Naomitsu Yashiro

OECD

David Carey

OECD

Axel Purwin

OECD

Naomitsu Yashiro

OECD

David Carey

OECD

Axel Purwin

OECD

Effective use of digital technologies enables New Zealanders to participate in society in a more inclusive way, firms to boost productivity and better integrate into the global economy, and the government to offer better services. New Zealand’s digital sector and digital innovation have much room for growth. Diffusion of digital technologies and investment in intangible capital that maximises the potential of these technologies could be enhanced by addressing structural bottlenecks. There are severe shortages of specialised ICT skills owing to COVID-19-related border restrictions and a weak domestic pipeline of these skills that partly results from school students’ poor mathematics achievement. Some regulations have not kept pace with technological change and risk constraining digital innovation while failing to prevent harmful activities. More intensive use of digital tools is also held back by low availability of high-speed Internet connections in rural areas and a lack of financial support for small businesses. Weak coordination between export promotion and innovation support prevents young firms investing in digital innovation from reaping high returns through exporting. New Zealand should rigorously implement its new national digitalisation strategy so that government agencies and social partners can advance digital transformation.

Digital technologies have transformed the economy and social interactions in recent decades, with the COVID-19 pandemic accelerating this trend. Digital technologies have considerable potential to boost productivity growth and improve wellbeing. For instance, a wider use of online platforms lowers transaction costs by matching sellers and buyers more efficiently and reducing information asymmetries. Big Data analysis and Artificial Intelligence enhance innovation by helping firms to exploit large and timely data in their R&D activities or introduce novel digital solutions to reduce costs and improve efficiency (OECD, 2020[1]). Digitally-enabled innovations often exert strong economies of scale as they can be replicated with little additional cost (Brynjolfsson et al., 2008[2]). Despite the ongoing digital transformation, many OECD countries, including New Zealand, are struggling with low productivity growth. This is partly because economic statistics do not capture fully the benefits of digital technologies, not least when digital services are provided for free. But a more import reason is that diffusion of digital technologies is still underway and is not fast and broad enough to significantly raise productivity growth (Brynjolfsson, Rock and Syverson, 2021[3]).

Historically, general-purpose technologies have generated significant productivity gains only after a long time lag, and might even have contributed to a productivity slowdown in the short run as resources have had to be diverted for adoption and learning (Hornstein and Krusell, 1996[4]). Countries need to accumulate intangible capital that complements digital technologies, such as new work organisation, digital and managerial skills and valuable (big) data (Brynjolfsson, Rock and Syverson, 2021[3]; Corrado et al., 2021[5]).Investment in such intangible capital is costly and time consuming, as well as risky, involving substantial trial-and-error. It requires good access to a skilled workforce and risk capital, as well as flexible and competitive regulatory settings that encourage digital innovation. Availability of high-quality digital infrastructure, like ultra-fast broadband, also underpins faster diffusion of advanced, data-intensive digital technologies (Sorbe et al., 2019[6]; OECD, 2021[7]).

The effective use of digital technologies and data would enable New Zealanders to participate in society in a more inclusive way, firms to boost productivity and exports and the government to offer better services. However, reaping these benefits requires seizing the opportunities digital technologies bring, judicious investment in digital technologies and infrastructure, as well as better risk management against heightened digital security threats, and strong trust in digital environments (OECD, 2019[8]). Social institutions including laws, regulations, education and innovation policies will need to adjust while ensuring that all citizens enjoy access to good, affordable communication infrastructure, opportunities to acquire skills to thrive alongside the digital transformation of the workplace, and means to protect themselves against data theft and other harmful online activities.

In many OECD countries that underwent prolonged periods of lockdown, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the use of digital technologies among businesses, notably through changes in work arrangements and moving activities online (OECD, 2021[9]). The stringent lockdown in April 2020 raised awareness among New Zealand businesses of how effective use of digital tools can improve their performance. However, they may not have seized the opportunity to press ahead with the digital transformation as much as their peers in other OECD countries as economic activities reopened rapidly (Chapter 1). The next section assesses the diffusion of digital technologies in New Zealand from several angles including ICT industries, digital innovation and the use of digital tools by firms, households and the government. The following one discusses various policies to enhance the diffusion of digital technologies.

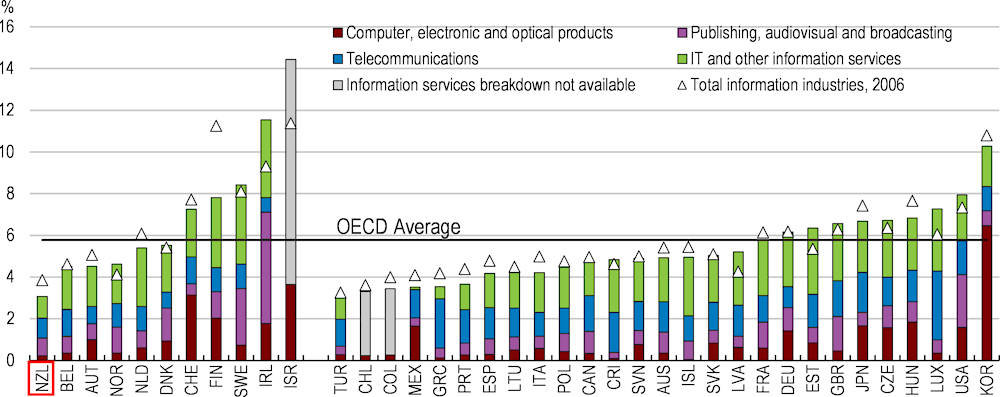

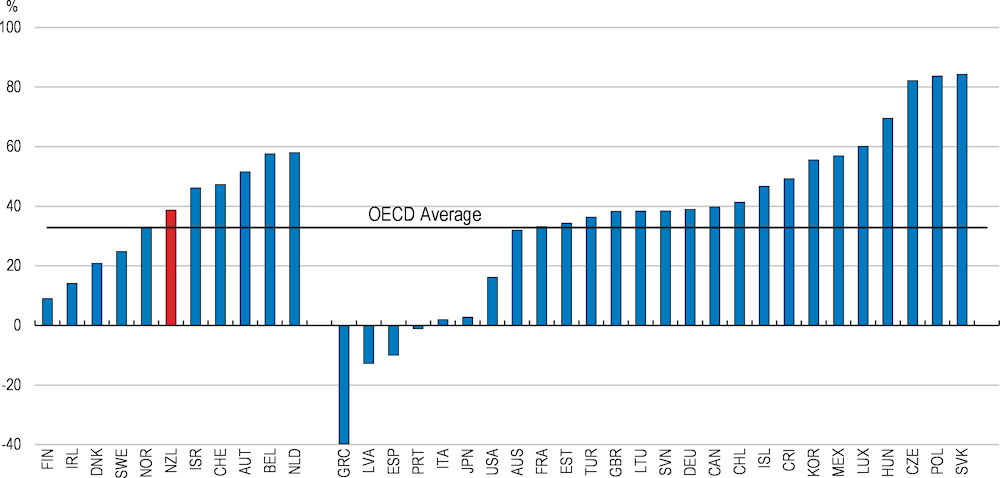

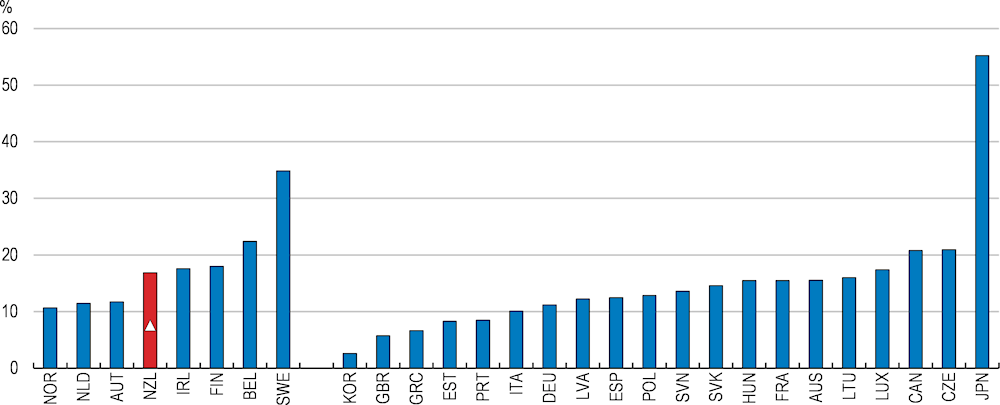

The digital sector, defined here as the ICT sector and digital services, is small in New Zealand by international comparison. For instance, value added shares of information industries (defined as the ICT sector plus the content and media sector) have decreased since 2006 and are among the smallest in the OECD (Figure 2.1). New Zealand especially stands out in comparison with other Small Advanced Economies (SAEs), which are defined in this chapter as the 11 OECD countries with populations between 1 million and 20 million and with per capita incomes above USD 30 000 (PPP exchange rates). This definition is in line with the one employed by the Productivity Commission (2021[10]) and Skilling (2020[11]), except that they also included two non-OECD economies (Singapore and Hong-Kong). This chapter compares New Zealand with other SAEs not only to control for their smaller domestic product and factor markets, but also to identify areas of digitalisation where New Zealand has substantial room to catch up to its peers through policy reforms.

1. Values for Colombia, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Turkey are for 2015 and values for Canada are for 2014.

2. Small advanced countries are defined as the OECD countries with populations of 1-20 million and with per capita incomes above USD 30 000.

Source: OECD (2021), STAN database, Inter-Country Input-Output database and national sources.

