Patrick Lenain

OECD

Ben Westmore

OECD

Quoc Huy Vu

Viet Nam Academy of Social Science

Minh Cuong Nguyen

Asian Development Bank

Patrick Lenain

OECD

Ben Westmore

OECD

Quoc Huy Vu

Viet Nam Academy of Social Science

Minh Cuong Nguyen

Asian Development Bank

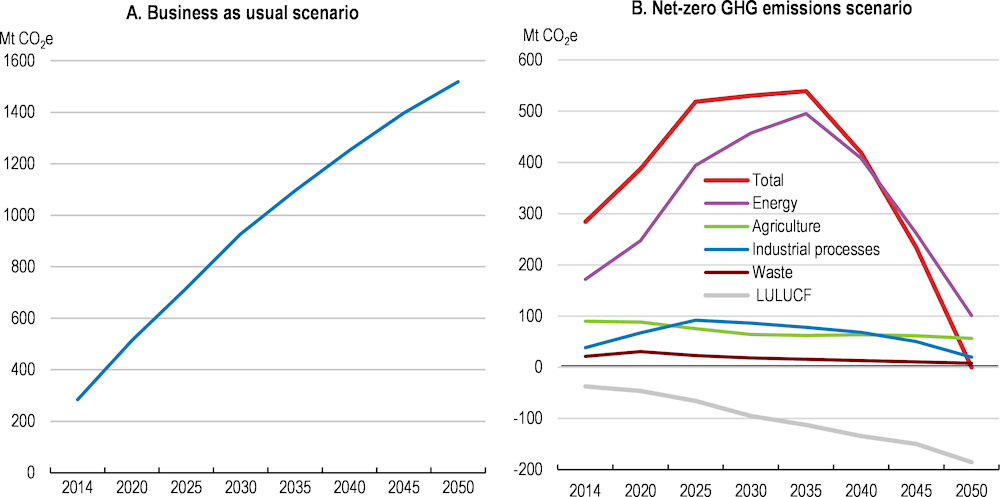

Viet Nam has implemented extensive reforms since the late 1980s, becoming one of the most open markets in Southeast Asia. Still, sustaining high economic growth in the coming decade will require additional efforts to boost labour productivity. To advance reforms, the government will need to take bold action to reduce state involvement and secure a level playing field among all market participants, including state-owned enterprises. Viet Nam’s recent rapid digitalisation driven by the private sector proves that competition is crucial to absorb and disseminate the latest technologies. The commitment to net zero emissions by 2050 creates challenges but also opportunities to stimulate innovation and pursue greener growth. Against this background, this chapter discusses how Viet Nam can make further progress in terms of levelling the playing field for businesses, providing an enabling environment for the digital transformation and moving towards a low carbon economy.

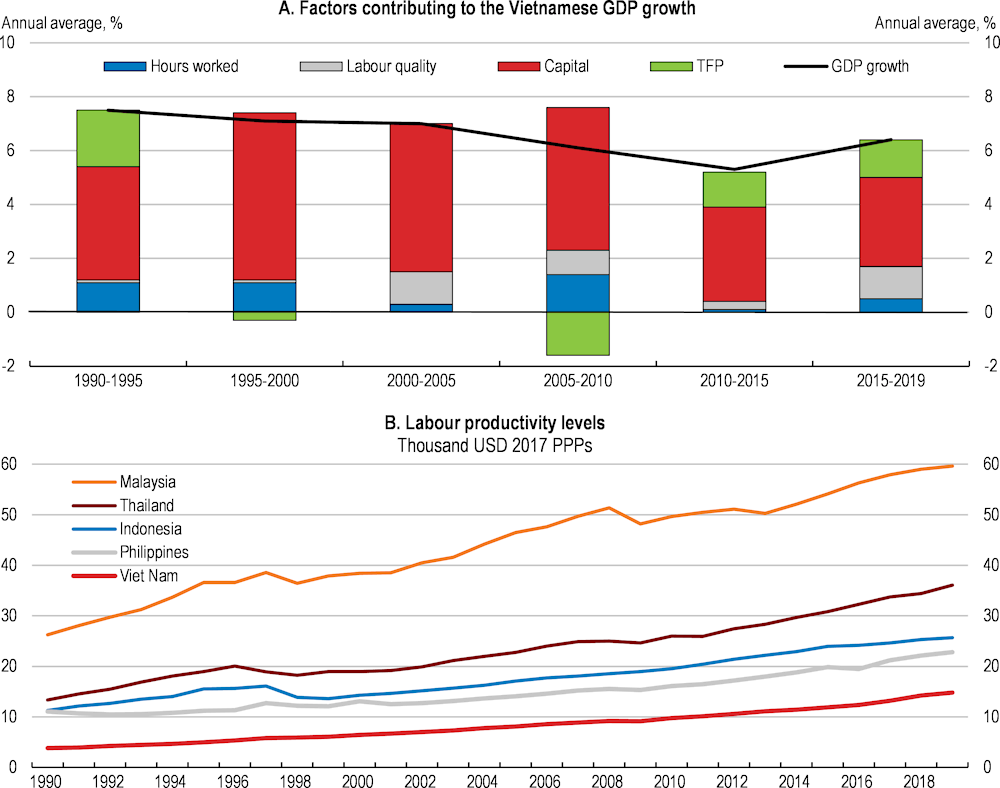

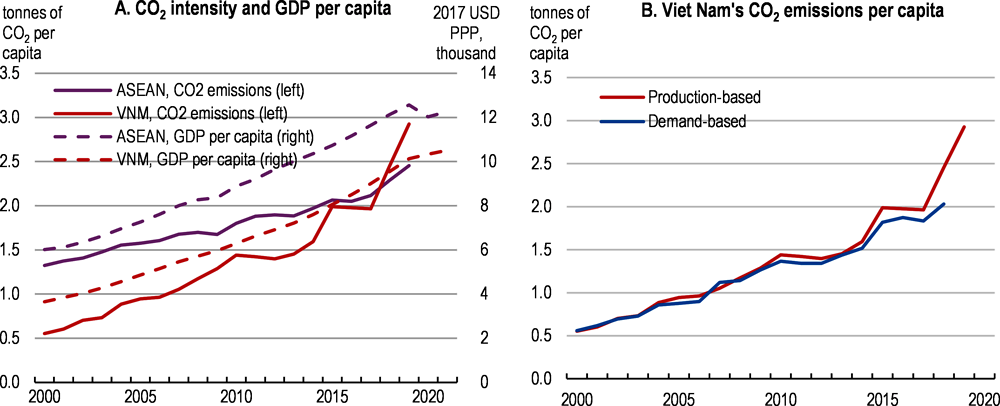

Viet Nam’s strong growth over the past three decades was largely based on factor accumulation as structural reforms implemented since Doi Moi in 1986 have encouraged large amounts of fixed investment – both by domestic and foreign investors (Figure 2.1). The country’s abundant natural resources have also been used extensively to fuel the economic expansion. Such a growth pattern is typical in developing countries at their initial stage of development but it usually comes with diminishing returns. Future growth will need to be increasingly driven by the adoption of advanced technologies and improved economic efficiency, which will boost productivity growth and lower environmental pressures.

The recognition of this need to boost productivity has prompted renewed policy efforts to step up structural reforms. Signs are emerging that productivity has already benefitted from reforms introduced in the past decade. After slow economic growth in the early 2010s in the wake of the global financial and economic crisis, Viet Nam introduced new market reforms and accelerated its economic integration into global value chains, leading to a rebound of productivity growth. Accelerating structural reforms, including those that help facilitate the exit and entry of firms, could also help lower the costs of the green transition through allowing for smoother resource reallocation from diminishing sectors, such as coal mining which embraces a large number of workers in Viet Nam (ILO, 2022[1]), to emerging sectors. This chapter argues that such reforms should continue and even be accelerated. The key messages are:

Despite improvements underway, Viet Nam’s business climate remains difficult, which acts as a deterrent to private business activity and foreign investment. Increasing business dynamism will require further reductions in barriers to firm entry and exit and the introduction of greater competitive neutrality between the various sources of activity.

Viet Nam is already among the leaders of digital technology in Southeast Asia and has the potential to further develop its take-up of digital tools. Enhancing the diffusion of such technology will require improved skills and less stringent regulation in some areas so as to facilitate experimentation. The government should lead by example and further improve its digital services and facilitate access to data. The private sector should play the key role in digital transformation. Restrictions on cross-border data flows should also be lowered.

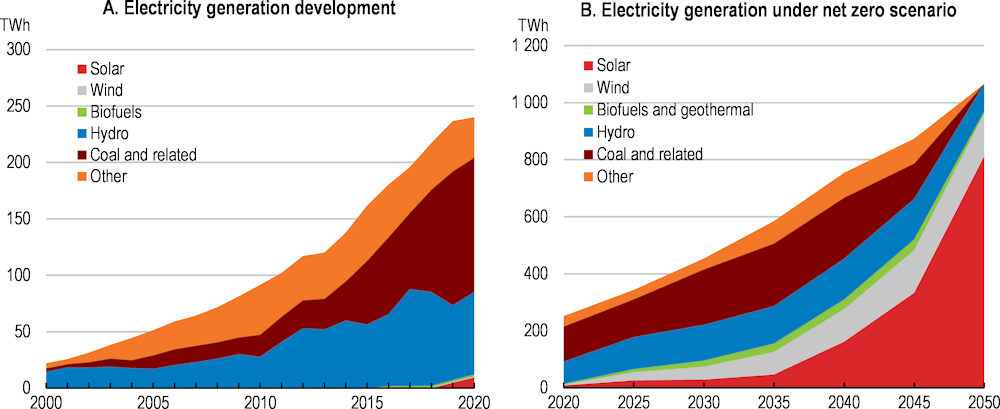

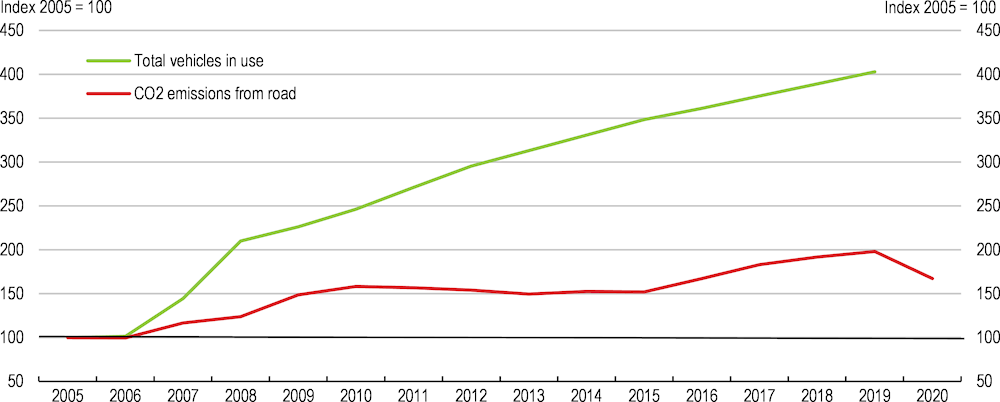

The rapid increase in greenhouse gas emissions is unsustainable. Although Viet Nam has actively promoted the roll-out of renewable energies, this has not prevented a rapid increase in coal-fired electricity production and transport emissions. More needs to be done to shift towards a sustainable energy mix and to improve energy efficiency. Agriculture is also a source of greenhouse gas emissions, especially methane from rice farming. Addressing this source of emissions will support the government’s commitment to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Note: Labour productivity is defined as GDP per worker.

