Sahra Sakha

OECD

Yosuke Jin

OECD

Sahra Sakha

OECD

Yosuke Jin

OECD

While Romania’s speed of convergence to the average income levels of the OECD has been impressive since the early 2000s, significant gaps to higher income countries remain. This mostly reflects the poor performance of domestically-oriented firms, with a large and increasing productivity gap between exporting firms and domestically-oriented ones. To reinvigorate productivity growth in the domestic business sector, structural reforms are needed to address three main policy challenges. Firstly, regulatory barriers to firm entry, especially in professional services, are high and governance of SOEs is poor. Removing impediments to competition and promoting better governance are vital to boost productivity growth. Secondly, reforms to reduce inefficiencies of the insolvency regime and the judicial system are urgently needed to facilitate the exit of non-viable firms and restore a dynamic business environment. These challenges have become even more imminent following the COVID-19 crisis, which most likely requires some reallocation of activities. Thirdly, poor quality of transport infrastructure exacerbates regional disparities and undermines economic prosperity. Increasing public investment through improved absorption of EU Funds is essential to close infrastructure gaps.

Romania’s speed of convergence to the average income levels of the OECD has been impressive over the past decades, boosted by significant policy reforms related to EU accession in 2007 (see Chapter 1). Privatisation and restructuring of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), regulatory and judiciary reforms, and access to EU structural funds contributed to high productivity growth. Between 2010 and 2019, labour productivity growth averaged 3.5% in Romania, while the OECD average was 1.0%. Moreover, the opening of Romania’s economy to international trade, its integration into global value chains, and increased foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly in manufacturing and knowledge-intensive services (i.e., Information and Communications Technology (ICT) sector), contributed to productivity growth by bringing in new technologies, modern processes and access to external markets (Altomonte and Pennings, 2009; World Bank, 2018). The Romanian ICT sector considerably grew over the past 10 years, accounting for 7.0% of gross value added in 2020 (up from 4.4% in 2010) or EUR 13.8 billion.

While Romania’s productivity growth has been strong, significant gaps with higher income countries remain. Romania is at risk of falling into the middle-income trap, according to which economies stagnate and fail to graduate into the ranks of high-income countries (Aiyar et al., 2013). Despite the rapid expansion of knowledge-intensive sectors, like many emerging markets, the Romanian economy retains a dual structure. Innovation is concentrated among multinational firms with high integration in global value chains. Those high-productivity firms coexist with low-productivity domestic (including informal) firms. This poses a challenge to further productivity growth due to the weak capacity of domestic firms to absorb technology, despite the large presence of multinational firms. Following the COVID-19 crisis, the digital transformation of the economy has accelerated, which can be an opportunity to boost investments and productivity, but a challenge for laggard firms that will be at the risk of lagging further behind if they fail to adopt technologies (OECD, 2021a). In this context, the necessity to strengthen market discipline and the reallocation of resources across firms has become all the more important.

Key measures to lift productivity growth are essential to boost economic prosperity. In this context, the chapter investigates recent trends of Romania’s productivity performance. It then examines policy reforms to lift the performance of the business sector. Policies that promote favourable business dynamics, allowing productive and innovative firms to thrive, such as competition policies, access to finance, judicial system and insolvency regimes are crucial in this regard. Better transport infrastructure plays a critical role in the transition from a middle- to high-income economy as it addresses social and territorial imbalances and improves enabling conditions. Labour market policies that increase employment, influence incentives for workers or firms to invest in training, and improve the quality of job matches, also affect labour productivity and are discussed in Chapter 3.

Starting from the mid-1990s, the Romanian economy underwent major structural transformations from heavy industries to manufacturing and services. Romania has attracted large FDI flows since the EU accession, which were directed to large multinational companies and boosted highly-productive sectors such as the ICT sector. Multinational enterprises mainly contribute to the ICT sector, as they account for 73% of total revenue in the sector. In contrast, the vast majority of local firms are small, domestically-oriented and unproductive. In addition, the size of the shadow economy is large, estimated to be roughly between 26-30% of GDP, which limits growth and productivity performance (Medina and Schneider, 2018).

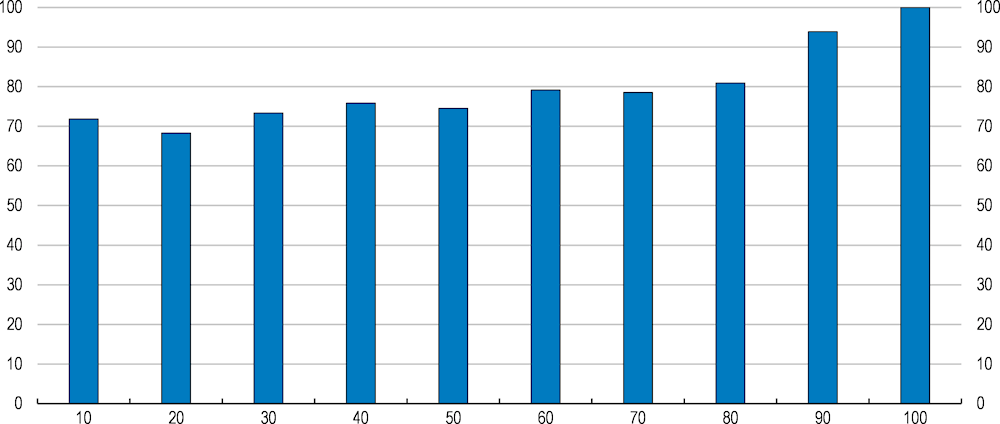

Most of Romanian firms are small and their productivity is low on average. Out of 501 974 total companies operating in Romania, 99.7% were SMEs (0-250 persons employed) in 2018, which is similar to the EU average, according to Eurostat’s Structural Business Statistics. However, the shares of small firms (10-49) and medium sized firms (50-249) in Romania are almost 1.5 times and twice as high as the EU average. Their productivity is considerably lower than that of large firms (Figure 2.1).

Median labour productivity by size distribution, index (highest decile) =100, 2015

Note: The figure shows the median labour productivity of firms in different deciles of the firm size distribution in Romania. The X-axis shows the firm size distribution and the Y-axis the median labour productivity relative to that of the highest decile.

Source: Authors’ calculation using the 6th Vintage of the CompNet database, full sample.

The Romanian economy portrays a dualistic feature between domestically-oriented and exporting firms. Romania’s economy is open, as the trade-to-GDP ratio has risen to 85% in 2019, up from 48.5% in 2000, with around 85% of exports going to the rest of the EU (see Chapter 1). However, the share of exporting firms remains low in Romania. For instance, the share of exporting firms with at least 20 employees in the manufacturing sector stands at 31.8%, much lower than in peer countries such as Slovenia (84.8%), Slovakia (81.0%), Estonia (74.7%), Poland (61.2%), and Hungary (48.1%) (Berthou et al., 2015).

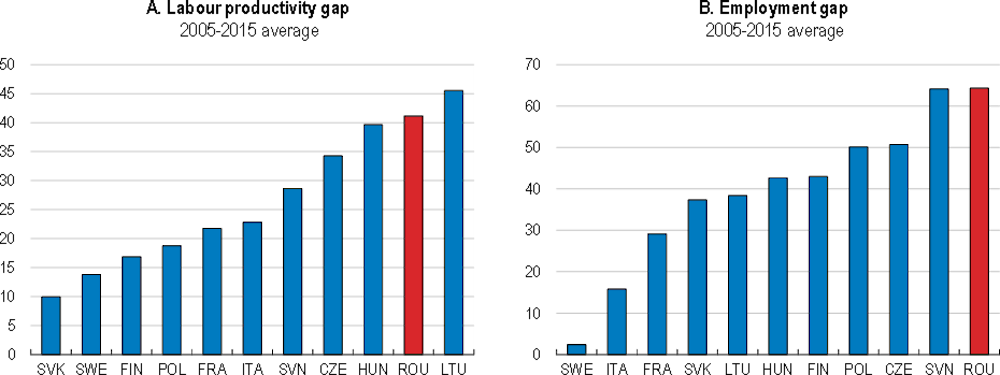

In contrast, exporters are substantially larger and more productive (Figure 2.2). A large share of employment (53%) and value added (69%) is generated by large exporting firms (Berthou et al., 2015). Between 2005 and 2015, exporters were 40% more productive than non-exporters in Romania, a higher gap than many other EU and peer countries (i.e., Poland, Slovenia). They were also 60% larger and are 10% more capital intensive compared to purely domestic firms over the same period, which in turn reflects a better allocation of resources, contributing to raising aggregate productivity (National Bank of Romania, 2016).

Despite EU market integration, benefits in terms of technological and knowledge spill-overs have been limited. Romania’s domestically-oriented firms are still smaller, less integrated in global value chains, less capital intensive and tend to specialise in low value-added activities (Altomonte and Pennings, 2009). These characteristics limit their capacity to absorb technology diffusion, making them difficult to make the most of the openness of the Romanian economy and the presence of many multinational enterprises in Romania.

Note: In Panel A, labour productivity gap in % is calculated as log differences in labour productivity of exporters and non-exporters in the same industry between 2005 and 2015. In Panel B, employment gap in % is calculated as log differences in the number of workers of exporters and non-exporters in the same industry between 2005 and 2015. Industry-level values are transferred to the country-level by taking simple un-weighted average over industries. Industries defined at NACE 2-digit level.

Source: Authors’ calculation using the 6th Vintage of the CompNet database, 20E Sample, Trade module.

The prevalence of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) continues to be important in the Romanian economy. At the end of 2018, there were 225 central-government-owned SOEs (down from 247 in 2013) and a total of 1 231 local-government-owned SOEs in Romania, the majority operating in the energy and transport sector (European Commission, 2015; World Bank, 2020). In terms of the employment share and equity valuation, Romania’s SOE sector is higher than in some of its OECD peer countries, most notably the Baltic countries, but lower than in Poland and Slovenia for instance (IMF, 2019a).