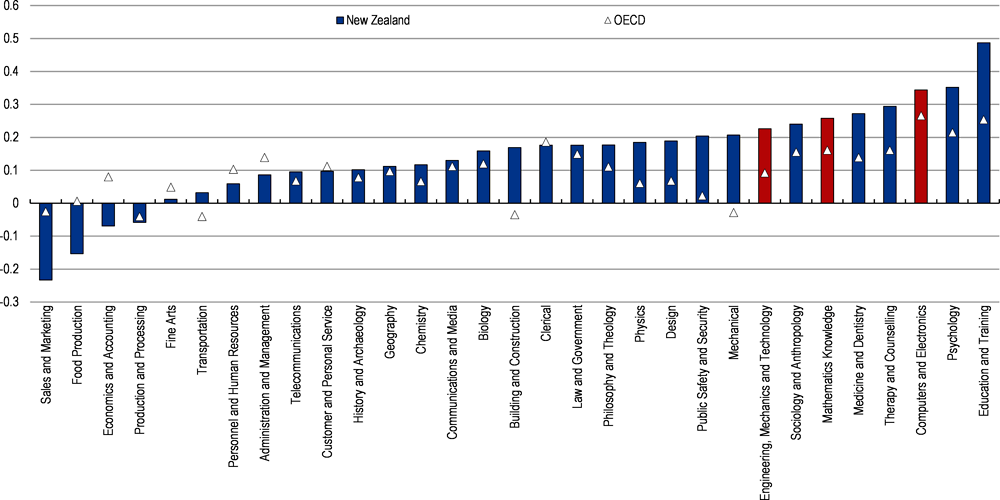

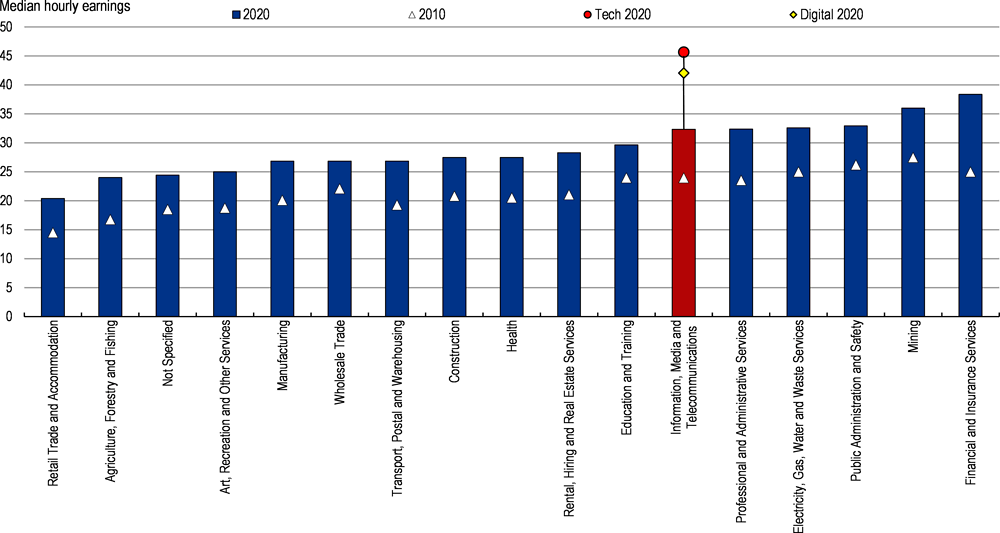

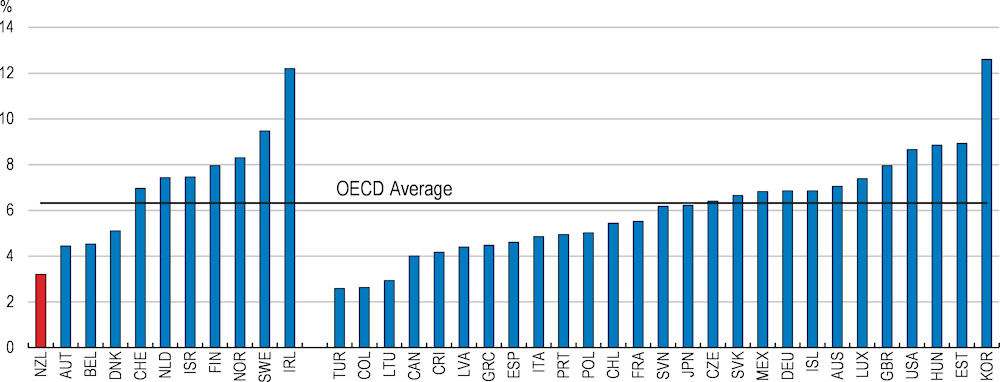

Productivity growth in the ICT sector outpaces that in other sectors (Figure 2.2), but its contribution to New Zealand’s aggregate productivity growth is muted by its small weight. Chronic shortages of ICT skills (Figure 2.3) have contributed to high wage levels in the digital sector (Figure 2.4). Firms in the ICT sector are by far the most advanced users of digital technologies, such as big data and cyber security technologies (OECD, 2020[1]). Innovation in the ICT sector exerts positive spillover effects on productivity in other industries, through backward and forward linkages (Han et al., 2011[12]). Industries that are more ICT intensive benefit most from such spillover effects, which materialise over time. While the weight of ICT intensive sectors in New Zealand is small compared with many other OECD countries (Figure 2.5, Box 2.1), it is growing, with their contribution to employment growth around the OECD average during 2006-16 (Figure 2.6).

Hourly labour productivity

Note: The OECD Skills for Jobs indicator captures skills shortages and surpluses. Positive values indicate skills shortages while negative values point to skills surpluses. The larger the absolute value, the larger the imbalance. Results are presented on a scale that ranges between -1 and +1. The maximum value reflects the strongest shortage observed across OECD countries and skills dimensions.

Source: OECD, Skills for Jobs (database).

Note: Data on wages for tech and digital jobs come from absolute IT. Tech jobs include roles such as software engineer, scrum master and data analyst. Digital jobs include roles such as web developer, SEO manager and digital marketing specialist.

Source: Stats NZ; Absolute IT (2021), Tech & Digital Remuneration Report, July 2021

1. The box shows the second to fourth quintile, the vertical line indicates the median and the whiskers show minimum and maximum values.

2. The OECD Digital government index assesses the adoption of digital technologies by public sector organisations. The index takes values from 0 (lowest digital maturity) to 1 (highest digital maturity). In this chart, index values have been multiplied by 100.

3. Not actual values, but relative ranking by OECD Going Digital.

Source: OECD (2021), Going Digital Toolkit

As a percentage of total absolute changes in employment in 2006-16

Note: Digital intensity is defined according to the taxonomy described in Calvino et al (2018). See the source for more details.

See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: Calvino et al. (2018), A taxonomy of digital intensive sectors, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2018/14.

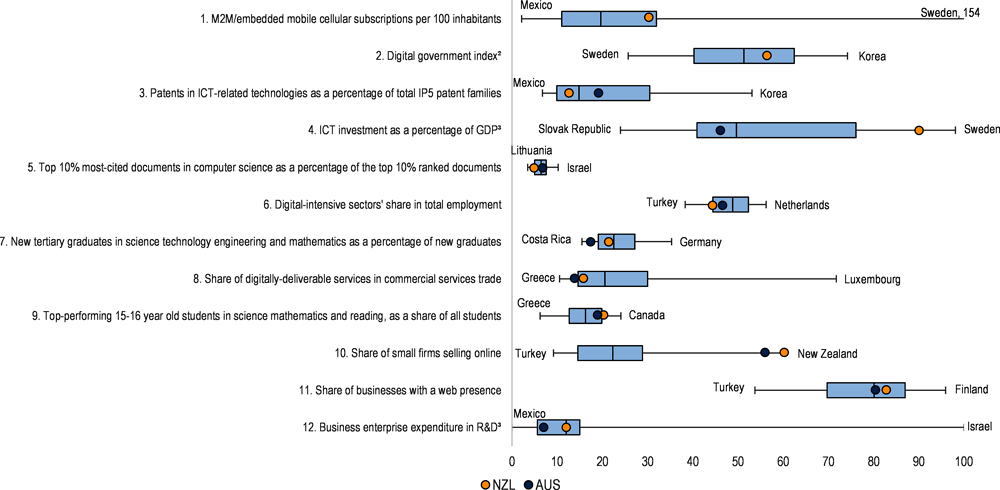

The OECD Going Digital Toolkit includes 42 key indicators for benchmarking OECD countries’ digital transformation. The indicators, capturing a wide range of aspects of a digital economy, are categorized into seven policy dimensions: Access, Use, Innovation, Jobs, Social, Trust and Market openness.

The Access dimension measures components that lay the foundation for the digital transformation, such as access to communication infrastructure, data and services. The Use dimension captures the extent to which digital technologies are actually used, for instance for selling and buying products online or interacting with authorities. The Innovation dimension gauges both how much resources are put into innovation and the actual output, in terms of academic research and start-up firms. The Jobs dimension captures the weight of the digital sector and the readiness of workers to thrive in a digital workplace. The Society dimension captures inclusiveness in the digital economy and society. The Trust dimension captures individuals’ and firms’ confidence in the digital environment. For instance, this dimension includes an indicator on the extent to which national health data may be shared with domestic and international stakeholders. The Market Openness dimension captures the weight of the digital sector in trade and the openness to trade and investment in digital services.

Many indicators in the Toolkit are missing for New Zealand, making it difficult to identify the aspects of its digital transformation that require the greatest attention (Table 2.1). Improving data should be a priority in the national digital strategy currently being developed (see below).

|

Dimension |

Indicator |

New Zealand data not available |

Underperforming the OECD average |

Outperforming the OECD average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Access |

Fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants |

Med. 1 quintile |

||

|

M2M (machine-to-machine) SIM cards per 100 inhabitants |

X |

|||

|

Mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants |

Med. 1 quintile |

|||

|

Share of households with broadband connections |

X2 |

|||

|

Share of the population covered by at least a 4G mobile network |

X |

|||

|

Broadband speed |

X |

|||

|

Disparity in broadband uptake between urban and rural households |

X |

|||

|

Use |

Internet users as a share of individuals |

X |

||

|

Share of individuals using the Internet to interact with public authorities |

X |

|||

|

Share of Internet users who have purchased online in the last 12 months |

X |

|||

|

Share of small businesses making e‑commerce sales in the last 12 months |

X |

|||

|

Share of businesses with a web presence |

X |

|||

|

Share of adults proficient at problem-solving in technology-rich environments |

X |

|||

|

Share of businesses purchasing cloud services |

X |

|||

|

Innovation |

ICT investment as a percentage of GDP |

X |

||

|

Share of start-up firms (up to 2 years old) in the business population |

X |

|||

|

Top 10% most-cited documents in computer science, as a percentage of the top 10% ranked documents |

X |

|||

|

Patents in ICT-related technologies, as a percentage of total IP5 patent families |

X |

|||

|

Business R&D expenditure in information industries as a percentage of GDP |

X |

|||

|

Venture capital investment in the ICT sector as a percentage of GDP |

X |

|||

|

Jobs |

Digital-intensive sectors' share in total employment |

X |

||

|

Workers receiving employment-based training, as a percentage of total employment |

X |

|||

|

New tertiary graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, as a percentage of new graduates |

X |

|||

|

Public spending on active labour market policies, as a percentage of GDP |

X |

|||

|

ICT task-intensive jobs as a percentage of total employment |

X |

|||

|

Society |

Percentage of individuals who live in households with income in the lowest quartile who use the Internet |

X |

||

|

Disparity in Internet use between men and women |

X |

|||

|

Top-performing 15-16 year old students in science, mathematics and reading |

X |

|||

|

OECD Digital Government Index |

X |

|||

|

Percentage of individuals aged 55-74 using the Internet |

X |

|||

|

Women as a share of all 16-24 year-olds who can program |

X |

|||

|

Percentage of individuals who use digital equipment at work that telework from home once a week or more |

X |

|||

|

Market openness |

Digitally-deliverable services as a share of commercial services trade |

X |

||

|

OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index |

X |

|||

|

OECD Foreign Direct Investment Regulatory Restrictiveness Index |

X |

|||

|

ICT goods and services as a share of international trade |

X |

|||

|

Share of businesses making e-commerce sales that sell across borders |

X |

|||

|

Trust |

Health data sharing intensity |

X |

||

|

Percentage of businesses in which ICT security and data protection tasks are mainly performed by own employees |

X |

|||

|

Percentage of individuals not buying online due to concerns about returning products |

X |

|||

|

Percentage of individuals not buying online due to payment security concerns |

X |

|||

|

Percentage of Internet users experiencing abuse of personal information or privacy violations |

X |

The use of advanced digital technologies by NZ firms appears to be low compared with other OECD countries. For instance, the information industry supplies only 3.2% of intermediate inputs used in New Zealand’s production, the lowest share among SAEs and one of the lowest in the OECD (Figure 2.7). The small size of information industries (Figure 2.1) also indicates that the use of digital services by New Zealand firms is lower than in many other OECD countries, either due to smaller demand or limited supply. In particular, IT and other information services, the main providers of digital services including cloud computing that provide firms on-demand access to ICT services, comprise only 1% of value added in New Zealand, half the OECD average. Although ICT investment as a share of GDP is relatively high (Figure 2.5), this may reflect the weak use of ICT services, notably cloud computing, which requires New Zealand firms to build up their own digital capabilities.