Source: Asian Productivity Organisation, APO Productivity database 2021.

Viet Nam has relied on a toolkit of policies to spur economic growth in the past decade to enhance business dynamism, improve the business climate, and upgrade its technological sophistication:

Starting a new business has been made easier, which is essential to encourage a process of creative destruction, where resources can be reallocated to newly created high potential firms from less productive incumbents, and therefore boost overall business dynamism and productivity. New firms can bring innovative technologies and new managerial approaches, which is a source of greater efficiency and productivity.

Restrictions impeding foreign direct investment have been eased, although not in all sectors. The acquisition of publicly listed firms by foreign investors, through mergers and acquisition, is still subject to an equity limit of 49% in many sectors. Foreign firms are therefore often not able to compete with domestic producers in restricted sectors, hence reducing the benefits in terms of overall business dynamism, innovation, and productivity.

Incumbent state-owned enterprises have been partially reformed, although they continue to dominate their market with the help of privileged access to credit and land, which distorts competition. Furthermore, the regulatory authorities that supervise state-owned enterprises are not independent from government. This section provides an overview of recent reforms and discusses how to address remaining challenges.

Viet Nam has implemented many reforms since the late 1980s to improve the business environment and to enhance competition. Since 2014, the government has set yearly targets with respect to governance quality, competitiveness, innovation and e-government. It has also implemented steps to reduce administrative burdens in areas such as taxation, customs, social security, construction licenses, land registration, electrical access, corporate establishment and closure, and investment procedures. In addition, state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform and private sector development have been at the centre of government policy priorities and efforts to ensure fair competition among different players in the product market. Efforts have also been made to deal with different forms of abuse of market power even by non-state dominant players.

A one-stop shop procedure has also been in place since 2015, with instructions given to relevant ministries to improve the use of online portals and e-government websites. Significant improvements have been achieved in the implementation, including an inter-agency one-stop shop that deals with the various administrative procedures via Public Service Centres to handle business registration, export-import procedures, land use, production safety and tax payments. The online public service system has four levels, and allows making transactions online and beyond administrative boundaries (Decree 61/ND-CP issued in 2018). The electronic system reduces compliance costs and the time required for administrative procedures. It also potentially restricts collusive contacts between businesses and state management agencies, therefore reducing the risk of corruption.

To improve trade facilitation, Viet Nam joined the ASEAN Single Window system in 2015, with involvement of the customs administration and Ministry of Finance. This enables electronic transmission of standardised data and information on shipments, exchange of information between government agencies of various countries and expedited official decisions on clearance and release of cargo and conveyances. Surveys of businesses have shown that the single window system sharply reduces the time needed to clear customs and drastically lowers the cost of cross-border trade procedures. Most recently, two revised laws, the Law on Investment and the Law on Enterprises, which were approved by the National Assembly in June 2020 and came into effect on 1 January 2021, aimed to improve the business environment, simplify administrative regulations and further facilitate investments.

As a result of these reforms, Viet Nam has displayed an improved performance in international benchmarks of market conditions. According to the World Economic Forum report “Global Competitiveness Index 4.0” in 2019, on the “Enabling Environment Component”, Viet Nam ranked 66th (out of 141 economies), based on a score of 64.9. The country’s ranking was better than the Philippines (78th), Cambodia (93rd) and Laos (101st), but lower than for Malaysia (28th) and Thailand (55th) and Indonesia (56th). There have been significant improvements since 2017 when Viet Nam ranked 79th out of 132 countries. Viet Nam performed well in this report in terms of government long-term vision and ICT adoption but less well in settling disputes, competition, insolvency regulatory framework and transparency (Schwab and World Economic Forum, 2019[2]).

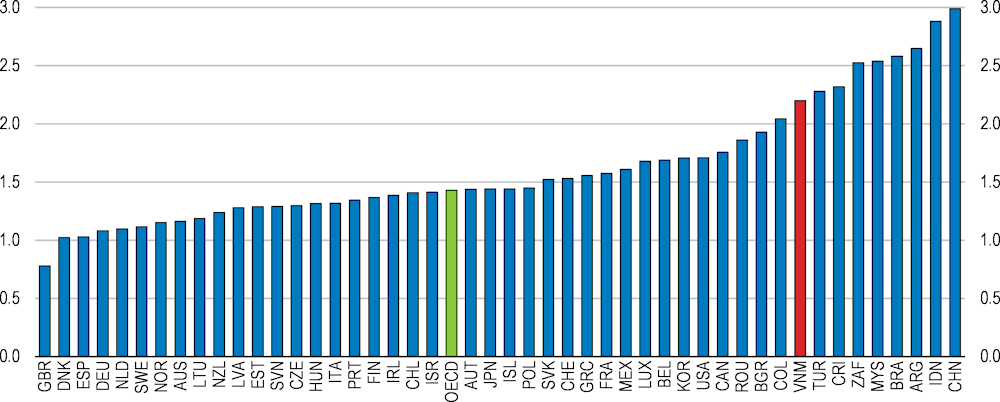

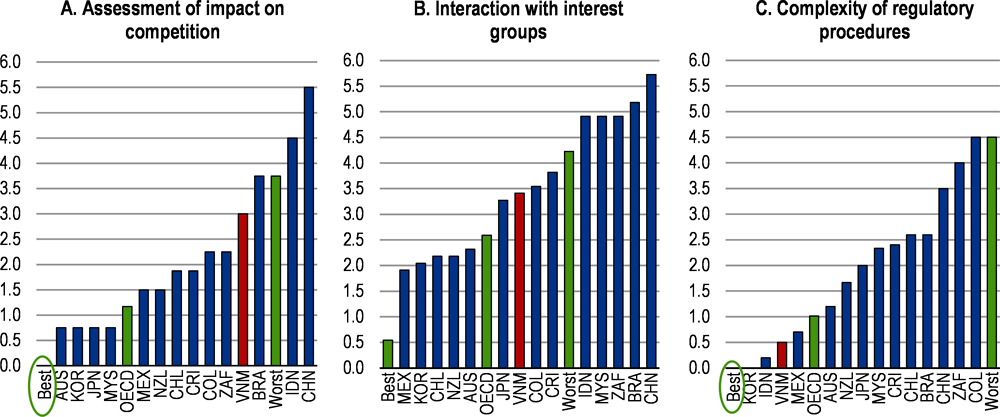

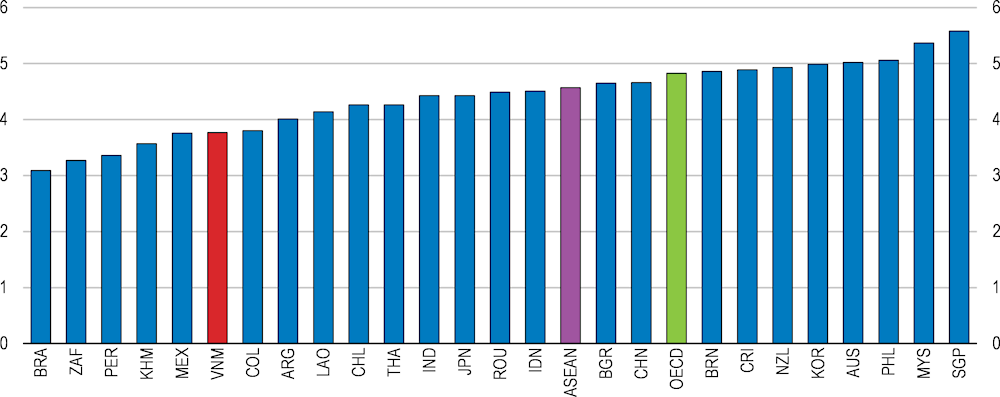

Viet Nam also performs well compared to regional peers according to the OECD Product Market Regulation (PMR) indicators. PMR indicators assess the extent to which regulations support or restrict competition in key sectors of the economy, including the extent to which firms can enter markets and compete with incumbents (Box 2.1). According to the PMR indicators assessing the situation in early-2022, Viet Nam’s regulatory policies impose lighter restrictions than in the non-OECD emerging-market economies for which data are available (South Africa, Brazil and Argentina) and regional peers (Indonesia and People’s Republic of China (hereafter China) (Figure 2.2). Competitive forces are therefore allowed to play an important role in the country.

However, delving below the aggregate PMR score gives a more nuanced picture of the policy landscape. The PMR sub-indicator for “barriers to domestic and foreign entry” is low (1.63), suggesting that Viet Nam is widely open to foreign trade and foreign investment and enforces relatively light administrative burdens on businesses and start-ups. By contrast, the PMR sub-indicator for “distortions induced by state involvement” is relatively high (2.77). This reflects an economy where several sectors are dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the government is directly involved in business operations, including through price controls. As such, reform efforts should be focused on sectors currently dominated by state involvement, with measures to liberalise market forces in these sectors and reform the governance of SOEs. While the government has already taken steps to equitise state-owned firms and partly float equity stakes in these firms on the stock market, more could be done to sell more shares of equity capital to private investors. More could also be done to improve the governance of state-owned enterprises and reduce the involvement of state ministries and provincial governments in their day-to-day operations.

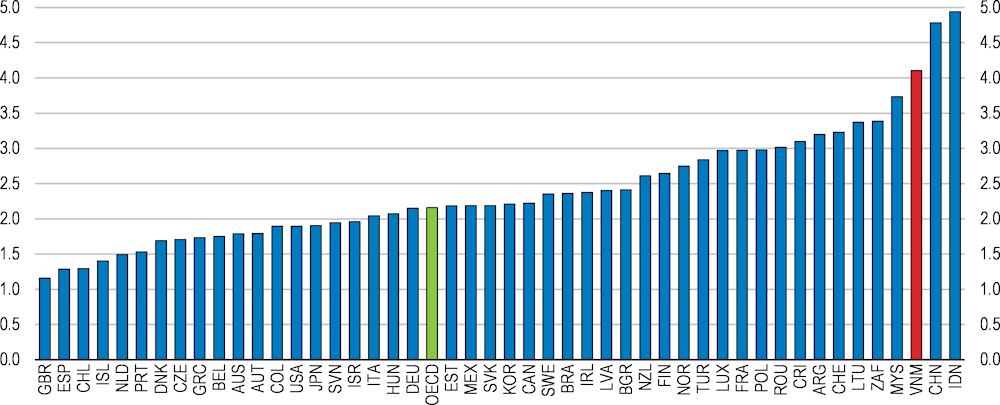

Overall Product Market Regulation Indicator, index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, latest year available

Note: Information used to calculate the 2018 PMR indicators is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 or a later year depending on when the information was provided by the relevant country (1 January 2020 for Viet Nam).

