Falilou Fall

OECD

Paul Cahu

Priscilla Fialho

OECD

Falilou Fall

OECD

Paul Cahu

Priscilla Fialho

OECD

Productivity growth has been falling for a decade, hindering improvements in living standards. Low productivity reflects, firstly, poor infrastructure in telecommunications and transport. Secondly, the regulatory environment is not always business-friendly and often raises obstacles to firm entry, exit and expansion. Combined with weak competition in important sectors, this has led to lower private investment levels, particularly, business R&D. Finally, the educational and health care systems have been unable to supply adequately skilled workers across the country. To improve productivity, public investment needs to become more effective, notably by strengthening the selection process for large infrastructure projects. A more pro-competitive business environment would let productive firms grow and foster innovation. Widening and reducing inequalities in access to education and health care would reduce skill shortages.

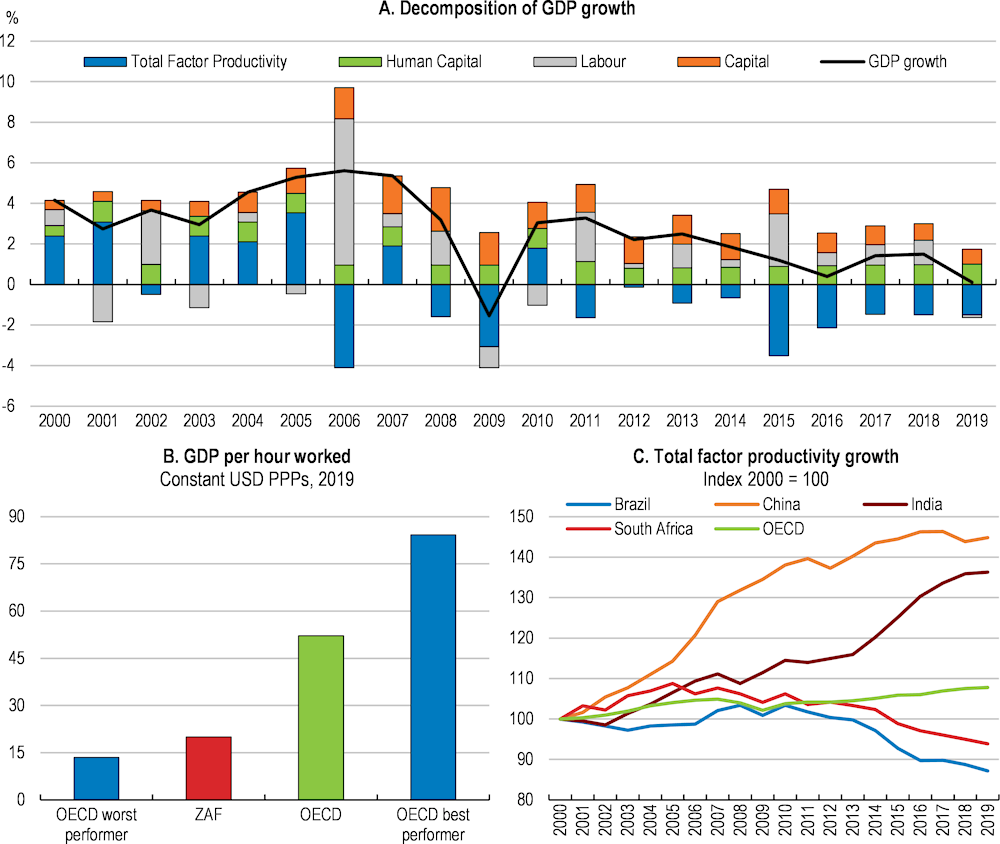

GDP per capita fell in the last decade (Figure 3.1). Over the period 2009-2019, average annual GDP growth was only 1.7% in South Africa, while it reached 2.2% for the OECD and 5.4% for BRIICS (Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, and South Africa). Population growth is set to remain dynamic, requiring much stronger economic growth for living standards to pick up. Structural bottlenecks must be addressed to put South Africa back on the convergence path.

Per capita GDP in USD, constant prices, 2015 PPPs, index 2008 = 100

Subdued economic growth is mostly explained by sluggish productivity developments (Figure 3.2, Panel A). Productivity was the dominant source of growth in the post-apartheid years, characterised by deep policy reforms, including trade liberalisation (Kumo, 2017). However, productivity remains low in international comparison and TFP growth, in particular, has lost momentum (Figure 3.2, Panel B and C). A deficit of high-quality infrastructure, namely electricity, transport and telecommunications infrastructure, regulatory barriers and severe skills shortages remain major weaknesses, preventing further productivity gains, as discussed in previous Surveys (OECD, 2020a, 2017a).

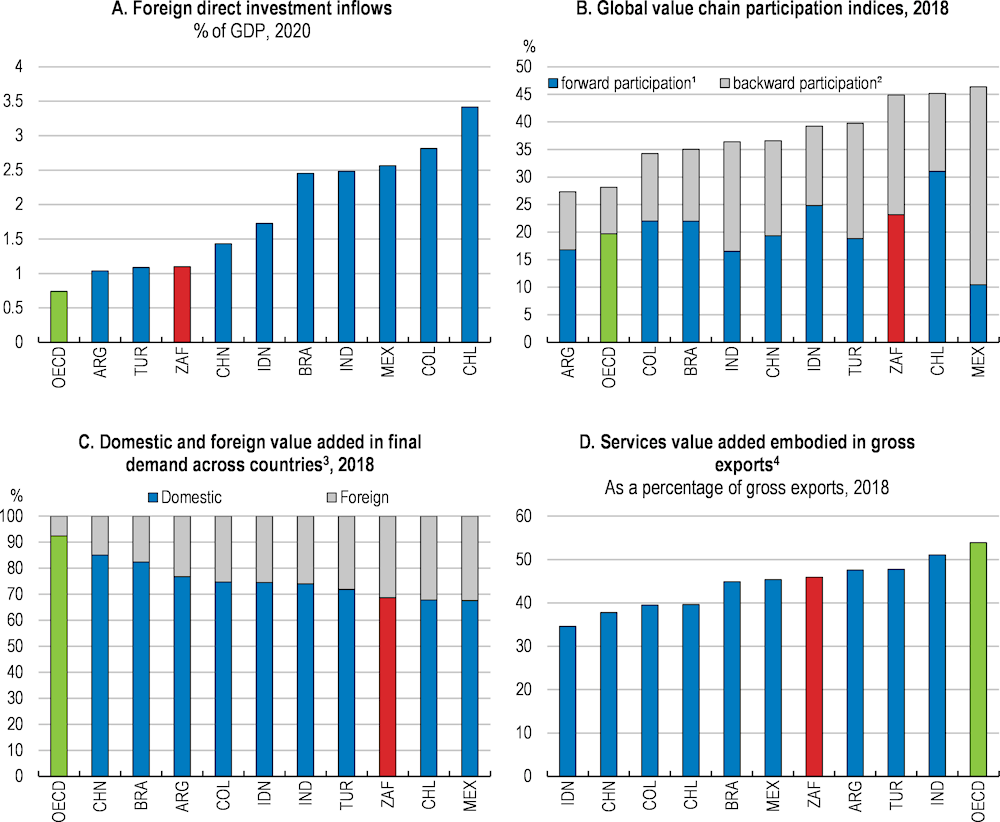

In the last decade, South Africa’s integration into global value chains has considerably improved, particularly in the mining and automotive industries (IBRD/World Bank, 2016). Inflows of foreign direct investment contributed to a better integration in global supply chains through the presence of multinationals (Figure 3.3, Panel A and B). However, such inflows remain well below other emerging economies. Weak infrastructure, difficulties in hiring qualified human resources, uncertainty about the institutional environment and social unrest are all factors hinging on investment, including foreign direct investment (Qiang et al., 2021).

The capacity of export-oriented industries to innovate remains limited, constraining South Africa’s ability to produce higher value-added in global value chains. In fact, the domestic value added embodied in exports is below the OECD average and other emerging economies (Figure 3.3, Panel C). Broadening integration to other industries is key to move-up the value-added production curve (OECD, 2015a). The services content of exports, for instance, is low by international standards (Figure 3.3, Panel D). This is particularly true for manufacturing exports (OECD, 2015a). Services from transport, logistic, branding and marketing can support export competitiveness and increase the domestic value added of manufacturing goods. Services have also become more tradeable and exporting services provides an opportunity to diversify exports.

Better business conditions are needed to attract R&D investment and to facilitate the diffusion of innovation. Start-ups and SMEs provide employment for a large proportion of the workforce, but they can also play a key role in creating and spreading new technologies and ideas. Lowering barriers to entrepreneurship and promoting small business growth would improve South Africa’s innovation system (OECD, 2017a).

Source: Penn World Tables; OECD Productivity database; OECD Analytical Database; OECD calculations.

Higher openness to trade and integration in global value chains have not generated sufficient spill- overs to firms and sectors of the economy that are not export-oriented. Exporting firms, which are also the most productive ones, are predominantly foreign owned (Fall and Längle, 2020; Edwards et al., 2008). Improving the reliability of infrastructure, in particular, transport infrastructure, creating a more business-friendly environment to enhance firm dynamism, raising skills and facilitating labour mobility would boost domestic firms’ exports, the diffusion of knowledge capital and innovative tools.

The following sections discuss policy levers to boost productivity growth. The first section focuses on increasing the quality of transport infrastructure by raising public investment efficiency. This adds to the KPI’s recommendations to improve the public transportation network and electricity infrastructure. The second section presents solutions to improve the business and regulatory environment to boost competition, firm dynamism, and innovation. This includes improving access to telecommunications. Finally, the last section identifies policies to raise human capital, which complement the KPI’s recommendations to improve the functioning of labour markets so that wages and labour movements respond better to productivity developments. The main findings and recommendations are summarised at the end of the chapter.

