases over the long term, as levels of uptake on subsidies and infrastructure spending plans evolve.

The green transition could also have significant growth implications for Luxembourg. Chapter 2 presents a modelling exercise which suggests the economic impact of a rising carbon tax on the economy would be slightly positive if carbon tax revenues were positive and redistributed. However, there are also downside risks – for example, a disorderly global green transition could have knock-on effects on the Luxembourgish economy, substantially lowering long-term growth. Given the uncertainty of the green transition’s fiscal impact, integrating it into the budget framework would allow for a holistic approach to public debates regarding other long-term spending commitments such as pensions. Chapter 2 recommends enhancements to the fiscal framework to take these considerations into account.

Box 1.1. Quantification of the structural reforms recommended in this Survey

This box shows the results of quantifying the effect of some of the structural reform measures proposed for Luxembourg in this Survey, based on an OECD quantification framework (Égert and Gal, 2017[40]; Guillemette and Turner, 2021[10]). The effects are derived from a series of reduced-form regressions on a sample of OECD countries (in some samples, non-OECD countries are included as well). The estimated results are allowed to vary across countries because of differences in factor shares, the level of employment by age group, and a country’s demographic composition. The approach is meant to serve as an illustration of a potential impact of reform and is not a projection. Therefore, it should be treated with care.

Additional positive effects could be expected from other recommendations, notably to reduce friction in the labour market and improvements to the business environment, but these are harder to quantify. Examples include a reform to the insolvency regime, streamlining of the administrative burden for firms and broader measures to reduce financial risks (which would have the effect of reducing the frequency and severity of financial crises, and therefore the associated economic risks).

Table 1.5. Illustrative impact of structural reforms on GDP per capita

Effect on GDP per capita levels*

|

|

5-year effect |

10-year effect |

|---|---|---|

|

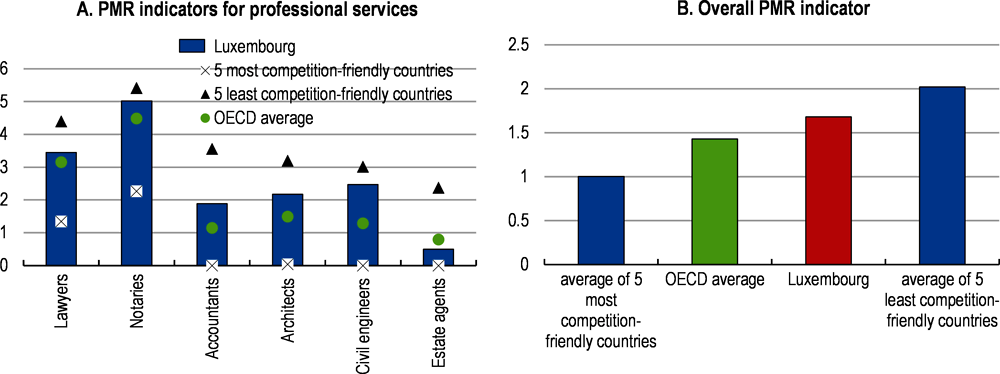

Product market regulation (PMR) |

|

|

|

Make professional regulations less restrictive |

0.6% |

0.9% |

|

Labour market policies |

||

|

Improve active labour market policies, such as training** |

0.4% |

0.5% |

|

Capital deepening |

||

|

Increase R&D spending by firms through encouraging matching |

0.5% |

1.1% |

|

Pension reform |

||

|

Increase the retirement age by 2 years over 5 years |

0.3% |

0.4% |

|

Total increase in GDP per capita |

1.8% |

2.9% |

Note: Calculations are based on (1) a reduction in the OECD Product Market Regulations sub-indicator of professional services regulations to the average of the best-performing (i.e. less restrictive) OECD countries, which corresponds to lowering the overall PMR indicator from 1.68 to 1.33; (2) increasing ALMP spending as a share of GDP by 0.1pps of GDP to approach the top-third of OECD countries (from 0.75% of GDP to 0.80% of GDP); which corresponds to increase spending per unemployed as a ratio of GDP per capita from 27% to 30%; (3) increasing capital deepening by increasing business spending on R&D from 54% of total spending to 62% (against an OECD average of 64%); and (4), increase the legal retirement age by 2 years, gradually phased in over a five-year period, with policies to limit early retirement. * Projected increases in GDP per capital levels. ** Improving ALMP increases multifactor productivity as well as the employment rate, both of which will lift GDP per capita over time.

Source: OECD calculations based on (Égert and Gal, 2017[40]).

Table 1.6. Growth impact of pension reform

Expected growth effect on the variables after increasing the effective retirement age by 2 years

|

5 years |

10 years |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Potential percentage point increase in the growth rate of GDP |

0.38 |

0.20 |

|

Employment rate, men and women |

2.0 |

3.33 |

Source: OECD calculations based on (Guillemette and Turner, 2021[41]).

