Urban Sila

OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2024

3. Tackling labour and skills shortages

Abstract

The Swiss labour market is strong with high employment rates, high job security, and attractive jobs. However, labour and skills shortages have risen and are likely to become a structural feature of the labour market due to the ageing population. To counter labour and skills shortages, labour participation could be boosted further, by lengthening working lives and by bringing more mothers to work full time. Maintaining attractiveness for skilled foreign workers can also counter declines in the domestic labour force.

Labour shortages are set to become a structural concern

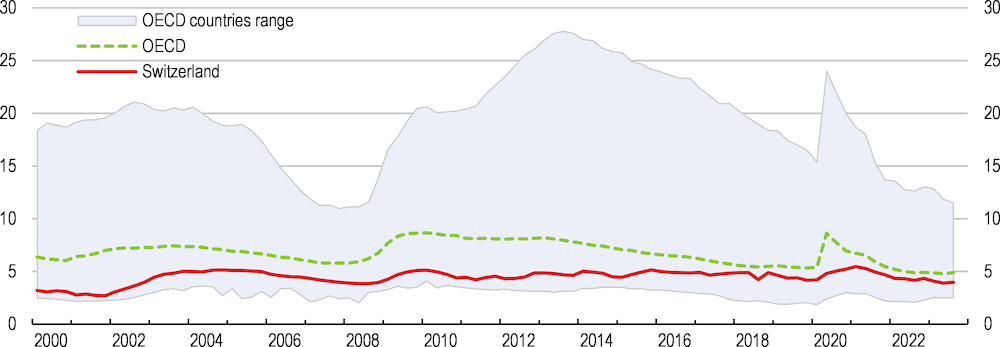

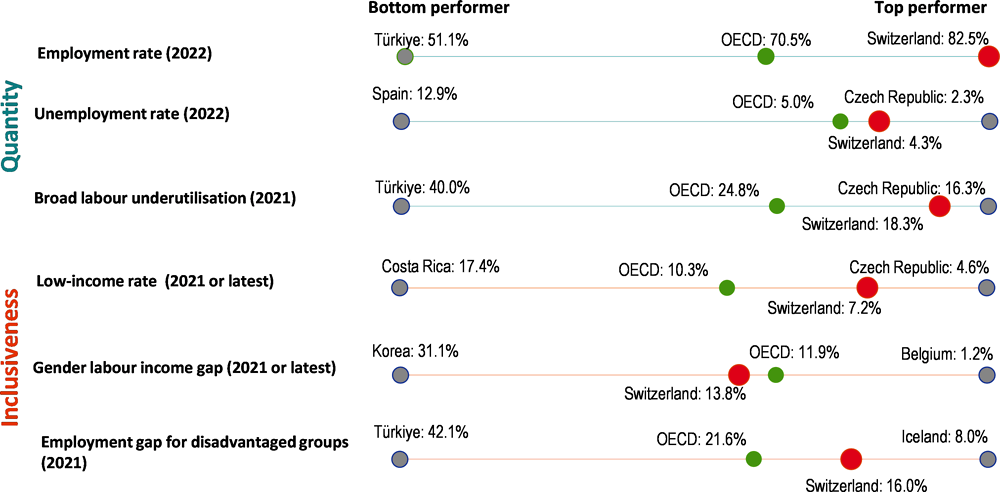

The Swiss labour market is very strong in most respects (Figure 3.1). The employment rate is high and the unemployment rate has remained comparatively low even in times of crisis (Figure 3.2). Correspondingly, job security is high. The Swiss labour market offers well-paid jobs, and there is a relatively high level of inclusion, with low poverty rate among the employed. However, the gender labour income gap remains persistently high, significantly above the OECD average.

Figure 3.1. The Swiss labour market is very strong in most respects

Dashboard of the labour market according to the OECD Jobs Strategy

Note: Employment rate: share of working-age population (20 to 64) in employment (%). Unemployment rate: share of persons in the labour force (15+) in unemployment (%). Broad labour underutilisation: share of inactive, unemployed or involuntary part-timers (15 to 64) in the population (%), excluding youth (15 to 29) in education and not in employment. Low-income rate: share of working-age persons living with less than 50% of median equivalised household disposable income. Gender labour income gap: difference between median annual earnings of men and women divided by median earnings of men (%). Employment gap for disadvantaged groups: average employment gap between prime-age male workers and five disadvantaged groups (women with children, young people not in education or full-time training, workers aged between 55 and 64, foreign-born people aged 15 to 64 years, people below upper secondary education aged 25 to 64 years.), as a percentage of the employment rate for prime-age male workers. OECD is a weighted average for employment and unemployment indicators and an unweighted average for the remaining indicators.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Economic Outlook database, OECD Family database, OECD Employment database, OECD Income and Distribution database, OECD International Migration database.

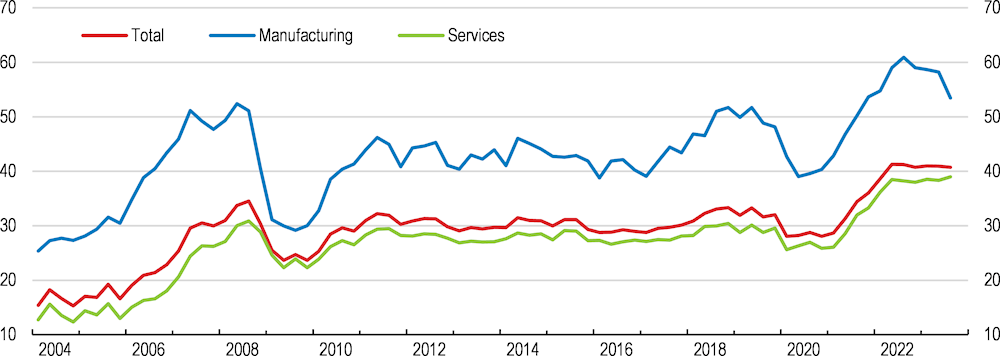

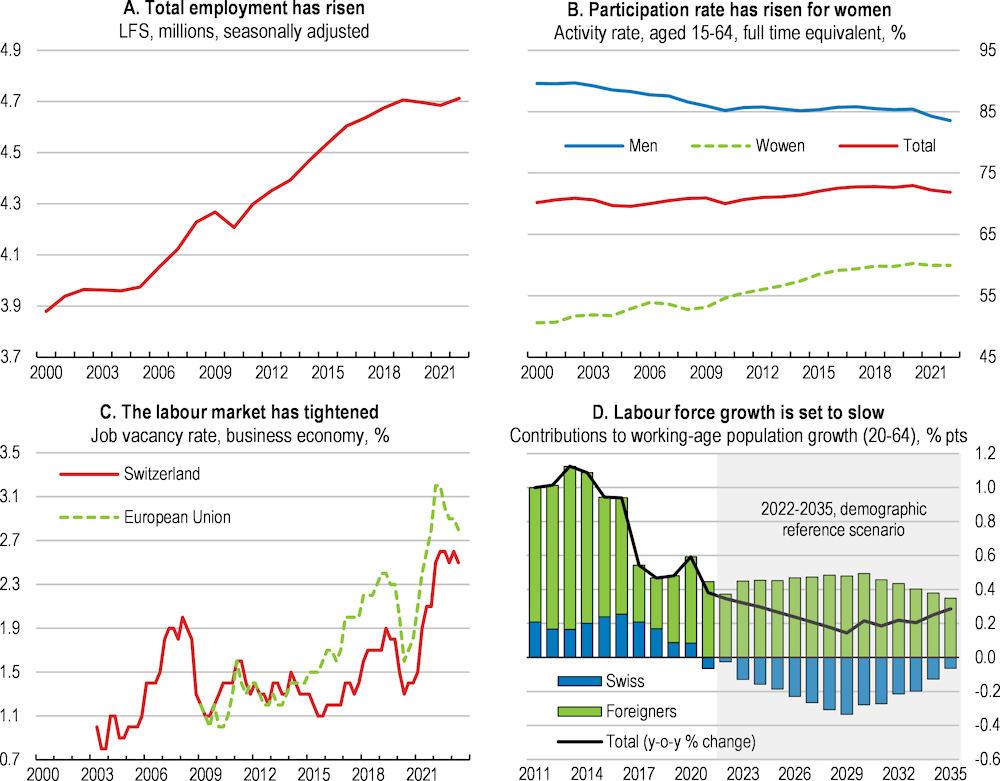

Labour and skills shortages have risen and are likely to become a structural feature of the labour market. Since the pandemic, employers in all sectors have increasingly reported difficulties in recruiting qualified workers and identified staff shortages as a risk to growth (Figure 3.3). Total employment has risen, underpinned by rising labour force participation of women, and resumed high net immigration. Yet, despite this rapid growth, the labour market has tightened (Figure 3.4). Furthermore, population ageing and a recent trend of declining working hours of prime-aged men suggest that labour force growth will slow down further, making labour shortages a structural concern (Figure 3.4). Companies increasingly view labour shortages as more than a short-term challenge and are trying to make themselves more attractive as employers. They are also stepping up investment in automation and IT infrastructure (SNB, 2023).