1. The indicator provides the share of exported goods and services used as imported inputs to produce other countries' exports. This indicator gives an indication of the contribution of domestically produced intermediates to exports in third countries.

2. The indicator measures the value of imported inputs in the overall exports of a country (the remainder being the domestic content of exports). This indicator provides an indication of the contribution of foreign industries to the exports of a country by looking at the foreign value added embodied in gross exports.

3. For manufacturing and market services, given the prominence of GVCs in these industries.

4. The indicator shows the total value added provided by the services sector in generating direct exports of services and also embodied in the exports of goods using intermediate services.

Source: OECD International Direct Investment Statistics; OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database 2021; OECD calculations.

Reliable infrastructure provides the basic foundation for productive economies. The value added of infrastructure sectors, such as utilities, transport and telecommunications, represents about 10% of GDP, on average, in OECD countries and their services explain about 12% of intermediate input costs across all industries (Demmou and Franco, 2020). Therefore, their efficient provision, which depends on high quality physical infrastructure, can be expected to increase productivity. However, the quality of infrastructure in South Africa is low in international comparison (OECD, 2020a).

Public investment is low. Although it increased recently, public investment represented only 2.9% of GDP per year, on average, between 1995 and 2019 (Figure 3.4). In particular, constrained by limited fiscal space, public investment in infrastructure – roads, bridges, dams, etc. – has dropped in recent years. As a result, the quality of transport and utility infrastructure ranks low by international comparison (OECD, 2020a). Essential services, such as electricity delivery and transportation, are severely impacted by the lack of high-quality public infrastructure, pushing up the cost of doing business and weighing on investment and productivity. Electricity shortages, for instance, are increasingly frequent (see KPI chapter).

Investment in public infrastructure has also been inefficient. Investment in the road network and its maintenance, for instance, seem close to the OECD average. However, road fatalities are still the highest in the OECD, pointing to inefficiencies in those investments (Figure 3.5). About 80% of roads are still unpaved and more than 50% of unpaved roads and between 20-30% of paved roads are either in poor or very poor condition (SAICE, 2017). A high public debt burden and increasing financing costs mean that inefficiencies in the public infrastructure investment process must be addressed. Public spending needs to effectively translate into higher quality infrastructure.

Public investment as % of GDP, 1995-2019 and 2015-2019

Road maintenance should be conducted regularly to prevent damages and repairs should not be delayed. The road network is used intensively for business transportation, with 90% of goods moved by heavy trucks, and the number of road users increased by 64% between 2005 and 2020 (Department of Transport, 2017). Trucks and heavy vehicles wear out the surface of the roads, which are also damaged by extreme weather, including large variations of temperatures and violent rainfalls. The Transportation Department estimates that the backlog of road repairs has reached ZAR 197 billion, twice the amount needed in 2010. According to the South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL), delays in road maintenance of 3 to 5 years increase the required repair costs between 6 and 18 times. The government has put in place a technical task team – the Budget Facility for Infrastructure – to identify priorities and assess the resources needed, which is a step in the right direction. This task team should be endowed with the needed human and financial resources. The funding of road infrastructure from the general government budget needs to be adapted accordingly and maintenance projects selected based on cost-benefit analyses.

The governance of road infrastructure should be revised to increase the accountability and transparency of road maintenance and repair. SANRAL is only managing 3.6% of paved roads, although they are the busiest: 35% of passenger vehicles traffic and 70% of long-distance freight are using them. The maintenance of the remaining roads is mostly left to local authorities, whose budgets are under fiscal pressure. Management of the remaining paved roads is split almost evenly between provinces, metro areas and municipalities. Provinces and municipalities manage unpaved roads. About 17.5% of road infrastructure are un-proclaimed roads, meaning that they have not been formally retroceded to public bodies after being built and are not managed by any authority. A real-time accounting of the state of the road network is needed to ensure that local authorities fulfil their maintenance duties.

The financing of road infrastructure must increase, and sources of revenues should be reconsidered. The funding for road infrastructure mostly relies on fuel levies and electronic tolls, which are based on a relatively low number of users. Spain, Thailand, or Australia, for example, have a road network similar in length, but the number of users is two to four times higher (van Resburg and Krygsman, 2019). Hence, South Africa does not raise sufficient revenues to finance its wide network. In addition, fuel levies do not cover the real cost of use by heavy trucks. South Africa should consider linking taxation to the weight of vehicles since it would follow the user-pays principle. In addition, revenues from tolls could be complemented by general taxation of value added or business income, as corporations are the main responsible for road abrasion.

An enforcement mechanism should be developed at the national level to allow road operators to retrieve outstanding e-toll debt. E-tolls, which automatically bill users of some road sections by scanning licence plates, have been ineffective in collecting revenues. About 80% of users refuse to pay and operators have been unable to enforce payments linked to the highway around Johannesburg and Pretoria. A state enforcement agency should get involved, issuing infringement notices, adding penalties to the debt, and potentially taking legal action, in which case court administrative fees should also be added to the debt. In Australia, for example, once the state enforcement agency is involved, a range of outcomes might be imposed, including licence restrictions or suspensions, wage deductions or even property seizures. In extreme cases, non-compliance can lead to a jail sentence. Alternatively, if the previous solution appears too difficult to implement, South Africa could develop a pre-payment and mobile payment system for e-tolls, while keeping a physical barrier that would only open if the pre-payment has been made, which is the norm in most of OECD countries. This would facilitate revenue collection and help reduce congestion at the same time.

Road maintenance funds should be proportional to incurred maintenance costs and monitoring should occur systematically. Fuel levies and tolls are allocated to SANRAL and local authorities without any conditions. In addition, there is little monitoring of their use. This system offers no incentives to spend funds efficiently or to concentrate spending on the most important part of the network. Instead, funding could be allocated to SANRAL and local authorities in the form of grants. Grants could be provisionally allocated at the beginning of each year depending on the average annual road traffic under each operator’s jurisdiction or based on a national strategic plan and identified priorities, as discussed above. Grants could then be distributed in different stages, conditional on planned maintenance works, progress reports, proof of incurred costs and controls, without exceeding the initially allocated amount. Authorities that do not use the integrity of their provisional share of the grant should be able to transfer the unused funds to the following year.

Technical standards used to build roads should be strengthened to slowdown road deterioration. Roads tend to be less durable in South Africa as they are built using much less bitumen than in European countries. The asphalt layer is typically about 5 cm thick versus 15 cm to 20 cm in the Northern hemisphere, leading to accelerated erosion (Visser, 2017). In addition, most of the roads have been designed for up to 8.2-ton axles, which is below the legal limit of 9 tons. Controls should take place regularly to enforce such technical standards.

Enforcement and compliance with truck traffic management policies must improve. Following the mining boom, the quantity of ores and minerals moved by roads has skyrocketed, pushing heavier trucks with little to no enforcement of weight limits on the roads. Overloading is causing the pavement surface to crack, leading to potholes and rapid destabilisation of the under layers in the absence of rapid repairs. Truck traffic should be monitored during adverse weather. In Sweden or Finland, for instance, truck traffic is limited to vehicles equipped with central tyre inflation, which checks the tyre pressure in real time during the thawing season. In European countries, additional load capacity is provided to trucks using a three-axle tractor for container movements, which restrains overloading. In Austria, abnormally heavy transports are restricted to certain time slots with low traffic, requiring a special permission while low speed limits are enforced to relieve the pavement (OECD/ITF, 2018).

The heavy road traffic and the deterioration of roads is partly explained by the lack of multimodal transport. The obsolete rail equipment has resulted in low performance and operationally inefficient rail transportation services, which are unable to support exports (Department of Transport, 2017). South Africa has a wide rail network spanning the entire country and accounting for the majority of rail traffic on the African continent. However, rail’s share of passengers and freight traffic has been falling in recent years. Lack of rail infrastructure maintenance, as well as theft and vandalism of rail assets, have lowered the attractiveness and competitiveness of both passenger and freight rail transportation (George et al., 2018).

Despite recent announcements and ongoing efforts to improve rail capacity, further actions could be taken to accelerate the development of the rail network. The government has announced plans to build a new rail corridor between Gauteng and the Eastern Cape to reduce road congestion around Durban’s airport. The government is also conducting a feasibility study to introduce a high-speed rail line between Pretoria, Johannesburg, and Durban. Encouraging private sector participation and putting regulation in place to prevent abuse of market power, as recommended in previous surveys, would encourage railway capacity development and modernisation (OECD, 2015a). The planned establishment of a Transport Economic Regulator could facilitate private sector involvement in the rail sector by regulating sector entry in a more transparent way. Ongoing reforms to open access to the freight rail network to third-party operators are also welcome. Maintenance for the railway network should be focused on the lines with a potential for development and underutilised infrastructure should be sold. Coordination and liaison between railways and other modes of transport should be enhanced. The rail network should reach the main airports and ports without requiring any road connection.

Productivity and global trade have also been hampered by ageing port infrastructure and equipment. The National Ports Authority (NPA), a subsidiary of Transnet, manages ports. At the same time, port services are provided by various subsidiaries of the same company, which all operate as monopolies. Lack of competition in port services has contributed to lower investment, higher tariffs, and a diversion of sea traffic away from South African ports. In the “Container Port Performance Index 2020” released by the World Bank, South African ports rank at the bottom of the international ladder, in the 347th, 349th and 351st positions out of 351 ports. In a welcome move, the president announced in June that the NPA will be corporatized and established as an independent subsidiary of Transnet, with its own separated board appointed by the Public Enterprises minister. This will create a separation between the owner of the port facility and the terminal operator, Transnet Port Terminals. Following the reform, revenues generated by ports will be invested in port infrastructure to upgrade and expand facilities, rather than being diverted by Transnet and its subsidiaries to cross-subsidise unrelated activities. This reform should be one of the government’s priorities to improve transportation infrastructure.