The vast majority of SOEs are heavily indebted with poor profitability, although some SOEs are highly profitable (World Bank, 2020). The companies generating the largest profits are all in the energy sector, while companies in the transport sector are generating the largest losses and receive the largest share of subsidies. In addition, Romania’s SOE-dominated transport sector seem to deliver poor output quality, ranking bottom of other emerging economies (Böwer, 2017). The prevalence of so many SOEs reduces aggregate productivity as it can distort the allocation of productive resources across firms (Hsieh and Klenow, 2009; Bartelsman, Haltiwanger and Scarpetta, 2013). It can deter market entry and expansion of young firms, diffusion of technology and, thereby, long-run aggregate productivity and welfare (IMF, 2019a).

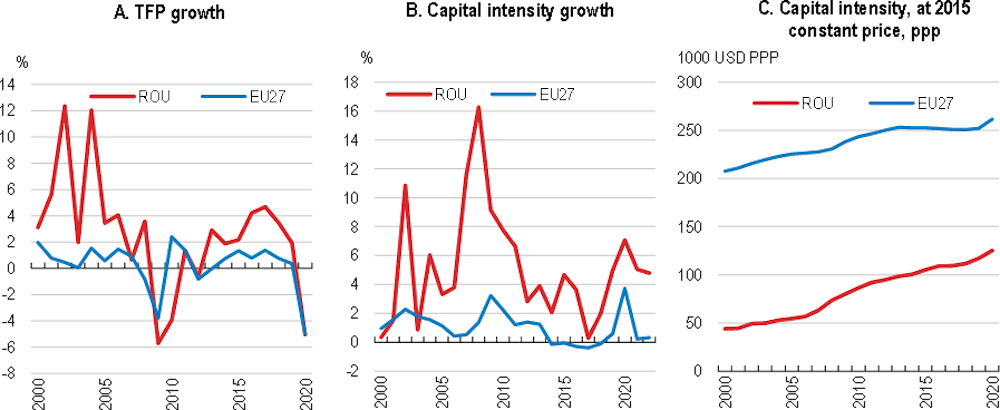

Romania’s growth performance has been underpinned by strong factor accumulation and productivity growth (Figure 2.3, Panel A, Panel B). Both capital intensity and total factor productivity have grown stronger than in other EU countries. However, both capital intensity and productivity have slowed over the past decade. As the process of convergence has progressed, one can anticipate a slowdown in factor accumulation. However, capital intensity in the Romanian economy remains far below the frontier (21% of the EU average in 2000, reaching to 48% in 2020: Figure 2.3, Panel C). It is essential to restore the momentum to increase capital intensity, which is key to technology diffusion (OECD, 2019a). Structural reforms, improving the business environment and the quality of institutions, would help to restore such a momentum and avoid the risk of falling into the middle-income trap.

Note: Capital intensity is defined as net capital stock per person employed. It is measured in 2015 USD PPP in Panel C.

Source: The Secretariat’s calculation based on the European Commission AMECO database.

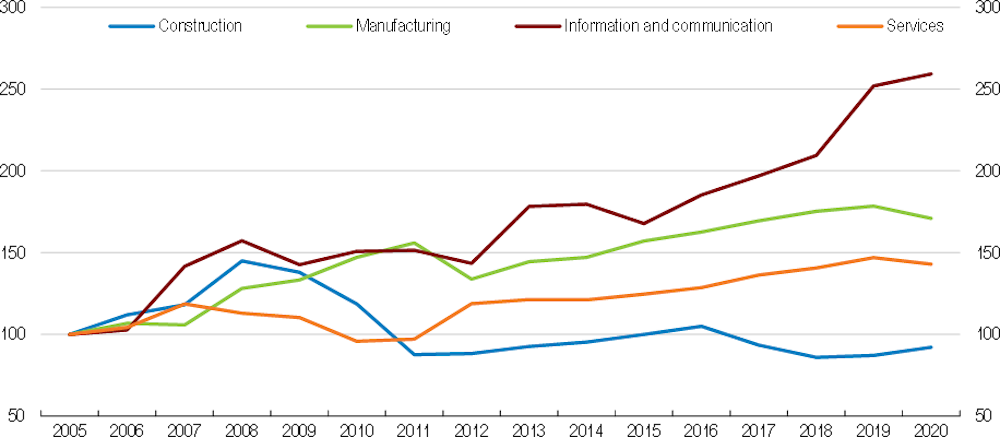

Productivity developments have been heterogeneous across sectors (Figure 2.4). It has been particularly strong in the ICT sector, exhibiting positive growth even during the COVID-19 crisis. Both manufacturing and services have grown steadily prior to the COVID-19 crisis, but contracted somewhat in 2020, as these sectors have been adversely hit due to the containment measures. As the economy re-opens after the crisis, productivity growth in these sectors is expected to regain momentum. However, the crisis may have affected productivity developments across sectors disproportionately. Notably, some sectors most affected by physical distancing requirements and associated changes in consumer preferences may be permanently smaller after the crisis (OECD, 2020a). This implies that, unless they adjust employment accordingly, these sectors will face productivity decline while hampering the reallocation of resources, weighing down productivity at the aggregate level.

The rising importance of services in the Romanian economy implies that future overall productivity performance will largely depend on the productivity performance of the services sector. As countries catch up, the share of the service sector contributing to economic growth increases. Services, especially wholesale and retail trade, have been growing in recent years, reflecting strong domestic demand. Services have on average lower productivity growth than manufacturing, related to lower tradability of the services sector and lower levels of automation (Sorbe, Gal and Millot, 2018). This implies that restoring technology diffusion to sustain productivity growth is essential. This bears more importance following the COVID-19 crisis, since the productivity divergence between productive firms and less productive ones risks deepening, due to disparities in the adoption of digital technologies (OECD, 2021a).

Index 2005=100

Note: This chart shows the evolution of labour productivity growth computed as real value added per worker (in Euro’s) on the aggregate sector level (sectors at 1-digit corresponding to the NACE REV.2 sections).

Source: Eurostat.

Romania’s labour productivity has also been heterogeneous across regions (Figure 2.5). Productivity is high in the Bucharest-Illfov region, primarily driven by the knowledge-intensive service sector. The city is hosting the country's top academic institutions and provides a well-developed ICT infrastructure (i.e. high-speed infrastructure), exhibiting the highest research, development and innovation potential in the country. The most dynamic regions, Nord-Vest and Vest, with a booming ICT sector in cities such as Cluj-Napoca and Timisoara, have outpaced Bucharest in terms of productivity growth. The South West and Eastern part of Romania (Sud-Vest Oltenia and Nord-Est) are lagging behind in productivity levels. Given shortcomings of the transport infrastructure in many lagging regions, improving connectivity through appropriate transport links between cities and regions is a key priority to reduce regional disparities in productivity.

Valued added per employed person, 2019

Sizeable productivity differences across sectors, notably in services may be related to the lack of a dynamic business environment, which plays an important role as an engine of productivity growth through the process of creative destruction. It enables new, productive firms to enter the market, grow and replace old, unproductive ones and thereby introduce new ideas and technologies to the market place. Therefore, policies should aim at fostering business dynamism (Bartelsman, Haltiwanger and Scarpetta, 2013; Arnold, Nicoletti and Scarpetta, 2011).

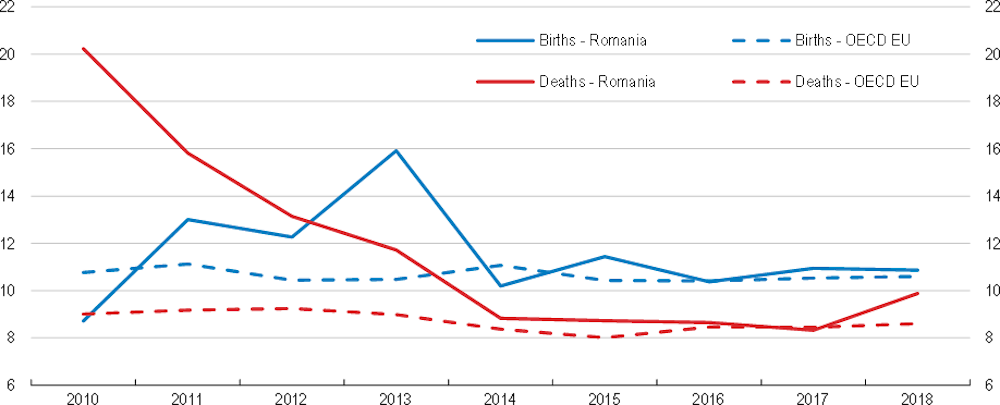

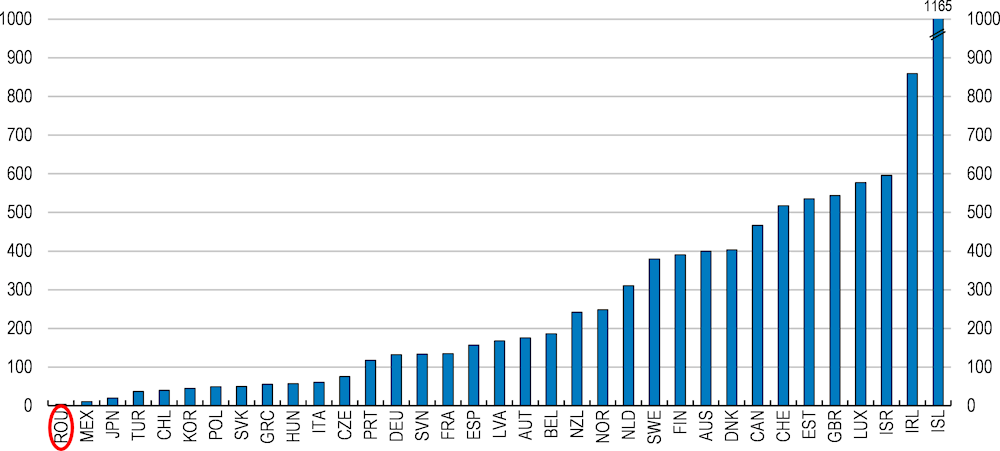

Although the overall firm entry rate is relatively high, the creation of highly innovative firms seems to be low. Firm entry rates in the 2010s were somewhat higher than the EU average (Figure 2.6). However, Romania ranks lower than the lowest-ranked OECD country in the creation of, innovative and tech-intensive start-ups (Figure 2.7), despite the strong performance of Romania’s ICT sector and the provision of good digital infrastructure in urban areas. Romania’s start-up scene displays high growth potential and has been recently recognised internationally (e.g. Forbes).