The fiscal framework’s resilience to shocks can be increased

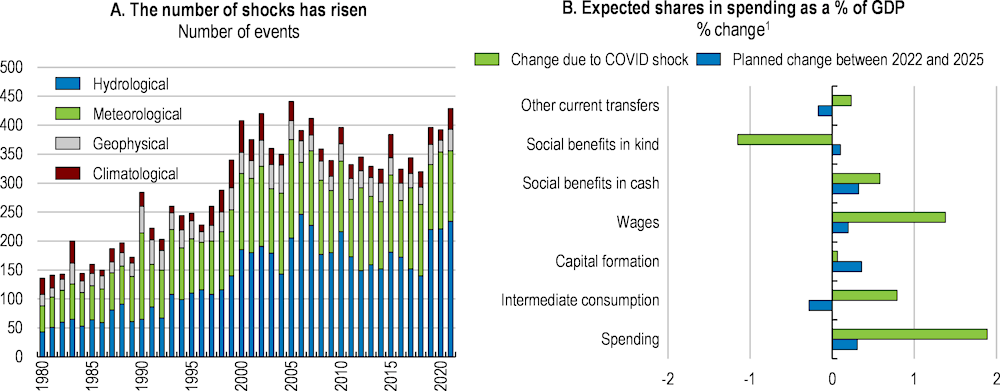

The fiscal framework could be enhanced to improve resilience in the face of more frequent shocks. Economies are exposed to a rising number of physical shocks (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2022[42]) (Figure 1.14), whilst the COVID-19 outbreak highlighted how interconnectedness increases the likelihood of pandemics (Marani et al., 2021[43]); (Smith et al., 2014[44]). Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has ushered in a period of heightened geopolitical uncertainty. At the same time, expectations have risen that policy makers can and should play a significant role in absorbing these shocks, acting as a lender of last resort and protecting the most vulnerable (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2021[45]).

Having a range of policy tools in place contributes to resilience. Automatic stabilisers and fiscal rules are crucial to allow governments to respond quickly to crises (Orszag, Rubin and Stiglitz, 2021[46]). Luxembourg’s low level of public debt is its principal fiscal shock absorber, and the government has committed to keeping public debt levels below 30% of GDP. The size of the automatic stabilisers, which are important to absorb immediate shock impacts, are estimated to be in line with that in peers (Maravalle and Rawdanowicz, 2020[47]) or slightly larger (Bouabdallah et al., 2020[48]). Discretionary spending policies are necessary when the impact of the shock is expected to be persistent (Bouabdallah et al., 2020[48]). If the shock is permanent, automatic stabilisers may no longer work as effectively as before because the structure of the economy has changed. In addition, specific policies may be required to address fundamental shifts in behaviour or prices that are not affected by existing automatic stabilisers. In this instance, governments should prioritise high-impact programmes for long-term resilience (OECD, 2021[49]).

The identification of high-impact policies can be difficult. In Luxembourg as elsewhere, evaluation of the impact of policy choices has been insufficient – for example, spending reviews have not been used since they were applied to achieve significant budget cuts in 2014. Budget documentation does not systematically reference performance information or evaluations. Even though periodic ex-post evaluations of regulations have been undertaken in Luxembourg, they are not a consistently applied tool (OECD, 2021[50]). The OECD and the European Commission (OECD and European Commission, 2020[51]) noted that a missing culture of evidence-based policy making may result in insufficient investments in human and financial resources to adequately draw on administrative data in the development of policies.

An evaluation framework, including a clear methodology, could help to ensure that regulations remain fit for purpose – and that associated spending is appropriate. A system to link rigorous policy evaluation directly to the budget allocation process would significantly improve the capacity of the fiscal framework to respond to shocks and their aftermath. A large crisis can have a lasting impact on the composition of spending that outweighs the impact of traditional budget planning choices (Figure 1.14, panel B). Greater input from the independent fiscal institution on the quality of spending and its overall growth impact could stimulate greater debate on policy choices, if its mandate were expanded.

Advances in information technology could be used more proactively in Luxembourg to support a performance-oriented budget (see Box 1.3). Notably, a clear policy commitment to open and transparent data evaluation should help motivate additional funding. Anonymised social security data are already provided to public researchers via the Luxembourg Microdata Platform on Labour and Social Protection and were a valuable source of information for understanding the impact of COVID-19. Luxembourg’s high quality administrative data could be anonymised and made available to the broader research community. Digitised tax data could allow for more granular impact evaluations. The project to evaluate COVID-19 policy responses (OCDE, 2022[10]) has linked firm-level and administrative data, which can be used to monitor on an ongoing basis where policy support is being directed. Including additional policy measures will develop a credible evidence base, which can be used to inform the design of spending programmes further into the future.

