South Africa has turned towards tourism development to jump-start its weak economy. As tourism is a labour intensive sector that can also bring foreign currency into the country, the sector was identified as priority area by the South African government. Indeed, a doubling in international tourist arrivals from 1995 to 2017 was accompanied by a tripling of employment directly related to tourism. Despite South Africa’s rich and diverse natural and cultural assets, tourism development has been challenged by the country’s geographic location and perceived safety and security issues. As the country is a long-haul destination for many large source markets, good accessibility and international openness is key to expand international tourism, but current visa regulations put an administrative burden on potential tourists. While increasing tourist arrivals are necessary for tourism development, tourism growth has to be well planned and managed to be sustainable. Although the recent coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and resulting containment measures have hit the economy and in particular tourism, the sector has good potential to support the South African economy and contribute to employment growth post-COVID-19. Tourism provides job opportunities for different skills and experience levels allowing for greater social integration. For tourism development to translate into inclusive growth, the tourism industry needs to be integrated into the local economy and the benefits of tourism must spread geographically to also create economic opportunities in less travelled and less prosperous regions.

OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa 2020

3. Leveraging tourism development for sustainable and inclusive growth

Abstract

South Africa boasts varied landscapes, diverse wildlife and rich cultural resources. These assets corroborate the country’s growing global competitiveness as a tourist destination (World Economic Forum, 2007; 2019). From 1995 to 2017, international tourist arrivals to South Africa more than doubled from around 4.5 million to over 10 million. Over the same period, employment directly related to tourism tripled reaching 4.5% of total employment in 2017 (OECD, 2020a). The recent coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and resulting containment measures have triggered an unprecedented crisis in the tourism sector (OECD, 2020b). Still, tourism is a labour-intensive sector that can also bring foreign currency into the country. As such, the sector offers significant opportunities for an economy with weak growth and high unemployment. In recognition of its potential as driver for economic growth, the South African government has identified tourism as priority area in the Industrial Policy Action Plan (IPAP, 2010), the New Growth Path (NGP, 2010) and the National Development Plan (NDP, 2013). To ensure that the sector continues to play a key role in the economy following the COVID-19 pandemic, a recovery plan is currently being finalised. This plan focuses on stimulating demand, protecting and renewing supply and strengthening enabling capability. A managed re-opening is envisioned, followed by growth interventions to reclaim market share and drive long term growth.

Tourism connects to different sectors through a multitude of direct and indirect goods and services as well as a wide array of stakeholders. Tourism outcomes therefore depend on the interplay of actors at the global, local and intermediate levels. As the sector cuts across various systems such as global trade, finance, transport, consumption, marketing and production, strategies to boost the tourism industry need to be well aligned and co‑ordinated across policy sectors and across levels of government. Whilst the South African government has recognised the potential of the tourism sector for economic development, implementation of tourism strategies often falls short due to capacity constraints at the local level.

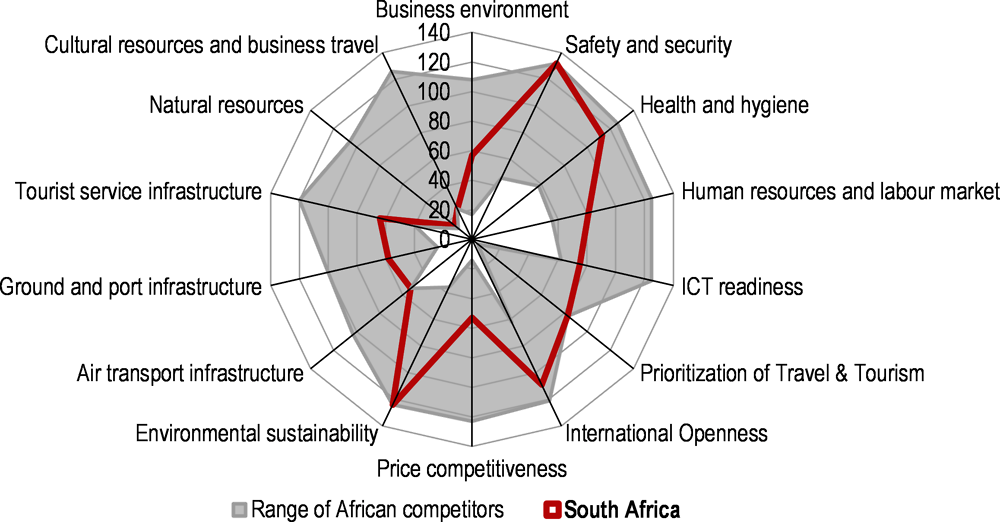

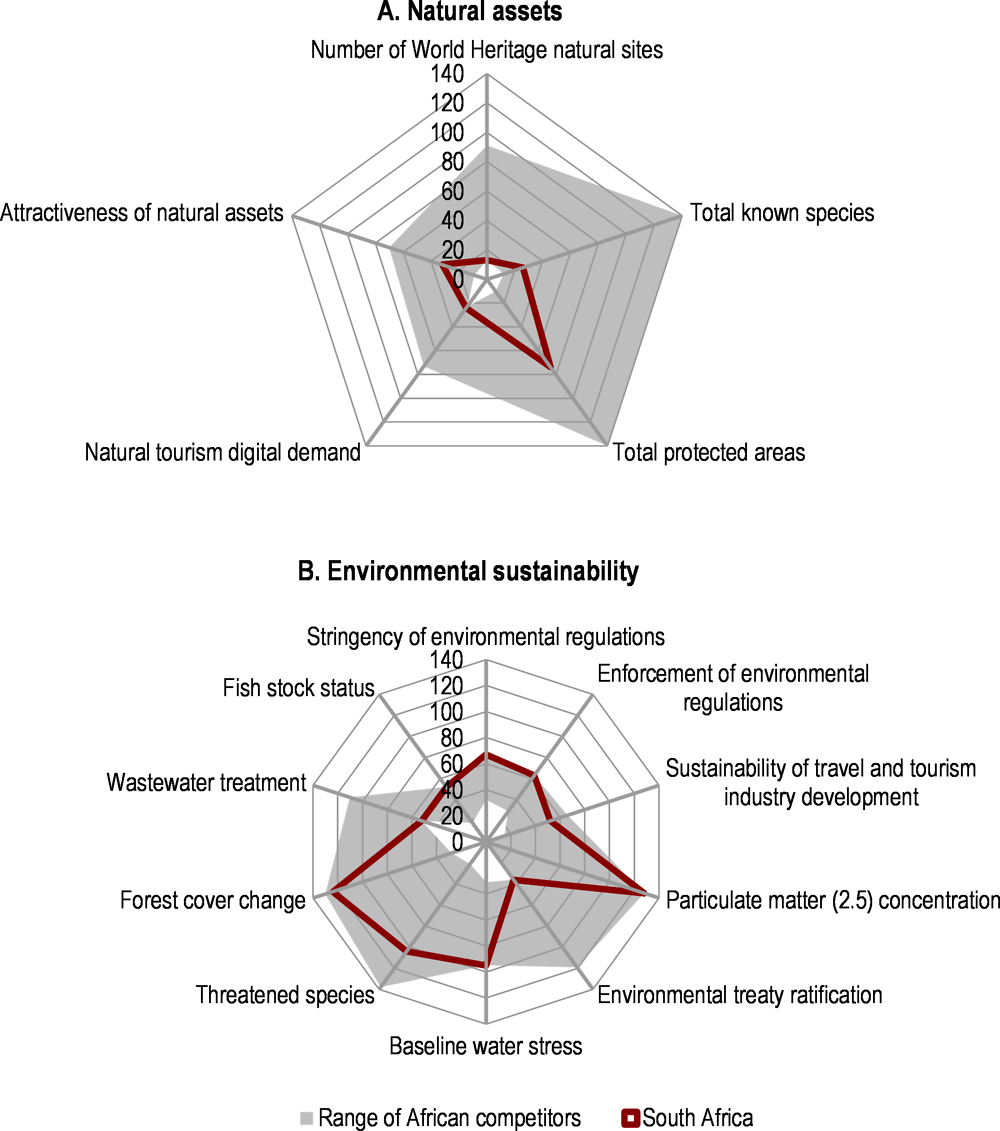

Within the sub–Saharan region, South Africa is a competitive tourism destination. Within the region, it ranks second behind Mauritius considering a range of indicators determining the competitiveness of destinations, ranging from business environment, infrastructure to international openness and attractiveness (World Economic Forum, 2019). Among all 140 countries ranked by the World Economic Forum, South Africa comes in 61st and thereby falls short of its target to become one of the top 50 destinations worldwide (South African Tourism, 2017). Given that South Africa is a long-haul destination for many large source markets, good accessibility and international openness are key to expand international tourism. While South Africa’s air transport infrastructure is well developed compared to African competitors, the country lags far behind in terms of international openness (Figure 3.1). In addition, concerns around safety, security, and increasingly environmental sustainability of tourism, of particular concern considering natural resources are seen as such a strength, could deter potential tourists from selecting South Africa as a destination.

Figure 3.1. South Africa is a competitive tourism destination on several dimensions, 2019

Rank from 1 (best) to 140 (worst), 2019

Note: Range of selected competitors include Botswana, Namibia, Mauritius, Kenya and Tanzania.

Source: World Economic Forum (2019), Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR19_data_for_download.xlsx

This chapter looks at the potential of tourism to support sustainable and inclusive growth in South Africa. How much the domestic economy and ultimately the local population benefits from tourism depends on a variety of factors such as the economic integration of the tourism industry into local value chains. As a labour-intensive sector, tourism provides opportunities for different skills and experience levels allowing for greater social integration. However, if not well planned and managed, tourism growth can increase the pressure on environmental resources, on housing markets and increase inequality through unbalanced demand. Not only do these aspects of tourism have to be taken into account to achieve inclusive and sustainable growth, but the benefits of tourism must also spread geographically ‑ beyond mature destinations ‑ to create economic opportunities in less travelled and less prosperous regions. This is especially important in a country that is as spatially segregated and unequal as South Africa.