Figure 3.2. The unemployment rate has remained comparatively low even in times of crisis

Unemployment rate, national definitions, % of the labour force

Figure 3.3. Employers increasingly report difficulties in recruiting qualified workers

Qualified personnel found with difficulty or not found at all, share of companies actively recruiting, in %

To counter labour and skills shortages, labour participation could be boosted further, by lengthening working lives and by bringing more mothers to work full time. Lengthening working lives will raise incomes in old age and counter pressures in the pension system. Encouraging mothers work more hours will help reduce the sizable gender income gap. Moreover, maintaining attractiveness for skilled foreign labour can counter declines in the domestic labour force.

Figure 3.4. Labour shortages are likely to become a structural feature of the labour market

Note: The job vacancy rate (JVR) is the number of job vacancies expresses as a percentage of the sum of the number of occupied posts and the number of job vacancies.

Source: OECD Short-term labour force statistics; FSO, Swiss Labour Force Survey (SLFS); Eurostat; FSO, Population scenarios.

Raising the activity rate of women

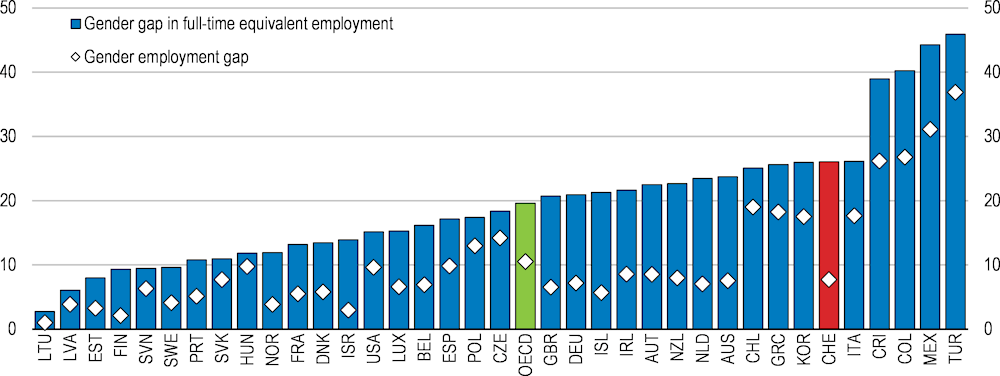

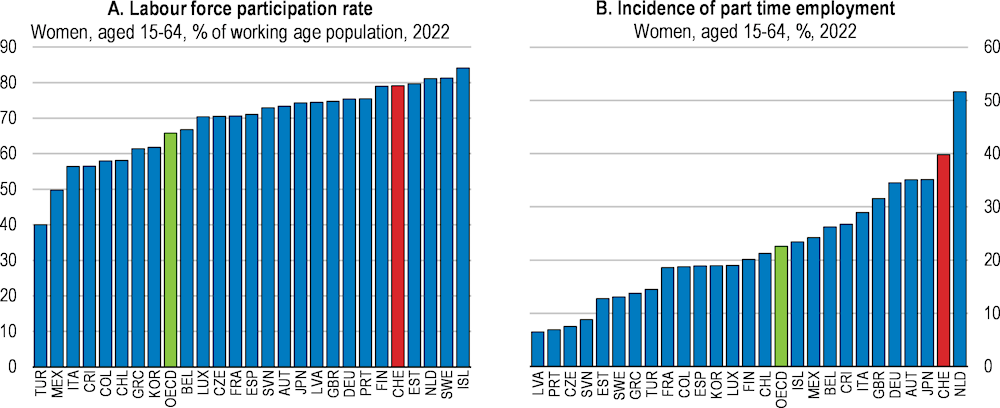

The labour market participation rate of women is high overall, but this masks one of the highest incidences of part-time work across the OECD (Figure 3.5). Consequently, the gender gap in full-time equivalent employment rates is very high (Figure 3.6). Part-time work is common for all women, but for mothers in particular. Eight out of ten mothers with a partner whose youngest child is under 12 years old work part time (FSO, 2023). Inequalities and the lower activity rate of women also have a long-term impact on women’s careers and pensions. On the one hand, the possibility of part-time work is conducive to the participation of women in the labour market who might otherwise stay inactive. On the other hand, part-time jobs offer less favourable employment conditions in terms of social security, access to continuing education and career progression. Moreover, women on average receive 50% lower benefits from the second pension pillar (occupational pensions) compared to men (Federal Council, 2021a). Higher activity rates of women would raise equity, support incomes and ease labour shortages.

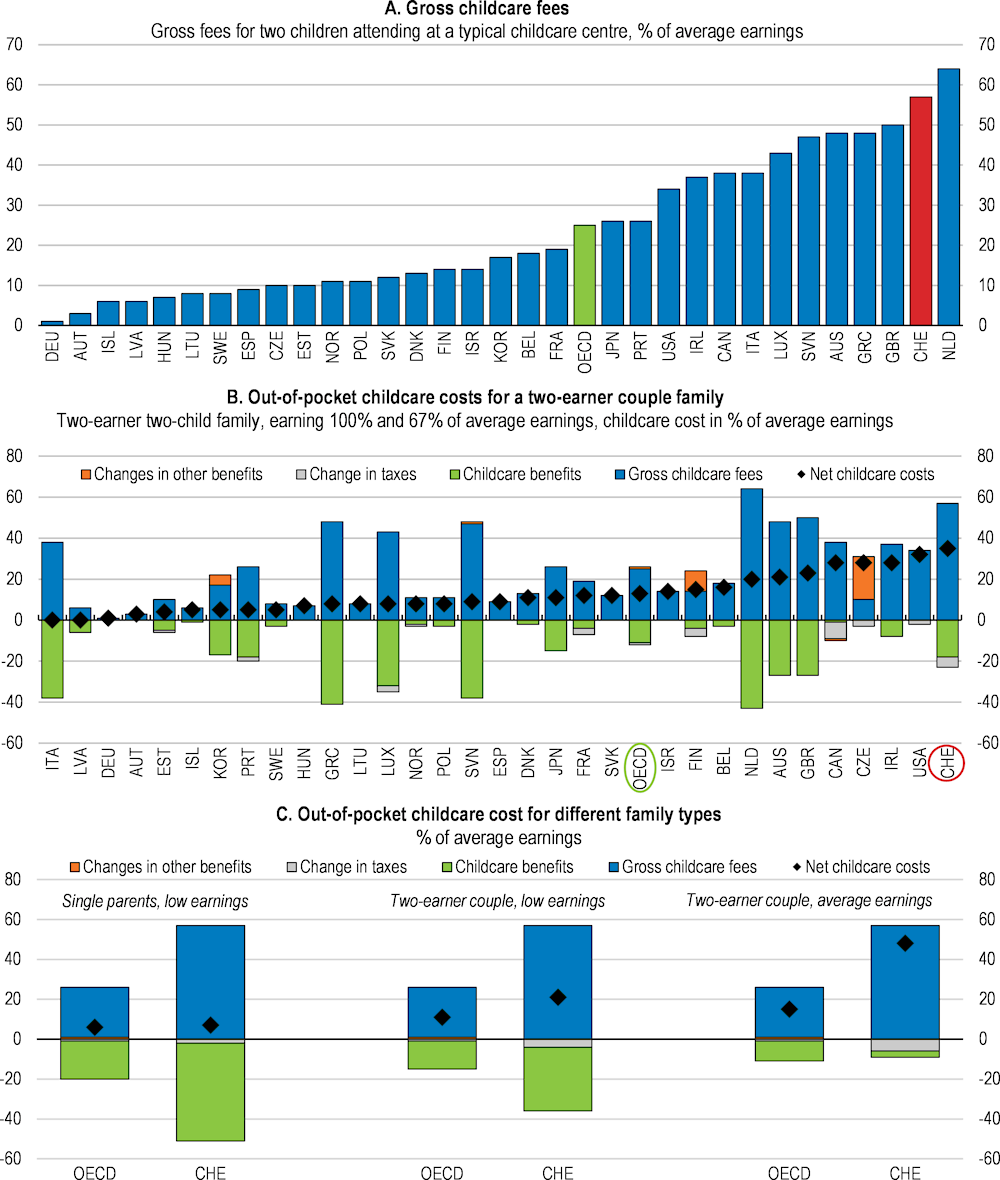

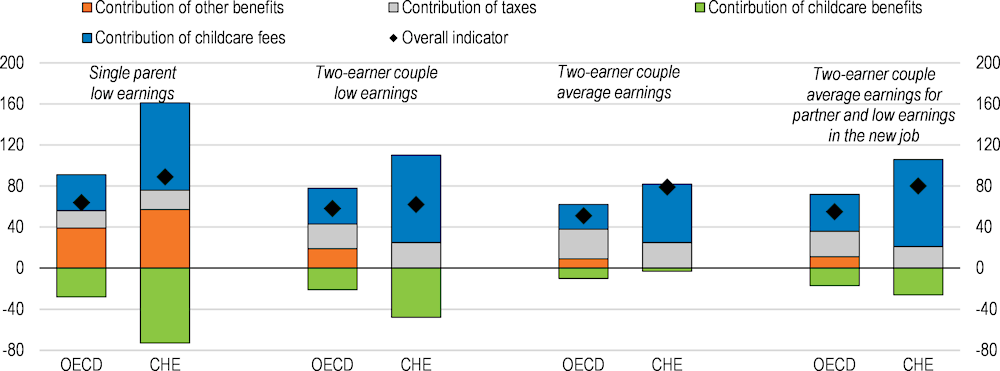

Incentives within the tax-benefit system and the high cost of childcare discourage mothers from working full time. The OECD Tax-Benefit model combines federal and the canton of Zürich tax-benefit policies to simulate the interplay of policies across types of families and labour market situations. According to the model, in Zürich, the gross childcare fees are the highest in the OECD. The out-of-pocket cost of childcare, after deducting the benefits designed to reduce gross childcare fees, is also very high for many families (Figure 3.7). For a couple with two young children earning the average wage, the net childcare cost represented 35% of average earnings, well above the OECD average of 13%. While greater financial help is available to those with lower earnings or single parents (Figure 3.7), for some, the effective taxation of going to work (considering the cost of childcare, taxes and withdrawal of certain benefits) creates a strong disincentive to enter work (Figure 3.8). For instance, for a family with two young children using childcare facilities where both parents earn average earnings, the cost for a second earner to move from unemployment to full-time employment (earning the average wage) represents 79% of the wage, versus 51% on average in OECD countries. Personal income taxes also play a role. In Switzerland, the tax is progressive and based on the household (either unmarried individuals or married couples) as a taxing unit, which tends to increase the marginal personal income tax of second earners, reducing incentives to work.