Corruption allegations, and in particular allegations of state capture, often surround infrastructure projects, undermining their cost-effectiveness. The scale and complexity of the projects, as well as the multiplicity of stages and stakeholders involved, make infrastructure projects highly vulnerable to corruption (OECD, 2017b). Anti-corruption provisions are among the most relevant features influencing productivity growth for firms operating in infrastructure dependent sectors (Demmou and Franco, 2020). Reforming the National Prosecuting Authority to increase its independence and speed-up the judicial response to corruption cases would contribute to reduce inefficiencies in the selection, tendering, implementation, and control phases of infrastructure projects (KPI Chapter). In addition, the OECD Integrity Framework for Public Investment proposes a set of specifically tailored measures seeking to safeguard integrity at each phase of infrastructure projects (OECD, 2016). For example, the design of tender documents should not be restrictive and tailored, the use of confidential information by public officials should be limited and regulated, and audit functions should have adequate capacity and resources to perform independent and reliable controls. Finally, the publication of cost-benefit analyses of transport projects could be mandatory, with justification of policy-makers’ choices.

To climb up the value chain and increase the domestic content in exports, South Africa needs to place more emphasis on innovation and the accumulation of knowledge-based capital as drivers of long-term growth. Digitalisation is key to support innovation and is associated with significant productivity gains at the firm level (Gal et al., 2019). Widely accessible high-speed broadband is crucial for firms to adopt new digital technologies. Supporting the development of new technologies also requires ambitious R&D policies. Finally, competitive product markets would help generate knowledge spillovers from FDI and exporting firms to domestic firms, as well as a more efficient allocation of capital and labour towards the most productive firms. State intervention and regulatory barriers have hampered market entry and the efficient reallocation of resources (OECD, 2020a).

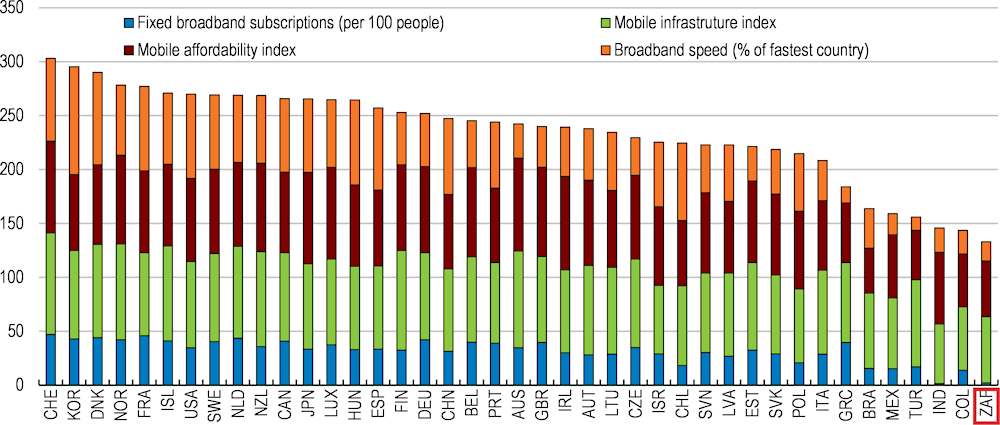

Lagging telecommunication infrastructure is slowing down the digitalisation of South African firms. Access to broadband connection is low and only 2.4% of inhabitants have subscribed to high-speed internet (Figure 3.7). Broadband speed is also low by international comparison and subscription fees remain high (Figure 3.6). The roll out of fibre has been slow and undertaken by nine private companies without coordination. Many high-income areas are over-served while the rest of the country remains unconnected. Telkom, the former national company, has by far the longest network, with 55% of the cable length, but the company stopped the rollout of fibre to concentrate on mobile connectivity. The government needs to ensure that all citizens have access to high-speed internet networks (OECD, 2021e). As the cost of infrastructure is much higher in less populated areas, the government can boost connectivity by subsidising the expansion of the network outside of city centres through conditional grants, as done in Spain. The condition would be that any infrastructure built using public funds should be openly accessible to all players on similar terms (Box 3.1). Such grants should be attributed based on carefully conducted cost-benefit analyses to identify where the expansion of high-speed internet should be prioritised. The government’s South Africa Connect programme seeks to achieve 80% broadband access in communities and government facilities over the next three years with a minimum speed capacity of 10 Mbps per second and 100 Mbps for the high-demand facilities. Furthermore, the Rapid Deployment programme intends to provide a clear framework for the rollout of telecommunications infrastructure such as fibre and network towers, enabling this infrastructure to be deployed across the country with greater speed and reduced cost. Given that other infrastructure are needed in many parts of the country, the government should take advantage of any public construction works to install open-access telecom infrastructure along the way.

Access to mobile communication remains too expensive. Competition in mobile telecommunications has improved recently, when a fifth actor entered the market in 2017, but this has not yet reduced the price of communication (Motaung, 2021). The OECD product market regulation (PMR) index for the telecommunication sector, both fixed and mobile, points to a high level of regulatory barriers in the South African market compared to the OECD average, as discussed below.

Spain enjoys one of the largest access to fibre in the OECD, but the country suffers from large urban-rural inequalities. As in most OECD countries, the roll out of fibre has been undertaken mostly by private firms. To compensate for the lack of attractiveness of rural and remote areas for commercial operators, the government provided financial support for the rollout of broadband networks, in particular, in towns with less than 1 000 inhabitants, through public grants. In 2019, Spain allocated 140M EUR for the connection of half a million people. In 2022, another 400M EUR will be granted to provide high-speed internet in less connected areas.

Source: OECD (2021d), “OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2021”, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/79e92d88-en.

Mobile internet connectivity is limited by a lack of attributed frequencies. After two previous failed attempts in 2010 and 2016, the regulator tried to auction a low-frequency band (700-800 MHz) of the spectrum at the end of 2020. However, the court halted the process following complaints that the low-frequency band is already being used to broadcast television and using it to develop mobile internet could cause signal disruption. The difficulty to share the frequency spectrum can be bypassed by forcing operators to open their network to Mobile Virtual Networks Operators (MVNO), like in Denmark (Box 3.2). MVNOs are mobile services providers that do not own the wireless network infrastructure but rely on agreements with operators allowing them to buy access in bulk at wholesale rates. Only two operators, Cell C and MTN are currently selling access to their infrastructure to MVNOs while Vodacom has been waiting for the end of the spectrum auction, limiting the opening of the markets to MVNOs. There is currently no requirement to share infrastructure with MVNOs and ventures in that market have not been successful, as the market share of MVNOs in the country remains around 2%. It might not be efficient to wait for the deployment of 5G mobile network to support the emergence of MNVOs in South Africa since the mobile infrastructure is not yet widespread.

Performance and availability of the internet network, 2020

Source: GMSA (Mobile Connectivity Index), speedtest.net (broadband speed in Mbit/s), OECD and World Bank (Fixed broadband subscriptions).

MVNOs were first introduced in Denmark in 2000. Their market share is now about 34%. Mandatory access to MVNOs was also imposed in Ireland and France following a 2003 audit by the European Commission. In 2012, the French regulator has also been setting maximum tariffs, which have been decreased over time to enhance the development of competition. The market share of MVNOs is about 9% in France and about 12% in Ireland. Other countries such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia and India have amended their legislation to allow MVNOs to enter the market. Although they may not represent large market shares, typically up to 10 to 15%, MVNOs tend to lower prices of larger players through competition.

Source: OECD (2014b), "Wireless Market Structures and Network Sharing", OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 243, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxt46dzl9r2-en.

The public administration should deliver services digitally, whenever possible, to increase incentives for faster digital adoption and lead by example. In most OECD countries, the digital transformation of governments has proven effective in the way governments interact with and deliver services to their citizens. It can also help spur much needed digitalisation in the private sector. The digital transformation of governments is also generally associated with increased administrative efficiency, lower transaction time and costs, and closer contact between citizens and the public administration (OECD, 2021b, 2021c).

South Africa has made significant efforts in recent years to modernise government operations by introducing various e-Government systems, for instance. As a result, it has the second highest e-Government Development Index (EDGI) in the African continent. However, access to these e-Government solutions is highly unequal across the country (Masinde and Mkhonto, 2019). Cape Town, for example, ranks second in the 2018 United Nations Local Online Service Index, which assesses forty local governments in the world. In contrast, and as discussed above, in many rural municipalities, access to telecommunication infrastructures remains limited. Common service centres across rural municipalities could improve access to telecommunications, as well as digital government services. Employees of common service centres should be provided with adequate ICT skills so they can assist rural citizens when using these services.