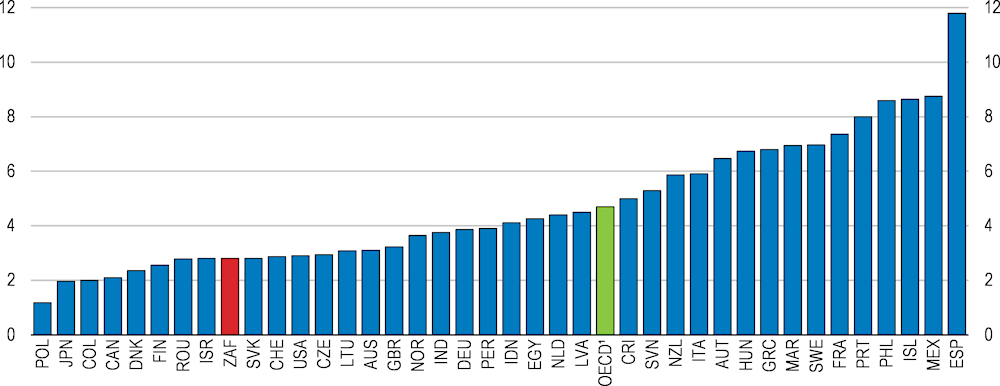

Tourism and the economy

Tourism has gained importance in the South African economy in recent decades. Since the end of apartheid, tourism in terms of its direct contribution to overall GDP has increased from 1.8% in 1995 to 2.8% in 2017 (Statistics South Africa, 2018b; 2018a) – around 9% when taking into account estimated indirect impacts (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2018). The contribution of tourism to South Africa’s economy is comparable to countries such as Sweden, the Czech Republic and Colombia, but below the OECD average (4.7%). Compared to other emerging countries such as India, Indonesia or global tourism competitors such as Mexico and the Philippines, the contribution of the tourism sector to the economy is relatively small indicating the potential for a greater role (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Direct contribution of the tourism industry to the economy is moderate

In per cent of total GDP, 2018 or latest available year

1. Unweighted average of available countries.

Note: GDP data for France refer to internal tourism consumption. GVA data are used if GDP data are not available. GDP for Greece refer to tourism GVA of industries 55-56 of NACE Rev. 2. GDP data for Spain includes indirect effects.

Source: OECD, Tourism Database.

International tourist arrivals increased from 4.5 to 10.3 million between 1995 and 2017, accompanied by a rise of tourism expenditure of non-resident visitors from 2.6% to 3.7% of GDP over the same period (World Tourism Organization, 2018). By 2017, inbound tourism expenditure has been the dominant category of exports in services at 61.5% and representing 9.3% in total export of goods and services (World Tourism Organization, 2018). Thus, tourism provides an opportunity to expand exports to foreign currency earnings. While the economy and especially the tourism sector has been heavily hit by the recent COVID-19 pandemic (OECD 2020b), these numbers highlight the potential the tourism sector can play in the post-COVID-19 recovery phase.

Integration of tourism in global and local value chains

The impact of tourism on the economy depends on the strength of inter-sectoral linkages and ownership patterns. The economy can benefit directly from tourist consumption (forward linkages), but also indirectly through increased demand in sectors that support the tourism industry (backward linkages) (Cornelissen, 2005; Sinclair, 1998). However, ownership patterns of tourism producer and supplier companies influence how much of the value added stays within the domestic economy. Owing to the complex and cross-cutting nature of tourism, understanding its role in the economy is not straight forward. Statistics South Africa produces a Tourism Satellite Account (TSA), which measures the general weight and direct impact of tourism from a macro-economic perspective (Box 3.1).

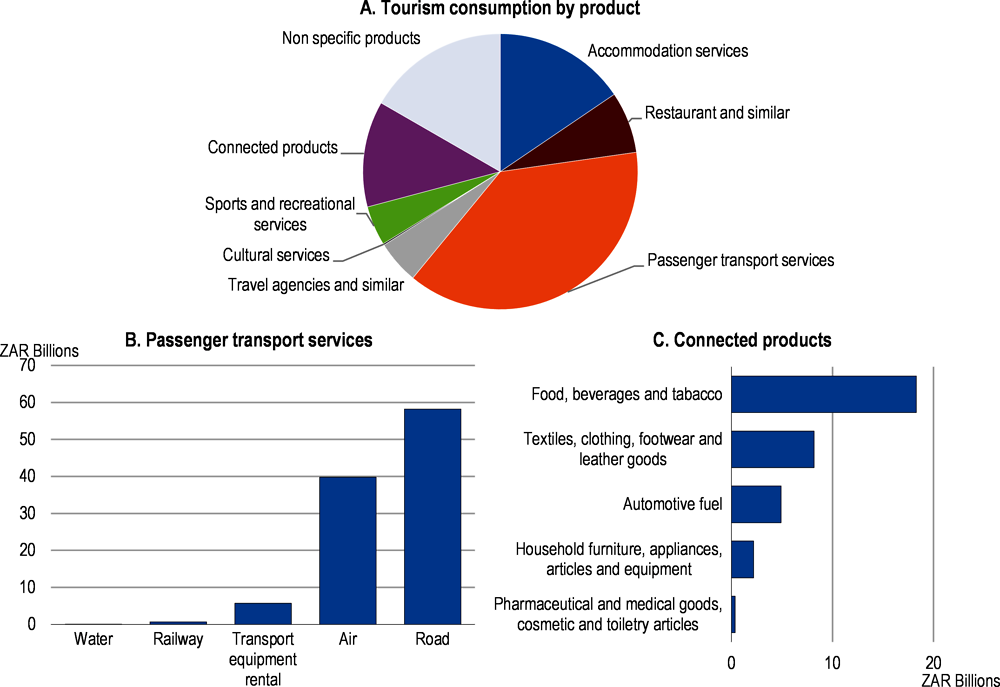

Tourism consumption in South Africa extends beyond the typical tourist products related to accommodation and food services. The Tourism Satellite Account provides information on consumption items by domestic and international tourists and therefore allows the analysis of forward linkages in the tourism sector. In 2018, the main tourism consumption items were passenger transport (38%) and accommodation services (16%). Consumption of connected goods, such as food, beverages, tobacco, clothing, leather goods, furniture or automotive fuel, amongst others, accumulated to about ZAR 33.9 billion, comprising the third-largest tourism consumption group (12%) (Figure 3.3, Panel B). Connected goods and non-specific products amounted together to almost a third of internal tourism consumption, highlighting the potential of direct spillover effects of tourism to other economic sectors. Unfortunately, the TSA does not allow a further disaggregation to analyse the forward linkages to specific products nor the extent to which tourism expenditure remains within the local economy. Making informed policy decisions to support the tourism business environment requires more detailed data to better understand the strength of inter-sectoral linkages in the tourism value chain. Thus, the TSA data should be extended to trade in value added (Box 3.1).

Figure 3.3. Internal tourism consumption stretches beyond traditional tourism products

By type product, 2018

Note: Preliminary data.

Source: Statistics South Africa (2019), Tourism Satellite Account for South Africa, final 2016 and provisional 2017 and 2018.

Box 3.1. Informing policy through tourism account data provision and analysis of tourism trade in value added

The Tourism Satellite Account (TSA) is a conceptual framework aimed at measuring the weight of tourism from a macro-economic perspective. It focuses on the description and measurement of tourism in its different components (domestic, inbound and outbound). It also highlights the relationship between consumption by visitors and the supply of goods and services in the economy, principally those from tourism industries. With this instrument, it is possible to estimate tourism GDP, establish the direct contribution of tourism to the economy and develop further analyses using the links between the TSA, the System of National Accounts and the Balance of Payments.

In addition to the TSA, analysing tourism from a trade in value added (TiVA) perspective can provide new and useful insights to support policy making and action. This approach allows for a better understanding of the direct and indirect impacts of tourism, tourism expenditures, the breadth and depth of linkages between tourism and other sectors, the relative importance of tourism in supporting export-led growth compared to other sectors, and the tourism source markets that generate the most value during their visit. It is also possible to do more in-depth analysis focusing on specific branches of the tourism sector (e.g. accommodation and food service, passenger transport). As new data become available, new possibilities are opening up to analyse the impact of tourism on jobs and wages, the role of SMEs and large foreign operators in tourism GVCs, and the impact of tourism on sustainability (CO2 emissions). Making progress on these issues will require statistical and policy engagement at national and international level, and prioritisation of the actions needed to advance.

Source: OECD (2019), “Providing New Evidence on Tourism Trade in Value Added”, OECD Tourism Papers, No. 2019/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d6072d28-en.

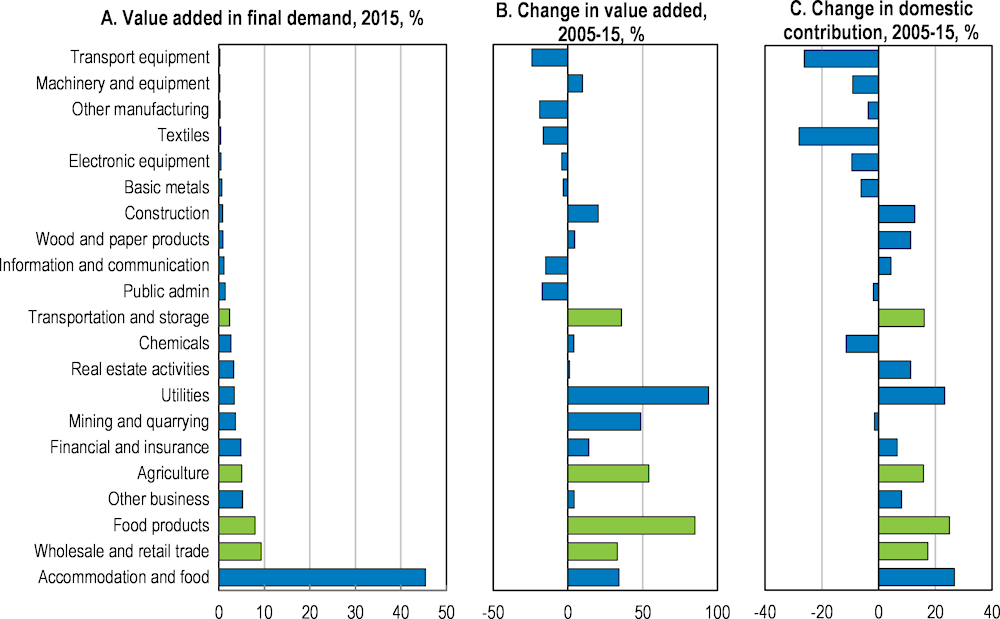

Owing to the complex nature of tourism, its economic effect spreads beyond direct effects of consumption. Using value added in final demand by the accommodation and food sector as proxy for the tourism sector indicates that growth in tourism resulted in better integration of some sectors into the tourism value chain (Figure 3.4). With regard to agriculture, food products, trade and transport services, higher levels of final demand by accommodation and food services are combined with growing participation by domestic suppliers and producers and with a slight increase in the relative weight of the industry in final demand. These backward linkages of the accommodation and food service sector, while only showing a partial image of the tourism value chain, highlight the potential of inter-sectoral linkages with the rest of the economy. Further expanding these linkages is important and should be supported by policies that provide the right framework to facilitate the creation of linkages by bringing together different actors and by stimulating a dynamic business environment.