In addition, Romania’s business dynamism has been declining in the 2010, in particular for firm exit (Figure 2.6). Declining firm exit could be an indication that the selection of the firms at the entry has become increasingly efficient. However, a high survival rate of old firms that are constantly unprofitable and financially distressed suggests that the market selection mechanism is weak. The survival of such firms may further drag down average productivity, since they take up scarce resources at the expense of more productive firms (Adalet McGowan, Andrews and Millot, 2017). A new law was introduced in 2020 (Law no. 55/2020) following the COVID-19 crisis, which has contained a significant rise in insolvency cases, along with other measures such as the moratorium of private loans (see Chapter 1). Going forward, the application of this law should be strictly targeted to those affected by the pandemic in a transitory manner, in order to target those facing short-term difficulties in liquidity due to an unexpected event, distinguished from those truly facing solvency problems.

As a percentage of existing firms in a given year

Note: OECD EU consists of European countries that are members of the OECD.

Source: Eurostat, Business demography statistics.

Number of start-ups per million inhabitants, 2018

Note: This figure uses data from Crunchbase, a popular online platform that connects venture capitalists with seed stage start-ups. This platform is increasingly used by the venture capital industry as the premier data asset on the tech/start-up world. USA has been excluded from the database due to large sample size.

Source: Crunchbase.

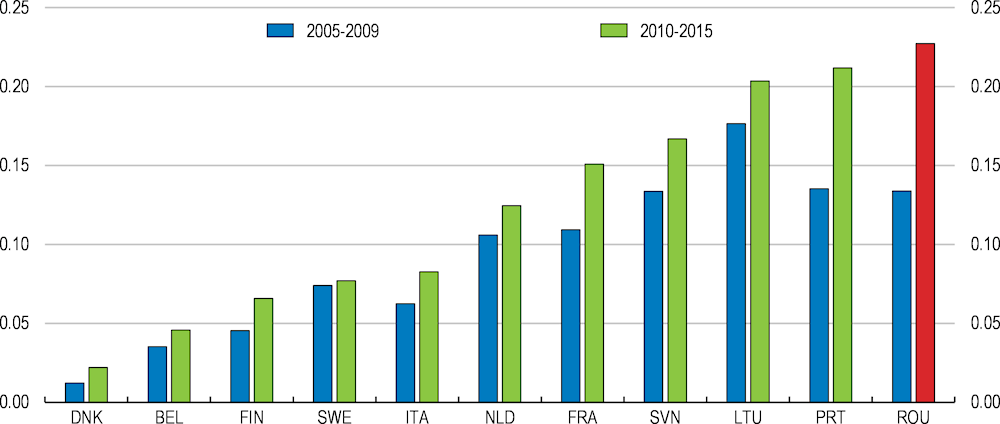

Romania has the highest survival rate of unprofitable firms – defined as firms with negative operating profits for three consecutive years – compared to high-income EU countries and its peers (Figure 2.8). In 2015, 20% of all Romanian firms covered in CompNet (76% of the population of all firms) fell into the category of unprofitable firms. According to the National Bank of Romania, 67 500 companies (31.3% of total 215 900 companies that reported their financial statements to the Ministry of Finance) were loss-making in 2019. Some of them are likely to have made losses continuously over the years. Moreover, 2-3% of firms have reported zero turnover constantly over the past decade, implying a weakness in the exit margin.

Average share of unprofitable firms between 2005-2009 and 2010-2015

Note: Unprofitable firms are defined as firms with negative operating profits for three consecutive years.

Source: Authors’ calculation using the 6th vintage of CompNet database, full sample.

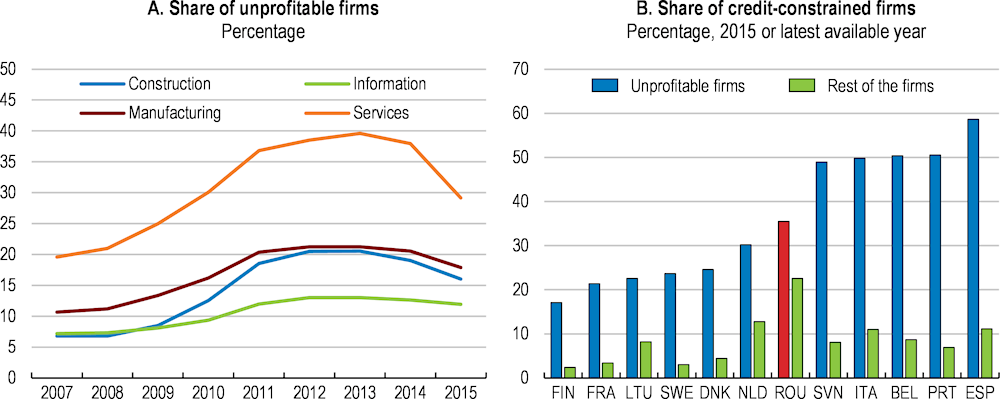

The share of unprofitable firms is substantially higher in the services sector than in the ICT and manufacturing sectors (Figure 2.9, Panel A). The probability of being financially constrained, calculated from their financial position matched with survey data, is higher among unprofitable firms in Romania (Figure 2.9, Panel B). In Romania, the percentage of those firms not classified as ‘unprofitable’ but still facing financial constraints is higher than in other countries. This suggests that access to finance may be a broader issue.

Note: Unprofitable firms are defined as firms with negative operating profits for three consecutive years. In Panel B, data refer to 2014 for France, Italy, and the Netherlands. The credit constraint indicator in CompNet is constructed in three steps. First, firms’ responses in the SAFE dataset about binding credit constraints is linked with the financial characteristics in the Orbis dataset. Once firms are ranked according to the SAFE score, the next step is to set a time-varying and country-specific threshold value of the SAFE score. After matching responses, several indicators of the financial position of the firm on its probability to be credit constrained is estimated using a probit model. The third step is to use the coefficients of the estimated probit regression to compute a predicted constrained score for the firms in the CompNet dataset, depending on the value of their financial position indicators.

Source: Authors’ calculation using the 6th vintage of CompNet database, full sample.

Overall, access to finance remains limited. This mainly relates to low financial intermediation (Figure 2.10), affecting particularly SMEs in rural areas. The financial sector is dominated by banks, which accounted for 76.1% of financial assets in 2020. Following the COVID-19 crisis, the credit standards were tightened in particular for SMEs and have been eased at different paces between large firms and SMEs (National Bank of Romania, 2021). The credit standards were expected to be easier for large firms in the latter half of 2021. Market-based financing remains underdeveloped despite considerable reform efforts from the Financial Supervisory Authority to increase transparency and ease market access (OECD, 2021b). Finally, private equity, an important pillar in the early-stage start-up ecosystem, represented notably by business angels and venture capital funds, is still nascent.

At a first glance, access to finance does not seem to be a major impediment to the business sector. Large and foreign-owned companies are not credit-constrained because they are able to borrow directly from abroad. SMEs in general do not report financing difficulties, in particular as they resort less to bank financing than larger corporations and rely more internal finance (National Bank of Romania, 2020).

However, SMEs in rural areas and early stage high-tech start-ups seem to have difficulties in obtaining external finance, driven by several demand and supply side factors. On the demand side, it has been reported by international and domestic banks that SMEs may rely more on internal finance because they lack the financial and managerial knowledge to successfully attract finance other than debt and that start-ups lack stable revenue and collateral.

Assets as a percentage of GDP, 2016

Supply-side constraints to financing are low debt recovery rates, related to inefficiencies in the insolvency regime (see below) and the weak balance sheets of Romanian firms (Figure 2.11). Companies with capitalisation below the regulatory threshold (shareholders’ equity should be 50% or more of the difference between total assets and liabilities) account for around 20% of firms in 2019 as reported by the National Bank of Romania. A recent study by the European Investment Bank (Pal et al., 2019) finds that Romania had the second highest share of firms with negative equity within the EU, especially in the microenterprise segment. Moreover, a large share of liabilities consist of intercompany arrears and trade credit. In 2019, 18.4% of total liabilities and equity are trade debt, while loans from banks and non-bank financial institutions were a secondary source (National Bank of Romania, 2020).

Percent, 2019Q3

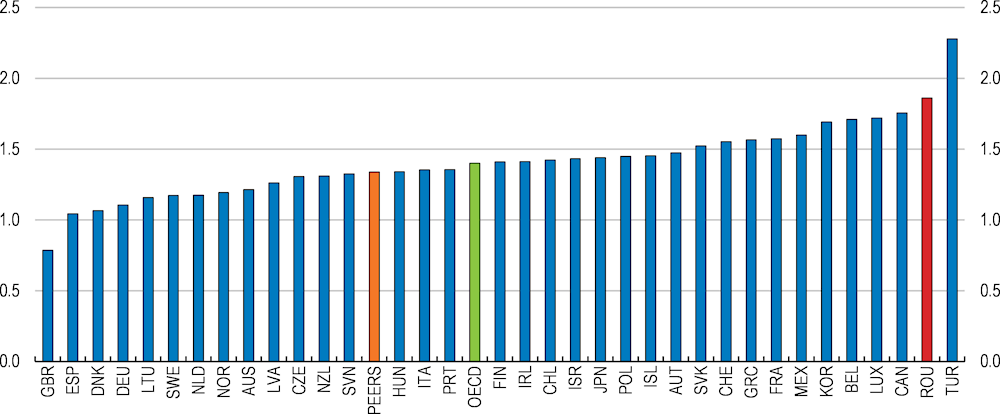

According to the OECD Product Market Regulation Indicators – measuring the de jure competition-restrictiveness of product market regulations across a wide range of countries – Romania tops the list of countries with restrictive product market regulations (Figure 2.12). This hampers prospective firms from entering and growing unimpeded in the market, weighing down market discipline and innovation (OECD, 2015a). Restrictive product market regulation also raises business costs (OECD, 2015a), which can result in higher mark-ups.

2018, index scale 0-6 from least to most restrictive

Note: PEERS comprises the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Poland.

Source: OECD (2018), Product Market Regulation Database.