Figure 3.5. The high participation rate of women masks one of the highest incidences of part-time work

Note: Part-time employment is based on a common 30-usual-hour cut-off in the main job.

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics.

Figure 3.6. The gender gap in full-time equivalent employment is among the highest in the OECD

Gender difference (men minus women) in the employment rate and the full-time equivalent employment rate, 15-64 year olds, % pts, 2021

Figure 3.7. The cost of childcare is very high

For two children (age 2 and 3) in full-time care

Note: 'Full-time' care is defined as care for at least 40 hours per week. Net childcare costs are equal to gross fees less childcare benefits/rebates and tax reductions, plus any resulting changes in other taxes and benefits following the use of childcare. For panel B, data reflect the costs of full-time care in a typical childcare centre for a two-earner two-child couple family, where both parents are in full-time employment and the children are aged 2 and 3. Gross earnings for the two earners in the family are set equal to 100% of average earnings for the first earner, and 67% of average earnings for the second earner. For panel C, low earnings refer to 67% of average earnings. Data refer to 2022 or latest available year.

Source: OECD Tax and Benefit Model.

Figure 3.8. The cost of childcare, taxes and withdrawal of benefits create disincentives for employment

Participation Tax Rate (PTR) for parents claiming unemployment benefits and using childcare services, %, 2022

Note: The Participation Tax Rate (PTR) indicator measures the financial disincentives to participate in the labour market for a jobseeker claiming unemployment benefits. It calculates the proportion of earnings that are lost to either higher taxes, lower benefits and net childcare costs when a parent with young children takes up full-time employment and uses full-time centre-based childcare. Higher values mean higher financial disincentives. Low earnings refer to 67% of average earnings. Children are aged two and three. The unemployment duration is 36 months.

Source: OECD Tax and Benefit Model.

Various policies aim to reduce high childcare costs, but support measures are not well-targeted. Only 20% of children aged 0-2 years from lower-income households attend childcare compared to 60% from higher-income households (Figure 3.9). This indicates that households weigh the childcare cost against earning opportunities and policies have not succeeded in helping to overtake this barrier.

There are several ways of improving affordability of childcare. In Scandinavian countries such as Sweden or Denmark, government support for Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) is substantial and out-of-pocket expenses small. Comprehensive ECEC coverage aid labour market participation of parents - in particular women - across the income distribution yet involve large fiscal costs. In Sweden, parents have the right to enrol their children at preschool from the year the child turns one until the year it turns six (when mandatory school starts). Pre-schools are largely funded through municipal budgets, with parent’s paying small out-of-pocket fees that are income-dependent but are capped at a maximum of SEK 1 688 (roughly CHF 139) per month per child. The ECEC account for 14.1% of municipal budgets (Ekonomifakta. 2022).

In 2024, the federal personal income tax system allows for a tax deduction (amount deducted from taxable income) for childcare fees charged by a third-party of up to CHF 25 500 (more than double the amount in 2022) and a tax deduction of CHF 6 700 per child irrespective of declared childcare costs (along with a tax credit of CHF 259 per child), but, with more than 40% of Swiss families not paying federal income taxes, this provision has little impact on childcare affordability for low income households. Families also receive cash benefits (family allowances). Amounts vary across cantons but a nationwide legal minimum is set at CHF 200 per child per month. Cantons can complement these benefits by additional allowances or fee subsidies and there is a large heterogeneity of cantonal policies in this regard. The proportion of childcare costs covered by parents varies widely across cantons (OECD 2021a).

Providing fee reductions, childcare benefits or tax credits at the federal level rather than tax deductions would help increase childcare affordability without providing more generous support to better-off families. Targeting could be improved further by introducing income-tests on childcare benefits and fee reductions at the federal level (OECD 2020). These transfers would need to be carefully designed and decrease with income only gradually to avoid creating large changes in marginal effective tax rates at thresholds and causing work disincentives. With cantons responsible for the design of the personal income tax at the subnational level, adjustments are needed at both federal and cantonal levels to ensure coherence of the taxation system.

Reforming taxation to improve work incentives for second earners is another avenue to boost female full-time labour participation, as recommended in previous OECD Economic Surveys (OECD 2017, 2022a). Following a Parliament request, the Federal Council is currently preparing a reform to move to individual taxation both at the federal and the cantonal level. For example, Estonia switched from a household-based to an individual-based personal income tax system, and Luxembourg introduced the option for individual income taxation (OECD, 2023a). Reducing the second earner's marginal effective tax rate could also be achieved under the current, family-based, setting, for instance, by providing a larger tax deduction (or allowance) for the second earner.

Figure 3.9. There is a large gap in the use of childcare between low- and high-income households

Participation rates in early childhood education and care, 0- to 2-year-olds, by equivalised disposable income tercile, %, 2020 or latest available year

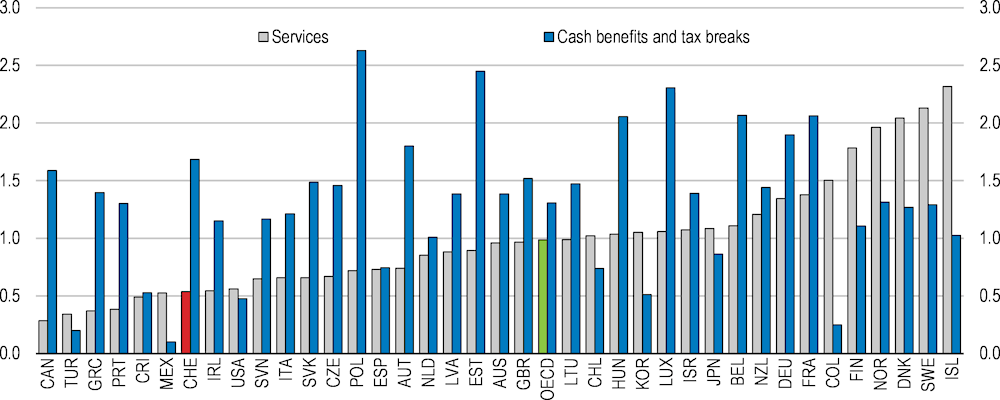

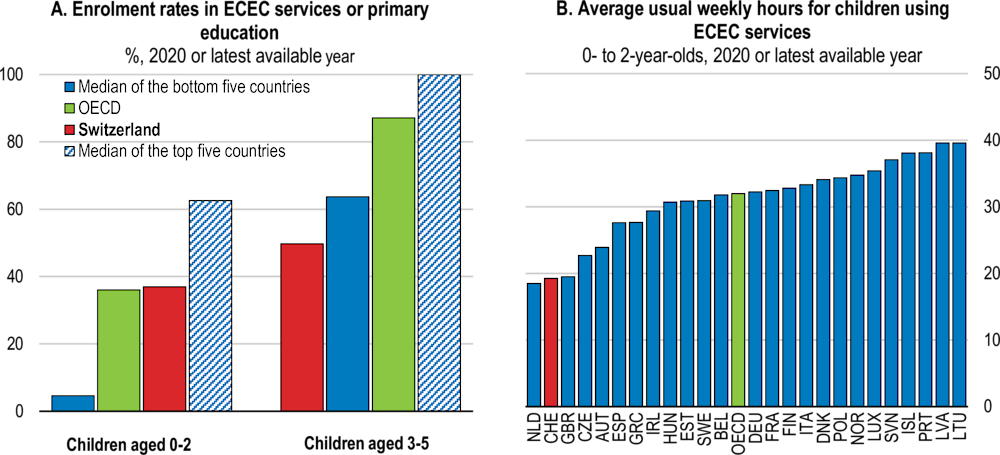

Increasing the supply of affordable childcare is essential and could be seen as a first step towards encouraging more mothers to work full time and strengthen their connection to the labour market. The relatively low use of childcare in Switzerland is linked to its elevated cost, high incidence of part-time work and limited supply of childcare facilities. The participation rate of 3-5 year old children in early childhood education and care (ECEC) is very low in Switzerland. Pre-primary education for children aged 4 to 6 is compulsory, and its provision is almost fully public. Whereas all children aged 4 to 6 are granted 15 hours of free access to ECEC per week and almost all 5-year-olds are enrolled in public pre-primary education (kindergartens), provision for children under 4 is more limited (OECD, 2021a). The participation rate of 0-2-year-old children is close to the OECD average, but the number of hours they spend in childcare is very low (Figure 3.10), 19 hours per week compared to an OECD average of 32 hours, mirroring the high prevalence of part-time work by mothers. Childcare is under the purview of cantons and municipalities, but privately established, run and financed childcare prevail for children under 4. Public spending on childcare services is low (Figure 3.11).