To increase the impact on the local economy, it is important to strengthen local linkages to create business opportunities for local suppliers. These linkages can in turn contribute to a more dynamic business environment in general (see below). As recommended in the last economic survey of South Africa (OECD, 2017e), increasing access, information and training on public procurement can support the growth of small businesses. With respect to tourism, the National Responsible Tourism Development Guidelines issued in 2002 encourages the integration in local value chains through procurement of local goods and services from locally owned enterprises that meet quality, quantity and consistency standards (UNCTAD, 2017). Still, many national parks and safari lodges use intermediary suppliers that source the bulk of their fresh fruit and vegetable produce from distant urban wholesale markets (Rogerson, 2015). Better information regarding procurement, product safety and standards requirements should be provided to local enterprises to facilitate their integration into local supply chains. For example, capacity-building workshops could be undertaken in partnership with hotels aiming to improve the knowledge of local small and medium-sized enterprises. In addition, buyer agreements of hotels with local suppliers that have undergone training could increase local sourcing (see e.g. UNCTAD, 2017).

Figure 3.4. Composition of value added in final demand by accommodation and food services

Value added in final demand by accommodation and food services, by source industry

Note: Sectors mentioned in the text are highlighted in green.

Source: WTO/OECD (2019), "Trade in value added", OECD-WTO: Statistics on Trade in Value Added (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00648-en (accessed on 17 January 2019).

Business sector dynamics

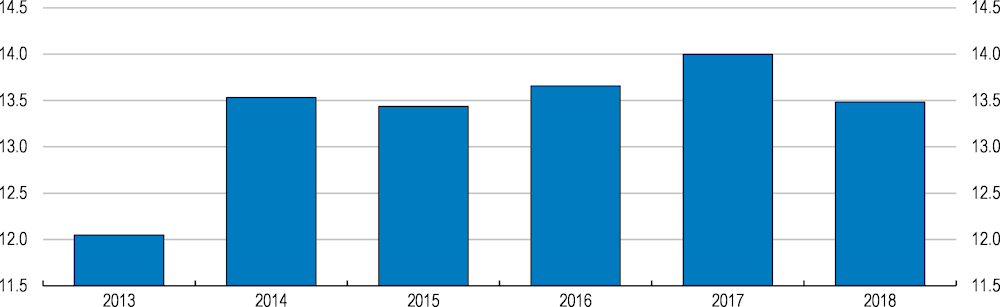

Supporting local integration of the tourism sector requires a dynamic business environment that facilitates the creation of inter-sectoral linkages and local spillovers. Small businesses and entrepreneurs are crucial for creating such an environment. Between 2013 and 2018, the total number of enterprises in the economy slightly increase from 335 000 to 345 000, with most of the change incurring between 2017 and 2018. The number of tourism establishments, however, increased by 6 200 – an increase of 15% (Figure 3.5). About one quarter of these new tourism establishments related to food and beverage serving activities and the great majority to other tourism activities (World Tourism Organization, 2020).

Figure 3.5. Enterprises are increasingly concentrated in the tourism sector

Number of tourism establishments as a percentage of total establishments, 2013-2018

Note: Tourism establishments include accommodation for visitors, food and beverage serving activities, passenger transportation, travel agencies and other reservation services and other tourism characteristics industries.

Source: World Tourism Organisation (2018, 2019), Compendium of Tourism Statistics dataset [Electronic], UNWTO, Madrid, data updated on 07/11/2019; Statistics South Africa (2019), Annual Financial Statistics, various years.

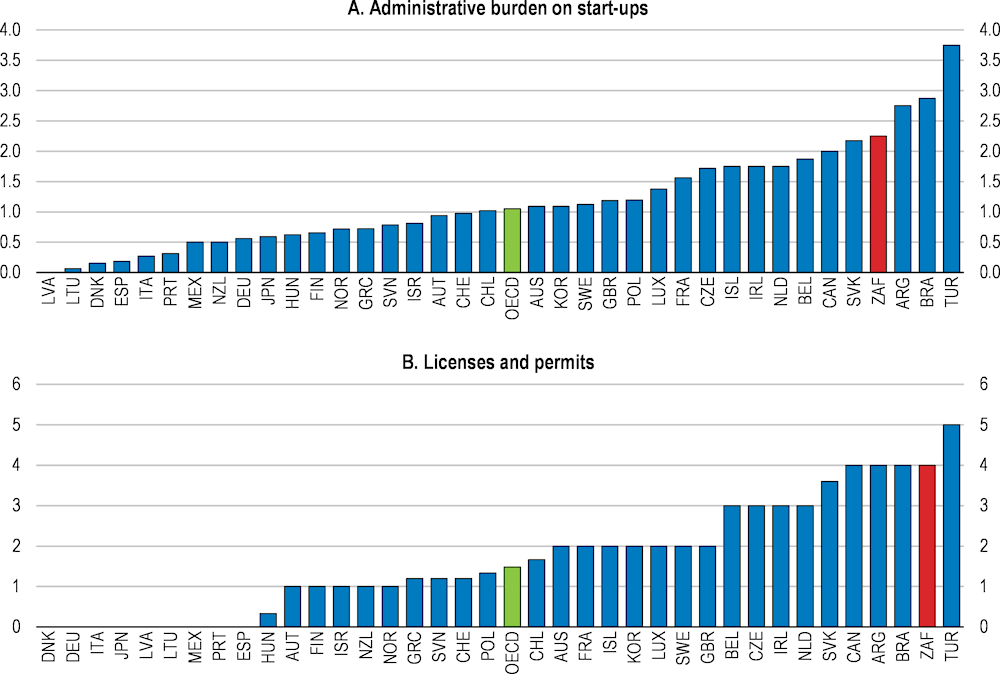

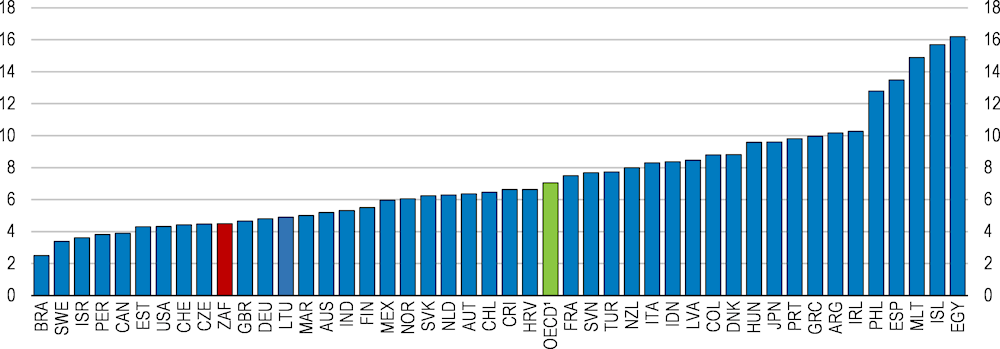

Underlying conditions for small businesses and entrepreneurs need to be eased in order for the tourism sector to thrive. As highlighted in the last economic survey for South Africa (OECD, 2017e), red tape and licensing create large burdens for entrepreneurs and small firms, and the tourism sector is not immune. Relative to OECD member countries, South Africa has one of the highest barriers in the form of administrative burden on start-ups and the second highest barriers in the form of licences and permits (Figure 3.6). This affects entrepreneurs in the tourism sector and beyond, resulting in long times to start a business (World Economic Forum, 2017). It is important to systematically review and reduce where practicable the stock of red tape and licensing requirements that directly affect the tourism sector such as transport vehicle licensing, but also indirectly such as licensing for the sale of alcoholic beverages in the food and beverage industry. In addition the efficiency of licensing processes, especially for annually renewable licenses, such as the licensing for the sale of alcoholic beverages, has to be improved to avoid lengthy waiting times and to keep businesses running. Improving the regulatory environment and creating a supportive business environment in general would not only benefit businesses in the tourism sector but other sectors as well.

Policies to improve the competitiveness of tourism need to give significant attention to the performance and quality of tourism businesses and the level of investment in the sector. This is partly about improving the overall business environment, but also includes actions to identify and promote quality and to provide various forms of incentive and support (OECD, 2018b). In South Africa, examples include a tourism incentive programme developed to support participation of small tourism businesses in the national quality grading system in order to compete efficiently in the market. As part of another, expenditure for exposure at international marketing platforms may be partially covered if in line with the marketing priorities of South African Tourism (see Table 3.1 below). In addition, a reimbursable cash grant programme was designed to support the establishment of tourism-related businesses (Tourism Support Programme, TSP) under the Department of Industry and Trade and has since been transferred to the Department of Tourism. Running from 2008/09 to 2014/15, a total of 545 applications were approved with an incentive value of ZAR 1.1 billion.

Figure 3.6. Red tape and licensing create large burden for entrepreneurs and SMEs

Index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, 2018

South Africa needs to strengthen the non-financial support to new entrepreneurs in the form of entrepreneurial education. It is widely understood that knowledge and skill-gaps relevant for business creation can hinder the capacity to start and operate businesses (OECD, 2017e). Thus, measures to support entrepreneurship and SMEs across the OECD focus not only on access to finance but also on skills development with an emphasis on business management and financing (see Box 3.2). Increasing skills related to business management, such as marketing, human resources and financial management, can support the creation of profitable enterprises. In addition, training opportunities in tourism management aimed at formal enterprises, such as small-scale tour operators and accommodation facilities, and technical training for local suppliers, can help enhance the capacity of enterprises to operate viable tourism establishments (UNCTAD, 2017). Developing successful small and medium-sized tourism companies will also contribute to the creation of jobs in the sector. As small businesses were particularly hit by the recent COVID‑19 pandemic, the South African government introduced the “Tourism Relief Fund”. Available since April 7th 2020, this fund provides once-off capped grant assistance to Small Micro and Medium Sized Enterprises in the tourism value chain to ensure their sustainability during and post the implementation of government measures to curb the spread of Covid-19 in South Africa. The grant funding, capped at ZAR 50 000 per entity, can be used to subsidise expenses towards fixed costs, operational costs, supplies and other pressure cost items. Categories eligible to apply for the Tourism Relief Fund include accommodation establishments, hospitality and related services, travel and related services (OECD, 2020b). To support the recovery of the tourism sector, the Tourism Relief Fund should be increased and extended up to mid-2021, particularly if there is a renewed virus outbreak later in the year.