OECD estimates suggest that GDP per capita could increase by 4% in the long run, if Romania were to align its product market regulation to the OECD average (see Chapter 1). The largest benefits would accrue from two pillars, namely reducing state control and improving the governance of state-owned enterprises, as well as reducing barriers to entrepreneurship, especially for professional services, which seem to be particularly high (Figure 2.13). By contrast, Romania’s regulatory framework is particularly competition friendly with regard to trade and investment. Barriers to FDI, for example, are substantially below the OECD average (Figure 2.13). In addition, EU citizens have the same propriety rights as Romanian nationals.

2018, index scale 0-6 from least to most restrictive

Aside from low barriers to trade, the statutory corporate tax rate in Romania is low by international standards (Figure 2.14). Romania recently introduced a series of measures and exemptions to support SMEs, start-ups and R&D investment. In 2018, the government reduced the special corporate tax rate applying to all microenterprises with one or more employees from 2% to 1% and turnover below EUR 1 million. Until 2017, this was capped at EUR 100 000. A tax rate of 3% applies to microenterprises without employees, provided their turnover is also below the EUR 1 million threshold. Procedures to pay taxes are close to the EU average and have been reduced over the past years (PwC and World Bank, 2018). The authorities plan to revise the taxation of microenterprises, as it is too generous. This plan should be pursued as size-contingent policies, if they are too generous, increase incentives to under-report turnover and profits and reduce firms’ incentives to grow and increase their productivity and profitability.

Percentage, 2020

Note: The corporate income tax rate shows the basic combined central and sub-central (statutory) corporate income tax rate given by the central government rate (less deductions for sub-national taxes) plus the sub-central rate.

Source: OECD Corporate Tax Statistics database.

While the statutory corporate income tax rate in Romania is business friendly, the proliferation of successively amended special taxes has compounded uncertainty in recent years. The government issued the emergency ordinance in 2018 (GEO No.114/2018), without the consultation of relevant stakeholders and impact assessment. The ordinance contained sizable and distortionary sectoral measures and tax increases, for instance on banks, energy and telecommunications, which triggered a strong response from the affected parties and a negative market reaction. Sectoral turnover tax rates increased from 0.1% to 2% for energy and from 0.4% to 3% for telecoms. While the subsequent revisions repealed the tax on banks assets (see Chapter 1), the turnover tax for energy and telecommunications still remains in place, which may have distorted the market and potentially violate EU competition rules (IMF, 2019b).

Efficient business regulation supports firm creation and competition. Economies that have a more efficient business registration process tend to have a higher rate of firm entry and greater new business density (Égert, 2016). For example, Portugal increased the number of entrepreneurs by 17% by introducing one-stop shops in 2005 (Branstetter et al., 2014).

Romania has made some progress over the past years in terms of reducing administrative burden, notably, through the establishment of the National Trade Registry (see below). As they stand currently, however, red tape and complex regulatory procedures for entrepreneurs remain significant in Romania, limiting the incentives to compete and increasing the cost for businesses (Figure 2.13), which can be improved significantly if the planned reforms in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan are effectively implemented (see below).

Romania has already made some progress in reducing administrative barriers by introducing the National Trade Registry to serve as a one-stop shop for starting a business and transferring procedures for registering businesses on an on-line platform since 2012 (European Commission, 2017a). The use of on-line services has increased over time and accelerated significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, where all services were transferred on-line. According to the National Trade Register Office, approximately 35% of new companies used the online registration platform in 2020, which has increased to 37% in the first quarter of 2021. Corporate tax registration takes place simultaneously with company registration at the trade registry. However, new companies choosing to register for VAT must also undergo a separate procedure with the National Fiscal Administration Agency, which issues the VAT certificate (World Bank, 2017a).

While business registration has been significantly simplified and is increasingly performed electronically, administrative procedures following registration and through business operations remain cumbersome. Licensing obligations – such as environmental or fire safety permits and licences – that can add up to business registration, are currently not integrated into a streamlined procedure. This means that businesses have to obtain licences from multiple public institutions, often having to file paper applications. There is limited exchange of information within the public administration and business is asked to provide the same information to different public authorities. It is difficult to find clear and accessible information on the administrative steps that business and investors have to undertake. Moreover, while Romanian legislation provides for “silence is consent”, which could make the application process more predictable, the policy is not applied systematically, thus leaving business waiting for a decision that is often delivered beyond the statutory required period (OECD, 2022).

The government could improve the business environment by developing and promoting a wider and more consistent use of digital business procedures. This step would require streamlining and simplifying administrative procedures, effectively implementing “silence is consent” policies and enhancing electronic one-stop-shops for all business licensing matters and progressively moving to a single point of contact that effectively serves as the unique interface for all procedures from the registration of a business throughout the life of the business. The burden of dealing with multiple institutions should shift from business to a government co-ordinating body that could co-ordinate back-office procedures. The government could also provide incentives by actively promoting the take-up of online business services. For example, it could offer online registration at substantially lower fees than paper-based registration, while abolishing unnecessary fees altogether. Another important tool is public information campaigns to emphasise the benefits of online registration and overcome any conscious and unconscious bias towards electronic certificates.

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP; the Government of Romania, 2021) envisages a number of reforms and investments to improve administrative procedures. These include the introduction of tacit approval, once-only principle asking applicants to provide the same information only once, and the elimination of dual controls and unnecessary renewals for licences and permits. The digitalised platforms that will be set up as part of investments in the NRRP aim to further simplify and reduce the procedures to start and close a business, set up a new one-stop shop for all required licences, and integrate legislative changes on the efficiency and transparency of controls over the activity of businesses (for further details, see the Government of Romania, 2021). As these measures would significantly improve the quality of regulatory procedures, they need to be implemented effectively.

Obtaining construction permits and electricity access is particularly burdensome in Romania and has been frequently mentioned as a major challenge by business representatives. Developers have to consult numerous laws, regulations and websites to identify the documentation required for a building permit application as well as the construction standards they must follow (World Bank, 2020; World Bank, 2017a). The main bottleneck in obtaining electricity connection is the large number of clearances needed from various agencies before the establishment of the connection can start. Romania has a long process for getting an electricity connection, compared to the rest of the EU (World Bank, 2020).

The government should, therefore, urgently reduce the number of regulations needed for construction and electricity connection permits and establish a single focal point for a permit application – a one-stop shop that could coordinate with all the agencies (World Bank, 2017a). Simplification of some of these procedures could be part of an overall business environment reform that would streamline business procedures. Such reform would also reduce difference across the country in terms of speed and ease of processing applications. Expanding electronic platforms throughout the permitting process could also be envisaged to increase transparency and reduce opportunities for corruption.

Despite past reforms by the Romanian Competition Council to reduce entry and price regulations in professional services, access to certain professions and services remains highly restricted by a cumbersome regulatory framework (Figure 2.13). This is the case for accountants, notaries, architects, and estate agents, who are granted a high number of tasks with exclusive rights. Burdensome accreditation requirements apply to lawyers and engineers (World Bank, 2020). Price controls applied to lawyers, engineers, and architects, have also distortive effects on the market. Romania should, therefore, reassess the application of minimum and maximum prices and consider a reform of professional licences to align with OECD best practices (OECD, 2022).

Addressing the underperformance of SOEs requires a strong corporate governance framework. Well-designed governance structures are also needed to address the frequent challenge of undue politically motivated interference in SOEs’ activities. The OECD guidelines on SOE governance (OECD, 2015b) provide an international benchmark of best practices.

Corporate governance rules specific to SOEs in Romania were systematically introduced for the first time in 2011 through the government emergency ordinance (GEO) 109/2011 (European Commission, 2015). This represented a major step in the implementation of the better corporate governance practices, and aimed at depoliticising and professionalising the management of SOEs (Romanian Fiscal Council, 2017). Through improvements in corporate governance and increased liberalisation efforts, Romania has been successful in enhancing the performance of some SOEs, especially in the energy sector, which shows the highest profit among all SOEs. However, the government has reversed the course with Law no. 111/2016, implemented in 2018, by significantly reducing the number of SOEs subject to the reform made in 2011. The significant deterioration in profitability and payment arrears in the SOE sector likely reflects this change (Romanian Fiscal Council, 2021). The National Recovery and Resilience Plan aims at improving the governance of SOEs, in particular, by eliminating all the exceptions made by the above mentioned Law no.111/2016, which should be pursued.

Many SOEs, especially in the transport sector, continue to be managed by line ministries or local governments and display low performance (European Commission, 2015). In both cases, the ownership rights (defined as the power to appoint board members, the power to communicate financial and non-financial objectives to the SOEs, and the right to vote the state’s share at the annual shareholder meetings) are exercised by the relevant tutelary public authority – either the competent line ministry or the competent local authority –, while the Oversight Unit within the Ministry of Finance monitors the performance of the SOEs. Each line ministry has a department supervising the SOEs under its responsibility.

Such an ownership structure is not an ideal setup for avoiding political interference in the day-to-day management nor to avoid conflicts of interest between the state’s roles as enterprise owner and regulator. Moreover, the frequent replacement of management and board members due to changes in ministries, as well as opaque selection procedures for managers and board members, continue to hamper efficient organisational functioning (European Commission, 2015), including the implementation of infrastructure projects (see below). It creates room for favouritism, especially in the absence of a strong regulatory and accountability framework (OECD, 2019c). In terms of transparency, SOEs are legally required to submit financial and economic indicators to the Oversight Unit, which publishes annual reports on the activities of SOEs on their website. In practice, however, there are SOEs that do not fulfil this obligation, as only 123 out of 146 SOEs that have this obligation sent their reports to the Ministry of Finance. As a similar pattern was observed in the previous years, it is not clear to what extent the sanction provisions foreseen in legislation have been binding.

Enforcement of internationally accepted good practices needs to be prioritised in order to depoliticise and professionalise the management of the SOEs, and improve transparency, accountability, and performance. Changing the governance model from towards a more centralised (or at least centrally coordinated) ownership model could help to improve corporate governance; as this has been done in the last 10-15 years in a number of Western European countries and emerging economies (OECD, 2018). Such a framework would allow to monitor and evaluate SOE performance more easily since it would bring stronger accountability with one body evaluating the performance of SOEs, as opposed to being spread over several different ministries.