Figure 1.14. Shocks are becoming more frequent – and can have a lasting impact on spending choices

1. Change in spending from the COVID-19 shock is calculated as the difference between the 2022 and 2019 budget projections for 2022 spending. Despite the relatively small changes, the projected increases for investment spending and social spending are sizable, as per OECD and EC recommendations to provide ongoing social support from the crisis. Investment spending will grow 6.5% a year, reaching 4.7% of GDP by 2025.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Emergency Events Database (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2022[42]); and Ministère des Finances (2021, 2018).

Box 1.2. Estimated fiscal impact of reform

The table illustrates the potential impact on the fiscal balance of implementing some of the reforms proposed in this study. The estimates are meant to show the potential direction of change and to provide an indication of magnitude. Actual results may differ, and the estimates below are merely illustrative.

Table 1.7. Fiscal implications of reform

Medium-term expected annual change as a % share of GDP

|

Measure |

Medium term fiscal impact (savings (+)/costs (-)) % of GDP |

|---|---|

|

Carbon tax1 |

-0.1% |

|

Road use charges2 |

+0.2% |

|

Support communities which densify and go green by significantly expanding the density bonus to EUR 25k per home3 |

-0.3% |

|

Increased provisioning for infrastructure investments4 |

-0.15% |

|

Property tax5 |

+0.4% |

|

Pensions savings6 |

+0.7% |

|

Direct income support for households most vulnerable to price increases7 |

-0.11% |

|

ALMP training8 |

-0.1% |

|

Total |

+0.5% |

|

Of which: Green policies |

-0.35% |

Notes: 1. STATEC near-term estimates for an increase in carbon tax to EUR 30 per tonne by 2023. Preliminary modelling estimates that consider the direct impact of the carbon tax on revenue suggest a 0.05% decline in revenue in 2025, assuming a carbon tax of EUR 50 per tonne by that time. Over the longer term, revenue receipts are expected to rise (see chapter 2, Box 2.3 for more details). 2. Based on surcharge of 5 cents per km and 20% reduction in car use for travel. Only work-related travel included. 3. Assumes 8 400 homes a year renovated receiving EUR 25 000 a home. 4. Increased infrastructure provisioning to cover the cost of higher maintenance and potential upgrades to e.g. hydrogen fuelling. 5. Assumes current municipal tax rates apply to 8% of the existing residential buildings and 1 115 hectares of vacant land. 6. Most pension gains accrue later (see Table 1.5 and Table 1.6). 7. Assumes poorest 40% of households receive the equivalent of a 2.5% wage increase every 15 months. 8. Increase total ALMP spending towards the top 10 OECD performers.

Source: OECD calculations.

Box 1.3. Key elements to consider in designing a more performance-oriented budget framework

A strategic link with the budget. In Chile, the budget law requires evaluations to be considered in the budget process, whilst in Canada, ministries are encouraged to present evidence from evaluations as part of their budget submissions.

A prioritised and planned process. Continuous evaluation should give priority to high value, high risk and politically important programmes. Rather than a fixed schedule, Canada’s policy for results prioritises evaluations based on a schedule of risk and other considerations. In the Netherlands, performance information is only selectively presented in the budget, which has increased its relevance. Clarity about the schedule of evaluations also helps stakeholders to prepare for engagements - which is a practice rarely implemented in Luxembourg.

Supporting co-operation alongside accountability. Policy evaluation can become a tick-box exercise, when strategy is sacrificed for completeness; it can also become a compliance tool rather than an instrument for identifying the best tools to use. In Canada, line ministries are responsible for prioritising and undertaking the evaluation of programmes and individual projects. All findings must be made public, and ministries must also explain why they are not evaluating certain programmes. The Treasury Board may also independently evaluate programmes. In the Netherlands, the budget system’s performance metrics have been decoupled from the audit process.

An evolutionary approach. The implementation of an evaluation framework involves multiple stakeholders and takes time to implement successfully. In the Netherlands, the performance budgeting system has been evolving since 2008. In addition, generally, evaluations require time for data collection and for policies to impact policy. Australia conducts post-implementation reviews two to five years after policy implementation.

Administrative datasets in the public sector offer a significant opportunity for policy impact assessments, particularly when combined across sources. Tapping this potential requires a strong commitment to preserve confidentiality and anonymity, a well-documented and understood process for combining and analysing administrative datasets, and a secure way of sharing information with external researchers and institutions. In Luxembourg, the General Inspectorate for Social Security has developed state-of-the-art protocols for sharing anonymised social security data, in line with the general data protection regulation, which could be used for other administrative datasets. A single entity responsible for pooling administrative data together is a significant benefit. In Norway, Statistics Norway matches numerous administrative datasets and provides this anonymised and encrypted data to external institutions and researchers.

In Luxembourg, a pilot programme focused on a limited set of policy goals, such as understanding the impact of policies on the green transition (see chapter 2) or on well-being, could be applied to a small set of high-impact, high-value policy programmes as a mechanism to develop the system in practice.