Box 3.2. Programmes to support tourism entrepreneurship

Welcome City Lab, Paris

Launched in 2013, Welcome City Lab is a Paris-based SME aimed at fostering innovative entrepreneurship in tourism related activities. The publicly supported private incubator is offering individual coaching and collective training workshops, along with a network of funders and mentor entrepreneurs. The main features of the Welcome City Lab approach are:

Incubator for tourism firms – support innovative start-ups in tourism-related activities.

Training – help start-ups become familiar with and gain an understanding of the tourism sector.

Experimentation – help start-ups to keep up with market demands.

Economic intelligence – identify trends in tourism innovation.

Every year, a committee decides on the themes for the annual call for projects, under which potential start-ups are chosen. The criteria to select projects focus on the capacity to undertake the innovation, the potential for job creation, the contribution to growing the tourism offer in Paris, the human capital skills of the team, and the viability of the business plan.

INADEM, Mexico

Established in 2012, the National Institute for Entrepreneurship (INADEM) is mandated to support and facilitate the development of SMEs, including micro-enterprises. Although INADEM does not target tourism SMEs specifically, the aim of the institution is to boost productivity and entrepreneurship across all strategic sectors, including tourism-related activities if the project involves entrepreneurial skills, incorporation into value chains, or is productivity enhancing. It does this by raising awareness, linking firms to finance opportunities in the banking system and channelling federal funds through a broad range of finance instruments, including subsidies, debt, credit guarantees, and equity.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/tour-2018-en.; OECD (OECD, 2017f), Tourism Policy Review of Mexico, OECD Publishing Paris; OECD (OECD, 2017d), OECD Economic Surveys: Mexico 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Tourism development to support employment growth

A main motive for South Africa’s prioritisation of tourism as a strategy for development relates to the sector’s ability to generate employment. From 1995 to 2017, direct employment in the tourism industry more than tripled from just above 200 000 to around 722 000. This increase by over three and a half times in the number of jobs demonstrates the labour intensity of the sector and its potential to respond to the country’s employment challenge. Over the last five years alone, the tourism sector created 64 313 jobs, more than the mining and manufacturing sectors combined (Statistics South Africa, 2018b; 2017). About 4.5% of total employment in South Africa is directly linked to tourism, which is in line with similar sized tourism economies but below the OECD average of 6.9% (OECD, 2018e).

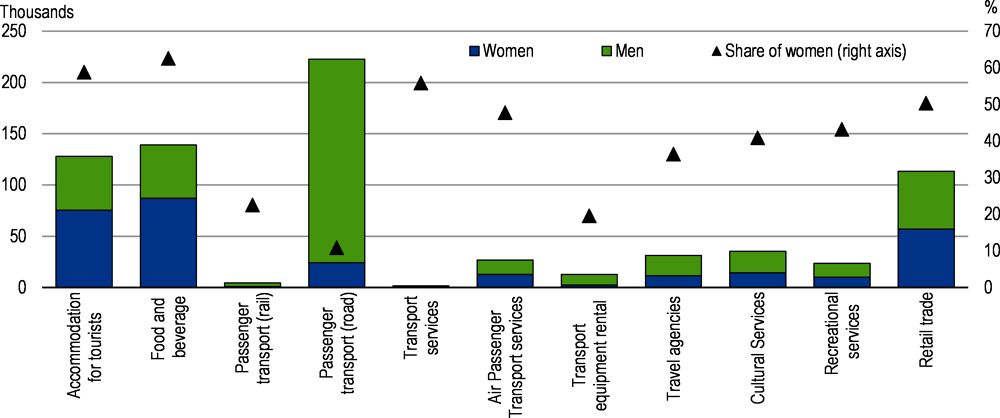

South Africa suffers from a stubbornly high unemployment rate, particularly among young people and women (see KPI). The tourism sector offers job opportunities for people of different ages and skill levels, and provides important employment opportunities for women (OECD, 2018e). Indeed, about 40% of employment in tourism industries consists of women. The share increases to more than 55% when disregarding the passenger transport sector where female employment is rather low (15%). However, women made up 63% of employment within food and beverage serving activities (Statistics South Africa, 2019). In addition, women constitute about 60% of employees in accommodation for tourist activities and more than 50% in retail trade. (Figure 3.8). Therefore, even with fixed shares by sector, job growth in the tourism sector can support a better gender balanced and a more inclusive South African workforce.

Figure 3.7. Tourism employment is below the OECD average

As per cent of total employment, 2018 or latest year available

1. Unweighted average of available countries.

Note: 2017 data for Australia, Austria, Chile, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Lithuania, Norway, United States and South Africa; 2016 data for United Kingdom, Philippines, Portugal and Slovak Republic; 2015 data for Egypt, Italy Peru; 2012 data for Argentina, India and Indonesia.

Source: OECD, Tourism Database.

Figure 3.8. Tourism provides important employment opportunities for women

Direct tourism employment, 2018

For tourism to provide increased opportunities for job security and upwards social mobility, the industry must foster career and skill development opportunities. Experiences in South Africa have shown that employees who started with low skill levels were able to progress in their career and increase their quality of life when provided with the opportunity to gain experience and develop transferable skills (Butler and Rogerson, 2016). To support the acquisition of skills and lifelong learning, tourism firms should invest significantly in employee training. Investment in skills development will not only provide an opportunity to improve productivity and enhance customer experience, but also allow an upward movement of employees on the social ladder. In addition, ensuring that individuals have a variety of transferable skills provides further career prospects by allowing them to take advantage of opportunities in different sectors and overcome the vulnerability in tourism associated with seasonal employment (Stacey, 2015).

Although the tourism sector is characterised by a range of low-skilled tasks, a low quality workforce can affect visitor’s experience. As highlighted in previous surveys, raising the quality of basic education is needed to improve the quality of the general workforce (OECD, 2017e; 2013). Underlying skill-shortages are increasingly affecting the tourism sector (Department of Tourism, 2017). A tighter relationship between firms and the education system can address emerging skills shortages. For example, in Brazil the Pronatec is a publicly-funded programme that supports private and public vocational training courses with the aim of linking training places in each region with the skills needed using explicit requests from individual businesses (O’connell et al., 2017). Thus, vocational skills development can play a role in bridging the skills gap by ensuring the availability of well-trained personnel to meet the demand of the tourism sector and productive sectors in the tourism value chain. The authorities should implement the steps identified in the National Tourism Sector Strategy and provide quality career guidance and greater integration of workplace oriented learning to improve the school-to-work transition (Department of Tourism, 2017). Further, on-the-job training programmes that cater to the ever-changing tourism environment should be developed. Not only will training improve employees’ career prospects, but also counter the effect of seasonality on working conditions if training modules are held during off-peak periods.

Increasing local participation in tourism through digitalisation

Increased digitalisation has affected the tourism sector in many ways – especially with respect to employment opportunities. While travel planning, booking of travel itineraries and accommodation has shifted from tourism offices to the individual via booking platforms, the sharing economy provides easy access for stakeholders to participate in the tourism economy. For example, since 2008 about 2 million visitors to South Africa have booked accommodation through the peer-to-peer platform AirBnB (AirBnb, 2018). According to AirBnB, most hosts in South Africa are using their extra income from hosting to make ends meet and otherwise afford to stay in their homes. Spillovers to the local community are further created through new ways for tourists to experience the destination, for example through people-to-person experiences guided by locals as well as through facilitated travel mobility through car sharing such as Uber and Mytaxi (OECD, 2018e).

The rapid growth of the sharing economy not only provides opportunities, but also creates challenges for established operators. It further raises broader questions of consumer protection, taxation and regulation. Accommodation sharing services in particular may affect neighbours and local residents, due to noise and other disturbances, and by contributing to pressure on the local housing market. In Iceland, for example, the under-supply of housing and the growth of short-term rental market to tourists have made housing less affordable (OECD, 2017c). In a worst-case scenario, poorly managed growth of these services may also have a detrimental impact on the historical fabric of destinations and reduce the appeal of areas as places to live and visit (OECD, 2018e). Carefully thought through policy responses are therefore needed to balance the benefits of accommodation-sharing services, such as extra capacity in peak periods and encouraging tourists to disperse to less well-known destinations and the potential negative externalities created in local neighbourhoods. It is also important that basic safety and quality standards for accommodations are adhered to. For example, authorities may impose similar standards for owners who make extensive use of accommodation rentals as for the formal sector. This may require them to change the use into commercial property and adhere to the respective regulation.

Fiscal impact of tourism

A growing tourism sector is associated with higher fiscal revenues, although the exact extent of the contribution is difficult to assess. According to the Tourism Satellite Account, the tourism share in taxes net subsidies on production are estimated at about ZAR 2.2 billion for 2017. The majority of the revenues stem from the accommodation services and restaurant sector, followed by non-tourism specific industries (Statistics South Africa, 2018b). Fiscal expenses on tourism takes the form of direct budget transfers to the Department of Tourism mirroring the estimated tourism share in taxes on production for the fiscal period 2017-18 with ZAR 2.1 billion. For the fiscal year of 2018-19, the Department’s budget slightly increased to ZAR 2.3 billion, of which about 53% is allocated to South African Tourism, mainly for marketing purposes. The remaining ZAR 1 billion is distributed amongst tourism incentives, an expanded public works programme (including skills development), destination development, enterprise development and visitor support services (Department of Tourism, 2018a).

Financing of tourism development is difficult at the provincial and the local level, as their revenue sources are often not sufficient to meet the spending requirements. Especially more disadvantaged provinces and municipalities that aim to leverage tourism for their economic development often rely on transfers. While tourism is a priority area at the national level, budget allocation for tourism at the provincial and local level are often insufficient as the sector is competing with policy fields that are of higher importance to the local population, such as education and health. Thus, tourism at the local level is often referred to as an unfunded mandate and receives low priority. To ensure that tourism receives a higher priority at the subnational level, the government could develop a tourism funding model for provincial and local governments. By developing budget allocation mechanisms and instruments that guarantee a reasonable budget for tourism and secure its spending on tourism development. Tourism authorities could also advocate for frameworks governing infrastructure and other conditional grants, such as the Municipal Infrastructure Grant Framework and the Public Transport Network Grant Framework, to more explicitly provide for tourism catalytic infrastructure to be eligible for funding. Alternatively, local governments could be allowed to collect a tourism charge to broaden their revenues. Tourism charge has been an instrument introduced in several OECD countries (OECD, 2018c; OECD, 2018e) to provide additional revenues to local budgets and provide a dedicated financial source for local tourism development, marketing and maintaining natural and cultural tourism resources.