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan envisages measures to improve both the governance model of SOEs and transparency. It aims to operationalise the Taskforce at the Centre of the Government for Corporate Governance Policy Coordination and Monitoring by the end of 2022, which will be responsible for ensuring competitive selection procedures for the appointment of administration board members among SOEs, while reducing interim/temporary management board appointments by 50% in SOEs at the central level. The Taskforce will also be responsible for monitoring, evaluating and publishing the performance indicators and enforcing sanctions for SOEs non-compliant with key performance indicators. These measures are expected to improve the performance of SOEs substantially and need to be implemented effectively.

Privatisation efforts have slowed down in recent years. The only major privatisation in the last few years was the sale of the largest chemical company Oltchim, while non-viable assets remained in the ownership of the state (World Bank, 2020). Small and unprofitable SOEs continue to operate without economic or public policy rationale. It is, therefore, important to reassess the economic rationale of these SOEs on a regular basis and consider resuming privatisation efforts, which should be backed up by legislation for investment screening and transparent procedures in order to fend off the risk of corruption.

Moreover, compliance with the performance targets should be closely monitored. Non-compliance should be followed by sanctions of varying severity, ranging from additional reporting requirements to administrative measures imposed on SOE boards. Performance benchmarking of SOEs with private and foreign companies can further inform the monitoring process towards more efficient resource allocation. Among OECD countries, Korea applies a particularly rigorous SOE monitoring system, including customer satisfaction surveys and index-based evaluations, which are seen as key factors for the performance of Korea’s SOEs (Park et al., 2016).

Private-sector expertise, international experience, and independent board members are often absent in Romania. For example, Estonia requires board members to come equally from the private and public sectors to secure more private-sector expertise (OECD, 2013) and a number of North European countries have gone beyond this to appoint boards that consist largely or entirely of independent directors. Board members should be evaluated on an annual basis, as is the case in Sweden and the Czech Republic (Regeringskansliet, 2016).

The Romanian Competition Council (RCC) has successfully remained independent, despite political pressure over the past few years. It is involved in all competition fields: antitrust enforcement, merger control, advocacy and sectorial inquiries. With 234 competition inspectors and little turnover, the RCC seems also to be well resourced, above many advanced OECD countries (France: 199; Italy: 126) and its peer countries (Poland: 215), according to annual reports by competition agencies to the OECD on recent developments in 2018. They have a number of tools available, among others, the whistle-blower platform – an online tool that enables any person to signal potential anticompetitive deeds, which has been highly successful (Global Competition Review, 2018). The RCC is also reinforcing its cooperation with foreign competition authorities, showing its ability to manage international cases.

The competition authority is considered to be fairly effective and is regarded as an active enforcer (Global Competition Review, 2019). The RCC imposed in total EUR 90 million in fines in 2018 – four times more than in 2017, which itself marked a six-fold increase compared to 2016. Moreover, the RCC challenged three of the 59 mergers that were notified in 2018, higher than in many OECD countries.

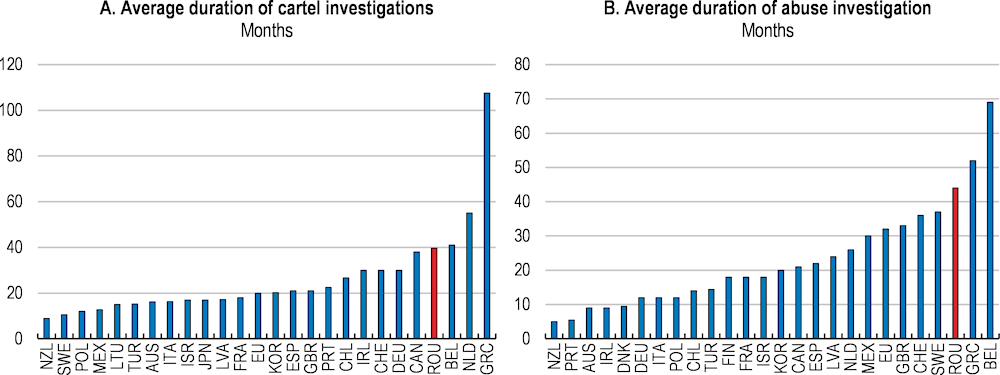

Despite strong policy enforcement of the RCC, the average duration of cartel and abuse investigations is still high, although it has improved in the past few years (Figure 2.15). The allocation of cases among staff remains unclear. A more effective prioritisation policy of cases could help to free up time for high impact cases that are generally more complex and time consuming. The RCC spends around 5% of its budget on advocacy, which is low compared to other major competition authorities (Global Competition Review, 2018). Hence, spending on anti-cartel programmes and the continued promotion of leniency procedures leading to partial or total immunity should be increased. The implementation of the European Competition Network Plus Directive on the better functioning of national competition authorities represents a crucial opportunity to further enhance competition enforcement in Romania, which should be fully seized.

Note: The Global Competition editorial team measures and compares antitrust enforcement programmes around the world, combining data supplied by the agencies with their own reporting and the feedback of lawyers, economists and local journalists who interact with competition authorities.

Source: The Global Competition Review 2018.

Difficulties in accessing finance are extensively recognised as one of the major obstacles for starting and growing a new business, investing in innovative projects, improving productivity, and financing their growth (Heil, 2018). In Romania, a national government strategy for the promotion of entrepreneurship and direct public support programmes are in place. The ‘Start-up Nations’ programme is among such support programmes and provides grants (amounting to 0.13% of GDP in 2018). The programme aims to finance business plans by young firms in a wide range of sectors (from information technology to accommodation), and its beneficiaries are selected by the defined criteria such as job creation. The programme has been suspended since 2020, and the authorities intend to introduce a new programme ‘Star-Tech Innovation’.

The strategy of the ‘Start-up Nations’ programme was not entirely clear. For instance, it was not clear if the programme aimed to support start-ups or if this was instead aimed at promoting specific industries. The new ‘Star-Tech Innovation’ programme is planned to target innovative start-ups. In this case, the programme should address specific market failure such as information asymmetry typically faced by highly innovative start-ups as they are involved in innovation processes with uncertain outcomes. Such a programme should be subject to continuous evaluation in order to ensure that it is strictly targeted to those with high growth potential, Moreover, start-ups do not only require funding, but ‘smart money’ – mentoring, advice, and network, which can be better supported by fully rolling out the other existing programmes to promote entrepreneurship and/or by strengthening the relation with private investors through specific funding schemes (see below).

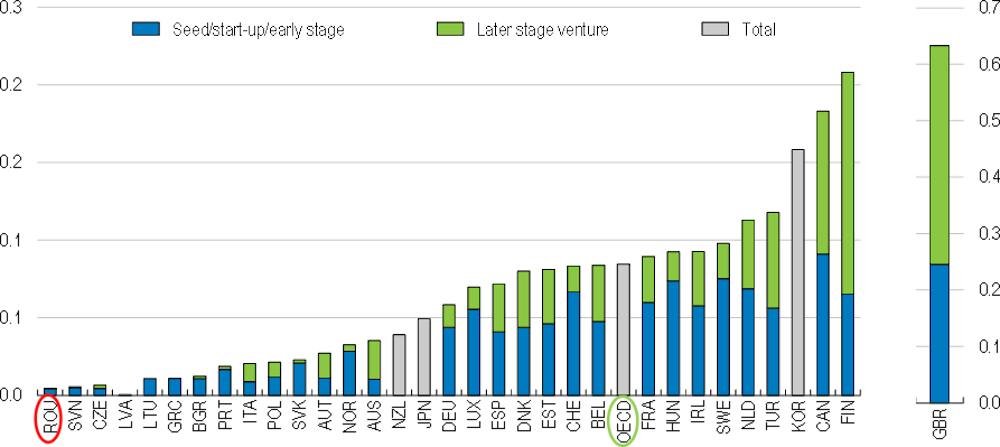

The lack of innovative high-tech start-ups (Figure 2.7) can be linked to the lack of business incubation and acceleration provision in Romania (Figure 2.16). The authorities can consider setting up a public capital fund to co-finance private investors as is commonly found in OECD countries (OECD, 2015c). Such a scheme makes the most of the expertise of private investors with less risk of crowding them out from the market. Alternatively, if they find there are no relevant private funds in the market, such a public fund can finance entrepreneurs directly. There is a successful example in Chile, which has established a public venture capital fund pursuing a long-term vision (Box 2.1).

% of GDP, 2020 or latest year available

Note: 2019 data for Australia, Japan and the United States.

Source: OECD (2021), Venture capital investments (database).

Taking exit through acquisition as a measure of success, almost all of the top 10 successful start-up accelerators around the world are private. The exception is Start-Up Chile (SUC) which was launched in 2010 by the Chilean government. SUC is currently regarded as one of the most successful government-led start-up accelerator programmes in the world, with an overall survival rate of 54.5%. In contrast to many government-led funds, it is open to start-ups from other countries. Companies from 85 countries have participated since 2010. Another crucial factor for its success is that SUC’s goals were long-term oriented, hence not tied to valuations and sales in the short-term but to create a dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystem. Another important aspect was its private-public structure making it less susceptible to changes in the government or policies. Interestingly, it includes a special programme for female-founders. There are three distinct programmes of SUC:

S Factory is a pre-acceleration program for start-ups in early concept stage for female founders from all around the world. Selected start-ups receive around USD 14 000 equity free and 4 months acceleration (i.e. seed investment, connections, mentorship, educational components) that culminate in a public pitch event. After the 4 months, successful start-ups may apply for the seed programme. There are two application rounds per year, selecting 20-30 high potential female founded start-ups in each round. Instead of establishing a gender quota for the accelerator, SUC decided that a supported programme for less experienced female entrepreneurs would have a stronger impact on changing the low female-founded start-up ratio.

Seed is an acceleration program for start-ups with a functional product and early validation. Selected companies receive around USD 30 000 equity free and 6 months acceleration. There are two rounds per year, selecting 80-100 companies in each round.

Scale is the final programme funding top performing start-ups. Selected companies must have passed through the Start-Up Chile seed program initially. They receive around USD 86 000 equity free. There are two rounds per year of 20-30 companies in each round.

Source: https://www.startupchile.org/; (Lassébie et al., 2019).