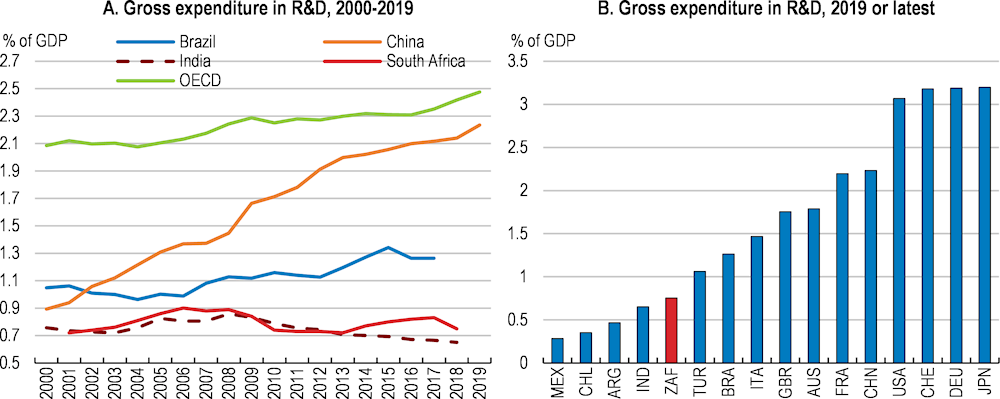

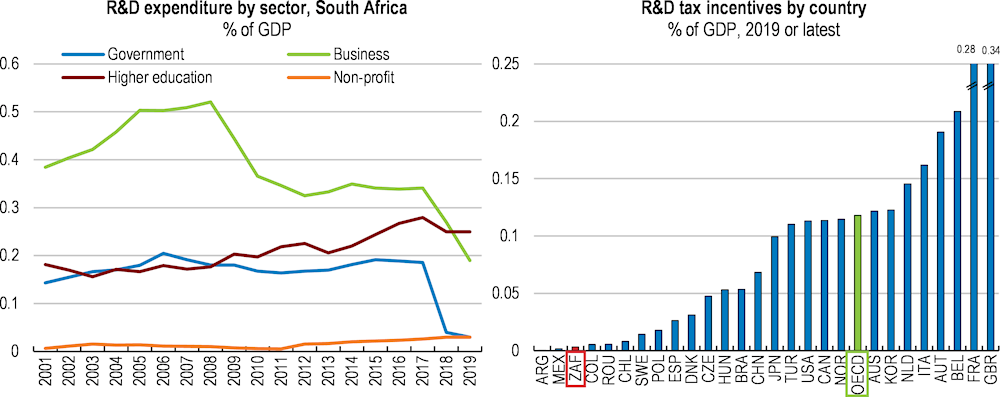

Spending in R&D as a share of GDP has barely evolved as a share of GDP since 2006 and is well below OECD countries and peers (Figure 3.8). In addition, R&D staff are less numerous in South Africa than in OECD countries. In 2018, there were around 1.8 R&D staff per 1,000 people employed in South Africa, which is about five times less than in OECD countries (Figure 3.9, Panel A). Innovation outputs are also low by international standards. The number of patents, for example, remains limited and has not evolved favourably in recent years. Patents granted to South-Africa fell by 20% from 2008 to 2020 while they increased by 103% in all OECD and BRIICS countries (Figure 3.9, Panel B).

Source: OECD Analytical Database; OECD Main Science and Technology Indicators; OECD calculations.

Business R&D expenditure, in particular, has declined alarmingly since 2008 (Figure 3.10, Panel A). This is especially concerning as business R&D has high spillover effects and enhances the ability of the business sector to absorb technology coming from abroad or from government and university (Guellec and van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, 2001). Private R&D spending is likely constrained by the unfavourable investment climate and the level of corruption, which remains high in South Africa (chapter 1). Such bottlenecks to private investment need to be addressed if South Africa is to reach its target of doubling business R&D spending to 1% of GDP by 2024).

Public support for business R&D, taking into account direct financing through grants and calls for projects, remains very low. Support for business R&D in South Africa is about 14 times smaller than in OECD countries, at 0.013% of GDP versus 0.184% (OECD R&D Tax Incentives Database, December 2021). R&D spending claimed by businesses from the tax administration in the context of the tax relief scheme has been falling continuously since the introduction of the pre-approval system in 2012 and is low by international comparison (Figure 3.10, Panel B). The scheme, which reimburses up to 150% of the qualifying expenditure incurred without any cap, leads to an implicit subsidy rate of R&D spending of 0.15%, below the OECD median of 0.20% (OECD R&D Tax Incentives Database, December 2021). Administrative delays and backlogs associated with the pre-approval system are likely to explain the lack of attractiveness for this tax incentive scheme (OECD, 2021f; OECD, 2020c). The government is currently testing an on-line application system that could simplify the procedure and accelerate the processing of applications.

The R&D tax incentive scheme should be thoroughly evaluated to assess its effectiveness. The evaluation results could then inform the decision of whether to continue the scheme beyond September 2022, when it is supposed to expire, and whether changes to the programme are required. A recent report suggests that firms benefiting from this tax incentive would have invested in R&D even without the programme (World Bank, 2019; National Treasury, 2021). However, firms that received incentives do not always comply with progress reporting, which makes assessing the programme’s effectiveness particularly difficult. Less than a third of firms that received the incentive submitted progress reports. Digital tools could be used to improve the monitoring of supported projects. Progress reports could, for example, be submitted online. Progress reports could be required to reapply or to roll over the incentive each year. Finally, different departments should work together to gather data on R&D spending, profits, employment and patent registry, before and after the introduction of the programme, and obtain a better estimate of the costs and benefits of the programme.

Direct public financing of business R&D through matching grants and calls for projects are critical to boost business R&D spending and can effectively complement indirect support measures. Generous tax incentives have a positive, but limited impact on business R&D. Direct government funding, on the other hand, has proved quite effective (Westmore, 2014). While tax incentives are associated with higher levels of experimental development, direct financing seems more conducive to promoting basic and applied research (OECD, 2020d). Matching grants, whereby businesses commit to match public funding with private spending in a given proportion, allows fiscal spending to be more aligned to market signals. Direct funding of R&D projects by the government, using competitive calls for projects, like those regularly launched by the European Union, should also be considered (Box 3.3).

R&D spending by source and tax incentives for R&D

Source: OECD Science and Technology Indicators; OECD R&D Tax Incentive Indicators; South African National Survey of Research and Experimental Development Statistical Report 2019/20; OECD calculations.

The European Union is financing R&D thanks to successive seven-year programmes of public funds. The programme finances research and innovation projects through grants distributed through a call for projects, with a specific focus on market-oriented innovations. Procedures and red tape have been minimised and funding can be disbursed within 100 days after closure of the call for projects. Access to the programme is very broad, allowing all innovators to compete. The programme is structured around challenges rather than disciplines, supporting interdisciplinary initiatives. The scale of the programme, as a share of GDP, is modest, representing less than 0.1% of GDP, but its visibility helps rewarded R&D projects to levy additional funds as the programme is focussed on excellence and relevance for the society. Horizon 2020, the research programme for the years 2014 to 2020 benefited to more than 150,000 participants and led to almost 100,000 peer-reviewed publications and around 2,500 patent applications and trademarks.

Source: Appelt, S., F. Galindo-Rueda and A. González Cabral (2019).

Competition policy can greatly influence the incentives for private firms to incur the costs necessary to produce inventions (Shapiro, 2001). Low competition supports incumbent firms, limits private R&D spending and patents granted. Decreasing the Product Market Regulation index by one unit can increase business R&D spending by 15% in OECD countries, in the long run (Westmore, 2014). Measures to improve the competition regulatory framework, as discussed later in this section, are likely to be beneficial for business R&D and innovation.

Training of scientific and technical personnel is another important driver of innovation. The cost for studying is now a major barrier to the supply of qualified human resources. In addition, the quality of tertiary education remains a constraint for the R&D sector (discussed in the next section). South Africa should consider a multi-year competitive funding programme allowing universities to enlarge their infrastructure and invest in competitive scientific equipment, following what has been done in France and Germany, for example (Box 3.4). Collaboration between universities, research units and the private sector should be strengthened. For that purpose, research collaboration with innovative companies could be included in the assessment of universities and public research institutions when determining funding allocation.

Promoting the creation of better universities through mergers in France

The plan “campus”, announced in 2008, allocated more than 5 billion EUR for infrastructure and scientific equipment in 12 campuses through a competitive process. The plan created a strong incentive for the best universities and public research institutes to merge with their nearby peers. Universities were granted financial autonomy, supported by a three-year temporary increase in state funding, leading to a consolidation of the university landscape in France. The objective of this policy was to improve the position of French universities in international rankings, as visibility is strongly dependent of institutions’ size and focus on excellency. More than a decade after being announced, the position of the new French universities has steadily improved, with the largest, Paris-Saclay University, topping the Continental Europe Shanghai rating in 2020.

Modulating public finance towards excellency in Germany

Germany launched its German Universities Excellency Initiative in 2006 to strengthen its best universities in order to raise their international visibility in a context of egalitarian public funding of the higher education landscape. The initiative delivered additional funding to boost research through three mechanisms: the establishment of research schools for young scientists and PhD students, the creation of clusters to pair research institutes and universities and the funding of institutional strategies of the best universities to promote research outcomes.

Source: Scotto (2013); https://www.dfg.de/en/research_funding/programmes/excellence_initiative/.

Despite South Africa’s well-developed banking sector and equity market, access to finance for start-ups and small businesses remains limited and more difficult than in OECD and emerging countries (Figure 3.11). Lack of financing is not only a barrier to firm creation and SME expansion, but it is also a barrier to investment in business R&D and innovation. Most banks require collateral for lending, while most citizens do not have assets to guarantee a loan and rely on savings from family and friends (OECD, 2017a).

SME lending as a percentage of total business lending for South Africa (2016) and other countries (2018)

Source: OECD (2018), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2018: An OECD Scoreboard. OECD (2020). Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2020: An OECD Scoreboard.

Government loan guarantees can help overcoming binding collateral constraints. Government loan guarantees to SMEs were part of the 2020 response to the Covid-19 crisis. About ZAR 18 billion were disbursed by banks under the Covid-19 Loan Guarantee Scheme, which was extended for a few months in the spring. This volume is well under the ZAR 200 billion provided by the Central Bank and reflects the lack of demand from SMEs given the legal and economic uncertainties. Providing advice and support to borrowers and lenders could make such loans more attractive, easier to use and could increase take-up.