Increasing the supply of childcare remains a government priority as stipulated in the 2030 Gender Equality Strategy (Federal Council, 2021b). In 2003, the federal government set up a dedicated program to expand childcare provision that has been extended to end in 2024 and is estimated to have helped create about 72 000 new childcare places by end-2022 (OFAS, 2023). A parliamentary initiative in 2021 called for a larger role of the federal government, a more long-lasting financial support to parents and improvements in childcare services (CSEC-N, 2021). These efforts should continue.

Figure 3.10. The use of childcare is low

Note: For panel A, data for children aged 0-2 generally include children enrolled in early childhood education services (ISCED 2011 level 0) and other registered ECEC (early childhood education and care) services. Data for children 3-5 include children enrolled in early childhood education and care (ISCED 2011 level 0) and primary education (ISCED 2011 level 1).

Source: OECD Family Database, https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

It is also important to ensure quality of childcare. Provision of early childhood education and care is quite fragmented in Switzerland. Different types of providers are available (both centre-based and family-based) raising challenges with respect to ensuring consistency in quality. For centre-based and home-based childcare settings for children under four, regulations on professional development and working conditions are mostly lacking. High ECEC staff turnover is partly related to poor working conditions (OECD, 2021a). The government has developed a unified curriculum from birth to four years that helps set the basis for quality control but monitoring of its implementation is lacking (OECD 2021a). The authorities should ensure effective coordination and monitoring to safeguard quality across different providers, ensuring that children benefit from equal learning and development opportunities.

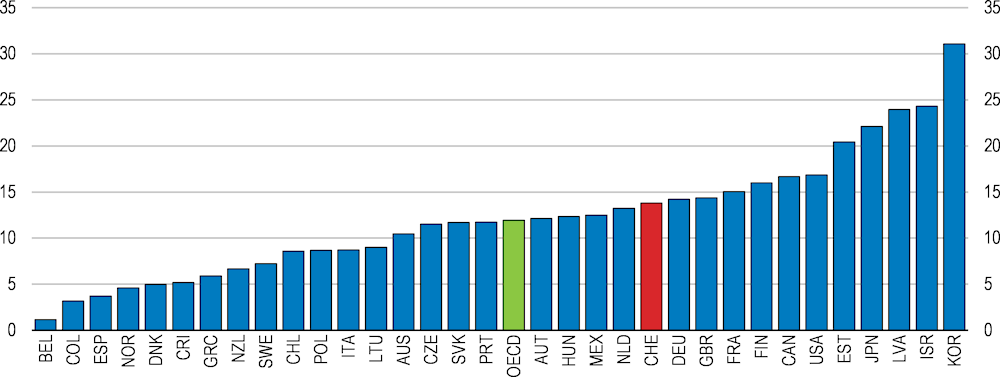

Figure 3.11. Public spending on childcare services is low

Public expenditure on family benefits by type of expenditure, % of GDP, 2019

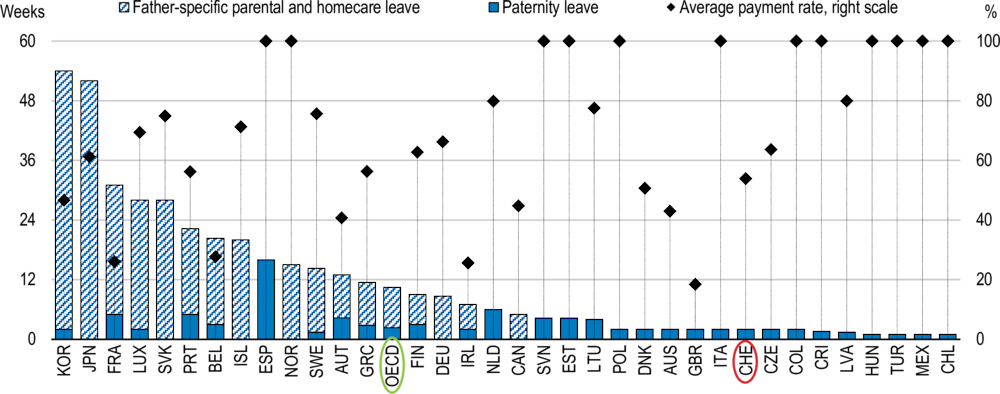

Longer paternity and parental leave reserved for fathers would help reduce gender stereotypes and raise labour market activity of mothers. Paternity leave of two weeks was introduced quite recently, in 2021. While a step in the right direction, total paternity and parental leave specific to fathers together remain eight weeks shorter than in the OECD on average (Figure 3.12). The average replacement rate is also comparatively low, lowering incentives for families to take up the benefit. Data from the Federal Social Insurance Office show that in 2022, 69 users of paid paternity leave were recorded per 100 live births. This is above average across the 18 OECD countries with available data, where 57 users were recorded per 100 live births, but significantly behind Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Slovenia, with more than 90 users/recipients per 100 live births (OECD, 2022b). Several OECD countries - Luxembourg, Sweden, Norway and Iceland - have reserved parts of parental leave for fathers, of between 12 and 26 weeks at replacement rates (for average earners) ranging from 73% to 96% (OECD, 2021b). In these countries, sufficiently generous replacement rates together with the loss of the leave entitlement for the couple if not taken by the father provide strong incentives for fathers to stay at home for a longer period. Evidence shows that increase in earmarked leave for fathers can lead to shorter maternal leave and an increase in mothers’ earnings for up to eight years after birth (Druedhal et al., 2019). It can also increase the likelihood for women to work full-time (Patnaik, 2019). Fathers’ leave-taking is also linked to their higher involvement in unpaid work within their family, both for childcare and regular housework, with an effect that persists well beyond the years of actual leave-taking (Tamm, 2019; Knoester et al., 2019).

Figure 3.12. Parental leave specific to fathers is short and the replacement rate relatively low

Length of paid paternity leave and paid parental and home care leave reserved for fathers and average payment rate, 2022

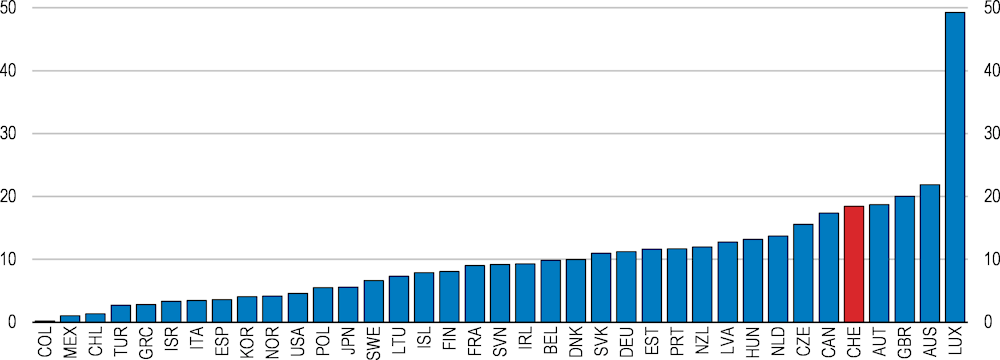

Swiss women get paid less than men even for similar jobs. On average, full-time employed women earn 15% less than men (Figure 3.13). According to the Federal Statistical Office estimates, about 48% of the gender pay gap cannot be explained by factors such as professional status, years of services, sector of activity or level of education (FSO, 2022a). Earning higher wages, equal to those of men, would create better incentives for women to work longer hours.

Reducing the gender pay gap is one of the top priorities of the 2030 Gender Equality Strategy (Federal Council, 2021b). A law from 2018 requires companies with at least 100 employees to conduct regular gender pay audits and inform employees and shareholders of the results. However, the FSO reports the largest unexplained wage difference in small enterprises (FSO, 2022a). Launched by the federal government in 2020, Logib Module 2 webtool – internationally recognised as good practice – enables all employers, including small companies, to carry out a gender equal pay analysis and learn whether they comply with the requirement of equal pay between women and men. The 2030 Gender Equality Strategy introduced an examination and control of equal pay in small and medium-sized companies that enter bidding for public contracts or receive public subsidies. These efforts should be continued if effective.

Figure 3.13. Full-time employed women get paid less than men

Gender gap in median earnings of full-time employees, %, 2021 or latest available year

Note: The gender wage gap is calculated as the difference between the median earnings of men and of women relative to the median earnings of men.