Source: (Barth, 2012[52]); (Budding, Faber and Vosselman, 2019[53]); (de Jong, 2016[54]); (OECD and European Commission, 2020[51]); (OECD, 2018[55]); (OECD, 2020[56]); (OECD, 2021[50]).

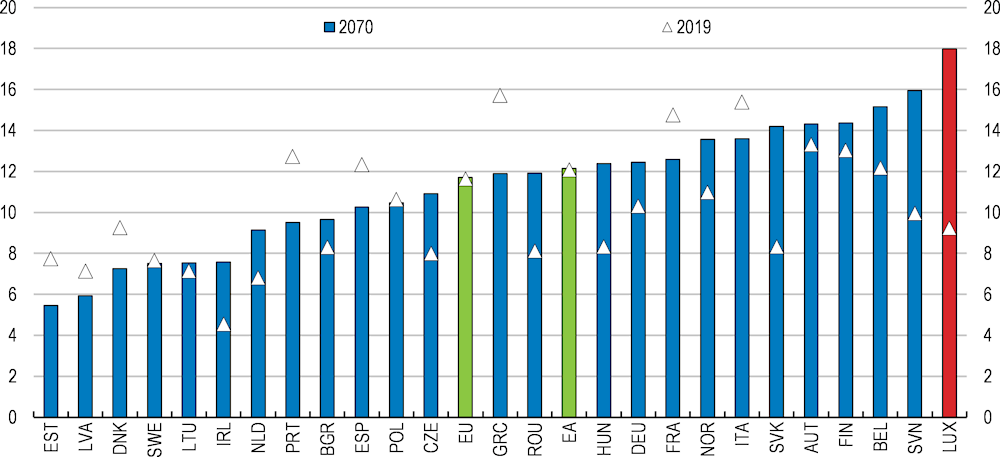

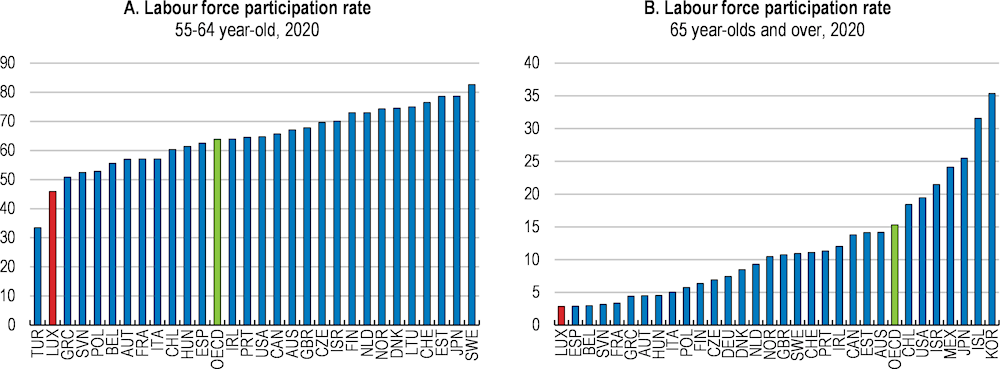

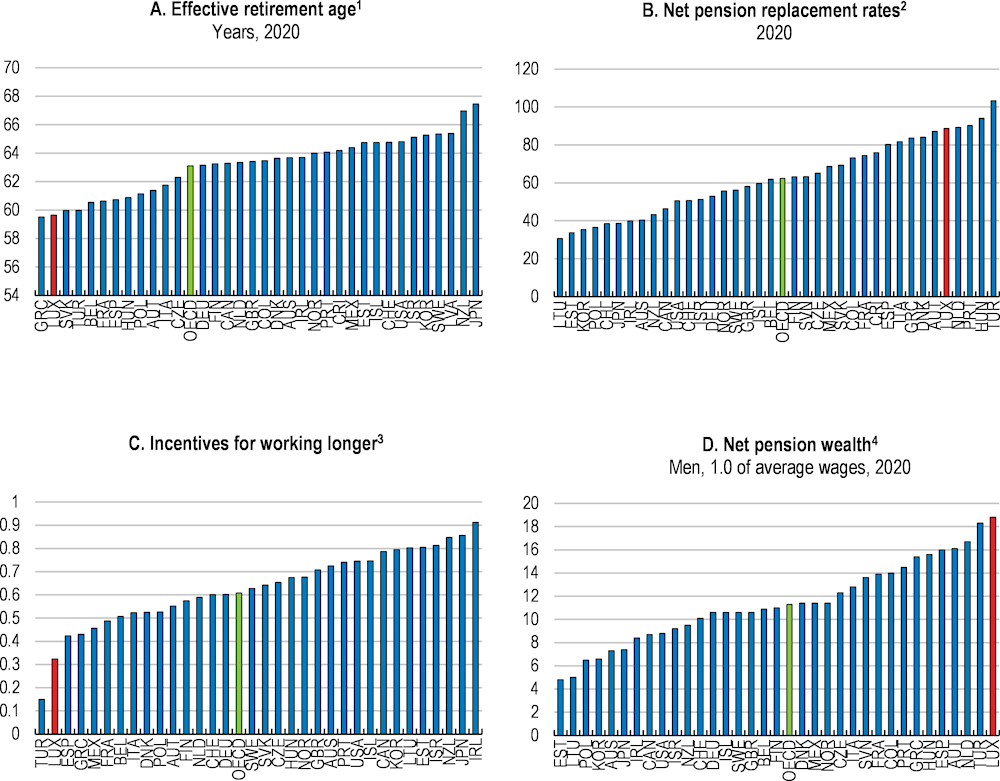

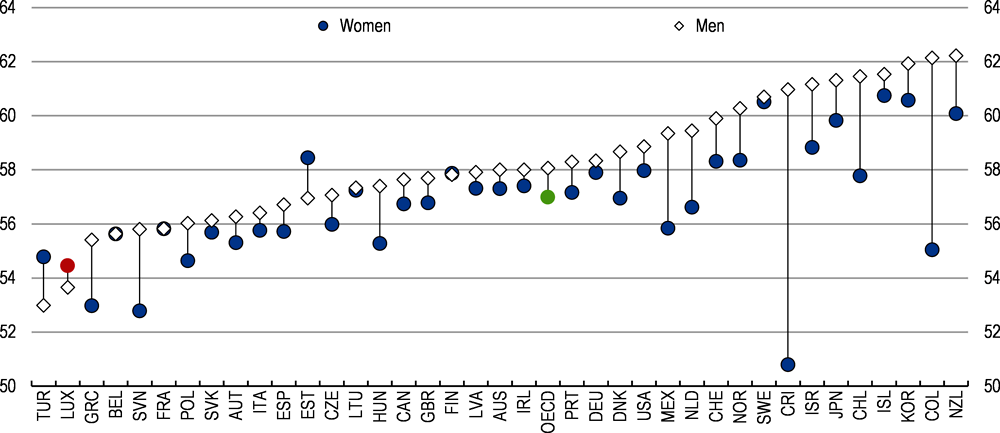

Ageing costs from pensions are the largest long-term fiscal liability

OECD projections indicate that pension and health expenditure will increase fiscal pressure significantly by 2060 (Guillemette and Turner, 2021[41]). European Commission projections show a similar trend, with total age-related expenditure projected to rise from 16.9% of GDP in 2019 to 27.3% of GDP in 2070, with the bulk of the increase due to old-age pensions (European Commission, 2021[8]). By 2070, the European Commission projects pension expenditures alone to rise to 18% of GDP, the steepest increase in the European Union (Figure 1.15) (European Commission, 2021[8]), as the old-age dependency ratio will more than double by 2070 (Table 1.8). Domestic projections point to a more contained, but still high, increase in pension expenditure to 14.5% of GDP, based on more favourable assumptions on employment and economic growth related to cross-border workers and levels of immigration (IGSS, 2021[57]).