Microcredit fills a market gap by providing finance to disadvantaged individuals in less accessible areas aiming to start a business. The microcredit sector in Romania is diverse and fragmented, consisting of more commercially oriented micro-finance institutions. The Romanian Microcredit Facility, established 15 years ago, extends loans to microfinance institutions at attractive terms, rather than directly lending to borrowers, and microfinance institutions in turn lend to borrowers (the “on-lender” approach). This approach is effective as long as microfinance institutions cannot raise funds at reasonable costs. A recent assessment by Pop and Buys (2015) notes that the provision of microcredit is highly concentrated within more developed regions where in theory private institutions are able to raise funds in better conditions. The Romanian Microcredit Facility should be assessed in its role and activity and restructured accordingly if necessary.

As part of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), the National Development Bank will be set up and operational as of 2025. According to the NRRP, the Bank will pursue a wide range of objectives from facilitating access to finance for SMEs to funding infrastructure projects and improving the absorption of EU funds. However, at this stage it is not clear what mandates will be attributed to the Bank. If its mandate is to support SMEs generally, it needs to be tailored to their financing needs, which can be done either through the “on-lender” approach or through public guarantee schemes. In both cases, its mandates would need to be articulated with the existing programmes such as the Romanian Microcredit Facility and IMM Invest (introduced as an emergency measure against the COVID-19 crisis, see Chapter 1). If it is mandated to support strategically important areas, strong accountability will be required to explain how investment projects are selected and how the outcomes of its support to investment projects are assessed, thus justifying public support.

A well-functioning judicial system, including a well-designed insolvency regime, is crucial to the allocation of resources and business activities: it enhances the economy’s ability to dispose non-viable firms and facilitate the restructuring of viable ones. It also ensures contract enforcement and facilitates debt resolution, especially in the Romanian context, where many firms have a weak balance sheet structure (high leverage and low equity base). Empirical evidence shows that slow court resolution diminishes the efficiency of credit markets (Fabbri, 2010; Jappelli, Pagano and Bianco, 2005). Other dimensions of judicial efficiency, such as the low predictability of case outcomes, weak incentives for judges (Miceli and Coşgel, 1994), inefficiencies in the allocation of court resources (Palumbo et al., 2013) and weak insolvency regimes can also affect case resolution.

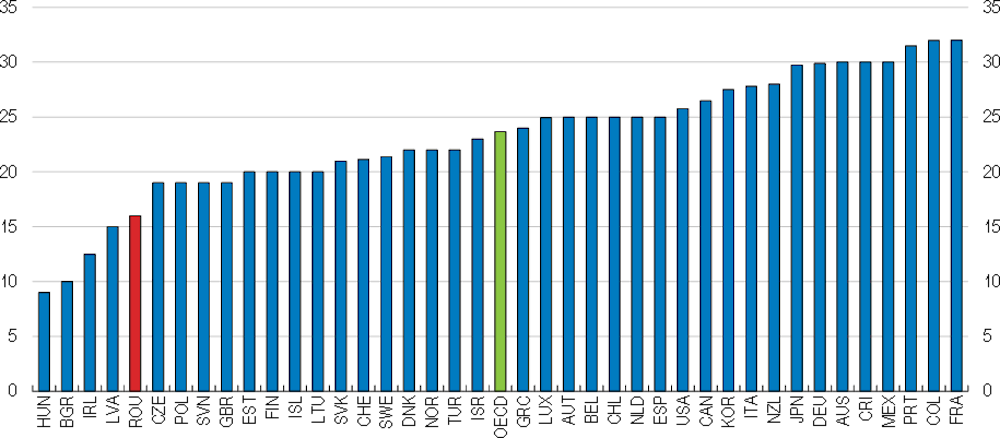

At first glance, Romania shows a below average length to resolve civil and commercial cases before the first instance courts in 2018 (European Commission, 2020). Case resolution, however, differs depending on the type of cases and takes time particularly for bankruptcy cases (including the enforcement process after court sentence), taking 418 days in first instance courts, about 3.5 times as long as civil cases, according to indicators from the Ministry of Justice. The latter indicators also show that the duration of bankruptcy cases has increased between 2016 and 2018, while the resolution trend for civil matters and business cases has remained stable or reduced slightly. Slow resolution of bankruptcy cases is also an issue identified by the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (Figure 2.17).

The average duration of insolvency proceedings is long (3.3 years), compared to peer countries (2.2 years) and the OECD average (1.8 years). While the cost of insolvency proceedings is close to the OECD average, the recovery rate is very low and stands at 34.4%, compared to the OECD average of 67.3%, but also below the peer average (55.8%), indicating inefficiencies in the Romanian corporate insolvency regime and its effectiveness in facilitating the exit of non-viable firms (Figure 2.6).

The resolution rate of bankruptcy cases differs across courts (Figure 2.18). Some courts have a higher resolution rate, even if the stock of judges’ cases is higher. For instance, Bucharest has a higher resolution rate than Covasna or Giurgiu, even though in Bucharest each judge had an average of almost 800 insolvency cases. It seems to indicate that some courts are more efficient than others, although information on the complexity of cases is lacking.

Number of pending cases per 100 inhabitants, as of December 31, 2018

Litigation is frequent in Romania as it had among the highest litigation rate in first instance courts across Europe in 2018 (Figure 2.19). Businesses have repeatedly expressed concerns over the unpredictability of case outcomes, which may have an impact on litigation. For instance, plaintiffs who have weak cases and good information about the likely negative outcome would be more reluctant in taking their cases to court, as they might expect to lose the case. However, if the court outcome is unpredictable, they might decide to bring their cases forward anyway, as there may be some chance of obtaining a favourable outcome.

2017

First instance courts, per 100 inhabitants, 2018

The corporate insolvency law (Law 85/2014) includes modern provisions based on international best practices (World Bank/IMF, 2018), but implementation remains a challenge. The insolvency proceeding ends up with reorganisation or liquidation. In Romania, reorganisations are rare as only 1.2% of companies ended up in reorganisation in 2013, according to the Romanian Association of Banks. Companies enter insolvency proceedings at a late stage, when they are clearly in distress making reorganisation difficult. Small family-type SMEs are even more reluctant to enter into insolvency proceedings. The reasons are manifold, but generally the fear of stigma and bankruptcy is high, as 56% of entrepreneurs report such fear in comparison with 43% in the EU (European Commission, 2013). The fear of stigma and bankruptcy prevails in spite of the possibility of a fresh start directly after bankruptcy (i.e. immediate discharge from debt repayment obligation). The situation can be improved by addressing some specific issues in the insolvency regime, for instance, by introducing early warning tools and developing out-of-court settlement schemes.

Generally, insolvency regimes should encourage debtors to take appropriate actions early on without barriers to initiate insolvency proceedings (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2016). In Romania, insolvency proceedings can be initiated by both the creditor and the debtor. A new law in 2020 removed the restriction that the debtor cannot initiate the insolvency proceedings if 50% of tax claims are outstanding to public creditors, which is a welcome development. While firms, in particular SMEs, often cannot perceive worrying signs related to their business at early stages, early intervention is facilitated by early warning tools as found in more than half of the OECD countries (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2018). Romania should introduce early warning tools by transposing EU Directives on the Restructuring and Second Chance as soon as possible.

Insolvency proceedings are lengthy. Once the debtor or creditor initiates the insolvency proceedings, the observation period starts. A judge who is specialised in insolvency cases notifies the relevant parties (i.e. the debtor, creditors and the National Office of the Trade). The judge will also nominate a judicial administrator who is in charge of producing a preliminary table of creditor’s claims, including their value and priority. All measures taken by the judicial administrator can be challenged in court by creditors and debtors, including the table of creditors. Once challenged, it will again go to the judge, extending the observation period and resulting in long delays, which is restricted to the time limit of 1 year. Moreover, court hearings are scheduled with an approximately 4 month interval, adding to the delays in insolvency cases, which should be shortened to ensure a faster resolution.

Romania includes reorganisation tools regarded as best practices. For instance, debtors can obtain a stay on assets during the restructuring period and continue firm operation. Moreover, unanimous vote by all creditors to agree on the restructuring plan is not required (i.e. possibility of a cram down on dissenting creditors). While priority rules are in place for creditors (i.e. secured vs. unsecured), dissenting creditors within the same priority group are treated equally, which is a best practice (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2016). Nonetheless, recent amendments in the insolvency regime in 2018 through emergency ordinance are a concern, since they provide tax creditors a super-priority rank to claim their assets over other creditors. This superpriority creates little incentive for the tax authorities to participate in debt restructuring, often prolonging insolvency proceedings significantly, and prevents other creditors from claiming the value of investments in case of liquidation, which is also found in OECD countries (for example in Spain; OECD, 2021c). This is one of the main challenges of the restructuring process that insolvency practitioners and other stakeholders report in Romania as well. The government should revise these amendments. The deterioration of assets, due to delays in insolvency proceedings, results often in the liquidation of businesses and bankruptcy of entrepreneurs, in which case the tax authorities cannot claim their rights anyway, making all the parties worse off.

Courts are involved at different stages of both liquidation and restructuring proceedings, such as launching the insolvency procedure, the appointment of the insolvency practitioner, the confirmation and declaration of the restructuring plan and the pre-insolvency mechanisms. While court involvement is important in guaranteeing the rights of different parties involved, a high degree of court involvement may prolong the exit of weak firms, particularly when the judicial system is not efficient (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2016). The government should reduce the court involvement in cases where it is not absolutely necessary, for instance in the pre-insolvency regime. Italy has pre-insolvency regimes in place (Piano Attestato di risanamento), which allows the restructuring of the company with a third party expert without court involvement (Deloitte, 2017).

Two in-court pre-insolvency regimes are currently in place to restructure debt, if the debtor has financial difficulties: preventive arrangement (concordat preventive) and the ad-hoc mandate. However, these pre-insolvency regimes are not effective and rarely used: between 2009 and 2018, only 89 pre-insolvency procedures have been initiated, out of which only seven were successful. Special fast track insolvency proceedings for SMEs, such as simplified or pre-packaged in-court proceedings are currently lacking in Romania. SMEs may warrant a different treatment from other firms in a debt restructuring strategy as complex, lengthy, rigid procedures and required expertise, may entail additional costs (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2018).