Source: OECD Employment Database, http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm

Increasing labour market participation of older workers

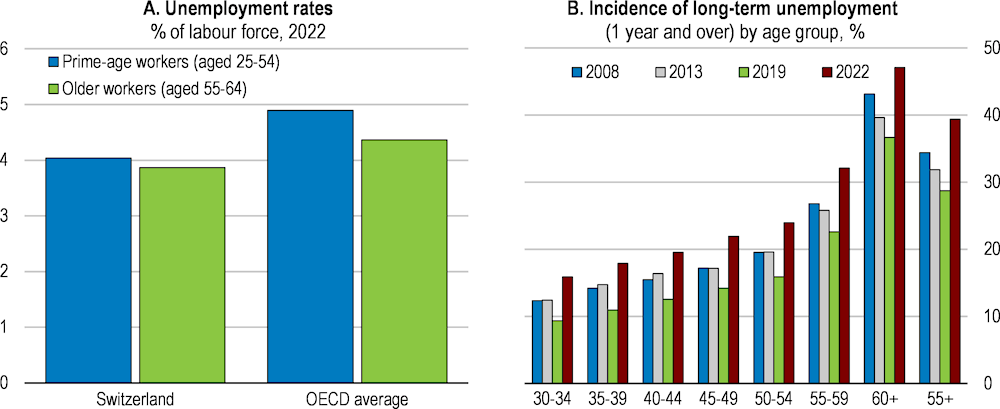

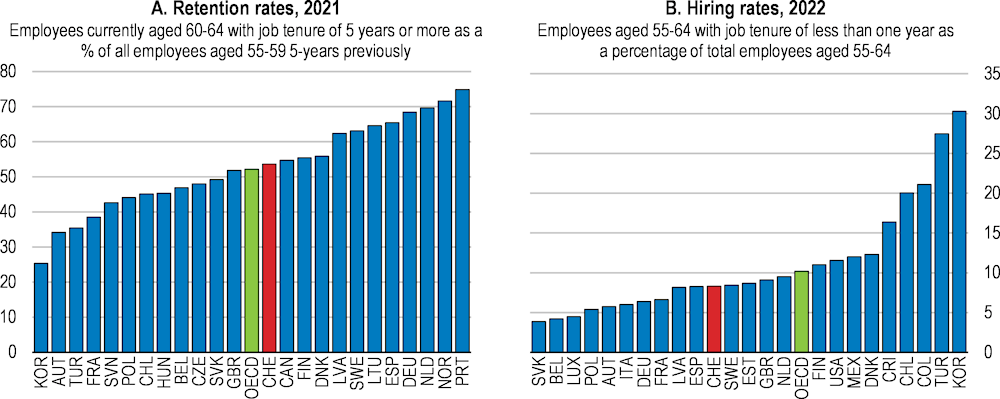

Reform could help bring more older workers to work, raising incomes, easing labour shortages and improving sustainability of the mandatory pension system. According to the OECD Scoreboard on Older Workers, the education level of older workers (55-65) is higher and they participate in training more often than in most other OECD economies. The retention rate for older workers is around the OECD average. Yet, the rate of hiring older workers is relatively low (Figure 3.14). The unemployment rate for older workers is slightly lower than for prime-age workers. But once unemployed, older workers find it more difficult than prime-age workers to reintegrate into the labour market (SECO 2019 and 2021; OECD, 2022a). The risk of long-term unemployment is therefore significantly higher for older workers (Figure 3.15).

To support older workers’ re-employment, the authorities launched a reform package that includes additional spending on activation policies for older workers. The measures include additional funding to cantons to enable them to better support hard-to-place jobseekers, especially seniors, with more individualised measures such as counselling, coaching or mentoring. While in Switzerland people are not granted access to activation policies funded by the unemployment insurance for two years after the expiration of their unemployment benefit entitlements, an exceptional access to training has been granted for jobseekers aged over 50. However, while welcome, these programmes are only temporary and set to end in 2024. Their efficiency should be assessed with a view to expanding those that bring positive results.

In 2021, a reform introduced transition benefits up to retirement for individuals aged 60 or over who have exhausted their unemployment benefits. These benefits are means- and asset-tested and have certain eligibility criteria (at least 20 years of contributions to the pension scheme of which at least five years after the age of 50). Still, as discussed in previous OECD Surveys (OECD, 2019a and 2022a) the scheme risks reducing incentives for eligible people to undertake training and to search for work before reaching the age of 60. Such effects have been observed in Finland (OECD, 2018) and Poland (Gałecka-Burdziak and Góra, 2017). As suggested in the last Survey (OECD, 2022a) supplementing eligibility conditions with requirements to participate in community services or continue looking for a job would mitigate this risk.

Figure 3.14. There is room to strengthen labour demand for older workers

Note: OECD is an unweighted average of OECD member countries shown.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Job tenure database.

Figure 3.15. Once unemployed, older workers find it more difficult to reintegrate into the labour market

Financial disincentives for employers also weigh on the employment of older workers. Compared to other OECD countries, wages rise more with seniority, raising the risk that older workers’ wages grow above their productivity. According to the OECD Scoreboard on Older Workers, full-time gross earnings of older workers (55-64) in Switzerland are 13% above earnings of prime age workers, compared to 6% in the OECD on average. Furthermore, minimum contributions to the second-pillar pension funds rise with age, with employers paying at least half of contributions. Currently, the contribution rate represents 7% of the insured salary for the 25-34 age group, 10% between 35 and 44, 15% between 45 and 54 and 18% for older workers, creating disincentives to hire older workers. Flattening the contribution rates would be one way to improve the employability of older workers. As envisaged in the current reform of the second pillar, only two different contribution rates could be maintained, at 9% for workers aged 25-44 and at 14% for older workers, which would lead to a significant decline in the contribution rate for workers above 55. An alternative way to achieve this goal would be to adjust employers’ contribution to a flat rate so that only employees’ contributions increase with age.

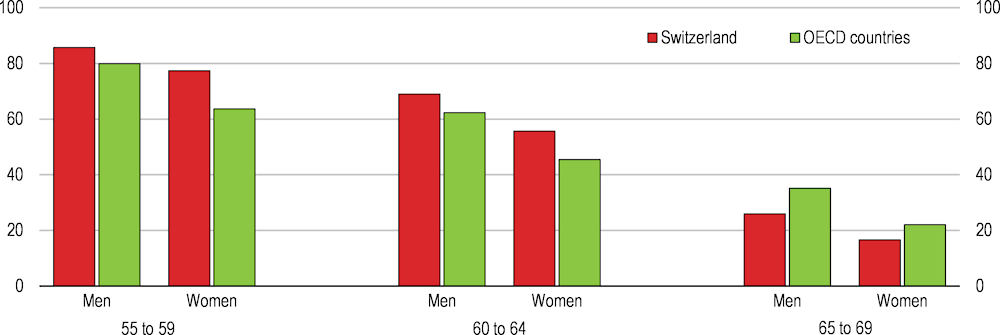

Lengthening working lives can also be achieved through incentives within the pension system and the flexibility to combine retirement and work. Early retirement in the first pillar is possible from the age of 63. Still, 23% of the 55-64 old were out of the labour force in 2020 (SECO, 2021), and more than a quarter of workers retire before reaching age 60 (OECD, 2019b). Employment also falls significantly after the statutory retirement age. Whereas Switzerland records high employment rates overall, after age 65, the employment rate shows a steep decline to below the OECD average (Figure 3.16).

Figure 3.16. Employment rates fall steeply after 65

Employment rate, % of respective population, 2022

A recent reform brings additional flexibility to combine work and pension benefits. From 2027 onwards, workers will be free to choose to retire between the age 63 and 70. In addition, they will be able to gradually reduce working hours while claiming a partial pension. As opposed to the current situation, contributions paid beyond age 65 will count towards pensions rights. The reduction or increase in pension benefits for early or deferred retirement, respectively, will be done in actuarially neutral way, but will differ for low incomes. The conversion factors will be set by the Federal Council before the system comes in effect, given life expectancy at the time.

Greater flexibility to combine work and pension is welcome. However, given that early retirement is already quite common, removing penalties may further encourage earlier retirement. The age band for retirement – between 63 and 70 years of age – could have a higher upper limit (75 in Norway and no limit in Sweden) and the earliest age of retirement, together with the conversion factor, should evolve with life expectancy. In Norway, each cohort gets a different life-expectancy conversion rate, based on remaining life expectancy, determined when the cohort reaches 61 years of age (OECD, 2021c).

To raise employment in old age, both retirees and employers need to be aware of and embrace available flexibility. International practice shows that options for flexible retirement – on the time of retirement and on combining pension benefits and work – must come with renewed efforts to foster financial literacy and transparency (OECD, 2019b). Beneficiaries need transparent and reliable information on the benefits that they can expect to receive under different scenarios concerning when and how they retire (completely or partially). In addition, older workers need flexibility to be able to review and adapt their choices as their employment prospects, health situation or family circumstances change before or after retirement. Enough flexibility is also needed on the side of employers, who need to have programmes for gradual exit from employment in place (OECD, 2019b).