Surveys conducted of New Zealand firms also suggest that their use of advanced digital technologies is limited. For instance, only 16% of 852 small businesses surveyed by the Small Business Council (2019[13]) used cloud computing in 2019. Intezari et al. (2019[14]) found that two thirds of managers in predominantly large and medium-sized companies expressed only limited confidence in big data analysis, with one quarter having only rudimentary knowledge of big data. Few New Zealand firms integrate a digital strategy into their corporate strategy (PwC, 2017[15]). While the shutdown of non-essential businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the difference in performance between firms that exploited digital tools and those that did not, it did not result in a significant increase in the use of sophisticated digital tools. Among 2 280 NZ firms interviewed by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), the share of firms that took up communication tools like Skype or Zoom increased from 29% to 50% during the pandemic, but the use of cloud-based collaboration tools increased by a mere 5% (Better for Business, 2020[16]).

The share of information industry products in intermediate consumption, 2015

Note: See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: OECD (2021), Going Digital Toolkit

New Zealand is advanced in using some digital technologies. For instance, New Zealand firms make good use of some ubiquitous digital technologies, like online sales. Some 60% of SMEs sell online, the highest share in the OECD (Figure 2.5). Nevertheless, the weight of online sales in total sales is relatively low - some 62% of the companies reported that their internet sales account for 10% or less of total dollar sales in 2020 (Stats NZ, 2021[17]) – although smaller firms and firms in more ICT-intensive sectors sold relatively more online. The share of firms owning a website is above the OECD average (Figure 2.5), although it is lower than many other SAEs. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a dramatic rise in online shopping. While the number of people shopping online continues to increase, the average number of transactions, as well as the average size of each transaction, has decreased since the second quarter of 2020 (NZ Post, 2021[18]). New Zealand also has a high number of M2M (machine-to-machine) SIM cards issued per 100 inhabitants (Figure 2.5), which suggests an advanced use of the Internet of Things (IoT). In the aforementioned survey of 2 280 firms, 62% responded that they have or use IoT technologies (Better for Business, 2020[19]).

Diffusion of digital technologies generates positive productivity spillovers. For instance, Gal et al. (2019[20]) found that higher industry-level adoption of digital technologies increases the productivity of European and Turkish firms, particularly firms with initially high productivity levels. A wider use of cloud computing by small and credit-constrained firms would allow them to experiment with digital technologies without investing in their own digital facilities or hiring technicians, thereby boosting innovation and productivity.

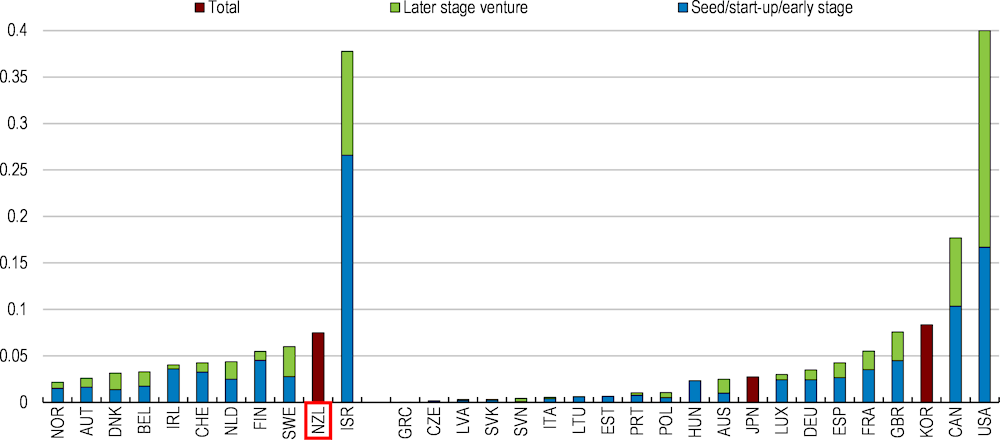

New Zealand’s digital innovation is moderate overall. For instance, R&D spending by information industries was about 0.3% of GDP in 2018, which is slightly lower than the OECD average (about 0.4%) but slightly higher than Australia (about 0.2%) (OECD Going Digital Toolkit). Furthermore, only 13% of IP5 patents (patents filed in at least two patent offices worldwide, including one of the five largest IP offices) filed by New Zealand entities were on ICT-related technologies, a share that is again lower than the OECD average (20%) or in Australia (19%) (Figure 2.5).

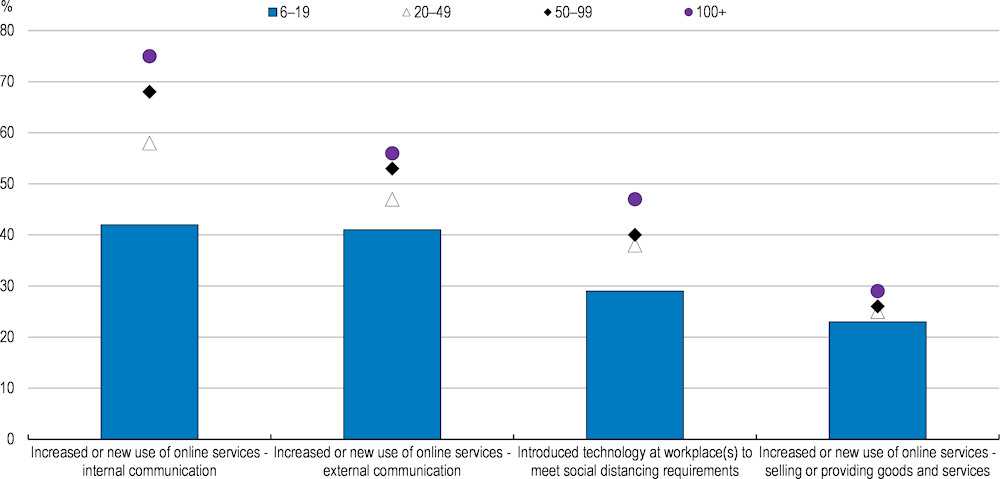

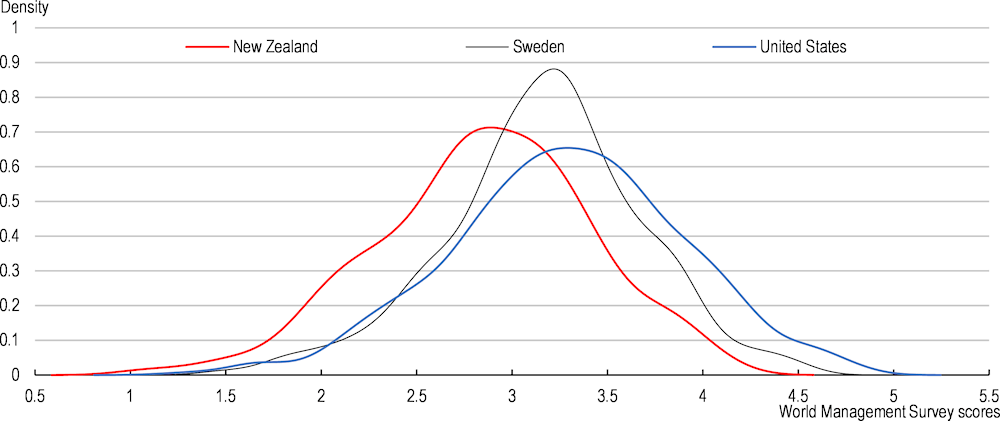

Digital innovation does not only concern R&D or patent application by information industries. It encompasses the introduction of novel products, production or delivery processes, as well as organisational and marketing changes enabled by digital technologies. However, New Zealand firms’ relatively low overall investment in R&D (0.8% of GDP as opposed to the OECD average of 1.8% in 2019) and in other intangible capital (OECD, 2017[21]), together with relatively poor management quality (see below) risk holding back New Zealand firms in achieving strong productivity gains. Indeed, while a high share of New Zealand firms self-reported that they improved customer relations and work efficiency by using digital technologies, only a small share managed to reduce the cost of entering new markets, introduce new products or collaborate with other businesses on innovation (Figure 2.8). Small firms are less likely to improve information management, coordination of staff and business activities or marketing than mid-sized firms, possibly because they invest much less in intangible capital (Figure 2.9).

Outcomes achieved using ICT, percentage of firms by size, 2020

Firms using digital technologies in response to COVID-19, share of total respondents in each size class

Note: Businesses were surveyed from August to December 2020 about how they responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Source: Stats NZ (2020), Business Operations Survey

Agriculture accounts for a large share of New Zealand’s economy and exports (Chapter 1). It exports over 90% of its products and is highly exposed to global competition; with virtually no producer support, prices are in line with the world market (OECD, 2021[22]). It has also been historically agile in adopting new technologies (Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment, 2020[23]).

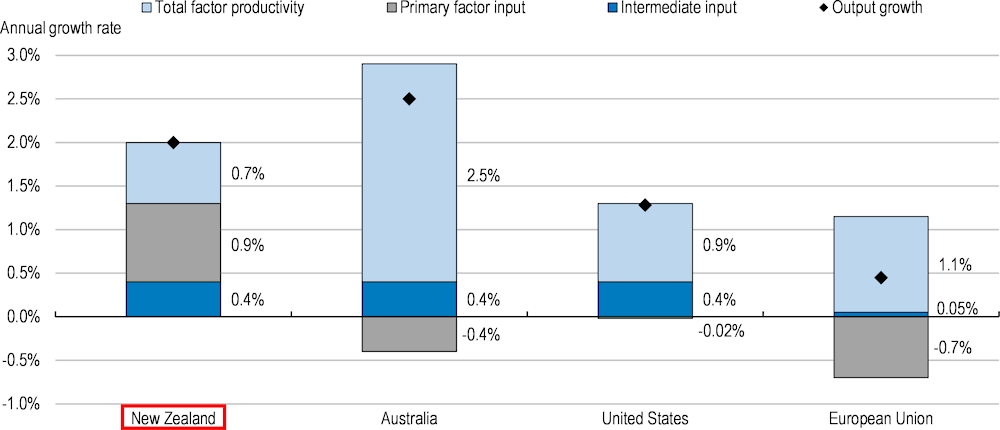

Despite its strong export performance, New Zealand’s agricultural sector faces several structural challenges. Its annual average total factor productivity (TFP) growth during 2007-16 was only 0.7%, lower than in Australia, the United States or the European Union (Figure 2.10). This points to slow adoption of new technologies and innovation, partly resulting from a heavy reliance on low-skilled migrant labour. With the inflow of migrant workers curtailed by border restrictions and unlikely to return to pre-COVID levels owing to immigration policy becoming more restrictive, faster technology adoption will be needed to cope with labour shortages.