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database and OECD-WBG, Product Market Regulation database.

Competitive pressures in markets for goods and services can bring many economic benefits and ultimately result in faster output growth and higher living standards of citizens. Pro-competition regulation is necessary to ensure that markets function with competitive pressures, helping to reduce market failures. In contrast, improperly designed regulations can impede competition and therefore hinder business dynamism, firm entry and exit, and the ease of reallocation of capital and labour resources. Regulatory reform can help to restore the pressure of competition in markets of goods and services, and eventually boost innovation, productivity, and economic growth.

In emerging markets, the quality of institutions and regulations exerts a large influence on firm productivity, for example through incentives to invest in human capital, make productive investments, and adapt to new technologies. If markets are poorly regulated, such as with weak enforcement of competition laws, inefficient firms can drive competitors out of the market by abusing market power. State-owned enterprises with special privileges to access credit, land and technology have an unfair competitive advantage that can be used to erect barriers that constrain the entry and growth of some highly productive and innovative private firms. Hence, improvements in the business environment and conducive regulatory practices – fair competition, increased business freedom – support growth of multifactor and labour productivity.

To help policymakers design proper regulation, the economy-wide PMR indicators measure the regulatory barriers to firm entry and competition in a broad range of key policy areas, ranging from licensing and public procurement, to governance of SOEs, price controls, evaluation of new and existing regulations, and foreign trade. Since 1998, the PMR indicators have been compiled every five years for most OECD countries, and more recently they have been made available for a range of emerging markets. In emerging Asia, PMR indicators are available for China, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia and Viet Nam. The indicators take values that range from 0 (least restrictive) to 6 (most restrictive). For most countries, the latest observation refers to 2018, with more recent measurement for a few countries, including Viet Nam.

Hence, significant room remains available to further improve market forces and reduce government involvement as well as the abuse forms of market power. Building on past progress, market reforms should be pursued with renewed vigour, along with improving the ease of doing business, investment freedom and competitive neutrality. This will be particularly important as the country moves past the most acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and needs to cement a solid recovery path (APEC, 2021[3]). The priority should be to level the playing field between private firms, SOEs and foreign entities. Also important would be to simplify and reduce the regulatory burden faced by SMEs, notably in terms of improving access to land and to financial resources, which could help increase profitability, investment, and growth.

The government has recently adopted a number of initiatives for further market reforms during the period 2022-25 under the Economic Restructuring Action Plan (Resolution 54/NQ-CP/2022). These include steps to reduce the number of procedures requiring time, costs and risks for businesses. The government also plans to reduce the list of investments subject to barriers and eliminate regulations that are overlapping, conflicting, and legally unclear. Land registration will be accelerated, and the renewal of land authorisation will be facilitated. The authorities also wish to promote the digital transformation of the public administration, promote decentralisation and local empowerment, and tailor regulatory policy so as to boost business development and activity. Nevertheless, a consistent implementation will be needed with respect to accelerating SOE reform, further improving SOE management, re-enforcing the implementation of the Competition Law, dealing with all kinds of market power abuse and collusion, avoiding all forms of state-business collusive behaviours harmful for competition.

Further broad-based simplification of administrative burdens, cutting red-tape and reducing compliance costs for businesses and households need to be pursued. The Administrative Procedure Control Agency (APCA) inside the Office of the Government has been leading an effort to reduce administrative burdens for over a decade (OECD, 2011[4]). The new Government Resolution 02/NQ-CP issued in 2022 has specific targets related to the business environment, national competitiveness, technological innovation and sustainable development indicators. The Administrative Procedures Compliance Cost Index (APCI) annual report serves as an important tool for monitoring and improving administrative procedure reform. This report objectively reflects the level of administrative reform, improvements to the business environment and enforcement of policies and laws through analysing costs faced by enterprises when undertaking administrative procedures.

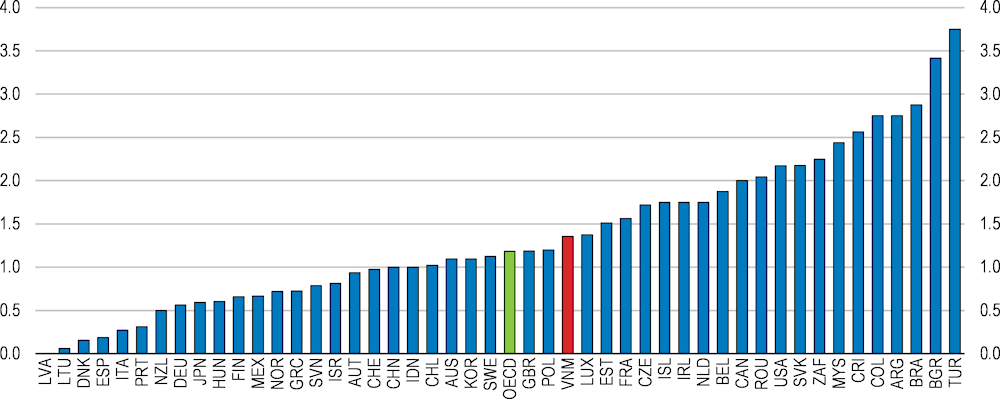

Viet Nam’s SME and entrepreneurship support policies began in the early 2000s. In 2017, the National Assembly passed the Law on Support for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), which is the first of its kind in Viet Nam and replaces all previous decrees on SMEs (OECD, 2021[5]). The law provides several measures to support the development of SMEs, with facilitation steps regarding access to credit, credit guarantees, corporate income tax and land use for production. It also establishes new technological support in the form of incubators and start-up hubs, market expansion, information and legal support, and human resource development. In accordance with the SME law, support has been prioritised for women-led, individual and innovative SMEs. Thanks to this reform, the regulatory framework is in principle easy to navigate. Accordingly, the PMR sub-indicator assessing aspects important to SME development, such as the administrative burden on start-ups, obtains a better score than in many emerging-market economies and in some OECD countries (Figure 2.3).

Indicator of administrative burdens on start-ups, index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, latest year available

Note: Information used to calculate the 2018 PMR indicators is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 or a later year depending on when the information was provided by the relevant country (1 January 2020 for Viet Nam).

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database and OECD-WBG, Product Market Regulation database.

Viet Nam has been successful in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and entering global value chains (GVCs). The share of exports to GDP reached 93% in 2021 to be one of the highest in the world. Nevertheless, domestic linkages with global value chains remain relatively weak. A survey of Japanese firms operating in Vietnam by the Japan External Trade Organization in 2021 showed that the share of domestic purchase of parts and components in Viet Nam by Japanese firms at 37.4% is higher than Malaysia (35.5%) and the Philippines (30.7%) but much lower than Indonesia (45.5%), Thailand (56.4%) and China (69.5%). The share of domestic firms in these domestic purchases is even lower since most of these purchases are from foreign firms producing in Viet Nam. There are both supply-side constraints (access to key factors of production such as land, credit and technology) and demand-side constraints (market information, product quality, standards and certification) that prevent Vietnamese domestic firms, especially SMEs, from actively engaging in GVCs. Addressing these constraints to help SMEs improve their competitiveness and capacity in product innovation and management is essential to enhance productivity, value creation and value capture for the overall economy.

In early-2021, the OECD published an in-depth review of Viet Nam’s policies to sustain the performance of small and medium enterprises and entrepreneurship (OECD, 2021[5]). The report assesses the quality of the business environment, and national policies in support of new and small businesses. Its main finding is that Viet Nam’s business environment is conducive to business growth, although there are still areas for improvement. A key reform has been to lower the statutory corporate tax rate from 32% in the early 2000s to 20% today, which is below the OECD average of about 23%. Preferential tax rates of 15% and 17% have been discussed for SMEs, but not implemented so far. Instead, the government is providing financial help through its SME Development Fund (SMEDF), which supports sectors such as innovative companies, agriculture, forestry, aquaculture, water supply, water treatment and water management, as well as manufacturing firms. A credit guarantee fund (CGF) was also established to facilitate access to finance for SMEs. However, both programmes suffer from low take-up, in part because of the stringency of conditions that need to be met to become eligible. It is crucial that measures for improving the institutional capacity of the SME Development Fund (SMEDF) are undertaken. This will enhance the relevance and accessibility for SMEs, thereby increasing take-up. The local credit guarantee fund (CGF) network that is supposed to facilitate SME access to credit needs to be comprehensively reviewed given its current capacity in both financial and human resources which is very weak.

In addition, during the pandemic the government introduced several supporting measures for SMEs. The corporate income tax was cut by 30% for enterprises with revenues less than VND 200 billion in 2020 and 2021. The government is also supplying non-financial business development services (BDS) to help SMEs improve their managerial performance and improve their ability to compete, with advice in the form of consulting, training, mentoring, and incubating. Three assistance centres were open in key metropolitan areas to provide this advice in-house. The comprehensive Programme for Socio-Economic Recovery and Development (PSERD) adopted by the Government in January 2022 (Resolution 11/NQ-CP) provides an interest-subsidised loan to enterprises (mostly SMEs) and the authorities have committed to “continue to review and remove barriers on institutions, mechanisms, policies, and legal regulations that hinder production and business activities; reducing and simplifying administrative procedures, improving the business investment environment; strengthen the handling of administrative procedures on the online platform”.

In particular, administrative rules remain burdensome for SMEs and should be simplified further. The government should develop a more concrete programme to implement the administration and institutional reforms and business environment component of the PSERD. Many firms claim to have trouble with completing post-registration administrative procedures, obtaining qualification certificates, and certificates proving that they comply with existing technical standards and regulatory requirements. Therefore, companies often have to rely on informal and costly shortcuts to circumvent administrative obstacles. There is past evidence that interference in business activities can be more burdensome for large firms with sizeable profits, further discouraging investment and upgrading (OECD, 2018[6]). This weak control of corruption is consistent with the results of the Viet Nam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) 2021 which found that informal factors, such as personal relationships, remain important to secure a place in public sector employment, to get a land use right certificate or to access better healthcare services (CECODES; VFF-CRT; RTA & UNDP, 2022[7]). This explains to a large extent why the informal sector remains so pervasive and large, despite the simplification of business procedures.