Reform of the pension system is needed to ensure financial sustainability

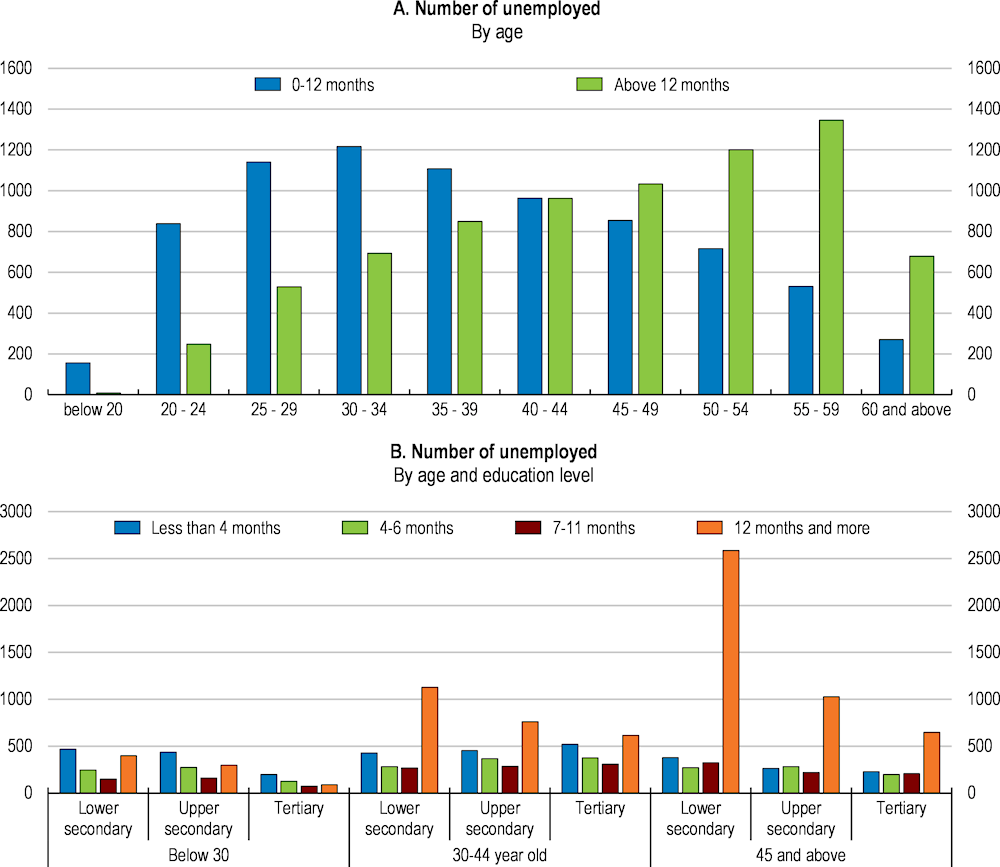

The government has undertaken the ten-year review of the sustainability of the pension system foreseen in the 2012 pension reform (see Box 1.4) to assess whether the current total contribution rate of 24% should be revised for the next ten-year coverage period 2023-2032 (IGSS, 2021[57]). An interim review in 2016 recommended no changes. The review provides an important opportunity for new reforms to ensure the pension system’s financial sustainability whilst having positive impacts on the labour market. In the near term, the pension system enjoys a surplus of contributions over outlays, thanks to favourable labour market dynamics (IGSS, 2022[38]). Surpluses are accumulated in the pension reserve fund (Fonds de Compensation) which stood at 37% of GDP by end-2020 (OECD, 2019[25]; IGSS, 2021[57]; European Commission, 2021[4]). But, if no changes are proposed, simulations indicate the system will move into deficit in the early 2030s, and the authorities will start using the pension reserve fund to make up for shortfalls; the reserve would be depleted in the late 2040s (IGSS, 2022[38]). Therefore, the authorities should explore all possible options, in consultation with social partners, to ensure the affordability of the pension system and enhance intergenerational equity.

Since the 2012 reform, a deficit in the ‘prime de répartition pure’-indicator, which measures the theoretical contribution rate needed to cover the system’s current expenditure, is expected to trigger a semi-automatic stabiliser: a reduction of the indexation of pensions to real-wage developments. However, this stabilisation mechanism will be insufficient to prevent the deficit from widening, in part because the large cohorts who moved to Luxembourg during the great economic expansion in the late 1980s and 1990s are set to start retiring from the early-to-mid 2020s boosting pension expenditure (IGSS, 2022[38]). Rather than waiting for the system to tip into deficit, corrective measures should be implemented sooner rather than later. For instance, the indexation of pensions to real wages could be put on hold until replacement rates reach more sustainable levels, whilst ensuring protection of the most vulnerable pensioners.

By delaying action, the size of any future adjustments is likely to be larger, implying that a heavier burden of the adjustment would fall on the contribution rate. Current estimates point to the contribution rate needing to increase to between 31% and 35% by 2070 from 24% currently, under the assumption of no change in policy (IGSS, 2022[38]). This in turn would strongly raise the tax wedge on labour, penalising lower-income and younger workers.

Box 1.4. Overview of Luxembourg's pension system

Luxembourg's general pension system is a mandatory, pay-as-you-go system, with defined benefits. The contribution rate is 24% of gross salary, paid in equal shares by employers, employees, and the state. Occupational pension schemes are a very small part of the total. Since 2019, they have been open to the self-employed. Fewer than 4% of workers have a private pension. There is a separate scheme for public employees.

The statutory retirement age is 65 years for men and women. Early retirement is possible at 57 if an individual has 40 contributory years, and from 60 onwards with 40 contributory and qualifying non-contributory years (e.g., study, or some unemployment), with at least 10 years of paid contributions.

The pension benefit is the sum of four components:

an income-related part with an annual accrual rate.

an incremental increase to the income-related part adjusted for years worked and one's age.

a lump-sum, which depends on the number of years of insurance.

an end-of-year allowance bonus. The end-of-year bonus (EUR 869.4 per year as of 1 April 2022) is paid only as long as the system is not in deficit.

Benefits are adjusted both for inflation, as part of the general inflation indexation of all wages and benefits, and for real-wage growth.

Rising concern of the financial sustainability of the system led to a reform in December 2012. The reform mainly changed the parameters of the pension benefit formula in order to incentivise people to work longer. It has a transition period of 40 years (2013-52) and left the retirement age unchanged.