The agricultural sector also faces other issues, such as a significant shift in global consumer preferences towards sustainable farming and healthy food. The emergence of new production technologies like plant-based or laboratory-produced meat and dairy products may eventually reduce demand for products from pastoral farming (Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment, 2020[23]). New Zealand’s farmers and food production firms need new technologies and business models that enable them to provide quality assurance to final consumers and communicate their environmental commitment more effectively (Baragwanath, 2021[24]). The agricultural sector also faces stricter regulations on fresh water pollution and will need to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions (see Chapter 1). The natural hazard risks farmers have to cope with are also likely to be heightened by climate change (Casalini, Bagherzadeh and Gray, 2021[25]).

Better use of digital technologies would help the agricultural sector to respond to these challenges. Digital innovation can unlock strong productivity growth. Intelligent and digitally connected machinery (the Internet of Things) would facilitate precision farming, helping farmers improve the accuracy of operations and optimise the use of inputs including fertilisers and pesticides (Paunov and Planes-Satorra, 2019[26]). It would also help farmers determine nutrient loss based on their application of fertiliser onto pasture, which is critical for implementing environmental regulations at the farm level. Increased use of robots would help to address labour shortages and boost productivity in horticulture, which often involves labour-intensive harvesting and packing processes; New Zealand has already developed some successful robotics for horticulture and pastoral farming (GOFAR, 2021[27]). Agritech New Zealand (2020[28]) estimates that effective use of these technologies could boost the agricultural sector’s output by 21% in the long run. Digital tools can also help the government to better manage natural hazard and biosecurity risks and provide quick responses in the case of an animal disease outbreak or flooding emergency.

Composition of agricultural output growth, 2007-16

Note: Primary factors comprise labour, land, livestock and machinery.

Source: OECD (2021), Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2021: Addressing the Challenges Facing Food Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Nevertheless, the take-up of digital technologies has been slow. For instance, only 16% of businesses in the agricultural sector were using fibre broadband in 2020, compared with an average of 64% across all sectors (Stats NZ, 2021[17]). Furthermore, less than 10% of over 4 000 farmers responding to the 2017 Survey of Rural Decision Makers (Manaaki Whenua, 2017[29]) made use of precision agriculture, while only 3% indicated uptake of automation or robotics.

New Zealand’s exports are constrained by its geographical remoteness from large markets and suppliers of intermediate inputs (Fabling and Sanderson, 2010[30]; de Serres, Yashiro and Boulhol, 2014[31]). This remoteness increases shipment costs, which holds back the competitiveness of New Zealand exports, and information frictions, which make it harder for New Zealand exporters to penetrate foreign markets and establish export relationships. This “tyranny of distance” not only holds back New Zealand’s exports, but also the adoption of digital technologies. Without export sales, New Zealand firms may not be able to capture sufficiently large returns to justify risky investments in new technologies and intangible capital. An effective use of digital tools like websites or online platforms can help to reduce the tyranny of distance by facilitating export entry via reduced search costs and information asymmetries in international transactions (see Box 2.2).

If digital take-up enables more New Zealand firms to start exporting or expand their export markets, this would, in turn, accelerate the adoption of digital technologies and intangible investments (Box 2.2). This interaction between digital take-up and exporting is an important driver of diffusion of digital technologies. Firms that export and adopt digital technologies become more productive and competitive, thereby expanding their domestic market shares and attracting resources like labour. This reallocation of resources toward digitalised exporting firms boosts aggregate productivity (Melitz, 2003[32]). Exporting also provides firms with opportunities to learn advanced technologies and management practices from foreign buyers (De Loecker, 2007[33]), which would help New Zealand firms to catch up to the global productivity frontier (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2021[10]).

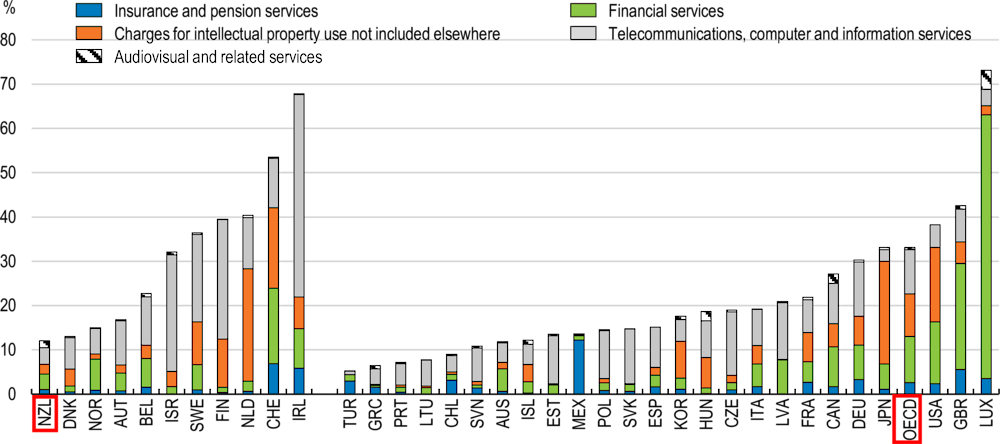

Another way of reducing the tyranny of distance is to increase exports by the weightless sector, such as digital services that can be delivered predominantly online. The share of predominantly digitally deliverable services in New Zealand’s service exports is relatively low compared with the median of OECD countries (Figure 2.5) or other small advanced economies (Figure 2.11). There are opportunities to increase exports of digital services, particularly for the digital gaming industry, which has already established a strong track record in New Zealand. However, the competitiveness of digital services is constrained by a severe skills shortage, which has been greatly aggravated by COVID-related border restrictions (Chapter 1) and a weak domestic pipeline of skilled digital workers (see below). Furthermore, distance can hold back competitiveness in other ways besides increasing shipping costs. For example, some digital services delivering highly tailored products require intensive face-to-face interactions (Australian Productivity Commission and New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2019[34]). The lack of agglomeration of innovation activities in New Zealand also limits competitiveness in knowledge-intensive services. New Zealand’s export-oriented digital start-ups often seek to establish their presence in large foreign markets to better serve foreign customers and tap into local knowledge sources (Sim, Bull and Mok, 2021[35]).

As a percentage of total services exports, 2017

Note: For Chile, Mexico, New Zealand and Switzerland, Audiovisual and related services include Other personal, cultural and recreational services. See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: OECD, International Trade in Services Statistics; WTO (2018), Trade in Commercial Services

Online platforms can help small firms in particular to export as they often struggle to cover the sizable entry costs of exporting related to finding foreign buyers and establishing distribution channels (Melitz, 2003[32]). In 2020, 31% of New Zealand firms with 20 to 49 employees that sold online also exported online, well above the overall share of exporters in this size cohort (23.5%), implying that firms using traditional trade channels were much less likely to export (Figure 2.12). In contrast, for firms with over 50 employees, the two shares are about the same, implying that larger firms were equally likely to export online or through traditional channels, possibly because they can bear traditional export entry costs.

Even though small firms selling online enjoy reduced export entry costs, the low share exporting online suggests that barriers to exporting remain high even with the use of digital tools. One such barrier is the lack of intangible capital that underpins export competitiveness. For example, established brands and reputation among foreign consumers are important for expanding sales, particularly from online platforms (Box 2.2). A lack of brand recognition in foreign markets has been the most common challenge acknowledged by New Zealand’s exporters (Sim, Bull and Mok, 2021[35]). Another potential barrier is limited capabilities by small firms to make an effective use of digital tools. Joint research by the OECD and MBIE finds that the adoption of ultra-fast broadband, which supports an extensive use of digital technologies, increases the chance that New Zealand firms start exporting, particularly for those that are making effective use of digital tools. Indeed, New Zealand firms that export use Internet more for enhancing communication and business collaboration than non-exporting firms do, and also deploy websites equipped with more functions (Box 2.3). This underscores the importance of support measures that help firms develop capabilities to leverage digital tools for capturing new business opportunities and boosting profits.

Share of exporting firms in each size cohort, online versus general exports, 2020

Note: The share of firms exporting online is computed as the share of firms with non-zero sales via Internet that sell abroad over all firms with non-zero sales via Internet. The general share of exporting firms is the share of firms reporting non-zero exports.

Source: Computed by the Secretariat based on Stats NZ (2020), Business Operations Survey

Digital technologies facilitate trade between countries by reducing transaction and information costs through faster and cheaper communication. One might expect that they partially offset the well-documented negative impact of distance on trade flows. However, empirical evidence is mixed.

On the one hand, Freund and Weinhold (2004[36]) reported that a 10 percentage point increase in the growth of the number of web hosts in a country led to a 0.2-percentage point increase in service export growth during 1995-1999. Osnago and Tan (2016[37]) reported that higher Internet adoption (defined as the number of individuals using the Internet per 100 persons) by both the exporting and the importing countries boosts bilateral exports: a 10% increase in Internet adoption in the exporting (importing) country increases bilateral exports by 1.9% (0.6%). On the other hand, these trade-promoting effects coming from increased Internet use do not necessarily mean trade has become less sensitive to distance. On the contrary, Disdier and Head (2008[38]) reported that the impact of distance on bilateral trade has increased since the 1970s, despite the development and diffusion of ICT. Akerman, Leuven and Mogstad (2018[39]) found that roll-out of broadband Internet made international trade by Norwegian municipalities more sensitive to distance and the economic size of partner countries. Furthermore, digital services trade, which does not involve shipment costs, still seems to be negatively affected by distance. For instance, Blum and Goldfarb (2006[40]) showed that US imports of digital services consumed over the Internet fell with the distance between the US and the exporting countries.

Although digital technologies cannot nullify the impact of distance on trade, effective use of digital technologies can help firms to start exporting or enter new foreign markets by reducing the costs associated with searching foreign buyers or gathering information on foreign markets (Freund and Weinhold, 2004[36]). Osnago and Tan (2016[37]) found that higher Internet usage by the exporting country increases bilateral exports mainly through a larger number of exported products. However, the low entry cost to online platforms like AliExpress results in a large number of firms competing for consumers’ attention, congesting consumers’ search process and thus causing serious information frictions (Bai et al., 2020[41]). As a result, firms with sizable past sales, established reputation or recognisable brands are more likely to capture larger sales, thanks to their higher visibility on online platforms.

Exporting encourages firms to adopt digital and other technologies that improve productivity because it increases the return to investment by allowing firms to capture larger sales from both foreign and domestic markets (Bustos, 2011[42]). Across OECD countries, including New Zealand, exporting firms are found to innovate more than non-exporting firms (Baldwin and Gu (2004[43]) for Canada; Damijan, Kostevc and Polanec (2008[44]) for Slovenia; Sin et al. (2014[45]) for New Zealand; and Peters, Roberts and Vuong (2020[46]) for Germany). In some cases, the decisions to adopt digital technologies and export can be made in tandem. For instance, some firms are not sufficiently productive and thus cannot capture sufficient export revenue to cover trade costs. They have an incentive to adopt new technologies to boost productivity so that they can start exporting (Lileeva and Trefler, 2010[47]).

Joint research by the OECD and the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (Sanderson, Wright-McNaughton and Yashiro, 2022[48]) explores the role of ultra-fast broadband (UFB), such as fibre, in promoting exports by New Zealand firms. It investigates whether adopting UFB increases the probability that a firm will start exporting.