While the overall policy framework is the same for all local governments, there is room for flexibility and proactive initiatives in implementing policy. To make doing business easier, local officials can take different approaches to the administrative procedures required for business operations such as delivering license certificates, approving permits, providing supporting documents, minimising paperwork, conducting inspections and handling tax filing applications. The incidence of bribery and other means of corruption also vary across provinces, and not all provinces have been equally effective in implementing anti-corruption decisions made by the central government and the National Assembly. The Provincial Competitiveness Index, which is designed to assess the ease of doing business, quality of economic governance and the results of administrative reform efforts by local governments in Viet Nam’s 63 provinces and cities to promote private sector development, shows that large gaps prevail between provinces (Malesky, Pham and Truong, 2022[8]). To facilitate and encourage local government officials to take proactive and innovative actions and to improve government officials’ accountability, a number of new measures have been outlined in the Government New Comprehensive Action Plan for Administration Reform 2021-2030 (Resolution N76/NQ-CP in July 2021). These measures include improving the civil service system, strengthening open and merit-based recruitment and performance evaluation and providing a favourable environment for innovative decision-making culture. It is important to effectively implement these policies. More autonomy in decision making should be further encouraged at all levels of government, with strong accountability systems in place.

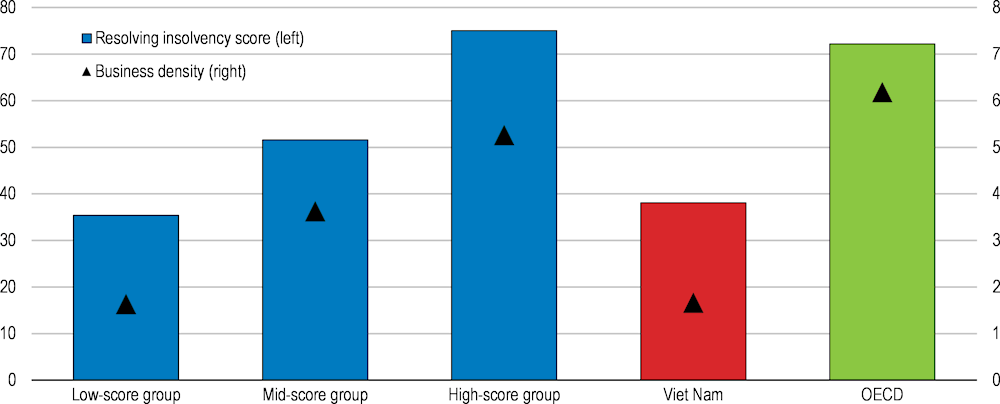

Unrestricted firm entry to markets is important for enhancing product-market competition and productivity. Similarly, unrestricted exit from markets is also crucial to allow unproductive firms to be quickly liquidated, therefore allowing a swift reallocation of labour and capital to other market participants. Empirical research based on firm-level data shows that reforms to insolvency regimes that lower barriers to corporate restructuring are associated with higher multifactor productivity growth of laggard firms (Adalet, Andrews and Millot, 2017[9]). Hence, insolvency regimes should not unduly inhibit corporate restructuring, which will in turn incentivise experimentation and encourage the adoption of new technologies. Reforming insolvency regimes to reduce the cost and length of procedures can therefore enhance technological diffusion and contribute to faster productivity growth.

In Viet Nam, firm exit can occur through two different processes, notably firm liquidation/dissolution and firm bankruptcy. Final settlements for these two kinds of firm exit are different but both involve time and resources that often lead to a significant delay or protracted settlement that obviously hinders overall business dynamism. In 2021, only 35% of cases were completed (46% in 2022). The procedure for winding down a company seeks to ensure that all debts have been settled and relevant documents are in order. Dissolution regulation requires that all documents are properly prepared and filed with the competent licensing authority to commence the liquidation procedure. Final wind-down approval requires the approval of the tax authority, thus presenting the opportunity to collect any outstanding tax shortfall, relevant penalties and interest. This procedure can be time-consuming and costly: dissolving a company takes in principle four to six months, but in practice it often takes a much longer period if questions are raised by authorities about past regulatory and tax compliance. While the OECD has not compiled insolvency indicators for Viet Nam, indicators from the World Bank Doing Business survey show that there is clearly room to improve insolvency procedures in the country (Figure 2.4).

2020 or latest year available, average of each group

Note: The score for resolving insolvency is the simple average of the scores for each of the component indicators: the recovery rate of insolvency proceedings involving domestic entities, as well as the strength of the legal framework applicable to judicial liquidation and reorganisation proceedings. Business density is defined as new registrations per 1 000 people aged 15-64. 144 countries, where data is available, are grouped by the score of resolving insolvency (44 countries for the low-score group, 44 for the middle, and 44 for the high). Viet Nam belongs to the low-score group.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators database and Doing Business 2020 database.

The current insolvency regime is rarely used because it entails significant resources and time and is therefore an impediment when seeking a formal bankruptcy procedure. Reform should take the form of reducing the length of the whole process and increasing the recovery rate for secured creditors (21% compared to the OECD average of 70%). This would help re-allocate productive resources more quickly and strengthen access to credit by re-assuring creditors of the ability to recover part of their credit if borrowers go bust. In practice, consideration could be given to introducing a specialised SME bankruptcy regime aimed at achieving fast reorganisation and liquidation. For example, in 2020, Malaysia integrated an out-of-court scheme for SMEs into one for individuals to simplify procedures, given that micro-sized firms owned by individual entrepreneurs are more susceptible to adverse economic shocks. In addition, out-of-court restructuring of firms should be encouraged to speed up the process and avoid congestion in courts. A set of indicators should be provided to entrepreneurs to give them information about the risk of bankruptcy, so that they can begin restructuring procedures before becoming insolvent. In addition, the bankruptcy procedure could be accelerated by simplifying some requirements on financial statements of firms and establishing a database of firms.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, government support was provided to avoid a wave of business bankruptcies, like in many other countries. Without such support policy, both viable and unviable businesses would have faced the risk of becoming insolvent and exiting the market, with long-lasting damage to human capital, skills, and economic growth. Successive support packages were approved by Viet Nam’s National Assembly, such as combined monetary and fiscal measures in Resolution 43 in January 2022 with VND 40 trillion in funds for loans at a low rate of 2% through commercial banks for businesses in a variety of industries.

According to the General Statistics Office’s data, the number of firms leaving the market increased by 17.7% in 2021 from the previous year, a relatively small increase considering the strictness of confinement measures throughout the year. Out of 119 800 enterprises leaving the market, about 55 000 were temporarily suspending operations, while 48 100 stopped operations while waiting for approval of their dissolutions (Figure 2.5).

Number of firms entering and exiting

Viet Nam has a strong system for public consultation on new regulations, but there is scope for the process to be further developed. The 2015 Law on Promulgation of Legal Documents (the 2015 Law on Laws) provided a solid legal framework for public consultation (social criticism) on new legal documents. The revised Law in 2020 reinforces further this foundation. It requires that feedback and comments obtained as a result of a public consultation on a draft legal document should be assessed by the sponsoring agencies and attached to the draft legal document for approval (National Assembly, 2020). However, public consultation can often be a formal procedure without substantive discussions; time for inputs is limited and there is a serious lack of incentives and interest from various stakeholders to provide meaningful contributions to the legal document formulation and approval.

Formulating regulations in an open and transparent fashion, with appropriate and well publicised procedures such as consultation of all interested stakeholders, brings many benefits. In particular, it improves the quality of rules and programmes, and it also improves compliance and reduces enforcement costs for both governments and citizens subject to regulations. Most OECD and non-OECD countries have designed public consultation procedures to collect feedback on draft regulations and ensure that regulators can take into account the views of opposing interests in designing new rules, as well as bringing in expertise and new ideas on how best to design new policies. Countries have adopted procedures that must be put into place when designing new regulations such as:

1. Notice-and-comment practices that involve a pre-publication of regulatory proposals and a public invitation to post comments on these proposals within a prescribed time period.

2. Public hearings where interested parties and groups are invited to comment in person on a regulatory proposal, in addition to other forms of public consultation.

3. Advisory bodies such as councils, committees, commissions and working parties with a defined task within the regulatory process and composed of either only government officials, or a combination of stakeholders.

4. Lobbying regulations to ensure transparency in the interaction between businesses and interest groups with policy makers and avoid unjustified influence over the regulatory process, which would result in less pro-competitive regulation, or regulation that protects incumbents or firms with stronger lobbying capacities. Requiring policy makers to make their agenda of meetings publicly available and require “cooling-off” periods, during which departing government officials cannot join private entities they had previously been regulating, are examples of such measures.

The PMR indicators take into account these various channels to compile a sub-indicator on “interaction with interest groups”. According to this sub-indicator, Viet Nam has a strong performance overall in this area (Figure 2.6). This reflects the considerable progress made in improving the quality of its regulation-making processes. Viet Nam has an established practice of extensive and generally effective consultation with affected stakeholders both within and outside government and, for principal legislation, multiple stages of quality checking from different perspectives at the policy formation, drafting and enactment stages (OECD, 2018[6]).

According to the legal system, draft legislation must be posted on websites and mass media. Legislative proposals, including the assessment of their impact, must be placed on government websites for 20 days to solicit comments. The draft legislative agenda, once finalised and submitted to the National Assembly for consideration, is to be posted on the Internet. A draft Legal Normative Document (LND) is to be posted for comment online for at least 60 days and any changes to that draft, incorporated pursuant to its appraisal by the Ministry of Justice, are similarly to be posted. The lead agency should collect comments from the concerned agencies and those who would be directly affected by the legislation. For LNDs affecting business, the drafting agency must also send the draft to the Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry to collect comments. These comments are to be consolidated, analysed, and incorporated into the draft. A consolidation of the comments, and a report on their incorporation, then accompanies the draft to the Ministry of Justice for appraisal, as well as being posted on the relevant website.

Indicators of the simplification and evaluation of regulations, index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, latest year available

Note: Information used to calculate the 2018 PMR indicators is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 or a later year depending on when the information was provided by the relevant country (1 January 2022 for Viet Nam). Best/worst represents the OECD best/worst performing country.

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database and OECD-WBG, Product Market Regulation database.

Social organisations have the right to comment on, and propose, amendments to drafts of laws, ordinances and regulations. Rule-makers are also required to collect opinions of citizens, especially those who are directly affected. The law imposes a duty on rule-makers to collect opinions of the concerned organisations and individuals on draft laws and ordinances, and to consider, summarise, review and write replies to the collected opinions (Le, 2016[10]). Rules are also in place to reduce the risk of conflict of interest, notably cooling-off periods applying to government officials who wish to join the sector that they previously regulated. However, public consultation rules such as public hearings and consultation of advisory bodies are not embedded in the legal system, including at the level of local governments. Hence, public consultation should benefit from a more formal anchoring in the process of legislative and regulatory policy.