The home ownership rate is relatively high in South Africa and immovable property could be used as collateral by young firms with a short credit history. To that end, property rights need to be clearly defined and insolvency procedures should be timely so that the value of the collateral can be quickly recovered by banks. A comprehensive registry of movable assets would also improve access to credit by facilitating their use as collateral, as recommended in previous surveys (OECD, 2020a, 2017a). Regulation could also be adapted to foster the use of crowdfunding, regulatory sandboxes and factoring (OECD, 2017a). For example, investor protection regulation should explicitly take such financial innovations into account to increase investors’ appetite for online funding platforms. Finally, removing barriers to entry in the banking sector, and in particular to foreign banks, would increase the range of financing options available and lower financing costs by spurring competition. Barriers to entry in the banking sector include minimum capital requirements, having a physical presence, access to clearance and payments and limitations on exit (Lewis and Gasealahwe, 2017).

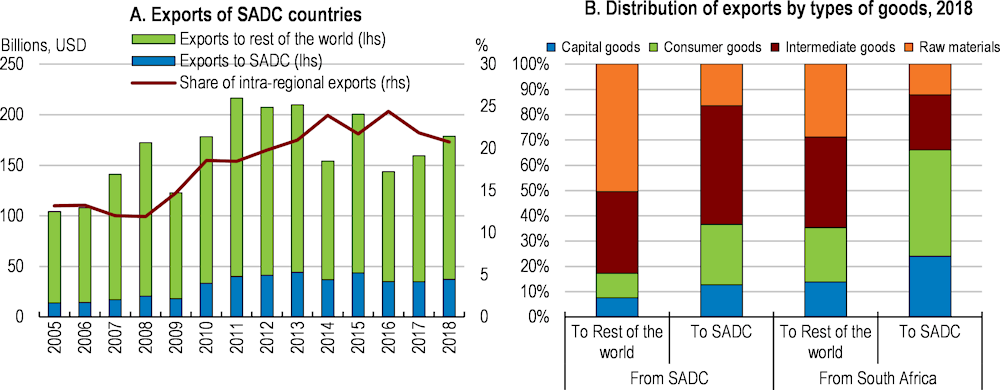

Younger businesses are generally associated with higher employment growth, and they also play a key role in enhancing innovation (OECD, 2017c; Criscuolo et al., 2014). In South Africa, the entry rate of formal sector firms has been below the exit rate in recent years, meaning that firms are growing older. In addition, the start-up rate is low compared to OECD countries (Tsebe et al., 2018). Heavy and complex regulations, leading to excessive red tape and burdensome bureaucratic procedures, are a major obstacle to firm entry (Figure 3.12). South Africa’s retail sector is more heavily regulated than those of OECD countries and of those of other emerging economies (PMR, 2018) and procedures to start a business are numerous and time consuming. The development of digital government solutions, as discussed previously, and especially public services to businesses, would reduce the administrative burden on enterprises. Adopting a “silence is consent” rule for administrative procedures, when appropriate, would also contribute to lower the time required to start a business. For example, this rule could be adopted for issuing permits and licences to low-risk businesses.

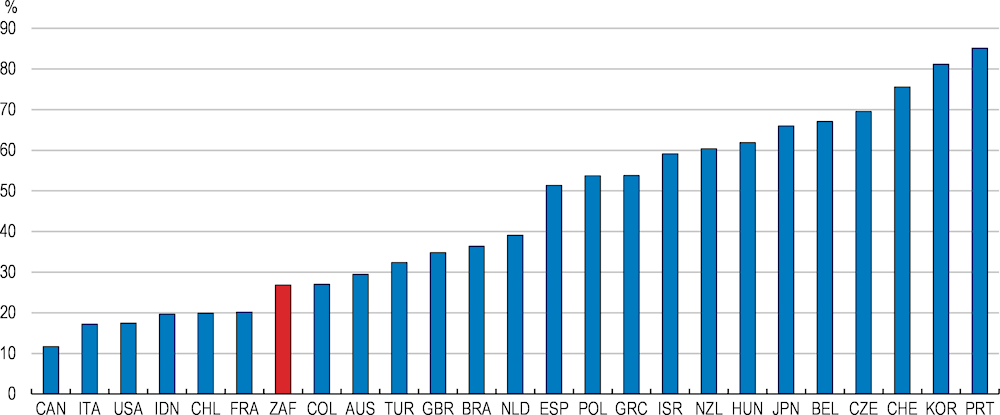

Professional occupations, such as lawyers, real estate agents, civil engineers or architects, are heavily regulated. Becoming a lawyer can be quite cumbersome and costly (Figure 3.13). High entry barriers in professional services hamper occupational mobility and the efficient allocation of labour resources (Bambalaite et al., 2020). In addition, it increases the cost of legal and other professional services. Reducing these barriers could increase GDP growth by up to half a percentage point (World Bank, 2016). Access to professional services should therefore be facilitated by lowering licensing restrictions. Another option would be to recognise foreign qualifications with clear criteria. Lowering barriers to foreign suppliers of professional services would also contribute to bridging the skill gap (discussed below).

There is scope to improve the insolvency regime. Procedures are still managed by regular courts of law, which tend to move slowly, preventing entrepreneurs to rebound as they remain cut off from financing in the meantime. Bankruptcy is not accessible to individuals without income or assets, which reduces the pool of possible entrepreneurs and slows down business restructuring, in a country where 50% of citizens have negative wealth (Chatterjee and al., 2020). Insolvency procedures need to be shortened, moved away from courts as much as possible and simplified for informal businesses. Streamlining insolvency procedures would ease market exit for unproductive firms and facilitate the efficient reallocation of labour and capital to more productive firms (Adelet McGowan et al., 2017).

Note: The sub-indicator for entry regulation in professional services is re-scaled from the original 0-3 to the standard 0-6 PMR indicator range.

Source: OECD Product Market Regulation database.

Increased levels of competition are key in steering firm dynamics, productivity, and income growth. A competitive environment between firms leads to better allocation of resources and stimulates firms to innovate and upgrade their technology, inputs, and management practices (Amiti and Konings, 2007; Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007). It also reduces firms’ market power, increasing quantities produced and lowering consumer prices (Argent and Begazo, 2015). Importantly, these effects have a pro-poor bias, as economic growth is the main driver of lower poverty and lower prices tend to disproportionately benefit poorer households, who typically consume a greater share of their income (Inchauste et al., 2014; OECD, 2015b).

Concentration in product markets in South Africa is sizeable, especially in manufacturing (World Bank, 2016; Buthelezi, Mtani and Mncube, 2019; OECD, 2020e). While market concentration may not necessarily be detrimental, it is often accompanied by low market contestability, which then translates into a significant drag on economic development. Estimates indicate that a ten percent reduction in manufacturing firms’ mark-ups is associated with increased productivity growth by over two percent per year (Aghion, Braun and Fedderke, 2008).

The competition authority has been continuously acting to preserve the integrity of markets over the last two decades. It has strong power and valuable levers, including the Corporate Leniency Policy, that allow to detect and sanction anticompetitive practices, as recently illustrated in food, pharmaceutical and concrete products markets (Mncube, 2013; Khumalo, Mashiane and Roberts, 2014). The Competition Amendment Act adopted in 2018 represents an important step in strengthening the powers of the competition authority. It reinforces its capacity to pursuit abuse of dominance, to run market inquiries and provide remedies to change the market outcomes. A market inquiry is a general investigation into the state, nature and form of competition in a market, rather than a narrow investigation of a specific conduct by any particular firm. The Commission is proactively using its market inquiries possibilities and has investigated the banking sector, the Liquefied Petroleum Gas sector, the public passenger transport, and health sector and retail markets. These inquiries led to recommendations to the government and to sector regulators to better include competition objectives in their policies.

One of the objectives of the Competition Commission is to make sure that SMEs and micro enterprises have a fair access to markets, including in subcontracts from big firms. This requires complementary policies in terms of access to capital and knowledge to facilitate market access by smaller firms. In particular, streamlining the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) framework would facilitate access to real partnerships and financing without hampering competition.

While ex-post competition enforcement has an important role in deterring anticompetitive practices, its effectiveness is limited by the existence of ex-ante conditions that favour collusion. The limited number of players in key markets, for instance, led to repeated interaction, re-offences and the creation of organisational structures that allow cartel coordination. Recent evidence shows that around two thirds of South African firms sanctioned for anticompetitive behaviour participated in multiple cartels and, a third of the collusive agreements were found to have been facilitated by trade associations (World Bank, 2016). Moreover, the interaction between these few players and policy makers lack transparency, which allows for further entrenchment of private interests in state legislation. Clarifying roles and responsibilities and strengthening cooperation between the Competition Commission and other regulators, namely in the energy, transport and telecommunications sectors, who oversee pricing, entry and exit, would help deterring anticompetitive behaviour. The Competition Act has recently been amended, enabling the Competition Commission to engage in Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with regulatory authorities, providing guidance on their interaction in areas of concurrent jurisdiction. Competition policy and economic regulation could be articulated even further. In the United Kingdom, for example, a number of measures were introduced to enhance the role of competition law in regulated sectors (Box 3.5).

With the passing of the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 in the United Kingdom, sector regulators have been required to use their sector regulatory powers only after considering whether it would be more appropriate to use their powers under the competition law prohibitions. This is called “the primacy obligation”. In addition, sector regulators can carry out market studies and refer markets to the Competition Authority for a detailed investigation.

Source: OECD (2021g), “Competition Enforcement and Regulatory Alternatives – Note by the United Kingdom”, Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, Competition Committee, June 2021.