UFB supports a more intensive use of digital tools like websites or online platforms, as well as adoption of advanced digital technologies that require transmitting large data instantaneously, such as Cloud Computing or the Internet of Things. As discussed in Box 2.2, digital tools can help firms find foreign buyers and establish export relationships by reducing search and information costs, which are often considered as key barriers to export entry (Melitz, 2003[32]). Furthermore, UFB can also improve the productivity of New Zealand firms that use it to support their production and management processes (Fabling and Grimes, 2021[49]). This enables them to compete in overseas markets despite the increased costs and competition associated with exporting (Melitz, 2003[32]; Fabling and Sanderson, 2013[50]).

However, UFB may not boost firms’ export capabilities to the same extent: it can be more effective when firms are making strategic use of the Internet or more sophisticated digital tools. This is in line with the view that good management practices and organisational changes condition the productivity gains from the adoption of digital technologies (Box 2.7).

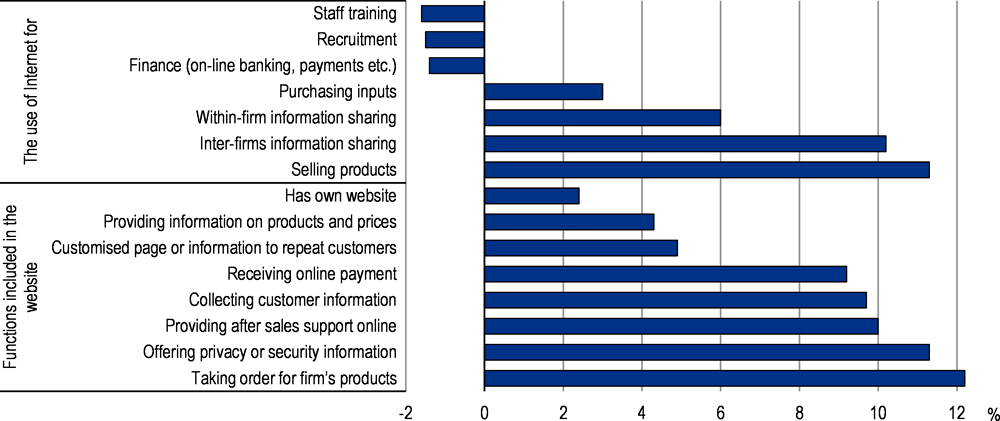

It is found that New Zealand firms that export not only use the Internet more extensively, but also use the Internet more for communication and collaboration purposes. For example, the probabilities that exporting firms use the Internet to share information with business partners or sell products online are more than 10 percentage points higher than for non-exporters (Figure 2.13). Exporters also own websites with more functions. They are significantly more likely to own websites equipped with functions like placing an online order or after-sales support.

Exporters’ advantage over non-exporters in specific Internet uses or website features

Note: The chart displays how much exporters are more likely than non-exporters to use Internet for a given purpose or to have the specific function in their websites, after controlling for differences in firms’ size and industry.

Source: Sanderson, Wright-McNaughton and Yashiro (2022[48]).

To identify the impact of UFB on exports, the probability of export entry by a New Zealand firm is estimated as a function of UFB adoption. The exercise exploits the rich information on ICT take-up and export activity by New Zealand firms included in several waves of the Business Operations Survey (BOS), which are linked to broader firm-level information contained in the Longitudinal Business Database and Integrated Data Infrastructure. The BOS includes an ICT module that surveys ICT take-up every two years.

The empirical analysis focuses on two cohorts of firms that were not exporting nor using UFB in 2010 and 2012 and tracks whether these firms started exporting over the following four years. In particular, it estimates the extent to which non-exporting firms that adopted UFB in the two years between ICT modules were more likely than other non-exporters to start exporting either during this period (time t) or two years later (t+2). In order to assess whether the impact of UFB is more important for firms that have been making more intensive use of digital tools, an indicator that summarises the information on a firm’s use of Internet and its website functions overviewed in Figure 2.14 (ICT intensity) is included in the model. The indicator is lagged two years, so that it captures how intensively firms were using digital tools when they adopted UFB. Another indicator of ICT use, which captures the extent to which firms are using the Internet for enhancing efficiency of internal operations, such as their internal communication and human resource management (ICT-process focus), is also included.

After controlling for a wide range of firm characteristics that are likely to affect export entry and intensity of ICT use, the results suggest that firms that adopted UFB enjoy a higher probability of export entry both this period and two years later (Table 2.2, columns 1 and 2). While both the contemporaneous and future effects are statistically significant, the future effect is larger and more statistically significant. For instance, firms that adopted UFB were 6.3 percentage points more likely to export two years later. While past indicators of ICT use do not predict export entry by themselves, the coefficients on their interactions with UFB take-up are positive and significant (columns 3 and 4), implying that the impact of UFB in promoting export entry is stronger for firms that were using digital tools more intensively or for improving internal efficiency.

Firms in export-intensive industries

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Export at t |

Export at t+2 |

Export at t |

Export at t+2 |

|

|

Adopts UFB |

0.036* |

0.063** |

0.039* |

0.063** |

|

(0.022) |

(0.028) |

(0.022) |

(0.028) |

|

|

ICT intensity |

-0.000 |

0.003 |

-0.004 |

-0.003 |

|

(0.005) |

(0.008) |

(0.005) |

(0.007) |

|

|

ICT - process focus |

0.002 |

-0.000 |

-0.000 |

-0.009 |

|

(0.006) |

(0.009) |

(0.007) |

(0.010) |

|

|

Adopts UFB#ICT intensity |

0.019* |

0.027 |

||

|

(0.010) |

(0.017) |

|||

|

Adopts UFB#ICT process focus |

0.009 |

0.035* |

||

|

(0.015) |

(0.020) |

|||

|

R-squared |

0.045 |

0.045 |

0.048 |

0.054 |

|

Number of observations |

1080 |

810 |

1080 |

810 |

Note: The table reports the estimated coefficients of a linear probability model of export entry by initial non-exporters. The numbers in parentheses are standard errors. ** and * represent statistical significance at 5% and 10% respectively. The model includes control variables such as firm size, capital intensity, human capital, inward and outward foreign direct investment, and R&D, as well as ANZSIC 1 digit industry and year dummies (all at t-2). The indicators ICT intensity and ICT process focus are principal components capturing the intensity of Internet use described in figure 2.13 and the extent to which the Internet is used to enhance internal efficiency. They are lagged so as to capture these features prior to fibre adoption (at t-2). The estimation sample is firms in five export-intensive industries, which are: Agriculture, forestry and fishing; Manufacturing; Wholesale trade; Information media and telecommunications; and Professional and technical services.

Source: Sanderson, Wright-McNaughton and Yashiro (2022[48]).

Disclaimer by Stats NZ: These results are not official statistics. They have been created for research purposes from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) and Longitudinal Business Database (LBD) which are carefully managed by Stats NZ. For more information about the IDI and LBD please visit https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/ The results are based in part on tax data supplied by Inland Revenue to Stats NZ under the Tax Administration Act 1994 for statistical purposes. Any discussion of data limitations or weaknesses is in the context of using the IDI for statistical purposes, and is not related to the data’s ability to support Inland Revenue’s core operational requirements.

Entry costs of exporting are more burdensome for small firms, which lack scale to disperse the sizable fixed costs. By reducing entry costs (Box 2.2), fast Internet may thus benefit small firms disproportionally. At the same time, small firms may lack the capabilities to exploit fast Internet effectively to advance their internationalisation strategies. Sanderson, Wright-McNaughton and Yashiro (2022[48]) find that while UFB adoption increases the probability of export entry by smaller firms, the magnitude of this effect depends importantly on the intensity of ICT use prior to the adoption. Especially, the UFB adoption increases the probability that smaller firms start exporting two years later only if they were making more intensive use of digital tools.

The importance of strategic use of digital tools in export entry indicates the need to combine financial or technical assistance with effective business strategy advice on how to exploit digital technologies to expand market reach. Policies to promote exports and digital take-up by New Zealand firms should include measures to build up their managerial capabilities in exploiting digital technologies, as is done in Germany (see below).

In 2020, 96% of individuals comfortable with using the Internet used it daily at home (InternetNZ, 2020[51]), one of the highest shares OECD-wide. On average 65% of Internet connections at home are fibre, but this share varies across regions, ranging from 74% in Auckland to 48% in the West Coast region (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, 2021[52]). Despite very high Internet access, some population groups have been left out. For instance, 31% of individuals living in social housing and 27% of disabled individuals have no access to Internet and students from certain minority groups, particularly Pasifika, have lower access to Internet at home (Grimes and White, 2019[53]). Shares of individuals without Internet access are also higher among those living in towns with a population less than 25 000, older persons, particularly those aged over 75 years, the unemployed and inactive. Lack of Internet access limits people’s social relations, interactions with public authorities and ability to receive public services, lowering subjective wellbeing (Grimes and White, 2019[53]). InternetNZ (2018[54]) has estimated that the gains from closing the digital divide, and allowing more people to save time, communicate online and increase their employability, could amount to NZD 280 million per year. Before the pandemic, only about one-third of individuals used the Internet to interact with the government, far below the 60% OECD average. This partly reflects the limited digitalisation of government services, which is mostly at the stage of digitising existing processes (see below). COVID-19 has exacerbated the costs of the digital divide as those with poor access to Internet could not access government services, such as education services that were provided online during the lockdown.

As became clear at the onset of the pandemic, access to the Internet is, by itself, not enough for full digital inclusion. Other aspects, such as skills, trust and motivation matter as well. In fact, it is estimated that one in five New Zealanders falls short on at least one of these dimensions (New Zealand Digital Government, 2020[55]). For older people, who are more likely to be digitally excluded, the main barrier is not access to the Internet but other factors like skills, trust, cost and disabilities. In particular, lack of trust is an important factor preventing the elderly from using the Internet at all (Lips et al., 2020[56]). Only one third of New Zealanders aged 65 or above can easily access information on how to keep personal information secure online, and close to 50% of those over 70 would not know who to contact in the case of online security incidents, such as password theft (InternetNZ, 2020[51]; Bank of New Zealand, 2021[57]). As digital technologies evolve, older people who did not acquire digital skills at school or at work are exposed to higher risks of digital exclusion (Lips et al., 2020[56]). Among Māori and Pasifika, the cost of the Internet and devices is one of the primary barriers to digital inclusion. Other barriers are lack of skills and English-only digital platforms.

In response to the digital difficulties faced by older New Zealanders, the government earmarked NZD 600 000 in its 2019 Wellbeing Budget for digital literacy programmes for seniors to be spent over three years. It was found that elderly who had attended programmes such as “Pacific Senior CONNECT” and “Better Digital Futures” significantly improved their digital communication skills, learnt how to communicate through video and use email more often (The Government of New Zealand, 2020[58]). Some programmes also helped seniors to get affordable Internet access at home. To facilitate the use of digital services by disabled persons, the government has introduced a “web accessibility standard”, which lays out guidelines on how to ensure that webpages are accessible to people with, for instance, low vision or hearing loss. However, many agencies fail to meet this standard.

The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the trend toward increased teleworking. In 2020, 73% of New Zealanders who could work from home did so for some or all of the time (InternetNZ, 2020[51]). In addition, half of the respondents who worked partly from home under the pandemic expressed a desire to work from home even more frequently in the future. However, slow Internet speed has been recognised as a major barrier to teleworking (InternetNZ, 2020[51]). In remote areas, some 44% of New Zealanders are concerned or very concerned about poor Internet connections.