Under the reform, the lump-sum benefit gradually rises (from 23.5% of the social reference income in 2012 to 28% in 2052), while the accruals rate is gradually reduced from 1.85% in 2012 to 1.6% in 2052. The age-related element increases gradually so that the sum of pension age and career years will have to be higher than 100 years in 2052 instead of 93 years in 2012 in order to obtain an increase in the accrual rate. For an individual entering the labour market at 22, this would kick in after 36 years working.

The 2012 reform added mandatory ten-year reviews of the system, as well as some stabilisers. In addition to the readjustment mechanism for real wages, the reserves accumulated in the pension fund must be at least 1.5 times the yearly pension expenditures. In 2020, Luxembourg’s pension reserves were around 4.8 times annual pension expenditure (some 37% of GDP).

The 2012 pension reform was a step in the right direction but still not enough to guarantee long-term sustainability. A number of more radical proposals, such as fully eliminating real-wage indexation, or a faster decrease of the accruals rate, were not passed, but should continue to be considered. By 2021, the projected rate of increase of pension expenditure by 2070 was still the highest anywhere in the European Union.

Moving to a fully-funded system, with defined contributions, as in Denmark or in the United Kingdom was debated in the 2000s. Such a switch would imply that current cohorts would continue to contribute to the pay-as-you-go system while also needing to contribute to their own pensions, raising the question of intergenerational fairness. These high costs would require substantial socio-economic reforms to be socially acceptable, as occurred in Denmark. As witnessed in countries that have successfully carried out pension reform, it requires a high degree of social consensus about the need and direction for reform to put pension schemes on a firmer footing and ensure that the new system is stable and sustainable. The search for consensus can lead to the watering down of required changes and it may be necessary to phase-in some reforms as those close to retirement have less time to adjust their situation to the new system. However, slow transition implies that the eventual adjustment will be somewhat more costly and carries the risk that reforms may be reversed.

Table 1.8. Ageing-related spending is projected to increase substantially

As a percentage of GDP unless otherwise indicated

|

|

2019 |

2025 |

2030 |

2040 |

2050 |

2060 |

2070 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public pensions expenditure, gross1 |

9.2 |

10.3 |

11.4 |

13.0 |

14.8 |

16.7 |

18.0 |

|

of which: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Old-age and early pensions |

7.0 |

7.9 |

8.8 |

10.2 |

11.8 |

13.5 |

14.8 |

|

Disability pensions |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

Survivors pensions |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

|

Projected spending on health care2 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