Recent tourism developments and tourism prospects in South Africa

To support tourism development, the Ministry of Tourism developed a National Tourism Sector Strategy (NTSS) in 2010. The strategy highlights a number of initiatives, policies and projects to support the country’s emergence as a destination of international significance and to stimulate domestic tourism (Box 3.3). Updated in 2016, the aim of the strategy is to respond to key challenges and opportunities facing the sector in South Africa through ‘Effective Marketing’, ‘Destination Development’, Visitor Experience initiatives’ and ‘Facilitating Ease of Access’. At the same time, the national destination marketing agency South African Tourism (SAT) is implementing a strategy necessary to increase international tourist arrivals by 4 million and domestic holiday trips by 1 million over the course of five years.

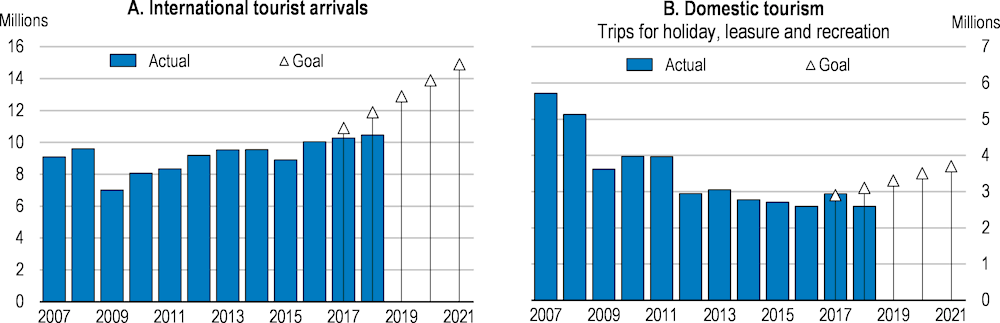

Within the first two years of the “5 million in 5 years” strategy, objectives were only reached with respect to domestic holiday trips in the first year (South African Tourism, 2018a). Developments in domestic tourism are closely linked to conditions in the local economy. Although domestic tourism trips overall (including holiday, business and visiting friends and relatives) declined by almost 30% between 2016 and 2017, the first-year target to reach more than 2.9 million domestic holiday trips was fulfilled (Figure 3.9, Panel B). However, in 2018, domestic holiday trips declined falling short of the targeted objective. Similarly, the goal to increase international tourist arrivals to 10.899 million in 2017 and 11.899 million in 2018 was missed, falling short by about 600 000 tourist arrivals in 2017 and 1.4 million tourist arrivals in 2018 (Figure 3.9, Panel A). While it is important to monitor tourism indicators, the cyclic nature of tourism flows should be differentiated from transformative issues. Thus, trends that emerge more slowly, such as demographic change in the core markets or increasing digitalisation may require an adjustment of tourism strategies. Authorities should therefore regularly evaluate and if necessary adapt the monitoring framework to include new indicators that capture new trends such as digitalisation.

Box 3.3. Policy framework and National Tourism Sector Strategy in South Africa

In 2010, the government selected tourism as one of five priority sectors in its 20-year growth plan. In the following year, the key framework document guiding both public and private sector action was published, with quantitative targets from 2010 to 2020. The Tourism Act of 2014 provides the overarching legislative context within which tourism development and growth is pursued. In 2016, the National Tourism Sector Strategy (NTSS) of 2010 was updated to respond to global trends including changes in tourist demographics and associated consumer needs.

The revised NTSS envisions a rapidly growing tourism economy that leverages the country’s competitive advantages in nature, culture and heritage supported by innovative products and service excellence. Initiatives include the provision of infrastructure development, maintenance, and enhancement, and the diversification of tourism products, experiences and routes. Complementing the NTSS, the goal “5 million in 5 years” pursued by South African Tourism is to increase international tourist arrivals by 4 million and domestic tourism trips for holiday, leisure and recreation by one million from 2017-21.

To increase the direct contribution of the tourism sector to the economy, five strategic pillars were identified:

Effective marketing: A coherent approach to promote South Africa to become a top of mind destination and improve the conversion rate.

Facilitating ease of access: Seamless travel facilitation and access to participate in tourism.

Enhancing the visitor experience: Provide quality visitor experiences for tourists to achieve customer satisfaction and inspire repeat visitation.

Improving destination management practices: To provide for sustainable development and management of the tourism sector.

Ensuring inclusivity in all tourism endeavours: Promote the empowerment of previously marginalised enterprises and rural communities to ensure inclusive growth of the sector.

Investment in the development of tourism products is critical to improve destination competitiveness and to meet the needs of both domestic and international visitors. As such, 53% of the Department of Tourism’s budget for the fiscal period 2018-19 is allocated to South African Tourism (SAT). In addition, tourism services can voluntarily charge consumers a tourism levy of 1% levy, which has the objective to provide additional funds to South African Tourism.

Source: OECD (2018e), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2018. National Tourism Sector Strategy, 2017.

By following a tourism strategy that seeks a balanced development between the international and domestic segment, South Africa aims to strengthen the sector’s resilience. Performing well in attracting international tourists can provide external stimulus to a weak economy and counter weak performance in the domestic segment. A robust domestic tourism market in turn increases the resilience against fluctuations and external shocks in core market economies. In 2018, the domestic tourism segment in South Africa constituted about 56% of internal tourism expenditure (Statistics South Africa, 2019). In the context of a struggling domestic economy, current efforts are predominantly focussed on attracting more international tourists and expanding core markets.

Figure 3.9. Development and future goals of tourist numbers

2007-2021

International tourism

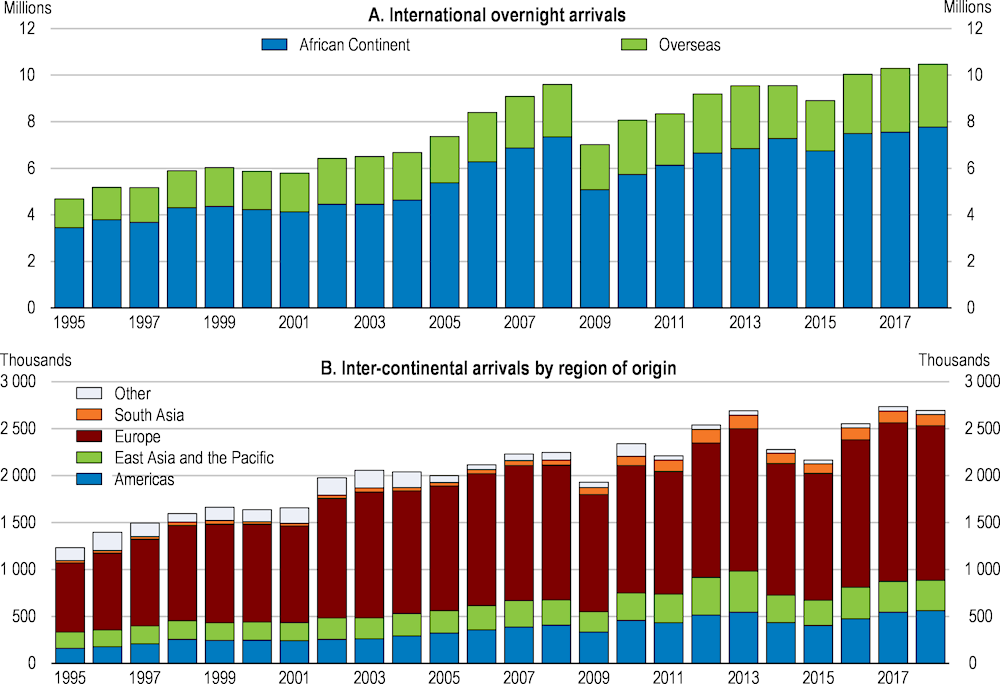

Developments in South Africa’s international tourism segment highlight both, the potential volatility of the sector and the difficulties to increase international tourist arrivals. Despite demonstrating remarkable resilience in recent years, global tourism remains sensitive to the challenges posed by global economic conditions, geopolitical turmoil, terrorism, and natural disasters (OECD, 2018e). Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered an unprecedented crisis in the tourism economy. OECD estimates on the COVID-19 impact point to 60% decline in international tourism in 2020, which could even rise to 80% if recovery is delayed until December (OECD, 2020b). As previous crises have shown, it will be crucial to restore traveller confidence and to stimulate demand. For example, following the global financial crisis, international tourist arrivals to South Africa dropped by almost 30% in 2009 (Figure 3.10). In addition, media coverage can significantly affect perceptions of safety and security following natural disasters, pandemics, terrorist attacks and the like. After the 2014 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, inbound travel from the African continent declined in addition to overseas tourists who avoided the entire African continent. Subsequently – and despite being several thousands of kilometres away from the outbreak ‑ arrivals to South Africa dropped by 645 000 visitors (World Tourism Organization, 2018). A coherent communication strategy in events of potential and occurring crises that focuses on a credible risk assessment is important (Haxton, 2015). By providing up-to-date information through an authorised channel, potential tourists can be supported in making informed travel choices.

High crime rates in South Africa also influence the perceptions of safety, which has a significant influence when potential tourists make their travel choice. The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index has continuously ranked the country within the lowest performing quintile of countries with respect to safety and security over the last decade (World Economic Forum, 2019; 2017; 2015; 2013). The low ranking primarily results from a high homicide rate and high costs for businesses due to crime and violence, indicators that do not directly capture crime or violence against tourists. Nevertheless, they affect perceptions of security within the destination. Collecting and disseminating information of crime against tourists could help to alter perceptions of personal safety in South Africa. According to the departure survey conducted by South African Tourism, around 80% of respondents over the course of 2017 had no negative experience in any form whilst in South Africa as tourists. However, about 6% stated safety and security, and about 5.5% personal safety as the most negative experience during their stay (South African Tourism, 2017f; 2017c; 2017e; 2018c). Credible and up-to-date information on safe areas that are easily accessible for domestic and international tourists alike should be provided. Such information could be complemented by greater visibility of safety and police personnel in main tourist areas as proposed in the recently finalised safety monitor programme. This is a welcomed step as it could reduce crime against tourists, make them feel safer and portray a more positive outlook to potential tourists. A general reduction in crime will also improve the well-being of the local population.

Figure 3.10. International tourist arrivals are back to pre-crisis levels

1995-2018

Note: Panel B: Other refers to non-classified arrivals.

Source: World Tourism Organization (2019), Yearbook of Tourism Statistics dataset.

Increasing international tourist arrivals not only requires improving safety and security issues, but also strategic marketing efforts in key emerging markets. Since 1995, Europe has been a core origin market for overseas tourist arrival (Figure 3.10, Panel B). In recent years, South Africa has expanded its tourism marketing efforts to new markets arising from a growing middle class in emerging economies (Table 3.1). The number of tourist arrivals from regions with an increasing middle class such as South Asia (driven by India) more than doubled over the last 10 years - yet this remains a market with significant untapped potential due to burdensome visa regulation (see below). The largest share of international tourist arrivals, however, originates from the African continent - especially visitors from countries that do not have to overcome a great distance and long travel times. Thus, the neighbouring countries Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and Mozambique accounted for over half of total overnight international arrivals (50.7%) in 2018 (South African Tourism, 2019).