Digital technologies can transform the internal processes and operations of government and, consequently, how public services are designed and delivered. Extensive use of digital technologies and data enables governments to be more efficient, agile and responsive, and even anticipate people’s needs. The early adoption of digital technologies referred to as e-government focused on increasing efficiency and transparency in the public sector through the digitisation of existing processes. Indeed, New Zealand’s government has achieved some back-office efficiencies and some more user-friendly interfaces through its e-government efforts. For instance, the myIR system for reporting income tax in New Zealand provides online tax forms with much of the relevant data pre-filled, reducing the scope for erroneous or missing information and the compliance burden on taxpayers. Also, companies can be registered online, and thanks to a data-sharing arrangement between the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the New Zealand Companies Office (NZCO), firms expanding across the Tasman can register easily in the other country. More recently, the government has been seeking to systematically improve user experience or approach system design from the perspective of customers. For instance, it launched the Business Connect platform in 2019, an online one-stop shop for firms to apply for and renew licences and permits. This platform has been evolving incrementally and will soon allow firms to manage their data held by the government and re-use the information they previously submitted to the authorities.

Governments across OECD countries are now aiming to upgrade their e-government efforts into the so-called digital government, which entails digitalisation of policy making and implementation processes as well as collaboration across public sector organisations, with the aim of delivering more integrated and seamless, as well as user-driven and proactive, services (OECD, 2020[59]). New Zealand ranks relatively high in the OECD Digital Government Index 2019, which captures progress toward digital government (Figure 2.5). In 2020, the government introduced a strategy for a Digital Public Service, which set broad objectives for the digital transformation of public services, with a programme of work.

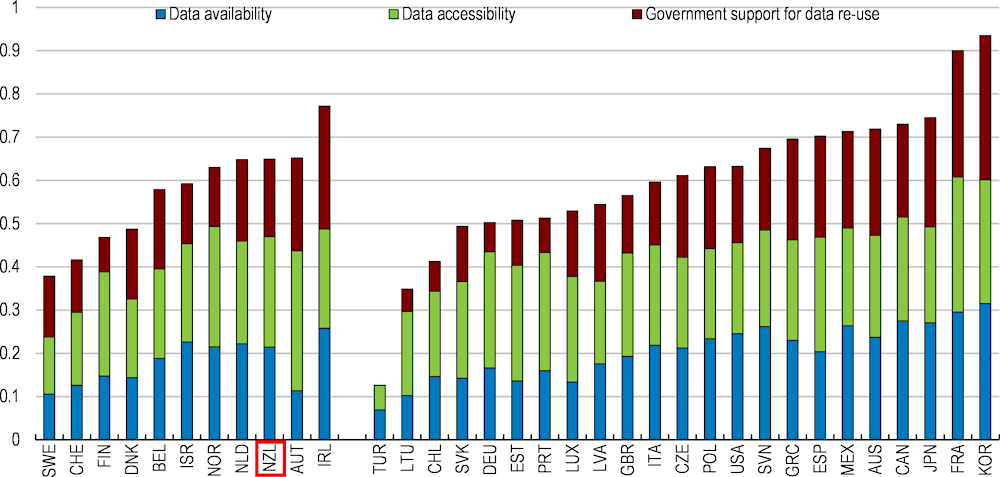

New Zealand is relatively advanced in terms of opening government data and systematically releasing government policies and decisions online. It ranks relatively high among SAEs when it comes to availability, accessibility and re-usability of government data (Figure 2.14). The statistical office has been leading and coordinating New Zealand’s data strategy across agencies since 2017. The strategy aims to increase availability and accessibility of government data by, for instance, enhancing government data visibility, identifying data gaps and implementing an “open by design” culture, whereby data are released in a format that facilitates wider use by the public (Government Chief Data Steward, 2018[60]). One area with some room for improvement is promoting the re-use of the government data outside the public sector, for instance through long-term partnerships with open data communities (OECD, 2020[61]). Efforts are underway, such as GovHack, a large annual Australasian event that involves dialogues between stakeholders and a two-day hackathon in which participants use open government data to propose innovative solutions to the challenges facing government and communities.

New Zealand has a good base for ensuring coherence in the use of digital technologies across policy areas, thanks to initiatives like the Digital Government Partnership, which brings together agencies from across the public service to support the goal of an all-of-government digital system. The function of this partnership is mostly advisory and does not involve decision-making on ICT investment across government agencies or evaluation of their ICT projects. The Partnership, however, annually disburses NZD 5 million to foster digital and data innovation by public sector organisations. There is room to strengthen the authority of the coordination body over government agencies in moving digitalisation forward (see the next section).

OURdata Index scores, 2019

Note: OURdata Index is a composite index with a maximum value equal to “1” corresponding to the best practices. See Lafortune and Ubaldi (2018) for more information. See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: OECD (2021), OURdata Index on Open Government Data

New Zealand’s government trails behind other OECD countries in terms of pro-activeness, defined as grasping citizens’ changing needs and improving digital services accordingly in an anticipatory way (OECD, 2020[61]; New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2021[10]). One way of improving this is to enhance the participation by experts and stakeholders in the early stages of designing digital services (OECD, 2020[59]). The strategy for Digital Public Service aims for a more agile and adaptive digital public service. Frontrunners in digital government, such as Estonia and Korea, demonstrate what could be done to enhance and expand the scope of digital services in New Zealand. For instance, Estonia has leveraged digital IDs and a state-of-the-art data sharing technology (the X-Road) to deliver all but three public administrative services (marriage, divorce and real estate transactions) online and provide secure, transparent and traceable encrypted communication between public and private service providers and citizens (OECD, 2019[62]). Its digital ID framework is built on trust between the government and citizens, underpinned by legislation such as the amended 2018 Personal Data Protection Act, which for instance stipulates that citizens be informed when and for what purpose their data are being used by the government as well as contact information of the officials in charge of this use. Korea introduced mobile ID cards that allow people to use government services from their smartphones and enabled citizens to download personal information held by public institutions and submit them directly to public authorities and banks through MyData portal (OECD, 2020[63]). The government also plans to increase the provision of personally customised digital services related to health check-ups, national scholarship applications, civil defence education or tax payments. Although Korea is already the frontrunner in the openness of public data (Figure 2.14), it will facilitate the use of public data even further to strengthen cooperation between the public- and private sectors and to promote new industries, such as autonomous driving and health care. The government is also investing in digital infrastructure and innovation in the public sector, for instance expanding 5G wireless networks and building a security control system using artificial intelligence.

A significant impediment to an extensive use of digital technologies by the government has been the absence of data companies based in New Zealand. This has been a barrier because any data stored, processed or transmitted by cloud services could be subject to legislation and regulation in the countries where data are stored. The decision by Microsoft and Amazon Web Services to establish datacentres in New Zealand is likely to address this data sovereignty issue, enabling the government to use cloud computing more intensively and adopt other data-intensive digital technologies.

New Zealand has recently embarked on the preparation of a comprehensive national digitalisation strategy, following up on the 2017 Building a Digital Nation report. Policy initiatives on digital transformation have been fragmented and subject to unstable budgeting. In 2020, the Digital Government Partnership (see above) put forth a strategy on delivering high-quality digital public services. Also, Industry Transformation Plans for digital technologies and agritech industries have been produced. However, a national digital strategy encompassing a wide range of policy areas such as education, labour market and social affairs was missing, making it difficult for government agencies to work in a coherent way toward New Zealand’s digital transformation. The new national strategy is to strengthen coordination of digitalisation policies under three pillars: (1) trust in the digital environment, which includes sound data privacy; (2) digital inclusion, such as endowing New Zealanders with the right skills to thrive in digital workplaces; and (3) growth, which involves promoting the adoption of digital technologies among small businesses (New Zealand Government, 2021[64]). It is important that this strategy cover all relevant policy areas and set a clear roadmap and action plans. Furthermore, these action plans have to be implemented rigorously, on the back of strong political support.

The new national strategy is the responsibility of the Minister for the Digital Economy and Communications, appointed in 2020 to enhance the coordination of digitalisation policies. At the moment, various digitalisation strategies co-exist, including the one for Digital Public Service mentioned above and initiatives developed by the so-called government functional leads. For example, the Digital Government Partnership is led by the Government Chief Digital Officer, who is also the Chief Executive of the Department of Internal Affairs. The digital technologies Industries Transformation Plan is produced jointly by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment and NZTech, a prominent social partner. Examples of the governance of national digital strategies in other OECD countries indicate that high-level leadership and a centralised mandate for strategic coordination, often above ministerial level, are important in advancing a holistic digital strategy (Box 2.4). While this does not necessarily imply that New Zealand needs a single government body overseeing all digitalisation policies, it highlights the importance of a clear hierarchy and a strong political mandate for the coordination body.

Monitoring and evaluation are essential to ensure effective implementation of a national digital strategy. However, New Zealand has not set transparent targets against which progress is assessed or the effectiveness of existing strategies evaluated. A lot of data and indicators used by OECD countries to capture the progress in digitalisation are missing for New Zealand, making it difficult to benchmark New Zealand against best performers to identify room for catch up. For instance, many of the indicators in the OECD’s Going Digital Integrated Policy Framework (OECD, 2020[65]), which help identify complementary policies to boost wellbeing through digitalisation, are not available for New Zealand (see Box 2.1). These data need to be collected to provide the basis for a national digital strategy and to monitor progress against this strategy.

The effectiveness of a national digitalisation strategy hinges on good coordination among government agencies and social partners. In order to ensure this, some OECD countries assign high-level leadership and centralised responsibility for strategic co-ordination above ministerial level. In these countries, a coordination office under the president, prime minister or chancellor usually drafts the national strategy backed by a strong political mandate. The office involves key ministries and stakeholders in the process, and also often leads strategic co-ordination. For instance, in Mexico and the Slovak Republic, the Prime Minister holds a strong mandate for digital issues, including for the drafting of the strategy, executed through a dedicated co-ordination office. In other countries like Chile, Estonia, Korea and Luxembourg, certain functions are ensured by the Prime Minister, notably for strategic co-ordination, but ministers still play an important role both in providing input to strategy development and in implementing the strategy.

The central co-ordination office may also be a centre within the government. The centre usually supports the highest level of the executive branch of government. Examples include the German Chancellery, the UK Cabinet Office and the White House Executive Office. Each government agency implementing the strategy often has a focal point, such as a chief digital officer, who ensures operational co-ordination. These agencies also monitor implementation and report to the co-ordinating office.

In other countries where political support is not as strong, the responsibility of strategic coordination of the National Digitalisation Strategy is allocated to a lead ministry often dedicated to digital affairs (as in Belgium, Japan, Poland, Portugal and New Zealand). In some countries, this ministry has responsibility for several policy areas including a digital portfolio and, in a few countries, there is not one but several ministries in charge.

Source: OECD (2019), Going Digital: Shaping Policies, Improving Lives, OECD Publishing, Paris.