Public sector direct control over enterprises is still hefty. South Africa compares unfavourably in most indicators when it comes to distortions induced by state involvement, even compared to emerging market peers (Figure 3.14, Panel A). Public ownership often creates incentives to distort regulation in favour of state-backed incumbents. In service sectors, such as commercial banking, SOEs are even favoured by special rules. Adding to the issue, most public firms are underperforming, which has detrimental effects on aggregate productivity. Underperforming SOEs hold back labour and capital resources that could be reallocated to more productive firms. An effective governance framework for SOEs should be developed, as recommended in previous surveys, setting clear company-specific objectives. At the same time, SOEs’ boards should be professionalised to improve transparency in their management (OECD, 2020, 2015; chapter 1). A Presidential State-Owned Enterprises Council has recently been established, whose mandate includes strengthening the governance framework for SOEs, including the introduction of an overarching Act governing SOEs and determining an appropriate shareholder ownership model. Such developments are welcome, and efforts should continue. Finally, the privatisation of SOEs should accelerate, which would also open new opportunities for private investment.

The competition balance also tilts against foreign firms, which are subject to domestic content rules on labour utilisation, receive secondary priority when competing with local suppliers for public procurement contracts, and may be submitted to investment screening. Adjusting regulations to produce the right incentives presents vast potential to raise living standards (Sutherland and Hoeller, 2013). The recent success in reforming the insurance services sector may offer insights on redesigning services regulation (OECD, 2020a).

Regulatory barriers to competition in network industries are particularly high in comparison with OECD countries and emerging economies (Figure 3.14, Panel B). Low competition in network sectors dampens investment in high-quality infrastructure and lowers the quality of network services, with negative consequences for productivity growth, as discussed before. Easing access to the competitive segments of network industries would minimise the regulatory burden.

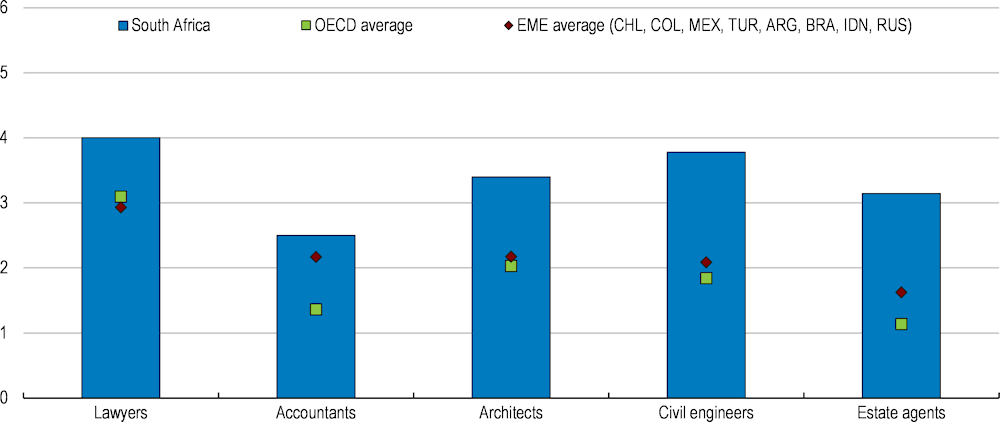

Trade in the region is not diversified enough, limiting opportunities for South African firms. Trade within the Southern African Development Community (SADC) area has been falling since 2016 and regional integration declined (Figure 3.15, Panel A). Like South Africa, exports of other SADC countries are driven by the global demand for commodities, whose prices have a strong impact on nominal exports. Few countries have developed sophisticated manufacturing products, which lowers the potential benefits from complementarities (Figure 3.15, Panel B; Fall et al., 2014).

Policies to strengthen integration and boost regional trade include reducing non-tariff barriers and developing intra-regional infrastructure (Fall and Gasealahwe, 2017). As of April 2021, 36 countries in Africa had ratified the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement and 54 countries out of 55 in Africa have signed the agreement. The first shipment of goods under AfCFTA took place in early January 2021, and most signatories have submitted their proposed rules of origin. South Africa is well placed to benefit from AfCFTA with the strongest manufacturing base in the continent, highly capitalised firms and banks, and good connections across the continent. South Africa should accelerate the implementation of the provisions of the agreement to reap the benefits associated with improvements in transport infrastructure, reduction of red tape for cross-border dealings, and funding of trade. As discussed in previous surveys, access to high-quality infrastructure needs to improve, as well as the access to export credit and credit insurance.

Note: Nominal exports of SADC countries by partner and share of intra-regional exports for Panel A.

Source: IMF, DOTS database and Comtrade, 2018.

Custom policies could still be improved, by training customs agents, limiting electric shutdowns, opening offices around the clock, and upgrading information systems, which are not always compatible or interlinked. The introduction of a unique computerised control point between borders of SADC countries could reduce red tape and corruption associated with cross-border trade operations.

Green growth is an opportunity to develop local supply chains and diversify exports. Minerals and metals used for solar panels, wind turbines, batteries for electric vehicles are produced in the region. South Africa already benefits from a well-developed car industry and high capacities in manufacturing. Green growth represents an opportunity to develop new business and to close gaps in the supply chain, but also to respond to the growing regional demand in renewable energy and electrification of transport. The large potential for wind and solar energy of the region could produce one of the cheapest electricity globally, supporting a greener economy.

Productivity largely depends on workers having adequate skills and knowledge. Innovation also depends on people who have the knowledge and skills to generate new ideas and technologies and bring them to the market and their workplace. To that end, access to high-quality basic and higher education is crucial. As the work environment constantly evolves and a large share of the workforce remains low-skilled, continuous education and training opportunities that are well aligned with labour market needs would considerably improve human capital. In South Africa, educational outcomes remain poor, and the lifelong learning system is still under-developed, requiring additional efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of the educational system. Finally, more effective health care would also bring substantial benefits in terms of welfare, employment and productivity, as healthy workers are more productive and remain active for longer.

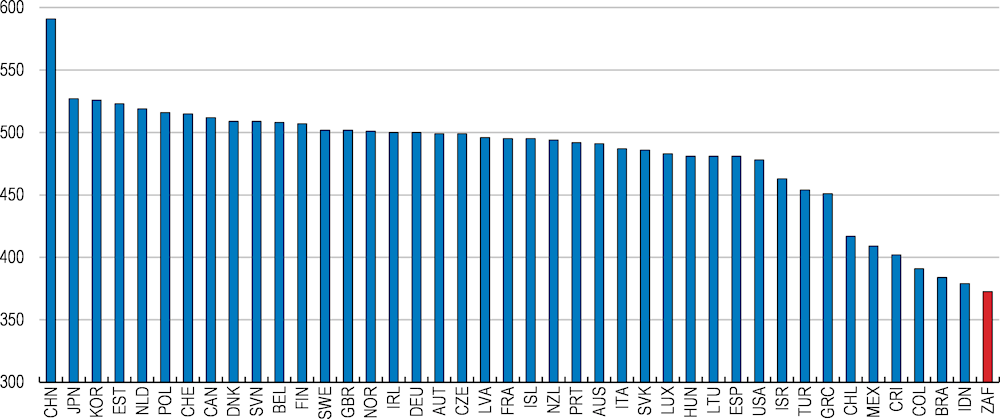

Educational outcomes in South Africa are poor. The latest TIMSS survey, in 2019, shows that teenagers’ math and science performance remain well below the OECD average and below emerging countries (Figure 3.16). The impact of education quality on economic growth is large. When average test scores in math and science, as measured by TIMSS, increase by 100 points, the long-term economic growth rate increases, on average, by 2.6 points (Hanushek and Woesmann, 2007). Skills acquired through basic education, in particular, are the fundamentals of workers’ productivity. Calculations using Hanushek and Woesmann estimates show that the current gap in education quality with the OECD average is costing South Africa about 3.3 percentage points of economic growth per year, a staggering number.

PISA math score at 15/grade 8, OECD and emerging countries

Note: Math performance is measured by PISA 2018 as average math scores. South Africa did not participate in PISA but the score has been computed from rescaling the average TIMSS 2019 math scores at grade 8. Rescaling was done by regressing average PISA 2018 math scores on TIMSS 2019 math scores at grade 8 for all countries which participated to both assessments. The correlation of both measures is very high at 0.91.

Source: OECD calculations from PISA 2018 and TIMSS 2019.

Although the performance remains low, significant progress has been achieved in the last decades. Education performance, as measured by TIMSS scores, has been improving markedly since South Africa’s first participation in the assessment in 1995. Average math scores have increased by more than one hundred points between 2003 and 2019, which represents a huge improvement, corresponding to what a student can learn in about 3.5 years of schooling. Improvement in basic education quality can be directly related to the fact that parents of today’s pupils have benefitted from longer schooling and improved livelihoods. Secondary enrolment also improved after the apartheid: about 43% of Black South Africans born in the early 1990s completed secondary education, compared to 37% fifteen years earlier (van der Berg et al., 2019). This progress is likely to boost potential growth in the decade to come, as these new skilled workers will enter the labour market.

Education quality is uneven across the country. Test performance is higher in more affluent areas. In fact, student’s performance is still largely influenced by parental human capital and households’ living conditions. Education inequalities have fallen somehow since 1995, but progress has slowed down more recently. The provision of textbooks is likely to improve students’ performance, especially among those whose parental education is limited and in cases where other school conditions, such as the state of the infrastructure or the quality of teaching, are suboptimal. However, 5% of learners are still lacking textbooks, and this proportion reaches 10% in the KwaZulu-Natal province, while it is only 1.5% in Western Cape, perpetuating inequalities across the country.