The goal of promoting competition is not only about consumer welfare and dynamism in existing markets, but also encouraging innovation and knowledge diffusion, and making sure that missing markets can be created (Aghion, Cherif and Hasanov, 2021[11]), (Hasanov and Cherif, 2021[12]). Antitrust authorities have therefore a crucial role to play in ensuring that incumbent firms do not abuse their market power and prevent entry by innovative firms. Experience in advanced and emerging economies shows that the predominance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and the preferential treatment that they get from governments, often result in distortions to competition, lower business dynamism, weak innovation, and subdued economic expansion. Empirical research using data from emerging Asia finds that the relatively low performance of SOEs poses several problems, including slowing down economic growth, which is especially pronounced in countries where these firms represent a large share of the economy (Taghizadeh-Hesary et al., 2019[13]).

Concerns about the potentially negative impact from a large sector of SOEs have encouraged the adoption of corporate governance codes, which were initially formulated by the OECD (OECD, 2005[14]) and built upon by the World Bank (World Bank Group, 2014[15]). The OECD codes of governance provide concrete advice to countries on how to manage more effectively their responsibilities as owners, and thus help them to make SOEs more competitive, efficient and transparent. The World Bank adds emphasis on performance monitoring and fiscal discipline, with research seeking to identify the most suitable performance indicators, as well as the most appropriate monitoring and evaluation systems. Some countries have been successful in reinvigorating their SOEs and making them contribute productively to strong and inclusive growth, while in other countries the performance of SOEs remains disappointing, with negative consequences for citizens. Avoiding bailing out lagging SOEs with state aid is therefore important to create space for new entrants that will bring innovation and dynamism.

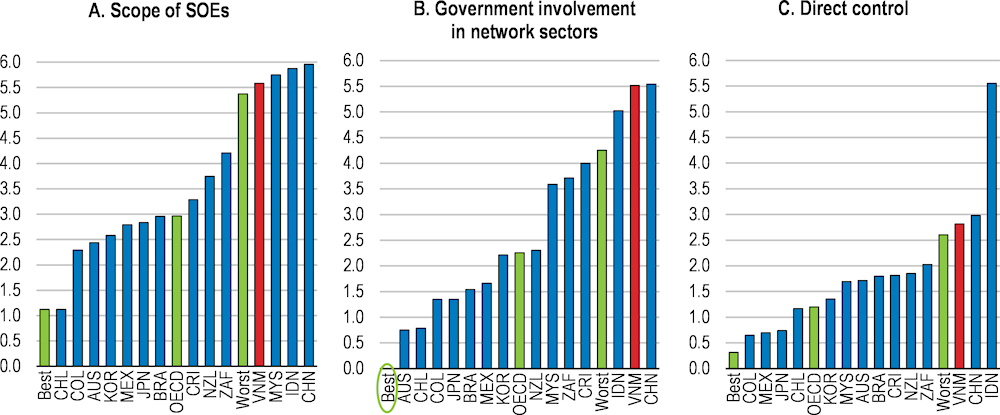

Viet Nam has reduced the number of SOEs from 12 000 in the 1990s to around 2 000 in 2020 (enterprises with over 50% state-owned capital, including 100%) (General Statistics Office, 2022[16]). According to the Agency for Enterprise Development, based on a different definition used in the 2020 Law on Enterprises, the number was smaller but still 673 in 2021. The government has also authorised the equitisation of SOEs since the 1990s, and further efforts have been ongoing to widen the floatation of equity on stock markets thanks to the government’s extensive divestment programme. Nonetheless, the economic importance of state-owned enterprises remains very large by international standards (Figure 2.7 and Figure 2.8), with entire sectors still dominated by a few of these firms, such as in energy (electricity (87%) and petroleum products (84% of gasoline retail sale)) and telecommunications (90% of mobile phone subscribers). The government retains a significant share of ownership in SOEs, even when equitised, in part because foreign investors have not participated in the process. The equitisation of SOEs in 2016-2020 was rather slow: only 39 out of 128 targeted SOEs were equitised; 106 out of 348 targeted were divested with total value of divestment about VND 6 500 billion or 11% of the target (Ministry of Planning and Investment, 2022[17]).

Indicator of public ownership, index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, latest year available

Note: Information used to calculate the 2018 PMR indicators is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 or a later year depending on when the information was provided by the relevant country (1 January 2022 for Viet Nam).

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database and OECD-WBG, Product Market Regulation database.

In many OECD countries where the state is the owner of enterprises, governments seek to achieve “competitive neutrality”, i.e. the equal treatment of private and state-owned firms. An important goal is to separate the role of the government as owner of enterprises and regulator of their activities, so as to avoid conflicts of interest. OECD corporate governance codes provide useful guidelines to achieve competitive neutrality, such as establishing independent regulators, which do not depend on a ministry and have an autonomous budget.

A new OECD review of Viet Nam’s SOE governance (OECD, 2022[18]) did not detect formal statutory discrimination between SOEs and private firms. However, it detected continued conflation of the exercise of ownership rights, the government’s explicit use of SOEs as a main vehicle for the implementation of the State’s industrial or sectoral policies, and no clear separation between policy formulation and regulatory responsibilities, among others. In some measures, SOEs account for a large part of the economy. Concerning SOEs with 100% state-owned capital, although their number was 0.1% of all enterprises, they held 24% of the total fixed assets and their average asset size was 18 times larger than that of foreign-owned enterprises in 2020 (Socialist Republic of Viet Nam Government News, 2022[19]). Continued policy efforts to ensure a level playing field between SOEs and private firms are crucial. In this regard, the new OECD PMR sub-indicator on public ownership control confirms that government involvement in SOEs is high in Viet Nam (Figure 2.8).

Indicators of public ownership control, index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, latest year available

Note: Information used to calculate the 2018 PMR indicators is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 or a later year depending on when the information was provided by the relevant country (1 January 2022 for Viet Nam). Best/worst represents the OECD best/worst performing country.

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database and OECD-WBG, Product Market Regulation database.

Viet Nam should pursue a clear separation between the functions of ownership and regulation, in order to ensure a level playing field with the private sector and to avoid competitive distortions. This requires clear laws and regulations that protect the independence of regulators, especially vis-à-vis ministries. Budget autonomy of regulators is also important to ensure that they remain immune to the influence of ministries. It is also important that regulators have the appropriate financial and human resources to function adequately and with the right level of operational independence. In this context, a Resolution issued by the Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party (12-NQ/TW in 2017) set a policy objective to separate and clearly define the functions of state ownership and regulation for state-owned enterprises, which is a welcome step.

The government should also clearly formulate its ownership policy and how it should behave as an owner. Clear and published ownership policies provide a framework for prioritising SOE objectives and are instrumental in limiting the dual pitfalls of passive ownership or excessive intervention in SOE management. In addition, the government should increase the independence of SOE corporate boards and improve the transparency of the nomination process. One of the most effective tools to protect minority shareholders is the election of independent directors. The public perception in Viet Nam is sometimes that independent directors are not independent-minded and there is a risk that the nomination process could be influenced by factors, which are not necessarily conducive to better SOE management, such as selection and removal of directors not based on professional criteria. Minority shareholders should be able to exert influence on their election through the possibility of nominating candidates through e-voting. The board nomination process should include full disclosure about prospective board members, including their qualifications, with emphasis on the selection of qualified candidates.

In addition, Viet Nam should do more to assure that SOE boards of directors play a strong, autonomous, and professional role. This requires that the appointment of SOE board members follow a strong procedural framework, including selection and removal based on professional criteria, which is beneficial to efficient operations of SOEs (World Bank; Ministry of Planning and Investment, 2016[20]). At present, CEOs and the top management of SOEs are often appointed by the Prime Minister or by sectoral ministers. In some cases, important corporate decisions are made directly by the government (OECD, 2022[18]). Instead, these appointments should be made based on professional credentials, and through a transparent process, to ensure full accountability.

The government established the Commission for the Management of State Capital at Enterprises (CMSC) in February 2018. The Commission, which became operational in September 2018 under Decree No. 131/2018/ND-CP dated 29 September 2018, is an autonomous government body. It exercises full ownership rights in several enterprises in which the State owns 100% of the charter capital and acts as the representative of state capital in joint stock and limited liability companies with more than one shareholder. The CMSC is currently charged with exercising the state’s ownership role in 19 of the country’s state-owned entities – many of which are Corporate Groups or the even larger State Enterprise Groups. By one estimate from the Ministry of Finance of Viet Nam, its portfolio amounts to around 200 individual companies and the total value of state equity in these companies is over VND 1 000 trillion.

The CMSC has a co-ordination power over SOEs in its portfolio, but it is required to take important decisions in concert with other government bodies. An impediment to its effective influence is that it does not have a comprehensive data collection and reporting mechanism to formulate a comprehensive view over key financial and non-financial data of companies in its portfolio. Due to the lack of data and limited sectoral knowledge of the CMSC across its portfolio of SOEs, line ministries in practice continue to play an important role in the control of SOEs, which implies that regulatory functions and policy formulation are undertaken de facto by the same bodies (OECD, 2022[18]).

The provision of state aid support to SOEs, either explicit or implicit, contravenes the spirit and the texts of international free trade agreements. Viet Nam has signed many trade agreements, which have benefitted the country by encouraging foreign investment and facilitating access to foreign markets, and should therefore make sure that the operations of SOEs do not contravene them. The recently signed Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and EU-Viet Nam Free Trade Agreement explicitly prohibit state aid, with transition periods to withdraw existing subsidies. As this happens, SOEs will have to become competitive and innovative in their own right. An important step in phasing out state aid will be to stop providing government guarantees on debt issued by SOEs, as such guarantees undermine competitive neutrality and provide an undue advantage to these public companies. The government has stopped providing such guarantees since 2018 and should continue to reduce the stock of existing guarantees.

Reflecting these concerns, the Ministry of Planning and Investment issued in early 2022 a draft project on “Developing large state-owned corporations, especially multi-ownership state economic groups, to promote the leading role and the role of paving the way for enterprises of other economic sectors”. The government will select a few large and strategic enterprises, using criteria of overall size, market share, profitability, use of technology and corporate governance. The selected SOEs will be encouraged to form linkages with value chains, promote innovation, and enter into participation agreements with firms in other economic sectors. Ministries will be encouraged to consider these large SOEs like private enterprises, with the management of these firms allowed to make decisions autonomously.

While SOE reform remains important for private sector developments, policy challenges are presently emerging from large private domestic corporations. Recent cases of stock and bond market manipulation by some large private corporations have revealed that large private corporations can also cause serious sovereign risks due to their significant exposure to the banking and financial sectors and their increasing importance for job creation. Although few in number, they are therefore creating “market or monopoly power” problems. The new generation of Viet Nam’s reform to strengthen business dynamism should therefore also focus on improving the regulatory environment for all market players, regardless of ownership, to ensure a level playing field for all market participants, including small, medium, and large sized state and private enterprises.