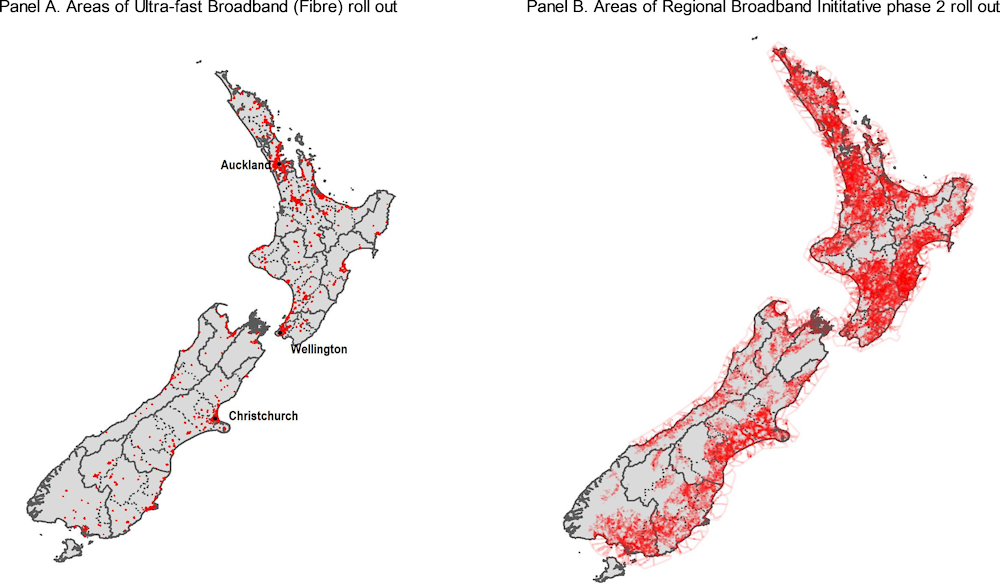

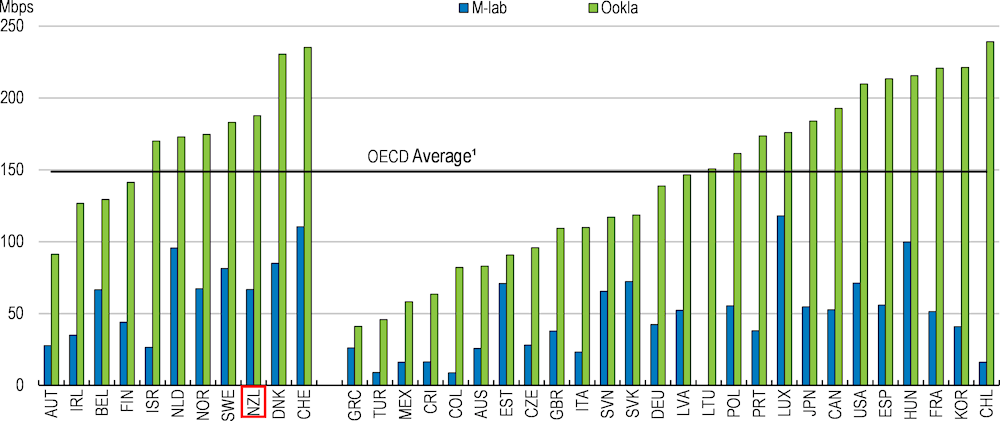

Access to fast and reliable connectivity is a prerequisite for the diffusion of digital technologies. New Zealand has been rolling out high speed broadband, with a target to provide 99.8% of its population with access to improved broadband by end-2023. In particular, the Ultra-Fast Broadband (UFB) programme has been rolling out fibre connections mainly in the urban areas, namely large cities (Figure 2.15, Panel A). It aims to provide access to fibre to 87% of the population in over 390 towns and cities by end-2022. As of July 2021, 85% of New Zealanders could already access fibre, and 65% had taken it up (Crown Infrastructure Partners, 2021[66]). In rural areas, where UFB roll-out is too costly, the second phase of the Rural Broadband Initiative (RBI) aims to provide high-speed broadband, primarily through wireless technologies such as 4G (Panel B). The government has also allocated NZD 10 million over two years to free up radio spectrum suitable for providing 5G technology in rural communities. Furthermore, more than NZD 46 million has been allocated to reducing network congestion on mobile networks in rural areas where data use has reached capacity constraints. These initiatives are expected to put New Zealand’s broadband speed, which is already higher than the OECD average (Figure 2.16), on a par with the top performers.

Note: Red dots in Panel A are areas covered by funding from the Crown Infrastructure Partners to build ultrafast fibre broadband (UFB) service to premises within those areas. Red dots in Panel B are areas covered by Fixed Wireless Access or wireless broadband service under the Rural Broadband Initiative Phase 2.

Source: New Zealand Crown Infrastructure Partners.

1. Sample average. See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: OECD, based on Ookla, November 2021 and M-Lab (Worldwide broadband speed league) as measured between July 2019 and June 2020.

The high share of fibre in broadband implies that New Zealand’s communication infrastructure will be able to support the use of new digital technologies that require transmitting large quantities of data rapidly (Figure 2.17). The number of companies using fibre-to-the-premise has risen rapidly in recent years, especially among smaller firms. The overwhelming reason why some companies are still not using fibre-to-the-premise is unavailability in their location (Stats NZ, 2021[17]). One notable feature of the fibre roll-out in New Zealand is that it has prioritised schools. Because almost all state schools had fibre connections by 2016, New Zealand’s schools are equipped with some of the best digital tools in the OECD (Figure 2.18). Grimes and Townsend (2017[67]) report that access to fibre broadband increased the proportion of students who achieved or outperformed the National Standard in mathematics, writing and reading by a small, but statistically significant margin. However, communication infrastructure and digital tools tend to be used in less educationally relevant manners by students from poorer and less privileged communities.

Note: See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: OECD (2021), Broadband Portal

New Zealand’s mobile network infrastructure serves over 95% of the population, but covers only half of the territory. Moreover, download speeds are between 32 to 44% slower in rural areas than in urban areas, constraining the use of data-intensive digital tools in rural areas. The Mobile Black Spot Fund (MBSF) aims to provide greater mobile coverage on approximately 1 400 kilometres of state highway and in 168 tourism locations where no coverage currently exists. To expand mobile coverage in remote regions in accordance with the MBSF and the RBI Phase 2 Initiative, New Zealand’s three major mobile network operators, Spark, Vodafone and 2degrees, have formed a joint venture, the Rural Connectivity Group (RCG). Funded by both the RBI, the MBSF and the three mobile companies, the RCG builds communications infrastructure that can be used by all three operators. The MBSF has, however, so far progressed slower than the UFB and RBI programmes, holding back the use of digital technologies in remote areas.

Low-income households may be deterred from using advanced digital tools to improve their wellbeing if broadband service costs are too high. This also risks excluding them from accessing various online tools that connect them to government services, jobs and training opportunities as well as housing, limiting their social mobility. The monthly price of the unlimited broadband package, which 85% of Internet users subscribe to, averages NZD 73 (Commerce Commission, 2021[68]), corresponding to 4.5% of the median household income of the lowest income quantile. The share of New Zealanders concerned about the cost of Internet has declined over the past five years, and is considerably smaller than shares of those concerned with other issues like inappropriate online content (InternetNZ, 2020[51]). Instead, a more relevant issue that can lead to digital exclusion of disadvantaged individuals is the cost of digital devices, which has surged due to COVID-related increases in transportation costs and disruptions in global supply chains. During the COVID-19-induced lockdowns, the government distributed free devices to students from disadvantaged households in addition to providing Internet connections and paying usage fees to prevent them from being excluded from online school courses. The government could consider providing subsidies for the comprehensive costs of accessing fast Internet, which include broadband subscription and digital devices. For instance, the United States subsidised broadband access by low-income households during the pandemic through the Emergency Broadband Benefit Program. Households qualifying for the programme received up to USD 50 per month to pay for Internet service and a USD 100 discount if they bought a computer, laptop or tablet. This temporary measure was extended into the permanent Affordable Connectivity Program in December 2021. Subsidised broadband access by disadvantaged households improves their employment prospects and earnings (Zuo, 2021[69]), contributing to inclusiveness. It would also allow the government to advance its e-government initiatives by moving a wider range of public services online without endangering access to these services by disadvantaged households.

Percentage of students in schools where the principal agreed or strongly agreed with the statement

To thrive in the digital workplace, workers need strong cognitive skills - literacy, numeracy and problem solving in a technology-rich environment – and socio-emotional skills (OECD, 2019[70]). A well-rounded skills set is the key that allows people to unlock all the benefits of Internet use and use the Internet in diversified and complex ways rather than just for information and communication (ibid). People with strong cognitive skills are better able to adapt to labour market changes, such as workplace reorganisation to use digital technologies more productively.