The education system has adjusted in several aspects to reduce the effects of poverty on learning. Access to the nutrition programme in public schools has been extended from 63% to 75% from 2009 to 2019 (Statistics South Africa, 2019). In addition, the cost of schooling was significantly reduced, as the share of students benefiting from free education went from 0.4% in 2002 to 66% in 2019. Reducing the detrimental effects of poverty on learning is likely to improve overall education quality and to decrease inequalities. Continuing to expand nutrition programmes and cutting school fees would further strengthen education quality. A third of families still pay tuition fees, which is likely to sustain school segregation and inequalities in learning conditions. It also deters participation, as high fees still remain the main issue pointed by families whose children are not enrolled.

Massive repetitions remain extremely costly for the public educational system. Repetitions absorb between 8 and 12% of public education spending (van der Berg et al., 2019). As about 10% of students repeat each grade, about two third of students end up being delayed by the age of 18. Repetition has no positive effect on school academic performance, decreases school participation and lowers self-esteem (Ikeda and Garcia, 2014). Therefore, massive repetitions tend to result in lower educational performance, while consuming public resources, which could be used more efficiently. In addition, repetition is highly skewed against the poorest segments of the population, increasing early dropout and reducing the likelihood of graduation for the most vulnerable (Van der Berg et al., 2019).

Reducing the number of repetitions allowed would free up useful resources. Repetition rates decreased slightly since 2013, going from 11.8 to 9.3% in 2019 (van der Berg et al., 2019). More could be done by considering restricting repetitions to the strict minimum, to students who missed school for a prolonged period of time, for example. As repetition is also the result of established social norms, it is usually difficult to reduce it beyond a certain point without resorting to an official ban. Limiting repetitions to a minimum would tamper the social and racial biases and prejudices which are fuelling repetitions. It would also free up large human and capital resources that could be redirected to improve basic education quality.

Financial resources are needed to improve equitable access to Early Childhood Development (ECD), which strengthen children’s learning capacity in the long run. The coverage of early childhood development had been increasing slowly from 32.6% in 2010 to 36.8% in 2019 but fell back to 24% in 2020 in the context of the pandemic (General Household Surveys, Stats SA). Moreover, spatial disparities are large with coverage being three times larger in the Free State (38%) than in Northern Cape (12%). Basic infrastructure is an issue with some schools lacking sanitation or electricity and suffering from overcrowded classrooms (OECD, 2019b). The share of education spending on physical capital is only slightly above 4% (UNICEF (2019), while the average OECD country spends about 9% (OECD, 2020g). The lack of learning materials, textbooks, libraries, and access to ICT have also been flagged as impediments to learning (OECD, 2019b; Murtin, 2013). In fact, some families can’t afford textbooks.

Teaching practices are not the most pressing issue. Therefore, additional resources should be devoted to improving the infrastructure and studying conditions. South Africa participated in 2018 in the OECD survey of teaching and learning survey (TALIS). Teachers’ and principals’ answers underline that South Africa scores above the OECD average in terms of practices, training and skills of the teaching force (OECD 2019b). Teachers tend to be collaborative, innovative in their approach. They use more frequently efficient teaching strategies, and their training includes classroom practices and addresses socioeconomic and ability diversities within classrooms. Assessment practices are also above OECD standards.

The disciplinary climate is poor and could be improved. About 25% of students’ report that most lessons are disturbed (Mulis et al., 2020). Disciplinary climate is usually one of the school factors, which have the highest impact on school performance (Cahu and Quota 2019). In South Africa, students benefiting from orderly lessons perform about one year and a half ahead of those suffering from the most disorderly lessons. The disciplinary climate can be improved dramatically through rapid and inexpensive interventions, whose economic returns can be as high as 30% (Horner and al., 2009). The implementation of positive discipline is at the heart of tackling violence and disruptions by students.

Corporal punishment is unlawful, and its use has declined, but its incidence remains an issue. The use of corporal punishment decreased substantially, falling from 17% to 7% between 2009 and 2019 (Cuartas et al., 2020). Corporal punishment has been proven harmful to children's cognitive abilities, as well as counterproductive in pacifying classrooms by inducing depression, low self-esteem, and disruptive behaviours in students (Cuartas et al., 2020; Gershof, 2017). A public campaign to end these practices, by raising awareness of children and families, as well as training teachers is likely to yield very large benefits. South Africa could experiment the North American approach of Positive Intervention and Behavioural Support (PIBS), which has been proved to improve significantly both disciplinary climate and academic achievement in more than 22,000 schools (Box 3.6).

Positive Behavioural Interventions & Supports (PBIS) is a framework to enhance school discipline, social skills and academic performance. It has been used successfully for more than 20 years in 26,000 schools in North America and experimented in other countries such as Tunisia. PBIS results include reducing undesired behaviours in 90% of schools, reducing class classroom removal and school suspension by 34% and increasing math performance by 20% of a standard deviation. Implementing the PBIS approach has a low cost, with rapid results after a few months. Benefit-cost ratios are typically above 100, which makes PBIS one of the most efficient education intervention possible. PBIS usually starts with a few days’ training of teachers and school staff, accompanied by methodological tools, and followed by two years of implementation.

Source: Bourhaba O. (2015), “Literature review of academic evidence on PBIS”, European Investment Bank.

The economy is constrained by the scarcity of skilled workers (Depken et al., 2019). The supply of university and post-secondary graduates remain limited. In 2019, only 5.4% of people aged between 18 and 29 were enrolled in higher education, compared to 20.5% in the OECD (OECD, 2022a). In addition, about 26% of students were aged 25 to 29 in South Africa, compared to 40% in the OECD. The share of a cohort having studied beyond secondary education was only 15.4%, while it was 39% in OECD countries. The lack of qualification is hampering the labour market integration of youth, as 52% of them were unemployed in 2020, compared to only 10% in the OECD. Youth also make up almost 60% of all unemployed people in South Africa, underlining the rigidities of the labour market, which disproportionally protects the insiders (OECD, 2022b).

Shortcomings in access and quality of basic education are limiting the pool of potential students and therefore skilled workers. For OECD countries, on average, about 85% of a generation reaches secondary school, 72% in Brazil, compared to only 55% in South Africa. Of those who reach secondary school, only about 48% succeed in graduating. Improving access to quality basic education, as discussed above, would therefore contribute to improve the supply of university and post-secondary graduates.

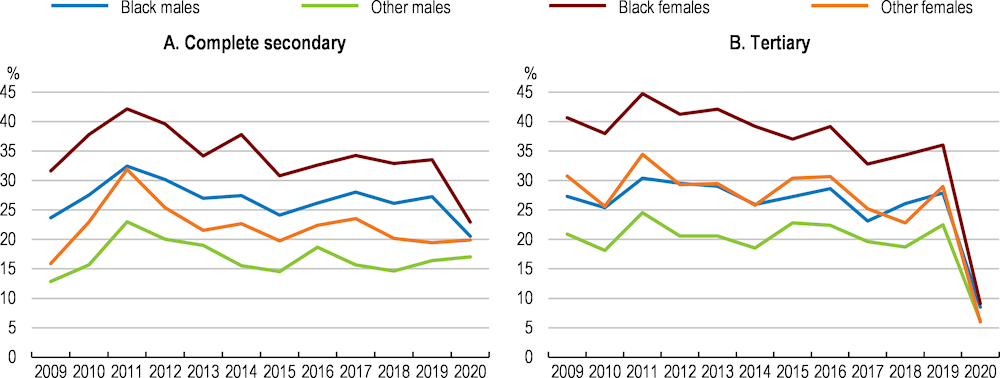

The country suffers from very large spatial and racial inequalities in education attainment. Education returns have peaked in 2011 and have stabilised at a slightly lower level in the last decade, in an environment of low growth (Figure 3.17). In 2019, an individual who completed secondary school had on average 30% more chances to be employed than someone who did not, and the employment premium was around 25% at tertiary education level. Returns to education are different for males and females and differ largely by ethnic origin. Returns to education are much higher for women, all other things being equal. Most of the employment premium of graduate women comes for increased participation in the labour market. Education returns are also much higher for black citizens compared to coloured or white ones. This evidence suggests that the current shortage in university seats is hurting disproportionally women and black citizens, who benefit the most from tertiary education.

Premium in probability

Note: Panel A indicates the increase in employment probability for someone who completed secondary education compared to someone who did not. Panel B indicates the increase in employment probability for someone with some tertiary education compared to someone who stopped after completing secondary. Probabilities are estimated using a probit model accounting for gender, type of population, age, age squared, education level, and vocational education.

Source: OECD calculations from QLFS, second quarter: 2009-2020.

The country has a limited number of post-secondary institutions, and they tend to be spatially concentrated in a few cities. Overall, the number of subsidised seats in public universities, which welcome 85% of students, is insufficient to cater for the demand of families and employers. University infrastructure was not tailored to host massive cohorts. Although the establishment of two new universities has recently been announced, current cuts in infrastructure spending to balance universities’ budget make these openings unlikely in the years to come. Formula-based financing for universities, as explained below, would incentivise universities to develop physical infrastructure and enrol more students.

Tertiary spending per student is high in international comparison. Student spending at the tertiary level was about 0.68% of GDP per capita in 2017, ranking fourth among OECD countries (Figure 3.18). Unit costs in universities are almost 2.5 times larger than the OECD average, while none of its universities appears in the top 150 of the Shanghai University rankings. If training would be as efficient as in the OECD, South Africa’s tertiary system could enrol about 1.5 million additional students with the same amount of resources. Therefore, if used efficiently, current resources dedicated to the university system might be enough to bridge the gap between demand and supply of higher education.

The university financing system contributes to inflate student spending. Universities use students’ fees for their financing, which creates incentives to increase tuition fees instead of cutting costs. In addition, accepted students whose households earn less than ZAR 350 000 qualify for a subsidised seat, regardless of the amount of the tuition fees. The amount of the public subsidy is therefore proportional to tuition fees, as set by each university, creating even more incentives to set high tuitions. Another consequence of such a system is that the number of students coming from secondary schools who qualify for this funding is much higher than the number of available seats the Ministry can afford. This funding mechanism is therefore also cutting the capacity of universities. The epidemic has put pressure on the budget of universities, as many more students are poor enough to qualify for a subsidised seat because of the economic crisis. While being the fastest growing budget within government spending, at current costs, government spending in tertiary education cannot be sufficient to provide the skills the labour market needs.