4.1 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

4.6 |

|

Long-term care spending2 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

|

Total ageing-related spending |

16.9 |

17.7 |

18.8 |

20.8 |

23.2 |

25.6 |

27.3 |

|

Old-age dependency ratio (20-64) |

22.6 |

25.6 |

29.6 |

37.8 |

45.5 |

52.8 |

56.1 |

|

Life expectancy at 653 |

19.1 |

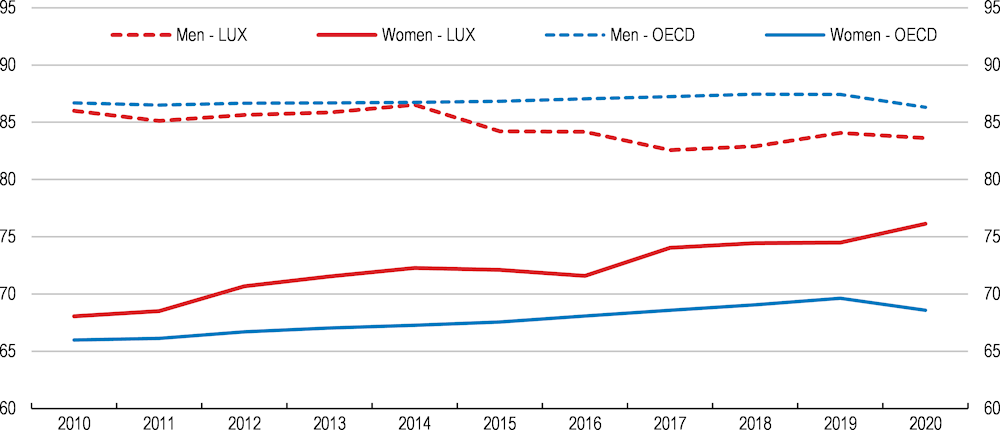

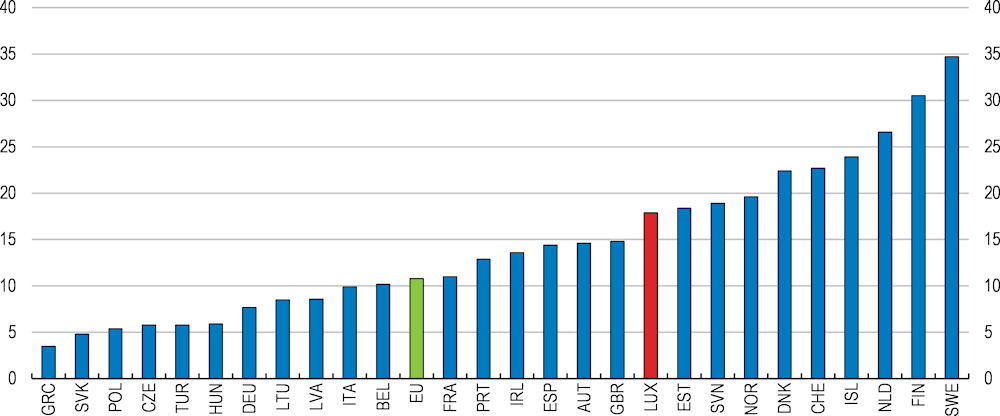

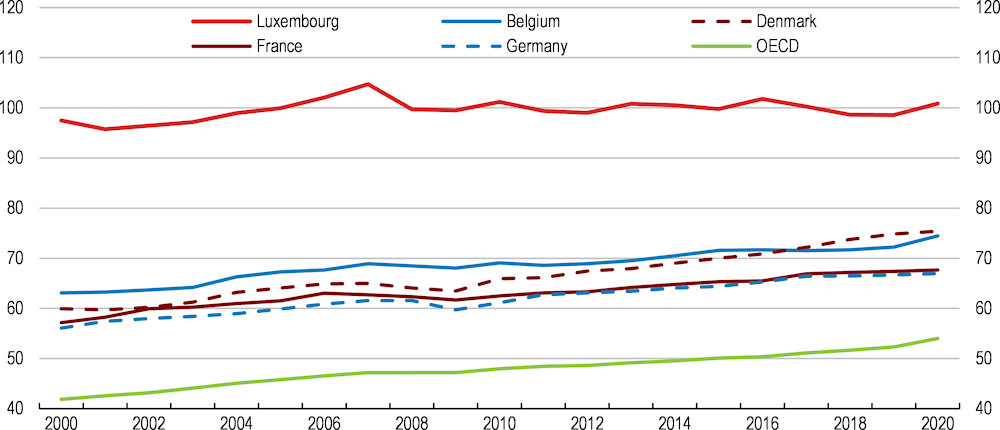

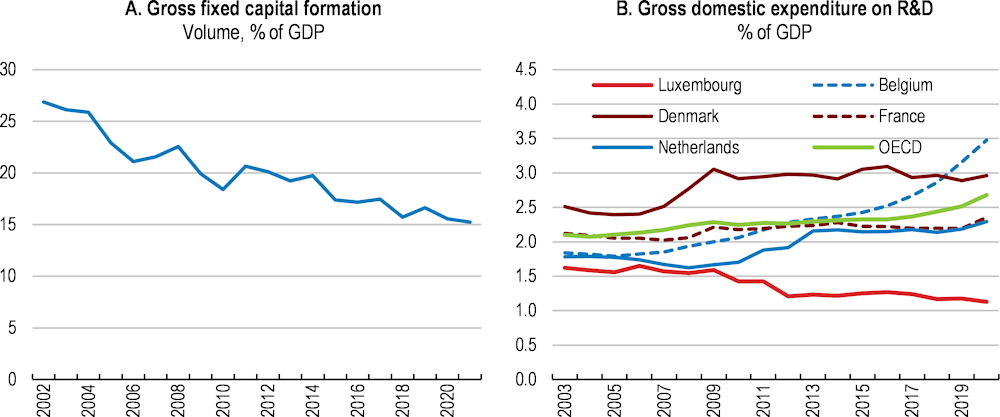

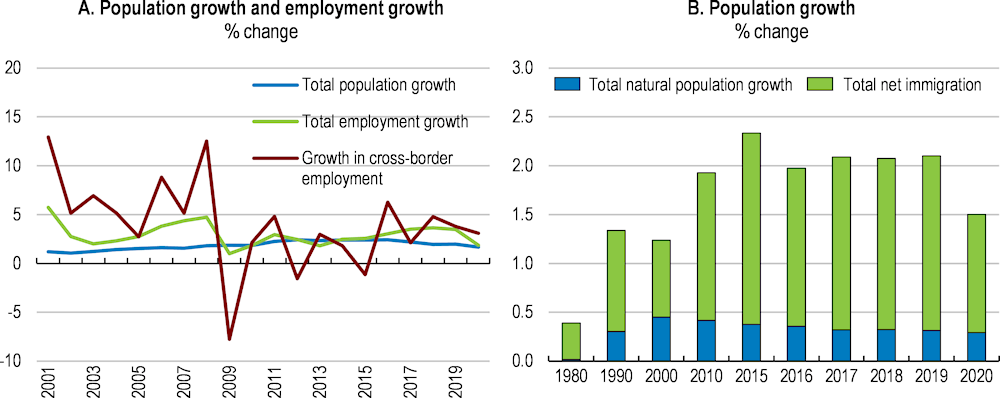

19.6 |