Controls of retail prices are used as a policy tool in a number of countries to some extent. However, they are more widely used in Viet Nam than in many other countries covered by the OECD PMR indicators, although they are less extensive than in some regional peers such as Indonesia (Figure 2.9). Price controls in Viet Nam are implemented through two main mechanisms: price stabilisation and price determination as stipulated in the 2012 Law on Price and its subsequent Decrees. Price stabilisation measures can be enacted only when prices of essential goods or services on a pre-determined list change irregularly or price changes of these products affect socio-economic stabilisation. Eleven categories of commodities are under the price stabilisation list, including gasoline and petrol products, electricity, liquefied petroleum gas, fertilisers and pesticide, sugar, salt, powdered milk for children aged under 6, rice, vaccine and some medicine. The government can use several policy tools, such as rationing, direct purchase or sales, tax measures and price fixing. Price stabilisation is rarely used. Price determination (price cap or band) is applied to a number of commodities and services such as air transport, power transformation, water, heath care and education service. Additional measures of price control have been placed temporarily on some health services and equipment. In 2022, the government halved the environmental tax on fossil fuels to ease the abrupt hike of gasoline prices caused by the war in Ukraine. The government intends to gradually narrow the list of goods and services under prices controls along with the country’s economic development.

Indicator of retail price controls, index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, latest year available

Note: Information used to calculate the 2018 PMR indicators is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 or a later year depending on when the information was provided by the relevant country (1 January 2022 for Viet Nam).

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database and OECD-WBG, Product Market Regulation database.

Price controls are frequently motivated by social goals such as protecting the income of producers (with a price floor) or conversely protecting the living standards of consumers (with a price ceiling). However, there is considerable evidence across countries that price controls distort production and investment decisions, delay market entry, misdirect consumer choices (leading often to over-consumption), and can favour the development of parallel black markets. Price controls hinder market forces and restrain competition because more productive and innovative suppliers are not able to gain market share by offering lower prices than their competitors. Price controls deter the market entry of new investors, which are likely to be disincentivised by the lack of scope to compete with other participants. As such, price controls act as a hindrance to business dynamism, innovation, and creative destruction. Relaxing retail price controls and eventually liberalising them have been a key policy priority in OECD countries. In addition, price controls entail significant fiscal risks when retail prices are set below production costs and can lead to an inefficient use of resources by distorting the signalling mechanism provided by prices. Finally, environmental damage can result from the under-pricing of commodities and their over-consumption. A better and more targeted approach than generalised price controls to protect low-income households is to provide means-tested cash transfers, which enable vulnerable families to purchase the goods and services needed for their daily subsistence (Guenette, 2020[21]).

Liberalising prices subject to controls can be challenging, as shown by episodes of social unrest following sharp price increases in food and energy products. Nevertheless, the policy objectives of keeping costs of living at a manageable level for vulnerable households can be more efficiently achieved through alternative measures such as direct cash-transfers to vulnerable households. Prior conditions need to be established, including a well-designed social safety net to help vulnerable households hit by price increases. The successful experience of natural gas price liberalisation in Ukraine in 2015-16 and Egypt in 2012 suggests that relaxing price controls can be achieved without undue social impact if means-tested subsidies are made available and take-up encouraged by large communication campaigns and with the help of social workers (Guenette, 2020[21]). Some other policy settings that support competitive markets are also a pre-condition to successful price liberalisation. Strong competition and consumer protection authorities together with antitrust laws are essential components to support market forces and dealing with government influence on competition, including state monopolies. The new 2018 Competition Law provides a better legal and regulatory framework to support competitive markets, including a special clause prohibiting government agencies to obstruct competition law enforcement. Effective implementation of this Law will constitute a more effective response to many of the problems that price controls attempt to address (see below).

The diffusion of digital technologies has significant potential to boost productivity. Digital technologies help to access new knowledge and facilitate the diffusion of innovation. They can also contribute to better-functioning markets by enhancing competition. For instance, the wide use of online platforms has lowered transaction costs by putting sellers and buyers in touch directly, including across borders, and by reducing information asymmetries. In the services sector (hotels, taxis, restaurants and retail trade), platforms boost the productivity of incumbent service firms and stimulate labour reallocation towards more productive firms in these industries (Bailin Rivares et al., 2019[22]), (Costa et al., 2021[23]). In Viet Nam, examples of rapid business development triggered by digitalisation include the emergence of ride-hailing platforms, such as Uber followed by Grab, Gojek and Be, which have displaced incumbent taxi services.

Like in other countries, the outbreak of COVID-19 has accelerated the digitalisation of Viet Nam as businesses adopted teleworking arrangements and shoppers used e-commerce services more actively. In addition, schools switched to online education following confinement orders by health authorities and government services were increasingly provided via official online platforms. Together with Indonesia, Viet Nam saw the highest growth rate in the daily average hours spent online for personal use in ASEAN-6 countries (Asian Development Bank, 2021[24]). This section discusses how the country could continue to take advantage of digital opportunities as it emerges from the health crisis.

For emerging markets, embracing digital technologies provides an opportunity to leapfrog various steps in technological development; for instance, China went directly to master technologies linked to artificial intelligence, big data, image recognition, blockchain and digital currencies. In 2022, Viet Nam also decided to accelerate its digital transformation with a new “National Strategy to Develop Digital Economy and Digital Society by 2025, with orientation to 2030”. The government aims to improve the digital infrastructure, accessibility to 5G services and e-government portals, with the objective for the digital economy to account for 30% of Viet Nam’s GDP by 2030, compared to estimates of 6-8% of GDP at present. This would imply further digitalisation, which is likely to require strong policy support. To facilitate the digital transformation of the business sector, the government currently provides various support, including technical advice. In addition, the government should deepen trade integration. In particular, attracting foreign investment in the broad digital economy, including services sectors, will help promote the digital transformation of the domestic economy (see Chapter 1).

With the fast growth of digital activities around the world, the question of how to measure statistically the size of the digital economy has gained importance, together with the analysis of its economic, financial and social impact. Work under the auspices of G20 countries have made progress to identify the main issues and discuss measurement options. It has been proposed to agree that “The digital economy incorporates all economic activity reliant on, or significantly enhanced by the use of digital inputs, including digital technologies, digital infrastructure, digital services and data. It refers to all producers and consumers, including government, that are utilising these digital inputs in their economic activities” (OECD, 2020[25]). However, measuring the digital economy remains fraught with difficulty due to the lack of a universally accepted definition and reliable statistics on its key components, especially in developing countries. Depending on the definition used, the size of the digital economy is estimated at 4.5 to 15.5% of global GDP. A “narrow definition” of the digital economy includes the ICT sector, ICT-producing sectors and digital and platform-enabled products/services (“sharing economy”), but does not include ICT-using sectors such as tourism and transportation.

Using this narrow definition, a previous study suggests that Viet Nam’s digital economy is estimated to have grown strongly since the late 2010s (Google, TEMASEK and BAIN&COMPANY, 2021[26]). Besides manufacturing of products such as smartphones and micro-processors by FDI firms, Viet Nam’s digital economy encompasses financial technology, blockchain, gaming, education technology, healthcare and e-commerce. Viet Nam has three digital unicorns (VNG, VNPay and MoMo) and eleven startups valued at over USD 100 million such as Tiki and Topica Edtech. It has increasingly attracted large amounts of financing, both domestic venture capital and international investment. While this is a good start, the country has the potential to expand its digital activities at an even faster pace.

Digital innovations are transformative because they can be applied and diffused much more quickly than other technologies. The time required to innovate, test and apply digital technologies is much shorter than in manufacturing, energy, or medicine. For example, it took only a few years for artificial intelligence to provide accurate voice and image recognition and to make it available on multiple devices. In both advanced and emerging countries, most people now have access to e-commerce, services platforms, telemedicine, video streaming and e-government portals. Firms that apply these technologies to new products and services can challenge incumbent companies and trigger a fast reallocation of labour and capital, which boosts productivity and economic dynamism.

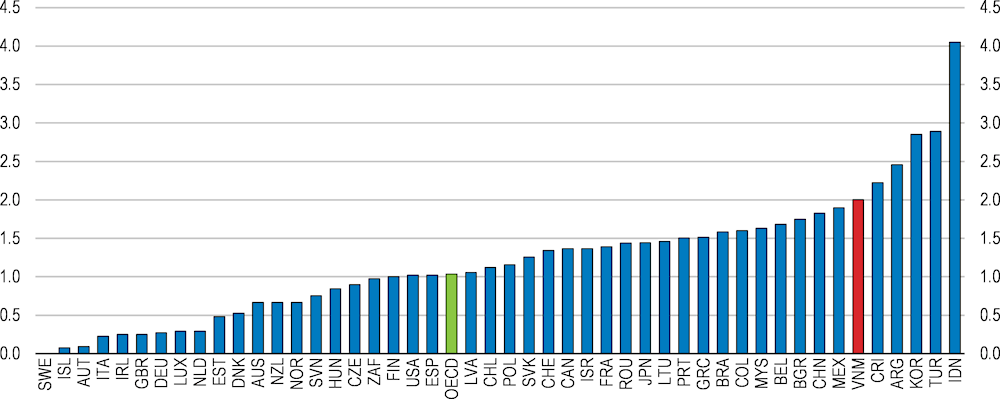

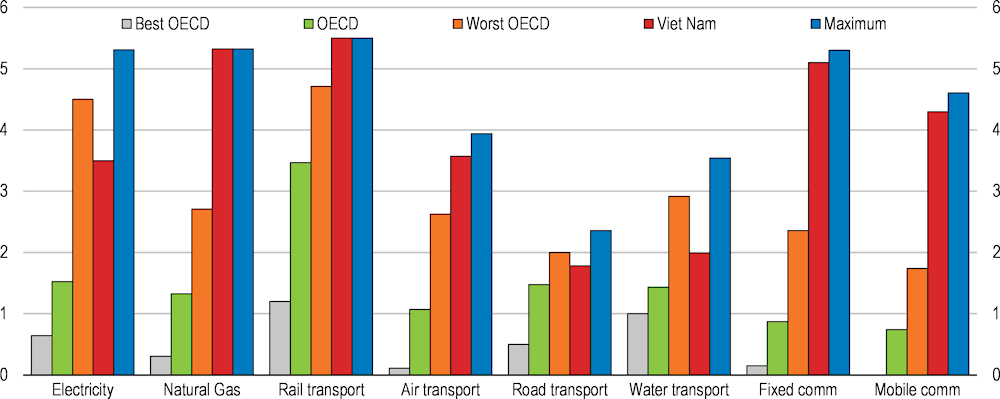

Both existing big firms and new small start-ups can be part of this transformation – as seen in Viet Nam where large state-owned enterprises were quick to roll out modern mobile telephone networks, while new start-ups were entering the business of ride-hailing and cashless payments. Big companies have the financial power and economies of scale to undertake large digital projects, while small start-ups are agile and flexible and can challenge incumbents. However, market failures resulting from network externalities, advantages for incumbents deriving from user data and economies of scale due to high fixed costs and low variable costs can result in dominant market positions that are hard for new entrants to challenge. Governments should therefore make sure that markets dominated by one large company remain contestable and open to firm entry so as to retain the beneficial dynamism arising from digitalisation and technological innovation. However, in Viet Nam the evidence presented in this chapter is that high barriers to entry, weak implementation of competition policy, including banning anti-trust behaviour, has made it difficult to challenge firms with established market power in some sectors (Figure 2.10).