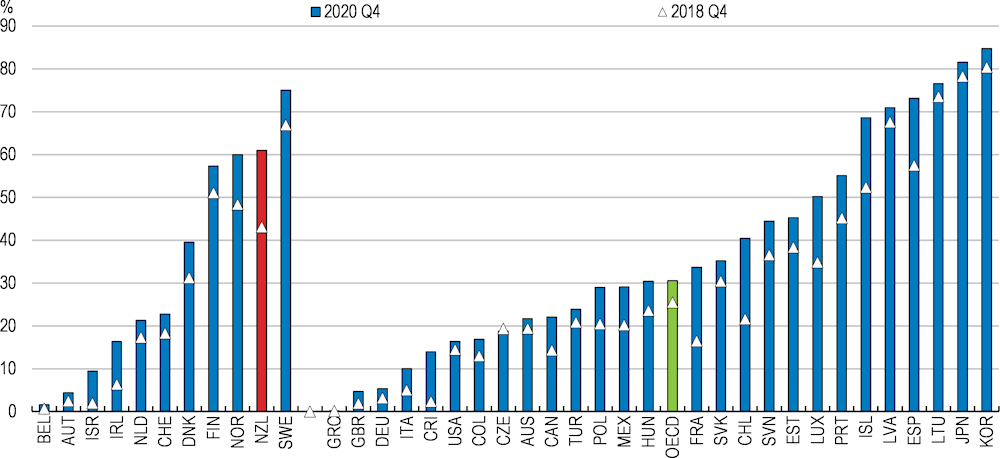

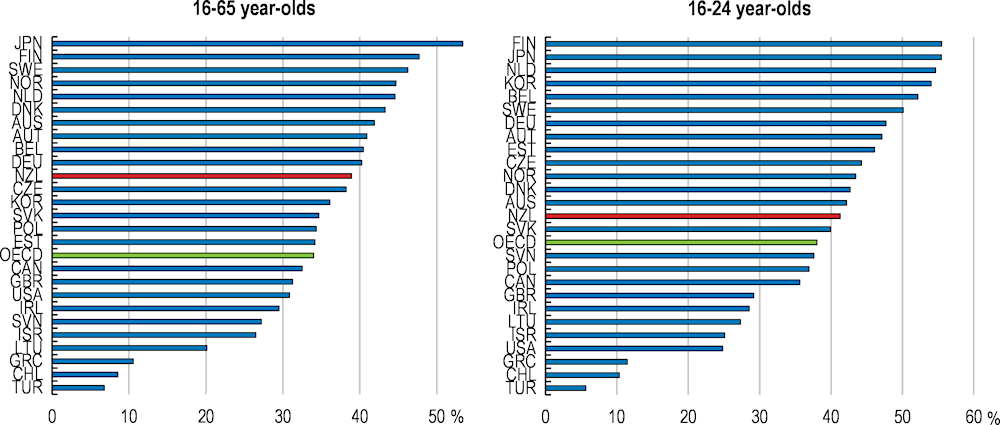

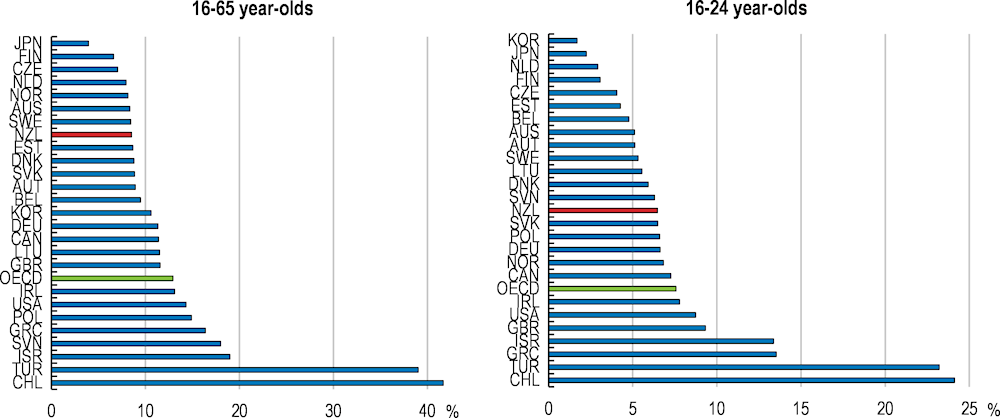

The share of the working-age population (aged 16-65 years) with a well-rounded skills set is above the OECD average (Figure 2.19) and the share lacking basic skills is one of the lowest (Figure 2.20), albeit with performance in numeracy lagging that in literacy and problem-solving in a technology-rich environment. However, the younger age group’s (16-24 years) skills compare less favourably with those of their peers in other countries than do the skills of older age groups. A factor that contributes to mediocre skills of the younger age group is that achievement increases less beyond lower secondary education than in most other countries. When comparing the literacy achievement of the cohort of individuals who were 15-year-old students in 2000 (2003 for New Zealand and three other countries to which the OECD PIAAC study was extended in 2015) and 26-28-year-old adults in 2012 (2015 for New Zealand and the other three countries), literacy achievement in New Zealand grew by 5 points on the PIAAC scale, which was less than the OECD average growth of 13 points (OECD, 2021[71]). Achievement growth for high performers in PISA was one of the lowest among participating countries (ibid, Figure 3.9). On the other hand, engagement in adult learning, which can reduce the loss of foundation skills owing to ageing, is high in New Zealand, which may help to explain the relatively strong performance of older age groups. The proportion of adults who do not participate in adult learning and report being unwilling to participate in the learning opportunities that are currently available to them (i.e. they are disengaged from adult learning) is 28%, far below the OECD average of 50% (OECD, 2021[71]). Workers who obtained a tertiary qualification are 14 percentage points less likely to be disengaged than workers without a tertiary qualification, a difference that is less pronounced than it is on average among OECD countries (ibid).

Note: Individuals with a well-rounded skill set score at least Level 3 (inclusive), out of 5, in literacy and numeracy and at least Level 2 (inclusive) in problem solving.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2012) and OECD (2015), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC).

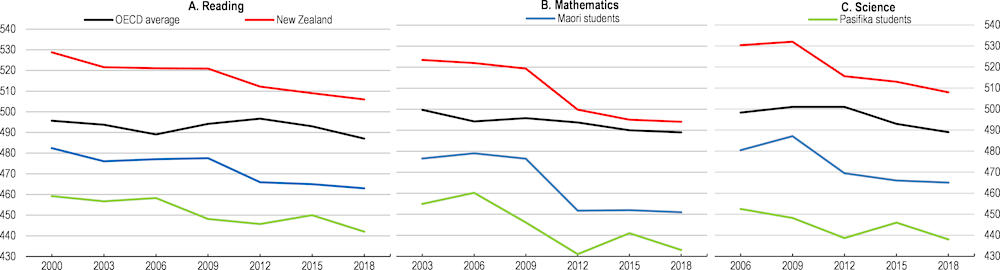

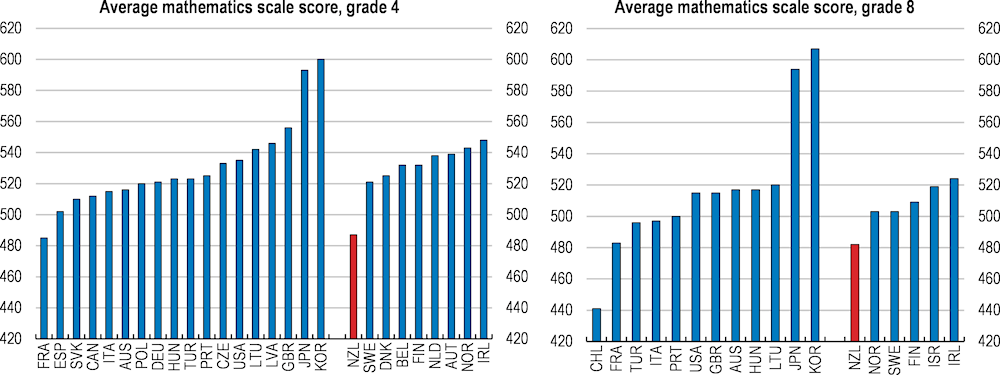

The corner stone for building information-processing skills and the foundations for lifelong learning is initial education. One indicator of the progress made by students at 15-16 years of age is achievement scores in the OECD PISA study, which are correlated with PIAAC scores and are a strong predictor of success at the tertiary level of education (OECD, 2016[72]). Achievement has been declining since PISA tests began (the average three-yearly trend is negative and statistically significant), although New Zealand scores remain above the OECD average and still rank relatively highly (6th – 12th rank range) amongst OECD countries in reading and science (Figure 2.21). The decline since 2009 reflects an increased share of low performers (below Level 2) and a reduced share of high performers, albeit to levels that are similar to those in countries with average scores that are not significantly different from New Zealand’s (Figure 2.22). The increased share of low performers, which is over 20% in mathematics, is serious as they do not demonstrate the competencies that are needed to participate effectively in life as continuing students, workers and citizens. Similarly, the decline in the share of top performers is a problem as this group has acquired the foundation skills at an early stage of their education that are needed to be well equipped in the digital era (OECD, 2020[1]). Māori and Pasifika achievement has also declined since PISA tests began and continues to lag well behind that of the rest of the population. The influence of socio-economic background on scores is similar to the OECD average but is higher than in the other English-speaking countries except the United States, for which the difference is not statistically significant (Figure 2.23).

Note: Individuals lacking basic skills score at most Level 1 (inclusive) in literacy and numeracy and at most Below Level 1 (inclusive) in problem solving (including failing ICT core and having no computer experience).

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2012) and OECD (2015), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC).

Source: OECD, PISA database ; (May, Jang-Jones and McGregor, 2019[73]), PISA2018, New Zealand Survey Report

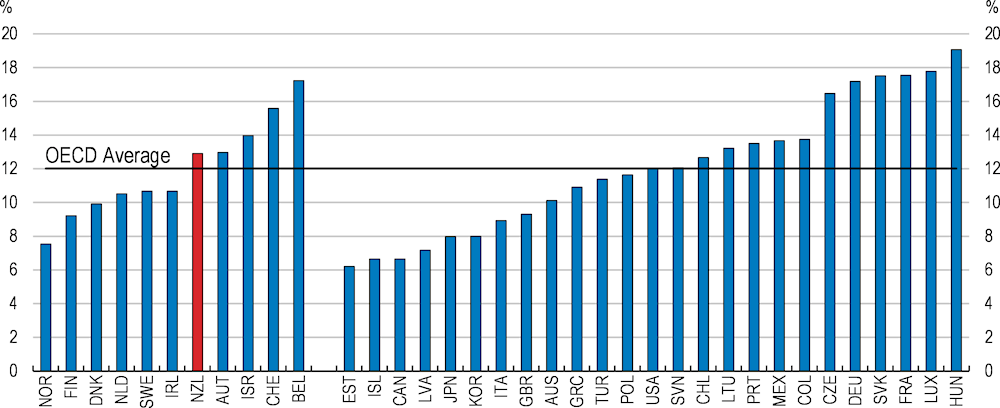

Achievement issues are most pronounced in mathematics, where the average PISA score is only just above the OECD average and there is a larger tail of low performers than in the other subjects. Weakness in mathematics is corroborated in the TIMSS study by Mullis et al. (2020[74]), which tests mathematics knowledge and assesses students’ ability to use it and apply mathematical reasoning in a range of problem-solving situations. New Zealand scores at Grades (referred to as years in New Zealand) 4 (year 5 in New Zealand with students aged around 10 years) and 8 (year 9 in New Zealand with students aged around 14 years) are lower than in other English-speaking countries and indeed lower than in all other participating OECD countries except Chile and, at Grade 4, France (Figure 2.24), and have fallen significantly at Grade 8 since New Zealand first participated in the TIMSS study in 1994. New Zealand’s National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement (Darr et al., 2018[75]) showed that in mathematics most children were achieving at the curriculum level expected of them in year 4, but by year 8 only 45% were doing so. Concomitantly, less than half of students at year 8 are on a trajectory to reach the required level at year 12 to continue their education at the tertiary level in any field requiring mathematics competence.

A key reason for New Zealand’s poor equity and achievement outcomes is that, since the Tomorrow’s Schools reforms in 1989, schools have predominantly operated as autonomous, self-managing entities, loosely connected to each other, and with a distant relationship with the centre (Ministry of Education, 2019[76]). This has left schools to operate largely on their own and without sufficient support. Moreover, School Boards of Trustees, which are largely composed of unpaid elected parents, have often struggled to perform the wide range of complex roles required of them, including appointment and performance reviews of principals. This has been a greater problem in more disadvantaged communities than others. In light of these problems, the government decided in 2019 to strengthen support networks in the school system and to make them more responsive to the needs of students and their families. The first plank of the government’s reform to the Tomorrow’s Schools framework is to rebalance the Ministry of Education towards more regional and local support, through the establishment of a separately branded business unit within the Ministry of Education, the Education Service Agency (ESA), which will lead a programme of substantial service level transformation. The second plank is to strengthen the arrangements that underpin principal leadership of schools. This includes inviting the Teaching Council to establish a Leadership Centre, a new role of Leadership Advisor, and the establishment of eligibility criteria for appointments to school principal roles so that all schools have leaders with the right skills and expertise. The government also plans to strengthen incentives for the most capable principals to work in schools with the greatest challenges, which tend to be schools where children predominantly come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Third, the Ministry of Education will reduce the burden on school boards by simplifying or removing infrastructure management and maintenance responsibilities and centralising key services, such as planned and preventative maintenance.

Variation in student performance explained by socio-economic background1, 2018

1. PISA index of economic, social and cultural status. See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: OECD, PISA database

Note : See Figure 2.1, note 2 for the definition of small advanced economies.

Source: Mullis et al. (2020), TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science