Table 3.1. South African Tourism’s leisure market portfolio

2017

|

Africa & Middle East |

America |

Asia & Australia |

Europe |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Core markets (about 60% of efforts are deployed in these markets) |

Angola Domestic Kenya Mozambique Nigeria Tanzania |

Brazil USA |

Australia China India |

France Germany Netherlands UK |

|

Investment markets (about 20% of efforts are deployed in these markets) |

Botswana DRC Ghana Lesotho Uganda Zimbabwe |

Canada |

Japan South Korea |

Italy Russia |

|

Tactical markets (about 15% of efforts are deployed in these markets) |

Namibia UAE Zambia |

- |

Singapore |

Switzerland |

|

Watch list markets (about 5% of efforts are deployed in these markets) |

Ethiopia Malawi Swaziland |

Argentina |

New Zealand |

Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Turkey |

|

Strategic importance |

Egypt Israel Morocco Saudi Arabia Tunisia |

- |

Malaysia |

- |

Note: Bolded countries have a reciprocal visa-waiver agreement with South Africa. Cursive countries are visa exempt without reciprocal arrangements.

Source: South African Tourism (2017b), South African Tourism Annual Report 2016/2017.

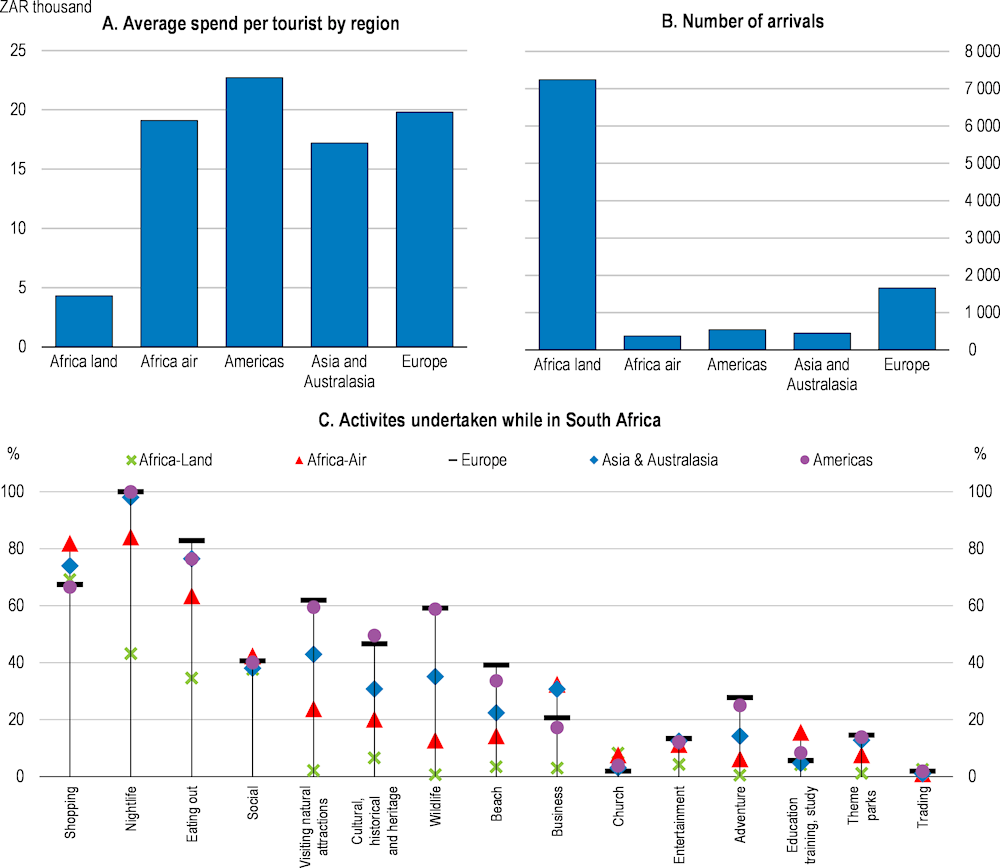

As for many destinations, the purpose of trip for international visitors to South Africa varies, as does, subsequently, their participation in activities and tourism-related spending. Market research indicates that most tourists from overseas markets are coming to South Africa for leisure purposes, whereas tourists from the African continent are more likely to visit friends and relatives, or travel for business or medical reasons (South African Tourism, 2018a). Visitors arriving from long-haul markets tend to participate in a wide variety of leisure-based activities, whereas those arriving by land from neighbouring countries are more likely to engage in social activities, as well as shopping, nightlife and eating out (Figure 3.11). Overseas visitors, as well as those arriving from continental Africa by air spend significantly more on average and are more likely to participate in activities related to natural attractions, cultural heritage and wildlife. Marketing strategies in these high spending origin markets should therefore focus on these core competitive assets.

Figure 3.11. Tourist numbers, spending behaviour and activities undertaken while in South Africa

2017

Note: Africa land refers to Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Africa air refers to African countries not included in Africa land.

Source: South Africa Tourism Annual Report, 2017.

Facilitating travel to South Africa is key to increasing inbound tourism

To attract international visitors to South Africa, the ability to travel freely from source markets to ports of entry and then on to the final destination, including crossing borders, is a key aspect (OECD, 2014). South Africa is challenged by its remote geographic location relative to non-African core markets, which translates into long travel times for many potential tourists. Tourism strategies to attract international visitors therefore not only have to improve accessibility and connections to existing and potential source markets, but also have to reduce the administrative barriers and uncertainty related to visa requirements to remain globally competitive.

Airport connections are fairly well developed. Within sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa has the most developed air transport infrastructure and ranks well with respect to the quality and the number of operating airlines (World Economic Forum, 2019). The Yamoussoukro decision on liberalising air transport across Africa, implemented in 2018 to stimulate the development of inter-African air transport and improve the quality of service to the consumers, has already had positive impacts on air access and tourism to South Africa. Through its air connectivity project, Cape Town Air Access, Cape Town has seen an estimated increase of ZAR 4.8 billion in tourism spend, due to the launch of 13 new routes and the expansion of 14 existing ones within Africa (Tourism Business Council of South Africa, 2018). The project is a collaboration of public and private sector partners. According to estimates by the Tourism Business Council, the airport capacity is sufficient to accommodate rising visitor numbers in the short to medium term. Authorities should however ensure that the long-term needs of the tourism industry are considered as part of the transport access and infrastructure planning process.

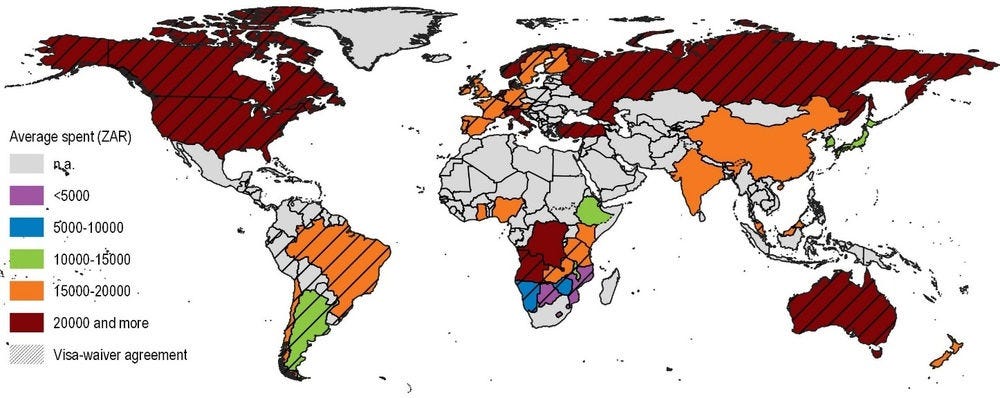

The current visa policy of South Africa is acting as a brake on growth in international tourist arrivals. Across countries, complex visa and entry procedures are well proven inhibitors of travel (OECD, 2018e). In response, countries aiming to increase international tourism take steps to better facilitate entry into the respective country. For example, the Indonesian government successfully attracted more foreign tourists by changing their visa policy in 2015 to allow citizens from 169 countries to enter the country without a visa (OECD, 2018d). As of 2019, South Africa currently had visa-waiver agreements with 76 countries in total (Figure 3.12). International tourist arrivals from countries with recently signed visa waivers have seen strong growth. For example, following the establishment of a reciprocal visa waiver with Russia in March 2017, international tourist arrivals increased by 51% compared to arrivals in 2016. By contrast, the cancellation of visa waiver arrangements with New Zealand in January 2017, led to a 23% decline in international tourists arrivals (World Tourism Organization, 2018). To increase the arrival of foreign tourists, South Africa could take steps to expand the number of countries covered by visa waiver agreements. Not only does the elimination of the administrative burden support the attractiveness of the country as a destination, but spending by foreign visitors also has a more important impact on the domestic economy that outweighs the forgone earnings from visa fees (OECD, 2018d; OECD, 2018e).

Figure 3.12. Not all sending countries with high average spend by tourists have a visa-waiver agreement

2017

Source: Based on data from South African Tourism (2018) and UNWTO.

For those countries that do not fall under visa-waiver agreements, visa-issuing procedures must be simplified. In emerging target markets that are characterised by high average tourist spending, such as China and India, no visa-waiver agreements exist (Figure 3.12). Moreover, a lack of sufficient visa issuing offices, especially in these same markets, increases the administrative and monetary burden for potential tourists. Not only does the lack of visa issuing offices increase processing times, current processes require the tourist to send in their passport. In addition, applying for a visa may also require the advance purchase of a flight ticket – without certainty of being granted the visa. As such, for many, applying for a visa to South Africa is costly both in terms of time and money. An electronic visa programme is currently piloted for citizens from New Zealand travelling to South Africa in place of the visa-waiver agreement cancelled in 2017. While the expansion of a free visa policy in core markets should be targeted, it might not be immediately feasible due to security concerns. An alternative solution would be the large-scale implementation of electronic visa programmes and the issuing of multi-year multi-entry visas to reduce the administrative burden for potential and repeating tourists by saving visitor’s time and money. These steps are currently discussed by the respective authorities and would significantly improve administrative procedures, and thus turn South Africa into a more competitive and attractive destination for tourists.