Index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, latest year available

Note: Information used to calculate the 2018 PMR indicators is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 or a later year depending on when the information was provided by the relevant country (1 January 2022 for Viet Nam). Best OECD/worst OECD represents the OECD best/worst performing country, while maximum corresponds to the most restrictive country among those in the PMR database. For mobile communications, the OECD best scores is zero.

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database and OECD-WBG, Product Market Regulation database.

In this regard, a significant improvement in providing a sound legal framework to tackle the abuse of market dominance and monopoly positions has been made in the New Competition Law 2018. However, effective implementation of this Law requires speeding up the process of establishing a new National Competition Commission (NCC) which has a broader and stronger mandate and enhanced capacity to deal with uncompetitive behaviour and to ensure a sound business environment for fair competition. The amalgamation of the two previous agencies to deal with competition issues under the previous 2004 Law, namely the Vietnam Competition and Consumer Agency and Vietnam Competition Council, into the single National Competition Commission (NCC) will help streamline institutional arrangements. However, this may also cause some difficulties in operation due to putting different tasks that require different mandates and institutional support under one authority. Under the 2018 Law, the National Competition Commission will conduct all legal proceedings from detection, investigation to handling of violations of the Competition Law and complaints against settlement decisions on handling of competition cases. In particular, the power of dealing with complaints against its settlement decisions has the potential for conflicts of interest to arise. Therefore, the NCC should ensure high levels of transparency and accountability in its policy implementation to attain trust in competition policy.

On the other hand, many SMEs are faced with numerous obstacles and challenges in realising the digital transformation. In particular, high investment costs, limited knowledge and a lack of human resources make adoption of digital technologies and changes of their business processes difficult. Against this background, the government has been providing a range of supporting programmes for SMEs. For example, the Supporting Enterprises’ Digital Transformation Programme 2021-2025 includes awareness-raising campaigns, training and consulting for SMEs. The 2017 Law on Supporting Small and Medium Enterprises explicitly stipulates that the government needs to formulate policies to support SMEs, such as financial support, including in the area of digitalisation.

The successful digital transformation of Viet Nam will also require investing in digital skills. At present, many firms are unable to use advanced digital technologies due to the lack of workers with the relevant skills. More investment in education, training, and reskilling will be needed so that Vietnamese firms can make a more widespread use of cloud computing, big data and artificial intelligence, while protecting users from cybercrime and consumers from using their private data.

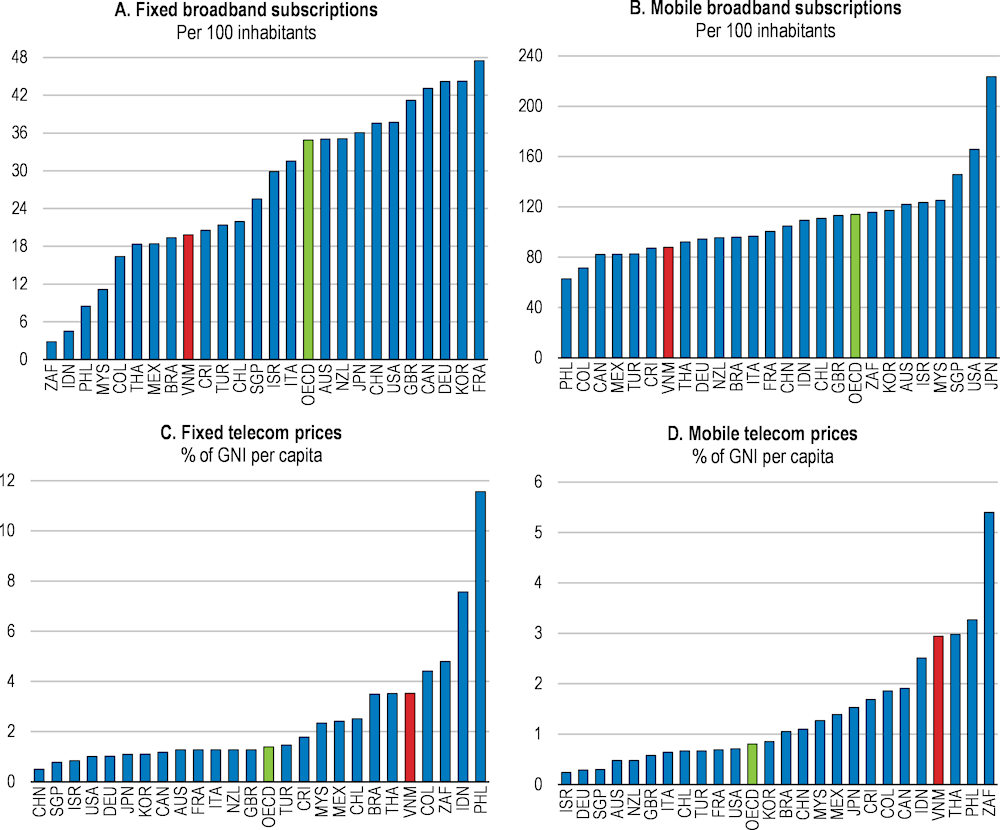

Widespread and affordable access to high-quality mobile telephone and internet connections are essential to the diffusion of digital technologies. Starting from little connectivity in the 1990s, Viet Nam has proceeded fast with the expansion of mobile internet and fixed broadband, including fibre optic. Mobile telephony subscriptions have grown by nearly 3 million per year over the last decade and are now widespread, with more mobile phone subscription than people in the country. Almost 88% of the population has a mobile broadband data connection, allowing them to access internet services and e-government websites (Figure 2.11), though with varying quality. High-speed 4G connection is not always available in rural and mountainous areas, and the speed of internet connection is slow compared to peers (World Bank, 2021[27]). Viet Nam plans to issue licenses for 5G wireless service in 2022 following pandemic delays, with coverage to start in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City and other urban areas, which will allow access to high-speed internet and may avoid installing costly fibre infrastructure. However, building a fibre optic network will remain essential for businesses, schools, universities, and government agencies – and will require large investments.

Like in other parts of the Vietnamese economy, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominate the telecommunication sector. Viet Nam Posts and Telecommunications Group (VNPT) is the incumbent operator owned by the Commission for the Management of State Capital at Enterprises (CMSC), a financial holding entity of the government. Following the creation of a separate regulatory entity, market segments were opened to competition, starting with mobile services in 1995. However, SOEs are still dominating the telecommunication market. Vinaphone, one of the largest mobile operators, is a subsidiary of VNPT and other big players, MobiFone and Viettel are owned by the CMSC and Ministry for Defence respectively. Although the competition among these state-owned telecommunication corporations has resulted in lower prices of telecommunication services, it has hindered the entry of domestic private firms to the telecommunication market, which will be important for Viet Nam in the long term to improve efficiency and transparency in the market. The ownership of these companies has been transferred to the CMSC but, as noted in the previous section, sectoral ministries are perceived as still exerting considerable influence on the management of these companies, including through the appointment of board members, senior executives, and with favourable access to land and credit.

While there is a telecommunication regulator (Authority of Telecommunications), it is a ministerial unit inside the Ministry of Information and Communications, rather than a regulator that is independent of the ministry. If regulators are independent, they can operate impartially without favouritism or conflicts of interest. For instance, major operators, often SOEs, could request favourable treatment, or regulators could behave in the ministry’s interest. Such arrangements can discourage other operators from entering a market in the first place, and thus distort competition. Against this background, a number of countries have enhanced the independence of the regulatory bodies in the telecommunications sector with respect to the institutional set-up of regulators, the structure and sources of their budget and the scope of their functions (OECD, 2016[28]). In Viet Nam, the line ministry oversees the regulator of the sector. Further strengthening regulatory independence would promote competition in the market.

2021 data

Note: The fixed telecom price refers to a fixed-BB basket with 5 GB and the mobile telecom price refers to a high usage voice and data allowing up to 140 minutes of phone calls, 70 SMS and 2 GB data.

Source: International Telecommunication Union.