Businesses have repeatedly expressed the need for out-of-court mechanisms. Such mechanisms can incentivise debtors to signal their financial difficulties at an early stage, facilitating a speedy and successful restructuring, and reducing the fear of stigma and bankruptcy. Estimates suggest that about 65% of all companies going through an out-of-court procedure in Europe are restructured successfully (European Commission, 2017b). Romania should consider introducing out-of-court mechanisms which have been successfully implemented in a number of countries, such as Austria, Slovenia and Portugal (Bergthaler et al., 2015). A number of countries have introduced simplified procedures for SMEs in their general insolvency regimes, such as Portugal, Germany, Greece, and Italy (Bergthaler et al., 2015).

Frequent changes of the law contributed to unpredictability of case outcomes. Romania has made significant progress in implementing judicial reforms. However, frequent political interference and legislative changes are a concern (Box 2.2). Notably, hundreds of Government Emergency Ordinances (GEOs) have been issued in recent years, raising concerns about their excessive use, lack of transparency and insufficient respect of the rule of law (Council of Europe, 2019). It is imperative to reduce the unpredictability of case outcomes by limiting the use of emergency decrees. Emergency decrees should only be used exceptionally. A proper assessment should be made before implementing new laws in consultation with major stakeholders, to avoid frequent changes and amendments in the law which increase the unpredictability of case outcomes.

Unpredictability of case outcomes may also be related to inconsistency in the judges’ decision-making. This can be improved, for instance, by revising the evaluation system of judges. In Romania, judges are evaluated periodically by the Court President and two judges appointed by the Superior Council of Magistracy. Judges are evaluated both on quantitative and qualitative criteria, such as the resolution and duration of cases and the quality of legal documents drafted. The evaluation of judges can take into account the consistency of case-law, which however needs to be balanced against the risk of affecting the independence of judges. Instead, the consistency of case-law can also be ensured at the institutional level. In this respect, the Superior Council of Magistracy, the supervisory body of the judiciary, is encouraged to identify and resolve divergent interpretations of lower courts.

In order to improve the quality of judicial decisions, legal assistance to judges by other professionals can be strengthened. For instance, court fees seem to be complex and judges in Romania report spending unnecessary time reviewing complaints supposedly due to errors in calculating court fees (World Bank, 2017b). Court staff could be in charge of revising these complaints so that judges could devote more time to solving cases. High court congestion can be reduced by reviewing complex rules and by reducing judges’ duties other than solving cases.

After the communist period, a new Constitution was established in 1991, leading to a reorganisation of the judiciary under the Law on the Organization of the Judiciary (Law no. 92/1992). However, judiciary reforms in the post-transition period were slow, civil society weak and judges still politically connected (IMF, 2017). Fundamental reforms to strengthen civil society and improve judicial independence were performed in 2003 under external influence (i.e. NATO membership and EU accession). The Judicial System Reform Strategy of 2003 entailed, most importantly the institutionalisation of the Superior Council of the Magistracy (CSM) in order to increase independence of justice, by reducing the involvement of the Executive in the appointment and promotion of judges (Coman and Dallara, 2012). The reform process continued in 2015, including changes to strengthen the independence of judges, to increase the efficiency and accountability of the judiciary, and to separate the careers of judges and prosecutors (Council of Europe, 2018).

In spite of these positive developments, there has been room for political interferences in the judiciary and some achievements have been reversed (IMF, 2017). In 2017, different reforms on the judicial system were initiated, raising concerns about the consequences for the independence of magistrates. These include amendments to changes in the statute of judges and prosecutors, on judicial organisation, on the CSM, and legislative proposals to amend the Criminal Code and the Criminal Procedure Code. These changes were implemented in spite of serious concerns with respect to the implications for the independence of the judiciary (GRECO, 2018; Council of Europe, 2019). Subsequently, these amendments have been or planned to be repealed (see Chapter 1).

A relevant policy question is how to improve a judicial system and making it more effective with limited resources, a common concern among countries worldwide. There is no obvious way of doing so, and different policy options, such as increasing spending in the judiciary, the number of judges, increasing salaries, and restructuring the judicial map, resulted in different outcomes. In Romania, the amount of resources in itself does not seem to be a problem, as the number of judges per inhabitant is higher than the EU average (24.6 per 100000 inhabitant versus 21.7) and the court budget as a percentage of GDP is larger (0.27% versus 0.22%). This implies that how to better use resources is likely important than the sheer amount of resources to improve the effectiveness of the justice system in Romania.

Empirical evidence so far does not allow to conclude that increasing the overall budget of the judiciary leads to an improvement in the judicial system unless it is an underfunded system (Cross and Donelson, 2010; Voigt and El-Bialy, 2016). There is no conclusive evidence that an increasing number of judges leads to an increase in resolved cases. Studies from Israeli and Bulgarian courts show that an increase in the number of judges resulted in a decrease in the productivity of incumbent judges (Beenstock and Haitovsky, 2004; Dimitrova-Grajzl et al., 2016). There is some evidence, however, that court output might rise with an increase in judicial staff as in the case of Portugal, for instance (Martins Borowczyk, 2010).

In recent years, a common trend among some European countries has been to reduce the number of courts. France reduced the number of courts in 2008. Courts with low activity (less than 500 new cases per year) were dissolved but each county was still provided with one labour court and one civil court to guarantee access to justice. The total number of judges was kept constant since judges from removed courts were transferred to other courts. At the national level, no effects could be found on the duration of solving cases (Espinosa, Desrieux and Wan, 2017). In 2017, more than 90% of the total expenditure on courts was for wages and salaries of judges and court staff. Romania has the second highest share of salaries in total spending, while few resources remain for training, building infrastructure and digitalisation of the judiciary (European Commission, 2020).

Continuous training is mandatory in Romania and specialised training for bankruptcy cases is available. However, 78% of all judges receive training in judicial ethics (i.e. integrity, knowledge of law) rather than judge craft (i.e. judicial skills in dealing with complex cases, management, etc.), the highest share across EU countries (European Commission, 2020). Almost no training is devoted to IT skills. While perception of bribery is considerably higher among judges in Romania compared to peer countries and EU average (European Network of Councils for the Judiciary, 2017), a better balance between training on judge craft and judicial ethics should be envisaged.

Digitalisation can speed up the resolution of court cases by improving the workload of judges. In 2016, Romania devoted less than 1% of the overall court budget for computerisation (i.e. computers, software etc.), which is lower than peer countries (Poland: 3.1%; Lithuania: 7.7%; Hungary: 1.8%) (CEPEJ, 2018), but has been increasing over the past years to reach 1.5% in 2021. Romania should increase spending to digitalise its court system. Further investments in ICT infrastructure are crucial since evidence suggests that countries devoting a larger share of the budget to ICT have shorter trial length (Palumbo et al., 2013).

Romanian courts have implemented the ECRIS application, covering the workflow of court cases and the STATIS, an IT application facilitating the court management. STATIS generates reports regarding court activity. The reports consider indicators on the age of the cases in stock, the number of pending cases, the number of cases solved, and the average duration of cases. New updates of ECRIS software are under progress to ensure that cases are randomly assigned to judges. However, a proper assessment of the functioning of the judicial system requires further data on courts’ activity.

Data collection could be further improved by incorporating crucial statistics on case complexity at a disaggregated level. A significant challenge for judges is to identify which cases should be prioritised, which cases entering the system have a high degree of complexity and therefore have a higher likelihood of being pending for years and how to address these types of cases (i.e. providing temporary support for judges such as judicial assistants). A well-designed IT tool should take into account such prioritisation, which the new updates of ECRIS software aim to do. It would allow Court Presidents to monitor the progress of cases and to manage them efficiently. It should also be applied nationwide to all the courts, which is also supposed to be ensured by the new updates of ECRIS software.

Infrastructure contributes to productivity and economic activity in many ways. Infrastructure can raise the productivity of private and public sector inputs and the rate of return of private investment, attract foreign direct investment, increase the volume of international trade, and generate positive externalities (such as agglomeration effects; OECD, 2015d). Infrastructure is also central to meet key environmental challenges (OECD, 2019b).

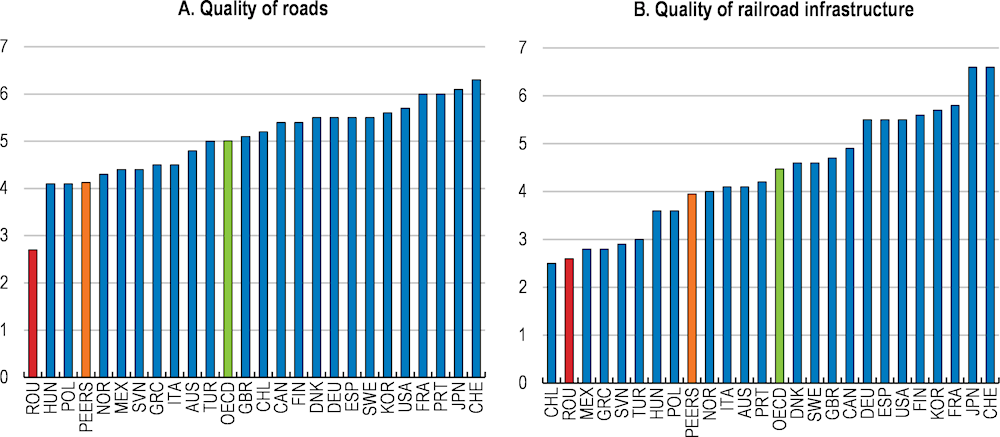

Romania’s transport infrastructure is underdeveloped, with road and rail quality being close to the lowest-ranked OECD country (Figure 2.20). Infrastructure development is slower in Romania compared to peer countries that have similar institutional arrangements, namely a centralised model. Such a model ensures strong coordination among stakeholders, which is considered to be efficient (OECD, 2020b). Therefore, the problems in infrastructure development in Romania likely resides in the implementation of specific investment projects (see below).

