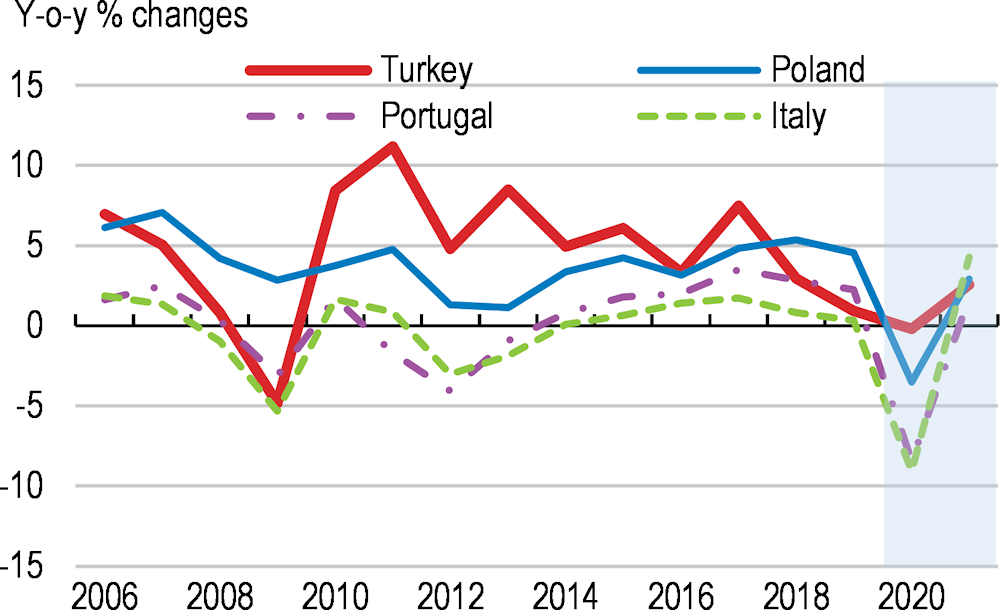

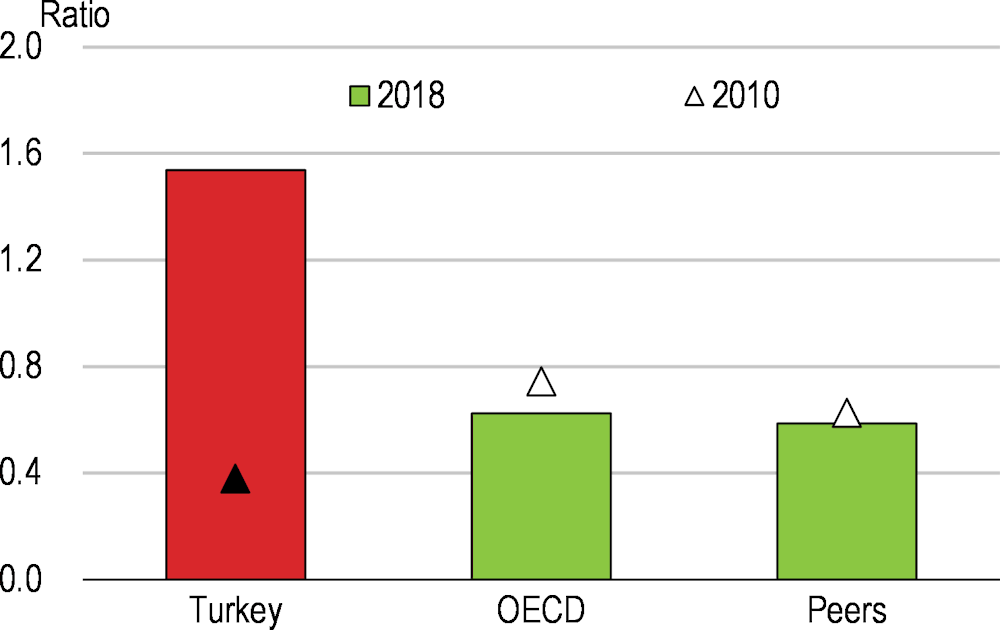

Turkey went into the COVID-19 crisis with sound public finances but extensive off-balance sheet commitments. This resulted from massive government stimulus in 2019 and 2020 and came mainly in the form of government credit guarantees and through lending by public banks. In particular, concessional credits by public banks to households and businesses during the pandemic has increased the share of quasi-fiscal expenditures and amplified contingent liabilities for public finances. Addressing weak fiscal transparency by publishing a regular Fiscal Policy Report encompassing all contincent liabilities would help to improve confidence on financial markets, increasing room for fiscal manoeuvre.