Tuition fee indexation since 2018 has not been sufficient so far to push costs down and increase efficiency. Following a student’s protest movement against the increase of tuition fees, which started in 2015, universities were not allowed to increase their fees in 2016 and 2017. The Government assumed that cost and limited the growth in the number of seats, adding more constraints to the supply of higher education. Fees were allowed to increase for a maximum of 8% in 2018 and have since been indexed to inflation. As inflation increases more slowly than teachers’ wages and actual costs, fees indexation is eroding universities income. Such a mechanism is too slow to effectively push institutions to cut the cost of training in the medium-run and other interventions are needed.

South Africa should consider moving to formula-based financing, where universities compete for public funding based on a previously determined formula. Such formula usually takes into account the number of students enrolled, the socioeconomic conditions of students and educational outcomes, such as graduation rates or estimated training relevance based on alumni employment surveys. This would not prevent universities to levy fees on the most privileged. By offering lower subsidies per student, the State would create a strong incentive to increase the number of seats offered by universities, while helping them rationalise teaching costs. This system has proved quite effective in European universities (Box 3.7).

Tertiary student spending as a share of per capita GDP in 2017

The use of conditional commercial loans could also be experimented to increase student enrolment. Given the high private returns of tertiary education and the current shortage of public funds, regulated conditional commercial loans provided by private banks to students and guaranteed by the State could be introduced. The repayment of such loans would be conditional to the students’ future income being above a certain threshold. The system would be monitored by the South African Revenue Service, which can track future income.

Distance learning has not helped lowering training costs. Online teaching has been massively used in an attempt to reduce the cost of university training. University of South Africa (UNISA), the institution responsible for distance learning already covers a third of all students. However, the lack of student support induces massive repetitions and dropouts, actually increasing the cost of training. To improve the effectiveness of distance learning, students enrolled online should be provided with adequate digital tools, learning resources and support to remain highly motivated. Teachers should also be trained to use technology and to adapt their teaching methods to distance learning (OECD, 2020g, 2020h, 2020i).

Europe as a continent boasts the higher number of universities in the top of international rankings. Yet about three quarters of their income comes from public funds while tuition fees typically represent less than 10% of universities income in Europe (OECD, 2020f). Public funding is most of the time based on a formula linked to inputs, typically the number of students enrolled. However, output-based criteria such as graduation rates or equity indicators have been increasingly introduced into funding formula to improve performance. About two thirds of European countries also use performance contracts signed between the funding authorities and universities to ensure that strategic objectives are met.

In the U.S., at least 30 states are using some form of performance-based funding for colleges and universities. Such programmes vary in the percentage of the total funding allocated toward performance-based measures, the types of behaviours that are incentivised and the funding formula used to measure performance. In Ohio, for example, the funding formula rewards completion of “at-risk” students, as defined by economic, demographic, and previous education data collected by the state. In Pennsylvania, colleges and universities are measured against ten performance indicators, half of which are unique to the institution to better incorporate specific institutional goals.

Source: Gherghina and Cretan (2012); Miao (2012).

Opportunities for adults to participate in training after leaving initial education are scarce. Community Education and Training (CET) has been significantly developed since 2013 to facilitate lifelong learning, second chance education and training, up-skilling and re-skilling, with the goal of improving access to employment for low skilled youth and adults. The CET system absorbed the existing 3 276 public adult learning centres, leading to the creation of nine multi-campus institutions, one in each province, offering vocational, skill-development and non-formal programmes. However, limited public funding has been channelled to this system. Consequently, the quality of training provided is low and dropout rates are high (OECD, 2019a).

Stronger coordination and cooperation across multiple stakeholders could substantially improve the quality of the Community Education and Training system without necessarily raising public spending. Several actors are funding lifelong training activities for unemployed and job seekers, using the unemployment insurance fund, the National Skills Fund, levies on employers, or yet, provincial and municipal government funds (OECD, 2019a). These training opportunities should be better coordinated to avoid the duplication of efforts and inefficiencies. Information about this training offer should be more widespread and easily accessible.

The Community Education and Training system should be responsive to the needs of employers and provide relevant skills for the labour market. Partnerships with employers’ associations and Sector Education and Training Authorities, for example, could help to adapt the training offer and the content of the training courses. Internship opportunities could come out of these partnerships, improving students’ exposure to the work environment, and working practices. Firm-provided training can have a significantly positive impact on sales, value-added, exports and productivity (Martins, 2021). Pathways from Community Education and Training to technical colleges could also be developed to retrain younger unemployed workers and improve their employment opportunities (chapter 1; OECD, 2019a). Continuous upskilling and reskilling are crucial to increase worker mobility across occupations, firms and sectors, leading to a more efficient allocation of labour across productive jobs.

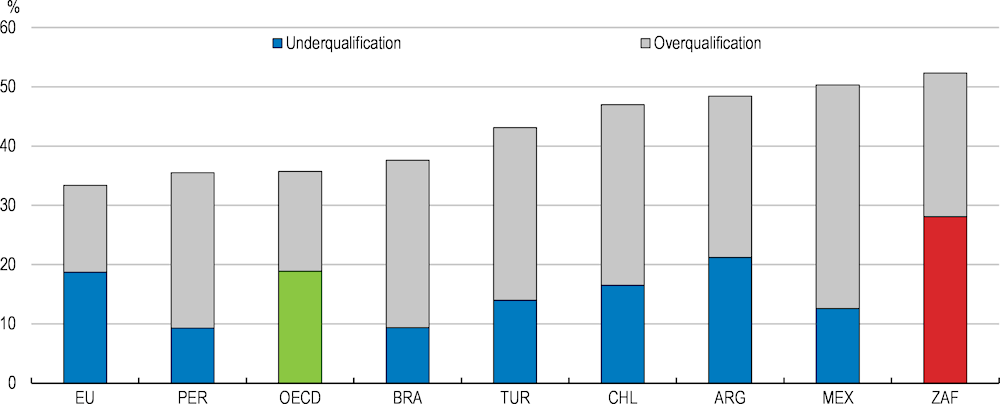

Low educational attainment and limited lifelong learning opportunities are associated with high skills imbalances (OECD, 2019a). Qualification mismatch is relatively widespread in South Africa compared to OECD countries with, in particular, a high share of workers who are underqualified for their job (Figure 3.19). According to the results of the 2015 Manpower Global Talent Shortage Survey (Manpower Group, 2015), 31% of South African employers report having difficulties filling jobs, especially for skilled jobs in trade, engineering, and management (OECD, 2017d). Skill mismatch is strongly and negatively correlated with labour productivity (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2015, 2017).

Percentage of total number of workers aged 15 to 64, 2016

Note: Qualification mismatch arises when workers have an educational attainment that is higher or lower than that required by their job. If their education level is higher than that required by their job, workers are classified as over-qualified; if the opposite is true, they are classified as underqualified.

Source: OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: The OECD Skills for Jobs Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The government has made substantial efforts to reduce skill mismatch by setting up a labour market intelligence unit to analyse skills needs and introducing a career guidance system. However, the information collected is not always representative as not all firms submit the required information. In addition, not all employers analyse and assess their skills needs regularly, meaning that they are not necessarily able to anticipate training needs (OECD, 2017d). Firms should be encouraged to undertake skill need assessments. The government could also consider the possibility of offering training to employers who lack the capacity to implement skill assessment and anticipation methods.

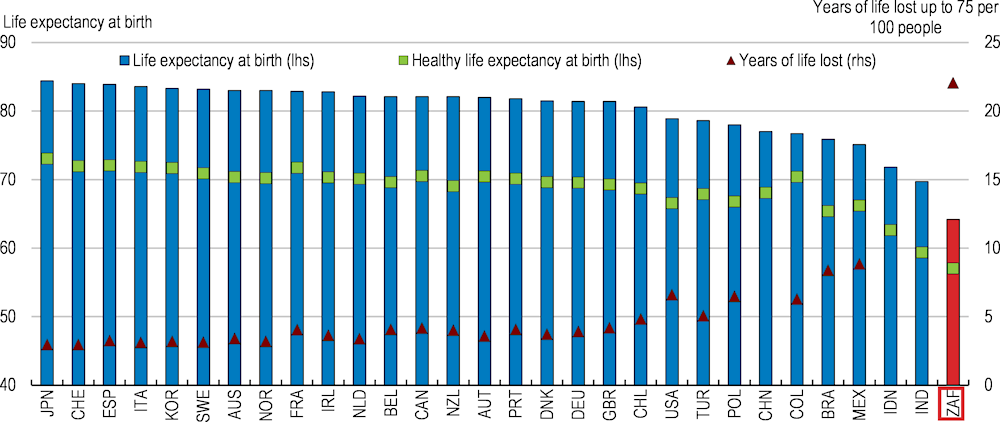

The health status of the South African population is well below that of OECD countries and other large emerging countries. Life expectancy at birth is five years behind India’s, a country where living standards are twice as low, and about 15 years behind the OECD average (Figure 3.20). A large part of this gap can be related to preventable premature death, especially AIDS. In fact, accounting for disabilities and the quality of life does not change this picture, as the Healthy Life Expectancy was about 56 years, more than 14 years behind the OECD average and 4 years behind India (WHO statistics, 2019). The number of potential years of life lost for 100 individuals aged 0-75 years is about 22 years, more than four times as much as in OECD countries (OECD, 2022c).