Facilitating and clarifying current rules for entering South Africa could reduce unnecessary burden for travellers. In 2015, the Department of Home Affairs introduced a visa regime that required minor travellers wishing to enter or leave the country to produce an unabridged birth certificate, regardless of whether the country falls under a visa-waiver scheme or not. In addition, written permission from both parents or legal guardians to enter or leave the country might be requested in some cases. Although an amendment in 2018 resulted in a slight change of wording, uncertainties remain as minor travellers who are foreign nationals and who are visa exempt are still advised to carry the unabridged birth certificate. While it is no longer a legal requirement, entry might be prohibited if relevant documentation for minors cannot be produced when requested. Rules regarding travelling minors should be clarified, communicated effectively, and where feasible removed to facilitate travel.

Regional visa agreements could increase travel mobility within wider Southern Africa while supporting regional integration. The last economic survey highlighted the need to strengthen regional integration in the South African Development Community (SADC) to broaden economic opportunities (OECD, 2017e). Regional visa agreements could increase overall attractiveness for overseas tourists travelling to the region. Instead of going through visa processing procedures for each individual country, a regional visa agreement would facilitate travel mobility and flow of visitors between participating countries (OECD, 2018a). Already, several regional economic communities offer multi-destination visas such as the East Africa Tourist Visa as well as visa-free travel such as in the Economic Community of West African States to boost regional tourism. Although the KAZA Univisa has been introduced in the SADC region, this regional visa currently only covers Zambia, Zimbabwe, and park visits in Botswana allowing holders to travel between these areas. Broadening the scope of KAZA Univisa schemes should be advanced. The more countries able to join whilst maintaining border security, the better it will be for the attractiveness of participating destinations. It also allows the participating governments to share the burden of processing, security screening and administration (OECD, 2018a).

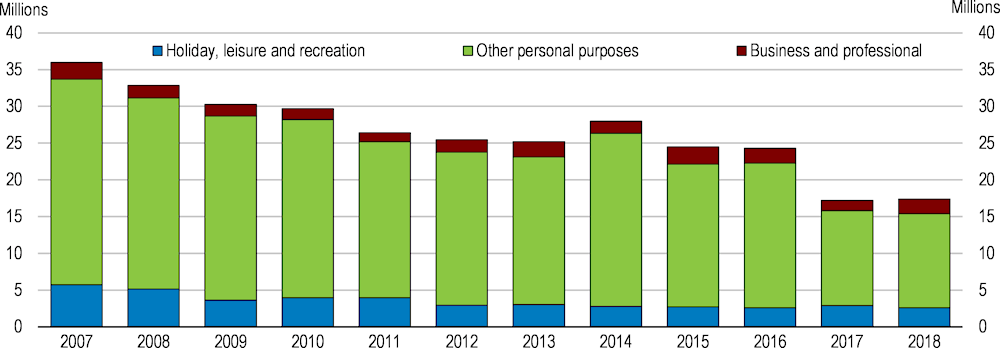

Domestic tourism

Domestic tourism has the potential to reduce exposure to seasonality of inbound tourism, promote economic development in rural and regional areas and improve the local tourism culture. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, reduced international flights and many travel restrictions imposed by countries in place, domestic tourism has the potential to be the main driver to recover the tourism sector (OECD, 2020b). A main challenge facing the South African tourism sector is how to grow domestic tourism on the back of tough economic conditions in the country. Weak economic growth and high unemployment have put household disposable income under pressure (see KPI). Thus, over the last decade, total domestic tourism trips have declined (Figure 3.13).

Domestic tourists in South Africa are mainly visiting family and friends. Trips for the reason of holiday, leisure and recreation, which tend to create more tourism revenues, constitute only 15% of all domestic tourist trips. The biggest inhibiting factors according to respondents from the domestic tourism survey are related to affordability (40%) and that they have no reason to take a trip (23%) (South African Tourism, 2019). The lack of a tourism culture has been shaped by the legacy of apartheid, and although the composition and nature of domestic tourism has been changing since then, domestic tourism remains below its expected potential (Kruger and Douglas, 2015).

Figure 3.13. Domestic tourism trips are trending downwards

By purpose, 2007-2018

Note: Other personal purposes refer to visiting friends and family.

Source: World Tourism Organization (2019).

To create a tourism sector where domestic tourism can balance seasonality of international arrivals, the industry has responded by developing products that appeal to members across all market segments. The government developed a domestic tourism strategy focussing on creating a culture of travel for holiday leisure. Strategic actions to increase tourism volume include creating a domestic travel card similar to SANParks’ Wild Card and packaging linked experiences across the country, for example National Parks Footprint, in partnership with the industry (Department of Tourism, 2012). However, domestic tourism in South Africa is facing a lack of diversity and inclusive pricing strategies (Department of Tourism, 2018b). The domestic tourism strategy should not only focus on differentiated marketing, but also on differentiated pricing mechanisms for domestic tourists to increase accessibility to different social classes and counter seasonality. Thus, reduced entrance fees to tourism sights and attractions for local residents, low income groups and during off-season could stabilise visitor numbers. For example, several European countries have active policies combatting seasonality and promoting “Tourism for all” (e.g., Czech Republic, France, Greece, Hungary), which are primarily targeting the domestic market. Further, a number of countries (e.g., Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy) also implement programmes to reduce inequalities and support people with limited access to holidays and tourism opportunities through the implementation of holiday funding schemes or targeted actions for persons with reduced mobility (OECD, 2016b).

Ensuring tourism development translates into sustainable and inclusive growth

Tourism development does not automatically translate into inclusive growth. While the sector has the potential to create job opportunities (as described above), the benefits of tourism also have to spread into regions currently lagging behind. This is especially important in South Africa, where spatial inequalities are a legacy from the apartheid regime. However, there are risks associated with unchecked tourism growth that have to be considered, such as loss of cultural heritage and the depletion of environmental assets. Tourism policies therefore need to be planned carefully and in a holistic way taking into account the interdependencies across different sectors and allowing for input from different levels of government.

Supporting regional development through tourism

South Africa is one of the most spatially segregated and unequal countries owing to the legacy of Apartheid. Thus, provinces such as Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, and Limpopo that used to have a high concentration of “homelands” during apartheid still exhibit high poverty levels (World Bank, 2018). To address the inherited geographic inequalities, South Africa’s National Development Plan aims to leverage tourism to support regional development and reduce spatial inequalities (Rogerson, 2015). To achieve the National Development Plan’s objectives, strategies must focus on spreading tourism to lagging regions to increase its economic impact (Pearce, 1995). It is important that strategies to boost the geographic spread of tourism are co-ordinated across different levels of government and that policy objectives between policy sectors are well aligned.

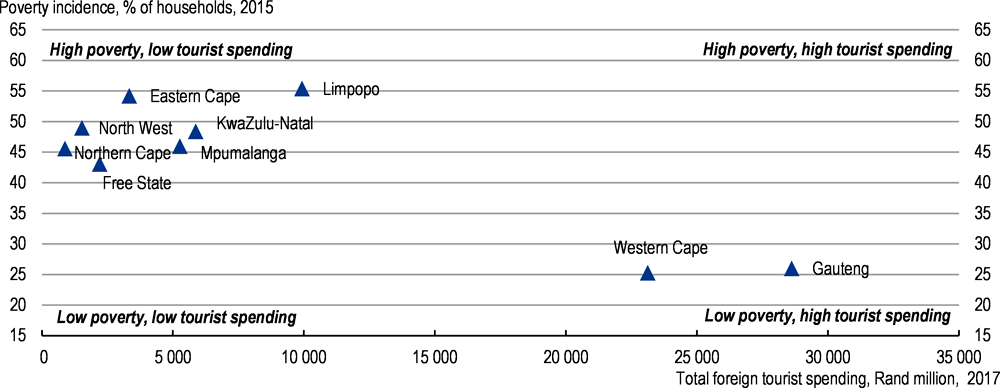

South Africa boasts a number of landmarks that are attractive to tourists but are located in distressed areas. For example, South Africa hosts 19 national parks spread across four provinces. Among them are Limpopo, Northern Cape and Mpumalanga, which are also characterised by high poverty rates. Despite the natural assets in these provinces, visitors tend to stay for a shorter period and thus average spending per foreign tourist is significantly lower than in Gauteng and Western Cape who exhibit lower poverty rates and attract more visitors and total foreign tourist spending (Figure 3.14, Table 3.2). Visitor numbers for the National parks further indicate low geographical spread of tourists into existing national parks and limited spread of benefits to other parks (South African National Parks, 2018). To spread the economic benefits of tourism more widely, the government is currently identifying priority destinations for tourism that have the potential to create spillover effects to the surrounding region. However, there is a lack of data with respect to local tourism and tourism benefits. In the context of South Africa, where tourism was historically targeted to only the white minority population, an understanding for the benefits of tourism for the local economy is missing. Providing information about the local benefit of tourism is crucial to complement targeted investment and programmes to support the development of local supply chains and create buy-in of local communities and stakeholders.

Table 3.2. International tourism indicators by province

2017

|

Arrivals |

Spend (ZAR million) |

Average Spend |

Total Bednights (thousands) |

Average length of stay (days) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gauteng |

4 052 368 |

28 618 |

7 500 |

44 468 |

11.4 |

|

Western Cape |

1 727 913 |

23 118 |

14 400 |

23 300 |

14.1 |

|

Eastern Cape |

411 408 |

3 331 |

8 700 |

4 378 |

11.2 |

|

Kwazulu Natal |

812 531 |

5 867 |

7 700 |

7 868 |

10.1 |

|

Mpumalanga |

1 573 635 |

5 260 |

3 500 |

12 759 |

8.5 |

|

Limpopo |

1 882 191 |

9 929 |

5 600 |

7 864 |

4.4 |

|

North West |

771 390 |

1 523 |

2 100 |

4 643 |

6.3 |

|

Northern Cape |

113 137 |

874 |

8 400 |

1 325 |

12.6 |

|

Free State |

1 193 083 |

2 205 |

2 100 |

13 956 |

12.2 |

Source: South African Tourism, 2018a; https://live.southafrica.net/media/229028/sat-annual-report-2017_v25_13072018.pdf.

Figure 3.14. Provinces with low poverty attract more foreign tourist spending

Local destination management is key in increasing the economic impact of tourism

Tourism plays a crucial role in many secondary and small towns in South Africa. In a recent study, McKelly et al. (2017) show that for several municipalities the role of tourism in the economy increased significantly between 2001 and 2010. Moreover, several of these areas fall within the 27 Priority Rural Districts identified by the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, incorporating several former Homeland areas. This highlights the potential of tourism to support local economies in distressed areas. However, many of the remote small towns that turn toward tourism as a vehicle for growth are located in poorer and distressed areas, and as such their local governments are likely underfunded (Rogerson, 2016). Thus, despite their legislative mandate to plan for and drive tourism development (Box 3.4), planning for tourism by local governments risks falling short of achieving its full potential due to the sheer volume of responsibilities in service delivery and financial constraints (Rogerson, 2016).