Continuing to attract and retain skilled foreign workers

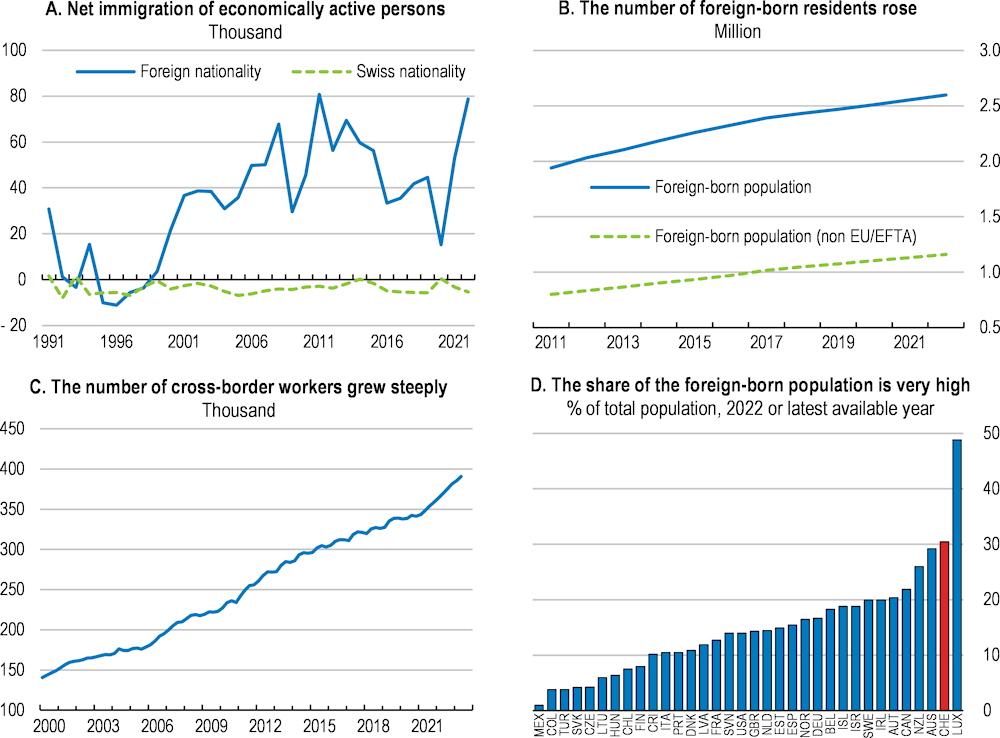

Immigration has been key for Switzerland’s economy in terms of labour, skills and demography. Over the past two decades, Switzerland has experienced a large influx of foreign workers. Net immigration has been highly positive, with the net inflow of more than 40 000 foreign nationals per year over the last two decades (Figure 3.17). The number of residents with migration background (foreign-born) rose by 37% between 2011 and 2022, compared to 10% for the total population. The number of cross-border workers has more than doubled since 2000. In 2021, the foreign-born population represented 30% the total population (Figure 3.17), second in the OECD, behind Luxembourg.

Figure 3.17. Immigration has been key for Switzerland’s economy

Source: FSO, Labour Market Accounts (LMA); Eurostat; FSO, Cross-border Commuters Statistics (CCS); OECD International Migration Database; OECD Population Statistics.

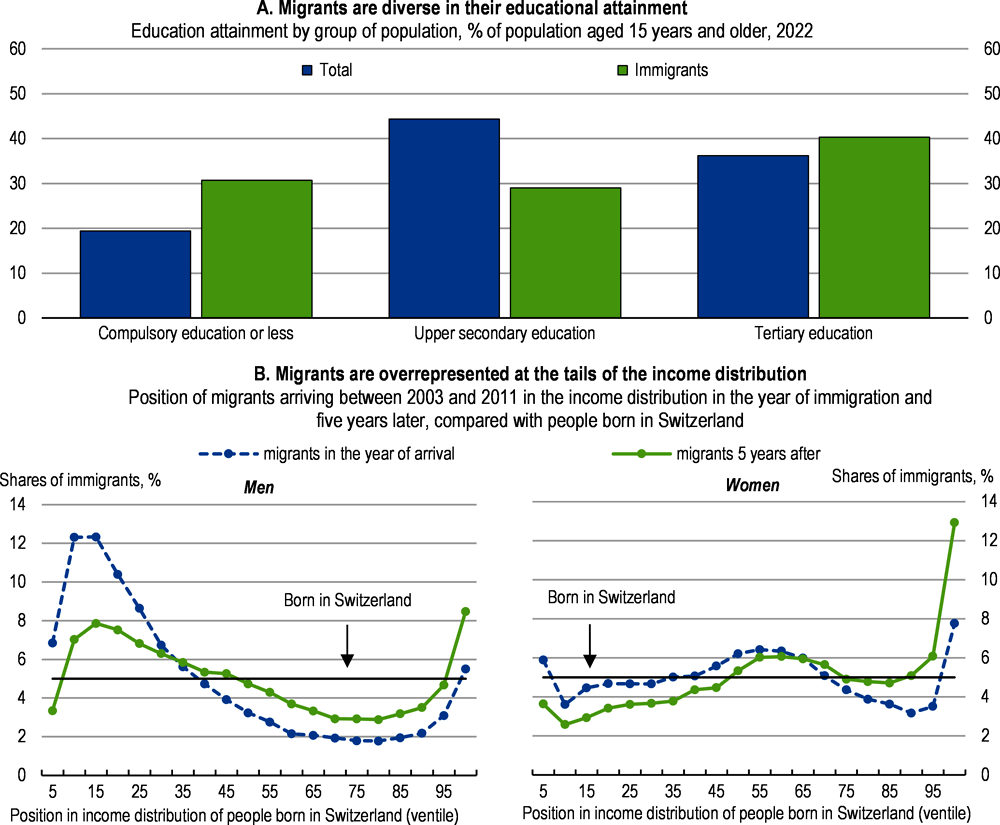

Migrants form a population that is very diverse not only in their geographical origins but also in terms of their socio-economic characteristics and backgrounds. This diversity has grown further in recent decades (FSO, 2020). Since 2002, Switzerland is part of the agreement on the free movement of persons with the EU/EFTA, and roughly 2/3 of migrants come from this area, with those born in Italy, Germany, Portugal and France most represented. The rest come from all over the world, in largest numbers from Türkiye, former Yugoslavia, Brazil, the United States and Sri Lanka (OECD, 2022a). Migrants are diverse also in terms of educational attainment. They are much more likely than natives to have only completed mandatory education but also more likely to have a tertiary education degree (Figure 3.18). There are many immigrants with low skills and low incomes. On the other hand, there is a significant group of highly qualified and highly mobile professionals earning high incomes (Figure 3.18). An increasing number of immigrants are to be found among highly qualified managers (FSO, 2020).

Figure 3.18. Migrants form a diverse population

Note for panel B: The study group comprises migrants aged between 25 and 55 who arrived in Switzerland between 2003 and 2011 and who stayed in the country for at least five years and earned an income from gainful employment every year. The control group consists of people born in Switzerland aged between 25 and 55 who also earned labour income in at least five consecutive years. The lines with dots show the proportion of migrants found in each income ventile of people born in Switzerland. The blue lines show the distribution of migrant men and women in the year of arrival in Switzerland; the green lines show the distribution five years after immigration. If the income distributions of migrants and people born in Switzerland were identical, these lines would be horizontal at 5% (i.e., 5% of migrants would fall in every income ventile of people born in Switzerland)

Source: FSO, Swiss Labour Force Survey (SLFS); Federal Statistical Office (FSO), University of Neuchâtel (UNINE), University of Fribourg (UNIFR), A Panorama of Swiss Society 2020: Migration - Integration - Participation.

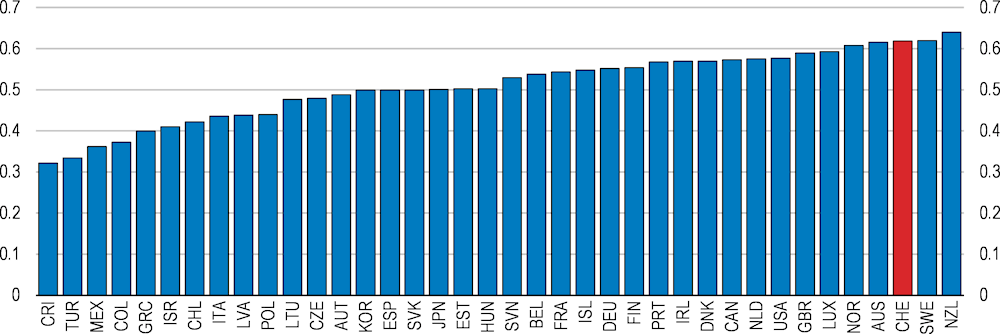

Switzerland remained among the top five most attractive OECD countries for highly skilled migrants in 2023 (Figure 3.19), thanks to high standard of living and an attractive tax and benefit system (OECD, 2023b; Tuccio, 2019). A strong labour market, high productivity and high wages have been able to attract and absorb many skilled workers from abroad.

Active steps should be taken to maintain attractiveness, including by ensuring favourable migration policies for highly skilled migrants from non-EU/EFTA countries. These migrants have proven an important source of skilled workforce in recent years (FSO, 2020). Moreover, given fast ageing in Switzerland and EU countries, third-country nationals will increasingly become the key source to boost the working-age population. The global competition for talents continues, reinforced by widely experienced labour shortages. Countries are finding new ways to attract highly educated migrants and remote workers (OECD, 2022a). By continuing to set itself as an attractive long-term destination for skilled third-country migrants, Switzerland could sustainably boost productivity and growth, while helping to ease labour shortages and ageing pressures.

Figure 3.19. Switzerland remains among the most attractive countries for global talent

Attractiveness of OECD countries for potential migrants, highly skilled workers

Note: The OECD Indicator of Talent Attractiveness measures the relative attractiveness of countries from a multidimensional perspective, considering both the migration policy framework and other factors that affect the ability to attract and retain international talent. Values from 0 (lower attractiveness) to 1 (higher attractiveness). The ranking is based on default equal weights across dimensions and does not include the health system performance dimension.