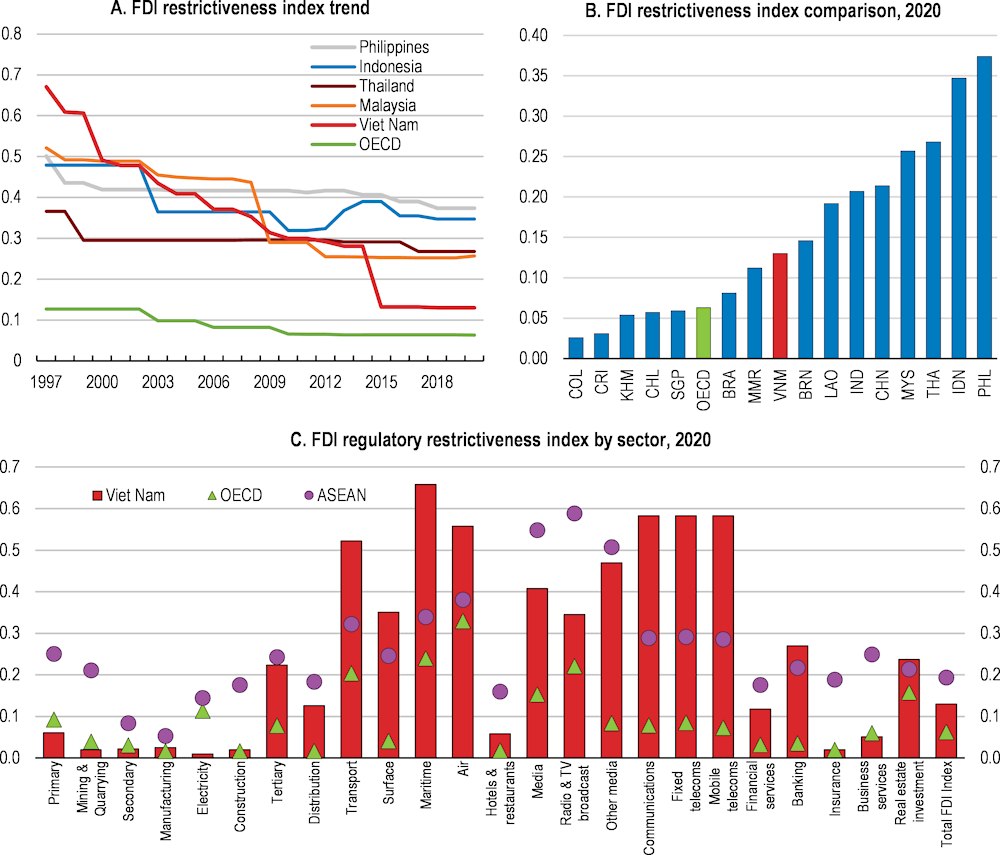

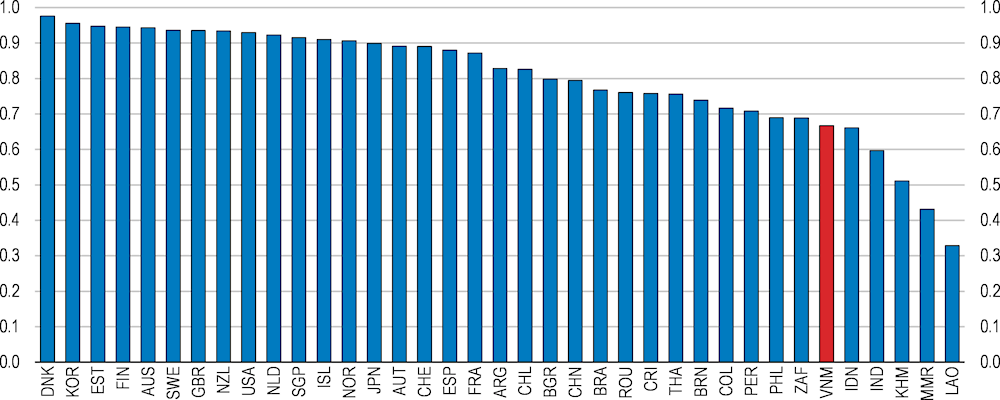

In the telecommunications sector, foreign investors still face some restrictions. Research finds that foreign investment has positive spillover effects on domestic industries, including cross-border dissemination of technologies (Pham, 2009[29]), (Arnold, Javorcik and Mattoo, 2011[30]), (Arnold et al., 2016[31]). Moreover, foreign investment in the digital sectors, especially digital infrastructure, is crucial to help facilitate the digital transformation of the domestic economy (Satyanand, 2021[32]). Indeed, MobiFone was initially established as a joint-venture with a Swedish telecom company. The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index shows that Viet Nam maintains tighter entry restrictions in the sectors of communications, mobile telecoms and fixed telecoms (Figure 2.12). Greater liberalisation of entry conditions would therefore boost Viet Nam’s business dynamism, with likely tangible benefits for total factor productivity (OECD, 2018[33]). Foreign investors are currently subject to a range of restrictions. Services must be offered through commercial arrangements with an entity established in Viet Nam and licensed to provide international telecommunication services. While foreign ownership is allowed up to 65% in non-facilities-based services (i.e. non-infrastructure services providers), majority ownership in facilities-based telecommunications activities is prohibited, thus greatly reducing investors’ interest. Moreover, the Prime Minister’s approval is required for investment in telecommunications services with network infrastructure. In this regard, trade integration gives Viet Nam strong reform momentum. The government has made firm commitments to widen market access to foreign investors in the context of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (ASEAN-Japan Centre, 2022[34]). A new Law on Telecommunications is envisaged to remove the restriction on commercial arrangements, among others. Nevertheless, the government intends to maintain the foreign ownership restrictions. In particular, the restriction on majority ownership in facilities-based telecommunications activities could be further relaxed.

OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, scaled from 0 (open) to 1 (closed)

Note: The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index covers only statutory measures discriminating against foreign investors (e.g. foreign equity limits, screening & approval procedures, restriction on key foreign personnel, and other operational measures). Other important aspects of an investment climate (e.g. the implementation of regulations and state monopolies, preferential treatment for export-oriented investors and special economic zones regimes among other) are not considered. See Kalinova et al. (2010) for further information on the methodology.

Source: OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index database, http://www.oecd.org/investment/fdiindex.htm; see also the ASEAN FDI Regulatory Restrictions Database for information on the underlying measures captured in the Index, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=ASEAN_INDEX.

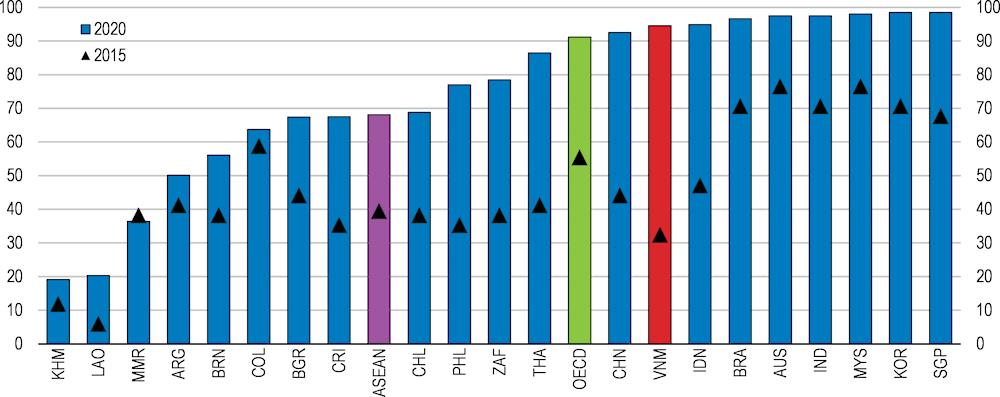

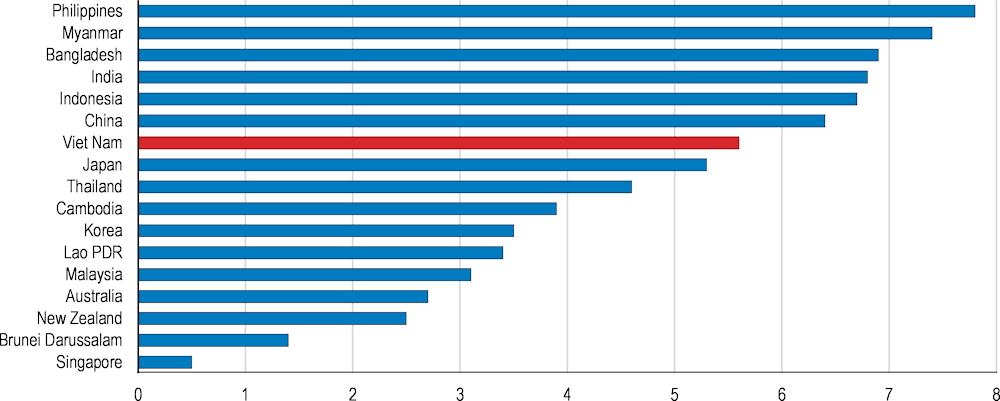

Ensuring a more conducive environment to cross-border data flows is crucial to promote digital innovation. The cross-border flows of telecommunication and digital services are strictly regulated by the government. The OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) compares the degree of restrictions in services trade across a sample of OECD and non-OECD countries. Among these countries, Viet Nam has the strictest score for telecommunication services (Figure 2.13). This reflects restrictions regarding foreign investment in these sectors, foreign participation in executive boards and obligations to have presence of executives in the country. In addition, Viet Nam’s regulations prescribe that certain types of data (such as accounting data and some user-generated data) must be stored in the country, rather than on cloud servers in foreign countries. The Law on Electronic Transactions and the Law on Cybersecurity both contain legal provisions to store certain data in the country for certain enterprises. Both domestic and foreign companies providing telecommunications, internet, and value-added services must store related personal data in the country. Viet Nam, China and Russia are among the very few countries that apply strict limitations on cross-border data flows. While restrictions of the localisation of data can enhance data privacy and consumer trust, helping to fight cyber-criminality (Figure 2.14), they also involve unnecessary compliance costs and restrictions on the free flow of data, creating trade barriers. Such barriers can reduce the benefits of being integrated in global digital networks.

Services Trade Restrictiveness Index ranging from 0 (open) to 1 (closed), 2021

Global Cybersecurity Index, score from 0 to 100 (best)

Note: The Global Cybersecurity Index is a composite index of indicators that monitors the level of cybersecurity commitment in five pillars (legal, technical, organisational, capacity development and cooperative measures). For more details, see Source.

Source: ITU, Global Cybersecurity Index 2020 and Global Cybersecurity Index & Cyberwellness Profiles 2015.

Strengthening digital skills among the labour force is crucial to accelerate the digital transformation. Acquiring digital skills can also help Vietnamese workers reap the benefits from the digital economy, notably through seizing opportunities for better jobs and utilising digital technologies that enhance well-being. The outbreak of COVID-19 has also encouraged the take-up of digital skills because physical distancing has required the shift to on-line education, teleworking, tele-medicine and e‑government. However, successful acquisition of digital skills requires tremendous motivation and efforts by individual workers and businesses and government support concerning education and training. Designing and implementing a digital skills development programme need to be tailored to the needs of different groups of people and different levels of education in a comprehensive and cohesive framework.

Government policy should focus not only on enhancing the supply of high-skilled workers but also on nurturing basic skills for all workers. In the digital world of work, three different types of skillsets become important (OECD, 2019[35]). First, workers need to be equipped with general cognitive skills, such as literacy and numeracy, and basic digital skills. For example, business communication using email and searching information on the internet requires these general skills as the foundation of conducting daily business tasks. Second, soft skills become more important. These skills include analytical skills and a range of complementary skills such as problem solving, creative and critical thinking, communication skills and a strong capacity for continuous learning. While digital technologies reduce demand for routine jobs, workers also need to deal with more complex job tasks, resulting in an increasing demand for these types of skills. Moreover, working in occupations more directly related to new technologies, such as programmers, requires advanced digital skills.

Enhancing basic digital skills of all workers should be a priority. Viet Nam has invested in basic education and achieved both high enrolment rates and high-quality outcomes. The results of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), based on tests administered in 2015 on 15-year-old students, show that students in Viet Nam were on par with the OECD average in mathematics and reading, while they scored above the OECD average in science (Viet Nam participated in PISA 2018, but the international comparability of the results could not be fully ensured). However, compared with the advancement of basic education, levels of basic digital skills among workers are not sufficient to meet the growing demand. Business people consider that workers with basic digital skills have been lacking in Viet Nam, with evidence suggesting that people are less equipped with basic digital skills than in peer countries (Figure 2.15). In this regard, experience of other Southeast Asian countries would be useful. Malaysia, where basic digital skills of workers are considered to be among the highest in the region, has strong training programmes for basic digital skills (OECD, 2021[36]). The eRezeki programme provides people in the bottom 40% income group with opportunities to develop basic digital skills for jobs, such as programming and translation. The eUsahawan programme trains entrepreneurs who lack digital knowledge. Entrepreneurs can attend courses at community centres, public education institutions and on online learning platforms. In Viet Nam, the government has introduced a knowledge dissemination initiative at the community level. A group of experts (digital technology group) is formed to enlighten citizens on basic digital skills, such as the usage of digital apps, while the government prepares guidelines for the pilot programme. By end-August 2022, 51 provinces have participated in the pilot programme and 45 895 digital technology groups were established at the community level. This initiative could be further enhanced by strengthening financial support by the government and collaboration with education institutions.