Local governments need sufficient capacity to plan for sustainable tourism development. Thus, local bodies that are able to plan and take action within destinations, as well as developing strong partnership bringing together local government and private sector businesses are crucial for effective destination management. The Ministry of Tourism has developed a Tourism Planning Toolkit for local governments to provide guidance on how to develop a basic tourism plan. Further, over 300 local government policy makers and practitioners were trained on tourism planning and implementation, in collaboration with the University of Pretoria. However, to ensure that municipalities can follow through with the tourism strategies developed at the national level, capacity at the local level has to be strengthened. For example, in Chile, experienced destination managers were assigned to local destinations to co‑ordinate tourism policies, connect private and public actors, and design and implement site-specific promotion strategies (OECD, 2017a).

Box 3.4. Governance of tourism in South Africa

Tourism policies in South Africa fall under the responsibility of national, provincial and local governments.

At the national level, the Ministry of Tourism has the oversight of the tourism portfolio and is involved in crafting policies and sector strategies. The Ministry works closely with public and private stakeholders. It also oversees South African Tourism (SAT), the public entity responsible for the country’s destination marketing.

At the provincial level, a Member of the Executive Council in each of South Africa’s nine provinces is charged with responsibility for tourism. Each province also has a provincial tourism marketing organisation, complementing the activities of SAT.

The local level (districts and municipalities) is responsible for implementation, and therefore a key partner in expanding the tourism sector through its role in initiating, facilitating and supporting the development and promotion of local tourism. Apart from planning and developing infrastructure, local government has the primary role of ensuring that the environment that both the locals and visitors encounter is clean, safe, healthy, accessible and stimulating. It is also responsible for business licensing and can therefore affect the tourism business environment.

Given the cross-cutting nature of tourism, the sector’s policies are also affected by other sectors. For example, the Department of Home Affairs is responsible for immigration and visa regulation significantly affecting tourism policies. To accommodate the complex nature of tourism, horizontal co-ordination is undertaken at the national level through the National Tourism Stakeholder Forum of the Department of Tourism. It consists of representatives of key ministries and institutions with an impact on tourism, such as Statistics South Africa, the Airline Association of Southern Africa and the Tourism Business Council of South Africa. Further, bilateral agreements between the Ministry of Tourism and other ministries allow tourism officials to work in key policy forums to ensure consideration of policy impacts on tourism.

Source: OECD (2018e).

Developing infrastructure to support regional development

To support the geographic spread of tourists into lagging regions, relevant infrastructure has to be developed. Areas that are not accessible because of lacking or bad transport infrastructure will not develop into flourishing tourism destinations. Similarly, local destinations that cannot provide supportive tourism infrastructure (e.g. accommodation) and basic services (sanitation, water, electricity) will have difficulties attracting tourists.

Transport infrastructure within and between places in South Africa is dominated by road transport. Once visitors have arrived in South Africa (either by car from neighbouring countries (70%) or by air (30%) private cars, taxis and minibuses are the most used mode of transport among international and domestic tourists alike (South African Tourism, 2017a). While this form of transport allows for the highest flexibility, it adds to the already existing pressure on traffic and road infrastructure. As tourism strategies aim for increasing tourist numbers over the coming years, more sustainable and environmentally friendly alternatives should be considered. Across OECD, convenient multimodal transport options to access destinations, efficient connections between interregional and local modes, integrated ticketing, multilingual user information and wayfinding, as well as ease of access for travellers with limited mobility have been shown to increase the geographic spread of tourists in a more environmentally friendly and less car-dependent way (OECD, 2016b). This also include the more efficient use of existing infrastructure when defining priority areas and developing tourism strategies. It is therefore crucial that transport policies are well aligned and co-ordinated with tourism policies to improve visitor mobility to and within destinations, enhance visitor satisfaction, and help to secure the economic viability of local transport systems by servicing both residents and tourists (OECD, 2016c).

Infrastructure projects that aim to increase the number of visitors cannot be developed in isolation. Besides developing infrastructure that increases visitor’s mobility, the competitiveness to attract tourists into the regions also depends on the availability of supportive infrastructure and basic services, such as sanitation, water and electricity (UNCTAD, 2017). In South Africa, there is a great variation in the capacity of local government, in terms of revenue collection, financial operations and service delivery (OECD, 2015; Statistics South Africa, 2016). Thus, especially struggling municipalities that turn towards tourism to support local growth might not be able to ensure proper service delivery. To promote the geographic spread of tourists into more remote and distressed areas requires sufficient capacity at the local level to ensure basic service delivery to support new and emerging attractions and destinations (Rogerson and Nel, 2016). Municipalities have to be supported to provide supportive infrastructure for basic services and tourism related activities. Better service delivery will create a more enjoyable visitor experience, while also contributing to better living conditions for residents in the local tourist destination.

Tourist routes are an increasingly popular initiative implemented by countries to support the geographical spread of visitors (OECD, 2016a). Rather than heavily relying on tour operators, as is still the case in many provinces in South Africa, well-marketed tourist routes can tap into the segment of tourists that prefer to plan their route individually. Digital platforms can provide information on local sights outside of main tourist hotspots complementing signage on the ground. A positive example is the well-established and well-travelled Garden Route, which stretches about 300 km along the coast from the Western to the Eastern Cape. A further tourist route is currently planned from Cape Town to Port Elizabeth, which has the potential to create spillovers to many local economies along the route. There are also 21 well-organised wine route associations in South Africa, which enjoy an increasing number of visitors (South African Tourism, 2018). The wine routes offer experiences relating to history, culture, nature and cuisine in addition to the complete wine experience (A Ferreira and Hunter, 2017). With most wine routes located outside metropolitan areas, wine tours are one example for successful rural tourism development. It is also an example how branding can be used to develop tourism. Not only have the wine tours supported tourism development in rural areas, but have also raised the profile and profitability of South African wine in general.

Specialising on events to combine infrastructure development and local destination management

Events are a dynamic and fast-growing segment that links tourism and infrastructure development. To be competitive in the bidding process and to attract business events and tourism, infrastructure in the form of hotels, convention centres and transportation systems is needed. South Africa is not only establishing itself as a business event destination, but has also hosted several large-scale events that have boosted infrastructure development and visitor numbers. Events included the Rugby World Cup (1995), the Cricket World Cup (2003) and most recently the FIFA World Cup (2010), the latter attracting almost 310 000 foreign visitors in June and July 2010 whose primary purpose was attending the World Cup (Sports and Recreation South Africa, 2012). In addition to expanding visitor numbers, major events are often a vehicle for infrastructure development. For the 2010 FIFA World Cup, South Africa invested about ZAR 11 billion (about USD 1.3 billion) into transport infrastructure – such as the upgrading of roads and the building of the Gautrain (Sports and Recreation South Africa, 2012).

Many cities, regions and countries across the OECD are devoting considerable resources to developing, attracting and supporting major events as part of a wider strategy to increase visitor numbers and expenditure. One of the fastest growing event segments is that of Meetings, Incentives, Conventions and Exhibitions (MICE). Across the African continent, South Africa is leading in the number of hosting business events (UNCTAD, 2017). About a third of international business travellers are visiting South Africa because of MICE (South African Tourism, 2018a). To boost South Africa’s strategy to attract five million additional travellers, which encompass business travellers, the National Treasury approved in 2017 a Bidding Fund to help attract more business events to South Africa. Funded with ZAR 20 million for 2017/18 and ZAR 90 million for the following three years, the Department of Tourism will be able to bid aggressively for international association conferences, meetings, incentives and exhibitions. Aligning the event strategy within the tourism strategy can support the geographic spread of tourism through the development of relevant infrastructure and counter seasonality of the holiday tourism segment (Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Major events as a catalyst for tourism development – The example of New Zealand

To ensure that events are efficiently managed and well delivered, the New Zealand Government, through New Zealand Major Events, works in partnership with the events sector. New Zealand Major Events act as an advisor to government Ministers on the value that the events industry brings to the national economy. It acts as a partner with the events sector to attract major events, boost sector capability and leverage benefits arising from events. It plays the role of investor to ensure valuable legacy outcomes that align with the Government’s Major Events Strategy are delivered. Finally, it is a one-stop-shop for event organisers to help them navigate their involvement with government (www.majorevents.govt.nz).

The Major Events Strategy highlights that from the government’s perspective, major events are considered those which i) generate significant economic, social, and cultural benefits; ii) attract significant numbers of international participants and spectators; iii) have a national profile outside the region in which they are being held; and iv) generate significant international media coverage in key markets. Potential impacts of major events include i) increased tourism revenue; ii) increased opportunities for NZ brand promotion; iii) the creation of new business and trade opportunities; iv) increased employment opportunities; and v) enhanced events sector capabilities – supported through the Major Events Resource Bank. The expected long-term outcomes of the strategy are a significant contribution to a high value economy, vibrant communities and culture, and a flourishing events sector.

In order to achieve the aims of the Strategy and maximise the potential economic benefits for New Zealand, a Major Events Development Fund was established to prioritise investment in those events with the most potential for economic return. The governance structure for the fund includes the establishment of both an Investment Panel, to provide private sector and senior public sector input into investment decisions, and a Major Events Minister’s Group, bringing together five Ministerial portfolios with event investment and leveraging interests (Economic Development; Tourism; Arts, Culture and Heritage; Foreign Affairs; Sport and Recreation). The Investment Panel will consider major event applications and make recommendations to the Ministers Group on event investment, leverage, legacy and prospecting. It is then the role of the Major Events Minister’s Group to approve or decline any recommendations made by the Major Events Investment Panel.

Source: OECD (2017b), Major events as catalysts for tourism.

Ensuring that tourism development is environmentally sustainable

Tourism in South Africa depends on its natural resources, while at the same time increasing visitor numbers can contribute to the depletion of these very same resources. Thus, in mature tourism economies, the sector plays a significant role in the consumption of energy and the generation of emissions of greenhouse gases, and contributes to fresh water and land use, biodiversity loss, and unsustainable food consumption (Haxton, 2015). As South Africa aims to become a tourism destination of global significance, it needs to address the environmental challenges that accompany increasing tourist numbers. When built upon broad stakeholder engagement and sustainable development principles, tourism has demonstrated the ability to raise awareness of cultural and environmental values, and help finance the protection and management of protected areas, and the preservation of biological diversity (OECD, 2018e).