Source: OECD Indicators of Talent Attractiveness (ITA), https://www.oecd.org/migration/talent-attractiveness/.

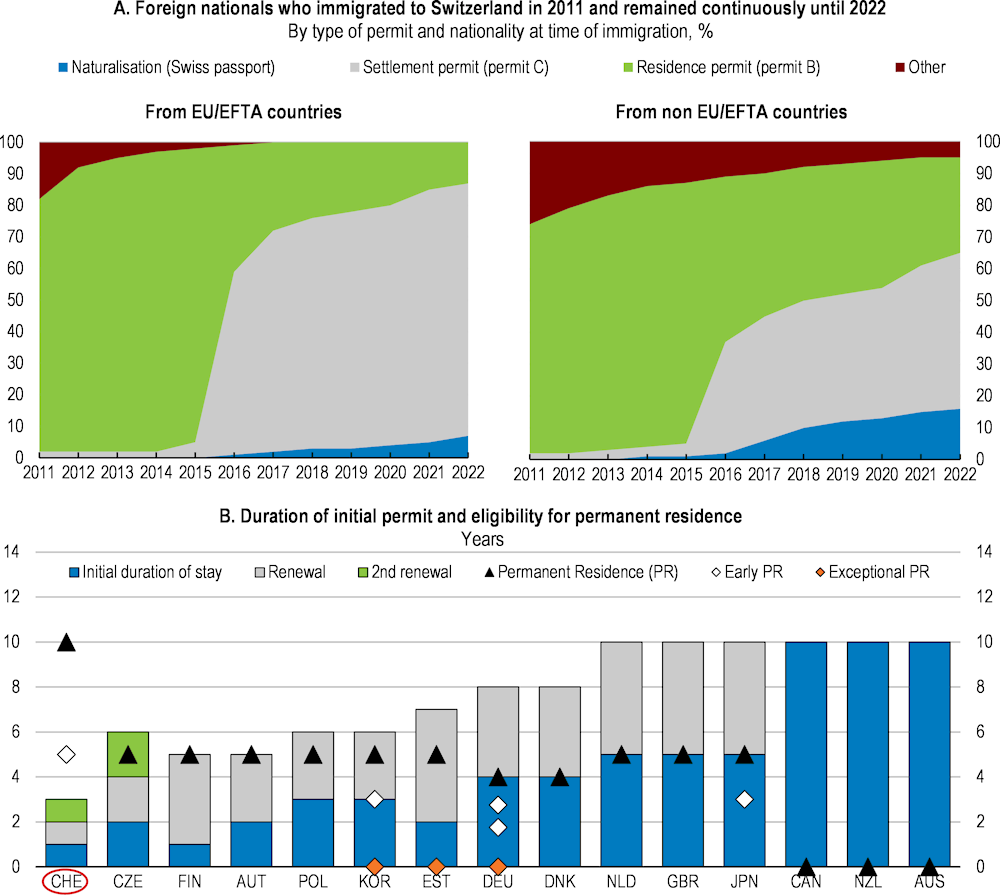

Economic migration from non-EU/EFTA countries remains subject to strict quotas, currently at 8 500 per year, unchanged since 2019. Moreover, third-country nationals are allowed to migrate for work in Switzerland only in senior management positions, as specialists or other qualified personnel (university degree or special training and several years of professional experience). To employ a third-country national, Swiss employers need to prove that no equivalent worker form the EU/EFTA area is available for the job and that qualifications and salary requirements are met (not worse than for domestic workers). Once a working permit is secured from relevant cantonal authorities the job can be started. Depending on the job contract either a short-term (less than a year) residence permit (L) or residence permit (B) is issued. The residence permit (B) can include restrictions such as having to work in a specific job or live in the canton which granted the permit. Family members also have the right to work without being subject to quotas, preference for nationals or qualifications requirements, however, such employment is limited by the validity of the original permit. The residence permit (B) for non-EU/EFTA migrants is valid for one year, after which it can be renewed. After five to ten years, a settlement permit (C) can be issued, subject to specific conditions (in particular knowledge of one of the national languages).

Permit rules and paths to full integration for skilled non-EU/EFTA migrants need to be attractive enough. According to the data by the Federal Statistical Office (FSO, 2022b) on foreign nationals who stayed continuously in Switzerland for ten years, there is markedly faster transition from residence permit B to the settlement permit C for EU/EFTA migrants than for third-country nationals (Figure 3.20, panel A). Migrants face more lengthy, complicated and costly paths to permanent residence in Switzerland than in most OECD countries (Figure 3.20, panel B). Yet, permanent residence or naturalisation can have important implications for immigrants’ social integration and labour market outcomes. A number of OECD countries have taken steps to encourage more migrants to pursue citizenship, notably Germany, the United States and Estonia (OECD, 2022a). Furthermore, in Switzerland, the acquisition and use of land and real estate by non-EU/EFTA migrants without permanent residence (settlement permit C) - as well as for EU migrants without principal residence (also known as effective or de facto residence) in Switzerland - is highly restricted (OECD, 2022d, FSO, 2020).

Figure 3.20. Non-EU/EFTA migrants face lengthy paths to permanent settlement and citizenship

Note for panel A: Other category includes people with short-term residence permit (permit L) and in asylum process (permits N and F).

Source: FSO, Longitudinal demographic statistics (DVS); OECD/European Commission (2023), Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023: Settling In, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1d5020a6-en.

International students from third countries could also be better retained after graduation. Switzerland is an attractive destination for international students. Close to 20% of tertiary students come from abroad, 35% of them from non-EU countries (Figure 3.21). According to Economiesuisse, the Swiss Business Federation, only 10-15% of these students remain in the country after their studies. Evidence shows that international students are three times more likely than domestic students to study natural sciences, mathematics and statistics (OECD, 2022c), where there is large and rising demand for skills. However, Swiss university graduates from non-EU countries have only 6 months to find a job after completing their studies to be allowed to stay in Switzerland. This is short in international comparison (Figure 3.22). In other OECD countries, the time that graduates can remain in the country upon graduation to look for a job is typically between 12 and 24 months, and in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom even 3 years. The Swiss parliament currently considers facilitating the stay and access to the labour market for third-country nationals with Swiss university degrees in areas with a proven shortage of skilled workers.

Figure 3.21. Switzerland attracts a high number of international students

International students, % of total, 2021

Figure 3.22. Swiss university graduates from non-EU countries have a short time to find a job after graduating

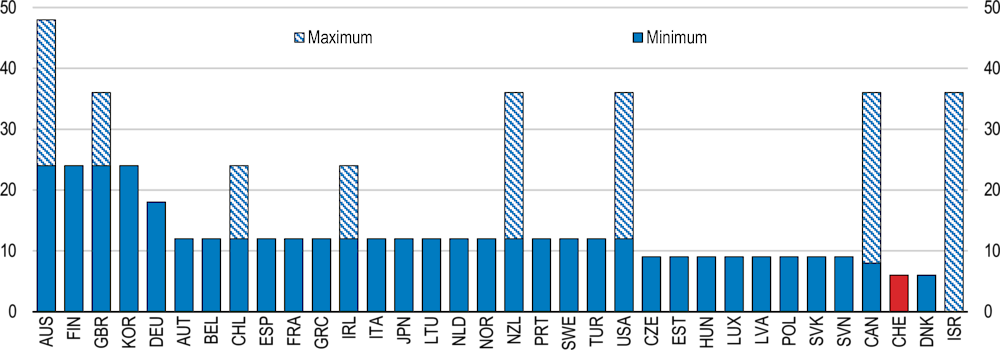

Minimum and maximum duration of stay, typically, to search for a job following graduation, in months, 2022

Note: AUS: Graduate Work stream, usually up to 18 months (increased to 24 months as a COVID concession); Post-Study Work stream two years for bachelor’s and up to four years for PhD graduates. GBR: two years for bachelor’s and master’s, three years for PhD. NZL: one to three years depending on level and duration of prior programme. CAN: equal to the prior duration of studies. USA: refers to post-completion Optional Practical Training (OPT), can be extended by additional 24 months for graduates in STEM subjects. IRL: Graduates with an award at Level 8 or above can apply for 12 months, those with Level 9 or above can renew for additional 12 months. EST: 270 days. ISR: only for graduates in High Tech related fields of study. Spain is planning to increase the postgraduate extension to two years.

Source: OECD (2022), International Migration Outlook 2022.