The low absorption rate of the EU Structural Funds in conjunction with substantial time and cost overruns contributes to the low quantity and quality of transport infrastructure. So far, Romania has absorbed 63% of the European Structural and Investment Funds allocated to the country over the programming period 2014-20 , with the reimbursements by the EU made until 2023 (see Chapter 1). Over the next programming period 2021-27, a substantial amount of funds is allocated to Romania (up to EUR 30.3 billion, or 13.9% of 2020 GDP from the three funds under the Cohesion Policy). In addition, also a substantial amount of grants will be made to Romania over the next 5 years through the Recovery and Resilience Fund (up to EUR 14.2 billion, or 6.5% of 2020 GDP), which focuses on such priority areas as the environment and digitalisation.

Romania should speed up the absorption of EU Structural Funds, which can help to finance and develop core transport infrastructure projects. For road, the most important transport infrastructure projects using EU Funds, which are currently in progress, include: Lugoj-Deva Motorway; Sibiu-Pitesti Motorway; Bucharest road ring; Sighisoara-Simeria Railway; and Brasov-Sighisoara Railway. These projects contribute to the completion of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). During the next Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-27, investment projects in the transport sector will focus on the continuation of the investments started during 2014-2020, with the main objective of completing the corridors of the TEN-T network that transit Romania, namely the Rhine-Danube corridor and the Orient-East-Med corridor, by finalising the missing sections.

Global Competitiveness Index, scale from 1 to 7 (best), 2018

Note: This is a self-assessed measure asked to business executives. For infrastructure, the following question is asked: “In your country, how is the quality (extensiveness and condition) of road (railway) infrastructure [1 = extremely poor—among the worst in the world; 7 = extremely good—among the best in the world]. CEE consists of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, and the Slovak Republic.

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Index (2018).

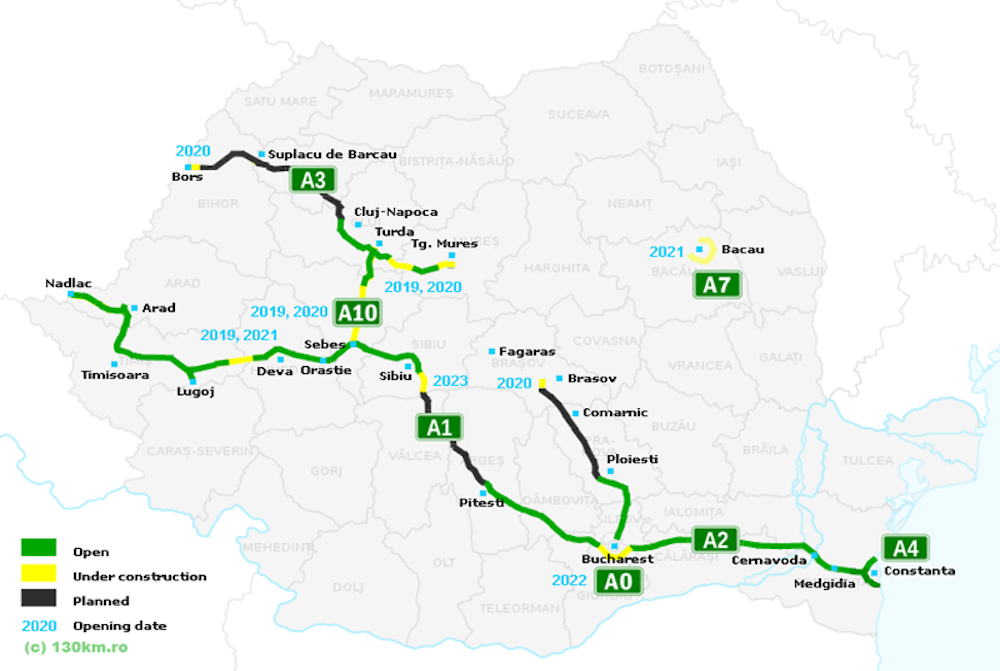

Despite road transport being the principal modality of moving freight in Romania and subject to large EU Structural Funds investments, the state of the road infrastructure remains precarious and is one of the least developed in Europe (European Commission, 2019a). Fewer kilometres of motorway have been constructed than in other CEE countries since joining the EU in 2007. OECD CEE countries have built motorways faster, as the motorway density (motorway kilometres / 1000 km2) in Hungary and the Czech Republic is more than three times as high as that in Romania (Milatovic and Szczurek, 2020).

The most developed motorway, the Pan-European Corridor 4 – ranging from Arad to Constanta – is not finished yet despite available investments from EU funds (Figure 2.21). The Western province of Banat, with its rich city of Timisoara, is the only Romanian region fully connected to the Western European motorway network. Connections between rural regions to motorways are still insufficient, especially Moldova (the poorest region in Romania) (Figure 2.21). Worse yet, the motorway network built around Bucharest is not connected to any other motorway network.

Poor and inefficient infrastructure leads to very low transit freight transportation. Indeed, Romania has not yet taken advantage of its status as a transit country for the southern regions of Eastern Europe. Compared to other EU countries and peer countries, Romania operates small volumes of international traffic, including incoming, outgoing and transit international freight transport (OECD, 2016).

In addition, approximately 90% of the national road network is made up of roads with only one traffic lane for each direction and with very low effective speed (average 66 km/h). This has an impact on both freight delivery time and safety. These roads do not ensure the possibility of overtaking local agrarian vehicles and thus reduce safety for heavy freight transport vehicles, which are the major users of the national road network. Romania is the poorest performer in road safety in the EU. Romania recorded 95 road accident fatalities per million inhabitants, almost twice as high as the EU average of 49 (European Commission, 2019b). A new road safety strategy is envisaged to be implemented as part of the reforms in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

2021

Note: This graph displays the fragmentation of Romania’s motorway.

Source: Romanian Motorway Info, http://www.130km.ro/index_en.html.

Rail freight volume and passenger have declined over the years and is lower than most of the regional peers, including Slovenia, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic (Milatovic and Szczurek, 2020). International railway transport is negligible in Romania, compared to OECD countries, confirming the weak attraction of Romania’s infrastructure for international traffic. This is likely related to the low quality of railway infrastructure (Figure 2.20).

While the country performs well in terms of railroad density, the efficiency and developmental state of train services are very low due to systematic underinvestment and poor maintenance. This leads to a reduced quality of the services provided, one of them being a reduced speed for commercial freight trains (approximately 28.3 km/h) (OECD, 2016). Moreover, only 37% of the rail network is double track, while the EU28 average is 59%. This affects the delivery time of rail freight transport, which is significantly slower than road freight transport in Romania and explains the preference expressed by the business sector for road transportation. Addressing these performance differences would support modal shift towards rail, helping to reduce the carbon intensity of the economy, as stated in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

The Port of Constanţa is the main Romanian sea port, playing a significant role as the transit node for the landlocked countries in Central and South-Eastern Europe. The volume of goods handled here represents more than 95% of the commodities handled in all maritime ports in Romania. Approximately 60% of the goods imported and exported by Romania in 2015 were transported by sea, followed by road and inland waterways according to Eurostat. However, a major obstacle is the transportation of goods to the destination because connections to national roads and rail networks from other ports at the Danube and inland waterways are slow and inefficient. Romania has 30 inland river ports and most of these ports have a poor infrastructure and inefficient connections with other transport modalities, limiting the volume of traffic (OECD, 2016). A development strategy for ports and inland waterway navigation is under development with EU funding and a more integrated approach for investments in the sector is envisaged for the next 2021-27 programming period.

OECD countries’ experience shows that shortcomings in a country’s infrastructure governance jeopardise infrastructure projects’ timeframe, budget and service delivery targets (OECD, 2017). Effective infrastructure governance hinges on a clear regulatory and institutional framework and robust co-ordination across different levels of government (OECD, 2017). Sound governance also increases investment efficiency and productivity, while deterring corruption. By improving the infrastructure governance, Romania can speed up the absorption of EU funds, which would be timely as the allocation of grants from the European Union over the coming years is significantly increased (see Chapter 1).

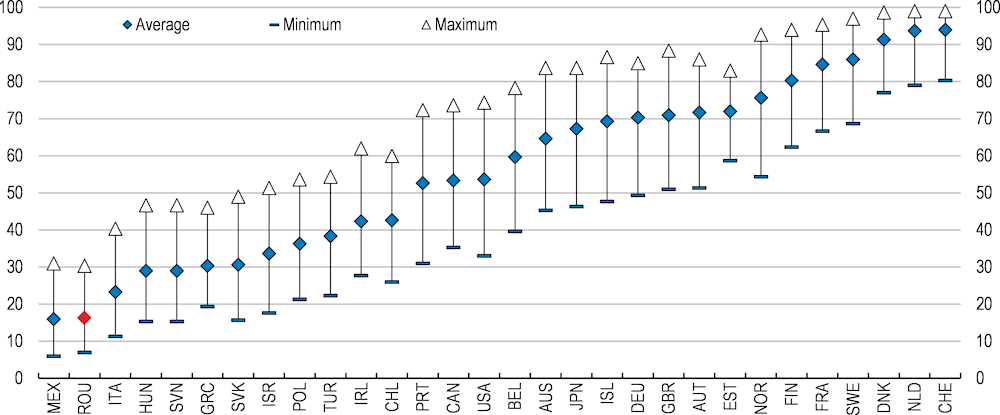

According to a recent study, Romania has weak infrastructure governance, close to the lowest-ranked OECD country (Figure 2.22). The result is largely driven by inefficiency in planning practices and, to a lesser extent, in public procurement. Moving governance quality from relatively low to relatively high standards implies a 0.2 percentage point increase in productivity growth per year on average across OECD countries (Demmou and Franco, 2020). This value is even higher for Romania. Moving from the current infrastructure governance to best practices, Romania could increase productivity growth by 2.3 percentage points in the first year. The positive impact would then fade over time, as Romania will move to higher productivity levels.

Romania has made some progress in improving public infrastructure governance. For instance, the government introduced the General Transport Master Plan in 2016. The Plan defines the objectives of national transport infrastructure and is instrumental for planning major projects and actions. The Plan, with its Implementation Strategy, defines project priorities, their schedules and funding sources. The above mentioned investment projects have been identified as priorities in the Plan. By extending the Plan, the authorities will introduce the Investment Plan 2021-30, focusing political, institutional and financial efforts on a clear set of priorities to the creation of a national transport network.