The pandemic amplified monetary policy challenges. Inflation is high and has long been stuck well above the official target of 5%. Actual and expected inflation rose after the COVID-19 shock. Monetary policy interventions related to the pandemic supported economic activity, the exchange rate and liquidity of banks. They also added to concerns whether monetary policy prioritises growth and employment over price stability. Faced with massive capital outflows and a sharp exchange rate depreciation, the Central Bank started to tighten liquidity in August, increased the policy interest rate in late September, the effective funding rate in October, and, as this proved insufficient, again the policy rate in November. It also normalised its policy framework. Foreign reserves remained nevertheless low and risk premia high.

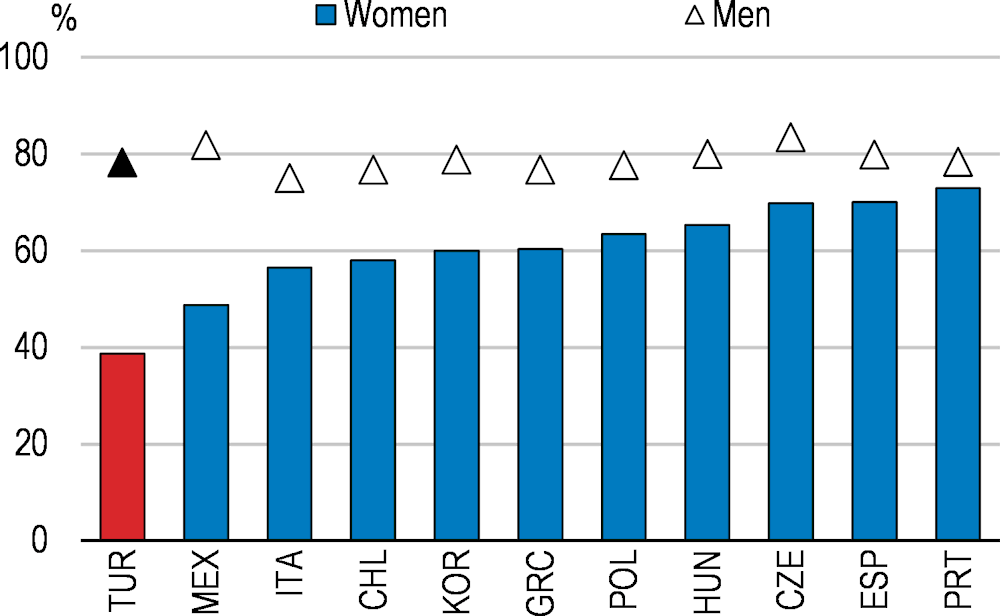

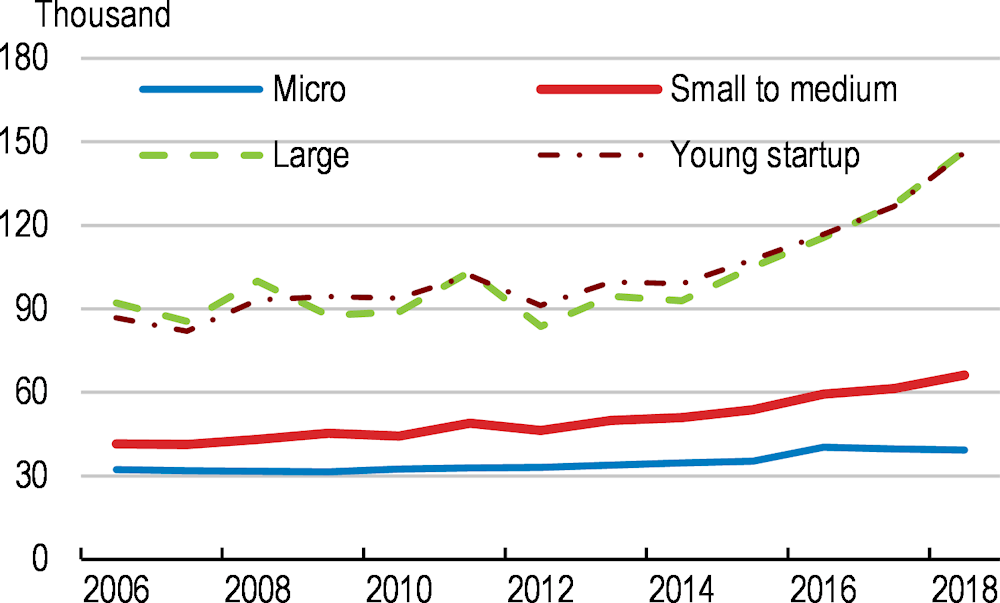

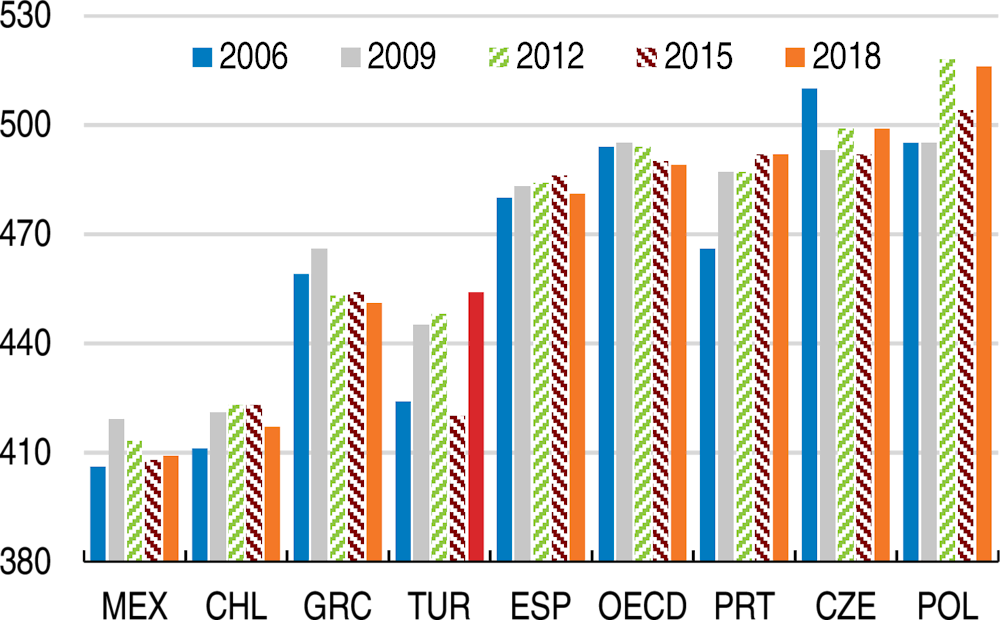

The pandemic exacerbated structural challenges related to high unemployment, low labour force participation and widespread informality. The crisis has hit the informal sector workers and the self-employed the hardest because they are concentrated in labour- and contact-intensive activities where physical distancing is hard to apply. They are also excluded from employment-related social safety nets. While there has been progress in creating quality jobs over the past 15 years, bringing with it major gains in well-being, challenges have remained. The number of jobs decreased strongly after both the 2018 financial turmoil and the COVID-19 shock. Labour force participation, in particular by women, is still very low. High legal employment costs, including one of the OECD’s highest minimum-to median-wage ratios and some of the most restrictive permanent and temporary employment regulations, and an expensive severance system, foster informality. They impede a more efficient allocation of resources towards the relatively narrow but gradually growing share of fully formal firms and higher technology start-ups.