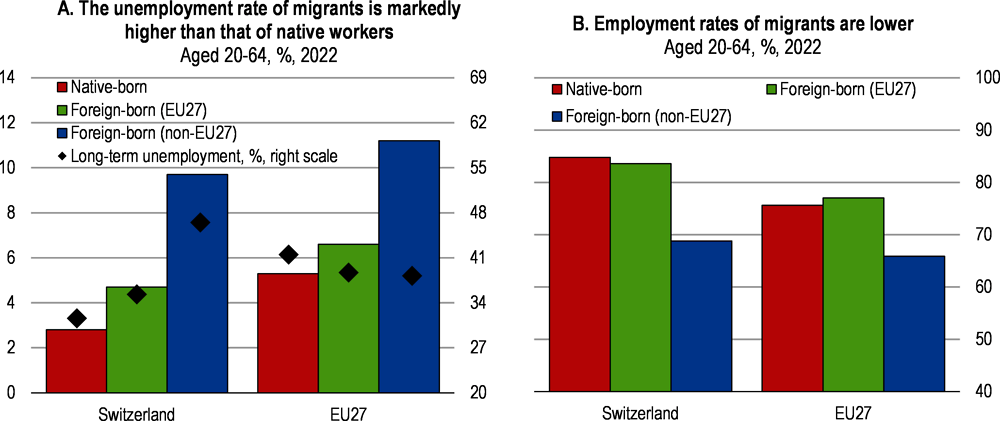

There is also room to boost employment of existing migrants with poor labour market performance. Foreign-born from non-EU/EFTA countries record significantly higher unemployment rates than natives, 9.7% versus 2.8% in 2022 (Figure 3.23). While migrants’ labour market integration improves significantly over time and that their employment rates and wages improve (Figure 3.18, panel B), the employment rate nevertheless stays below those of natives, most notably for non-EU/EFTA migrants (Figure 3.23). Moreover, migrant women are more likely than men to have moved for family reasons, and their labour market participation rates remains markedly lower (FSO, 2020).

Figure 3.23. Immigrants tend to have worse labour market outcomes than natives

Note: For panel A, diamonds show the share of long-term unemployment (12 months or more) as a percentage of the total unemployment for each category.

Source: Eurostat.

Upskilling low-skilled immigrants is one way to help migrants find jobs or gain new skills and become more employable. As discussed in previous Surveys (OECD, 2022a; 2019a and 2017) expanding the supply and uptake of high-quality language training at all ages, adult education, bridging courses, work placements and improved recognition of foreign qualifications for non-EU/EFTA citizens would help them to maximise the use of their skills. For instance, cantons offer pre-VET programmes to young immigrants (up to age 23) or refugees (up to age 35), to help them acquire needed core competencies, including language skills, before enrolling in VET programmes. Authorities should consider extending it to a larger group of migrants by raising the age limit for access. Employment services could provide more substantial up-skilling measures better geared towards prior learning of migrants. In addition, temporary job-placement incentives paid to employers can also play a role, to overcome information asymmetry with respect to the prior qualifications of migrants and giving them a chance to demonstrate and improve their skills during the benefit period (Duell et al., 2010, OECD, 2022a). Targeted measures to expand affordable childcare and measures to reduce disincentives for second earners will also help bring more migrant mothers to work.

Table 3.1. Past recommendations on boosting labour participation

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Foster geographical mobility by adjusting the tenancy law to reduce restrictions on rent increases, accompanied with targeted housing allowances. |

No action taken. |

|

Increase the effectiveness of pathways between vocational and general streams by increasing the academic component of the vocational curriculum and vice-versa. |

The ongoing revision of the vocational baccalaureate ensures eligibility to study at universities of applied sciences. In higher vocational education and training (tertiary level), the federal government introduced subject-oriented funding for preparatory courses for federal examinations in 2018 |

Table 3.2. Recommendations

|

MAIN FINDINGS |

RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

Raising the activity rate of women |

|

|

The gender income gap is high in Switzerland, in part due to high incidence of part-time employment. The tax and benefit systems and a high cost of childcare contribute to lower working hours and lower labour incomes for women. |

Reduce disincentives to work for second earners, by moving from family-based to individual-based taxation or through tax adjustments and slower withdrawal of benefits. Keep expanding the supply of childcare and provide targeted measures (mean-tested fee reductions, childcare benefits or tax credits) to improve affordability. Ensure effective coordination and monitoring of quality control across different childcare providers. Expand paternity leave with a statutory parental leave system including entitlement reserved to fathers. |

|

Women get paid less than men for similar jobs. Close to half of the gender pay gap cannot be explained by factors such as professional status, years of services, sector of activity or level of education. |

Continue efforts to extend the examination and control of equal pay to small and medium-sized enterprises. |

|

Increasing labour market participation of older workers |

|

|

Once unemployed, older workers have more difficulties than prime age workers to find a job. Seniority wages and rising pension contribution rates create financial disincentives for firms to hire older workers. |

Flatten the age-related progressivity in pension fund second-pillar contribution rates as planned. Assess and, if effective, scale-up pilot activation programmes for older workers. |

|

More than a quarter of workers retire before reaching age 60. Employment also falls markedly at the statutory retirement age. From 2027 onwards, workers will be free to choose to retire between the age 63 and 70 and will be able to gradually reduce working hours while claiming a partial pension. |

Introduce greater flexibility to combine retirement and work as planned and link the parameters of the flexible retirement system (earliest age of retirement, the conversion factor from accumulated pension entitlements to annual pension) to life expectancy. Help workers make sound retirement choices, by expanding information and education campaigns on retirement-age choice. |

|

Attracting and retaining skilled foreign workers |

|

|

Attracting skilled migrants from non-EU/EFTA will become increasingly important to boost working-age population and skills. In Switzerland, third-country migrants face lengthy and costly paths to permanent settlement and citizenship. |

Streamline administrative processes for highly skilled migrants from non-EU/EFTA countries, including by relaxing permit rules and paths to naturalisation. |

|

Switzerland is an attractive destination for international students, but Swiss university graduates from non-EU countries have only 6 months to find a job after completing their studies to be allowed to stay in Switzerland, which is short in international comparison. |

Extend the amount of time Swiss university graduates from non-EU countries have to find a job upon graduation from 6 months to 24 months. |

|

Some foreign nationals have low skills. They record significantly higher unemployment rate than natives and employment rates are markedly lower, especially for women. |

Expand the supply and uptake of upskilling courses and improve recognition of foreign qualifications for non-EU/EFTA citizens. Expand temporary job-placement incentives paid to employers. |

References

CSEC-N (2021), Renforcement du soutien de la confédération à l’accueil extrafamilial pour enfants. Communiqué de presse, Vendredi 19 février 2021. Commission de la science, de l'éducation et de la culture du Conseil national.

Druedhal, J., M. Ejrnæs and T.H. Jørgensen (2019), Earmarked paternity leave and the relative income within couples. Economics Letter 180, 85-88.

Duell, N., P. Tergeist, U. Bazant and S. Cimper (2010), Activation Policies in Switzerland, OECD Social Employment and Migration Working Papers.

Ekonomifakta (2022). Kommunernas kostnader

Federal Council (2021a), Annex – Gender equality strategy 2030. Current situation and statistics. [In French].

Federal Council (2021b) Gender equality strategy 2030.

FSO (2023), Indicateurs de l'égalité entre femmes et hommes et de la conciliation emploi et famille 2/2023. Federal Statistical Office.

FSO (2022a), The overall gender wage gap decreased in 2020. Federal Statistical Office, Press Release.

FSO (2022b), Longitudinal demographic statistics (DVS).

FSO (2020), A Panorama of Swiss society 2020. Migration – Integration – Participation. Federal Statistical Office, FSO.

Gałecka-Burdziak E. and M.Góra (2017), “How do unemployed workers behave prior to retirement? A multi-state multiple-spell appoach?, IZA Discussion Paper No. 10608.

Knoester, C., Petts, R., and Pragg, B. (2019), Paternity Leave-Taking and Father Involvement among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged U.S. Fathers, Sex Roles, Vol. 81/5-6, pp. 257-271.

OECD (2023a), Joining Forces for Gender Equality: What is Holding us Back?, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2023b), What is the best country for global talents in the OECD?, Migration Policy Debates, No 29, March 2023.

OECD (2022a), OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022b), PF2.2: Parents’ use of childbirth-related leave, OECD Family database.

OECD (2022c), International Migration Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022d), OECD Services trade Restrictiveness Index; Switzerland – 2022. OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2021a), Switzerland – Starting Strong VI Country Note.

OECD (2021b), PF2.1. Parental leave systems. Updated: December 2022, OECD Family database.

OECD (2021c), Pensions at a Glance 2021: Country profile - Norway, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD(2020), Is Childcare affordable? Policy Brief on Employment, Labour and Social Affairs.

OECD (2019a), OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2019b), Working Better with Age, Ageing and Employment Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Finland 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OFAS (2023), Avis du Conseil Fédéral (FF 2023 598) du 15 février 2023 concernant l’Initiative Parlementaire 21.403 « Remplacer le financement de départ par une solution adaptée aux réalités actuelles ». Office fédéral des assurances sociales (OFAS)

Patnaik, A. (2019), Reserving time for daddy: the consequences of fathers’ quotas, Journal of Labor economics, 2019, vol.37, no.4.

SECO (2021), Indicateurs de la situation des travailleuses et travailleurs âgés sur le marché suisse du travail 2021, State Secretariat for Economic Affaires.

SECO (2020), Employment trajectories above the age of 50 in Switzerland: Labour market integration of older workers, State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, Arbeitsmarkstudies, 2020.

SECO (2019), Indicateurs de la Situation des Travailleuses et Travailleurs Agés sur le Marché Suisse du Travail [Indicators of the Situation of Older Workers in the Swiss Labour Market], Documents for the 2019 Annual Conference on Older Workers, State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, Bern.

SNB (2023), Quarterly Bulletin 1/2023 March. Swiss National Bank.

Tamm, M. (2019), Fathers’ parental leave-taking, childcare involvement and labor market participation, Labour Economics, Vol. 59, pp. 184-197.

Tuccio, M. (2019), Measuring and assessing talent attractiveness in OECD countries, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 229, OECD Publishing, Paris.